CHAPTER XVIII Myths and Lays of the Middle Kingdom

Foreign Brides--Succession by Male and Female Lines--New Religious Belief--Sebek the Crocodile God--Identified with Set and Sutekh--The Crocodile of the Sun--The Friend and Foe of the Dead--Sebek Kings--The Tame Crocodile--Usert, the Earth Goddess--Resemblance to Isis and Neith --Sutekh and Baal--Significance of Dashur Jewellery--The Great Sphinx--Literary Activity--Egyptian Folksongs--Dialogue of a Man with his Soul--"To be or not to be"--Sun Cult Doctrines--"The Lay of the Harper".

DURING the Twelfth Dynasty Babylon fell and Crete was invaded. Egypt alone among the older kingdoms successfully withstood the waves of aggression which were passing over the civilized world. It was not immune, however to foreign influence. A controlling power in Syria had evidently to be reckoned with, for raiding bands were constantly hovering on the frontier. It has been suggested that agreements were concluded, but no records of any survive. There are indications, however, that diplomatic marriages took place, and these may have been arranged for purposes of conciliation. At any rate foreign brides were entering the royal harem, and the exclusive traditions of Egypt were being set at defiance.

Senusert II had a favourite wife called Nefert, "the beautiful", who appears to have been a Hittite. Her son, Senusert III, and her grandson, Amenemhet III, have been referred to as "new types".1 Their faces, as is shown plainly in the statuary, have distinct non-Egyptian and non-Semitic characteristics; they are long and angular--the third Senusert's seems quite Mongoloid--with narrow eyes and high cheek bones. There can be no doubt about the foreign strain.

It is apparent that Senusert III ascended the throne as the son of his father. This fact is of special interest, because, during the Twelfth Dynasty, succession by the female line was generally recognized in Egypt. Evidently Senusert II elevated to the rank of Crown Prince the son of his foreign wife. Amenemhet III appears to have been similarly an arbitrary selection. No doubt the queens and dowager queens were making their presence felt, and were responsible for innovations of far-reaching character, which must have aroused considerable opposition. It may be that a legitimist party had become a disturbing element. The high rate of mortality in the royal house during the latter years of the Dynasty suggests the existence of a plot to remove undesirable heirs by methods not unfamiliar in Oriental Courts.

Along with the new royal faces new religious beliefs also came into prominence. The rise of Sebek, the crocodile god, may have been due to the tendency shown by certain of the Pharaohs to reside in the Fayum. The town of Crocodilopolis was the chief centre of the hitherto obscure Sebek cult. It is noteworthy, however, that the reptile deity was associated with the worship of Set-not the familiar Egyptian Set, but rather his prototype, Sutekh of the Hittites. Apparently an old tribal religion was revived in new and developed form.

In the texts of Unas, Sebek is referred to as the son of Neith, the Libyan "Earth Mother", who personified the female principle, and was believed to be self-sustaining, as she had been self-produced. She was "the unknown one" and "the hidden one", whose veil had never been uplifted. Like other virgin goddesses, she had a fatherless son, the "husband of his mother", who may have been identified with Sebek as a result of early tribal fusion.

It is suggested that in his crocodile form Sebek was worshipped as the snake was worshipped, on account of the dread he inspired. But, according to Diodorus, crocodiles were also regarded as protectors of Egypt, because, although they devoured the natives occasionally, they prevented robbers from swimming over the Nile. Opinions, however, differed as to the influence exercised by the crocodile on the destinies of Egypt. Some Indian tribes of the present day worship snakes, and do everything they can to protect even the most deadly specimens. In Egypt the crocodile was similarly protected in particular localities, while in others it was hunted down by sportsmen.1 We also find that in religious literature the reptile is now referred to as the friend and now as the enemy of the good Osiris. He brings ashore the dead body of the god to Isis in one legend,2 and in another he is identified with his murderers. In the "Winged Disk" story the followers of Set are crocodiles and hippopotami, and are slain by Horus because they are "the enemies of Ra". Yet Sebek was in the revolutionary Sixth Dynasty identified with the sun god, and in the Book of the Dead there is a symbolic reference to his dwelling on Sunrise Hill, where he was associated with Hathor and Horus--the Great Mother and son.

Sebek-Tum-Ra ultimately became the crocodile of the sun, as Mentu became "bull of the sun", and he symbolized the power and heat of the orb of day. In this form he was the "radiant green disk"-"the creator", who rose from Nu "in many shapes and in many colours".

At Ombos, Sebek was a form of Seb, the earth giant, the son of Nut, and "husband of his mother". He was called the "father of the gods" and "chief of the Nine Bow Barbarians".

In his Set form, Sebek was regarded in some parts as an enemy and devourer of the dead. But his worshippers believed that he would lead souls by "short cuts" and byways to the Egyptian paradise. In the Pyramid Texts he has the attributes of the elfin Khnûmû, whose dwarfish images were placed in tombs to prevent decay, for he renews the eyes of the dead, touches their tongues so that they can speak, and restores the power of motion to their heads.

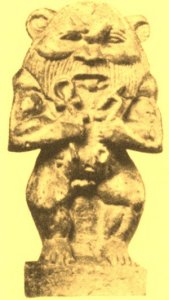

The recognition which Sebek received at Thebes may have been due to the influence of the late kings of the Twelfth Dynasty, and those of the Thirteenth who had Sebek names. The god is depicted as a man with a crocodile's head, and he sometimes wears Amon plumes with the sun disk; he is also shown simply as a crocodile. He was familiar to the Greeks as Sukhos. Strabo, who visited Egypt in the Roman period, relates that he saw a sacred crocodile in an artificial lake at Crocodilopolis in the Fayum. It was quite tame1 and was decorated with gold ear-rings, set with crystal, and wore bracelets on its fore paws. The priests opened its jaws and fed it with cakes, flesh, and honey wine. When the animal leapt into the water and came up at the other side, the priests followed it and gave it a fresh offering. Herodotus tells that the fore feet of the sacred crocodile which he saw were secured by a chain. It was fed not only with choice food, but with "the flesh of sacred victims". When the reptile died its body was embalmed, and, having been deposited in a sacred chest, was laid in one of the lower chambers of the Labyrinth. These subterranean cells were reputed to be of great sanctity, and Herodotus was not permitted to enter them.

The deity Usert, whose name is associated with the kings Senusert (also rendered Usertesen), was an earth goddess. She is identified with Isis, and closely resembles Neith-the Great Mother with a son whose human incarnation is the Pharaoh. Usert worship may have been closely associated, therefore, with Sebek worship, because Sebek was the son of an earth goddess. He rose from Nu, the primordial deep, as the crocodile rose from Lake Mœris, the waters of which nourished the "earth mother", and caused green verdure to spring up where formerly there was but sandy desert.1 Sebek was thus in a new sense a form of Ra, and a "radiant green sun disk". His association with Set was probably due to Asiatic influence, and the foreign strain in the royal house may have come from a district where Set was worshipped as Sutekh. The Egyptian Set developed from an early conception of a tribal Sutekh as a result of Asiatic settlement in the eastern Delta in pre-Dynastic times. The Hittite Sutekh was a sun god and a weather god. But there were many Sutekhs as there were many Baals. Baal signifies "lord" or "chief god", and in Egypt was identified with Set and with Mentu, the bull of war. At Tanis he was "lord of the heaven". Sutekh, also a "baal" or "lord", appears to have been similarly adaptable in tendency. If it was due to his influence that the crocodile god of the Fayum became a solar deity, the foreign ladies in the Pharaoh's harem must have been Hittites, whose religious beliefs influenced those of their royal sons.

COURTYARD OF AN EGYPTIAN TEMPLE (RESTORED)

Khnûmû (ram-headed) |

Sebek, Crocodile God |

Min |

Bes |

Anubis |

|

|

|

||

Exquisite jewellery has been found at Dashur, where Amenemhet II and his grandson Senusert III resided and erected their pyramids--two diadems of princesses of the royal house, the daughters of the second Senusert's foreign wife, at Dashur. One is a mass of little gold flowers connected by gold wires, which recall the reference, in Exodus, xxxlx, 3, to the artisans who "did beat the gold into thin plates, and cut it into wires". The design is strengthened by large "Maltese crosses" set with gems.1 Other pieces of Twelfth-Dynasty jewellery are similarly "innovations", and of the character which, long centuries afterwards, became known as Etruscan. But they could not have come from Europe at this period. They resemble the work for which the Hittites were famous.

The great sphinx may have also owed its origin to the influence exercised by the Hittites, whose emblem of power was a lion. Certain Egyptologists2 are quite convinced that it was sculptured during the reign of Amenemhet III, whose face they consider it resembles. Nilotic gods had animal heads with human bodies. The sphinx, therefore, could not have been a god of Egypt. Scarab beetle seals were also introduced during the Twelfth Dynasty. The Dynastic civilization of Egypt began with the use of the Babylonian seal cylinder.

The "Golden Age" is distinguished not only for its material progress, but also for its literary activity. In this respect it may be referred to as the "Elizabethan Age" of Ancient Egypt. The compositions appear to have been numerous, and many were of high quality. During the great Dynasty the kingdom was "a nest of singing birds", and the home of storytellers. There are snatches of song even in the tomb inscriptions, and rolls of papyri have been found in mummy coffins containing love ditties, philosophic poems, and wonder tales, which were provided for the entertainment of the dead in the next world.

It is exceedingly difficult for us to enter into the spirit of some of these compositions. We meet with baffling allusions to unfamiliar beliefs and customs, while our ignorance of the correct pronunciation of the language make some ditties seem absolutely nonsensical, although they may have been regarded as gems of wit; such quaint turns of phrase, puns, and odd mannerisms as are recognizable are entirely lost when attempts are made to translate them. The Egyptian poets liked to play upon words. In a Fifth-Dynasty tomb inscription this tendency is apparent. A shepherd drives his flock over the wet land to tramp down the seed, and he sings a humorous ditty to the sheep. We gather that he considers himself to be in a grotesque situation, for he "salutes the pike", and is like a shepherd among the dead, who converses with strange beings as he converses with fish. "Salutes" and "pike" are represented by the same word, and it is as if we said in English that a fisherman "flounders like flounders" or that joiners "box the box".

A translation is therefore exceedingly bald.

The shepherd is in the water with the fish;

He converses with the sheath fish;

He salutes the pike;

From the West--the shepherd is a shepherd from the West.

"The West" is, of course, the land of the dead.

Some of the Twelfth-Dynasty "minor poems" are, however, of universal interest because their meaning is as clear as their appeal is direct. The two which follow are close renderings of the originals.

THE WOODCARVER

The carver grows more weary

Than he who hoes all day,

As up and down his field of wood

His chisel ploughs away.

No rest takes he at even,

Because he lights a light;

He toils until his arms drop down

Exhausted, in the night.

THE SMITH

A smith is no ambassador--

His style is to abuse;

I never met a goldsmith yet

Able to give one news.

Oh, I have seen a smith at work,

Before his fire aglow--

His "claws" are like a crocodile;

He smells like fish's roe.

The Egyptian peasants were great talkers. Life was not worth living if there was nothing to gossip about. A man became exceedingly dejected when he had to work in solitude; he might even die from sheer ennui. So we can understand the ditty which tells that a brickmaker is puddling all alone in the clay at the time of inundation; he has to talk to the fish. "He is now a brickmaker in the West." In other words, the lonely task has been the death of him.

This horror of isolation from sympathetic companionship pervades the wonderful composition which has been called "The Dialogue of a Man with his Soul". The opening part of the papyrus is lost, and it is uncertain whether the lonely Egyptian was about to commit suicide or was contemplating with feelings of horror the melancholy fate which awaited him when he would be laid in the tomb. He appears to have suffered some great wrong; his brothers have deserted him, his friends have proved untrue, and--terrible fate!--he has nobody to speak to. Life is, therefore, not worth living, but he dreads to die because of the darkness and solitude of the tomb which awaits him. The fragment opens at the conclusion of a speech made by the soul. Apparently it has refused to accompany the man, so that he is faced with the prospect of not having even his soul to converse with.

"In the day of my sorrow", the man declares, "you should be my companion and my sympathetic friend. Why scold me because I am weary of life? Do not compel me to die, because I take no delight in the prospect of death; do not tell me that there is joy in the 'aftertime'. It is a sorrowful thing that this life cannot be lived over again, for in the next world the gods will consider with great severity the deeds we have done here."

He calls himself a "kindly and sympathetic man", but the soul thinks otherwise and is impatient with him. "You poor fool," it says, "you dread to die as if you were one of these rich men."

But the Egyptian continues to lament his fate; he has no belief in joy after death. The soul warns him, therefore, that if he broods over the future in such a spirit of despondency he will be punished by being left forever in his dark solitary tomb. The inference appears to be that those who lack faith will never enter Paradise.

"The thought of death", says the soul, "is sorrow in itself, it makes men weep; it makes them leave their homes and throw themselves in the dust."

Men who display their unbelief, never enjoy, after death, the light of the sun. Statues of granite may be carved for them, their friends may erect pyramids which display great skill of workmanship, but their fate is like that of "the miserable men who died of hunger at the riverside, or the peasant ruined by drought or by the flood--a poor beggar who has lost everything and has none to talk to except the fishes".

The soul counsels the man to enjoy life and to banish care and despondency. He is a foolish fellow who contemplates death with sorrow because he has grown weary of living; the one who has cause to grieve is he whose life is suddenly cut short by disaster. Such appears to be the conclusion which should be drawn from the soul's references to some everyday happenings of which the following is an example:--

"A peasant has gathered in his harvest; the sheaves are in his boat; he sails on the Nile, and his heart is filled with the prospect of making merry. Suddenly a storm comes on. He is compelled to remain beside his boat, guarding his harvest. But his wife and his children suffer a melancholy fate. They were coming to meet him, but they lost their way in the storm, and the crocodiles devoured them. The poor peasant has good cause to lament aloud. He cries out, saying:

"'I do not sorrow for my beloved wife, who has gone hence and will never return, so much as for the little children who, in the dawn of life, met the crocodile and perished.'"

The man is evidently much impressed by the soul's reasoning. He changes his mind, and praises the tomb as a safe retreat and resting place for one who, like himself, cannot any longer enjoy life. Why he feels so utterly dejected we cannot tell; the reason may have been given in the lost portion of the old papyrus. There is evidently no prospect of enjoyment before him. His name has become hateful among men; he has been wronged; the world is full of evil as he is full of sorrow.

At this point the composition becomes metrical in construction:

Hateful my name! . . . more hateful is it now

Than the rank smell of ravens in the heat;

Than rotting peaches, or the meadows high

Where geese are wont to feed; than fishermen

Who wade from stinking marshes with their fish,

Or the foul odour of the crocodile;

More hateful than a husband deems his spouse

When she is slandered, or his gallant son

Falsely accused; more hateful than a town

Which harbours rebels who are sought in vain.

Whom can I speak to? . . . Brothers turn away;

I have no friend to love me as of yore;

Hearts have turned cold and cruel; might is right;

The strong are spoilers, and the weakly fall,

Stricken and plundered. . . . Whom can I speak to?

The faithful man gets sorrow for reward--

His brother turns his foe--the good he does,

How swiftly 'tis undone, for thankless hearts

Have no remembrance of the day gone past.

Whom can I speak to? I am full of grief--

There is not left alive one faithful man;

The world is full of evil without end.

Death is before me like a draught prepared

To banish sickness; or as fresh, cool air

To one who, after fever, walks abroad.

Death is before me sweet as scented myrrh;

Like soft repose below a shelt'ring sail

In raging tempest. . . . Death before me is

Like perfumed lotus; like a restful couch

Spread in the Land of Plenty; or like home

For which the captive yearns, and warriors greet

When they return. . . . Ah! death before me is

Like to a fair blue heaven after storm--

A channel for a stream--an unknown land

The huntsman long has sought and finds at last.

He who goes Yonder rises like a god

That spurns the sinner; lo! his seat is sure

Within the sun bark, who hath offered up

Choice victims in the temples of the gods;

He who goes Yonder is a learnèd man,

Whom no one hinders when he calls to Ra.

The soul is now satisfied, because the man has professed his faith in the sun god. It promises, therefore, not to desert him. "Your body will lie in the earth," it says, "but I will keep you company when you are given rest. Let us remain beside one another."

It is possible that this composition was intended to make converts for the sun cult. The man appears to dread the judgment before Osiris, the King of the Dead, who reckons up the sins committed by men in this world. His soul approves of his faith in Ra, of giving offerings in the temples, and of becoming a "learned man"--one who has acquired knowledge of the magic formulæ which enables him to enter the sun bark. This soul appears to be the man's Conscience. It is difficult to grasp the Egyptian ideas regarding the soul which enters Paradise, the soul which hovers over the mummy, and the conscious life of the body in the tomb. These were as vague as they appear to have been varied.

One of the most popular Egyptian poems is called "The Lay of the Harper". It was chanted at the banquets given by wealthy men. "Ere the company rises," wrote Herodotus, "a small coffin which contains a perfect model of the human body is carried round, and is shown to each guest in rotation. He who bears it exclaims: 'Look at this figure. . . . After death you will be like it. Drink, therefore, and be merry.'" The "lay" in its earliest form was of great antiquity. Probably a real mummy was originally hauled through the banquet hall.

LAY OF THE HARPER

'Tis well with this good prince; his day is

done,

His happy fate fulfilled. . . . So one goes forth

While others, as in days of old, remain.

The old kings slumber in their pyramids,

Likewise the noble and the learned, but some

Who builded tombs have now no place of rest,

Although their deeds were great. . . .

Lo! I have heard The words Imhotep and Hordadaf spake--

Their maxims men repeat. . . . Where are their tombs?--

Long fallen . . . e'en their places are unknown,

And they are now as though they ne'er had been.

No soul comes back to tell us how he fares--

To soothe and comfort us ere we depart

Whither he went betimes. . . . But let our minds

Forget of this and dwell on better things. . . .

Revel in pleasure while your life endures

And deck your head with myrrh. Be richly clad

In white and perfumed linen; like the gods

Anointed be; and never weary grow

In eager quest of what your heart desires--

Do as it prompts you . . . until that sad day

Of lamentation comes, when hearts at rest

Hear not the cry of mourners at the tomb,

Which have no meaning to the silent dead.

Then celebrate this festal time, nor pause--

For no man takes his riches to the grave;

Yea, none returns again when he goes hence.

Footnotes

234:1 Newberry and Garstang, and Petrie.

236:1 Herodotus says: "Those who live near Thebes, and the Lake Mœris, hold the crocodile in religious veneration. . . . Those who live in or near Elephantine make the beasts an article of food."

236:2 This is of special interest, because Hittite gods appear upon the backs of animals.

237:1 The god was not feared. It had been propitiated and became the friend of man.

238:1 When the Nile rises it runs, for a period, green and foul, after running red with clay. The crocodile may have been associated with the green water also.

239:1 The Maltese cross is believed to be of Elamite origin. It is first met with in Babylon on seals of the Kassite period. It appears on the neolithic pottery of Susa.

239:2 Newberry and Garstang.

Next: Chapter XIX: The Island of Enchantment