All Around the Moon, by Jules Verne

CHAPTER VI.

INSTRUCTIVE CONVERSATION.

On the fourth of December, the Projectile chronometers marked five o'clock in the morning, just as the travellers woke up from a pleasant slumber. They had now been 54 hours on their journey. As to lapse of time, they had passed not much more than half of the number of hours during which their trip was to last; but, as to lapse of space, they had already accomplished very nearly the seven-tenths of their passage. This difference between time and distance was due to the regular retardation of their velocity.

They looked at the earth through the floor-light, but it was little more than visible—a black spot drowned in the solar rays. No longer any sign of a crescent, no longer any sign of ashy light. Next day, towards midnight, the Earth was to be new, at the precise moment when the Moon was to be full. Overhead, they could see the Queen of Night coming nearer and nearer to the line followed by the Projectile, and evidently approaching the point where both should meet at the appointed moment. All around, the black vault of heaven was dotted with luminous points which seemed to move somewhat, though, of course, in their extreme distance their relative size underwent no change. The Sun and the stars looked exactly as they had appeared when observed from the Earth. The Moon indeed had become considerably enlarged in size, but the travellers' telescopes were still too weak to enable them to make any important observation regarding the nature of her surface, or that might determine her topographical or geological features.

Naturally, therefore, the time slipped away in endless conversation. The Moon, of course, was the chief topic. Each one contributed his share of peculiar information, or peculiar ignorance, as the case might be. Barbican and M'Nicholl always treated the subject gravely, as became learned scientists, but Ardan preferred to look on things with the eye of fancy. The Projectile, its situation, its direction, the incidents possible to occur, the precautions necessary to take in order to break the fall on the Moon's surface—these and many other subjects furnished endless food for constant debate and inexhaustible conjectures.

For instance, at breakfast that morning, a question of Ardan's regarding the Projectile drew from Barbican an answer curious enough to be reported.

"Suppose, on the night that we were shot up from Stony Hill," said Ardan, "suppose the Projectile had encountered some obstacle powerful enough to stop it—what would be the consequence of the sudden halt?"

"But," replied Barbican, "I don't understand what obstacle it could have met powerful enough to stop it."

"Suppose some obstacle, for the sake of argument," said Ardan.

"Suppose what can't be supposed," replied the matter-of-fact Barbican, "what cannot possibly be supposed, unless indeed the original impulse proved too weak. In that case, the velocity would have decreased by degrees, but the Projectile itself would not have suddenly stopped."

"Suppose it had struck against some body in space."

"What body, for instance?"

"Well, that enormous bolide which we met."

"Oh!" hastily observed the Captain, "the Projectile would have been dashed into a thousand pieces and we along with it."

"Better than that," observed Barbican; "we should have been burned alive."

"Burned alive!" laughed Ardan. "What a pity we missed so interesting an experiment! How I should have liked to find out how it felt!"

"You would not have much time to record your observations, friend Michael, I assure you," observed Barbican. "The case is plain enough. Heat and motion are convertible terms. What do we mean by heating water? Simply giving increased, in fact, violent motion to its molecules."

"Well!" exclaimed the Frenchman, "that's an ingenious theory any how!"

"Not only ingenious but correct, my dear friend, for it completely explains all the phenomena of caloric. Heat is nothing but molecular movement, the violent oscillation of the particles of a body. When you apply the brakes to the train, the train stops. But what has become of its motion? It turns into heat and makes the brakes hot. Why do people grease the axles? To hinder them from getting too hot, which they assuredly would become if friction was allowed to obstruct the motion. You understand, don't you?"

"Don't I though?" replied Ardan, apparently in earnest. "Let me show you how thoroughly. When I have been running hard and long, I feel myself perspiring like a bull and hot as a furnace. Why am I then forced to stop? Simply because my motion has been transformed into heat! Of course, I understand all about it!"

Barbican smiled a moment at this comical illustration of his theory and then went on:

"Accordingly, in case of a collision it would have been all over instantly with our Projectile. You have seen what becomes of the bullet that strikes the iron target. It is flattened out of all shape; sometimes it is even melted into a thin film. Its motion has been turned into heat. Therefore, I maintain that if our Projectile had struck that bolide, its velocity, suddenly checked, would have given rise to a heat capable of completely volatilizing it in less than a second."

"Not a doubt of it!" said the Captain. "President," he added after a moment, "haven't they calculated what would be the result, if the Earth were suddenly brought to a stand-still in her journey, through her orbit?"

"It has been calculated," answered Barbican, "that in such a case so much heat would be developed as would instantly reduce her to vapor."

"Hm!" exclaimed Ardan; "a remarkably simple way for putting an end to the world!"

"And supposing the Earth to fall into the Sun?" asked the Captain.

"Such a fall," answered Barbican, "according to the calculations of Tyndall and Thomson, would develop an amount of heat equal to that produced by sixteen hundred globes of burning coal, each globe equal in size to the earth itself. Furthermore such a fall would supply the Sun with at least as much heat as he expends in a hundred years!"

"A hundred years! Good! Nothing like accuracy!" cried Ardan. "Such infallible calculators as Messrs. Tyndall and Thomson I can easily excuse for any airs they may give themselves. They must be of an order much higher than that of ordinary mortals like us!"

"I would not answer myself for the accuracy of such intricate problems," quietly observed Barbican; "but there is no doubt whatever regarding one fact: motion suddenly interrupted always develops heat. And this has given rise to another theory regarding the maintenance of the Sun's temperature at a constant point. An incessant rain of bolides falling on his surface compensates sufficiently for the heat that he is continually giving forth. It has been calculated—"

"Good Lord deliver us!" cried Ardan, putting his hands to his ears: "here comes Tyndall and Thomson again!"

—"It has been calculated," continued Barbican, not heeding the interruption, "that the shock of every bolide drawn to the Sun's surface by gravity, must produce there an amount of heat equal to that of the combustion of four thousand blocks of coal, each the same size as the falling bolide."

"I'll wager another cent that our bold savants calculated the heat of the Sun himself," cried Ardan, with an incredulous laugh.

"That is precisely what they have done," answered Barbican referring to his memorandum book; "the heat emitted by the Sun," he continued, "is exactly that which would be produced by the combustion of a layer of coal enveloping the Sun's surface, like an atmosphere, 17 miles in thickness."

"Well done! and such heat would be capable of—?"

"Of melting in an hour a stratum of ice 2400 feet thick, or, according to another calculation, of raising a globe of ice-cold water, 3 times the size of our Earth, to the boiling point in an hour."

"Why not calculate the exact fraction of a second it would take to cook a couple of eggs?" laughed Ardan. "I should as soon believe in one calculation as in the other.—But—by the by—why does not such extreme heat cook us all up like so many beefsteaks?"

"For two very good and sufficient reasons," answered Barbican. "In the first place, the terrestrial atmosphere absorbs the 4/10 of the solar heat. In the second, the quantity of solar heat intercepted by the Earth is only about the two billionth part of all that is radiated."

"How fortunate to have such a handy thing as an atmosphere around us," cried the Frenchman; "it not only enables us to breathe, but it actually keeps us from sizzling up like griskins."

"Yes," said the Captain, "but unfortunately we can't say so much for the Moon."

"Oh pshaw!" cried Ardan, always full of confidence. "It's all right there too! The Moon is either inhabited or she is not. If she is, the inhabitants must breathe. If she is not, there must be oxygen enough left for we, us and co., even if we should have to go after it to the bottom of the ravines, where, by its gravity, it must have accumulated! So much the better! we shall not have to climb those thundering mountains!"

So saying, he jumped up and began to gaze with considerable interest on the lunar disc, which just then was glittering with dazzling brightness.

"By Jove!" he exclaimed at length; "it must be pretty hot up there!"

"I should think so," observed the Captain; "especially when you remember that the day up there lasts 360 hours!"

"Yes," observed Barbican, "but remember on the other hand that the nights are just as long, and, as the heat escapes by radiation, the mean temperature cannot be much greater than that of interplanetary space."

"A high old place for living in!" cried Ardan. "No matter! I wish we were there now! Wouldn't it be jolly, dear boys, to have old Mother Earth for our Moon, to see her always on our sky, never rising, never setting, never undergoing any change except from New Earth to Last Quarter! Would not it be fun to trace the shape of our great Oceans and Continents, and to say: 'there is the Mediterranean! there is China! there is the gulf of Mexico! there is the white line of the Rocky Mountains where old Marston is watching for us with his big telescope!' Then we should see every line, and brightness, and shadow fade away by degrees, as she came nearer and nearer to the Sun, until at last she sat completely lost in his dazzling rays! But—by the way—Barbican, are there any eclipses in the Moon?"

"O yes; solar eclipses" replied Barbican, "must always occur whenever the centres of the three heavenly bodies are in the same line, the Earth occupying the middle place. However, such eclipses must always be annular, as the Earth, projected like a screen on the solar disc, allows more than half of the Sun to be still visible."

"How is that?" asked M'Nicholl, "no total eclipses in the Moon? Surely the cone of the Earth's shadow must extend far enough to envelop her surface?"

"It does reach her, in one sense," replied Barbican, "but it does not in another. Remember the great refraction of the solar rays that must be produced by the Earth's atmosphere. It is easy to show that this refraction prevents the Sun from ever being totally invisible. See here!" he continued, pulling out his tablets, "Let a represent the horizontal parallax, and b the half of the Sun's apparent diameter—"

"Ouch!" cried the Frenchman, making a wry face, "here comes Mr. x square riding to the mischief on a pair of double zeros again! Talk English, or Yankee, or Dutch, or Greek, and I'm your man! Even a little Arabic I can digest! But hang me, if I can endure your Algebra!"

"Well then, talking Yankee," replied Barbican with a smile, "the mean distance of the Moon from the Earth being sixty terrestrial radii, the length of the conic shadow, in consequence of atmospheric refraction, is reduced to less than forty-two radii. Consequently, at the moment of an eclipse, the Moon is far beyond the reach of the real shadow, so that she can see not only the border rays of the Sun, but even those proceeding from his very centre."

"Oh then," cried Ardan with a loud laugh, "we have an eclipse of the Sun at the moment when the Sun is quite visible! Isn't that very like a bull, Mr. Philosopher Barbican?"

"Yet it is perfectly true notwithstanding," answered Barbican. "At such a moment the Sun is not eclipsed, because we can see him: and then again he is eclipsed because we see him only by means of a few of his rays, and even these have lost nearly all their brightness in their passage through the terrestrial atmosphere!"

"Barbican is right, friend Michael," observed the Captain slowly: "the same phenomenon occurs on earth every morning at sunrise, when refraction shows us

'the Sun new ris'n

Looking through the horizontal misty air,

Shorn of his beams.'"

"He must be right," said Ardan, who, to do him justice, though quick at seeing a reason, was quicker to acknowledge its justice: "yes, he must be right, because I begin to understand at last very clearly what he really meant. However, we can judge for ourselves when we get there.—But, apropos of nothing, tell me, Barbican, what do you think of the Moon being an ancient comet, which had come so far within the sphere of the Earth's attraction as to be kept there and turned into a satellite?"

"Well, that is an original idea!" said Barbican with a smile.

"My ideas generally are of that category," observed Ardan with an affectation of dry pomposity.

"Not this time, however, friend Michael," observed M'Nicholl.

"Oh! I'm a plagiarist, am I?" asked the Frenchman, pretending to be irritated.

"Well, something very like it," observed M'Nicholl quietly. "Apollonius Rhodius, as I read one evening in the Philadelphia Library, speaks of the Arcadians of Greece having a tradition that their ancestors were so ancient that they inhabited the Earth long before the Moon had ever become our satellite. They therefore called them Προσεληνοι or Ante-lunarians. Now starting with some such wild notion as this, certain scientists have looked on the Moon as an ancient comet brought close enough to the Earth to be retained in its orbit by terrestrial attraction."

"Why may not there be something plausible in such a hypothesis?" asked Ardan with some curiosity.

"There is nothing whatever in it," replied Barbican decidedly: "a simple proof is the fact that the Moon does not retain the slightest trace of the vaporous envelope by which comets are always surrounded."

"Lost her tail you mean," said Ardan. "Pooh! Easy to account for that! It might have got cut off by coming too close to the Sun!"

"It might, friend Michael, but an amputation by such means is not very likely."

"No? Why not?"

"Because—because—By Jove, I can't say, because I don't know," cried Barbican with a quiet smile on his countenance.

"Oh what a lot of volumes," cried Ardan, "could be made out of what we don't know!"

"At present, for instance," observed M'Nicholl, "I don't know what o'clock it is."

"Three o'clock!" said Barbican, glancing at his chronometer.

"No!" cried Ardan in surprise. "Bless us! How rapidly the time passes when we are engaged in scientific conversation! Ouf! I'm getting decidedly too learned! I feel as if I had swallowed a library!"

"I feel," observed M'Nicholl, "as if I had been listening to a lecture on Astronomy in the Star course."

"Better stir around a little more," said the Frenchman; "fatigue of body is the best antidote to such severe mental labor as ours. I'll run up the ladder a bit." So saying, he paid another visit to the upper portion of the Projectile and remained there awhile whistling Malbrouk, whilst his companions amused themselves in looking through the floor window.

Ardan was coming down the ladder, when his whistling was cut short by a sudden exclamation of surprise.

"What's the matter?" asked Barbican quickly, as he looked up and saw the Frenchman pointing to something outside the Projectile.

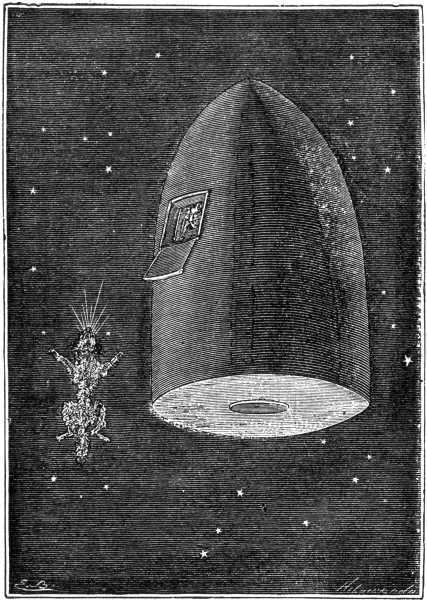

Approaching the window, Barbican saw with much surprise a sort of flattened bag floating in space and only a few yards off. It seemed perfectly motionless, and, consequently, the travellers knew that it must be animated by the same ascensional movement as themselves.

"What on earth can such a consarn be, Barbican?" asked Ardan, who every now and then liked to ventilate his stock of American slang. "Is it one of those particles of meteoric matter you were speaking of just now, caught within the sphere of our Projectile's attraction and accompanying us to the Moon?"

"What I am surprised at," observed the Captain, "is that though the specific gravity of that body is far inferior to that of our Projectile, it moves with exactly the same velocity."

"Captain," said Barbican, after a moment's reflection, "I know no more what that object is than you do, but I can understand very well why it keeps abreast with the Projectile."

"Very well then, why?"

"Because, my dear Captain, we are moving through a vacuum, and because all bodies fall or move—the same thing—with equal velocity through a vacuum, no matter what may be their shape or their specific gravity. It is the air alone that makes a difference of weight. Produce an artificial vacuum in a glass tube and you will see that all objects whatever falling through, whether bits of feather or grains of shot, move with precisely the same rapidity. Up here, in space, like cause and like effect."

"Correct," assented M'Nicholl. "Everything therefore that we shall throw out of the Projectile is bound to accompany us to the Moon."

"Well, we were smart!" cried Ardan suddenly.

"How so, friend Michael?" asked Barbican.

"Why not have packed the Projectile with ever so many useful objects, books, instruments, tools, et cetera, and fling them out into space once we were fairly started! They would have all followed us safely! Nothing would have been lost! And—now I think on it—why not fling ourselves out through the window? Shouldn't we be as safe out there as that bolide? What fun it would be to feel ourselves sustained and upborne in the ether, more highly favored even than the birds, who must keep on flapping their wings continually to prevent themselves from falling!"

"Very true, my dear boy," observed Barbican; "but how could we breathe?"

"It's a fact," exclaimed the Frenchman. "Hang the air for spoiling our fun! So we must remain shut up in our Projectile?"

"Not a doubt of it!"

—"Oh Thunder!" roared Ardan, suddenly striking his forehead.

"What ails you?" asked the Captain, somewhat surprised.

"Now I know what that bolide of ours is! Why didn't we think of it before? It is no asteroid! It is no particle of meteoric matter! Nor is it a piece of a shattered planet!"

"What is it then?" asked both of his companions in one voice.

SATELLITE'S BODY FLYING THROUGH SPACE.

"It is nothing more or less than the body of the dog that we threw out yesterday!"

So in fact it was. That shapeless, unrecognizable mass, melted, expunged, flat as a bladder under an unexhausted receiver, drained of its air, was poor Satellite's body, flying like a rocket through space, and rising higher and higher in close company with the rapidly ascending Projectile!