"She gave him a touchstone and flint"

In Russia, as elsewhere in the world, folklore is rapidly scattering before the practical spirit of modern progress. The traveling peasant bard or story teller, and the devoted "nyanya", the beloved nurse of many a generation, are rapidly dying out, and with them the tales and legends, the last echoes of the nation's early joys and sufferings, hopes and fears, are passing away. The student of folk-lore knows that the time has come when haste is needed to catch these vanishing songs of the nation's youth and to preserve them for the delight of future generations. In sending forth the stories in the present volume, all of which are here set down in print for the first time, it is my hope that they may enable American children to share with the children of Russia the pleasure of glancing into the magic world of the old Slavic nation.

THE AUTHOR.

THE TABLE OF CONTENTS

FOLK TALES

The Tsarevna Frog

In an old, old Russian tsarstvo, I do not know when, there lived a sovereign prince with the princess his wife. They had three sons, all of them young, and such brave fellows that no pen could describe them. The youngest had the name of Ivan Tsarevitch. One day their father said to his sons:

"My dear boys, take each of you an arrow, draw your strong bow and let your arrow fly; in whatever court it falls, in that court there will be a wife for you."

The arrow of the oldest Tsarevitch fell on a boyar-house just in front of the terem where women live; the arrow of the second Tsarevitch flew to the red porch of a rich merchant, and on the porch there stood a sweet girl, the merchant's daughter. The youngest, the brave Tsarevitch Ivan, had the ill luck to send his arrow into the midst of a swamp, where it was caught by a croaking frog.

Ivan Tsarevitch came to his father: "How can I marry the frog?" complained the son. "Is she my equal? Certainly she is not."

"Never mind," replied his father, "you have to marry the frog, for such is evidently your destiny."

Thus the brothers were married: the oldest to a young boyarishnia, a nobleman's child; the second to the merchant's beautiful daughter, and the youngest, Tsarevitch Ivan, to a croaking frog.

After a while the sovereign prince called his three sons and said to them:

"Have each of your wives bake a loaf of bread by to-morrow morning."

Ivan returned home. There was no smile on his face, and his brow was clouded.

"C-R-O-A-K! C-R-O-A-K! Dear husband of mine, Tsarevitch Ivan, why so sad?" gently asked the frog. "Was there anything disagreeable in the palace?"

"Disagreeable indeed," answered Ivan Tsarevitch; "the Tsar, my father, wants you to bake a loaf of white bread by to-morrow."

"Do not worry, Tsarevitch. Go to bed; the morning hour is a better adviser than the dark evening."

The Tsarevitch, taking his wife's advice, went to sleep. Then the frog threw off her frogskin and turned into a beautiful, sweet girl, Vassilissa by name. She now stepped out on the porch and called aloud:

"Nurses and waitresses, come to me at once and prepare a loaf of white bread for to-morrow morning, a loaf exactly like those I used to eat in my royal father's palace."

In the morning Tsarevitch Ivan awoke with the crowing cocks, and you know the cocks and chickens are never late. Yet the loaf was already made, and so fine it was that nobody could even describe it, for only in fairyland one finds such marvelous loaves. It was adorned all about with pretty figures, with towns and fortresses on each side, and within it was white as snow and light as a feather.

The Tsar father was pleased and the Tsarevitch received his special thanks.

"Now there is another task," said the Tsar smilingly. "Have each of your wives weave a rug by to-morrow."

Tsarevitch Ivan came back to his home. There was no smile on his face and his brow was clouded.

"C-R-O-A-K! C-R-O-A-K! Dear Tsarevitch Ivan, my husband and master, why so troubled again? Was not father pleased?"

"How can I be otherwise? The Tsar, my father, has ordered a rug by to-morrow."

"Do not worry, Tsarevitch. Go to bed; go to sleep. The morning hour will bring help."

Again the frog turned into Vassilissa, the wise maiden, and again she called aloud:

"Dear nurses and faithful waitresses, come to me for new work. Weave a silk rug like the one I used to sit upon in the palace of the king, my father."

Once said, quickly done. When the cocks began their early "cock-a-doodle-doo," Tsarevitch Ivan awoke, and lo! there lay the most beautiful silk rug before him, a rug that no one could begin to describe. Threads of silver and gold were interwoven among bright-colored silken ones, and the rug was too beautiful for anything but to admire.

The Tsar father was pleased, thanked his son Ivan, and issued a new order. He now wished to see the three wives of his handsome sons, and they were to present their brides on the next day.

The Tsarevitch Ivan returned home. Cloudy was his brow, more cloudy than before.

"C-R-O-A-K!.C-R-O-A-K! Tsarevitch, my dear husband and master, why so sad? Hast thou heard anything unpleasant at the palace?"

"Unpleasant enough, indeed! My father, the Tsar, ordered all of us to present our wives to him. Now tell me, how could I dare go with thee?"

"It is not so bad after all, and might be much worse," answered the frog, gently croaking. "Thou shalt go alone and I will follow thee. When thou hearest a noise, a great noise, do not be afraid; simply say: 'There is my miserable froggy coming in her miserable box.'"

The two elder brothers arrived first with their wives, beautiful, bright, and cheerful, and dressed in rich garments. Both the happy bridegrooms made fun of the Tsarevitch Ivan.

"Why alone, brother?" they laughingly said to him. "Why didst thou not bring thy wife along with thee? Was there no rag to cover her? Where couldst thou have gotten such a beauty? We are ready to wager that in all the swamps in the dominion of our father it would be hard to find another one like her." And they laughed and laughed.

Lo! what a noise! The palace trembled, the guests were all frightened. Tsarevitch Ivan alone remained quiet and said:

"No danger; it is my froggy coming in her box."

To the red porch came flying a golden carriage drawn by six splendid white horses, and Vassilissa, beautiful beyond all description, gently reached her hand to her husband. He led her with him to the heavy oak tables, which were covered with snow-white linen and loaded with many wonderful dishes such as are known and eaten only in the land of fairies and never anywhere else. The guests were eating and chatting gayly.

Vassilissa drank some wine, and what was left in the tumbler she poured into her left sleeve. She ate some of the fried swan, and the bones she threw into her right sleeve. The wives of the two elder brothers watched her and did exactly the same.

When the long, hearty dinner was over, the guests began dancing and singing. The beautiful Vassilissa came forward, as bright as a star, bowed to her sovereign, bowed to the honorable guests and danced with her husband, the happy Tsarevitch Ivan.

While dancing, Vassilissa waved her left sleeve and a pretty lake appeared in the midst of the hall and cooled the air. She waved her right sleeve and white swans swam on the water. The Tsar, the guests, the servants, even the gray cat sitting in the corner, all were amazed and wondered at the beautiful Vassilissa. Her two sisters-in-law alone envied her. When their turn came to dance, they also waved their left sleeves as Vassilissa had done, and, oh, wonder! they sprinkled wine all around. They waved their right sleeves, and instead of swans the bones flew in the face of the Tsar father. The Tsar grew very angry and bade them leave the palace. In the meantime Ivan Tsarevitch watched a moment to slip away unseen. He ran home, found the frogskin, and burned it in the fire.

Vassilissa, when she came back, searched for the skin, and when she could not find it her beautiful face grew sad and her bright eyes filled with tears. She said to Tsarevitch Ivan, her husband:

"Oh, dear Tsarevitch, what hast thou done? There was but a short time left for me to wear the ugly frogskin. The moment was near when we could have been happy together forever. Now I must bid thee good-by. Look for me in a far-away country to which no one knows the roads, at the palace of Kostshei the Deathless;" and Vassilissa turned into a white swan and flew away through the window.

Tsarevitch Ivan wept bitterly. Then he prayed to the almighty God, and making the sign of the cross northward, southward, eastward, and westward, he went on a mysterious journey.

No one knows how long his journey was, but one day he met an old, old man. He bowed to the old man, who said:

"Good-day, brave fellow. What art thou searching for, and whither art thou going?"

Tsarevitch Ivan answered sincerely, telling all about his misfortune without hiding anything.

"And why didst thou burn the frogskin? It was wrong to do so. Listen now to me. Vassilissa was born wiser than her own father, and as he envied his daughter's wisdom he condemned her to be a frog for three long years. But I pity thee and want to help thee. Here is a magic ball. In whatever direction this ball rolls, follow without fear."

Ivan Tsarevitch thanked the good old man, and followed his new guide, the ball. Long, very long, was his road. One day in a wide, flowery field he met a bear, a big Russian bear. Ivan Tsarevitch took his bow and was ready to shoot the bear.

"Do not kill me, kind Tsarevitch," said the bear. "Who knows but that I may be useful to thee?" And Ivan did not shoot the bear.

Above in the sunny air there flew a duck, a lovely white duck. Again the Tsarevitch drew his bow to shoot it. But the duck said to him:

"Do not kill me, good Tsarevitch. I certainly shall be useful to thee some day."

And this time he obeyed the command of the duck and passed by. Continuing his way he saw a blinking hare. The Tsarevitch prepared an arrow to shoot it, but the gray, blinking hare said:

"Do not kill me, brave Tsarevitch. I shall prove myself grateful to thee in a very short time."

The Tsarevitch did not shoot the hare, but passed by. He walked farther and farther after the rolling ball, and came to the deep blue sea. On the sand there lay a fish. I do not remember the name of the fish, but it was a big fish, almost dying on the dry sand.

"O Tsarevitch Ivan!" prayed the fish, "have mercy upon me and push me back into the cool sea."

The Tsarevitch did so, and walked along the shore. The ball, rolling all the time, brought Ivan to a hut, a queer, tiny hut standing on tiny hen's feet.

"Izboushka! Izboushka!"—for so in Russia do they name small huts—"Izboushka, I want thee to turn thy front to me," cried Ivan, and lo! the tiny hut turned its front at once. Ivan stepped in and saw a witch, one of the ugliest witches he could imagine.

"Ho! Ivan Tsarevitch! What brings thee here?" was his greeting from the witch.

"O, thou old mischief!" shouted Ivan with anger. "Is it the way in holy Russia to ask questions before the tired guest gets something to eat, something to drink, and some hot water to wash the dust off?"

Baba Yaga, the witch, gave the Tsarevitch plenty to eat and drink, besides hot water to wash the dust off. Tsarevitch Ivan felt refreshed. Soon he became talkative, and related the wonderful story of his marriage. He told how he had lost his dear wife, and that his only desire was to find her.

"I know all about it," answered the witch. "She is now at the palace of Kostshei the Deathless, and thou must understand that Kostshei is terrible. He watches her day and night and no one can ever conquer him. His death depends on a magic needle. That needle is within a hare; that hare is within a large trunk; that trunk is hidden in the branches of an old oak tree; and that oak tree is watched by Kostshei as closely as Vassilissa herself, which means closer than any treasure he has."

Then the witch told Ivan Tsarevitch how and where to find the oak tree. Ivan hastily went to the place. But when he perceived the oak tree he was much discouraged, not knowing what to do or how to begin the work. Lo and behold! that old acquaintance of his, the Russian bear, came running along, approached the tree, uprooted it, and the trunk fell and broke. A hare jumped out of the trunk and began to run fast; but another hare, Ivan's friend, came running after, caught it and tore it to pieces. Out of the hare there flew a duck, a gray one which flew very high and was almost invisible, but the beautiful white duck followed the bird and struck its gray enemy, which lost an egg. That egg fell into the deep sea. Ivan meanwhile was anxiously watching his faithful friends helping him. But when the egg disappeared in the blue waters he could not help weeping. All of a sudden a big fish came swimming up, the same fish he had saved, and brought the egg in his mouth. How happy Ivan was when he took it! He broke it and found the needle inside, the magic needle upon which everything depended.

At the same moment Kostshei lost his strength and power forever. Ivan Tsarevitch entered his vast dominions, killed him with the magic needle, and in one of the palaces found his own dear wife, his beautiful Vassilissa. He took her home and they were very happy ever after.

In an empire, in a country beyond many seas and

islands, beyond high mountains, beyond large rivers, upon a level

expanse, as if spread upon a table, there stood a large town, and

in that town there lived a Tsar called Archidei, the son of

Aggei; therefore he was called Aggeivitch.

In an empire, in a country beyond many seas and

islands, beyond high mountains, beyond large rivers, upon a level

expanse, as if spread upon a table, there stood a large town, and

in that town there lived a Tsar called Archidei, the son of

Aggei; therefore he was called Aggeivitch.

A famous Tsar he was, and a clever one. His wealth could not be counted; his warriors were innumerable. There were forty times forty towns in his kingdom, and in each one of these towns there were ten palaces with silver doors and golden ceilings and magnificent crystal windows.

For his council twelve wise men were selected, each one of them having a beard half a yard long and a head full of wisdom. These advisers offered nothing but truth to their father sovereign; none ever dared advance a lie.

How could such a Tsar be anything but happy? But it is true, indeed, that neither wealth nor wisdom give happiness when the heart is not at ease, and even in golden palaces the poor heart often aches.

So it was with the Tsar Archidei; he was rich and clever, besides being a handsome fellow; but he could not find a bride to his taste, a bride with wit and beauty equal to his own. And this was the cause of the Tsar Archidei's sorrow and distress.

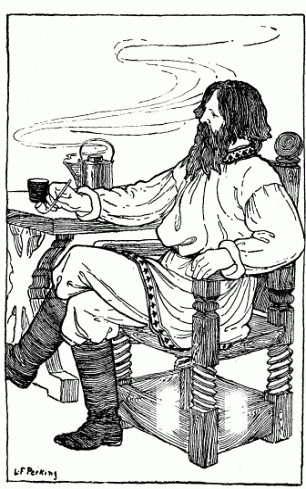

One day he was sitting in his golden armchair looking out of the window lost in thought. He had gazed for quite a while before he noticed foreign sailors landing opposite the imperial palace. The sailors ran their ship up to the wharf, reefed their white sails, threw the heavy anchor into the sea and prepared the plank ready to go ashore. Before them all walked an old merchant; white was his beard and he had about him the air of a wise man. An idea suddenly occurred to the Tsar: "Sea merchants generally are well informed on many subjects. If I ask them, perchance I shall find that they have met somewhere a princess, beautiful and clever, suitable for me, the Tsar Archidei."

Without delay the order was given to call the sea merchants into the halls of the palace.

The merchant guests appeared, prayed to the holy icons hanging in the corner, bowed to the Tsar, bowed to the wise advisers. The Tsar ordered his servants to serve them with tumblers of strong green wine. The guests drank the strong green wine and wiped their beards with embroidered towels. Then the Tsar Archidei addressed them:

"We are aware that you gallant sea merchants cross all the big waters and see many wonderful things. My desire is to ask you about something, and you must give a straightforward answer without any deceit or evasion."

"So be it, mighty Tsar Archidei Aggeivitch," answered the merchant guests, bowing.

"Well, then, can you tell me if somewhere in an empire or kingdom, or among great princes, there is a maiden as beautiful and wise as I myself, Tsar Archidei; an illustrious maiden who would be a proper wife for me, a suitable Tsaritza for my country?"

The merchant guests seemed to be puzzled, and after a long silence the eldest among them thus replied:

"Indeed, I once heard that yonder beyond the great sea, on an island called Buzan, there is a great country; and the sovereign of that land has a daughter named Helena, a princess very beautiful, not less so, I dare say, than thyself. And wise she is, too; a wise man once tried for three years to guess a riddle that she gave, and did not succeed."

"How far is that island, pray tell, and where are the roads that lead to it?"

"The island is not near," answered the old merchant. "If one chooses the wide sea he must journey ten years. Besides, the way to it is not known to us. Moreover, even suppose we did know the way, it seems that the Princess Helena is not a bride for thee."

The Tsar Archidei shouted with anger:

"How dost thou dare to speak such words, thou, a long-bearded buck?"

"Thy will be done, but think for thyself. Suppose thou shouldst send an envoy to the island of Buzan. He would require ten long years to go there, ten years equally long to come back, and so his journey would require fully twenty years. By that time a most beautiful princess would grow old—a girl's beauty is like the swallow, a bird of passage; it lasts not long."

The Tsar Archidei became thoughtful.

"Well," he said to the merchant guests, "you have my thanks, guests of passage, respectable men of trade. Go in God's name, transact business in my tsarstvo without any taxes whatever. What to do about the beautiful Princess Helena I will try to think out by myself."

The merchants bowed low and left the Tsar's rich palace.

The Tsar Archidei sat still, wrapped in thought, but he could find neither beginning nor end to the problem. "Let me ride into the wide fields," he said; "let me forget my sorrow amid the excitement of the noble hunt, hoping that the future may bring advice."

The falconers appeared, cheerful notes from the golden trumpets resounded, and falcons and hawks were soon slumbering under their velvet caps as they sat quietly on the fingers of the hunters.

The Tsar Archidei Aggeivitch came with his men to a wide, wide field. All of his men were watching the moment to loose their falcons in order to let the birds pursue a long-legged heron or a white-breasted swan.

Now, you, my listeners, must understand that the fairy tale is quick, but life is not. The Tsar Archidei was on horseback for a long while, and finally came to a green valley. Looking around he saw a well cultivated field where the golden ears of the grain were already ripe, and oh, how beautiful! The Tsar stopped in admiration.

"I presume," he exclaimed, "that good workers are owners of this place, honest plowmen and diligent sowers. If only all fields in my tsarstvo were equally cultivated, my people need never know what hunger means, and there would even be plenty to send beyond the sea to be exchanged for silver and gold."

Then the Tsar Archidei gave orders to inquire who the owners of the field were, and what were their names. Hunters, grooms, and servants rushed in all directions, and discovered seven brave fellows, all of them fair, red-cheeked, and very handsome. They were dining according to the peasant fashion, which means that they were eating rye bread with onions, and drinking clear water. Their blouses were red, with a golden galloon around the neck, and they were so much alike that one could hardly be recognized from another.

The royal messengers approached.

"Whose field is this?" they asked; "this field with golden wheat?"

The seven brave peasants answered cheerfully:

"This is our field; we plowed it, and we also have sown the golden wheat."

"And what kind of people are you?"

"We are the Tsar Archidei Aggeivitch's peasants, farmers, and we are brothers, sons of one father and mother. The name for all of us is Simeon, so you understand we are seven Simeons."

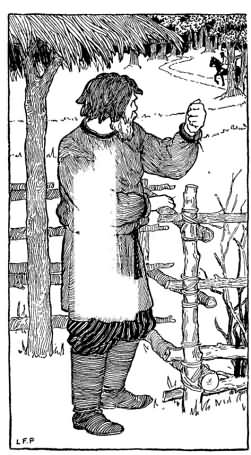

"Hunters, grooms, and servants rushed in all directions"

This answer was faithfully delivered to the Tsar Archidei by the envoys, and the Tsar at once desired to see the brave peasants, and ordered them to be called before him. The seven Simeons presently appeared and bowed. The Tsar looked at them with his bright eyes and asked them:

"What kind of people are you whose field is so well cultivated?"

One of the seven brothers, the eldest of them, answered:

"We are all thy peasants, simpletons, without any wisdom, born of peasant parents, all of us children of the same father and the same mother, and all having the same name, Simeon. Our old father taught us to pray to God, to obey thee, to pay taxes faithfully, and besides to work and toil without rest. He also taught to each of us a trade, for the old saying is, 'A trade is no burden, but a profit.' The old father wished us to keep our trades for a cloudy day, but never to forsake our own fields, and always to be contented, and plow and harrow diligently.

"He also used to say, 'If one does not neglect the mother earth, but thoroughly harrows and sows in due season, then she, our mother, will reward generously, and will give plenty of bread, besides preparing a soft place for the everlasting rest when one is old and tired of life.'"

The Tsar Archidei liked the simple answer of the peasant, and said:

"Take my praise, brave good fellows, my peasants, tillers of the soil, sowers of wheat, gatherers of gold. And now tell me, what trades did your father teach you, and what do you know?"

The first Simeon answered:

"My trade is not a very wise one. If thou wouldst let me have materials and working men, then I could build a post, a white stone column, reaching beyond the clouds, almost to the sky."

"Good enough!" exclaimed the Tsar Archidei. "And thou, the second Simeon, what is thy trade?"

The second Simeon was quick to give answer:

"My trade is a simple one. If my brother will build a white stone column, I can climb upon that column high up in the sky, and I shall see from above all the empires and all the kingdoms under the sun, and everything which is going on in those foreign countries."

"Thy trade is not so bad either," and the Tsar smiled and looked at the third brother. "And thou, third Simeon, what trade is thine?"

The third Simeon also had his answer ready:

"My trade is simple, too; that is to say, a peasant's trade. If thou art in need of ships, thy learned men of foreign birth build them for thee as well as their wisdom teaches them. But if thou wilt order, I will build them simply—one, two! and the ship is ready. My ships will be the result of the quick headwork of a peasant simpleton. But where a foreign ship sails a year, mine will sail an hour, and where others take ten years, mine will take not longer than a week."

"Well, well!" laughed the Tsar. "And thy trade, the fourth Simeon?" he asked.

The fourth brother bowed.

"My trade needs no wisdom either. If my brother will build thee a ship, I then will sail that ship; and if an enemy gives chase or a tempest rises, I'll seize the ship by the black prow and plunge her into the deep waters where there is eternal quiet; and after the storm is over or the enemy far, I'll again guide her to the surface of the wide sea."

"Good!" approved the Tsar. "And thou, fifth Simeon, what dost thou know? Hast thou also a trade?"

"My trade, Tsar Archidei Aggeivitch, is not a fair one, for I am a blacksmith. If thou wouldst order a shop built for me, I at once would forge a self-shooting gun, and no eagle far above in the sky or wild beast in the wood would be safe from that gun."

"Not bad either," answered the Tsar Archidei, well pleased. "Thy turn now, sixth Simeon."

"My trade is no trade," answered the sixth Simeon, rather humbly. "If my brother shoots a bird or a beast, never mind what or where, I can catch it before it falls down, catch it even better than a hunting dog. If the prey should fall into the blue sea, I'll find it at the sea's bottom; should it fall into the depth of the dark woods, I'll find it there in the midst of night; should it get caught in a cloud, I'll find it even there."

The Tsar Archidei evidently liked the trade of the sixth Simeon very well also. These were all simple trades, you see, without any wisdom whatever, but rather entertaining. The Tsar also liked the peasants' speech, and he said to them:

"Thanks, my peasants, tillers of the soil, my faithful workers. Your father's words are true ones: 'A trade is not a burden, but a profit.' Now come to my capital for a trial; people like you are welcome. And when the season for harvest arrives, the time to reap, to bind in bundles the golden grain, to thresh and carry the wheat to the market, I will let you go home with my royal grace."

Then all the seven Simeons bowed very low. "Thine is the will," said they, "and we are thy obedient subjects."

Here the Tsar Archidei looked at the youngest Simeon and remembered that he had not asked him about his trade. So he said:

"And thou, seventh Simeon, what is thy trade?"

"I have none, Tsar Archidei Aggeivitch. I learned many, but not a single one did me any good, and though I know something very well, I am not sure your majesty would like it."

"Let us know thy secret," ordered the Tsar Archidei.

"No, Tsar Archidei Aggeivitch! Give me, first of all, thy royal word not to kill me for my inborn talent, but to have mercy upon me. Then only will I be willing to disclose my secret."

"Thy wish is granted. I give thee my royal word, true and not to be broken, that whatever thou shalt disclose to me, I will have mercy upon thee."

Hearing these kind words, the seventh Simeon smiled, looked around, shook his curls and began:

"My trade is one for which there is no mercy in thy tsarstvo, and it is the one thing I am able to do. My trade is to steal and to hide the trace of how and when. There is no treasure, no fortunate possession, not even a bewitched one, nor a secret place that could be forbidden me if it be my wish to steal."

As soon as these bold words of the seventh Simeon reached the Tsar's ears he became very angry.

"No!" he exclaimed, "I certainly shall not pardon thee, thief and burglar! I will give orders for thy cruel death! I will have thee chained and thrown into my subterranean prison with nothing but bread and water for food until thou forget thy trade!"

"Great and merciful Tsar Archidei Aggeivitch, postpone thy orders. Listen to my peasant talk," prayed the seventh Simeon. "Our old Russian saying is: 'He is no thief who is not caught, and neither is he who steals, but the one who instigates the theft.' If my wish had been to steal, I should have done it long ago. I should have stolen thy treasures and thy judges would not have objected to take a small share of them, and I could have built a white-walled stone palace and have been rich. But, mark this: I am a stupid peasant of low origin. I know well enough how to steal, but will not. If thy wish were to learn my trade, how could I keep it from thee? And if thou, for this sincere acknowledgment, wilt have me put to death, then what is the value of thy royal word?"

The Tsar thought a moment. "For this time," he said, "I will not let thee die, for it pleases me to grant thee my grace. But from this very day, this very hour, thou never shalt see God's light nor the bright sunshine nor the silvery moon. Thou shalt never walk at liberty through the wide fields, but thou, my dear guest, shalt dwell in a palace where no sunny ray ever penetrates. You, my servants, take him, chain his hands and his feet and lead him to my chief jailor. And you six Simeons follow me. You have my grace and reward. To-morrow every one of you will begin to work for me according to his gifts and capacities."

The six Simeons followed the Tsar Archidei, and the seventh brother, the youngest, the beloved one, was fallen upon by the servants, taken away to the dark prison and heavily chained.

The Tsar Archidei ordered carpenters to be sent to the first Simeon, as well as masons and blacksmiths and all sorts of workingmen. He also ordered a supply of bricks, stones, iron, clay, and cement. Without any delay, Simeon, the first brother, began to build a column, and according to his simple peasant's habits his work progressed rapidly, and not a moment was wasted in clever combinations. In a short time the white column was ready, and lo, how high it went! as high as the great planets. The smaller stars were beneath it, and from above the people seemed to be like bugs.

The second Simeon climbed the column, looked around, listened to all sounds, and came down. The Tsar Archidei, anxious to know about everything under the sun, ordered him to report, and Simeon did so. He told the Tsar Archidei all the wonderful doings all over the world. He told how one king was fighting another, where there was war and where there was peace, and with other things the second Simeon even mentioned deep secrets, quite surprising secrets, which made the Tsar Archidei smile; and the courtiers, encouraged by the royal smile, roared with laughter.

Meantime the third Simeon was accomplishing something in his line. After crossing himself three times the fellow rolled up his sleeves to the elbow, took a hatchet and—one, two—without any haste built a vessel. What a curious vessel it was! The Tsar Archidei watched the wonderful structure from the shore and as soon as the orders were given for sailing, the new vessel sailed away like a white-winged hawk. The cannon were shooting and upon the masts, instead of rigging, were drawn strings upon which musicians were playing the national tunes.

As soon as the wonderful vessel sailed into deep water, the fourth Simeon snatched the prow and no trace of it remained on the surface; the whole vessel went to the depths like a heavy stone. In an hour or so Simeon, with his left hand, led the ship to the blue surface of the sea again, and with his right he presented to the Tsar a most magnificent sturgeon for his "kulibiaka," the famous Russian fish pie.

While the Tsar Archidei enjoyed himself with looking at the marvelous vessel, the fifth Simeon built a blacksmith shop in the court back of the palace. There he blew the bellows and heated the iron. The noise from his hammers was great and the result of his peasant work was a self-shooting gun. The Tsar Archidei Aggeivitch went to the wild fields and perceived high above him, very high under the sky, an eagle flying.

"Now!" exclaimed the Tsar, "there is an eagle forgetting himself with watching the sun; shoot it. Perchance thou shalt have the good luck to hit it. Then I will honor thee."

Simeon shook his locks, smiled, put into his gun a silver bullet, aimed, shot, and the eagle fell swiftly to the earth. The sixth Simeon did not even allow the eagle to fall to the ground, but, quick as a flash, he ran under it with a plate, caught it on that big plate and presented his prey to the Tsar Archidei.

"Thanks, thanks, my brave fellows, faithful peasants, tillers of the soil!" exclaimed the Tsar Archidei gayly. "I see now plainly that all of you are men of trade and I wish to reward you. But now go to your dinner and rest awhile." The six Simeons bowed to the Tsar very low, prayed to the holy icons and went. They were already seated, had time to swallow each one a tumbler of the strong, green wine, took up the round wooden spoons in order to attack the "stchi," the Russian cabbage soup, when lo! the Tsar's fool came running and shaking his striped cap with the round bells and shouted:

"You ignorant simpletons, unlearned peasants, moujiks! Is it a suitable moment for dinner when the Tsar wants you? Go in haste!"

All the six started running toward the palace, thinking within themselves: "What can have happened?" In front of the palace stood the guards with their iron staves; in the halls all the wise and learned people were gathered together, and the Tsar himself was sitting on his high throne looking very grim and thoughtful.

"Listen to me," he said when the peasants approached, "you, my brave fellows, my clever brothers Simeon. I like your trades and I think, as do my wise advisers, that if thou, the second Simeon, art able to see everything going on under the sun, thou shouldst climb quickly on yonder column and glance around to see if there is, as they say, beyond the great sea an island, Buzan by name. And see if on that island, as men assert, there is a mighty kingdom, and in that kingdom a mighty king, and if that king, as the story goes, has a daughter, the most beautiful princess Helena."

The second Simeon bowed and ran quickly, even forgetting to put on his cap. He went straight to the column, climbed it, looked around, came down, and this was his report:

"Tsar Archidei Aggeivitch, I have accomplished thy sovereign wish. I looked far beyond the sea and have seen the island Buzan. Mighty is the king there, and he is proud and merciless. He sits within his palace and his speech is always the same:

'I am a great king and I have a most beautiful daughter, the princess Helena. There is no one in the universe more beautiful and more wise than she; there is no bridegroom worthy of her in any place under the bright sun, no tsar, no king, no tsarevitch, no korolevitch. To no one will I ever give my daughter, the princess Helena, and whoever shall dare to court her, on such an one will I declare war, ruin his country, and capture himself.'"

"And how great is the army of that king?" asked the Tsar Archidei; "and also how far is his kingdom from my tsarstvo?"

"Well, according to the measure of my eyes," answered Simeon, "I fancy it would take a ship ten years less two days; or, if it happened to be stormy, I am afraid even a little longer than ten years. And that king has not a small army. I have seen altogether a hundred thousand spearmen, a hundred thousand armed men, and a hundred thousand or more could be gathered from the Tsar's court, from his servants and all kinds of underlings. Besides, there is no small armament of guards held in reserve for a special occasion, fed and petted by the king."

The Tsar Archidei remained for a long time in thoughtful silence and finally addressed his court people:

"My warriors and advisers: I have but one wish; I want the princess Helena for my wife. But tell me, how can I reach her?"

The wise advisers remained silent, hiding themselves behind each other. The third Simeon looked around, bowed to the Tsar, and said:

"Tsar Archidei Aggeivitch, forgive my simple words. How to reach the island of Buzan there is no need to worry about. Sit down on my ship; she is simply built, and equipped without any wise tricks. Where others require a year she takes but a day, and where other ships take ten years mine will take, let us say, a week. Only order thine advisers to decide whether we ought to fight for or peacefully court the beautiful princess."

"Now, my warriors brave, my advisers sage," spoke the Tsar Archidei to his men, "How will you decide upon this matter? Who among you will go to fight for the princess, or who will be shrewd enough to bring her peacefully here? I will pour gold and silver over that one. I will give to him the first rank among the very first."

And again the brave warriors and the sage advisers remained silent. The Tsar grew angry; he seemed to be ready for a terrible word. Then, as if somebody had asked the fool, out he jumped from behind the wise people with his foolish talk, shook his striped fool's cap, rang his many bells, and shouted:

"Why so silent, wise men? why so deep in thought? You have big heads and long beards; it would seem that there is plenty of wisdom, so why not show it? To go to the island of Buzan to obtain the bride does not mean to lose gold or army. Have you already forgotten the seventh Simeon? Why, it will be simple enough for him to steal the princess Helena. Afterwards let the king of Buzan come here to fight us, and we will welcome him as an honored guest. But do not forget that he must take ten years' time to reach us, and in ten years—ah me! I have heard that some wise man somewhere undertook to teach a horse to talk in ten years!"

"Good! Good!" exclaimed the Tsar Archidei, forgetting even his anger. "I thank thee, striped fool. I certainly shall reward thee. Thou must have a new cap with noisy bells, and each one of thy children a ginger pancake. You, faithful servants, run quickly and bring here the seventh Simeon."

According to the Tsar's bidding the heavy iron gates of the dark prison were thrown open, the heavy chains were taken off and the seventh Simeon appeared before the eager eyes of the Tsar Archidei, who thus addressed him:

"Listen to me attentively, thou seventh Simeon, for I had almost decided to grant thee a high honor; to keep thee thy life long in my prison. But if thou shouldst prove useful to me, then will I give thee freedom; and besides, thou shalt have a share out of my treasures. Art thou able to steal the beautiful princess Helena from her father, the mighty king of the island of Buzan?"

"And why not?" cheerfully laughed the seventh Simeon. "There is nothing difficult about it. She is not a pearl, and I presume she is not under too many locks. Only order the ship which my brother had built for thee to be loaded with velvets and brocades, with Persian rugs, beautiful pearls and precious stones, and bid my four brothers come along with me. But the two eldest keep thou as hostages."

Once said, quickly done. The Tsar Archidei gave orders while all were running hither and thither, and everything was finished so promptly that a short-haired girl would scarcely have had time to plait her hair. The ship, laden with velvets, brocades, with Persian rugs and pearls, and costly precious stones, was ready; the five brothers, the brave Simeons, were ready; they bowed to the Tsar, spread sail, and disappeared.

The ship floated swiftly over the blue waters; she flew like a hawk in comparison with the slow merchant vessels, and in a week after the five Simeons had left their native land they sighted the island of Buzan.

The island appeared to be surrounded with cannon as thick as peas; the gigantic guards walked up and down the shores tugging fiercely at their big mustaches. As soon as the ship became visible from a tower somebody shouted through a Dutch trumpet:

"Stop! Answer! What kind of people are ye? Why come ye here?"

The seventh Simeon answered from the ship: "We are a peaceful people, not enemies but friends, merchants everywhere welcomed as guests. We bring foreign merchandise. We want to sell, to buy, and to exchange. We also have gifts for your king and for the korolevna."

The five brothers, our brave Simeons, lowered the boat, loaded it with choice Venetian velvets, brocades, pearls, and precious stones, and covered all with Persian rugs. They rowed to the wharf, and landing near the king's palace, at once carried their gifts to the king.

The beautiful korolevna Helena was sitting in her terem. She was a fair maiden with eyes like stars and eyebrows like precious sable. When she looked at one it was like receiving a gift, and when she walked it was like the graceful swimming of a swan. The korolevna was quick to notice the brave, handsome brothers and at once called her nurses and maidens.

"Hasten, my dear nurses, and you, swift maidens, find out what kind of strangers are these coming to our royal palace."

All of the nurses, all of the maidens, ran out with questions ready. The seventh Simeon answered them thus:

"We are merchant guests, peaceful people. Our native land is the country of the Tsar Archidei Aggeivitch, a great Tsar indeed. We came to sell, to buy, to exchange; moreover, we have gifts for the king and his princess. We do hope the king will favor us and will accept these trifles; if not for himself, at least for the adornment of his court's lovely maidens."

When Helena heard these words she at once let the merchants in. And the merchants appeared, bowed low to the beautiful korolevna, unfolded the showy velvets and golden brocades, strewed around the pearls and precious stones, such stones and pearls as had never been seen before in Buzan. The nurses and the maidens opened their mouths in amazement, and the korolevna herself seemed to be greatly pleased. The seventh Simeon, quick to understand, smiled and said:

"We all know thee to be as wise as beautiful, but now thou art evidently joking about us or mocking us. These simple wares are altogether too plain for thine own use. Accept them for thy nurses and maidens for their everyday attire, and these stones send away to the kitchen boys to play with. But if thou wilt listen to me, let me say that on our ship we have very different velvets and brocades; we have also precious stones, far more precious than any one has ever seen; yet we dared not bring them at once lest we might not suit thy temper and thy hearty wish. If thou shouldst decide to come in person and choose anything from among our possessions, they all are thine and we bow to thee gratefully for the bright glance of thy beautiful eyes."

The royal maid liked well enough these polite words of the handsome Simeon, and to her father she went:

"Father and king, there have come to visit us some foreign merchants and they have brought some goods never before seen in Buzan. Give me thy permission to go on board their wonderful ship to choose what things I like. They also have rich gifts for thee."

The king hesitated before answering her, frowning and scratching behind his ear.

"Well," he said at last, "be it according to thy wish, my daughter, my beautiful korolevna. And you, my counselors, order my royal vessel to be ready, the cannons loaded, and a hundred of my bravest warriors detailed to escort the vessel. Send besides a thousand heavy armed warriors to guard the korolevna on her way to the merchants' vessel."

Then the king's vessel started from the island of Buzan. Numbers of cannon and warriors protected the princess, and the royal father remained quiet at home.

When they reached the merchants' ship the korolevna Helena came down, and at once the crystal bridge was placed and the korolevna with all her nurses and maidens went on board the foreign ship, such a ship as they had never seen before, never even dreamed of. Meanwhile the guards kept watch.

The seventh Simeon showed the lovely guests everywhere. He was talking smoothly while leisurely unfolding his precious goods. The korolevna listened attentively, looked around curiously, and seemed well pleased.

At the same moment the fourth Simeon, watching the proper moment, snapped the prow and down to mysterious depths went the ship where no one could see her. The people on the king's vessel screamed in terror, the warriors looked like drunken fools, and the guards only opened their eyes wider than before. What should they do? They directed the vessel back to the island and appeared before the king with their terrible tale.

"Oh, my daughter, my darling princess Helena! It is God who punishes me for my pride. I never wanted thee to marry. No king, no prince, would I consider worthy of thee; and now—oh! now I know that thou art wedded to the deep sea! As for me, I am left alone for the rest of my sorrowful days."

Then all at once he looked around and shouted to his men:

"You fools! what were you thinking about? You shall all lose your heads! Guards, throw them into dungeons! The most cruel death shall be theirs, such a death that the children of their great-grandchildren shall shiver to hear the tale!"

Now, while the king of Buzan raved and grieved, the ship of the brothers Simeon, like a golden fish, swam under the blue waters, and when the island was lost from sight the fourth Simeon brought her to the surface and she rose upon the waters like a white-winged gull. By this time the princess was becoming anxious about the long time they were away from home, and she exclaimed:

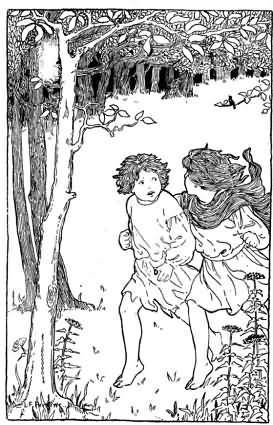

"Nurses and maidens, we are leisurely looking around, but I fancy my father the king finds the time sadly long." She hastily walked to the deck of the ship, and behold!—only the wide sea was around her like a mirror! Where was her native island, where the royal vessel? There was nothing visible but the blue sea. The princess screamed, struck her white bosom with both hands, transformed herself into a white swan and flew high into the sky. But the fifth Simeon, watching closely, lost no time, snapped his lucky gun and the white swan was shot. His brother, the sixth Simeon, caught the white swan, but lo! instead of the white swan there was a silvery fish, which slipped away from him. Simeon caught the fish, but the pretty, silvery fish turned into a small mouse running around the ship. Simeon did not let it reach a hole, but swifter than a cat caught the mouse,—and the princess Helena, as beautiful and natural as before, appeared before them, fair-faced, bright-eyed.

On a lovely morning a week later the Tsar Archidei was sitting by the window of his palace lost in thought. His eyes were turned toward the sea, the wide, blue sea. He was sad at heart and could not eat; feasts had no interest for him, the costly dishes had no taste, the honey drink seemed weak. All his thoughts and longings were for the princess Helena, the beautiful one, the only one.

What is that far away upon the waters? Is it a white gull? Or are those white wings not wings, but sails? No, it is not a gull, but the ship of the brothers Simeon, and she approaches as rapidly as the wind which blows her sails. The cannon boom, native melodies are played on the cords of the masts. Soon the ship is anchored, the crystal bridge prepared, and the korolevna Helena, the beautiful princess, appears like a never-setting sun, her eyes like bright stars, and oh! how happy is the Tsar Archidei!

"Run quick, my faithful servants, you brave officers of state, and you, too, my bodyguard, and all you useful and ornamental fellows of my palace, run and prepare, shoot off rockets and ring the bells in order to give a joyful welcome to korolevna Helena, the beautiful."

All hastened to their tasks, to shoot, to ring the bells, to open the gates, to honorably receive the korolevna. The Tsar himself came out to meet the beautiful princess, took her white hands and helped her into the palace.

"Welcome! welcome!" said the Tsar Archidei. "Thy fame, korolevna Helena, reached me, but never could I imagine such beauty as is thine. Yet, though I admire thee, I do not want to separate thee from thy father. Say the word and my faithful servants will take thee back to him. If thou choosest, however, to remain in my tzarstvo, be the tsaritza over my country and rule over me, the Tzar Archidei, also."

At these words of the Tsar the korolevna Helena threw such a glance at the Tsar that it seemed to him the sun was laughing, the moon singing, and the stars dancing all around.

Well, what more is there to be said? You certainly can imagine the rest. The courtship was not long and the wedding feast was soon ready, for you know kings always have everything at their command. The brothers Simeon were at once dispatched to the king of Buzan with a message from the korolevna, his daughter, and this is what she wrote:

"Dear father, mighty king and sovereign: I have found a husband according to my heart's wish and I am asking thy fatherly blessing. My bridegroom, the Tsar Archidei Aggeivitch, sends his counselors to thee, begging thee to come to our wedding."

At the very moment when the merchant ship was to land at the island of Buzan, crowds of people had gathered to witness the execution of the unfortunate guards and brave warriors whose ill-luck it was to have allowed the princess to disappear.

"Stop!" Simeon the seventh shouted aloud from the deck. "We bring a missive from the korolevna Helena. Holla!"

Very glad indeed was the king of the island of Buzan, and glad were all his subjects. The missive was read and the condemned were pardoned.

"Evidently," the king said, "it is fated that the handsome and witty Tsar Archidei and my beautiful daughter are to become husband and wife."

Then the king treated the envoys and the brothers Simeon very well and sent his blessings with them, as he himself did not wish to go, being very old. The ship soon returned and the Tsar Archidei rejoiced over it with his beautiful bride, and at once summoned the seven Simeons, the seven brave peasants.

He said to them: "Thanks! thanks! my peasants, my brave tillers of the soil. Take as much gold as you wish. Take silver also and ask for whatever is your heart's desire. Everything shall be given you with my mighty hand. Would you like to become boyars, you shall be the greatest among the very great. Do you choose to become governors, each one shall have a town."

The first Simeon bowed to the Tsar and cheerfully answered:

"Thanks also to thee, Tsar Archidei Aggeivitch. We are but simple people and simple are our ways. It would not do for us to become boyars or governors. We do not care for thy treasures either. We have our own father's field, which shall always give us bread for hunger and money for need. Let us go home, taking with us thy gracious word as our reward. If thou choosest to be so kind, give us thine order which shall save us from the judges and tax-gatherers; and if we should be guilty of some offense, let thyself alone be our judge. And do, we pray thee, pardon the seventh Simeon, our youngest brother. His trade is surely bad, but he is not the first and not the last one to have such a gift."

"Let it be as you wish," said the Tsar; and every desire was granted to the seven Simeons, and each one of them received a big tumbler of strong green wine out of the hands of the Tsar himself. Soon after this the wedding was celebrated.

Now, honorable dames and gentlemen, do not judge this story of mine too severely. If you like it, praise it; if not, let it be forgotten. The story is told and a word is like a sparrow—once out it is out for good.

Somewhere in a town in holy Russia, there lived a rich merchant with his wife. He had an only son, a dear, bright, and brave boy called Ivan. One lovely day Ivan sat at the dinner table with his parents. Near the window in the same room hung a cage, and a nightingale, a sweet-voiced, gray bird, was imprisoned within. The sweet nightingale began to sing its wonderful song with trills and high silvery tones. The merchant listened and listened to the song and said:

"How I wish I could understand the meaning of the different songs of all the birds! I would give half my wealth to the man, if only there were such a man, who could make plain to me all the different songs of the different birds."

Ivan took notice of these words and no matter where he went, no matter where he was, no matter what he did, he always thought of how he could learn the language of the birds.

Ivan learns the language of the birds

Some time after this the merchant's son happened to be hunting in a forest. The winds rose, the sky became clouded, the lightning flashed, the thunder roared loudly, and the rain fell in torrents. Ivan soon came near a large tree and saw a big nest in the branches. Four small birds were in the nest; they were quite alone, and neither father nor mother was there to protect them from the cold and wet. The good Ivan pitied them, climbed the tree and covered the little ones with his "kaftan," a long-skirted coat which the Russian peasants and merchants usually wear. The thunderstorm passed by and a big bird came flying and sat down on a branch near the nest and spoke very kindly to Ivan.

"Ivan, I thank thee; thou hast protected my little children from the cold and rain and I wish to do something for thee. Tell me what thou dost wish."

Ivan answered; "I am not in need; I have everything for my comfort. But teach me the birds' language."

"Stay with me three days and thou shalt know all about it."

Ivan remained in the forest three days. He understood well the teaching of the big bird and returned home more clever than before. One beautiful day soon after this Ivan sat with his parents when the nightingale was singing in his cage. His song was so sad, however, so very sad, that the merchant and his wife also became sad, and their son, their good Ivan, who listened very attentively, was even more affected, and the tears came running down his cheeks.

"What is the matter?" asked his parents; "what art thou weeping about, dear son?"

"Dear parents," answered the son, "it is because I understand the meaning of the nightingale's song, and because this meaning is so sad for all of us."

"What then is the meaning? Tell us the whole truth; do not hide it from us," said the father and mother.

"Oh, how sad it sounds!" replied the son. "How much better would it be never to have been born!"

"Do not frighten us," said the parents, alarmed. "If thou dost really understand the meaning of the song, tell us at once."

"Do you not hear for yourselves? The nightingale says: 'The time will come when Ivan, the merchant's son, shall become Ivan, the king's son, and his own father shall serve him as a simple servant.'"

The merchant and his wife felt troubled and began to distrust their son, their good Ivan. So one night they gave him a drowsy drink, and when he had fallen asleep they took him to a boat on the wide sea, spread the white sails, and pushed the boat from the shore.

For a long time the boat danced on the waves and finally it came near a large merchant vessel, which struck against it with such a shock that Ivan awoke. The crew on the large vessel saw Ivan and pitied him. So they decided to take him along with them and did so. High, very high, above in the sky they perceived cranes. Ivan said to the sailors:

"Be careful; I hear the birds predicting a storm. Let us enter a harbor or we shall suffer great danger and damage. All the sails will be torn and all the masts will be broken."

But no one paid any attention and they went farther on. In a short time the storm arose, the wind tore the vessel almost to pieces, and they had a very hard time to repair all the damage. When they were through with their work they heard many wild swans flying above them and talking very loud among themselves.

"What are they talking about?" inquired the men, this time with interest.

"Be careful," advised Ivan. "I hear and distinctly understand them to say that the pirates, the terrible sea robbers, are near. If we do not enter a harbor at once they will imprison and kill us."

The crew quickly obeyed this advice and as soon as the vessel entered the harbor the pirate boats passed by and the merchants saw them capture several unprepared vessels. When the danger was over, the sailors with Ivan went farther, still farther. Finally the vessel anchored near a town, large and unknown to the merchants. A king ruled in that town who was very much annoyed by three black crows. These three crows were all the time perching near the window of the king's chamber. No one knew how to get rid of them and no one could kill them. The king ordered notices to be placed at all crossings and on all prominent buildings, saying that whoever was able to relieve the king from the noisy birds would be rewarded by obtaining the youngest korolevna, the king's daughter, for a wife; but the one who should have the daring to undertake but not succeed in delivering the palace from the crows would have his head cut off. Ivan attentively read the announcement, once, twice, and once more. Finally he made the sign of the cross and went to the palace. He said to the servants:

"Open the window and let me listen to the birds."

The servants obeyed and Ivan listened for a while. Then he said:

"Show me to your sovereign king."

When he reached the room where the king sat on a high, rich chair, he bowed and said:

"There are three crows, a father crow, a mother crow, and a son crow. The trouble is that they desire to obtain thy royal decision as to whether the son crow must follow his father crow or his mother crow."

The king answered: "The son crow must follow the father crow."

As soon as the king announced his royal decision the crow father with the crow son went one way and the crow mother disappeared the other way, and no one has heard the noisy birds since. The king gave one-half of his kingdom and his youngest korolevna to Ivan, and a happy life began for him.

In the meantime his father, the rich merchant, lost his wife and by and by his fortune also. There was no one left to take care of him, and the old man went begging under the windows of charitable people. He went from one window to another, from one village to another, from one town to another, and one bright day he came to the palace where Ivan lived, begging humbly for charity. Ivan saw him and recognized him, ordered him to come inside, and gave him food to eat and also supplied him with good clothes, asking questions:

"The old man went begging from town to town"

"Dear old man, what can I do for thee?" he said.

"If thou art so very good," answered the poor father, without knowing that he was speaking to his own son, "let me remain here and serve thee among thy faithful servants."

"Dear, dear father!" exclaimed Ivan, "thou didst doubt the true song of the nightingale, and now thou seest that our fate was to meet according to the predictions of long ago."

The old man was frightened and knelt before his son, but his Ivan remained the same good son as before, took his father lovingly into his arms, and together they wept over their sorrow.

Several days passed by and the old father felt courage to ask his son, the korolevitch:

"Tell me, my son, how was it that thou didst not perish in the boat?"

Ivan Korolevitch laughed gayly.

"I presume," he answered, "that it was not my fate to perish at the bottom of the wide sea, but my fate was to marry the korolevna, my beautiful wife, and to sweeten the old age of my dear father."

In one of the suburbs there was a poor hut where an old man lived with his three sons, Thomas, Pakhom, and Ivan. The old man was not only clever, he was wise. He had happened once to have a chat with the devil. They talked together while the old man treated him to a tumbler of wine and got out of the devil many great secrets. Soon after this the peasant began to perform such marvelous acts that the neighbors called him a sorcerer, a magician, and even supposed that the devil was his kin.

Yes, it is true that the old man performed great marvels. Were you longing for love, go to him, bow to the old man, and he would give you some strange root, and the sweetheart would be yours. If there is a theft, again to him with the tale. The old man conjures over some water, takes an officer along straight to the thief, and your lost is found; only take care that the officer steals it not.

Indeed the old man was very wise; but his children were not his equals. Two of them were almost as clever. They were married and had children, but Ivan, the youngest, was single. No one cared much for him because he was rather a fool, could not count one, two, three, and only drank, or ate, or slept, or lay around. Why care for such a person? Every one knows life for some is brighter than for others. But Ivan was good-hearted and quiet. Ask of him a belt, he will give a kaftan also; take his mittens, he certainly would want to have you take his cap with them. And that is why all liked Ivan, and usually called him Ivanoushka the Simpleton; though the name means fool, at the same time it carries the idea of a kind heart.

Our old man lived on with his sons until finally his hour came to die. He called his three sons and said to them:

"Dear children of mine, my dying hour is at hand and ye must fulfill my will. Every one of you come to my grave and spend one night with me; thou, Tom, the first night; thou, Pakhom, the second night; and thou, Ivanoushka the Simpleton, the third."

Two of the brothers, as clever people, promised their father to do according to his bidding, but the Simpleton did not even promise; he only scratched his head.

The old man died and was buried. During the celebration the family and guests had plenty of pancakes to eat and plenty of whisky to wash them down.

Now you remember that on the first night Thomas was to go to the grave; but he was too lazy, or possibly afraid, so he said to the Simpleton:

"I must be up very early to-morrow morning; I have to thresh; go thou for me to our father's grave."

"All right," answered Ivanoushka the Simpleton. He took a slice of black rye bread, went to the grave, stretched himself out, and soon began to snore.

The church clock struck midnight; the wind roared, the owl cried in the trees, the grave opened and the old man came out and asked:

"Who is there?"

"I," answered Ivanoushka.

"Well, my dear son, I will reward thee for thine obedience," said the father.

Lo! the cocks crowed and the old man dropped into the grave. The Simpleton arrived home and went to the warm stove.

"What happened?" asked the brothers.

"Nothing," he answered. "I slept the whole night and am hungry now."

The second night it was Pakhom's turn to go to his father's grave. He thought it over and said to the Simpleton:

"To-morrow is a busy day with me. Go in my place to our father's grave."

"All right," answered Ivanoushka. He took along with him a piece of fish pie, went to the grave and slept. Midnight approached, the wind roared, crows came flying, the grave opened and the old man came out.

"Who is there?" he asked.

"I," answered his son the Simpleton.

"Well, my beloved son, I will not forget thine obedience," said the old man.

The cocks crowed and the old man dropped into his grave. Ivanoushka the Simpleton came home, went to sleep on the warm stove, and in the morning his brothers asked:

"What happened?"

"Nothing," answered Ivanoushka.

On the third night the brothers said to Ivan the Simpleton:

"It is thy turn to go to the grave of our father. The father's will should be done."

"All right," answered Ivanoushka. He took some cookies, put on his sheepskin, and arrived at the grave.

At midnight his father came out.

"Who is there?" he asked.

"I," answered Ivanoushka.

"Well," said the old father, "my obedient son, thou shalt be rewarded;" and the old man shouted with a mighty voice:

"Arise, bay horse—thou wind-swift steed,

Appear before me in my need;

Stand up as in the storm the weed!"

And lo!—Ivanoushka the Simpleton beheld a horse running, the earth trembling under his hoofs, his eyes like stars, and out of his mouth and ears smoke coming in a cloud. The horse approached and stood before the old man.

"What is thy wish?" he asked with a man's voice.

The old man crawled into his left ear, washed and adorned himself, and jumped out of his right ear as a young, brave fellow never seen before.

"Now listen attentively," he said. "To thee, my son, I give this horse. And thou, my faithful horse and friend, serve my son as thou hast served me."

Hardly had the old man pronounced these words when the first cock crew and the sorcerer dropped into his grave. Our Simpleton went quietly back home, stretched himself under the icons, and his snoring was heard far around.

"What happened?" the brothers again asked.

But the Simpleton did not even answer; he only waved his hand. The three brothers continued to live their usual life, the two with cleverness and the younger with foolishness. They lived a day in and an equal day out. But one morning there came quite a different day from all others. They learned that big men were going all over the country with trumpets and players; that those men announced everywhere the will of the Tsar, and the Tsar's will was this: The Tsar Pea and the Tsaritza Carrot had an only daughter, the Tsarevna Baktriana, heiress to the throne. She was such a beautiful maiden that the sun blushed when she looked at it, and the moon, altogether too bashful, covered itself from her eyes. Tsar and Tsaritza had a hard time to decide to whom they should give their daughter for a wife. It must be a man who could be a proper ruler over the country, a brave warrior on the battlefield, a wise judge in the council, an adviser to the Tsar, and a suitable heir after his death. They also wanted a bridegroom who was young, brave, and handsome, and they wanted him to be in love with their Tsarevna. That would have been easy enough, but the trouble was that the beautiful Tsarevna loved no one. Sometimes the Tsar mentioned to her this or that one. Always the same answer, "I do not love him." The Tsaritza tried, too, with no better result; "I do not like him."

A day came when the Tsar Pea and his Tsaritza Carrot seriously addressed their daughter on the subject of marriage and said:

"Our beloved child, our very beautiful Tsarevna Baktriana, it is time for thee to choose a bridegroom. Envoys of all descriptions, from kings and tzars and princes, have worn our threshold, drunk dry all the cellars, and thou hast not yet found any one according to thy heart's wish."

The Tsarevna answered: "Sovereign, and thou, Tsaritza, my dear mother, I feel sorry for you, and my wish is to obey your desire. So let fate decide who is destined to become my husband. I ask you to build a hall, a high hall with thirty-two circles, and above those circles a window. I will sit at that window and do you order all kinds of people, tsars, kings, tsarovitchi, korolevitchi, brave warriors, and handsome fellows, to come. The one who will jump through the thirty-two circles, reach my window and exchange with me golden rings, he it will be who is destined to become my husband, son and heir to you."

The Tsar and Tsaritza listened attentively to the words of their bright Tsarevna, and finally they said: "According to thy wish shall it be done."

In no time the hall was ready, a very high hall adorned with Venetian velvets, with pearls for tassels, with golden designs, and thirty-two circles on both sides of the window high above. Envoys went to the different kings and sovereigns, pigeons flew with orders to the subjects to gather the proud and the humble into the town of the Tsar Pea and his Tsaritza Carrot. It was announced everywhere that the one who could jump through the circles, reach the window and exchange golden rings with the Tsarevna Baktriana, that man would be the lucky one, notwithstanding his rank—tsar or free kosack, king or warrior, tsarevitch, korolevitch, or fellow without any kinfolk or country.

The great day arrived. Crowds pressed to the field where stood the newly built hall, brilliant as a star. Up high at the window the tsarevna was sitting, adorned with precious stones, clad in velvet and pearls. The people below were roaring like an ocean. The Tzar with his Tzaritza was sitting upon a throne. Around them were boyars, warriors, and counselors.

The suitors on horseback, proud, handsome, and brave, whistle and ride round about, but looking at the high window their hearts drop. There were already several fellows who had tried. Each would take a long start, balance himself, spring, and fall back like a stone, a laughing stock for the witnesses.

The brothers of Ivanoushka the Simpleton were preparing themselves to go to the field also.

The Simpleton said to them: "Take me along with you."

"Thou fool," laughed the brothers; "stay at home and watch the chickens."

"All right," he answered, went to the chicken yard and lay down. But as soon as the brothers were away, our Ivanoushka the Simpleton walked to the wide fields and shouted with a mighty voice:

"Arise, bay horse—thou wind-swift steed,

Appear before me in my need;

Stand up as in the storm the weed!"

The glorious horse came running. Flames shone out of his eyes; out of his nostrils smoke came in clouds, and the horse asked with a man's voice:

"What is thy wish?"

Ivanoushka the Simpleton crawled into the horse's left ear, transformed himself and reappeared at the right ear, such a handsome fellow that in no book is there written any description of him; no one has ever seen such a fellow. He jumped onto the horse and touched his iron sides with a silk whip. The horse became impatient, lifted himself above the ground, higher and higher above the dark woods below the traveling clouds. He swam over the large rivers, jumped over the small ones, as well as over hills and mountains. Ivanoushka the Simpleton arrived at the hall of the Tsarevna Baktriana, flew up like a hawk, passed through thirty circles, could not reach the last two, and went away like a whirlwind.

The people were shouting: "Take hold of him! take hold of him!" The Tsar jumped to his feet, the Tsaritza screamed. Every one was roaring in amazement.

The brothers of Ivanoushka came home and there was but one subject of conversation—what a splendid fellow they had seen! What a wonderful start to pass through the thirty circles!

"Brothers, that fellow was I," said Ivanoushka the Simpleton, who had long since arrived.

"Keep still and do not fool us," answered the brothers.

The next day the two brothers were going again to the tsarski show and Ivanoushka the Simpleton said again: "Take me along with you."

"For thee, fool, this is thy place. Be quiet at home and scare sparrows from the pea field instead of the scarecrow."

"All right," answered the Simpleton, and he went to the field and began to scare the sparrows. But as soon as the brothers left home, Ivanoushka started to the wide field and shouted out loud with a mighty voice:

"Arise, bay horse—thou wind-swift steed,

Appear before me in my need;

Stand up as in the storm the weed!"

—and here came the horse, the earth trembling under his hoofs, the sparks flying around, his eyes like flames, and out of his nostrils smoke curling up.

"For what dost thou wish me?"

Ivanoushka the Simpleton crawled into the left ear of the horse, and when he appeared out of the right ear, oh, my! what a fellow he was! Even in fairy tales there are never such handsome fellows, to say nothing of everyday life.

Ivanoushka lifted himself on the iron back of his horse and touched him with a strong whip. The noble horse grew angry, made a jump, and went higher than the dark woods, a little below the traveling clouds. One jump, one mile is behind; a second jump, a river is behind; and a third jump and they were at the hall. Then the horse, with Ivanoushka on his back, flew like an eagle, high up into the air, passed the thirty-first circle, failed to reach the last one, and swept away like the wind.

The people shouted: "Take hold of him! take hold of him!" The Tsar jumped to his feet, the Tsaritza screamed, the princes and boyars opened their mouths.

The brothers of Ivanoushka the Simpleton came home. They were wondering at the fellow. Yes, an amazing fellow indeed! one circle only was unreached.

"Brothers, that fellow over there was I," said Ivanoushka to them.

"Keep still in thy own place, thou fool," was their sneering answer.

The third day the brothers were going again to the strange entertainment of the Tsar, and again Ivanoushka the Simpleton said to them: "Take me along with you."

"Fool," they laughed, "there is food to be given to the hogs; better go to them."

"All right," the younger brother answered, and quietly went to the back yard and gave food to the hogs. But as soon as his brothers had left home our Ivanoushka the Simpleton hurried to the wide field and shouted out loud:

"Arise, bay horse—them wind-swift steed,

Appear before me in my need;

Stand up as in the storm the weed!"

At once the horse came running, the earth trembled; where he stepped there appeared ponds, where his hoofs touched there were lakes, out of his eyes shone flames, out of his ears smoke came like a cloud.

"For what dost thou wish me?" the horse asked with a man's voice.

Ivanoushka the Simpleton crawled into his right ear and jumped out of his left one, and a handsome fellow he was. A young girl could not even imagine such a one.

Ivanoushka struck his horse, pulled the bridle tight, and lo! he flew high up in the air. The wind was left behind and even the swallow, the sweet, winged passenger, must not aspire to do the same. Our hero flew like a cloud high up into the sky, his silver-chained mail rattling, his fair curls floating in the wind. He arrived at the Tsarevna's high hall, struck his horse once more, and oh! how the wild horse did jump!

Look there! the fellow reaches all the circles; he is near the window; he presses the beautiful Tsarevna with his strong arms, kisses her on the sugar lips, exchanges golden rings, and like a storm sweeps through the fields. There, there, he is crushing every one on his way! And the Tsarevna? Well, she did not object. She even adorned his forehead with a diamond star.

The people roared: "Take hold of him!" But the fellow had already disappeared and no traces were left behind.

The Tsar Pea lost his royal dignity. The Tsaritza Carrot screamed louder than ever and the wise counselors only shook their wise heads and remained silent.

The brothers came home talking and discussing the wonderful matter.

"Indeed," they shook their heads; "only think of it! The fellow succeeded and our Tsarevna has a bridegroom. But who is he? Where is he?"

"Brothers, the fellow is I," said Ivanoushka the Simpleton, smiling.

"Keep still, I and I—," and the brothers almost slapped him.

The matter proved to be quite serious this time, and the Tsar and Tsaritza issued an order to surround the town with armed men whose duty it was to let every one enter, but not a soul go out. Every one had to appear at the royal palace and show his forehead. From early in the morning the crowds were gathering around the palace. Each forehead was inspected, but there was no star on any. Dinner time was approaching and in the palace they even forgot to cover the oak tables with white spreads. The brothers of Ivanoushka had also to show their foreheads and the Simpleton said to them:

"Take me along with you."

"Thy place is right here," they answered, jokingly. "But say, what is the matter with thy head that thou hast covered it with cloths? Did somebody strike thee?"

"No, nobody struck me. I, myself, struck the door with my forehead. The door remained all right, but on my forehead there is a knob."

The brothers laughed and went. Soon after them Ivanoushka left home and went straight to the window of the Tsarevna, where she sat leaning on the window sill and looking for her betrothed.

"There is our man," shouted the guards, when the Simpleton appeared among them. "Show thy forehead. Hast thou the star?" and they laughed.

Ivanoushka the Simpleton gave no heed to their bidding, but refused. The guards were shouting at him and the Tsarevna heard the noise and ordered the fellow to her presence. There was nothing to be done but to take off the cloths.

Behold! the star was shining in the middle of his forehead. The Tsarevna took Ivanoushka by the hand, brought him before Tsar Pea, and said:

"He it is, my Tsar and father, who is destined to become my groom, thy son-in-law and heir."

It was too late to object. The Tsar ordered preparations for the bridal festivities, and our Ivanoushka the Simpleton was wedded to the Tsarevna Baktriana. The Tsar, the Tsaritza, the young bride and groom, and their guests, feasted three days. There was fine eating and generous drinking. There were all kinds of amusements also. The brothers of Ivanoushka were created governors and each one received a village and a house.

The story is told in no time, but to live a life requires time and patience. The brothers of Ivanoushka the Simpleton were clever men, we know, and as soon as they became rich every one understood it at once, and they themselves became quite sure about it and began to pride themselves, to boast, and to brag. The humble ones did not dare look toward their homes, and even the boyars had to take off their fur caps on their porches.

Once several boyars came to Tsar Pea and said: "Great Tsar, the brothers of thy son-in-law are bragging around that they know the place where grows an apple tree with silver leaves and golden apples, and they want to bring this apple tree to thee."

The Tsar immediately called the brothers before him and bade them bring at once the wonderful tree, the apple tree with silver leaves and golden apples. The brothers had ever so many excuses, but the Tsar would have his way. They were given fine horses out of the royal stables and went on their errand. Our friend, Ivanoushka the Simpleton, found somewhere a lame old horse, jumped on his back facing the tail, and also went. He went to the wide field, grasped the lame horse by the tail, threw him off roughly, and shouted:

"You crows and magpies, come, come! There is lunch prepared for you."