The Ghost Ship, by John C. Hutcheson

Chapter II.

“Sail Ho!”

Away forward, I remember, the ship’s bell under the break of the forecastle, or “fo’c’s’le,” as it is pronounced in nautical fashion, was just striking “two bells” in the first day watch.

In other words, more suited to a landsman’s comprehension, it was five o’clock in the afternoon when I came on deck from my spell of leisure below, to relieve Mr. Spokeshave, the third officer, then on duty, and the sight I caught of the heavens, across the gangway, was so beautiful that I paused a moment or two to look at the sunset before going up on the bridge, where Mr. Spokeshave, I had no doubt, was anxiously awaiting me and, equally certainly, grumbling at my detaining him from his “tea!”

This gentleman, however, was not too particular as to time in relieving others when off watch, and I did not concern myself at all about Master “Conky,” as all of us called him aboard, on account of a very prominent, and, so to speak, striking feature of his countenance.

Otherwise, he was an insignificant-looking little chap, as thin as threadpaper and barely five feet high; but he was always swelling himself out, and trying to look a bigger personage than he was, with the exception that is, of his nose, which was thoroughly Napoleonic in size and contour. Altogether, what with the airs he gave himself and his selfish disposition and nasty cantankerous temper, Master Spokeshave was not a general favourite on board, although we did not quarrel openly with the little beggar or call him by his nickname when he was present, albeit he was very hard to bear with sometimes!

Well, not thinking of him or his tea or that it was time for me to go on watch, but awed by the majesty of God’s handiwork in the wonderful colouring, of the afterglow, which no mortal artist could have painted, no, none but He who limns the rainbow, I stood there so long by the gangway, gazing at the glorious panorama outspread before me, that I declare I clean forgot Spokeshave’s very existence, all-important though he considered himself, and I was only recalled to myself by the voice of Mr. Fosset, our first officer, who had approached without my seeing him, speaking close beside me.

Ah, he was a very different sort of fellow to little Spokeshave, being a nice, jolly, good-natured chap, chubby and brown-bearded, and liked by every one from the skipper down to the cabin boy. He was a bit obstinate, though, was Mr. Fosset; and “as pigheaded as a Scotch barber,” as Captain Applegarth would say sometimes when he was arguing with him, for the first mate would always stick to his own opinion, no matter if he were right or wrong, nothing said on the other side ever convincing him to the contrary and making him change his mind.

He had caught sight of me now leaning against the bulwarks and looking over the side amidships, just abaft the engine-room hatch, as he passed along the gangway towards the bridge which he was about to mount to have a look at the standard compass and see what course the helmsman was steering, on his way from the poop, where I had noticed him talking with the skipper as I came up the booby-hatch from below. “Hullo, Haldane!” he cried, shouting almost in my ear, and giving me a playful dig in the ribs at the same time; this nearly knocked all the breath out of my body. “Is that you, my boy?”

“Aye, aye, sir,” I replied, hesitating, for I was startled, alike by his rather too demonstrative greeting as well as his unexpected approach. “I—I—mean, yes, sir.”

Mr. Fosset laughed; a jolly, catching laugh it was—that of a man who had just dined comfortably and enjoyed his dinner, and did not have, apparently, a care in the world. “Why, what’s the matter with you, youngster?” said he in his chaffing way. “Been having a caulk on the sly and dreaming of home, I bet?”

“No, sir,” I answered gravely; “I’ve not been to sleep.”

“But you look quite dazed, my boy.”

I made no reply to this observation, and Mr. Fosset then dropped his bantering manner.

“Tell me,” said he kindly, “is there anything wrong with you below? Has that cross-grained little shrimp, Spokeshave, hang him! been bullying you again, like he did the other day?”

“Oh no, sir; he’s on the bridge now, and I ought to have relieved him before this,” I replied, only thinking of poor “Conky” and his tea then for the first time. “I wasn’t even dreaming of him; I’m sure I beg his pardon!”

“Well, you were dreaming of some one perhaps ‘nearer and dearer’ than Spokeshave,” rejoined Mr. Fosset, with another genial laugh. “You were quite in a brown study when I gave you that dig in the ribs. What’s the matter, my boy?”

“I was looking at that, sir,” said I simply, in response to his question, pointing upwards to the glory in the heavens. “Isn’t it grand? Isn’t it glorious?”

This was a poser; for the first mate, though good-natured and good-humoured enough, and probably a thinking man, too, in his way, was too matter-of-fact a person to indulge in “dreamy sentimentalities,” as he would have styled my deeper thoughts! A sunset to him was only a sunset, saving in so far as it served to denote any change of weather, which aspect his seaman’s eye readily took note of without any pointing out on my part; so he rather chilled my enthusiasm by his reply now to me.

“Oh, yes, it’s very fine and all that, youngster,” he observed in an off-hand manner that grated on my feelings, making me wish I had not spoken so gushingly. “I think that sky shows signs of a blow before the night is over, which will give you something better to do than star-gazing!”

“I can’t very well do that now, sir,” said I slily, with a grin at catching him tripping. “Why, the stars aren’t out yet.”

“That may be, Master Impudence,” replied Mr. Fosset, all genial again and laughing too; “but they’ll soon be popping out overhead.”

“But, sir, it is quite light still,” I persisted. “See, it is as bright as day all round, just as at noontide!”

“Aye, but it’ll be precious dark soon! It grows dusk in less than a jiffey after the sun dips in these latitudes at this time o’ year,” said he. “Hullo! I say, though, that reminds me, Haldane—”

“Of what, sir?” I asked as he stopped abruptly at this point. “Anything I can do for you, Mr. Fosset?”

“No, my boy, nothing,” he replied reflectively, and looking for the moment to be in as deep a brown study as he accused me of being just now. “Stop, though, I tell you what you can do. Run forwards and see what that lazy lubber of a lamp-trimmer is about. He’s always half an hour or so behind time, and seems to get later every day. Wake him up and make him hoist our masthead lantern and fix the side lights in position, for it’ll soon be dark, I bet ’ee, in spite of all that flare-up aloft over there, and we’re now getting in the track of the homeward-bounders crossing the Banks, and have to keep a sharp look-out and let ’em know where we are, to avoid any chance of collision.”

“Aye, aye, sir,” I cried, making my way along the gangway by the side of the deckhouse towards the fo’c’s’le, which was still lit up by the afterglow as if on fire. “I’ll see to it all right, and get our steam lights rigged up at once, sir.”

So saying, in another minute or so, scrambling over a lot of empty coal sacks and other loose gear that littered the deck, besides getting tripped up by the tackle of the ash hoist, which I did not see in time from the glare of the sky coming right in my eyes, I gained the lee side of the cook’s galley at the forward end of the deckhouse. Here, as I conjectured, I found old Greazer, our lamp-trimmer. This worthy, who was quite a character in his way, was a superannuated fireman belonging to the line, whom age and long years of toil had unfitted for the rougher and more arduous duties of his vocation in the stoke-hold, and who now, instead of trimming coals in the furnaces below, trimmed wicks and attended to the lamps about the ship, on deck and elsewhere. He managed, I may add, to make his face so dirty in the carrying out of the lighter duties to which he was now called, probably in fond recollection of his byegone grimy task in the engine-room, that his somewhat personal cognomen was very appropriate, his countenance being oily and smutty to a degree!

He was a very lazy old chap, however; and, in lieu of attending to his work, was generally to be found confabulating with our mulatto cook, Accra Prout, as I discovered him now, more bent on worming out an extra lot of grog from the chef of the galley in exchange for a lump of “hard” tobacco, than thinking of masthead lanterns or the ship’s side lights, green and red.

“What are you about, lamp-trimmer?” I called out sharply on catching sight of him palavering there with the mulatto, the artful beggar furtively slipping the tin pannikin out of which he had been drinking into the bosom of his jumper. “Here’s two bells struck and no lights up!”

“Two bells, sir?”

“Aye, two bells,” I repeated, taking no notice of his affected air of surprise. “There’s the ship’s bell right over your head where you stand, and you must have heard it strike not five minutes ago.”

“Lor’, Master Dick, may I die a foul death ashore if I ever heard a stroke,” he replied as innocently as you please. “Howsomdever, the lamps is all right, sir. I ain’t ’ave forgot ’em.”

“That’s all right, then, Greazer,” I said, not being too hard on him, and excusing the sly wink he gave to Prout as he told his barefaced banger about not hearing the bell, in memory of his past services. “Come along now and rig them up smart, or you’ll have Mr. Fosset after you.”

Making him hoist our masthead light on the foremast, twenty feet above the deck, according to the usual Board of Trade regulations for steamers under way at sea, I then marched him before me along the deck and saw him place our side lights in their proper position, the green one to starboard and the red on our port hand.

Old Greazer then mounted the bridge-ladder, in advance of me, with the binnacle lamp in his hand to put that in its place, and, as I followed slowly in his slow footsteps, for the ex-fireman was not now quick of movement, an accident in the stoke-hold having crippled him years ago, I half-turned round as I ascended the laddering to have a look again at the horizon to leeward over our port quarters, when I fancied, when advancing a foot with the lamp-trimmer, I had seen something to the southward.

In another instant my fancy became a certainty.

Yes, there, in the distance, sailing at an angle to our course, right before the wind, was a large full-rigged ship. Everything, though, was not right with her, as I noted the moment I made her out, with her white canvas all crimson from a last expiring gleam of the afterglow; for I could see that her sails were tattered and torn, with the ragged ends blowing out loose from the boltropes in the most untidy fashion, unkempt, uncared for!

Besides, she was flying a signal of distress, patent to every sailor that has ever crossed the seas.

Her flag was hoisted half-mast high from the peak halliards. Half-mast high!

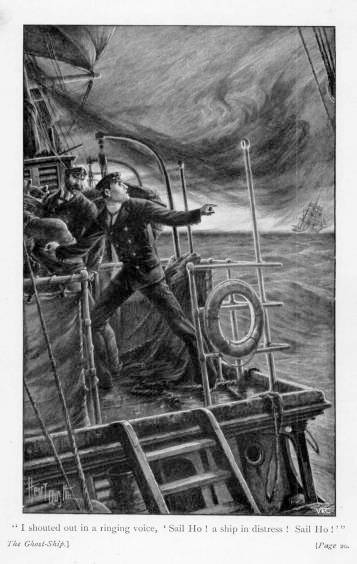

I did not wait, nor did I want, to see anything further. No, that was enough for me; and, springing on to the bridge with a bound that nearly knocked poor old Greazer down on his marrowbones as he stopped to put the lantern into the binnacle, I shouted out in a ringing voice that echoed fore and aft, startling everybody aboard, even myself, “Sail ho! A ship in distress! Sail ho!”