Ancient Art and Ritual, by Jane Harrison

119CHAPTER V

TRANSITION FROM RITUAL TO ART:

THE DROMENON (“THING DONE”) AND THE DRAMA

Probably most people when they go to a Greek play for the first time think it a strange performance. According, perhaps, more to their temperament than to their training, they are either very much excited or very much bored. In many minds there will be left a feeling that, whether they have enjoyed the play or not, they are puzzled: there are odd effects, conventions, suggestions.

For example, the main deed of the Tragedy, the slaying of hero or heroine, is not done on the stage. That disappoints some modern minds unconsciously avid of realism to the point of horror. Instead of a fine thrilling murder or suicide before his very eyes, the spectator is put off with an account of the murder done off the stage. This account is regularly given, and usually at considerable 120length, in a “messenger’s speech.” The messenger’s speech is a regular item in a Greek play, and though actually it gives scope not only for fine elocution, but for real dramatic effect, in theory we feel it undramatic, and a modern actor has sometimes much ado to make it acceptable. The spectator is told that all these, to him, odd conventions are due to Greek restraint, moderation, good taste, and yet for all their supposed restraint and reserve, he finds when he reads his Homer that Greek heroes frequently burst into floods of tears when a self-respecting Englishman would have suffered in silence.

Then again, specially if the play be by Euripides, it ends not with a “curtain,” not with a great decisive moment, but with the appearance of a god who says a few lines of either exhortation or consolation or reconciliation, which, after the strain and stress of the action itself, strikes some people as rather stilted and formal, or as rather flat and somehow unsatisfying. Worse still, there are in many of the scenes long dialogues, in which the actors wrangle with each other, and in which the action does not advance so quickly as we wish. Or again, instead of 121beginning with the action, and having our curiosity excited bit by bit about the plot, at the outset some one comes in and tells us the whole thing in the prologue. Prologues we feel, are out of date, and the Greeks ought to have known better. Or again, of course we admit that tragedy must be tragic, and we are prepared for a decent amount of lamentation, but when an antiphonal lament goes on for pages, we weary and wish that the chorus would stop lamenting and do something.

At the back of our modern discontent there is lurking always this queer anomaly of the chorus. We have in our modern theatre no chorus, and when, in the opera, something of the nature of a chorus appears in the ballet, it is a chorus that really dances to amuse and excite us in the intervals of operatic action; it is not a chorus of doddering and pottering old men, moralizing on an action in which they are too feeble to join. Of course if we are classical scholars we do not cavil at the choral songs; the extreme difficulty of scanning and construing them alone commands a traditional respect; but if we are merely modern spectators, we may be respectful, we may even feel strangely excited, but we are certainly puzzled. The reason of our bewilderment is simple enough. 122These prologues and messengers’ speeches and ever-present choruses that trouble us are ritual forms still surviving at a time when the drama has fully developed out of the dromenon. We cannot here examine all these ritual forms in detail;35 one, however, the chorus, strangest and most beautiful of all, it is essential we should understand.

Suppose that these choral songs have been put into English that in any way represents the beauty of the Greek; then certainly there will be some among the spectators who get a thrill from the chorus quite unknown to any modern stage effect, a feeling of emotion heightened yet restrained, a sense of entering into higher places, filled with a larger and a purer air—a sense of beauty born clean out of conflict and disaster.

A suspicion dawns upon the spectator that, great though the tragedies in themselves are, they owe their peculiar, their incommunicable beauty largely to this element of the chorus which seemed at first so strange.

123Now by examining this chorus and understanding its function—nay, more, by considering the actual orchestra, the space on which the chorus danced, and the relation of that space to the rest of the theatre, to the stage and the place where the spectators sat—we shall get light at last on our main central problem: How did art arise out of ritual, and what is the relation of both to that actual life from which both art and ritual sprang?

The dramas of Æschylus certainly, and perhaps also those of Sophocles and Euripides, were played not upon the stage, and not in the theatre, but, strange though it sounds to us, in the orchestra. The theatre to the Greeks was simply “the place of seeing, the place where the spectators sat; what they called the skēnē or scene, was the tent or hut in which the actors dressed. But the kernel and centre of the whole was the orchestra, the circular dancing-place of the chorus; and, as the orchestra was the kernel and centre of the theatre, so the chorus, the band of dancing and singing men—this chorus that seems to us so odd and even superfluous—was the centre and kernel and starting-point of the drama. The chorus 124danced and sang that Dithyramb we know so well, and from the leaders of that Dithyramb we remember tragedy arose, and the chorus were at first, as an ancient writer tells us, just men and boys, tillers of the earth, who danced when they rested from sowing and ploughing.

Now it is in the relation between the orchestra or dancing-place of the chorus, and the theatre or place of the spectators, a relation that shifted as time went on, that we see mirrored the whole development from ritual to art—from dromenon to drama.

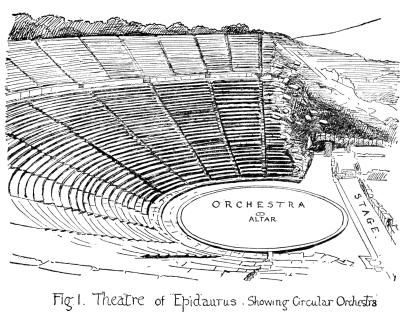

The orchestra on which the Dithyramb was danced was just a circular dancing-place beaten flat for the convenience of the dancers, and sometimes edged by a stone basement to mark the circle. This circular orchestra is very well seen in the theatre of Epidaurus, of which a sketch is given in Fig. 1. The orchestra here is surrounded by a splendid theatron, or spectator place, with seats rising tier above tier. If we want to realize the primitive Greek orchestra or dancing-place, we must think these stone seats away. Threshing-floors are used in Greece to-day as convenient dancing-places. The dance tends to be circular because it is round some sacred thing, at first a maypole, or the reaped corn, later the figure of a god or his altar. On this dancing-place the whole body of worshippers would gather, just as now-a-days the whole community will assemble on a village green. There is no division at first between actors and spectators; all are actors, all are doing the thing done, dancing the dance danced. Thus at initiation ceremonies the whole tribe assembles, the only spectators are the uninitiated, the women and children. No one at this early stage thinks of building a theatre, a spectator place. It is in the common act, the common or collective emotion, that ritual starts. This must never be forgotten.

The most convenient spot for a mere dancing-place is some flat place. But any one who travels through Greece will notice instantly that all the Greek theatres that remain at Athens, at Epidaurus, at Delos, Syracuse, and elsewhere, are built against the side of hills. None of these are very early; the earliest ancient orchestra we have is at Athens. It is a simple stone ring, but it is built against the steep south side of the127 Acropolis. The oldest festival of Dionysos was, as will presently be seen, held in quite another spot, in the agora, or market-place. The reason for moving the dance was that the wooden seats that used to be set up on a sort of “grand stand” in the market-place fell down, and it was seen how safely and comfortably the spectators could be seated on the side of a steep hill.

The spectators are a new and different element, the dance is not only danced, but it is watched from a distance, it is a spectacle; whereas in old days all or nearly all were worshippers acting, now many, indeed most, are spectators, watching, feeling, thinking, not doing. It is in this new attitude of the spectator that we touch on the difference between ritual and art; the dromenon, the thing actually done by yourself has become a drama, a thing also done, but abstracted from your doing. Let us look for a moment at the psychology of the spectator, at his behaviour.

Artists, it is often said, and usually felt, are so unpractical. They are always late for dinner, they forget to post their letters and to return the books or even money that is lent 128them. Art is to most people’s minds a sort of luxury, not a necessity. In but recently bygone days music, drawing, and dancing were no part of a training for ordinary life, they were taught at school as “accomplishments,” paid for as “extras.” Poets on their side equally used to contrast art and life, as though they were things essentially distinct.

“Art is long, and Time is fleeting.”

Now commonplaces such as these, being unconscious utterances of the collective mind, usually contain much truth, and are well worth weighing. Art, we shall show later, is profoundly connected with life; it is nowise superfluous. But, for all that, art, both its creation and its enjoyment, is unpractical. Thanks be to God, life is not limited to the practical.

When we say art is unpractical, we mean that art is cut loose from immediate action. Take a simple instance. A man—or perhaps still better a child—sees a plate of cherries. Through his senses comes the stimulus of the smell of the cherries, and their bright colour urging him, luring him to eat. He eats and is satisfied; the cycle of normal behaviour is 129complete; he is a man or a child of action, but he is no artist, and no art-lover. Another man looks at the same plate of cherries. His sight and his smell lure him and urge him to eat. He does not eat; the cycle is not completed, and, because he does not eat, the sight of those cherries, though perhaps not the smell, is altered, purified from desire, and in some way intensified, enlarged. If he is just a man of taste, he will take what we call an “æsthetic” pleasure in those cherries. If he is an actual artist, he will paint not the cherries, but his vision of them, his purified emotion towards them. He has, so to speak, come out from the chorus of actors, of cherry-eaters, and become a spectator.

I borrow, by his kind permission, a beautiful instance of what he well calls “Psychical Distance” from the writings of a psychologist.36

“Imagine a fog at sea: for most people it is an experience of acute unpleasantness. Apart from the physical annoyance and remoter forms of discomfort, such as delays, it is apt to produce feelings of peculiar anxiety, fears of invisible dangers, strains of watching 130and listening for distant and unlocalized signals. The listless movements of the ship and her warning calls soon tell upon the nerves of the passengers; and that special, expectant tacit anxiety and nervousness, always associated with this experience, make a fog the dreaded terror of the sea (all the more terrifying because of its very silence and gentleness) for the expert seafarer no less than the ignorant landsman.

“Nevertheless, a fog at sea can be a source of intense relish and enjoyment. Abstract from the experience of the sea-fog, for the moment, its danger and practical unpleasantness; ... direct the attention to the features ‘objectively’ constituting the phenomena—the veil surrounding you with an opaqueness as of transparent milk, blurring the outlines of things and distorting their shapes into weird grotesqueness; observe the carrying power of the air, producing the impression as if you could touch some far-off siren by merely putting out your hand and letting it lose itself behind that white wall; note the curious creamy smoothness of the water, hypercritically denying as it were, any suggestion of danger; and, above all, the strange 131solitude and remoteness from the world, as it can be found only on the highest mountain tops; and the experience may acquire, in its uncanny mingling of repose and terror, a flavour of such concentrated poignancy and delight as to contrast sharply with the blind and distempered anxiety of its other aspects. This contrast, often emerging with startling suddenness, is like the momentary switching on of some new current, or the passing ray of a brighter light, illuminating the outlook upon perhaps the most ordinary and familiar objects—an impression which we experience sometimes in instants of direst extremity, when our practical interest snaps like a wire from sheer over-tension, and we watch the consummation of some impending catastrophe with the marvelling unconcern of a mere spectator.”

It has often been noted that two, and two only, of our senses are the channels of art and give us artistic material. These two senses are sight and hearing. Touch and its special modifications, taste and smell, do not go to the making of art. Decadent French novelists, such as Huysmann, make their heroes 132revel in perfume-symphonies, but we feel that the sentiment described is morbid and unreal, and we feel rightly. Some people speak of a cook as an “artist,” and a pudding as a “perfect poem,” but a healthy instinct rebels. Art, whether sculpture, painting, drama, music, is of sight or hearing. The reason is simple. Sight and hearing are the distant senses; sight is, as some one has well said, “touch at a distance.” Sight and hearing are of things already detached and somewhat remote; they are the fitting channels for art which is cut loose from immediate action and reaction. Taste and touch are too intimate, too immediately vital. In Russian, as Tolstoi has pointed out (and indeed in other languages the same is observable), the word for beauty (krasota) means, to begin with, only that which pleases the sight. Even hearing is excluded. And though latterly people have begun to speak of an “ugly deed” or of “beautiful music,” it is not good Russian. The simple Russian does not make Plato’s divine muddle between the good and the beautiful. If a man gives his coat to another, the Russian peasant, knowing no foreign language, will not say the man has acted “beautifully.”

133To see a thing, to feel a thing, as a work of art, we must, then, become for the time unpractical, must be loosed from the fear and the flurry of actual living, must become spectators. Why is this? Why can we not live and look at once? The fact that we cannot is clear. If we watch a friend drowning we do not note the exquisite curve made by his body as he falls into the water, nor the play of the sunlight on the ripples as he disappears below the surface; we should be inhuman, æsthetic fiends if we did. And again, why? It would do our friend no harm that we should enjoy the curves and the sunlight, provided we also threw him a rope. But the simple fact is that we cannot look at the curves and the sunlight because our whole being is centred on acting, on saving him; we cannot even, at the moment, fully feel our own terror and impending loss. So again if we want to see and to feel the splendour and vigour of a lion, or even to watch the cumbrous grace of a bear, we prefer that a cage should intervene. The cage cuts off the need for motor actions; it interposes the needful physical and moral distance, and we are free for contemplation. Released from our own terrors, we see more and 134better, and we feel differently. A man intent on action is like a horse in blinkers, he goes straight forward, seeing only the road ahead.

Our brain is, indeed, it would seem, in part, an elaborate arrangement for providing these blinkers. If we saw and realized the whole of everything, we should want to do too many things. The brain allows us not only to remember, but, which is quite as important, to forget and neglect; it is an organ of oblivion. By neglecting most of the things we see and hear, we can focus just on those which are important for action; we can cease to be potential artists and become efficient practical human beings; but it is only by limiting our view, by a great renunciation as to the things we see and feel. The artist does just the reverse. He renounces doing in order to practise seeing. He is by nature what Professor Bergson calls “distrait,” aloof, absent-minded, intent only, or mainly, on contemplation. That is why the ordinary man often thinks the artist a fool, or, if he does not go so far as that, is made vaguely uncomfortable by him, never really understands him. The artist’s focus, all his system 135of values, is different, his world is a world of images which are his realities.

The distinction between art and ritual, which has so long haunted and puzzled us, now comes out quite clearly, and also in part the relation of each to actual life. Ritual, we saw, was a re-presentation or a pre-presentation, a re-doing or pre-doing, a copy or imitation of life, but,—and this is the important point,—always with a practical end. Art is also a representation of life and the emotions of life, but cut loose from immediate action. Action may be and often is represented, but it is not that it may lead on to a practical further end. The end of art is in itself. Its value is not mediate but immediate. Thus ritual makes, as it were, a bridge between real life and art, a bridge over which in primitive times it would seem man must pass. In his actual life he hunts and fishes and ploughs and sows, being utterly intent on the practical end of gaining his food; in the dromenon of the Spring Festival, though his acts are unpractical, being mere singing and dancing and mimicry, his intent is practical, to induce the return of his food-supply.136 In the drama the representation may remain for a time the same, but the intent is altered: man has come out from action, he is separate from the dancers, and has become a spectator. The drama is an end in itself.

We know from tradition that in Athens ritual became art, a dromenon became the drama, and we have seen that the shift is symbolized and expressed by the addition of the theatre, or spectator-place, to the orchestra, or dancing-place. We have also tried to analyse the meaning of the shift. It remains to ask what was its cause. Ritual does not always develop into art, though in all probability dramatic art has always to go through the stage of ritual. The leap from real life to the emotional contemplation of life cut loose from action would otherwise be too wide. Nature abhors a leap, she prefers to crawl over the ritual bridge. There seem at Athens to have been two main causes why the dromenon passed swiftly, inevitably, into the drama. They are, first, the decay of religious faith; second, the influx from abroad of a new culture and new dramatic material.

It may seem surprising to some that the 137decay of religious faith should be an impulse to the birth of art. We are accustomed to talk rather vaguely of art “as the handmaid of religion”; we think of art as “inspired by” religion. But the decay of religious faith of which we now speak is not the decay of faith in a god, or even the decay of some high spiritual emotion; it is the decay of a belief in the efficacy of certain magical rites, and especially of the Spring Rite. So long as people believed that by excited dancing, by bringing in an image or leading in a bull you could induce the coming of Spring, so long would the dromena of the Dithyramb be enacted with intense enthusiasm, and with this enthusiasm would come an actual accession and invigoration of vital force. But, once the faintest doubt crept in, once men began to be guided by experience rather than custom, the enthusiasm would die down, and the collective invigoration no longer be felt. Then some day there will be a bad summer, things will go all wrong, and the chorus will sadly ask: “Why should I dance my dance?” They will drift away or become mere spectators of a rite established by custom. The rite itself will die down, or it will live on 138only as the May Day rites of to-day, a children’s play, or at best a thing done vaguely “for luck.”

The spirit of the rite, the belief in its efficacy, dies, but the rite itself, the actual mould, persists, and it is this ancient ritual mould, foreign to our own usage, that strikes us to-day, when a Greek play is revived, as odd and perhaps chill. A chorus, a band of dancers there must be, because the drama arose out of a ritual dance. An agon, or contest, or wrangling, there will probably be, because Summer contends with Winter, Life with Death, the New Year with the Old. A tragedy must be tragic, must have its pathos, because the Winter, the Old Year, must die. There must needs be a swift transition, a clash and change from sorrow to joy, what the Greeks called a peripeteia, a quick-turn-round, because, though you carry out Winter, you bring in Summer. At the end we shall have an Appearance, an Epiphany of a god, because the whole gist of the ancient ritual was to summon the spirit of life. All these ritual forms haunt and shadow the play, whatever its plot, like ancient traditional ghosts; they underlie and 139sway the movement and the speeches like some compelling rhythm.

Now this ritual mould, this underlying rhythm, is a fine thing in itself; and, moreover, it was once shaped and cast by a living spirit: the intense immediate desire for food and life, and for the return of the seasons which bring that food and life. But we have seen that, once the faith in man’s power magically to bring back these seasons waned, once he began to doubt whether he could really carry out Winter and bring in Summer, his emotion towards these rites would cool. Further, we have seen that these rites repeated year by year ended, among an imaginative people, in the mental creation of some sort of dæmon or god. This dæmon, or god, was more and more held responsible on his own account for the food-supply and the order of the Horæ, or Seasons; so we get the notion that this dæmon or god himself led in the Seasons; Hermes dances at the head of the Charites, or an Eiresione is carried to Helios and the Horæ. The thought then arises that this man-like dæmon who rose from a real King of the May, must himself be approached and dealt with as a man, bargained with, 140sacrificed to. In a word, in place of dromena, things done, we get gods worshipped; in place of sacraments, holy bulls killed and eaten in common, we get sacrifices in the modern sense, holy bulls offered to yet holier gods. The relation of these figures of gods to art we shall consider when we come to sculpture.

So the dromenon, the thing done, wanes, the prayer, the praise, the sacrifice waxes. Religion moves away from drama towards theology, but the ritual mould of the dromenon is left ready for a new content.

Again, there is another point. The magical dromenon, the Carrying out of Winter, the Bringing in of Spring, is doomed to an inherent and deadly monotony. It is only when its magical efficacy is intensely believed that it can go on. The life-history of a holy bull is always the same; its magical essence is that it should be the same. Even when the life-dæmon is human his career is unchequered. He is born, initiated, or born again; he is married, grows old, dies, is buried; and the old, old story is told again next year. There are no fresh personal incidents, peculiar to one particular dæmon. If the drama rose from the Spring Song only, beautiful it might 141be, but with a beauty that was monotonous, a beauty doomed to sterility.

We seem to have come to a sort of impasse, the spirit of the dromenon is dead or dying, the spectators will not stay long to watch a doing doomed to monotony. The ancient moulds are there, the old bottles, but where is the new wine? The pool is stagnant; what angel will step down to trouble the waters?

Fortunately we are not left to conjecture what might have happened. In the case of Greece we know, though not as clearly as we wish, what did happen. We can see in part why, though the dromena of Adonis and Osiris, emotional as they were and intensely picturesque, remained mere ritual; the dromenon of Dionysos, his Dithyramb, blossomed into drama.

Let us look at the facts, and first at some structural facts in the building of the theatre.

We have seen that the orchestra, with its dancing chorus, stands for ritual, for the stage in which all were worshippers, all joined in a rite of practical intent. We further saw that the theatre, the place for the 142spectators, stood for art. In the orchestra all is life and dancing; the marble seats are the very symbol of rest, aloofness from action, contemplation. The seats for the spectators grow and grow in importance till at last they absorb, as it were, the whole spirit, and give their name theatre to the whole structure; action is swallowed up in contemplation. But contemplation of what? At first, of course, of the ritual dance, but not for long. That, we have seen, was doomed to a deadly monotony. In a Greek theatre there was not only orchestra and a spectator-place, there was also a scene or stage.

The Greek word for stage is, as we said, skenè, our scene. The scene was not a stage in our sense, i.e. a platform raised so that the players might be better viewed. It was simply a tent, or rude hut, in which the players, or rather dancers, could put on their ritual dresses. The fact that the Greek theatre had, to begin with, no permanent stage in our sense, shows very clearly how little it was regarded as a spectacle. The ritual dance was a dromenon, a thing to be done, not a thing to be looked at. The history of the Greek stage is one long story of the 143encroachment of the stage on the orchestra. At first a rude platform or table is set up, then scenery is added; the movable tent is translated into a stone house or a temple front. This stands at first outside the orchestra; then bit by bit the scene encroaches till the sacred circle of the dancing-place is cut clean across. As the drama and the stage wax, the dromenon and the orchestra wane.

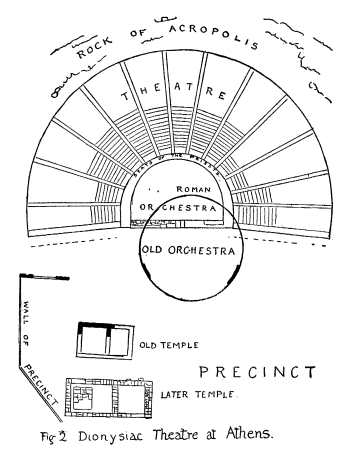

This shift in the relation of dancing-place and stage is very clearly seen in Fig. 2, a plan of the Dionysiac theatre at Athens (p. 144). The old circular orchestra shows the dominance of ritual; the new curtailed orchestra of Roman times and semicircular shape shows the dominance of the spectacle.

Greek tragedy arose, Aristotle has told us, from the leaders of the Dithyramb, the leaders of the Spring Dance. The Spring Dance, the mime of Summer and Winter, had, as we have seen, only one actor, one actor with two parts—Death and Life. With only one play to be played, and that a one-actor play, there was not much need for a stage. A scene, that is a tent, was needed, as we saw, because all the dancers had to put on their ritual gear, but scarcely a stage. From a rude platform the prologue might be spoken, and on that platform the Epiphany or Appearance of the New Year might take place; but the play played, the life-history of the life-spirit, was all too familiar; there was no need to look, the thing was to dance. You need a stage—not necessarily a raised stage, but a place apart from the dancers—when you have new material for your players, something you need to look at, to attend to. In the sixth century B.C., at Athens, came the great innovation. Instead of the old plot, the life-history of the life-spirit, with its deadly monotony, new plots were introduced, not of life-spirits but of human individual heroes. In a word, Homer came to Athens, and out of Homeric stories playwrights began to make their plots. This innovation was the death of ritual monotony and the dromenon. It is not so much the old that dies as the new that kills.

Æschylus himself is reported to have said that his tragedies were “slices from the great banquet of Homer.” The metaphor is not a very pleasing one, but it expresses a truth.146 By Homer, Æschylus meant not only our Iliad and Odyssey, but the whole body of Epic or Heroic poetry which centred round not only the Siege of Troy but the great expedition of the Seven Against Thebes, and which, moreover, contained the stories of the heroes before the siege began, and their adventures after it was ended. It was from these heroic sagas for the most part, though not wholly, that the myths or plots of not only Æschylus but also Sophocles and Euripides, and a host of other writers whose plays are lost to us, are taken. The new wine that was poured into the old bottles of the dromena at the Spring Festival was the heroic saga. We know as an historical fact, the name of the man who was mainly responsible for this inpouring—the great democratic tyrant Peisistratos. We must look for a moment at what Peisistratos found, and then pass to what he did.

He found an ancient Spring dromenon, perhaps well-nigh effete. Without destroying the old he contrived to introduce the new, to add to the old plot of Summer and Winter the life-stories of heroes, and thereby arose the drama.

147Let us look first, then, at what Peisistratos found.

The April festival of Dionysos at which the great dramas were performed was not the earliest festival of the god. Thucydides37 expressly tells us that on the 12th day of the month Anthesterion, that is in the quite early spring, at the turn of our February and March, were celebrated the more ancient Dionysia. It was a three-days’ festival.38 On the first day, called “Cask-opening,” the jars of new wine were broached. Among the Bœotians the day was called not the day of Dionysos, but the day of the Good or Wealthy Daimon. The next day was called the day of the “Cups”—there was a contest or agon of drinking. The last day was called the “Pots,” and it, too, had its “Pot-Contests.” It is the ceremonies of this day that we must notice a little in detail; for they are very surprising. “Casks,” “Cups,” and “Pots,” sound primitive enough. “Casks” and “Cups” go well with the wine-god, but the “Pots” call for explanation.

The second day of the “Cups,” joyful 148though it sounds, was by the Athenians counted unlucky, because on that day they believed “the ghosts of the dead rose up.” The sanctuaries were roped in, each householder anointed his door with pitch, that the ghost who tried to enter might catch and stick there. Further, to make assurance doubly sure, from early dawn he chewed a bit of buckthorn, a plant of strong purgative powers, so that, if a ghost should by evil chance go down his throat, it should at least be promptly expelled.

For two, perhaps three, days of constant anxiety and ceaseless precautions the ghosts fluttered about Athens. Men’s hearts were full of nameless dread, and, as we shall see, hope. At the close of the third day the ghosts, or, as the Greeks called them, Keres, were bidden to go. Some one, we do not know whom, it may be each father of a household, pronounced the words: “Out of the door, ye Keres; it is no longer Anthesteria,” and, obedient, the Keres were gone.

But before they went there was a supper for these souls. All the citizens cooked a panspermia or “Pot-of-all-Seeds,” but of this Pot-of-all-Seeds no citizen tasted. It was made 149over to the spirits of the under-world and Hermes their daimon, Hermes “Psychopompos,” Conductor, Leader of the dead.

We have seen how a forest people, dependent on fruit trees and berries for their food, will carry a maypole and imagine a tree-spirit. But a people of agriculturists will feel and do and think quite otherwise; they will look, not to the forest but to the earth for their returning life and food; they will sow seeds and wait for their sprouting, as in the gardens of Adonis. Adonis seems to have passed through the two stages of Tree-Spirit and Seed-Spirit; his effigy was sometimes a tree cut down, sometimes his planted “Gardens.” Now seeds are many, innumerable, and they are planted in the earth, and a people who bury their dead know, or rather feel, that the earth is dead man’s land. So, when they prepare a pot of seeds on their All Souls’ Day, it is not really or merely as a “supper for the souls,” though it may be that kindly notion enters. The ghosts have other work to do than to eat their supper and go. They take that supper “of all seeds,” that panspermia, with them down to the world below, 150that they may tend it and foster it and bring it back in autumn as a pot of all fruits, a pankarpia.

“Thou fool, that which thou sowest is not quickened except it die.”

The dead, then, as well as the living—this is for us the important point—had their share in the dromena of the “more ancient Dionysia.” These agricultural spring dromena were celebrated just outside the ancient city gates, in the agora, or place of assembly, on a circular dancing-place, near to a very primitive sanctuary of Dionysos which was opened only once in the year, at the Feast of Cups. Just outside the gates was celebrated yet another festival of Dionysos equally primitive, called the “Dionysia in the Fields.” It had the form though not the date of our May Day festival. Plutarch39 thus laments over the “good old times”: “In ancient days,” he says, “our fathers used to keep the feast of Dionysos in homely, jovial fashion. There was a procession, a jar of wine and a branch; then some one dragged in a goat, 151another followed bringing a wicker basket of figs, and, to crown all, the phallos.” It was just a festival of the fruits of the whole earth: wine and the basket of figs and the branch for vegetation, the goat for animal life, the phallos for man. No thought here of the dead, it is all for the living and his food.

Such sanctities even a great tyrant might not tamper with. But if you may not upset the old you may without irreverence add the new. Peisistratos probably cared little for, and believed less in, magical ceremonies for the renewal of fruits, incantations of the dead. We can scarcely picture him chewing buckthorn on the day of the “Cups,” or anointing his front door with pitch to keep out the ghosts. Very wisely he left the Anthesteria and the kindred festival “in the fields” where and as they were. But for his own purposes he wanted to do honour to Dionysos, and also above all things to enlarge and improve the rites done in the god’s honour, so, leaving the old sanctuary to its fate, he built a new temple on the south side of the Acropolis where the present theatre 152now stands, and consecrated to the god a new and more splendid precinct.

He did not build the present theatre, we must always remember that. The rows of stone seats, the chief priest’s splendid marble chair, were not erected till two centuries later. What Peisistratos did was to build a small stone temple (see Fig. 2), and a great round orchestra of stone close beside it. Small fragments of the circular foundation can still be seen. The spectators sat on the hill-side or on wooden seats; there was as yet no permanent theātron or spectator-place, still less a stone stage; the dromena were done on the dancing-place. But for spectator-place they had the south slope of the Acropolis. What kind of wooden stage they had unhappily we cannot tell. It may be that only a portion of the orchestra was marked off.

Why did Peisistratos, if he cared little for magic and ancestral ghosts, take such trouble to foster and amplify the worship of this maypole-spirit, Dionysos? Why did he add to the Anthesteria, the festival of the family ghosts and the peasant festival “in the fields,”153 a new and splendid festival, a little later in the spring, the Great Dionysia, or Dionysia of the City? One reason among others was this—Peisistratos was a “tyrant.”

Now a Greek “tyrant” was not in our sense “tyrannical.” He took his own way, it is true, but that way was to help and serve the common people. The tyrant was usually raised to his position by the people, and he stood for democracy, for trade and industry, as against an idle aristocracy. It was but a rudimentary democracy, a democratic tyranny, the power vested in one man, but it stood for the rights of the many as against the few. Moreover, Dionysos was always of the people, of the “working classes,” just as the King and Queen of the May are now. The upper classes worshipped then, as now, not the Spirit of Spring but their own ancestors. But—and this was what Peisistratos with great insight saw—Dionysos must be transplanted from the fields to the city. The country is always conservative, the natural stronghold of a landed aristocracy, with fixed traditions; the city with its closer contacts and consequent swifter changes, and, above all, with its acquired, not inherited, wealth, tends towards 154democracy. Peisistratos left the Dionysia “in the fields,” but he added the Great Dionysia “in the city.”

Peisistratos was not the only tyrant who concerned himself with the dromena of Dionysos. Herodotos40 tells the story of another tyrant, a story which is like a window opening suddenly on a dark room. At Sicyon, a town near Corinth, there was in the agora a heroon, a hero-tomb, of an Argive hero, Adrastos.

“The Sicyonians,” says Herodotos, “paid other honours to Adrastos, and, moreover, they celebrated his death and disasters with tragic choruses, not honouring Dionysos but Adrastos.” We think of “tragic” choruses as belonging exclusively to the theatre and Dionysos; so did Herodotus, but clearly here they belonged to a local hero. His adventures and his death were commemorated by choral dances and songs. Now when Cleisthenes became tyrant of Sicyon he felt that the cult of the local hero was a danger. What did he do? Very adroitly he brought in from Thebes another hero as rival to Adrastos. He then split up the worship of Adrastos; part of 155his worship, and especially his sacrifices, he gave to the new Theban hero, but the tragic choruses he gave to the common people’s god, to Dionysos. Adrastos, the objectionable hero, was left to dwindle and die. No local hero can live on without his cult.

The act of Cleisthenes seems to us a very drastic proceeding. But perhaps it was not really so revolutionary as it seems. The local hero was not so very unlike a local dæmon, a Spring or Winter spirit. We have seen in the Anthesteria how the paternal ghosts are expected to look after the seeds in spring. The more important the ghost the more incumbent is this duty upon him. Noblesse oblige. On the river Olynthiakos41 in Northern Greece stood the tomb of the hero Olynthos, who gave the river its name. In the spring months of Anthesterion and Elaphebolion the river rises and an immense shoal of fish pass from the lake of Bolbe to the river of Olynthiakos, and the inhabitants round about can lay in a store of salt fish for all their needs. “And it is a wonderful fact that they never pass by the monument of Olynthus. They say that 156formerly the people used to perform the accustomed rites to the dead in the month Elaphebolion, but now they do them in Anthesterion, and that on this account the fish come up in those months only in which they are wont to do honour to the dead.” The river is the chief source of the food-supply, so to send fish, not seeds and flowers, is the dead hero’s business.

Peisistratos was not so daring as Cleisthenes. We do not hear that he disturbed or diminished any local cult. He did not attempt to move the Anthesteria with its ghost cult; he only added a new festival, and trusted to its recent splendour gradually to efface the old. And at this new festival he celebrated the deeds of other heroes, not local but of greater splendour and of wider fame. If he did not bring Homer to Athens, he at least gave Homer official recognition. Now to bring Homer to Athens was like opening the eyes of the blind.

Cicero, in speaking of the influence of Peisistratos on literature, says: “He is said to have arranged in their present order the works of Homer, which were previously in 157confusion.” He arranged them not for what we should call “publication,” but for public recitation, and another tradition adds that he or his son fixed the order of their recitation at the great festival of “All Athens,” the Panathenaia. Homer, of course, was known before in Athens in a scrappy way; now he was publicly, officially promulgated. It is probable, though not certain, that the “Homer” which Peisistratos prescribed for recitation at the Panathenaia was just our Iliad and Odyssey, and that the rest of the heroic cycle, all the remaining “slices” from the heroic banquet, remained as material for dithyrambs and dramas. The “tyranny” of Peisistratos and his son lasted from 560 to 501 B.C.; tradition said that the first dramatic contest was held in the new theatre built by Peisistratos in 535 B.C., when Thespis won the prize. Æschylus was born in 525 B.C.; his first play, with a plot from the heroic saga, the Seven Against Thebes, was produced in 467 B.C. It all came very swiftly, the shift from the dithyramb as Spring Song to the heroic drama was accomplished in something much under a century. Its effect on the whole of Greek life and religion—nay, on the whole 158of subsequent literature and thought—was incalculable. Let us try to see why.

Homer was the outcome, the expression, of an “heroic” age. When we use the word “heroic” we think vaguely of something brave, brilliant, splendid, something exciting and invigorating. A hero is to us a man of clear, vivid personality, valiant, generous, perhaps hot-tempered, a good friend and a good hater. The word “hero” calls up such figures as Achilles, Patroklos, Hector, figures of passion and adventure. Now such figures, with their special virtues, and perhaps their proper vices, are not confined to Homer. They occur in any and every heroic age. We are beginning now to see that heroic poetry, heroic characters, do not arise from any peculiarity of race or even of geographical surroundings, but, given certain social conditions, they may, and do, appear anywhere and at any time. The world has seen several heroic ages, though it is, perhaps, doubtful if it will ever see another. What, then, are the conditions that produce an heroic age? and why was this influx of heroic poetry, coming just when it did, of such immense influence 159on, and importance to, the development of Greek dramatic art? Why had it power to change the old, stiff, ritual dithyramb into the new and living drama? Why, above all things, did the democratic tyrant Peisistratos so eagerly welcome it to Athens?

In the old ritual dance the individual was nothing, the choral band, the group, everything, and in this it did but reflect primitive tribal life. Now in the heroic saga the individual is everything, the mass of the people, the tribe, or the group, are but a shadowy background which throws up the brilliant, clear-cut personality into a more vivid light. The epic poet is all taken up with what he called klea andron, “glorious deeds of men,” of individual heroes; and what these heroes themselves ardently long and pray for is just this glory, this personal distinction, this deathless fame for their great deeds. When the armies meet it is the leaders who fight in single combat. These glorious heroes are for the most part kings, but not kings in the old sense, not hereditary kings bound to the soil and responsible for its fertility. Rather they are leaders in war and adventure; the homage 160paid them is a personal devotion for personal character; the leader must win his followers by bravery, he must keep them by personal generosity. Moreover, heroic wars are oftenest not tribal feuds consequent on tribal raids, more often they arise from personal grievances, personal jealousies; the siege of Troy is undertaken not because the Trojans have raided the cattle of the Achæans, but because a single Trojan, Paris, has carried off Helen, a single Achæan’s wife.

Another noticeable point is that in heroic poems scarcely any one is safely and quietly at home. The heroes are fighting in far-off lands or voyaging by sea; hence we hear little of tribal and even of family ties. The real centre is not the hearth, but the leader’s tent or ship. Local ties that bind to particular spots of earth are cut, local differences fall into abeyance, a sort of cosmopolitanism, a forecast of pan-Hellenism, begins to arise. And a curious point—all this is reflected in the gods. We hear scarcely anything of local cults, nothing at all of local magical maypoles and Carryings-out of Winter and Bringings-in of Summer, nothing whatever of “Suppers” for the souls, or even of worship 161paid to particular local heroes. A man’s ghost when he dies does not abide in its grave ready to rise at springtime and help the seeds to sprout; it goes to a remote and shadowy region, a common, pan-Hellenic Hades. And so with the gods themselves; they are cut clean from earth and from the local bits of earth out of which they grew—the sacred trees and holy stones and rivers and still holier beasts. There is not a holy Bull to be found in all Olympus, only figures of men, bright and vivid and intensely personal, like so many glorified, transfigured Homeric heroes.

In a word, the heroic spirit, as seen in heroic poetry, is the outcome of a society cut loose from its roots, of a time of migrations, of the shifting of populations.42 But more is needed, and just this something more the age that gave birth to Homer had. We know now that before the northern people whom we call Greeks, and who called themselves Hellenes, came down into Greece, there had grown up in the basin of the Ægean a civilization splendid, wealthy, rich in art and already ancient, the civilization that has come to light at Troy, Mycenæ, Tiryns, and most of 162all in Crete. The adventurers from North and South came upon a land rich in spoils, where a chieftain with a band of hardy followers might sack a city and dower himself and his men with sudden wealth. Such conditions, such a contact of new and old, of settled splendour beset by unbridled adventure, go to the making of a heroic age, its virtues and its vices, its obvious beauty and its hidden ugliness. In settled, social conditions, as has been well remarked, “most of the heroes would sooner or later have found themselves in prison.”

A heroic age, happily for society, cannot last long; it has about it while it does last a sheen of passing and pathetic splendour, such as that which lights up the figure of Achilles, but it is bound to fade and pass. A heroic society is almost a contradiction in terms. Heroism is for individuals. If a society is to go on at all it must strike its roots deep in some soil, native or alien. The bands of adventurers must disband and go home, or settle anew on the land they have conquered. They must beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning-hooks. Their gallant, glorious leader must become a sober, home-keeping, law-163giving and law-abiding king; his followers must abate their individuality and make it subserve a common social purpose.

Athens, in her sheltered peninsula, lay somewhat outside the tide of migrations and heroic exploits. Her population and that of all Attica remained comparatively unchanged; her kings are kings of the stationary, law-abiding, state-reforming type; Cecrops, Erechtheus, Theseus, are not splendid, flashing, all-conquering figures like Achilles and Agamemnon. Athens might, it would seem, but for the coming of Homer, have lain stagnant in a backwater of conservatism, content to go on chanting her traditional Spring Songs year by year. It is a wonderful thing that this city of Athens, beloved of the gods, should have been saved from the storm and stress, sheltered from what might have broken, even shattered her, spared the actual horrors of a heroic age, yet given heroic poetry, given the clear wine-cup poured when the ferment was over. She drank of it deep and was glad and rose up like a giant refreshed.

We have seen that to make up a heroic age there must be two factors, the new and the 164old; the young, vigorous, warlike people must seize on, appropriate, in part assimilate, an old and wealthy civilization. It almost seems as if we might go a step farther, and say that for every great movement in art or literature we must have the same conditions, a contact of new and old, of a new spirit seizing or appropriated by an old established order. Anyhow for Athens the historical fact stands certain. The amazing development of the fifth-century drama is just this, the old vessel of the ritual Dithyramb filled to the full with the new wine of the heroic saga; and it would seem that it was by the hand of Peisistratos, the great democratic tyrant, that the new wine was outpoured.

Such were roughly the outside conditions under which the drama of art grew out of the dromena of ritual. The racial secret of the individual genius of Æschylus and the forgotten men who preceded him we cannot hope to touch. We can only try to see the conditions in which they worked and mark the splendid new material that lay to their hands. Above all things we can see that this material, these Homeric saga, were just fitted 165to give the needed impulse to art. The Homeric saga had for an Athenian poet just that remoteness from immediate action which, as we have seen, is the essence of art as contrasted with ritual.

Tradition says that the Athenians fined the dramatic poet Phrynichus for choosing as the plot of one of his tragedies the Taking of Miletus. Probably the fine was inflicted for political party reasons, and had nothing whatever to do with the question of whether the subject was “artistic” or not. But the story may stand, and indeed was later understood to be, a sort of allegory as to the attitude of art towards life. To understand and still more to contemplate life you must come out from the choral dance of life and stand apart. In the case of one’s own sorrows, be they national or personal, this is all but impossible. We can ritualize our sorrows, but not turn them into tragedies. We cannot stand back far enough to see the picture; we want to be doing, or at least lamenting. In the case of the sorrows of others this standing back is all too easy. We not only bear their pain with easy stoicism, but we picture it dispassionately at a safe distance; we feel166 about rather than with it. The trouble is that we do not feel enough. Such was the attitude of the Athenian towards the doings and sufferings of Homeric heroes. They stood towards them as spectators. These heroes had not the intimate sanctity of home-grown things, but they had sufficient traditional sanctity to make them acceptable as the material of drama.

Adequately sacred though they were, they were yet free and flexible. It is impiety to alter the myth of your local hero, it is impossible to recast the myth of your local dæmon—that is fixed forever—his conflict, his agon, his death, his pathos, his Resurrection and its heralding, his Epiphany. But the stories of Agamemnon and Achilles, though at home these heroes were local daimones, have already been variously told in their wanderings from place to place, and you can mould them more or less to your will. Moreover, these figures are already personal and individual, not representative puppets, mere functionaries like the May Queen and Winter; they have life-histories of their own, never quite to be repeated. It is in this blend of the individual and the general, the personal and 167the universal, that one element at least of all really great art will be found to lie; and just here at Athens we get a glimpse of the moment of fusion; we see a definite historical reason why and how the universal in dromena came to include the particular in drama. We see, moreover, how in place of the old monotonous plots, intimately connected with actual practical needs, we get material cut off from immediate reactions, seen as it were at the right distance, remote yet not too remote. We see, in a word, how a ritual enacted year by year became a work of art that was a “possession for ever.”

Possibly in the mind of the reader there may have been for some time a growing discomfort, an inarticulate protest. All this about dromena and drama and dithyrambs, bears and bulls, May Queens and Tree-Spirits, even about Homeric heroes, is all very well, curious and perhaps even in a way interesting, but it is not at all what he expected, still less what he wants. When he bought a book with the odd incongruous title, Ancient Art and Ritual, he was prepared to put up with some remarks on the artistic side of ritual, 168but he did expect to be told something about what the ordinary man calls art, that is, statues and pictures. Greek drama is no doubt a form of ancient art, but acting is not to the reader’s mind the chief of arts. Nay, more, he has heard doubts raised lately—and he shares them—as to whether acting and dancing, about which so much has been said, are properly speaking arts at all. Now about painting and sculpture there is no doubt. Let us come to business.

To a business so beautiful and pleasant as Greek sculpture we shall gladly come, but a word must first be said to explain the reason of our long delay. The main contention of the present book is that ritual and art have, in emotion towards life, a common root, and further, that primitive art develops normally, at least in the case of the drama, straight out of ritual. The nature of that primitive ritual from which the drama arose is not very familiar to English readers. It has been necessary to stress its characteristics. Almost everywhere, all over the world, it is found that primitive ritual consists, not in prayer and praise and sacrifice, but in mimetic dancing. But it is in Greece, and perhaps Greece only, 169in the religion of Dionysos, that we can actually trace, if dimly, the transition steps that led from dance to drama, from ritual to art. It was, therefore, of the first importance to realize the nature of the dithyramb from which the drama rose, and so far as might be to mark the cause and circumstances of the transition.

Leaving the drama, we come in the next chapter to Sculpture; and here, too, we shall see how closely art was shadowed by that ritual out of which she sprang.

35 See Bibliography at end for Professor Murray’s examination.

36 Mr. Edward Bullough, The British Journal of Psychology (1912), p. 88.

37 II, 15.

38 See my Themis, p. 289, and Prolegomena, p. 35.

39 De Cupid. div. 8.

40 V, 66.

41 Athen., VIII, ii, 334 f. See my Prolegomena, p. 54.

42 Thanks to Mr. H.M. Chadwick’s Heroic Age (1912).

Index | Previous | Next: Greek Sculpture: The Panthenaic Frieze And The Apollo Belvedere