NYX

Night And Her ChildrenTO NIGHT.

The FUMIGATION with TORCHES.

NIGHT, parent goddess, source of sweet repose,

From whom at first both Gods and men arose,

Hear, blessed Venus, deck'd with starry light,

In sleep's deep silence dwelling Ebon night!

Dreams and soft case attend thy dusky train,

Pleas'd with the length'ned gloom and fearful strain.

Dissolving anxious care, the friend of Mirth,

With darkling coursers riding round the earth.

Goddess of phantoms and of shadowy play,

Whose drowsy pow'r divides the nat'ral day:

By Fate's decree you constant send the light

To deepest hell, remote from mortal sight

For dire Necessity which nought withstands,

Invests the world with adamantine bands.

Be present, Goddess, to thy suppliant's pray'r,

Desir'd by all, whom all alike revere,

Blessed, benevolent, with friendly aid

Dispell the fears of Twilight's dreadful shade.

From The Hymns of Orpheus

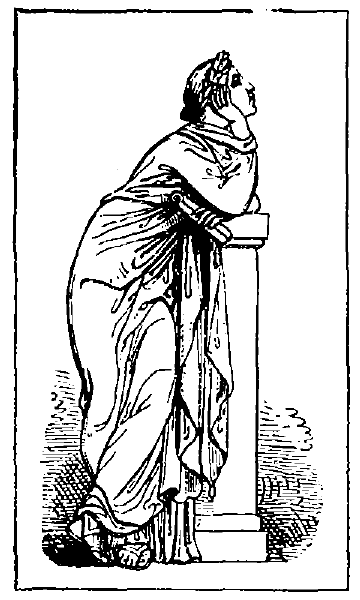

Nox or Night personified. Homer calls her the subduer of gods and men, and relates that Zeus himself stood in awe of her.

In the ancient cosmogonies Night is one of the very first created beings, for she is described as the daughter of Chaos, and the sister of Erebus, by whom she became the mother of Aether and Hemera. (Theogony of Hesiod 123) According to the Orphics she was the daughter of Eros.

She is further said, without any husband, to have given birth to Moros, the Keres, Thanatos, Hypnos, Dreams, Momus, Oizys, the Hesperides, Moerae, Nemesis, and similar beings. (Theogony of Hesiod 211)

In later poets, with whom she is merely the personification of the darkness of night, she is sometimes described as a winged goddess and sometimes as riding in a chariot, covered with a dark garment and accompanied by the stars in her course. (Aeneid Book V)

Her residence was in the darkness of Hades. (Theogony of Hesiod 748. The Aeneid Book VI)

A statue of Night, the work of Rhoecus, existed at Ephesus. On the chest of Cypselus she was represented carrying in her arms the gods of Sleep and Death, as two boys.

From Theogony of Hesiod

(ll. 211-225) "And Night bare hateful Doom and black Fate and Death, and she bare Sleep and the tribe of Dreams. And again the goddess murky Night, though she lay with none, bare Blame and painful Woe, and the Hesperides who guard the rich, golden apples and the trees bearing fruit beyond glorious Oceanus. Also she bare the Destinies and ruthless avenging Fates, Clotho and Lachesis and Atropos, who give men at their birth both evil and good to have, and they pursue the transgressions of men and of gods: and these goddesses never cease from their dread anger until they punish the sinner with a sore penalty. Also deadly Night bare Nemesis (Indignation) to afflict mortal men, and after her, Deceit and Friendship and hateful Age and hard-hearted Strife."

NIGHT AND HER CHILDREN.

DEATH, SLEEP, AND DREAMS.

NYX

Nyx, the daughter of Chaos, being the personification of Night, was, according to the poetic ideas of the Greeks, considered to be the mother of everything mysterious and inexplicable, such as death, sleep, dreams, &c. She became united to Erebus, and their children were Aether and Hemera (Air and Daylight), evidently a simile of the poets, to indicate that darkness always precedes light.

Nyx inhabited a palace in the dark regions of the lower world, and is represented as a beautiful woman, seated in a chariot, drawn by two black horses. She is clothed in dark robes, wears a long veil, and is accompanied by the stars, which follow in her train.

THANATOS (Mors) AND HYPNUS (Somnus).

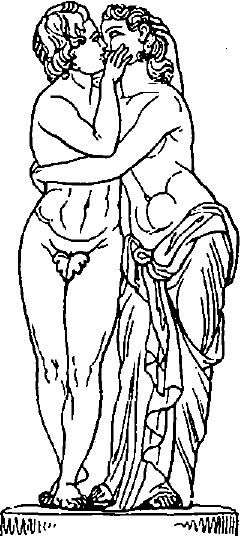

Thanatos (Death) and his twin-brother Hypnus (Sleep) were the children of Nyx.

Their dwelling was in the realm of shades, and when they appear among mortals, Thanatos is feared and hated as the enemy of mankind, whose hard heart knows no pity, whilst his brother Hypnus is universally loved and welcomed as their kindest and most beneficent friend.

But though the ancients regarded Thanatos as a gloomy and mournful divinity, they did not represent him with any exterior repulsiveness. On the contrary, he appears as a beautiful youth, who holds in his hand an inverted torch, emblematical of the light of life being extinguished, whilst his disengaged arm is thrown lovingly round the shoulder of his brother Hypnus.

Hypnus is sometimes depicted standing erect with closed eyes; at others he is in a recumbent position beside his brother Thanatos, and usually bears a poppy-stalk in his hand.

A most interesting description of the abode of Hypnus is given by Ovid in his Metamorphoses. He tells us how the god of Sleep dwelt in a mountain-cave near the realm of the Cimmerians, which the sun never pierced with his rays. No sound disturbed the stillness, no song of birds, not a branch moved, and no human voice broke the profound silence which reigned everywhere. From the lowermost rocks of the cave issued the river Lethe, and one might almost have supposed that its course was arrested, were it not for the low, monotonous hum of the water, which invited slumber. The entrance was partially hidden by numberless white and red poppies, which Mother Night had gathered and planted there, and from the juice of which she extracts drowsiness, which she scatters in liquid drops all over the earth, as soon as the sun-god has sunk to rest. In the centre of the cave stands a couch of blackest ebony, with a bed of down, over which is laid a coverlet of sable hue. Here the god himself reposes, surrounded by innumerable forms. These are idle dreams, more numerous than the sands of the sea. Chief among them is Morpheus, that changeful god, who may assume any shape or form he pleases. Nor can the god of Sleep resist his own power; for though he may rouse himself for a while, he soon succumbs to the drowsy influences which surround him.

MORPHEUS.

Morpheus, the son of Hypnus, was the god of Dreams.

He is always represented winged, and appears sometimes as a youth, sometimes as an old man. In his hand he bears a cluster of poppies, and as he steps with noiseless footsteps over the earth, he gently scatters the seeds of this sleep-producing plant over the eyes of weary mortals.

Homer describes the House of Dreams as having two gates: one, whence issue all deceptive and flattering visions, being formed of ivory; the other, through which proceed those dreams which are fulfilled, of horn.

THE GORGONS.

The Gorgons, Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa, were the three daughters of Phorcys and Ceto, and were the personification of those benumbing, and, as it were, petrifying sensations, which result from sudden and extreme fear.

They were frightful winged monsters, whose bodies were covered with scales; hissing, wriggling snakes clustered round their heads instead of hair; their hands were of brass; their teeth resembled the tusks of a wild boar; and their whole aspect was so appalling, that they are said to have turned into stone all who beheld them.

These terrible sisters were supposed to dwell in that remote and mysterious region in the far West, beyond the sacred stream of Oceanus.

The Gorgons were the servants of Aïdes, who made use of them to terrify and overawe those shades, doomed to be kept in a constant state of unrest as a punishment for their misdeeds, whilst the Furies, on their part, scourged them with their whips and tortured them incessantly.

The most celebrated of the three sisters was Medusa, who alone was mortal. She was originally a golden-haired and very beautiful maiden, who, as a priestess of Athene, was devoted to a life of celibacy; but, being wooed by Poseidon, whom she loved in return, she forgot her vows, and became united to him in marriage. For this offence she was punished by the goddess in a most terrible manner. Each wavy lock of the beautiful hair which had so charmed her husband, was changed into a venomous snake; her once gentle, love-inspiring eyes now became blood-shot, furious orbs, which excited fear and disgust in the mind of the beholder; whilst her former roseate hue and milk-white skin assumed a loathsome greenish tinge. Seeing herself thus transformed into so repulsive an object, Medusa fled from her home, never to return. Wandering about, abhorred, dreaded, and shunned by all the world, she now developed into a character, worthy of her outward appearance. In her despair she fled to Africa, where, as she passed restlessly from place to place, infant snakes dropped from her hair, and thus, according to the belief of the ancients, that country became the hotbed of these venomous reptiles. With the curse of Athene upon her, she turned into stone whomsoever she gazed upon, till at last, after a life of nameless misery, deliverance came to her in the shape of death, at the hands of Perseus.

It is well to observe that when the Gorgons are spoken of in the singular, it is Medusa who is alluded to.

Medusa was the mother of Pegasus and Chrysaor, father of the three-headed, winged giant Geryones, who was slain by Heracles.

GRÆÆ.

The Grææ, who acted as servants to their sisters the Gorgons, were also three in number; their names were Pephredo, Enyo, and Dino.

In their original conception they were merely personifications of kindly and venerable old age, possessing all its benevolent attributes without its natural infirmities. They were old and gray from their birth, and so they ever remained. In later times, however, they came to be regarded as misshapen females, decrepid, and hideously ugly, having only one eye, one tooth, and one gray wig between them, which they lent to each other, when one of them wished to appear before the world.

When Perseus entered upon his expedition to slay the Medusa, he repaired to the abode of the Grææ, in the far west, to inquire the way to the Gorgons, and on their refusing to give any information, he deprived them of their one eye, tooth, and wig, and did not restore them until he received the necessary directions.

SPHINX.

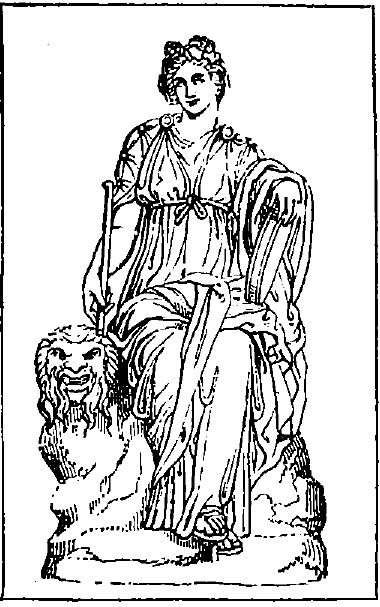

The Sphinx was an ancient Egyptian divinity, who personified wisdom, and the fertility of nature. She is represented as a lion-couchant, with the head and bust of a woman, and wears a peculiar sort of hood, which completely envelops her head, and falls down on either side of the face.

Transplanted into Greece, this sublime and mysterious Egyptian deity degenerates into an insignificant, and yet malignant power, and though she also deals in mysteries, they are, as we shall see, of a totally different character, and altogether inimical to human life.

The Sphinx is represented, according to Greek genealogy, as the offspring of Typhon and Echidna.* Hera, being upon one occasion displeased with the Thebans, sent them this awful monster, as a punishment for their offences. Taking her seat on a rocky eminence near the city of Thebes, commanding a pass which the Thebans were compelled to traverse in their usual way of business, she propounded to all comers a riddle, and if they failed to solve it, she tore them in pieces.

* Echidna was a bloodthirsty monster, half maiden, half serpent.

During the reign of King Creon, so many people had fallen a sacrifice to this monster, that he determined to use every effort to rid the country of so terrible a scourge. On consulting the oracle of Delphi, he was informed that the only way to destroy the Sphinx was to solve one of her riddles, when she would immediately precipitate herself from the rock on which she was seated.

Creon, accordingly, made a public declaration to the effect, that whoever could give the true interpretation of a riddle propounded by the monster, should obtain the crown, and the hand of his sister Jocaste. Œdipus offered himself as a candidate, and proceeding to the spot where she kept guard, received from her the following riddle for solution: "What creature goes in the morning on four legs, at noon on two, and in the evening on three?" Œdipus replied, that it must be man, who during his infancy creeps on all fours, in his prime walks erect on two legs, and when old age has enfeebled his powers, calls a staff to his assistance, and thus has, as it were, three legs.

The Sphinx no sooner heard this reply, which was the correct solution of her riddle, than she flung herself over the precipice, and perished in the abyss below.

The Greek Sphinx may be recognized by having wings and by being of smaller dimensions than the Egyptian Sphinx.

TYCHE (Fortuna) AND ANANKE (Necessitas).

TYCHE (Fortuna).

Tyche personified that peculiar combination of circumstances which we call luck or fortune, and was considered to be the source of all unexpected events in human life, whether good or evil. If a person succeeded in all he undertook without possessing any special merit of his own, Tyche was supposed to have smiled on his birth. If, on the other hand, undeserved ill-luck followed him through life, and all his efforts resulted in failure, it was ascribed to her adverse influence.

This goddess of Fortune is variously represented. Sometimes she is depicted bearing in her hand two rudders, with one of which she steers the bark of the fortunate, and with the other that of the unfortunate among mortals. In later times she appears blindfolded, and stands on a ball or wheel, indicative of the fickleness and ever-revolving changes of fortune. She frequently bears the sceptre and cornucopia* or horn of plenty, and is usually winged. In her temple at Thebes, she is represented holding the infant Plutus in her arms, to symbolize her power over riches and prosperity.

*One of the horns of the goat Amalthea, broken off by Zeus, and supposed to possess the power of filling itself with whatsoever its owner desired.

Tyche was worshipped in various parts of Greece, but more particularly by the Athenians, who believed in her special predilection for their city.

FORTUNA.

Tyche was worshipped in Rome under the name of Fortuna, and held a position of much greater importance among the Romans than the Greeks.

In later times Fortuna is never represented either winged or standing on a ball; she merely bears the cornucopia. It is evident, therefore, that she had come to be regarded as the goddess of good luck only, who brings blessings to man, and not, as with the Greeks, as the personification of the fluctuations of fortune.

In addition to Fortuna, the Romans worshipped Felicitas as the giver of positive good fortune.

ANANKE (Necessitas).

As Ananke, Tyche assumes quite another character, and becomes the embodiment of those immutable laws of nature, by which certain causes produce certain inevitable results.

In a statue of this divinity at Athens she was represented with hands of bronze, and surrounded with nails and hammers. The hands of bronze probably indicated the irresistible power of the inevitable, and the hammer and chains the fetters which she forged for man.

Ananke was worshipped in Rome under the name of Necessitas.

KER.

In addition to the Moiræ, who presided over the life of mortals, there was another divinity, called Ker, appointed for each human being at the moment of his birth. The Ker belonging to an individual was believed to develop with his growth, either for good or evil; and when the ultimate fate of a mortal was about to be decided, his Ker was weighed in the balance, and, according to the preponderance of its worth or worthlessness, life or death was awarded to the human being in question. It becomes evident, therefore, that according to the belief of the early Greeks, each individual had it in his power, to a certain extent, to shorten or prolong his own existence.

The Keres, who are frequently mentioned by Homer, were the goddesses who delighted in the slaughter of the battle-field.

ATE.

Ate, the daughter of Zeus and Eris, was a divinity who delighted in evil.

Having instigated Hera to deprive Heracles of his birthright, her father seized her by the hair of her head, and hurled her from Olympus, forbidding her, under the most solemn imprecations, ever to return. Henceforth she wandered among mankind, sowing dissension, working mischief, and luring men to all actions inimical to their welfare and happiness. Hence, when a reconciliation took place between friends who had quarrelled, Ate was blamed as the original cause of disagreement.

MOMUS.

Momus, the son of Nyx, was the god of raillery and ridicule, who delighted to criticise, with bitter sarcasm, the actions of gods and men, and contrived to discover in all things some defect or blemish. Thus when Prometheus created the first man, Momus considered his work incomplete because there was no aperture in the breast through which his inmost thoughts might be read. He also found fault with a house built by Athene because, being unprovided with the means of locomotion, it could never be removed from an unhealthy locality. Aphrodite alone defied his criticism, for, to his great chagrin, he could find no fault with her perfect form. According to another account, Momus discovered that Aphrodite made a noise when she walked.

In what manner the ancients represented this god is unknown. In modern art he is depicted like a king's jester, with a fool's cap and bells.

EROS (Cupid, Amor) AND PSYCHE.

According to Hesiod's Theogony, Eros, the divine spirit of Love, sprang forth from Chaos, while all was still in confusion, and by his beneficent power reduced to order and harmony the shapeless, conflicting elements, which, under his influence, began to assume distinct forms. This ancient Eros is represented as a full-grown and very beautiful youth, crowned with flowers, and leaning on a shepherd's crook.

In the course of time, this beautiful conception gradually faded away, and though occasional mention still continues to be made of the Eros of Chaos, he is replaced by the son of Aphrodite, the popular, mischief-loving little god of Love, so familiar to us all.

In one of the myths concerning Eros, Aphrodite is described as complaining to Themis, that her son, though so beautiful, did not appear to increase in stature; whereupon Themis suggested that his small proportions were probably attributable to the fact of his being always alone, and advised his mother to let him have a companion. Aphrodite accordingly gave him, as a playfellow, his younger brother Anteros (requited love), and soon had the gratification of seeing the little Eros begin to grow and thrive; but, curious to relate, this desirable result only continued as long as the brothers remained together, for the moment they were separated, Eros shrank once more to his original size.

By degrees the conception of Eros became multiplied and we hear of little love-gods (Amors), who appear under the most charming and diversified forms. These love-gods, who afforded to artists inexhaustible subjects for the exercise of their imagination, are represented as being engaged in various occupations, such as hunting, fishing, rowing, driving chariots, and even busying themselves in mechanical labour.

Perhaps no myth is more charming and interesting than that of Eros and Psyche, which is as follows:—Psyche, the youngest of three princesses, was so transcendently beautiful that Aphrodite herself became jealous of her, and no mortal dared to aspire to the honour of her hand. As her sisters, who were by no means equal to her in attractions, were married, and Psyche still remained unwedded, her father consulted the oracle of Delphi, and, in obedience to the divine response, caused her to be dressed as though for the grave, and conducted to the edge of a yawning precipice. No sooner was she alone than she felt herself lifted up, and wafted away by the gentle west wind Zephyrus, who transported her to a verdant meadow, in the midst of which stood a stately palace, surrounded by groves and fountains.

Here dwelt Eros, the god of Love, in whose arms Zephyrus deposited his lovely burden. Eros, himself unseen, wooed her in the softest accents of affection; but warned her, as she valued his love, not to endeavour to behold his form. For some time Psyche was obedient to the injunction of her immortal spouse, and made no effort to gratify her natural curiosity; but, unfortunately, in the midst of her happiness she was seized with an unconquerable longing for the society of her sisters, and, in accordance with her desire, they were conducted by Zephyrus to her fairy-like abode. Filled with envy at the sight of her felicity, they poisoned her mind against her husband, and telling her that her unseen lover was a frightful monster, they gave her a sharp dagger, which they persuaded her to use for the purpose of delivering herself from his power.

After the departure of her sisters, Psyche resolved to take the first opportunity of following their malicious counsel. She accordingly rose in the dead of night, and taking a lamp in one hand and a dagger in the other, stealthily approached the couch where Eros was reposing, when, instead of the frightful monster she had expected to see, the beauteous form of the god of Love greeted her view. Overcome with surprise and admiration, Psyche stooped down to gaze more closely on his lovely features, when, from the lamp which she held in her trembling hand, there fell a drop of burning oil upon the shoulder of the sleeping god, who instantly awoke, and seeing Psyche standing over him with the instrument of death in her hand, sorrowfully reproached her for her treacherous designs, and, spreading out his wings, flew away.

In despair at having lost her lover, the unhappy Psyche endeavoured to put an end to her existence by throwing herself into the nearest river; but instead of closing over her, the waters bore her gently to the opposite bank, where Pan (the god of shepherds) received her, and consoled her with the hope of becoming eventually reconciled to her husband.

Meanwhile her wicked sisters, in expectation of meeting with the same good fortune which had befallen Psyche, placed themselves on the edge of the rock, but were both precipitated into the chasm below.

Psyche herself, filled with a restless yearning for her lost love, wandered all over the world in search of him. At length she appealed to Aphrodite to take compassion on her; but the goddess of Beauty, still jealous of her charms, imposed upon her the hardest tasks, the accomplishment of which often appeared impossible. In these she was always assisted by invisible, beneficent beings, sent to her by Eros, who still loved her, and continued to watch over her welfare.

Psyche had to undergo a long and severe penance before she became worthy to regain the happiness, which she had so foolishly trifled away. At last Aphrodite commanded her to descend into the under world, and obtain from Persephone a box containing all the charms of beauty. Psyche's courage now failed her, for she concluded that death must of necessity precede her entrance into the realm of shades. About to abandon herself to despair, she heard a voice which warned her of every danger to be avoided on her perilous journey, and instructed her with regard to certain precautions to be observed. These were as follows:—not to omit to provide herself with the ferryman's toll for Charon, and the cake to pacify Cerberus, also to refrain from taking any part in the banquets of Aïdes and Persephone, and, above all things, to bring the box of beauty charms unopened to Aphrodite. In conclusion, the voice assured her, that compliance with the above conditions would insure for her a safe return to the realms of light. But, alas, Psyche, who had implicitly followed all injunctions, could not withstand the temptation of the last condition; and, hardly had she quitted the lower world, when, unable to resist the curiosity which devoured her, she raised the lid of the box with eager expectation. But, instead of the wondrous charms of beauty which she expected to behold, there issued from the casket a dense black vapour, which had the effect of throwing her into a death-like sleep, out of which Eros, who had long hovered round her unseen, at length awoke her with the point of one of his golden arrows. He gently reproached her with this second proof of her curiosity and folly, and then, having persuaded Aphrodite to be reconciled to his beloved, he induced Zeus to admit her among the immortal gods.

Their reunion was celebrated amidst the rejoicings of all the Olympian deities. The Graces shed perfume on their path, the Hours sprinkled roses over the sky, Apollo added the music of his lyre, and the Muses united their voices in a glad chorus of delight.

This myth would appear to be an allegory, which signifies that the soul, before it can be reunited to its original divine essence, must be purified by the chastening sorrows and sufferings of its earthly career. The word Psyche signifies "butterfly," the emblem of the soul in ancient art.

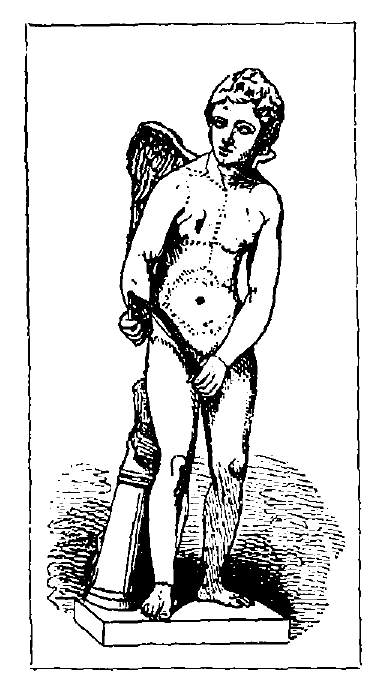

Eros is represented as a lovely boy, with rounded limbs, and a merry, roguish expression. He has golden wings, and a quiver slung over his shoulder, which contained his magical and unerring arrows; in one hand he bears his golden bow, and in the other a torch.

He is also frequently depicted riding on a lion, dolphin, or eagle, or seated in a chariot drawn by stags or wild boars, undoubtedly emblematical of the power of love as the subduer of all nature, even of the wild animals.

In Rome, Eros was worshipped under the name of Amor or Cupid.

HYMEN.

Hymen or Hymenæus, the son of Apollo and the muse Urania, was the god who presided over marriage and nuptial solemnities, and was hence invoked at all marriage festivities.

There is a myth concerning this divinity, which tells us that Hymen was a beautiful youth of very poor parents, who fell in love with a wealthy maiden, so far above him in rank, that he dared not cherish the hope of ever becoming united to her. Still he missed no opportunity of seeing her, and, upon one occasion, disguised himself as a girl, and joined a troop of maidens, who, in company with his beloved, were proceeding from Athens to Eleusis, in order to attend a festival of Demeter. On their way thither they were surprised by pirates, who carried them off to a desert island, where the ruffians, after drinking deeply, fell into a heavy sleep. Hymen, seizing the opportunity, slew them all, and then set sail for Athens, where he found the parents of the maidens in the greatest distress at their unaccountable disappearance. He comforted them with the assurance that their children should be restored to them, provided they would promise to give him in marriage the maiden he loved. The condition being gladly complied with, he at once returned to the island, and brought back the maidens in safety to Athens, whereupon he became united to the object of his love; and their union proved so remarkably happy, that henceforth the name of Hymen became synonymous with conjugal felicity.

IRIS (The Rainbow).

Iris, the daughter of Thaumas and Electra, personified the rainbow, and was the special attendant and messenger of the queen of heaven, whose commands she executed with singular tact, intelligence, and swiftness.

Most primitive nations have regarded the rainbow as a bridge of communication between heaven and earth, and this is doubtless the reason why Iris, who represented that beautiful phenomenon of nature, should have been invested by the Greeks with the office of communicating between gods and men.

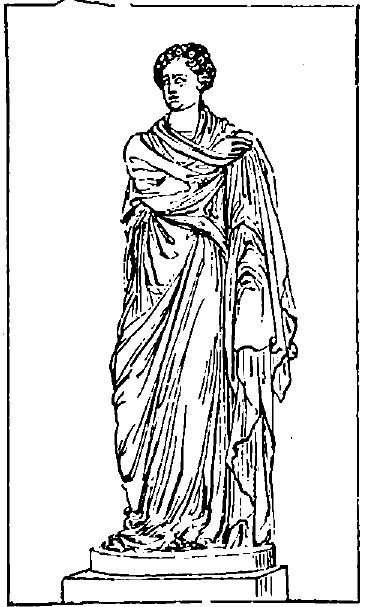

Iris is usually represented seated behind the chariot of Hera, ready to do the bidding of her royal mistress. She appears under the form of a slender maiden of great beauty, robed in an airy fabric of variegated hues, resembling mother-of-pearl; her sandals are bright as burnished silver, she has golden wings, and wherever she appears, a radiance of light, and a sweet odour, as of delicate spring flowers, pervades the air.

HEBE (Juventas).

Hebe was the personification of eternal youth under its most attractive and joyous aspect.

She was the daughter of Zeus and Hera, and though of such distinguished rank, is nevertheless represented as cup-bearer to the gods; a forcible exemplification of the old patriarchal custom, in accordance with which the daughters of the house, even when of the highest lineage, personally assisted in serving the guests.

Hebe is represented as a comely, modest maiden, small, of a beautifully rounded contour, with nut-brown tresses and sparkling eyes. She is often depicted pouring out nectar from an upraised vessel, or bearing in her hand a shallow dish, supposed to contain ambrosia, the ever youth-renewing food of the immortals.

In consequence of an act of awkwardness, which caused her to slip while serving the gods, Hebe was deprived of her office, which was henceforth delegated to Ganymedes, son of Tros.

Hebe afterwards became the bride of Heracles, when, after his apotheosis, he was received among the immortals.

JUVENTAS.

Juventas was the Roman divinity identified with Hebe, whose attributes, however, were regarded by the Romans as applying more particularly to the imperishable vigour and immortal glory of the state.

In Rome, several temples were erected in honour of this goddess.

GANYMEDES.

Ganymedes, the youngest son of Tros, king of Troy, was one day drawing water from a well on Mount Ida, when he was observed by Zeus, who, struck with his wonderful beauty, sent his eagle to transport him to Olympus, where he was endowed with immortality, and appointed cup-bearer to the gods.

Ganymedes is represented as a youth of exquisite beauty, with short golden locks, delicately chiselled features, beaming blue eyes, and pouting lips.

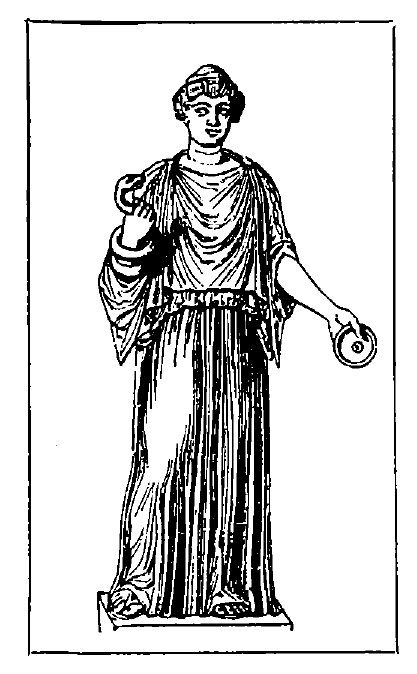

THE MUSES.

Of all the Olympic deities, none occupy a more distinguished position than the Muses, the nine beautiful daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne.

In their original signification, they presided merely over music, song, and dance; but with the progress of civilization the arts and sciences claimed their special presiding divinities, and we see these graceful creations, in later times, sharing among them various functions, such as poetry, astronomy, &c.

The Muses were honoured alike by mortals and immortals. In Olympus, where Apollo acted as their leader, no banquet or festivity was considered complete without their joy-inspiring presence, and on earth no social gathering was celebrated without libations being poured out to them; nor was any task involving intellectual effort ever undertaken, without earnestly supplicating their assistance. They endowed their chosen favourites with knowledge, wisdom, and understanding; they bestowed upon the orator the gift of eloquence, inspired the poet with his noblest thoughts, and the musician with his sweetest harmonies.

Like so many of the Greek divinities, however, the refined conception of the Muses is somewhat marred by the acerbity with which they punished any effort on the part of mortals to rival them in their divine powers. An instance of this is seen in the case of Thamyris, a Thracian bard, who presumed to invite them to a trial of skill in music. Having vanquished him, they not only afflicted him with blindness, but deprived him also of the power of song.

Another example of the manner in which the gods punished presumption and vanity is seen in the story of the daughters of King Pierus. Proud of the perfection to which they had brought their skill in music, they presumed to challenge the Muses themselves in the art over which they specially presided. The contest took place on Mount Helicon, and it is said that when the mortal maidens commenced their song, the sky became dark and misty, whereas when the Muses raised their heavenly voices, all nature seemed to rejoice, and Mount Helicon itself moved with exultation. The Pierides were signally defeated, and were transformed by the Muses into singing birds, as a punishment for having dared to challenge comparison with the immortals.

Undeterred by the above example, the Sirens also entered into a similar contest. The songs of the Muses were loyal and true, whilst those of the Sirens were the false and deceptive strains with which so many unfortunate mariners had been lured to their death. The Sirens were defeated by the Muses, and as a mark of humiliation, were deprived of the feathers with which their bodies were adorned.

The oldest seat of the worship of the Muses was Pieria in Thrace, where they were supposed to have first seen the light of day. Pieria is a district on one of the sloping declivities of Mount Olympus, whence a number of rivulets, as they flow towards the plains beneath, produce those sweet, soothing sounds, which may possibly have suggested this spot as a fitting home for the presiding divinities of song.

They dwelt on the summits of Mounts Helicon, Parnassus, and Pindus, and loved to haunt the springs and fountains which gushed forth amidst these rocky heights, all of which were sacred to them and to poetic inspiration. Aganippe and Hippocrene on Mount Helicon, and the Castalian spring on Mount Parnassus, were sacred to the Muses. The latter flowed between two lofty rocks above the city of Delphi, and in ancient times its waters were introduced into a square stone basin, where they were retained for the use of the Pythia and the priests of Apollo.

The libations to these divinities consisted of water, milk, and honey, but never of wine.

Their names and functions are as follows:—

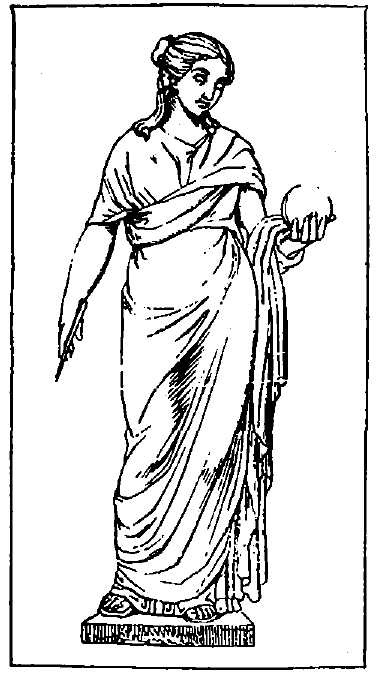

CALLIOPE, the most honoured of the Muses, presided over heroic song and epic poetry, and is represented with a pencil in her hand, and a slate upon her knee.

CLIO, the muse of History, holds in her hand a roll of parchment, and wears a wreath of laurel.

MELPOMENE, the muse of Tragedy, bears a tragic mask.

THALIA, the muse of Comedy, carries in her right hand a shepherd's crook, and has a comic mask beside her.

POLYHYMNIA, the muse of Sacred Hymns, is crowned with a wreath of laurel. She is always represented in a thoughtful attitude, and entirely enveloped in rich folds of drapery.

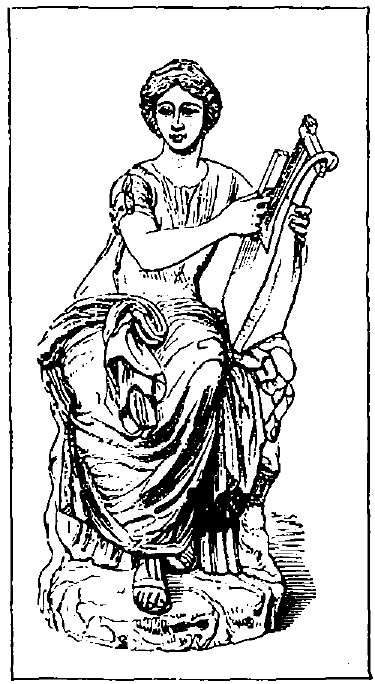

TERPSICHORE, the muse of Dance and Roundelay, is represented in the act of playing on a seven-stringed lyre.

URANIA, the muse of Astronomy, stands erect, and bears in her left hand a celestial globe.

EUTERPE, the muse of Harmony, is represented bearing a musical instrument, usually a flute.

ERATO, the muse of Love and hymeneal songs, wears a wreath of laurel, and is striking the chords of a lyre.

With regard to the origin of the Muses, it is said that they were created by Zeus in answer to a request on the part of the victorious deities, after the war with the Titans, that some special divinities should be called into existence, in order to commemorate in song the glorious deeds of the Olympian gods.

PEGASUS.

Pegasus was a beautiful winged horse who sprang from the body of Medusa when she was slain by the hero Perseus, the son of Zeus and Danaë. Spreading out his wings he immediately flew to the top of Mount Olympus, where he was received with delight and admiration by all the immortals. A place in his palace was assigned to him by Zeus, who employed him to carry his thunder and lightning. Pegasus permitted none but the gods to mount him, except in the case of Bellerophon, whom, at the command of Athene, he carried aloft, in order that he might slay the Chimæra with his arrows.

The later poets represent Pegasus as being at the service of the Muses, and for this reason he is more celebrated in modern times than in antiquity. He would appear to represent that poetical inspiration, which tends to develop man's higher nature, and causes the mind to soar heavenwards. The only mention by the ancients of Pegasus in connection with the Muses, is the story of his having produced with his hoofs, the famous fountain Hippocrene.

It is said that during their contest with the Pierides, the Muses played and sang on the summit of Mount Helicon with such extraordinary power and sweetness, that heaven and earth stood still to listen, whilst the mountain raised itself in joyous ecstasy towards the abode of the celestial gods. Poseidon, seeing his special function thus interfered with, sent Pegasus to check the boldness of the mountain, in daring to move without his permission. When Pegasus reached the summit, he stamped the ground with his hoofs, and out gushed the waters of Hippocrene, afterwards so renowned as the sacred fount, whence the Muses quaffed their richest draughts of inspiration.

THE HESPERIDES.

The Hesperides, the daughters of Atlas, dwelt in an island in the far west, whence they derived their name.

They were appointed by Hera to act as guardians to a tree bearing golden apples, which had been presented to her by Gæa on the occasion of her marriage with Zeus.

It is said that the Hesperides, being unable to withstand the temptation of tasting the golden fruit confided to their care, were deprived of their office, which was henceforth delegated to the terrible dragon Ladon, who now became the ever-watchful sentinel of these precious treasures.

The names of the Hesperides were Aegle, Arethusa, and Hesperia.

CHARITES (Gratiæ) GRACES.

All those gentler attributes which beautify and refine human existence were personified by the Greeks under the form of three lovely sisters, Euphrosyne, Aglaia, and Thalia, the daughters of Zeus and Eurynome (or, according to later writers, of Dionysus and Aphrodite).

They are represented as beautiful, slender maidens in the full bloom of youth, with hands and arms lovingly intertwined, and are either undraped, or wear a fleecy, transparent garment of an ethereal fabric.

They portray every gentle emotion of the heart, which vents itself in friendship and benevolence, and were believed to preside over those qualities which constitute grace, modesty, unconscious beauty, gentleness, kindliness, innocent joy, purity of mind and body, and eternal youth.

They not only possessed the most perfect beauty themselves, but also conferred this gift upon others. All the enjoyments of life were enhanced by their presence, and were deemed incomplete without them; and wherever joy or pleasure, grace and gaiety reigned, there they were supposed to be present.

Temples and altars were everywhere erected in their honour, and people of all ages and of every rank in life entreated their favour. Incense was burnt daily upon their altars, and at every banquet they were invoked, and a libation poured out to them, as they not only heightened all enjoyment, but also by their refining influence moderated the exciting effects of wine.

Music, eloquence, poetry, and art, though the direct work of the Muses, received at the hands of the Graces an additional touch of refinement and beauty; for which reason they are always regarded as the friends of the Muses, with whom they lived on Mount Olympus.

Their special function was to act, in conjunction with the Seasons, as attendants upon Aphrodite, whom they adorned with wreaths of flowers, and she emerges from their hands like the Queen of Spring, perfumed with the odour of roses and violets, and all sweet-scented blossoms.

The Graces are frequently seen in attendance on other divinities; thus they carry music for Apollo, myrtles for Aphrodite, &c., and frequently accompany the Muses, Eros, or Dionysus.

HORÆ (Seasons).

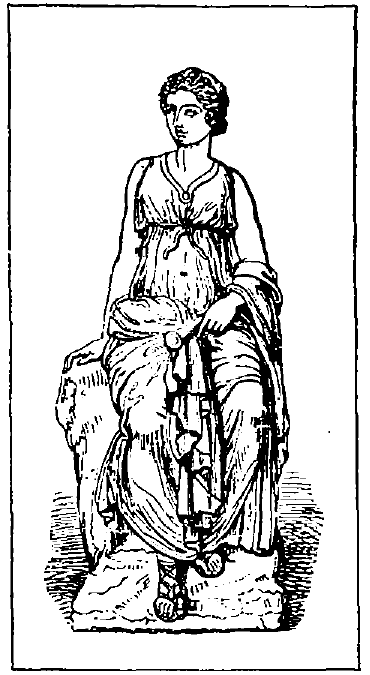

Closely allied to the Graces were the Horæ, or Seasons, who were also represented as three beautiful maidens, daughters of Zeus and Themis. Their names were Eunomia, Dice, and Irene.

It may appear strange that these divinities, presiding over the seasons, should be but three in number, but this is quite in accordance with the notions of the ancient Greeks, who only recognized spring, summer, and autumn as seasons; nature being supposed to be wrapt in death or slumber, during that cheerless and unproductive portion of the year which we call winter. In some parts of Greece there were but two Horæ, Thallo, goddess of the bloom, and Carpo, of the corn and fruit-bearing season.

The Horæ are always regarded as friendly towards mankind, and totally devoid of guile or subtlety; they are represented as joyous, but gentle maidens, crowned with flowers, and holding each other by the hand in a round dance. When they are depicted separately as personifications of the different seasons, the Hora representing spring appears laden with flowers, that of summer bears a sheaf of corn, whilst the personification of autumn has her hands filled with clusters of grapes and other fruits. They also appear in company with the Graces in the train of Aphrodite, and are seen with Apollo and the Muses.

They are inseparably connected with all that is good and beautiful in nature, and as the regular alternation of the seasons, like all her other operations, demands the most perfect order and regularity, the Horæ, being the daughters of Themis, came to be regarded as the representatives of order, and the just administration of human affairs in civilized communities. Each of these graceful maidens took upon herself a separate function: Eunomia presided more especially over state life, Dice guarded the interests of individuals, whilst Irene, the gayest and brightest of the three sisters, was the light-hearted companion of Dionysus.

The Horæ were also the deities of the fast-fleeting hours, and thus presided over the smaller, as well as the larger divisions of time. In this capacity they assist every morning in yoking the celestial horses to the glorious chariot of the sun, which they again help to unyoke when he sinks to rest.

In their original conception they were personifications of the clouds, and are described as opening and closing the gates of heaven, and causing fruits and flowers to spring forth, when they pour down upon them their refreshing and life-giving streams.

THE NYMPHS.

The graceful beings called the Nymphs were the presiding deities of the woods, grottoes, streams, meadows, &c.

These divinities were supposed to be beautiful maidens of fairy-like form, and robed in more or less shadowy garments. They were held in the greatest veneration, though, being minor divinities, they had no temples dedicated to them, but were worshipped in caves or grottoes, with libations of milk, honey, oil, &c.

They may be divided into three distinct classes, viz., water, mountain, and tree or wood nymphs.

WATER NYMPHS.

OCEANIDES, NEREIDES, AND NAIADES.

The worship of water-deities is common to most primitive nations. The streams, springs, and fountains of a country bear the same relation to it which the blood, coursing through the numberless arteries of a human being, bears to the body; both represent the living, moving, life-awakening element, without which existence would be impossible. Hence we find among most nations a deep feeling of attachment to the streams and waters of their native land, the remembrance of which, when absent in foreign climes, is always treasured with peculiar fondness. Thus among the early Greeks, each tribe came to regard the rivers and springs of its individual state as beneficent powers, which brought blessing and prosperity to the country. It is probable also that the charm which ever accompanies the sound of running water exercised its power over their imagination. They heard with delight the gentle whisper of the fountain, lulling the senses with its low, rippling tones; the soft purling of the brook as it rushes over the pebbles, or the mighty voice of the waterfall as it dashes on in its headlong course; and the beings which they pictured to themselves as presiding over all these charming sights and sounds of nature, corresponded, in their graceful appearance, with the scenes with which they were associated.

OCEANIDES.

The Oceanides, or Ocean Nymphs, were the daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, and, like most sea divinities, were endowed with the gift of prophecy.

They are personifications of those delicate vapour-like exhalations, which, in warm climates, are emitted from the surface of the sea, more especially at sunset, and are impelled forwards by the evening breeze. They are accordingly represented as misty, shadowy beings, with graceful swaying forms, and robed in pale blue, gauze-like fabrics.

THE NEREIDES.

The Nereides were the daughters of Nereus and Doris, and were nymphs of the Mediterranean Sea.

They are similar in appearance to the Oceanides, but their beauty is of a less shadowy order, and is more like that of mortals. They wear a flowing, pale green robe; their liquid eyes resemble, in their clear depths, the lucid waters of the sea they inhabit; their hair floats carelessly over their shoulders, and assumes the greenish tint of the water itself, which, far from deteriorating from their beauty, greatly adds to its effect. The Nereides either accompany the chariot of the mighty ruler of the sea, or follow in his train.

We are told by the poets that the lonely mariner watches the Nereides with silent awe and wondering delight, as they rise from their grotto-palaces in the deep, and dance, in joyful groups, over the sleeping waves. Some, with arms entwined, follow with their movements the melodies which seem to hover over the sea, whilst others scatter liquid gems around, these being emblematical of the phosphorescent light, so frequently observed at night by the traveller in southern waters.

The best known of the Nereides were Thetis, the wife of Peleus, Amphitrite, the spouse of Poseidon, and Galatea, the beloved of Acis.

THE NAIADES.

The Naiades were the nymphs of fresh-water springs, lakes, brooks, rivers, &c.

As the trees, plants, and flowers owed their nourishment to their genial, fostering care, these divinities were regarded by the Greeks as special benefactors to mankind. Like all the nymphs, they possessed the gift of prophecy, for which reason many of the springs and fountains over which they presided were believed to inspire mortals who drank of their waters with the power of foretelling future events. The Naiades are intimately connected in idea with those flowers which are called after them Nymphæ, or water-lilies, whose broad, green leaves and yellow cups float upon the surface of the water, as though proudly conscious of their own grace and beauty.

We often hear of the Naiades forming alliances with mortals, and also of their being wooed by the sylvan deities of the woods and dales.

DRYADES, OR TREE NYMPHS.

The tree nymphs partook of the distinguishing characteristics of the particular tree to whose life they were wedded, and were known collectively by the name of the Dryades.

The Hamadryades, or oak nymphs, represent in their peculiar individuality the quiet, self-reliant power which appears to belong essentially to the grand and lordly king of the forest.

The Birch Nymph is a melancholy maiden with floating hair, resembling the branches of the pale and fragile-looking tree which she inhabits.

The Beech Nymph is strong and sturdy, full of life and joyousness, and appears to give promise of faithful love and undisturbed repose, whilst her rosy cheeks, deep brown eyes, and graceful form bespeak health, vigour, and vitality.

The nymph of the Linden Tree is represented as a little coy maiden, whose short silver-gray dress reaches a little below the knee, and displays to advantage her delicately formed limbs. The sweet face, which is partly averted, reveals a pair of large blue eyes, which appear to look at you with wondering surprise and shy mistrust; her pale, golden hair is bound by the faintest streak of rose-coloured ribbon.

The tree nymph, being wedded to the life of the tree she inhabited, ceased to exist when it was either felled, or so injured as to wither away and die.

NYMPHS OF THE VALLEYS AND MOUNTAINS.

NAPÆÆ AND OREADES.

The Napææ were the kind and gentle nymphs of the valleys and glens who appear in the train of Artemis. They are represented as lovely maidens with short tunics, which, reaching only to the knee, do not impede their swift and graceful movements in the exercise of the chase. Their pale brown tresses are fastened in a knot at the back of the head, whence a few stray curls escape over their shoulders. The Napææ are shy as the fawns, and quite as frolicsome.

The Oreades, or mountain nymphs, who are the principal and constant companions of Artemis, are tall, graceful maidens, attired as huntresses. They are ardent followers of the chase, and spare neither the gentle deer nor the timid hare, nor indeed any animal they meet with in their rapid course. Wherever their wild hunt goes the shy Napææ are represented as hiding behind the leaves, whilst their favourites, the fawns, kneel tremblingly beside them, looking up beseechingly for protection from the wild huntresses; and even the bold Satyrs dart away at their approach, and seek safety in flight.

There is a myth connected with one of these mountain nymphs, the unfortunate Echo. She became enamoured of a beautiful youth named Narcissus, son of the river-god Cephissus, who, however, failed to return her love, which so grieved her that she gradually pined away, becoming a mere shadow of her former self, till, at length, nothing remained of her except her voice, which henceforth gave back, with unerring fidelity, every sound that was uttered in the hills and dales. Narcissus himself also met with an unhappy fate, for Aphrodite punished him by causing him to fall in love with his own image, which he beheld in a neighbouring fountain, whereupon, consumed with unrequited love, he wasted away, and was changed into the flower which bears his name.

The Limoniades, or meadow nymphs, resemble the Naiades, and are usually represented dancing hand in hand in a circle.

The Hyades, who in appearance are somewhat similar to the Oceanides, are cloudy divinities, and, from the fact of their being invariably accompanied by rain, are represented as incessantly weeping.

The Meliades were the nymphs who presided over fruit-trees.

Before concluding this subject, attention should be drawn to the fact that, in more modern times, this beautiful idea of animating all nature in detail reappears under the various local traditions extant in different countries. Thus do the Oceanides and Nereides live again in the mermaids, whose existence is still believed in by mariners, whilst the flower and meadow nymphs assume the shape of those tiny elves and fairies, who were formerly believed to hold their midnight revels in every wood and on every common; indeed, even at the present day, the Irish peasantry, especially in the west, firmly believe in the existence of the fairies, or "good people," as they are called.

THE WINDS.

According to the oldest accounts, Æolus was a king of the Æolian Islands, to whom Zeus gave the command of the winds, which he kept shut up in a deep cave, and which he freed at his pleasure, or at the command of the gods.

In later times the above belief underwent a change, and the winds came to be regarded as distinct divinities, whose aspect accorded with the respective winds with which they were identified. They were depicted as winged youths in full vigour in the act of flying through the air.

The principal winds were: Boreas (the north wind), Eurus (the east wind), Zephyrus (the west wind), and Notus (the south wind), who were said to be the children of Eos and Astræus.

There are no myths of interest connected with these divinities. Zephyrus was united to Chloris (Flora), the goddess of flowers. Of Boreas it is related that while flying over the river Ilissus, he beheld on the banks Oreithyia, the charming daughter of Erechtheus, king of Athens, whom he carried off to his native Thrace, and there made her his bride. Boreas and Oreithyia were the parents of Zetes and Calais, afterwards famous in the expedition of the Argonauts.

There was an altar erected at Athens in honour of Boreas, in commemoration of his having destroyed the Persian fleet sent to attack the Greeks.

On the Acropolis at Athens there was a celebrated octagonal temple, built by Pericles, which was dedicated to the winds, and on its sides were their various representations. The ruins of this temple are still to be seen.

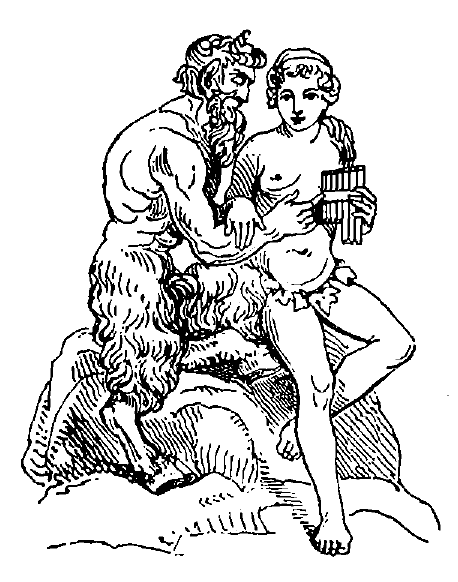

PAN (Faunus).

Pan was the god of fertility, and the special patron of shepherds and huntsmen; he presided over all rural occupations, was chief of the Satyrs, and head of all rural divinities.

According to the common belief, he was the son of Hermes and a wood nymph, and came into the world with horns sprouting from his forehead, a goat's beard and a crooked nose, pointed ears, and the tail and feet of a goat, and presented altogether so repulsive an appearance that, at the sight of him, his mother fled in dismay.

Hermes, however, took up his curious little offspring, wrapt him in a hare skin, and carried him in his arms to Olympus. The grotesque form and merry antics of the little stranger made him a great favourite with all the immortals, especially Dionysus; and they bestowed upon him the name of Pan (all), because he had delighted them all.

His favourite haunts were grottoes, and his delight was to wander in uncontrolled freedom over rocks and mountains, following his various pursuits, ever cheerful, and usually very noisy. He was a great lover of music, singing, dancing, and all pursuits which enhance the pleasures of life; and hence, in spite of his repulsive appearance, we see him surrounded with nymphs of the forests and dales, who love to dance round him to the cheerful music of his pipe, the syrinx. The myth concerning the origin of Pan's pipe is as follows:—Pan became enamoured of a beautiful nymph, called Syrinx, who, appalled at his terrible appearance, fled from the pertinacious attentions of her unwelcome suitor. He pursued her to the banks of the river Ladon, when, seeing his near approach, and feeling escape impossible, she called on the gods for assistance, who, in answer to her prayer, transformed her into a reed, just as Pan was about to seize her. Whilst the love-sick Pan was sighing and lamenting his unfortunate fate, the winds gently swayed the reeds, and produced a murmuring sound as of one complaining. Charmed with the soothing tones, he endeavoured to reproduce them himself, and after cutting seven of the reeds of unequal length, he joined them together, and succeeded in producing the pipe, which he called the syrinx, in memory of his lost love.

Pan was regarded by shepherds as their most valiant protector, who defended their flocks from the attacks of wolves. The shepherds of these early times, having no penfolds, were in the habit of gathering together their flocks in mountain caves, to protect them against the inclemency of the weather, and also to secure them at night against the attacks of wild animals; these caves, therefore, which were very numerous in the mountain districts of Arcadia, Bœotia, &c., were all consecrated to Pan.

As it is customary in all tropical climates to repose during the heat of the day, Pan is represented as greatly enjoying his afternoon sleep in the cool shelter of a tree or cave, and also as being highly displeased at any sound which disturbed his slumbers, for which reason the shepherds were always particularly careful to keep unbroken silence during these hours, whilst they themselves indulged in a quiet siesta.

Pan was equally beloved by huntsmen, being himself a great lover of the woods, which afforded to his cheerful and active disposition full scope, and in which he loved to range at will. He was regarded as the patron of the chase, and the rural sportsmen, returning from an unsuccessful day's sport, beat, in token of their displeasure, the wooden image of Pan, which always occupied a prominent place in their dwellings.

All sudden and unaccountable sounds which startle travellers in lonely spots, were attributed to Pan, who possessed a frightful and most discordant voice; hence the term panic terror, to indicate sudden fear. The Athenians ascribed their victory at Marathon to the alarm which he created among the Persians by his terrible voice.

Pan was gifted with the power of prophecy, which he is said to have imparted to Apollo, and he possessed a well-known and very ancient oracle in Arcadia, in which state he was more especially worshipped.

The artists of later times have somewhat toned down the original very unattractive conception of Pan, as above described, and merely represent him as a young man, hardened by the exposure to all weathers which a rural life involves, and bearing in his hand the shepherd's crook and syrinx—these being his usual attributes—whilst small horns project from his forehead. He is either undraped, or wears merely the light cloak called the chlamys.

The usual offerings to Pan were milk and honey in shepherds' bowls. Cows, lambs, and rams were also sacrificed to him.

After the introduction of Pan into the worship of Dionysus, we hear of a number of little Pans (Panisci), who are sometimes confounded with the Satyrs.

FAUNUS.

The Romans had an old Italian divinity called Faunus, who, as the god of shepherds, was identified with the Greek Pan, and represented in a similar manner.

Faunus is frequently called Inuus or the fertilizer, and Lupercus or the one who wards off wolves. Like Pan, he possessed the gift of prophecy, and was the presiding spirit of the woods and fields; he also shared with his Greek prototype the faculty of alarming travellers in solitary places. Bad dreams and evil apparitions were attributed to Faunus, and he was believed to enter houses stealthily at night for this purpose.

Fauna was the wife of Faunus, and participated in his functions.

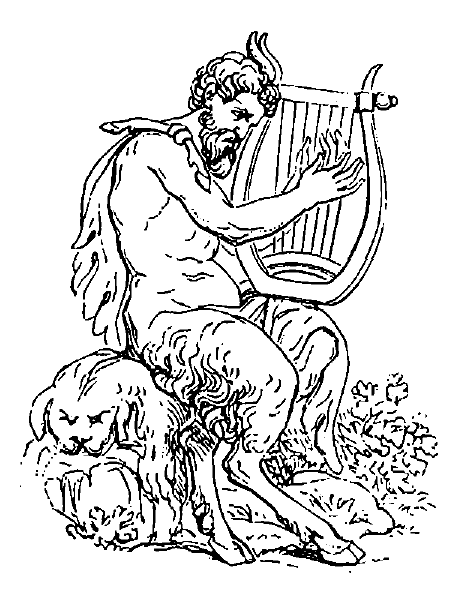

THE SATYRS.

The Satyrs were a race of woodland spirits, who evidently personified the free, wild, and untrammelled life of the forest. Their appearance was both grotesque and repulsive; they had flat broad noses, pointed ears, and little horns sprouting from their foreheads, a rough shaggy skin, and small goat's tails. They led a life of pleasure and self-indulgence, followed the chase, revelled in every description of wild music and dancing, were terrible wine-bibbers, and addicted to the deep slumbers which follow heavy potations. They were no less dreaded by mortals than by the gentle woodland nymphs, who always avoided their coarse rough sports.

The Satyrs were conspicuous figures in the train of Dionysus, and, as we have seen, Silenus their chief was tutor to the wine god. The older Satyrs were called Silens, and are represented in antique sculpture, as more nearly approaching the human form.

In addition to the ordinary Satyrs, artists delighted in depicting little Satyrs, young imps, frolicking about the woods in a marvellous variety of droll attitudes. These little fellows greatly resemble their friends and companions, the Panisci.

In rural districts it was customary for the shepherds and peasants who attended the festivals of Dionysus, to dress themselves in the skins of goats and other animals, and, under this disguise, they permitted themselves all kinds of playful tricks and excesses, to which circumstance the conception of the Satyrs is by some authorities attributed.

In Rome the old Italian wood-divinities, the FAUNS, who had goats' feet and all other characteristics of the Satyrs greatly exaggerated, were identified with them.

PRIAPUS.

Priapus, the son of Dionysus and Aphrodite, was regarded as the god of fruitfulness, the protector of flocks, sheep, goats, bees, the fruit of the vine, and all garden produce.

His statues, which were set up in gardens and vineyards, acted not only as objects of worship, but also as scarecrows, the appearance of this god being especially repulsive and unsightly. These statues were formed of wood or stone, and from the hips downwards were merely rude columns. They represent him as having a red and very ugly face; he bears in his hand a pruning knife, and his head is crowned with a wreath of vine and laurel. He usually carries fruit in his garments or a cornucopia in his hand, always, however, retaining his singularly revolting aspect. It is said that Hera, wishing to punish Aphrodite, sent her this misshapen and unsightly son, and that when he was born, his mother was so horrified at the sight of him, that she ordered him to be exposed on the mountains, where he was found by some shepherds, who, taking pity on him, saved his life.

This divinity was chiefly worshipped at Lampsacus, his birthplace. Asses were sacrificed to him, and he received the first-fruits of the fields and gardens, with a libation of milk and honey.

The worship of Priapus was introduced into Rome at the same time as that of Aphrodite, and was identified with a native Italian divinity named Mutunus.

ASCLEPIAS (Æsculapius).

Asclepias, the god of the healing art, was the son of Apollo and the nymph Coronis. He was educated by the noble Centaur Chiron, who instructed him in all knowledge, but more especially in that of the properties of herbs. Asclepias searched out the hidden powers of plants, and discovered cures for the various diseases which afflict the human body. He brought his art to such perfection, that he not only succeeded in warding off death, but also restored the dead to life. It was popularly believed that he was materially assisted in his wonderful cures by the blood of the Medusa, given to him by Pallas-Athene.

It is well to observe that the shrines of this divinity, which were usually built in healthy places, on hills outside the town, or near wells which were believed to have healing powers, offered at the same time means of cure for the sick and suffering, thus combining religious with sanitary influences. It was the custom for the sufferer to sleep in the temple, when, if he had been earnest in his devotions, Asclepias appeared to him in a dream, and revealed the means to be employed for the cure of his malady. On the walls of these temples were hung tablets, inscribed by the different pilgrims with the particulars of their maladies, the remedies practised, and the cures worked by the god:—a custom undoubtedly productive of most beneficial results.

Groves, temples, and altars were dedicated to Asclepias in many parts of Greece, but Epidaurus, the chief seat of his worship,—where, indeed, it is said to have originated,—contained his principal temple, which served at the same time as a hospital.

The statue of Asclepias in the temple at Epidaurus was formed of ivory and gold, and represented him as an old man with a full beard, leaning on a staff round which a serpent is climbing. The serpent was the distinguishing symbol of this divinity, partly because these reptiles were greatly used by the ancients in the cure of diseases, and partly also because all the prudence and wisdom of the serpent were deemed indispensable to the judicious physician.

His usual attributes are a staff, a bowl, a bunch of herbs, a pineapple, a dog, and a serpent.

His children inherited, for the most part, the distinguished talents of their father. Two of his sons, Machaon and Podalirius, accompanied Agamemnon to the Trojan war, in which expedition they became renowned, not only as military heroes, but also as skilful physicians.

Their sisters, HYGEIA (health), and PANACEA (all-healing), had temples dedicated to them, and received divine honours. The function of Hygeia was to maintain the health of the community, which great blessing was supposed to be brought by her as a direct and beneficent gift from the gods.

ÆSCULAPIUS.

The worship of Æsculapius was introduced into Rome from Epidaurus, whence the statue of the god of healing was brought at the time of a great pestilence. Grateful for their deliverance from this plague, the Romans erected a temple in his honour, on an island near the mouth of the Tiber.