|

|

Folkways, by William Graham Sumner

A Study of the Sociological Importance of Usages,

Manners, Customs, Mores, and Morals

CHAPTER I

FUNDAMENTAL NOTIONS OF THE FOLKWAYS AND OF THE MORES

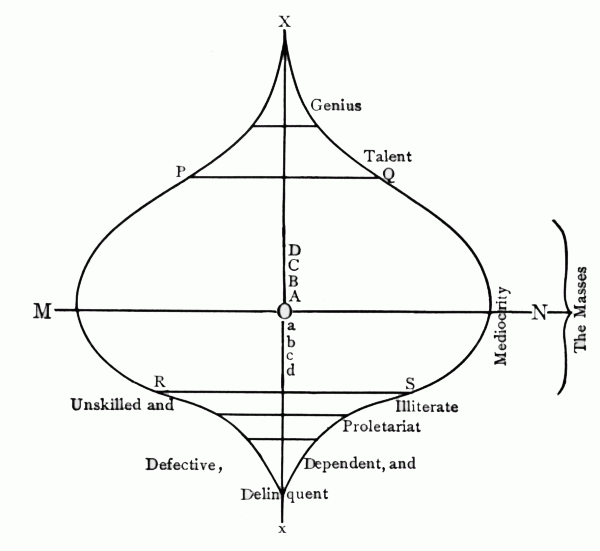

Definition and mode of origin of the folkways. — The folkways are a societal force. — Folkways are made unconsciously. — Impulse and instinct; primeval stupidity; magic. — The strain of improvement and consistency. — The aleatory element. — All origins are lost in mystery. — Spencer on primitive custom. — Good and bad luck; ills of life; goodness and happiness. — Illustrations. — Immortality and compensation. — Tradition and its restraints. — The concepts of "primitive society"; "we-groups" and "others-groups." — Sentiments in the in-group towards out-groups. — Ethnocentrism. — Illustrations. — Patriotism. — Chauvinism. — The struggle for existence and the competition of life; antagonistic coöperation. — Four motives: hunger, love, vanity, fear. — The process of making folkways. — Suggestion and suggestibility. — Suggestion in education. — Manias. — Suggestion in politics. — Suggestion and criticism. — Folkways based on false inferences. — Harmful folkways. — How "true" and "right" are found. — The folkways are right; rights; morals. — The folkways are true. — Relations of world philosophy to folkways. — Definition of the mores. — Taboos. — No primitive philosophizing; myths; fables; notion of social welfare. — The imaginative element. — The ethical policy and the success policy. — Recapitulation. — Scope and method of the mores. — Integration of the mores of a group or age. — Purpose of the present work. — Why use the word "mores." — The mores are a directive force. — Consistency in the mores. — The mores of subgroups. — What are classes? — Classes rated by societal value. — Class; race; group solidarity. — The masses and the mores. — Fallacies about the classes and the masses. — Action of the masses on ideas. — Organization of the masses. — Institutions of civil liberty. — The common man. — The "people"; popular impulses. — Agitation. — The ruling element in the masses. — The mores and institutions. — Laws. — How laws and institutions differ from mores. — Difference between mores and some cognate things. — Goodness or badness of the mores. — More exact definition of the mores. — Ritual. — The ritual of the mores. — Group interests and policy. — Group interests and folkways. — Force in the folkways. — Might and right. — Status. — Conventionalization. — Conventions indispensable. — The "ethos" or group character; Japan. — Chinese ethos. — Hindoo ethos. — European ethos.

21. Definition and mode of origin of the folkways. If we put together all that we have learned from anthropology and ethnography about primitive men and primitive society, we perceive that the first task of life is to live. Men begin with acts, not with thoughts. Every moment brings necessities which must be satisfied at once. Need was the first experience, and it was followed at once by a blundering effort to satisfy it. It is generally taken for granted that men inherited some guiding instincts from their beast ancestry, and it may be true, although it has never been proved. If there were such inheritances, they controlled and aided the first efforts to satisfy needs. Analogy makes it easy to assume that the ways of beasts had produced channels of habit and predisposition along which dexterities and other psychophysical activities would run easily. Experiments with newborn animals show that in the absence of any experience of the relation of means to ends, efforts to satisfy needs are clumsy and blundering. The method is that of trial and failure, which produces repeated pain, loss, and disappointments. Nevertheless, it is a method of rude experiment and selection. The earliest efforts of men were of this kind. Need was the impelling force. Pleasure and pain, on the one side and the other, were the rude constraints which defined the line on which efforts must proceed. The ability to distinguish between pleasure and pain is the only psychical power which is to be assumed. Thus ways of doing things were selected, which were expedient. They answered the purpose better than other ways, or with less toil and pain. Along the course on which efforts were compelled to go, habit, routine, and skill were developed. The struggle to maintain existence was carried on, not individually, but in groups. Each profited by the other's experience; hence there was concurrence towards that which proved to be most expedient. All at last adopted the same way for the same purpose; hence the ways turned into customs and became mass phenomena. Instincts were developed in connection with them. In this way folkways arise. The young learn them by tradition, imitation, and authority. The folkways, at a time, provide for all the needs of life then and there. They are uniform, universal in the group, imperative, and invariable. As time goes on, the3 folkways become more and more arbitrary, positive, and imperative. If asked why they act in a certain way in certain cases, primitive people always answer that it is because they and their ancestors always have done so. A sanction also arises from ghost fear. The ghosts of ancestors would be angry if the living should change the ancient folkways (see sec. 6).

2. The folkways are a societal force. The operation by which folkways are produced consists in the frequent repetition of petty acts, often by great numbers acting in concert or, at least, acting in the same way when face to face with the same need. The immediate motive is interest. It produces habit in the individual and custom in the group. It is, therefore, in the highest degree original and primitive. By habit and custom it exerts a strain on every individual within its range; therefore it rises to a societal force to which great classes of societal phenomena are due. Its earliest stages, its course, and laws may be studied; also its influence on individuals and their reaction on it. It is our present purpose so to study it. We have to recognize it as one of the chief forces by which a society is made to be what it is. Out of the unconscious experiment which every repetition of the ways includes, there issues pleasure or pain, and then, so far as the men are capable of reflection, convictions that the ways are conducive to societal welfare. These two experiences are not the same. The most uncivilized men, both in the food quest and in war, do things which are painful, but which have been found to be expedient. Perhaps these cases teach the sense of social welfare better than those which are pleasurable and favorable to welfare. The former cases call for some intelligent reflection on experience. When this conviction as to the relation to welfare is added to the folkways they are converted into mores, and, by virtue of the philosophical and ethical element added to them, they win utility and importance and become the source of the science and the art of living.

3. Folkways are made unconsciously. It is of the first importance to notice that, from the first acts by which men try to satisfy needs, each act stands by itself, and looks no further than the immediate satisfaction. From recurrent needs arise habits for4 the individual and customs for the group, but these results are consequences which were never conscious, and never foreseen or intended. They are not noticed until they have long existed, and it is still longer before they are appreciated. Another long time must pass, and a higher stage of mental development must be reached, before they can be used as a basis from which to deduce rules for meeting, in the future, problems whose pressure can be foreseen. The folkways, therefore, are not creations of human purpose and wit. They are like products of natural forces which men unconsciously set in operation, or they are like the instinctive ways of animals, which are developed out of experience, which reach a final form of maximum adaptation to an interest, which are handed down by tradition and admit of no exception or variation, yet change to meet new conditions, still within the same limited methods, and without rational reflection or purpose. From this it results that all the life of human beings, in all ages and stages of culture, is primarily controlled by a vast mass of folkways handed down from the earliest existence of the race, having the nature of the ways of other animals, only the topmost layers of which are subject to change and control, and have been somewhat modified by human philosophy, ethics, and religion, or by other acts of intelligent reflection. We are told of savages that "It is difficult to exhaust the customs and small ceremonial usages of a savage people. Custom regulates the whole of a man's actions,—his bathing, washing, cutting his hair, eating, drinking, and fasting. From his cradle to his grave he is the slave of ancient usage. In his life there is nothing free, nothing original, nothing spontaneous, no progress towards a higher and better life, and no attempt to improve his condition, mentally, morally, or spiritually."1 All men act in this way with only a little wider margin of voluntary variation.

4. Impulse and instinct. Primeval stupidity. Magic. "The mores (Sitten) rest on feelings of pleasure or pain, which either directly produce actions or call out desires which become causes of action."2 "Impulse is not an attribute of living creatures, 5like instinct. The only phenomenon to which impulse applies is that men and other animals imitate what they see others, especially of their own species, do, and that they accomplish this imitation the more easily, the more their forefathers practiced the same act. The thing imitated, therefore, must already exist, and cannot be explained as an impulse." "As soon as instinct ceased to be sole ruler of living creatures, including inchoate man, the latter must have made mistakes in the struggle for existence which would soon have finished his career, but that he had instinct and the imitation of what existed to guide him. This human primeval stupidity is the ultimate ground of religion and art, for both come without any interval, out of the magic which is the immediate consequence of the struggle for existence when it goes beyond instinct." "If we want to determine the origin of dress, if we want to define social relations and achievements, e.g. the origin of marriage, war, agriculture, cattle breeding, etc., if we want to make studies in the psyche of nature peoples,—we must always pass through magic and belief in magic. One who is weak in magic, e.g. a ritually unclean man, has a 'bad body,' and reaches no success. Primitive men, on the other hand, win their success by means of their magical power and their magical preparations, and hence become 'the noble and good.' For them there is no other morality [than this success]. Even the technical dexterities have certainly not been free from the influence of belief in magic."3

5. The strain of improvement and consistency. The folkways, being ways of satisfying needs, have succeeded more or less well, and therefore have produced more or less pleasure or pain. Their quality always consisted in their adaptation to the purpose. If they were imperfectly adapted and unsuccessful, they produced pain, which drove men on to learn better. The folkways are, therefore, (1) subject to a strain of improvement towards better adaptation of means to ends, as long as the adaptation is so imperfect that pain is produced. They are also (2) subject to a strain of consistency with each other, because they all answer their several purposes with less friction and antagonism when 6they coöperate and support each other. The forms of industry, the forms of the family, the notions of property, the constructions of rights, and the types of religion show the strain of consistency with each other through the whole history of civilization. The two great cultural divisions of the human race are the oriental and the occidental. Each is consistent throughout; each has its own philosophy and spirit; they are separated from top to bottom by different mores, different standpoints, different ways, and different notions of what societal arrangements are advantageous. In their contrast they keep before our minds the possible range of divergence in the solution of the great problems of human life, and in the views of earthly existence by which life policy may be controlled. If two planets were joined in one, their inhabitants could not differ more widely as to what things are best worth seeking, or what ways are most expedient for well living.

6. The aleatory interest. If we should try to find a specimen society in which expedient ways of satisfying needs and interests were found by trial and failure, and by long selection from experience, as broadly described in sec. 1 above, it might be impossible to find one. Such a practical and utilitarian mode of procedure, even when mixed with ghost sanction, is rationalistic. It would not be suited to the ways and temper of primitive men. There was an element in the most elementary experience which was irrational and defied all expedient methods. One might use the best known means with the greatest care, yet fail of the result. On the other hand, one might get a great result with no effort at all. One might also incur a calamity without any fault of his own. This was the aleatory element in life, the element of risk and loss, good or bad fortune. This element is never absent from the affairs of men. It has greatly influenced their life philosophy and policy. On one side, good luck may mean something for nothing, the extreme case of prosperity and felicity. On the other side, ill luck may mean failure, loss, calamity, and disappointment, in spite of the most earnest and well-planned endeavor. The minds of men always dwell more on bad luck. They accept ordinary prosperity as a matter of course. Misfortunes arrest their attention and remain in their memory.

7Hence the ills of life are the mode of manifestation of the aleatory element which has most affected life policy. Primitive men ascribed all incidents to the agency of men or of ghosts and spirits. Good and ill luck were attributed to the superior powers, and were supposed to be due to their pleasure or displeasure at the conduct of men. This group of notions constitutes goblinism. It furnishes a complete world philosophy. The element of luck is always present in the struggle for existence. That is why primitive men never could carry on the struggle for existence, disregarding the aleatory element and employing a utilitarian method only. The aleatory element has always been the connecting link between the struggle for existence and religion. It was only by religious rites that the aleatory element in the struggle for existence could be controlled. The notions of ghosts, demons, another world, etc., were all fantastic. They lacked all connection with facts, and were arbitrary constructions put upon experience. They were poetic and developed by poetic construction and imaginative deduction. The nexus between them and events was not cause and effect, but magic. They therefore led to delusive deductions in regard to life and its meaning, which entered into subsequent action as guiding faiths, and imperative notions about the conditions of success. The authority of religion and that of custom coalesced into one indivisible obligation. Therefore the simple statement of experiment and expediency in the first paragraph above is not derived directly from actual cases, but is a product of analysis and inference. It must also be added that vanity and ghost fear produced needs which man was as eager to satisfy as those of hunger or the family. Folkways resulted for the former as well as for the latter (see sec. 9).

7. All origins are lost in mystery. No objection can lie against this postulate about the way in which folkways began, on account of the element of inference in it. All origins are lost in mystery, and it seems vain to hope that from any origin the veil of mystery will ever be raised. We go up the stream of history to the utmost point for which we have evidence of its course. Then we are forced to reach out into the darkness upon8 the line of direction marked by the remotest course of the historic stream. This is the way in which we have to act in regard to the origin of capital, language, the family, the state, religion, and rights. We never can hope to see the beginning of any one of these things. Use and wont are products and results. They had antecedents. We never can find or see the first member of the series. It is only by analysis and inference that we can form any conception of the "beginning" which we are always so eager to find.

8. Spencer on primitive custom. Spencer4 says that "guidance by custom, which we everywhere find amongst rude peoples, is the sole conceivable guidance at the outset." Custom is the product of concurrent action through time. We find it existent and in control at the extreme reach of our investigations. Whence does it begin, and how does it come to be? How can it give guidance "at the outset"? All mass actions seem to begin because the mass wants to act together. The less they know what it is right and best to do, the more open they are to suggestion from an incident in nature, or from a chance act of one, or from the current doctrines of ghost fear. A concurrent drift begins which is subject to later correction. That being so, it is evident that instinctive action, under the guidance of traditional folkways, is an operation of the first importance in all societal matters. Since the custom never can be antecedent to all action, what we should desire most is to see it arise out of the first actions, but, inasmuch as that is impossible, the course of the action after it is started is our field of study. The origin of primitive customs is always lost in mystery, because when the action begins the men are never conscious of historical action, or of the historical importance of what they are doing. When they become conscious of the historical importance of their acts, the origin is already far behind.

9. Good and bad luck; ills of life; goodness and happiness. There are in nature numerous antagonistic forces of growth or production and destruction. The interests of man are between the two and may be favored or ruined by either. Correct knowledge of both is required to get the advantages 9and escape the injuries. Until the knowledge becomes adequate the effects which are encountered appear to be accidents or cases of luck. There is no thrift in nature. There is rather waste. Human interests require thrift, selection, and preservation. Capital is the condition precedent of all gain in security and power, and capital is produced by selection and thrift. It is threatened by all which destroys material goods. Capital is therefore the essential means of man's power over nature, and it implies the purest concept of the power of intelligence to select and dispose of the processes of nature for human welfare. All the earliest efforts in this direction were blundering failures. Men selected things to be desired and preserved under impulses of vanity and superstition, and misconceived utility and interest. The errors entered into the folkways, formed a part of them, and were protected by them. Error, accident, and luck seem to be the only sense there is in primitive life. Knowledge alone limits their sway, and at least changes the range and form of their dominion. Primitive folkways are marked by improvidence, waste, and carelessness, out of which prudence, foresight, patience, and perseverance are developed slowly, by pain and loss, as experience is accumulated, and knowledge increases also, as better methods seem worth while. The consequences of error and the effects of luck were always mixed. As we have seen, the ills of life were connected with the displeasure of the ghosts. Per contra, conduct which conformed to the will of the ghosts was goodness, and was supposed to bring blessing and prosperity. Thus a correlation was established, in the faith of men, between goodness and happiness, and on that correlation an art of happiness was built. It consisted in a faithful performance of rites of respect towards superior powers and in the use of lucky times, places, words, etc., with avoidance of unlucky ones. All uncivilized men demand and expect a specific response. Inasmuch as they did not get it, and indeed the art of happiness always failed of results, the great question of world philosophy always has been, What is the real relation between happiness and goodness? It is only within a few generations that men have found courage to say that there is none. The whole strength of the notion that they are correlated is in the opposite experience which proves that no evil thing brings happiness. The oldest religious literature consists of formulas of worship and prayer by which devotion and obedience were to produce satisfaction of the gods, and win favor and prosperity for men.5 The words "ill" and "evil" have never yet thrown off the ambiguity between wickedness and calamity. The two ideas come down to us allied or combined. It was the rites which were the object of tradition, not the ideas which they embodied.6

10. Illustrations. The notions of blessing and curse are subsequent explanations by men of great cases of prosperity or calamity which came to 10their knowledge. Then the myth-building imagination invented stories of great virtue or guilt to account for the prosperity or calamity.7 The Greek notion of the Nemesis was an inference from observation of good and ill fortune in life. Great popular interest attached to the stories of Crœsus and Polycrates. The latter, after all his glory and prosperity, was crucified by the satrap of Lydia. Crœsus had done all that man could do, according to the current religion, to conciliate the gods and escape ill fortune. He was very pious and lived by the rules of religion. The story is told in different forms. "The people could not make up their minds that a prince who had been so liberal to the gods during his prosperity had been abandoned by them at the moment when he had the greatest need of their aid."8 They said that he expiated the crime of his ancestor Gyges, who usurped the throne; that is, they found it necessary to adduce some guilt to account for the facts, and they introduced the notion of hereditary responsibility. Another story was that he determined to sacrifice all his wealth to the gods. He built a funeral pyre of it all and mounted it himself, but rain extinguished it. The gods were satisfied. Crœsus afterwards enjoyed the friendship of Cyros, which was good fortune. Still others rejected the doctrines of correlation between goodness and happiness on account of the fate of Crœsus. In ancient religion "the benefits which were expected from the gods were of a public character, affecting the whole community, especially fruitful seasons, increase of flocks and herds, and success in war. So long as the community flourished, the fact that an individual was miserable reflected no discredit on divine providence, but was rather taken to prove that the sufferer was an evil-doer, justly hateful to the gods."9 Jehu and his house were blamed for the blood spilt at Israel, although Jehu was commissioned by Elisha to destroy the house of Ahab.10 This is like the case of Œdipus, who obeyed an oracle, but suffered for his act as for a crime. Jehovah caused the ruin of those who had displeased him, by putting false oracles in the mouths of prophets.11 Hezekiah expostulated with God because, although he had walked before God with a perfect heart and had done what was right in His sight, he suffered calamity.12 In the seventy-third Psalm, the author is perplexed by the prosperity of the wicked, and the contrast of his own fortunes. "Surely in vain have I cleansed my heart and washed my hands in innocency, for all day long have I been plagued, and chastened every morning." He says that at last the wicked were cast down. He was brutish and ignorant not to see the solution. It is that the wicked prosper for a time only. He will cleave unto God. The book of Job is a discussion of the relation between goodness and happiness. The crusaders 11were greatly perplexed by the victories of the Mohammedans. It seemed to be proved untrue that God would defend His own Name or the true and holy cause. Louis XIV, when his armies were defeated, said that God must have forgotten all which he had done for Him.

11. Immortality and compensation. The notion of immortality has been interwoven with the notion of luck, of justice, and of the relation of goodness and happiness. The case was reopened in another world, and compensations could be assumed to take place there. In the folk drama of the ancient Greeks luck ruled. It was either envious of human prosperity or beneficent.13 Grimm14 gives more than a thousand ancient German apothegms, dicta, and proverbs about "luck." The Italians of the fifteenth century saw grand problems in the correlation of goodness and happiness. Alexander VI was the wickedest man known in history, but he had great and unbroken prosperity in all his undertakings. The only conceivable explanation was that he had made a pact with the devil. Some of the American Indians believed that there was an hour at which all wishes uttered by men were fulfilled.15 It is amongst half-civilized peoples that the notion of luck is given the greatest influence in human affairs. They seek devices for operating on luck, since luck controls all interests. Hence words, times, names, places, gestures, and other acts or relations are held to control luck. Inasmuch as marriage is a relationship in which happiness is sought and not always found, wedding ceremonies are connected with acts "for luck." Some of these still survive amongst us as jests. The fact of the aleatory element in human life, the human interpretations of it, and the efforts of men to deal with it constitute a large part of the history of culture. They have produced groups of folkways, and have entered as an element into folkways for other purposes.

12. Tradition and its restraints. It is evident that the "ways" of the older and more experienced members of a society deserve great authority in any primitive group. We find that this rational authority leads to customs of deference and to etiquette in favor of the old. The old in turn cling stubbornly to tradition and to the example of their own predecessors. Thus tradition and custom become intertwined and are a strong coercion which directs the society upon fixed lines, and strangles liberty. Children see their parents always yield to the same custom and obey the same persons. They see that the elders are allowed to do all the talking, and that if an outsider enters, he is saluted by those who are at home according to rank and in fixed order. 12All this becomes rule for children, and helps to give to all primitive customs their stereotyped formality. "The fixed ways of looking at things which are inculcated by education and tribal discipline, are the precipitate of an old cultural development, and in their continued operation they are the moral anchor of the Indian, although they are also the fetters which restrain his individual will."16

13. The concept of "primitive society"; we-group and others-group. The conception of "primitive society" which we ought to form is that of small groups scattered over a territory. The size of the groups is determined by the conditions of the struggle for existence. The internal organization of each group corresponds to its size. A group of groups may have some relation to each other (kin, neighborhood, alliance, connubium and commercium) which draws them together and differentiates them from others. Thus a differentiation arises between ourselves, the we-group, or in-group, and everybody else, or the others-groups, out-groups. The insiders in a we-group are in a relation of peace, order, law, government, and industry, to each other. Their relation to all outsiders, or others-groups, is one of war and plunder, except so far as agreements have modified it. If a group is exogamic, the women in it were born abroad somewhere. Other foreigners who might be found in it are adopted persons, guest friends, and slaves.

14. Sentiments in the in-group and towards the out-group. The relation of comradeship and peace in the we-group and that of hostility and war towards others-groups are correlative to each other. The exigencies of war with outsiders are what make peace inside, lest internal discord should weaken the we-group for war. These exigencies also make government and law in the in-group, in order to prevent quarrels and enforce discipline. Thus war and peace have reacted on each other and developed each other, one within the group, the other in the intergroup relation. The closer the neighbors, and the stronger they are, the intenser is the warfare, and then the intenser is the internal organization and discipline of each. Sentiments are produced to 13correspond. Loyalty to the group, sacrifice for it, hatred and contempt for outsiders, brotherhood within, warlikeness without,—all grow together, common products of the same situation. These relations and sentiments constitute a social philosophy. It is sanctified by connection with religion. Men of an others-group are outsiders with whose ancestors the ancestors of the we-group waged war. The ghosts of the latter will see with pleasure their descendants keep up the fight, and will help them. Virtue consists in killing, plundering, and enslaving outsiders.

15. Ethnocentrism is the technical name for this view of things in which one's own group is the center of everything, and all others are scaled and rated with reference to it. Folkways correspond to it to cover both the inner and the outer relation. Each group nourishes its own pride and vanity, boasts itself superior, exalts its own divinities, and looks with contempt on outsiders. Each group thinks its own folkways the only right ones, and if it observes that other groups have other folkways, these excite its scorn. Opprobrious epithets are derived from these differences. "Pig-eater," "cow-eater," "uncircumcised," "jabberers," are epithets of contempt and abomination. The Tupis called the Portuguese by a derisive epithet descriptive of birds which have feathers around their feet, on account of trousers.17 For our present purpose the most important fact is that ethnocentrism leads a people to exaggerate and intensify everything in their own folkways which is peculiar and which differentiates them from others. It therefore strengthens the folkways.

16. Illustrations of ethnocentrism. The Papuans on New Guinea are broken up into village units which are kept separate by hostility, cannibalism, head hunting, and divergences of language and religion. Each village is integrated by its own language, religion, and interests. A group of villages is sometimes united into a limited unity by connubium. A wife taken inside of this group unit has full status; one taken outside of it has not. The petty group units are peace groups within and are hostile to all outsiders.18 The Mbayas of South America believed that their deity had bidden them live by making war on others, taking their wives and property, and killing their men.19

1417. When Caribs were asked whence they came, they answered, "We alone are people."20 The meaning of the name Kiowa is "real or principal people."21 The Lapps call themselves "men," or "human beings."22 The Greenland Eskimo think that Europeans have been sent to Greenland to learn virtue and good manners from the Greenlanders. Their highest form of praise for a European is that he is, or soon will be, as good as a Greenlander.23 The Tunguses call themselves "men."24 As a rule it is found that nature peoples call themselves "men." Others are something else—perhaps not defined—but not real men. In myths the origin of their own tribe is that of the real human race. They do not account for the others. The Ainos derive their name from that of the first man, whom they worship as a god. Evidently the name of the god is derived from the tribe name.25 When the tribal name has another sense, it is always boastful or proud. The Ovambo name is a corruption of the name of the tribe for themselves, which means "the wealthy."26 Amongst the most remarkable people in the world for ethnocentrism are the Seri of Lower California. They observe an attitude of suspicion and hostility to all outsiders, and strictly forbid marriage with outsiders.27

18. The Jews divided all mankind into themselves and Gentiles. They were the "chosen people." The Greeks and Romans called all outsiders "barbarians." In Euripides' tragedy of Iphigenia in Aulis Iphigenia says that it is fitting that Greeks should rule over barbarians, but not contrariwise, because Greeks are free, and barbarians are slaves. The Arabs regarded themselves as the noblest nation and all others as more or less barbarous.28 In 1896, the Chinese minister of education and his counselors edited a manual in which this statement occurs: "How grand and glorious is the Empire of China, the middle kingdom! She is the largest and richest in the world. The grandest men in the world have all come from the middle empire."29 In all the literature of all the states equivalent statements occur, although they are not so naïvely expressed. In Russian books and newspapers the civilizing mission of Russia is talked about, just as, in the books and journals of France, Germany, and the United States, the civilizing mission of those countries is assumed and referred to as well understood. Each state now regards itself as the leader of civilization, the best, the freest, and the wisest, and all others as inferior. Within a few years our own man-on-the-curbstone has learned to class all foreigners of the Latin 15peoples as "dagos," and "dago" has become an epithet of contempt. These are all cases of ethnocentrism.

19. Patriotism is a sentiment which belongs to modern states. It stands in antithesis to the mediæval notion of catholicity. Patriotism is loyalty to the civic group to which one belongs by birth or other group bond. It is a sentiment of fellowship and coöperation in all the hopes, work, and suffering of the group. Mediæval catholicity would have made all Christians an in-group and would have set them in hostility to all Mohammedans and other non-Christians. It never could be realized. When the great modern states took form and assumed control of societal interests, group sentiment was produced in connection with those states. Men responded willingly to a demand for support and help from an institution which could and did serve interests. The state drew to itself the loyalty which had been given to men (lords), and it became the object of that group vanity and antagonism which had been ethnocentric. For the modern man patriotism has become one of the first of duties and one of the noblest of sentiments. It is what he owes to the state for what the state does for him, and the state is, for the modern man, a cluster of civic institutions from which he draws security and conditions of welfare. The masses are always patriotic. For them the old ethnocentric jealousy, vanity, truculency, and ambition are the strongest elements in patriotism. Such sentiments are easily awakened in a crowd. They are sure to be popular. Wider knowledge always proves that they are not based on facts. That we are good and others are bad is never true. By history, literature, travel, and science men are made cosmopolitan. The selected classes of all states become associated; they intermarry. The differentiation by states loses importance. All states give the same security and conditions of welfare to all. The standards of civic institutions are the same, or tend to become such, and it is a matter of pride in each state to offer civic status and opportunities equal to the best. Every group of any kind whatsoever demands that each of its members shall help defend group interests. Every group stigmatizes any one who fails in zeal, labor, and sacrifices for group interests. Thus the sentiment of loyalty to the group, or the group head, which was so strong in the Middle Ages, is kept up, as far as possible, in regard to modern states and governments. The group force is also employed to enforce the obligations of devotion to group interests. It follows that judgments are precluded and criticism is silenced.

20. Chauvinism. That patriotism may degenerate into a vice is shown by the invention of a name for the vice: chauvinism. It is a name for boastful and truculent group self-assertion. It overrules personal judgment and character, and puts the whole group at the mercy of the clique which is ruling at the moment. It produces the dominance of watchwords and phrases which take the place of reason and conscience in determining conduct. The patriotic bias is a recognized perversion of thought and judgment against which our education should guard us.

1621. The struggle for existence and the competition of life; antagonistic coöperation. The struggle for existence must be carried on under life conditions and in connection with the competition of life. The life conditions consist in variable elements of the environment, the supply of materials necessary to support life, the difficulty of exploiting them, the state of the arts, and the circumstances of physiography, climate, meteorology, etc., which favor life or the contrary. The struggle for existence is a process in which an individual and nature are the parties. The individual is engaged in a process by which he wins from his environment what he needs to support his existence. In the competition of life the parties are men and other organisms. The men strive with each other, or with the flora and fauna with which they are associated. The competition of life is the rivalry, antagonism, and mutual displacement in which the individual is involved with other organisms by his efforts to carry on the struggle for existence for himself. It is, therefore, the competition of life which is the societal element, and which produces societal organization. The number present and in competition is another of the life conditions. At a time and place the life conditions are the same for a number of human beings who are present, and the problems of life policy are the same. This is another reason why the attempts to satisfy interest become mass phenomena and result in folkways. The individual and social elements are always in interplay with each other if there are a number present. If one is trying to carry on the struggle for existence with nature, the fact that others are doing the same in the same environment is an essential condition for him. Then arises an alternative. He and the others may so interfere with each other that all shall fail, or they may combine, and by coöperation raise their efforts against nature to a higher power. This latter method is industrial organization. The crisis which produces it is constantly renewed, and men are forced to raise the organization to greater complexity and more comprehensive power, without limit. Interests are the relations of action and reaction between the individual and the life conditions, through which relations the evolution of the individual is produced. That17 evolution, so long as it goes on prosperously, is well living, and it results in the self-realization of the individual, for we may think of each one as capable of fulfilling some career and attaining to some character and state of power by the developing of predispositions which he possesses. It would be an error, however, to suppose that all nature is a chaos of warfare and competition. Combination and coöperation are so fundamentally necessary that even very low life forms are found in symbiosis for mutual dependence and assistance. A combination can exist where each of its members would perish. Competition and combination are two forms of life association which alternate through the whole organic and superorganic domains. The neglect of this fact leads to many socialistic fallacies. Combination is of the essence of organization, and organization is the great device for increased power by a number of unequal and dissimilar units brought into association for a common purpose. McGee30 says of the desert of Papagueria, in southwestern Arizona, that "a large part of the plants and animals of the desert dwell together in harmony and mutual helpfulness [which he shows in detail]; for their energies are directed not so much against one another as against the rigorous environmental conditions growing out of dearth of water. This communality does not involve loss of individuality, ... indeed the plants and animals are characterized by an individuality greater than that displayed in regions in which perpetuity of the species depends less closely on the persistence of individuals." Hence he speaks of the "solidarity of life" in the desert. "The saguaro is a monstrosity in fact as well as in appearance,—a product of miscegenation between plant and animal, probably depending for its form of life history, if not for its very existence, on its commensals."31 The Seri protect pelicans from themselves by a partial taboo, which is not understood. It seems that they could not respect a breeding time, or establish a closed season, yet they have such an appetite for the birds and their eggs that they would speedily exterminate them if there were no restraint. This combination has been well called antagonistic coöperation. 18It consists in the combination of two persons or groups to satisfy a great common interest while minor antagonisms of interest which exist between them are suppressed. The plants and animals of the desert are rivals for what water there is, but they combine as if with an intelligent purpose to attain to a maximum of life under the conditions. There are many cases of animals who coöperate in the same way. Our farmers put crows and robins under a protective taboo because the birds destroy insects. The birds also destroy grain and fruits, but this is tolerated on account of their services. Madame Pommerol says of the inhabitants of Sahara that the people of the towns and the nomads are enemies by caste and race, but allies in interest. The nomads need refuge and shelter. The townspeople need messengers and transportation. Hence ties of contract, quarrels, fights, raids, vengeances, and reconciliations for the sake of common enterprises of plunder.32 Antagonistic coöperation is the most productive form of combination in high civilization. It is a high action of the reason to overlook lesser antagonisms in order to work together for great interests. Political parties are constantly forced to do it. In the art of the statesman it is a constant policy. The difference between great parties and factions in any parliamentary system is of the first importance; that difference consists in the fact that parties can suppress minor differences, and combine for what they think most essential to public welfare, while factions divide and subdivide on petty differences. Inasmuch as the suppression of minor differences means a suppression of the emotional element, while the other policy encourages the narrow issues in regard to which feeling is always most intense, the former policy allows far less play to feeling and passion.

22. Hunger, love, vanity, and fear. There are four great motives of human action which come into play when some number of human beings are in juxtaposition under the same life conditions. These are hunger, sex passion, vanity, and fear (of ghosts and spirits). Under each of these motives there are interests. Life consists in satisfying interests, for "life," in a society, is a career of action and effort expended on both the 19material and social environment. However great the errors and misconceptions may be which are included in the efforts, the purpose always is advantage and expediency. The efforts fall into parallel lines, because the conditions and the interests are the same. It is now the accepted opinion, and it may be correct, that men inherited from their beast ancestors psychophysical traits, instincts, and dexterities, or at least predispositions, which give them aid in solving the problems of food supply, sex, commerce, and vanity. The result is mass phenomena; currents of similarity, concurrence, and mutual contribution; and these produce folkways. The folkways are unconscious, spontaneous, uncoördinated. It is never known who led in devising them, although we must believe that talent exerted its leadership at all times. Folkways come into existence now all the time. There were folkways in stage coach times, which were fitted to that mode of travel. Street cars have produced ways which are suited to that mode of transportation in cities. The telephone has produced ways which have not been invented and imposed by anybody, but which are devised to satisfy conveniently the interests which are at stake in the use of that instrument.

23. Process of making folkways. Although we may see the process of making folkways going on all the time, the analysis of the process is very difficult. It appears as if there was a "mind" in the crowd which was different from the minds of the individuals which compose it. Indeed some have adopted such a doctrine. By autosuggestion the stronger minds produce ideas which when set afloat pass by suggestion from mind to mind. Acts which are consonant with the ideas are imitated. There is a give and take between man and man. This process is one of development. New suggestions come in at point after point. They are carried out. They combine with what existed already. Every new step increases the number of points upon which other minds may seize. It seems to be by this process that great inventions are produced. Knowledge has been won and extended by it. It seems as if the crowd had a mystic power in it greater than the sum of the powers of its members. It is sufficient, however, to explain this, to notice that there is a coöperation and constant20 suggestion which is highly productive when it operates in a crowd, because it draws out latent power, concentrates what would otherwise be scattered, verifies and corrects what has been taken up, eliminates error, and constructs by combination. Hence the gain from the collective operation is fully accounted for, and the theories of Völkerpsychologie are to be rejected as superfluous. Out of the process which has been described have come the folkways during the whole history of civilization.

The phenomena of suggestion and suggestibility demand some attention because the members of a group are continually affecting each other by them, and great mass phenomena very often are to be explained by them.

24. Suggestion; suggestibility. What has been called the psychology of crowds consists of certain phenomena of suggestion. A number of persons assembled together, especially if they are enthused by the same sentiment or stimulated by the same interest, transmit impulses to each other with the result that all the impulses are increased in a very high ratio. In other words, it is an undisputed fact that all mental states and emotions are greatly increased in force by transmission from man to man, especially if they are attended by a sense of the concurrence and coöperation of a great number who have a common sentiment or interest. "The element of psychic coercion to which our thought process is subject is the characteristic of the operations which we call suggestive."33 What we have done or heard occupies our minds so that we cannot turn from it to something else. The consensus of a number promises triumph for the impulse, whatever it is. Ça ira. There is a thrill of enthusiasm in the sense of moving with a great number. There is no deliberation or reason. Therefore a crowd may do things which are either better or worse than what individuals in it would do. Cases of lynching show how a crowd can do things which it is extremely improbable that the individuals would do or consent to, if they were taken separately. The crowd has no greater guarantee of wisdom and virtue than an individual would have. In fact, the participants in a crowd almost always throw away 21all the powers of wise judgment which have been acquired by education, and submit to the control of enthusiasm, passion, animal impulse, or brute appetite. A crowd always has a common stock of elementary faiths, prejudices, loves and hates, and pet notions. The common stock is acted on by the same stimuli, in all the persons, at the same time. The response, as an aggregate, is a great storm of feeling, and a great impulse to the will. Hence the great influence of omens and of all popular superstitions on a crowd. Omens are a case of "egoistic reference."34 An army desists from a battle on account of an eclipse. A man starting out on the food quest returns home because a lizard crosses his path. In each case an incident in nature is interpreted as a warning or direction to the army or the man. Thus momentous results for men and nations may be produced without cause. The power of watchwords consists in the cluster of suggestions which has become fastened upon them. In the Middle Ages the word "heretic" won a frightful suggestion of base wickedness. In the seventeenth century the same suggestions were connected with the words "witch" and "traitor." "Nature" acquired great suggestion of purity and correctness in the eighteenth century, which it has not yet lost. "Progress" now bears amongst us a very undue weight of suggestion. Suggestibility is the quality of liability to suggestive influence.35 "Suggestibility is the natural faculty of the brain to admit any ideas whatsoever, without motive, to assimilate them, and eventually to transform them rapidly into movements, sensations, and inhibitions."36 It differs greatly in degree, and is present in different grades in different crowds. Crowds of different nationalities would differ both in degree of suggestibility and in the kinds of suggestive stimuli to which they would respond. Imitation is due to suggestibility. Even suicide is rendered epidemic by suggestion and imitation.37 In a crisis, like a shipwreck, when no one knows what to do, one, by acting, may lead them all 22through imitative suggestibility. People who are very suggestible can be led into states of mind which preclude criticism or reflection. Any one who acquires skill in the primary processes of association, analogy, reiteration, and continuity, can play tricks on others by stimulating these processes and then giving them selected data to work upon. A directive idea may be suggested by a series of ideas which lead the recipient of them to expect that the series will be continued. Then he will not perceive if the series is broken. In the Renaissance period no degree of illumination sufficed to resist the delusion of astrology, because it was supported by a passionate fantasy and a vehement desire to know the future, and because it was confirmed by antiquity, the authority of whose opinions was overwhelmingly suggested by all the faiths and prejudices of the time.38

25. Suggestion in education. Manias. Parents and teachers use suggestion in rearing children. Persons who enjoy social preëminence operate suggestion all the time, whether intentionally or unintentionally. Whatever they do is imitated. Folkways operate on individuals by suggestion; when they are elevated to mores they do so still more, for then they carry the suggestion of societal welfare. Ways and notions may be rejected by an individual at first upon his judgment of their merits, but repeated suggestion produces familiarity and dulls the effect upon him of the features which at first repelled him. Familiar cases of this are furnished by fashions of dress and by slang. A new fashion of dress seems at first to be absurd, ungraceful, or indecent. After a time this first impression of it is so dulled that all conform to the fashion. New slang seems vulgar. It makes its way into use. In India the lingam symbol is so common that no one pays any heed to its sense.39 This power of familiarity to reduce the suggestion to zero furnishes a negative proof of the power of the suggestion. Conventionalization also reduces suggestion, perhaps to zero. It is a mischievous thing to read descriptions of crime, vice, horrors, excessive adventures, etc., because familiarity lessens the abhorrent suggestions which those things ought to produce. Swindlers and all others who have an interest to lead the minds of their fellow-men in a certain direction employ suggestion. They often develop great practical skill in the operation, although they do not understand the science of it. It is one of the arts of the demagogue and stump orator. A man who wanted to be nominated for an office went before the convention to make a speech. A great and difficult question agitated the party. He began by saying that he would state his position 23on that question frankly and fully. "But first," said he, "let me say that I am a Democrat." This brought out a storm of applause. Then he went on to boast of his services to the party, and then he stopped without having said a word on the great question. He was easily nominated. The witch persecutions rested on suggestion. "Everybody knew" that there were witches. If not, what were the people who were burned? Philip IV of France wanted to make the people believe that the templars were heretics. The people were not ready to believe this. The king caused the corpse of a templar to be dug up and burned, as the corpses of heretics were burned. This convinced the people by suggestion.40 What "they say," what "everybody does," and what "everybody knows" are controlling suggestions. Religious revivals are carried on by suggestion. Mediæval flagellations and dances were cases of suggestion. In fact, all popular manias are to be explained by it. Religious bodies practice suggestion on themselves, especially on their children or less enthusiastic members, by symbols, pictures, images, processions, dramatic representations, festivals, relics, legends of their heroes. In the Middle Ages the crucifix was an instrument of religious suggestion to produce vivid apprehension of the death of Jesus. In very many well-known cases the passions of the crowd were raised to the point of very violent action. The symbols and images also, by suggestion, stimulate religious fervor. If numbers act together, as in convents, mass phenomena are produced, and such results follow as the hysterical epidemics in convents and the extravagances of communistic sects.41 Learned societies and numbers of persons who are interested in the same subject, by meeting and imparting suggestions, make all the ideas of each the common stock of all. Hyperboreans have a mental disease which renders them liable to suggestion. The women are afflicted by hysteria before puberty. Later they show the phenomena of "possession,"—dancing and singing,—and still later catalepsy.42

26. Suggestion in politics. The great field for the use of the devices and apparatus of suggestion at the present time is politics. Within fifty years all states have become largely popular. Suggestion is easy when it falls in with popular ideas, the pet notions of groups of people, the popular common-places, and the current habits of thought and feeling. Newspapers, popular literature, and popular oratory show the effort to operate suggestion along these lines. They rarely correct; they usually flatter the accepted notions. The art of adroit suggestion is one of the great arts of politics. Antony's speech over the body of Cæsar is a classical example of it. In politics, especially at elections, the old apparatus of suggestion is employed again,—flags, symbols, ceremonies, and celebrations. Patriotism is systematically cultivated by anniversaries, pilgrimages, symbols, songs, recitations, etc. 24Another very remarkable case of suggestion is furnished by modern advertisements. They are adroitly planned to touch the mind of the reader in a way to get the reaction which the advertiser wants. The advertising pages of our popular magazines furnish evidence of the faiths and ideas which prevail in the masses.

27. Suggestion and criticism. Suggestion is a legitimate device, if it is honestly used, for inculcating knowledge or principles of conduct; that is, for education in the broadest sense of the word. Criticism is the operation by which suggestion is limited and corrected. It is by criticism that the person is protected against credulity, emotion, and fallacy. The power of criticism is the one which education should chiefly train. It is difficult to resist the suggestion that one who is accused of crime is guilty. Lynchers generally succumb to this suggestion, especially if the crime was a heinous one which has strongly excited their emotions against the unknown somebody who perpetrated it. It requires criticism to resist this suggestion. Our judicial institutions are devised to hold this suggestion aloof until the evidence is examined. An educated man ought to be beyond the reach of suggestions from advertisements, newspapers, speeches, and stories. If he is wise, just when a crowd is filled with enthusiasm and emotion, he will leave it and will go off by himself to form his judgment. In short, individuality and personality of character are the opposites of suggestibility. Autosuggestion properly includes all the cases in which a man is "struck by an idea," or "takes a notion," but it is more strictly applied to fixed ideas and habits of thought. An irritation suggests parasites, and parasites suggest an irritation. The fear of stammering causes stammering. A sleeping man drives away a fly without waking. If we are in a pose or rôle, we act as we have heard that people act in that pose or rôle.43 A highly trained judgment is required to correct or select one's own ideas and to resist fixed ideas. The supreme criticism is criticism of one's self.

28. Folkways due to false inference. Furthermore, folkways have been formed by accident, that is, by irrational and incongruous action, based on pseudo-knowledge. In Molembo a pestilence broke out soon after a Portuguese had died there. After that the natives took all possible measures not to allow any white man to die in their country.44 On the Nicobar islands some natives who had just begun to make pottery died. The art was given up and never again attempted.45 White men gave to one Bushman in a kraal a stick ornamented with buttons as a symbol of authority. The recipient died leaving the stick to 25his son. The son soon died. Then the Bushmen brought back the stick lest all should die.46 Until recently no building of incombustible materials could be built in any big town of the central province of Madagascar, on account of some ancient prejudice.47 A party of Eskimos met with no game. One of them returned to their sledges and got the ham of a dog to eat. As he returned with the ham bone in his hand he met and killed a seal. Ever afterwards he carried a ham bone in his hand when hunting.48 The Belenda women (peninsula of Malacca) stay as near to the house as possible during the period. Many keep the door closed. They know no reason for this custom. "It must be due to some now forgotten superstition."49 Soon after the Yakuts saw a camel for the first time smallpox broke out amongst them. They thought the camel to be the agent of the disease.50 A woman amongst the same people contracted an endogamous marriage. She soon afterwards became blind. This was thought to be on account of the violation of ancient customs.51 A very great number of such cases could be collected. In fact they represent the current mode of reasoning of nature people. It is their custom to reason that, if one thing follows another, it is due to it. A great number of customs are traceable to the notion of the evil eye, many more to ritual notions of uncleanness.52 No scientific investigation could discover the origin of the folkways mentioned, if the origin had not chanced to become known to civilized men. We must believe that the known cases illustrate the irrational and incongruous origin of many folkways. In civilized history also we know that customs have owed their origin to "historical accident,"—the vanity of a princess, the deformity of a king, the whim of a democracy, the love intrigue of a statesman or prelate. By the institutions of another age it may be provided that no one of these things can affect decisions, acts, or interests, but then the power to decide the ways may have passed to clubs, 26trades unions, trusts, commercial rivals, wire-pullers, politicians, and political fanatics. In these cases also the causes and origins may escape investigation.

29. Harmful folkways. There are folkways which are positively harmful. Very often these are just the ones for which a definite reason can be given. The destruction of a man's goods at his death is a direct deduction from other-worldliness; the dead man is supposed to want in the other world just what he wanted here. The destruction of a man's goods at his death was a great waste of capital, and it must have had a disastrous effect on the interests of the living, and must have very seriously hindered the development of civilization. With this custom we must class all the expenditure of labor and capital on graves, temples, pyramids, rites, sacrifices, and support of priests, so far as these were supposed to benefit the dead. The faith in goblinism produced other-worldly interests which overruled ordinary worldly interests. Foods have often been forbidden which were plentiful, the prohibition of which injuriously lessened the food supply. There is a tribe of Bushmen who will eat no goat's flesh, although goats are the most numerous domestic animals in the district.53 Where totemism exists it is regularly accompanied by a taboo on eating the totem animal. Whatever may be the real principle in totemism, it overrules the interest in an abundant food supply. "The origin of the sacred regard paid to the cow must be sought in the primitive nomadic life of the Indo-European race," because it is common to Iranians and Indians of Hindostan.54 The Libyans ate oxen but not cows.55 The same was true of the Phœnicians and Egyptians.56 In some cases the sense of a food taboo is not to be learned. It may have been entirely capricious. Mohammed would not eat lizards, because he thought them the offspring of a metamorphosed clan of Israelites.57 On the other hand, the protective taboo which forbade killing crocodiles, pythons, cobras, and other animals enemies of man was harmful 27to his interests, whatever the motive. "It seems to be a fixed article of belief throughout southern India, that all who have willfully or accidentally killed a snake, especially a cobra, will certainly be punished, either in this life or the next, in one of three ways: either by childlessness, or by leprosy, or by ophthalmia."58 Where this faith exists man has a greater interest to spare a cobra than to kill it. India furnishes a great number of cases of harmful mores. "In India every tendency of humanity seems intensified and exaggerated. No country in the world is so conservative in its traditions, yet no country has undergone so many religious changes and vicissitudes."59 "Every year thousands perish of disease that might recover if they would take proper nourishment, and drink the medicine that science prescribes, but which they imagine that their religion forbids them to touch." "Men who can scarcely count beyond twenty, and know not the letters of the alphabet, would rather die than eat food which had been prepared by men of lower caste, unless it had been sanctified by being offered to an idol; and would kill their daughters rather than endure the disgrace of having unmarried girls at home beyond twelve or thirteen years of age."60 In the last case the rule of obligation and duty is set by the mores. The interest comes under vanity. The sanction of the caste rules is in a boycott by all members of the caste. The rules are often very harmful. "The authority of caste rests partly on written laws, partly on legendary fables or narratives, partly on the injunctions of instructors and priests, partly on custom and usage, and partly on the caprice and convenience of its votaries."61 The harm of caste rules is so great that of late they have been broken in some cases, especially in regard to travel over sea, which is a great advantage to Hindoos.62 The Hindoo folkways in regard to widows and child marriages must also be recognized as socially harmful.

30. How "true" and "right" are found. If a savage puts his hand too near the fire, he suffers pain and draws it back. He 28knows nothing of the laws of the radiation of heat, but his instinctive action conforms to that law as if he did know it. If he wants to catch an animal for food, he must study its habits and prepare a device adjusted to those habits. If it fails, he must try again, until his observation is "true" and his device is "right." All the practical and direct element in the folkways seems to be due to common sense, natural reason, intuition, or some other original mental endowment. It seems rational (or rationalistic) and utilitarian. Often in the mythologies this ultimate rational element was ascribed to the teaching of a god or a culture hero. In modern mythology it is accounted for as "natural."

Although the ways adopted must always be really "true" and "right" in relation to facts, for otherwise they could not answer their purpose, such is not the primitive notion of true and right.

31. The folkways are "right." Rights. Morals. The folkways are the "right" ways to satisfy all interests, because they are traditional, and exist in fact. They extend over the whole of life. There is a right way to catch game, to win a wife, to make one's self appear, to cure disease, to honor ghosts, to treat comrades or strangers, to behave when a child is born, on the warpath, in council, and so on in all cases which can arise. The ways are defined on the negative side, that is, by taboos. The "right" way is the way which the ancestors used and which has been handed down. The tradition is its own warrant. It is not held subject to verification by experience. The notion of right is in the folkways. It is not outside of them, of independent origin, and brought to them to test them. In the folkways, whatever is, is right. This is because they are traditional, and therefore contain in themselves the authority of the ancestral ghosts. When we come to the folkways we are at the end of our analysis. The notion of right and ought is the same in regard to all the folkways, but the degree of it varies with the importance of the interest at stake. The obligation of conformable and coöperative action is far greater under ghost fear and war than in other matters, and the social sanctions are severer, because group interests are supposed to be at stake. Some usages contain only a slight element of right and ought. It may well be believed that notions29 of right and duty, and of social welfare, were first developed in connection with ghost fear and other-worldliness, and therefore that, in that field also, folkways were first raised to mores. "Rights" are the rules of mutual give and take in the competition of life which are imposed on comrades in the in-group, in order that the peace may prevail there which is essential to the group strength. Therefore rights can never be "natural" or "God-given," or absolute in any sense. The morality of a group at a time is the sum of the taboos and prescriptions in the folkways by which right conduct is defined. Therefore morals can never be intuitive. They are historical, institutional, and empirical.

World philosophy, life policy, right, rights, and morality are all products of the folkways. They are reflections on, and generalizations from, the experience of pleasure and pain which is won in efforts to carry on the struggle for existence under actual life conditions. The generalizations are very crude and vague in their germinal forms. They are all embodied in folklore, and all our philosophy and science have been developed out of them.

32. The folkways are "true." The folkways are necessarily "true" with respect to some world philosophy. Pain forced men to think. The ills of life imposed reflection and taught forethought. Mental processes were irksome and were not undertaken until painful experience made them unavoidable.63 With great unanimity all over the globe primitive men followed the same line of thought. The dead were believed to live on as ghosts in another world just like this one. The ghosts had just the same needs, tastes, passions, etc., as the living men had had. These transcendental notions were the beginning of the mental outfit of mankind. They are articles of faith, not rational convictions. The living had duties to the ghosts, and the ghosts had rights; they also had power to enforce their rights. It behooved the living therefore to learn how to deal with ghosts. Here we have a complete world philosophy and a life policy deduced from it. When pain, loss, and ill were experienced and the question was provoked, Who did this to us? the world philosophy furnished the answer. When the painful experience forced the question, 30Why are the ghosts angry and what must we do to appease them? the "right" answer was the one which fitted into the philosophy of ghost fear. All acts were therefore constrained and trained into the forms of the world philosophy by ghost fear, ancestral authority, taboos, and habit. The habits and customs created a practical philosophy of welfare, and they confirmed and developed the religious theories of goblinism.

33. Relation of world philosophy and folkways. It is quite impossible for us to disentangle the elements of philosophy and custom, so as to determine priority and the causative position of either. Our best judgment is that the mystic philosophy is regulative, not creative, in its relation to the folkways. They reacted upon each other. The faith in the world philosophy drew lines outside of which the folkways must not go. Crude and vague notions of societal welfare were formed from the notion of pleasing the ghosts, and from such notions of expediency as the opinion that, if there were not children enough, there would not be warriors enough, or that, if there were too many children, the food supply would not be adequate. The notion of welfare was an inference and resultant from these mystic and utilitarian generalizations.

34. Definition of the mores. When the elements of truth and right are developed into doctrines of welfare, the folkways are raised to another plane. They then become capable of producing inferences, developing into new forms, and extending their constructive influence over men and society. Then we call them the mores. The mores are the folkways, including the philosophical and ethical generalizations as to societal welfare which are suggested by them, and inherent in them, as they grow.

35. Taboos. The mores necessarily consist, in a large part, of taboos, which indicate the things which must not be done. In part these are dictated by mystic dread of ghosts who might be offended by certain acts, but they also include such acts as have been found by experience to produce unwelcome results, especially in the food quest, in war, in health, or in increase or decrease of population. These taboos always contain a greater element of philosophy than the positive rules, because the taboos31 contain reference to a reason, as, for instance, that the act would displease the ghosts. The primitive taboos correspond to the fact that the life of man is environed by perils. His food quest must be limited by shunning poisonous plants. His appetite must be restrained from excess. His physical strength and health must be guarded from dangers. The taboos carry on the accumulated wisdom of generations, which has almost always been purchased by pain, loss, disease, and death. Other taboos contain inhibitions of what will be injurious to the group. The laws about the sexes, about property, about war, and about ghosts, have this character. They always include some social philosophy. They are both mystic and utilitarian, or compounded of the two.

Taboos may be divided into two classes, (1) protective and (2) destructive. Some of them aim to protect and secure, while others aim to repress or exterminate. Women are subject to some taboos which are directed against them as sources of possible harm or danger to men, and they are subject to other taboos which put them outside of the duties or risks of men. On account of this difference in taboos, taboos act selectively, and thus affect the course of civilization. They contain judgments as to societal welfare.

36. No primitive philosophizing; myths; fables; notion of societal welfare. It is not to be understood that primitive men philosophize about their experience of life. That is our way; it was not theirs. They did not formulate any propositions about the causes, significance, or ultimate relations of things. They made myths, however, in which they often presented conceptions which are deeply philosophical, but they represented them in concrete, personal, dramatic and graphic ways. They feared pain and ill, and they produced folkways by their devices for warding off pain and ill. Those devices were acts of ritual which were planned upon their vague and crude faiths about ghosts and the other world. We develop the connection between the devices and the faiths, and we reduce it to propositions of a philosophic form, but the primitive men never did that. Their myths, fables, proverbs, and maxims show that the subtler relations of things did not escape them, and that reflection was not wanting, but32 the method of it was very different from ours. The notion of societal welfare was not wanting, although it was never consciously put before themselves as their purpose. It was pestilence, as a visitation of the wrath of ghosts on all, or war, which first taught this idea, because war was connected with victory over a neighboring group. The Bataks have a legend that men once married their fathers' sisters' daughters, but calamities followed and so those marriages were tabooed.64 This inference and the cases mentioned in sec. 28 show a conception of societal welfare and of its relation to states and acts as conditions.

37. The imaginative element. The correct apprehension of facts and events by the mind, and the correct inferences as to the relations between them, constitute knowledge, and it is chiefly by knowledge that men have become better able to live well on earth. Therefore the alternation between experience or observation and the intellectual processes by which the sense, sequence, interdependence, and rational consequences of facts are ascertained, is undoubtedly the most important process for winning increased power to live well. Yet we find that this process has been liable to most pernicious errors. The imagination has interfered with the reason and furnished objects of pursuit to men, which have wasted and dissipated their energies. Especially the alternations of observation and deduction have been traversed by vanity and superstition which have introduced delusions. As a consequence, men have turned their backs on welfare and reality, in order to pursue beauty, glory, poetry, and dithyrambic rhetoric, pleasure, fame, adventure, and phantasms. Every group, in every age, has had its "ideals" for which it has striven, as if men had blown bubbles into the air, and then, entranced by their beautiful colors, had leaped to catch them. In the very processes of analysis and deduction the most pernicious errors find entrance. We note our experience in every action or event. We study the significance from experience. We deduce a conviction as to what we may best do when the case arises again. Undoubtedly this is just what we ought to do in order to live well. The process presents us a constant reiteration 33of the sequence,—act, thought, act. The error is made if we allow suggestions of vanity, superstition, speculation, or imagination to become confused with the second stage and to enter into our conviction of what it is best to do in such a case. This is what was done when goblinism was taken as the explanation of experience and the rule of right living, and it is what has been done over and over again ever since. Speculative and transcendental notions have furnished the world philosophy, and the rules of life policy and duty have been deduced from this and introduced at the second stage of the process,—act, thought, act. All the errors and fallacies of the mental processes enter into the mores of the age. The logic of one age is not that of another. It is one of the chief useful purposes of a study of the mores to learn to discern in them the operation of traditional error, prevailing dogmas, logical fallacy, delusion, and current false estimates of goods worth striving for.

38. The ethical policy of the schools and the success policy. Although speculative assumptions and dogmatic deductions have produced the mischief here described, our present world philosophy has come out of them by rude methods of correction and purification, and "great principles" have been deduced which now control our life philosophy; also ethical principles have been determined which no civilized man would now repudiate (truthfulness, love, honor, altruism). The traditional doctrines of philosophy and ethics are not by any means adjusted smoothly to each other or to modern notions. We live in a war of two antagonistic ethical philosophies: the ethical policy taught in the books and the schools, and the success policy. The same man acts at one time by the school ethics, disregarding consequences, at another time by the success policy, in which the consequences dictate the conduct; or we talk the former and act by the latter.65

39. Recapitulation. We may sum up this preliminary analysis as follows: men in groups are under life conditions; they have needs which are similar under the state of the life conditions; the relations of the needs to the conditions are interests under the heads of hunger, love, vanity, and fear; efforts of numbers 34at the same time to satisfy interests produce mass phenomena which are folkways by virtue of uniformity, repetition, and wide concurrence. The folkways are attended by pleasure or pain according as they are well fitted for the purpose. Pain forces reflection and observation of some relation between acts and welfare. At this point the prevailing world philosophy (beginning with goblinism) suggests explanations and inferences, which become entangled with judgments of expediency. However, the folkways take on a philosophy of right living and a life policy for welfare. Then they become mores, and they may be developed by inferences from the philosophy or the rules in the endeavor to satisfy needs without pain. Hence they undergo improvement and are made consistent with each other.