Ancient Art and Ritual, by Jane Harrison

170CHAPTER VI

GREEK SCULPTURE: THE PANATHENAIC FRIEZE AND THE APOLLO BELVEDERE

In passing from the drama to Sculpture we make a great leap. We pass from the living thing, the dance or the play acted by real people, the thing done, whether as ritual or art, whether dromenon or drama, to the thing made, cast in outside material rigid form, a thing that can be looked at again and again, but the making of which can never actually be re-lived whether by artist or spectator.

Moreover, we come to a clear threefold distinction and division hitherto neglected. We must at last sharply differentiate the artist, the work of art, and the spectator. The artist may, and usually indeed does, become the spectator of his own work, but the spectator is not the artist. The work of art is, once executed, forever distinct both from artist and spectator. In the primitive choral dance all three—artist, work of art, spectator—were 171fused, or rather not yet differentiated. Handbooks on art are apt to begin with the discussion of rude decorative patterns, and after leading up through sculpture and painting, something vague is said at the end about the primitiveness of the ritual dance. But historically and also genetically or logically the dance in its inchoateness, its undifferentiatedness, comes first. It has in it a larger element of emotion, and less of presentation. It is this inchoateness, this undifferentiatedness, that, apart from historical fact, makes us feel sure that logically the dance is primitive.

To illustrate the meaning of Greek sculpture and show its close affinity with ritual, we shall take two instances, perhaps the best-known of those that survive, one of them in relief, the other in the round, the Panathenaic frieze of the Parthenon at Athens and the Apollo Belvedere, and we shall take them in chronological order. As the actual frieze and the statue cannot be before us, we shall discuss no technical questions of style or treatment, but simply ask how they came to be, what human need do they express. The Parthenon frieze is in the British Museum, the Apollo172 Belvedere is in the Vatican at Rome, but is readily accessible in casts or photographs. The outlines given in Figs. 5 and 6 can of course only serve to recall subject-matter and design.

The Panathenaic frieze once decorated the cella or innermost shrine of the Parthenon, the temple of the Maiden Goddess Athena. It twined like a ribbon round the brow of the building and thence it was torn by Lord Elgin and brought home to the British Museum as a national trophy, for the price of a few hundred pounds of coffee and yards of scarlet cloth. To realize its meaning we must always think it back into its place. Inside the cella, or shrine, dwelt the goddess herself, her great image in gold and ivory; outside the shrine was sculptured her worship by the whole of her people. For the frieze is nothing but a great ritual procession translated into stone, the Panathenaic procession, or procession of all the Athenians, of all Athens, in honour of the goddess who was but the city incarnate, Athena.

“A wonder enthroned on the hills and the sea,

A maiden crowned with a fourfold glory,

173 That none from the pride of her head may rend;

Violet and olive leaf, purple and hoary,

Song-wreath and story the fairest of fame,

Flowers that the winter can blast not nor bend,

A light upon earth as the sun’s own flame,

A name as his name—

Athens, a praise without end.”

Swinburne: Erechtheus, 141.

Sculptural Art, at least in this instance, comes out of ritual, has ritual as its subject, is embodied ritual. The reader perhaps at this point may suspect that he is being juggled with, that, out of the thousands of Greek reliefs that remain to us, just this one instance has been selected to bolster up the writer’s art and ritual theory. He has only to walk through any museum to be convinced at once that the author is playing quite fair. Practically the whole of the reliefs that remain to us from the archaic period, and a very large proportion of those at later date, when they do not represent heroic mythology, are ritual reliefs, “votive” reliefs as we call them; that is, prayers or praises translated into stone.

Fig. 3.

Of the choral dance we have heard much, of the procession but little, yet its ritual importance was great. In religion to-day the dance is dead save for the dance of the choristers before the altar at Seville. But the procession lives on, has even taken to itself new life. It is a means of bringing masses of people together, of ordering them and co-ordinating them. It is a means for the magical spread of supposed good influence, of “grace.” Witness the “Beating of the Bounds” and the frequent processions of the Blessed Sacrament in Roman Catholic lands.175 The Queen of the May and the Jack-in-the-Green still go from house to house. Now-a-days it is to collect pence; once it was to diffuse “grace” and increase. We remember the procession of the holy Bull at Magnesia and the holy Bear at Saghalien.

176What, then, was the object of the Panathenaic procession? It was first, as its name indicates, a procession that brought all Athens together. Its object was social and political, to express the unity of Athens. Ritual in primitive times is always social, collective.

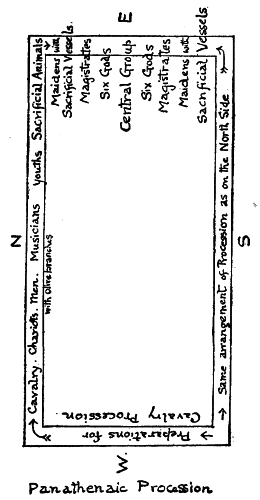

The arrangement of the procession is shown in Figs. 3 and 4 (pp. 174, 175). In Fig. 3 we see the procession as it were in real life, just as it is about to enter the temple and the presence of the Twelve Gods. These gods are shaded black because in reality invisible. Fig. 4 is a diagram showing the position of the various parts of the procession in the sculptural frieze. At the west end of the temple the procession begins to form: the youths of Athens are mounting their horses. It divides, as it needs must, into two halves, one sculptured on the north, one on the south side of the cella. After the throng of the cavalry getting denser and denser we come to the chariots, next the sacrificial animals, sheep and restive cows, then the instruments of sacrifice, flutes and lyres and baskets and trays for offerings; men who carry blossoming olive-boughs; maidens with water-vessels and drinking-cups. The whole 177tumult of the gathering is marshalled and at last met and, as it were, held in check, by a band of magistrates who face the procession just as it enters the presence of the twelve seated gods, at the east end. The whole body politic of the gods has come down to feast with the whole body politic of Athens and her allies, of whom these gods are but the projection and reflection. The gods are there together because man is collectively assembled.

The great procession culminates in a sacrifice and a communal feast, a sacramental feast like that on the flesh of the holy Bull at Magnesia. The Panathenaia was a high festival including rites and ceremonies of diverse dates, an armed dance of immemorial antiquity that may have dated from the days when Athens was subject to Crete, and a recitation ordered by Peisistratos of the poems of Homer.

Some theorists have seen in art only an extension of the “play instinct,” just a liberation of superfluous vitality and energies, as it were a rehearsing for life. This is not our view, but into all art, in so far as it is a cutting off of motor reactions, there certainly enters an element of recreation. It is interesting 178to note that to the Greek mind religion was specially connected with the notion rather of a festival than a fast. Thucydides43 is assuredly by nature no reveller, yet religion is to him mainly a “rest from toil.” He makes Perikles say: “Moreover, we have provided for our spirit by many opportunities of recreation, by the celebration of games and sacrifices throughout the year.” To the anonymous writer known as the “Old Oligarch” the main gist of religion appears to be a decorous social enjoyment. In easy aristocratic fashion he rejoices that religious ceremonials exist to provide for the less well-to-do citizens suitable amusements that they would otherwise lack. “As to sacrifices and sanctuaries and festivals and precincts, the People, knowing that it is impossible for each man individually to sacrifice and feast and have sacrifices and an ample and beautiful city, has discovered by what means he may enjoy these privileges.”

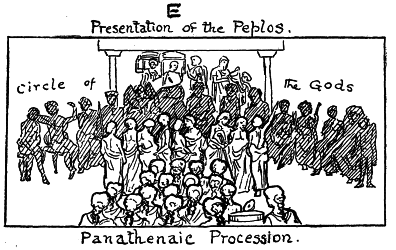

In the procession of the Panathenaia all Athens was gathered together, but—and this is important—for a special purpose, more 179primitive than any great political or social union. Happily this purpose is clear; it is depicted in the central slab of the east end of the frieze (Fig. 5). A priest is there represented receiving from the hands of a boy a great peplos or robe. It is the sacred robe of Athena woven for her and embroidered by young Athenian maidens and offered to her every five years. The great gold and ivory statue in the Parthenon itself had no need of a robe; she would scarcely have known what to do with one; her raiment was already of wrought gold, she carried helmet and spear and shield. But there was an ancient image of Athena, an old Madonna of the people, fashioned before Athena became a warrior maiden. This image was rudely hewn in wood, it was dressed and decked doll-fashion 180like a May Queen, and to her the great peplos was dedicated. The peplos was hoisted as a sail on the Panathenaic ship, and this ship Athena had borrowed from Dionysos himself, who went every spring in procession in a ship-car on wheels to open the season for sailing. To a seafaring people like the Athenians the opening of the sailing season was all-important, and naturally began not at midsummer but in spring.

Fig. 5.

The sacred peplos, or robe, takes us back to the old days when the spirit of the year and the “luck” of the people was bound up with a rude image. The life of the year died out each year and had to be renewed. To make a new image was expensive and inconvenient, so, with primitive economy it was decided that the life and luck of the image should be renewed by re-dressing it, by offering to it each year a new robe. We remember how in Thuringia the new puppet wore the shirt of the old and thereby new life was passed from one to the other. But behind the old image we can get to a stage still earlier, when there was at the Panathenaia no image at all, only a yearly maypole; a bough hung with ribbons and 181cakes and fruits and the like. A bough was cut from the sacred olive tree of Athens, called the Moria or Fate Tree. It was bound about with fillets and hung with fruit and nuts and, in the festival of the Panathenaia, they carried it up to the Acropolis to give to Athena Polias, “Her-of-the-City,” and as they went they sang the old Eiresione song (p. 114). Polias is but the city, the Polis incarnate.

This Moria, or Fate Tree, was the very life of Athens; the life of the olive which fed her and lighted her was the very life of the city. When the Persian host sacked the Acropolis they burnt the holy olive, and it seemed that all was over. But next day it put forth a new shoot and the people knew that the city’s life still lived. Sophocles44 sang of the glory of the wondrous life tree of Athens:

“The untended, the self-planted, self-defended from the foe,

Sea-gray, children-nurturing olive tree that here delights to grow,

None may take nor touch nor harm it, headstrong youth nor age grown bold.

182 For the round of Morian Zeus has been its watcher from of old;

He beholds it, and, Athene, thy own sea-gray eyes behold.”

The holy tree carried in procession is, like the image of Athena, made of olive-wood, just the incarnate life of Athens ever renewed.

The Panathenaia was not, like the Dithyramb, a spring festival. It took place in July at the height of the summer heat, when need for rain was the greatest. But the month Hecatombaion, in which it was celebrated, was the first month of the Athenian year and the day of the festival was the birthday of the goddess. When the goddess became a war-goddess, it was fabled that she was born in Olympus, and that she sprang full grown from her father’s head in glittering armour. But she was really born on earth, and the day of her birth was the birthday of every earthborn goddess, the day of the beginning of the new year, with its returning life. When men observe only the actual growth of new green life from the ground, this birthday will be in spring; when they begin to know that the seasons depend on 183the sun, or when the heat of the sun causes great need of rain, it will be at midsummer, at the solstice, or in northern regions where men fear to lose the sun in midwinter, as with us. The frieze of the Parthenon is, then, but a primitive festival translated into stone, a rite frozen to a monument.

Passing over a long space of time we come to our next illustration, the Apollo Belvedere (Fig. 6).

It might seem that here at last we have nothing primitive; here we have art pure and simple, ideal art utterly cut loose from ritual, “art for art’s sake.” Yet in this Apollo Belvedere, this product of late and accomplished, even decadent art, we shall see most clearly the intimate relation of art and ritual; we shall, as it were, walk actually across that transition bridge of ritual which leads from actual life to art.

The date of this famous Apollo cannot be fixed, but it is clearly a copy of a type belonging to the fourth century B.C. The poise of the figure is singular and, till its intent is grasped, unsatisfactory. Apollo is caught in swift motion but seems, as he stands delicately poised, to be about to fly rather than to run.185 He stands tiptoe and in a moment will have left the earth. The Greek sculptor’s genius was all focussed, as we shall presently see, on the human figure and on the mastery of its many possibilities of movement and action. Greek statues can roughly be dated by the way they stand. At first, in the archaic period, they stand firmly planted with equal weight on either foot, the feet close together. Then one foot is advanced, but the weight still equally divided, an almost impossible position. Next, the weight is thrown on the right foot; and the left knee is bent. This is of all positions the loveliest for the human body. We allow it to women, forbid it to men save to “æsthetes.” If the back numbers of Punch be examined for the figure of “Postlethwaite” it will be seen that he always stands in this characteristic relaxed pose.

When the sculptor has mastered the possible he bethinks him of the impossible. He will render the human body flying. It may have been the accident of a mythological subject that first suggested the motive. Leochares, a famous artist of the fourth century B.C., made a group of Zeus in the form of an eagle carrying off Ganymede. A replica of the 186group is preserved in the Vatican, and should stand for comparison near the Apollo. We have the same tiptoe poise, the figure just about to leave the earth. Again, it is not a dance, but a flight. This poise is suggestive to us because it marks an art cut loose, as far as may be, from earth and its realities, even its rituals.

What is it that Apollo is doing? The question and suggested answers have occupied many treatises. There is only one answer: We do not know. It was at first thought that the Apollo had just drawn his bow and shot an arrow. This suggestion was made to account for the pose; but that, as we have seen, is sufficiently explained by the flight-motive. Another possible solution is that Apollo brandishes in his uplifted hand the ægis, or goatskin shield, of Zeus. Another suggestion is that he holds as often a lustral, or laurel bough, that he is figured as Daphnephoros, “Laurel-Bearer.”

We do not know if the Belvedere Apollo carried a laurel, but we do know that it was of the very essence of the god to be a Laurel-Bearer. That, as we shall see in a moment, he, like Dionysos, arose in part out of a rite, 187a rite of Laurel-Bearing—a Daphnephoria. We have not got clear of ritual yet. When Pausanias,45 the ancient traveller, whose notebook is our chief source about these early festivals, came to Thebes he saw a hill sacred to Apollo, and after describing the temple on the hill he says:

“The following custom is still, I know, observed at Thebes. A boy of distinguished family and himself well-looking and strong is made the priest of Apollo, for the space of a year. The title given him is Laurel-Bearer (Daphnephoros), for these boys wear wreaths made of laurel.”

We know for certain now what these yearly priests are: they are the Kings of the Year, the Spirits of the Year, May-Kings, Jacks-o’-the-Green. The name given to the boy is enough to show he carried a laurel branch, though Pausanias only mentions a wreath. Another ancient writer gives us more details.46 He says in describing the festival of the Laurel-Bearing:

“They wreathe a pole of olive wood with laurel and various flowers. On the top is 188fitted a bronze globe from which they suspend smaller ones. Midway round the pole they place a lesser globe, binding it with purple fillets, but the end of the pole is decked with saffron. By the topmost globe they mean the sun, to which they actually compare Apollo. The globe beneath this is the moon; the smaller globes hung on are the stars and constellations, and the fillets are the course of the year, for they make them 365 in number. The Daphnephoria is headed by a boy, both whose parents are alive, and his nearest male relation carries the filleted pole. The Laurel-Bearer himself, who follows next, holds on to the laurel; he has his hair hanging loose, he wears a golden wreath, and he is dressed out in a splendid robe to his feet and he wears light shoes. There follows him a band of maidens holding out boughs before them, to enforce the supplication of the hymns.”

This is the most elaborate maypole ceremony that we know of in ancient times. The globes representing sun and moon show us that we have come to a time when men know that the fruits of the earth in due season depended on the heavenly bodies. The year 189with its 365 days is a Sun-Year. Once this Sun-Year established and we find that the times of the solstices, midwinter and midsummer became as, or even more, important than the spring itself. The date of the Daphnephoria is not known.

At Delphi itself, the centre of Apollo-worship, there was a festival called the Stepteria, or festival “of those who make the wreathes,” in which “mystery” a Christian Bishop, St. Cyprian, tells us he was initiated. In far-off Tempe—that wonderful valley that is still the greenest spot in stony, barren Greece, and where the laurel trees still cluster—there was an altar, and near it a laurel tree. The story went that Apollo had made himself a crown from this very laurel, and taking in his hand a branch of this same laurel, i.e. as Laurel-Bearer, had come to Delphi and taken over the oracle.

“And to this day the people of Delphi send high-born boys in procession there. And they, when they have reached Tempe and made a splendid sacrifice return back, after wearing themselves wreaths from the very laurel from which the god made himself a wreath.”

190We are inclined to think of the Greeks as a people apt to indulge in the singular practice of wearing wreaths in public, a practice among us confined to children on their birthdays and a few eccentric people on their wedding days. We forget the intensely practical purport of the custom. The ancient Greeks wore wreaths and carried boughs, not because they were artistic or poetical, but because they were ritualists, that they might bring back the spring and carry in the summer. The Greek bridegroom to-day, as well as the Greek bride, wears a wreath, that his marriage may be the beginning of new life, that his “wife may be as the fruitful vine, and his children as the olive branches round about his table.” And our children to-day, though they do not know it, wear wreaths on their birthdays because with each new year their life is re-born.

Apollo then, was, like Dionysos, King of the May and—saving his presence—Jack-in-the-Green. The god manifestly arose out of the rite. For a moment let us see how he arose. It will be remembered that in a previous chapter we spoke of “personification.”191 We think of the god Apollo as an abstraction, an unreal thing, perhaps as a “false god.” The god Apollo does not, and never did, exist. He is an idea—a thing made by the imagination. But primitive man does not deal with abstractions, does not worship them. What happens is, as we saw something like this: Year by year a boy is chosen to carry the laurel, to bring in the May, and later year by year a puppet is made. It is a different boy each year, carrying a different laurel branch. And yet in a sense it is the same boy; he is always the Laurel-Bearer—“Daphnephoros,” always the “Luck” of the village or city. This Laurel-Bearer, the same yesterday, to-day, and forever, is the stuff of which the god is made. The god arises from the rite, he is gradually detached from the rite, and as soon as he gets a life and being of his own, apart from the rite, he is a first stage in art, a work of art existing in the mind, gradually detached from even the faded action of ritual, and later to be the model of the actual work of art, the copy in stone.

The stages, it would seem, are: actual life with its motor reactions, the ritual copy of life with its faded reactions, the image of the 192god projected by the rite, and, last, the copy of that image, the work of art.

We see now why in the history of all ages and every place art is what is called the “handmaid of religion.” She is not really the “handmaid” at all. She springs straight out of the rite, and her first outward leap is the image of the god. Primitive art in Greece, in Egypt, in Assyria,47 represents either rites, processions, sacrifices, magical ceremonies, embodied prayers; or else it represents the images of the gods who spring from those rites. Track any god right home, and you will find him lurking in a ritual sheath, from which he slowly emerges, first as a dæmon, or spirit, of the year, then as a full-blown divinity.

In Chapter II we saw how the dromenon gave birth to the drama, how, bit by bit, out of the chorus of dancers some dancers with193drew and became spectators sitting apart, and on the other hand others of the dancers drew apart on to the stage and presented to the spectators a spectacle, a thing to be looked at, not joined in. And we saw how in this spectacular mood, this being cut loose from immediate action, lay the very essence of the artist and the art-lover. Now in the drama of Thespis there was at first, we are told, but one actor; later Æschylus added a second. It is clear who this actor, this protagonist or “first contender” was, the one actor with the double part, who was Death to be carried out and Summer to be carried in. He was the Bough-Bearer, the only possible actor in the one-part play of the renewal of life and the return of the year.

The May-King, the leader of the choral dance gave birth not only to the first actor of the drama, but also, as we have just seen, to the god, be he Dionysos or be he Apollo; and this figure of the god thus imagined out of the year-spirit was perhaps more fertile for art than even the protagonist of the drama. It may seem strange to us that a god should rise up out of a dance or a pro194cession, because dances and processions are not an integral part of our national life, and do not call up any very strong and instant emotion. The old instinct lingers, it is true, and emerges at critical moments; when a king dies we form a great procession to carry him to the grave, but we do not dance. We have court balls, and these with their stately ordered ceremonials are perhaps the last survival of the genuinely civic dance, but a court ball is not given at a king’s funeral nor in honour of a god.

But to the Greek the god and the dance were never quite sundered. It almost seems as if in the minds of Greek poets and philosophers there lingered some dim half-conscious remembrance that some of these gods at least actually came out of the ritual dance. Thus, Plato,48 in treating of the importance of rhythm in education says: “The gods, pitying the toilsome race of men, have appointed the sequence of religious festivals to give them times of rest, and have given them the Muses and Apollo, the Muse-Leader, as fellow-revellers.”

“The young of all animals,” he goes on to 195say, “cannot keep quiet, either in body or voice. They must leap and skip and overflow with gamesomeness and sheer joy, and they must utter all sorts of cries. But whereas animals have no perception of order or disorder in their motions, the gods who have been appointed to men as our fellow-dancers have given to us a sense of pleasure in rhythm and harmony. And so they move us and lead our bands, knitting us together with songs and in dances, and these we call choruses.” Nor was it only Apollo and Dionysos who led the dance. Athena herself danced the Pyrrhic dance. “Our virgin lady,” says Plato, “delighting in the sports of the dance, thought it not meet to dance with empty hands; she must be clothed in full armour, and in this attire go through the dance. And youths and maidens should in every respect imitate her example, honouring the goddess, both with a view to the actual necessities of war and to the festivals.”

Plato is unconsciously inverting the order of things, natural happenings. Take the armed dance. There is, first, the “actual necessity of war.” Men go to war armed, to 196face actual dangers, and at their head is a leader in full armour. That is real life. There is then the festal re-enactment of war, when the fight is not actually fought, but there is an imitation of war. That is the ritual stage, the dromenon. Here, too, there is a leader. More and more this dance becomes a spectacle, less and less an action. Then from the periodic dromenon, the ritual enacted year by year, emerges an imagined permanent leader; a dæmon, or god—a Dionysos, an Apollo, an Athena. Finally the account of what actually happens is thrown into the past, into a remote distance, and we have an “ætiological” myth—a story told to give a cause or reason. The whole natural process is inverted.

And last, as already seen, the god, the first work of art, the thing unseen, imagined out of the ritual of the dance, is cast back into the visible world and fixed in space. Can we wonder that a classical writer49 should say “the statues of the craftsmen of old times are the relics of ancient dancing.” That is just what they are, rites caught and fixed and frozen. “Drawing,” says a modern 197critic,50 “is at bottom, like all the arts, a kind of gesture, a method of dancing on paper.” Sculpture, drawing, all the arts save music are imitative; so was the dance from which they sprang. But imitation is not all, or even first. “The dance may be mimetic; but the beauty and verve of the performance, not closeness of the imitation impresses; and tame additions of truth will encumber and not convince. The dance must control the pantomime.” Art, that is, gradually dominates mere ritual.

We come to another point. The Greek gods as we know them in classical sculpture are always imaged in human shape. This was not of course always the case with other nations. We have seen how among savages the totem, that is, the emblem of tribal unity, was usually an animal or a plant. We have seen how the emotions of the Siberian tribe in Saghalien focussed on a bear. The savage totem, the Saghalien Bear, is on the way to be, but is not quite, a god; he is not personal enough. The Egyptians, and in 198part the Assyrians, halted half-way and made their gods into monstrous shapes, half-animal, half-man, which have their own mystical grandeur. But since we are men ourselves, feeling human emotion, if our gods are in great part projected emotions, the natural form for them to take is human shape.

“Art imitates Nature,” says Aristotle, in a phrase that has been much misunderstood. It has been taken to mean that art is a copy or reproduction of natural objects. But by “Nature” Aristotle never means the outside world of created things, he means rather creative force, what produces, not what has been produced. We might almost translate the Greek phrase, “Art, like Nature, creates things,” “Art acts like Nature in producing things.” These things are, first and foremost, human things, human action. The drama, with which Aristotle is so much concerned, invents human action like real, natural action. Dancing “imitates character, emotion, action.” Art is to Aristotle almost wholly bound by the limitations of human nature.

This is, of course, characteristically a Greek limitation. “Man is the measure of all 199things,” said the old Greek sophist, but modern science has taught us another lesson. Man may be in the foreground, but the drama of man’s life is acted out for us against a tremendous background of natural happenings: a background that preceded man and will outlast him; and this background profoundly affects our imagination, and hence our art. We moderns are in love with the background. Our art is a landscape art. The ancient landscape painter could not, or would not, trust the background to tell its own tale: if he painted a mountain he set up a mountain-god to make it real; if he outlined a coast he set human coast-nymphs on its shore to make clear the meaning.

Contrast with this our modern landscape, from which bit by bit the nymph has been wholly banished. It is the art of a stage, without actors, a scene which is all background, all suggestion. It is an art given us by sheer recoil from science, which has dwarfed actual human life almost to imaginative extinction.

“Landscape, then, offered to the modern imagination a scene empty of definite actors, 200superhuman or human, that yielded to reverie without challenge all that is in a moral without a creed, tension or ambush of the dark, threat of ominous gloom, the relenting and tender return or overwhelming outburst of light, the pageantry of clouds above a world turned quaker, the monstrous weeds of trees outside the town, the sea that is obstinately epic still.”51

It was to this world of backgrounds that men fled, hunted by the sense of their own insignificance.

“Minds the most strictly bound in their acts by civil life, in their fancy by the shrivelled look of destiny under scientific speculation, felt on solitary hill or shore those tides of the blood stir again that are ruled by the sun and the moon and travelled as if to tryst where an apparition might take form. Poets ordained themselves to this vigil, haunters of a desert church, prompters of an elemental theatre, listeners in solitary places for intimations from a spirit in hiding; and painters followed the impulse of Wordsworth.”

201We can only see the strength and weakness of Greek sculpture, feel the emotion of which it was the utterance, if we realize clearly this modern spirit of the background. All great modern, and perhaps even ancient, poets are touched by it. Drama itself, as Nietzsche showed, “hankers after dissolution into mystery. Shakespeare would occasionally knock the back out of the stage with a window opening on the ‘cloud-capp’d towers.’” But Maeterlinck is the best example, because his genius is less. He is the embodiment, almost the caricature, of a tendency.

“Maeterlinck sets us figures in the foreground only to launch us into that limbus. The supers jabbering on the scene are there, children of presentiment and fear, to make us aware of a third, the mysterious one, whose name is not on the bills. They come to warn us by the nervous check and hurry of their gossip of the approach of that background power. Omen after omen announces him, the talk starts and drops at his approach, a door shuts and the thrill of his passage is the play.”52

202It is, perhaps, the temperaments that are most allured and terrified by this art of the bogey and the background that most feel the need of and best appreciate the calm and level, rational dignity of Greek naturalism and especially the naturalism of Greek sculpture.

For it is naturalism, not realism, not imitation. By all manner of renunciations Greek sculpture is what it is. The material, itself marble, is utterly unlike life, it is perfectly cold and still, it has neither the texture nor the colouring of life. The story of Pygmalion who fell in love with the statue he had himself sculptured is as false as it is tasteless. Greek sculpture is the last form of art to incite physical reaction. It is remote almost to the point of chill abstraction. The statue in the round renounces not only human life itself, but all the natural background and setting of life. The statues of the Greek gods are Olympian in spirit as well as subject. They are like the gods of Epicurus, cut loose alike from the affairs of men, and even the ordered ways of Nature. So Lucretius53 pictures them:

203“The divinity of the gods is revealed and their tranquil abodes, which neither winds do shake nor clouds drench with rains, nor snow congealed by sharp frost harms with hoary fall: an ever cloudless ether o’ercanopies them, and they laugh with light shed largely around. Nature, too, supplies all their wants, and nothing ever impairs their peace of mind.”

Greek art moves on through a long course of technical accomplishment, of ever-increasing mastery over materials and methods. But this course we need not follow. For our argument the last word is said in the figures of these Olympians translated into stone. Born of pressing human needs and desires, images projected by active and even anxious ritual, they pass into the upper air and dwell aloof, spectator-like and all but spectral.

43 II, 38.

44 Oed. Col. 694, trans. D.S. MacColl.

45 IX, 10, 4.

46 See my Themis, p. 438.

47 It is now held by some and good authorities that the prehistoric paintings of cave-dwelling man had also a ritual origin; that is, that the representations of animals were intended to act magically, to increase the “supply of the animal or help the hunter to catch him.” But, as this question is still pending, I prefer, tempting though they are, not to use prehistoric paintings as material for my argument.

48 Laws, 653.

49 Athen. XIV, 26, p. 629.

50 D.S. MacColl, “A Year of Post-Impressionism,” Nineteenth Century, p. 29. (1912.)

51 D.S. MacColl, Nineteenth Century Art, p. 20. (1902.)

52 D.S. MacColl, op. cit., p. 18.

53 II, 18.