A New System; or, an Analysis of Ancient Mythology. Volume I

By Jacob Bryant

Of Worship Paid At Caverns And Of The Adoration Of Fire

As soon as religion began to lose its purity, it degenerated very fast; and, instead of a reverential awe and pleasing sense of duty, there succeeded a fearful gloom and unnatural horror, which were continually augmented as superstition increased. Men repaired in the first ages either to the lonely summits of mountains, or else to caverns in the rocks, and hollows in the bosom of the earth; which they thought were the residence of their Gods. At the entrance of these they raised their altars and performed their vows. Porphyry takes notice how much this mode of worship prevailed among the first nations upon the earth: [661]Σπηλαια τοινυν και αντρα των παλαιοτατων, πριν και ναους επινοησαι, θεοις αφοσιουντων και εν Κρητῃ μεν Κουρητων Διι, εν Αρκαδιᾳ δε Σεληνῃ, και Πανι εν Λυκειῳ και εν Ναξῳ Διονυσῳ. When in process of time they began to erect temples, they were still determined in their situation by the vicinity of these objects, which they comprehended within the limits of the sacred inclosure. These melancholy recesses were esteemed the places of the highest sanctity: and so greatly did this notion prevail, that, in aftertimes, when this practice had ceased, still the innermost part of the temple was denominated the cavern. Hence the Scholiast upon Lycophron interprets the words παρ' αντρα in the poet, [662]Τους εσωτατους τοπους του ναου. The cavern is the innermost place of the temple. Pausanias, speaking of a cavern in Phocis, says, that it was particularly sacred to Aphrodite. [663]Αφροδιτη δ' εχει εν σπηλαιῳ τιμας. In this cavern divine honours were paid to Aphrodite. Parnassus was rendered holy for nothing more than for these unpromising circumstances. Ἱεροπρεπης ὁ Παρνασσος, εχων αντρα τε και αλλα χωρια τιμωμενα τε, και, ἁγιστευομενα.[664] The mountain of Parnassus is a place of great reverence; having many caverns, and other detached spots, highly honoured and sanctified. At Tænarus was a temple with a fearful aperture, through which it was fabled that Hercules dragged to light the dog of hell. The cave itself seems to have been the temple; for it is said, [665]Επι τῃ ακρᾳ Ναος εικασμενος σπηλαιῳ. Upon the top of the promontory stands a temple, in appearance like a cavern. The situation of Delphi seems to have been determined on account of a mighty chasm in the hill, [666]οντος χασματος εν τῳ τοπῳ: and Apollo is said to have chosen it for an oracular shrine, on account of the effluvia which from thence proceeded.

[667]Ut vidit Pæan vastos telluris hiatus

Divinam spirare fidem, ventosque loquaces

Exhalare solum, sacris se condidit antris,

Incubuitque adyto: vates ibi factus Apollo.

Here also was the temple of the [668]Muses, which stood close upon a reeking stream. But, what rendered Delphi more remarkable, and more reverenced, was the Corycian cave, which lay between that hill and Parnassus. It went under ground a great way: and Pausanias, who made it his particular business to visit places of this nature, says, that it was the most extraordinary of any which he ever beheld. [669]Αντρον Κωρυκιον σπηλαιων, ὡν ειδον, θεας αξιον μαλιστα. There were many caves styled Corycian: one in Cilicia, mentioned by Stephanus Byzantinus from Parthenius, who speaks of a city of the same name: Παρ' ᾑ το Κωρυκιον αντρον Νυμφων, αξιαγαστον θεαμα. Near which city was the Corycian cavern, sacred to the nymphs, which afforded a sight the most astonishing. There was a place of this sort at [670]Samacon, in Elis; and, like the above, consecrated to the nymphs. There were likewise medicinal waters, from which people troubled with cutaneous and scrofulous disorders found great benefit. I have mentioned the temple at Hierapolis in [671]Phrygia; and the chasm within its precincts, out of which there issued a pestilential vapour. There was a city of the same name in [672]Syria, where stood a temple of the highest antiquity; and in this temple was a fissure, through which, according to the tradition of the natives, the waters at the deluge retired. Innumerable instances might be produced to this purpose from Pausanias, Strabo, Pliny, and other writers.

It has been observed, that the Greek term κοιλος, hollow, was often substituted for Coëlus, heaven: and, I think, it will appear to have been thus used from the subsequent history, wherein the worship of the Atlantians is described. The mythologists gave out, that Atlas supported heaven: one reason for this notion was, that upon mount Atlas stood a temple to Coëlus. It is mentioned by Maximus Tyrius in one of his dissertations, and is here, as in many other instances, changed to κοιλος, hollow. The temple was undoubtedly a cavern: but the name is to be understood in its original acceptation, as Coël, the house of God; to which the natives paid their adoration. This mode of worship among the Atlantian betrays a great antiquity; as the temple seems to have been merely a vast hollow in the side of the mountain; and to have had in it neither image, nor pillar, nor stone, nor any material object of adoration: [673]Εστι δε Ατλας ορος κοιλον, επιεικως ὑψηλον.—Τουτο Λιβυων και ἱερον, και θεος, και ὁρκος, και αγαλμα. This Atlas (of which I have been speaking) is a mountain with a cavity, and of a tolerable height, which the natives esteem both as a temple and a Deity: and it is the great object by which they swear; and to which they pay their devotions. The cave in the mountain was certainly named Co-el, the house of God; equivalent to Cœlus of the Romans. To this the people made their offerings: and this was the heaven which Atlas was supposed to support. It seems to have been no uncommon term among the Africans. There was a city in Libya named Coël, which the Romans rendered Coëlu. They would have expressed it Coelus, or Cœlus; but the name was copied in the time of the Punic wars, before the s final was admitted into their writings. Vaillant has given several specimens of coins struck in this city to the honour of some of the Roman [674]emperors, but especially of Verus, Commodus, and Antoninus Pius.

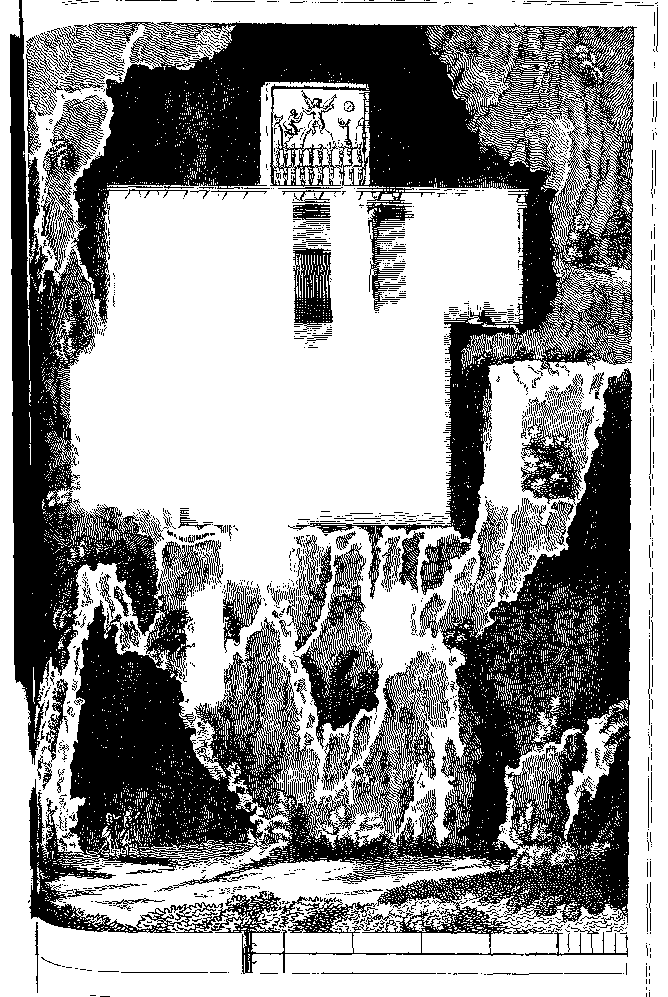

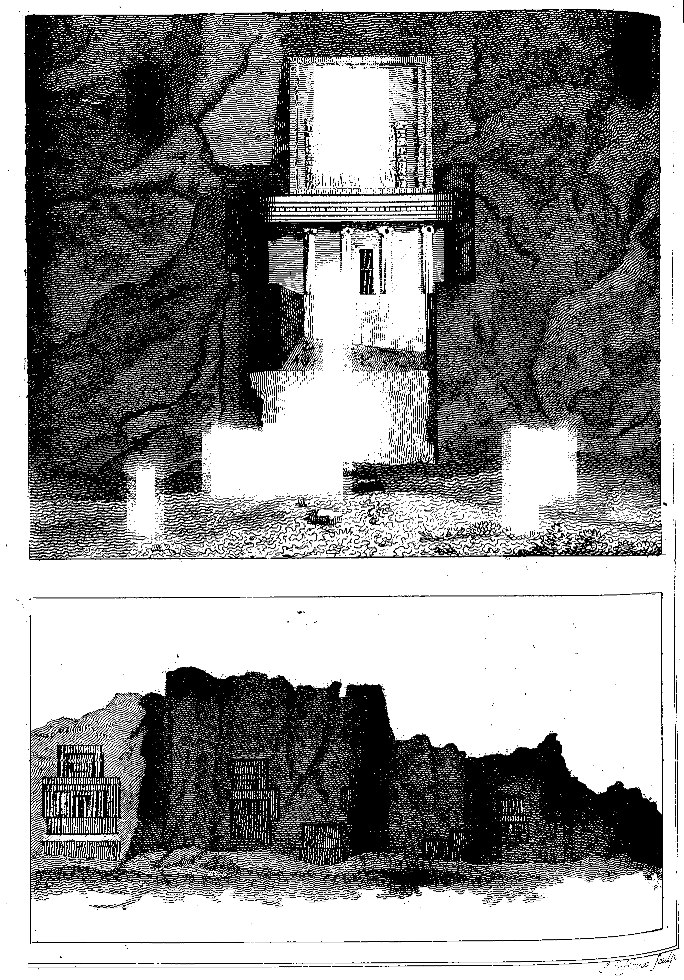

Pl. II. Temple of Mithras near Naki Rustan in Persia. Also temples in the rock near the Plain of the Magi. From Le Bruyn.

Among the Persians most of the temples were caverns in rocks, either formed by nature, or artificially produced. They had likewise Puratheia, or open temples, for the celebration of the rites of fire. I shall hereafter shew, that the religion, of which I have been treating, was derived from the sons of Chus: and in the antient province of Chusistan, called afterwards Persis, there are to be seen at this day many curious monuments of antiquity, which have a reference to that worship. The learned Hyde supposes them to have been either [675]palaces, or tombs. The chief building, which he has taken for a palace, is manifestly a Puratheion; one of those open edifices called by the Greeks Ὑπαιθρα. It is very like the temple at Lucorein in upper Egypt, and seems to be still entire. At a glance we may perceive, that it was never intended for an habitation. At a distance are some sacred grottos, hewn out of the rock; the same which he imagines to have been tombs. Many of the antients, as well as of the moderns, have been of the same opinion. In the front of these grottos are representations of various characters: and among others is figured, more than once, a princely personage, who is approaching the altar where the sacred fire is [676]burning. Above all is the Sun, and the figure of a Deity in a cloud, with sometimes a sacred bandage, at other times a serpent entwined round his middle, similar to the Cnuphis of Egypt. Hyde supposes the figure above to be the soul of the king, who stands before the altar: but it is certainly an emblem of the Deity, of which we have a second example in Le [677]Bruyn, copied from another part of these edifices. Hyde takes notice, that there were several repetitions of this history, and particularly of persons, solem et ignem in pariete delineatos intuentes: yet he forms his judgment from one specimen only. These curious samples of antient architecture are described by [678]Kæmpfer, [679]Mandesloe, [680]Chardin, and [681]Le Bruyn. They are likewise taken notice of by [682]Thevenot, and Herbert. In respect to the grottos I am persuaded, that they were temples, and not tombs. Nothing was more common among the Persians than to have their temples formed out of rocks. Mithras e [683]Petrâ was in a manner a proverb. Porphyry assures us, that the Deity had always a rock or cavern for his temple: that people, in all places, where the name of Mithras was known, paid their worship at a [684]cavern. Justin Martyr speaks to the same [685]purpose: and Lutatius Placidus mentions that this mode of worship began among the Persians, [686]Persæ in spelæis coli solem primi invenisse dicuntur. There is therefore no reason to think that these grottos were tombs; or that the Persians ever made use of such places for the sepulture of their kings. The tombs of [687]Cyrus, [688]Nitocris, and other oriental princes, were within the precincts of their cities: from whence, as well as from the devices upon the entablatures of these grottos, we may be assured that they were designed for temples. Le Bruyn indeed supposes them to have been places of burial; which is very natural for a person to imagine, who was not acquainted with the antient worship of the people. Thevenot also says, that he [689]went into the caverns, and saw several stone coffins. But this merely conjectural: for the things, to which he alludes, were not in the shape of coffins, and had undoubtedly been placed there as cisterns for water, which the Persians used in their nocturnal lustrations. This we may, in great measure, learn from his own words: for he says, that these reservoirs were square, and had a near resemblance to the basons of a fountain. The hills, where these grottos have been formed, are probably the same, which were of old famous for the strange echoes, and noises heard upon them. The circumstance is mentioned by Clemens Alexandrinus[690], who quotes it from the writers, who treated of the Persic history. It seems that there were some sacred hills in Persis, where, as people passed by, there were heard shouts, as of a multitude of people: also hymns and exultations, and other uncommon noises. These sounds undoubtedly proceeded from the priests at their midnight worship: whose voices at that season were reverberated by the mountains, and were accompanied with a reverential awe in those who heard them. The country below was called Χωρα των Μαγων, the region of the Magi.

The principal building also, which is thought to have been a palace, was a temple; but of a different sort. The travellers above say, that it is called Istachar: and Hyde repeats it, and tells us, that it signifies e rupe sumptum, seu rupe constans saxeum palatium: and that it is derived from the Arabic word sachr, rupes, in the eighth [691]conjugation. I am sorry, that I am obliged to controvert this learned man's opinion, and to encounter him upon his own ground, about a point of oriental etymology. I am entirely a stranger to the Persic, and Arabic languages; yet I cannot acquiesce in his opinion. I do not think that the words e rupe sumptum, vel rupe constans saxeum palatium, are at any rate materials, out of which a proper name could be constructed. The place to be sure, whether a palace, or a temple, is built of stone taken from the quarry, or rock: but what temple or palace is not? Can we believe that they would give as a proper name to one place, what was in a manner common to all; and choose for a characteristic what was so general and indeterminate? It is not to be supposed. Every symbol, and representation relates to the worship of the country: and all history shews that such places were sacred, and set apart for the adoration of fire, and the Deity of that element, called Ista, and Esta.[692] Ista-char, or Esta-char is the place or temple of Ista or Esta; who was the Hestia, Ἑστια, of the Greeks, and Vesta of the Romans. That the term originally related to fire we have the authority of Petavius. [693]Hebraïcâ linguâ אש ignem significat, Aramæâ אשתא quâ voce ignem a Noëmo vocatum Berosus prodidit: atque inde fortassis Græci Ἑστιας originem deduxerunt. Herbert, therefore, with great propriety, supposes the building to have been the temple of [694]Anaia, or Anaïs; who was the same as Hanes, as well as Hestia. Procopius, speaking of the sacred fire of the Persians, says expressly, that it was the very same which in aftertimes the Romans worshipped, and called the fire of Hestia, or Vesta. [695]Τουτο εστι το πυρ, ὁπερ Ἑστιαν εκαλουντο, και εσεβοντο εν τοις ὑστεροις χρονοις Ρωμαιοι. This is farther proved from a well known verse in Ovid.

[696]Nec tu aliud Vestam, quam vivam intellige flammam.

Hyde renders the term after Kæmpfer, Ista: but it was more commonly expressed Esta, and Asta. The Deity was also styled Astachan, which as a masculine signified Sol Dominus, sive Vulcanus Rex. This we may infer from a province in Parthia, remarkable for eruptions of fire, which was called [697]Asta-cana, rendered by the Romans Astacene, the region of the God of fire. The island Delos was famous for the worship of the sun: and we learn from Callimachus, that there were traditions of subterraneous fires bursting forth in many parts of it.

[698]Φυκος ἁπαν κατεφλεξας, επει περικαιεο πυρι.

Upon this account it was called [699]Pirpile; and by the same poet Histia, and Hestia, similar to the name above. [700]Ιστιη, ω νησων ευεστιη. The antient Scythæ were worshippers of fire: and Herodotus describes them as devoted to Histia[701]. Ἱλασκοντας Ἱστιην μεν μαλιστα. From hence, I think, we may know for certain the purport of the term Istachar, which was a name given to the grand Pureion in Chusistan from the Deity there worshipped. It stands near the bottom of the hills with the caverns in a widely-extended plain: which I make no doubt is the celebrated plain of the magi mentioned above by Clemens. We may from these data venture to correct a mistake in Maximus Tyrius, who in speaking of fire-worship among the Persians, says, that it was attended with acclamations, in which they invited the Deity to take his repast[702]. Πυρ, δεσποτα, εσθιε. What he renders εσθιε, was undoubtedly Ἑστιε, Hestie, the name of the God of fire. The address was, Ω Πυρ, δεσποτα, Ἑστιε: O mighty Lord of fire, Hestius: which is changed to O Fire, come, and feed.

The island Cyprus was of old called [703]Cerastis, and Cerastia; and had a city of the same name. This city was more known by the name of Amathus: and mention is made of cruel rites practised in its [704]temple. As long as the former name prevailed, the inhabitants were styled Cerastæ. They were more particularly the priests who were so denominated; and who were at last extirpated for their cruelty. The poets imagining that the term Cerastæ related to a horn, fabled that they were turned into bulls.

[705] Atque illos gemino quondam quibus aspera cornu

Frons erat, unde etiam nomen traxere Cerastæ.

There was a city of the same name in Eubœa, expressed Carystus, where the stone [706]Asbestus was found. Of this they made a kind of cloth, which was supposed to be proof against fire, and to be cleansed by that element. The purport of the name is plain; and the natural history of the place affords us a reason why it was imposed. For this we are obliged to Solinus, who calls the city with the Grecian termination, Carystos; and says, that it was noted for its hot streams: [707]Carystos aquas calentes habet, quas Ελλοπιας vocant. We may therefore be assured, that it was called Car-ystus from the Deity of fire, to whom all hot fountains were sacred. Ellopia is a compound of El Ope, Sol Python, another name of the same Deity. Carystus, Cerastis, Cerasta, are all of the same purport: they betoken a place, or temple of Astus, or Asta, the God of fire. Cerasta in the feminine is expressly the same, only reversed, as Astachar in Chusistan. Some places had the same term in the composition of their names, which was joined with Kur; and they were named in honour of the Sun, styled Κυρος, Curos. He was worshipped all over Syria; and one large province was hence named Curesta, and Curestica, from Κυρ Ἑστος, Sol Hestius.

In Cappadocia were many Puratheia; and the people followed the same manner of worship, as was practised in Persis. The rites which prevailed, may be inferred from the names of places, as well as from the history of the country. One city seems to have been denominated from its tutelary Deity, and called Castabala. This is a plain compound of Ca-Asta-Bala, the place or temple of Asta Bala; the same Deity, as by the Syrians was called Baaltis. Asta Bala was the Goddess of fire: and the same customs prevailed here as at Feronia in Latium. The female attendants in the temple used to walk with their feet bare over burning [708]coals.

Such is the nature of the temple named Istachar; and of the caverns in the mountains of Chusistan. They were sacred to Mithras, and were made use of for his rites. Some make a distinction between Mithras, Mithres, and Mithra: but they were all the same Deity, the [709]Sun, esteemed the chief God of the Persians. In these gloomy recesses people who were to be initiated, were confined for a long season in the dark, and totally secluded from all company. During this appointed term they underwent, as some say, eighty kinds of trials, or tortures, by way of expiation. [710]Mithra apud Persas Sol esse existimatur: nemo vero ejus sacris initiari potest, nisi per aliquot suppliciarum gradus transierit. Sunt tormentorum ij lxxx gradus, partim intensiores.—Ita demum, exhaustis omnibus tormentis, sacris imbuuntur. Many [711]died in the trial: and those who survived were often so crazed and shaken in their intellects, that they never returned to their former state of mind.

Some traces of this kind of penance may be still perceived in the east, where the followers of Mahomet have been found to adopt it. In the history given by Hanway of the Persian monarch, Mir Maghmud, we have an account of a process similar to that above, which this prince thought proper to undergo. He was of a sour and cruel disposition, and had been greatly dejected in his spirits; on which account he wanted to obtain some light and assistance from heaven. [712]With this intent Maghmud undertook to perform the spiritual exercises which the Indian Mahommedans, who are more addicted to them than those of other countries, have introduced into Kandahar. This superstitious practice is observed by shutting themselves up fourteen or fifteen days in a place where no light enters. The only nourishment they take is a little bread and water at sun-set. During this retreat they employ their time in repeating incessantly, with a strong guttural voice, the word Hou, by which they denote one of the attributes of the Deity. These continual cries, and the agitations of the body with which they were attended, naturally unhinge the whole frame. When by fasting and darkness the brain is distempered, they fancy they see spectres and hear voices. Thus they take pains to confirm the distemper which puts them upon such trials.

Such was the painful exercise which Maghmud undertook in January this year; and for this purpose he chose a subterraneous vault. In the beginning of the next month, when he came forth, he was so pale, disfigured, and emaciated, that they hardly knew him. But this was not the worst effect of his devotion. Solitude, often dangerous to a melancholy turn of thought, had, under the circumstances of his inquietude, and the strangeness of his penance, impaired his reason. He became restless and suspicious, often starting.—In one of these fits he determined to put to death the whole family of his predecessor, Sha Hussein; among whom were several brothers, three uncles, and seven nephews, besides that prince's children. All these, in number above an hundred, the tyrant cut to pieces with his own hand in the palace yard, where they were assembled for that bloody purpose. Two small children only escaped by the intervention of their father, who was wounded in endeavouring to screen them.

The reverence paid to caves and grottos arose from a notion that they were a representation of the [713]world; and that the chief Deity whom the Persians worshipped proceeded from a cave. Such was the tradition which they had received, and which contained in it matter of importance. Porphyry attributes the original of the custom to Zoroaster, whoever Zoroaster may have been; and says, that he first consecrated a natural cavern in Persis to Mithras, the creator and father of all things. He was followed in this practice by others, who dedicated to the Deity places of this [714]nature; either such as were originally hollowed by nature, or made so by the art of man. Those, of which we have specimens exhibited by the writers above, were probably enriched and ornamented by the Achaimenidæ of Persis, who succeeded to the throne of Cyrus. They are modern, if compared with the first introduction of the worship; yet of high antiquity in respect to us. They are noble relics of Persic architecture, and afford us matter of great curiosity.

Footnotes

[661] Porphyry de Antro Nympharum. p. 262. Edit. Cantab. 1655.

He speaks of Zoroaster: Αυτοφυες σπηλαιον εν τοις πλησιον ορεσι της Περσιδος ανθηρον, και πηγας εχον, ανιερωσαντος εις τιμην του παντων ποιητου, και πατρος Μιθρου. p. 254.

Clemens Alexandrinus mentions, Βαραθων στοματα τερατειας εμπλεα. Cohortatio ad Gentes.

Αντρα μεν δη δικαιως οι παλαιοι, και σπηλαια, τῳ κοσμῳ καθιερουν. Porphyry de Antro Nymph. p. 252. There was oftentimes an olive-tree planted near these caverns, as in the Acropolis at Athens, and in Ithaca.

Αυταρ επι κρατος λιμενος τανυφυλλος Ελαια,

Αγχοθι δ' αυτης Αντρον.

Homer de Antro Ithacensi. Odyss. l. ε. v. 346.

[662] Lycophron. v. 208. Scholia.

[663] Pausanias. l. x. p. 898. I imagine that the word caverna, a cavern, was denominated originally Ca-Ouran, Domus Cœlestis, vel Domus Dei, from the supposed sanctity of such places.

[664] Strabo. l. 9. p. 638.

Ενθα παρθενου

Στυγνον Σιβυλλης εστιν οικητηριον

Γρωνῳ Βερεθρῳ συγκατηρεφες στεγης.

Lycophron of the Sibyl's cavern, near the promontory Zosterion. v. 1278.

[665] Pausanias. l. 3. p. 5. 275.

[666] Scholia upon Aristophanes: Plutus. v. 9. and Euripides in the Orestes. v. 164.

[667] Lucan. l. 5. v. 82.

[668] Μουσων γαρ ην Ἱερον ενταυθα περι την αναπνοην του ναματος. Plutarch de Pyth. Oracul. vol. 1. p. 402.

[669] Pausanias. l. 10. p. 877.

[670] Pausanias. l. 5. p. 387. Sama Con, Cœli vel Cœlestis Dominus.

[671] Strabo. l. 12. p. 869. l. 13. p. 934. Demeter and Kora were worshipped at the Charonian cavern mentioned by Strabo: Χαρωνιον αντρον θαυμαστον τη φυσει. l. 14. p. 961.

[672] Lucian de Deâ Syriâ.

[673] Maximus Tyrius. Dissert. 8. p. 87.

[674] Vaillant: Numism. Ærea Imperator. Pars prima. p. 243, 245, 285. and elsewhere.

[675] Hyde. Religio Veterum Persarum. c. 23. p. 306, 7, 8.

[676] See PLATE ii. iii.

[677] Le Bruyn. Plate 153.

See the subsequent plate with the characters of Cneuphis.

[678] Kæmpfer. Amœnitates Exoticæ. p. 325.

[679] Mandesloe. p. 3. He mentions the sacred fire and a serpent.

[680] Sir John Chardin. Herbert also describes these caverns, and a serpent, and wings; which was the same emblem as the Cneuphis of Egypt.

[681] Le Bruyn's Travels, vol. 2. p. 20. See plate 117, 118, 119, 120. Also p. 158, 159, 166, 167.

[682] Thevenot. part 2d. p. 144, 146.

[683] Ὁι τα του Μιθρου μυστηρια παραδιδοντες λεγουσιν εκ πετρας γεγενησθαι αυτον, και σπηλαιον καλουσι τον τοπον. Cum Tyrphone Dialog. p. 168.

[684] He speaks of people—Πανταχου, ὁπου τον Μιθραν εγνωσαν, δια σπηλαιου ἱλεουμενων. Porphyry de Antro Nympharum. p. 263.

[685] Justin Martyr supra.

[686] Scholia upon Statius. Thebaid. l. 1. v. 720.

Seu Persei de rupibus Antri

Indignata sequi torquentem cornua Mithran.

[687] Plutarch: Alexander. p. 703. and Arrian. l. vi. p. 273.

[688] Herodotus. l. 1. c. 187.

[689] Thevenot. part 2d. p. 141, 146.

Some say that Thevenot was never out of Europe: consequently the travels which go under his name were the work of another person: for they have many curious circumstances, which could not be mere fiction.

[690] Clemens Alexandrinus. l. 6. p. 756.

[691] Hyde de Religione Vet. Persar. p. 306.

[692] See Radicals. p. 77.

[693] Petavius in Epiphanium. p. 42.

[694] Herbert's Travels. p. 138.

[695] Procopius. Persica. l. 1. c. 24.

[696] Ovid. Fast. l. 6. v. 291.

[697] Similis est natura Naphthæ, et ita adpellatur circa Babylonem, et in Astacenis Parthiæ, pro bituminis liquidi modo. Pliny. l. 2. c. 106. p. 123.

[698] Callim. H. to Delos. v. 201.

[699] Pliny. l. 2. c. 22. p. 112. He supposes the name to have been given, igne ibi primum reperto.

[700] Callimachus. H. to Delos. v. 325.

[701] Herodotus. l. iv. c. 69.

[702] Και θυουσι Περσαι πυρι, επιφορουντες αυτῳ την πυρος τροφην, επιλεγοντες, Πυρ, Δεσποτα, εσθιε. Maximus Tyrius. Dissert. 8. p. 83.

[703] See Lycophron. v. 447. and Stephanus. Κυπρος.

Κεραστιδος εις χθονα Κυπρου. Nonni Dionys. l. iv.

[704] Hospes erat cæsus. Ovid. Metamorph. l. x. v. 228.

[705] Ovid. Metamorph. l. x. v. 228.

[706] Strabo. l. 10. p. 684.

[707] Solinus. cap. 17. Pliny takes notice of the city Carystus. Eubœa—Urbibus clara quondam Pyrrhâ, Orco, Geræsto, Carysto, Oritano, &c. aquisque callidis, quæ Ellopiæ vocantur, nobilis. l. 4, c. 12.

[708] Εν τοις Κασταβαλοις εστι το της Περασιας Αρτεμιδος ἱερον, ὁπου φασι τας ἱερειας γυμνοις τοις ποσι δι' ανθρακιαν βαδιζειν απαθεις. Strabo. l. 12 p. 811.

[709] Μιθρας ὁ ἡλιος παρα Περσαις. Hesych.

Μιθρης ὁ πρωτος εν Περσαις Θεος. Ibidem.

Mithra was the same. Elias Cretensis in Gregorij Theologi Opera.

[710] Elias Cretensis. Ibidem. In like manner Nonnus says, that there could be no initiation—Αχρις ὁυ τας ογδοηκοντα κολασεις παρελθοι. In Nazianzeni Steliteutic. 2.

[711] Και τοτε λοιπον εμυουσι αυτον τα τελεωτερα, εαν ζησῃ. Nonnus supra.

[712] Account of Persia, by Jonas Hanway, Esq. vol. 3. c. 31, 32. p. 206.

[713] Εικονα φεροντος σπηλαιου του Κοσμου. Por. de Ant. Nymph. p. 254.

[714] Μετα δε τουτον τον Ζωροαστρην κρατησαντος και παρ' αλλοις δι' αντρων και σπηλαιων, ειτ' ουν αυτοφυων, ειτε χειροποιητων, τας τελετας αποδιδοναι. Porph. de Antro Nymph. p. 108. The purport of the history of Mithras, and of the cave from whence he proceeded, I shall hereafter shew. Jupiter was nursed in a cave; and Proserpine, Κορη Κοσμου, nursed in a cave: ὡσαυτως και ἡ Δημητηρ εν αντρῳ τρεφει την Κορην μετα Νυμφων· και αλλα τοιαυτα πολλα ἑυρησει τις επιων τα των θεολογων. Porph. ibid. p. 254.

Index | Next: Of The Omphi And Of The Worship Upon High Places