|

|

Latin American Mythology

By Hartley Burr Alexander

CHAPTER IX.

THE TROPICAL FORESTS:

THE AMAZON AND BRAZIL

I The Amazons

II Food-Makers and Dance-Masks

III Gods, Ghosts, and Bogeys

IV Imps, Were-Beasts, and Cannibals

V Sun, Moon, and Stars

VI Fire, Flood, and Transformations

I. THE AMAZONS

1 ON his second voyage Columbus began to hear of an island inhabited by rich and warlike women, who permitted occasional visits from men, but endured no permanent residence of males among them. The valour of Carib women, who fought resolutely along with their husbands and brothers gave plausibility to this legend; and soon the myth of an island or country of Amazons became accepted truth, a dogma with wondertellers and a lure to adventurers. At first the fabulous island seemed near at hand "Matenino which lies next to Hispafiola on the side toward the Indies"; but as island after island was visited and the fabled women not found, their seat was pushed further and further on, till it came to be thought of as a country lying far in the interior of the continent or for the notion of its insular nature persisted as an island somewhere in the course of the great river of the Amazons. By the middle of the sixteenth century, explorers from the north, from the south, from the east, from the west, were all on the lookout for the kingdom of women and all hearing and repeating tales about them with such conviction that, as the Padre de Acufia remarks, 2 "it is not credible that a lie could have been spread throughout so many languages, and so many nations, with such appearance of truth."

In 1540-41 Francisco de Orellana sailed down the Amazon to the sea, hearing tales of the women warriors, and, as his cleric companion, Fray Caspar Carvajal, is credited with saying, on one occasion encountering some of them; for they fought with Indians who defended themselves resolutely "because they were tributaries of the Amazons," and he, and other Spaniards, saw ten or twelve Amazons fighting in front of the Indians, as if they commanded them . . . "very tall, robust, fair, with long hair twisted over their heads, skins round their loins, and bows and arrows in their hands, with which they killed seven or eight Spaniards." The description, in the circumstances described, does not inspire unlimited confidence in the friar's certainty of vision, but there is nothing incredible even in Indian women leading their husbands in combat. Pedro de Magelhaes de Gandavo gives a very interesting account 3 (still sixteenth century) of certain Indian women who, as he says, take the vow of chastity, facing death rather than its violation. These women follow no occupation of their sex, but imitate the ways of men, as if they had ceased to be women, going to war and to the hunt along with the men. Each of them, he adds, is served and followed by an Indian woman with whom she says she is married, and they live together like spouses. Parallels for this custom, (and for the reverse, in which men assume the costume, labours, and way of life of women) are to be found far and wide in America, indeed, to the Arctic Zone. Magelhaes de Gandavo is authority, too, for the statement that the coastal tribes of Brazil, like the Carib of the north, have a dual speech, differing for the two sexes, at least in some words; but this is no extremely rare phenomenon.

More truly in the mythical vein is the account given in the tale of the adventures of Ulrich Schmidel. Journeying northward from the city of Asuncion, in a company under the command of Hernando de Ribera, Schmidel and his companions heard tales of the Amazons whose land of gold and silver, the Indians astutely placed at a two months' journey from their own land. "The Amazons have only one breast," says Schmidel, "and they receive visits from men only twice or thrice a year. If a boy is born to them, they send him to the father; if a girl, they raise her, burning the right breast that it may not grow, to the end that they may the more readily draw the bow, for they are very valiant and make war against their enemies. These women dwell in an isle, which can only be reached by canoes." In the same credulous vein, but with quaintly learned embellishments, is Sir Walter Raleigh's account: "I had knowledge of all the rivers between Orenoque and Amazones, and was very desirous to understand the truth of those warlike women, because of some it is believed, of others not.

And though I digress from my purpose, yet I will set down that which hath been delivered me for truth of those women, and I spake with a cacique or lord of people, that told me he had been in the river, and beyond it also. The nations of these women are on the south side of the river in the provinces of Topago, and their chiefest strengths and retracts are in the islands situate on the south side of the entrance some sixty leagues within the mouth of the said river. The memories of the like women are very ancient as well in Africa as in Asia: In Africa these had Medusa for queen: others in Scithia near the rivers of Tanais and Thernodon: we find also that Lampedo and Marethesia were queens of the Amazons : in many histories they are verified to have been, and in divers ages and provinces: but they which are not far from Guiana do accompany with men but once in a year, and for the time of one month, which I gather by their relation, to be in April: and that time all kings of the border assemble, and queens of the Amazons; and after the queens have chosen, the rest cast lots for their Valentines. This one month they feast, dance, and drink of their wines in abundance; and the moon being done, they all depart to their own provinces. If they conceive, and be delivered of a son, they return him to the father; if of a daughter, they nourish it, and retain it: and as many as have daughters send unto the begetters a present: all being desirous to increase their sex and kind: but that they cut off the right dug of the breast, I do not find to be true. It was farther told me, that if in these wars they took any prisoners that they used to accompany with these also at what time so ever, but in the end for certain they put them to death : for they are said to be very cruel and bloodthirsty, especially to such as offer to invade their territories. These Amazons have likewise great store of these plates of gold which they recover by exchange chiefly for a kind of green stones, which the Spaniards call Piedras hijadas, and we use for spleen stones: and for the disease of the stone we also esteem them. Of these I saw divers in Guiana : and commonly every king or cacique hath one, which their wives for the most part wear; and they esteem them as great jewels."

The Amazon stone, or piedra de la hijada, came to be immensely valued in Europe for wonderful medicinal effects, a veritable panacea. Such stones were found treasured by the tribes of northern and north-central South America, passing by barter from people to people. "The form given to them most frequently," wrote Humboldt, 4 "is that of the Babylonian cylinders, longitudinally perforated, and loaded with inscriptions and figures. But this is not the work of the Indians of our day. . . . The Amazon stones, like the perforated and sculptured emeralds, found in the Cordilleras of New Grenada and Quito, are vestiges of anterior civilization." Later writers and investigators have identified the Amazon stones as green jade, probably the chalchihuitl which formed the esteemed jewel of the Aztecs; and it has been supposed that the centre from which spread the veneration for greenish and bluish stones chiefly jade and turquoise was somewhere in Mayan or Nahuatlan territory. Certainly it was widespread, extending from the Pueblos of New Mexico to the land of the Incas, and eastward into Brazil and the Antilles. That the South American tribes should have ascribed the origin of these treasures (at any rate, when questioned) to the Amazons, the treasure women, is altogether plausible. Nearly a century and a half after Raleigh's day, de la Condamine found the green jade stones still employed by the Indians to cure colic and epilepsy, heirlooms, they said, from their fathers who had received them from the husbandless women. That the Indians themselves have names for the Amazons is not strange names with such meanings as the Women-Living-Alone, the Husbandless-Women, the Masterful-Women, for the Europeans have been inquiring about such women ever since their coming; it is, however, worthy of note that Orellana, to whom is credited the first use of "Amazon" as a name for the great river, also heard a native name for the fabulous women; for Aparia, a native chief, after listening to Orellana's discourse on the law of God and the grandeur of the Castillean monarch, asked, as it were in rebuttal, whether Orellana had seen the Amazons, "whom in his language they call Coniapuyara, meaning Great Lord."

Modern investigators ascribe the myth of the Amazons, undeniably widespread at an early date, to various causes. The warlike character of many Indian women, already observed in the first encounters with Carib tribes by Columbus, is still attested by Spruce (1855): "I have myself seen that Indian women can fight . . . the women pile up heaps of stones to serve as missiles for the men. If, as sometimes happens, the men are driven back to and beyond their piles of stones, the women defend the latter obstinately, and generally hold them until the men are able to rally to the combat." Another factor in the myth is supposed to have been rumours of the golden splendour of the Incaic empire, with perhaps vague tales of the Vestals of the Sun; and still another is the occurrence of anomalous social and sexual relationships of women, easily exaggerated in passing from tribe to tribe.

A special group of myths of the latter type is of pertinent interest. Ramon Pane and Peter Martyr give an example in the tale of Guagugiana enticing the women away to Matenino. A somewhat similar story is reported by Barboza Rodriguez from the Rio Jamunda: the women, led away by an elder or chief, were accustomed to destroy their male children; but one mother spared her boy, casting him into the water where he lived as a fish by day, returning to visit her at night in human form; and the other women, discovering this, seduced the youth, who was finally disposed of by the jealous old man, whereupon the angry women fled, leaving the chief womanless. A like story is reported by Ehrenreich from Amazonas: The women gather beside the waters, where they make familiar with a water-monster, crocodilean in form, which is slain by the jealous men; then, the women rise in revolt, slay the men through deceit, and fare away on the stream. From Guiana Brett reports a myth on the same theme, the lover being, however, in jaguar form. Very likely the story of Maconaura and Anuanai'tu belongs to the same cycle; and it is of more than passing interest to observe that the story extends, along with the veneration of green and blue stones, to the Navaho and Pueblo tribes of North America, in the cosmogonies of which appears the tale of the revolt of the women, their unnatural relations with a water-monster, and their eventual return to the men. 5

Possibly the whole mythic cycle is associated with fertility ideas. Even in the arid Pueblo regions it is water from below, welling up from Mother Earth, that appears in the myth, and a water-dwelling being that is the agent of seduction. In South America and the Antilles, where fish-food is important and where the fish and the tortoise are recurring symbols of fertility, it is natural to find the fabled women in this association. And in this connexion it may be well to recall the discoveries of L. Netto on the island of Marajo, at the mouth of the Amazon. 6 There he found two mounds, a greater and a smaller, in such proportion that he regarded them as forming the image of a tortoise.

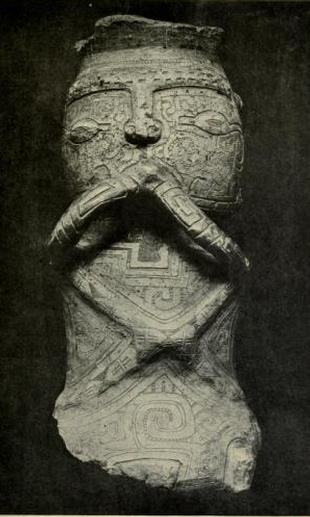

PLATE XL: Vase from the Island of Marajo, with character- istic decoration. The funeral vases and other remains from this region have suggested to L. Netto that here was the fabled Isle of the Amazons (see pages 286-87). The vase pictured is in the American Museum of Natural History.

Within the greater, which he regarded as the seat of a chieftain's or chieftainess's residence, commanding the country in every direction, he discovered funeral urns and other objects of a quality far superior to those known to tribes of the neighbouring districts, urns, hominiform in character, many of them highly decorated, and very many of the finest holding the bones of women. "If the tradition of a veritable Amazonian Gyneocraty has ever had any raison d'etre" said Netto, "certainly we see something enough like it in this nation of women ceramists, probably both powerful and numerous, and among whom the women-chiefs enjoyed the highest honours of the country."

II. FOOD-MAKERS AND DANCE-MASKS

"The rites of these infidels are almost the same," says the Padre de Acuna.2 "They worship idols which they make with their own hands; attributing power over the waters to some, and, therefore, place a fish in their hands for distinction; others they choose as lords of the harvests; and others as gods of their battles. They say that these gods came down from Heaven to be their companions, and to do them good. They do not use any ceremony in worshipping them, and often leave them forgotten in a corner, until the time when they become necessary; thus, when they are going to war, they carry an idol in the bows of their canoes, in which they place their hopes of victory; and when they go out fishing, they take the idol which is charged with dominion over the waters; but they do not trust in the one or the other so much as not to recognize another mightier God."

This seventeenth century description is on the whole true to the results obtained by later observers of the rites and beliefs of the Amazonian Indians. To be sure, a, certain amount of inter- pretation is desirable: the idolos of Acuna are hardly idols in the classical sense; rather they are in the nature of charms, fetishes, ritual paraphernalia, trophies, all that goes under the name "medicine," as applied to Indian custom. And it is true, too, that in so vast a territory, and among peoples who, although all savages, differ widely in habit of life, there are indefinite variations both in custom and mental attitude. Some tribes are but hunters, fishers, and root-gatherers; others practice agriculture also. Some are clothed; many are naked. Some practice cannibalism; others abhor the eaters of human flesh. Any student of the miscellaneous observations on the beliefs of the South American wild tribes, noted down by missionaries, officials, naturalists, adventurers, professional ethnologists, will at first surely feel himself lost in a chaos of contradiction. Nevertheless, granted a decent detachment and cool perspective, eventually he will be led to the opinion that these con- tradictions are not all due to the Indian; the prepossessions and understandings of the observers is no small factor; and even where the variation is aboriginal, it is likely to be in the local colour rather than in the underlying fact. In this broad sense Acuna's free characterization hits the essential features of Indian belief, in the tropical forests.

More than one later writer is in accord with the implicit emphasis which the Padre de Acuna places upon the importance of the food-giving animals and plants in Indian lore and rite. Of these food sources in many parts of South America the abundant fish and other fluvial life is primary. Hugo Kunike has, indeed, argued that the fish is the great symbol of fertility among the wild forest tribes, supporting the contention with analysis of the dances and songs, fishing customs, ornamentation-motives, and myths of these tribes. 8 Certainly he has shown that the fish plays an outstanding role in the imaginative as well as in the economic life of the Indian, appearing, in one group of myths, even as a culture hero and the giver of tobacco. Even more than the fish, the turtle ("the beef of the Amazon"), which is a symbol of generation in many parts of America, appears in Amazonian myth, where in versions of the Hare and the Tortoise (here the Deer replaces the Hare), of the contest of the Giant and the Whale pulling contrari-wise, and in similar fables the turtle appears as the Trickster. So, also, the frog, which appears in magical and cosmogonical roles, as in the Canopus myth narrated by Teschauer, where a man married a frog, and, becoming angered, cut off her leg and cast it into the river, where the leg became the fish surubim (Pimelodes tigrinus), while the body rose to heaven to appear in the constellation. The like tale is told by other tribes with respect to Serpens and to the Southern Cross.

But important as water-life is to the Amazonian, it would appear from Pere Tastevin's rebuttal of Kunike's contention that the Indian does not regard the fish with any speaking veneration. The truth would seem to be that in South America, as in North, it is the Elders of the Kinds, the ancestral guardians and perpetuators of the various species, both of plants and animals, that are appealed to, dimly and magically by the tribes lower in intelligence, with conscious ritual by the others. Garcilasso de la Vega's description of the religions of the more primitive stratum of Peruvian times and peoples applies equally to the whole of America: "They venerated divers animals, some for their cruelty, as the tiger, the lion, the bear; . . . others for their craft, as the monkeys and the fox; others for fidelity, as the dog; for quickness, as the lynx; . . . eagles and hawks for their power to fly and supply themselves with game; the owl for its power to see in the dark. . . . They adored the earth, as giving them its fruits; the air, for the breath of life; the fire which warmed them and enabled them to eat properly; the llama which supplied troops of food animals; . . . the maize which gave them bread, and the other fruits of their country. Those dwelling on the coast had many divinities, but regarded the sea as the most potent of all, calling it their mother, because of the fish which it furnished with which they nourished their lives. All these, in general, venerated the whale because of its hugeness; but beside this, commonly in each province they devoted a particular cult to the fish which they took in greatest abundance, telling a pleasant tale to the effect that the First of all the Fish dwells in the sky, engendering all of its species, and taking care, each season, to send them a sufficiency of its kind for their good." Pere Tastevin bears witness to the same belief today: "To be successful in fishing, it is not to the fish that the Indian addresses himself, but to the mother of the animal he would take. If he goes to fish the turtle, he must first strike the prow of his canoe with the leaf of a small caladium which is called yurard taya, caladium of the turtle; he will strike in the same fashion the end of his turtle harpoon and the point of his arrow, and often he will carry the plant in his canoe. But let him beware lest he take the first turtle! She is the grandmother of the others; she is of a size which confounds the imagination, and she will drag down with her the imprudent fisherman to the bottom of the waters, where she will give him a fever without recovery. But if he respect her, he will be successful in his fishing for the rest of the day."

Universal among the tropical wild tribes is the love of dancing. In many of the tribes the dances are mask dances, the masks representing animals of all kinds; and the masks are frequently regarded as sacra, and are tabu to the women. In other cases, it is just the imitative powers of the child of nature that are called upon, and authorities agree that the Indian can and does imitate every kind of bird, beast, and fish with a bodily and vocal verisimilitude that gives to these dances, where many participate, the proper quality of a pandemonium. Authorities disagree as to the intent of the dancing; it is obvious to all that they are occasions of hilarity and fun; it is evident again that they lead to excitement, and especially when accompanied by the characteristic potations of native liquors, to warlike, sexual, or imaginative enthusiasm. Whether there is conscious magic underlying them (as cannot be doubted in the case of the similar dances of North America) is a matter of difference of opinion, and may well be a matter of differing fact, the less intellectual tribes following blindly that instinct for rhythm and imitation which, says Aristotle, is native to all men, while with the others the dance has become consciously ritualized. Cook says 9 of the Bororo bakororo a medley of hoots, squeaks, snorts, chirps, growls, and hisses, accompanied with appropriate actions, that it "is always sung on the vesper of a hunting expedition, and seems to be in honor of the animal the savages intend to hunt the following day. . . . After the singing of the bakororo that I witnessed, all the savages went outside the great hut, where they cleared a space of black ground, then formed animals in relief with ashes, especially the figure of the tapir, which they purposed to hunt the next day." This looks like magic, though, to be sure, one need not press the similia similibus doctrine too far: human beings are gifted with imagination and the power of expressing it, and it is perhaps enough to assume that imitative and mask dances, images like to those described, or like the bark-cut figures and other animal signs described by von den Steinen among the Bakairi and other tribes, are all but the natural exteriorization of fantasy, perhaps vaguely, perhaps vividly, coloured with anticipations of the fruits of the chase.

If anything, there seems to be a clearer magical association in rites and games connected with plants than with those that mimic animals. Especially is this true of the manioc, or cassava, which is important not only as a food-giving plant, but as the source of a liquor, and, again, is dangerous for its poison, which, as Teschauer remarks, must have caused the death of many during the long period in which the use of the plant was developed. Pere Taste vin describes men and women gathering about a trough filled with manioc roots, each with a grater, and as they grate rapidly and altogether, a woman strikes up the song: "A spider has bitten me! A spider has bitten me! From under the leaf of the hard a spider has bitten me!" The one opposite answers: "A spider has bitten me! Bring the cure! Quick, make haste! A spider has bitten me!" And all break in with Yandu se suu, by which is understood nothing more than just the rhythmic tom-tom on the grater. Similar is the song of the sudarari a plant whose root resembles the manioc, which multiplies with wonderful rapidity, and the presence of which in a manioc field is regarded as insuring large manioc roots: "Permit, O patroness, that we sing during this beautiful night!" with the refrain, "Sudarari!" This, says Pere Tastevin, is the true symbol of the fertility of fields, shared in a lesser way by certain other roots.

It is small wonder that the spirit or genius of the manioc figures in myth, nor is it surprising to find that the predominant myth is based on the motive of the North American Mondamin story. WhifTen remarks, of the north-western Amazonians: 10 "What I cannot but consider the most important of their stories are the many myths that deal with the essential and now familiar details of everyday life in connexion with the manihot utilissima and other fruits"; and he goes on to tell a typical story: The Good Spirit came to earth, showed the manioc to the Indians, and taught them to extract its evils; but he failed to teach them how the plant might be reproduced. Long afterward a virgin of the tribe, wandering in the woods, was seduced by a beautiful young hunter, who was none other than the manioc metamorphosed. A daughter born of this union led the tribe to a fine plantation of manioc, and taught them how to reproduce it from bits of the stalk. Since then the people have had bread. The more elaborate version of Couto de Magalhaes tells how a chief who was about to kill his daughter when he found her to be with child, was warned in a dream by a white man not to do so, for his daughter was truly innocent and a virgin. A beautiful white boy was born to the maiden, and received the name Mani ; but at the end of a year, with no apparent sign of ailing, he died. A strange plant grew upon his grave, whose fruit intoxicated the birds; the Indians then opened the grave, and in place of the body of Mani discovered the manioc root, which is thence called Mani-oka, House of Mani." Teschauer gives another version in which Mani lived many years and taught his people many things, and at the last, when about to die told them that after his death they should find, when a year had passed, the greatest treasure of all, the bread-yielding root.

It is probable that some form of the Mani myth first suggested to pious missionaries the extension of the legendary journeys of Saint Thomas among the wild tribes of the tropics. From Brazil to Peru, says Granada,11 footprints and seats of Santo Tomds Apostol, or Santo Tome, are shown; and he associates these tales with the dissemination and cultivation of the all-useful herb, as probably formed by a Christianizing of the older culture myth. Three gifts are ascribed to the apostle, the treasure of the faith, the cultivation of the manioc, and relief from epidemics. "Keep this in your houses," quoth the saint, "and the divine mercy will never withhold the good." The three gifts a faith, a food, and a medicine, are the almost universal donations of Indian culture heroes, and it is small wonder if minds piously inclined have found here a meeting-ground of religions. An interesting suggestion made by Sefior Lafone Quevado would make Tupan, Tupa, Tumpa, the widespread Brazilian name for god, if not a derivative, at least a cognate form of Tonapa, the culture hero of the Lake Titicaca region, who was certainly identified as Saint Thomas by missionaries and Christian Indians at a very early date. That the myth itself is aboriginal there can be no manner of doubt, Bochica and Quetzalcoatl are northern forms of it; nor need we doubt that Tupa or Tonapa is a native high deity in all probability celestial or solar, as Lafone Quevado believes. The union of native god and Christian apostle is but the pretty marriage of Indian and missionary faiths.

One of the most poetical of Brazilian vegetation myths is told by Koch-Griinberg in connexion with the Yurupari festival, a mask dance (yurupari means just "mask" according to Pere Taste vin, although some have given it the significance of "demon") celebrated in conjunction with the ripening of fruits of certain palms. Women and small boys are excluded from the fete; indeed, it is death for women even to see the flutes and pipes, as Humboldt said was true of the sacred trumpet of the Orinoco Indians in his day. The legend turns on the music of the pipes, and is truly Orphic in spirit. . . .

Many, many years ago there came from the great Water-House, the home of the Sun, a little boy who sang with such wondrous charm that folk came from far and near to see him and harken. Milomaki, he was called, the Son of Milo. But when the folk had heard him, and were returned home, and ate of fish, they fell down and died. So their kinsfolk seized Milomaki, and built a funeral pyre, and burnt him, because he had brought death amongst them. But the youth went to his death still with song on his lips, and as the flames licked about his body, he sang: "Now I die, my son! now I leave this world!" And as his body began to break with the heat, still he sang in lordly tones: "Now bursts my body! now I am dead!" And his body was destroyed by the flames, but his soul ascended to heaven. From the ashes on the same day sprang a long green blade, which grew and grew, and even in another day had become a high tree, the first paxiuba palm. From its wood the people made great flutes, which gave forth as wonderful melodies as Milomaki had aforetime sung; and to this day the men blow upon them whenever the fruits are ripe. But women and little boys must not look upon the flutes, lest they die. This Milomaki, say the Yahuna, is the Tupana of the Indians, the Spirit Above, whose mask is the sky.

The region about the headwaters of the Rio Negro and the Yapura the scene of Koch-Griinberg's travels is the centre of the highest development of the mask dances, which seem to be recent enough with some of the tribes. In the legends of the Kabeua it is Kuai, the mythic hero and fertility spirit of the Arawak tribes, who is regarded as the introducer of the mask dances, Kuai, who came with his brethren from their stone-houses in the hills to teach the dances to his children, and who now lives and dances in the sky-world. This is a myth which immediately suggests the similar tales of Zuni and the other Pueblos, and the analogy suggested is more than borne out by what Koch-Griinberg 12 tells of the Katcina-like character of the masks. They all represent spirits or daemones.

PLATE XLI: Dance or ceremonial masks of Brazilian Indians, now in the Peabody Museum.

They are used in ceremonies in honour of the ancestral dead, as well as in rituals addressed to nature powers. Furthermore, the spirit or daemon is temporarily embodied in the mask, "the mask is for the Indian the daemon"; though, when the mask is destroyed at the end of a ceremonial, the Daemon of the Mask does not perish; rather he becomes mdskara-anga, the Soul of the Mask; and, now invisible, though still powerful, he flies away to the Stone-house of the Daemones, whence only the art of the magician may summon him. "All masks are Daemones," said Koch-Griinberg's informant, "and all Daemones are lords of the mask."

III. GODS, GHOSTS, AND BOGEYS

What are the native beliefs of the wild tribes of South America about gods, and what is their natural religion? If an answer to this question may be fairly summarized from the expressions of observers, early and recent, it is this: The Indians gene rally believe in good powers and in evil powers, superhuman in character. The good powers are fewer and less active than the evil; at their head is the Ancient of Heaven. Little attention is paid to the Ancient of Heaven, or to any of the good powers, they are good, and do not need attention. The evil powers are numerous and busy; the wise man must be ever on the alert to evade them, turn them when he can, placate when he must.

Cardim is an early witness as to the beliefs of the Brazilian Indians. 13 "They are greatly afraid of the Devil, whom they call Curupira, Taguain, Pigtangua, Machchera, Anhanga: and their fear of him is so great, that only with the imagination of him they die, as many times already it hath happened." . . . "They have no proper name to express God, but they say the Tupan is the thunder and lightning, and that this is he that gave them the mattocks and the food, and because they have no other name more natural and proper, they call God Tupan."

Thevet says that "Toupan" is a name for the thunder or for the Great Spirit. Keane says of the Botocudo, perhaps the lowest of the Brazilian tribes: "The terms Yanchang, Tapan, etc., said to mean God, stand merely for spirit, demon, thunder, or at the most the thunder-god." Of these same people Ehrenreich reports: "The conception of God is wanting; they have no word for it. The word Tupan, appearing in some vocabularies, is the well-known Tupi-Guaranian word, spread by missionaries far over South America. The Botocudo understand by it, not God, but the Christian priest himself!" Neither have they a word for an evil principle; but they have a term for those souls of the departed which, wandering among men at night, can do them every imaginable ill, and "this raw animism is the only trace of religion if one can so call it as yet observed among them." Hans Staden's account of the religion of the Tupinambi, among whom he fell captive, drops the scale even lower: their god, he says, was a calabash rattle, called tarnmar aka, with which they danced; each man had his own, but once a year the paygis, or "prophets," pretended that a spirit come from a far country had endowed them with the power of conversing with all Tammarakas, and they would interpret what these said. Women as well as men could become paygis, through the usual Indian road to such endowment, the trance. Similar in tenor is a recent account of the religion of the Bororo. 14 The principal element in it is the fear of evil spirits, especially the spirits of the dead. Bope and Mareba are the chief spirits recognized. "The missionaries spoke of the Bororos believing in a good spirit (Mareba) who lives in the fourth heaven, and who has a filha Mareba (son), who lives in the first heaven, but it is apparent that the priest merely heard the somewhat disfigured doctrines that had been learned from some missionary" . . . But why, asks the reader, should this conception come from the missionary rather than the Bororo in South America, when its North American parallel comes from the Chippewa rather than from the missionary?

..." In reality Bope is nothing else than the Digichibi of the Camacoco, Nenigo of the Kadioeo men, or Idmibi of the Kadioeo women, the Ichaumra or Ighamba of the Matsikui, i. e., the human soul, which is regarded as a bad spirit. . . . The Bororo often make images of animals and Bope out of wax. After they have been made they are beaten and destroyed."

Of the Camacan, a people of the southern part of Bahia, the Abbe Ignace says that while they recognize a supreme being, Gueggiahora, who dwells, invisible, above the stars which he governs, yet they give him no veneration, reserving their prayers for the crowd of spirits and bogeys ghosts of the dead, thunderers and storm-makers, were-beasts, and the like, that inhabit their immediate environment, forming, as it were, earth's atmosphere. The Chorotes, too, believe in good and in bad spirits, paying their respects to the latter; while their neighbours, the Chiriguano, hold that the soul, after death, goes to the kingdom of the Great Spirit, Tumpa, where for a time he enjoys the pleasures of earth in a magnified degree; but this state cannot last, and in a series of degenerations the spirit returns to earth as a fox, as a rat, as a branch of a tree, finally to fall into dissolution with the tree's decay. Tumpa is, 'according to Pierini, the same as Tupa, the beneficent supreme spirit being known by these names among the Guarayo, although in their myths the principal personages are the hero brothers, Abaangui and Zaguaguayu, lords of the east and the west, and two other personages, Mbiracucha (perhaps the same as the Peruvian Viracocha) and Candir, the last two, like Abaangui, being shapers of lands and fathers of men.

D'Orbigny 15 describes a ritual dance of the Guarayo, men and women together, in which hymns were addressed to Tamoi, the Grandfather or Ancient of the Skies, who is called upon to descend and listen. "These hymns," he says, "are full of naive figures and similitudes. They are accompanied by sounding reeds, for the reason that Tamoi ascended toward the east from the top of a bamboo, while spirits struck the earth with its reeds. Moreover, the bamboo being one of the chief benefactions of Tamoi, they consider it as the intermediary between them and the divinity." Tamoi is besought in times of seeding, that he may send rain to revive the thirsting earth; his temple is a simple octagonal hut in the forest. "I have heard them ask of nature, in a most figurative and poetic style, that it clothe itself in magnificent vestments ; of the flowers, that they bloom; of the birds, that they take on their richest plumage and resume their joyous song; of the trees, that they bedeck themselves with verdure; all to the end that these might join with them in calling upon Tamoi, whom they never implored in vain."

In another connexion d'Orbigny says: "The Guarani, from the Rio de la Plata to the Antilles and from the coasts of Brazil to the Bolivian Andes, revere, without fearing him, a beneficent being, their first father, Tamoi, or the Ancient of the Skies, who once dwelt among them, taught them agriculture, and afterwards disappeared toward the East, from whence he still protects them." Doubtless, this is too broad a generalization, and d'Orbigny's own reports contain numerous references to tribes who fear the evil rather than adore the good in nature. Nevertheless, there is not wanting evidence looking in the other direction. One of the most recent of observers, Thomas Whiffen, says of the northwest Brazilian tribes: 16 "On the whole their religion is a theism, inasmuch as their God has a vague, personal, anthropomorphic existence. His habitat is above the skies, the blue dome of heaven, which they look upon as the roof of the world that descends on all sides in contact with the earth. Yet again it is pantheism, this God being represented in all beneficent nature; for every good thing is imbued with his spirit, or with individual spirits subject to him."

According to Whiffen's account the Boro Good Spirit, Neva (in the same tribe Navena is the representative of all evil), once came to earth, assuming human guise. The savannahs and other natural open places, where the sun shines freely and the sky is open above, are the spots where he spoke to men. But a certain Indian vexed Neva, the Good Spirit, so that he went again to live on the roof of the world; but before he went, he whispered to the tigers, which up to that time had hunted with men as with brothers, to kill the Indians and their brethren.

It is easy to see, from such a myth as this, how thin is the line that separates good and evil in the Indian's conception, indeed, how hazy is his idea of virtue. Probably the main truth is that the Amazonian and other wild tribes generally believe in a Tupan or Tamoi, who is on the whole beneficent, is mainly remote and indifferent to mankind, and who, when he does reveal himself, is most likely to assume the form of (to borrow Whiffen's phrase) " a tempestipresent deity." "Although without temples, altars or idols," says Church, of the tribes of the Gran Chaco, "they recognize superior powers, one of whom is supreme and thunders from the sierras and sends the rain." Olympian Zeus himself is the Thunderer; in Scandinavia Tiu grows remote, and Thor with his levin is magnified. Similarly, in North America, the Thunderbirds loom huger in men's imagination than does Father Sky. On the whole for the South American tribes, the judgement of Couto de Magalhaes seems sane; that the aboriginals of Brazil possessed no idea of a single and powerful God, at the time of the discovery, and indeed that their languages were incapable of expressing the idea; but that they did recognize a being superior to the others, whose name was Tupan. Observers from Acuiia to Whiffen have noted individual sceptics among the Indians; certain tribes even (though the information is most likely from individuals) are said to believe in no gods and no spirits; and in some tribes the beliefs are obviously more inchoate than in others. But in the large, the South Americans are at one with all man-kind in their belief in a Spirit of Good, whose abode is the Above, and in their further belief in multitudes of dangerous spirit neighbours sharing with them the Here.

IV. IMPS, WERE-BEASTS, AND CANNIBALS

It would be a mistake to assume that all of these dangerous neighbours are invariably evil, just as it is erroneous to expect even the Ancient of the Skies to be invariably beneficent. In Cardim's list of the Brazilian names of the Devil he places first the Curupira. 17 But Curupira, or Korupira (as Teschauer spells it), is nearer to the god Pan than to Satan. Korupira is a daemon of the woods, guardian of all wild things, mischievous and teasing even to the point of malice and harm at times, but a giver of much good to those who approach him properly: he knows the forest's secrets and may be a wonderful helper to the hunter, and he knows, too, the healing properties of herbs. Like Pan he is not afoot like a normal man; and some say his feet turn backward, giving a deceptive trail; some say that his feet are double; some that he has but one rounded hoof. He is described as a dwarf, bald and one-eyed, with huge ears, hairy body, and blue-green teeth, and he rides a deer or a rabbit or a pig. He insists that game animals be killed, not merely wounded, and he may be induced to return lost cattle, for he is a propitiable sprite, with a fondness for tobacco. A tale which illustrates his character, both for good and evil, is of the unlucky hunter, whom, in return for a present of tobacco, the Korupira helps; but the hunter must not tell his wife, and when she, suspecting a secret, follows her husband, the Korupira kills her. In another story the hunter, using the familiar ruse of pretended self-injury by means of which Jack induces the Giant to stab himself (an incident in which Coyote often figures in North America), gets the Korupira to slay himself; after a month he goes back to get the blue teeth of his victim, but as he strikes them the Korupira comes to life. He gives the hunter a magic bow, warning him not to use it against birds; the injunction is disobeyed, the hunter is torn to pieces by the angry flocks, but the Korupira replaces the lost flesh with wax and brings the hunter to life. Again, he warns the hunter not to eat hot things; the latter disobeys, and forthwith melts away.

Another "devil" mentioned by Cardim is the Anhanga. The Anhanga is formless, and lives indeed only in thought, especially in dreams; in reality, he is the Incubus, the Nightmare. The Anhanga steals a child from its mother's hammock, and puts it on the ground beneath. The child cries, "Mother! Mother! Beware the Anhanga which lies beneath us!" The mother strikes, hitting the child; while the laughing Anhanga departs, calling back, "I have fooled you! I have fooled you!" In another tale, which recalls to us the tragedy of Pentheus and Agave, a hunter meets a doe and a fawn in the forest. He wounds the fawn, which calls to its mother; the mother returns, and the hunter slays her, only to discover that it is his own mother, whom the wicked sprite (here the Yurupari) had transformed into a doe.

But even more to be feared than the daemones are the ghosts and beast-embodied souls. 18 Like most other peoples in a parallel stage of mental life, the South American Indians very generally believe in metempsychosis, souls of men returning to earth in animal and even vegetal forms, and quite consistently with the malevolent purpose of wreaking vengeance upon olden foes. The belief has many characteristic modifications: in some cases the soul does not leave the body until the flesh is decayed; in many instances it passes for a time to a life of joy and dancing, a kind of temporary Paradisal limbo; but always it comes sooner or later back to fulfill its destiny as a were-beast. 19 The South American tiger, or jaguar, is naturally the form in which the reincarnate foe is most dreaded, and no mythic conception is wider spread in the continent than is that of the were-jaguar, lying in wait for his human foe, who, if Garcilasso's account of jaguar-worshipping tribes is correct, offered themselves unresistingly when the beast was encountered.

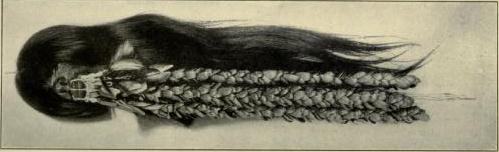

It is probable that the conception of the were-jaguar, or of beast reincarnations, is associated in part at least with the enigmatical question of tropical American cannibalism. 20A recent traveller, J. D. Haseman, who visited a region of reputed cannibalism, and found no trace of the practice, is of the opinion that it has no present existence, if indeed it ever had any. But against this view is the unanimous testimony of nearly all observers, with explicit descriptions of the custom, from Hans Staden and Cardim down to Koch-Griinberg and Whiffen. Hans Staden, who was held as a slave among the Tupinambi of the Brazilian coast, describes a visit which he made to his Indian master for the purpose of begging that certain prisoners be ransomed. "He had before him a great basket of human flesh, and was busy gnawing a bone. He put it to my mouth and asked if I did not wish to eat. I said to him: 'There is hardly a wild animal that will eat its kind; how then shall I eat human flesh?' Then he, resuming his meal: 'I am a tiger, and I find it good." Cardim's description of cannibal rites is in many ways reminiscent of the Aztec sacrifice of the devoted youth to Tezcatlipoca : the victim is painted and adorned, is given a wife, and indeed so honoured that he does not even seek to escape, "for they say that it is a wretched thing to die, and lie stinking, and eaten with worms "; throughout, the ritual element is obvious. On the other hand, the conception of degradation is clearly a strong factor. Whiffen makes this the foremost reason for the practice. The Indian, he says, has very definite notions as to the inferiority of the brute creation. To resemble animals in any way is regarded as degrading; and this, he regards as the reason for the widespread South American custom of removing from the body all hair except from the scalp, and again for the disgrace attendant upon the birth of twins. But animals are slaughtered as food for men: what disgrace, then to the captured enemy comparable with being used as food by his captor? Undoubtedly, the vengeful nature of anthropophagy is a strong factor in maintaining the custom; from Hans Staden on, writers tell us that while the captive takes his lot fatalistically his last words are a reminder to his slayers that his kindred are preparing a like end for them. Probably the unique and curious South American method of preparing the heads of slain enemies as trophies, by a process of removing the bones, shrinking, and decorating, is a practice with the same end the degradation of the enemy, corresponding, of course, to the scalping and head-taking habits of other American tribes.

It is to be expected that with the custom of anthropophagy widespread, it should be constantly reflected in myth. A curious and enlightening instance is in the Bakairi hero-tale reported by von den Steinen: 21 A jaguar married a Bakairi maiden; while he was gone ahunting, his mother, Mero, the mother of all the tiger kind, killed the maiden, whose twin sons were saved from her body by a Caesarian section. The girl's body was then served up to the jaguar husband, without his knowledge. When he discovered the trick infuriated at the trick and at having eaten his wife's flesh, he was about to attack Mero: "I am thy mother!" she cried, and he desisted. Here we have the whole moral problem of the house of Pelops primitively adumbrated.

More in the nature of the purely ogreish is the tale related by Couto de Magalhaes, 22 the tale of Ceiuci, the Famished Old Woman (who he says, is none other than the Pleiades). A young man sat in a tree-rest, when Ceiuci came to the waters beneath to fish. She saw the youth's shadow, and cast in her line. He laughed. She looked up. "Descend," she cried; and when he refused, she sent biting ants after him, compelling him to drop into the water. Thence she snared him, and went home with her game. While she was gone for wood to cook her take, her daughter looked into the catch, and saw the youth, at his request concealing him. "Show me my game or I will kill you," commanded the ogress. In company with the youth the maiden takes flight the "magic flight," which figures in many myths, South American and North. As they flee, they drop palm branches which are transformed into animals, and these Ceiuci stops to devour. But in time all kinds of animals have been formed, and the girl can help the youth no longer. "When you hear a bird singing kan kan, kan kan, kan kan" she says, in leaving him, "my mother is not far." He goes on till he hears the warning. The monkeys hide him, and Ceiuci passes. He resumes his journey, and again hears the warning chant. He begs the serpents to hide him; they do so, and the ogress passes once more. But the serpents now plan to devour the youth; he hears them laying their plot and calls upon the macauhau, a snake-eating bird, to help him; and the bird eats the serpents. Finally, the youth reaches a river, where he is aided by the herons to cross. From a tree he beholds a house, and going thither he finds an old woman complaining that her maniocs are being stolen by the agouti. The man tells her his story. He had started out as a youth; he is now old and white-haired. The woman recognizes him as her son, and she takes him in to live with her. Couto de Magalhaes sees in this tale an image of the journey of life with its perils and its loves ; the love of man for woman is the first solace sought, but abiding rest is found only in mother love. At least the story will bear this interpretation; nor will it be alone as a South American tale in which the moral meaning is conscious.

V. SUN, MOON, AND STARS

When the Greeks began to speculate about "the thing the Sophists call the world," they named it sometimes the Heaven, Ouranos, sometimes the Realm of Order, Cosmos; and the two terms seemed to them one in meaning, for the first and striking evidence of law and order in nature which man discovers is in the regular and recurrent movements of the heavenly bodies. But it takes a knowledge of number and a sense of time to be able to truly discern this orderliness of the celestial sequences; and both of these come most naturally to peoples dwelling in zones wherein the celestial changes are reflected in seasonal variations of vegetation and animal life.

PLATE XLII: Trophy head prepared by Jivaro Indians, Ecuador, now in the Peabody Museum. In the preparation of such trophies the bones are carefully removed, the head shrunken and dried, and frequently, as in this example, ornamented with brilliant feathers.

The custom of preparing the heads of slain enemies or of sacrificial victims as trophies was widespread in aboriginal America, North and South, the North American custom of scalping being probably a late development from this earlier practice. It is possible that some at least of the masks which appear upon mythological figures in Nasca and other representations are meant to betoken trophy heads.

In the wellnigh seasonless tropics, and among peoples gifted with no powers of enumeration (for there are many South American tribes that cannot number the ten digits), it is but natural to expect that the cycles of the heavens should seem as lawless as does their own instable environment, and the stars themselves to be actuated by whims and lusts analogous to their own.

" I wander, always wander; and when I get where I want to be, I shall not stop, but still go on...."

This Song of the Turtle, of the Paumari tribes, says Steere, 23 reflects their own aimless life, wandering from flat to flat of the ever-shifting river; and it might be taken, too, as the image of the heavenly motions, as these appear to peoples for whom there is no art of counting. Some writers, to be sure, have sought to asterize the greater portion of South American myth, on the general hypothesis that sun-worship dominates the two Americas ; but this is fancy, with little warrant in the evidence. Sun, moon, and stars, darkness and day, all find mythic expression; but there is little trace among the wild tribes of anything approaching ritual devoted to these, or of aught save mythopoesy in the thought of them.

The most rudimentary level is doubtless represented by the Botocudo, with whom, says Ehrenreich, 24 taru signifies either sun or moon, but principally the shining vault of heaven, whether illuminated by either of these bodies or by lightning; further, the same word, in suitable phrase, comes to mean both wind and weather, and even night. In contrast with this we have the extraordinary assurance that the highly intelligent Passe tribe believes (presumably by their own induction) that the earth moves and the sun is stationary. The intermediate, and perhaps most truly mythic stage of speculation is represented in the Bakairi tales told by von den Steinen, in which the sun is placed in a pot in the moving heaven; every evening, Evaki, the wife of the bat who is the lord of darkness, claps to the lid, concealing the sun while the heaven returns to its former posstion. Night and sleep are often personified in South American stories, as in the tale of the stork who tried to kill. sleep, and here Evaki, the mistress of night, is represented as stealing sleep from the eyes of lizards, and dividing it among all living beings.

A charming allegory of the Amazon and its seasons is recorded by Barboza Rodriguez. Many years ago the Moon would become the bride of the Sun; but when they thought to wed, they found that this would destroy the earth : the burning love of the Sun would consume it, the tears of the Moon would flood it; and fire and water would mutually destroy each other, the one extinguished, the other evaporated. Hence, they separated, going on either side. The Moon wept a day and a night, so that her tears fell to earth and flowed down to the sea. But the sea rose up against them, refusing to mingle the Moon's tears with its waters; and hence it comes that the tears still flow, half a year outward, half a year inward. Myths of the Pleiades are known to the Indians throughout Brazil, who regard the first appearance of this constellation in the firmament as the sign of renewing life, after the dry season, "Mother of the Thirsty" is one interpretation of its name. One myth tells of an earthly hunter who pierced the sky with arrows and climbed to heaven in quest of his beloved. Being athirst he asked water of the Pleiades. She gave it him, saying: "Now thou hast drunk water, thou shalt see whence I come and whither I go. One month long I disappear and the following month I shine again to the measure of my appointed time. All that beholds me is renewed." Teschauer credits many Brazilian Indians with an extensive knowledge of the stars their course, ascension, the time of their appearance and disappearance, and the changes of the year that correspond, but this seems somewhat exaggerated in view of the limited amount of the lore cited in its support, legends of the Pleiades and Canopus already mentioned, and in addition only Orion, Venus, and Sirius. Of course the Milky Way is observed, and as in North America it is regarded as the pathway of souls. So, in the odd Taulipang legend given by Koch-Griinberg, the Moon, banished from its house by a magician, reflects : " Shall I become a tapir, a wild-pig, a beast of the chase, a bird? All these are eaten! I will ascend to the sky! It is better there than here; I will go there, from thence to light my brothers below." So with his two daughters he ascended the skies, and the first daughter he sent to a heaven above the first heaven, and the second to a third heaven; but he himself remained in the first heaven. "I will remain here," he said, "to shine upon my brothers below. But ye shall illuminate the Way for the people who die, that the soul shall not remain in darkness!"

On an analogous theme but in a vein that is indeed grim is the Cherentes star legend reported by de Oliveira. 25 The sun is the supreme object of worship in this tribe, while the moon and the stars, especially the Pleiades, are his cult companions. In the festival of the dead there is a high pole up which the souls of the shamans are supposed to climb to hold intercourse with kinsfolk who are with the heavenly spheres ; and it is this pole and the beliefs which attach to it that is, doubtless, the subject of the myth. The tale is of a young man who, as he gazed up at the stars, was attracted by the exceptional beauty of one of them: "What a pity that I cannot shut you up in my gourd to admire you to my heart's content!" he cried; and when sleep came, he dreamed of the star. He awoke suddenly, amazed to find standing beside him a young girl with shining eyes: "I am the bright star you wished to keep in your gourd," she said; and at her insistence he put her into the gourd, whence he could see her beautiful eyes gazing upward. After this the young man had no rest, for he was filled with apprehension because of his supermundane guest; only at night the star would come from her hiding-place and the young man would feast his eyes on her beauty. But one day the star asked the young man to go hunting, and at a palm-tree she required that he climb and gather for her a cluster of fruit; as he did so, she leaped upon the tree and struck it with a wand, and immediately it grew until it touched the sky, whereto she tied it by its thick leaves and they both jumped into the sky-world. The youth found himself in the midst of a desolate field, and the star, commanding him not to stir, went in quest of food. Presently he seemed to hear the sound of festivity, songs and dances, but the star, returning, bade him above all not to go to see the dancing. Nevertheless, when she was gone again, the youth could not repress his curiosity and he went toward the sound. . . . "What he saw was fearful! It was a new sort of dance of the dead! A crowd of skeletons whirled around, weird and shapeless, their putrid flesh hanging from their bones and their eyes dried up in their sunken orbits. The air was heavy with their foul odour." The young man ran away in horror. On his way he met the star who blamed him for his disobedience and made him take a bath to cleanse him of the pollution. But he could no longer endure the sky-world, but ran to the spot where the leaves were tied to the sky and jumped on to the palm-tree, which immediately began to shrink back toward the earth: "You run away in vain, you shall soon return," the star called after him; and so indeed it was, for he had barely time to tell his kindred of his adventure before he died. And "thus it was known among the Indians that no heaven of delight awaits them above, even though the stars shine and charm us."

The uniting of heaven and earth by a tree or rock which grows from the lower to the upper world is found in many forms, and is usually associated with cosmogonic myths (true creation stories are not common in Brazil). Such a story is the Mundurucu tale, reported by Teschauer, 26 which begins with a chaotic darkness from which came two men, Karusakahiby, and his son, Rairu. Rairu stumbled on a bowl-shaped stone; the father commanded him to carry it; he put it upon his head, and immediately it began to grow. It grew until it formed the heavens, wherein the sun appeared and began to shine. Rairu, recognizing his father as the heaven-maker, knelt before him; but Karu was angry because the son knew more than did he. Rairu was compelled to hide in the earth. The father found him and was about to strike him, but Rairu said: "Strike me not, for in the hollow of the earth I have found people, who will come forth and labour for us." So the First People were allowed to issue forth, and were separated into their tribes and kinds according to colour and beauty. The lazy ones were transformed into birds, bats, pigs, and butterflies. A somewhat similar Kaduveo genesis, narrated by Fric, tells how the various tribes of men were led from the underground world and successively assigned their several possessions; last of all came the Kaduveo, but there were no more possessions to distribute; accordingly to them was assigned the right to war upon the other Indians and to steal their lands, wives, and children.

The Mundurucu genesis opens: "In the beginning the world lay in darkness." In an opposite and indeed very unusual way begins the cosmogonic myth recorded by Couto de Magalhaes: 27 "In the beginning there was no night; the day was unbroken. Night slept at the bottom of the waters. There were no animals, but all things could speak." It is said, proceeds the tale, that at this time the daughter of the Great Serpent married a youth who had three faithful servants. One day he said to these servants: "Begone! My wife desires no longer to lie with me." The servants departed, and the husband called upon his wife to lie with him. She replied: "It is not yet night." He answered: "There is no night; day is without end." She: "My father owns the night. If you wish to lie with me, seek it at the river's source." So he called his three servants, and the wife dispatched them to secure a nut of the tucuma (a palm of bright orange colour, important to the Indians as a food and industrial plant). When they reached the Great Serpent he gave them the nut, tightly sealed: "Take it. Depart. But if you open it, you are lost." They set out in their canoe, but presently heard from within the nut: " Ten ten ten, ten ten ten." It was the noise of the insects of the night. "What is this noise? Let us see," said one. The leader answered: "No; we will be lost. Make haste." But the noise continued and finally all drew together in the canoe, and with fire melted the sealing of the fruit. The imprisoned night streamed forth! The leader cried: "We are lost! Our mistress already knows that we have freed the night!" At the same time the mistress, in her house, said to her husband: "They have loosed the night. Let us await the day." Then all things in the forests metamorphosed themselves into animals and birds; all things in the waters became water-fowl and fishes; and even the fisherman in his canoe was transformed into a duck, his head into the duck's head, his paddle into its web feet, his boat into its body. When the daughter of the Great Serpent saw Venus rise, she said: "The dawn is come. I shall divide day from night." Then she unravelled a thread, saying: "Thou shalt be cubuju [a kind of pheasant]; thou shalt sing as dawn breaks." She whitened its head and reddened its feathers, saying: "Thou shalt sing always at dawn of day." Then she unravelled another thread, saying: "Thou shalt be inambu" [a perdrix that sings at certain hours of the night] ; and powdering it with cinders : "Thou shalt sing at eve, at midnight, and at early morn." From that time forth the birds sang at the time appropriate to them, in day or night. But when the three servants returned, their mistress said to them: "Ye have been unfaithful. Ye have loosed the night. Ye have caused the loss of all. For this ye shall become monkeys, and swing among the branches for all time."

VI. FIRE, FLOOD, AND TRANSFORMATIONS

Purchases translation of Cardim begins : 28 " It seemeth that this people had no knowledge of the beginning and creation of the world, but of the deluge it seemeth they have some notice: but as they have no writings nor characters such notice is obscure and confused; for they say that the waters drowned all men, and that one only escaped upon a Janipata with a sister of his that was with child and that from these two they have their beginning and from thence began their multiplying and increase."

This is a fair characterization of the general cosmogonical ideas of the South American wild tribes. There is seldom any notion of creation; there is universally, it would seem, some legend of a cataclysm, or series of them, fire and flood, offering such general analogies to the Noachian story as naturally to suggest to men unacquainted with comparative mythology the inference that the tale of Noah was indeed the source of all. Following the deluge or conflagration there is a series of incidents which might be regarded as dispersal stories, tales of transformations and migrations by means of which the tribes of animals and men came to assume their present form. Very generally, too, the Transformer-Heroes are the divine pair, sometimes father and son, but commonly twin brothers, who give the animals their lasting forms, instruct men in the arts, and after Herculean labors depart, the one to become lord of the east and the day, the other lord of the west and the night, the one lord of life, the other lord of death and the ghost-world. It is not unnatural to see in this hero pair the sun and the moon, as some authorities do, though it would surely be a mistake to read into the Indian's thought the simple identification which such a statement implies: a tale is first of all a tale, with the primitive man; and if it have an allegorical meaning this is rarely one which his language can express in other terms than the tale itself.

One of the best known of the South American deluge stories is the Caingang legend 29 which the native narrator had heard "from the mother of the mother of his mother, who had heard it in her day from her ancient progenitors." The story is the common one of people fleeing before the flood to a hill and clinging to the branches of a tree while they await the subsidence of the waters, an incident of a kind which may be common enough in flood seasons, and which might be taken as a mere reflection of ordinary experience but for the fact of the series of transformations which follow the return to dry land; and these include not only the formation of the animal kinds, but the gift of song from a singing gourd and a curious process of divination, taught by the ant-eater, by means of which the sex of children is foretold.

The flood is only one incident in a much more comprehensive cycle of events, assembled variously by various peoples, but having such a family likeness that one may without impropriety regard the group as the tropical American Genesis. Of this cycle the fullest versions are those of the Yuracare, as reported by d'Orbigny, and of the Bakairi, as reported by von den Steinen. 30

In the Bakairi tale the action begins in the sky-world. A certain hunter encountered Oka, the jaguar, and agreed to make wives for Oka if the latter would spare him. He made two wives out of wood, blowing upon them. One of these wives swallowed two finger-bones, and became with child. Mero, the mother of Oka and of the jaguar kind, slew the woman, but Kuara, the brother of Oka, performed the Caesarian operation and saved the twins, who were within her body. These twins were the heroes, Keri and Kame. To avenge their mother they started a conflagration which destroyed Mero, themselves hiding in a burrow in the earth. Kame came forth too soon and was burned, but Keri blew upon his ashes and restored him to life. Keri in his turn was burned and restored by Kame. First, in their resurrected lives did these two assume human form. Now begins the cycle of their labours. They stole the sun and the moon from the red and the white vultures, and gave order to their way in the heavens, keeping them in pots, coverable, when the light of these bodies should be concealed: sun, moon, and ruddy dawn were all regarded as made of feathers. Next, heaven and earth, which were as yet close together, were separated. Keri said to the heavens: "Thou shalt not remain here. My people are dying. I wish not that my people die." The heavens answered: "I will remain here!" "We shall exchange places," said Keri; whereupon he came to earth and the sky rose to where it now is. The theft of fire from the fox, who kept it in his eye; the stealing of water from the Great Serpent, with the formation of rivers; the swallowing of Kame by a water monster, and his revivescence by Keri; the institution of the arts of house-building, fishery, dancing; and the separation of human kinds ; all these are incidents leading up to the final departure of Keri and Kami, who at the last ascend a hill, and go thence on their separate ways. "Whither are they gone? Who knows? Our ancestors knew not whither they went. Today no one knows where they are."

The Bakairi dwell in the central regions of Brazil; the Yuracare are across the continent, near the base of the Andes. From them d'Orbigny obtained a version of the same cosmogony, but fuller and with more incidents. The world began with sombre forests, inhabited by the Yuracare. Then came Sararuma and burned the whole country. One man only escaped, he having constructed an underground refuge. After the conflagration he was wandering sadly through the ruined world when he met Sararuma. "Although I am the cause of this ill, yet I have pity on you," said the latter, and he gave him a handful of seeds from whose planting sprang, as by magic, a magnificent forest. A wife appeared, as it were ex nihilo, and bore sons and a daughter to this man. One day the maiden encountered a beautiful tree with purple flowers, called Ule. Were it but a man, how she would love it! And she painted and adorned the tree in her devotion, with sighs and hopes, hopes that were not in vain, for the tree became a beautiful youth. Though at first she had to bind him to keep him from wandering away, the two became happy spouses. But one day Ule, hunting with his brothers, was slain by a jaguar. His bride, in her grief like Isis, gathered together the morsels of his torn body. Again, her love was rewarded and Ule was restored to life, but as they journeyed he glanced in a pool, saw a disfigured face, where a bit of flesh had not been recovered, and despite the bride's tears took his departure, telling her not to look behind, no matter what noise she heard. But she was startled into doing this, became lost, and wandered into a jaguar's lair. The mother of the jaguars took pity upon her, but her four sons were for killing her. To test her obedience they commanded her to eat the poisonous ants that infested their bodies; she deceived three of them by substituting seeds for the ants, which she cast to the ground; but the fourth had eyes in the back of his head, detected the ruse and killed her. From her body was torn the child which she was carrying, Tiri, who was raised in secret by the jaguar mother.

When Tiri was grown he one day wounded a paca, which said: "You live in peace with the murderers of your mother, but me, who have done you no harm, you wish to kill." Tiri demanded the meaning of this, and the paca told him the tale. Tiri then lay in wait for the jaguar brothers, slaying the first three with arrows, but the jaguar with eyes in the back of his head, climbed into a tree, calling upon the trees, the sun, stars, and moon to save him. The moon snatched him up, and since that time he can be seen upon her bosom, while all jaguars love the night. Tiri, who was the master of all nature, taught cultivation to his foster-mother, who now had no sons to hunt for her. He longed for a companion, and created Cam, to be his brother, from his own finger-nail; and the two lived in great amity, performing many deeds. Once, invited to a feast, they spilled a vase of liquor which flooded the whole earth and drowned Caru; but when the waters were subsided, Tiri found his brother's bones and revived him. The brothers then married birds, by whom they had children. The son of Caru died and was buried. Tiri then told Caru at the end of a certain time to go seek his son, who would be revived, but to be careful not to eat him. Caru, finding a manioc plant on the grave, ate of it. Immediately a great noise was heard, and Tiri said: " Caru has disobeyed and eaten his son; in punishment he and all men shall be mortal, and subject to all toils and all sufferings."

In following adventures the usual transformations take place, and mankind, in their tribes, are led forth from a great rock, Tiri saying to them: "Ye must divide and people all the earth, and that ye shall do so I create discord and make you enemies of one another." Thus arose the hostility of tribes. Tiri now decided to depart, and he sent birds in the several directions to discover in which the earth extends farthest. Those sent to the east and the north speedily returned, but the bird sent toward the setting sun was gone a long time, and when at last it returned it brought with it beautiful feathers. So Tiri departed into the West, and disappeared.

NOTES

I. The myth of the Amazons is not only the earliest European legend to become acclimated in America (cf. Ch. I, ii [with Note 5], iv; Ch. VIII, iii), it is also one of the most obstinate and recurrent, and a perennial subject of the interest of commentators. For general discussions of the question, see Chamberlain, "Recent Literature

on the South American Amazons," in JAFL xxiv. 16-20 (1911), and Rothery, The Amazons in Antiquity and Modern Times (London, 1910), which reviews the world-wide scope and forms of the myth, chh. viii, ix, being devoted to the South American instances. Still more recent is Whiff en, The Northwest Amazons (New York, 1916), pp. 239-40.

2. Markham [e], p. 122. Carvajal is cited in the same work, pp. 34, 26.

3. Magalhaes de Gandavo, ch. x (TC, pp. 116-17); Schmidel (Hulsius), ch. xxxiii; Raleigh (in Hakluyt's Voyages, vol. x), pp. 366-68.

4. Humboldt [b] (Ross), ii. 395 ff.; iii. 79. Lore pertaining to the Amazon stone is hardly second to that dealing with the Amazons themselves. Authorities here cited are La Condamine, pp. 102-113; Spruce, ii, ch. xxvi (p. 458 quoted); Ehrenreich [b], especially pp. 64, 65, with references to Barbosa Rodrigues and to Brett [b]. Others to consult are Rothery, ch. ix; T. Wilson, "Jade in America," in CA xii (Paris, 1902); J. E. Pogue, "Aboriginal Use of Turquoise in North America," in A A, new series, xiv (1912); and I. B. Moura, "Sur le progres de 1'Amazonie," in CA xvi (Vienna, 1910).

5. See Mythology of All Nations, x. 160, 203, 205, 210, and Note 64.

6. Netto, CA vii (Berlin, 1890), pp. 201 ff.

7. Acurla (Markham [e]), p. 83. The literature of a region so vast as that of the basin of the Amazon and the coasts of Brazil is itself naturally great and scattered. The earlier narratives such as those of Acufia, Cardim, Carvajal, Orellana, Ortiguerra, de Lery, Ulrich Schmidel, and Hans Staden are valuable chiefly for the hints which they give of the aboriginal prevalence of ideas studied with more understanding by later investigators. Among the more important later writers are d'Orbigny, Couto de Magalhaes, Ehrenreich, Koch-Grxinberg, von den Steinen, Whiffen, and Miller; while Teschauer's contributions to Anthropos, i, furnish the best collection for the Brazilian region as a whole.

8. Kunike, "Der Fisch als Fruchtbarkeitssymbol," in Anthropos vii (1912), especially section vi; Teschauer [a], part i, texts (mainly derived from Couto de Magalhaes); Tastevin, sections iii, vi; Garcilasso de la Vega, bk. i, chh. ix, x (quoted).

9. Cook, p. 385; cf. Whiffen, chh. xv, xvi, xviii; and von den Steinen [b], pp. 239-41.

10. Whiffen, pp. 385-86. The myths of manioc and other vegetation are from Teschauer [a], p. 743; Couto de Magalhaes, ii. 134-35; Whiffen, loc. cit.; and Koch-Griinberg [a], ii. 292-93.

11. The legends of St. Thomas are discussed by Granada, ch. xv, especially pp. 210-15 (cf. also, ch. xx, "Origen mitico y excelencias del urutau," with accounts of the vegetation-spirit Neambiu). The suggested relationship of Brazilian and Peruvian myth is considered by Lafone Quevado in RevMP iii. 332-36; cf, also, Wissler, The American Indian, pp. 198-99. It may be worth noting that there is a group of South American names of mythic heroes or deities which might, in one form or another, suggest or be confounded with Tomas, among them the Guarani Tamoi (same as Tupan, and perhaps related to Tonapa), the Tupi Zume. The legend has been discussed in the present work in Ch. VII, iv.

12. Koch-Griinberg [a], ii. 173-34; f r details regarding the use of masks and mask-dances, see also Whiffen; Tastevin; M. Schmidt, ch. xiv; Cook, ch. xxiii; Spruce, ch. xxv; von den Steinen [b]; and Stradelli.

13. Cardim (Purchas, xvi), pp. 419-20; Thevet [b], pp. 136-39; Keane, p. 209; Ehrenreich [c], p. 34; Hans Staden [b], ch. xxii.

14. Fric and Radin, p. 391; Ignace, pp. 952-53; von Rosen, pp. 656-67; Pierini, pp. 703 ff.

15. D'Orbigny, vii, ch. xxxi, pp. 12-24; iv, 109-15; cf. also pp. 265, 296-99, 337, 502-10.

16. Whiffen, ch. xvii (p. 218 quoted); Church, p. 235. The subject here is a continuation of that discussed in Ch. VIII, ii (with Note 7); in connexion with which, with reference to Brazil, the comment of Couto de Magalhaes is significant (part ii, p. 122): "Como quer que seja, a idea de un Deus todo poderoso, e unico, nao foi possuida pelos nossos selvagens ao tempo da descoberta da America; e pois nao era possival que sua lingua tivesse uma palvra que a podesse expressar. Ha no entretanto um principio superior qualificado com o nome de Tupan a quern parece que attribuiam maior poder do que aos outras." The real question to be resolved is what are the necessary attributes of a "supreme being." Cf. Mythology of All Nations, x, Note 6.

17. On wood-demons and the like, in addition to Cardim, see Teschauer [a], pp. 24-34; Koch-Griinberg, [a], i. 190; ii. 157; and Granada, ch. xxxi, "Demonios, apariciones, fantasmas, etc."

18. On ghosts and metamorphoses, see Ignace, pp. 952-53; Fric and Radin; Fric [a]; von Rosen, p. 657; and Cook, p. 122.

19. On were-beasts, see Ambrosetti [b]; cf. Garcilasso de la Vega, bk. i, ch. ix.

20. Loci citati touching cannibalism are Haseman, pp. 345-46; Staden [a], ch. xliii; [b], chh. xxv, xxviii; Cardim (Purchas), ii. 431-40; and Whiffen, pp. 118-24.

21. Von den Steinen [b], p. 323.

22. Couto de Magalhaes, part i, texts.

23. Steere, "Narrative of a Visit to the Indian tribes on the Purus River," in Report of the U. S. National Museum, 1901 (Washington, 1903)

24. Loci citati are Ehrenreich [b], pp. 34-40; [c], p. 34; Markham [d], p. 119; von den Steinen [a], p. 283; [b], pp. 322 fL; Teschauer [a], pp. 731 ff. (citing Barbosa Rodrigues and others); Koch-Griinberg [b], no. I.

25. Feliciano de Oliveira, CA xviii (London, 1913), pp. 394-96.

26. Teschauer [a], p. 731. The Kaduveo genesis is given by Fric, in CA xviii, 397 ff. Stories of both types are widespread throughout the two Americas.

27. Couto de Magalhaes, part i, texts. This is among the most interesting of all American myths; it is clearly cosmogonic in character, yet it reverses the customary procedure of cosmogonies, beginning with an illuminated world rather than a chaotic gloom. Possibly this is an indication of primitiveness, for the conception of night and chaos as the antecedent of cosmic order would seem to call for a certain degree of imaginative austerity; it is not simple nor childlike.

28. Cardim (Purchas), p. 418.

29. Adam [b], p. 319. Other sources for tales of the deluge are Borba [b], pp. 223-25; Kissenberth, in ZE xl. 49; Ehrenreich [b], pp. 30-31; Teschauer; and von Martius.

30. D'Orbigny, iii. 209-14; von den Steinen [a], pp. 282-85; [b] pp. 32227; and cf. the Kapoi legends in Koch-Griinberg [a]. The Yuracara tale narrated by d'Orbigny is one of the best and most fully reported of South American myths.