|

|

Latin American Mythology

By Hartley Burr Alexander

CHAPTER VIII. THE TROPICAL FORESTS:

THE ORINOCO AND GUIANA

I Lands and Peoples

II Spirits and Shamans

III How Evils Befell Mankind

IV Creation and Cataclysm

V Nature and Human Nature

I. LANDS AND PEOPLES

AMONG earth's great continental bodies South America is second only to Australia in isolation. This is true not only geographically, but also in regard to flora and fauna, and in respect of its human aborigines and their cultures. To be sure, within itself the continent shows a diversity as wide, perhaps, as that of any; and certainly no continent affords a sharper contrast both of environment and of culture than is that of the Andes and the civilized Andeans to the tropical forests with their hordes of unqualified savages. There are, moreover, streams of influence reaching from the southern toward the northern America the one, by way of the Isthmus, tenuously extending the bond of civilization in the direction of the cultured nations of Central America and Mexico; the other carrying northward the savagery of the tropics by the thin line of the Lesser Antilles; and it is, of course, possible that this double movement, under way in Columbian days, was the retroaction of influences that had at one time moved in the contrary direction. Yet, on the whole, South America has its own distinct character, whether of savagery or of civilization, showing little certain evidence of recent influence from other parts of the globe. Au fond the cultural traits implements, social organization, ideas are of the types common to mankind at similar levels; but their special developments have a distinctly South American character, so that, whether we compare Inca with Aztec, or Amazonian with Mississippian, we perceive without hesitancy the continental idiosyncracy of each. It is certain that South America has been inhabited from remote times; it is certain, too, that her aboriginal civilizations are ancient, reckoned even by the Old World scale. A daring hypothesis would make this continent an early, and perhaps the first home of the human species a theory that would not implausibly solve certain difficulties, assuming that the differences which mark aboriginal North from aboriginal South America are due to the fact that the former continent was the meeting-place and confluence of two streams a vastly ancient, but continuous, northward flow from the south, turned and coloured by a thinner and later wash of Asiatic source.1

The peoples of South America are grouped by d'Orbigny, 2 as result of his ethnic studies of rhomme americain made during the expedition of 1826-33, into three great divisions, or races: the Ando-Peruvian, comprising all the peoples of the west coast as far as Tierra del Fuego; the Pampean, including the tribes of the open countries of the south; and the Brasilio-Guaranian, composed of the stocks of those tropical forests which form the great body of the South American continent. With modifications this threefold grouping of the South American aborigines has been maintained by later ethnologists. One of the most recent studies in this field (W. Schmidt, " Kulturkreise und Kulturschichten in Siidamerika," in ZE xlv [1913]), while still maintaining the triple classification, nevertheless shows that the different groups have mingled and intermingled in confusing complexity, following successive cycles of cultural influence. Schmidt's division is primarily on the basis of cultural traits, with reference to which he distinguishes three primary groups: (i) Peoples of the "collective grade," who live by hunting, fishing, and the gathering of plants, with the few exceptions of tribes that have learned some agriculture from neighbours of a higher culture. In this group are the Gez, or Botocudo, and the Puri-Coroados stocks of the east and south-east of Brazil; the stocks of the Gran Chaco, the Pampas, and Tierra del Fuego; while the Araucanians and certain tribes of the eastern Cordilleras of the Andes are also placed in this class. (2) Groups of peoples of the Hackbaustufe, mostly practicing agriculture and marked by a general advance in the arts, as well as by the presence of a well-defined patriarchy and evidences of totemism in their social organization. In this group are included the great South American linguistic stocks the Cariban, Arawakan, and Tupi-Guaranian, inhabiting the forests and semi-steppes of the regions drained by the Orinoco and Amazon and their tributaries, as well as the tribes of the north-east coast of the continent. (3) Groups of the cultured peoples of the Andes Chibcha, Incaic, and Calchaqui.

The general arrangement of these three divisions follows the contour of the continent. The narrow mountain ridge of the west coast is the seat of the civilized peoples; the home of the lowest culture is the east coast, extending in a broad band of territory from the highlands of the Brazilian provinces of Pernambuco and Bahia south-westward to the Chilean Andes and Patagonia; between these two, occupying the whole centre of the continent, with a broad base along the northern coast and narrowing wedge-like to the south, is the region of the intermediate culture group.

Most of what is known of the mythology of South American peoples comes from tribes and nations of the second and third groups from the Andeans whose myths have been sketched in preceding chapters, and from the peoples of the tropic forests. The region inhabited by the latter group is too vast to be treated as a simple unit; nor is there, in the chaotic intermixture of tongues and tribes, any clear ethnic demarcation of ideas. In default of other principle, it is appropriate and expedient, therefore, to follow the natural division of the territory into the geographical regions broadly determined by the great river-systems that traverse the continent. These are three: in the north the Orinoco, with its tributaries, draining the region bounded on the west by the Colombian plateau and the Llanos of the Orinoco, and on the south by the Guiana Highlands; in the centre the Amazon, the world's greatest river, the mouth of which is crossed by the Equator, while the stream itself closely follows the equatorial line straight across the continent to the Andes, though its great tributaries drain the central continent, many degrees to the south; and in the south the Rio de la Plata, formed by the confluence of the Parana and Uruguay, and receiving the waters of the territories extending from El Gran Chaco to the Pampas, beyond which the Patagonian plains and Chilean Andes taper southward to the Horn. In general, the Orinoco region is the home of the Carib and Arawak tribes; the Amazonian region is the seat and centre of the Tupi-Guaranians; while the region extending from the Rio de la Plata to the Horn is the aboriginal abode of various peoples, mostly of inferior culture. It should be borne in mind, however, that the simplicity of this plan is largely factitious. Linguistically, aboriginal South America is even more complex than North America (at least above Mexico) ; and the whole central region is a melange of verbally unrelated stocks, of which, for the continent as a whole, Chamberlain's incomplete list gives no less than eighty-three. 3

II. SPIRITS AND SHAMANS

"The aborigines of Guiana," writes Brett, 4 "in their naturally wild and untaught condition, have had a confused idea of the existence of one good and supreme Being, and of many inferior spirits, who are supposed to be of various kinds, but generally of malignant character. The Good Spirit they regard as the Creator of all, and, as far as we could learn, they believe Him to be immortal and invisible, omnipotent and omniscient. But notwithstanding this, we have never discovered any trace of religious worship or adoration paid to Him by any tribe while in its natural condition. They consider Him as a Being too high to notice them; and, not knowing Him as a God that heareth prayer, they concern themselves but little about Him." In another passage the same writer states that the natives of Guiana "all maintain the Invisibility of the Eternal Father. In their traditionary legends they never confound Him the Creator, the 'Ancient of Heaven' with the mythical personages of what, for want of a better term, we must call their heroic age; and though sorcerers claim familiarity with, and power to control, the inferior (and malignant) spirits, none would ever pretend to hold intercourse with Him, or that it were possible for mortal man to behold Him." A missionary to the same region, Fray Ruiz Blanco, 5 earlier by some two hundred years, says of the religion of these aborigines that, "The false rites and diableries with which the multitude are readily duped are innumerable . . . briefly . . . there is the seated fact that all are idolaters, and there is the particular fact that all abhor and greatly fear the devil, whom they call Iboroquiamio."

Minds of a scientific stamp see the matter somewhat differently. "The natives of the Orinoco," Humboldt declares, 6 " know no other worship than that of the powers of nature; like the ancient Germans they deify the mysterious object which excites their simple admiration (deorum nominibus appellant secretum illud, quod sola reverentia vident)" From the point of view of an ethnologist of the school of Tylor, im Thurn describes the religion of the Indians of Guiana : Having no belief in a hierarchy of spirits, they can have, he says, "none in any such beings as in higher religions are called gods. ... It is true that various words have been found in all, or nearly all, the languages, not only of Guiana, but also of the whole world, which have been supposed to be the names of a great spirit, supreme being, or god"; nevertheless, he concludes, "the conception of a God is not only totally foreign to Indian habits of thought, but belongs to a much higher stage of intellectual development than any attained by them."

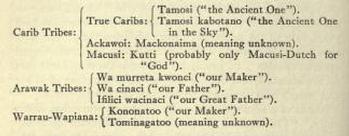

It is from such contrary evidences as these that the true character of aboriginal beliefs must be reconstructed. Im Thurn says of the native names that they "to some extent acquired a sense which the missionaries imparted to them"; and when we meet, in such passages as that quoted from Brett, the ascription of attributes like omniscience and omnipotence to primitive divinities, there is indeed cause for humour at the missionary's expense. But there are logical idols in more than one trade; the ethnologists have their full share of them. Im Thurn gives us a list of indigenous appellations of the Great Spirit of Guiana :

Of all these names Thurn remarks that in those whose meanings

are known "only three ideas are expressed

(i) One who lived long ago and is now in sky-land;

(2) the maker of the Indians; and

(3) their father. None of these ideas," he continues, "in any way

involve the attributes of a god ..." Obviously, acceptance of

this negation turns upon one's understanding of the meaning of

"god."

The Cariban Makonaima (there are many variants, such as Makanaima, Makunaima, and the like) is a creator-god and the hero of a cosmogony. It is possible that his name connects him with the class of Kenaima (or Kanaima), avengers of murder and bringers of death, who are often regarded as endowed with magical or mysterious powers; and in this case the term may be analogous to the Wakanda and Manito of thenorthern continent. Schomburgk 8 states that Makunaima means "one who works in the night"; and if this be true, it is curious to compare with such a conception the group of Arawakan demiurgic beings whom he describes. According to the Arawak myths, a being Kururumany was the creator of men, while Kulimina formed women. Kururumany was the author of all good, but coming to earth to survey his creation, he discovered that the human race had become wicked and corrupt; wherefore he deprived them of everlasting life, leaving among them serpents, lizards, and other vermin. Wurekaddo ("She Who Works in the Dark") and Emisiwaddo ("She Who Bores Through the Earth") are the wives of Kururumany; and Emisiwaddo is identified as the cushi-ant, so that we have here an interesting suggestion of world-building ants, for which analogues are to be found far north in America, in the Pueblos and on the North-West Coast. There is, however, a faineant god high above Kururumany, one Aluberi, pre-eminent over all, who has no concern for the affairs of men; while other supreme beings mentioned by Schomburgk are Amalivaca who is, however, rather a Trickster-Hero and the group that, among the Maipuri, corresponds to the Arawakan family of divine beings, Purrunaminari ("He Created Men"), Taparimarru, his wife, and Sisiri, his son, whom she, without being touched by him, conceived to him from the mere love he bore her a myth in which, as Schomburgk observes, we should infer European influence.

Humboldt, in describing the religion of the Orinoco aborigines says of them that "they call the good spirit Cachimana; it is the Manitou, the Great Spirit, that regulates the seasons and favours the harvests. Along with Cachimana there is an evil principle, lolokiamo, less powerful, but more artful, and in particular more active." On the whole, this characterization represents the consensus of observation of traveller, missionary, and scientist from Columbian days to the present and for the wilder tribes of the whole of both South and North America.

There is a good being, the Great Spirit, more or less remote from men, often little concerned with human or terrene affairs, but the ultimate giver of life and light, of harvest food and game food. There is an evil principle, sometimes personified as a Lord of Darkness, although more often conceived not as a person, but as a mischievous power, or horde of powers, manifested in multitudes of annoying forms. Among shamanistic tribes little attention is paid to the Good Power; it is too remote to be seriously courted; or, if it is worshipped, solemn festivals, elaborate mysteries, and priestly rites are the proper agents for attracting its attention. On the other hand, the Evil Power in all its innumerable and tricky embodiments, must be warded off by constant endeavour by shamanism, "medicine," magic. The tribes of the Orinoco region are, db origine, mainly in the shamanistic stage. The peaiman is at once priest, doctor, and magician, whose main duty is to discover the deceptive concealment of the malicious Kenaima and, by his exorcisms, to free men from the plague. That the Kenaima is of the nature of a spirit appears from the fact that the term is applied to human malevolences, especially when these find magic manifestation, as well as to evils emanating from other sources. Thus, the avenger of a murder is a Kenaima, and he must not only exact life for life; he must achieve his end by certain means and with rites insuring himself against the ill will of his victim's spirit. Again, the Were-Jaguar is a Kenaima. "A jaguar which displays unusual audacity," says Brett, 4 "will often unnerve even a brave hunter by the fear that it may be a Kanaima tiger. 'This,' reasons the Indian, 'if it be but an ordinary wild beast, I may kill with bullet or arrow; but what will be my fate if I assail the man-destroyer the terrible Kanaima?"

The Kenaima, the man-killer, whether he be the human avenger upon whom the law of a primitive society has imposed the task of exacting retribution, or whether he be the no less dreaded inflicter of death through disease, or magically induced accident, or by shifting skins with a man-slaying beast, is only one type of the spirits of evil. Others are the Yauhahu and Orehu (Arawak names for beings which are known to the other tribes by other titles). The Yauhahu are the familiars of sorcerers, the peaimen, who undergo a long period of probationary preparation in order to win their favour and who hold it only by observing the most stringent tabus in the matter of diet. The Orehu are water-sprites, female like the mermaids, and they sometimes drag man and canoe down to the depths of their aquatic haunts; yet they are not altogether evil, for Brett tells a story, characteristically American Indian, of the origin of a medicine-mystery. In very ancient times, when the Yauhahu inflicted continual misery on mankind, an Arawak, walking besides the water and brooding over the sad case of his people, beheld an Orehu rise from the stream, bearing in her hand a branch which he planted as she bade him, its fruit being the calabash, till then unknown. Again she appeared, bringing small white pebbles, which she instructed him to enclose in the gourd, thus making the magic-working rattle; and instructing him in its use and in the mysteries of the Semecihi, this order was established among the tribes. The "Semecihi" are of course, the medicine-men of the Arawak, corresponding to the Carib peaimen, though the word itself would seem to be related to the Tai'no zemi. Relation to the Islanders is, indeed, suggested by the whole myth, for the Orehu is surely only the mainland equivalent for the Haitian woman-of-the-sea, Guabonito, who taught the medicine-hero, Guagugiana, the use of amulets of white stones and of gold.

III. HOW EVILS BEFELL MANKIND

Not many primitive legends are more dramatically vivid than the Carib story of Maconaura and Anuanai'tu, 10 and few myths give a wider insight into the ideas and customs of a people. The theme of the tale is very clearly the coming of evil as the consequence of a woman's deed, although the motive of her action is not mere curiosity, as in the tale of Pandora, but the more potent passion of revenge or, rather, of that vengeful retribution of the lex talionis which is the primitive image of justice. In an intimate fashion, too, the story gives us the spirit of Kenaima at work, while its denouement suggests that the restless Orehu, the Woman of the Waters, may be none other than the authoress of evil, the liberatress of ills.

In a time long past, so long past that even the grandmothers of our grandmothers were not yet born, the Caribs of Surinam say, the world was quite other than what it is today : the trees were forever in fruit; the animals lived in perfect harmony, and the little agouti played fearlessly with the beard of the jaguar; the serpents had no venom; the rivers flowed evenly, without drought or flood; and even the waters of cascades glided gently down from the high rocks. No human creature had as yet come into life, and Adaheli, whom now we invoke as God, but who then was called the Sun, was troubled. He descended from the skies, and shortly after man was born from the cayman, born, men and women, in the two sexes. The females were all of a ravishing beauty, but many of the males had repellent features; and this was the cause of their dispersion, since the men of fair visage, unable to endure dwelling with their ugly fellows, separated from them, going to the West, while the hideous men went to the East, each party taking the wives whom they had chosen.

Now in the tribe of the handsome Indians lived a certain young man, Maconaura, and his aged mother. The youth was altogether charming tall and graceful, with no equal in hunting and fishing, while all men brought their baskets to him for the final touch; nor was his old mother less skilled in the making of hammocks, preparation of cassava, or brewing of tapana. They lived in harmony with one another and with all their tribe, suffering neither from excessive heat nor from foggy chill, and free from evil beasts, for none existed in that region.

One day, however, Maconaura found his basket-net broken and his fish devoured, a thing such as had never happened in the history of the tribe; and so he placed a woodpecker on guard when next he set his trap; but though he ran with all haste when he heard the toe! toe! of the signal, he came too late; again the fish were devoured, and the net was broken. With cuckoo as guard he fared better, for when he heard the pon! pon! which was this bird's signal, he arrived in time to send an arrow between the ugly eyes of a cayman, which disappeared beneath the waters with a glou! glou! Maconaura repaired his basket-net and departed, only to hear again the signal, pon! pon! Returning, he found a beautiful Indian maiden in tears. "Who are you?" he asked. "Anuanaitu," she replied. "Whence come you?" "From far, far." "Who are your kindred?" "Oh, ask me not that!" and she covered her face with her hands.

The maiden, who was little more than a child, lived with Maconaura and his mother; and as she grew, she increased in beauty, so that Maconaura desired to wed her. At first she refused with tears, but finally she consented, though the union lacked correctness in that Maconaura had not secured the consent of her parents, whose name she still refused to divulge. For a while the married pair lived happily until Anuanaitu was seized with a great desire to visit her mother; but when Maconaura would go with her, she, in terror, urged the abandonment of the trip, only to find her husband so determined that he said, "Then I will go alone to ask you in marriage of your kin." "Never, never that!" cried Anuanaitu; "That would be to destroy us all, us two and your dear mother!" But Maconaura was not to be dissuaded, for he had consulted a peaiman who had assured him that he would return safely; and so he set forth with his bride.

After several weeks their canoe reached an encampment, and Anuanaitu said: "We are arrived; I will go in search of my mother. She will bring to you a gourd filled with blood and raw meat, and another filled with beltiri [a fermented liquor] and cassava bread. Our lot depends on your choice." The young man, when his mother-in-law appeared, unhesitatingly took the beltiri and bread, whereupon the old woman said, "You have chosen well; I give my consent to your marriage, but I fear that my husband will oppose it strongly." Kaikoutji ("Jaguar") was the husband's name. The two women went in advance to test his temper toward Maconaura's suit; but his rage was great, and it was necessary to hide the youth in the forest until at last Kaikoutji was mollified to such a degree that he consented to see the young man, only to have his anger roused again at the sight, so that he cried, "How dare you approach me?" Maconaura responded: "True, my marriage with your daughter is not according to the rites. But I am come to make reparation. I will make for you whatever you desire." "Make me, then," cried the other contemptuously, "a halla [sorcerer's stool] with the head of a jaguar on one side and my portrait on the other." By midnight Maconaura had completed the work, excepting for the portrait; but here was a difficulty, for Kaikoutji kept his head covered with a calabash, pierced only with eye-holes; and when Maconaura asked his wife to describe her parent, she replied: "Impossible! My father is a peaiman; he knows all; he would kill us both." Maconaura concealed himself near the hammock of his father-in-law, in hopes of seeing his face; and first, a louse, then, a spider, came to annoy Kaikoutji, who killed them both without showing his visage. Finally, however, an army of ants attacked him furiously, and the peaiman, rising up in consternation, revealed himself his whole horrible head. Maconaura appeared with the halla, completed, when morning came. "That will not suffice," said Kaikoutji, "in a single night you must make for me a lodge formed entirely of the most beautiful feathers."

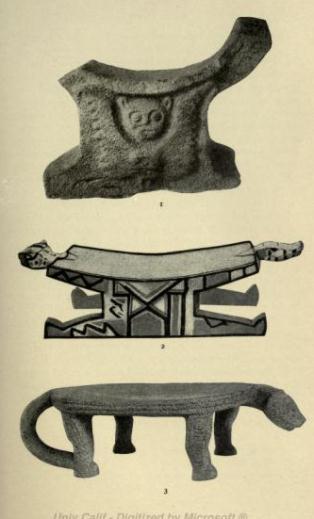

PLATE XXXIX: 1. Stone seat from Manabi, Ecuador. See page 206. After Saville, Antiquities of Manabi, Ecuador, Vol. II, Plate XXXVIII.

2. Painted wooden seat from Guiana such a holla as is referred to in the tale of Maconaura and Anuanaitu, page 264. After 30 ARBE, Plate V.

3. Central American carved stone metate in the collection of Geo. S. Walsh, Lincoln, Neb.

The young man felt himself lost, but multitudes of humming-birds and jacamars and others of brilliant plumage cast their feathers down to him, so that the lodge was finished before daybreak, whereupon Maconaura was received as the recognized husband of Anuanaitu.

The time soon came, however, when he wished again to see his mother, but as Kaikoutji refused to allow Anuanaitu to accompany the youth, he set off alone. Happy days were spent at home, he telling his adventures, the mother recounting the tales of long ago which had been dimly returning to her troubled memory; and when Maconaura would return to his wife, the old mother begged him to stay, while the peaiman warned him of danger; but he was resolved and departed once more, telling his mother that he would send her each day a bird to apprise her of his condition: if the owl came, she would know him lost. Arrived at the home of Anuanaitu, he was met by his wife and mother-in-law, in tears, with the warning: "Away! quickly! Kaikoutji is furious at the news he has received!" Nevertheless Maconaura went on, and at the threshold of the lodge was met by Kaikoutji, who felling him with a blow, thrust an arrow between his eyes. Meantime Maconaura's mother had been hearing daily the mournful bouta! bouta! of the otolin; but one day this was succeeded by the dismal popopo! of the owl, and knowing that her son was dead, she, led by the bird of ill tidings, found first the young man's canoe and then his hidden body, with which she returned sadly to her own people.

The men covered the corpse with a pall of beautiful feathers, placing about it Maconaura's arms and utensils; the women prepared the tapana for the funeral feast; and all assembled to hear the funeral chant, the last farewell of mother to son. She recounted the tragic tale of his love and death, and then, raising the cup of tapana to her lips, she cried: "Who has extinguished the light of my son? Who has sent him into the valley of shades? Woe ! woe to him ! . . . Alas ! you see in me, O friends and brothers, only a poor, weak old woman. I can do nothing. Who of you will avenge me? " Forthwith two men sprang forward, seized the cup, and emptied it; beside the corpse they intoned the Kenaima song, dancing the dance of vengeance; and into one of them the soul of a boa constrictor entered, into the other that of a jaguar.

The great feast of tapana was being held at the village of Kaikoutji, where hundreds of natives were gathered, men, women, and children. They drank and vomited; drank and vomited again; till finally all were drunken. Then two men came, one in the hide of a jaguar, the other in the mottled scales of a boa constrictor; and in an instant Kaikoutji and all about him were struck down, some crushed by the jaguar's blows, others strangled in snaky folds. Nevertheless fear had rescued some from their drunkenness; and they seized their bows, threatening the assailants with hundreds of arrows, whereupon the two Kenaima ceased their attack, while one of them cried: "Hold, friends! we are in your hands, but let us first speak!" Then he recounted the tale of Maconaura, and when he had ceased, an old peaiman advanced, saying: "Young men, you have spoken well. We receive you as friends."

The feast was renewed more heartily than ever, but though Anuanai'tu, in her grief, had remained away, she now advanced, searching among the corpses. She examined them, one by one, with dry eyes; but at last she paused beside a body, her eyes filled with tears, and seating herself, long, long she chanted plaintively the praises of the dead. Suddenly she leaped up, with hair bristling and with face of fire, in vibrant voice intoning the terrible Kenaima; and as she danced, the soul of a rattlesnake entered into her.

Meantime, in the other village, the people were celebrating the tapana, delirious with joy for the vengeance taken, while the mother of Maconaura, overcome by drink, lay in her hammock, dreaming of her son. Anuanai'tu entered, possessed, but she drew back moved when she heard her name pronounced by the dreaming woman: "Anuanai'tu, my child, you are good, as was also your mother! But why come you hither? My son, whom you have lost, is no more . . . O son Maconaura, rejoice ! Thou art happy, now, for thou art avenged in the blood of thy murderers! Ah, yes, thou art well avenged!" During this Anuanaitu felt in her soul a dread conflict, the call of love struggling with the call of duty; but at the words, "avenged in blood," she restrained herself no longer, and throwing herself upon the old woman, she drew her tongue from her mouth, striking it with venomous poison; and leaning over her agonized victim, she spoke: "The cayman which your son killed beside the basket-net was my brother. Like my father, he had a cayman's head. I would pardon that. My father avenged his son's death in inflicting on yours the same doom that he had dealt an arrow between the eyes. Your kindred have slain my father and all mine. I would have pardoned that, too, had they but spared my mother. Maconaura is the cause that what is most dear to me in the world is perished; and robbing him in my turn, I immolate what he held most precious!"

Uttering a terrible cry, she fled into the forest; and at the sound a change unprecedented occurred throughout all nature. The winds responded with a tempest which struck down the trees and uprooted the very oaks; thick clouds veiled the face of Adaheli, while sinister lightnings and the roar of thunders filled the tenebrous world; a deluge of rain mingled with the floods of rivers. The animals, until then peaceable, fell upon and devoured one another: the serpent struck with his venom, the cayman made his terrible jaws to crash, the jaguar tore the flesh of the harmless agouti. Anuanaitu, followed by the savage hosts of the forest, pursued her insensate course until she arrived at the summit of an enormous rock, whence gushed a cascade; and there, on the brink of the precipice, she stretched forth her arms, leaned forward, and plunged into the depths. The waters received her and closed over her; nought was to be seen but a terrifying whirlpool.

If today some stranger pass beside a certain cascade, the Carib native will warn him not to speak its name. That would be his infallible death, for at the bottom of these waters Maconaura and Anuana'itu dwell together in the marvellous palace of her who is the Soul of the Waters.

It is not merely the artistic symmetry of this tale which may be due as much to the clever rendering by Father van Coll as to the genius of the savage raconteur that justifies giving it at length. It is a wonderfully instructive picture of savage life, emotions, and customs; and a full commentary upon it would lead to an exposition of most that we know of the customs and thought of the Orinoco aborigines such practices, for example, as ini Thurn describes: the putting of red pepper in one's eyes to propitiate the spirits of rapids one is about to shoot; the method of Kenaima murder by pricking the tongue with poison; the perpetual vendetta which to the savage seems to hold not only between tribe and tribe of men, but also between tribe and tribe of animals; the tapana feasts in which men become inspired; or again, such mythic and religious conceptions as the cult of the jaguar and cayman, extending far throughout South and Central America; the still more universal notion of a community of First People, part man, part animal; the ominous birds and animal helpers; the central story of the visit of the hero-youth to the ogreish father-in-law, and of the trials to which he is subjected. In these and in other respects the story is of interest; but its chief attraction is surely in the fact that here we have an American Job presenting, as Job presents, the problem of evil; and, like Greek tragedy, portraying the harsh conflict between the inexorable justice of the law of retribution and the loves and mercies which combat it, in the savage heart perhaps not less than in the civilized.

IV. CREATION AND CATACLYSM

Both creation and cataclysm appear in the story of Maconaura and Anuanaitu, but this legend is only one among several tales of the kind gathered from various groups of Orinoco natives, the fullest collection, "'old peoples' stories,' as the rising race somewhat contemptuously call them," being given by Brett. The creation myths are of the two familiar American types: true creations out of the void, and migrations of First Beings into a new land; while transformation-incidents, and especially the doughty deeds of the Transformer-Hero, a true demiurge, are characteristic of traditions of each type.

The Ackawoi make their Makonaima the creator, and Sigu, his son, the hero, in a tale which, says Brett, 11 they repeat "while striving to maintain a very grave aspect, as befitting the general nature of the subject." "In the beginning of this world the birds and beasts were created by Makonaima, the great spirit whom no man hath seen. They, at that time, were all endowed with the gift of speech. Sigu, the son of Makonaima, was placed to rule over them. All lived in harmony together and submitted to his gentle dominion." Here we have the usual sequence: the generation of the world, followed by the Golden Age, with its vocal animals and universal peace; while as a surprise to his subject creatures, Makonaima caused a wonderful tree, bearing all good fruits, to spring from the earth the tree which was the origin of all cultivated plants. The acouri first discovered this tree, selfishly trying to keep the secret to himself; and the woodpecker, set by Sigu to trace the acouri, proved a poor spy, since his tapping warned it of his presence; but when the rat solved the mystery, Sigu determined to fell the tree and plant its fruits broadcast. Only the lazy monkey refused to assist, and even mischievously hindered the others, so that Sigu, provoked, put him at the task of the Danai'des to fetch water in a basket-sieve. The stump of the tree proved to be filled with water, stocked with every kind of fish and from its riches Sigu proposed to supply all streams; but the waters began of themselves to flow so copiously that he was compelled hastily to cover the top with a basket which the mischievous monkey discovered; and raising it, the deluge poured forth. To save the animals, Sigu sealed in a cave those which could not climb; the others he took with him into a high cocorite tree, where they remained through a long and uncomfortable night, Sigu dropping cocorite seeds from time to time to judge by the splash if the waters were receding, until finally the sound was no longer heard, and with the return of day the animals descended to repeople the earth. But they were no longer the same. The arauta still howls his discomfort from the trees; the trumpeter-bird, too greedily descending into the food-rich mud, had his legs, till then respectable, so devoured by ants that they have ever since been bonily thin; the bush-fowl snapped up the spark of fire which Sigu laboriously kindled, and got his red wattle for his greed; while the alligator had his tongue pulled out for lying (it is a common belief that the cayman is tongueless). Thus the world became what it is.

A second part of the tale tells how Sigu was persecuted by two wicked brothers who beat him to death, burned him to ashes, and buried him. Nevertheless, each time he rose again to life and finally ascended a high hill which grew upward as he mounted until he disappeared in the sky.

Probably the most far-known mythic hero of this region is Amalivaca, a Carib demiurge, concerning whom Humboldt reports various beliefs of the Tamanac (a Cariban tribe). According to Humboldt, 12 "the name Amalivaca is spread over a region of more than five thousand square leagues; he is found designated as 'the father of mankind,' or 'our great-grand-father' as far as the Caribbee nations"; and he likens him to the Aztec Quetzalcoatl. It is in connexion with the petroglyphs of their territory (similar rock-carvings are found far into the Antilles, the "painted cave" in which the Earth God- dess was worshipped in Haiti being, no doubt, an example) that the Tamanac give motive to their tale. Amalivaca, father of the Tamanac, arrived in a canoe in the time of the deluge, and he engraved images, still to be seen, of the sun and the moon and the animals high upon the rocks of Encaramada.

From this deluge one man and one woman were saved on a mountain called Tamancu the Tamanac Ararat and "casting behind them, over their heads, the fruits of the mauritia palm-tree, they saw the seeds contained in those fruits produce men and women, who repeopled the earth." After many deeds, in which Amalivaca regulated the world in true heroic fashion, he departed to the shores beyond the seas, whence he came and where he is supposed still to dwell.

Another myth, of the Cariban stock, 13 tells how Makonaima, having created heaven and earth, sat on a silk-cotton-tree by a river, and cutting off pieces of its bark, cast them about, those which touched the water becoming fish, and others flying in the air as birds, while from those that fell on land arose animals and men. Boddam-Whetham gives a later addition, accounting for the races of men: "The Great Spirit Makanaima made a large mould, and out of this fresh, clean clay the white man stepped. After it got a little dirty the Indian was formed, and the Spirit being called away on business for a long period the mould became black and unclean, and out of it walked the negro." As in case of other demiurges, there are many stories of the transformations wrought by Makonaima.

It is from the Warau that Brett obtains a story of a descent from the sky-world a tale which has many replications in other parts of America, and of which there are other Orinoco variants. Long ago, when the Warau lived in the happy hunting-grounds above the sky, Okonorote, a young hunter, shot an arrow which missed its mark and was lost; searching for it, he found a hole through which it had fallen; and looking down, he beheld the earth beneath, with game-filled forests and savannahs. By means of a cotton rope he visited the lands below, and upon his return his reports were such as to induce the whole Warau tribe to follow him thither; but one unlucky dame, too stout to squeeze through, was stuck in the hole, and the Warau were thus prevented from ever returning to the sky-world. Since the lower world was exceedingly arid, the great

Spirit created a small lake of delicious water, but forbade the people to bathe in it this to test their obedience. A certain family, consisting of four brothers Kororoma, Kororomana, Kororomatu, and Kororomatitu and two sisters Korobona and Korobonako dwelt beside this mere; the men obeyed the injunction as to bathing, but the two sisters entered the water, and one of them swimming to the centre of the lake, touched a pole which was planted there. The spirit of the pool, who had been bound by the pole, was immediately released; and seizing the maiden, he bore her to his sub-aquatic den, whence she returned home pregnant; but the child, when born, was normal and was allowed to live. Again she visited the water demon and once more brought forth a child, but this one was only partly human, the lower portion of the body being that of a serpent. The brothers slew the monster with arrows; but after Korobona had nursed it to life in the concealment of the forest, the brothers, having discovered the secret, again killed the serpent-being, this time cutting it in pieces. Korobona carefully collected and buried all the fragments of her offspring's body, covering them with leaves and vegetable mould; and she guarded the grave assiduously until finally from it arose a terrible warrior, brilliant red in colour, armed for battle, this warrior being the first Carib, who forthwith drove from their ancient hunting-grounds the whole Warau tribe.

This myth contains a number of interesting features. It is obviously invented in part to explain why the Warau (who are execrated by whites and natives alike for their dirtiness) do not bathe; and it no doubt reflects their actual yielding before the invading Carib tribes. The Kororomana of the story can scarcely be other in origin that the Kururumany whom Schomburgk states to be the Arawak creator; while the whole group of four brothers are plausibly continental forms of the Haitian Caracarols, the shell-people who brought about the flood. The incident of the corpulent or pregnant woman (im Thurn gives the latter version) stopping the egress of the primitive people from their first home appears in Kiowa, Mandan, and Pueblo tales in North America; while the pole rising from the lake has analogues in the Californian and North-West Coast regions. Im Thurn states that the Carib have a variant of this same story, in which they assign as the reason for the descent of their forefathers from Paradise their desire to cleanse the dirty and disordered world below an amusing complement to the Warau notion!

The Warau have also their national hero, Abore, who has something of the character of a true culture hero. Wowta, the evil Frog-Woman, made Abore her slave while he was yet a boy, and when he grew up, she wished to marry him; but he cleverly trapped her by luring her into a hollow tree filled with honey, of which she was desperately fond, and there wedging her fast. He then made a canoe and paddled to sea to appear no more, though the Warau believe that he reached the land of the white men and taught them the arts of life; Wowta escaped from the tree only by taking the form of a frog, and her dismal croaking is still heard in the woods.

From the tribes of this region come various other myths, belonging, apparently, to the cosmogonic and demiurgic cycles. The Arawak tell of two destructions of the earth, once by flame and once by fire, each because men disobeyed the will of the Dweller-on-High, Aiomun Kondi; and they also have a Noachian hero, Marerewana, who saved himself and his family during the deluge by tying his canoe with a rope of great length to a large tree. Another Arawak tale begins with the incident which opens the story of Maconaura. The Sun built a dam to retain the fish in a certain place; but since, during his absence, it was broken, so that the fish escaped, he set the Woodpecker to watch, and, summoned by the bird's loud tapping, arrived in time to slay the alligator that was destroying his preserves, the reptile's scales being marks made by the club wielded by the Sun. Another tale, of which there are both Arawak and Carib versions, tells how a young man married a vulture and lived in the sky-land, revisiting his own people by means of a rope which the spiders spun for him; but as the vultures would thereafter have nothing to do with him, with the aid of other birds he made war upon them and burned their settlement. In this combat the various birds, by injury or guile, received the marks which they yet bear; the owl found a package which he greedily kept to himself; opening it, the darkness came out, and has been his ever since. In the Surinam version, given by van Coll, 14 the hero of the tale is a peaiman, Maconaholo, and the story contains some of the incidents of the Maconaura tale. Two other traditions given by the same author are of special interest from the comparative point of view. One is the legend of an anchorite who had a wonderfully faithful dog. Wandering in the forest, the hermit discovered a finely cultivated field, with cassava and other food plants, and thinking, "Who has prepared all this for me?" he concealed himself in order to discover who might be his benefactor, when behold! his faithful dog appeared, transformed herself into a human being, laid aside her dog's skin, busied herself with the toil of cultivation, and, the task accomplished, again resumed her canine form. The native, carefully preparing, concealed himself anew, and when the dog came once more, he slyly stole the skin, carried it away in a courou-courou (a woman's harvesting basket), and burned it, after which the cultivator, compelled to retain woman's form, became his faithful wife and the mother of a large family. It would appear that, from an aboriginal point of view, both dog and woman are complimented by this tale.

The second tale of special interest is a Surinam equivalent of the story of Cain and Abel. Of three brothers, Halwanli, the eldest, was lord of all things inanimate and irrational; Ourwanama, the second, was a tiller of fields, a brewer of liquors, and the husband of two wives; Hiwanama, the youngest, was a huntsman. One day Hiwanama, chancing upon the territory of Ourwanama, met one of his brother's wives, who first intoxicated him and then seduced him, while in revenge for this injury Ourwanama banished his brother, lying to his mother when she demanded the lost son. Afterward Ourwanama's wives were transformed, the one into a bird, the other into a fish; he himself, seized by the sea, was dragged to its depth; and the desolate mother bemoaned her lost children till finally Halwanli, going in search of Hiwanama, whom he found among the serpents and other reptiles of the lower world, brought him back to become the greatest of peaimen.

V. NATURE AND HUMAN NATURE

A missionary whom Humboldt quotes declares that a native said to him: 15 "Your God keeps himself shut up in a house, as if he were old and infirm; ours is in the forest, in the fields, and on the mountains of Sipapu, whence the rains come"; and Humboldt remarks in comment that the Indians conceive with difficulty the idea of a temple or an image: "on the banks of the Orinoco there exists no idol, as among all the nations who have remained faithful to the first worship of nature."

There is an echo of the eighteenth century philosophy of an idyllic primitive age in this statement, but there is truth in it, too; for throughout the forest regions of tropical America idols are of rare occurrence, while shrines, if such they may be called, are confined to places of natural marvel, the wandering tribes being true nature worshippers, with eyes ever open for tokens of mysterious power. Fetishes or talismans are, however, common; and in this very connexion Humboldt mentions the botuto, or sacred trumpet, as an object of veneration to which fruits and intoxicating liquors were offered; sometimes the Great Spirit himself makes the botuto to resound, and, as in so many other parts of the world, women are put to death if they but see this sacrosanct instrument or the ceremonies of its cult (and here we are in the very presence of Mumbo Jumbo!). Certainly the use of the fetish-trumpet was widespread in South America and northward. Garcilasso tells of the use of dog-headed battle-trumpets by the wild tribes of Andean regions; while Boddam-Whetham affords us another indication of the trumpet's significance: 16 "Horn-blowing was a very useful accomplishment of our guide, as it kept us straight and frightened away the various evil spirits, from a water-mama to a wood-demon."

This latter author gives a vivid picture of the Orinoco Indian in the life of nature: "Above all other localities, an Indian is fond of an open, sandy beach whereon to pass the night. . . . There in the open, away from the dark, shadowy forest, he feels secure from the stealthy approach of the dreaded 'kanaima'; . . . the magic rattle of the 'peaiman' . . . has less terror for him when unaccompanied by the rustling of the waving branches; and there even the wild hooting of the 'didi' (the Midi' is supposed to be a wild man of the woods, possessed of immense strength and covered with hair) is bereft of that intensity with which it pierces the gloomy depths of the surrounding woodland. It is strange that the superstitious fear of these Indians, who are bred and born in the forest and hills, should be chiefly based on natural forms and sounds. Certain rocks they will never point at with a finger, although your attention may be drawn to them by an inclination of the head. Some rocks they will not even look at, and others again they beat with green boughs. Common bird-cries become spirit-voices. Any place of difficult access, or little known, is invariably tenanted by huge snakes or horrible four-footed animals. Otters are transformed into mermaids, and water-tigers inhabit the deep pools and caves of their rivers."

This is the familiar picture of the animist, surrounded by monster-haunted marches, for which, in the works of many writers, the Guiana aborigines have afforded the repeated model. No description of the beliefs of these natives would be complete without mention of the superstitions and adorations associated with Mt. Roraima, by which all travellers seem to be impressed. Schomburgk 17 says that the native loves Roraima as the Swiss loves his Alps: "All their festal songs have Roraima for object. . . . Each morning and each evening came old and young ... to greet us with bakong baimong ('good day') or saponteng ('good night') . . . adding each time the words, matti Roraima-tau, Roraima-tau ('there, see our Roraima!'), with the word tau very slowly and solemnly drawled"; and one of their songs, which might be a fragment out of the Greek, runs:

"Roraima of the red rocks, wrapped in clouds, ever-fertile source of streams!"

On Roraima, says im Thurn, the natives declare there are huge white jaguars, white eagles, and other such creatures; and to this class he would add the "didis," half man, half monkey, who may very likely be a mere personification of the howling monkeys which, as Humboldt states, the aborigines so heartily detest. Boddam-Whetham, who ascended the mountain, tells of many superstitions, as of a magic circle which surrounds it, and of a demon-guarded sanctuary on the summit: "About half way up we met an unpleasant-looking Indian who informed us that he was a great 'peaiman,' and the spirit which he possessed ordered us not to go to Roraima. The mountain, he said, was guarded by an enormous 'camoodi,' which could entwine a hundred people in its folds. He himself had once approached its den and seen demons running about as numerous as quails. . . . Our Indians were rejoiced to see us back again, as they had not expected that the mountain-demons would allow us to return."

Like great mountains, the orbs of heaven excite the native's adoration, though it is by no means necessary, on that account, to follow certain theorists and to solarize or astralize all his myths. Fray Ruiz Blanco states that "the supreme gods of the Indians are the sun and the moon, at eclipses of which they make great demonstrations, sounding warlike instruments and laying hold of weapons as a sign that they seek to defend them; they water their maize in order to placate them and in loud voice tell them that they will amend their ways, labour, and not be idle; and grasping their tools, they set themselves to toil at the hour of eclipse." Of similar reference is an observation of Humboldt's: "Some Indians who were acquainted with Spanish, assured us that zis signified not only the sun, but also the Deity. This appeared to me the more extraordinary since among all other American nations we find distinct words for God and the sun. The Carib does not confound Tamoussicabo, 'the Ancient of Heaven,' with veyou, 'the sun." In a similar connexion he remarks that in American idioms the moon is often called "the sun of night," or "the sun of sleep"; but that "our missionary asserted that jama, in Maco, indicated at the same time both the Supreme Being and the great orbs of night and day; while many other American tongues, for instance Tamanac and Caribbee, have distinct words to designate God, the Moon, and the Sun." It is, of course, quite possible that such terms as zis and jama belong to the class of Manito, Wakan, Huaca, and the like.

Humboldt records names for the Southern Cross and the Belt of Orion, and Brett mentions a constellation called Camudi from its fancied resemblance to the snake, though he does not identify it. The Carib, he says, call the Milky Way by two names, one of which signifies "the path of the tapir," while the other means "the path of the bearers of white clay" a clay from which they make vessels: "The nebulous spots are supposed to be the track of spirits whose feet are smeared with that material " a conceit which surely points to the wellnigh universal American idea of the Milky Way as the path of souls. The Carib also have names for Venus and Jupiter; and the Macusi, im Thurn says, regard the dew as the spittle of stars.

In a picturesque passage Humboldt describes the beliefs connected with the Grotto of Caripe, the source of the river of the same name. The cave is inhabited by nocturnal birds, guacharos (Steatornis caripensis) ; and the natives are con- vinced that the souls of their ancestors sojourn in its deep recesses. "Man," they say, "should avoid places which are enlightened neither by the sun nor by the moon"; and they maintain that poisoners and magicians conjure evil spirits before the entrance; while "to join the guacharos" is a phrase equivalent to being gathered to one's fathers in the tomb. Fray Ruiz records an analogous tenet: "They believe in the immortality of the soul and that departing from the body, it goes to another place some souls to their own lands (heredades}, but the most to a lake that they call Machira, where great serpents swallow them and carry them to a land of pleasure in which they entertain themselves with dancing and feasting." That ghosts of strong men return is an article of common credence: the soul of Lope de Aguirre, as reported not only by Humboldt, but by writers of our own day, 18 still haunts the savannahs in the form of a tongue of flame; and it may be supposed that the similar idea which Boddam-Whetham records among the negroes of Martinique with respect to the soul of Pere Labat may be of American Indian origin. One striking statement, which Brett quotes from a Mr. McClintock, deserves repetition, as being perhaps as clear a statement as we have of that ambiguity of life and death, body and soul, from which the savage mind rarely works itself free: "He says that the Kapohn or Acawoio races (those who have embraced Christianity excepted) like to bury their dead in a standing posture, assigning this reason, 'Although my brother be in appearance dead, he (i. e. his soul) is still alive.' Therefore, to maintain by an outward sign this belief in immortality some of them bury their dead erect, which they say represents life, whereas lying down represents death. Others bury their dead in a sitting posture, assigning the same reason." It is unlikely that the Orinoco Indians have in mind such clear-cut symholism of their custom as this passage suggests; but it is altogether probable that the true reason for disposing the bodies of the dead in life-like postures is man's fundamental difficulty wholly to dissociate life from the stark and unresponsive body; and doubtless it is this very attitude of mind which leads them also to what Fray Ruiz calls the error of ascribing souls to even irrational beings the same underlying theory which makes of primitive men animists, and of philosophers idealists.

NOTES

1. The argument for the antiquity of man in South America rests mainly upon the discoveries and theories of Ameghino, especially, La Antigiiedad del hombre en la Plata (2 vols., Buenos Aires and Paris, 1880) and artt. in AnMB, who is followed by other Argentinian savants. Ales Hrdlicka, Early Man in South America (52 BBE, Washington, 1912), examines the claims made for the several discoveries and uniformly rejects the assumption of their great age, in which opinion he is generally followed by North American anthropologists; as cf. Wissler, The American Indian (New York, 1917). The theory favored by Hrdlicka and others is of the peopling of the Americas by successive waves of immigrants from north-eastern Asia, with possible minor intrusions of Oceanic peoples along the Pacific coasts of the southern continent.

2. The sketch of South American ethnography in d'Orbigny's UHomme americain is, of course, now superseded in a multitude of details; it appears, however, to conform, in broad lines, to the deductions of later students. In addition to d'Orbigny and Schmidt (ZE xlv, 1913), Brinton, The American Race, Beuchat, Manuel, and Wissler, The American Indian, present the most available ethnographic analyses.

3. "Linguistic Stocks of South American Indians," in A A, new series, xv (1913); also, Wissler, The American Indian, pp. 381-85, listing eighty-four stocks. It must be borne in mind, however, that the tendency of minute study is eventually to diminish the number of linguistic stocks having no detectable relationships, and that, in any case, classifications based upon cultural grade are more important for the student of mythology than are those based upon language alone.

4. Brett [a], p. 36; other quotations from this work are from pp. 374, 401, 403.

5. King Blanco, pp. 63-64. The lack of significant early authorities for the mythologies of the region of Guiana and the Orinoco (Gumilla is as important as any) is compensated by the careful work of later observers of the native tribes, especially of Guiana. Among these, Humboldt, Sir Richard and Robert H. Schomburgk, and Brett, in the early and middle years of the nineteenth century, and im Thurn, at a later period, hold first place, while the contributions of van Coll, in Anthropos ii, iii (1907, 1908), are no less noteworthy. Latest of all is Walter Roth's " Inquiry into the Animism and Folk-Lore of the Guiana Indians," in 30 ARBE (1915), which, as a careful study of the myth-literature of a South American group, stands in a class by itself; it is furnished with a careful bibliography. The reader will understand that the intimate relation between the Antillean and Continental Carib (and, to a less extent, Arawakan) ideas brings the subject-matter of this chapter into direct connexion with that of Chapter I; while it should also be obvious that the Orinoco region is only separated from the Amazonian for convenience, and that Chapter X is virtually but a further study of the same level and type of thought. The bibliographies of Chh. I, VI, and X are supplementary, for this same region, to that given for Chapter VIII.

6. Humboldt [b] (Ross), iii. 69; im Thurn, pp. 365-66.

7. Surely one may indulge a wry smile when told that "heavenly father" and "creator" are no attributes of God, and may be reasonably justified in preferring Sir Richard Schomburgk's judgment, where he says (i. 170): "Almost all stocks of British Guiana are one in their religious convictions, at least in the main; the Creator of the world and of mankind is an infinitely exalted being, but his energy is so occupied in ruling and maintaining the earth that he can give no special care to individual men." This unusual reason for the indifference of the Supreme Being toward the affairs of ordinary men is probably an inference of the author's. Roth commences his study of Guiana Indian beliefs with a chapter entitled, "No Evidence of Belief in a Supreme Being," and begins his discussion with the statement: "Careful investigation forces one to the conclusion that, on the evidence, the native tribes of Guiana had no idea of a Supreme Being in the modern conception of the term," quoting evidence, from Gumilla and others, which to the present writer seems to point in just the opposite direction. Of course, the phrase "in the modern conception of the term" is the key to much difference in judgement. If it means that savages have no conception of a Divine Ens, Esse, Actus Purus, or the like, definable by highly abstract attributes, (a va sans dire; but if the intention is to say that there is no primitive belief in a luminous Sky Father, creator and ruler, good on the whole, though not preoccupied with the small details of earthly and human affairs, such a conclusion is directly opposed to all evidence, early and late, North American and South American, missionary and anthropological. Cf. Mythology of All Races, x. Note 6, and references there given; and, in the present volume, not only Ch. I, iii (Ramon Pane is surely among the earliest), but also passing over the numerous allusions in descriptions of the pantheons of the more advanced tribes (Chh. II-VII) Ch. IX, iii (early and late for the low Brazilian tribes); Ch. X, ii, iii, iv.

8. Sir Richard Schomburgk, ii. 319-20; i. 170-72. Roth gives legends from many sources touching these deities and others of a similar character.

9. Humboldt [b] (Ross), ii. 362.

10. This tale is translated and abridged from van Coll, in Anthropos, ii, 682-89; Roth, chh. vii, xviii, affords an excellent commentary.

11. Brett [a], ch. x, pp. 377-78.

12. Humboldt [b] (Ross), ii. 182-83, 473~75 Descriptions of the petroglyphs are to be found in Sir Richard Schomburgk, i. 319-21, and im Thurn, ch. xix.

13. Boddam-Whetham, Folk-Lore, v. 317 (im Thurn, p. 376, misquoting Brett, calls this an Arawakan tale); for other creation leg-ends, see Roth, ch. iv.

14. Van Coll, Anthropos, iii. 482-86.

15. Humboldt [b] (Ross), iii. 362-63; other citations from Humboldt in this section are, id. op., iii. 70; ii. 321 ; iii. 293, 305; ii. 259-60, in order.

16. Boddam-Whetham, F oik-Lore, v. 317-21.

17. Sir Richard Schomburgk, i. 239-41; im Thurn, p. 384. Other quotations are from Ruiz Blanco, pp. 66-67; Brett [a], pp. 278, 107, 356.

18. For contemporary beliefs about Lope de Aguirre, see Mozans (J. A. Zahm), [a], pp. 264-67.