Myths of Northern Lands

By H. A. Guerber

CHAPTER XXVI

THE SIGURD SAGA

The Beginning of the Story

While the first part of the Elder Edda consists of a collection of alliterative poems describing the creation of the world, the adventures of the gods, their eventual downfall, and gives a complete exposition of the Northern code of ethics, the second part comprises a series of heroic lays describing the life and adventures of the Volsung family, and especially of their chief representative, Sigurd, the great Northern warrior.

The Volsunga Saga

These lays form the basis of the great Scandinavian epic, the Volsunga Saga, and have supplied not only the materials for the Nibelungenlied, the German epic, and for countless folk tales, but also for Wagner's celebrated operas, "The Rhinegold," "Valkyr," "Siegfried," and "The Dusk of the Gods." They have also been rewritten by William Morris, the English poet, who has given them the form which they will probably retain in our literature, and it is from his work that almost all the quotations in this chapter are taken in preference to extracts from the Edda.

Sigi

Sigi, Odin's son, was a powerful man, and generally respected until he killed a man out of jealousy because the latter had slain the most game when they were out hunting together. In consequence of this crime, Sigi was driven from his own land and declared an outlaw. But, although he was a criminal, he had not entirely forfeited Odin's favor, for the god now gave him a well-equipped vessel, provided him with a number of brave followers, and promised that victory should ever attend him.

Thanks to Odin's protection, Sigi soon won the glorious empire of the Huns and became a powerful monarch. But when he had attained extreme old age his fortune changed, Odin suddenly forsook him, his wife's kindred fell upon him, and after a short encounter he was treacherously slain.

Rerir

His death was soon avenged, however, for his son Rerir, returning from a journey, put all the murderers to death and claimed the throne. But, in spite of all outward prosperity, Rerir's dearest wish, a son to succeed him, remained unfulfilled for many a year. Finally, however, Frigga decided to grant his constant prayer, and to vouchsafe the heir he longed for. Her swift messenger Gna, or Liod, was dispatched to carry him a miraculous apple, which she dropped into his lap as he was sitting alone on the hillside. Glancing upward, Rerir recognized the emissary of the goddess, and joyfully hastened home to partake of the apple with his wife. The child thus born in answer to their prayers was a handsome little lad called Volsung, who, losing both parents in early infancy, became ruler of all the land.

Volsung

Every year Volsung's wealth and power increased, and, as he was the boldest leader, many brave warriors rallied around him, and drank his mead sitting beneath the Branstock, a mighty oak, which, rising in the middle of his dwelling, pierced the roof and overshadowed the whole house.

"And as in all other matters 'twas all earthly houses' crown,

And the least of its wall-hung shields was a battle-world's renown,

So therein withal was a marvel and a glorious thing to see,

For amidst of its midmost hall-floor sprang up a mighty tree,

That reared its blessings roofward and wreathed the roof-tree dear

With the glory of the summer and the garland of the year."

Volsung did not long remain childless, for ten stalwart sons and one lovely daughter, Signy, came to brighten his home. As soon as this maiden reached marriageable years, many suitors asked for her hand, which was finally pledged to Siggeir, King of the Goths, whom, however, she had never seen.

The Wedding of Signy

The wedding day came, and when the bride first beheld her destined groom she shrank back in dismay, for his puny form and lowering glances contrasted oddly with her brothers' strong frames and frank faces. But it was too late to withdraw, - the family honor was at stake, - and Signy so successfully concealed her dislike that none except her twin brother Sigmund suspected how reluctantly she became Siggeir's wife.

The Sword in the Branstock

The wedding feast was held as usual, and when the merrymakings had reached their height the guests were startled by the sudden entrance of a tall, one-eyed man, closely enveloped in a mantle of cloudy blue. Without vouchsafing word or glance to any in the assembly, the stranger strode up to the Branstock and thrust a glittering sword up to the hilt in its great bole. Then, turning slowly around, he faced the awe-struck assembly, and in the midst of the general silence declared that the weapon would belong to the warrior who could pull it out, and that it would assure him victory in every battle. These words ended, he passed out and disappeared, leaving an intimate conviction in the minds of all the guests that Odin, king of the gods, had been in their midst.

"So sweet his speaking sounded, so wise his words did seem,

That moveless all men sat there, as in a happy dream

We stir not lest we waken; but there his speech had end,

And slowly down the hall-floor and outward did he wend;

And none would cast him a question or follow on his ways,

For they knew that the gift was Odin's, a sword for the world to praise."

Volsung was the first to recover the power of speech, and, waiving his own right to try to secure the divine weapon, he invited Siggeir to make the first attempt to draw it out of the tree-trunk. The bridegroom anxiously tugged and strained, but the sword remained firmly embedded in the oak. He resumed his seat, with an air of chagrin, and then Volsung also tried and failed. But the weapon was evidently not intended for either of them, and the young Volsung princes were next invited to try their strength.

"Sons I have gotten and cherished, now stand ye forth and try;

Lest Odin tell in God-home how from the way he strayed,

And how to the man he would not he gave away his blade."

Sigmund

The nine eldest sons were equally unsuccessful; but when Sigmund, the tenth and youngest, laid his firm young hand upon the hilt, it easily yielded to his touch, and he triumphantly drew the sword out without making the least exertion.

"At last by the side of the Branstock Sigmund the Volsung stood,

And with right hand wise in battle the precious sword-hilt caught,

Yet in a careless fashion, as he deemed it all for naught;

When, lo, from floor to rafter went up a shattering shout,

For aloft in the hand of Sigmund the naked blade showed out

As high o'er his head he shook it: for the sword had come away

From the grip of the heart of the Branstock, as though all loose it lay."

All present seemed overjoyed at his success; but Siggeir's heart was filled with envy, for he coveted the possession of the weapon, which he now tried to purchase from his young brother-in-law. Sigmund, however, refused to part with it at any price, declaring that the weapon had evidently been intended for him only. This refusal so offended Siggeir that he secretly resolved to bide his time, to exterminate the proud race of the Volsungs, and thus secure the divine sword.

Concealing his chagrin therefore, he turned to Volsung and cordially invited him to visit his court a month later, bringing all his sons and kinsmen with him. The invitation so spontaneously given was immediately accepted, and although Signy, suspecting evil, secretly sought her father while her husband slept, and implored him to retract his promise and stay at home, he would not consent to appear afraid.

Siggeir's Treachery

A few weeks after the return of the bridal couple Volsung's well-manned vessels came within sight of Siggeir's shores, and Signy perceiving them hastened down to the beach to implore her kinsmen not to land, warning them that her husband had treacherously planned an ambush, whence they could never escape alive. But Volsung and his sons, whom no peril could daunt, calmly bade her return to her husband's palace, and donning their arms they boldly set foot ashore.

"Then sweetly Volsung kissed her: 'Woe am I for thy sake,

But Earth the word hath hearkened, that yet unborn I spake;

How I ne'er would turn me backward from the sword or fire of bale; -

- I have held that word till to-day, and to-day shall I change the tale?

And look on these thy brethren, how goodly and great are they,

Wouldst thou have the maidens mock them, when this pain hath passed away

And they sit at the feast hereafter, that they feared the deadly stroke?

Let us do our day's work deftly for the praise and the glory of folk;

And if the Norns will have it that the Volsung kin shall fail,

Yet I know of the deed that dies not, and the name that shall ever avail.'"

Marching towards the palace, the brave little troop soon fell into Siggeir's ambuscade, and, although they fought with heroic courage, they were so overpowered by the superior number of their foes that Volsung was soon slain and all his sons made captive. Led bound into the presence of Siggeir, who had taken no part in the fight (for he was an arrant coward), Sigmund was forced to relinquish his precious sword, and he and his brothers were all condemned to die.

Signy, hearing this cruel sentence, vainly interceded for them, but all she could obtain by her prayers and entreaties was that her kinsmen should be chained to a fallen oak in the forest, there to perish of hunger and thirst if the wild beasts spared them. Then, fearing lest his wife should visit and succor her brothers, Siggeir confined her in the palace, where she was closely guarded night and day.

Early every morning Siggeir himself sent a messenger into the forest to see whether the Volsungs were still living, and every morning the man returned saying a monster had come during the night and had devoured one of the princes, leaving nothing but his bones. When none but Sigmund remained alive, Signy finally prevailed upon one of her servants to carry some honey into the forest and smear it over her brother's face and mouth.

That very night the wild beast, attracted by the smell of the honey, licked Sigmund's face, and even thrust its tongue into his mouth. Clinching his teeth upon it, Sigmund, weak and wounded as he was, struggled until his bonds broke and he could slay the nightly visitor who had caused the death of all his brothers. Then he vanished into the forest, where he remained concealed until the daily messenger had come and gone, and until Signy, released from captivity, came speeding to the forest to weep over her kinsmen's remains.

Seeing her evident grief, and knowing she had no part in Siggeir's cruelty, Sigmund stole out of his place of concealment, comforted her as best he could, helped her to bury the whitening bones, and registered a solemn oath in her presence to avenge his family's wrongs. This vow was fully approved by Signy, who, however, bade her brother abide a favorable time, promising to send him a helper. Then the brother and sister sadly parted, she to return to her distasteful palace home, and he to seek the most remote part of the forest, where he built a tiny hut and plied the trade of a smith.

"And men say that Signy wept

When she left that last of her kindred; yet wept she never more

Amid the earls of Siggeir, and as lovely as before

Was her face to all men's deeming: nor aught it changed for ruth,

Nor for fear nor any longing; and no man said for sooth

That she ever laughed thereafter till the day of her death was come."

Signy's Sons

Years passed by. Siggeir, having taken possession of the Volsung kingdom, proudly watched the growth of his eldest son, whom Signy secretly sent to her brother as soon as he was ten years of age, bidding Sigmund train the child up to help him, if he were worthy of such a task. Sigmund reluctantly accepted the charge; but as soon as he had tested the boy and found him deficient in physical courage, he either sent him back to his mother, or, as some versions relate, slew him.

Some time after this Sigmund tested Signy's second son, who had been sent to him for the same purpose, and found him wanting also. Evidently none but a pure-blooded Volsung could help him in his work of revenge, and Signy, realizing this, resolved to commit a crime.

"And once in the dark she murmured: 'Where then was the ancient song

That the Gods were but twin-born once, and deemed it nothing wrong

To mingle for the world's sake, whence had the Æsir birth,

And the Vanir, and the Dwarf-kind, and all the folk of earth?'"

This resolution taken, she summoned a beautiful young witch, exchanged forms with her, and, running into the forest, sought shelter in Sigmund's hut. Deeming her nothing but the gypsy she seemed, and won by her coquetry, he soon made her his wife. Three days later she vanished from his hut, returned to the palace, resumed her own form, and when she gave birth to a little son, she rejoiced to see his bold glance and strong frame.

Sinfiotli

When this child, Sinfiotli, was ten years of age, she herself made a preliminary test of his courage by sewing his garment to his skin. Then she suddenly snatched it off with shreds of flesh hanging to it, and as the child did not even wince, but laughed aloud, she confidently sent him to Sigmund. He, too, found the boy quite fearless, and upon leaving the hut one day he bade him take meal from a certain sack, and knead and bake the bread. On returning home Sigmund asked Sinfiotli whether his orders had been carried out. The lad replied by showing the bread, and when closely questioned he artlessly confessed that he had been obliged to knead into the loaf a great adder which was hidden in the meal. Pleased to see that the child, for whom he felt a strange affection, had successfully stood the test which had daunted his predecessors, Sigmund bade him refrain from eating of that loaf, as he alone could taste poison unharmed, and patiently began to teach him all a Northern warrior need know.

"For here the tale of the elders doth men a marvel to wit,

That such was the shaping of Sigmund among all earthly kings,

That unhurt he handled adders and other deadly things,

And might drink unscathed of venom: but Sinfiotli was so wrought

That no sting of creeping creatures would harm his body aught."

The Werewolves

Sigmund and Sinfiotli soon became inseparable companions, and while ranging the forest together they once came to a hut, where they found two men sound asleep. Wolfskins hanging near them immediately made them conclude that the strangers were werewolves (men whom a cruel spell forced to assume the habits and guise of ravenous wolves, and who could only resume their natural form for a short space at a time). Prompted by curiosity, Sigmund donned one of the wolf skins, Sinfiotli the other, and they were soon metamorphosed into wolves and rushed through the forest, slaying and devouring all they saw.

Such were their wolfish passions that they soon attacked each other, and after a fierce struggle Sinfiotli, the younger and weaker, fell down dead. This sudden catastrophe brought Sigmund to his senses. While he hung over his murdered companion in sudden despair, he saw two weasels come out of the forest and fight until one lay dead. The live weasel then sprang back into the thicket, and soon returned with a leaf, which it laid upon its companion's breast. At the contact of the magic herb the dead beast came back to life. A moment later a raven flying overhead dropped a similar leaf at Sigmund's feet, and he, understanding that the gods wished to help him, laid it upon Sinfiotli, who was restored to life.

Afraid lest they might work each other further mischief while in this altered guise, Sigmund and Sinfiotli now crept home and patiently waited until the time of release had come. On the ninth night the skins dropped off and they hastily flung them into the fire, where they were entirely consumed, and the spell was broken forever.

It was now that Sigmund confided the story of his wrongs to Sinfiotli, who swore that, although Siggeir was his father (for neither he nor Sigmund knew the secret of his birth), he would help him to take his revenge. At nightfall, therefore, he accompanied Sigmund to the palace; they entered unseen, and concealed themselves in the cellar, behind the huge beer vats. Here they were discovered by Signy's two youngest children, who were playing with golden rings, which rolled into the cellar, and who thus suddenly came upon the men in ambush.

They loudly proclaimed the discovery they had just made to their father and his guests, but, before Siggeir and his men could don their arms, Signy caught both children by the hand, and dragging them into the cellar bade her brother slay the little traitors. This Sigmund utterly refused to do, but Sinfiotli struck off their heads ere he turned to fight against the assailants, who were rapidly closing around him.

In spite of all efforts Sigmund and his brave young companion soon fell into the hands of the Goths, whose king, Siggeir, sentenced them to be buried alive in the same mound, a stone partition being erected between them so they could neither see nor touch each other. The prisoners were already confined in their living graves, and the men were about to place the last stones on the roof, when Signy drew near, bearing a bundle of straw, which they allowed her to throw at Sinfiotli's feet, for they fancied that it contained only a few provisions which would prolong his agony a little without helping him to escape.

When the workmen had departed and all was still, Sinfiotli undid the sheaf and shouted for joy when he found instead of bread the sword which Odin had given to Sigmund. Knowing that nothing could dull or break the keen edge of this fine weapon, Sinfiotli thrust it through the stone partition, and, aided by Sigmund, sawed an opening, and both soon effected an escape through the roof.

"Then in the grave-mound's darkness did Sigmund the king upstand,

And unto that saw of battle he set his naked hand;

And hard the gift of Odin home to their breasts they drew;

Sawed Sigmund, sawed Sinfiotli, till the stone was cleft atwo,

And they met and kissed together: then they hewed and heaved full hard

Till, lo, through the bursten rafters the winter heavens bestarred!

And they leap out merry-hearted; nor is there need to say

A many words between them of whither was the way."

Sigmund's Vengeance

Sigmund and Sinfiotli, free once more, noiselessly sought the palace, piled combustible materials around it, and setting fire to it placed themselves on either side the door, declaring that none but the women should be allowed to pass through. Then they loudly called to Signy to escape ere it was too late, but she had no desire to live, and after kissing them both and revealing the secret of Sinfiotli's birth she sprang back into the flames, where she perished.

"And then King Siggeir's roof-tree upheaved for its utmost fall,

And its huge walls clashed together, and its mean and lowly things

The fire of death confounded with the tokens of the kings."

Helgi

The long-planned vengeance had finally been carried out, Volsung's death had been avenged, and Sigmund, feeling that nothing now detained him in Gothland, set sail with Sinfiotli and returned to Hunaland, where he was warmly welcomed and again sat under the shade of his ancestral tree, the mighty Branstock. His authority fully established, Sigmund married Borghild, a beautiful princess, who bore him two sons, Hamond and Helgi, the latter of whom was visited by the Norns when he lay in his cradle, and promised sumptuous entertainment in Valhalla when his earthly career should be ended.

"And the woman was fair and lovely, and bore him sons of fame;

Men called them Hamond and Helgi, and when Helgi first saw light

There came the Norns to his cradle and gave him life full bright,

And called him Sunlit Hill, Sharp Sword, and Land of Rings,

And bade him be lovely and great, and a joy in the tale of kings."

This young Volsung prince was fostered by Hagal, for Northern kings generally entrusted their sons' education to a stranger, thinking they would be treated with less indulgence than at home. Under this tuition Helgi became so fearless that at the age of fifteen he ventured alone into the palace of Hunding, with whose whole race his family was at feud. Passing all through the palace unmolested and unrecognized, he left an insolent message, which so angered Hunding that he immediately set out in pursuit of the bold young prince. Hunding entered Hagal's house, and would have made Helgi a prisoner had the youth not disguised himself as a servant maid, and begun to grind corn as if it were his wonted occupation. The invaders marveled somewhat at the maid's tall stature and brawny arms, but departed without suspecting that they had been so near the hero whom they sought.

Having thus cleverly escaped, Helgi joined Sinfiotli; they collected an army, and marched openly against the Hundings, with whom they fought a great battle, during which the Valkyrs hovered overhead, waiting to convey the slain to Valhalla. Gudrun, one of the battle maidens, was so charmed by the courage which Helgi displayed, that she openly sought him and promised to be his wife. Only one of the Hunding race, Dag, remained alive, and he was allowed to go free after promising never to try to avenge his kinsmen's death. This promise was not kept, however, for Dag, having borrowed Odin's spear Gungnir, treacherously made use of it to slay Helgi. Gudrun, now his wife, wept many tears at his death, and solemnly cursed his murderer; then, hearing from one of her maids that her slain husband kept calling for her in the depths of his tomb, she fearlessly entered the mound at night and tenderly inquired why he called and why his wounds kept on bleeding even after death. Helgi answered that he could not rest happy because of her grief, and declared that for every tear she shed a drop of his blood must flow.

"Thou weepest, gold-adorned!

Cruel tears,

Sun-bright daughter of the south!

Ere to sleep thou goest;

Each one falls bloody

On the prince's breast,

Wet, cold, and piercing,

With sorrow big."

SÆMUND'S EDDA (Thorpe's tr.)

To still her beloved husband's sufferings, Gudrun then ceased to weep, but her spirit soon joined his, which had ridden over Bifrost and entered Valhalla, where Odin made him leader of the Einheriar. Here Gudrun, a Valkyr once more, continued to wait upon him, darting down to earth at Odin's command to seek new recruits for the army which her lord was to lead into battle when Ragnarok, the twilight of the gods, should come.

The Death of Sinfiotli

Sinfiotli, Sigmund's eldest son, also came to an early death; for, having quarreled with and slain Borghild's brother, she determined to poison him. Twice Sinfiotli detected the attempt and told his father there was poison in his cup. Twice Sigmund, whom no venom could injure, drained the bowl; but when Borghild made a third and last attempt, he bade Sinfiotli let the wine flow through his beard. Mistaking the meaning of his father's words, Sinfiotli immediately drained the cup and fell to the ground lifeless, for the poison was of the most deadly kind.

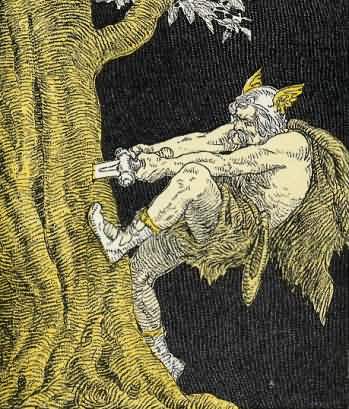

Odin taking the dead Sinfjötli to Valhalla. Image from the Wikimedia Commons

"He drank as he spake the words, and forthwith the venom ran

In a chill flood over his heart, and down fell the mighty man

With never an uttered death-word and never a death-changed look,

And the floor of the hall of the Volsungs beneath his falling shook.

Then up rose the elder of days with a great and bitter cry,

And lifted the head of the fallen; and none durst come anigh

To hearken the words of his sorrow, if any words he said

But such as the Father of all men might speak over Balder dead.

And again, as before the death-stroke, waxed the hall of the Volsungs dim,

And once more he seemed in the forest, where he spake with naught but him."

Speechless with grief, Sigmund tenderly raised his son's body in his arms, and strode out of the hall and down to the shore, where he deposited his precious burden in the skiff of an old one-eyed boatman who came at his call. But when he would fain have stepped aboard also, the boatman pushed off and was soon lost to sight. The bereaved father then slowly wended his way home again, knowing that Odin himself had come to claim the young hero and had rowed away with him "out into the west."

Hiords

Sigmund repudiated Borghild in punishment for this crime, and when he was very old indeed he sued for the hand of Hiordis, a fair young princess, daughter of Eglimi, King of the Islands. Although this young maiden had many suitors, among others King Lygni of Hunding's race, she gladly accepted Sigmund and became his wife. Lygni, the discarded suitor, was so angry at this decision, that he immediately collected an army and marched against his successful rival, who, overpowered by superior numbers, fought with the courage of despair.

Hidden in a neighboring thicket, Hiordis and her maid anxiously watched the battle, saw Sigmund pile the dead around him and triumph over every foe, until at last a tall, one-eyed warrior suddenly appeared, broke his matchless sword, and vanished, leaving him defenseless amid the foe, who soon cut him down.

"But, lo! through the hedge of the war-shafts, a mighty man there came,

One-eyed and seeming ancient, but his visage shone like flame:

Gleaming gray was his kirtle, and his hood was cloudy blue;

And he bore a mighty twi-bill, as he waded the fight-sheaves through,

And stood face to face with Sigmund, and upheaved the bill to smite.

Once more round the head of the Volsung fierce glittered the Branstock's light,

The sword that came from Odin: and Sigmund's cry once more

Rang out to the very heavens above the din of war.

Then clashed the meeting edges with Sigmund's latest stroke,

And in shivering shards fell earthward that fear of worldly folk.

But changed were the eyes of Sigmund, the war-wrath left his face;

For that gray-clad, mighty Helper was gone, and in his place

Drave on the unbroken spear-wood 'gainst the Volsung's empty hands:

And there they smote down Sigmund, the wonder of all lands,

On the foemen, on the death-heap his deeds had piled that day."

All the Volsung race and army had already succumbed, so Lygni immediately left the battlefield to hasten on and take possession of the kingdom and palace, where he fully expected to find the fair Hiordis and force her to become his wife. As soon as he had gone, however, the beautiful young queen crept out of her hiding place in the thicket, ran to the dying Sigmund, caught him to her breast in a last passionate embrace, and tearfully listened to his dying words. He then bade her gather up the fragments of his sword, carefully treasure them, and give them to the son whom he foretold would soon be born, and who was destined to avenge his death and be far greater than he.

"'I have wrought for the Volsungs truly, and yet have I known full well

That a better one than I am shall bear the tale to tell:

And for him shall these shards be smithied; and he shall be my son,

To remember what I have forgotten and to do what I left undone.'"

Elf, the Viking

While Hiordis was mourning over Sigmund's lifeless body, her watching handmaiden warned her of the approach of a party of vikings. Retreating into the thicket once more, Hiordis exchanged garments with her; then, bidding her walk first and personate the queen, they went to meet the viking Elf (Helfrat or Helferich), and so excited his admiration for Sigmund that he buried him with all pomp, and promised them a safe asylum in his house.

As he had doubted their relative positions from the very first moment, he soon resorted to a seemingly idle question to ascertain their real rank. The pretended queen, when asked how she knew the hour had come for rising when the winter days were short and there was no light to announce the coming of morn, replied that, as she was in the habit of drinking milk ere she fed the cows, she always awoke thirsty. But when the same question was put to the real Hiordis, she answered that she knew it was morning because the golden ring her father had given her grew cold on her hand.

Sigurd

Elf, having thus discovered the true state of affairs, offered marriage to the pretended handmaiden, Hiordis, promising to foster her child by Sigmund - a promise which he nobly kept. The child was sprinkled with water by his hand - a ceremony which our pagan ancestors scrupulously performed - received from him the name of Sigurd, and grew up in the palace. There he was treated as the king's own son, receiving his education from Regin, the wisest of men, who knew all things and was even aware of his own fate, which was to fall by a youth's hand.

"Again in the house of the Helper there dwelt a certain man,

Beardless and low of stature, of visage pinched and wan:

So exceeding old was Regin, that no son of man could tell

In what year of the days passed over he came to that land to dwell

But the youth of king Elf had he fostered, and the Helper's youth thereto,

Yea, and his father's father's: the lore of all men he knew,

And was deft in every cunning, save the dealings of the sword:

So sweet was his tongue-speech fashioned, that men trowed his every word;

His hand with the harp-strings blended was the mingler of delight

With the latter days of sorrow; all tales he told aright;

The Master of the Masters in the smithying craft was he;

And he dealt with the wind and the weather and the stilling of the sea;

Nor might any learn him leech-craft, for before that race was made,

And that man-folk's generation, all their life-days had he weighed."

Under this tutor young Sigurd grew up to great wisdom. He mastered the smith craft, and the art of carving all manner of runes, learned languages, music, and eloquence, and, last but not least, became a doughty warrior whom none could subdue. By Regin's advice, Sigurd, having reached manhood, asked the king for a war horse - a request which was immediately granted, for he was bidden hasten to Gripir, the stud-keeper, and choose from his flock the steed he liked best.

On his way to the meadow where the horses were at pasture, Sigurd encountered a one-eyed stranger, clad in gray and blue, who bade him drive the horses into the river and select the one which could breast the foaming tide most successfully.

Sigurd, acting according to this advice, noticed that one horse, after crossing, raced around the meadow on the opposite side; then, plunging back into the river, he returned to his former pasture without showing any signs of fatigue. The young hero selected this horse, therefore, calling him Grane or Greyfell. This steed was a descendant of Odin's eight-footed horse Sleipnir, and, besides being unusually strong and indefatigable, was as fearless as his master. A short time after this, while Regin and his pupil were sitting over the fire, the former struck his harp, and, after the manner of the Northern scalds, sang or recited the following tale, which was the story of his life:

The Treasure of the Dwarf King

Hreidmar, king of the dwarf folk, was the father of three sons. Fafnir, the eldest, was gifted with a fearless soul and a powerful hand; Otter, the second, with snare and net, and the power of changing form at will; and Regin, the third, could, as we have already seen, command all knowledge and skillfully ply the trade of a smith. To please the avaricious old Hreidmar, this youngest son fashioned for him a house which was all lined with glittering gold and flashing gems, and guarded by Fafnir, whose fierce glances and Ægis helmet none dared encounter.

Now it came to pass that Odin, Hoenir, and Loki once came down upon earth in human guise for one of their wonted expeditions to test the hearts of men, and soon reached the land where Hreidmar dwelt.

"And the three were the heart-wise Odin, the Father of the Slain,

And Loki, the World's Begrudger, who maketh all labor vain,

And Honir, the Utter-Blameless, who wrought the hope of man,

And his heart and inmost yearnings, when first the work began; -

The God that was aforetime, and hereafter yet shall be

When the new light yet undreamed of shall shine o'er earth and sea."

These gods had not wandered very far before Loki perceived an otter basking in the sun. Animated by his usual spirit of destruction, he slew the unoffending beast - which, as it happened, was the dwarf king's second son, Otter - and flung its lifeless body over his shoulders, thinking it would furnish a good dish when meal time came.

Following his companions, Loki came at last to Hreidmar's house, entered with them, and flung his burden down upon the floor. The moment the dwarf king's glance fell upon it he flew into a towering rage, and before the gods could help themselves they were bound by his order, and heard him declare that they should never recover their liberty unless they could satisfy his thirst for gold by giving him enough of that precious substance to cover the otterskin inside and out.

"'Now hearken the doom I shall speak! Ye stranger-folk shall be free

When ye give me the Flame of the Waters, the gathered Gold of the Sea,

That Andvari hideth rejoicing in the wan realm pale as the grave;

And the Master of Sleight shall fetch it, and the hand that never gave,

And the heart that begrudgeth forever, shall gather and give and rue.

Lo, this is the doom of the wise, and no doom shall be spoken anew.'"

As this otterskin had the property of stretching itself out to a fabulous size, no ordinary treasure could suffice to cover it. The gods therefore bade Loki, who was liberated to procure the ransom, hasten off to the waterfall where the dwarf Andvari dwelt, and secure the treasure he had amassed by magical means.

"There is a desert of dread in the uttermost part of the world,

Where over a wall of mountains is a mighty water hurled,

Whose hidden head none knoweth, nor where it meeteth the sea;

And that force is the Force of Andvari, and an Elf of the dark is he.

In the cloud and the desert he dwelleth amid that land alone;

And his work is the storing of treasure within his house of stone."

In spite of diligent search, however, Loki could not find the dwarf; but perceiving a salmon sporting in the foaming waters, he shrewdly concluded the dwarf must have assumed this shape, and borrowing Ran's net he soon had the fish in his power. As he had suspected, it was Andvari, who, in exchange for liberty, reluctantly brought forth his mighty treasure and surrendered it all, including the Helmet of Dread and a hauberk of gold, reserving only the ring he wore, which was gifted with miraculous powers, and, like a magnet, helped him to collect the precious ore. But the greedy Loki, catching sight of it, wrenched it away from him and departed laughing, while the dwarf hurled angry curses after him, declaring that the ring would ever prove its possessor's bane and would cause the death of many.

"That gold

Which the dwarf possessed

Shall to two brothers

Be cause of death,

And to eight princes,

Of dissension.

From my wealth no one

Shall good derive."

SÆMUND'S EDDA (Thorpe's tr.)

On arriving at Hreidmar's hut, Loki found the mighty treasure none too great, for the skin widened and spread, and he was even forced to give the ring Andvaranaut (Andvari's loom) to purchase his and his companions' release. The gold thus obtained soon became a curse, as Andvari had predicted, for Fafnir and Regin both coveted a share. As for Hreidmar, he gloated over his treasure night and day, and Fafnir the invincible, seeing that he could not obtain it otherwise, slew his own father, donned the Helmet of Dread and the hauberk of gold, grasped the sword Hrotti, and when Regin came to claim a part drove him scornfully out into the world, where he bade him earn his own living.

Thus exiled, Regin took refuge among men, to whom he taught the arts of sowing and reaping. He showed them how to work metals, sail the seas, tame horses, yoke beasts of burden, build houses, spin, weave, and sew - in short, all the industries of civilized life, which had hitherto been unknown. Years elapsed, and Regin patiently bided his time, hoping that some day he would find a hero strong enough to avenge his wrongs upon Fafnir, whom years of gloating over his treasure had changed into a horrible dragon, the terror of Gnitaheid (Glittering Heath), where he had taken up his abode.

His story finished, Regin suddenly turned to the attentive Sigurd, told him he knew that he could slay the dragon if he wished, and inquired whether he were ready to help his old tutor avenge his wrongs.

"And he spake: 'Hast thou hearkened, Sigurd? Wilt thou help a man that is old

To avenge him for his father? Wilt thou win that treasure of gold

And be more than the kings of the earth? Wilt thou rid the earth of a wrong

And heal the woe and the sorrow my heart hath endured o'er long?'"

Sigurd's Sword

Sigurd immediately assented, declaring, however, that the curse must be assumed by Regin, for he would have none of it; and, in order to be well prepared for the coming fight, he asked his master to forge him a sword which no blow could break. Twice Regin fashioned a marvelous weapon, but twice Sigurd broke it to pieces on the anvil. Then, declaring that he must have a sword which would not fail him in time of need, he begged the broken fragments of Sigmund's weapon from his mother Hiordis, and either forged himself or made Regin forge a matchless blade, whose temper was such that it neatly severed some wool floating gently down the stream, and divided the great anvil in two without being even dinted.

After paying a farewell visit to Gripir, who, knowing the future, foretold every event in his coming career, Sigurd took leave of his mother, and accompanied by Regin set sail from his native land, promising to slay the dragon as soon as he had fulfilled his first duty, which was to avenge his father Sigmund's death.

"'First wilt thou, prince,

Avenge thy father,

And for the wrongs of Eglymi

Wilt retaliate.

Thou wilt the cruel,

The sons of Hunding,

Boldly lay low:

Thou wilt have victory.'"

LAY OF SIGURD FAFNICIDE (Thorpe's tr.)

On his way to the Volsung land Sigurd saw a. man walking on the waters, and took him on board, little suspecting that this individual, who said his name was Feng or Fiollnir, was Odin or Hnikar, the wave stiller. He therefore conversed freely with the stranger, who promised him favorable winds, and learned from him how to distinguish auspicious from unauspicious omens.

The Fight with the Dragon

After slaying Lygni and cutting the bloody eagle on his foes, Sigurd left his reconquered kingdom and went with Regin to slay Fafnir. A long ride through the mountains, which rose higher and higher before him, brought him at last to his goal, where a one-eyed stranger bade him dig trenches in the middle of the track along which the dragon daily rolled his slimy length to go down to the river and quench his thirst. He then bade Sigurd cower in one of those holes, and there wait until the monster passed over him, when he could drive his trusty weapon straight into its heart.

Sigurd gratefully followed this advice, and as the monster's loathsome, slimy folds rolled overhead he thrust his sword under its left breast, and, deluged with blood, sprang out of the trench as the dragon rolled aside in the throes of death.

"Then all sank into silence, and the son of Sigmund stood

On the torn and furrowed desert by the pool of Fafnir's blood,

And the serpent lay before him, dead, chilly, dull, and gray;

And over the Glittering Heath fair shone the sun and the day,

And a light wind followed the sun and breathed o'er the fateful place,

As fresh as it furrows the sea plain, or bows the acres' face."

Regin, who had prudently remained at a distance until all danger was over, seeing his foe was slain, now came up to Sigurd; and fearing lest the strong young conqueror should glory in his deed and claim a reward, he began to accuse him of having murdered his kin, and declared that instead of requiring life for life, as was his right according to Northern law, he would consider it sufficient atonement if Sigurd would cut out the monster's heart and roast it for him on a spit.

"Then Regin spake to Sigurd: 'Of this slaying wilt thou be free?

Then gather thou fire together and roast the heart for me,

That I may eat it and live, and be thy master and more;

For therein was might and wisdom, and the grudged and hoarded lore:

Or else depart on thy ways afraid from the Glittering Heath.'"

Sigurd, knowing that a true warrior never refused satisfaction of some kind to the kindred of the slain, immediately prepared to act as cook, while Regin dozed until the meat was ready. Feeling of the heart to ascertain whether it were tender, Sigurd burned his fingers so severely that he instinctively thrust them into his mouth to allay the smart. No sooner had Fafnir's blood touched his lips than he discovered, to his utter surprise, that, he could understand the songs of the birds, which were already gathering around the carrion. Listening to them attentively, he found they were advising him to slay Regin, appropriate the gold, eat the heart and drink the blood of the dragon; and as this advice entirely coincided with his own wishes, he lost no time in executing it. A small portion of Fafnir's heart was reserved for future consumption, ere he wandered off in search of the mighty hoard. Then, after donning the Helmet of Dread, the hauberk of gold, and the ring Andvaranaut, and loading Greyfell with as much ruddy gold as he could carry, Sigurd sprang on his horse, listening eagerly to the birds' songs to know what he had best undertake next.

The Sleeping Warrior Maiden

Soon he heard them sing of a warrior maiden fast asleep on a mountain and all surrounded by a glittering barrier of flames, through which only the bravest of men could pass in order to arouse her.

"On the fell I know

A warrior maid to sleep;

Over her waves

The linden's bane:

Ygg whilom stuck

A sleep-thorn in the robe

Of the maid who

Would heroes choose."

LAY OF FAFNIR (Thorpe's tr.)

After riding for a long while through trackless regions, Sigurd at last came to the Hindarfiall in Frankland, a tall mountain whose cloud-wreathed summit seemed circled by fiery flames.

"Long Sigurd rideth the waste, when, lo! on a morning of day,

From out of the tangled crag walls, amidst the cloudland gray,

Comes up a mighty mountain, and it is as though there burns

A torch amidst of its cloud wreath; so thither Sigurd turns,

For he deems indeed from its topmost to look on the best of the earth;

And Greyfell neigheth beneath him, and his heart is full of mirth."

Riding straight up this mountain, lie saw the light grow more and more vivid, and soon a barrier of lurid flames stood before him; but although the fire crackled and roared, it could not daunt our hero, who plunged bravely into its very midst.

"Now Sigurd turns in his saddle, and the hilt of the Wrath he shifts,

And draws a girth the tighter; then the gathered reins he lifts,

And crieth aloud to Greyfell, and rides at the wildfire's heart;

But the white wall wavers before him and the flame-flood rusheth apart,

And high o'er his head it riseth, and wide and wild its roar

As it beareth the mighty tidings to the very heavenly floor:

But he rideth through its roaring as the warrior rides the rye,

When it bows with the wind of the summer and the hid spears draw anigh;

The white flame licks his raiment and sweeps through Greyfell's mane,

And bathes both hands of Sigurd and the hilt of Fafnir's bane,

And winds about his war-helm and mingles with his hair,

But naught his raiment dusketh or dims his glittering gear;

Then it fails and fades and darkens till all seems left behind,

And dawn and the blaze is swallowed in mid-mirk stark and blind."

No sooner had Sigurd thus fearlessly sprung into the very heart of the flames than the fire flickered and died out, leaving nothing but a broad circle of white ashes, through which lie rode until he came to a great castle, with shield-hung walls, in which he penetrated unchallenged, for the gates were wide open and no warders or men at arms were to be seen. Proceeding cautiously, for he feared some snare, Sigurd at last came to the center of the inclosure, where he saw a recumbent form all cased in armor. To remove the helmet was but a moment's work, but Sigurd started back in surprise when he beheld, instead of a warrior, the sleeping face of a most beautiful woman.

All his efforts to awaken her were quite vain, however, until he had cut the armor off her body, and she lay before him in pure-white linen garments, her long golden hair rippling and waving around her. As the last fastening of her armor gave way, she opened wide her beautiful eyes, gazed in rapture upon the rising sun, and after greeting it with enthusiasm she turned to her deliverer, whom she loved at first sight, as he loved her.

"Then she turned and gazed on Sigurd, and her eyes met the Volsung's eyes.

And mighty and measureless now did the tide of his love arise,

For their longing had met and mingled, and he knew of her heart that she loved,

And she spake unto nothing but him, and her lips with the speechflood moved."

The maiden now proceeded to inform Sigurd that she was Brunhild, according to some authorities the daughter of an earthly king. Odin had raised her to the rank of a Valkyr, in which capacity she had served him faithfully for a long while. But once she had ventured to set her own wishes above his, and, instead of leaving the victory to the old king for whom he had designated it, had favored his younger and therefore more attractive opponent.

In punishment for this act of disobedience, she was deprived of her office and banished to earth, where Allfather decreed she must marry like any other member of her sex. This sentence filled Brunhild's heart with dismay, for she greatly feared lest it might be her fate to mate with a coward, whom she would despise. To quiet these apprehensions, Odin placed her on Hindarfiall or Hindfell, stung her with the Thorn of Sleep, that she might await in unchanged youth and beauty the coming of her destined husband and surrounded her with a barrier of flame which none but the bravest would venture to pass through.

From the top of the Hindarfiall, Brunhild now pointed out to Sigurd her former home, at Lymdale or Hunaland, telling him he would find her there whenever he chose to come and claim her as his wife; and then, while they stood on the lonely mountain top together, Sigurd placed the ring Andvaranaut upon her hand, in sign of betrothal, swearing to love her alone as long as life endured.

"From his hand then draweth Sigurd Andvari's ancient Gold;

There is naught but the sky above them as the ring together they hold,

The shapen-ancient token, that hath no change nor end,

No change, and no beginning, no flaw for God to mend

Then Sigurd cries: 'O Brynhild, now hearken while I swear

That the sun shall die in the heavens and the day no more be fair,

If I seek not love in Lymdale and the house that fostered thee,

And the land where thou awakedst'twixt the woodland and the sea!

And she cried: 'O Sigurd, Sigurd, now hearken while I swear

That the day shall die forever and the sun to blackness wear,

Ere I forget thee, Sigurd, as I lie 'twixt wood and sea

In the little land of Lymdale and the house that fostered me!'"

The Fostering of Aslaug

According to some authorities, after thus plighting

their troth the lovers parted; according to others, Sigurd soon

sought out and married Brunhild, with whom he lived for a while

in perfect happiness, until forced to leave her and his infant

daughter Aslaug.

According to some authorities, after thus plighting

their troth the lovers parted; according to others, Sigurd soon

sought out and married Brunhild, with whom he lived for a while

in perfect happiness, until forced to leave her and his infant

daughter Aslaug.

This child, left orphaned at three years of age, was fostered by Brunhild's father, who, driven away from home, concealed her in a cunningly fashioned harp, until reaching a distant land he was murdered by a peasant couple for the sake of the gold they supposed it to contain.

Their surprise and disappointment were great indeed when, on breaking the instrument open, they found a beautiful little girl, whom they deemed mute, as she would not speak a word. Time passed on, and the child, whom they had trained to do all their labor, grew up to be a beautiful maiden who won the affections of a passing viking, Ragnar Lodbrog, King of the Danes, to whom she told her tale. After a year's probation, during which he won glory in many lands, he came back and married her.

"She heard a voice she deemed well known,

Long waited through dull hours bygone,

And round her mighty arms were cast:

But when her trembling red lips passed

From out the heaven of that dear kiss,

And eyes met eyes, she saw in his

Fresh pride, fresh hope, fresh love, and saw

The long sweet days still onward draw,

Themselves still going hand in hand,

As now they went adown the strand."

THE FOSTERING OF ASLAUG

(William Morris)

The story of Sigurd and Brunhild did not end on the Hindarfial, however, for the hero soon went to seek adventures in the great world, where he had vowed, in true knightly fashion, to right the wrong and defend the fatherless and oppressed.

The Niblungs

In the course of his wanderings, Sigurd finally came to the land of the Niblungs, the land of continual mist, where Giuki and Grimhild were king and queen. The latter was specially powerful, as she was well versed in magic lore and could not only weave spells and mutter incantations, but could also concoct marvelous potions which would steep the drinker in temporary forgetfulness and make him yield to whatever she wished.

The Niblung king was father of three sons, Gunnar, Högni, and Guttorm, who were brave young men, and of one daughter, Gudrun, the gentlest as well as the most beautiful of maidens. Sigurd was warmly welcomed by Giuki, and invited to tarry awhile. He accepted the invitation, shared all the pleasures and occupations of the Niblungs, even accompanying them to war, where he distinguished himself by his valor, and so won the admiration of Grimhild that she resolved to secure him as her daughter's husband at any price. She therefore brewed one of her magic potions, which she bade Gudrun give him, and when he had partaken of it, he utterly forgot Brunhild and his plighted troth, and gazed upon Gudrun with an admiration which by the queen's machinations was soon changed to ardent love.

"But the heart was changed in Sigurd; as though it ne'er had been

His love of Brynhild perished as he gazed on the Niblung Queen:

Brynhild's beloved body was e'en as a wasted hearth,

No more for bale or blessing, for plenty or for dearth."

Although haunted by a vague dread that he had forgotten something important, Sigurd asked for and obtained Gudrun's hand, and celebrated his wedding amid the rejoicings of the people, who loved him very dearly. He gave his bride some of Fafnir's heart to eat, and the moment she had tasted it her nature was changed, and she began to grow cold and silent to all except him. Sigurd further cemented his alliance with the eldest two Giukings (as the sons of Giuki were called) by stepping down into the doom ring with them, cutting out a sod which was placed upon a shield, beneath which they stood while they bared and slightly cut their right arms, and allowing their blood to mingle in the fresh earth, over which the sod was again laid after they had sworn eternal friendship.

But although Sigurd loved his wife and felt true brotherly affection for her brothers, he could not get rid of his haunting sense of oppression, and was seldom seen to smile as radiantly as of old. Giuki having died, Grimhild besought Gunnar, his successor, to take a wife, suggesting that none seemed more worthy to become Queen of the Niblungs than Brunhild, who, it was reported, sat in a golden hall surrounded by flames, whence she had declared she would issue only to marry the warrior who would dare pass through the fire to her side.

Gunnar's Stratagem

Gunnar immediately prepared to seek this bride, and strengthened by one of his mother's magic potions, and encouraged by Sigurd, who accompanied him, he felt very confident of success. But when he would daringly have ridden straight into the fire, his steed drew back affrighted and he could not induce him to advance a step. Seeing that Greyfell did not flinch, he asked him of Sigurd; but although the steed allowed Gunnar to mount, he would not stir unless his master were on his back. Gunnar, disappointed, sprang to earth and accepted Sigurd's proposal to assume his face and form, ride through the flames, and woo the bride by proxy. This deception could easily be carried out, thanks to the Helmet of Dread, and to a magic potion which Grimhild had given Gunnar.

The transformation having been brought about, Greyfell bounded through the flames with his master, and bore him to the palace door, where he dismounted, and entering the large hall came into the presence of Brunhild, whom he failed to recognize, owing to Grimhild's spell. Brunhild started back in dismay when she saw the dark-haired knight, for she had deemed it utterly impossible for any but Sigurd to cross the flames, and she, too, did not know her lover in his altered guise.

Reluctantly she rose from her seat to receive him, and as she had bound herself by a solemn oath to accept as husband the man who braved the flames, she allowed him to take his lawful place by her side. Sigurd silently approached, carefully laid his drawn sword between them, and satisfied Brunhild's curiosity concerning this singular behavior by telling her that the gods had bidden him celebrate his wedding thus.

"There they went in one bed together; but the foster-brother laid

'Twixt him and the body of Brynhild his bright blue battle-blade,

And she looked and heeded it nothing; but, e'en as the dead folk lie,

With folded hands she lay there, and let the night go by:

And as still lay that image of Gunnar as the dead of life forlorn,

And hand on hand he folded as he waited for the morn.

So oft in the moonlit minster your fathers may ye see

By the side of the ancient mothers await the day to be."

Three days passed thus, and when the fourth morning dawned, Sigurd drew the ring Andvaranaut from Brunhild's hand, replaced it by another, and received her solemn promise that in ten days' time she would appear at the Niblung court to take up her duties as queen and be a faithful wife.

"I thank thee, King, for thy goodwill, and thy pledge of love I take.

Depart with my troth to thy people: but ere full ten days are o'er

I shall come to the Sons of the Niblungs, and then shall we part no more

Till the day of the change of our life-days, when Odin and Freya shall call."

Then Sigurd again passed out of the palace through the ashes lying white and cold, and joined Gunnar, with whom he hastened to exchange forms once more, after he had reported the success of his venture. The warriors rode homeward together, and Sigurd revealed only to Gudrun the secret of her brother's wooing, giving her the fatal ring, which he little suspected would be the cause of many woes.

True to her promise, Brunhild appeared ten days later, solemnly blessed the house she was about to enter, greeted Gunnar kindly, and allowed him to conduct her to the great hall, where she saw Sigurd seated beside Gudrun. He looked up at the selfsame moment, and as he encountered Brunhild's reproachful glance Grimhild's spell was broken and he was struck by an anguished recollection of the happy past. It was too late, however: they were both in honor bound, he to Gudrun and she to Gunnar, whom she passively followed to the high seat, where she sat beside him listening to the songs of the bards.

But, although apparently calm, Brunhild's heart was hot with anger, and she silently nursed her wrath, often stealing out of her husband's palace to wander alone in the forest, where she could give vent to her grief.

In the mean while, Gunnar, seeing his wife so coldly indifferent to all his protestations of affection, began to have jealous suspicions and wondered whether Sigurd had honestly told the whole story of the wooing, and whether he had not taken advantage of his position to win Brunhild's love. Sigurd alone continued the even tenor of his way, doing good to all, fighting none but tyrants and oppressors, and cheering all he met by his kindly words and smile.

The Quarrel of the Queens

One day the queens went down to the Rhine to bathe, and as they were entering the water Gudrun claimed precedence by right of her husband's courage. Brunhild refused to yield what she deemed her right, and a quarrel ensued, in the course of which Gudrun accused her sister-in-law of infidelity, producing the ring Andvaranaut in support of her charge. Crushed by this revelation, Brunhild hastened home. ward, and lay on her bed in speechless grief day after day, until all thought she would die. In vain did Gunnar and all the members of the royal family seek her in turn and implore her to speak; she would not utter a word until Sigurd came and inquired the cause of her great grief. Like a long-pent-up stream, her love and anger now burst forth, and she overwhelmed the hero with reproaches, until his heart swelled with grief for her sorrow and burst the tight bands of his strong armor.

"Out went Sigurd

From that interview

Into the hall of kings,

Writhing with anguish;

So that began to start

The ardent warrior's

Iron-woven sark

Off from his sides."

SÆMUND'S EDDA

(Thorpe's tr.)

But although he even offered to repudiate Gudrun to reinstate her in her former rights, she refused to listen to his words, and dismissed him, saying that she must never prove faithless to Gunnar. Her pride was such, however, that she could not endure the thought that two living men had called her wife, and the next time her husband sought her presence she implored him to put Sigurd to death, thus increasing his jealousy and suspicions. He refused to grant this prayer because he had sworn good fellowship with Sigurd, and she prevailed upon Hogni to work her will. As he, too, did not wish to violate his oath, he induced Guttorm, by means of much persuasion and one of Grimhild's potions, to do the dastardly deed.

Death of Sigurd

In the dead of night, Guttorm stole into Sigurd's chamber, sword in hand; but as he bent over the bed he saw Sigurd's bright eyes fixed upon him, and fled precipitately. Later on he returned and the same scene was repeated; but towards morning, when he stole in for the third time, he found the hero asleep and traitorously drove his spear through his back.

Mortally wounded, Sigurd raised himself in bed, grasped his wonderful sword hanging beside him, flung it full at the flying murderer, and cut him in two just as he reached the door. His last remaining strength thus exhausted, Sigurd sank back, whispered a last farewell to the terrified Gudrun, and breathed his last.

"'Mourn not, O Gudrun, this stroke is the last of ill;

Fear leaveth the house of the Niblungs on this breaking of the morn;

Mayest thou live, O woman beloved, unforsaken, unforlorn!

It is Brynhild's deed,' he murmured, 'and the woman that loves me well;

Naught now is left to repent of, and the tale abides to tell.

I have done many deeds in my life-days; and all these, and my love they lie

In the hollow hand of Odin till the day of the world go by.

I have done and I may not undo, I have given and I take not again

Art thou other than I, Allfather, wilt thou gather my glory in vain?'"

Sigurd's infant son was also slain, and poor Gudrun mourned aver her dead in speechless, tearless grief; while Brunhild laughed aloud, thereby incurring the wrath of Gunnar, who repented now, but too late, of his share in the dastardly crime.

While the assembled people were erecting a mighty funeral pyre - which they decorated with precious hangings, fresh flowers, and glittering arms, as was the custom for the burial of a prince - Gudrun was surrounded by women, who, seeing her tearless anguish, and fearing lest her heart would break if her tears did not flow, began to recount the bitterest sorrows they had known, one even telling of the loss of all she held dear. But their attempts to make her weep were utterly vain, until they laid her husband's head in her lap, bidding her kiss him as if he were still alive; then her tears began to flow in torrents.

The reaction soon set in for Brunhild also; her resentment was all forgotten when she saw Sigurd laid on the pyre in all his martial array, with the burnished armor, the Helmet of Dread, and the trappings of his horse, which was to be burned with him, as well as several of his faithful servants who could not survive his loss. She withdrew to her apartment, distributed all her wealth among her handmaidens, donned her richest array, and stretching herself out upon her bed stabbed herself.

In dying accents she then bade Gunnar lay her beside the hero she loved, with the glittering, unsheathed sword between them, as it had lain when he had wooed her by proxy. When she had breathed her last, these orders were punctually executed, and both bodies were burned amid the lamentations of all the Niblungs.

"They are gone - the lovely, the mighty, the hope of the ancient Earth

It shall labor and bear the burden as before that day of their birth

It shall groan in its blind abiding for the day that Sigurd bath sped,

And the hour that Brynhild bath hastened, and the dawn that waketh the dead

It shall yearn, and be oft-times holpen, and forget their deeds no more,

Till the new sun beams on Balder and the happy sealess shore."

According to another version of the story, Sigurd was treacherously slain by the Giukings while hunting in the forest, and his body was borne home by the hunters and laid at his wife's feet.

Gudrun, still inconsolable, and loathing the kindred who had thus treacherously robbed her of all her joy, fled from her father's house and took refuge with Elf, Sigurd's foster father, who, after Hiordis's death, had married Thora, the daughter of King Hakon. The two women became great friends, and here Gudrun tarried several years, working tapestry in which she embroidered the great deeds of Sigurd, and watching over her little daughter Swanhild, whose bright eyes reminded her so vividly of the husband whom she had lost.

Atli, King of the Huns

In the mean while, Atli, Brunhild's brother, who was now King of the Huns, had sent to Gunnar to demand atonement for his sister's death; and to satisfy these claims Gunnar had promised that in due time he would give him Gudrun's hand in marriage. Time passed, and when at last Atli clamored for the fulfillment of his promise, the Niblung brothers, with their mother Grimhild, went to seek the long-absent Gudrun, and by their persuasions and the magic potion administered by Grimhild succeeded in persuading her to leave little Swanhild in Denmark and become Atli's wife.

Gudrun dwelt, year after year, in the land of the Huns, secretly hating her husband, whose avaricious tendencies were extremely repugnant to her; and she was not even consoled for Sigurd's death and Swanhild's loss by the birth of two sons, Erp and Eitel. As she lovingly thought of the past she often spoke of it, little suspecting that her descriptions of the wealth of the Niblungs excited Atli's greed, and that he was secretly planning some pretext for getting it into his power.

Finally he decided to send Knefrud or Wingi, one of his subjects, to invite all the Niblung princes to visit his court, intending to slay them when he should have them at his mercy; but Gudrun, fathoming this design, sent a runic-written warning to her brothers, together with the ring Andvaranaut, around which she had twined a wolf's hair. On the way, however, the messenger partly effaced the runes, thus changing their meaning; and when he appeared before the Niblungs, Gunnar accepted the invitation, in spite of Hogni's and Grimhild's warnings and the ominous dream of his new wife Glaumvor.

Burial of the Niblung Treasure

Before his departure, however, they prevailed upon him to secretly bury the great Niblung hoard in the Rhine, where it was sunk in a deep hole, the position of which was known to the royal brothers only, and which they took a solemn oath never to reveal.

"Down then and whirling outward the ruddy Gold fell forth,

As a flame in the dim gray morning flashed out a kingdom's worth;

Then the waters roared above it, the wan water and the foam

Flew up o'er the face of the rock-wall as the tinkling Gold fell home,

Unheard, unseen forever, a wonder and a tale,

Till the last of earthly singers from the sons of men shall fail."

The Treachery of Atli

In martial array they then rode out of the city of the Niblungs, which they were never again to see, and after many unimportant adventures came into the land of the Huns, where, on reaching Atli's hall and finding themselves surrounded by foes, they slew the traitor Knefrud, and prepared to sell their lives as dearly as possible.

Gudrun rushed to meet them, embraced them tenderly, and, seeing that they must fight, grasped a weapon and loyally helped them in the terrible massacre which ensued. When the first onslaught was over, Gunnar kept up the spirits of his followers by playing on his harp, which he laid aside only to grasp his sword and make havoc among the foe. Thrice the brave Niblungs resisted the assault of the Huns ere, wounded, faint, and weary, Gunnar and Högni, now sole survivors, fell into the hands of their foes, who bound them securely and led them off to prison to await death.

Atli, who had prudently abstained from taking any active part in the fight, had his brothers-in-law brought in turn before him, promising freedom if they would only reveal the hiding place of the golden hoard; but they proudly kept silence, and it was only after much torture that Gunnar acknowledged that he had sworn a solemn oath never to reveal the secret as long as Högni lived, and declared he would believe his brother dead only when his heart was brought to him on a platter.

"With a dreadful voice cried Gunnar: 'O fool, hast thou heard it told

Who won the Treasure aforetime and the ruddy rings of the Gold?

It was Sigurd, child of the Volsungs, the best sprung forth from the best:

He rode from the North and the mountains, and became my summer guest,

My friend and my brother sworn: he rode the Wavering Fire,

And won me the Queen of Glory and accomplished my desire;

The praise of the world he was, the hope of the biders in wrong,

The help of the lowly people, the hammer of the strong:

Ah! oft in the world, henceforward, shall the tale be told of the deed,

And I, e'en I, will tell it in the day of the Niblungs' Need:

For I sat night-long in my armor, and when light was wide o'er the land

I slaughtered Sigurd my brother, and looked on the work of mine hand.

And now, O mighty Atli, I have seen the Niblung's wreck,

And the feet of the faint-heart dastard have trodden Gunnar's neck;

And if all be little enough, and the Gods begrudge me rest,

Let me see the heart of Högni cut quick from his living breast

And laid on the dish before me: and then shall I tell of the Gold,

And become thy servant, Atli, and my life at thy pleasure hold.'"

Urged by greed, Atli immediately ordered that Högni's heart should be brought; but his servants, fearing to lay hands on such a grim warrior, slew the cowardly scullion Hialli. This trembling heart called forth contemptuous words from Gunnar, who declared such a timorous organ could never have belonged to his fearless brother. But when, in answer to a second angry command from Atli, the unquivering heart of Högni was really brought, Gunnar recognized it, and turning to the monarch solemnly swore that since the secret now rested with him alone it would never be revealed.

The Last of the Niblungs

Livid with anger, the king bade him be thrown, with bound hands, into a den of venomous snakes, where, his harp having been flung after him in derision, Gunnar calmly sat, playing it with his toes, and lulling all the reptiles to sleep save one only. This snake was said to be Atli's mother in disguise, and it finally bit him in the side, silencing his triumphant song forever.

To celebrate the death of his foes, Atli ordered a great feast, commanding Gudrun to be present to wait upon him. Then he heartily ate and drank, little suspecting that his wife had slain both his sons, and was serving up their roasted hearts and their blood mixed with wine in cups made of their skulls. When the king and his men were intoxicated, Gudrun, according to one version of the story, set fire to the palace, and when the drunken sleepers awoke, too late to escape, she revealed all she had done, stabbed her husband, and perished in the flames with the Huns. According to another version, however, she murdered Atli with Sigurd's sword, placed his body on a ship, which she sent adrift, and then cast herself into the sea, where she was drowned.

"She spread out her arms as she spake it, and away from the earth she leapt

And cut off her tide of returning; for the sea-waves over her swept,

And their will is her will henceforward, and who knoweth the deeps of the sea,

And the wealth of the bed of Gudrun, and the days that yet shall be?"

A third and very different version reports that Gudrun was not drowned, but was borne along by the waves to the land where Jonakur was king. There she became his wife, and the mother of three sons, Sörli, Hamdir, and Erp. She also recovered possession of her beloved daughter Swanhild, who, in the mean while, had grown into a beautiful maiden of marriageable age.

Swanhild

Swanhild was finally promised to Ermenrich, King of Gothland, who sent his son, Randwer, and one of his subjects, Sibich, to escort the bride to his kingdom. Sibich, who was a traitor, and had planned to compass the death of the royal family that he might claim the kingdom, accused Randwer of having tried to win his young stepmother's affections, and thereby so roused the anger of Ermenrich that he ordered his son to be hanged, and Swanhild to be trampled to death under the feet of wild horses. But such was the beauty of this daughter of Sigurd and Gudrun that even the wild steeds could not be urged to touch her until she had been hidden from their view under a great blanket, when they trod her to death under their cruel hoofs.

Gudrun, hearing of this, called her three sons to her side, and provided them with armor and weapons against which nothing but stone could prevail. Then, after bidding them depart and avenge their murdered sister, she died of grief, and was burned on a great pyre. The three youths, Sörli, Hamdir, and Erp, invaded Ermenrich's kingdom, but the two eldest, deeming Erp too young to assist them, taunted him with his small size, and finally slew him. They then attacked Ermenrich, cut off his hands and feet, and would have slain him had not a one-eyed stranger suddenly appeared and bidden the bystanders throw stones at the young invaders. His orders were immediately carried out, and Sörli and Hamdir both fell under the shower of stones, which alone had power to injure them according to Gudrun's words.

"Ye have heard of Sigurd aforetime, how the foes of God he slew;

How forth from the darksome desert the Gold of the Waters he drew;

How he wakened Love on the Mountain, and wakened Brynhild the Bright,

And dwelt upon Earth for a season, and shone in all men's sight.

Ye have heard of the Cloudy People, and the dimming of the day,

And the latter world's confusion, and Sigurd gone away;

Now ye know of the Need of the Niblungs and the end of broken troth,

All the death of kings and of kindreds and the Sorrow of Odin the Goth."

Interpretation of the Saga

This story of the Volsungs is supposed by some authorities to be a series of sun myths, in which Sigi, Rerir, Volsung, Sigmund, and Sigurd in turn personify the glowing orb of day. They are all armed with invincible swords, the sunbeams, and all travel through the world fighting against their foes, the demons of cold and darkness. Sigurd, like Balder, is beloved of all; he marries Brunhild, the dawn maiden, whom he finds in the midst of flames, the flush of morn, and parts from her only to find her again when his career is ended. His body is burned on the funeral pyre, which, like Balder's, represents either the setting sun or the last gleam of summer, of which he too is a type. The slaying of Fafnir is the destruction of the demon of cold or darkness, who has stolen the golden hoard of summer or the yellow rays of the sun.

According to other authorities this Saga is based upon history. Atli is the cruel Attila, the "Scourge of God," while Gunnar is Gundicarius, a Burgundian monarch, whose kingdom was destroyed by the Huns, and who was slain with his brothers in 451. Gudrun is the Burgundian princess Ildico, who slew her husband on her wedding night, as has already been related, using the glittering blade which had once belonged to the sun-god to avenge her murdered kinsmen.