|

|

Latin American Mythology

By Hartley Burr Alexander

CHAPTER III

MEXICO Continued

I Cosmogony

II The Four Suns

III The Calendar and its Cycles

IV Legendary History

V Aztec Migration-Myths

VI Surviving Paganism

I. COSMOGONY

1 MEXICAN cosmogonies conform to a wide-spread American type. There is first an ancient creator, little important in cult, who is the remote giver and sustainer of the life of the universe; and next comes a generation of gods, magicians and transformers rather than true creators, who form and transform the beings of times primeval and eventually bring the world to its present condition. The earlier world-epochs, or "Suns," as the Mexicans called them, are commonly four in number, and each is terminated by the catastrophic destruction 'of its Sun and of its peoples, fire and flood overwhelming creation in successive cataclysms. Not all of this, in single completeness, is preserved in any one account, but from the various fragments and abridgements that are extant the whole may be reasonably reconstructed.

One of the simpler tales (simple at least in its transmitted form) is of the Tarascan deity, Tucupacha. "They hold him to be creator of all things," says Herrera, 2 "that he gives life and death, good and evil fortune, and they call upon him in their tribulations, gazing toward the sky where they believe him to be." This deity first created heaven and earth and hell; then he formed a man and a woman of clay, but they were destroyed in bathing; again he made a human pair, using cinders and metals, and from these the world was peopled. But the god sent a flood, from which he preserved a certain priest, Texpi, and his wife, with seeds and with animals, floating in an ark-like log. Texpi discovered land by sending out birds, after the fashion of Noah, and it is quite possible that the legend as recounted is not altogether native.

More primitive in type and more interesting in form is the

Mixtec cosmogony narrated by Fray Gregorio Garcia, which begins

thus: 3" In the year and in the day

of obscurity and darkness, when there were as yet no days nor

years, the world was a chaos sunk in darkness, while the earth

was covered with water, on which scum and slime floated." This

exordium, with its effort to describe the void by negation and

the beginning of time by the absence of its denominations, is

strikingly reminiscent of the creation-narrative in Genesis ii.

and of the similar Babylonian cosmogony; the negative mode,

employed in all three, is essentially true to that stage when

human thought is first struggling to grapple with abstractions,

seeking to define them rather by a process of denudation than by

one of limitation of the field of thought. The Mixtec tale

proceeds with a group of incidents,

(1) The Deer-God and the Deer-Goddess (the deer is an emblem of

fecundity) known also as the Puma-Snake and the Jaguar-Snake, in

which character they doubtless represent the tawny heaven of the

day-sky and the starry vault of night magically raised a cliff

above the abyss of waters, on the summit of which they placed an

axe, edge upward, upon which the heavens rested.

(2) Here, at the Place-where-the-Heavens-stood, they lived many

centuries, and here they reared their two boys,

Wind-of-the-Nine-Serpents and Wind-of-the-Nine-Caves, who

possessed the power of transforming themselves into eagles and

serpents, and even of passing through solid bodies. The symbolism

of these two boys as typifying the upper and the nether world is

obvious; they can only be one more example of the demiurgic twins

common in American cosmogony.

(3) The brothers inaugurated sacrifice and penance, the

cultivation of flowers and fruits; and with vows and prayers they

besought their ancestral gods to let the light appear, to cause

the water to be separated from the earth, and to permit the dry

land to be freed from its covering.

(4) The earth was peopled, but a flood destroyed this First

People, and the world was restored by the "Creator of all

Things."

It is probable that this Mixtec Creator-of-All-Things was the same deity as he who was known to their Zapotec kindred as Coqui-Xee or Coqui-Cilla ("Lord of the Beginning"), of whom it was said that "he was the creator of all things and was himself uncreated." Seler is of opinion that Coqui-Xee is a spirit of "the beginning" in the sense of dawn and the east and the rising sun, and that since he is also known as Piye-Tao, or "the Great Wind," he is none other than the Zapotec Quetzalcoatl, who also is an increate creator. Coqui-Xee, however, is " merely the principle, the essence of the creative deity or of deity in general without reference to the act of creating the world and human beings"; for that act is rather to be ascribed to the primeval pair (equivalent to the Deer-God and Deer-Goddess of the Mixtec), Cozaana ("Creator, the Maker of all Beasts") and Huichaana ("Creator, the Maker of Men and Fishes").

The ideas of the Nahuatlan tribes were similar. Of the Chichimec Sahagun 4 says that " they had only a single god, Mixcoatl, whose image they possessed; but they believed in another invisible god, not represented by any image, called Yoalli Ehecatl, that is to say, God invisible, impalpable, beneficent, protector, omnipotent, by whose strength alone the whole world lives, and who, by his sole knowledge, rules voluntarily all things." Mixcoatl ("Cloud-Snake"), the tribal god of the Chichimec and Otomi, is certainly an analogue of Quetzalcoatl or of Huitzilopochtli, like them figuring as demiurge; and Yoalli Ehecatl ("Wind and Night," or "Night-Wind") is an epithet applied to Tezcatlipoca, who also is addressed as "Creator of Heaven and Earth."

All of these gods are of the sky and atmosphere, and all of them appear as creative powers, though mainly in the demiurgic role. Back of and above them is the ancient Twofold One, the Male-Female or Male and Female principle of generation, which not only first created the world, but maintains it fecund. This being, sometimes called Tloque Nauaque, or "Lord of the By," i. e. the Omnipresent, is represented as a divine pair, known under several names. Sahagun commonly speaks of them asOmetecutli and Omeciuatl ("Twi-Lord," "Twi-Lady "), and in his account of the Toltec he states that they reign over the twelve heavens and the earth; the existence of all things depends upon them, and from them proceeds the "influence and warmth whereby infants are engendered in the wombs of their mothers." Tonacatecutli and Tonacaciutl ("Lord of Our Flesh," "Lady of Our Flesh") is another pair of names, used with reference to the creation of the human body out of maize and to its support thereby. 5 A third pair of terms, appearing in Mendieta and in the Annals of Quauhtitlan, is Citlallatonac and Citlalicue ("Lord" and "Lady of the Starry Zones"). In the Annals Quetzalcoatl, as high-priest of the Toltec, is said to have dedicated a cult to "Citlalicue Citlallatonac, Tonacaciuatl Tonacatecutli . . . who is clothed in charcoal, clothed in blood, who giveth food to the earth; and he cried aloft, to the Omeyocan, to the heaven lying above the nine that are bound together." Nevertheless, these deities or rather deity, for Tloque Nauaque seems to be, like the Zuni Awonawilona, bisexual in nature received little recognition in the formal cult; and it was said that they desired none.

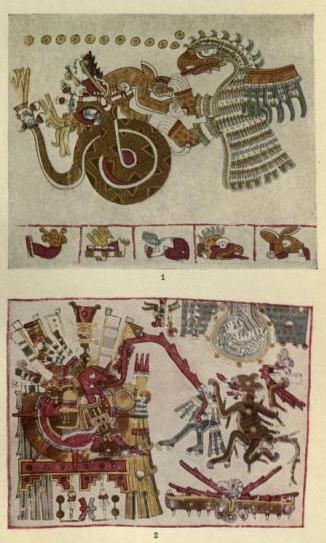

PLATE XII

Figures representing the heavenly bodies.

The upper figure, from Codex Faticanus B, represents the conflict of light and darkness. The Eagle is either the Morning Star or the Sun; the Plumed Serpent is the symbol of the Cosmic Waters, from whose throat the Hare, perhaps the Earth or Moon, is being snatched by the Eagle. Similar figures appear in other codices, the Serpent being in one instance represented as torn by the Eagle's talons.

The lower figure, from Codex Borgia, portrays Sun, Moon, and Morning Star. The Sun-god is within the rayed disk; he holds a bundle of spears in one hand, a spear-thrower in the other; a stream of blood, apparently from a sacrifice offered by the Morning Star, which has the form of an ocelot, nourishes the Sun. The Moon appears as a Hare upon the face of the crescent, which is filled with water and set upon a background of dark sky.

In connexion with these primal creators appear the demiurgic transformers, Quetzalcoatl usually playing the important part. According to Sahagun' s fragmentary accounts, the gods were gathered from time immemorial in a place called Teotiuacan. They asked: "Who shall govern and direct the world? Who will be Sun?" Tecuciztecatl (" Cockle-Shell House") and the pox-afflicted Nanauatzin volunteered. They were dressed in ceremonial garments and fasted for four days; and then the gods ranged themselves about a sacrificial fire, which the candidates were asked to enter. Tecuciztecatl recoiled from the intense heat until encouraged by the example of Nanauatzin, who plunged into it; and because of this Nanauatzin became the Sun, while Tecuciztecatl assumed second place as Moon. The gods now ranged themselves to await the appearance of the Sun, but not knowing where to expect it, and gazing in various directions, some of them, including Quetzalcoatl, turned their faces toward the east, where the Sun finally manifested himself, close-followed by the Moon. Their light being then equal, was so bright that none might endure it, and the deities accordingly asked one another, "How can this be? Is it good that they should shine with equal light?" One of them ran and threw a rabbit into the face of Tecuciztecatl, which thenceforth shone as does now the moon; but since the sun and the moon rested upon the earth, without rising, the gods saw that they must immolate themselves to give motion to the orbs of light. Xolotl fled, but was finally caught and sacrificed; yet even so the orbs did not stir until the wind blew with such violence as to compel them first, the sun, and afterward the moon. Quetzalcoatl, the wind-god, is, of course, thus the giver of life to sun and moon as he is also, in the prayers the bearer of the breath of life from the divine pair to the new-born.

A complete version of the same myth is given by Mendieta,6 who credits it to Fray Andres de Olmos, transmitted by word of mouth from Mexican caciques. Each province had its own narrative, he says, but they were agreed that in heaven were a god and goddess, Citlallatonac and Citlalicue, and that the goddess gave birth to a stone knife (tecpatl), to the amazement and horror of her other sons which were in heaven. The stone hurled forth by these outraged sons and falling to Chicomoxtoc ("Seven Caves"), was shattered, and from its fragments arose sixteen hundred earth-godlings. These sent Tlotli, the Hawk, heavenward to demand of their mother the privilege of creating men to be their servants ; and she replied that they should send to Mictlantecutli, Lord of Hell, for a bone or ashes of the dead, from which a man and woman would be born. Xolotl was dispatched as messenger, secured the bone, and fled with it; but being pursued by the Lord of Hell, he stumbled, and the bone broke. With such fragments as he could secure he reached the earth, and the bones, placed in a vessel, were sprinkled with blood drawn from the bodies of the gods. On the fourth day a boy emerged from the mixture; on the eighth, a girl; and these were reared by Xolotl to become parents of mankind. Men differ in size because the bone broke into unequal fragments; and as human beings multiplied, they were assigned as servants to the several gods. Now, the Sun had not been shining for a long time, and the deities assembled at Teotiuacan to consider the matter. Having built a great fire, they announced that that one among their devotees who should first hurl himself into it should have the honour of becoming the Sun, and when one had courageously entered the flames, they awaited the sunrise, wagering as to the quarter in which he would appear; but they guessed wrong, and for this they were condemned to be sacrificed, as they were soon to learn. When the Sun appeared, he remained ominously motionless; and although Tlotli was sent to demand that he continue his journey, he refused, saying that he should remain where he was until they were all destroyed. Citli ("Hare") in anger shot the Sun with an arrow, but the latter hurled it back, piercing the forehead of his antagonist. The gods then recognized their inferiority and allowed themselves to be sacrificed, their hearts being torn out by Xolotl, who slew himself last of all. Before departing, however, each divinity gave to his followers, as a sacred bundle, his vesture wrapped about a green gem which was to serve as a heart. Tezcatlipoca was one of the departed deities, but one day he appeared to a mourning follower whom he commanded to journey to the House of the Sun beyond the waters and to bring thence singers and musical instruments to make a feast for him. This the messenger did, singing as he went. The Sun warned his people not to harken to the stranger, but the music was irresistible, and some of them were lured to follow him back to earth, where they instituted the musical rites. Such details as the formation of the ceremonial bundles and the journey of the song-seeker to the House of the Sun immediately suggest numerous analogues among the wild tribes of the north, indicating the primitive and doubtless ancient character of the myth.

II. THE FOUR SUNS

7 In the developed cosmogonic myths the cycles, or "Suns," of the early world are the turns of the drama of creation. Ixtlilxochitl names four ages, following the creation of the world and man by a supreme god, "Creator of All Things, Lord of Heaven and Earth." Atonatiuh, "the Sun of Waters," was the first age terminated by a deluge in which all creatures perished. Next came Tlalchitonatiuh, "the Sun of Earth"; this was the age of giants, and it ended with a terrific earthquake and the fall of mountains. "The Sun of Air," Ehcatonatiuh, closed with a furious wind, which destroyed edifices, uprooted trees, and even moved the rocks. It was during this period that a great number of monkeys appeared "brought by the wind," and these were regarded as men changed into animals. Quetzalcoatl appeared in this third Sun, teaching the way of virtue and the arts of life; but his doctrines failed to take root, so he departed toward the east, promising to return another day. With his departure "the Sun of Air" came to its end, and Tlatonatiuh, "the Sun of Fire," began, so called because it was expected that the next destruction would be by fire.

Other versions give four Suns as already completed, making the present into a fifth age of the world. The most detailed of these cosmogonic myth-records is that given in the Historia de los Mexicanos por sus pinturas. According to this document Tonacatecutli and Tonacaciuatl dwelt from the beginning in the thirteenth heaven. To them were born, as to an elder generation, four gods the ruddy Camaxtli (chief divinity of the Tlascalans); the black Tezcatlipoca, wizard of the night; Quetzalcoatl, the wind-god; and the grim Huitzilopochtli, of whom it was said that he was born without flesh, a skeleton. For six hundred years these deities lived in idleness; then the four brethren assembled, creating first the fire (hearth of the universe) and afterward a half-sun. They formed also Oxomoco and Cipactonal, the first man and first woman, commanding that the former should till the ground, and the latter spin and weave; while to the woman they gave powers of divination and grains of maize that she might work cures. They also divided time into days and inaugurated a year of eighteen twenty-day periods, or three hundred and sixty days. Mictlantecutli and Mictlanciuatl they created to be Lord and Lady of Hell, and they formed the heavens that are below the thirteenth storey of the celestial regions, and the waters of the sea, making in the sea a monster Cipactli, from which they shaped the earth. The gods of the waters, Tlaloctecutli and his wife Chalchiuhtlicue, they created, giving them dominion over the Quarters. The son of the first pair married a woman formed from a hair of the goddess Xochiquetzal; and the gods, noticing how little was the light given forth by the half-sun, resolved to make another half-sun, whereupon Tezcatlipoca became the sun-bearer for what we behold traversing the daily heavens is not the sun itself, but only its brightness; the true sun is invisible. The other gods created huge giants, who could uproot trees by brute force, and whose food was acorns. For thirteen times fifty-two years, altogether six hundred and seventy-six, this period lasted as long as its Sun endured; and it is from this first Sun that time began to be counted, for during the six hundred years of the idleness of the gods, while Huitzilopochtli was in his bones, time was not reckoned. This Sun came to an end when Quetzalcoatl struck down Tezcatlipoca and became Sun in his place. Tezcatlipoca was metamorphosed into a jaguar (Ursa Major) which is seen by night in the skies wheeling down into the waters whither Quetzalcoatl cast him; and this jaguar devoured the giants of that period. At the end of six hundred and seventy-six years Quetzalcoatl was treated by his brothers as he had treated Tezcatlipoca, and his Sun came to an end with a great wind which carried away most of the people of that time or transformed them into monkeys. Then for seven times fifty-two years Tlaloc was Sun; but at the end of this three hundred and sixty-four years Quetzalcoatl rained fire from heaven and made Chalchiuhtlicue Sun in place of her husband, a dignity which she held for three hundred and twelve years (six times fifty-two) ; and it was in these days that maize began to be used. Now two thousand six hundred and twenty-eight years had passed since the birth of the gods, and in this year it rained so heavily that the heavens themselves fell, while the people of that time were transformed into fish. When the gods saw this, they created four men, with whose aid Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl again upreared the heavens, even as they are today; and these two gods becoming lords of the heavens and of the stars, walked therein. After the deluge and the restoration of the heavens, Tezcatlipoca discovered the art of making fire from sticks and of drawing it from the heart of flint. The first man, Piltzintecutli, and his wife, who had been made of a hair of Xochiquetzal, did not perish in the flood, because they were divine. A son was born to them, and the gods created other people just as they had formerly existed. But since, except for the fires, all was in darkness, the gods resolved to create a new Sun. This was done by Quetzalcoatl, who cast his own son, by Chalchiuhtlicue, into a great fire, whence he issued as the Sun of our own time; Tlaloc hurled his son into the cinders of the fire, and thence rose the Moon, ever following after the Sun. This Sun, said the gods, should eat hearts and drink blood, and so they established wars that there might be sacrifices of captives to nourish the orbs of light. Most of the other versions of the myth of the epochal Suns similarly date the beginning of sacrifice and penance from the birth of the present age.

The Annals of Quauhtitlan gives a somewhat different picture of the course of the epochs. Each epoch begins on the first day of Tochtli, and the god Quetzalcoatl figures as the creator. Atonatiuh, the first Sun, ended with a flood and the transformation of living creatures into fish. Ocelotonatiuh, the Jaguar Sun," was the epoch of giants and of solar eclipse. Third came "the Sun of Rains," Quiyauhtonatiuh, ending with a rain of fire and red-hot rocks ; only birds, or those transformed into them, and a human pair who found subterranean refuge, escaped the conflagration. The fourth, Ecatonatiuh, is the Sun of destruction by winds; while the fifth is the Sun of Earthquakes, Famines, Wars, and Confusions, which will bring our present world to destruction. The author of the Spiegazione delle tavole del codice mexicano (Codex Vaticanus A) not consistent with himself, for in his account of the infants' limbo he makes ours the third Sun changes the order somewhat: first, the Sun of Water, which is also the Age of Giants; second, the Sun of Winds, ending with the transformation into apes; third, the Sun of Fire; fourth, the Sun of Famine, terminating with a rain of blood and the fall of Tollan. Four Suns passed, and a fifth Sun, leading forward to a fifth eventual destruction, seems, most authorities agree, to represent the orthodox Mexican myth; though versions like that of Ixtlilxochitl represent only three as past, while others, as Camargo's account of the Tlascaltec myth, make the present Sun the third in a total of four that are to be. Probably one cause of the confusion with respect to the order of the Suns is the double association of Quetzalcoatl first, with the Sun of Winds, which he, as the Wind-God, would naturally acquire; and second, with the fall of Tollan and of the Toltec empire, for Quetzalcoatl, with respect to dynastic succession, is clearly the Toltec Zeus. The Sun of Winds is normally the second in the series ; the fall of Tollan is generally associated with the end of the Sun last past: circumstances which may account for the shortened versions, for it seems little likely (judging from American analogies) that the notion of four Suns passed is not the most primitive version.

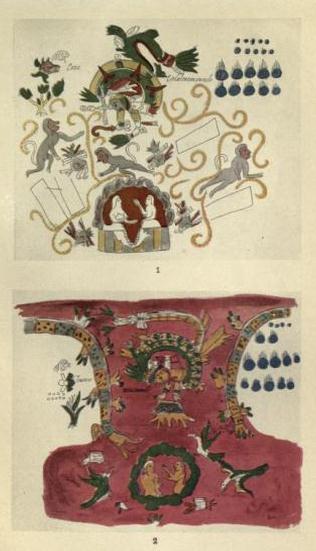

PLATE XIII

Figures from Codex Faticanus A representing cataclysms bringing to an end cosmic "Suns," or Ages of the World.

The upper figure represents the close of the Sun of Winds, ending with the transformation of men, save for an ancestral pair, into apes. The lower pictures the end of the Sun of Fire, whence only birds and a human pair in a subterranean retreat escaped.

Another myth confusedly associated now with the Sun of Waters, now with the Sun last past, is the story of the deluge. In the pattern conception (if it may so be termed) each Sun begins with the creation or appearance of a First Man and First Woman and ends with the salvation of a single human pair, all others being lost or transformed. The first Sun ends with a deluge and the metamorphosis of the First Men into fish; but a single pair escaped by being sealed up in a log or ark. In the Chimalpopoca (Quauhtitlan) version given by Brasseur de Bourbourg it is related that the waters had been tranquil for fifty-two years; then, on the first day of the Sun, there came such a flood as submerged even the mountains, and this endured for fifty-two years.

Warned by Tezcatlipoca, however, a man named Nata, with Nena his wife, hollowed a log and entered therein; and the god closed the port, saying, "Thou shalt eat but a single ear of maize, and thy wife but a single ear also." When the waters subsided, they issued from their log, and seeing fish about, they built a fire to roast them. Citlallatonac and Citlalicue, beholding this from the heavens, said: "Divine Lord, what is this fire? Wherefore does this smoke cloud the sky?" Whereupon Tezcatlipoca descended in anger, crying, "What fire is this?" And he seized the fishes and transformed them into dogs. Certainly one would relish an elaboration of this tale; for it would seem that a theft of the fire must precede perhaps a suffering Prometheus may have followed the anger of the gods. In another version the Mexican Noah is named Coxcox, his wife bears the name of Xochiquetzal ; and it is said that their children, born dumb, received their several forms of speech from the birds. Now Xochiquetzal is associated (doubtless as a festal goddess) with Tollan and the age in which she appears is the last of all, that in which Tollan is destroyed; whence the deluge is placed at the end of the fourth Sun.

To the same group of events the passing of Tollan and the deluge belong the stories of the building of the great pyramid of Cholula and the portents which accompanied it. It is said 8 that, reared by a chief named Xelua, who escaped the deluge, it was built so high that it appeared to reach heaven; and that they who reared it were content, " since it seemed to them that they had a place whence to escape from the deluge if it should happen again, and whence they might ascend into heaven"; but "a chalcuitl, which is a precious stone, fell thence [i. e. from the skies] and struck it to the ground; others say that the chalcuitl was in the shape of a toad; and that whilst destroying the tower it reprimanded them, inquiring of them their reason for wishing to ascend into heaven, since it was sufficient for them to see what was on the earth." It is worth while to remember that the hybristic scaling of heaven is no uncommon motive in American Indian myth, while the moral of the tale is honestly pagan " mortal things are the behoof of mortals," saith Pindar; nor can we fail to see in the green jewel the jealous Earth-Titaness, for the toad is Earth's symbol.

The duration of the cosmic Suns is given various values by the recorders of the myths. These, no doubt, issued from variations in calendric computations; for the Mexicans not only possessed an elaborate calendar; they also used it, in its involved circles of returning signs, as the foundation for calculating the cycles of cosmic and of human history. It is essential, therefore, if the genius of Mexican myth be fully grasped, that the elements of its calendar be made clear.

III. THE CALENDAR AND ITS CYCLES

9 The Mexican calendar is one of the most extraordinary inventions of human intelligence. Elsewhere the science of the calendar is a lore of sun, moon, and stars, and of their synodic periods; in the count of time astronomy is mistress, and number is but the handmaiden. In the Mexican system this relation is distinctly reversed: it is number that is dominant, and astronomy that is ancillary. One might, indeed, add that the number is geometric. It is common enough elsewhere to find the measures of space influencing the measures of time, but ordinarily they are the measures of celestial, not of terrestrial, space; and they are, therefore, moving, and not stationary, numbers. In the Mexican system the controlling numerical ideas appear to be the 4 (5) and the 6 (7) of the world-quarters these in their duplicate forms, 9 (= 2 X 4 + 1) and 13 (=2x64-1) and all are under the domination of the four by five digits (two fives of fingers and two of toes) of their vigesimal system of counting. Man in the Middle Place of his cosmos; oriented to the rising Sun; four-square with the Quarters, which are duplicate in the Above and the Below; counting his natural days by his natural digits: this is the image which makes most plausible our explanations of the peculiarly earth-tethered calendar of the Mexicans, and, in consequence, of a cosmographical rather than an astrological conception of the Fates and Influences.

Not that the moving heavens were without computation: astronomy, though secondary, was indispensable. 10 The day, of course, is the creation of the journey of the sun; and the day, as a time-unit, plays in the Mexican count a part altogether commensurate in importance with that given to the sun in myth and ritual. The moon, though far less prominent in every respect, is still conspicuously figured. The morning star (far and wide a great deity of the American Indian nations) was second in significance only to the sun; indeed, one of the most extraordinary achievements of aboriginal American science was the identification of Phosphorus and Hesperus as the same star, and the computation of a Venus-period of five hundred and eighty-four days (the exact period being five hundred and eighty-three days and twenty-two hours).

Comets and meteors were regarded as portents; the Milky Way was the skirt of Citlalicue, or was the white hair of Mixcoatl of the Zenith; and in the patterns of the stars were seen the figures that define the topography of the nocturnal heavens. Sahagun mentions three constellations, which he vaguely identifies with Gemini, Scorpio, and Ursa Minor; and in the chart of heavenly bodies, given with his Nahuatlan text, he figures two other stellar groups; while five is the number which Tezozomoc names as those for which the king elect must keep watch on the night of his vigil. Doubtless many other star-patterns were observed, but these five seem predominant. Stansbury Hagar, resolving what he regards as the Mexican Scorpio into Scorpio and Libra, would see in Sahagun's figures half of the zodiacal twelve; and in both Mexico and Peru he believes that he has identified a series of signs closely equivalent to that of the Old World zodiac. Another view (presented by Zelia Nuttall) conceives the Aztec constellations as forming a series of twenty, corresponding to the twenty day-signs employed in the calendar. A third interpretation, on the whole, accordant with the evidence, is that of Seler, who maintains that the five constellations named by Sahagun and Tezozomoc represent, instead of a zodiac, the four quarters and the zenith of the sky-world, and are, therefore, spatial rather than temporal guides. Seler identifies Mamalhuaztli, "the Fire-Sticks," with stars of the east, in or near Taurus. The Pleiades, rising in the same neighbourhood, he believes to have been the sign of the zenith; and at the beginning of a new cycle of fifty-two years the new fire was kindled when the Pleiades were in the zenith at midnight the very hour, according to Tezozomoc, when the king rises to his vigil. Citlalachtli, "the Star Ball-Ground," is called "the North and its Wheel" by Tezozomoc, and must refer to the stars which revolve about the northern pole. Colotlixayac, "Scorpion-Face," marks the west; while Citlalxonecuilli so named, Sahagun tells us, from its resemblance to S-shaped loaves of bread which were called xonecuilli is clearly identified by Tezozomoc with the Southern Cross and adjacent stars. Thus it appears (granting Seler's interpretation) that the constellations served but to mark the pillars of this four-square world.

Essentially the Mexican calendar is an elaborate daycount. As with many other American peoples, the system of notation was vigesimal (probably developed from a quinary mode of counting), and the days were accordingly reckoned by twenties: twenty pictographs served as day-signs, endlessly repeated like the names of the days of the week. These twenty-day periods are commonly called "months" (following the usage of Spanish writers), though they have no relation to the moon and its phases; they are, however, like our months, used as measures of the primitive solar year of three hundred and sixty-five days, the Aztec year comprising eighteen months (or sets of twenties) plus five nemontemi, or "Empty Days," regarded as unlucky. According to Sahagun, six nemontemi were counted every fourth year; if this were true (it is widely doubted), the Mexicans would have had a calendar which was Julian in effect. Like our months, each of the eighteen twenties of the solar year had its own name and its characteristic religious festivals; during the nemontemi there were neither feasts nor undertakings. The beginning of the solar year is placed by Sahagun on the first day of the month Atlcaualco corresponding, he says, to February 2 the period of the cessation of rains, and the time of rites in honour of Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue. Some authorities, however, believe that the year really began with Toxcatl, corresponding to the earlier part of May, the period of the celebration of the great festival of Tezcatlipoca, when his personator was sacrificed and the next year's victim was chosen. The location of the nemontemi in the year is not certain.

From the fact that to the days of the year were assigned twenty endlessly repeating signs, and the further fact that the nemontemi were five in number (18 X 20 + 5 = 365), it follows that the first day of the year would always fall upon one of four signs; and these signs Calli ("House"), Tochtli ("Rabbit"), Acatl ("Reed"), and Tecpatl ("Flint") inevitably became emphasized in the imagination, not only with units of time, but also with the Quarters which divide the world.

But the designation of the days was not simply by the series of pictographic signs. An additional series was formed of the numbers one to thirteen, which, like the signs, were repeated over and over; so that each day had not only a sign, but also a number. Since only thirteen numerals were employed, it follows that if any given twenty days have the number one accompanying the sign of its first day, the sign of the first day of the ensuing twenty days will be accompanied by the number eight, the sign of the first day of the third twenty by two, and so on; not until the end of two hundred and sixty days (since thirteen is a prime number) will the same number recur with the initial sign. The representation of this period of thirteen by twenty days, in which the cycles of numerals and pictographs passed from an initial correspondence to its first recurrence, was called by the Aztec the Tonalamatl, or "Book of Good and Bad Days" a set of signs employed for divination as the name implies. Since the Tonalamatl represents only two hundred and sixty days, it follows that the last one hundred and fifteen days of the year will have the same signs and numerals as the first one hundred and fifteen. For this reason De Jonghe and some others believe that a third set of day-signs was employed the nine Lords of the Night, which (since two hundred and sixty is not evenly divisible by nine) would suffice to differentiate the days throughout the year. Seler, however maintains that he has disproved this theory; if so, there would still be the possibility of differentiating the days of the second Tonalamatl from those of the first by employing the sign of that one of the eighteen "months" in which the day fell.

PLATE XIV

The Aztec "Calendar Stone," one of the two monuments (see Plate V for the other) found beneath the pavement of the plaza of the city of Mexico in 1790. The outer band of decoration is formed of two "Fire Snakes" (cf. Plates VII 3 and XXI), each with a human head in its mouth; between the tips of the serpents' tails is a glyph giving the date, 13 Acatl, of the historical Sun, that is, the beginning of the present Age of the World. A decorative band formed of the twenty day signs surrounds the central figure, which consists of a Sun-face, with the glyph 4 Olin; while in the four adjacent compartments are the names of the eras of the four earlier "Suns." Sun rays, with other figures, appear in the spaces between the inner and outer decorative bands. Below is given a key (after Joyce, Mexican Archaeology, page 74).

In addition to the Tonalamatl, there is another consequence of the double designation of the days. Each year, it has been noted, begins with one of four day-signs. But three hundred and sixty-five is indivisible, evenly, by thirteen; therefore, the day-signs and numerals for succeeding years must vary, the day-signs recurring in the same order every four years, and the numerals in the same order every thirteen years (since 365 = 13 X 28 + i), while not until there has elapsed four times thirteen years will the same day-sign and the same numeral occur on the first day of the year. These divisions of the years into groups, determined by their signs and numbers, were of great significance to the Mexican peoples. The sign which began each group of thirteen years was regarded as dominant during that period, and as each of these signs was dedicated to one of the four Quarters, it is to be supposed that the powers of the ruling sign determined the fortunes of the period. The cycle was complete when, at the end of fifty-two years, the same sign and number recurred as the emblem of the year. Such an epoch was the occasion for prognostics and dread anticipations, and it was celebrated with a special feast at which all fires were eKtinguished and a new flame was kindled on the breast of a sacrificial victim. This festival was called "the Knot of the Years," and in Aztec pictography past periods were represented by bundles, each signifying such a cycle of fifty-two years.

It will be noted that the fifty-two year cycle is also the period for the recurring coincidence of the day-signs and numerals in the year and in the Tonalamatl (for, 365 factoring 73 X 5, and 260 factoring 52 X 5, it follows that 52 years will equal 73 Tonalamatls). It is, therefore, the more extraordinary that in the usual mode of figuring the Tonalamatl it is begun, not with one of the four signs which name the years and their cycles, but with another day-sign, Cipactli ("Crocodile"). The plausible explanation of this is that since the Crocodile was the monster from which Earth was formed by the creative gods, the divinatory period was inaugurated under his sign.

The origin of so peculiar a reckoning as the Tonalamatl is one of the puzzles of Americanist studies. Effort has been made to connect it with lunar movements, but no astronomical period corresponds with it. Again, it has been pointed out that the two hundred and sixty days of the Tonalamatl approximate the period of gestation, and in view of its use, for divinations and horoscopic forecasts, this is not impossible as an explanation of its origin. The obvious fact that it expresses the cycle of coincidence of the twenty day-signs and thirteen numerals only carries the puzzle back to the origination of the numeration, with its anomalous thirteen for which, as a significant number, no more satisfactory astronomical reason has been suggested than Leon y Gama's, that it represents half of the period of the moon's visibility. In myth the invention of the Tonalamatl is ascribed to Cipactonal and Oxomoco (in whom Senor Robelo sees the personification of Day and Night), and again to Quetzalcoatl. At his immolation the heart of Quetzalcoatl, it will be recalled, flew upward to become the Morning Star, and in special degree the god is associated with this star. "They said that Quetzalcoatl died when the star became visible, and henceforward they called him Tlauizcalpantecutli, 'Lord of the Dawn.' They said that when he died he was invisible for four days; they said he wandered in the underworld, and for four days more he was bone. Not until eight days were past did the great star appear. Quetzalcoatl then ascended the throne as god." One of the early writers, Ramon y Zamora, states that the Tonalamatl was determined by the Mexicans as the period during which Venus is visible as the evening star; and Forstemann discovered representations of the Venus-year of five hundred and eighty-four days divided into periods of ninety, two hundred and fifty, eight, and two hundred and thirty-six days, which he estimated to represent respectively the period of Venus's invisibility during superior conjunction (ninety days), of its visibility as evening star (two hundred and fifty days), of its invisibility during inferior conjunction (eight days), and of its visibility as morning star (two hundred and thirty-six days).

The near correspondence of the period of two hundred and fifty days with the Tonalamatl, coupled with the identity of the eight days' invisibility with the period of Quetzalcoatl's wandering and lying dead in the underworld, which was followed by his ascension to the throne of the eastern heaven, as related in the myth, give plausibility to the traditions which associate the formation of the Tonalamatl with the Venus-period. Seler suggests and this is perhaps the best explanation yet offered that the Tonalamatl is the product of an indirect association of the solar year (three hundred and sixty-five days) and of the Venus-period (five hundred and eighty-four days), for the least common multiple of the numbers of days in these two periods is twenty-nine hundred and twenty days, equal to eight solar years and five Venus years; in associating the two, he says, the inventors of the calendar lighted upon the number thirteen (8 + 5), and hence upon the Tonalamatl of two hundred and sixty days. If this be the case, the belief in thirteen heavens and thirteen hours of the day would be derivative from temporal rather than spatial observations, from astronomy rather than cosmography. A somewhat analogous association might be offered in connexion with the nine of the heavens and the nine of the hours of the night; for just as there are four signs that always recur as the designations of the solar years, so for the Venus-period there are five (since five hundred and eighty-four divided by twenty leaves four as divisor of the signs), and the sum of these is nine.

The signs which inaugurate the Venus periods are Cipactli ("Crocodile"), Coatl ("Snake"), Atl ("Water"), Acatl ("Reed"), and Olin ("Motion"). But here again the numerals enter in to complicate the series, so that while the day-signs which inaugurate the Venus-periods recur in groups of five, they do not recur with the same numeral until the lapse of thirteen times five periods. This great cycle of Venus-days, comprising sixty-five repetitions of the apparent course of the planet, is also a common multiple of the solar year and of the Tonalamatl, comprising one hundred and four of the former and one hundred and forty-six of the latter. Thus it was that at the end of one hundred and four years of three hundred and sixty-five days the same sign and number-series recurred in the three great units of the Aztec calendar. When it is remembered that prognostics were to be drawn not merely from the complex relations of the signs to their place in each of the three time-units, with their respective elaborations into cycles; but from their further relations with the regions of the upper and lower worlds, and also from the numerals, which had good and evil values of their own, it will be seen that the Mexican priests were in possession of a fount of craft not second to that of the astrologers of the Old World.

That so complex a system could easily give rise to error is evident, and it is probable that, as tradition asserts, from time to time corrections were made, serving as the inauguration of new "Suns" or as new "inventions" of time. It may even be that the "Suns" of the cosmogonic myths are reminiscences of calendric corrections, and it is at least a striking coincidence that the traditions of these "Suns" make them four in number, like the year-signs, or five in number, like the Venus-signs. The latter series, too, is distinctly cosmogonic in symbolism Crocodile suggests the creation from a fish-like monster; Snake, the falling heavens; Water, the "Water-Sun" and the deluge; Reed (the fire-maker), the Sun of Fire; Motion, the Sun of Wind, or perhaps the Earthquake. But whatever be the value of these symbolisms, it is certain thatMexicans themselves associated perilous times and cataclysmic changes with the rounding out of their cycles.

IV. LEGENDARY HISTORY

The cosmogonic and calendric cycles (intimately associated)

profoundly influenced the Mexican conception of history. Orderly

arrangement of time is as essential to an advancing civilization

as the ordering of space, and it is natural for the human

imagination to form all of its temporal conceptions into a single

dramatic unity a World Drama, with its Creation, Fall,

Redemption, and Judgement; or a Cosmic Evolution from Nebula to

Solar System, and Solar System to Nebula. In the making, such

cosmic dramas start from these roots:

(1) Cosmogony and Theogony, for which there is no simpler image

in nature than the creation of the Life of Day from the Chaos of

Night at the command of the Lord of Light;

(2) "Great Years," or calendric cycles, formed by calculations of

the synodic periods of sun and moon and wandering stars, or, as

in the curious American instance, mainly from simple day-counts

influenced by a complex symbolism of numbers and by an awkward

notation;

(3) the recession of history, back through the period of record

to that of racial reminiscence and of demigod founders and

culture-heroes. Of these three elements, the first and third

constitute the material, while the second becomes the form-giver

the measure of the duration of the acts and scenes of the drama,

as it were adding, however, on the material side, the portents

and omens imaged in the stars.

The Mexican system of cosmic Suns is a capital example of the first element each Sun introducing a creation or restoration, and each followed by an elemental destruction, while all are meted out in formal cycles. It is no matter for wonder that there are varying versions of the order and number of the cosmogonic cycles, nor that a nebulous and legendary history is varyingly fitted into the cyclic plan; for each political state and cultural centre tended to develop its own stories in connexion with its own records and traditions. Nevertheless, there is a broad scheme of historic events common to all the more advanced Nahuatlan peoples, the uniformity of which somewhat argues for its truly historic foundation. This is the legend which assigns to the plateau of Anahuac three successive dominations, that of the Toltec, that of the Chichimec nations, and that of the Aztec and their allies. Although the remote Toltec period is clouded in myth, archaeology tends to support the truth of the tales of legendary Tollan, at least to the extent of identifying the site of a city which for a long period had been the centre of a power that was, by Mexican standards, to be accounted civilized.

The general characters of Toltec civilization, as tradition shows it, are those recorded by Sahagun. 11 The Toltec were clever workmen in metals, pottery, jewellery, and fabrics, indeed, in all the industrial arts. They were notable builders, adorning the walls of their structures with skilful mosaic. They were magicians, astrologers, medicine-men, musicians, priests, inventors of writing, and creators of the calendar. They were mannerly men, and virtuous, and lying was unknown among them. But they were not warlike and this was to be their ruin.

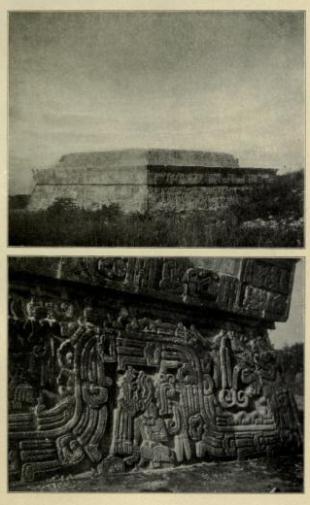

PLATE XV

The temple of Xochicalco, partially restored. The relief band, of which a section is given for detail, shows a serpent; a human figure, doubtless a deity, is seated beneath one of the great coils. After photographs in the Peabody Museum.

Their principal deity was Quetzalcoatl, and his chief priest bore the same name. The temple of the god was the greatest work of their hands. It was composed of four chambers : that to the east, of gold; that to the west, encrusted with turquoise and emerald; that to the south, with sea-shells and silver; that to the north, with reddish jasper and shell. In another similar shrine, plumage of the several colours adorned the four apartments. The explicator of Codex Vaticanus A says that Quetzalcoatl was the inventor of round temples (it is possible that the rotundity of his shrines was due to the presumption that the wind does not love corners), and that he founded four; in the first princes and nobles fasted; the second was frequented by the lower classes; the third was "the House of the Serpent," and here it was unlawful to lift the eyes from the ground; the fourth was "the Temple of Shame," where were sent sinners and men of immoral life. Details such as these obviously referring to familiar features of American Indian ritual as well as the numerous myths that narrate the departure of Quetzalcoatl for the mysterious Tlapallan, followed by a great part of the Toltec population, clearly belong in the realm of fancy, shimmeringly veiling historic facts. Thus, when Ixtlilxochitl states that the reign of each Toltec king was just fifty-two years, we see simply a statement which identifies calendric with political periods; yet when he goes on with the qualification that those kings who died under such a period were replaced by regents until a new cycle could begin with the election of a new king, and when he specifically notes that, as exceptions, Ilacomihua reigned fifty-nine years, and Xiuhquentzin, his queen, four years after him, we are in the presence of a tradition which looks much more like history than myth for there is no mythic reason that satisfies this shift. Fact, too, should underlie Sahagun's naive remark that the Toltec were expert in the Mexican tongue, although they did not speak it with the perfection of his day, and again that communities which spoke a pure Nahua were composed of descendants of Toltecs who remained in the land when Quetzalcoatl departed for behind such notions should lie a story of linguistic supersession.

Such, indeed, appears to have been the course of events. The date of the founding of Tollan, according to the Annals of Quauhtitlan, is, computed in our era, 752 A. D. Ixtlilxochitl puts the beginning of the Toltec kingship as early as 510 A. D.; and the end he sets in the year 959, when the last Toltec king, Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, was overthrown and departed, none knew whither. It is a plausible hypothesis which assumes the historicity of this event and which accounts for the myths of the departure of Quetzalcoatl, the god, as due in part to a con- fusion of the permutations of a nature deity with the gesta of an earthly hero a process exemplified in the Old World in the tales of King Arthur, Celtic god and British hero-king. It is certain that from an early date the civilization of the Mexican plateau was racially akin to that of the Maya in the south ; it is not improbable that the Toltec represent an ancient northern extension of Maya power (the oldest stratum at Tollan shows Huastec influences, and the Huastec are of Maya kin); and, finally, when the political overthrow of the Toltec was accomplished, and their leaders fled away to Tlapallan, to the south-east, the northern barbarians who had replaced them gradually learned the lesson of civilization from the sporadic groups which remained in various centres after the capital had fallen Cholula, Cuernavaca, and Teotihuacan, cities which were to figure in Nahuatlan lore as the centres of priestly learning. Such an hypothesis would account for Sahagun's statement that the Toltec spoke Nahua imperfectly, for those who remained would have changed to this language; while what may well be an historical incident of the period of change is Ixtlilxochitl's account of the reply of the Toltec king of Colhuacan to the invading Chichimec, refusing to pay tribute, for "they held the country from their ancestors, to whom it belonged, and they had never obeyed or payed tribute to any foreign lord . . . nor recognized other master than the Sun and their gods." However, less able in arms than the invaders, they fell to no great force.

The Chichimec, according to the prevailing accounts, were a congeries of wild hunting tribes, cave-dwellers by preference, who vaguely and imperfectly absorbed the culture that had preceded them in the Valley of Mexico. Ixtlilxochitl has it that, under the leadership of a chief named after the celestial dog Xolotl, they entered the Toltec domain a few years after the fall of Tollan, peaceably possessing themselves of an almost deserted land. They were soon followed by related tribes, among whom the most important were the Acolhua, founders of Tezcuco; while later came the Mexicans, or Aztec, who wandered obscurely from place to place before they finally established the town which was to be the capital of their empire. For several centuries, as the chronicler pictures it, these related peoples warred and quarrelled turbulently, owning the shadowy suzerainty of "emperors" whose power waxed or waned with their personal force altogether such a picture as is presented by Mediaeval Europe after the recession of the Roman Empire before the incursive barbarians. Gradually, however, just as in Europe, the seed of the elder civilization took root, and the culture which the Spaniards discovered grew and consolidated.

Its leaders were not the Aztec, but the related Acolhua, whose capital, Tezcuco, became the Athens of an empire of which Tenochtitlan was to be the Rome; and the great age of Tezcuco came with King Nezahualcoyotl, less than a century before the appearance of Cortez. Cautious writers point to the resemblances between the career and character of this monarch as pictured by Ixtlilxochitl, and that of the Scriptural David: both, in their youth, are hunted and persecuted by a jealous king, and are forced into exile and outlawry; both triumphantly overthrow their enemies and inaugurate reigns of splendour, erecting temples, cultivating the arts, and reforming the state; both are singers and psalmists, and prophets of a purified monotheism; both assent to the execution of an eldest son and heir because of palace intrigue; and, finally, both, in the hour of temptation, cause an honoured thane to be treacherously slain in order that they may possess themselves of a woman who has captivated their fancy. In each case, too, the queen dishonourably won becomes the mother of a successor whose reign is followed by a decline of power, for Nezahualpilli was the last of the great Tezcucan kings. Certainly the parallels are striking and the chronicler may well have been influenced by Biblical analogy in the form which he gives his stories; but it is surely not unfair to remark that such repetitions of event are to be expected in a world whose possibilities are, after all, limited in number; that, for example, a whole series of similarities can be drawn between Inca and Aztec history (where there is no suspicion of influence), and that there are not a few striking likenesses of the characters of Nezahualcoyotl and Huayna Capac, to both of whom is ascribed an enlightened monotheism. Various fragments of Nezahualcoyotl's poems or such as bear his name have survived, among them a lament which has the very tone of the Aztec prayers preserved by Sahagun, and which, indeed, breathes the whole world-weary dolour of Nahuatlan religion.12

"Harken to the lamentations of Nezahualcoyotl, communing with himself upon the fate of Empire spoken as an example to others !

"O king, inquiet and insecure, when thou art dead, thy vassals shall be destroyed, scattered in dark confusion; on that day ruler-ship will no longer be in thy hand, but with God the Creator, All-Powerful.

"Who hath beheld the palace and court of the king of old, Tezozomoc, how flourishing was his power and firm his tyranny, now-overthrown and destroyed will he think to escape? Mockery and deceit is this world's gift, wherefore let all be consumed !

"Dismal it is to contemplate the prosperity enjoyed by this king, even to his senility, like an old willow, animated by desire and by ambition, uplifting himself above the weak and humble. Long time did the green and the flowers offer themselves in the fields of spring-time, but at last, worm-eaten and dried, the wind of death seized him, uprooted him, and scattered him in fragments on Earth's soil. So, also, the olden king Cozastli passed onward, leaving neither house nor lineage to preserve his memory.

"With such reflections, with melancholy song, I bring again the memory of the flowery springtime gone, and of the end of Tezozomoc who so long knew its joys. Who, barkening, shall withhold his tears?

Abundance of riches and varied pleasures, are they not like culled flowers, passed from hand to hand, and at the end cast forth stripped and withered?

" Sons of kings, sons of great lords, give heed and consideration to what is made manifest in my sad and lamenting song, as I relate how passed the flowery springtime and the end of the powerful king Tezozomoc! Ah, who, harkening, will be hard enough to restrain his tears for all these varied flowers, these pleasures sweet, wither and end with this passing life!

"Today we possess the abundance and beauty of the blossoming summer, and harken to the melody of birds, where the butterflies sip sweet nectar from fragrant petals. But all is like culled flowers, that pass from hand to hand, and at the end are cast forth, stripped and withered!"

V. AZTEC MIGRATION-MYTHS

13 Common tradition makes of the Aztec, or Mexica, late comers into the central valley, although they are regarded as belonging to the general movement of tribes known as the Chichimec immigration. Apparently they entered obscurely in the wake of kindred groups, perhaps in the middle of the eleventh century; wandered from place to place for a period; and finally settled on the swampy islands of Lake Tezcuco, founding Tenochtitlan, or Mexico, which eventually became the capital of empire. The founding of the city is variously dated one group of references placing it at or near 1140, and another assigning dates from 1321 to 1327, variations which may refer to an earlier and later occupation by different or related tribal groups. The Aztec formed a league with their kindred neighbours, the Tecpanec of Tlacopan and the Acolhua of Tezcuco, in which their own role was a secondary one, until finally, under Axayacatl, Tizoc, and Ahuitzotl, the immediate predecessors of the last Montezuma (whose name is variously rendered Moteuhcoma, Moteczuma, Motecuma, Motecuhzoma, etc.), they rose to undisputed supremacy. This, however, was in war and politics, for Tezcuco, previous to the Conquest, was still the seat of Mexican learning.

Many of the Nahuatlan peoples retained mythic reminiscences of the period and course of their migrations; but of the narratives which remain hardly two are in accord, although most of them mention the "House of Seven Caves" (Chicomoztoc) as a place of dispersal. Back of this several of the narratives go, giving details of which the purely mythic character is evident, for the leaders named are gods and eponymous sires, while tribes of utterly unrelated stocks are given a common source. Thus, according to Mendieta's account, 14 at Chicomoztoc dwelt Iztacmixcoatl ("the White Cloud-Serpent") and his wife Ilancue ("the Old Woman"), from whom were sprung the ancestors " as from the sons of Noah " of the leading nations of Mexico, excepting that the Toltec were descended from Ixtacmixcoatl by a second wife, Chimalmatl (or Chimalma), who is named as mother of Quetzalcoatl, and who is represented elsewhere as the priestess or ancestress of the Aztec in their fabled first home, Aztlan.

Sahagun 15gives a version starting with the landing of the ancestral Mexicans at Panotlan ("Place of Arrival by Sea"), whence he says that they proceeded to Guatemala, and thence, guided by a priest, to Tamoanchan, where the Amoxoaque, or wise men, left them, departing toward the east with their ritual manuscripts and promising to return at the end of the world. Only four of the learned ones remained with the colonists Oxomoco, Cipactonal, Tlaltetecuin, and Xochicauaca and it was they who invented the calendar and its interpretation in order that men might have a guide for their conduct. From Tamoanchan the colonists went to Teotihuacan, where they made sacrifices and erected pyramids in honour of the Sun and of the Moon. Here also they elected their first kings, and here they buried them, regarding them as gods and saying of them, not that they had died, but that they had just awakened from a dream called life.

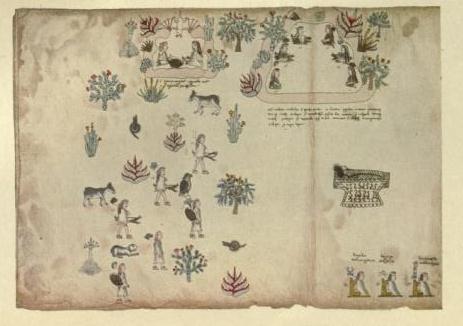

PLATE XVI: Section, comprising about one third, of the "Map Tlotzin," after Aubin, Memoir es sur la peinture didactique (Mission scientifique au Mexique et dans FAmerique Centrale), Plate I. The map is described by Boturini as a "map on prepared skin representing the genealogy of the Chichimec emperors from Tlotzin to the last king, Don Fernando Cortes Ixtilxochitzin." Two of the six "caves," or ancestral abodes of the Chichimec, shown on the whole map, are here represented. At the right, marked by a bat in the ceiling, is Tzinacanoztoc, "the Cave of the Bat"; below it, in Nahuatl, being the inscription, "Tzinacanoztoc, here was born Ixtilxochitzin." The second cave shown is Quauhyacac, "At the End of the Trees"; and here are shown a group of ancestral Chichimec chieftains, whose wanderings are indicated in the figures below. The Nahuatlan text below the figure of the cave is translated: "All came to establish themselves there at Quauhyacoc, where they were yet all together. Thence departed Amacui; with his wife he went to Colhuatlican. Thence again departed Nopal; he went with his wife to Huexotla. Thence again departed Tlotli; he went with his wife to Oztoticpac."

"Hence the ancients were in the habit of saying that when men die, they in reality began to live," addressing them: "Lord (or Lady), awake! the day is coming! Already the first light of dawn appears! The song of the yellow-plumed birds is heard, and the many-coloured butterflies are taking wing!" Even at Tamoanchan a dispersal of the tribes had begun: the Olmac and the Huastec had departed toward the east, and from them had come the invention of the intoxicating drink, pulque, and (apparently as a result of this) the power of creating magical illusions; for they could make a house seem to be in flames when nothing of the sort was taking place, they could show fish in empty waters, and they could even make it appear that they had cut their own bodies into morsels. But the peoples associated with the Mexicans departed from Teotihuacan. First went the Toltec, then the Otomi, who settled in Coatepec, and last the Nahua; they traversed the deserts, seeking a home, each tribe guided by its own gods. Worn by pains and famines, they at length came to the Place of Seven Caves, where they celebrated their respective rites. The Toltec were the first to go forth, finally settling at Tollan. The people of Michoacan departed next, to be followed by the Tepanec, Acolhua, Tlascaltec, and other Nahuatlan tribes, and last of all by the Aztec, or Mexicans proper, who, led by their god, came to Colhuacan. Even here they were not allowed to rest, but were compelled to resume their wanderings, and, passing from place to place "all designated by their names in the ancient paintings which form the annals of this people" finally they came again to Colhuacan, and thence to the neighbouring island where Tenochtitlan was founded.

Of the "ancient paintings," mentioned by Sahagun, several are preserved, 16 portraying the journey of the Aztec from Aztlan, their mythical fatherland, which is represented and described as located beyond the waters, or as surrounded by waters; and the first stage of the migration is said to have been made by boat. For this reason numerous speculations as to its locality have placed it overseas in Asia or on the North-west Coast of America although the more conservative opinion follows Seler, who holds that it represents simply an island shrine or temple-centre of the national god, and hence a focus of national organization rather than of tribal origin. According to the Codex Boturini (one of the migration picture-records), as interpreted by Seler and others, after leaving Aztlan, represented as an island upon which stood the shrine of Huitzilopochtli in care of the tribal ancestor and his wife Chimalma, the Aztec landed at Colhuacan (or Teocolhuacan, i. e. "the divine Colhuacan"), where they united with eight related tribes, the Uexotzinca, Chalca, Xochimilca, Cuitlauaca, Malinalca, Chichimeca, Tepaneca, and Matlatzinca, who are said to have had their origin in a cavern of a crook-peaked mountain. From Colhuacan, led by a priestess and four priests, they journeyed to a place (represented in the codex by a broken tree) which Seler identifies as Tamoanchan, or "the House of Descent," and which is also the "House of Birth," for it is here that souls are sent from the thirteenth heaven to be born.

Thence, after a sojourn of five years, the Aztec, perhaps urged on by some portent of which the broken tree is a symbol, took their departure alone, leaving their kindred tribes; and guided by Huitzilopochtli, they came to the land of melon-cacti and mesquite, where the god gave them bow and arrows and a snare. This land they called Mimixcoua ("Land of the Cloud-Serpent"); and it was here that they changed their name, for the first time calling themselves "Mexica" an appellation which Sahagun describes as formed from that of a chieftain, who was also an inspired priest, ruling over the nation while they were in the land of the Chichimec, and whose cradle, it was said, was a maguey plant, whence he was called Mexicatl ("Mescal Hare"). Per- haps this is the incident represented in the curious picture which shows human beings clad in skins and with ceremonial face-paintings, recumbent upon desert plants; and no doubt it signifies some important change in cult, such, perhaps, as the introduction of the mescal intoxication, with its attendant visions. It may, too, portray the institution of human sacri- fice; for the next station indicated on the chart, Cuextecat- lichocayan ("Where the Huastec Weep"), was the scene of the offering of the Huastec captives by arrow-slaying. From this place the journey led to Coatlicamac ("In the Jaws of the Serpent"), where the people "tied the years" and kindled the new fire; and from Coatlicamac they made their way to Tollan, with the reaching of which the first stage of the migration-story may be said to end. Seler regards the whole as a myth of the world-quarters: Tamoanchan is the West, as in the Books of Fate; Mimixcoua is the North; Cuextecatlichocayan is the East, as the reference to the Huastec shows; and Coatlicamac is the South; finally, Tollan is the Middle Place, being regarded, like other sacred cities, as the navel of the world.

A second stage of the myth depicts the journey of the Aztec from Tollan, through many stops, back to Colhuacan, until at last they came to the site of Tenochtitlan. It is said that as the tribes halted by the waters of Tezcuco they beheld a great eagle perched on a cactus growing from a wave-washed rock; and while they gazed the bird ascended to the rising sun with a serpent in his talons. This was regarded as a divine augury, and here Tenochtitlan was founded. Such is the tradition which gives modern Mexico its national emblem. The places of sojourn between Tollan and Tenochtitlan, as represented in the writings, are all with fair certainty identified with towns or sites in the Valley of Mexico, so that here we are in the realm of history rather than of myth. Historic also are the names (and approximate dates) of the nine lords or emperors who ruled from the Mexican capital before the coming of the Spaniards brought the native power to its unhappy end.

The fifth of the Aztec monarchs was the first Montezuma. Of him it is told (the story is recorded by Fray Diego Duran) 17 that after he had extended his realm and consolidated his rule, he decided to send an embassy to the home of his fathers, especially since he had heard that the mother of Huitzilopochtli was still living there. He summoned his counsellor Tlacaelel, who brought before him an aged man learned in the nation's history. "The place you name," said the old man, "is called Aztlan ['White'], and near it, in the midst of the water, is a mountain called Culhuacan ['Crooked Hill']. In its caverns our fathers dwelt for many years, much at their ease, and they were known as Mexitin and Azteca. They had quantities of duck, heron, cormorants, and other waterfowl, while birds of red and of yellow plumage diverted them with song. They had fine large fish ; handsome trees lined the shores ; and the streams flowed through meadows under the cypress and alder. In canoes they fared upon the waters, and they had floating gardens bearing maize, chile, tomatoes, beans, and all the vegetables which we now eat and which we have brought thence. But after they left this island and set foot on land, all this was changed: the herbs pricked them, the stones wounded, and the fields were full of thistle and of thorn. Snakes and venomous vermin swarmed everywhere, while all about were lions and tigers and other dangerous and hurtful beasts. So is it written in my books." Then the king dispatched his messengers with gifts for the mother of Huitzilopochtli. They came first to Coatepec, near Tollan, and there called upon their demons (for they were magicians) to guide them; and thus they reached Culhuacan, the mountain in the sea, where they beheld the fisherfolk and the floating gardens. The people of the land, finding that the foreigners spoke their tongue, asked what god they worshipped, and when told that it was Huitzilopochtli and that they were come with a present for Coatlicue, his mother, if she yet lived, they conducted the strangers to the steward of the god's mother. When they had delivered their message, stating their mission from the King and his counsellor, the steward answered: "Who is this Montezuma and who is Tlacaelel? Those who went from here bore no such names; they were called Tecacatetl, Acacitli, Oselopan, Ahatl, Xomimitl, Auexotl, Uicton, Tenoch, chieftains of the tribes, and with them were the four guardians of Huitzilopochtli." The messengers answered: "Sir, we own that we do not know these lords, nor have we seen them, for all are long dead." "Who, then, killed them? We who are left here are all yet living. Who, then, are they who live to-day?" The messengers told of the old man who retained the record of the journey, and they asked to be taken before the mother of the god to discharge their duty. The old man, who was the steward of Coatlicue, led them forward; but the mountain, as they ascended, was like a pile of loose sand, in which they sank. "What makes you so heavy?" asked the guide, who moved lightly on the surface; and they answered, "We eat meat and drink cocoa." "It is this meat and drink," said the elder, "that prevent you from reaching the place where your fathers dwelt; it is this that has brought death among you. We know naught of these, naught of the luxury that drags you down; with us all is simple and meagre." Thereupon he took them up, and swift as wind brought them into the presence of Coatlicue. The goddess was foul and frightful to behold, and like one near death, for she was in mourning for her son's departure; but when she heard the message and beheld the rich gifts, she sent word to her son, reminding him of the prophecy that he had made at the time of his going forth: how he should lead the seven tribes into the lands they were to possess, making war and reducing cities and nations to his service; and how at last he should be overthrown, even as he had overthrown others, and his weapons cast to earth. "Then, O mother mine, my time will be accomplished, and I will return fleeing to thy lap, but until then I shall know naught save pain. Therefore give me two pairs of sandals, one for going forth and one for returning, and four pairs of sandals, two pair for going forth and two for returning." "When he thinks on these words," continued the goddess, "and remembers that his mother yearns after him, bring to him this mantle of nequen and this breechband." With these gifts she dismissed the messengers; and as they descended, the steward of Coatlicue explained how the people of Aztlan kept their youth, for when they grew old, they climbed the mountain, and the climbing renewed their years. So the messengers returned, by the way they had come, to King Montezuma.

VI. SURVIVING PAGANISM

In 1502 Montezuma Xocoyotzin ("Montezuma the Young") was elected Emperor of Mexico, assuming a pomp and pride unknown to his predecessors. Five years later, in 1507, the Aztec "tied the years" and for the last time kindled the new fire on the breast of a noble captive. Ominous portents began to appear with the new cycle, and the chronicles abounded with imaginations of disaster. 18 The temple turret of the war-god was burned; another shrine was destroyed by fire from heaven, thunderlessly fallen in the midst of rain; a tree-headed comet was seen; Lake Tezcuco overflowed its banks for no cause; a rock which the King had ordered made into a sacrificial altar refused to be moved, saying to the workmen that the Lord of Creation would not suffer it; twins and monsters were born, and there were nightly cries, as of women in travail -

"Lamentings heard I' the air; strange screams of death,

And prophesying with accents terrible

Of dire combustion and confused events

New-hatched to the woeful time."

Fishermen caught a strange bird with a crystal in its head, and in the crystal, as in a mirror, Montezuma beheld unheard-of warriors, armed and slaying. Most terrible of all, a huge pyramid of fire appeared in the east, night after night, coruscating with points of brilliance. In his terror Montezuma summoned old Nezahualpilli of Tezcuco, noted as an astrologer, to interpret the sign; and this King, whose star was in the decline, took perhaps a grim satisfaction in reading from the portents the early overthrow of the empire. Montezuma, it is said, put the interpretation to test, challenging Nezahualpilli to the divinatory game of tlachtli; but just on the point of winning, the monarch lost and returned discomfited.

PLATE XVII: Interior of chamber, Mitla, showing type of mural decoration peculiar to this region. After photograph in the Peabody Museum.

Another tale, doubtless apocryphal, tells how Papantzin, sister of Montezuma, died and was buried; shortly afterward she was found sitting by a fountain in the palace garden, and when the lords were assembled in her presence, she told how a winged youth had taken her to the banks of a river, beside which she saw the bones of dead men and heard their groans, while upon the waters were strange craft, manned by fair and bearded warriors coming to possess the kingdom. Certain it is, at least, that the hearts of all men regarded the return of Quetzalcoatl as near the oppressed looking with hope, the powerful with dread, to the coming of the god and the vestments of the deity were among the first gifts with which the unhappy Mexican sought to win the favour of Cortez.

Nevertheless the memory of the King did not fade from native imagination with the fall of his throne. Stories of the greatness, the pride and the destruction of Montezuma spread; they became confused with older legends; and finally the Mexican monarch himself became the subject of myth. Far to the north the Papago 19 still show the cave of Montezuma, whom they have identified with Sihu, the elder brother of Coyote; and they tell how Montezuma, coming forth from a cave dug by the Creator, led the Indian nations thence. At first all went happily, and men and beasts conversed with one another until a flood ended this age of felicity, only Montezuma and his brother, Coyote, escaping in arks which they made for themselves. When the waters had subsided, they aided in the repeopling of the world, and to Montezuma was assigned the lordship of the new race, but, being swollen with pride and arrogance by his high dignity, he failed to rule justly. The Great Spirit, to punish him, removed the sun to a remote part of the heavens; whereupon Montezuma set about building a house which should reach the skies, and whose apartments he lined with jewels and precious metals. This the Great Spirit destroyed with his thunder; but Montezuma was still rebellious, whereupon as his supreme punishment, the Great Spirit sent an insect to summon the Spaniards from the East for his destruction.

How far the political influence of the Aztec Empire extended is not clearly certain, but there are numerous indications that its cultural relations were very wide. There are rites and myths of the Pueblo Indians, Hopi and Zufii, whose resemblance to the Mexican seems surely to imply a connexion not too remote; while far to the south, among the Nahua of Lake Nicaragua, the creator pair and ruling gods, Tamagostad and Qipattoval, are identical with the Mexican generative couple, Oxomoco and Cipactonal. 20

In outlying districts today the less-touched Nahuatlan tribes preserve their essential paganism, and Lumholtz's and Preuss's accounts 21 of the pantheons of the Cora and Huichol Indians give us a living image of what must have been the ancestral religion of the Nahuatlan tribes, at least in the crude days of their wanderings. Father Sun, say the Cora, is fierce in the summer-time, slaying men and animals; but Chuvalete, the Morning Star, keeps watch over him to prevent him from harming the people. Morning Star is cool and dislikes heat, and once he shot the Sun, causing him to fall to earth; but an old man restored him to the heavens, giving him a new start, Chuvalete is the first friend of the Cora among the gods, and it is to him that they address their prayers as they go to the spring to bathe in the early dawn; they call him, "Elder Brother," just as the Earth is "Our Mother" and the Sun "Our Father." The Water Serpent of the West, the Moon, the Winds, the Rain, the Lightning, all these are familiar deities. Preuss 22 calls attention to the striking emphasis which the Cora place on the power of thought: the leaders of the ceremonies are called "thinkers" and in their prayers and rites the conception of a magical preservative and creative power in thought frequently recurs, not only as a power of priests, who have obtained it through purification, but as the essential power of the gods. Thus, of the sun about to rise:

"Our Father in Heaven thinks upon his Earth, our

Father the Shining One.

There he is, on the other side of the World.

He thinks with his Thought, our Father, the Shining One.

He remembers, too, what he is, our Father, the Shining One."

And again it is the sacred words handed down in ritual through which men acquire that mystical participation in the divine power that preserves them in life :

" Here are present his Words, which he has given to

us, his children,

Wherewith we live and continue in the World.

Indeed, all his Words are here present, which he has uttered and

left unto us.

Here leaves he unto his children his Thought."