|

|

[See: The Mabinogion Translated by Lady Charlotte Guest]

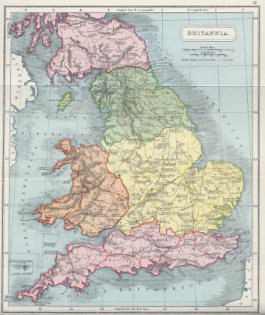

THE earliest inhabitants of Britain are supposed to have been a branch of that great family known in history by the designation of Celts. Cambria, which is a frequent name for Wales, is thought to be derived from Cymri, the name which the Welsh traditions apply to an immigrant people who entered the island from the adjacent continent. This name is thought to be identical with those of Cimmerians and Cimbri, under which the Greek and Roman historians describe a barbarous people, who spread themselves from the north of the Euxine over the whole of Northwestern Europe.

[See: The Origin of the English from Anglo-Saxon Britain By Grant Allen]

[See: History of the English People by John Richard]

The origin of the names Wales and Welsh has been much canvassed. Some writers make them a derivation from Gael or Gaul, which names are said to signify “woodlanders”; others observe that Walsh, in the Northern languages, signifies a stranger, and that the aboriginal Britons were so called by those who at a later era invaded the island and possessed the greater part of it, the Saxons and Angles.

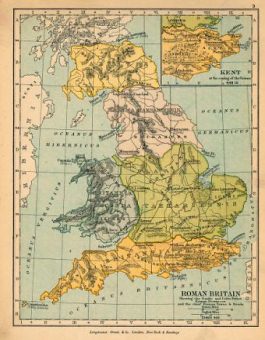

The Romans held Britain from the invasion of Julius Caesar till their voluntary withdrawal from the island, A.D. 420,– that is, about five hundred years. In that time there must have been a wide diffusion of their arts and institutions among the natives. The remains of roads, cities, and fortifications show that they did much to develop and improve the country, while those of their villas and castles prove that many of the settlers possessed wealth and taste for the ornamental arts. Yet the Roman sway was sustained chiefly by force, and never extended over the entire island. The northern portion, now Scotland, remained independent, and the western portion, constituting Wales and Cornwall, was only nominally subjected.

[See: Early Britain--Roman Britain, by Edward Conybeare]

Neither did the later invading hordes succeed in subduing the remoter sections of the island. For ages after the arrival of the Saxons under Hengist and Horsa, A.D. 449, the whole western coast of Britain was possessed by the aboriginal inhabitants, engaged in constant warfare with the invaders.

[See: A Battle between Aurelius and Hengist from History of the Kings of Britain by Geoffrey of Monmouth]

It has, therefore, been a favorite boast of the people of Wales and Cornwall, that the original British stock flourishes in its unmixed purity only among them. We see this notion flashing out in poetry occasionally, as when Gray, in “The Bard,” prophetically describing Queen Elizabeth, who was of the Tudor, a Welsh race, says:

“Her eye proclaims her of the Briton line”;

and, contrasting the princes of the Tudor with those of the Norman race, he exclaims:

“All hail, ye genuine kings, Britannia’s issue, hail!”

[See: Wild Wales, Its People, Language and Scenery by George Borrow]

The Welsh language is one of the oldest in Europe. It possesses poems the origin of which is referred with probability to the sixth century. The language of some of these is so antiquated, that the best scholars differ about the interpretation of many passages; but, generally speaking, the body of poetry which the Welsh possess, from the year 1000 downwards, is intelligible to those who are acquainted with the modern language.

Till within the last half–century these compositions remained buried in the libraries of colleges or of individuals, and so difficult of access that no successful attempt was made to give them to the world. This reproach was removed, after ineffectual appeals to the patriotism of the gentry of Wales, by Owen Jones, a furrier of London, who at his own expense collected and published the chief productions of Welsh literature, under the title of the Myvyrian Archaeology of Wales. In this task he was assisted by Dr. Owen and other Welsh scholars.

After the cessation of Jones’s exertions, the old apathy returned, and continued till within a few years. Dr. Owen exerted himself to obtain support for the publication of the Mabinogeon, or Prose Tales of the Welsh, but died without accomplishing his purpose, which has since been carried into execution by Lady Charlotte Guest. The legends which fill the remainder of this volume are taken from this work, of which we have already spoken more fully in the introductory chapter to the First Part.

The authors to whom the oldest Welsh poems are attributed are Aneurin, who is supposed to have lived A.D. 500 and 550, and Taliesin, Llywarch Hen (Llywarch the Aged), and Myrddin or Merlin, who were a few years later. The authenticity of the poems which bear their names has been assailed, and it is still an open question how many and which of them are authentic, though it is hardly to be doubted that some are so. The poem of Aneurin, entitled the “Gododin,” bears very strong marks of authenticity. Aneurin was one of the Northern Britons of Strath–Clyde, who have left to that part of the district they inhabited the name of Cumberland, or Land of the Cymri. In this poem he laments the defeat of his countrymen by the Saxons at the battle of Cattraeth, in consequence of having partaken too freely of the mead before joining in combat. The bard himself and two of his fellow–warriors were all who escaped from the field. A portion of this poem has been translated by Gray, of which the following is an extract:–

The Death Of Hoel1

Had I but the torrent's might,

With headlong rage, and wild affright,

Upon Deira's2 squadrons hurl'd,

To rush and sweep them from the world!

Too, too secure in youthful pride,

By them my friend, my Hoel, died,

Great Cian's son; of Madoc old

He ask'd no heaps of hoarded gold;

Alone in Nature's wealth array'd,

He ask'd and had the lovely maid.“To Cattraeth’s vale, in glittering row,

Twice two hundred warriors go;

Every warrior’s manly neck

Chains of regal honor deck,

Wreathed in many a golden link;

From the golden cup they drink

Nectar that the bees produce,

Or the grape’s exalted juice.

Flushed with mirth and hope they burn,

But none to Cattraeth’s vale return,

Save Aeron brave, and Conan strong,

Bursting through the bloody throng,

And I, the meanest of them all,

That live to weep, and sing their fall.”

1 'Hoel:' from the Welsh of Aneurim, styled 'The Monarch of the Bards.' He flourished about the time of Taliessin, A.D. 570. This ode is extracted from the Gododin.

2 'Deira's:' a kingdom including the five northernmost counties of England.[See: Y Gododin By Aneurin]

The works of Taliesin are of much more questionable authenticity. There is a story of the adventures of Taliesin so strongly marked with mythical traits as to cast suspicion on the writings attributed to him. This story will be found in the subsequent pages.

[See: Triads of Britain by Iolo Morganwg

The Triads are a peculiar species of poetical composition, of which the Welsh bards have left numerous examples. They are enumerations of a triad of persons, or events, or observations, strung together in one short sentence. This form of composition, originally invented, in all likelihood, to assist the memory, has been raised by the Welsh to a degree of elegance of which it hardly at first sight appears susceptible. The Triads are of all ages, some of them probably as old as anything in the language. Short as they are individually, the collection in the Myvyrian Archaeology occupies more than one hundred and seventy pages of double columns. We will give some specimens, beginning with personal triads, and giving the first place to one of King Arthur’s own composition:–

“I have three heroes in battle;

Mael the tall, and Llyr, with his army,

And Caradoc, the pillar of Wales.”“The three principal bards of the island of Britain:-

Merlin Ambrose

Merlin the son of Morfyn, called also Merlin the Wild,

And Taliesin, the chief of the bards.”“The three golden-tongued knights of the Court of Arthur:-

Gawain, son of Gwyar,

Drydvas, son of Tryphin,

And Eliwood, son of Madag, ap Uther.”“The three honorable feasts of the island of Britain:–

The feast of Caswallaun, after repelling Julius Caesar from this isle;

The feast of Aurelius Ambrosius, after he had conquered the Saxons;

And the feast of King Arthur, at Caerleon upon Usk.”“Guenever, the daughter of Laodegan the giant,

Bad when little, worse when great.”

Next follow some moral triads:–

“Hast thou heard what Dremhidydd sung,

An ancient watchman on the castle walls?

A refusal is better than a promise unperformed.”“Hast thou heard what Llenleawg sung,

The noble chief wearing the golden torques?

The grave is better than a life of want.”“Hast thou heard what Garselit sung,

The Irishman whom it is safe to follow?

Sin is bad, if long pursued.”“Hast thou heard what Avaon sung,

The son of Taliesin, of the recording verse?

The cheek will not conceal the anguish of the heart.”“Didst thou hear what Llywarch sung,

The intrepid and brave old man?

Greet kindly, though there be no acquaintance.”