|

|

The Lost Land Of King Arthur By J. Cuming Walters

CHAPTER III

OF ARTHUR THE KING AND MERLIN THE ENCHANTER

" No matter whence we do derive our name,

All Brittany shall ring of Merlin's fame,

And wonder at his Arts." The Birth of Merlin, Act III. sc.

iv.

" He by wordes could call out of the sky

Both sunne and moone, and make them him obey;

The land to sea, and sea to maineland dry,

And darksome night he eke could turn to day;

That to this day, for terror of his fame

The feendes do quake when any him to them does

name." Spenser.

THE fact that the name Art(h)us does not occur in the Gildas manuscript has led to the inference that the king was unknown to that chronicler; and the assumption that he is alluded to as Ursus (the Bear) tends to confirm the theory of those who would affirm that he is no more than a solar myth. It must be understood that the Arthur of romance, as we now know him, was a character ever increasing in importance and prominence as the history was rewritten and elaborated; at first a minor actor in the drama, he at length became the leading figure and the centre around which all the other characters were grouped. The Arthur of the historian Nennius is the original personage to whom all the famed attributes have been accorded by subsequent writers. With so much doubt and confusion, involving the identity of the person himself, it is inevitable that even more doubt and confusion should exist when we come to detailed events. Even the name of Arthur's father is variously given, a circumstance which caused Milton to question the veracity of the whole history; and the date of his birth, of his death, the age at which he died, and other smaller points, lead to nothing but endless contradiction. The number of his battles is variously given as twelve and seventy-six; he is said to have wedded not one but three Guineveres (Gwenhwyvar); his age at death varies from just over thirty years to over ninety; and the date of the last battle is 537, 542, or 630.*

* Arthur's career has been thus conveniently

summarised: " At the age of fifteen he succeeded his father as

King of Damnonium. He was born in 452, had three wives, of whom

Guinevere was the second, and was betrayed by the third during

his absence in Armorica. Mordred concluded a league with Arthur's

great foe, Cedric the Saxon; and at the age of ninety, after

seven years' continual war, the famous king was defeated at

Camelford in 543." Fuller compares him to Hercules in

(1) his illegitimate birth,

(2) his arduous life, and

(3) his twelve battles.

Joseph Ritson, whose antiquarian researches are noted for their

fullness and originality, came to the conclusion that though

there were " fable and fabrication " in the hero, a real Arthur

lies behind the legendary hero. He appeared when the affairs of

the Britons were at their worst after Vortigern's death, checked

the ravages of the Romans, and kept the pillaging Saxons at bay.

Professor Montagu Burrows, in his commentaries on the history of

England, argues that the Cymry of Arthur's time were a band of

Romano-Britons who produced leaders like Cunedda to take command

of the native forces left by the departing Romans. They remained

more British than Gaelic, but were gradually driven, with their

faces to the foe, into Wales and the Welsh borderland.

"The Arthurian legends," he continues, "embody a whole world of

facts which have been lost to history in the lapse of time, and

form a poetry far from wholly fictitious." Renan declares that

few heroes owe less to reality than Arthur. " Neither Gildas nor

Aneurin, his contemporaries, speaks of him; Bede did not know his

name; Taliesin and Llwarc'h Hen gave him only a secondary place.

In Nennius, on the other hand, who lived about 850, the legend

has been fully unfolded. Arthur is already the exterminator of

the Saxons; he has never experienced defeat; he is the suzerain

of an army of kings. Finally, in Geoffrey of Monmouth, the epic

creation culminates."

King Arthur's actual name may have been Arthur Mab-Uther; his genealogical line has been traced back to Helianis, nephew of Joseph; the year 501 is now usually accepted as the date of his birth; and St. David, son of a prince of Cardiganshire, is mentioned not only as his contemporary but as a near relative.

If the Sagas were compared with the Arthurian romances numerous points of resemblance could be shown. Olaf is the Arthur of the story, Gudrun the Guinevere, and Odin is the Merlin, while the city of Drontheim serves as Caerleon. The story recounting how Arthur magically obtained his sword Excalibur finds an exact parallel in the story of Sigmund, Volsung's son; and even the emblem of the dragon is not lacking,* for in the story of the Volsung we learn that Sigurd's shield bore the image of that monster, " and with even such-like image was adorned helm, and saddle, and coat-armour." But again it must be remembered that Arthur's kingdom is reported to have extended to Iceland itself; in fact, the bounds of his kingdom were only set by the chroniclers where their own definite geographical knowledge ended.

* Ashmole, in his History of the Order of the Garter, declares that, in addition to the dragon, King Arthur placed the picture of St. George on his banner.

"We cannot bring within any limits of history," Sir Edward Strachey has properly said, "the events which here succeed each other, when the Lords and Commons of England, after the death of King Uther at St. Albans, assembled at the greatest church of London, guided by the joint policy of the magician Merlin and the Christian bishop of Canterbury, and elected Arthur to the throne; when Arthur made Caerleon, or Camelot, or both, his headquarters in a war against Cornwall, Wales, and the North, in which he was victorious by the help of the King of France; when he met the demand for tribute by the Roman Emperor Lucius with a counterclaim to the empire for himself as the real representative of Constantine, held a parliament at York to make the necessary arrangements, crossed the sea from Sandwich to Barflete in Flanders, met the united forces of the Romans and Saracens in Burgundy, slew the emperor in a great battle, together with his allies, the Sowdan of Syria, the King of Egypt, and the King of Ethiopia, sent their bodies to the Senate and Podesta of Rome as the only tribute he would pay, and then followed over the mountains through Lombardy and Tuscany to Rome, where he was crowned emperor by the Pope, ' sojourned there a time, established all the lands from Rome into France, and gave lands and realms unto his servants and knights,' and so returned home to England, where he seems thenceforth to have devoted himself wholly to his duties as the head of Christian knighthood."

This is the very monstrosity of fable, the grossness of which

carries with it its own condemnation. These facts, however, are

not insisted upon by Malory, though such claims for Arthur were

made by the credulous and less scrupulous writers. Romance has

entirely remodelled his character, and has filled in all the gaps

in his life-story in that triumphant manner in which Celtic

genius manifests its power. The legendary Arthur is made to

realise the sublime prophecies of Merlin, and as those prophecies

waxed more bold and arrogant in the course of ages the

proportions of the hero were magnified to suit them. Merlin had

cherished the hope of the coming of a victorious chief under whom

the Celts should be united, but the slaughter at Arderydd when

the rival tribes fought each other, almost destroyed all such

aspirations. Nevertheless the prophet foretold the continuance of

discord among the British tribes, until the chief of heroes

formed a federation on returning to the world, and his prediction

concluded with the haunting words:

"Like the dawn he will arise from his mysterious retreat." Mr.

Stuart Glennie calls Merlin a barbarian compound of madman and

poet, prophet and bard, but denies that he was a mythic personage

or a poetic creation. He was, like Arthur himself, an actual

pre-mediaeval personage, and, as in the case of Arthur, we have

no means of determining his origin, his nationality, or the

locale of his wanderings. But if, as Wilson observes in one of

his " Border Tales," tradition is "the fragment which history has

left or lost in its progress, and which poetry following in its

wake has gathered up as treasures, breathed upon them its

influence and embalmed them in the memories of men unto all

generations," we shall extract a residuum of truth from the

fanciful fables of which Merlin is the subject.

Myrdin Emrys, the Welsh Merlin, is claimed as a native of Bassalleg, an obscure town in the district which lies between the river Usk and Rhymney. The chief authority for this is Nennius; but according to others the birthplace was Carmarthen, at the spot marked by Merlin's tree, regarding which the prophecy runs that when the tree tumbles down Carmarthen will be overwhelmed with woe. What we know of Merlin in Malory's chronicle is that he was King Arthur's chief adviser, an enchanter who could bring about miraculous events, and to whom was delivered the royal babe upon a ninth wave of the ocean; a prophet who foretold his sovereign's death, his own fate, and the infidelity of Guinevere; a warrior, the founder of the Round Table, and the wise man who "knew all thing's." Wales and Scotland alike claim as their own this most striking of the characters in the Arthurian story.

Brittany also holds to the belief that Merlin was the most famous and potent of her sons, and that his influence is still exercised over that region. Matthew Arnold, gazing at the ruins of Carnac, saw from the heights he clambered the lone coast of Brittany, stretching bright and wide, weird and still, in the sunset; and recalling the old tradition, he described how

" It lay beside the Atlantic wave

As though the wizard Merlin's will

Yet charmed it from his forest grave."

The Scotch Merlin, Merlin Sylvester, or Merlin the Wild, was Merdwynn of the haugh of Drummelziar, a delightful lowland region, where the little sparkling Pausayl burn bickers down between the heather-clad hills until it mixes its waters with the Tweed. He is said to have taken to the woods of Upper Tweeddale in remorse for the death of his nephew, though it is more likely that he lost his reason after the decisive defeat of the Cymry by the Christians of the sixth century. Sir Walter Scott records that in the Scotichronicon, to which work however no historic importance can be ascribed, as it is notoriously a priestly invention, is an account of an interview betwixt St. Kentigern and Merdwynn Wyllt when he was in this distracted and miserable state. The saint endeavoured to convert the recluse to Christianity, for he was a nature-worshipper, as his poems show. From his mode of life he was called Lailoken, and on the saint's commanding him to explain his situation, he stated that he was doing penance imposed upon him by a voice from heaven for causing a bloody conflict between Lidel and Carwanolow. He continued to dwell in the woods of Caledon, frequenting a fountain on the hills, enjoying the companionship of his sister Gwendydd ("The Dawn"), and ever musing upon his early love Hurmleian (The Gleam), both of whom were frequently mentioned in his poems. His fate was a singular one, and has been confused with that of the Merlin of Arthur. He predicted that he should perish at once by wood, earth, and water, and so it came to pass; for being pursued and stoned by the rustics others say by the herdsmen of the Lord of Lanark he fell from a rock into the river Tweed, and was transfixed by a sharp stake-

" Sude perfossus, lapide percussus, et unda,

Hzec tria Merlinum fertur inire necem.

Sicque ruit, mersusque lignoque prehensus,

Et fecit vatem per terna pericular verum."

The grave of the Scotch Merlin is pointed out at Drummelziar,

where it is marked by an aged thorn-tree. On the east side of the

churchyard the Pausayl brook falls into the Tweed, and a prophecy

ran thus:

"When Tweed and Pausayl join at Merlin's grave, Scotland and

England shall one monarch have." And we learn accordingly that on

the day of the coronation of James VI the Tweed overflowed and

joined the Pausayl at the prophet's grave. The predictions of

this Merlin continued for many centuries to impress the Scotch,

and he seems to have had a reputation equal to that of Thomas the

Rhymer. Geoffrey of Monmouth was the first to introduce a Merlin

into the Arthurian romance, and whether that Merlin had for a

prototype Merdwynn Wyllt, or whether there was in reality a

Merlin of Wales, remains an open question. All that can be said

definitely is that similar deeds are ascribed to both, that each

occupies a similar place among his contemporaries, that their

rhapsodical prophecies partake of the same character, and that

their mysterious deaths have points in common. But it is

contended that the vates of Vortigern and of Aurelius Ambrosius,

the companion and adviser of Uther Pendragon and of Arthur, was

Myrdin Emrys, who took his name from Dinas Emrys in the Vale of

Waters, whose haunt was the rugged heights of Snowdon, and who

knew nothing of the Merlin Caledonius who wandered about the

heathery hills of Drummelziar, who was present at the battle of

Arderydd in 573, and who lamented in wild songs the defeat of the

pagans and the shattering reverse to the Cymric cause. These

poems, which bewail the fortunes of this unfortunate race, seem

to have found their way into the famous Ancient Books of Wales,

thus tending further to confuse the two Merlins, and resulting in

the old chroniclers ascribing the acts of both to the Myrdin

Emrys of King Arthur's court. The late Professor Veitch's poem on

Merlin contains some specimens of Merdwynn Wyllt's verse, and

sets forth his faith in nature, tinged a little as it were by the

Christianity of the era.

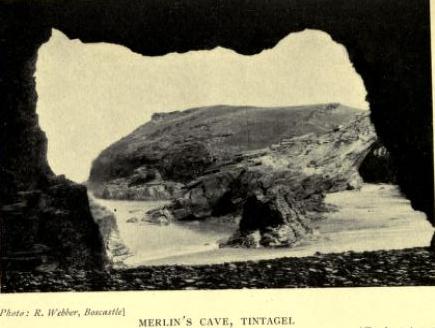

The Merlin of King Arthur was reputed to be a native of Carmarthen among other places, and at three miles' distance from the town may be seen " Merlin's Cave," one of the traditional places of his mysterious entombment. Merlin's birth formed the subject of one of the apocryphal plays of Shakespeare: the weird magician and worker of enchantment would have been worthy of the masters' own depiction. In the romances he comes with mystery and awe, and he departs with mystery and shame. " Men say that Merlin was begotten of a devil," said Sir Uwaine; and the maid Nimue (Vivien) on whom he was "assotted," grew weary of him, and fain would have been delivered of him, " for she was afraid of him because he was a devil's son." In that wondrously rich drama of 1662, " The Birth of Merlin," the popular tradition is taken up that the arch-magician was the son of the arch-fiend. The story introduces Aurelius and Vortiger (Vortigern), the two Kings of Britain; Ut(h)er Pendragon, the brother of Aurelius; Ostorius, the Saxon general; and other historic characters of the era. The chief point of the plot is the search for and identification of Merlin's father; and, that matter settled, the dramatist treats of Merlin's supernatural skill, his prophecies, and his aid of Vortiger in building the castle which hostile fiends broke down by night as fast as it was built by day. Merlin is represented as born with the beard of an old man, able to talk and walk, and within a few hours of his birth explaining to his mother that he reads a book ' ' to sound the depth of arts, of learning, wisdom, knowledge."

"I can be but half a man at best,

And that is your mortality; the rest

In me is spirit. "Tis not meat nor time

That gives this growth and bigness. No, my years

Shall be more strange than yet my birth appears."

He prophesies forthwith, recognises his father, the Devil, at a glance, gives proof of his miraculous powers in many ways; and proceeding to Vortiger's court baffles the native magicians, and shoivs the king why his castle cannot be built by reason of the dragons in conflict. He foretells that the victory of the white dragon means the ultimate victory of the Saxons " the white horror who, now knit together, have driven and shut you up in these wild mountains," and that the king who won his throne by bloodshed must yield it to Prince Uter. The prediction is verified, and after Vortiger's death Merlin is sent for to expound "the fiery oracle" in the form of a dragon's head,

" From out whose mouth

Two flaming lakes of fire stretch east and west,

And . . . from the body of the star

Seven smaller blazing streams directly point

On this affrighted kingdom."

The portent causes terror, until Merlin, as interpreter, tells of revolutions, the rise and fall of nations, and the changes in Britain's state which it signifies. Aurelius has been treacherously slain at Winchester by the Saxons, and Prince Uter is to be his avenger. The passage in which Merlin relates what is to come is one of singular dignity and impressiveness. Seven rays are "speaking heralds " to the island. Uter Pendragon is to have a son and a daughter. The latter will be Queen of Ireland, while of the son "thus Fate and Merlin tells "

"All after times shall fill their chronicles

With fame of his renown, whose warlike sword

Shall pass through fertile France and Germany,

Nor shall his conquering foot be forced to stand,

Till Rome's imperial wealth hath crowned his fame

With monarch of the west; from whose seven hills

With conquest, and contributory kings

He back returns to enlarge the Briton bounds,

His heraldry adorned with thirteen crowns.

He to the world shall add another worthy,

And, as a loadstone, for his prowess draw

A train of martial lovers to his court.

It shall be then the best of knighthood's honour

At Winchester to fill his castle hall,

And at his Royal table sit and feast

In warlike orders, all their arms round hurled

As if they meant to circumscribe the world."

This is a noble passage, and sums up the leading points in King Arthur's history, as related in the Fabliaux, and at the same time serves as evidence of the power of divination and eloquence of Merlin. The matter of the prophecy was obviously taken from Malory, but the dramatist introduced one strange variation in his story. Merlin, indignant that his demoniac father should strive to harm his mother, uses his art and magic spells to enclose the Devil in a rock an idea suggested, no doubt, by Merlin's own fate. Furthermore, finding himself called to aid Pendragon against the Saxons, Merlin conducts his mother to a place of retirement called Merlin's Bower, and tells her that when she dies he will erect a monument

"Upon the verdant plains of Salisbury

(No king shall have so high a sepulchre)

With pendulous stones that I will hang by art,

Where neither lime nor mortar shall be used,

A dark enigma to the memory,

For none shall have the power to number them."

Here we become acquainted with the superstition that the megalithic wonders of Stonehenge were Merlin's workmanship, and that the mysterious structure was his mother's tomb. Another idea was that it was the burial place of Uther Pendragon and Constantine. The drama, so far as it relates to Merlin and Vortigern, closely follows the popular tradition, though there are several variations of the story of the castle which could not be finished, and its site, as might be expected, is the subject of many contradictory declarations. The allegorical meaning of the story is quite clear. To the heights of Snowdon, it is said, Merlin led King Vortigern, whose castle could not be built for meddlesome goblins. The wizard led the monarch to a vast cave and showed him two dragons, white and red, in furious conflict. " Destroy these," he said, " and the goblins whom they rule will cease to torment you." Vortigern slew the dragons of Hate and Conspiracy, and his castle was completed.*

* Mr. Glennie thinks the scene is in Carnarvonshire, to the south of Snowdon, overlooking the lower end of Llyn y Dinas. Here is Dinas Emrys, a singular isolated rock, clothed on all sides with wood, containing on the summit some faint remains of a building defended by ramparts. It was of this place Drayton wrote

" And from the top of Brith, so high and wondrous steep Where

Dinas Emris stood, showed where the serpents fought,

The White that tore the Red; from whence the prophet wrought,

The Briton's sad decay then shortly to ensue."

On the south of Carnarvon Bay is Nant Gwrtheryn, the Hollow of Vortigern, a precipitous ravine by the sea, said to be the last resting-place of the usurper, when he fled to escape the rage of his subjects on finding themselves betrayed to the Saxons.

The story of Merlin's death has again led to much speculation upon the recondite subject of the situation of the tomb in which his "quick" body was placed by the guile of Nimue, or Vivien, one of the damsels of the lake. Malory distinctly avers that it was in Cornwall that the doting wizard met his fate. He went into that country, after showing Nimue many wonders, and "so it happed that Merlin showed to her a rock, whereat was a great wonder, and wrought by enchantment, that went under a great stone." By subtle working the maiden induced the wizard to go under the stone to tell her of the marvels there, and then she " so wrought him " that with all his own crafts he could not emerge again. Some time afterwards Sir Bagdemagus, riding to an adventure, heard Merlin's doleful cries from under the stone, but he was unable to help him, as the stone was so heavy that a hundred men could not move it. Merlin told the knight that no one could rescue him but the woman who had put him there, and, according to some traditions, he lives to this day in the vault. Spenser, in the Faerie Queene, describes the tomb as

"A hideous, hollow, cave-like bay

Under a rock that has a little space

From the swift Tyvi, tumbling down apace

Amongst the woody hills of Dynevowr."

The Tyvi is known to us as the Towy, and Dynevowr is Dynevor Park.

"There the wise Merlin, whilom wont, they say,

To make his wonne low underneath the ground,

In a deep delve far from view of day,

That of no living wight he might be found,

When so he counselled with his sprights around."

Others say that the guileful damsel led her doting lover to Snowdon, and there put forth the charm of woven paces and of waving hands until he lay as dead in a hollow oak. Sometimes an eldritch cry breaks upon the ear of the climber as he nears the summit of Snowdon: it is Merlin lamenting the subtlety of his false love, which doomed him to perpetual shame.

There is the Carmarthen cave, and there is a "Merlin's Grave" four miles from Caerleon, both of which are shown as Merlin's resting-place. But ancient bards told another strange tale of the fate of the 'boy without a father,' 'whose blood had once been sought to sprinkle upon the cement for the bricks of Vortigern's castle. They declared that the enchanter was sent out to sea in a vessel of glass, accompanied by nine bards, or prophets, and neither vessel nor crew was heard of again which is not surprising. But Lady Charlotte Guest, in her notes to the Mabinogion, boldly transports the scene of Merlin's doom to the Forest of Breceliande, in Brittany, one of the favoured haunts of romance and the delight of the Trouveres. Vivien, to whose artifices he succumbed, is said to have been the daughter of one Vavasour, who married a niece of the Duchess of Burgundy, and received as dowry half the Forest of Briogne. It was when Merlin and Vivien were going through Br^ce'liande hand in hand that they found a bush of white thorn laden with flowers; there they rested, and the magician fell asleep. Then Vivien, having been taught the art of enchantment by Merlin, rose and made a ring nine times with her wimple round the bush; and when the wizard woke it seemed to him that he was enclosed in the strongest tower ever made a tower without walls and without chains, which he alone had known the secret of making. From this enmeshment Merlin could never escape, and, plead as he would, the damsel would not release him: But it is written that she often regretted what she had done and could not undo, for she had thought the things he had taught her could not be true. This, however, seems to be an interpolation. Sir Gawain, travelling through the forest, saw a "kind of smoke," and heard Merlin's wailing voice addressing him out of the obscurity.

The wonders of the Forest of Bre"ce"liande were sufficiently believed in of old time that we find the chronicler Wace actually journeying to the spot to find the fairy fountain and Merlin's tomb. Another variation of the story is that Merlin made himself a sepulchre in the Forest of Arvantes, that Vivien persuaded him to enter it, and then closed the lid in such manner that thereafter it could never be opened. Matthew Arnold, sparing and reticent in speech, as is his wont, describes Merlin's fate with subdued force and subtle charm, putting the story in the mouth of desolate Iseult, who told her children of the "fairy-haunted land" away the other side of Brittany, beyond the heaths, edged by the lonely sea; and of

"The deep forest glades of Broceliand,

Through whose green boughs the golden sunshine creeps,

Where Merlin by the enchanted thorn-tree sleeps."

Very cunningly and mystically has the poet told of Vivien's guile as she waved a wimple over the blossom 'd thorn-tree and the sleeping dotard, until within "a little plot of magic ground," a "daisied circle," Merlin was made prisoner till the judgment day. Celtic mythology, Renan tells us, is nothing more than a transparent naturalism, the love of nature for herself, the vivid impression of her magic, accompanied by the sorrowful feeling that man knows. When face to face with her, he believes that he hears her commune with him concerning his origin and destiny. The legend of Merlin mirrors this feeling," he continues. " Seduced by a fairy of the woods, he flies with her and becomes a savage. Arthur's messengers come upon him as he is singing" by a fountain; he is led back again to court, but the charm carries him away. He returns to his forests, and this time for ever."

"La foret de Brocelinde," writes Emile Souvestre, in that fascinating and half-pathetic work, Les Derniers Bretons, "se trouve situee dans le commune de Corcoret, arrondissement de Ploermal. Elle est celebree dans les romans de la table ronde. C'est la que Ton rencontre la fontaine de Baranton, le Val sans retour, la tombe de Merlin. On sait que ce magicien se trouve encore dans cette foret, ou il est retenu par les enchantements de Viviane a 1'ombre d'un bois d'aubepine. Viviane avait essaye" sur Merlin le charme qu'elle avait appris de luimme, sans croire qu'il put operer; elle se desespera quand elle vit qui celui qu'elle adorait etait a jamais perdu pour elle." This statement is not confirmed in the English romance, and is opposed wholly to the sentiment of the story as conceived by Tennyson and other modern writers. " On assure que Messire Gauvain (Gawain) et quelques chevaliers de la table ronde chercherent partout Merlin, mais en vain. Gauvain seul 1'entendit dans la fort de Brocelinde, mais ne put le voir. " The district of Brocelinde, or BreceJiande, is rich in antiquities, dolmens and menhirs being found together with other relics of early times and the mysterious workers of the stone age. To add to the scenic attractions of the locality there are ruined castles, the remains of machicolated walls, ancient chateaux, and churches dating back many centuries. It is fitting that here, therefore, romance should maintain one of its strongholds and that traditions of the master-magician should linger.

There is yet one other legend which should be noted. It represents the magician as perpetually roaming about the wood of Calydon lamenting the loss of the chieftains in the battle of Arderydd; while yet another tells of a glass house built for him in Bardsey Island by his companion, the Gleam, in which house of sixty doors and sixty windows he studied th,e stars, and was attended by one hundred and twenty bards to write down his prophecies. Never was such a confusion of traditions and fancies, never were so many deluding will-o'-the-wisps to lead astray whosoever would strive to investigate the truth of Merlin's story. That story with its abundance of suggestion makes us think of the apt words of John Addington Symonds, who said that the examination of these mysterious narratives was like opening a sealed jar of precious wine. " Its fragrance spreads abroad through all the palace of the soul, and the noble vintage upon being tasted courses through the blood and brain with the matured elixir of stored-up summers." One needs some such consolation as this for the vexation of finding seemingly inextricable confusion.

Warrior though he was, and all-powerful by reason of his supernatural gifts, Merlin is yet represented as being a peace-maker and as paying allegiance to a "master." He ended the great battle between Arthur and the eleven kings, when the horses went in blood up to the fetlocks, and out of three-score thousand men but fifteen thousand were left alive. Of this sanguinary battle of Bedgraine, Merlin gave an account to his master Blaise, or Bleys, journeying to Northumberland specially to do so and to get the master to write down the record; all Arthur's battles did Blaise chronicle from Merlin's reports. Attempts have been made to identify Blaise (the Wolf) with St. Lupus, Bishop of Troyes. The more impressive part which Merlin plays in the Arthurian drama is as prophet and necromancer. His sudden comings and goings, his disguises, his solemn warnings, his potent interventions, all these combine to strengthen the idea of unequalled influence and of awesome personality. He figures prominently in the story of Sir Balin le Savage, and it was his hand which wrote the fitting memorial of the two noble brothers. Merlin it was again who counselled the king to marry, and who brought Guinevere to London from Cameliard, darkly predicting at the same time that through the queen Arthur should come to his doom.

An ancient Cornish song, to be found in the original dialect, but in reality a Breton incantation which has come down to us from the far ages out of the abundance of Armoric lore, describes Merlin the Diviner attended by a black dog and searching at early day for

"The red egg of the marine serpent,

By the seaside in the hollow of the stone."

Asked whither he is going he responds:

"I am going to seek in the valley

The green watercress and the golden grass,

And the top branch of the oak,

In the wood by the side of the fountain."

A warning voice bids him turn back and not to seek the forbidden knowledge. The cress, the golden grass, the oak branch, and the red egg of the marine serpent are not for him. " Merlin! Merlin!'' cries the voice,

"Retrace thy steps,

There is no diviner but God."

It is like a moral message from Goethe's Faust.

There is no doubt that Merlin's death, which is no death, but a blind grovelling and eternal uselessness, was the mark of scorn put upon the magician who might have been prepotent, but who prostituted his powers a feebleness and a degradation which were intolerable to the sturdy race who prized courage above all other qualities, and were incapable of realising the meaning of defeat or despair. That the counsellor should himself turn fool, and that the man of supernatural gifts should be prone to the weakness of nature, would be obnoxious to the Celtic imagination, and have its sequel in ribald allusion and endless taunts. The disaster which overtakes Merlin is one fitting for the coward or the buffoon, and is a fate altogether foreign to the ancient idea of that which was fitting for the hero, the bard, or the sage. It is noticeable that all the former services of Merlin are forgotten in judging him upon the closing despicable episode in his career and consigning him to timeless indolence and impotence. Shorn of his strength, a prisoner, living but " lost to use and fame," Mage Merlin in his cave, victim to his own folly and a woman's wiles, awaits the last doom.