Chapter 9 of Legends of the Middle Ages Narrated with Special Reference to Literature and Art By H.A. Guerber

THE SONS OF AYMON.

The different chansons de gestes relating to Aymon and the necromancer Malagigi (Malagis), probably arose from popular ballads commemorating the struggles of Charles the Bald and his feudatories. These ballads are of course as old as the events which they were intended to record, but the chansons de gestes based upon them, and entitled "Duolin de Mayence," "Aymon, Son of Duolin de Mayence," "Maugis," "Rinaldo de Trebizonde," "The Four Sons of Aymon," and "Mabrian," are of much later date, and were particularly admired during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

One of the most famous of Charlemagne's peers was doubtless the noble Aymon of Dordogne; and when the war against the Avars in Hungary had been successfully closed, owing to his bravery, his adherents besought the king to bestow upon this knight some reward. Charlemagne, whom many of these later chansons de gestes describe as mean and avaricious, refused to grant any reward, declaring that were he to add still further to his vassal's already extensive territories, Aymon would soon be come more powerful than his sovereign.

[Sidenote: War between Aymon and Charlemagne.] This unjust refusal displeased Lord Hug of Dordogne, who had pleaded for his kinsman, so that he ventured a retort, which so incensed the king that he slew him then and there. Aymon, learning of the death of Lord Hug, and aware of the failure of his last embassy, haughtily withdrew to his own estates, whence he now began to wage war against Charlemagne.

Instead of open battle, however, a sort of guerrilla warfare was carried on, in which, thanks to his marvelous steed Bayard, which his cousin Malagigi, the necromancer, had brought him from hell, Aymon always won the advantage. At the end of several years, however, Charlemagne collected a large host, and came to lay siege to the castle where Aymon had intrenched himself with all his adherents.

[Sidenote: Loss of the horse Bayard.] During that siege, Aymon awoke one morning to find that his beloved steed had vanished. Malagigi, hearing him bewail his loss, bade him be of good cheer, promising to restore Bayard ere long, although he would be obliged to go to Mount Vulcanus, the mouth of hell, to get him. Thus comforted, Aymon ceased to mourn, while Malagigi set to work to fulfill his promise. As a brisk wind was blowing from the castle towards the camp, he flung upon the breeze some powdered hellebore, which caused a violent sneezing throughout the army. Then, while his foes were wiping their streaming eyes, the necromancer, who had learned his black art in the famous school of Toledo, slipped through their ranks unseen, and journeyed on to Mount Vulcanus, where he encountered his Satanic Majesty.

His first act was to offer his services to Satan, who accepted them gladly, bidding him watch the steed Bayard, which he had stolen because he preferred riding a horse to sitting astride a storm cloud as usual. The necromancer artfully pretended great anxiety to serve his new master, but having discovered just where Bayard was to be found, he made use of a sedative powder to lull Satan to sleep. Then, hastening to the angry steed, Malagigi made him tractable by whispering his master's name in his ear; and, springing on his back, rode swiftly away.

Satan was awakened by the joyful whinny of the flying steed, and immediately mounted upon a storm cloud and started in pursuit, hurling a red-hot thunderbolt at Malagigi to check his advance. But the necromancer muttered a magic spell and held up his crucifix, and the bolt fell short; while the devil, losing his balance, fell to the earth, and thus lamed himself permanently.

[Sidenote: Bayard restored by Malagigi.] Count Aymon, in the mean while, had been obliged to flee from his besieged castle, mounted upon a sorry steed instead of his fleet-footed horse. When the enemy detected his flight, they set out in pursuit, tracking him by means of bloodhounds, and were about to overtake and slay him when Malagigi suddenly appeared with Bayard. To bound on the horse's back, draw his famous sword Flamberge, which had been made by the smith Wieland, and charge into the midst of his foes, was the work of a few seconds. The result was that most of Aymon's foes bit the dust, while he rode away unharmed, and gathering many followers, he proceeded to win back all the castles and fortresses he had lost.

Frightened by Aymon's successes, Charlemagne finally sent Roland, his nephew and favorite, bidding him offer a rich ransom to atone for the murder of Lord Hug, and instructing him to secure peace at any price. Aymon at first refused these overtures, but consented at last to cease the feud upon receipt of six times Lord Hug's weight in gold, and the hand of the king's sister, Aya, whom he had long loved.

These demands were granted, peace was concluded, and Aymon, having married Aya, led her to the castle of Pierlepont, where they dwelt most happily together, and became the parents of four brave sons, Renaud, Alard, Guiscard, and Richard. Inactivity, however, was not enjoyable to an inveterate fighter like Aymon, so he soon left home to journey into Spain, where the bitter enmity between the Christians and the Moors would afford him opportunity to fight to his heart's content.

Years now passed by, during which Aymon covered himself with glory; for, mounted on Bayard, he was the foremost in every battle, and always struck terror into the hearts of his foes by the mere flash of his blade Flamberge. Thus he fought until his sons attained manhood, and Aya had long thought him dead, when a messenger came to Pierlepont, telling them that Aymon lay ill in the Pyrenees, and wished to see his wife and his children once more.

In answer to these summons Aya hastened southward, and found her husband old and worn, yet not so changed that she could not recognize him. Aymon, sick as he was, rejoiced at the sight of his manly sons. He gave the three eldest the spoil he had won during those many years' warfare, and promised Renaud (Reinold) his horse and sword, if he could successfully mount and ride the former.

[Sidenote: Bayard won by Renaud.] Renaud, who was a skillful horseman, fancied the task very easy, and was somewhat surprised when his father's steed caught him by the garments with his teeth, and tumbled him into the manger. Undismayed by one failure, however, Renaud sprang boldly upon Bayard; and, in spite of all the horse's efforts, kept his seat so well that his father formally gave him the promised mount and sword.

When restored to health by the tender nursing of his loving wife, Aymon returned home with his family. Then, hearing that Charlemagne had returned from his coronation journey to Rome, and was about to celebrate the majority of his heir, Aymon went to court with his four sons.

During the tournament, held as usual on such festive occasions, Renaud unhorsed every opponent, and even defeated the prince. This roused the anger of Charlot, or Berthelot as he is called by some authorities, and made him vow revenge. He soon discovered that Renaud was particularly attached to his brother Alard, so he resolved first to harm the latter. Advised by the traitor Ganelon, Chariot challenged Alard to a game of chess, and insisted that the stakes should be the players' heads.

This proposal was very distasteful to Alard, for he knew that he would never dare lay any claim to the prince's head even if he won the game, and feared to lose his own if he failed to win. Compelled to accept the challenge, however, Alard began the game, and played so well that he won five times in succession. Then Charlot, angry at being so completely checkmated, suddenly seized the board and struck his antagonist such a cruel blow that the blood began to flow. Alard, curbing his wrath, simply withdrew; and it was only when Renaud questioned him very closely that he told how the quarrel had occurred.

Renaud was indignant at the insult offered his brother, and went to the emperor with his complaint. The umpires reluctantly testified that the prince had forfeited his head, so Renaud cut it off in the emperor's presence, and effected his escape with his father and brothers before any one could lay hands upon them. Closely pursued by the imperial troops, Aymon and his sons were soon brought to bay, and fought so bravely that they slew many of their assailants. At last, seeing that all their horses except the incomparable Bayard had been slain, Renaud bade his brothers mount behind him, and they dashed away. The aged Aymon had already fallen into the hands of the emperor's adviser, Turpin, who solemnly promised that no harm should befall him. But in spite of this oath, and of the remonstrances of all his peers, Charlemagne prepared to have Aymon publicly hanged, and consented to release him only upon condition that Aymon would promise to deliver his sons into the emperor's hands, were it ever in his power to do so.

The four young men, knowing their father safe, and unwilling to expose their mother to the unpleasant experiences of the siege which would have followed had they remained at Pierlepont, now journeyed southward, and entered the service of Saforet, King of the Moors. With him they won many victories; but, seeing at the end of three years that this monarch had no intention of giving them the promised reward, they slew him, and offered their swords to Iwo, Prince of Tarasconia.

[Sidenote: Fortress of Montauban.] Afraid of these warriors,

yet wishing to bind them to him by indissoluble ties, Iwo gave

Renaud his daughter Clarissa in marriage, and helped him build an

impregnable fortress at Montauban. This stronghold was scarcely

finished when Charlemagne came up with a great army to besiege

it; but at the end of a year of fruitless attempts, the emperor

reluctantly withdrew, leaving Montauban still in the hands of his

enemies.

[Sidenote: Fortress of Montauban.] Afraid of these warriors,

yet wishing to bind them to him by indissoluble ties, Iwo gave

Renaud his daughter Clarissa in marriage, and helped him build an

impregnable fortress at Montauban. This stronghold was scarcely

finished when Charlemagne came up with a great army to besiege

it; but at the end of a year of fruitless attempts, the emperor

reluctantly withdrew, leaving Montauban still in the hands of his

enemies.

Seven years had now elapsed since the four young men had seen their mother; and, anxious to embrace her once more, they went in pilgrims' robes to the castle of Pierlepont. Here the chamberlain recognized them and betrayed their presence to Aymon, who, compelled by his oath, prepared to bind his four sons fast and take them captive to his sovereign. The young men, however, defended themselves bravely, secured their father instead, and sent him in chains to Charlemagne. Unfortunately the monarch was much nearer Pierlepont at the time than the young men supposed. Hastening onward, he entered the castle before they had even become aware of his approach, and secured three of them. The fourth, Renaud, aided by his mother, escaped in pilgrim's garb, and returned to Montauban. Here he found Bayard, and without pausing to rest, he rode straight to Paris to deliver his brothers from the emperor's hands.

Overcome by fatigue after this hasty journey, Renaud dismounted shortly before reaching Paris, and fell asleep. When he awoke he found that his steed had vanished, and he reluctantly continued his journey on foot, begging his way. He was joined on the way by his cousin Malagigi, who also wore a pilgrim's garb, and who promised to aid Renaud, not only in freeing his brothers, but also in recovering Bayard.

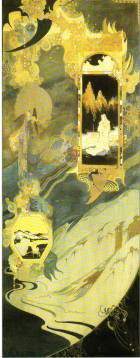

[Sidenote: Malagigi's stratagem.] Unnoticed, the beggars threaded their way through the city of Paris and came to the palace. There a great tournament was to be held, and the emperor had promised to the victor of the day the famous steed Bayard. To stimulate the knights to greater efforts by a view of the promised prize, the emperor bade a groom lead forth the renowned steed. The horse seemed restive, but suddenly paused beside two beggars, with a whinny of joy. The groom, little suspecting that the horse's real master was hidden under the travel-stained pilgrim's robe, laughingly commented upon Bayard's bad taste. Then Malagigi, the second beggar, suddenly cried aloud that his poor companion had been told that he would recover from his lameness were he only once allowed to bestride the famous steed. Anxious to witness a miracle, the emperor gave orders that the beggar should be placed upon Bayard; and Renaud, after feigning to fall off through awkwardness, suddenly sat firmly upon his saddle, and dashed away before any one could stop him.

As for Malagigi, having wandered among the throng unheeded, he remained in Paris until evening. Then, making his way into the prison by means of the necromantic charm "Abracadabra," which he continually repeated, he delivered the other sons of Aymon from their chains. He next entered the palace of the sleeping emperor, spoke to him in his sleep, and forced him, under hypnotic influence, to give up the scepter and crown, which he triumphantly bore away.

[Treachery of Iwo.] When Charlemagne awoke on the morrow, found his prisoners gone, and realized that what had seemed a dream was only too true, and that the insignia of royalty were gone, he was very angry indeed. More than ever before he now longed to secure the sons of Aymon; so he bribed Iwo, with whom the brothers had taken refuge, to send them to him. Clarissa suspected her father's treachery, and implored Renaud not to believe him; but the brave young hero, relying upon Iwo's promise, set out without arms to seek the emperor's pardon. On the way, however, the four sons of Aymon fell into an ambuscade, whence they would scarcely have escaped alive had not one of the brothers drawn from under his robe the weapons Clarissa had given him.

The emperor's warriors, afraid of the valor of these doughty brethren now that they were armed, soon withdrew to a safe distance, whence they could watch the young men and prevent their escape. Suddenly, however, Malagigi came dashing up on Bayard, for Clarissa had warned him of his kinsmen's danger, and implored him to go to their rescue. Renaud immediately mounted his favorite steed, and brandishing Flamberge, which his uncle had brought him, he charged so gallantly into the very midst of the imperial troops that he soon put them to flight.

[Sidenote: Renaud and Roland.] The emperor, baffled and angry, suspected that Iwo had warned his son-in-law of the danger and provided him with weapons. In his wrath he had Iwo seized, and sentenced him to be hanged. But Renaud, seeing Clarissa's tears, vowed that he would save his father-in-law from such an ignominious death. With his usual bravery he charged into the very midst of the executioners, and unhorsed the valiant champion, Roland. During this encounter, Iwo effected his escape, and Renaud followed him, while Roland slowly picked himself up and prepared to follow his antagonist and once more try his strength against him.

On the way to Montauban, Roland met Richard, one of the four brothers, whom he carried captive to Charlemagne. The emperor immediately ordered the young knight to be hanged, and bade some of his most noble followers to see the sentence executed. They one and all refused, however, declaring death on the gallows too ignominious a punishment for a knight.

The discussions which ensued delayed the execution and enabled Malagigi to warn Renaud of his brother's imminent peril. Mounted upon Bayard, Renaud rode straight to Montfaucon, accompanied by his two other brothers and a few faithful men. There they camped under the gallows, to be at hand when the guard came to hang the prisoner on the morrow. But Renaud and his companions slept so soundly that they would have been surprised had not the intelligent Bayard awakened his master by a very opportune kick. Springing to his feet, Renaud roused his companions, vaulted upon his steed, and charged the guard. He soon delivered his captive brother and carried him off in triumph, after hanging the knight who had volunteered to act as executioner.

[Sidenote: Montauban besieged by Charlemagne.] Charlemagne, still anxious to seize and punish these refractory subjects, now collected an army and began again to besiege the stronghold of Montauban. Occasional sallies and a few bloody encounters were the only variations in the monotony of a several-years' siege. But finally the provisions of the besieged became very scanty. Malagigi, who knew that a number of provision wagons were expected, advised Renaud to make a bold sally and carry them off, while he, the necromancer, dulled the senses of the imperial army by scattering one of his magic sleeping powders in the air. He had just begun his spell when Oliver perceived him and, pouncing upon him, carried him off to the emperor's tent. Oliver, on the way thither, never once relinquished his grasp, although the magician tried to make him do so by throwing a pinch of hellebore in his face.

While sneezing loudly the paladin told how he had caught the magician, and the emperor vowed that the rascal should be hanged on the very next day. When he heard this decree, Malagigi implored the emperor to give him a good meal, since this was to be his last night on earth, pledging his word not to leave the camp without the emperor. This promise so reassured Charlemagne that he ordered a sumptuous repast, charging a few knights to watch Malagigi, lest, after all, he should effect his escape. The meal over, the necromancer again had recourse to his magic art to plunge the whole camp into a deep sleep. Then, proceeding unmolested to the imperial tent, he bore off the sleeping emperor to the gates of Montauban, which flew open at his well-known voice.

Charlemagne, on awaking, was as surprised as dismayed to find himself in the hands of his foes, who, however, when they saw his uneasiness, gallantly gave him his freedom without exacting any pledge or ransom in return. But when Malagigi heard of this foolhardy act of generosity, he burned up his papers, boxes, and bags, and, when asked why he acted thus, replied that he was about to leave his mad young kinsmen to their own devices, and take refuge in a hermitage, where he intended to spend the remainder of his life in repenting of his sins. Soon after this he disappeared, and Aymon's sons, escaping secretly from Montauban just before it was forced to surrender, took refuge in a castle they owned in the Ardennes.

Here the emperor pursued them, and kept up the siege until Aya sought him, imploring him to forgive her sons and to cease persecuting them. Charlemagne yielded at last to her entreaties, and promised to grant the sons of Aymon full forgiveness provided the demoniacal steed Bayard were given over to him to be put to death. Aya hastened to Renaud to tell him this joyful news, but when he declared that nothing would ever induce him to give up his faithful steed, she besought him not to sacrifice his brothers, wife, and sons, out of love for his horse.

[Sidenote: Death of Bayard.] Thus adjured, Renaud, with breaking heart, finally consented. The treaty was signed, and Bayard, with feet heavily weighted, was led to the middle of a bridge over the Seine, where the emperor had decreed that he should be drowned. At a given signal from Charlemagne the noble horse was pushed into the water; but, in spite of the weights on his feet, he rose to the surface twice, casting an agonized glance upon his master, who had been forced to come and witness his death. Aya, seeing her son's grief, drew his head down upon her motherly bosom, and when Bayard rose once more and missed his beloved master's face among the crowd, he sank beneath the waves with a groan of despair, and never rose again.

Renaud, maddened by the needless cruelty of this act, now tore up the treaty and flung it at the emperor's feet. He then broke his sword Flamberge and cast it into the Seine, declaring that he would never wield such a weapon again, and returned to Montauban alone and on foot. There he bade his wife and children farewell, after committing them to the loyal protection of Roland. He then set out for the Holy Land, where he fought against the infidels, using a club as weapon, so as not to break his vow. This evidently proved no less effective in his hands than the noted Flamberge, for he was offered the crown of Jerusalem in reward for his services. As he had vowed to renounce all the pomps and vanities of the world, Renaud passed the crown on to Godfrey of Bouillon. Then, returning home, he found that Clarissa had died, after having been persecuted for years by the unwelcome attentions of many suitors, who would fain have persuaded her that her husband was dead.

[Sidenote: Death of Renaud.] According to one version of the story, Renaud died in a hermitage, in the odor of sanctity; but if we are to believe another, he journeyed on to Cologne, where the cathedral was being built, and labored at it night and day. Exasperated by his constant activity, which put them all to shame, his fellow-laborers slew him and flung his body into the Rhine. Strange to relate, however, his body was not carried away by the strong current, but lingered near the city, until it was brought to land and interred by some pious people.

Many miracles having taken place near the spot where he was buried, the emperor gave orders that his remains should be conveyed either to Aix-la-Chapelle or to Paris. The body was therefore laid upon a cart, which moved of its own accord to Dortmund, in Westphalia, where it stopped, and where a church was erected in honor of Renaud in 811. Here the saintly warrior's remains were duly laid to rest, and the church in Dortmund still bears his name. A chapel in Cologne is also dedicated to him, and is supposed to stand on the very spot where he was so treacherously slain after his long and brilliant career.