|

|

The Lost Land Of King Arthur By J. Cuming Walters

CHAPTER IV

OF TINTAGEL

" There is a place within

The winding Severne sea,

On mids of rock, about whose foote

The tydes turn, keeping play,

A tower-y topped castle here,

Wide blazeth over all,

Which Corineus' ancient broode

Tintagel Castle call." Camden.

"Thou seest dark Cornwall's rifted shore,

Old Arthur's stern and rugged keep,

There, where proud billows dash and roar,

His haughty turret guards the deep.

"And mark yon bird of sable wing, Talons and beak all red with

blood,

The spirit of the long-lost king

Passed in that shape from Camlan's flood." R. S. Hawker.

CORNWALL, the horn-shaped land, far removed from the great centres of progress and industry, the land of giants, of a separate people who until the last century spoke its own language;* the land of holy wells and saints, of hut circles, dolmens, and earthwork forts, memorials of extreme antiquity; the land of many stone crosses indicating the early influence of Christianity; the land of so-called giants' quoits, chairs, spoons, punchbowls, and mounds, sometimes the work of primitive man, sometimes the work of fantastic Nature this is the land in which romance lingers and in which superstition thrives, the land upon which seems to rest unmoving the shadow of the past. Olden customs survive, the old fashion is not departed from. The quaintness, the simplicity, the quietude, the charm of a bygone age may be found yet in that part which Taylor, the water poet, described as " the compleate and repleate Home of Abundance, noted for high churlish hills, and affable courteous People. ' '

* The Cornish language was spoken until 1768. In that year Daines Barrington met the old fish-wife Dolly Pentreath, whose name has become memorable as that of the last person to speak Cornish. The last sermon in Cornish was preached in 1678 in Landewednack Church. The slackening of the Saxon advance at the Tamar enabled the Cornish to preserve their tongue, closely allied to that of Wales and Brittany, and described as " naughty Englysshe " in the reign of the eighth Henry.

A tour through the land which romance has marked out for her own, and where the fords, bridges, hills, and rocks are called after Arthur or associated by tradition with his exploits, becomes easier every year by the development of railways, little known in the wilder parts until a decade or so ago. It must be sorrowfally confessed that the visit to Tintagel, despite its charm, results in a certain amount of disillusion. It contains no relic, nothing that can verily be imagined a relic, of the old, old times when the flower of chivalry ruled. As one walks down the solitary street and glances around he sees that Tintagel is an antique, picturesque little place with its quaint post-office of yore battered by time, the roof fallen, and the stonework disjointed with its stunted cottages, its typical village shop and hostelry, and its lonely church on the cliffs. Tintagel, as it is, is unique, but it is not Arthurian unless we go direct to those parts where Nature is not and never has been molested. The Pentargon heights, the great gorges, the weird bays and caves, the rock-strewn valleys, the imposing waterfalls from these may be constructed the scenery for the drama of the warlike king and his adventurous knights. The huge bank of earth enclosing an oblong space, with its remnant of stone-lining found near St. Breavard, is fitly called King Arthur's Hall. Such relics as are found in and near Tintagel are posterior to King Arthur's era. There is a Saxon cross to be seen, erected to the memory of one ^Elnat, a Saxon. A sybstel, or family pillar, with Saxon inscription, found in Lanteglos Church, near Camelford, and a Roman stone discovered in Tintagel churchyard, are ancient memorials of the highest interest. Relics of the bronze age have been discovered also, though the influence of the Phoenician tin-traders did not seemingly extend to this mid part of Cornwall.

Tintagel, as the first locality mentioned in the romance, has a special claim to attention: "It befell in the days of the noble Uther Pendragon, when he was King of all England, and so reigned, that there was a mighty and a noble Duke in Cornwalle that held long time wars against him; and the Duke was named the Duke of Tintagil. " So run the opening lines, introducing us at once to the western territory and to the rocky stronghold indissolubly linked with Arthur's fame. Strange to say, however, the place is absolutely ignored in the later half of the history, despite the fact that Cornwall was the scene of some of the most important concluding events. Tintagel was apparently forgotten by the chroniclers after the story of Tristram was related, and the last mention of it as King Mark's Castle, where treachery was followed by bloodshed, where the allegiance of the knights began to decline, and where folly, wantonness, and shame served as omens of coming disaster and of the impending shock to the realm which Arthur had made. The history of Tintagel begins in a tale of shame, though King Uther's deceit of Igraine appears to have been regarded less as dishonour to himself than as a sign of his own and Merlin's strategy and venturesomeness.* Uther, having compassed the death of Gorlois, had no further difficulty in persuading Igraine to become his wife, and their son was Arthur, who at his birth was delivered to Sir Ector, "a lord of faire livelyhood," to be nourished as one of his own family. The death of Uther while his son was yet an infant left the succession in some doubt, and in order to prove Arthur's right to the crown the familiar device was adopted of drawing a sword from a stone.

* The following curious little item from R. Hunt's volume ought not to be lost sight of: " I shall offer a conjecture, touching the name of Tintagel, which I will not say is right but only probable. Tin is the same as Dm, Dinas, and Dixeth, deceit; so that Tindixel, turned for easier pronunciation to Tintagel, Dundagel, etc., signifies Castle of Deceit, which name might be aptly given to it from the famous deceit practised here by Uther Pendragon by the help of Merlin's enchantment." George Borrow says: "Tintagel does not mean the Castle of Guile, but the house in the gill of the hill, a term admirably descriptive " (Wild Wales, cap. cvii.).

The scene of the contest in which Arthur, now assumed by the chroniclers to be a goodly youth, and Sir Ector's son took part, is vaguely described as being " the churchyard of the greatest church in London"; and it is needless to say that only Arthur proved equal to the feat of pulling the sword from the marble and the steel anvil in which it stood. The letters of gold on the sword declared that "whoso pulleth out this sword of this stone and anvile, is rightwise king borne of England," and Sir Ector and Sir Kay, his defeated son and Arthur's foster-brother, were the first to kneel to Arthur as their lord when they saw Excalibur in his hand. Before the lords and commons Arthur again proved his right and royalty at the feast of Pentecost, and with the help of Merlin he proceeded immediately to establish his kingdom, which, during Uther's illness and after his death, had stood "in great jeopardie."

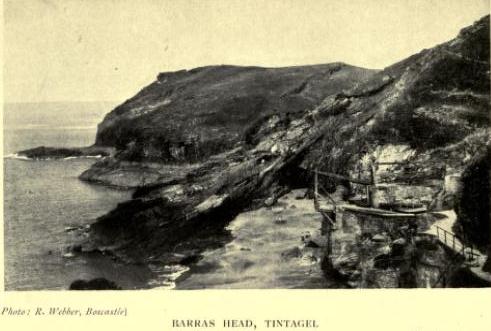

Gorlois, the husband of Igraine, had been the possessor of two castles, Tintagel and Terabyl (or Damaliock), which may be judged to have been at no great distance from one another. Terabyl is untraceable, though it has been suggested that while Tintagel Castle was solely upon the peninsula (Barras Head) which juts into the sea, Terabyl was the castle upon the mainland. This theory is untenable. It is only in comparatively recent times, with the widening of the chasm between the peninsula and the mainland, that a division of any importance can be noticed; and it is safe to assume that there was never more than one castle at Tintagel. The rent in the rocks was spanned by a huge bridge, as the crenellated walls now reaching to the edge on either side and in a direct line with each other plainly attest. Terabyl, in which the Duke entrenched himself when Uther Pendragon brought his hosts against him, was evidently further inland than Tintagel, and the latter, distinctly avowed to be " ten miles hence," was selected as the refuge for Igraine. Uther, marching southward from Camelot, reached Terabyl first and laid siege to it; to reach Igraine at Tintagel he had still to ride some distance. "The Duke of Tintagil espied how the king rode from the siege of Terrabil, and, therefore, that night he issued out of the castle at a posterne " (Terabyl was noted for its " many issues and pasternes out ") " for to have distressed the king's host. And so, through his own issue, the Duke himself was slain or ever the king came at the castle of Tintagil." Geoffrey of Monmouth calls Terabyl "castellum Dimilioc," but under this name it is no less a mystery. As it receives incidental mention only twice afterwards we may well be content to rank Terabyl among the cities of romance, the names of which alone existed. It may have been as unsubstantial as the enchanted cities created by mysterious maidens for their courteous and faithful lovers, which cities vanished in a night if vows were broken or false words uttered.

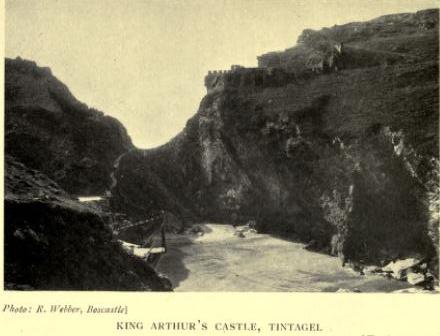

It is said in some of the romances that twice a year the Castle of Tintagel became invisible to the eyes of the common people. To-day it is only in imagination that we can perceive the real castle of Arthur, for whatever British fortress may ever have risen on these heights has long since vanished crumbled away into dust which is as nothingness. Authentic history takes us back only to the time of the Norman Conquest, when Tintagel was entered in Domesday Book as Dunchine, or Chain Castle. It is the firm opinion of archaologists that the Romans entrenched themselves here and left signs of their occupation, and there are the strongest reasons for believing that Tintagel was a British place of defence before the Roman invasion. Nature had marked out the rocky height as a stronghold, and a race like the Britons could scarcely have failed to avail themselves of all the advantages it offered. But when we first read of Tintagel Castle apart from the romances we find it in the occupation of English princes, notably of Richard, Earl of Cornwall, otherwise known as the King of the Romans, who in 1245 gave noble entertainment to his nephew, Prince of Wales, then carrying on a desperate war for freedom against the English king. The use of Tintagel as a prison from which escape was almost impossible was recognised from early times until the reign of Elizabeth, at which era it began to fall into decay; and it was within the loneliest and most exposed portion of the island that John Northampton, Lord Mayor of London, who had abused his office, was immured for life by order of Richard II. A sculptured moorstone, now moss-covered and illegible, commonly called the altar-stone of King Arthur's Chapel, is believed in reality to be a monument of John Northampton's own carving, wrought to pass away the dreary days in his dungeon, and now marking the place of his tomb. What is known as King Arthur's Chapel is a spacious chamber fifty-four feet long and twelve feet wide, the outline of which is barely traceable. It is supposed to have been dedicated to Saint Uliane. In Leland's time Tintagel Castle was "sore wether-beten an yn mine," and whether it was ever the stronghold of Arthur history does not determine. The name was formerly Dundagil, meaning "the impregnable fortress," and Geoffrey of Monmouth did not exaggerate when he wrote of it: "It is situated upon the sea, and on every side surrounded by it, and there is but one entrance into it, and that through a straight rock, which three men shall be able to defend against the whole of the kingdom." Leland, less interested in the matter, testified that " the castelle hath bene a marvelus strong and notable forteres, and a large thinge. . . . Without the isle rennith alonly a gate-house, a walle, and a fals braye dyged and walled. In this isle remayne old walles, and in the est part of the same, the ground beying lower, remaynith a walle embateled, and men abyve saw thereyn a postern dore of yren."

The chronicler and antiquary Carew supplies further evidence of the strength of the structure. "The cyment," he says, "wherewith the stones were laid, resisteth the fretting furie of the weather better than the stones themselves," a fact which is strongly commented on also by Norden, who thought that " neither time nor force of hands could sever one from the other." "Half the buildings," continues Carew, "were raised on the continent (the mainland) and the other halfe on an island, continued together by a drawbridge, but now divorced by the downfalne steepe cliffes on the further side." There is a consensus of opinion as to this drawbridge, Camden and other trustworthy historians all confirming the report as to its existence, and this further proves that there were not two castles at Tintagel.* The gigantic impression of a foot is pointed out to credulous pilgrims; it is the print left by King Arthur's foot when he strode across the chasm backwards. This is as much to be relied upon as the fact that the basins worn by the winds and waves in the rocks were King Arthur's cups and saucers, and that a dizzy dip of the heights over the sea constituted his chair.

* It is difficult to understand how a writer like the late Mrs. Craik could ever have fallen into this error. In her Unsentimental Journey through Cornwall she makes every effort to prove that the building on the mainland was the castle of Terabyl, and she insists that there were (and are) two castles at Tintagel. " One sits in the sea, and the other is upon the opposite heights of the mainland, with communication by a narrow causeway. This seems to confirm the legend, how Igraine's husband shut himself and his wife in two castles, he being slain in the one, and she married to the victorious king Uther in the other." It is obvious that the writer of these lines was unacquainted with Malory.

It is surprising that the immense and awe-inspiring caverns have escaped the fate of being called King Arthur's drinking-bowls. Yet all these conceits have their value as proof of the deep-rooted belief in the king's might as a monarch and his stupendous stature as a man. The hero is rapidly passing into the myth when such attributes are ascribed to him.

Tintagel must have been even more impressive a scene a few centuries ago than it is to-day, despite its wild sublimity in ruin. One more witness of old time may be called forth to give his evidence of what it was before the walls had been so buffeted and brought so low.

"A statelye and impregnable seate," is Norden's testimony, " now rent and rugged by force of time and tempests; her ruines testifye her pristine worth, the view whereof, and due observation of her situation, shape, and condition in all partes, may move commiseration that such a statelye pile should perish for want of honourable presence. Nature hath fortified, and art dyd once beautifie it, in such sorte as it leaveth unto this age wonder and imitation." Tintagel is to be visited rather than described, though our most luxuriant poets have painted it with lavish richness of words, and artists have depicted some of its natural beauties in the most radiant of colours. From many a rocky verge can be seen the dark remnants of Arthur's fortress, inaccessible on all sides but one; from the deep base the ocean spreads out without bound, surging and boiling and casting up steam-like fountains of hissing foam. Only a few arches and rude flights of steps, surmounted by a frail-looking wooden door, now remain, with some fallen walls which imperfectly outline the shape of what were once spacious royal chambers. On a carpet of turf wander the small mountain sheep, and pick their way about the narrow precipitous paths which wind around the jagged sides of the cliffs. The fortifications are in ruin, and the battlemented walls which encompassed the massive steeps are now nothing but disconnected strips over which the curious traveller looks into the angry waters grinding and regurgitating far below. The noble bridge which once stretched across the yawning chasm dividing the two promontories must alone be imagined, though its beginnings on each side may be traced by the line of low stone arches reaching, and stopping abruptly at, the edge. The hills "that first see bared the morning's breast," the heights " the sun last yearns to from the west," as Swinburne has sung, are eternal, but Arthur's castle has gone, and Tintagel, " half in sea and high on land, a crown of towers," is even called by the dwellers no more by its old inspiring name.

The very mention of Cornish seas has an alluring sound, and one already feels in the realm of romance when he descries in the mellow light of an afternoon in late summer that smallest of villages perched upon a rock overlooking the bluest of seas with its perpetual fringe of powdery foam. Here at the edge of the Atlantic is a most beguiling stretch of water, filling innumerable bays water so clear and calm and deep-hued far away that it is hard to realise that it makes a cruel and treacherous sea in which only on the gentlest of days dare a swimmer plunge and feel his way among the underlying rocks, or upon the roaring waves of which dare a hardy sailor venture his boat. In storm this sea is terrible. The waves upheave themselves like solid hillocks of water, black at the base, and hurl themselves with appalling force against the huge rocks, which have already been worn and broken by them into a thousand fantastic shapes. Here and there the propelling force of the incoming tide, working like a gigantic engine, sends with torrent-force along narrow open passages a seething stream which beats its way upward and dashes headlong over the barriers of wood and stone; and the great smoke-coloured waves beyond rear themselves heavily, topple, and crash down into the abyss with thunderous roaring. On they come, nearer and nearer, louder and louder, those hard, rising, climbing, dissolving bodies of incalculable strength, dashing themselves furiously over every obstacle, sweeping with a hiss across the tracts of sand, and obliterating the tall rocks which can be toilsomely climbed when the waters retreat. Beneath this raging, battering sea lies a fabled domain with all its fair cities and towers, and every watcher of those stupendous, merciless billows can realise their potentiality to tear away the land and drag it into the unseen deeps. Storm at Tintagel or Trebarwith is both revelation and conviction: it is a manifestation of remorselessness, a suggestion of irreparable ruin, desolation, and loss. Easy indeed is it to imagine that the treacherous and cruel waves driving rapaciously landward have already had their victory and are savagely seeking to extend their conquest, and that hereabout lie " the sad sea-sounding wastes of Lyonnesse."

No one has described this wildly beautiful sea with greater charm and realism than Swinburne, who has watched it in all moods, seen it in the blueness of calm, seen it strive and shiver " like spread wings of angels blown by the sun's breath," seen it when the glad exhilarated swimmer feels

" The sharp sweet minute's kiss

Given of the wave's lip, for a breath's space curled

And pure as at the daytime of the world,"

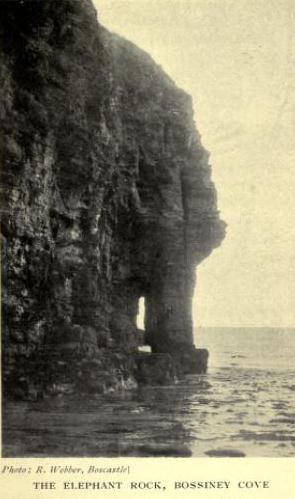

seen it again when the east wind made the water thrill, and the soft light went out of all its face, and the green hardened into iron blue. A walk from Camelford to Tintagel, passing Trebarwith, and on from Tintagel to Boscastle, passing Bossiney and many a smaller cove on the way, reveals the most wonderful and alluring of all changeful sea-pictures, and displays most vividly the marvel and magic of the rugged coast. The towering rocks have been wrought by time and carved by wind and wave into grotesque images, broken at the base into sunless caves, worn at the heights into sharp and gleaming pinnacles, fretted and cut, rounded and cracked, sundered and cast down, the massive blocks made veritably the sport of the elements, so that the beholder may easily believe himself in the realm of enchantment. All the sounding shores of Bude and Boss are legend-haunted.

The mariner hears the chime and toll of the lost bells of Bottreaux when he comes within sight of the "silent tower," which stands white and grim upon the headland. The wail of lured voyagers and the despairing lament of the smugglers who brought them with false lights to their doom are listened to in awe on stormy nights, and there are visions of good ships that went down among the rocks in the tragic desperate days of which so many ghastly tales are told. The last of the Cornish wreckers, for whom, when he lay dying, a ship with red sails came in a tremendous sea and bore him shrieking away, looms as an apparition on the darkest nights, and the cries of tormented spirits mingle with the blast. Merlin, with flowing beard, is said to pace the shore, and Arthur and his knights to revisit the scenes of their exploits. The spirit of the king hovers about sea and land in the form of the almost sacred chough, reverenced and preserved by the inhabitants that they may not unwittingly injure their hero. Further north at Bude Haven the long Atlantic breakers roll, and perhaps there is no more imposing spectacle than the coil of waves coming in upon the far-extending and rock-strewn sands.

The undulations, miles long, seem to rise and curl far out at sea at short regular distances from each other, and mass upon mass they break with thunder-sound and cataract upon the shore. The most brilliant of sunsets glow in the perfect summer weather when day dies slowly over these "far-rolling, westward-smiling seas," and they leave the night still radiant. The whole land is sweet and bright with flowers: on one side lies the glittering surf lacing itself in white foam about the boulders, and on the other side rises the circle of hills topped by the massy brown summits of Row Tor and Brown Willy. Sometimes the deserted quarries give a spectral look to the landscape, and when the rain spatters and darkens the piles of rough slate the aspect is weird and gloomy indeed. But given a day of sunshine when the sea is a sparkling emerald or the deepest of blues, when the sky is clear or only softened with diaphanous rings of cirrus-cloud, when the moss glistens on the rocks and the expanse of meadowland is a vivid carpet of green, when the winding hilly lanes flanked by tall hedges are white and shadowless, and the little tinkling runlets are silver gleams, and then this tract of Arthur's Cornwall is almost the land of faerie which poets have sung.

What more fitting than that the grave of Tristram and Iseult should have been at Tintagel, where the sea they loved came with its strong and awful tides, and now

" Sweeps above their coffined bones

In the wrecked chancel by the shivered shrine"?

The deep sea guards them and engirds them, and no man shall say where the lovers lie in their last sleep. King Mark buried the two in one grave, and planted over it a rose-bush and vine, the branches of which so intermingled that they became inseparable. Arnold, Swinburne, and Tennyson have best told the whole story in our language in modern times. But it is no slight task to trace the literary history and development of the beautiful theme. A German minnesanger of the twelfth century, Gotfrit of Strasburg, is the first to whom the romance is ascribed, though Scott and others have claimed for Thomas of Ercildoune (Thomas the Rhymer) the best poetic version, only one copy of which is extant. A thirteenth-century manuscript, which contains a French metrical version of the romance, has been noted by Lockhart as citing the authority of Thomas the Rhymer for the story of Tristram and Iseult; but Thomas's version was totally different from the prose romances. Great efforts have been made at one time and another to prove the story to be of English, French, and German origin, but at least this much is assured the principal scenes are English, and the leading events in the history of Tristram, the nephew of King Mark of Cornwall, occur at Tintagel. He journeyed to Ireland to bring back the daughter of the queen of that country, and he journeyed to Brittany to bring back his own wife, that Iseult of the White Hand who failed to win his love. His adventures as a Knight of the Round Table took him, as was usual, over much territory and to foreign lands; but it is to Cornwall that the interest always returns, and in which it is concentrated. Among the "wind-hollowed heights and gusty bays " of Tintagel, and within the "towers washed round with rolling foam," the knight and the damsel wedded to King Mark, who had saved him from torture and death, lived their lives of forbidden love. The Minstrel-knight suited his voice to the mellow chords of his harp, and wandered about the woods and beside the sea in the May-time of his happiness with Iseult the Queen. And when the knight had wedded another Iseult, it was at Tintagel that Mark's wife, with her passionate thoughts, her sorrow, and her despair, sat alone in a casement and heard the night speak and thunder on the sea "ravening aloud for ruin of lives." Such words can be easily comprehended by those who have seen Tintagel in storm, the wind roaring, the seas flashing white, a blinding mist of rain between the heavy sky and the weltering waves. The rage of the elements, the vehemence of the warring tide, the dash and the recoil at the castlebase, have only their parallel in the human passion which was too strong for life itself to withstand, when deserted Iseult saw before her the corpse of her lover. Tristram, ill-fated from birth, was doomed to die by treachery. He was wounded, and learnt that he could only be healed by the magic art of the woman he loved, of her who had cured him before. He sent for Iseult to cross the sea in order to save him, and commanded the messenger to hoist a white sail if she consented and was on her way. The white sail was hoisted, but the other Iseult, the faithful but neglected wife, could not resist saying what jealousy prompted that the sail was black. Sir Tristram immediately expired. Malory's romance declares that the knight met his death at the hands of King Mark, who slew him "as he sat harping afore his lady La Beale Isoud, with a trenchant glaive, for whose death was much bewailing of every knight that ever were in King Arthur's days."

The literary history and the variations of the extremely ancient and supremely sorrowful story can only be adequately treated in such a volume as that of M. Losseth, who has given an account of twenty-four manuscripts containing Tristram's history, of six works in the French National Library, of Malory's version, and of one Italian, two Danish, and one German translation or original rendering. Some have attributed the authorship to Cormac of Ireland in the third century; others believe the Welsh bards first sang it; the French claimed it for their troveres, but have now admitted its British origin. Yet it is remarkable how French, Cornish, and Irish histories intermingle in the romance, and how the magic element occasionally enters, spoiling it as history but enriching it as a legend. The story is one of such pathos that the predominating influence of the Celt in suggesting and shaping it must instantly be recognised. But so many have worked on the theme, early and late none perhaps with such superb effect as Wagner that the primitive conception is apt to be forgotten or ignored; it has been overlaid with details gathered from many lands, and embellished by the poetic fancies of many races. The story has become European; Beroul, Christian of Troyes, Thomas of Brittany, Robert the northern monk, Eilhard of Oberge, Gottfrid and the other early Germans, the Provencal minstrels all these have altered and added to the tale of the knight who slew the sea-monster, the Morhout, saved the Cornish maidens from shame and death, was wounded by a poisoned arrow, healed by Iseult the Beautiful, and both of whom, drinking of a magic love-potion intended for Iseult 's destined husband, afterwards experienced all the joys and pangs of an unhallowed love which Dante himself could not refrain from celebrating and condoning. The story abounds in mystic symbolism, or, rather, that symbolism has been found in it; and the inevitable Sun-god myth has been perceived in its details.

Tintagel, a picture in the waters, is at its best when the sky becomes a rose above it, and the sun dipping into a golden bath leaves a track gleaming like pearl across the shoaling sea. The waves as they rise and fall, make emerald and purple lines in moments of magic change, and their crests of foam sparkle jewel-like with a thousand instantaneous lights. Then "all the rippling green grows royal gold " as the sun, like a splendid bubble, floats on the water's edge. Round the pointed brown rocks are fringes of white foam ever widening and contracting; the oncoming waters with an exultant bound sometimes spring high in fountains and then sink slowly and gently as if fairy spires were dissolving in thinnest powder. Again, with a roar and an access of strength, the waves return impetuously, raging and grinding, churned as by some mighty hidden wheel into yeasty foam. Vista-like the long bright track, now a deep red band, leads back to the inner chambers of the sun, and the sea draws the orb into its dark, mysterious depths. The waves lace themselves around the pinky-green islets, and the verdant headlands, succeeding each other in almost interminable series till the eye catches the gleam of the Lizard lights, begin to soften mistily away behind the twilight veil. A little ship, far off, skims over the sea-rim and disappears; a tiny cloud floats up like a loose silken sail, silvery white. The seagulls and the choughs flit about the broken arches of the castle, and shadows fall long and deep across the deep ravinous path leading inland from the precipitous heights.

At such time Tintagel is telling its own story, weaving its own romance; and words seem vain when those shattered columns, those fallen walls, that unbridged chasm, are there to make the tale. Of the after-history of the place what matters it?

We would fain have the story end, as it began, with Arthur and Guinevere, King Mark, Mage Merlin, and Tristram and Iseult. Every roll of the breakers is a voice from the past, and every crumbling chamber a chapter in that history which only the true poet transcribes. Yet even while such thoughts are forcing themselves upon the mind of the beholder of a typical August sunset over Tintagel, the end of the day will be near. The arc of the sun blazes upon the sea-line, an edge of fiery carmine, and a fleecy train of cirrus-cloud crimsons with the last rays. Slowly and yet perceptibly the light dies away and leaves the heaving sea mystically dusk and the world full of shadows. Darkness looms over Tintagel. The overhanging crags look as if they might crack, break off, and thunder down into the openmouthed sea below. The black chough wheels about the ruins the spirit of Arthur, say the people, revisiting the scene of his glory. Arcturus, the star of Arthur, glistens in the blue sky right over the castle height, and Arthur's Harp shapes itself more dimly further east for the constellations themselves were named after the puissant king. The tide is at its height and has flooded the little stony beach to which a steep path leads; the caves are full; on the horizon the night-clouds come up and shape themselves into fantastic forms of towers, and the real which are near, and the imagined which are far, scarce can be distinguished.

Lytton seems to have had Tintagel, or a very similar place in the north, in his mind when he described the arrival of the Cymrian King, pursued by the Saxons, at a beach of far resounding seas where wave-hollowed caves arched, and

"Column and vault, and seaweed-dripping domes

Long vistas opening through the streets of dark,

Seem'd like a city's skeleton, the homes

Of giant races vanish'd."

This tract of land around Tintagel is crowded with memorials and with relics about which superstition has cast its web. The caer-camp at Trenail Bury, and the huge stone monuments which lie embedded in the earth, take us back to British times. The pools, looking black and weird among the hills, all have their legends, and the wells commemorate a multitude of saints known only to Cornwall. Castle-an-Dinas looms majestically at a height of nearly eight hundred feet against the horizon: here was King Arthur's hunting ground, and the remains of the structure cresting the summit was his palace. The scenes of some of his hard-fought battles are the wide valleys closed in by the shadowy hills, and the crags dashed by the tumultuous sea. You may wander at will for miles in any direction still keeping in sight the sturdy granite church standing exposed on the highest bit of the coast; you will hear no sound but the whimpering cry of the gulls; and you will be free to reconstruct here in imagination the vanished realm of King Arthur, while the words of the old priest, Joseph Iscarus of Exeter, ring in your ears

"From this blest place immortal Arthur sprung

Whose wondrous deeds shall be for ever sung,

Sweet music to the ear, sweet honey to the tongue.

The only prince that hears the just applause,

Greatest that e'er shall be, and best that ever was."