Secret Chambers and Hiding Places, by Allan Fea

CHAPTER X

JAMES II.'S ESCAPES (continued), HAM HOUSE, AND "ABDICATION HOUSE"

Tradition, regardless of fact, associates the grand old seat of the Lauderdales and Dysarts with King James's escape from England. A certain secret staircase is still pointed out by which the dethroned monarch is said to have made his exit, and visitors to the Stuart Exhibition a few years ago will remember a sword which, with the King's hat and cloak, is said to have been left behind when he quitted the mansion. Now there existed, not many miles away, also close to the river Thames, another Ham House, which was closely associated with James II., and it seems, therefore, possible, in fact probable, that the past associations of the one house have attached themselves to the other.

In Ham House, Weybridge, lived for some years the King's discarded mistress Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester. At the actual time of James's abdication this lady was in France, but in the earlier part of his reign the King was a frequent visitor here. In Charles II.'s time the house belonged to Jane Bickerton, the mistress and afterwards wife of the sixth Duke of Norfolk. Evelyn dined there soon after this marriage had been solemnised. "The Duke," he says, "leading me about the house made no scruple of showing me all the hiding-places for the Popish priests and where they said Masse, for he was no bigoted Papist." At the Duke's death "the palace" was sold to the Countess of Dorchester, whose descendants pulled it down some fifty years ago. The oak-panelled rooms were richly parquetted with "cedar and cyprus." One of them until the last retained the name of "the King's Bedroom." It had a private communication with a little Roman Catholic chapel in the building. The attics, as at Compton Winyates, were called "the Barracks," tradition associating them with the King's guards, who are said to have been lodged there. Upon the walls hung portraits of the Duchesses of Leeds and Dorset, of Nell Gwyn and the Countess herself, and of Earl Portmore, who married her daughter. Here also formerly was Holbein's famous picture, Bluff King Hal and the Dukes of Suffolk and Norfolk dancing a minuet with Anne Boleyn and the Dowager-Queens of France and Scotland. Evelyn saw the painting in August, 1678, and records "the sprightly motion" and "amorous countenances of the ladies." (This picture is now, or was recently, in the possession of Major-General Sotheby.)

A few years after James's abdication, the Earl of Ailesbury rented the house from the Countess, who lived meanwhile in a small house adjacent, and was in the habit of coming into the gardens of the palace by a key of admittance she kept for that purpose. Upon one of these occasions the Earl and she had a disagreement about the lease, and so forcible were the lady's coarse expressions, for she never could restrain the licence of her tongue, that she had to be ejected from the premises, whereupon, says Ailesbury, "she bade me go to my——King James," with the assurance that "she would make King William spit on me."

MONUMENT OF SIR RICHARD HEAD

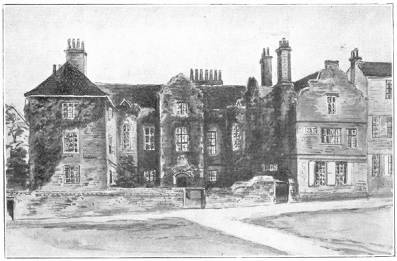

"RESTORATION HOUSE," ROCHESTER

But to follow James II.'s ill-fortunes to Rochester, where he was conveyed on the Tuesday at noon by royal barge, with an escort of Dutch soldiers, with Lords Arran, Dumbarton, etc., in attendance—"a sad sight," says Evelyn, who witnessed the departure. The King recognised among those set to guard him an old lieutenant of the Horse who had fought under him, when Duke of York, at the battle of Dunkirk. Colonel Wycke, in command of the King's escort, was a nephew of the court painter Sir Peter Lely, who had owed his success to the patronage of Charles II. and his brother. The part the Colonel had to act was a painful one, and he begged the King's pardon. The royal prisoner was lodged for the night at Gravesend, at the house of a lawyer, and next morning the journey was continued to Rochester.

The royalist Sir Richard Head again had the honour of acting as the King's host, and his guest was allowed to go in and out of the house as he pleased, for diplomatic William of Orange had arranged that no opportunity should be lost for James to make use of a passport which the Duke of Berwick had obtained for "a certain gentleman and two servants." James's movements, therefore, were hampered in no way. But the King, ever suspicious, planned his escape from Rochester with the greatest caution and secrecy, and many of his most attached and loyal adherents were kept in ignorance of his final departure. James's little court consisted of the Earls of Arran, Lichfield, Middleton, Dumbarton, and Ailesbury, the Duke of Berwick, Sir Stephen Fox, Major-General Sackville, Mr. Grahame, Fenton, and a few others.

On the evening of the King's flight the company dispersed as was customary, when Ailesbury intimated, by removing his Majesty's stockings, that the King was about to seek his couch. The Earl of Dumbarton retired with James to his apartment, who, when the house was quiet for the night, got up, dressed, and "by way of the back stairs," according to the Stuart Papers, passed "through the garden, where Macdonald stayed for him, with the Duke of Berwick and Mr. Biddulph, to show him the way to Trevanion's boat. About twelve at night they rowed down to the smack, which was waiting without the fort at Sheerness. It blew so hard right ahead, and ebb tide being done before they got to the Salt Pans, that it was near six before they got to the smack. Captain Trevanion not being able to trust the officers of his ship, they got on board the Eagle fireship, commanded by Captain Welford, on which, the wind and tide being against them, they stayed till daybreak, when the King went on board the smack." On Christmas Day James landed at Ambleteuse.

Thus the old town of Rochester witnessed the departure of the last male representative of the Stuart line who wore a crown. Twenty-eight years before, every window and gable end had been gaily bedecked with many coloured ribbons, banners, and flowers to welcome in the restored monarch. The picturesque old red brick "Restoration House" still stands to carry us back to the eventful night when "his sacred Majesty" slept within its walls upon his way from Dover to London—a striking contrast to "Abdication House," the gloomy abode of Sir Richard Head, of more melancholy associations.

Much altered and modernised, this old mansion also remains. It is in the High Street, and is now, or was recently, occupied as a draper's shop. Here may be seen the "presence-chamber" where the dethroned King heard Mass, and the royal bedchamber where, after his secret departure, a letter was found on the table addressed to Lord Middleton, for both he and Lord Ailesbury were kept in ignorance of James II.'s final movements. The old garden may be seen with the steps leading down to the river, much as it was a couple of centuries ago, though the river now no longer flows in near proximity, owing to the drainage of the marshes and the "subsequent improvements" of later days.

The hidden passage in the staircase wall may also be seen, and the trap-door leading to it from the attics above. Tradition says the King made use of these; and if he did so, the probability is that it was done more to avoid his host's over-zealous neighbours, than from fear of arrest through the vigilance of the spies of his son-in-law.[1]

[Footnote 1: It may be of interest to state that the illustrations we give of the house were originally exhibited at the Stuart Exhibition by Sir Robert G. Head, the living representative of the old Royalist family]

Exactly three months after James left England he made his reappearance at Kinsale and entered Dublin in triumphal state. The siege of Londonderry and the decisive battle of the Boyne followed, and for a third and last time James II. was a fugitive from his realms. The melancholy story is graphically told in Mr. A. C. Gow's dramatic picture, an engraving of which I understand has recently been published.

How the unfortunate King rode from Dublin to Duncannon Fort, leaving his faithful followers and ill-fortunes behind him; got aboard the French vessel anchored there for his safety; and returned once more to the protection of the Grande Monarque at the palace of St. Germain, is an oft-told story of Stuart ingratitude.

ARMSCOT MANOR HOUSE, WORCESTERSHIRE

ENTRANCE GATE, ARMSCOT MANOR HOUSE

Index | Next: Mysterious Rooms, Deadly Pits