This little volume is a contribution to the comparative study of religions. It is an endeavor to present in a critically correct light some of the fundamental conceptions which are found in the native beliefs of the tribes of America.

So little has heretofore been done in this field that it has yielded a very scanty harvest for purposes of general study. It has not yet even passed the stage where the distinction between myth and tradition has been recognized. Nearly all historians continue to write about some of the American hero-gods as if they had been chiefs of tribes at some undetermined epoch, and the effort to trace the migrations and affiliations of nations by similarities in such stories is of almost daily occurrence. How baseless and misleading all such arguments must be, it is one of my objects to set forth.

At the same time I have endeavored to be temperate in applying the interpretations of mythologists. I am aware of the risk one runs in looking at every legend as a light or storm myth. My guiding principle has been that when the same, and that a very extraordinary, story is told by several tribes wholly apart in language and location, then the probabilities are enormous that it is not a legend but a myth, and must be explained as such. It is a spontaneous production of the mind, not a reminiscence of an historic event.

The importance of the study of myths has been abundantly shown of recent years, and the methods of analyzing them have been established with satisfactory clearness.

The time has long since passed, at least among thinking men, when the religious legends of the lower races were looked upon as trivial fables, or as the inventions of the Father of Lies. They are neither the one nor the other. They express, in image and incident, the opinions of these races on the mightiest topics of human thought, on the origin and destiny of man, his motives for duty and his grounds of hope, and the source, history and fate of all external nature. Certainly the sincere expressions on these subjects of even humble members of the human race deserve our most respectful heed, and it may be that we shall discover in their crude or coarse narrations gleams of a mental light which their proud Aryan brothers have been long in coming to, or have not yet reached.

The prejudice against all the lower faiths inspired by the claim of Christianity to a monopoly of religious truth—a claim nowise set up by its founder—has led to extreme injustice toward the so-called heathen religions. Little effort has been made to distinguish between their good and evil tendencies, or even to understand them. I do not know of a single instance on this continent of a thorough and intelligent study of a native religion made by a Protestant missionary.

So little real work has been done in American mythology that very diverse opinions as to its interpretation prevail among writers. Too many of them apply to it facile generalizations, such as “heliolatry,” “animism,” “ancestral worship,” “primitive philosophizing,” and think that such a sesame will unloose all its mysteries. The result has been that while each satisfies himself, he convinces no one else.

I have tried to avoid any such bias, and have sought to discover the source of the myths I have selected, by close attention to two points: first, that I should obtain the precise original form of the myth by a rigid scrutiny of authorities; and, secondly, that I should bring to bear upon it modern methods of mythological and linguistic analysis.

The first of these requirements has given me no small trouble. The sources of American history not only differ vastly in merit, but many of them are almost inaccessible. I still have by me a list of books of the first order of importance for these studies, which I have not been able to find in any public or private library in the United States.

I have been free in giving references for the statements in the text. The growing custom among historians of omitting to do this must be deplored in the interests of sound learning. It is better to risk the charge of pedantry than to leave at fault those who wish to test an author's accuracy or follow up the line of investigation he indicates.

On the other hand, I have exercised moderation in drawing comparisons with Aryan, Semitic, Egyptian and other Old World mythologies. It would have been easy to have noted apparent similarities to a much greater extent. But I have preferred to leave this for those who write upon general comparative mythology. Such parallelisms, to reach satisfactory results, should be attempted only by those who have studied the Oriental religions in their original sources, and thus are not to be deceived by superficial resemblances.

The term “comparative mythology” reaches hardly far enough to cover all that I have aimed at. The professional mythologist thinks he has completed his task when he has traced a myth through its transformations in story and language back to the natural phenomena of which it was the expression. This external history is essential. But deeper than that lies the study of the influence of the myth on the individual and national mind, on the progress and destiny of those who believed it, in other words, its true religious import. I have endeavored, also, to take some account of this.

The usual statement is that tribes in the intellectual condition of those I am dealing with rest their religion on a worship of external phenomena. In contradiction to this, I advance various arguments to show that their chief god was not identified with any objective natural process, but was human in nature, benignant in character, loved rather than feared, and that his worship carried with it the germs of the development of benevolent emotions and sound ethical principles.

Media, Pa., Oct., 1882.

AMERICAN HERO-MYTHS.

The time was, and that not so very long ago, when it was contended by some that there are tribes of men without any sort of religion; nowadays the effort is to show that the feeling which prompts to it is common, even among brutes.

This change of opinion has come about partly through an extension of the definition of religion. It is now held to mean any kind of belief in spiritual or extra-natural agencies. Some learned men say that we had better drop the word “religion,” lest we be misunderstood. They would rather use “daimonism,” or “supernaturalism,” or other such new term; but none of these seems to me so wide and so exactly significant of what I mean as “religion.”

All now agree that in this very broad sense some kind of religion exists in every human community.[1]

[1: I suppose I am not going too far in saying “all agree;" for I think that the latest study of this subject, by Gustav Roskoff, disposes of Sir John Lubbock's doubts, as well as the crude statements of the author of Kraft und Stoff, and such like compilations. Gustav Roskoff, Das Religionswesen der Rohesten Naturvoelker, Leipzig, 1880.]

The attempt has often been made to classify these various faiths under some few general headings. The scheme of Auguste Comte still has supporters. He taught that man begins with fetichism, advances to polytheism, and at last rises to monotheism. More in vogue at present is the theory that the simplest and lowest form of religion is individual; above it are the national religions; and at the summit the universal or world religions.

Comte's scheme has not borne examination. It is artificial and sterile. Look at Christianity. It is the highest of all religions, but it is not monotheism. Look at Buddhism. In its pure form it is not even theism. The second classification is more fruitful for historical purposes.

The psychologist, however, inquires as to the essence, the real purpose of religions. This has been differently defined by the two great schools of thought.

All religions, says the idealist, are the efforts, poor or noble, conscious or blind, to develop the Idea of God in the soul of man.

No, replies the rationalist, it is simply the effort of the human mind to frame a Theory of Things; at first, religion is an early system of natural philosophy; later it becomes moral philosophy. Explain the Universe by physical laws, point out that the origin and aim of ethics are the relations of men, and we shall have no more religions, nor need any.

The first answer is too intangible, the second too narrow. The rude savage does not philosophize on phenomena; the enlightened student sees in them but interacting forces: yet both may be profoundly religious. Nor can morality be accepted as a criterion of religions. The bloody scenes in the Mexican teocalli were merciful compared with those in the torture rooms of the Inquisition. Yet the religion of Jesus was far above that of Huitzilopochtli.

What I think is the essence, the principle of vitality, in religion, and in all religions, is their supposed control over the destiny of the individual, his weal or woe, his good or bad hap, here or hereafter, as it may be. Rooted infinitely deep in the sense of personality, religion was recognized at the beginning, it will be recognized at the end, as the one indestructible ally in the struggle for individual existence. At heart, all prayers are for preservation, the burden of all litanies is a begging for Life.

This end, these benefits, have been sought by the cults of the world through one of two theories.

The one, that which characterizes the earliest and the crudest religions, teaches that man escapes dangers and secures safety by the performance or avoidance of certain actions. He may credit this or that myth, he may hold to one or many gods; this is unimportant; but he must not fail in the penance or the sacred dance, he must not touch that which is taboo, or he is in peril. The life of these cults is the Deed, their expression is the Rite.

Higher religions discern the inefficacy of the mere Act. They rest their claim on Belief. They establish dogmas, the mental acceptance of which is the one thing needful. In them mythology passes into theology; the act is measured by its motive, the formula by the faith back of it. Their life is the Creed.

The Myth finds vigorous and congenial growth only in the first of these forms. There alone the imagination of the votary is free, there alone it is not fettered by a symbol already defined.

To the student of religions the interest of the Myth is not that of an infantile attempt to philosophize, but as it illustrates the intimate and immediate relations which the religion in which it grew bore to the individual life. Thus examined, it reveals the inevitable destinies of men and of nations as bound up with their forms of worship.

These general considerations appear to me to be needed for the proper understanding of the study I am about to make. It concerns itself with some of the religions which were developed on the American continent before its discovery. My object is to present from them a series of myths curiously similar in features, and to see if one simple and general explanation of them can be found.

The processes of myth-building among American tribes were much the same as elsewhere. These are now too generally familiar to need specification here, beyond a few which I have found particularly noticeable.

At the foundation of all myths lies the mental process of personification, which finds expression in the rhetorical figure of prosopopeia. The definition of this, however, must be extended from the mere representation of inanimate things as animate, to include also the representation of irrational beings as rational, as in the “animal myths,” a most common form of religious story among primitive people.

Some languages favor these forms of personification much more than others, and most of the American languages do so in a marked manner, by the broad grammatical distinctions they draw between animate and inanimate objects, which distinctions must invariably be observed. They cannot say “the boat moves” without specifying whether the boat is an animate object or not, or whether it is to be considered animate, for rhetorical purposes, at the time of speaking.

The sounds of words have aided greatly in myth building. Names and words which are somewhat alike in sound, paronyms, as they are called by grammarians, may be taken or mistaken one for the other. Again, many myths spring from homonymy, that is, the sameness in sound of words with difference in signification. Thus coatl, in the Aztec tongue, is a word frequently appearing in the names of divinities. It has three entirely different meanings, to wit, a serpent, a guest and twins. Now, whichever one of these was originally meant, it would be quite certain to be misunderstood, more or less, by later generations, and myths would arise to explain the several possible interpretations of the word—as, in fact, we find was the case.

Closely allied to this is what has been called otosis. This is the substitution of a familiar word for an archaic or foreign one of similar sound but wholly diverse meaning. This is a very common occurrence and easily leads to myth making. For example, there is a cave, near Chattanooga, which has the Cherokee name Nik-a-jak. This the white settlers have transformed into Nigger Jack, and are prepared with a narrative of some runaway slave to explain the cognomen. It may also occur in the same language. In an Algonkin dialect missi wabu means “the great light of the dawn;” and a common large rabbit was called missabo; at some period the precise meaning of the former words was lost, and a variety of interesting myths of the daybreak were transferred to a supposed huge rabbit! Rarely does there occur a more striking example of how the deteriorations of language affect mythology.

Aztlan, the mythical land whence the Aztec speaking tribes were said to have come, and from which they derived their name, means “the place of whiteness;” but the word was similar to Aztatlan, which would mean “the place of herons,” some spot where these birds would love to congregate, from aztatl, the heron, and in after ages, this latter, as the plainer and more concrete signification, came to prevail, and was adopted by the myth-makers.

Polyonomy is another procedure often seen in these myths. A divinity has several or many titles; one or another of these becomes prominent, and at last obscures in a particular myth or locality the original personality of the hero of the tale. In America this is most obvious in Peru.

Akin to this is what Prof. Max Mueller has termed henotheism. In this mental process one god or one form of a god is exalted beyond all others, and even addressed as the one, only, absolute and supreme deity. Such expressions are not to be construed literally as evidences of a monotheism, but simply that at that particular time the worshiper's mind was so filled with the power and majesty of the divinity to whom he appealed, that he applied to him these superlatives, very much as he would to a great ruler. The next day he might apply them to another deity, without any hypocrisy or sense of logical contradiction. Instances of this are common in the Aztec prayers which have been preserved.

One difficulty encountered in Aryan mythology is extremely rare in America, and that is, the adoption of foreign names. A proper name without a definite concrete significance in the tongue of the people who used it is almost unexampled in the red race. A word without a meaning was something quite foreign to their mode of thought. One of our most eminent students.[1] has justly said: “Every Indian synthesis—names of persons and places not excepted—must preserve the consciousness of its roots, and must not only have a meaning, but be so framed as to convey that meaning with precision, to all who speak the language to which it belongs.” Hence, the names of their divinities can nearly always be interpreted, though for the reasons above given the most obvious and current interpretation is not in every case the correct one.

[1: J. Hammond Trumbull, On the Composition of Indian Geographical Names, p. 3 (Hartford, 1870).]

As foreign names were not adopted, so the mythology of one tribe very rarely influenced that of another. As a rule, all the religions were tribal or national, and their votaries had no desire to extend them. There was little of the proselytizing spirit among the red race. Some exceptions can be pointed out to this statement, in the Aztec and Peruvian monarchies. Some borrowing seems to have been done either by or from the Mayas; and the hero-myth of the Iroquois has so many of the lineaments of that of the Algonkins that it is difficult to believe that it was wholly independent of it. But, on the whole, the identities often found in American myths are more justly attributable to a similarity of surroundings and impressions than to any other cause.

The diversity and intricacy of American mythology have been greatly fostered by the delight the more developed nations took in rhetorical figures, in metaphor and simile, and in expressions of amplification and hyperbole. Those who imagine that there was a poverty of resources in these languages, or that their concrete form hemmed in the mind from the study of the abstract, speak without knowledge. One has but to look at the inexhaustible synonymy of the Aztec, as it is set forth by Olmos or Sahagun, or at its power to render correctly the refinements of scholastic theology, to see how wide of the fact is any such opinion. And what is true of the Aztec, is not less so of the Qquichua and other tongues.

I will give an example, where the English language itself falls short of the nicety of the Qquichua in handling a metaphysical tenet. Cay in Qquichua expresses the real being of things, the essentia ; as, runap caynin, the being of the human race, humanity in the abstract; but to convey the idea of actual being, the existentia as united to the essentia, we must add the prefix cascan, and thus have runap-cascan-caynin, which strictly means “the essence of being in general, as existent in humanity.”.[1] I doubt if the dialect of German metaphysics itself, after all its elaboration, could produce in equal compass a term for this conception. In Qquichua, moreover, there is nothing strained and nothing foreign in this example; it is perfectly pure, and in thorough accord with the genius of the tongue.

[1: “El ser existente de hombre, que es el modo de estar el primer ser que es la essentia que en Dios y los Angeles y el hombre es modo personal.” Diego Gonzalez Holguin, Vocabvlario de la Lengva Qqichua, o del Inca; sub voce, Cay. (Ciudad de los Reyes, 1608.)]

I take some pains to impress this fact, for it is an important one in estimating the religious ideas of the race. We must not think we have grounds for skepticism if we occasionally come across some that astonish us by their subtlety. Such are quite in keeping with the psychology and languages of the race we are studying.

Yet, throughout America, as in most other parts of the world, the teaching of religious tenets was twofold, the one popular, the other for the initiated, an esoteric and an exoteric doctrine. A difference in dialect was assiduously cultivated, a sort of “sacred language" being employed to conceal while it conveyed the mysteries of faith. Some linguists think that these dialects are archaic forms of the language, the memory of which was retained in ceremonial observances; others maintain that they were simply affectations of expression, and form a sort of slang, based on the every day language, and current among the initiated. I am inclined to the latter as the correct opinion, in many cases.

Whichever it was, such a sacred dialect is found in almost all tribes. There are fragments of it from the cultivated races of Mexico, Yucatan and Peru; and at the other end of the scale we may instance the Guaymis, of Darien, naked savages, but whose “chiefs of the law,” we are told, taught “the doctrines of their religion in a peculiar idiom, invented for the purpose, and very different from the common language.”.[1]

[1: Franco, Noticia de los Indios Guaymies y de sus Costumbres, p. 20, in Pinart, Coleccion de Linguistica y Etnografia Americana. Tom. iv.]

This becomes an added difficulty in the analysis of myths, as not only were the names of the divinities and of localities expressed in terms in the highest degree metaphorical, but they were at times obscured by an affected pronunciation, devised to conceal their exact derivation.

The native tribes of this Continent had many myths, and among them there was one which was so prominent, and recurred with such strangely similar features in localities widely asunder, that it has for years attracted my attention, and I have been led to present it as it occurs among several nations far apart, both geographically and in point of culture. This myth is that of the national hero, their mythical civilizer and teacher of the tribe, who, at the same time, was often identified with the supreme deity and the creator of the world. It is the fundamental myth of a very large number of American tribes, and on its recognition and interpretation depends the correct understanding of most of their mythology and religious life.

The outlines of this legend are to the effect that in some exceedingly remote time this divinity took an active part in creating the world and in fitting it to be the abode of man, and may himself have formed or called forth the race. At any rate, his interest in its advancement was such that he personally appeared among the ancestors of the nation, and taught them the useful arts, gave them the maize or other food plants, initiated them into the mysteries of their religious rites, framed the laws which governed their social relations, and having thus started them on the road to self development, he left them, not suffering death, but disappearing in some way from their view. Hence it was nigh universally expected that at some time he would return.

The circumstances attending the birth of these hero-gods have great similarity. As a rule, each is a twin or one of four brothers born at one birth; very generally at the cost of their mother's life, who is a virgin, or at least had never been impregnated by mortal man. The hero is apt to come into conflict with his brother, or one of his brothers, and the long and desperate struggle resulting, which often involved the universe in repeated destructions, constitutes one of the leading topics of the myth-makers. The duel is not generally—not at all, I believe, when we can get at the genuine native form of the myth—between a morally good and an evil spirit, though, undoubtedly, the one is more friendly and favorable to the welfare of man than the other.

The better of the two, the true hero-god, is in the end triumphant, though the national temperament represented this variously. At any rate, his people are not deserted by him, and though absent, and perhaps for a while driven away by his potent adversary, he is sure to come back some time or other.

The place of his birth is nearly always located in the East; from that quarter he first came when he appeared as a man among men; toward that point he returned when he disappeared; and there he still lives, awaiting the appointed time for his reappearance.

Whenever the personal appearance of this hero-god is described, it is, strangely enough, represented to be that of one of the white race, a man of fair complexion, with long, flowing beard, with abundant hair, and clothed in ample and loose robes. This extraordinary fact naturally suggests the gravest suspicion that these stories were made up after the whites had reached the American shores, and nearly all historians have summarily rejected their authenticity, on this account. But a most careful scrutiny of their sources positively refutes this opinion. There is irrefragable evidence that these myths and this ideal of the hero-god, were intimately known and widely current in America long before any one of its millions of inhabitants had ever seen a white man. Nor is there any difficulty in explaining this, when we divest these figures of the fanciful garbs in which they have been clothed by the religious imagination, and recognize what are the phenomena on which they are based, and the physical processes whose histories they embody. To show this I will offer, in the most concise terms, my interpretation of their main details.

The most important of all things to life is Light. This the primitive savage felt, and, personifying it, he made Light his chief god. The beginning of the day served, by analogy, for the beginning of the world. Light comes before the sun, brings it forth, creates it, as it were. Hence the Light-God is not the Sun-God, but his Antecedent and Creator.

The light appears in the East, and thus defines that cardinal point, and by it the others are located. These points, as indispensable guides to the wandering hordes, became, from earliest times, personified as important deities, and were identified with the winds that blew from them, as wind and rain gods. This explains the four brothers, who were nothing else than the four cardinal points, and their mother, who dies in producing them, is the eastern light, which is soon lost in the growing day. The East, as their leader, was also the supposed ruler of the winds, and thus god of the air and rain. As more immediately connected with the advent and departure of light, the East and West are twins, the one of which sends forth the glorious day-orb, which the other lies in wait to conquer. Yet the light-god is not slain. The sun shall rise again in undiminished glory, and he lives, though absent.

By sight and light we see and learn. Nothing, therefore, is more natural than to attribute to the light-god the early progress in the arts of domestic and social life. Thus light came to be personified as the embodiment of culture and knowledge, of wisdom, and of the peace and prosperity which are necessary for the growth of learning.

The fair complexion of these heroes is nothing but a reference to the white light of the dawn. Their ample hair and beard are the rays of the sun that flow from his radiant visage. Their loose and large robes typify the enfolding of the firmament by the light and the winds.

This interpretation is nowise strained, but is simply that which, in Aryan mythology, is now universally accepted for similar mythological creations. Thus, in the Greek Phoebus and Perseus, in the Teutonic Lif, and in the Norse Baldur, we have also beneficent hero-gods, distinguished by their fair complexion and ample golden locks. “Amongst the dark as well as amongst the fair races, amongst those who are marked by black hair and dark eyes, they exhibit the same unfailing type of blue-eyed heroes whose golden locks flow over their shoulders, and whose faces gleam as with the light of the new risen sun.”.[1]

[1: Sir George W. Cox, An Introduction to the Science of Comparative Mythology and Folk-Lore, p. 17.]

Everywhere, too, the history of these heroes is that of a struggle against some potent enemy, some dark demon or dragon, but as often against some member of their own household, a brother or a father.

The identification of the Light-God with the deity of the winds is also seen in Aryan mythology. Hermes, to the Greek, was the inventor of the alphabet, music, the cultivation of the olive, weights and measures, and such humane arts. He was also the messenger of the gods, in other words, the breezes, the winds, the air in motion. His name Hermes, Hermeias, is but a transliteration of the Sanscrit Sarameyas, under which he appears in the Vedic songs, as the son of Sarama, the Dawn. Even his character as the master thief and patron saint of the light-fingered gentry, drawn from the way the winds and breezes penetrate every crack and cranny of the house, is absolutely repeated in the Mexican hero-god Quetzalcoatl, who was also the patron of thieves. I might carry the comparison yet further, for as Sarameyas is derived from the root sar, to creep, whence serpo, serpent, the creeper, so the name Quetzalcoatl can be accurately translated, “the wonderful serpent.” In name, history and functions the parallelism is maintained throughout.

Or we can find another familiar myth, partly Aryan, partly Semitic, where many of the same outlines present themselves. The Argive Thebans attributed the founding of their city and state to Cadmus. He collected their ancestors into a community, gave them laws, invented the alphabet of sixteen letters, taught them the art of smelting metals, established oracles, and introduced the Dyonisiac worship, or that of the reproductive principle. He subsequently left them and lived for a time with other nations, and at last did not die, but was changed into a dragon and carried by Zeus to Elysion.

The birthplace of this culture hero was somewhere far to the eastward of Greece, somewhere in “the purple land” (Phoenicia); his mother was “the far gleaming one” (Telephassa); he was one of four children, and his sister was Europe, the Dawn, who was seized and carried westward by Zeus, in the shape of a white bull. Cadmus seeks to recover her, and sets out, following the westward course of the sun. “There can be no rest until the lost one is found again. The sun must journey westward until he sees again the beautiful tints which greeted his eyes in the morning.”.[1] Therefore Cadmus leaves the purple land to pursue his quest. It is one of toil and struggle. He has to fight the dragon offspring of Ares and the bands of armed men who spring from the dragon's teeth which were sown, that is, the clouds and gloom of the overcast sky. He conquers, and is rewarded, but does not recover his sister.

[1: Sir George W. Cox, Ibid., p. 76.]

When we find that the name Cadmus is simply the Semitic word kedem, the east, and notice all this mythical entourage, we see that this legend is but a lightly veiled account of the local source and progress of the light of day, and of the advantages men derive from it. Cadmus brings the letters of the alphabet from the east to Greece, for the same reason that in ancient Maya myth Itzamna, “son of the mother of the morning,” brought the hieroglyphs of the Maya script also from the east to Yucatan—because both represent the light by which we see and learn.

Egyptian mythology offers quite as many analogies to support this interpretation of American myths as do the Aryan god-stories.

The heavenly light impregnates the virgin from whom is born the sun-god, whose life is a long contest with his twin brother. The latter wins, but his victory is transient, for the light, though conquered and banished by the darkness, cannot be slain, and is sure to return with the dawn, to the great joy of the sons of men. This story the Egyptians delighted to repeat under numberless disguises. The groundwork and meaning are the same, whether the actors are Osiris, Isis and Set, Ptah, Hapi and the Virgin Cow, or the many other actors of this drama. There, too, among a brown race of men, the light-god was deemed to be not of their own hue, but “light colored, white or yellow,” of comely countenance, bright eyes and golden hair. Again, he is the one who invented the calendar, taught the arts, established the rituals, revealed the medical virtues of plants, recommended peace, and again was identified as one of the brothers of the cardinal points.[1]

[1: See Dr. C.P. Tiele, History of the Egyptian Religion, pp. 93, 95, 99, et al.]

The story of the virgin-mother points, in America as it did in the old world, to the notion of the dawn bringing forth the sun. It was one of the commonest myths in both continents, and in a period of human thought when miracles were supposed to be part of the order of things had in it nothing difficult of credence. The Peruvians, for instance, had large establishments where were kept in rigid seclusion the “virgins of the sun.” Did one of these violate her vow of chastity, she and her fellow criminal were at once put to death; but did she claim that the child she bore was of divine parentage, and the contrary could not be shown, then she was feted as a queen, and the product of her womb was classed among princes, as a son of the sun. So, in the inscription at Thebes, in the temple of the virgin goddess Mat, we read where she says of herself: “My garment no man has lifted up; the fruit that I have borne was begotten of the sun.”.[1]

[1: “[Greek: Ton emon chitona oudeis apechaluphen on ego charpon etechan, aelios egeneto.]” Proclus, quoted by Tiele, ubi supra, p. 204, note.]

I do not venture too much in saying that it were easy to parallel every event in these American hero-myths, every phase of character of the personages they represent, with others drawn from Aryan and Egyptian legends long familiar to students, and which now are fully recognized as having in them nothing of the substance of history, but as pure creations of the religious imagination working on the processes of nature brought into relation to the hopes and fears of men.

If this is so, is it not time that we dismiss, once for all, these American myths from the domain of historical traditions? Why should we try to make a king of Itzamna, an enlightened ruler of Quetzalcoatl, a cultured nation of the Toltecs, when the proof is of the strongest, that every one of these is an absolutely baseless fiction of mythology? Let it be understood, hereafter, that whoever uses these names in an historical sense betrays an ignorance of the subject he handles, which, were it in the better known field of Aryan or Egyptian lore, would at once convict him of not meriting the name of scholar.

In European history the day has passed when it was allowable to construct primitive chronicles out of fairy tales and nature myths. The science of comparative mythology has assigned to these venerable stories a different, though not less noble, interpretation. How much longer must we wait to see the same canons of criticism applied to the products of the religious fancy of the red race?

Furthermore, if the myths of the American nations are shown to be capable of a consistent interpretation by the principles of comparative mythology, let it be recognized that they are neither to be discarded because they resemble some familiar to their European conquerors, nor does that similarity mean that they are historically derived, the one from the other. Each is an independent growth, but as each is the reflex in a common psychical nature of the same phenomena, the same forms of expression were adopted to convey them.

Section 2. The Iroquois Myth of Ioskeha.

Nearly all that vast area which lies between Hudson Bay and the Savannah river, and the Mississippi river and the Atlantic coast, was peopled at the epoch of the discovery by the members of two linguistic families—the Algonkins and the Iroquois. They were on about the same plane of culture, but differed much in temperament and radically in language. Yet their religious notions were not dissimilar.

Alas! alas! alas! alas! alas! alas!

In the home of our ancestors this creature was a fearful

thing.

In the temple of Tezcatzoncatl

he aids those who cry to him,

he gives them to drink;

the god gives to drink to those who cry to him. In the temple by

the water-reeds

the god aids those who call upon him,

he gives them to drink;

the god aids those who cry unto him.

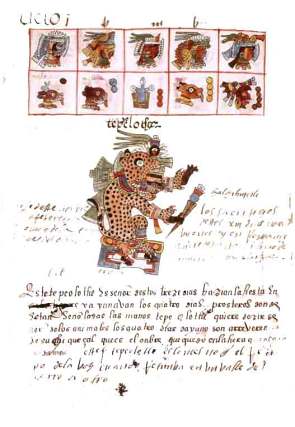

Tezcatzoncatl was one of the chief gods of the native inebriating liquor, the pulque. Its effects were recognized as most disastrous, as is seen from his other names, Tequechmecaniani, “he who hangs people,” and Teatlahuiani, “he who drowns people.” Sahagun remarks, “They always regarded the pulque as a bad and dangerous article.” The word Totochtin, plural of tochtli, rabbit, was applied to drunkards, and also to some of the deities of special forms of drunkenness.

The first verse is merely a series of lamentations. The second speaks of the sad effects of the pulque in ancient times. (On Colhuacan see Notes to Hymn XIII.)

From Rig Veda Americanus

Among all the Algonkin tribes whose myths have been preserved we find much is said about a certain Giant Rabbit, to whom all sorts of powers were attributed. He was the master of all animals; he was the teacher who first instructed men in the arts of fishing and hunting; he imparted to the Algonkins the mysteries of their religious rites; he taught them picture writing and the interpretation of dreams; nay, far more than that, he was the original ancestor, not only of their nation, but of the whole race of man, and, in fact, was none other than the primal Creator himself, who fashioned the earth and gave life to all that thereon is.

Hearing all this said about such an ignoble and weak animal as the rabbit, no wonder that the early missionaries and travelers spoke of such fables with undisguised contempt, and never mentioned them without excuses for putting on record trivialities so utter.

Yet it appears to me that under these seemingly weak stories lay a profound truth, the appreciation of which was lost in great measure to the natives themselves, but which can be shown to have been in its origin a noble myth, setting forth in not unworthy images the ceaseless and mighty rhythm of nature in the alternations of day and night, summer and winter, storm and sunshine.

I shall quote a few of these stories as told by early authorities, not adding anything to relieve their crude simplicity, and then I will see whether, when submitted to the test of linguistic analysis, this unpromising ore does not yield the pure gold of genuine mythology.

The beginning of things, according to the Ottawas and other northern Algonkins, was at a period when boundless waters covered the face of the earth. On this infinite ocean floated a raft, upon which were many species of animals, the captain and chief of whom was Michabo, the Giant Rabbit. They ardently desired land on which to live, so this mighty rabbit ordered the beaver to dive and bring him up ever so little a piece of mud. The beaver obeyed, and remained down long, even so that he came up utterly exhausted, but reported that he had not reached bottom. Then the Rabbit sent down the otter, but he also returned nearly dead and without success. Great was the disappointment of the company on the raft, for what better divers had they than the beaver and the otter?

Algonkins hunting. From Pioneers in Canada by Sir Harry Johnston

In the midst of their distress the (female) muskrat came forward and announced her willingness to make the attempt. Her proposal was received with derision, but as poor help is better than none in an emergency, the Rabbit gave her permission, and down she dived. She too remained long, very long, a whole day and night, and they gave her up for lost. But at length she floated to the surface, unconscious, her belly up, as if dead. They hastily hauled her on the raft and examined her paws one by one. In the last one of the four they found a small speck of mud. Victory! That was all that was needed. The muskrat was soon restored, and the Giant Rabbit, exerting his creative power, moulded the little fragment of soil, and as he moulded it, it grew and grew, into an island, into a mountain, into a country, into this great earth that we all dwell upon. As it grew the Rabbit walked round and round it, to see how big it was; and the story added that he is not yet satisfied; still he continues his journey and his labor, walking forever around and around the earth and ever increasing it more and more.

The animals on the raft soon found homes on the new earth. But it had yet to be covered with forests, and men were not born. The Giant Rabbit formed the trees by shooting his arrows into the soil, which became tree trunks, and, transfixing them with other arrows, these became branches; and as for men, some said he formed them from the dead bodies of certain animals, which in time became the “totems” of the Algonkin tribes; but another and probably an older and truer story was that he married the muskrat which had been of such service to him, and from this union were born the ancestors of the various races of mankind which people the earth.

Nor did he neglect the children he had thus brought into the world of his creation. Having closely studied how the spider spreads her web to catch flies, he invented the art of knitting nets for fish, and taught it to his descendants; the pieces of native copper found along the shores of Lake Superior he took from his treasure house inside the earth, where he sometimes lives. It is he who is the Master of Life, and if he appears in a dream to a person in danger, it is a certain sign of a lucky escape. He confers fortune in the chase, and therefore the hunters invoke him, and offer him tobacco and other dainties, placing them in the clefts of rocks or on isolated boulders. Though called the Giant Rabbit, he is always referred to as a man, a giant or demigod perhaps, but distinctly as of human nature, the mighty father or elder brother of the race.[1]

[1: The writers from whom I have taken this myth are Nicolas Perrot, Memoire sur les Meurs, Coustumes et Relligion des Sauvages de l'Amerique Septentrionale, written by an intelligent layman who lived among the natives from 1665 to 1699; and the various Relations des Jesuites, especially for the years 1667 and 1670.]

Such is the national myth of creation of the Algonkin tribes, as it has been handed down to us in fragments by those who first heard it. Has it any meaning? Is it more than the puerile fable of savages?

Let us see whether some of those unconscious tricks of speech to which I referred in the introductory chapter have not disfigured a true nature myth. Perhaps those common processes of language, personification and otosis, duly taken into account, will enable us to restore this narrative to its original sense.

In the Algonkin tongue the word for Giant Rabbit is Missabos, compounded from mitchi or missi, great, large, and wabos, a rabbit. But there is a whole class of related words, referring to widely different perceptions, which sound very much like wabos. They are from a general root wab, which goes to form such words of related signification as wabi, he sees, waban, the east, the Orient, wabish, white, bidaban (bid-waban), the dawn, waban, daylight, wasseia, the light, and many others. Here is where we are to look for the real meaning of the name Missabos. It originally meant the Great Light, the Mighty Seer, the Orient, the Dawn—which you please, as all distinctly refer to the one original idea, the Bringer of Light and Sight, of knowledge and life. In time this meaning became obscured, and the idea of the rabbit, whose name was drawn probably from the same root, as in the northern winters its fur becomes white, was substituted, and so the myth of light degenerated into an animal fable.

I believe that a similar analysis will explain the part which the muskrat plays in the story. She it is who brings up the speck of mud from the bottom of the primal ocean, and from this speck the world is formed by him whom we now see was the Lord of the Light and the Day, and subsequently she becomes the mother of his sons. The word for muskrat in Algonkin is wajashk, the first letter of which often suffers elision, as in nin nod-ajashkwe, I hunt muskrats. But this is almost the word for mud, wet earth, soil, ajishki. There is no reasonable doubt but that here again otosis and personification came in and gave the form and name of an animal to the original simple statement.

That statement was that from wet mud dried by the sunlight, the solid earth was formed; and again, that this damp soil was warmed and fertilized by the sunlight, so that from it sprang organic life, even man himself, who in so many mythologies is “the earth born,” homo ab humo, homo chamaigenes.[1]

[1: Mr. J. Hammond Trumbull has pointed out that in Algonkin the words for father, osh, mother, okas, and earth, ohke (Narraganset dialect), can all be derived, according to the regular rules of Algonkin grammar, from the same verbal root, signifying “to come out of, or from.” (Note to Roger Williams' Key into the Language of America, p. 56). Thus the earth was, in their language, the parent of the race, and what more natural than that it should become so in the myth also?]

This, then, is the interpretation I have to offer of the cosmogonical myth of the Algonkins. Does some one object that it is too refined for those rude savages, or that it smacks too much of reminiscences of old-world teachings? My answer is that neither the early travelers who wrote it down, nor probably the natives who told them, understood its meaning, and that not until it is here approached by modern methods of analysis, has it ever been explained. Therefore it is impossible to assign to it other than an indigenous and spontaneous origin in some remote period of Algonkin tribal history.

After the darkness of the night, man first learns his whereabouts by the light kindling in the Orient; wandering, as did the primitive man, through pathless forests, without a guide, the East became to him the first and most important of the fixed points in space; by it were located the West, the North, the South; from it spread the welcome dawn; in it was born the glorious sun; it was full of promise and of instruction; hence it became to him the home of the gods of life and light and wisdom.

As the four cardinal points are determined by fixed physical relations, common to man everywhere, and are closely associated with his daily motions and well being, they became prominent figures in almost all early myths, and were personified as divinities. The winds were classified as coming from them, and in many tongues the names of the cardinal points are the same as those of the winds that blow from them. The East, however, has, in regard to the others, a pre-eminence, for it is not merely the home of the east wind, but of the light and the dawn as well. Hence it attained a marked preponderance in the myths; it was either the greatest, wisest and oldest of the four brothers, who, by personification, represented the cardinal points and the four winds, or else the Light-God was separated from the quadruplet and appears as a fifth personage governing the other four, and being, in fact, the supreme ruler of both the spiritual and human worlds.

Such was the mental processes which took place in the Algonkin mind, and gave rise to two cycles of myths, the one representing Wabun or Michabo as one of four brothers, whose names are those of the cardinal points, the second placing him above them all.

The four brothers are prominent characters in Algonkin legend, and we shall find that they recur with extraordinary frequency in the mythology of all American nations. Indeed, I could easily point them out also in the early religious conceptions of Egypt and India, Greece and China, and many other old-world lands, but I leave these comparisons to those who wish to treat of the principles of general mythology.

According to the most generally received legend these four brothers were quadruplets—born at one birth—and their mother died in bringing them into life. Their names are given differently by the various tribes, but are usually identical with the four points of the compass, or something relating to them. Wabun the East, Kabun the West, Kabibonokka the North, and Shawano the South, are, in the ordinary language of the interpreters, the names applied to them. Wabun was the chief and leader, and assigned to his brothers their various duties, especially to blow the winds.

These were the primitive and chief divinities of the Algonkin race in all parts of the territory they inhabited. When, as early as 1610, Captain Argoll visited the tribes who then possessed the banks of the river Potomac, and inquired concerning their religion, they replied, “We have five gods in all; our chief god often appears to us in the form of a mighty great hare; the other four have no visible shape, but are indeed the four winds, which keep the four corners of the earth.”.[1]

[1: William Strachey, Historie of Travaile into Virginia, p. 98.]

Here we see that Wabun, the East, was distinguished from Michabo (missi-wabun), and by a natural and transparent process, the eastern light being separated from the eastern wind, the original number four was increased to five. Precisely the same differentiation occurred, as I shall show, in Mexico, in the case of Quetzalcoatl, as shown in his Yoel, or Wheel of the Winds, which was his sacred pentagram.

Or I will further illustrate this development by a myth of the Huarochiri Indians, of the coast of Peru. They related that in the beginning of things there were five eggs on the mountain Condorcoto. In due course of time these eggs opened and from them came forth five falcons, who were none other than the Creator of all things, Pariacaca, and his brothers, the four winds. By their magic power they transformed themselves into men and went about the world performing miracles, and in time became the gods of that people.[1]

[1: Doctor Francisco de Avila, Narrative of the Errors and False Gods of the Indians of Huarochiri (1608). This interesting document has been partly translated by Mr. C.B. Markham, and published in one of the volumes of the Hackluyt Society's series.]

These striking similarities show with what singular uniformity the religious sense developes itself in localities the furthest asunder.

Returning to Michabo, the duplicate nature thus assigned him as the Light-God, and also the God of the Winds and the storms and rains they bring, led to the production of two cycles of myths which present him in these two different aspects. In the one he is, as the god of light, the power that conquers the darkness, who brings warmth and sunlight to the earth and knowledge to men. He was the patron of hunters, as these require the light to guide them on their way, and must always direct their course by the cardinal points.

The morning star, which at certain seasons heralds the dawn, was sacred to him, and its name in Ojibway is Wabanang, from Waban, the east. The rays of light are his servants and messengers. Seated at the extreme east, “at the place where the earth is cut off,” watching in his medicine lodge, or passing his time fishing in the endless ocean which on every side surrounds the land, Michabo sends forth these messengers, who, in the myth, are called Gijigouai, which means “those who make the day,” and they light the world. He is never identified with the sun, nor was he supposed to dwell in it, but he is distinctly the impersonation of light.[1]

[1: See H.R. Schoolcraft, Indian Tribes, Vol. v, pp. 418, 419. Relations des Jesuites, 1634, p. 14, 1637, p. 46.]

In one form of the myth he is the grandson of the Moon, his father is the West Wind, and his mother, a maiden who has been fecundated miraculously by the passing breeze, dies at the moment of giving him birth. But he did not need the fostering care of a parent, for he was born mighty of limb and with all knowledge that it is possible to attain.[1] Immediately he attacked his father, and a long and desperate struggle took place. “It began on the mountains. The West was forced to give ground. His son drove him across rivers and over mountains and lakes, and at last, he came to the brink of the world. 'Hold!' cried he, 'my son, you know my power, and that it is impossible to kill me.'“ The combat ceased, the West acknowledging the Supremacy of his mighty son.[2]

[1: In the Ojibway dialect of the Algonkins, the word for day, sky or heaven, is gijig. This same word as a verb means to be an adult, to be ripe (of fruits), to be finished, complete. Rev. Frederick Baraga, A Dictionary of the Olchipwe Language, Cincinnati, 1853. This seems to correspond with the statement in the myth.]

[2: H.E. Schoolcraft, Algic Researches, vol. i, pp. 135, et seq.]

It is scarcely possible to err in recognizing under this thin veil of imagery a description of the daily struggle between light and darkness, day and night. The maiden is the dawn from whose virgin womb rises the sun in the fullness of his glory and might, but with his advent the dawn itself disappears and dies. The battle lasts all day, beginning when the earliest rays gild the mountain tops, and continues until the West is driven to the edge of the world. As the evening precedes the morning, so the West, by a figure of speech, may be said to fertilize the Dawn.

In another form of the story the West was typified as a flint stone, and the twin brother of Michabo. The feud between them was bitter, and the contest long and dreadful. The face of the land was seamed and torn by the wrestling of the mighty combatants, and the Indians pointed out the huge boulders on the prairies as the weapons hurled at each other by the enraged brothers. At length Michabo mastered his fellow twin and broke him into pieces. He scattered the fragments over the earth, and from them grew fruitful vines.

A myth which, like this, introduces the flint stone as in some way connected with the early creative forces of nature, recurs at other localities on the American continent very remote from the home of the Algonkins. In the calendar of the Aztecs the day and god Tecpatl, the Flint-Stone, held a prominent position. According to their myths such a stone fell from heaven at the beginning of things and broke into sixteen hundred pieces, each of which became a god. The Hun-pic-tok, Eight Thousand Flints, of the Mayas, and the Toh of the Kiches, point to the same association.[1]

[1: Brasseur de Bourbourg, Dissertation sur les Mythes de l'Antiquite Americaine, Sec.vii.]

Probably the association of ideas was not with the flint as a fire-stone, though the fact that a piece of flint struck with a nodule of pyrites will emit a spark was not unknown. But the flint was everywhere employed for arrow and lance heads. The flashes of light, the lightning, anything that darted swiftly and struck violently, was compared to the hurtling arrow or the whizzing lance. Especially did this apply to the phenomenon of the lightning. The belief that a stone is shot from the sky with each thunderclap is shown in our word “thunderbolt,” and even yet the vulgar in many countries point out certain forms of stones as derived from this source. As the refreshing rain which accompanies the thunder gust instills new life into vegetation, and covers the ground parched by summer droughts with leaves and grass, so the statement in the myth that the fragments of the flint-stone grew into fruitful vines is an obvious figure of speech which at first expressed the fertilizing effects of the summer showers.

In this myth Michabo, the Light-God, was represented to the native mind as still fighting with the powers of Darkness, not now the darkness of night, but that of the heavy and gloomy clouds which roll up the sky and blind the eye of day. His weapons are the lightning and the thunderbolt, and the victory he achieves is turned to the good of the world he has created.

This is still more clearly set forth in an Ojibway myth. It relates that in early days there was a mighty serpent, king of all serpents, whose home was in the Great Lakes. Increasing the waters by his magic powers, he began to flood the land, and threatened its total submergence. Then Michabo rose from his couch at the sun-rising, attacked the huge reptile and slew it by a cast of his dart. He stripped it of its skin, and clothing himself in this trophy of conquest, drove all the other serpents to the south.[1] As it is in the south that, in the country of the Ojibways, the lightning is last seen in the autumn, and as the Algonkins, both in their language and pictography, were accustomed to assimilate the lightning in its zigzag course to the sinuous motion of the serpent,[2] the meteorological character of this myth is very manifest.

[1: H.R. Schoolcraft, Algic Researches, Vol. i, p. 179, Vol. ii, p. 117. The word animikig in Ojibway means “it thunders and lightnings;” in their myths this tribe says that the West Wind is created by Animiki, the Thunder. (Ibid. Indian Tribes, Vol. v, p. 420.)]

[2: When Father Buteux was among the Algonkins, in 1637, they explained to him the lightning as “a great serpent which the Manito vomits up.” (Relation de la Nouvelle France, An. 1637, p. 53.) According to John Tanner, the symbol for the lightning in Ojibway pictography was a rattlesnake. (Narrative, p. 351.)]

Thus we see that Michabo, the hero-god of the Algonkins, was both the god of light and day, of the winds and rains, and the creator, instructor and teacher of mankind. The derivation of his name shows unmistakably that the earliest form under which he was a mythological existence was as the light-god. Later he became more familiar as god of the winds and storms, the hero of the celestial warfare of the air-currents.

This is precisely the same change which we are enabled to trace in the early transformations of Aryan religion. There, also, the older god of the sky and light, Dyaus, once common to all members of the Indo-European family, gave way to the more active deities, Indra, Zeus and Odin, divinities of the storm and the wind, but which, after all, are merely other aspects of the ancient deity, and occupied his place to the religious sense.[1] It is essential, for the comprehension of early mythology, to understand this twofold character, and to appreciate how naturally the one merges into and springs out of the other.

[1: This transformation is well set forth in Mr. Charles Francis Keary's Outlines of Primitive Belief Among the Indo-European Races (London, 1882), chaps, iv, vii. He observes: “The wind is a far more physical and less abstract conception than the sky or heaven; it is also a more variable phenomenon; and by reason of both these recommendations the wind-god superseded the older Dyaus. * * * Just as the chief god of Greece, having descended to be a divinity of storm, was not content to remain only that, but grew again to some likeness of the older Dyaus, so Odhinn came to absorb almost all the qualities which belong of right to a higher god. Yet he did this without putting off his proper nature. He was the heaven as well as the wind; he was the All-father, embracing all the earth and looking down upon mankind.”]

In almost every known religion the bird is taken as a symbol of the sky, the clouds and the winds. It is not surprising, therefore, to find that by the Algonkins birds were considered, especially singing birds, as peculiarly sacred to Michabo. He was their father and protector. He himself sent forth the east wind from his home at the sun-rising; but he appointed an owl to create the north wind, which blows from the realms of darkness and cold; while that which is wafted from the sunny south is sent by the butterfly.[1]

[1: H.R. Schoolcraft, Algic Researches, Vol. i, p. 216. Indian Tribes, Vol. v, p. 420.]

Michabo was thus at times the god of light, at others of the winds, and as these are the rain-bringers, he was also at times spoken of as the god of waters. He was said to have scooped out the basins of the lakes and to have built the cataracts in the rivers, so that there should be fish preserves and beaver dams.[1]

[1: “Michabou, le Dieu des Eaux,” etc. Charlevoix, Journal Historique, p. 281 (Paris, 1721).]

In his capacity as teacher and instructor, it was he who had pointed out to the ancestors of the Indians the roots and plants which are fit for food, and which are of value as medicine; he gave them fire, and recommended them never to allow it to become wholly extinguished in their villages; the sacred rites of what is called the meday or ordinary religious ceremonial were defined and taught by him; the maize was his gift, and the pleasant art of smoking was his invention.[1]

[1: John Tanner, Narrative of Captivity and Adventure, p. 351. Schoolcraft, Indian Tribes, Vol. v, p. 420, etc.]

A curious addition to the story was told the early Swedish settlers on the river Delaware by the Algonkin tribe which inhabited its shores. These related that their various arts of domestic life and the chase were taught them long ago by a venerable and eloquent man who came to them from a distance, and having instructed them in what was desirable for them to know, he departed, not to another region or by the natural course of death, but by ascending into the sky. They added that this ancient and beneficent teacher wore a long beard.[1] We might suspect that this last trait was thought of after the bearded Europeans had been seen, did it not occur so often in myths elsewhere on the continent, and in relics of art finished long before the discovery, that another explanation must be found for it. What this is I shall discuss when I come to speak of the more Southern myths, whose heroes were often “white and bearded men from the East.”

[1: Thomas Campanius (Holm), Description of the Province of New Sweden, book iii, ch. xi. Campanius does not give the name of the hero-god, but there can be no doubt that it was the “Great Hare.”]

The sources from which I draw the elements of the Iroquois hero-myth of Ioskeha are mainly the following: Relations de la Nouvelle France, 1636, 1640, 1671, etc. Sagard, Histoire du Canada, pp. 451, 452 (Paris, 1636); David Cusick, Ancient History of the Six Nations, and manuscript material kindly furnished me by Horatio Hale, Esq., who has made a thorough study of the Iroquois history and dialects.

Ataensic in the primeval waters

The most ancient myth of the Iroquois represents this earth as covered with water, in which dwelt aquatic animals and monsters of the deep. Far above it were the heavens, peopled by supernatural beings. At a certain time one of these, a woman, by name Ataensic, threw herself through a rift in the sky and fell toward the earth. What led her to this act was variously recorded. Some said that it was to recover her dog which had fallen through while chasing a bear. Others related that those who dwelt in the world above lived off the fruit of a certain tree; that the husband of Ataensic, being sick, dreamed that to restore him this tree must be cut down; and that when Ataensic dealt it a blow with her stone axe, the tree suddenly sank through the floor of the sky, and she precipitated herself after it.

However the event occurred, she fell from heaven down to the primeval waters. There a turtle offered her his broad back as a resting-place until, from a little mud which was brought her, either by a frog, a beaver or some other animal, she, by magic power, formed dry land on which to reside.

At the time she fell from the sky she was pregnant, and in due time was delivered of a daughter, whose name, unfortunately, the legend does not record. This daughter grew to womanhood and conceived without having seen a man, for none was as yet created. The product of her womb was twins, and even before birth one of them betrayed his restless and evil nature, by refusing to be born in the usual manner, but insisting on breaking through his parent's side (or armpit). He did so, but it cost his mother her life. Her body was buried, and from it sprang the various vegetable productions which the new earth required to fit it for the habitation of man. From her head grew the pumpkin vine; from her breast, the maize; from her limbs, the bean and other useful esculents.

Meanwhile the two brothers grew up. The one was named Ioskeha. He went about the earth, which at that time was arid and waterless, and called forth the springs and lakes, and formed the sparkling brooks and broad rivers. But his brother, the troublesome Tawiscara, he whose obstinacy had caused their mother's death, created an immense frog which swallowed all the water and left the earth as dry as before. Ioskeha was informed of this by the partridge, and immediately set out for his brother's country, for they had divided the earth between them.

Soon he came to the gigantic frog, and piercing it in the side (or armpit), the waters flowed out once more in their accustomed ways. Then it was revealed to Ioskeha by his mother's spirit that Tawiscara intended to slay him by treachery. Therefore, when the brothers met, as they soon did, it was evident that a mortal combat was to begin.

Now, they were not men, but gods, whom it was impossible really to kill, nor even could either be seemingly slain, except by one particular substance, a secret which each had in his own keeping. As therefore a contest with ordinary weapons would have been vain and unavailing, they agreed to tell each other what to each was the fatal implement of war. Ioskeha acknowledged that to him a branch of the wild rose (or, according to another version, a bag filled with maize) was more dangerous than anything else; and Tawiscara disclosed that the horn of a deer could alone reach his vital part.

They laid off the lists, and Tawiscara, having the first chance, attacked his brother violently with a branch of the wild rose, and beat him till he lay as one dead; but quickly reviving, Ioskeha assaulted Tawiscara with the antler of a deer, and dealing him a blow in the side, the blood flowed from the wound in streams. The unlucky combatant fled from the field, hastening toward the west, and as he ran the drops of his blood which fell upon the earth turned into flint stones. Ioskeha did not spare him, but hastening after, finally slew him. He did not, however, actually kill him, for, as I have said, these were beings who could not die; and, in fact, Tawiscara was merely driven from the earth and forced to reside in the far west, where he became ruler of the spirits of the dead. These go there to dwell when they leave the bodies behind them here.

Ioskeha. In Huron mythology one of the two grandsons of the

moon. Ioskewa fought against his brother Tawiscara for supremacy.

Ioskewa had the horns of a stag as a weapon, while his brother

could only seize a wild rose.

Thus Tawiscara was defeated, and Ioskewa became the guardian

deity of the Hurons, Mohawks and Tuscaroras.

Ioskeha, returning, peaceably devoted himself to peopling the land. He opened a cave which existed in the earth and allowed to come forth from it all the varieties of animals with which the woods and prairies are peopled. In order that they might be more easily caught by men, he wounded every one in the foot except the wolf, which dodged his blow; for that reason this beast is one of the most difficult to catch. He then formed men and gave them life, and instructed them in the art of making fire, which he himself had learned from the great tortoise. Furthermore he taught them how to raise maize, and it is, in fact, Ioskeha himself who imparts fertility to the soil, and through his bounty and kindness the grain returns a hundred fold.

Nor did they suppose that he was a distant, invisible, unapproachable god. No, he was ever at hand with instruction and assistance. Was there to be a failure in the harvest, he would be seen early in the season, thin with anxiety about his people, holding in his hand a blighted ear of corn. Did a hunter go out after game, he asked the aid of Ioskeha, who would put fat animals in the way, were he so minded. At their village festivals he was present and partook of the cheer.

Once, in 1640, when the smallpox was desolating the villages of the Hurons, we are told by Father Lalemant that an Indian said there had appeared to him a beautiful youth, of imposing stature, and addressed him with these words: “Have no fear; I am the master of the earth, whom you Hurons adore under the name Ioskeha. The French wrongly call me Jesus, because they do not know me. It grieves me to see the pestilence that is destroying my people, and I come to teach you its cause and its remedy. Its cause is the presence of these strangers; and its remedy is to drive out these black robes (the missionaries), to drink of a certain water which I shall tell you of, and to hold a festival in my honor, which must be kept up all night, until the dawn of day.”

The home of Ioskeha is in the far East, at that part of the horizon where the sun rises. There he has his cabin, and there he dwells with his grandmother, the wise Ataensic. She is a woman of marvelous magical power, and is capable of assuming any shape she pleases. In her hands is the fate of all men's lives, and while Ioskeha looks after the things of life, it is she who appoints the time of death, and concerns herself with all that relates to the close of existence. Hence she was feared, not exactly as a maleficent deity, but as one whose business is with what is most dreaded and gloomy.

It was said that on a certain occasion four bold young men determined to journey to the sun-rising and visit the great Ioskeha. They reached his cabin and found him there alone. He received them affably and they conversed pleasantly, but at a certain moment he bade them hide themselves for their life, as his grandmother was coming. They hastily concealed themselves, and immediately Ataensic entered. Her magic insight had warned her of the presence of guests, and she had assumed the form of a beautiful girl, dressed in gay raiment, her neck and arms resplendent with collars and bracelets of wampum. She inquired for the guests, but Ioskeha, anxious to save them, dissembled, and replied that he knew not what she meant. She went forth to search for them, when he called them forth from their hiding place and bade them flee, and thus they escaped.

It was said of Ioskeha that he acted the part of husband to his grandmother. In other words, the myth presents the germ of that conception which the priests of ancient Egypt endeavored to express when they taught that Osiris was “his own father and his own son,” that he was the “self-generating one,” even that he was “the father of his own mother.” These are grossly materialistic expressions, but they are perfectly clear to the student of mythology. They are meant to convey to the mind the self-renewing power of life in nature, which is exemplified in the sowing and the seeding, the winter and the summer, the dry and the rainy seasons, and especially the sunset and sunrise. They are echoes in the soul of man of the ceaseless rhythm in the operations of nature, and they become the only guarantors of his hopes for immortal life.[1]

[1: Such epithets were common, in the Egyptian religion, to most of the gods of fertility. Amun, called in some of the inscriptions “the soul of Osiris,” derives his name from the root men, to impregnate, to beget. In the Karnak inscriptions he is also termed “the husband of his mother.” This, too, was the favorite appellation of Chem, who was a form of Horos. See Dr. C.P. Tiele, History of the Egyptian Religion, pp. 124, 146. 149, 150, etc.]

Let us look at the names in the myth before us, for confirmation of this. Ioskeha is in the Oneida dialect of the Iroquois an impersonal verbal form of the third person singular, and means literally, “it is about to grow white,” that is, to become light, to dawn. Ataensic is from the root aouen, water, and means literally, “she who is in the water.”.[1] Plainly expressed, the sense of the story is that the orb of light rises daily out of the boundless waters which are supposed to surround the land, preceded by the dawn, which fades away as soon as the sun has risen. Each day the sun disappears in these waters, to rise again from them the succeeding morning. As the approach of the sun causes the dawn, it was merely a gross way of stating this to say that the solar god was the father of his own mother, the husband of his grandmother.

[1: I have analyzed these words in a note to another work, and need not repeat the matter here, the less so, as I am not aware that the etymology has been questioned. See Myths of the New World, 2d Ed., p. 183, note.]

The position of Ioskeha in mythology is also shown by the other name under which he was, perhaps, even more familiar to most of the Iroquois. This is Tharonhiawakon, which is also a verbal form of the third person, with the dual sign, and literally means, “He holds (or holds up) the sky with his two arms.”.[1] In other words, he is nearly allied to the ancient Aryan Dyaus, the Sky, the Heavens, especially the Sky in the daytime.

[1: A careful analysis of this name is given by Father J.A. Cuoq, probably the best living authority on the Iroquois, in his Lexique de la Langue Iroquoise, p. 180 (Montreal, 1882). Here also the Iroquois followed precisely the line of thought of the ancient Egyptians. Shu, in the religion of Heliopolis, represented the cosmic light and warmth, the quickening, creative principle. It is he who, as it is stated in the inscriptions, “holds up the heavens,” and he is depicted on the monuments as a man with uplifted arms who supports the vault of heaven, because it is the intermediate light that separates the earth from the sky. Shu was also god of the winds; in a passage of the Book of the Dead, he is made to say: “I am Shu, who drives the winds onward to the confines of heaven, to the confines of the earth, even to the confines of space.” Again, like Ioskeha, Shu is said to have begotten himself in the womb of his mother, Nu or Nun, who was, like Ataensic, the goddess of water, the heavenly ocean, the primal sea. Tiele, History of the Egyptian Religion, pp. 84-86.]

The signification of the conflict with his twin brother is also clearly seen in the two names which the latter likewise bears in the legends. One of these is that which I have given, Tawiscara, which, there is little doubt, is allied to the root, tiokaras, it grows dark. The other is Tehotennhiaron, the root word of which is kannhia, the flint stone. This name he received because, in his battle with his brother, the drops of blood which fell from his wounds were changed into flints.[1] Here the flint had the same meaning which I have already pointed out in Algonkin myth, and we find, therefore, an absolute identity of mythological conception and symbolism between the two nations.

[1: Cuoq, Lexique de la Langue Iroquoise, p. 180, who gives a full analysis of the name.]

Could these myths have been historically identical? It is hard to disbelieve it. Yet the nations were bitter enemies. Their languages are totally unlike. These same similarities present themselves over such wide areas and between nations so remote and of such different culture, that the theory of a parallelism of development is after all the more credible explanation.

The impressions which natural occurrences make on minds of equal stages of culture are very much alike. The same thoughts are evoked, and the same expressions suggest themselves as appropriate to convey these thoughts in spoken language. This is often exhibited in the identity of expression between master-poets of the same generation, and between cotemporaneous thinkers in all branches of knowledge. Still more likely is it to occur in primitive and uncultivated conditions, where the most obvious forms of expression are at once adopted, and the resources of the mind are necessarily limited. This is a simple and reasonable explanation for the remarkable sameness which prevails in the mental products of the lower stages of civilization, and does away with the necessity of supposing a historic derivation one from the other or both from a common stock.

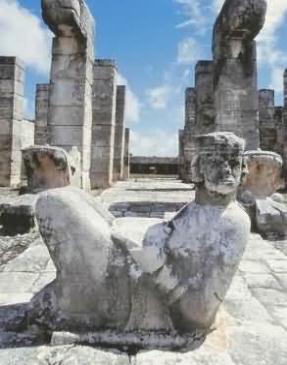

I now turn from the wild hunting tribes who peopled the shores of the Great Lakes and the fastnesses of the northern forests to that cultivated race whose capital city was in the Valley of Mexico, and whose scattered colonies were found on the shores of both oceans from the mouths of the Rio Grande and the Gila, south, almost to the Isthmus of Panama. They are familiarly known as Aztecs or Mexicans, and the language common to them all was the Nahuatl, a word of their own, meaning “the pleasant sounding.”

Their mythology has been preserved in greater fullness than that of any other American people, and for this reason I am enabled to set forth in ampler detail the elements of their hero-myth, which, indeed, may be taken as the most perfect type of those I have collected in this volume.

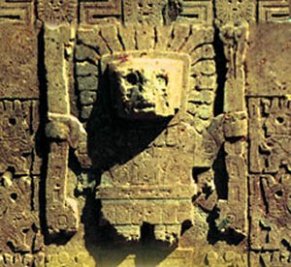

The culture hero of the Aztecs was Quetzalcoatl, and the leading drama, the central myth, in all the extensive and intricate theology of the Nahuatl speaking tribes was his long contest with Tezcatlipoca, “a contest,” observes an eminent Mexican antiquary, “which came to be the main element in the Nahuatl religion and the cause of its modifications, and which materially influenced the destinies of that race from its earliest epochs to the time of its destruction.”.( Alfredo Chavero, La Piedra del Sol, in the Anales del Museo Nacional de Mexico, Tom. II, p. 247.)

The explanations which have been offered of this struggle have varied with the theories of the writers propounding them. It has been regarded as a simple historical fact; as a figure of speech to represent the struggle for supremacy between two races; as an astronomical statement referring to the relative positions of the planet Venus and the Moon; as a conflict between Christianity, introduced by Saint Thomas, and the native heathenism; and as having other meanings not less unsatisfactory or absurd.

Placing it side by side with other American hero-myths, we shall see that it presents essentially the same traits, and undoubtedly must be explained in the same manner. All of them are the transparent stories of a simple people, to express in intelligible terms the daily struggle that is ever going on between Day and Night, between Light and Darkness, between Storm and Sunshine.

Like all the heroes of light, Quetzalcoatl is identified with the East. He is born there, and arrives from there, and hence Las Casas and others speak of him as from Yucatan, or as landing on the shores of the Mexican Gulf from some unknown land. His day of birth was that called Ce Acatl, One Reed, and by this name he is often known. But this sign is that of the East in Aztec symbolism.

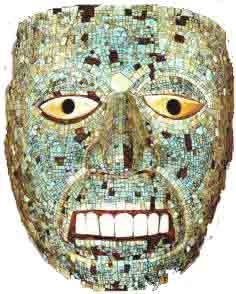

In a myth of the formation of the sun and moon, presented by Sahagun's Historia de las Cosas de Nueva Espana, Lib. VII, cap. II., a voluntary victim springs into the sacrificial fire that the gods have built. They know that he will rise as the sun, but they do not know in what part of the horizon that will be. Some look one way, some another, but Quetzalcoatl watches steadily the East, and is the first to see and welcome the Orb of Light. He is fair in complexion, with abundant hair and a full beard, bordering on the red,[3] as are all the dawn heroes, and like them he was an instructor in the arts, and favored peace and mild laws.