ALAMALDJIN AND HIS TWIN SISTER HANHAI

ALAMALDJIN BOGDO and his twin sister Hanhai were born in Iryil of a father who was seventy-five years of age and a mother who was sixty.

After the twins were born the father called all the people to a feast of three days' duration. At the feast he took two marrow bones and asked for a man to come forth and name the boy. One old man named him, and received one marrow bone. An old woman then named the twin sister, and got the second bone.

In ten days the skin of a ten-year-old sheep was not big enough for Alamaldjin. When the boy was three years old his father taught him to reckon. When the child played with other children he said always that he would be khan.

This life continued till the boy was eleven, then he hired men to quarry stone, and he built a yurta one verst long, and so high that the roof, which was of silver, seemed to touch the sky. There were seven thousand windows below, and nine thousand windows above. All the outside was covered with silver, and it was finished inside with gold. There were seventy-seven immense chambers in that yurta.

Alamaldjin had many cattle and many people; and he lived in splendor. Fine roads went from his yurta to all places. When seventeen years of age he was so wise and famous that the people made him khan.

For thirteen years his tattles and herds had been uncounted, now he determined to have them counted. The khan had two uncles; he summoned them, and they came on bay horses. He took both by the hands, led them into his yurta and feasted them. "I have no time to count my herds," said the nephew, "will ye do this counting for me?"

They began, but in three days they could not finish counting, there were so many cattle. At last they finished. The cattle in front were very thin and uneasy, those behind very fat and well satisfied. The two uncles cried out when they saw this. They went to their nephew and asked him to choose other pastures. He was not willing to do so.

"My father's cattle did not suffer," said he. "How is it that my cattle suffer?"

"Our nephew does not believe us," said the two uncles, and they went then to hang themselves. "I will not let this come to pass," said Alamaldjin, and he stopped them. "I will go in search of new pastures, and find them."

Alamaldjin had a brown steed ninety fathoms long with ears nine ells high. This steed was in the Altai Deda, beyond mountains, at pasture with thirteen wild deer. He might have called the steed with a whistle, but he did not wish to do that, so he sent his two uncles to bring him.

The uncles went to the Altai Mountains, found the horse, but were dreadfully frightened at sight of him, and came back without him. "Let us go home and hang ourselves," said they. "Our nephew laughs at us, and pays no heed to the advice which we give him."

Alamaldjin blew his whistle; the horse and the thirteen wild deer heard the call. They had pastured together thirteen years, and the thirteen deer said: "We may be lost if we go, but we wish to go with thee."

Altai Deda, the place where they had lived in company, was very beautiful. The water was sweet, the grass an ell high, and the deer did not like to leave it. "Go not," said they to the steed. "Stay thou with us, we are afraid to be without thee." They did not wish to lose the horse; they did not like to leave the mountain.

"Fear not," said the horse. "If I perish the water will dry up, and the grass wither. If I am well all will be as it now is. Have no fear, I shall not perish."

The horse lay down and rolled; some of his hair fell out, as much in bulk as a big stack of hay. "If enemies come," said he, "get under this hair and hide there, ye will be safe from them. If I am well the hair will last many years. If I am lost it will vanish. But I shall not be lost, and this hair will remain here. If ye grieve for me, smell the hair, and ye will be cheerful."

They agreed now to stay in the Altai Mountains.

The horse ran toward his master at full speed, came at the summons of the whistle; rushed to the hitching-post, stood and neighed there.

Alamaldjin hurried out in a single shirt. In one hand he held a bridle, in the other a hair rope. He put a bit in the mouth of his horse and tied him to a hitching-post. The horse stood there three days. Alamaldjin gave him nothing to eat, and only spring water to drink. Then he led him to a sandy place, tied him to another post, left him three days on the sand; next he tied him to a post in an icy place, left him standing on ice three days; that was the last preparation.

Alamaldjin now placed on his steed a silk saddle-cloth and a silver saddle. Then he made himself ready. He wore trousers made of fifty elk skins, shoes of fish-skin, a silken shuba with seventy-five fastenings, a silver belt, and a cap of sable. He took a bow and a quiver with ninety-five arrows. He drank worms, after which he had no need to eat for twenty-five days; then he mounted and rode away swiftly. His uncles were glad.

He rode far, rode into another country, and saw on the edge of the earth an immense iron building which rose to the sky. He made his horse small and wretched, and himself old and full of wrinkles, a Shaman. He reached the great iron building. He tied his horse to a hitching-post, then tried to find a door to the building, but could not, and he broke in the southwest corner of the yurta. Inside was a Mangathai of a hundred and fifty heads. The Mangathai sprang up, and shouted, "Who art thou, who hast dared to break into my house in this manner?"

The Mangathai took his axe, forty fathoms broad, and sharpened it, but when he heard that the strange old man was a Shaman he threw the axe aside. Then it turned out that the right eye of the Mangathai had been struck by an arrow and was injured.

"It is well that a Shaman is here," said he, "my eye is sore."

"It is not difficult to cure thy eye," said Alamaldjin; "let me look at it. Three years ago some one struck thy eye with an arrow; thy sight is poor, there are many worms in thy eye at this moment."

"True," said the Mangathai.

"I will cure thee quickly," said Alamaldjin. "I am afraid thou art so big that a strong remedy is needed. Wilt thou endure it?"

"I will."

The Mangathai brought a hair rope ninety fathoms long. "I will lie down; do thou tie me to the four corners of the chamber, and fasten me so that I shall not move."

Alamaldjin tied him firmly, took a great pot, put it on the tripod of the central fire, then filled the pot with lead. When the lead was melted, Alamaldjin said, "Look at the sky with thy sound eye, count the stars in it. Look to one side with thy sick eye."

The Mangathai did so, and Alamaldjin poured the whole kettle of molten lead into the well eye. The Mangathai felt dreadful pain; he trembled, pulled, roared. Alamaldjin found three iron doors closed; he broke them and rushed out. He saw a yellow goat on the road with horns three ells long. The khan turned himself into a flea and sat on the goat's ear contentedly.

The Mangathai tugged at the rope, pulled three times, tore it to bits, and rushed out to find the Shaman, but could not see him. The goat ran to the Mangathai and butted him. The Mangathai saw a little yet with his injured eye. The goat butted him a second time; he fell, hurt his forehead, and was terribly angry.

"That goat never came near me before," said the Mangathai to himself, "now when my eye is gone he butts me."

The Mangathai made an iron wall with his magic, a very high wall, so the Shaman might not save himself. Then he took the goat and threw him over the high enclosure. The flea stayed in the goat's ear till he was outside, then it became Alamaldjin. Alamaldjin mounted his horse and called to the Mangathai, "Well, is thy eye any better?"

"It is better, thanks to thee. For reward I will give thee this axe!" And he threw the axe over the wall at Alamaldjin, intending to kill him. The axe did not hit Alamaldjin. He picked it up, stuck it in the wall of another yurta, and said, "Stay here till I come, see that this Mangathai does not leave that house and enclosure. This place will be mine hereafter; my pastures will be here."

All the Mangathai's magic, all his strength, was in that axe.

Now Alamaldjin went home. The two uncles knew what had happened to their nephew. They killed ten sheep, made many kettles of tarasun, and went out to meet him. They stopped at Red Mountain, built a shed there, and waited.

When the nephew appeared they went to meet him. "We are here to greet thee," said they; "we have brought a feast with us."

Alamaldjin was angry, "Why have ye come? why bring a feast? why can I not go home alone?"

"We did this as a mark of respect, because thou hast conquered a great Mangathai."

He tied his horse to a tree and went into the shed with his uncles. First they gave him ten pots of tarasun. He emptied them all and became very gladsome. Next he ate ten sheep. "Is there no more tarasun?" asked he. They gave him a small keg of tarasun mixed with poison. He drank of it, and fell to the ground. Blue and red flames came from his nostrils.

"Though ye have killed my master, I will not yield to you!" said the horse, and he broke away and rushed home. He reached the yurta, ran to the hitching-post, and neighed very loudly.

Alamaldjin's sister came out, embraced the horse's feet, and fell to crying, "How is thy master? where is he?"

"My master is dead at the boundary; thy two uncles have killed him." Hanhai mounted and rode to the boundary quickly. Her brother's body was lying in the shed; she found no one there with it. She tied two silk cloths around the body, and wrapped it up carefully. Not far away was Red Mountain; she buried her brother at the foot of that mountain and went home. In her brother's yurta was his book; she read this book and learned from it how to guard against death, and how to bring the dead back to life. This is what the book said:

"Far away, on the opposite end of the earth, is an impassable swamp, in the middle of that swamp is a golden aspen with silver leaves, at the foot of that aspen tree is the Water of Life. On the top of the tree sits a cuckoo. If any one goes there the cuckoo will help them; the water will heal and bring the dead back to life again."

The sister put on her brother's dress, took his weapons, mounted his steed, and rode away swiftly. At the end of six days she was near the impassable swamp. She made her horse a flint chip, and put him into her pocket, then she turned herself into a raven.

It was forty versts from the edge of the swamp to the living water. She had a small keg and flew to the place. The water flowed up out of the earth sweet and pure. The cuckoo was not there. The raven drank of the water, and then filled a small keg. After that she turned into a reed and watched, waiting for the cuckoo.

At midday the cuckoo flew home and drank water. The reed seized the bird by the neck, grasped her tightly.

"Let me go!" cried the cuckoo; "or if thou wish to kill, then kill quickly. Art thou Hanhai?"

"I am," said the sister. "I have come for thee to save my brother."

"I will go with thee," said the cuckoo. Then both flew back to where Alamaldjin was buried. There the sister took her own form and prayed to the Heavenly Burkans for three days. On the third day the ground opened and Hanhai drew out the body. It was in good condition, except the right shoulder-blade; a fox had dug into the grave and carried off that shoulder-blade. Hanhai told the cuckoo to watch the body while she herself followed the trail of the fox.

She went to Shara Dalai (the Yellow Sea) and found the fox there. She had the shoulder-blade in her mouth when Hanhai met her.

"What art thou doing with that shoulder-blade?" asked the sister.

"I took it to a Shaman to have him soothsay. This is the third day that I have a headache. The Shaman knew that it was thy brother's and sent me back with it. I am going now to where thy brother is buried."

"What right hadst thou to take the shoulder-blade from a dead man? Who gave thee permission?"

"I hunted the world over, but could not find a shoulder-blade of man or beast. Passing thy brother's grave I knew by the odor that a corpse was lying in it, then I made bold to take the shoulder-blade. I will give it back to thee. Do not beat me."

Hanhai took the shoulder-blade and forgave the fox. Then she returned and found the cuckoo guarding her brother. She put the shoulder-blade in its right place and poured the Water of Life on her brother's body, which took on its own form again quickly. The cuckoo began to sing, began at his feet and sang till she stopped at the crown of his head. Then Alamaldjin stood up well and said, "How long I have been sleeping here!"

Alamaldjin and Hanhai went home. They took the cuckoo with them, and gave her good entertainment,--entertained her one day.

"We shall be friends from this time, and forever," said Alamaldjin when the cuckoo was going. "Be thou kind, and assist us."

"I will," said the cuckoo, "whenever the need comes."

"I am going out to hunt," said Alamaldjin on the following day to his sister.

"Hunting is good," said Hanhai, "but thou shouldst rest ten days at least."

"Why rest? I shall hunt on my own land." And he rode away quickly.

In the forest he met a woman as tall as a pine tree--the wife of that Mangathai whose eye he had put out, and who was dead now. She had been hunting for Alamaldjin. This woman held in her hand a scraper ten fathoms long,--the scraper was for dressing rawhide.

"Oh, look!" called she, "see how many men are coming behind thee!"

He looked around. She hit him on the back of his neck, and he fell with head on the right side of the horse, and body on the left. The horse ran toward home. The Mangathai woman followed the horse, but failed to catch him.

"What good is a horse without a master? What good is a wife without a husband?" cried she as the horse rushed away from her.

Again the horse neighed loudly at the hitching-post. Hanhai ran out, embraced his feet, and cried: "Where is my brother?"

"The Mangathai's wife has killed thy brother in his own forest."

Hanhai put her brother's dress on, mounted his steed, and rode off to meet the Mangathai woman. Rode straight to her; she knew by her magic power where the tall woman was. Hanhai turned herself into a man; the Mangathai woman did not know her. As Hanhai passed the tall woman she called out to her, "Whence comest thou, O woman? Who art thou?"

"I am the wife of a Mangathai."

"What art thou doing in this forest?"

"I have lost a flock of sheep, a herd of horses, and many cattle. I have asked every one where to look for them, but cannot find them. But look around!" cried the woman on a sudden, "see how many men are behind thee!"

"Let them stay behind me, they are my people. Look behind thyself! There are twenty Mangathais coming against thee!" said Hanhai.

The tall woman forgot herself, looked, and Hanhai dealt her such a blow with her strong, sharp whip that she took the woman's head off. The Mangathai's horse ran away. Hanhai followed on her swift steed, caught him, brought him back, and killed him. She gathered wood and burned up the horse and the Mangathai woman.

Hanhai then went to find her brother. First she found his head and then his body; she put them together, wrapped them in two silk cloths, tied the bundles to the saddle, and went to Red Mountain, where her brother was buried the first time. She prayed one day and one night to the Heavenly Burkans, then buried him deep, far from foxes and other animals.

Then Hanhai went home, searched the book, and read in it: "In the west lives Gazar Bain Khan. He has a daughter, Nalhan Taiji Basagan; she is the only person in all the world who can raise Alamaldjin the second time. But to raise him she must become his wife; she must marry him."

When Hanhai finished reading she cried, "I am a maiden; how can I go to that country?"

She read the book three days and three nights and then prepared to go. She put on her brother's clothes, took his weapons, mounted his steed, and rode to the boundary.

"All is left behind," thought Hanhai; "what will become of the people and the cattle, who will protect them?" But she had immense magic power, and by that power she made a great iron wall around the whole country; then she made a flat dome of silver above it. Over the silver she put earth, and made grass and trees grow out of it; so that her brother's whole country, with the people, flocks, herds of horses, cattle, and everything that was in it, was hidden and unseen by all the world outside. On the east she left small, secret apertures to let in the sunshine. Then she rode westward swiftly in search of Nalhan Taiji Basagan.

Hanhai went far, rode three weeks, till at last she saw a great white stone yurta. She rode up to the yurta, and found ninety horse skulls on ninety stakes, and on ninety other stakes ninety outfits of men and horses. She stopped her steed and shed many tears.

With women hair is long, but thought is short. She stood a while thinking, strengthening her heart, and then she said to herself, "Once I have started on this business I will go to the end of it."

She made her horse a flint chip, put the chip in her pocket, turned herself into a skunk, burrowed under the yurta and into it. Burrowed forward, peeped up at last through the floor, and saw a Mangathai sleeping. He had seven hundred heads on his body, and seventy horns on the heads.

"I have never heard," thought she, "of a Mangathai with so many heads; this must be the greatest, the father and chief of all Mangathais."

Near the Mangathai lay an axe eighty fathoms broad. Hanhai became Alamaldjin, seized the axe, roused the Mangathai, and said to him, "I have come to thee with battle!"

He woke, strove to rise; she hewed his central head off with the axe, which was full of magic. "Cunning people have come; this is the end of me!" these were the last words of the seven hundred headed Mangathai.

Hanhai made a forest by magic, and on one of the largest of the trees she wrote, "This will be a sacred forest henceforward;" then she mounted and rode away.

Next she met a twenty-seven headed Mangathai on horseback.

"Why art thou riding through my father's land?" asked he. "No man passes on foot or on horseback and remains alive after that. I will hurry home, read in my book, and see who killed my brother by magic. I will hunt and slay the one who killed him." As he turned to go home Hanhai sent an arrow after him, saying to the arrow, "If thou kill that Mangathai and his horse come back to me." The arrow came back and said to her, "The Mangathai and his horse are dead."

Hanhai rode on, but soon met another Mangathai, this one had seventy-seven heads, and called out, "What kind of man art thou, and from what country?"

"People call me Alamaldjin Bogdo," said she.

"I have heard," replied the Mangathai, "that such a one was born. Art thou he?"

"I am."

"My father and I wished to go to-morrow and kill thee," said the Mangathai, "and now thou art here of thyself. That is well! Thou hast killed many already, but I have finished better than thou art. What work will there be with thee? Get down from thy horse!"

Hanhai slipped down quickly. They sprang at each other and the struggle began,--a dreadful struggle, with teeth and with hands. Three days and three nights they fought. There was no flesh left on the Mangathai; all his ribs and bones were visible. On the fourth day he fell. He roared terribly. Hanhai went to a larch tree, opened it, cut off some of the Mangathai's heads and thrust him in there. With magic power she hooped the tree up with ninety-five hoops, all of them iron; killed the Mangathai, killed his horse, and went farther.

Soon she met a Mangathai with five hundred heads, fifty horns on the heads and a goat-skin thrown over his shoulders.

"Thou hast killed my father and two brothers; whither now?" shouted the Mangathai, springing from his horse. "I will tear thee into bits!"

"Very well," answered Hanhai, coming down from her steed. They rushed at each other, fought nine days and nine nights without stopping. Ravens and magpies flew in from the north and the south and called out to them: "Fight on, good heroes! Fight on! Give us flesh, give us plenty of it."

"We can do nothing by wrestling," said the Mangathai. "Let us use arrows now. I will go to the southwest, thou to the northeast mountain and shoot from there."

Hanhai consented. They were to rest for one day.

The Mangathai had arrows as big as a larch tree. Hanhai rested near a forest. Two elks came into view; she killed both. Then she made a fire, took a pine and a larch tree for spits and roasted the elks. She rose up at sunrise and ate the animals.

The Mangathai signaled to begin. "I must shoot first," cried he.

"No," said Hanhai; "I came in search of thee, I will shoot first."

"I will never agree to that!" screamed the Mangathai. "Thou hast killed my father and two brothers, now it is thy wish to kill me!"

"Shoot!" said Hanhai, and she lay down. The Mangathai's arrow hissed and roared as it flew toward her, but she turned instantly into a very hard stone and the arrow broke in two on that stone. She became Hanhai again, thrust the broken arrow into her saddle, and signaled to the Mangathai, "Thou art not able to hit me, thou hast only hit my saddle."

"I missed," said the Mangathai, "but do not shoot at me to-day, shoot to-morrow."

"Am I to wait days to please thee? I will shoot now!" cried Hanhai, and she sent a magic arrow. That arrow shivered the Mangathai into fragments, broke him into small pieces. Hanhai went then to the broken body of the Mangathai. His horse did not run away, but stood weeping there near his master. Hanhai killed the horse, collected wood, and burned master and horse into ashes.

After that she rode farther; rode swiftly, till she came at last to two seas, where the land between was only one ell wide and rose one ell above the water. The sea on the right was a poison sea, the sea on the left was a sea of fresh water. Hanhai halted, and said to her steed, "Thou canst not pass this sea." She made flint of him and turned herself into a swallow, then she flew on, flew for three hours, reached the other side, then turned herself and the horse back to their own forms.

There was a very high mountain on the road straight out in front of them. At the foot of it were blind, crooked, lame, and deformed people, people with every ill possible, and the bodies of dead men and of dead horses. There were mounds of those bodies, piles of them, hills of them. When Hanhai saw these heaps of bones of the men and horses that had fallen while trying to climb the great mountain she asked her steed, "Canst thou cross this mountain or not?"

"I cannot cross, as thou knowest," said the horse.

She made a flint chip of the horse, put the chip in her pocket, turned herself into a squirrel and ran up the mountain. She ran on and on till her paws were nearly gone, till she had climbed one third of the mountain, and was falling; then she caught on a tree and became a skunk. As a skunk she went up the second third with great difficulty; then became a swallow, and flew the last third of the way. Three days and three nights and the half of another day was she flying till she dropped on the summit, and lay there without stirring for one whole day and a half of a day. Then she revived and looked around. Right there in front of her was a spring of the Water of Life, Youth, and Health. A gold goblet hung from a bough of the tree by a chain of pure silver. Hanhai drank, gave her horse to drink, and then made a fire.

The next morning she felt stronger and better. She drank again from the water of the spring. After that she looked and saw far away the great yurta of Gazar Bain Khan; she saw also his countless cattle and horses. The yurta was immense, a verst long, a great white house of silver, glistening and glorious, straight out southwest from her.

She mounted immediately and rode to the house of Gazar Bain Khan. Three horses were tied to a hitching-post near it. She tied hers also and entered. Three splendid young men had entered before her.

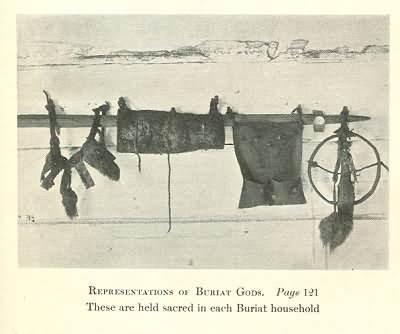

REPRESENTATIONS OF BURIAT GODS.

These are held sacred in each Buriat household

"A greeting from me to thee, father-in-law!" said Hanhai.

"Whence hast thou come, a son of what khan art thou?" asked Gazar Bain Khan.

"I am Alamaldjin Bogdo. I have heard that thou hast a beautiful daughter, Nalhan Taiji is her name; I have come to ask for her. In my book it is written that she must be my bride."

"These suitors here came earlier; they have not spoken yet. Why dost thou hurry so?"

"I had no thought to wait for them or for others. I tell at once what my wish is."

"We came to ask for thy daughter," said the three young men.

"She will choose whom she likes; I will not force her," said the father.

"Are we to wait here or go to her?"

"Spend the night here. To-morrow I will call all the people. Let my daughter come out then and choose him who may please her."

Next day there was a feast. Nalhan Taiji, who was behind forty-three doors in the forty-third chamber, came out. Her father gave her a goblet of wine and a marrow bone to give to the man who pleased her most.

"Here are four bridegrooms," said he, "give these to the one you like best."

She looked a number of times at the four, and at last gave the bone and the wine to Hanhai. When the choice was made the people and the suitors went away

"Go to thy bride and rest; thy horse will be cared for and fed," said the father-in-law.

Nalhan Taiji was waiting in her chamber. Drink, food, and all things were ready. They sat there and feasted till night was near, then Hanhai sprang up. "I must go now," said she, "I may not stay with thee longer. Since my horse is enchanted, it is impossible to stay."

"It cannot be! On that horse thou travelest, how can thy stay here affect him? What sort of bridegroom art thou to leave me thus?"

"Only let me go home on this horse, then I will leave him. I will send him back to the Altai Deda, where he pastures in the mountains with thirteen wild deer. In all this world he is the luckiest and best horse for the road. No ill is possible with him, but misfortune would happen in a moment were I to break his enchantment, which is this, that no man fully married may ride him. Not only should I die, but my wife would die also."

Nalhan Taiji believed her bridegroom now; she let him go from that forty-third chamber. The next morning his father-in-law called him: "I will give thee my daughter, but thou must do something for me: bring me a quill from the wing of Khan Herdik, I wish to write with it. If thou bring not the quill I will not give my daughter."

"How is this?" asked Hanhai. "I have barely ridden to thee, and now must I go to another country?"

"Do as may please thee. Bring me the quill or thou wilt not get my daughter."

"I will go, but let me see Nalhan Taiji."

Hanhai went to her bride. "I am going on a long journey," said she; "thou must help me in some way."

"Thou wilt meet no hindrance on the journey; but Herdik Khan will delay in giving thee the feather. This is the second year that he is fighting with Mogoi Khan. Thou wilt not get the quill till the war is ended."

"I cannot wait till the war is ended," said Hanhai. "I must go at once and thou must assist me."

"Thou wilt not feel hunger or need much sleep. I cannot give thee other assistance," said Nalhan Taiji.

Hanhai rode away swiftly. On the fifth day she came to an immensely high mountain. On that mountain stood a great pine; ten men could not embrace it. On that tree lived Khan Herdik and his two daughters.

"Whence dost thou come, good youth?" asked the daughters of Hanhai.

"I am Alamaldjin Bogdo, I have come on business to thy father."

"Art thou a khan? Was thy father a khan also?" asked Khan Herdik's elder daughter. "Our father is at war with Mogoi Khan. He is near the Icy Ocean, but thou canst go to him."

Hanhai set out for the Icy Ocean, and when she reached it Khan Herdik had arrived three days earlier. She found him on a great pine tree near the ocean shore. Hanhai bowed down to Khan Herdik. "A greeting from me to thee!" said she, and then told him the cause of her coming.

"I cannot give thee a feather now," said Herdik. "In four days I must fight with Mogoi Khan. If thou help me I will give thee my feather."

Hanhai agreed, made her horse into a flint, put him in her pocket, became an eagle herself, and sat there on the pine tree with Herdik.

"Mogoi Khan comes out of that valley," said Khan Herdik. "He has two heads, and between the two is a shining white spot; if thou hit that spot he is dead. I will fly away with thee then and give thee a quill."

On the fourth day Mogoi Khan came out of the Icy Ocean and came through the valley straight toward them. If Mogoi Khan conquered, he was to get Khan Herdik's daughters. If Khan Herdik conquered, he would have Mogoi Khan's daughters.

When Mogoi Khan was near enough Hanhai saw the white spot, sent her arrow into it, and killed Mogoi, then took her own form. Herdik Khan put her on his back and hurried to his daughters at the pine tree, and there they feasted three whole days.

"Thanks for thy aid. Take the quill," said Herdik. "Tell thy father-in-law that he will hardly lift that quill to write. But thou and I will be friends in the future."

Hanhai returned to her father-in-law. On the sixth day she reached his yurta, tied her horse to the hitching-post and left the feather leaning against the corner of the yurta. The great building bent till it was near falling.

"Misfortune will come from this quill! It will break down my yurta!" cried Gazar Bain Khan. "Take it away! Take it back to Khan Herdik!"

"Have the wedding and I'll take it." Hanhai turned then to Nalhan Taiji: "I have brought the quill, now your father does not want it, and asks me to take it back."

"You need not take it back yourself; make it small, tie it to your arrow, and tell the arrow what to do."

Hanhai did as her bride advised. "Do no harm to Khan Herdik," said she to the arrow, "only return the feather to him."

The arrow did as commanded and came back again. The next day the people had all assembled for the wedding when a female Shaman cried out: "What a misery! Our khan is crazy to give his daughter to a woman!"

The khan was frightened and sent for Gazari Ganek, a champion, to try the bridegroom in a contest. Hanhai hurried to her steed. "What am I to do now? How am I to hide my bosom?"

"Bind two silk kerchiefs around thy breast and tie them tightly crosswise. All will be well then."

"What answer can I give if people ask why I do this?"

"Say that thy breast was injured by thy horse, and thou must keep it bound in this manner."

Gazari, the champion, did not seem so very heavy or tall, but he was strong and stalwart. Hanhai dismounted, took off her outer dress and stood in wrestler's trousers. Her horse whispered to her, "I will snort and raise a cloud of dust; then seize him, hurl him high above thy shoulder, and drive him deep into the earth before thee."

When she went out to wrestle people asked, "Why is thy breast bound?"

"My horse hurt me on the road and I had to bind up my breast."

"That may be so," said the people.

The two closed; their strength was nearly equal. The horse snorted, raised a terrible dust. Hanhai seized Gazari, hurled him high above her shoulder and dashed him to the earth. He fell head downward, and went into the ground to his shoulders. She grasped his legs, pulled him out and threw him to one side.

"What kind of champion is this?" asked she.

The champion was very heavy, nine horses drew him away. "I say that this bridegroom is a woman!" cried Shorgo, the Shaman. "Let four men go to the sea and swim with her; they will find out then what she is."

Four men hurried off to Narin Dalai (Narrow Sea). Hanhai mounted and rode to the shore. The men were already in the sea when she came in sight. The horse snorted. The waves rushed high upon the shore and spray was dashed everywhere. Hanhai undressed while the waves were roaring madly; no one could tell whether she was man or woman. She swam out very far from shore, swam quickly around the men, passed them. No one could come near her or catch her, she swam with such swiftness. At last she swam in directly to shore. The horse snorted. Again the waves rose high. Waves and thick spray were around her, and before the men could come to shore she was out, dressed, and on horseback.

"What shall we say?" asked the men of one another. "Shall we say man or woman when the khan asks us?"

"Of course say man," replied one of the four. And all agreed to say man.

The khan asked the four, "Is the bridegroom a man or a woman?"

"A man," said the four.

Again Shorgo sang out: "This is a woman, this is no man! This is a woman, this is no man!"

Hanhai now made a gray wolf by magic. Not far from the khan's yurta a herd of five hundred horses were grazing. The gray wolf sprang at the horses. When they saw the great creature they were frightened and ran, stampeded to the yurta. There was great terror among the people; they had to follow and kill the gray wolf. Shorgo, the Shaman, was left alone. Hanhai slipped into the place. There was a large barrel of sour milk standing near. She seized the witch and put her head first into the barrel.

When the khan came back from killing the wolf the bride-groom took the Shaman woman by the feet and stirred the milk with her as with a stick.

"How is this?" asked Hanhai. "Instead of wood you mix milk with an old woman. You stir milk with people's bodies!"

"What a wonderful thing!" exclaimed the khan. "I left this old woman here alive and well. How did she fall into the milk barrel?"

"I suppose," said the bridegroom, "that she crawled into the milk from fright when the wolf was running after the horses."

"But what shall I do with her now?" asked the khan. "This woman was a Shaman; people may think that I killed her; they may say so."

"They will say so, surely," said Hanhai. "But give me thy stallion, I'll mount him, and carry the old woman off to her own yurta very quickly."

The stallion was brought. Hanhai, who had driven a nail into each of her boot heels, mounted and took the old woman. Shorgo, the Shaman, swayed like a drunken person as the stallion rushed forward. When Hanhai reached the old woman's yurta she called to the Shaman's three daughters, "Come out and take your mother; she is drunk!" Then she drove a nail into one side of the horse with her heel. The girls ran out. The stallion, made wild by the prick of the nail, sprang aside quickly; threw both the old woman and the bridegroom. The bridegroom fell under, was senseless, seemed dead; the horse ran off home madly.

Hanhai lay motionless; she waited to hear what the daughters would say. All three began to cry. "If only our mother had died it would not have been so bad, but now the khan's son-in-law is killed, what will happen? What will become of us?"

After a while the bridegroom recovered. "It appears," said he to the old woman's daughters, "that I only fainted, but maybe your mother is killed."

"We were only weeping for you. We can outlive the loss of our mother," said the daughters.

Hanhai went back on foot to the khan's yurta. The khan was glad to be freed from the suspicion of killing the Shaman woman. "Now, father-in-law, we must have the wedding immediately," said Hanhai.

The wedding began again on the morrow, and lasted nine days and nine nights. "What present will you give me?" asked the bride of her father, when she was ready to go home with her bridegroom.

The father gave her a horse ninety fathoms long with ears nine ells high. The mother gave her a silver goblet; the brother a silk, magic kerchief, which had power to bring a dead man to life and make a poor man rich.

The young couple started for home, and the people followed. Hanhai fastened a larch tree to her horse's tail, and rode on ahead to show the places for rest, refreshment, smoking, and night camps.

On the seventh day Hanhai was almost in view of her hidden kingdom. Before she came up to this covered country she said to the young wife, "I must hurry home before thee; I am sure there is bad management. I must put things in order, and make ready to receive thee. Follow on my trail." She hurried quickly to the boundary, removed the iron walls. The silver dome, the grass, and forest all vanished.

Then, instead of going home directly, Hanhai rushed off to her brother's grave at Red Mountain, raised the body, and took it home with her. There was nothing left save the skeleton; this Hanhai put in the yurta, which the bride must enter first, and then the guests who followed with her. She put the bones on the floor near the door, turned herself into a fly, sat in the room, and waited.

The guests rode up quickly. Hanhai's father and mother were so old now that they did not leave the yurta. Bride and guests entered. The skeleton was on the floor before the bride.

"How quickly thou art asleep!" said the bride, and raising the blanket she saw the skeleton, and was terribly frightened. Hanhai, who had undressed before turning into a fly had thrown the clothes near her brother's skeleton. The bride had power, was possessed of great magic. "Since things are thus they must be cured," thought she, and stepped thrice over the skeleton. Then she took juniper leaves, put them into her silver goblet, burned them, and walked thrice around the bones while the leaves were burning. Next she threw leaves and coals into the fire, and covered the skeleton head with the goblet turned bottom upward, then she waved her kerchief thrice, saying each time before she waved it, "How long thou art sleeping!" The third time that Nalhan Taiji waved the kerchief Alamaldjin sprang up.

"Somehow I have slept long," said he. Immediately he commanded the people to come, and all feasted. They feasted nine days and nine nights with great pleasure.

The fly slipped out of the yurta. Not far away was a forest, and it flew there. The fly made itself into a hare in that forest. Three days later Alamaldjin, while out to look for wild beasts, saw many hare tracks. "There are hares in this place. We should trap them," said he; and he went to set traps. The next day, when he looked at his traps he found one hare caught, but alive yet.

"See what a nice hare I have caught. I will tame it, and keep it as a pet," said Alamaldjin; and he took the hare to the yurta. The hare seemed fond of Nalhan Taiji, ran after her whenever she stepped out of the yurta.

"I will go and see what is happening in my pastures," said Alamaldjin one day.

While he was away his wife began to make a silk shuba. The hare came in, stood on its hind legs, and looked at her sewing. This watching annoyed the young woman. At last she threw pincers at the hare, wounded her nose and scratched it. When the husband came home the hare was sitting near the door. "Who beat this poor hare?" inquired Alamaldjin.

"I was sewing; it came near me too often, annoyed me; I threw pincers at it," said the wife.

"Better kill the poor beast than torment it. Why torment it? I will not permit this." And he began to beat his wife, beat her soundly.

"Do not beat me!" screamed Nalhan Taiji. "I will not strike the hare a second time."

The hare ran away then, ran outside. Alamaldjin beat on, beat his wife more. She began to cry bitterly. The hare turned to a woman and went into the yurta.

"What art thou doing, brother?" cried she. "Thou art beating the wife whom I brought thee. How much have I suffered from thy folly already? How much have I passed through?" Then she told the whole story. Told how her brother had died twice; told all the wonders. Then came tarasun and a feast. There was much conversation and great joy.

"I will not go far away from thee," said Hanhai to her brother the next morning. "Make me a white stone yurta with silver roof." He did so, and she lived ever after in that white stone yurta which Alamaldjin Bogdo built for her.

Next: The Twin Boys, Altin Shagoy and Mungun Shagoy