All Around the Moon, by Jules Verne

CHAPTER III.

THEY MAKE THEMSELVES AT HOME AND FEEL QUITE COMFORTABLE.

This curious explanation given, and its soundness immediately recognized, the three friends were soon fast wrapped in the arms of Morpheus. Where in fact could they have found a spot more favorable for undisturbed repose? On land, where the dwellings, whether in populous city or lonely country, continually experience every shock that thrills the Earth's crust? At sea, where between waves or winds or paddles or screws or machinery, everything is tremor, quiver or jar? In the air, where the balloon is incessantly twirling, oscillating, on account of the ever varying strata of different densities, and even occasionally threatening to spill you out? The Projectile alone, floating grandly through the absolute void, in the midst of the profoundest silence, could offer to its inmates the possibility of enjoying slumber the most complete, repose the most profound.

There is no telling how long our three daring travellers would have continued to enjoy their sleep, if it had not been suddenly terminated by an unexpected noise about seven o'clock in the morning of December 2nd, eight hours after their departure.

This noise was most decidedly of barking.

"The dogs! It's the dogs!" cried Ardan, springing up at a bound.

"They must be hungry!" observed the Captain.

"We have forgotten the poor creatures!" cried Barbican.

"Where can they have gone to?" asked Ardan, looking for them in all directions.

At last they found one of them hiding under the sofa. Thunderstruck and perfectly bewildered by the terrible shock, the poor animal had kept close in its hiding place, never daring to utter a sound, until at last the pangs of hunger had proved too strong even for its fright.

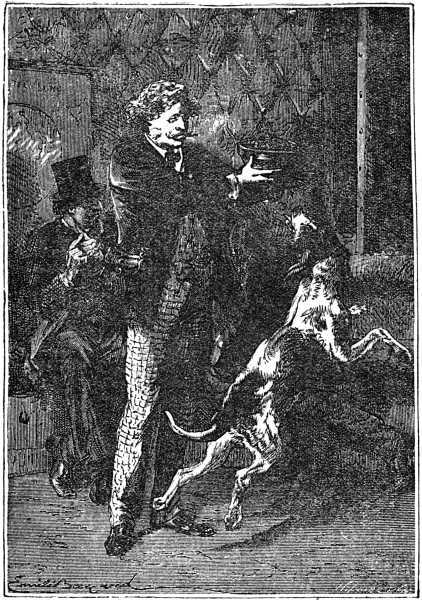

They readily recognized the amiable Diana, but they could not allure the shivering, whining animal from her retreat without a good deal of coaxing. Ardan talked to her in his most honeyed and seductive accents, while trying to pull her out by the neck.

"Come out to your friends, charming Diana," he went on, "come out, my beauty, destined for a lofty niche in the temple of canine glory! Come out, worthy scion of a race deemed worthy by the Egyptians to be a companion of the great god, Anubis, by the Christians, to be a friend of the good Saint Roch! Come out and partake of a glory before which the stars of Montargis and of St. Bernard shall henceforward pale their ineffectual fire! Come out, my lady, and let me think o'er the countless multiplication of thy species, so that, while sailing through the interplanetary spaces, we may indulge in endless flights of fancy on the number and variety of thy descendants who will ere long render the Selenitic atmosphere vocal with canine ululation!"

MORE HUNGRY THAN EITHER.

Diana, whether flattered or not, allowed herself to be dragged out, still uttering short, plaintive whines. A hasty examination satisfying her friends that she was more frightened than hurt and more hungry than either, they continued their search for her companion.

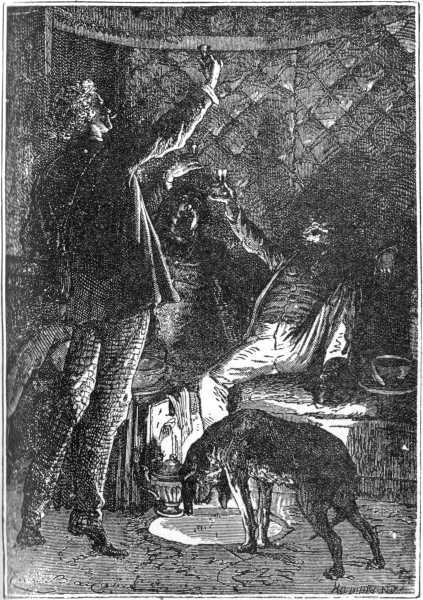

"Satellite! Satellite! Step this way, sir!" cried Ardan. But no Satellite appeared and, what was worse, not the slightest sound indicated his presence. At last he was discovered on a ledge in the upper portion of the Projectile, whither he had been shot by the terrible concussion. Less fortunate than his female companion, the poor fellow had received a frightful shock and his life was evidently in great danger.

"The acclimatization project looks shaky!" cried Ardan, handing the animal very carefully and tenderly to the others. Poor Satellite's head had been crushed against the roof, but, though recovery seemed hopeless, they laid the body on a soft cushion, and soon had the satisfaction of hearing it give vent to a slight sigh.

"Good!" said Ardan, "while there's life there's hope. You must not die yet, old boy. We shall nurse you. We know our duty and shall not shirk the responsibility. I should rather lose the right arm off my body than be the cause of your death, poor Satellite! Try a little water?"

The suffering creature swallowed the cool draught with evident avidity, then sunk into a deep slumber.

The friends, sitting around and having nothing more to do, looked out of the window and began once more to watch the Earth and the Moon with great attention. The glittering crescent of the Earth was evidently narrower than it had been the preceding evening, but its volume was still enormous when compared to the Lunar crescent, which was now rapidly assuming the proportions of a perfect circle.

"By Jove," suddenly exclaimed Ardan, "why didn't we start at the moment of Full Earth?—that is when our globe and the Sun were in opposition?"

"Why should we!" growled M'Nicholl.

"Because in that case we should be now looking at the great continents and the great seas in a new light—the former glittering under the solar rays, the latter darker and somewhat shaded, as we see them on certain maps. How I should like to get a glimpse at those poles of the Earth, on which the eye of man has never yet lighted!"

"True," replied Barbican, "but if the Earth had been Full, the Moon would have been New, that is to say, invisible to us on account of solar irradiation. Of the two it is much preferable to be able to keep the point of arrival in view rather than the point of departure."

"You're right, Barbican," observed the Captain; "besides, once we're in the Moon, the long Lunar night will give us plenty of time to gaze our full at yonder great celestial body, our former home, and still swarming with our fellow beings."

"Our fellow beings no longer, dear boy!" cried Ardan. "We inhabit a new world peopled by ourselves alone, the Projectile! Ardan is Barbican's fellow being, and Barbican M'Nicholl's. Beyond us, outside us, humanity ends, and we are now the only inhabitants of this microcosm, and so we shall continue till the moment when we become Selenites pure and simple."

"Which shall be in about eighty-eight hours from now," replied the Captain.

"Which is as much as to say—?" asked Ardan.

"That it is half past eight," replied M'Nicholl.

"My regular hour for breakfast," exclaimed Ardan, "and I don't see the shadow of a reason for changing it now."

The proposition was most acceptable, especially to the Captain, who frequently boasted that, whether on land or water, on mountain summits or in the depths of mines, he had never missed a meal in all his life. In escaping from the Earth, our travellers felt that they had by no means escaped from the laws of humanity, and their stomachs now called on them lustily to fill the aching void. Ardan, as a Frenchman, claimed the post of chief cook, an important office, but his companions yielded it with alacrity. The gas furnished the requisite heat, and the provision chest supplied the materials for their first repast. They commenced with three plates of excellent soup, extracted from Liebig's precious tablets, prepared from the best beef that ever roamed over the Pampas.

To this succeeded several tenderloin beefsteaks, which, though reduced to a small bulk by the hydraulic engines of the American Dessicating Company, were pronounced to be fully as tender, juicy and savory as if they had just left the gridiron of a London Club House. Ardan even swore that they were "bleeding," and the others were too busy to contradict him.

Preserved vegetables of various kinds, "fresher than nature," according to Ardan, gave an agreeable variety to the entertainment, and these were followed by several cups of magnificent tea, unanimously allowed to be the best they had ever tasted. It was an odoriferous young hyson gathered that very year, and presented to the Emperor of Russia by the famous rebel chief Yakub Kushbegi, and of which Alexander had expressed himself as very happy in being able to send a few boxes to his friend, the distinguished President of the Baltimore Gun Club. To crown the meal, Ardan unearthed an exquisite bottle of Chambertin, and, in glasses sparkling with the richest juice of the Cote d'or, the travellers drank to the speedy union of the Earth and her satellite.

And, as if his work among the generous vineyards of Burgundy had not been enough to show his interest in the matter, even the Sun wished to join the party. Precisely at this moment, the Projectile beginning to leave the conical shadow cast by the Earth, the rays of the glorious King of Day struck its lower surface, not obliquely, but perpendicularly, on account of the slight obliquity of the Moon's orbit with that of the Earth.

TO THE UNION OF THE EARTH AND HER SATELLITE.

"The Sun," cried Ardan.

"Of course," said Barbican, looking at his watch, "he's exactly up to time."

"How is it that we see him only through the bottom light of our Projectile?" asked Ardan.

"A moment's reflection must tell you," replied Barbican, "that when we started last night, the Sun was almost directly below us; therefore, as we continue to move in a straight line, he must still be in our rear."

"That's clear enough," said the Captain, "but another consideration, I'm free to say, rather perplexes me. Since our Earth lies between us and the Sun, why don't we see the sunlight forming a great ring around the globe, in other words, instead of the full Sun that we plainly see there below, why do we not witness an annular eclipse?"

"Your cool, clear head has not yet quite recovered from the shock, my dear Captain;" replied Barbican, with a smile. "For two reasons we can't see the ring eclipse: on account of the angle the Moon's orbit makes with the Earth, the three bodies are not at present in a direct line; we, therefore, see the Sun a little to the west of the earth; secondly, even if they were exactly in a straight line, we should still be far from the point whence an annular eclipse would be visible."

"That's true," said Ardan; "the cone of the Earth's shadow must extend far beyond the Moon."

"Nearly four times as far," said Barbican; "still, as the Moon's orbit and the Earth's do not lie in exactly the same plane, a Lunar eclipse can occur only when the nodes coincide with the period of the Full Moon, which is generally twice, never more than three times in a year. If we had started about four days before the occurrence of a Lunar eclipse, we should travel all the time in the dark. This would have been obnoxious for many reasons."

"One, for instance?"

"An evident one is that, though at the present moment we are moving through a vacuum, our Projectile, steeped in the solar rays, revels in their light and heat. Hence great saving in gas, an important point in our household economy."

In effect, the solar rays, tempered by no genial medium like our atmosphere, soon began to glare and glow with such intensity, that the Projectile under their influence, felt like suddenly passing from winter to summer. Between the Moon overhead and the Sun beneath it was actually inundated with fiery rays.

"One feels good here," cried the Captain, rubbing his hands.

"A little too good," cried Ardan. "It's already like a hot-house. With a little garden clay, I could raise you a splendid crop of peas in twenty-four hours. I hope in heaven the walls of our Projectile won't melt like wax!"

"Don't be alarmed, dear friend," observed Barbican, quietly. "The Projectile has seen the worst as far as heat is concerned; when tearing through the atmosphere, she endured a temperature with which what she is liable to at present stands no comparison. In fact, I should not be astonished if, in the eyes of our friends at Stony Hill, it had resembled for a moment or two a red-hot meteor."

"Poor Marston must have looked on us as roasted alive!" observed Ardan.

"What could have saved us I'm sure I can't tell," replied Barbican. "I must acknowledge that against such a danger, I had made no provision whatever."

"I knew all about it," said the Captain, "and on the strength of it, I had laid my fifth wager."

"Probably," laughed Ardan, "there was not time enough to get grilled in: I have heard of men who dipped their fingers into molten iron with impunity."

Whilst Ardan and the Captain were arguing the point, Barbican began busying himself in making everything as comfortable as if, instead of a four days' journey, one of four years was contemplated. The reader, no doubt, remembers that the floor of the Projectile contained about 50 square feet; that the chamber was nine feet high; that space was economized as much as possible, nothing but the most absolute necessities being admitted, of which each was kept strictly in its own place; therefore, the travellers had room enough to move around in with a certain liberty. The thick glass window in the floor was quite as solid as any other part of it; but the Sun, streaming in from below, lit up the Projectile strangely, producing some very singular and startling effects of light appearing to come in by the wrong way.

The first thing now to be done was to see after the water cask and the provision chest. They were not injured in the slightest respect, thanks to the means taken to counteract the shock. The provisions were in good condition, and abundant enough to supply the travellers for a whole year—Barbican having taken care to be on the safe side, in case the Projectile might land in a deserted region of the Moon. As for the water and the other liquors, the travellers had enough only for two months. Relying on the latest observations of astronomers, they had convinced themselves that the Moon's atmosphere, being heavy, dense and thick in the deep valleys, springs and streams of water could hardly fail to show themselves there. During the journey, therefore, and for the first year of their installation on the Lunar continent, the daring travellers would be pretty safe from all danger of hunger or thirst.

The air supply proved also to be quite satisfactory. The Reiset and Regnault apparatus for producing oxygen contained a supply of chlorate of potash sufficient for two months. As the productive material had to be maintained at a temperature of between 7 and 8 hundred degrees Fahr., a steady consumption of gas was required; but here too the supply far exceeded the demand. The whole arrangement worked charmingly, requiring only an odd glance now and then. The high temperature changing the chlorate into a chloride, the oxygen was disengaged gradually but abundantly, every eighteen pounds of chlorate of potash, furnishing the seven pounds of oxygen necessary for the daily consumption of the inmates of the Projectile.

Still—as the reader need hardly be reminded—it was not sufficient to renew the exhausted oxygen; the complete purification of the air required the absorption of the carbonic acid, exhaled from the lungs. For nearly 12 hours the atmosphere had been gradually becoming more and more charged with this deleterious gas, produced from the combustion of the blood by the inspired oxygen. The Captain soon saw this, by noticing with what difficulty Diana was panting. She even appeared to be smothering, for the carbonic acid—as in the famous Grotto del Cane on the banks of Lake Agnano, near Naples—was collecting like water on the floor of the Projectile, on account of its great specific gravity. It already threatened the poor dog's life, though not yet endangering that of her masters. The Captain, seeing this state of things, hastily laid on the floor one or two cups containing caustic potash and water, and stirred the mixture gently: this substance, having a powerful affinity for carbonic acid, greedily absorbed it, and after a few moments the air was completely purified.

The others had begun by this time to check off the state of the instruments. The thermometer and the barometer were all right, except one self-recorder of which the glass had got broken. An excellent aneroid barometer, taken safe and sound out of its wadded box, was carefully hung on a hook in the wall. It marked not only the pressure of the air in the Projectile, but also the quantity of the watery vapor that it contained. The needle, oscillating a little beyond thirty, pointed pretty steadily at "Fair."

The mariner's compasses were also found to be quite free from injury. It is, of course, hardly necessary to say that the needles pointed in no particular direction, the magnetic pole of the Earth being unable at such a distance to exercise any appreciable influence on them. But when brought to the Moon, it was expected that these compasses, once more subjected to the influence of the current, would attest certain phenomena. In any case, it would be interesting to verify if the Earth and her satellite were similarly affected by the magnetic forces.

A hypsometer, or instrument for ascertaining the heights of the Lunar mountains by the barometric pressure under which water boils, a sextant to measure the altitude of the Sun, a theodolite for taking horizontal or vertical angles, telescopes, of indispensable necessity when the travellers should approach the Moon,—all these instruments, carefully examined, were found to be still in perfect working order, notwithstanding the violence of the terrible shock at the start.

As to the picks, spades, and other tools that had been carefully selected by the Captain; also the bags of various kinds of grain and the bundles of various kinds of shrubs, which Ardan expected to transplant to the Lunar plains—they were all still safe in their places around the upper corners of the Projectile.

Some other articles were also up there which evidently possessed great interest for the Frenchman. What they were nobody else seemed to know, and he seemed to be in no hurry to tell. Every now and then, he would climb up, by means of iron pins fixed in the wall, to inspect his treasures; whatever they were, he arranged them and rearranged them with evident pleasure, and as he rapidly passed a careful hand through certain mysterious boxes, he joyfully sang in the falsest possible of false voices the lively piece from Nicolo:

Le temps est beau, la route est belle,

La promenade est un plaisir.

The day is bright, our hearts are light.

How sweet to rove through wood and dell.

or the well known air in Mignon:

Legères hirondelles,

Oiseaux bénis de Dieu,

Ouvrez-ouvrez vos ailes,

Envolez-vous! adieu!

Farewell, happy Swallows, farewell!

With summer for ever to dwell

Ye leave our northern strand

For the genial southern land

Balmy with breezes bland.

Return? Ah, who can tell?

Farewell, happy Swallows, farewell!

Barbican was much gratified to find that his rockets and other fireworks had not received the least injury. He relied upon them for the performance of a very important service as soon as the Projectile, having passed the point of neutral attraction between the Earth and the Moon, would begin to fall with accelerated velocity towards the Lunar surface. This descent, though—thanks to the respective volumes of the attracting bodies—six times less rapid than it would have been on the surface of the Earth, would still be violent enough to dash the Projectile into a thousand pieces. But Barbican confidently expected by means of his powerful rockets to offer very considerable obstruction to the violence of this fall, if not to counteract its terrible effects altogether.

The inspection having thus given general satisfaction, the travellers once more set themselves to watching external space through the lights in the sides and the floor of the Projectile.

Everything still appeared to be in the same state as before. Nothing was changed. The vast arch of the celestial dome glittered with stars, and constellations blazed with a light clear and pure enough to throw an astronomer into an ecstasy of admiration. Below them shone the Sun, like the mouth of a white-hot furnace, his dazzling disc defined sharply on the pitch-black back-ground of the sky. Above them the Moon, reflecting back his rays from her glowing surface, appeared to stand motionless in the midst of the starry host.

A little to the east of the Sun, they could see a pretty large dark spot, like a hole in the sky, the broad silver fringe on one edge fading off into a faint glimmering mist on the other—it was the Earth. Here and there in all directions, nebulous masses gleamed like large flakes of star dust, in which, from nadir to zenith, the eye could trace without a break that vast ring of impalpable star powder, the famous Milky Way, through the midst of which the beams of our glorious Sun struggle with the dusky pallor of a star of only the fourth magnitude.

Our observers were never weary of gazing on this magnificent and novel spectacle, of the grandeur of which, it is hardly necessary to say, no description can give an adequate idea. What profound reflections it suggested to their understandings! What vivid emotions it enkindled in their imaginations! Barbican, desirous of commenting the story of the journey while still influenced by these inspiring impressions, noted carefully hour by hour every fact that signalized the beginning of his enterprise. He wrote out his notes very carefully and systematically, his round full hand, as business-like as ever, never betraying the slightest emotion.

The Captain was quite as busy, but in a different way. Pulling out his tablets, he reviewed his calculations regarding the motion of projectiles, their velocities, ranges and paths, their retardations and their accelerations, jotting down the figures with a rapidity wonderful to behold. Ardan neither wrote nor calculated, but kept up an incessant fire of small talk, now with Barbican, who hardly ever answered him, now with M'Nicholl, who never heard him, occasionally with Diana, who never understood him, but oftenest with himself, because, as he said, he liked not only to talk to a sensible man but also to hear what a sensible man had to say. He never stood still for a moment, but kept "bobbing around" with the effervescent briskness of a bee, at one time roosting at the top of the ladder, at another peering through the floor light, now to the right, then to the left, always humming scraps from the Opera Bouffe, but never changing the air. In the small space which was then a whole world to the travellers, he represented to the life the animation and loquacity of the French, and I need hardly say he played his part to perfection.

The eventful day, or, to speak more correctly, the space of twelve hours which with us forms a day, ended for our travellers with an abundant supper, exquisitely cooked. It was highly enjoyed.

No incident had yet occurred of a nature calculated to shake their confidence. Apprehending none therefore, full of hope rather and already certain of success, they were soon lost in a peaceful slumber, whilst the Projectile, moving rapidly, though with a velocity uniformly retarding, still cleaved its way through the pathless regions of the empyrean.