A New System; or, an Analysis of Ancient Mythology. Volume I

By Jacob Bryant

Of Ancient Worship, Etymological Truths Thence Deducible, Exemplified In The Names Of Cities, Lakes and Rivers

Εστι που και ποταμοις τιμη, η κατ' ωφελειαν, ὡσπερ Αιγυπτιοις προς τον Νειλον, η κατα καλλος, ὡς Θετταλοις προς Πηνειον, η κατα μεγεθος, ὡς Σκυθαις προς τον Ιστρον, η κατα μυθον, ὡς Αιτωλοις προς τον Αχελωον.—— Max. Tyrius. Dissert. viii. p. 81.

As the divine honours paid to the Sun, and the adoration of fire, were at one time almost universal, there will be found in most places a similitude in the terms of worship. And though this mode of idolatry took its rise in one particular part of the world, yet, as it was propagated to others far remote, the stream, however widely diffused, will still savour of the fountain. Moreover, as people were determined in the choice of their holy places by those preternatural phænomena, of which I have before taken notice; if there be any truth in my system, there will be uniformly found some analogy between the name of the temple, and its rites and situation: so that the etymology may be ascertained by the history of the place. The like will appear in respect to rivers and mountains; especially to those which were esteemed at all sacred, and which were denominated from the Sun and fire. I therefore flatter myself that the etymologies which I shall lay before the reader will not stand single and unsupported; but there will be an apparent analogy throughout the whole. The allusion will not be casual and remote, nor be obtained by undue inflexions and distortions: but, however complicated the name may appear, it will resolve itself easily into the original terms; and, when resolved, the truth of the etymology will be ascertained by the concomitant history. If it be a Deity, or other personage, the truth will appear from his office and department; or with the attributes imputed to him. To begin, then, with antient Latium. If I should have occasion to speak of the Goddess Feronia, and of the city denominated from her, I should deduce the from Fer-On, ignis Dei Solis; and suppose the place to have been addicted to the worship of the Sun, and the rites of fire. I accordingly find, from Strabo and Pliny, that rites of this sort were practised here: and one custom, which remained even to the time of Augustus, consisted in a ceremony of the priests, who used to walk barefoot over burning coals: [569]Γυμνοις γαρ ποσι διεξιασιν ανθρακιαν, και σποδιαν μεγαλην. The priests, with their feet naked, walked over a large quantity of live coals and cinders. The town stood at the bottom of Mount Soracte, sacred to Apollo; and the priests were styled Hirpi. Aruns, in Virgil, in his address to Apollo, takes notice of this custom:

[570]Summe Deûm, magni custos Soractis, Apollo,

Quem primi colimus; cui pineus ardor acervo

Pascitur, et medium freti pietate per ignem

Cultores multâ premimus vestigia prunâ;

Da, Pater.

The temple is said to have been founded on account of a pestilential [571]vapour, which arose from a cavern; and to which some shepherds were conducted by (Λυκος) a wolf. Were I to attempt the decyphering of Ferentum, I should proceed in a manner analogous to that above. I should suppose it to have been named Fer-En, ignis, vel Solis fons, from something peculiar either in its rites or situation. I accordingly find, that there was a sacred fountain, whose waters were styled Aquæ Ferentinæ,—cui numen etiam, et divinus cultus tributus [572]fuit. Here was a grove, equally sacred, mentioned by [573] Livy, and others; where the antient Latines used to hold their chief assemblies. As this grand meeting used to be in a place denominated from fire, it was the cause of those councils being called Feriæ Latinæ. The fountain, which ran through the grove, arose at the foot of mount [574]Albanus, and afterwards formed many [575]pools.

The antient Cuthites, and the Persians after them, had a great veneration for fountains and streams; which also prevailed among other nations, so as to have been at one time almost universal. Of this regard among the Persians Herodotus takes notice: [576]Σεβονται ποταμους των παντων μαλιστα: Of all things in nature they reverence rivers most. But if these rivers were attended with any nitrous or saline quality, or with any fiery eruption, they were adjudged to be still more sacred, and ever distinguished with some title of the Deity. The natives of Egypt had the like veneration. Other nations, says [577]Athanasius, reverenced rivers and fountains; but, above all people in the world, the Egyptians held them in the highest honour, and esteemed them as divine. Julius Firmicus gives the same account of them. [578]Ægyptii aquæ beneficium percipientes aquam colunt, aquis supplicant. From hence the custom passed westward to Greece, Italy, and the extremities of Europe. In proof of which the following inscription is to be found in Gruter:

[579]Vascaniæ in

Hispaniâ

FONTI DIVINO.

How much it prevailed among the Romans we learn from Seneca. [580]Magnorum fluviorum capita veneramur—coluntur aquarum calentium fontes; et quædam stagna, quæ vel opacitas, vel immensa altitudo sacravit. It mattered not what the nature of the water might be, if it had a peculiar quality. At Thebes, in Ammonia, was a fountain, which was said to have been cold by day, and warm at night. Ἡ κρηνη [581]καλειται του ἡλιου. It was named the fountain of the Sun. In Campania was a fountain Virena; which I should judge to be a compound of Vir-En, and to signify ignis fons, from being dedicated to the Deity of fire, on account of some particular quality. I accordingly find in [582]Vitruvius, that it was a medicinal spring, and of a strong vitriolic nature. The Corinthians had in their Acropolis a [583]Pirene, of the same purport as Virena, just mentioned. It was a beautiful fountain sacred to Apollo, whose [584]image was at the head of the water within a sacred inclosure.

We read of a Pyrene, which was a fountain of another nature; yet of the same etymology, however differently expressed. It was a mountain, and gave name to the vast ridge called Saltus Pyrenæi. It is undoubtedly a compound of [585]Pur-ain, and signifies a fountain of fire. I should imagine, without knowing the history of the country, that this mountain once flamed; and that the name was given from this circumstance. Agreeably to this, I find, from Aristotle de Mirabilibus, that here was formerly an eruption of fire. The same is mentioned by Posidonius in Strabo; and also by Diodorus, who adds, [586]Τα μεν ορη δια το συμβεβηκος κληθηναι Πυρηναια. That the mountains from hence had the name of Pyrenæi. Mount Ætna is derived very truly by Bochart from Aituna, fornax; as being a reservoir of molten matter. There was another very antient name, Inessus; by which the natives called the hill, as well as the city, which was towards the bottom of it. The name is a compound of Ain-Es, like Hanes in Egypt; and signifies a fountain of fire. It is called Ennesia by Diodorus, who says that this name was afterwards changed to Ætna. He speaks of the city; but the name was undoubtedly borrowed from the mountain, to which it was primarily applicable, and upon which it was originally conferred: [587]Και την νυν ουσαν Αιτνην εκτησαντο, προ τουτου καλουμενην Εννησιαν. Strabo expresses the name Innesa, and informs us, more precisely, that the upper part of the mountain was so called, Οι δε [588]Αιτναιοι παραχωρησαντες την Ιννησαν καλουμενην, της Αιτνης ορεινην, ᾡκησαν. Upon this, the people, withdrawing themselves, went and occupied the upper part of Mount Ætna, which was called Innesa. The city Hanes, in Egypt, was of the same etymology; being denominated from the Sun, who was styled Hanes. Ain-Es, fons ignis sive lucis. It was the same as the Arab Heliopolis, called now Mataiea. Stephanas Byzantinus calls the city Inys: for that is manifestly the name he gives it, if we take away the Greek termination, [589]Ινυσσος, πολις Αιγυπτου: but Herodotus, [590]from whom he borrows, renders it Iënis. It would have been more truly rendered Doricè Iänis; for that was nearer to the real name. The historian, however, points it out plainly, by saying, that it was three days journey from Mount [591]Casius; and that the whole way was through the Arabian desert. This is a situation which agrees with no other city in all Egypt, except that which was the Onium of the later Jews. With this it accords precisely. There seem to have been two cities named On, from the worship of the Sun. One was called Zan, Zon, and Zoan, in the land of Go-zan, the [592]Goshen of the scriptures. The other was the city On in Arabia; called also Hanes. They were within eight or nine miles of each other, and are both mentioned together by the prophet [593]Isaiah. For his princes were at Zoan, and his ambassadors came to Hanes. The name of each of these cities, on account of the similarity of worship, has by the Greeks been translated [594]Heliopolis; which has caused great confusion in the history of Egypt. The latter of the two was the Iänis, or Ιανισος, of the Greeks; so called from Hanes, the great fountain of light, the Sun; who was worshipped under that title by the Egyptians and Arabians. It lies now quite in ruins, close to the village Matarea, which has risen from it. The situation is so pointed out, that we cannot be mistaken: and we find, moreover, which is a circumstance very remarkable, that it is at this day called by the Arabians Ain El Sham, the fountain of the Sun; a name precisely of the same purport as Hanes. Of this we are informed by the learned geographer, D'Anville, and others; though the name, by different travellers, is expressed with some variation. [595]Cette ville presque ensévelie sous des ruines, et voisine, dit Abulfeda, d'un petit lieu nommé Matarea, conserve dans les géographies Arabes le nom d'Ainsiems ou du fontain du Soleil. A like account is given by Egmont and [596]Hayman; though they express the name Ain El Cham; a variation of little consequence. The reason why the antient name has been laid aside, by those who reside there, is undoubtedly this. Bochart tells us, that, since the religion of Mahomet has taken place, the Arabs look upon Hanes as the devil: [597]proinde ab ipsis ipse Dæmon הנאס vocatur. Hence they have abolished Hanes: but the name Ain El Cham, of the same purport, they have suffered to remain.

I have before taken notice of an objection liable to be made from a supposition, that if Hanes signified the fountain of light, as I have presumed, it would have been differently expressed in the Hebrew. This is a strange fallacy; but yet very predominant. Without doubt those learned men, who have preceded in these researches, would have bid fair for noble discoveries, had they not been too limited, and biassed, in their notions. But as far as I am able to judge, most of those, who have engaged in inquiries of this nature, have ruined the purport of their labours through some prevailing prejudice. They have not considered, that every other nation, to which we can possibly gain access, or from whom we have any history derived, appears to have expressed foreign terms differently from the natives, in whose language they were found. And without a miracle the Hebrews must have done the same. We pronounce all French names differently from the people of that country: and they do the same in respect to us. What we call London, they express Londres: England they style Angleterre. What some call Bazil, they pronounce Bal: Munchen, Munich: Mentz, Mayence: Ravenspurg, Ratisbon. The like variation was observable of old. Carthago of the Romans was Carchedon among the Greeks. Hannibal was rendered Annibas: Asdrubal, Asdroubas: and probably neither was consonant to the Punic mode of expression. If then a prophet were to rise from the dead, and preach to any nation, he would make use of terms adapted to their idiom and usage; without any retrospect to the original of the terms, whether they were domestic, or foreign. The sacred writers undoubtedly observed this rule towards the people, for whom they wrote; and varied in their expressing of foreign terms; as the usage of the people varied. For the Jewish nation at times differed from its neighbours, and from itself. We may be morally certain, that the place, rendered by them Ekron, was by the natives called Achoron; the Accaron, Ακκαρων, of Josephus, and the Seventy. What they termed Philistim, was Pelestin: Eleazar, in their own language, they changed to Lazar, and Lazarus: and of the Greek συνεδριον they formed Sanhedrim. Hence we may be certified, that the Jews, and their ancestors, as well as all nations upon earth, were liable to express foreign terms with a variation, being led by a natural peculiarity in their mode of speech. They therefore are surely to be blamed, who would deduce the orthography of all antient words from the Hebrew; and bring every extraneous term to that test. It requires no great insight into that language to see the impropriety of such procedure. Yet no prejudice has been more [598]common. The learned Michaelis has taken notice of this [599]fatal attachment, and speaks of it as a strange illusion. He says, that it is the reigning influenza, to which all are liable, who make the Hebrew their principal study. The only way to obtain the latent purport of antient terms is by a fair analysis. This must be discovered by an apparent analogy; and supported by the history of the place, or person, to whom the terms relate. If such helps can be obtained, we may determine very truly the etymology of an Egyptian or Syriac name; however it may appear repugnant to the orthography of the Hebrews. The term Hanes is not so uncommon as may be imagined. Zeus was worshipped under this title in Greece, and styled Ζευς Αινησιος. The Scholiast upon Apollonius Rhodius mentions his temple, and terms it [600]Διος Αινησιου ἱερον ου μνημονευει και Λεων εν περιπλῳ, και Δημοσθενης εν λιμεσι. It is also taken notice of by Strabo, who speaks of a mountain Hanes, where the temple stood. [601]Μεγιστον δε ορος εν αυτῃ Αινος (lege Αινης) εν ᾡ το του Διος Αινησιου ἱερον. The mountain of Zeus Ainesius must have been Aines, and not Ainos; though it occurs so in our present copies of Strabo. The Scholiast above quotes a verse from Hesiod, where the Poet styles the Deity Αινηιος.

Ενθ' ὁιγ' ευχεσθην Αινηιῳ ὑψιμεδοντι.

Aineïus, and Ainesius are both alike from Hanes, the Deity of Egypt, whose rites may be traced in various parts. There were places named Aineas, and Ainesia in Thrace; which are of the same original. This title occurs sometimes with the prefix Ph'anes: and the Deity so called was by the early theologists thought to have been of the highest antiquity. They esteemed him the same as [602]Ouranus, and Dionusus: and went so far as to give him a creative [603]power, and to deduce all things from him. The Grecians from Phanes formed Φαναιος, which they gave as a title both to [604]Zeus, and Apollo. In this there was nothing extraordinary, for they were both the same God. In the north of Italy was a district called Ager [605]Pisanus. The etymology of this name is the same as that of Hanes, and Phanes; only the terms are reversed. It signifies ignis fons: and in confirmation of this etymology I have found the place to have been famous for its hot streams, which are mentioned by Pliny under the name of Aquæ Pisanæ. Cuma in Campania was certainly denominated from Chum, heat, on account of its soil, and situation. Its medicinal [606]waters are well known; which were called Aquæ Cumanæ. The term Cumana is not formed merely by a Latine inflection; but consists of the terms Cumain, and signifies a hot fountain; or a fountain of Chum, or Cham, the Sun. The country about it was called Phlegra; and its waters are mentioned by Lucretius.

[607]Qualis apud Cumas locus est, montemque Vesevum,

Oppleti calidis ubi fumant fontibus auctus.

Here was a cavern, which of old was a place of prophecy. It was the seat of the Sibylla Cumana, who was supposed to have come from [608]Babylonia. As Cuma was properly Cuman; so Baiæ was Baian; and Alba near mount Albanus[609], Alban: for the Romans often dropped the n final. Pisa, so celebrated in Elis, was originally Pisan, of the same purport as the Aquæ Pisanæ above. It was so called from a sacred fountain, to which only the name can be primarily applicable: and we are assured by Strabo [610]Την κρηνην Πισαν ειρησθαι, that the fountain had certainly the name of Pisan. I have mentioned that Mount Pyrene was so called from being a fountain of fire: such mountains often have hot streams in their vicinity, which are generally of great utility. Such we find to have been in Aquitania at the foot of this mountain, which were called Thermæ Onesæ; and are mentioned by Strabo, as [611]Θερμα καλλιστα ποτιμωτατου ὑδατος. What in one part of the world was termed Cumana, was in another rendered Comana. There was a grand city of this name in Cappadocia, where stood one of the noblest Puratheia in Asia. The Deity worshipped was represented as a feminine, and styled Anait, and Anaïs; which latter is the same as Hanes. She was well known also in Persis, Mesopotamia, and at Egbatana in Media. Both An-ait, and An-ais, signifies a fountain of fire. Generally near her temples, there was an eruption of that element; particularly at Egbatana, and Arbela. Of the latter Strabo gives an account, and of the fiery matter which was near it. [612]Περι Αρβηλα δε εστι και Δημητριας πολις· ειθ' ἡ του ναφθα πηγη, και τα πυρα (or πυρεια) και το της Αναιας ἱερον.

I should take the town of Egnatia in Italy to have been of the same purport as Hanes above mentioned: for Hanes was sometimes expressed with a guttural, Hagnes; from whence came the ignis of the Romans. In Arcadia near mount Lyceus was a sacred fountain; into which one of the nymphs, which nursed Jupiter, was supposed to have been changed. It was called Hagnon, the same as Ain-On, the fount of the Sun. From Ain of the Amonians, expressed Agn, came the ἁγνος of the Greeks, which signified any thing pure and clean; purus sive castus. Hence was derived ἁγνειον, πηγαιον· ἁγναιον, καθαρον· ἁγνη, καθαρα: as we may learn from Hesychius. Pausanias styles the fountain [613]Hagno: but it was originally Hagnon, the fountain of the Sun: hence we learn in another place of Hesychius, ἁγνοπολεισθαι, το ὑπο ἡλιου θερεσθαι. The town Egnatia, which I mentioned above, stood in campis Salentinii, and at this day is called Anazo, and Anazzo. It was so named from the rites of fire: and that those customs were here practised, we may learn from some remains of them among the natives in the times of Horace and Pliny. The former calls the place by contraction [614]Gnatia:

Dein Gnatia Nymphis

Iratis extructa dedit risumque, jocumque;

Dum flammis sine thura liquescere limine sacro

Persuadere cupit.

Horace speaks as if they had no fire: but according to Pliny they boasted of having a sacred and spontaneous appearance of it in their temple. [615]Reperitur apud auctores in Salentino oppido Egnatiâ, imposito ligno in saxum quoddam ibi sacram protinus flammam existere. From hence, undoubtedly, came also the name of Salentum, which is a compound of Sal-En, Solis fons; and arose from this sacred fire to which the Salentini pretended. They were Amonians, who settled here, and who came last from Crete [616]Τους δε Σαλεντινους Κρητων αποικους φασι. Innumerable instances of this sort might be brought from Sicily: for this island abounded with places, which were of Amonian original. Thucydides and other Greek writers, call them Phenicians[617]: Ωκουν δε και Φοινικες περι πασαν μεν Σικελιαν. But they were a different people from those, which he supposes. Besides, the term Phenician was not a name, but a title: which was assumed by people of different parts; as I shall shew. The district, upon which the Grecians conferred it, could not have supplied people sufficient to occupy the many regions, which the Phenicians were supposed to have possessed. It was an appellation, by which no part of Canaan was called by the antient and true inhabitants: nor was it ever admitted, and in use, till the Grecians got possession of the coast. It was even then limited to a small tract; to the coast of Tyre and Sidon.

If so many instances may be obtained from the west, many more will be found, as we proceed towards the east; from whence these terms were originally derived. Almost all the places in Greece were of oriental etymology; or at least from Egypt. I should suppose that the name of Methane in the Peloponnesus had some relation to a fountain, being compounded of Meth-an, the fountain of the Egyptian Deity, Meth, whom the Greeks called Μητις, Meetis.

[618]Και Μητις πρωτος γενετωρ, και Ερως πολυτερπης.

We learn from [619]Pausanias, that there was in this place a temple and a statue of Isis, and a statue also of Hermes in the forum; and that it was situated near some hot springs. We may from hence form a judgment, why this name was given, and from what country it was imported. We find this term sometimes compounded Meth-On, of which name there was a town in [620]Messenia. Instances to our purpose from Greece will accrue continually in the course of our work.

One reason for holding waters so sacred arose from a notion, that they were gifted with supernatural powers. Jamblichus takes notice of many ways, by which the gift of divination was to be obtained. [621]Some, says he, procure a prophetic spirit by drinking the sacred water, as is the practice of Apollo's priest at Colophon. Some by sitting over the mouth of the cavern, as the women do, who give out oracles at Delphi. Others are inspired by the vapour, which arises from the waters; as is the case of those who are priestesses at Branchidæ. He adds,[622] in respect to the oracle at Colophon, that the prophetic spirit was supposed to proceed from the water. The fountain, from whence it flowed, was in an apartment under ground; and the priest went thither to partake of the emanation. From this history of the place we may learn the purport of the name, by which this oracular place was called. Colophon is Col-Oph On, tumulus Dei Solis Pythonis, and corresponds with the character given. The river, into which this fountain ran, was sacred, and named Halesus; it was also called [623]Anelon: An-El-On, Fons Dei Solis. Halesus is composed of well-known titles of the same God.

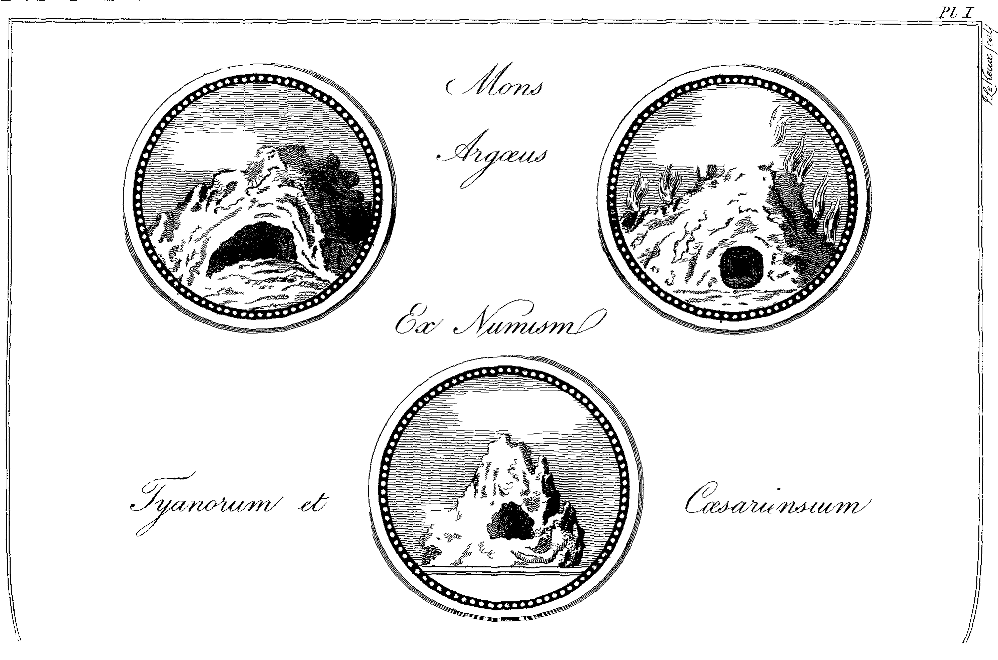

Delos was famed for its oracle; and for a fountain sacred to the prophetic Deity. It was called [624]Inopus. This is a plain compound of Ain-Opus, Fons Pythonis. Places named Asopus, Elopus, and like, are of the same analogy. The God of light, Orus, was often styled Az-El; whence we meet with many places named Azelis, Azilis, Azila, and by apocope, Zelis, Zela, and Zeleia. In Lycia was the city Phaselis, situated upon the mountain [625]Chimæra; which mountain had the same name, and was sacred to the God of fire. Phaselis is a compound of Phi, which, in the Amonian language, is a mouth or opening; and of Azel above mentioned. Ph'Aselis signifies Os Vulcani, sive apertura ignis; in other words a chasm of fire. The reason why this name was imposed may be seen in the history of the place[626]. Flagrat in Phaselitide Mons Chimæra, et quidem immortali diebus, et noctibus flammâ. Chimæra is a compound of Cham-Ur, the name of the Deity, whose altar stood towards the top of the [627]mountain. At no great distance stood Mount Argaius, which was a part of the great ridge, called Taurus. This Argaius may be either derived from Har, a mountain; or from Aur, fire. We may suppose Argaius to signify Mons cavus: or rather ignis cavitas, sive Vulcani domus, a name given from its being hollow, and at the same time a reservoir of fiery matter. The history of the mountain may be seen in Strabo; who says, that it was immensely high, and ever covered with snow; it stood in the vicinity of Comana, Castabala, Cæsarea, and Tyana: and all the country about it abounded with fiery [628]eruptions. But the most satisfactory idea of this mountain may be obtained from coins, which were struck in its vicinity; and particularly [629]describe it, both as an hollow and an inflamed mountain.

In Thrace was a region called Pæonia, which seems to have had its name from P'Eon, the God of light[630]. The natives of these parts were styled both Peonians and Pierians; which names equally relate to the Sun. Agreeably to this Maximus Tyrius tells us, that they particularly worshipped that luminary: and adds, that they had no image; but instead of it used to suspend upon an high pole a disk of metal, probably of fine gold, as they were rich in that mineral: and before this they performed their [631]adoration.

There is an apparent analogy between the names of places farther east; whose inhabitants were all worshippers of the Sun. Hence most names are an assemblage of his titles. Such is Cyrestia, Chalybon, Comana, Ancura, Cocalia, Cabyra, Arbela, Amida, Emesa, Edessa, and the like. Emesa is a compound of Ham-Es: the natives are said by Festus Avienus to have been devoted to the Sun:

[632]Denique flammicomo devoti pectora Soli

Vitam agitant.

Similar to Emesa was Edessa, or more properly Adesa, so named from Hades, the God of light. The emperor Julian styles the region—Ἱερον εξ αιωνος τῳ Ἡλιῳ [633]Χωριον. This city was also, from its worship, styled [634]Ur, Urhoe, and Urchoë; which last was probably the name of the [635]temple.

There were many places called Arsene, Arsine, Arsinoë, Arsiana. These were all the same name, only varied in different countries; and they were consequently of the same purport. Arsinoë is a compound of arez-ain, Solis fons: and most places so denominated will be found famed for some fountain. One of this name was in Syria; [636]Αρσινοη πολις εν Συριᾳ, επι βουνῳ κειμενη. απο δε του βουνου κρηνας ερευγεται πλειονας—αφ' ὡν ἡ πολις ωνομασται. Arsinoë is a city in Syria, situated upon a rising ground, out of which issue many streams: from hence the city had its name. Arsine and Arsiana in Babylonia had [637]fountains of bitumen. Arsene in Armenia was a nitrous lake: [638]Αρσηνη λιμην—νιτριτις. Near Arsinoë, upon the Red Sea, were hot streams of bitter [639]waters; and Arsinoë near [640]Ephesus had waters equally bitter.

There were many people called Hyrcani; and cities and regions, Hyrcania: in the history of which there will be uniformly found some reference to fire. The name is a compound of Ur-chane, the God of that element. He was worshipped particularly at Ur, in Chaldea: and one tribe of that nation were called Urchani. Strabo mentions them as only one branch of the [641]literati; but [642]Pliny speaks of them as a people, a tribe of the Chaldeans. Here was the source of fire worship: and all the country was replete with bitumen and fire. There was a region [643]Hyrcania, inhabited by the Medes; which seems to have been of the same inflammable nature. The people were called Hyrcani, and Astabeni: which latter signifies the sons of fire. Celiarius mentions a city Hyrcania in [644]Lydia. There were certainly people styled Hyrcani; and a large plain called Campus Hyrcanus [645] in the same part of the world. It seems to have been a part of that parched and burning region called κατακεκαυμενη, so named from the fires with which it abounded. It was near Hierapolis, Caroura, and Fossa Charonea; all famed for fire.

It may seem extraordinary, yet I cannot help thinking, that the Hercynian forest in Germany was no other than the Hurcanian, and that it was denominated from the God Urcan, who was worshipped here as well as in the east. It is mentioned by Eratosthenes and Ptolemy, under the name of δρυμος Ορκυνιος, or the forest of [646]Orcun; which is, undoubtedly, the same name as that above. I have taken notice, that the name of the mountain Pyrene signified a fountain of fire, and that the mountain had once flamed. There was a Pyrene among the Alpes [647]Tridentini, and at the foot of it a city of the same [648]name; which one would infer to have been so denominated from the like circumstance. I mention this, because here was the regio Hercynia, where the Hercynian forest[649] commenced, and from which it received its name. Beatus Rhenanus, in his account of these parts, says, that there was a tradition of this mountain Pyrene once[650] burning: and, conformably to this notion, it is still distinguished by the name of the great [651]Brenner. The country, therefore, and the forest may have been called Orcunian upon this account. For as the worship of the Sun, the Deity of fire, prevailed greatly at places of this nature, I make no doubt but Hercynia, which Ptolemy expresses Ορκυνια was so named from Or-cun, the God of that element.

We must not be surprised to find Amonian names among the Alpes; for some of that family were the first who passed them. The merit of great performances was by the Greeks generally attributed to a single person. This passage therefore through the mountains is said by some to have been the work of Hercules: by others of Cottus, and [652]Cottius. From hence this particular branch of the mountains had the name of Alpes Cottiae; and the country was called Regio Cottiana: wherein were about twelve capital [653]cities. Some of that antient and sacred nation, the Hyperboreans, are said by Posidonius to have taken up their residence in these parts. [654]Τους Ὑπερβορεους—οικειν περι τας Αλπεις της Ιταλιας. Here inhabited the Taurini: and one of the chief cities was Comus. Strabo styles the country the land of [655]Ideonus, and Cottius. These names will be found hereafter to be very remarkable. Indeed many of the Alpine appellations were Amonian; as were also their rites: and the like is to be observed in many parts of Gaul, Britain, and Germany. Among other evidences the worship of Isis, and of her sacred ship, is to be noted; which prevailed among the Suevi. [656]Pars Suevorum et Isidi sacrificat: unde causa et origo peregrino sacro, parum comperi; nisi quod signum ipsum in modum Liburnæ figuratum docet advectam religionem. The ship of Isis was also reverenced at Rome: and is marked in the [657]calendar for the month of March. From whence the mystery was derived, we may learn from [658]Fulgentius. Navigium Isidis Ægyptus colit. Hence we find, that the whole of it came from Egypt. The like is shewn by [659]Lactantius. To this purpose I could bring innumerable proofs, were I not limited in my progress. I may perhaps hereafter introduce something upon this head, if I should at any time touch upon the antiquities of Britain and Ireland; which seem to have been but imperfectly known. Both of these countries, but especially the latter, abound with sacred terms, which have been greatly overlooked. I will therefore say so much in furtherance of the British Antiquarian, as to inform him, that names of places, especially of hills, promontories, and rivers, are of long duration; and suffer little change. The same may be said of every thing, which was esteemed at all sacred, such as temples, towers, and high mounds of earth; which in early times were used for altars. More particularly all mineral and medicinal waters will be found in a great degree to retain their antient names: and among these there may be observed a resemblance in most parts of the world. For when names have been once determinately affixed, they are not easily effaced. The Grecians, who under Alexander settled in Syria, and Mesopotamia, changed many names of places, and gave to others inflections, and terminations after the mode of their own country. But Marcellinus, who was in those parts under the Emperor Julian, assures us, that these changes and variations were all cancelled: and that in his time the antient names prevailed. Every body, I presume, is acquainted with the history of Palmyra, and of Zenobia the queen; who having been conquered by the emperor Aurelian, was afterwards led in triumph. How much that city was beautified by this princess, and by those of her family, may be known by the stately ruins which are still extant. Yet I have been assured by my late excellent and learned friend Mr. Wood, that if you were to mention Palmyra to an Arab upon the spot, he would not know to what you alluded: nor would you find him at all more acquainted with the history of Odænatus, and Zenobia. Instead of Palmyra he would talk of Tedmor; and in lieu of Zenobia he would tell you, that it was built by Salmah Ebn Doud, that is by Solomon the son of David. This is exactly conformable to the account in the scriptures: for it is said in the Book of Chronicles, [660]He also (Solomon) built Tadmor in the wilderness. The Grecian name Palmyra, probably of two thousand years standing, is novel to a native Arab.

As it appeared to me necessary to give some account of the rites, and worship, in the first ages, at least in respect to that great family, with which I shall be principally concerned, I took this opportunity at the same time to introduce these etymological inquiries. This I have done to the intent that the reader may at first setting out see the true nature of my system; and my method of investigation. He will hereby be able to judge beforehand of the scope which I pursue; and of the terms on which I found my analysis. If it should appear that the grounds, on which I proceed, are good, and my method clear, and warrantable, the subsequent histories will in consequence of it receive great illustration. But should it be my misfortune to have my system thought precarious, or contrary to the truth, let it be placed to no account, but be totally set aside: as the history will speak for itself; and may without these helps be authenticated.

Pl. I. Mons Argæus Ex Numism Tyanorum et Cæsariensium

Footnotes

[568] Genesis. c. 10. v. 5.

[569] Strabo. l. 5. p. 346.

[570] Virgil. Æn. l. xi. v. 785.

[571] Servius upon the foregoing passage.

[572] Cluver. Italia. l. 2. p. 719.

[573] Livy. l. 1. c. 49. Pompeius Festus.

[574] Not far from hence was a district called Ager Solonus. Sol-On is a compound of the two most common names given to the Sun, to whom the place and waters were sacred.

[575] Dionysius Halicarnassensis. l. 3.

[576] Herodotus. l. 1. c. 138.

Θυουσι δε και ὑδατι και ανεμοισιν (ὁι Περσαι). Herodotus. l. 1. c. 131.

Ridetis temporibus priscis Persas fluvium coluisse. Arnobius adversus Gentes. l. 6. p. 196.

[577] Αλλοι ποταμους και κρηνας, και παντων μαλιστα ὁι Αιγυπτιοι προτετιμηκασι, και Θεους αναγορευουσι. Athanasius adversus Gentes. p. 2.

Αιγυπτιοι ὑδατι Θυουσι· καιτοι μεν ἁπασι καινον τοις Αιγυπτιοις το ὑδωρ. Lucian. Jupiter Tragœd. v. 2. p. 223. Edit. Salmurii.

[578] Julius Firmicus. p. 1.

[579] Gruter. Inscript. vol. 1. p. xciv.

[580] Senecæ Epist. 41.

[581] Herodotus. l. 4. c. 181. The true name was probably Curene, or Curane.

[582] Vitruvij Architect. l. 8. p. 163.

[583] Pliny. l. 4. c. 4. p. 192. Ovid. Metamorph. l. 2.

[584] Pausanias. l. 2. p. 117. Εστι γε δη και Απολλωνος αγαλμα προς τῃ Πειρηνῃ, και περιβολος εστιν.

Pirene and Virene are the same name.

[585] Pur, Pir, Phur, Vir: all signify fire.

[586] Diodorus Siculus. l. 5. p. 312.

[587] Diodorus Siculus. l. xi. p. 17.

[588] Strabo. l. 6. p. 412.

[589] Stephanus says that it was near Mount Casius; but Herodotus expressly tells us, that it was at the distance of three days journey from it.

[590] Απο ταυτης τα εμπορια τα επι θαλασσης μεχρι Ιηνισου πολιος εστι του Αραβικου. Herodotus. l. 3. c. 5.

[591] Τοδε μεταξυ Ιηνισου πολιος, και Κασιου τε ουρεος, και της Σερβωνιδος λιμνης, εον ουκ ολιγον χωριον, αλλ' ὁσον επι τρεις ἡμερας ὁδον, ανυδρον εστι δεινος. Herodotus. ibidem.

[592] Go-zan is the place, or temple, of the Sun. I once thought that Goshen, or, as it is sometimes expressed, Gozan, was the same as Cushan: but I was certainly mistaken. The district of Goshen was indeed the nome of Cushan; but the two words are not of the same purport. Goshen is the same as Go-shan, and Go-zan, analogous to Beth-shan, and signifies the place of the Sun. Go-shen, Go-shan, Go-zan, and Gau-zan, are all variations of the same name. In respect to On, there were two cities so called. The one was in Egypt, where Poti-phera was Priest. Genesis. c. 41. v. 45. The other stood in Arabia, and is mentioned by the Seventy: Ων, ἡ εστιν Ἡλιουπολις. Exodus. c. 1. v. 11. This was also called Onium, and Hanes, the Iänisus of Herodotus.

[593] Isaiah. c. 30. v. 4.

[594] See Observations upon the Antient History of Egypt. p. 124. p. 137.

[595] D'Anville Memoires sur l'Egypt. p. 114.

[596] Travels. vol. 2. p. 107. It is by them expressed Ain el Cham, and appropriated to the obelisk: but the meaning is plain.

[597] Bochart. Geog. Sacra. l. 1. c. 35. p. 638.

[598] See page 72. notes.

[599] Dissertation of the influence of opinion upon language, and of language upon opinion. Sect. vi. p. 67. of the translation.

[600] Scholia upon Apollonius. l. 2. v. 297.

[601] Strabo. l. 10. p. 700.

[602] Orphic Hymn. 4.

[603] Ὁι Θεολογοι—ενι γε τῳ Φανητι την δημιουργικην αιτιαν ανυμνησαν. Orphic Fragment. 8. from Proclus in Timæum.

[604] Συ μοι Ζευς ὁ Φαναιο, ἡκεις. Eurip. Rhesus. v. 355.

Φαναιος Απολλων εν Χιοις. Hesych.

[605] Pliny. l. 2. c. 106. p. 120.

[606] Λουτρα τε παρεχει το χωριον θερμα, γηθεν αυτοματα ανιοντα. Josephi Antiq. l. 18. c. 14.

[607] Lucretius. l. 6.

[608] Justin Martyr. Cohort. p. 33.

[609] Mount Albanus was denominated Al-ban from its fountains and baths.

[610] Strabo. l. 8. p. 545.

[611] Strabo. l. 4. p. 290. Onesa signifies solis ignis, analogous to Hanes.

[612] Strabo. l. 16. p. 1072. see also l. 11. p. 779. and l. 12. p. 838. likewise Plutarch in Artaxerxe.

[613] Pausanias. l. 8. p. 678.

[614] Horace. l. 1. sat. 5. v. 97.

[615] Pliny. l. 2. c. 110. p. 123.

[616] Strabo. l. 6. p. 430.

The antient Salentini worshipped the Sun under the title of Man-zan, or Man-zana: by which is meant Menes, Sol. Festus in V. Octobris.

[617] Thucydides. l. 6. c. 2. p. 379.

[618] Orphic Fragment. vi. v. 19. from Proclus. p. 366.

Μητις, divine wisdom, by which the world was framed: esteemed the same as Phanes and Dionusus.

Αυτος τε ὁ Διονυσος, και Φανης, και Ηρικεπαιος. Ibidem. p. 373.

Μητις—ἑρμηνευεται, Βουλη. Φως, Ζωοδοτηρ—from Orpheus: Eusebij Chronicon. p. 4.

[619] Ισιδος ενταυθα Ἱερον, και αγαλμα, και επι της αγορας Ἑρμου—και θερμα λουτρα. Pausan. l. 2. p. 190.

[620] Pausanas. l. 4. p. 287.

[621] Ὁιδ' ὑδωρ πιοντες, καθαπερ ὁ εν Κολοφωνι Ἱερευς του Κλαριου. Ὁιδε στομιοις παρακαθημενοι, ὡς ἁι εν Δελφοις θεσπιζουσαι. Ὁιδ' εξ ὑδατων ατμιζομενοι, καθαπερ ἁι εν Βραγχιδαις Προφητιδες. Jamblichus de Mysterijs. sec. 3. c. xi. p. 72

[622] Τοδε εν Κολοφωνι μαντειον ὁμολογειται παρα πασι δια ὑδατος χρηματιζειν· ειναι γαρ πηγην εν οικῳ καταγειῳ, και απ' αυτης πιειν την Προφητην. Jamblichus. ibid.

[623] Pausanias. l. 8. p. 659. Ανελοντος του εν Κολοφωνι και Ελεγειων ποιηται ψυχροτητα αδουσι.

[624] Callimachus: Hymn to Delos.

Strabo l. 10 p.742.

[625] Pliny. l. 2. c. 106. p. 122.

[626] Pliny above.

Ὁτι πυρ εστιν εγγυς Φασηλιδος εν Λυκιᾳ αθανατον, και ὁτι αει καιεται επι πετρας, και νυκτα, και ἡμεραν. Ctesias apud Photium. clxxiii.

Παντες, ὁσοι Φοινικον εδος περι παγνυ νεμονται,

Αιπυ τε Μασσικυτοιο ῥοον, βωμον γε Χιμαιρας. Nonnus. l. 3.

[628] Strabo. l. 12. p. 812. For the purport of Gaius, domus vel cavitas. See Radicals. p. 122.

[629] Patinæ Numismata Imperatorum. p. 180. l. 194.

[630] He was called both Peon and Peor: and the country from him Peonia and Pieria. The chief cities were Alorus, Aineas, Chamsa, Methone: all of oriental etymology.

[631] Παιονες σεβουσι τον ἡλιον· αγαλμα δε ἡλιου Παιονικον δισκος βραχυς ὑπερ μακρου ξυλου. Maximus Tyrius. Dissert. 8. p. 87.

Of the wealth of this people, and of their skill in music and pharmacy; See Strabo. Epitom. l. vii.

[632] Rufus Festus Avienus, Descrip. Orbis. v. 1083.

[633] Juliani Oratio in Solem. Orat. 4. p. 150.

Ἱερωνται δε αυτοι (Εδεσσηνοι) τῳ θεῳ ἡλιῳ· τουτον γαρ ὁι επιχωριοι σεβουσι, τῃ Φοινικων φωνῃ Ελαγαβαλον καλουντες. Herodian. l. 3.

[634] Edesseni Urchoienses—Urhoe, ignis, lux, &c. Theoph. Sigefredi Bayeri Hist. Osrhoena. p. 4.

[635] Ur-choë signifies Ori domus, vel templum; Solis Ædes.

Ur in Chaldea is, by Ptolemy, called Orchoe.

[636] Etymologicum magnum. The author adds: αρσαι γαρ το ποτισαι, as if it were of Grecian original.

[637] Marcellinus. l. 23. p. 287.

[638] Αρσηνη λιμνη, ἡν και Θωνιτιν καλουσι—εστι δε νιτριτις. Strabo. l. xi. p. 801.

[639] Πρωτον μεν απ' Αρσινοης παραθεοντι την δεξιαν ηπειρον θερμα πλειοσιν αυλοις εκ πετρης ὑψηλης εις θαλατταν διηθειται. Agatharchides de Rubro mari. p. 54.

Ειτα αλλην πολιν Αρσινοην· ειτα θερμων ὑδατων εκβολας, πικρων και ἁλμυρων. Strabo. l. 16. p. 1114.]

[640] Some make Ephesus and Arsinoë to have been the same. See Scholia upon Dionysius. v. 828.

[641] Strabo. l. l6. p. 1074. See Radicals. p. 50.

[642] Pliny. l. 6. c. 27. Euphraten præclusere Orcheni: nec nisi Pasitigri defertur ad mare.

[643] Ptolemy Geog.

Isidorus Characenus. Geog. Vet. vol. 2. p. 7.

[644] Cellarii Geog. vol. 2. p. 80.

[645] Strabo. l. 12. p. 868, 869. and l. 13. p. 929-932.

Εστι δε επιφανεια τεφρωδης των πεδιων.

Strabo supposes that the Campus Hyrcanus was so named from the Persians; as also Κυρου πεδιον, near it; but they seem to have been so denominated ab origine. The river Organ, which ran, into the Mæander from the Campus Hyrcanus, was properly Ur-chan. Ancyra was An-cura, so named a fonte Solis κυρος γαρ ὁ ἡλιος. All the names throughout the country have a correspondence: all relate either to the soil, or the religion of the natives; and betray a great antiquity.

[646] Ptolemy. Geog. l. 2. c. 11.

[647] Mentioned in Pliny's Panegyric: and in Seneca; consolatio ad Helv. l. 6. Aristotle in Meteoris.

[648] Here was one of the fountains of the Danube. Ιστρος τε γαρ ποταμος αρξαμενος εκ Κελτων και Πυρηνης πολιος ῥεει, μεσην σχιζων την Ευρωπην. Herodotus. l. 2. c. 33.

[649] See Cluverii Germania.

[650] Beatus Rhenanus. Rerum Germanic. l. 3.

[651] It is called by the Swiss, Le Grand Brenner: by the other Germans, Der gross Verner.

Mount Cænis, as we term it, is properly Mount Chen-Is, Mons Dei Vulcani. It is called by the people of the country Monte Canise; and is part of the Alpes Cottiæ. Cluver. Ital. vol. 1. l. 1. c. 32. p. 337. Mons Geneber. Jovij.

[652] See Marcellinus. l. 15. c. 10. p. 77. and the authors quoted by Cluverius. Italia Antiqua above.

They are styled Αλπεις Σκουτιαι by Procopius: Rerum Goth. l. 2.

Marcellinus thinks, that a king Cottius gave name to these Alps in the time of Augustus, but Cottius was the national title of the king; as Cottia was of the nation: far prior to the time of Augustus.

[653] Pliny. l. 3. c. 20. Cottianæ civitates duodecim.

[654] Scholia upon Apollonius. l. 2. v. 677.

[655] Τουτων δε εστι και ἡ του Ιδεοννου γη, και ἡ του Κοττιου. Strabo. l. 4. p. 312

[656] Tacitus de Moribus Germanorum.

[657] Gruter. vol. 1. p. 138.

[658] Fulgentius: Mytholog. l. 1. c. 25. p. 655.

[659] Lactantius de falsa Relig. vol. 1. l. 1. c. 11. p. 47.

To these instances add the worship of Seatur, and Thoth, called Thautates. See Clunerii Germania. l. 1. c. 26. p. 188 and 189.

[660] 2 Chronicles. c. 8. v. 4.

Index | Next: Of Worship Paid At Caverns And Of The Adoration Of Fire