CHAPTER XXVII The Empire of Rameses and the Homeric Age

Sectarian Rivalries--Struggles for Political Ascendancy--New Theology--The Dragon Slayer--Links between Sutekh, Horus, Sigurd, Siegfried, Finn-mac-Coul, Dietrich, and Hercules--Rameses I and the Hittites--Break-up of Mitanni Empire--Seti's Conquests--Wars of Rameses II--Treaty with the Hittites--Pharaoh's Sublime Vanity--Sea Raids by Europeans on Egypt--The Last Strong Pharaoh--The Great Trojan War.

THE Nineteenth Dynasty opens with Rameses I, but no record survives to throw light on his origin, or the political movement which brought him to the throne. He was an elderly man, and does not appear to have been related to Horemheb. When he had reigned for about two years his son Seti was appointed co-regent.

But although history is silent regarding the intrigues of this period, its silence is eloquent. As the king's throne name indicates, he was attached to the cult of Ra, and it is of significance to note that among his other names there is no recognition of Amon.

The history of Egypt is the history of its religion. Its destinies were controlled by its religious cults and by the sects within the cults. Although Ra was fused with Amon, there are indications that rivalries existed not only between Heliopolis and Thebes, but also between the sects in Thebes, where several temples were dedicated to the national god. The theological system which evolved from the beliefs associated with Amon, the old as lunar deity, must have presented many points of difference to those which emanated from Heliopolis, the home of scholars and speculative thinkers. During the Eighteenth Dynasty the priesthood was divided into two great parties: one supported the claims of Queen Hatshepsut, while the other espoused the cause of Thothmes III. It may be that the queen was favoured by the Ra section of the Amon-ra cult, and that her rival was the chosen of the Amon section. The Thothmes III party retained its political ascendancy until Thothmes IV, who worshipped Ra Harmachis, was placed upon the throne, although not the crown prince. It is possible that the situation created by the feuds which appear to have been waged between the rival sects in the priesthood facilitated the religious revolt of Akhenaton, which, it may be inferred, could have been stamped out if the rival sects had presented a united front and made common cause against him.

With the accession of Rameses I we appear to be confronted with the political ascendancy of the Ra section. It is evident that the priests effected the change in the succession to the throne, for the erection was at once undertaken of the great colonnaded hall at Karnak, which was completed by Rameses II. The old Amon party must have been broken up, for the solar attributes of Amon-ra became more and more pronounced as time went on, while lunar worship was associated mainly with Khonsu and the imported moon goddesses of the type of Astarte and the "strange Aphrodite". To this political and religious revolution may be attributed the traditional prejudice against Thothmes III.

The new political party, as its "new theology" suggests, derived its support not only from Heliopolis, but also from half-foreign Tanis in the Delta. Influences from without were evidently at work. Once again, as in the latter half of the Twelfth Dynasty and in Hyksos times, the god Set or Sutekh came into prominence in Egypt. The son of Rameses I, Seti, was a worshipper of Set--not the old Egyptianized devil Set, but the Set who slew the Apep serpent, and was identified with Horus.

The Set of Rameses II, son of Seti I,1 wore a conical hat like a typical Hittite deity, arid from it was suspended a long rope or pigtail; he was also winged like the Horus sun disk. On a small plaque of glazed steatite this "wonderful deity" is depicted "piercing a serpent with a large spear". The serpent is evidently the storm demon of one of the Corycian caves in Asia Minor--the Typhon of the Greeks, which was slain by the deity identified now with Zeus and now with Hercules. The Greek writers who have dealt with Egyptian religion referred to "the roaring Set" as Typhon also. The god Sutekh of Tanis combined the attributes of the Hittite dragon slayer with those of Horus and Ra.

It is possible that to the fusion of Horus with the dragon slayer of Asia Minor may be traced the origin of Horus as Harpocrates (Her-pe-khred), the child god who touches his lips with an extended finger. The Greeks called him "the god of silence"; Egyptian literature throws no light on his original character. From what we know of Horus of the Osirian legends there is no reason why he should have considered. it necessary to preserve eternal silence.

In a particular type of the dragon-slaying stories of Europe,2 which may have gone north from Asia Minor with the worshippers of Tarku (Thor or Thunor), the hero--a humanized deity--places his finger in his mouth for a significant reason. After Siegfried killed the dragon he roasted its heart, and when he tasted it he immediately understood the language of birds. Sigurd, the Norse dragon slayer, is depicted with his thumb in his mouth after slaying Fafher.1 The Highland Finn, the slayer of Black Arky, discovered that he had a tooth of knowledge when he roasted a salmon, and similarly thrust his burnt finger into his mouth.2 In the Nineteenth-Dynasty fragmentary Egyptian folktale, "Setna and the Magic Book", which has been partially reconstructed by Professor Petrie,1 Ahura relates: "He gave the book into my hands; and when I read a page of the spells in it, I also enchanted heaven and earth, the mountains and the sea; I also knew what the birds of the sky, the fishes of the deep, and the beasts of the hill all said". The prototype of Ahura in this "wonder tale" may have been Horus as Harpocrates. Ahura, like Sigurd and Siegfried, slays a "dragon" ere he becomes acquainted with the language of birds; it is called "a deathless snake". "He went to the deathless snake, and fought with him, and killed him; but he came to life again, and took a new form. He then fought again with him a second time; but he came to life again, and took a third form. He then cut him in two parts, and put sand between the parts, that he should not appear again" (Petrie). Dietrich von Bern experienced a similar difficulty in slaying Hilde, the giantess, so as to rescue Hildebrand from her clutches,1 and Hercules was unable to put an end to the Hydra until Iolaus came to his assistance with a torch to prevent the growth of heads after decapitation.2 Hercules buried the last head in the ground, thus imitating Ahura, who "put sand between the parts" of the "deathless snake". All these versions of a well-developed tale appear to be offshoots of the great Cilician legend of "The War of the Gods". Attached to an insignificant hill cave at Cromarty, in the Scottish Highlands, is the story of the wonders of Typhon's cavern in Sheitandere (Devil's Glen), Western Cilicia. Whether it was imported from Greece, or taken north by the Alpine people, is a problem which does not concern us here.

At the close of the Eighteenth Dynasty the Hittites were pressing southward through Palestine and were even threatening the Egyptian frontier. Indeed, large numbers of their colonists appear to have effected settlement at Tanis, where Sutekh and Astarte had become prominent deities. Rameses I arranged a peace treaty3 with their king, Sapalul (Shubiluliuma), although he never fought a battle, which suggests that the two men were on friendly terms. The mother of Seti may have been a Hittite or Mitanni princess, the daughter or grandchild of one of the several Egyptian princesses who were given as brides to foreign rulers during the Eighteenth Dynasty. That the kings of the Nineteenth Dynasty were supported by the foreign element in Egypt is suggested by their close association with Tanis, which had become a city of great political importance and the chief residence of the Pharaohs. Thebes tended to become more and more an ecclesiastical capital only.

Seti I was a tall, handsome man of slim build with sharp features and a vigorous and intelligent face. His ostentatious piety had, no doubt, a political motive; all over Egypt his name appears on shrines, and he restored many monuments which suffered during Akhenaton's reign. At Abydos he built a great sanctuary to Osiris, which shows that the god Set whom he worshipped was not the enemy of the ancient deified king, and he had temples erected at Memphis and Heliopolis, while he carried on the work at the great Theban colonnaded hall. He called himself "the sun of Egypt and the moon of all other lands", an indication of the supremacy achieved by the sun cult.

Seti was a dashing and successful soldier. He conducted campaigns against the Libyans on the north and the Nubians in the south, but his notable military successes were achieved in Syria.

A new Hittite king had arisen who either knew not the Pharaoh or regarded him as too powerful a rival; at any rate, the peace was broken. The Hittite overlord was fomenting disturbances in North Syria, and probably also in Palestine, where the rival Semitic tribes were engaged in constant and exhausting conflicts. He had allied himself with the Aramæans, who were in possession of great tracts of Mesopotamia, and with invaders from Europe of Aryan speech in the north-west of Asia Minor.

The Hittite Empire had been broken up. In the height of its glory its kings had been overlords of Assyria. Tushratta's great-grandfather had sacked Ashur, and although Tushratta owed allegiance to Egypt he was able to send to Amenhotep III the Nineveh image of Ishtar, a sure indication of his supremacy over that famous city. When the Mitanni power was shattered, the Assyrians, Hittites, and Aramæans divided between them the lands held by Tushratta and his Aryan ancestors.

Shubiluliuma was king of the Hittites when Seti scattered hordes of desert robbers who threatened his frontier. He then pressed through war-vexed Palestine with all the vigour and success of Thothmes III. In the Orontes valley he met and defeated an army of Hittites, made a demonstration before Kadesh, and returned in triumph. to Egypt. Seti died in 1292, having reigned for over twenty years.

His son Rameses II, called "The Great" (by his own command), found it necessary to devote the first fifteen of the sixty-seven years of his reign to conducting strenuous military operations chiefly against the Hittites and their allies. A new situation had arisen in Syria, which was being colonized by the surplus population of Asia Minor. The Hittite army followed the Hittite settlers, so that it was no longer possible for the Egyptians to. effect a military occupation of the North Syrian territory, held by Thothmes III and his successors, without waging constant warfare against their powerful northern rival. Rameses II appears, however, to have considered himself strong enough to reconquer the lost sphere of influence for Egypt. As soon as his ambition was realized by Mutallu, the Hittite king, a great army of allies, including Aramæans and European raiders, was collected to await the ambitious Pharaoh.

Rameses had operated on the coast in his fourth year, and early in his fifth he advanced through Palestine to the valley of the Orontes. The Hittites and their allies were massed at Kadesh, but the Pharaoh, who trusted the story of two natives whom he captured, believed that they had retreated northward beyond Tunip. This seemed highly probable, because the Egyptian scouts were unable to get into touch with the enemy. But the overconfident Pharaoh was being led into a trap.

The Egyptian army was in four divisions, named Amon, Ra, Ptah, and Sutekh. Rameses was in haste to invest Kadesh, and pressed on with the Amon regiment, followed closely by the Ra regiment. The other two were, when he reached the city, at least a day's march in the rear.

Mutallu, the Hittite king, allowed Rameses to move round Kadesh on the western side with the Amon regiment and take up a position on the north. Meanwhile he sent round the eastern side of the city a force of 2500 charioteers, which fell upon the Ra regiment and cut through it, driving the greater part of it into the camp of Amon. Ere long Rameses found himself surrounded) with only a fragment of his army remaining, for the greater part of the Amon regiment had broken into flight with that of Ra and were scattered towards the north.

It was a desperate situation. But although Rameses was not a great general, he was a brave man, and fortune favoured him. Instead of pressing the attack from the west, the Hittites began to plunder the Egyptian camp. Their eastern wing was weak and was divided by the river from the infantry. Rameses led a strong force of charioteers, and drove this part of the Hittite army into the river. Meanwhile some reinforcements came up and fell upon the Asiatics in the Egyptian camp, slaying them almost to a man. Rameses was then able to collect some of his scattered forces, and he fought desperately against the western wing of the Hittite army until the Ptah regiment came up and drove the enemies of Egypt into the city.

Rameses had achieved a victory, but at a terrible cost. He returned to Egypt without accomplishing the capture of Kadesh, and created for himself a great military reputation by recording his feats of personal valour on temple walls and monuments. A poet who sang his praises declared that when the Pharaoh found himself surrounded, and, of course, "alone", he called upon Ra, whereupon the sun god appeared before him and said: "Alone thou art not, for I, thy father, am beside thee, and my hand is more to thee than hundreds of thousands. I who love the brave am the giver of victory." In one of his inscriptions the Pharaoh compared himself to Baal, god of battle.

Rameses delayed but he did not prevent the ultimate advance of the Hittites. In his subsequent campaigns he was less impetuous, but although he occasionally penetrated far northward, he secured no permanent hold over the territory which Thothmes III and Amenhotep "had won for Egypt. In the end he had to content himself with the overlordship of Palestine and part of Phœnicia. Mutalla, the Hittite king, had to deal with a revolt among his allies, especially the Aramæans, and was killed, and his brother Khattusil II,1 who succeeded him, entered into an offensive and defensive alliance with Rameses, probably against Assyria, which had grown powerful and aggressive. The treaty, which was drawn up in 1271 B.C., made reference to previous agreements, but these, unfortunately, have perished; it was signed by the two monarchs, and witnessed by a thousand Egyptian gods and a thousand Hittite gods.

Several years afterwards Khattusil visited Egypt to attend the celebration of the marriage of his daughter to Rameses. He was accompanied by a strong force and brought many gifts. By the great mass of the Egyptians he was regarded as a vassal of the Pharaoh; he is believed to be the prince referred to in the folktale which relates that the image of the god Khonsu was sent from Egypt to cure his afflicted daughter (see Chapter XV).

Rameses was a man of inordinate ambition and sublime vanity. He desired to be known to posterity as the greatest Pharaoh who ever sat upon the throne of Egypt. So he covered the land with his monuments and boastful inscriptions, appropriated the works of his predecessors, and even demolished temples to obtain building material. In Nubia, which had become thoroughly Egyptianized, he erected temples to Amon, Ras and Ptah. The greatest of these is the sublime rock temple at Abu Simbel, which he dedicated to Amon and himself. Beside it is a small temple to Hathor and his queen Nefertari, "whom he loves", as an inscription sets forth. Fronting the Amon temple four gigantic colossi were erected. One of Rameses remains complete; he sits, hands upon knees, gazing contentedly over the desert sands; that of his wife has suffered from falling debris, but survives in a wonderful state of preservation.

At Thebes the Pharaoh erected a large and beautiful temple of victory to Amon-ra, which is known as the Ramesseum, and he completed the great colonnaded hall at Karnak, the vastest structure of its kind the world has ever seen. On the walls of the Ramesseum is the well-known Kadesh battle scene, sculptured in low relief. Rameses is depicted like a giant bending his bow as he drives in his chariot, scattering before him into the River Orontes hordes of Lilliputian Hittites.

But although the name of' Rameses II dominates the Nile from Wady Halfa down to the Delta, we know now that there were greater Pharaohs than he, and, in fact, that he was a man of average ability. His mummy lies in the Cairo museum; he has a haughty aristocratic face and a high curved nose which suggests that he was partly of Hittite descent. He lived until he was nearly a century old. A worshipper of voluptuous Asiatic goddesses, he kept a crowded harem and boasted that he had a hundred sons and a large although uncertain number of daughters.

His successor was Seti Mene-ptah. Apparently Ptah, as well as Set, had risen into prominence, for Rameses had made his favourite son, who predeceased him, the high priest of Memphis. The new king was well up in years when he came to the throne in 1243 B.C. and hastened to establish his fame by despoiling existing temples as his father had done before him. During his reign of ten years Egypt was threatened by a new peril. Europe was in a state of unrest, and hordes of men from "the isles" were pouring into the Delta and allying themselves with the Libyans with purpose to effect conquests and permanent settlement in the land of the Pharaohs. About the same time the Phrygian occupation of the north-western part of Asia Minor was in progress. The Hittite Empire was doomed; it was soon to be broken up into petty states.

The Egyptian raiders appear to have been a confederacy of the old Cretan mariners, who had turned pirates, and the kinsfolk of the peoples who had over run the island kingdom. Included among them were the Shardana1 and Danauna (? the "Danaoi" of Homer) who were represented among the mercenaries of Pharaoh's army, the Akhaivasha, the Shakalsha, and the Tursha. It is believed that the Akhaivasha were the Achæans, the big, blonde, grey-eyed warriors identified with the "Keltoi" of the ancients, who according to the ethnologists were partly of Alpine and partly of Northern descent. It is possible that the Shakalsha were the people who gave their name to Sicily, and that they and the Tursha were kinsmen of the Lycians.

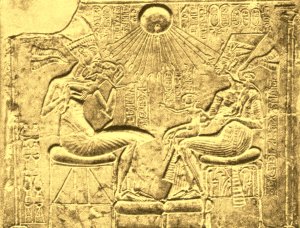

AKHENATON, HIS QUEEN, AND THEIR CHILDREN

(The upper panel shows Aton, the solar disk, sustaining and protecting royalty.

The rays terminate in hands, some of which hold the ankh symbols.)

From bas-reliefs in the Berlin Museum

Thothmes II |

Rameses II |

Rameses III |

Seti I |

|

|

|

Pharaoh Mene-ptah was thoroughly alarmed, for the invaders penetrated as far as Heliopolis. But the god Ptah appeared to him in a dream and promised victory. Supported by his Shardana and Danauna mercenaries, who had no scruples about attacking their kinsmen, he routed the army of allies, slaying about 9000 men and taking as many prisoners.

A stele at Thebes makes reference to a campaign waged by Mene-ptah in Palestine, where the peoples subdued included the children of Israel.

Although the son of the great Rameses II boasted that he had "united and pacified all lands", Egypt was plunged in anarchy after his death, which occurred in 1215 B.C. Three claimants to the throne followed in succession in ten years, and then a Syrian usurper became the Pharaoh. Once again the feudal lords asserted themselves, and Egypt suffered from famine and constant disorders.

The second king of the Twentieth Dynasty, Rameses III, was the last great Pharaoh of Egypt. In the eighth year of his reign a second strong sea raid occurred; it is dated between 1200 and 1190 B.C. On this occasion the invading allies were reinforced by tribes from Asia Minor and North Syria, which included the Tikkarai, the Muski (? Moschoi of the Greeks), and the Pulishta or Pilesti who were known among Solomon's guards as the Peleshtem. The Pulishta are identified as the Philistines from Crete who gave their name to Palestine, which they occupied along the seaboard from Carmel to Ashdod and as far inland as Beth-shan below the plain of Jezreel.

It is evident that the great raid was well organized and under the supreme command of an experienced leader. A land force moved down the coast of Palestine to co-operate with the fleet, and with it came the raiders' wives and children and their goods and chattels conveyed in wheel carts.1 Rameses III was prepared for the invasion. A land force guarded his Delta frontier and his fleet awaited the coming of the sea raiders. The first naval battle in history was fought within sight of the Egyptian coast, and the Pharaoh had the stirring spectacle sculptured in low relief on the north wall of his Amon-ra temple at Medinet Habu, on the western plain of Thebes. The Egyptian vessels were crowded with archers who poured deadly fusillades into the enemies' ships. An overwhelming victory was achieved by the Pharaoh; the sea power of the raiders was completely shattered.

Rameses then marched his army northwards through Palestine to meet the land raiders, whom he defeated somewhere in southern Phœnicia.

The great Trojan war began shortly after this great attack upon Egypt. According to the Greeks it was waged between 1194 and 1184 B.C. Homer's Troy, the sixth city of the archæologists, had been built by the Phrygians. Priam was their king, and he had two sons, Hector, the crown prince, and Paris. Menelaus had secured the throne of Sparta by marrying Helen, the royal heiress. When, as it chanced, he went from home--perhaps to command the sea raid upon Egypt--Paris carried off his queen and thus became, apparently, the claimant of the Spartan throne. On his return home Menelaus assembled an army of allies, set sail in a fleet of sixty ships, and besieged the city of Troy. This war of succession became the subject of Homer's great epic, the Iliad, which deals with a civilization of the "Chalkosideric" period--the interval between the Bronze and Iron Ages.1

Meanwhile Egypt had rest from its enemies. Rameses reigned for over thirty years. He had curbed the Libyans and the Nubians as well as the sea and land raiders, and held sway over a part of Palestine. But the great days of Egypt had come to an end. It was weakened by internal dissension, which was only held in check and not stamped out by an army of foreign mercenaries, including Libyans as well as Europeans. The national spirit flickered low among the half-foreign Egyptians of the ruling class. When Rameses III was laid in his tomb the decline of the power of the Pharaohs, which he had arrested for a time, proceeded apace. The destinies of Egypt were then shaped from without rather than from within.

Footnotes

340:1 Griffiths in Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archæology, Volume XVI, pp. 88-9.

340:2 One must distinguish between the various kinds of mythical monsters slumped as "dragons". The "fiery flying serpent" may resemble the "fire drake", but both p. 341 differ from the "cave dragon" which does not spout fire and the "beast" of Celtic story associated with rivers, lakes, and the sea. The latter is found in Japan and China, as well as in Scotland and Ireland. In "Beowulf", Grendel and his mother belong to the water "beast" order; the dragon which causes the hero's death is a "fire drake". Egypt has also its flood and fire monsters. Thor slew the Midgard serpent at the battle of the "Dusk of the Gods".

341:1 Teutonic Myth and Legend.

341:2 Finn and his Warrior Band. The salmon is associated with the water "dragon"; the "essence", or soul, of the demon was in the fish, as the "essence" of Osiris was in Amon. It would appear that the various forms of the monster had to be slain to complete its destruction. This conception is allied to the belief in transmigration of souls.

342:1 Teutonic Myth and Legend. In Swedish and Gaelic stories similar incidents occur.

342:2 Classic Myth and Legend. The colourless character of the Egyptian legend suggests that it was imported, like Sutekh; its significance evidently faded in the new geographical setting.

342:3 It is referred to in the subsequent treaty between Rameses II and the Hittite king.

346:1 Known to the Egyptians as Khetasar.

349:1 The old Cretans, the "Keftiu", are not referred to by the Egyptians after the reign of Amenhotep III. These newcomers were evidently the destroyers of the great palace at Knossos.

350:1 When the Philistines were advised by their priests to return the ark to the Israelites it was commanded: "Now, therefore make a new cart and take two milch kine and tie the kine to the cart".--(1 Samuel vi, 7).

351:1 The Cuchullin saga of Ireland belongs to the same archæological period; bronze and iron weapons were used. Cuchullin is the Celtic Achilles; to both heroes were attached the attributes of some old tribal god. The spot on the heel of Achilles is shared by the more primitive Diarmid of the Ossianic saga.

Next: Chapter XXVIII: Egypt and the Hebrew Monarchy