|

|

Latin American Mythology

By Hartley Burr Alexander

CHAPTER IV: YUCATAN

I The Maya

II Votan, Zamna, and Kukulcan

III Yucatec Deities

IV Rites and Symbols

V The Maya Cycles

VI The Creation

I. THE MAYA

NATIVE American civilization attained its apogee among the Maya. This is not true in a political sense, for, though at the time of the Conquest the Maya remembered a past political greatness, there is no reason to believe that it had ever been, either in power or in organization, a rival of such states as the Aztec and Inca. The Mayan cities had been confederate in their unions rather than national, aristocratic in their governments rather than monarchic ; and in their greatest unity the power of their strongest rulers, the lords of Mayapan, appears to have been that of feudal suzerains, or at best of insecure tyrants. Politically the Mayan cities present somewhat the aspect of the loose-leaguing Hellenic states, and it is not without probability that in each case the looseness of the political organization was directly conducive to the intense civic pride which undoubtedly in each case fostered an extraordinary development of the arts. For in all the more intellectual tokens of culture in art, in mathematics, in writing, and in historical records the Mayan peoples surpassed all other native Americans, leaving in the ruins of their cities and in the profusion of their sculptured monuments such evidences of genius as only the most famous centres of Old- World antiquity can rival.

The territories of the Mayan stock are singularly compact. 1 They occupied and their descendants now occupy the Peninsula of Yucatan, the valley of the Usumacinta, and the Cordillera rising westerly and sinking to the Pacific. The Rio Motagua, emptying into the Gulf of Honduras, and the Rio Grijalva, debouching into the Bay of Campeche, form respectively their south-eastern and western borders excepting for the fact that on the eastern coasts of Mexico, facing the Gulf of Campeche, the Huastec (and perhaps their Totonac neighbours) represent a Mayan kindred. Between this western branch and the great Mayan centre of Yucatan the coast was occupied by intrusive Nahuatlan tribes, landward from whom lay the territories of the Zoquean and Zapotecan stocks, the western neighbours of the Mayan peoples.

The culture of the Maya is distinctly related, either as parent or as branch, to the civilizations of Mexico. 2 Affinities of Haustec and Maya works of art indicate that the ancestors of the two branches were not separated previous to a considerable progress in civilization; while, in a broader way, the cultures of the Nahuatlan, Zapotecan, and Mayan peoples have common elements of art, ritual, myth, and, above all, of mathematical and calendric systems which mark them as sprung from a common source. The Zapotec, situated between the Nahuatlan and Mayan centres, show an intermediate art and science, whose elements clearly unite the two extremes; while the appearance of place-names, such as Nonoual and Tulan, or Tollan, in both Maya and Nahua tradition imply at least a remote geographical community. The Nahuatlan tribes, if we may believe their own account, were comparatively recent comers into the realm of a civilization long anteceding them, and one which they, as barbarians, adopted; the Maya (at least, mythically) remembered the day of their coming into Yucatan. On the basis of these two facts and the un- doubted community of culture of the two races, it has been not implausibly reasoned that the Toltec of Nahua tradition were in fact the ancestors of the Maya, who, abandoning their original home in Mexico, made their way to the peninsula, there to perfect their civilization; and the common association of Quetzalcoatl ("Kukulcan" in Maya) with the migration legends adds strength to this theory. Nevertheless, tradition points to the high antiquity of the southern rather than of the Mexican centres of civilization; and as the facts seem to be well explained by the assumption of a northern extension of Mayan culture in the Toltec or pre-Toltec age, followed by its recession in the period of its decline in 'the south, this may be taken as the more acceptable theory in the light of present knowledge. According to this view, the Nahua should be regarded as the late inheritors of an older civilization which they had gradually pushed back upon its place of origin and which, indeed, they were threatening still further at the time of the Conquest, for even then Nahuatlan tribes had forced them- selves among and beyond the declining Maya.

When the Spaniards reached Yucatan, its civilization was already decadent. The greater cities had been abandoned and were falling into decay, while the country was anarchical with local enmities. The past greatness of Mayapan and Chichen Itza was remembered; but rather, as Bishop Landa's account shows, 3 for the intensification of the jealousies of those who boasted great descent than as models for emulation. Three brothers from the east so runs the Bishop's narrative had founded Chichen Itza, living honourably until one of them died, when dissensions arose, and the two surviving brothers were assassinated. Either before this event, or immediately afterward, there arrived from the west a great prince named Cuculcan who, "after his departure, was regarded in Mexico as a god and was called Cezalcouati; and he was venerated as a divinity in Yucatan also because of his zeal for the public good." He quieted the dissensions of the people and founded the city of Mayapan, where he built a round temple, with four entrances opening to the four quarters, "entirely different from all those that are in Yucatan"; and after ruling in Mayapan for seven years he returned to Mexico, leaving peace and amity behind him. The family of the Cocomes succeeded to the rule, and shortly afterward came Tutul-Xiu and his followers, who had been wandering in the interior for forty years. These formed an alliance with Mayapan; but eventually the Cocomes, by intro- ducing Mexican mercenaries (who brought the bow, previously unknown there) were able to tyrannize over the people. Under the leadership of the Xius, rising in revolt, the Cocomes were overthrown, only one son out of the royal house escaping; and Mayapan, after five centuries of power, was abandoned.

PLATE XVIII: Temple 3, ruins of Tikal. After Memoirs of the Peabody Museum, Vol. V, Plate II.

The single Cocom who escaped gathered his followers and founded Tibulon calling his province Zututa, while the Mexican mercenaries settled at Canul. Achchel, a noble who had married the daughter of the Ahkin-Mai, chief priest of Mayapan and keeper of the mysteries, founded the kingdom of the Cheles on the coast; and the Xius held the inlands. "Between these three great princely houses of the Cocomes, Xivis, and Cheles there were constant struggles and cruel hatreds, and these endure even now that they have become Christians. The Cocomes say to the Xivis that they assassinated their sovereign and stole his domains; the Xivis reply that they are neither less noble nor less ancient and royal than the others, and that far from being traitors, they were the liberators of the country in slaying a tyrant. The Cheles, in turn, claim to be as noble as any, since they are descended from the most venerated priest of Mayapan. On another side, they mutually reviled each other in the matter of food, since the Cheles, dwelling on the coast, would not give fish or salt to the Cocomes, obliging them to send far for these, while the Cocomes would not permit the Cheles the game and fruits of their territory."

Such is the picture which Bishop Landa gives of the conditions in the north of the peninsula at the time of the Conquest, about a century after the fall of Mayapan; and native records and archaeology alike sustain its general truth. 4 At Chichen Itza the so-called Ball Court is regarded as Mexican in inspiration, while in the same city exist the ruins of a round temple similar to those which tradition ascribes to Kukulcan, different in character from the normal Mayan types. Reliefs >representing warriors in Mexican garb also point to Nahuatlan incursions, which may in fact have been the occasion for the dissolution of the Mayan league of the cities of the north Chichen Itza, Uxmal, and Mayapan in the Books of Chilam Balam represented as powerful in the day of the great among the Maya of Yucatan.

These "Books" are historical chronicles written after the Conquest by members of native families chiefly the TutulXiu and from them, as key events of Yucatec history, a few events stand forth so conspicuously that possible dates can be assigned to them. "This is the arrangement of the katuns [periods of 720x3 days] since the departure was made from the land, from the house of Nonoual, where were the four Tutul- Xiu, from Zuiva in the west; they came from the land of Tulapan, having formed a league." 5 So begins one of the chronicles, indicating a remote migration of the Xiu family from the west an event which Spinden and Joyce place near 160 A. D. 6 The next event recorded is a stay, eighty years later, at Chacnouiton (or Chacnabiton), where a sojourn of ninety-nine years is recorded; and thence the migration was renewed, Bakhalal, near the Gulf of Honduras, being occupied for some sixty years. Here it was that the wanderers "learned of," or discovered, Chichen Itza, and hither the people removed about the middle of the fifth century, only to abandon it after a century or more in order to occupy Chacanputun, on the Bay of Campeche. Two hundred and sixty years later this seat was lost, and the Itza returned, about the year 970 A. D., to Chichen Itza, while a member of the Tutul-Xiu founded Uxmal, these two cities joining with Mayapan to form the triple league which, for more than two centuries, was to bring peace and prosperity and the climax of its civilization to northern Yucatan. This happy condition was ended by "the treachery of Hunac Ceel," who introduced foreign warriors (Mexicans, as their names indicate) into Chichen Itza, overthrew its ruler, Chac Xib Chac, and caused a state of anarchy. For a brief period power centred in Mayapan, which ruled with something like order, until "by the revolt of the Itza" it also lost its position and was finally depopulated in 1442, this disaster being closely followed by plagues, wars, and a terrific storm, accompanied by inundation, all of which carried the destruction forward.

This reconstruction of northern Yucatec history, however, gives no clue to the origin or life of the cities of the south Palenque, Piedras Negras, and Yaxchilan in the lower central valley of the Usumacintla; Seibal on its upper reaches, not far from Lake Peten, near which are the ruins of Tikal and Naranjo; while, south-east of these, Copan, on the river of the same name, and Quirigua mark the boundaries of Mayan power toward Central America. These cities had been long in ruins at the time of the Conquest; their builders were forgotten, and their sites were hardly known; nor do the sparse traditions which have survived in the south the Cakchiquel Annals and the Popul Vuh throw light upon them. Were it not for the ingenuity of scholars, who have deciphered the numeral and dating system of their many monuments, their period would have remained but vague surmise; nor would this have sufficed without the aid of the Tutul-Xiu chronicles to bring the readings within the range of our own chronological system. The problem is by no means a simple one, even when the dates on the monuments have been read; for the southern centres employed a system the "long count," as it is called of which only a single monumental specimen, a lintel at Chichen Itza, has been discovered in the north. Nevertheless, with the aid of this inscription, and with the probable identification of its date in the light of the Books of Chilam Balam, scholars have arrived at something like consensus as to the period of the southern floruit of Mayan culture. This falls within the ninth Maya cycle (160 A. D. to 554 A. D., on Spinden's reckoning), for it is a remarkable fact that practically all the monuments of the south are of this cycle; and as the archaeological evidence indicates an occupancy of nearly two centuries for several of the cities, it is clear that the southern civilization, like the northern of a later day, was marked by the contemporaneous rise of several great centres. Morley 7suggests that the south may even have been held by a league of three cities, as was later the case in the north, Palenque dominating the west, Tikal the centre and north, and Copan the south and east. Two archaic inscriptions on the Tuxtla Statuette and the Leiden Plate, as the relics are called bear dates of the eighth cycle, the earlier falling a century or more before the beginning of our era; and these, no doubt, imply a nascent civilization which was to reach the height of its power in the fifth century, when the cities of the south produced those masterpieces of sculpture which mark the climax of an American aboriginal art, which was to disappear, a century later, leaving scarcely a memory in the land of its origin.

As restored by Morley,

8 the history of Mayan civilization

falls into two periods of imperial development, each subdivided

into several epochs. The older, or parent empire is that of the

south; the later, formed by colonization begun while the old

civilization was still flourishing, is that of the peninsula.

Morley's scheme is as follows:

As restored by Morley,

8 the history of Mayan civilization

falls into two periods of imperial development, each subdivided

into several epochs. The older, or parent empire is that of the

south; the later, formed by colonization begun while the old

civilization was still flourishing, is that of the peninsula.

Morley's scheme is as follows:

Each of the earlier periods is marked by the appearance of new sites and the foundation of new cities as well as by advance in the arts; and as a whole the Old Empire is marked by the high development of its sculpture and the use of the more complete mode of reckoning, while in the cities of the New Empire architecture attains to its highest development.

PLATE XIX: Map of Yucatan, showing sites of ancient cities. After Morley, BBE 57, Plate I.

Such are the more plausible theories of Mayan culture history, although there are others (those of Brasseur de Bourbourg, for example) which would place the age of Mayan greatness earlier by many centuries.

II. VOTAN, ZAMNA, AND KUKULCAN

From their remote beginnings, as with other peoples whose traditions lead back to an age of migrations, the Mayan tribes remembered culture heroes, tutors in the arts as well as founders of empire, priests as well as kings, who may have been historic, 9 but who in origin were probably gods rather than men gods whom time had confused with the persons of their priestly or royal worshippers, and in whose deeds cosmic and historic events were distortedly intermingled. Tales of three such heroes hold a central place in Mayan mythology: Votan, the hero of Tzental legend, whose name is associated with Palenque and the tradition of a great "Votanic Empire" of times long past; Zamna, or Itzamna, a Yucatec hero; and Kukulcan, known to the Quiche as Gucumatz, who is the Mayan equivalent of Quetzalcoatl. All three of these hero-deities are reputed to have come from afar strange in costume and in custom, - to have been the inventors or teachers of writing, and to have founded new cults.

The Tzental legend of Votan, 10 describing him as having appeared from across the sea, declares that when he reached Laguna deTerminos he named the country "the Land of Birds and Game" because of the abundant life of the region; and thence the Votanides ascended the Usumacinta valley, ultimately founding their capital at Palenque, whose older and perhaps original name was Nachan, or "House of Snakes." Shortly afterward, no less astonishing to the Votanides than had been their own apparition to the rude aboriginal, came other boat-loads of long-robed strangers, the first Nahuatlans; but these were peaceably amalgamated into the new empire. Votan ruled many years, and, among other works, composed a narrative of the origin of the Indian nations, of which Ordonez y Aguiar gives a summary. The chief argument of the work, he says, aims to show that Votan was descended from Imos (one of the genii, or guardians, of the days), that he was of the race of Chan, the Serpent, and that he took his origin from Chivim. Being the first man whom God had sent to this region, which we call America, to people and divide the lands, he made known the route which he had followed, and after he had established his seat, he made divers journeys to Valum-Chivim. These were four in number: in the first he related that having departed from Valum-Votan, he set out toward the House of Thirteen Serpents and then went to Valum-Chivim, whence he passed by the city where he beheld the House of God being built. He next visited the ruins of the ancient edifice which men had erected at the command of their common ancestor in order to climb to the sky; and he declared that those with whom he there conversed assured him that that was the place where God had given to each tribe its own particular tongue. He affirmed that on his return from the House of God he went forth a second time to examine all the subterranean regions which he had passed, and the signs to be found there, adding that he was made to traverse a subterranean road which, leading beneath the Earth and terminating at the roots of the Sky, was none other than the hole of a snake; and this he entered because he was "the Son of the Serpent."

Ordonez would like to see in this legend (which he has obviously accommodated to his desire) a record of historical wanderings in and from Old World lands and out of Biblical times. Yet the narrative, even in its garbled form, is clearly a cosmologic myth at the least a tale of the sun's journey, and probably this tale set in the general context of Ages of the World (the four journeys of Votan?) analogous to those of Nahuatlan myth and of the Popul Fuh. When it is added that Votan was known by the epithet "Heart of the People," that his successor was called Canam-Lum ("Serpent of the Earth"), and that both of these were venerated as gods at the time of the Conquest, no word need be added to emphasize the naturalistic character of the myth ; although there may be truth in a legend of Votanides, or Votan-worshippers, as founders of Palenque and possibly as institutors of Mayan civilization.

Zamna (Itzamna, Yzamna, "House of the Dews," or "Lap of the Dews") was the reputed bringer of civilization into the peninsula and the traditional founder of Mayapan, which he was said to have made a centre of feudal rule. Like Votan he was supposed to have been the first to name the localities of the land, to have invented writing, and to have instructed the barbarous aborigines in the arts. "With the populations which came from the East," Cogolludo writes, "was a man, called Zamna, who was as their priest, and who, they say, was the one who gave the names by which they now distinguish, in their language, all the seaports, hills, estuaries, coasts, mountains, and other parts of the country, which assuredly is an admirable thing if he thus made a division of every part of the land, of which scarcely an inch has not its proper appellation in their tongue." After having lived to a great age, Zamna is said to have been buried at Izamal, where his tomb-temple became a centre for pilgrimage. In fact, Izamal is but a modification of a name of Itzamna, since its older form is Itzmatul, which means, says the Abbe Brasseur, "He who asks or obtains the dew or the frost." The ancients of Izamal, Lizana declares, possessed a renowned idol, Ytzmatul, which "had no other name . . . although it was said that he was a powerful king in this region, to whom obedience was given as to the son of the gods. When he was asked how he was named and how he should be addressed, he answered only, Ytzen caan, ytzen muyal, 'I am the dew, the substance, of the sky and clouds.'"

All this is plain euhemerism, for Itzamna was a deity of rain and fertility; Yucatan, it is said, was without moisture when he came to it; he rose from the sea; and his temples and his tomb were by the seaside. His festival, according to Landa, fell in Mac (March), when he was worshipped in company with the gods of abundance. He caused the dead to rise and cured the sick; while in his honour a temple was built with four doors leading to the four extremities of the country, as far as Guatemala, Tabasco, and Chiapas, this shrine being called Kab-ul, or " the Potent Hand," a striking image of the sky- deity reaching down from heaven, of which there are analogues in Egypt and Peru. Both Landa and Lizana state that he was the son of Hunab-Ku ("the Holy One"),

"the one living and true God, who, they said, is the greatest of the gods, and who cannot be figured or represented because he is incorporeal. . . . From him everything proceeds, . . . and he has a son whom they name Hun Ytzamna."

All this indicates a deity of the descending rains and dews, son of Father Heaven, and, through his association with the East, giver of life, light, and knowledge. Students of the codices believe that he is represented by "God D " the aged divinity with the Roman nose and toothless mouth, associated (as is Tlaloc) with the double-headed ser- pent, which is clearly a sky-symbol. Perhaps, as Seler suggests, he is the "Grandfather Above," the Lord of life, analogous to the Mexican Tonacatecutli. 12

As has been indicated, the worship of Kukulcan, 13 to whom tradition ascribed the latest appearance of the three culture heroes, was especially associated with Chichen Itza and Mayapan, and perhaps with Nahua immigrations. His name, like that of the Quiche demiurge Gucumatz, means "Plumed Serpent" and is a precise equivalent of "Quetzalcoatl" the first element referring directly to the long and iridescent plumes of the quetzal. The frequency of bird-serpent symbols in Maya art, regarded as emblematic of this deity, as well as images, both in the codices and on the monuments, of the long-nosed god himself, indicate a deep-seated and fervent worship, so that it may indeed be an open question as to whether Kukulcan is the pattern or the copy of Quetzalcoatl, with the probabilities favoring the Maya source. Certainly it is significant that, as Tozzer tells us, his name still survives among the Yucatec Maya, while to the Lacandones he is a many-headed snake which dwells with the great father, Nohochakyum: "this snake is killed and eaten only at the time of great national peril, as during an eclipse of the moon and especially that of the sun." The importance of Kukulcan in the peninsula is indicated by Landa's description of his festival, which occurred on the sixteenth day of Xul (October 24). Upon Kukulcan's departure, says Landa (who clearly regarded the god as an historical personage), there were some Indians who believed that he had ascended into heaven, and regarding him as a god, they built temples in his honour. After the destruction of Mayapan, however, his feasts were kept only in the province of Mani, "but the other districts, turn by turn, in recognition of what was due to Kukulcan, presented each year at Mani sometimes four, sometimes five, magnificent feather banners with which they celebrated the fete."

This festival was observed in the following manner: After fasts and abstinences, the lords and priests of Mani assembled before the multitude; and on the evening of the festal day, together with a great number of mummers, they issued from the palace of the prince, proceeding slowly to the temple of Kukulcan, which had been properly adorned. When they had reached it and had prayed, they erected their banners, setting forth their idols on a carpet of leafage; and having lighted a new fire, they burned incense in many places, making oblations of meat cooked without seasoning and of drink made from beans and the seeds of gourds. The lords and all who had observed the fast remained there five days and five nights, praying, burning copal, and performing sacred dances, during which period the mummers went from the house of one noble to that of another, performing their acts and receiving the gifts offered them. At the end of five days they carried their donations to the temple, where they shared all with the lords, the singers, the priests, and the dancers; and after this the banners and idols (doubtless house-hold gods) were taken again to the palace of the prince, whence each returned to his own house. "They say and hold for certain that Kukulcan descended from the sky the last day of the feast and personally received the sacrifices, the penitences, and the offerings made in his honour."

III. YUCATEC DEITIES

For the names of the Maya gods we are mainly indebted to sparse notices in the works of Landa and Lizana, who, in obliterating native writings, destroyed far more than they preserved. Landa 14 gives a general picture of the aboriginal religion, indicating a ritual not less elaborate than the Mexican, though with far less human bloodshed. "They had," he says, "a great number of idols and of sumptuous temples. Besides the ordinary shrines, princes, priests, and chief men had oratories with household idols, where they made special prayers and offerings. They had as much devotion for Cozumel and the wells of the Chichen Itza as we for pilgrimages to Rome and Jerusalem; and they went to visit them and make offerings as we go to holy places. . . . They had such a number of idols that their gods did not suffice them; for there was not an animal nor a reptile of which they did not make images, and they formed them also in the likeness of their gods and goddesses. They had some idols of stone, but in small number, and others, of lesser size, of wood, though not so many as of earthenware. The idols in wood were esteemed to such a degree as to be counted for inheritances, and in them they had the greatest confidence. They were not at all ignorant that their idols were only the work of their own hands, dead things and without divinity, but they venerated them for the sake of what they represented and because of the rites with which they had consecrated them."

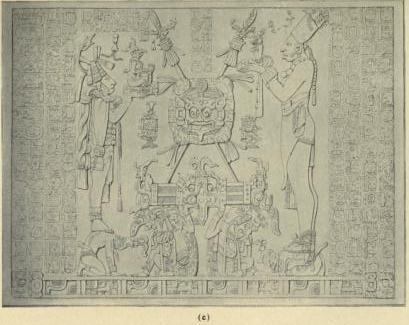

PLATE XX

(A): Tablet of the Foliated Cross, Palenque. This cross, like that shown in Plate XX (B), rests upon a monstrous head, doubtless representing the Underworld, and is surmounted by the quetzal, the symbol of rain and vegetation. It is possible that the greater of the two human figures represents a deity, the lesser a priest, or that both are divinities as in the analogous figures of the codices (cf. Plate IX, upper figure). After drawing in Maudsley [c], Vol. IV.

(B): Tablet of the Cross, Palenque. The cross was encountered as an object of worship on the Island of Cozumel by the first-coming Spaniards. Cruciform figures of several types are of frequent occurrence as cosmic symbols in Mexican and Mayan art. With this plate and with Plate XX (A) should be compared Plates VI and I0X. After drawing in Maudsley [c], Vol. IV.

(C): Tablet of the Sun, Palenque. The two cary- atid-like figures beneath the solar symbol doubtless represent the upbearers of the heavens (cf. Plate IX, lower figure). After drawing in Maudsley [c], Vol. IV.

Among the deities mentioned by Landa are the Chacs, or "gods of abundance," whose feasts were held in the spring of the year in connexion with the four Bacab, or deities of the Quarters; and again in association with Itzamna at the great March festival designed to obtain water for the crops, when the hearts of every kind of wild animal and reptile were offered in sacrifice. The Chacs were evidently rain-gods, like the Mexican Tlaloque, with a ruler, Chac, corresponding to Tlaloc. The name was likewise applied to four old men annually chosen to assist the priests in the festivals, and from Landa's descriptions of the parts played by them it is clear that they represented the genii of the Quarters.

Other divinities who are named include Ekchuah (also mentioned by Cogolludo and Las Casas), to whom travellers prayed and burned copal: "At night, wherever they rested, they erected three small stones, depositing upon each of these some grains of their incense, while before them they placed three other flat stones on which they put more incense, entreating the god which they name Ekchuah that he would deign to bring them safely home." There were, again, medicine-gods, Cit-Bolon-Tum and Ahau-Chamahez, names which Brasseur de Bourbourg 15 interprets as meaning respectively "Boar-with-the-Nine-Tusks" and " Lord-of-the-Magic-Tooth." There were gods of the chase; gods of fisher folk; gods of maize, as Yum Kaax ("Lord of Harvests"), of cocoa; and no doubt of all other food plants. Of the annual feasts, the most significant appear to have been the New Year's consecration of the idols in the month Pop (July) ; the great medicine festival, with devotion to hunters' and fishermen's gods, in Zip (September) ; the festival of Kukulcan in Xul (October); the fabrication of new idols in Mol (December); the Ocna, or renovation of the temple in honour of the gods of the fields, in Yax (January); the interesting expiation for bloodshed "for they regarded as abominable all shedding of blood apart from sacrifice" in Zac (February); the rain-prayer to Itzamna and the Chacs, in March (mentioned above); and the Pax (May) festival in which the Nacon, or war-chief, was honoured, and at which the Holkan-Okot, or "Dance of the Warriors," was probably the notable feature. The war-god is represented in the codices with a black line upon his face, supposed to represent war-paint, and is often shown as presiding over the body of a sacrificial victim; while with him is associated not only the death-god, Ahpuch, but another grim deity, the "Black Captain," Ek Ahau.

Celestial divinities were probably numerous in the Maya pantheon, as was almost inevitable in view of the extraordinary development of astronomical observation. Xaman Ek was the North Star, while Venus was Noh Ek, the Great Star. The Sun, according to Lizana, 16 was worshipped at Izamal as Kinich-Kakmo, the "Fiery-Visaged Sun"; and the macaw was his symbol, for, they said, "the Sun descends at midday to consume the sacrifice as the macaw descends in plumage of many colours." In view of all the fire thus came at noon upon the altars, after which the priest prophesied what should come to pass, especially by way of pestilence, famine, and death. "The Yucatec have an excessive fear of death," says Landa, "as may be seen in all their rites with which they honour their gods, which have no other end than to obtain health and life and their daily bread"; and he continues with a description of the abode of blessed souls, a land of food, drink, and sweet savours, where "there is a tree which they call Yaxche, of an admirable freshness under the shady branches of which they will enjoy eternal pleasure. . . . The pains of a wicked-life consist in a descent to a place still lower which they call Mitnal, there to be tormented by demons and to suffer the tortures of hunger, cold, famine, and sorrow." The lord of this hell is Hanhau; and the future life, good or bad, is eternal, for the life of souls has no end. "They hold it as certain that the souls of those who hang themselves go to paradise, there to be received by Ixtab, goddess of the hanged"; and many ended their lives in this manner for but light reason such as a disappointment or an illness.

The image of Ixtab, with body limp and head in a loop, as if hanged, is one of those recognized in the codices; for in default of mythic tales, few of which are preserved concerning the Yucatec gods, these codex drawings and the monumental images furnish our main clues to the Maya pantheon. Follow- ing the suggestion of Schellhas, 17 it is customary to designate the codical deities (nameless, or uncertainly named) by letters. Thus, God A is represented with visible vertebrae and skull head, and is therefore identified as the death-god, named Hanhau in Landa's account, Ahpuch by Hernandez, and Yum Cimil ("Lord of Death") by the Yucatec of today. Death is occasionally shown as an owl-headed deity, and is also associated with the moan-bird (a kind of screech-owl), with the god of war, and with a being that is dubiously identified as a divinity of frost and of sin. God B, whose image occurs most frequently of all in the codices, and who is represented with protruding teeth, a pendulous nose, and lolling tongue, is closely connected with the serpent and with symbols of the meteorological elements and of the cardinal points; and is regarded as representing Kukulcan. God C, the "god with the ornamented face," is a sky-deity, tentatively identified with the North Star, or perhaps with the constellation of the Little Bear. God D, the old divinity with the Roman nose and the toothless jaws, is regarded by Schellhas as a god of the moon or of the night, although in him other scholars see Itzamna, regarded as a sun-deity. God E is the maize-god, probably Yum Kaax, or "Lord of Harvests"; God F is the deity of war; and with him is sometimes associated God M, the "black god with the red lips," perhaps Ekchuah, the divinity of merchants and travellers, for war and commerce are connected in the New World as in the Old.

These seven deities are those of most frequent occurrence in the codices, though the full list, which surely gives a general picture of the Maya pantheon, includes also God G, the sun-god God H, the Chicchan-god (or serpent-deity) ; God I, a water-goddess; God K, the "god with the ornamented nose"; God L, the "old black god," perhaps related to M; God N, the "god of the end of the year"; God O, a goddess with the face of an old woman; and God P, a frog-god. Others are animal deities, the dog, jaguar, vulture, tortoise, and, in differing shapes of representation, the panther, deer, peccary, bat, and many forms of birds and animals.

Not a few of these ancient deities hold among the Maya of today something of their ancient dignity: they are slightly degraded, not utterly overthrown by the intervention of Catholic Christianity. At least this is the picture given by Tozzer as result of his researches among the Yucatac villagers. According to them, he says, 18 there are seven heavens above the earth, each pierced by a hole at its center. A giant ceiba, growing in the exact center of the earth, rears its branches through the holes of the heavens until it reaches the seventh, where lives El Gran Dios of the Spaniards; and it is by means of this tree that the spirits of the dead ascend from heaven to heaven. Below this topmost Christianized heaven, dwell the spirits, under the rule of El Gran Dios, which are none other than the ancient Maya gods. In the sixth heaven are the bearded old men, the Nukuchyumchakob, or Yumchakob, white-haired and very fond of smoking, who are the lords of rain and the protectors of human beings apparently the Chacs of the earlier chroniclers, though the description of them would seem to imply that Kukulcan is of their number; perhaps originally he was their lord; now they receive their orders from El Gran Dios.

In the fifth heaven above dwell the protecting spirits of the fields and the forests;. in the fourth the protectors of animals; in the third the spirits ill-disposed toward men; in the second the lords of the four winds; while in the first above the earth reside the Yumbalamob, for the special protection of Christians. These latter are invisible during the day, but at night they sit beside the crosses reared at the entrances of the pueblos, one for each of the cardinal points, protecting the villagers from the dangers of the forest. With obsidian knives they cut through the wind, and make sounds by which they signal to their comrades stationed at other entrances to the town. Truly, this description answers astonishingly to the Aztec lord of the crossroads, Tezcatlipoca.

Below the earth is Kisin, the earthquake, the evil one, who resents the chill rains sent down by the Yumchakob, and raises a wind to clear the sky. The spirits of suicides dwell here also, and all souls excepting those of war-slain men and women dead of child-birth (which go directly to heaven) are doomed for a time to this underworld realm.

Other diminished deities are Ahkinshok, the owner of the days; the guardians of the bees; the spirit of newfire; Ahkushtal, of birth; Ahmakiq, who locks up the crop-destroying winds; patrons of medicine; and a crowd of workers of ill to men, among them the Shtabai, serpentiform demons who issue from their cavernous abodes and in female form snare men to ruin. Paqok, on the other hand, wanders abroad at night and attacks women. The Yoyolche are also night-walkers; their step is half a league, and they shake the house as they pass.

Tozzer makes the interesting observation that in many cases, where among the Maya is found a class of spirits, the purely heathen Lacandones recognize a single god. Thus, to the Nukuchyumchakob of the Maya corresponds the Lacandone Nohochakyum, who is the Great Father and chief god of their religion, having as his servants the spirits of the east, the constellations, and the thunder. At the end of the world he will wear around his body the serpent Hapikern, who will draw people to him by his breath and slay them. Nohochakyum is one of four brothers, apparently lords of the four quarters. As is usual in such groups, he of the east is pre-eminent. Usukun, one of the brothers, is a cave-dweller, having the earthquake for his servant; he is regarded with dread, and his image is set apart from the other gods. There are a number of other gods and goddesses of the Lacandones, several of which are clearly identifiable as the same as the Maya deities described by Landa and other early writers. As a whole, the pantheon is a humane one; it lacks that quality of terror which makes hideous the congregation of the Aztec deities. Most of the gods, Maya and Lacandone, are kindly-disposed toward men, and doubtless it was this kindliness reflected back which kept the Maya altars relatively free of human blood.

IV. RITES AND SYMBOLS

No region in America appears to have furnished so many or such striking analogies to Christian ritual and symbolism as did the Mayan. It was here, on the island of Cozumel, that the cross was an object of veneration even at the first coming of the Spaniard; and when the rites of the natives were studied by the missionaries, they were found to include many that seemed to be Christian in inspiration. Bishop Landa 19 describes at length the Yucatec baptism, which was designated by a name equivalent, he says, to renascor " for in the Yucatec tongue zihil means to be reborn" and which was celebrated in a complex festival, godfather and all. The name of the rite was Em-Ku, or "Descent of God"; and, he adds, "They believe that they receive therefrom a disposition inclined to good conduct and that it guarantees them from all temptations of the devil with respect to temporal things, while by means of this rite and a good life they hope to secure salvation." Sacraments of various sorts, confession of sins, penitence, penance, and pilgrimages to holy shrines were other ritual similarities with Catholic Christianity which could not fail to be impressive and which actually furthered the change of religion with a minimum of friction.

Along with these analogies of ritual there were likenesses of belief: traditions of a deluge, a confusion of tongues, and a dispersion of peoples, as well as reminiscences of legendary teachers of the arts of life and of the truths of religion in which it was not difficult for the eye of faith to discern the missionary labours of Saint Thomas. Las Casas, 20 quoting a certain cleric, Padre Francisco Hernandez, tells of a Yucatec trinity: one of their old men, when asked as to their ancient religion, said that "they recognized and believed in God who dwells in heaven, and that this God was Father and Son and Holy Spirit, and that the Father was called Icona, who had created men and all things, that the Son was named Bacab, and that he was born of a virgin called Chibirias, who is in heaven with God; the Holy Spirit they termed Echuac." The son, Bacab, it is added, being scourged and crowned with thorns by one Eopuco, was tied upon a cross with extended arms, where he died; but after three days he arose and ascended into heaven to be with his father. The name Echuac signifies "merchant"; "and good merchandise the Holy Spirit bore to this world, for He filled the earth with gifts and graces so divine and so abundant."

The honesty of this account is no less evident than its distortion, which may have been due as much to the confused reminiscences of the old Indian as to the imaginative expectancy of the Spanish recorder. Bacab and Ekchuah are mentioned by Landa and others, and Las Casas also states that the mother of Chibirias was named Hischen (que nosotros decimos haber sido San? Ana), who must surely be the goddess Ixchel, goddess of fecundity, invoked at child-birth. The association of the Bacabs (for there are four of them) with the cross and with heaven is also intelligible, since the Bacabs are genii of the Quarters, where they upheld the skies and guarded the waters, which were symbolized in rites by water-jars with animal or human heads. They are, no doubt, in the Maya region as in Mexico, represented by caryatid and cruciform figures, of which, we may suppose, the celebrated Tablet of the Cross and Tablet of the Foliate Cross at Palenque are examples.

The character of the Bacab is best indicated by Landa's 21 description of the New Year festival celebrated for them; and he calls them "four brothers whom God, when creating the world, had placed at its four corners in order to uphold the heaven . . . though some say that these Bacabs were among those who were saved when the earth was destroyed in the Deluge." In all the Yucatec cities there were, Landa states, four entrances toward the four points, each marked by two huge stones opposite one another; and each of the four successive years designated by a different New Year's sign was introduced by rites performed at the stones marking the en- trance appropriate to the year. Thus Kan years were devoted to the south. The omen of this year was called Hobnil, and the festival began with the fabrication of a statue of Kan-u-Uayeyab which was placed with the stones of the south, while a second idol, called Bolon-Zacab, was erected at the principal entrance of the chief's house. When the populace had assembled they proceeded, along a path well-swept and adorned with greenery, to the gate of the south, where priests and nobles, burning incense mingled with maize, sacrificed a fowl. This done, they placed the statue upon a litter of yellow wood, "and upon its shoulders an angel horribly fashioned and painted as a sign of an abundance of water and of a good year to come." Dancing, they conveyed the litter to the presence of the statue of Bolon-Zacab at the chiefs house, where further offerings were made and a banquet was shared by such strangers as might be within the gates. "Others drawing blood and scarifying their ears, anointed a stone which was there, an idol named Kanal-Acantun ; and they moulded also a heart of bread-dough and another of gourd-seeds which they presented to the idol Kan-u-Uayeyab.

PLATE XXI: Stone Lintel from Menche, Chiapas, representing a Maya priest asperging a penitent who is drawing a barbed cord through his tongue. After photograph in the Peabody Museum.

Thus they guarded this statue and the other during the unlucky days, smoking them with incense and with incense mingled with ground maize for they believed that if they neglected these rites, they would be subject to the ills pertaining to this year. When the unlucky days were past, they carried the image of Bolon-Zacab to the temple, and the idol of the other to the eastern gate of the town, that there they might begin the New Year; and leaving it in this place, they returned home, each occupying himself with the duties of the New Year." This was regarded as a year of good augury; and similar rites were performed in connexion with each of the other year-signs. Under Muluc the omen was called Canzienal and was also regarded as good. It was the year of the east, and the gate was marked by an idol named Chac-u-Uayeyab, while the deity presiding at the chief's house was termed Kinich-Ahau, the meaning of which must be " Lord of the Solar Eye" if Brasseur's interpretation be correct. War- dances were a feature of the celebration, doubtless to Sol In- victus; and offerings made in the form of yolks of eggs further suggest solar symbolism ; while it was believed that eye-disease or injury would be the lot of anyone who neglected the rites. Ix years were devoted to the north, with an omen called Zac-Ciui and regarded as evil. The god of the quarter was named Zac-u-Uayeyab, and he of the centre Yzamna, to whom were offered turkeys' heads, quails' feet, etc. Cotton was the sole crop in which abundance was to be expected, while ills of all sorts threatened. Darker still were the prognostics of Hozanek, the omen of Cauac years, sacred to the west. An image of Ek-u-Mayeyab was carried to the portals of the west, while Uac-Mitun-Ahau presided in the central place; and on a green and black litter the god of the gate was carried to the centre, having on his shoulders a calabash and a dead man, with an ash-coloured bird of prey above. "This they conveyed in a manner showing devotion mingled with distress, performing dances which they called Xibalba-Okot, which signifies 'dance of the demon.'" Pests of ants and devouring birds were among the plagues expected; and among the rites by which they sought to exorcise these evils was a night of bonfires, through the hot coals of which they raced with bare feet, hoping thus to expiate the threatened ills, all ending in an intoxication "demanded both by custom and by the heat of the fire."

V. THE MAYA CYCLES

22 It is probable that the Mexican calendar is remotely of Mayan origin, especially as the fundamental features of the calendric system are the same in the two regions; viz., first, the combination of the Tonalamatl of two hundred and sixty days with the year of three hundred and sixty-five days in a "round" or "bundle," of fifty-two such years; and second, the co-ordination of cyclic returns of calendric symbols with the synodic periods of the planets, serving, along with purely numerical counts, to distinguish and characterize the major cycles. It is in this second feature that the Maya calendar is vastly superior to the Mexican; forming, indeed, by far the most impressive achievement of aboriginal America in the way of scientific conception.

The Mayan name for the period known to the Aztec as Xiuhmolpilli, or "Bundle of the Years," is unknown; it is customarily designated as the Calendar Round. In construction it is essentially the same as the Mexican : the day, kin (literally, "sun"), is combined in the twenty-day period, or uinal (prob- ably related to uinic, "man," referring to the foundation of the vigesimal system in the full count of fingers and toes); and thirteen of these periods are united in the Tonalamatl (the Maya name is unknown), which Goodman designates the "Burner Period," believing it to be ceremonially related to incense burning. As the combination of thirteen numerals with the twenty day-signs causes the completion of their possible combinations in this period, the series, as with the Mexicans, begins anew at the end of the Tonalamatl; and is so continued, repeating indefinitely. The names of the Maya days, corresponding to the twenty signs, are: Imix, Ik, Akbal, Kan, Chicchan, Cimi, Manik, Lamat, Muluc, Oc, Chuen, Eb, Ben, Ix, Men, Cib, Caban, Eznab, Cauac, and Ahau. Each of these day-signs (and probably each of the thirteen numbers accompanying them) had its divinatory significance; and it is quite certain, from Landa's references alone, that divination formed a prominent use of calendric codices.

The year, or haab, of the Maya, again like the Mexican, consisted of eighteen uinals Pop, Uo, Zip, Zotz, Tzec, Xul, Yaxkin, Mol, Chen, Yax, Zac, Ceh, Mac, Kankin, Muan, Pax, Kayab, and Cumhu, plus five "nameless days," or Uayeb. This year of three hundred and sixty-five days is, of course, a quarter of a day less than the true year, and such astronomers as the Maya must have been could not have failed to discover this fact. Bishop Landa states explicitly that they were quite aware of it; but they did not, in all probability, resort to any intercalation to correct the defect, for the whole genius of the Mayan calendar consists in their unswerving maintenance of the count of days. On the other hand, it is probable that the priests who made the solar observations adjusted the seasonal feasts to the changing dates as in the precisely similar custom of ancient Egypt, where each ascending Pharaoh swore to preserve the civil year of three hundred and sixty-five days with- out intercalation : the immense power and prestige given to the priesthood by this custom is a sufficient reason for its perpetuity. The fact that 20 (uinal) and 365 (haab} factor with 5 gives, again, the division of the uinal days into groups of five, each headed by one of the four Ik, Manik, Eb. and Caban which alone could be New Year's days.

The names of the "month," or divisions of the year, like the names of the uinal days, were symbolized by hieroglyphs, and the days of the month were numbered o to 19, since in their reckoning of time the Maya always counted that which had elapsed. Thus every day had a double designation : its position in the Tonalamatl, determined by day-sign and day-number (i . . . 13), and its position in the haab, determined by "month "-sign (uinal or Uayeb) and day-number (o . . . 19), as, for example, the date-name of the Maya Era, "4 Ahau 8 Cumhu." The possible combinations of these elements is ex- hausted only in a cycle of 18,980 days, equal to 73 Tonala- matls and to 52 haabs. This is the Calendar Round, or cycle of date-names, which, like the other elements in the Maya calendar, is endlessly repeated. It is probable that the Aztec had no such precision in their dating system even within the Year-Bundle, evidence for the employment of month-signs in computation of the day-series being uncertain.

In yet another important respect the Maya were far in advance

of the Mexicans, for the latter had no adequate means of

distinguishing dates of the same name belonging to separate

Year-Bundles, in consequence of which their historic records are

full of confusion; whereas the Maya developed an elaborate method

still, curiously enough, a day-count parallel with the Calendar

Round series, by which they were able to record historic dates

for immense periods. The system was essentially mathematical and

was based on their vigesimal notation, its elements being as

follows:

In this series, it will be observed, the third day-group does not rise from the second by vigesimal multiplication; and it is assumed that it has been, as it were, psychologically deflected from the regular ascending series by the attraction of the 18 uinals of the natural year in order to bring the tun into some kind of conformity with the haab. Beyond the katun, the native names for the cycles are unknown, though their symbols have been determined.

The series of units of time thus composed is that employed by the Maya of Yucatan, as recovered from the early Spanish records and the codices. In this region the katun was the historical unit of prime significance, for both Landa and Cogolludo note the fact that at the end of every katun a graven stone was erected or laid in the walls of an edifice to record the event. Study of the sculptured stelae of the capitals and cities of the Old Empire of the south has convinced archaeologists that these stelae are similarly, in great part, monuments erected not primarily to honor men or commemorate events but to mark the passage of time. The units, however, as recorded from readings of the dates, are not primarily katuns (of 7200 days), but halves and quarters of the katun. Morley, 23 to whom belongs credit of the demonstration of the system, gives to these lesser periods the names hotun ("five tuns," or 1800 days) and lahuntun ("ten tuns" or 3600 days). The amazing monu- mental wealth, therefore, of the old Maya cities turns out to be chiefly due to the importance which the Maya peoples attached to the idea of time itself and to the recording of its passage.

Such an idea could only have reference to religious or

mythico-religious beliefs, of the nature of which something is to

be inferred from the monumental and codical indications of the

cycles and the Great Cycle which entered into Maya computations.

The cycle is clearly a conception induced by the necessities of

vigesimal notation, with, no doubt, mythic associations suggested

by its pictographic notation; it is a period of twenty katuns,

just as the katun is twenty tuns. But the duration of the Great

Cycle is matter of dispute. Bowditch and Goodman, basing their

judgment on the fact that the cycles in the inscriptions are

numbered I ... 13, and again upon the fact that the two known

starting-points, or eras, of Maya monumental chronology are just

thirteen cycles apart, regard the Great Cycle as composed of

thirteen cycles; Morley, chiefly from evidence in the codices,

believes that it was composed of twenty cycles. It is possible,

of course, that the conception of the Great Cycle changed from

the time of the Old Empire to that of the New, perhaps influenced

by the change in the period of erecting monumental records; but

in any case the immense numbers of days embraced in the Maya

reckonings excite our wonder. Such calculations could have been

made possible only by the use of a highly developed arithmetical

system, and this the Maya possessed; for they had developed a

positional notation, employing a sign for zero (![]() ), a system of

dots ( . = I; . . =2; etc.) and bars ( 5; = = 10; etc.) for the

integers I ... 19 (

), a system of

dots ( . = I; . . =2; etc.) and bars ( 5; = = 10; etc.) for the

integers I ... 19 (![]() = 19), while the concep- tion of positive and

negative was achieved through the use of these elements recorded

vertically units above zero, twenties above the units, tuns in

the third position upward, and so on. The tun ( = 360) is an

obvious calendric number, and this makes clear that the Maya

certainly developed the higher possibilities of their mode of

computation in connexion with the needs of their reckoning of

time. The perfection of their achievement is indicated by the

fact that through its use they were enabled to distinguish any

date within the range of a Great Cycle from any other, thus

creating a numbered time-scheme which in our own system would be

measured by millenia.

= 19), while the concep- tion of positive and

negative was achieved through the use of these elements recorded

vertically units above zero, twenties above the units, tuns in

the third position upward, and so on. The tun ( = 360) is an

obvious calendric number, and this makes clear that the Maya

certainly developed the higher possibilities of their mode of

computation in connexion with the needs of their reckoning of

time. The perfection of their achievement is indicated by the

fact that through its use they were enabled to distinguish any

date within the range of a Great Cycle from any other, thus

creating a numbered time-scheme which in our own system would be

measured by millenia.

To complete its historical value only one element need be added, the selection of an era from which to reckon dates. Two such eras are known, one bearing the name 4 Ahau 8 Cumhu, and the other (found in only two inscriptions) that of 4 Ahau 8 Zotz, this falling thirteen cycles earlier than the other. The former, from which nearly all the monumental in- scriptions are reckoned, is some three thousand years anterior to the period of the inscriptions themselves and probably, therefore, refers to an event in the third millennium B. c., assuming that the monuments belong to the first thousand years of our era. It is altogether unlikely that a date so remote can represent any but a mythical event, such, we may suppose, as the end of a preceding "Sun," or Age of the World, and the beginning of that in which we live; for the Maya, like the Nahua, possessed the myth of ages of this type. Cogolludo mentions two of these ages as terminated by annihilation of the human race through epidemic, and a third as ended by storm and flood; while Landa's account of the calamities following the destruction of Mayapan seems clearly to be intermingled with a myth of world catastrophes. The Popul Fuh shows that the character of the Quiche legend was not essentially unlike that of the Aztec, who may, indeed, have received from the Maya their cosmogony along with their calendric system, of which it is doubtless in some degree a product.

Astronomical data must have entered into the calculation of these great epochs. Forstemann and other students have discovered in the codices, particularly in the Dresden Codex, evidences of the reckoning of the period not only of Venus (five hundred and eighty-four days), but also of lunar revolutions, of the period of Mars (seven hundred and eighty days), and possibly of the cycles Jupiter, Saturn, and Mercury as well. Such periods, for astrological and divinatory purposes, were recorded in the books of the priests; and, as elsewhere in the world, the synodic revolutions of the planets, and the recurrences of their stations with respect to the day-signs, gave the material for the formation of huge cycles of time which their mathematical system enabled them to compute. Thus it is that Forstemann finds near the end of the Dresden Codex vast numbers designated as "Serpent Numbers" because of the occurrence of the serpent-symbol in connexion with them which correspond to such cyclic recombinations of signs and events.

"In the so-called 'serpent numbers,'" writes Morley, 24 "a grand total of nearly twelve and a half million days (about thirty-four thousand years) is recorded again and again. In these well-nigh inconceivable periods all the smaller units may be regarded as coming at last to a more or less exact close. What matter a few score years one way or the other in this virtual eternity? Finally, on the last page of the manuscript, is depicted the Destruction of the World, for which the highest numbers have paved the way. Here we see the rain serpent, stretching across the sky, belching forth torrents of water. Great streams of water gush from the sun and moon. The old goddess, she of the tiger claws and forbidding aspect, the malevolent patronness of floods and cloudbursts, overturns the bowl of the heavenly waters. The crossbones, dread emblem of death, decorate her skirt, and a writhing snake crowns her head. Below with downward-pointed spears, symbolic of the universal destruction, the black god stalks abroad, a screeching owl raging on his fearsome head. Here, indeed, is portrayed with graphic touch the final all-engulfing cataclysm." In their sculpture the Maya far surpassed the artistic expression of all other Americans, attaining not only decorative power, but such idealization of the human countenance as is possible only among people whose aesthetic sensibilities have an intellectual background and guidance. No more convincing evidence of this mental power could be forthcoming than is shown in their mathematical and astronomical learning, at once a testimony to the antiquity of their culture and to the force of their native genius.

VI. THE CREATION

PLATE XXII: Final page from the Codex Desdensis showing "Serpent Numbers" and typifying the cataclysms destroying the world. See pages 151-52 for de- scription, and compare Plates XII, XIII, XIV.

Just as the notion of great astronomical cycles shadowed forth eschatological cataclysms, so it reverted to cyclic aeons of the past in which the world came to its present form. There is no such wealth of creation myth preserved from the ancient Maya as from the Nahua, but enough is recorded to make it clear that the ideas of the two peoples were essentially one: indeed, they clearly belong to a group of cosmogonical conceptions extending as far to the north as the Pueblos of the United States, and not without influence beyond, into the prairie country. Possibly the whole complex conception had its first telling with the Maya; it is with them, at least, that the numerical and calendric ideas with which it is logically associated received the greatest development and give the most natural raison d'etre to the mythic lore.

Something of the nature of the Maya conception is intimated by Cogolludo and Landa, as noted in a preceding paragraph. More is given in Tozzer's account of Maya religion as it is today.25 According to information obtained from Mayas of Valladolid, the world is now in the fourth period of its existence. In the first, there lived the Saiyamkoob, "the Adjusters," the primitive race of Yucatan, who were dwarfs and built the cities now in ruins. Their work was done in darkness, when as yet there was no sun. When the sun appeared they were turned into stone, and their images are to be found today in the ruins. In this period there was a living rope extending from earth to sky, by which food was brought down to the builders. Blood was in this rope; but the rope was cut, the blood flowed out, and earth and sky were parted. Water-over-the-earth ended this period. It was followed by the age of the Tsolob, "the Offenders"; and these, too, were destroyed by a flood. The third age was that in which the Maya reigned, but their day likewise passed amid waters of destruction, to give place to the present age peopled by a mixture of all the races that have previously dwelt in Yucatan.

It is easy to align these notions with what we know of Mexican myth, though it is evident that history rather than genesis is its present significance. But purely cosmogonic is the fragment from the Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel published by Martinez Hernandez 26 with its suggestion of the Thirteen Lords of the Day captured by the Nine of the Night as the first great act:

"During the II dhau, Ahmucen-cab come [came] to cover the faces of Oxlahun-ti-ku (thirteen gods); his names were unknown except those of his sister and of his children: and they said that the faces also were equally not visible; then, when the world was made, they knew not that they would be entirely cast away; and Oxlahun-ti-ku was captured by Bolon-ti-ku (nine gods); then he brought down fire; then he brought down salt; then he brought down the stones and trees and came to play with the stones and trees; and Oxlahun-ti-ku was caught and they broke his head and buffeted him, and also carried him on their backs; and they despoiled him of his dragon and his tizne [black paint or soot]; and they took fresh shoots of yaxum and white beans, tuberous roots cut up small, and the heart of small calabash seeds and of large calabash seeds cut up small, and of black beans cut up small. This first Bolon-tsac-cab (nine orders of the world) made a thick covering of seeds and went away to the thirteenth heaven, and the surface of the earth remained formed, and the peaks of the rocks of the world.

"And the heart of Oxlahun-ti-ku went away, the hearts of the tuberous roots refusing to go. And there came women without-fathers, with those who have hard work, the without husbands, who, although living have no heart; and wrapped in dog's grass, they were buried in the sea.

"All at once came the water after the dragon was carried away. The heaven was broken up; it fell upon the earth; and they say that Cantul-ti-ku (four gods), the four Bacab, were those who destroyed it. Then, when the universal destruction was past, they placed as dweller Kan-xib-yui, to order it anew. And the tree, the white ymix, was placed standing in the north; and he placed the supporting poles of the heaven; and it was said that this tree was the symbol of the universal destruction." Four other trees, each of a different colour, each symbol of a destruction of the world, were planted at the remaining quarters and the centre; and the form of the world was then complete. "'The whole world,' said Ah-uuc-chek-nale (he who seven times makes fruitful), 'proceeded from the seven bosoms of the earth.' And he descended to make fruitful Itzam-kab-ain (the female whale with alligator feet), when he came down from the central angle of the heavenly region. The four lights, the four regions of the stars, revolved. As yet there was no light; absolutely there was no sun; absolutely there was no night; absolutely there was no moon. They awoke; and from then began the world. At that instant the world began. Thirteen numeral orders, with seven, is the period since the beginning of the world."

NOTES

1. The physiography and ethnography of the Maya region are summarized in Spinden [a]; Beuchat, II, ii; and in Joyce [b], ch. viii. Wissler, The American Indian in this, as in other fields, most effectively presents the relations ethnical, cultural, historical to the other American groups. Recent special studies of importance are Tozzer [a]; Starr, In Indian Mexico, etc.; Sapper [b]; and the more distinctively archaeological studies of Holmes, Morley, Spinden, and others.

2. It is unfortunate that the region of Maya culture was the subject of no such full reports, dating from the immediate post-Conquest period, as we possess from Mexico. The more important of the Spanish writers who deal with the Yucatec centres are Aguilar, Cogolludo, Las Casas, Landa, Lizana, Nunez de la Vega, Ordonez y Aguiar, Pio Perez, Pedro Ponce, and Villagutierre, with Landa easily first in significance. The histories of Eligio Ancona and of Carrillo y Ancona are the leading Spanish works of later date. Native writings are represented by three hieroglyphic pre-Cortezian codices, namely, Codex Dresdensis, Codex Tro-Cortesianus, and Codex Peresianus, as well as by the important Books of Chilam Balam and the Chronicle of Nakuk Pech from the early Spanish period (for description of thirteen manuscripts and bibliography of published works relating to their interpretation, see Tozzer, "The Chilam Balam Books," in CA xix [Washington, 1917]). Yet what Mayan civilization lacks in the way of literary monuments is more than compensated by the remains of its art and architecture, to which an immense amount of shrewd study has been devoted. The more conspicuous names of those who have advanced this study are mentioned in connexion with the literature of the Maya calendar, Note 22, infra. The region has been explored archaeologically with great care, the magnificent re- ports of Maudsley (in Biologia Centrali-Americana) and of the Peabody Museum expeditions (Memoirs}, prepared by Gordon, Maler, Thompson, and others, being the collections of eminence. Brasseur de Bourbourg can scarcely be mentioned too often in connexion with this field. His fault is that of Euhemerus, but he is neither the first nor the last of the tribe of this sage; while for his virtues, he shows more constructive imagination than any other Americanist: probably the picture which he presents would be less criticized were it less vivid.

3. Landa, chh. v-xi (vi, ix, being here quoted).

4. The sources for the history of the Maya are primarily the native chronicles (the Books of Chilam Balam), the Relaciones de Yucatan, and the histories of Cogolludo, Landa, Lizana, and Villagutierre. The deciphering of the monumental dates of the southern centres has furnished an additional group of facts, the correlation of which to the history of the north has become a special problem, with its own literature. The most important attempts to synchronize Maya dates with the years of our era are by Pio Perez (reproduced both by Stephens [b] and by Brasseur de Bourbourg [b]); Seler [a], i, "Bedeutung des Maya-Kalenders fur die historische Chronologic"; Good- man [a], [b]; Bowditch [a]; Spinden [a], pp. 130-35; [b] (with chart); Joyce [b], Appendix iii (with chart); and Morley [a], [b], [c] and [d]. Bowditch, Spinden, Joyce, and Morley are not radically divergent and may be regarded as representing the conservative view here accepted as obviously the plausible one. Carrillo y Ancona, ch. ii, analyzes some of the earlier opinions; while the first part of Ancona's Historia de Yucatan is devoted to ancient Yucatec history and is doubtless the best general work on the subject.

5. Brinton [f], p. 100 ("Introduction" to the Book of Chilan Balam of Mani).

6. Spinden [b]; Joyce [b], ch. viii. But cf. Morley's chronological scheme, infra; and Spinden [a], pp. 13035.

7. Morley [c], ch. i.

8. Morley [b], p. 140. In this connection (p. 144) Morley summarizes the various speculations as to the causes which led to the abandonment of the southern centres, as reduction of the land by primitive agricultural methods (Cook), climatic changes (Huntington), physical, moral and political decadence (Spinden). He adds: "Probably the decline of civilization in the south was not due to any one of these factors operating singly, but to a combination of adverse influences, before which the Maya finally gave way."

9. The culture heroes of Maya myth have taken possession of the imaginations of the Spanish chroniclers, and indeed of not a few later commentators, rather as clues to native history than to mythology. Bancroft, iii. 450-55, 461-67, summarizes the materials from Spanish sources; which is treated also, from the point of view of possible historical elucidation, by Ancona, I. iii; Carrillo y Ancona, ii, iii; Comte de Charency [b]; Garcia Cubas, in SocAA xxx, nos. 3-6; and Santibaiiez, in CA xvii. 2.

10. The primary sources for the Votan stories are Cogolludo, Ordonez y Aguiar, and Nunez de la Vega, whose narratives are liberally summarized by Brasseur de Bourbourg [a], I. i, ii (pp. 6872 containing the passages from Ordonez here quoted).

11. For Zamna (or Itzamna) the sources are Cogolludo, Landa, and Lizana, summarized by Brasseur de Bourbourg [a], I. pp. 76-80. Quotations are here made from Cogolludo, IV. iii, vi; Brasseur de Bourbourg [f], ii, "Vocabulaire generale"; and Lizana (ed. Brasseur de Bourbourg), pp. 356-59; cf. also Seler [a], index; Landa, chh. xxxv, xxxvi.

12. Identifications of images of Itzamna and Kukulcan are discussed by Dieseldorff, in ZE xxvii. 77083; Spinden [a], pp. 6070; Joyce [b], ch. ix, and Morley [c], pp. 16-19.

13. Cogolludo, Landa, and Lizana are the chief sources for the Kukulcan stories, especially Landa, chh. vi, xl, being here quoted. Tozzer [a], p. 96, is quoted; cf., for Yucatec survival, p. 157.

14. Citations from Landa in this section are from chh. xxvii, xl (which records the new year's festivals), xxxiii (describing the future world), and xxxiv. Landa is our chief source for knowledge of the Yucatec rites and of the deities associated with them; additional or corroborative details being furnished by Aguilar, Cogolludo, Lizana, Las Casas, Ponce, and Pio Perez.

15. Interpretations of the names of the Maya deities, as here given, are from Brasseur de Bourbourg [f], ii, "Vocabulaire"; and Seler [a], index.

16. Lizana (ed. Brasseur de Bourbourg), pp. 36061.

17. Schellhas [b] gives his identifications and descriptions of the gods of the codices; additional materials are contained in Fewkes {i]; Forstemann [b]; Joyce [b], ch. ix; Morley [c], pp. 16-19; Spinden [b], pp. 60-70; and Bancroft, iii, ch. xi.

1 8. Tozzer [a], pp. 150 ff.; also, for the Lacandones, pp. 93-99. The names of the deities, Maya and Lacandone, are here in several cases altered slightly from the form in which Tozzer gives them, for the sake of avoiding the use of unfamiliar phonetic symbols; the result is, of course, phonetic approximation only.

19. Landa, chh. xxvi, xxvii.

20. Las Casas [b], ch. cxxiii.

21. Landa, ch. xxxiv. In chh. iii, xxxii, he gives information in regard to the goddess Ixchel.

NOTES 363

22. The literature of the Maya calendar system is, of course, intimately connected with that of the Mexican (see Note 9, Chapter III). The native sources for its study are the Codices and the monumental inscriptions, while of early Spanish expositions the most important are those of Landa and Pio Perez. In recent times a considerable body of scholars have devoted special attention to the Maya inscriptions and to the elucidation of the calendar, foremost among them being, in America, Ancona, Bowditch, Chavero, Goodman, Morley, Spinden, Cyrus Thomas, and in Europe, Brasseur de Bourbourg, Forstemann, Rosny, and Seler. The foundation of the elucidation of Maya astronomical knowledge is Forstemann's studies of the Dresden Codex, while the study of mythic elements associated with the calendar is represented by Charency, especially "Des ages ou soleils d'apres la mythologie des peuples de la Nouvelle Espagne," section ii, in CA iv. 2; and by J. H. Martinez, "Los Grandes Ciclos de la historia Maya," in CA xvii. 2. Summary accounts of the Maya calendar are to be found in Spinden [a], Beuchat, Joyce [b], Arnold, and Frost, while Bowditch [b] and Morley [c] are in the nature of text-book introductions to the subject.

23. Morley [d], "The Hotun," in CA xix (Washington, 1917).

24. Morley [c], p. 32.

25. Tozzer [a], pp. 153-54.

26. J. Martinez Hernandez, "La Creadon del Mundo segun los Mayas," in CA xviii (London, 1913), pp. 164-71. Senor Hernandez notes that the tense of the verb in the first sentence of the myth is for the sake of literal translation.