Teutonic Myth and Legend by Donald Mackenzie

CHAPTER XX

Beowulf and the Dragon

Beowulf in Battle--He becomes King of the Geats--A Slave's Discovery --Theft of Treasure--The Dragon devastates the Kingdom --Beowulf is angered--He sets forth to slay the Monster--Address to his Followers--The Dragon comes forth--The Great Conflict--Flight of Followers--The single Faithful Knight--He helps the King--Dragon slain--The Treasure--Beowulf's Death--Wiglaf reproaches the Battle Laggards--How the People sorrowed.

BEOWULF gave faithful service to Hygelac. In peace he was his wise counsellor, and in war his right-hand battle man. Then did the king fall fighting against the Frisians and Hugs. His death was avenged by Beowulf on the field, for he seized Dœghrefn, the hero of the Hugs, and slew him, not with his sword. "I grasped him," the hero could boast; "his beating heart I stilled. I crushed his bones." Then swam Beowulf away towards home, escaping unscathed, and bearing with him the armour of thirty warriors.

Queen Hygd mourned the king's death, and to Beowulf made offer of the kingdom, but he chose to be faithful to Hygelac, and protected his young son, Heardred, until he grew to years of wisdom and strength. But the young king was slain by Eanmund, and Beowulf was given the throne. He avenged the death of Heardred by slaying his murderer's brother, Eadgils.

For fifty winters did Beowulf reign wisely and well. Then a great dragon began to ravage his country with fire. Alone did the monarch combat against it, and in the end was the victor. But he paid life's cost for his triumph.

Now the dragon had its dwelling in a secret cavern beneath a grey rock, on the shoreland of a lonely, upland moor. No man knew the path thither. It chanced then that a slave who had been sorely beaten by his master fled towards the untrodden solitudes, and he came to the dragon's lair while yet the monster slept. Quaking with fear, he beheld it there guarding rich treasure which had been hidden in ancient days by a prince, the last of his race. All his people had fallen in a great war, and he wandered about alone mourning for his friends. Then he hid the treasures of the tribe where the slave found them. Armour and great swords were there, a banner of gold that lit up the cavern, golden cups, and many gems and. ornaments, collars and brooches, the work of giants in ancient times.

The ancient dragon which went forth by night wrapped in fiery flame found the treasure unprotected, and from that hour became the guardian of it.

Now the slave who discovered the monster's lair had more greed than fear in his heart as he gazed upon the hoard. So he went lightly past the dragon's head and seized a rich golden cup, and fled away over the rocks. To his master he carried the treasure, and thus secured his pardon and goodwill.

The dragon soon afterwards awoke. He smelt along the rocks; he saw the footprints of the man on the ground, and searched for him angrily. Round about the monster went, but saw no one in that dismal solitude. Hot was the dragon's heart with desire for conflict. Then he returned to the cavern and found that the treasure had been rifled. Great was his wrath thereat, and he panted to be avenged. So waited he for nightfall, when he could go forth against mankind.

In the thick darkness the great dragon flew over the land. He vomited coals of fire over many a fair home. The flames made lurid blaze against the sky, and men were terror-stricken. It seemed that the night flyer was resolved not to leave aught alive, for far and near the countryside blazed before him. Great harm, indeed, did he accomplish in his fierce hate for the people of Geatland.

All night long the raging flames swept the land, and far and near they wrought disaster. Not until it was very nigh unto dawn did the dragon cease his vengeful work and take swift departure to its lair. Great faith had he in the security of his hiding place, but his faith proved to be futile.

To Beowulf the grievous tidings of the night horrors were sent quickly. His own country dwelling, the gift of the Geats, was smouldering in fire. Sorrow-stricken, indeed was the brave old king; no greater grief could have befallen him. In deep gloom he sat alone, who was wont to be cheerful, wondering by what offence he had made angry the Almighty, the Everlasting Lord.

The fire drake had burned up the people's stronghold; the sea-skirting land was devastated. Waves washed inland. . . . Beowulf was filled with anger against the monster, and resolved to be avenged. So he began to make ready for the combat. He bade that a shield of iron be made for him, for a wooden shield would be of no avail against raging fire. . . . Alas! the valiant hero was doomed to come ere long to life's sad end, as was also the serpent fiend who had for so long kept guard over the secret hoard. . . .

Beowulf scorned to attack the flying monster with a host of war men; he had no fear of going forth alone, no dread of single combat, nor did he hold the battle powers of the dragon as of high account. Many conflicts and many war-fights he had survived unscathed since he, the hero of many frays, had cleansed Heorot and wrestled in combat with Grendel, the hated fiend.

Twelve valiant and true war men he selected to go with him against the fire drake. And as he had come to know how its dread vengeance had been stirred up against his people, he took with him also the slave who had rifled the treasure, so that he might be a guide to lead them unto the monster's den. A sorrowful heart was in th at poor man; abject and trembling he showed the way, much against his will, to the mound in which was the treasure, while underneath the dragon kept guard. It was on a rocky shoreland where the waves bellowed in unceasing strife.

Beowulf sat on the grey cliff looking over the sea. His hearth comrades were about him, and he spoke to them words of farewell, for he knew that Wyrd had tied fast the life thread of his web. His soul was sad and restless, and he was ready to go hence. Not long after that his spirit departed the flesh.

Of his whole life the king spake, recounting the long service he had accomplished since that he was but seven years old, when King Hrethel took him from his father and gave him, food and pay, mindful of his kinship. Of his deeds of valour he spoke, and life's afflictions, and touchingly he told of a father's sorrow when his son was taken from him. Such an one in his old age remembered every morn the lost lad. For another he had no desire. With sorrow he beheld his son's empty home, with deserted wine hall that heard but the moaning winds, for the horseman and hero slept in the grave, and no longer was heard the harp's music and the voices of men making merry.

'Twas thus he spake of Hrethel, the king who sorrowed when his son was slain and avenged not; abandoning the world the stricken monarch sought a solitary place in which to end his days.

Then spake Beowulf of Hygelac, whom he served and did avenge, and his son whom he avenged also.

"When yet young," the hero said, "I fought many battles, and now when I am old I seek fame in combat with the dragon, if he but come from his underground dwelling."

He must needs, Beowulf told his followers, wear his armour in that last fray. Naked he fought with Grendel, but now he must stand against consuming flame.

"I shall draw not back a foot's space," he said boldly and with calm demeanour, "nor shall I flee before the watcher of treasure; before the rock it shall be as Wyrd 1 decrees--Wyrd who measures out a man's life. . . . Ready am I, and I boast not before the dragon. . . . Ye warriors in armour, watch ye from the mound, so that ye may perceive which of us is best able to survive the strife after deadly attack. . . It is not for one of you to fight as I must fight; the adventure is for me only. . . . Gold shall I win for triumph, and death is my due if I fail. . . ."

Then fully armoured under his strong helmet, his shield on his left arm, his sword by his side, the valorous hero of the Geats went down the cliff path towards the dragon's cavern. . . . He saw the stream which flowed from the stone ramparts steaming hot with deadly fire; nigh to the hoard he could not endure long the flame of the dragon.

But filled was his great heart with battle fury. A storm-like shout he gave--a strong battlecry that went under the grey stone. . . . In wrath the monster heard him; he knew the voice of man. . . . Nor was there time then to seek peace. Fiery flame issued forth first: it was the dragon's battle breath. . . . The earth shook. . . . Beowulf stood waiting, his iron shield upraised. . . . The monster curled itself to spring; Beowulf waited in his armour. . . .

Then forth came the wriggling monster--swiftly to his fate he came. The shield gave that strong hero good defence against the flame. His sword was drawn, and it was an ancient heritage, keen-edged and sure. . . . Both the king and the dragon were bent on slaughter; each feared the other.

Beowulf swung his great sword, and smote the dragon's head, but the blade glanced from the bone, for Wyrd did not decree otherwise. Then the hero was enveloped in fire, for in wrath at the blow the monster spouted flame far and wide. Greatly did the brave one suffer. . . . His followers standing on the mound were terror-stricken; to the wood they fled, fearing for their lives.

But one remained; he alone sorrowed and sought to help the king. He was named Wiglaf, a shield warrior, a well-loved lord of Scyldings. He remembered the honours and the gifts which Beowulf had bestowed upon him. . . . He could not hold back; he grasped his wooden shield and drew his ancient sword--a giant's sword which Onela gave him. To his comrades he cried: "Promised we not to help our lord in time of need when with him we drank in the mead-hall? Rather would I perish in fire with our gold-giver than that we should return again with shields unscathed. . . . Advance then. Give help to our lord. . . Together shall we stand side by side behind the same defence."

So speaking, that young hero plunged through the death smoke, hastening to Beowulf's aid. Never before had Wiglaf fought at his chief's side.

"Beloved hero," Wiglaf spake, "do thy utmost as of yore. Let not thy honour fail. Put forth thy full strength and I shall help thee."

Then came the dragon to attack a second time. Brightly flamed the fire against his hated human foes. The young hero's wooden shield was burnt up, and behind Beowulf's he shielded himself.

Again Beowulf smote the dragon, but his grey sword, Naegling, snapped in twain, whereat the monster leapt on the lord of the Geats, and took that hero's neck in his horrible jaws, so that the king's life blood streamed over his armour. But Wiglaf smote low, and his sword pierced the dragon, so that the fire abated.

Beowulf drew his death dagger, and striking fiercely he cut the monster in twain. So was the dragon slain; so did the heroes achieve great victory and renown.

But the king was wounded unto death. The dragon's venom boiled in his blood, and he knew well that his end was nigh. Faint and heart-weary he went and sat down, gazing on the rocky arches of the dragon's lair, which giants had made. . . . Wiglaf came and washed the bloodstained king, who was weary after the conflict, and unloosed his helmet and took it off. Tenderly he ministered unto Beowulf in his last hour. Well knew the king that he was nigh unto death.

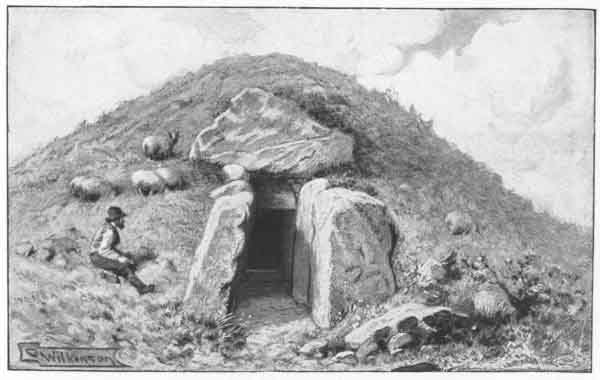

ENTRANCE TO PASSAGE-GRAVE AT UBY, DENMARK

The hiding place of Grendel--the dragon's den--was almost certainly a forgotten passage-grave, the treasure being the original gifts to the dead chieftain buried there

"It is now my desire," Beowulf said faintly, "to give unto my son, if it had been granted to me to have one, this my war armour. . . . For fifty winters I have ruled over my people, nor was there a king who dared come against me in battle. At home I waited my fateful hour, never seeking to make strife, nor ever breaking a pledged oath; so now when I am sick unto death I have comfort because the Ruler of all mankind can charge me not with murderous doings when I die."

Then he bade Wiglaf to bring forth the treasure from the dragon's lair, so that he might behold the riches he had won ere life was spent. The young hero did as was asked of him. He brought forth ancient armour, and vases of gold, rich ornaments and gems and many an armlet of rare design. A banner of gold which lit up the cavern he also bore to the king, in haste lest the last breath should be drawn ere he returned. . . . He found Beowulf gasping faintly, so once again he laved the king's face with cold water until he spake, gazing on the treasure, with thankfulness.

"To the Lord of glory I give thanks," he said, "because that he hath permitted me, ere I died, to win such great treasure for my own folk. . . . Give thou the gifts unto my people according to their needs. . . . I have paid life's cost for them. . . . No longer can I remain."

Then the king made request that on the cliff top overlooking the sea there should be raised his burial mound, and that it should be made bright with fire. He desired also that it should be built on Hronesness, as a memorial, so that seafarers, whose ships are driven through spray mist, might call it "Beowulf's Grave".

To Wiglaf the dying hero then gave his golden neck ring, his helmet adorned with gold, and his strong armour, which Weland had fashioned, bidding him to make ever good use of the gifts.

"The last of our race, the Wægmundings, art thou, O Wiglaf," Beowulf said faintly, as life ebbed low. "Wyrd took one by one away, each at his appointed hour; the nobles in their strength went to their doom. . . . Now must I follow them . . . ...

These were Beowulf's last words. His soul went forth from his body, to the doom of good men. . . . Wiglaf sat alone, mourning him.

Then came the battle laggards from the wood and approached Wiglaf, who spoke angrily to them, because that they had fled their lord in his hour of need. Nevermore, he vowed, would they receive gifts or lands; each one would, when the lords were told of their cowardice, be deprived of their possessions.

"For a noble warrior, Wiglaf cried, "death is better than a life of shame."

When the people heard that Beowulf was dead, they feared that their enemies would renew the blood feuds and come against them. The messenger whom Wiglaf sent to bear the sad tidings spake of wars to be, when many a maiden would be taken away to exile and many a warrior slain. Then would their ghosts lift up their spears; the harp would be heard not as it awakened warriors, but instead the blood-fed raven would ask how fared it with the eagle as it fought with the wolf to devour the slain.

In sadness and sharp grief the people went towards the dragon's lair, and they saw the dread monster that had been slain. In length it measured fifty feet; horrible it was and blackened with its own fire. Round the dead king they gathered, weeping sorrowfully, and Wiglaf spake, telling them of Beowulf's last words, and his desire that he should be buried in a high barrow at the place of the bale fire.

Then, while the bier was being made ready, Wiglaf led seven men into the cave, and what treasure remained they brought forth. The dragon was thrown into the sea, and the body of grey old Beowulf was borne to the headland which is called Hronesness.

A great pyre was built, and it was hung with armour and battle shields and bright helms. Reverently they laid the great king thereon--the well-loved lord for whom they mourned. . . . Never before was so large a pyre seen by men. Torches set it aflame, and soon the smoke rose thick and black above it; the roaring of flames mingled with the wailing of the mourners while the body of Beowulf was consumed. . . .

A doleful dirge sang the old queen, and again and again she said that oft had she dreaded the coming of conflict and much slaughter. She feared for her own shame and captivity.

Heaven swallowed the smoke. . . . The people then raised a grave mound of great height. For ten days they laboured constructing a wall which encircled the ashes. Much treasure did they lay in the mound--all that was in the hoard--and there the riches lie now of as little use to men as ever they were.

Twelve horsemen rode round the great mound on Hronesness 1 lamenting for their lord. All the people sorrowed together, and they said that Beowulf was of all the world's kings and of men the mildest and most gracious, the kindest unto his people and the keenest for their praise.

The Curse of Gold

The antique world, in his first flow'ring youth,

Found no defect in his Creator's grace;

But with glad thanks, and unreproved truth,

The gifts of sovran bounty did embrace:

Like angel's life was then men's happy case;

But later ages Pride, like corn-fed steed,

Abused her plenty and fat-swoll'n increase

To all licentious lust, and gan exceed

The measure of her mean and natural first need.

Then gan a cursed hand the quiet womb

Of his great grandmother with steel to wound,

And the hid treasures in her sacred tomb

With sacrilege to dig; therein he found

Fountains of gold and silver to abound,

Of which the matter of his huge desire

And pompous pride eftsoons he did compound;

Then Avarice gan through his veins inspire

His greedy flames, and kindled life-devouring fire.

"Son," said he 1 then, "let be thy bitter

scorn,

And leave the rudeness of that antique age

To them, that lived therein in state forlorn.

Thou, that doest live in later times must wage

Thy works for wealth, and life for gold engage."

--From Spenser's "Faerie Queene".

Footnotes

214:1 Urd.

219:1 Hronesness is translated "Whales' Ness" by some: others incline to the mythological rendering, Ran's Ness. Rydberg in this connection shows that Rhind's son, Vale, the wolf slayer, is called, by Saxo, Bous, the Latinized form for Beowulf. Stopford Brooke shows that Hronesness is next to Earnaness, Eagle's Ness, and considers that "the unmythological explanation is plainly right"."

220:1 Mammon (Mimer) to the knight Guyon.