A Peep at the Pixies, or Legends of the West

By Anna Eliza Bray

The Seven Crosses of Tiverton; or, The Story of Pixy Picket

THE SEVEN CROSSES OF TIVERTON

THE events I am now about to relate occurred soon after that cruel king, the crook-backed Richard, was slain-in the battle of Bosworth Field; and the Earl of Richmond, who won the day, ascended the throne of England, as Henry, the seventh of that name.

During the wars which ended in his downfall, Richard, being so wicked a man himself, was joined by many men of high and low degree, who were also very wicked. Among these was Randolph Rowle, who, for the brutality of his disposition, was commonly called Randolph the Ruffian. He had served for many years under the late King Henry the Sixth, and (though it was never proved against him) was strongly suspected, on account of his hard-heartedness, of having been chosen as one of the murderers who assisted in smothering the poor little princes in the Tower.

Long before this he had married a young woman of his native town, Tiverton, in Devonshire, who was much too good for him. He used her very ill; and though he had seven children, none of them lived to be a year old. Strange things were said about the way in which it was supposed they came by their deaths. Their poor mother, whose name was Bridget, had a very tender heart, and grieved for the loss of her babes, as much as she rejoiced whenever her husband went away to the wars and left her at home; for then she had a little quiet, with nobody to beat and ill-use her. But as her husband took with him all the little she had gained in money by working hard to help her neighbours, and even deprived her of what wheat she had stored up. by gleaning in the fields, she was very poor and needy. The last time he went away was to fight in Bosworth Field; and then he left her with only seven eggs in the world to live upon; and these she had concealed in an old, cracked oaken bowl that stood in a dark place in the corner cupboard. To add to her troubles, her hen had left off laying eggs.

In the evening of the day of Randolph's departure, when the winds were blowing and the rain beating in heavy showers against her cottage window, Bridget sat over a wood-fire made by a few sticks which she had collected in the forest, thinking upon her hard fate, and what she should do to help herself. Suddenly she heard a moaning without, accompanied by a gentle tapping at her door. Bridget rose up in haste, for she fancied this must be the cry of some benighted traveller; and so kind was her heart that distress never cried to her in vain, for if she had but a crust of bread, she would gladly share it with any poor soul who had none. So she opened the door at once, when in came the queerest looking little creature she had ever seen, dressed almost in rags, dripping wet and shivering with cold.

It seemed to be a child, and a very small one, with a fat round face, a curly poll, a snub nose, and blue cunning eyes, but very sparkling and pretty. But the most strange thing of all was that there was a look of a woman in the child's face, which Bridget did not know very well how to describe when she told the story: so she used to say--"it was for all the world like a little old child, neither one thing nor the other, and yet for all that very pretty." As to the wet rags and the hair, she did not know what to think of them either, for though she wiped down the creature's locks with the tail of her own petticoat, as hard as a groom wipes down a horse after a heat, and got all the wet from its head, yet the tail of the petticoat remained bone dry, and looked cleaner and better than when it was new; and when she took the urchin to, the fire in her dripping clothes, they dried in a trice, but never once smoked!

This done she set the little one down on the low stool, with two legs and a half, in the chimney corner; and she sat as well, not once rocking, as if never a broken leg had been under her. Bridget now asked the little girl her name. She answered it was PICKET, and said that she had lost her way in the dark, and begged for something to eat, as she declared herself to be very hungry. Bridget rose up with a sigh to think how little she had to offer, but she took from the cracked bowl in the cupboard one of the seven eggs, and asked little Picket if she would like to have it boiled or roasted, telling her that six more eggs was all she had in the world.

"Six more eggs!" said the child, "then pray, ma'am, be so good as to give them to me; for I have in all six brothers and sisters at home, and all very hungry;" and, like 'Wordsworth's little girl, she added--" 'We are seven;' and we have neither father nor mother, and don't know what to do for a supper. So give the seven eggs to me, and I will begone, for the rain is over, and I can see through the window the moon above the clouds, and I shall now be able to find my way home, and my brothers and sisters and I will all sup together." So without waiting for ceremony, the forward little thing took the seven eggs, and tied them up in a bit of a rag that she wore like a cloak about her.

"You are welcome to the eggs, my dear," said the good-natured Bridget, "and as for your poor little brothers and sisters, I pity them very much. It makes me cry afresh to hear their number; for I have lost seven dear babes myself, and am now a childless woman." She wiped her eyes as she spoke, and told the little girl that if ever she could serve her, or her brothers and sisters, in any way, though she was very poor, she would never refuse to help the fatherless."

'The child seemed very sensible of her kindness; and asked her what would make her the most happy in the world.

"To have just such a pretty girl as you are, though not to look quite so much of a woman at your age."

'No sooner had she said this, than the strange little creature began to jump and leap about in a way that Bridget thought she would break all the eggs she had in her cloak; and then she laughed and began to sing; and going towards the door, whisked out of it, the good woman could scarcely tell how, singing very gaily these words as she departed:--

"Seven given in charity

Seven shall return to thee,

In a hopeful progeny."

Bridget stood dumb with surprise, and did not know what to make of all this. She crossed herself and blessed, herself, and went to bed in a very doubtful frame of mind. The next morning when she got up, she saw something. glitter in her old shoe, and found to her amazement it was a piece of silver coin, fresh and new as if just from the King's mint. Next the hen saluted her ears with the greatest cackling and ran about the yard, as if half mad with delight. Bridget found she had laid an egg, and so the fowl continued to do every day after for weeks together, till there were enough eggs for her to hatch chickens; and then she reared seven of the finest that ever were seen, But the greatest wonder is yet to be told.

A few months after all this had happened, as Randolph Rowle was one day returning home, his absence having been shorter than usual, he observed a great many people, young and old, about his house, all talking, moving, lifting up their hands and eyes, as if in amazement. The stir and bustle was considerable, for all the women in the village seemed assembled together.

"What's the matter?" inquired Randolph as he approached them, "Are you all gone mad to-day, or what has happened that you so beset my door?"

"O, Master Randolph Rowle, don't you know what has come to pass?" said a neighbour.

"How should I?" he replied. "I have been up to Lunnun with some of my old fellows at arms to try to get taken into the service of the new king, but he will not have us; and so here am I home again, and nothing better in fortune."

"Nothing better in fortune!" exclaimed one of the gossips. "O Master Randolph Rowle, you are the luckiest man in the world; there never was such a thing known or heard of before."

"You 'll be the envy of half the great barons and ladies in the county," said a young woman.

"You'll be talked of far and near," said an old one.

"For what?" exclaimed Randolph. "You have all tongues that run fast enough, but will not one of you tell me what all this is about?"

"And such a blessing upon your head," said an old grandmother who was present.

And I hope you will remember the poor neighbours who first told you of it," said another speaker; "and will give me something to drink your health with, for I am quite ready to do a neighbour's part."

"And I hope you'll give us all something to drink your health with, and to bring good luck on your roof, for as many more blessings every year," said another gossip. And so they went on chattering like magpies.

Randolph grew angry; his ears were stunned with twenty women all talking together, whilst he knew not what it was about. At last he grew rough, and lifting up a great walking staff that he held in his hand, vowed he would clear his door of them all if they would not tell him at once, and in plain terms, what had happened.

On hearing this, an old woman advanced, inclined her body a little, spread out her two hands open before her, looked up in his face, and said in a sort of scream, indicative of an excess of joyous congratulation--

"Why, Randolph Rowle, this it be then.--You be the happiest man in all the new king's kingdom; you be the father of seven children, all alive and well, and all born at the same time; and if you will give me something to buy spoons, I'll stand godmother to them all myself. Joy, joy to you, Randolph Rowle! Hurra, hurra!"

"And pray give something to wet the throats of us gossips, for bringing you the good news," and all the women, old and young, huddled round him, each claiming a reward for herself, for having been the first to announce it, and give him joy.

Randolph instinctively put his hands up to his ears, and neither seemed overjoyed, nor at all gladdened, as any honest father would have been at the hearing of such a piece of good luck, as having seven babies born to him all in one day. He rather looked vexed and angry about it; and protesting that not the cackling of the geese on the common, nor the squalling of all the cats in the village, nor the hum of the bee-hives, could so vex his ears and madden his senses as their tongues; he gave the old crone who had in the plainest manner told him the news a poke with his staff, kicked and pushed the others aside with heels and elbows, made his way within his own door, and banged it after him in all their faces.

Randolph found his wife sitting up, quite well, nicely dressed in the neatest clothes she had ever worn. The nicest cradle, covered with a white satin quilt, was by her side, and in it seven sweet pretty babies, just as if made out of wax; and as like the one to the other as so many pats of butter.

The sight of so numerous a family caused Randolph to be very angry; and without giving one kind word, or even. look, to his wife, he said, in a', rough voice and manner, "'What's all this? Seven little wretches to call me father, and to keep me day and night working for them, and starving myself. I shall do no such thing. They shall not stay here; I will not have them. And what's all this? You so fine as my lady the Countess of Devon, up at the Castle; and white satin, too, thrown over this bundle of kittens. How comes all this?, I don't understand it."

"I am sure, I can't tell you, husband," said Bridget, "all, I know is, that neither the clothes, nor the cradle, nor the white satin quilt cost us the smallest bit of money; for I found them all by the bed-side when I opened my eyes; on waking from the first sleep that I got after the dear babes were born. And O husband, for the love of all the saints, don't call these seven sweet, pretty, dear, beautiful little babes, kittens. They are human creatures, and all girls. And when they are made Christians, I hope they will live to be good ones, and a comfort to you. So do give them a father's blessing, and be thankful for having seven of them sent all at one time to make up for the number we lost formerly."

"I bless them!" said Randolph," for what? For bringing me seven plagues--seven mouths to fill instead of one. I can't feed babes as thrushes do their young, with worms; and my wish, wife, is, that these seven little wretches were food for them in the church-yard."

"O Randolph, don't say such a wicked thing, for fear the roof should fall down upon us and crush us both with them. To think such an unnatural wish should come from the lips of a father, it is shocking! But I'll work for the babes day and night to maintain them. And I'll do all for them myself till they are old enough to get their own living. So do now be a good man for once, and bless your own dear children."

Randolph looked down upon the poor innocents sleeping in the cradle, but with no relenting expression., He spoke not a word.

"Don't they look just like so many daisies, sweet, pretty dears," said Bridget, her admiration of her little progeny inspiring her with the first and only poetical mode of speech she ever ventured to use in the presence of her husband. He answered her by calling her a fool for her pains; and, without stopping to say another word, left the cottage and went in search of old Pancras Cole, the woman of the evil eye, as she was called, who lived in a lonely hut by the road-side near the neighbouring forest. It was said that, when she had nothing else to do, she would amuse herself by taking a seat on a rock by the way-side, and there would work some spell to the injury of every traveller mounted on horse-back who refused to give her money; that she would make his horse stumble or throw the rider before he got to his journey's end. Randolph the ruffian had, on more occasions than the present, been seen to seek her when his humour or his passions, like her own, were disposed to work evil.

Pancras Cole was seated on the rock as he approached her. She was dressed in an old, dark gown and cloak, with a hood thrown over her head, leaving the face and forehead uncovered. She had the most formidable aspect. Though seated, she appeared to be a very tall woman, strong and robust, with the muscles of her arms so marked, that they looked almost like whip-cords drawn round them. They were quite bare nearly up to her shoulders, for her cloak was thrown back. Her face was dark, her eyes fiery and dark also, and she had a black beard on the upper lip and about the chin; it would have been a great improvement to her, had she sent for the village barber to shave it. She was leaning on her staff, and seemed to be looking out for a corner, when Randolph approached. Before he could speak, she thus greeted him.

"Dogs have whelps more than are needed;

Kittens have their deaths unheeded.

Why should seven make thee moan?

Babes they are, and all thine own.

Seven! in a basket heap them,

Seven! let the river keep them.

"Good," said Randolph the ruffian, "Mother, you and I never differ in our way of thinking."

"Nor of acting," exclaimed Paneras Cole, "but what you would' do, must be done before the moon wanes tomorrow night. And more than that, Randolph Rowle," she added, "follow my counsel, and bread and ale and a stout sword and good pay shall be yours."

"What must I do? I would go below the earth and take service with that dark gentleman you serve so well upon it, mother, for such guerdon as you tell me of," said the reprobate Randolph, with a grin which was the nearest approach to a smile his countenance ever assumed. "Tell me what to do, and where to go, and I am not the man to flinch in the matter."

Go and take service with the Baron La Zouch, who was King Richard's friend," said the hag. "He has been fined heavily, and his castle seized, for serving the dead king; but the living one has granted him pardon for his life, and he is about to thank King Henry for it as I would have him. He is secretly drawing together a band of discontented men, and stirring up some of the great barons against him. I have given him my blessing. If this treason thrives, you will be a made man, Randolph Rowle. Go before the moon wanes to-morrow night, and, by the power of my art, I foresee you will be taken Into his service."

"And the seven imps at home?" said the profane Randolph.

Do this," replied old Pancras Cole; and she rose up and whispered something in Randolph's ear, then raised her arm, and pointed with her "skinny finger" in an opposite direction; and, bidding the evil one prosper him in all his ways, left him to himself, went into the cottage, and shut the door after her.

Now, my young friends, you want to know what she said to him. But how can I tell you? No one was there to hear it; and as neither Pancras Cole nor Randolph Rowle ever made known the subject of that whisper to any living creature, it is quite impossible that I can be acquainted with it. But, perhaps, the next event in my tale may enable us to guess what it was.

***

In the days of which I write, there were neither stagecoaches, flies, gigs, nor rail-roads. Gentlemen and ladies generally travelled on horse-back; and that through such bad roads (for this was long before Mr. M'Adam was born), they seldom made a journey of any distance, unless compelled so to do. They generally contented themselves, if they lived in the country, with riding about hunting and hawking on their own lands. There were, also, no newspapers in those days; so that, what with the want of such coaches and rail-roads, and newspapers, news of any kind travelled slowly; and an event which was very stirring in one village might not be known in the next for some days, or even weeks, after. This I tell you, my young friends, in order to account for Randolph Rowle's good luck, in having seven little girls all at once, not being so speedily or so much known in the neighbourhood as the gossips round his door, who wanted to get some money from him, had predicted.

At the time of my story, there was a certain Countess of Devon, a widow, whose son was a little boy, and under the care of a good master at Winchester School. The Countess took charge of all his castles and lands till he should be of age to take possession of them himself; and she lived always in one or the other of these strongholds. Now there was, among them, a very noble residence, which had been built early in the twelfth century. It stood on the north side of the market-town of Tiverton; and to this day, though but a portion of its ruins are in existence, it forms an object of curiosity with the traveller and the antiquary. The ruins consist of a large gateway and some strong towers and walls, partially overgrown with ivy.

Just before the opening of my tale, the Countess had been much annoyed by a law-suit, commenced against herself and her little son by the wicked Baron La Zouch, who set up a most unjust claim to Tiverton Castle, pretending he had a right to the lands on which it stood. But, after a great deal of time and money spent to no purpose, he lost his suit, and the Countess remained in full possession of the castle.

In the times of which I write, the town and neighbourhood of Tiverton were different in many respects to what they now are. A large park and forest belonging to the Earls of Devon formed part of the castle domain, and the river ran through woods that have long since been destroyed, so that it would now be in vain to seek for the spot where the good and pious Countess of Devon erected a little chapel or oratory, to which she was fond of retiring to pray and meditate, without being disturbed by any of her numerous household or guests. The chapel was some distance from the castle, but she took a pleasure in walking to it alone early of a morning.

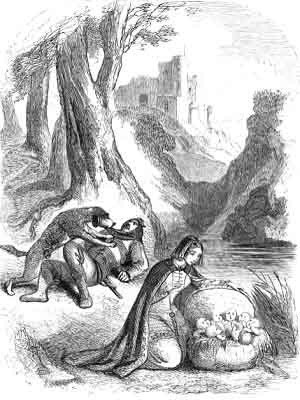

In one of these walks, she came suddenly upon a man who was just about turning into a narrow path, which led through the wood to the river. She observed he was carrying a basket, and that when he saw her, he first made as if he would pass her at once; then he stood back, then he moved forward again, and though he put down his load for a minute to doff his cap to her, for he knew who she was, yet he snatched the basket up again in a very hasty manner, and seemed so desirous to get on, that he had hardly the patience to let her pass.

"Good man," said the Countess, who thought there was something very strange in all this, "what makes you in such a hurry, and what have you there in that basket?"

Whelps, my lady, whelps."

"Whelps!" said the Countess. "Do let me see them."

They are not worth looking at, my lady," replied the man; "they are only puppies not worth the rearing."

"And what are you going to do with them?" inquired the Countess.

"Drown them, my lady; toss them into the river; such whelps are not worth the rearing."

"I will see them," said the Countess. "Put the basket down."

"They are my own, and I have a right to do what I please with them," muttered the man. "If I open the basket, they'll jump out and run away, and I've no time to spare to catch them: so good-morrow to you, my lady." And with that he attempted to push past her in a very rude manner.

But this purpose was not so easily effected. The Countess, though alone, was not unattended; she had by her side a guard who understood and obeyed the slightest sign she gave him of her pleasure.

"Seize him, Harold, seize him!" accompanied by a motion of her hand, caused a noble bloodhound in a moment to fly at the fellow, and seize him by the throat. In the struggle his foot slipped, and he fell with some violence on the ground, striking the back of his head against the roots of an oak-tree that crossed the path. The fellow was somewhat stunned by the blow. The Countess, whose command over her dog was no less surprising than his intelligence in obeying her, now made some sign, and the bound held the man by the throat, but without throttling him.

In another moment she removed the lid from the basket; when who shall speak her surprise, on beholding what then met her eyes! Seven sweet beautiful little babies, all put together with their heads uppermost, like birds in a nest, and some opening their mouths, as if asking for food, like those birds, from their dams.

"O you cruel, wicked man!" said the Countess. "But you shall not escape punishment; my people shall teach you to know that murder can neither be intended nor committed on my domain without chastisement."

At that moment, all the seven babies began to cry, and the Countess became sorely embarrassed what to do, between her desire to save the children, and to detain the man who would have destroyed them. But the lives of the former were, she justly judged, of the first consequence; and no time was to be lost, for they seemed very hungry, and much in want of bread-pap. She, therefore, at once put the lid on the basket, but found she could not carry it without assistance. Calling off Harold from the man, she bade the dog take one handle in his mouth, whilst she held the other, and in this way proposed to carry it between them to the castle. But the noble hound, who seemed on that morning to possess even more than his accustomed intelligence, relieved her by taking at once the basket in his mouth, and without any help whatever, wagged his tail, and trotted off with it towards the castle.

The Countess feared to remain without her guard, near such a ruffian; and observing that time fellow was now raising himself up from the ground, she said to him, "Repent; and be thankful that you have been prevented doing a most cruel deed," and followed the dog as fast as her steps could carry her.

The Countess of Devon truly did a good deed, in saving the lives of Randolph Rowle's seven poor little babes from the wicked purpose of their unnatural father. No one knew what became of him; but, after many enquiries, she found out the mother, and was very kind to her; but, so much had Bridget fretted for the loss of her babes, and so ill had she been used by her husband, that her health failed her very much. Seeing this, and thinking it not safe that the poor woman should remain where so cruel a husband might be likely to return some day or other to molest her, the Countess persuaded Bridget to go to a distance, and recommended her to the abbess of a convent in Cornwall, where she might make herself useful in household work to help the nuns.

Bridget agreed to the proposal; and, before she left the castle, took leave of her seven sweet babies very affectionately; and the Countess made the poor woman quite happy, by assuring her that she would do all for the dear little creatures just the same as if they were children of her own. She kept her word; had them christened, and gave them an education fit for the first ladies in the land.

***

PART II.

FIFTEEN years had passed away since the events related in the last chapter. The Countess' son had grown up a man, had gone to travel for the improvement of his mind and manners, and left his good lady-mother in the full command of his castle of Tiverton, where she liked principally to dwell.

The Countess now began to consider that it was high time for her seven daughters,. as she used to call Patience, Katherine, Margaret, Mabel, Alice, Isabel, and Ursula, to see something of the world, and be introduced into company, so that they might appear at the grand dinners and balls she often gave at the castle. The Countess always kept her son's birth-day, and made a great feast upon it to her friends, her followers, and tenants; and the poor were not forgotten on so joyous an occasion. True, he was now absent; but she loved him so dearly, that she determined to have the feast just as usual; and as it so happened that, fifteen years before, she preserved the seven children on her son's birth-day, she determined to make it a festival of more than usual splendour. So grand was everything to be, with such plenty of good cheer, that it took a whole month to prepare for the day. When it came at last, on the 15th of July, though it was St. Swithin's day, not a drop of rain fell; and the sun shone out so bright, and with such a full face, as if he could never tire with looking upon the revelry, and giving a warm welcome to the guests.

Everything was ready; the Countess sat at the head of a long table in the old castle hall. Knights, ladies, esquires, and pages, were all present in their gayest attire; whilst her seven fair daughters, the children of adoption, sat by her, four on the right, and three on the left hand. They were all dressed in white satin, and could only be known, the one from the other, by the variety in colour of the knots of ribband which they wore upon their bosoms. So much, indeed, were they alike, that the Countess herself found it difficult to distinguish them. They had all light brown curly hair, fine blue eyes, and necks and cheeks like lilies and roses. Beautiful as they were, they were quite as good as they were beautiful; and so grateful, that the only contest they ever had among themselves was, which should do most to oblige and serve the good lady who had been to them all such a good friend and benefactress.

It was really a very pretty sight, to see both them and the dinner; how plentiful it was; how gaily the tables were set out with festoons of flowers; how the cups of wine and mead went sparkling round the board. It was cheering to hear with what a shouting the healths of the Countess of Devon, her absent son, and her seven fair daughters, were given in the hall, as the old harper struck up his harp and sang to it a song which made the old roof echo again with its joyous sounds.

Just as the harper was concluding his song, the horn, which hung at the castle gates to announce the arrival of any one who desired admission, sounded loud and long. The Countess was surprised, as all the guests of any consequence she had invited were already arrived, and seated at the table, and for no common person would the horn blow after that fashion. A page ran in haste up to his mistress, and begged her to go to the window, which looked towards the long avenue that led to the castle, and she would see a sight that would surprise her. The Countess and her seven young ladies, none of whom were wanting in curiosity, did as they were advised to do, and ran to the window, and there saw what I really do not know how to describe, so glorious was it.

There appeared, coming along the Avenue, a sort of small open car, so white and dazzling that it looked as if made of ivory and silver. It was drawn by four cream-coloured ponies, but not larger than ordinary sized dogs.

The harness they had about them was composed of gold and mother-of-pearl; and on their heads, and at their ears, the little animals had bunches of flowers tied up with blue, pink, and green ribbands. Multitudes of little men on foot, each wearing such shining dresses, that it is not possible I can particularize them, were seen around the car, and each carried a javelin in one hand, and a little shield slung across his shoulders. It was quite evident, therefore, these miniature men acted as soldiers.

In front of this guard of honour, walked the musicians; they were very queer and whimsical in their appearance, dresses, and instruments. They were all like little men; but some among them looked old and ugly; and each man who played the fiddle had carved on the top of his instrument a face resembling his own, in all its ugliness. There were Jew's harps, and flutes that seemed to be formed out of old broom sticks; which was the more extraordinary where everything was so fine. Several pot-lids were used by way of cymbals; and the leader of the band, a very pompous little fellow, wearing what was in his day a novelty, a full-bottomed wig, carried a salt-box under his arm, and played upon it with great taste and expression; a set of performers on the marrow-bones and cleaver, probably the finest in Europe, completed the band.

In the car was seated a lady, so very splendidly dressed that to look at her when the beams of the sun fell upon her, as they did on her coming into the court of the castle, was as trying to the eyes, as it is to look upon water, when it reflects the sun's rays. On a nearer view, it was seen that although she was loaded with jewels, she wore nothing by way of ornament but what in form resembled some object in nature. Her tiara was made by a row of golden-crested wrens; their eyes were of diamonds, and the finest chased gold formed the crown of the birds; whilst round the neck of each was a little collar of the richest gems. Her gown was of the thinest silver tissue; and over it a robe lined with the white and glossy plumage from the breast of the swan.

At the back of her car sat seven ladies, her maids of honour, each carried something in her hand over which was thrown a white napkin; probably to conceal it from the common gaze. There were at least one hundred knights and as many squires, all in the gayest attire, with bright armour, and the richest velvets and jewels, and helmets and bonnets, with diamond and emerald ornaments; and white plumes drooping over their heads. The Countess was lost in wonder; but nothing in this splendid sight so much surprised her as to see how very small were all the gentlemen, the ladies, the car, and the horses. In point of size they really looked just like a set of little children playing at kings and queens, surrounded by their court.

But there they were; and the only probable conjecture the Countess could make was--that they must be people from one of those strange and little known countries, over seas, in the eastern part of the world, which neither in size nor in any thing else resembled the nations of Europe. She had often heard poor pilgrims, who go about from castle to castle telling the wonders they have seen in their travels, speak of such beings. Her son, too, was on his travels; perhaps he had visited the court of some Prince of this description, and might have recommended him with several of his chief nobility, or probably, his Queen, to make a journey to England, and to visit his mother at Tiverton Castle. The Countess told what she thought to those around her; and they all fancied she must be right in her opinion. It was agreed to give the stranger a very handsome and ceremonious reception.

The grand little lady gave her hand to the chamberlain of the castle, who bent down to accommodate his height to hers, as he handed her from her car. All the pages and gentlemen present followed his example in paying their respects to the maids of honour; and many of the household also shewed the most civil attention to the mounted knights and their diminutive horses. At length the whole of the new corners entered the hall. The grand lady directed the master of the salt-box to stop the band, as she was about to make a speech, and to salute the Countess of Devon.

The Countess, surrounded by her seven daughters, received the little lady standing on the dais. She bade the fair stranger, who came about as high as her knee, welcome; and ventured to ask her name and her country.

"The Princess Picket," she replied, with great dignity; but with a very sweet smile, as if to reassure the Countess, lest the announcement of the very high rank of her guest should be too much for her. The princess was then conducted to the foot-stool that stood before the chair of state, which was too high for her to reach, and seated upon the stool: the maids of honour stood around her, in respectful observance of her pleasure.

The Countess, after many civilities, requested the Princess and her party to take refreshment, which she did not refuse. A nice little table was brought in, and many dainties placed upon it. The Princess Pickett and her ladies pulled and picked a few pieces with their fingers; but seemed to like nothing so well as a junket that was produced; and on that they fell to with all their might, lapped the cream like young kittens, and soon emptied the dish and called for another.

The little gentlemen of the Princess' suite were regaled at the long board in the hall; and as the readiest way of serving them, for they were not tall enough to touch it, they were set upon the table. They fell to very heartily on the good cheer, and did not spare the wines. Some, indeed, so far forgot themselves, as to take rather too much; and more than one had a tumble on the floor, which only excited peals of laughter among his fellows. But the Princess, who was very dignified, would not sanction anything like riot in her attendants; and saying she had far to travel that night, and must be gone, directed her people to prepare for her departure.

She then rose and very politely complimented the Countess on her hospitality, and on the grace and beauty of her seven fair daughters. The Countess said plainly, they were none of hers, and was much astonished to find that the Princess knew perfectly well their history, more especially when she added, she was aware the lady of the castle on that day celebrated the anniversary of her son's birth; the same being also the day of her having, fifteen years before, done so good a deed as the saving of the poor babes might truly be called. Before her departure, she wished to give to each young lady some token of her regard; and a word of good advice. She waved her hand to them gracefully; and the girls instantly threw themselves at her feet and declared their readiness to obey her commands.

Princess Pickett was satisfied. She bade them arise; and speaking apart to her maids of honour, they also prepared to fulfil her orders. The first took her station on the right-hand of her mistress, as she beckoned to one of the sisters to approach her.

Patience stepped forward. The Princess then took from the hands of her attendant a beautiful little dog with long curly ears, and presenting it to Patience, said--

"Fidele take--his watchful ear

Will ne'er be closed when danger's near."

She next ordered Katharine to come to her; and taking something from another of her ladies in waiting, presented to this sister a small beautifully-carved ivory hand, the fingers of which were rather bent towards the thumb. The Princess spoke--

"Doubt not your way by day or night;

This ivory hand will guide you right."

With exactly the same ceremonies, to each of the five remaining sisters she presented a gift. To Margaret, a phial, with these words--

"Take, then, this wine; it hath a power

To bind in sleep for one whole hour."

To Mabel she gave a beautiful little bird of the dove class, but scarcely larger than a wren. It was in a pretty cage with golden wires. Mabel could not help expressing her admiration of the gift in a few words of thankful delight. The Princess, as she put the cage with its feathered tenant into her hand, said--

"Safely and swiftly through the air

This faithful bird will letter bear."

Alice came next at her desire. The Princess gave her a very plain key, suspended on a ring of gold, with these words:--

"Through every door this little key

Will give escape or entrance free."

To Isabel she presented what was apparently a very simple gift, a little parcel of dried herbs that looked no better than a bundle of common dead leaves, tied up together. The Princess smiled as if amused at seeing how much Isabel was disappointed at receiving so poor a gift; but she said as she smiled:--

"The deadliest wound of sharpest steel,

Sword, spear, or shaft, this herb will heal"

Ursula next advanced blushing, and in such a tremor she could hardly stand in so august a presence. The Princess graciously reassured her, and with much condescension gave her a small but elegantly formed lute with these words:--

"A lute can charm the bosom rude,

When passion's in its fiercest mood."

This was the last gift. As if inspired by some powerful spell which encompassed them, and was quite irresistible, the seven sisters fell at the Countess of Devon's feet, and vowed in the name of all the saints to whom they prayed, to dedicate to her at any time in which she might need their services, the gifts they had received.

The Princess Picket was well pleased with their modest and dutiful behaviour, and took her leave both of them and all present with her accustomed dignity. She mounted into her car, and commanded her band to give a parting token of respect to the Countess, by playing one of their most impressive airs. The Jews' harp, the marrow-bones and cleavers, and the other instruments, led by the salt-box. struck up "Polly put the kettle on," which tune probably not even Sir Henry Bishop himself, with all his profound knowledge of music, is aware to be of such ancient date, as to have been performed in such a presence, and by such a distinguished set of musicians as those described in this veritable history.

It was soon after this eventful day, that the good Countess of Devon began to experience anew the wicked designs of her old enemy, the Baron La Zouch. Deserted by the lawyers, who, in the first instance had urged him on to commence the law-suit, in the hope of gaining the lands, he determined to have no more to do with such deceivers. He said they took his money and left him and his cause just as it was before he had anything to do with them. Now the Baron La Zouch was a bold man and very fond of fighting, and so he called his archers and all his merry men about him, and told them that if they would follow him and storm the castle of Tiverton, that was his by right, and if they beat the Countess of Devon's men at arms, who were in it as her guards, he would allow them as soon as they got possession to share the gold and silver cups and spoons among them, and to open the cellars and help themselves to all the wines and strong ale they could find in them. The Baron's men were very well pleased with the proposal, for like their master, they were no better than thieves: and so they set forward to the storming of Tiverton castle.

I will not detain you, my young friends, with a relation of all the particulars of the siege. It was a very stirring one whilst it lasted. So many men were collected in the surrounding woods, that there was scarcely a branch of a tree, but a nodding plume, or a helmet, or the glitter of a steel cap was seen under it. There was a fierce contest in the effort made by the besiegers to storm the outward barriers and to gain access to the castle by crossing the moat or ditch by which it was surrounded. When that was gained by the enemy, there was such a blowing of bugles and sounding of trumpets, and whizzing of arrows, and twanging of crossbows; such a rolling down of stones and hot pitch from the battlements of the castle on the besiegers, and such a shouting and a calling and a banging with swords and axes about each other's heads; and such a clashing of shields, that never was anything like it since men began to kill each other for gain, or for amusement, in battles or in tournaments. But at last the besiegers were beaten back: many lost their lives; so that the Baron La Zouch was obliged to give over the contest and draw off his men, leaving the Countess of Devon, who had sustained very little loss, in full possession of her castle, her gold and silver cups and spoons, and all her wine and ale.

Thus defeated in law and in arms, the Baron La Zouch was nevertheless determined not to give over annoying the Countess; and thinking that as her son was absent over seas, if he could but get rid of such a spirited woman, he should soon possess himself of the castle, he determined to have recourse to treachery. So wicked was he, that he offered among the worst of his own people a reward in gold to any one of them who would kill the Countess, either openly or by any secret means he could devise.

La Zouch was a violent man, but even in his own wicked plans incautious; so that the plots he was desirous to carry into execution against her life reached the ears of the Countess. All her seven daughters became very watchful and anxious about her; indeed, so did her household and people generally, for she was a very good mistress over them all. Every precaution was taken for safety; the drawbridge that crossed the moat was raised every evening before dark, and no one suffered to pass over or to enter into the castle without the warder knowing who he was.

One night when the weather was very warm, the Countess, before retiring to bed, opened a window in the room where she slept, which was much larger than castle-windows of the time usually were, but she was very fond of plenty of fresh air, and so she had it altered to suit her own fancy. She enquired of her attendant, if a page who slept in a room adjoining her little oratory was at his post, as, ever since these alarms about the Baron, he was so stationed as her guard for the night. On being informed he was at hand in case of need, she dismissed her waiting damsel, and retired to rest.

About midnight, the Countess was awakened by a strange sound without the window. The moon shone brightly, for it was at the full, and streamed into the apartment in a flood of light, when she fancied she saw a small creature like a child in form, but not so high as her hand, pulling the ears of the little dog which the Princess Picket had given to Patience, and which, by that affectionate girl's wish, the Countess had taken to sleep in her bed-chamber ever since she had been frightened about the Baron. She now looked and wondered, and fancied that she must be dreaming. The dog growled on having his ears pulled, but did not raise up his nose, which was turned towards his hind legs, as he lay in a manner rolled up on the rushes near the bed-side. But before the lady could satisfy herself if she were waking or sleeping, she heard a noise at the window, and, on looking up, saw, to her astonishment, a man squeezing himself through it, and getting into her room. The moon gleamed partially upon him, and showed that he wore a steel casque or cap: something glittered that he carried in his hand.

At that moment, before the Countess could spring from her bed, the dog roused up, and barked so furiously, that the man, who had cleared the window and leaped down on the floor, first made at the dog with the intent to silence it. But though he struck at it again and again, the little creature ran round and round and round him in so quick a manner, that he could neither strike it, nor kill it, nor get away from it, for the nimble animal flew at one leg, now at another, hindering every attempt he made to put forward a foot to reach the Countess. He was amazed, for never before did so insignificant a little dog become a match for a ruffian bent on murder.

In the interval, the Countess leaped from her bed, and rushing towards that side of the room where her zealous little guard still fought so bravely for her defence, she slipped under the arras or tapestry that hung loose over the walls, opened a secret door which it concealed, and in another moment called up the page. She told him he was too young and too slight to encounter the armed man, but bade him run and sound the alarm-bell that was near her chamber, and do all he could to rouse the castle, and call up the guard, who, night and day, were on the watch at the castle gates.

She was obeyed; and the ruffian, at the very instant the dog was beginning to weary of his contest with him, was taken prisoner. The Countess spared his life, though he deserved to lose it; but she caused him to be chained and put into a dungeon of the castle. There the priest obtained from him a confession: he was one of the Baron La Zouch's people. On the previous evening he had contrived to deceive the porter, and to pass unsuspected, when several of the countrymen were bringing great loads of wood for fires into the castle. The villain had concealed himself in some bushes that grew under one of the outer walls; and knowing all about the castle, and where the Countess slept, with the assistance of a scaling-ladder he had got in at her bedroom window, when all her household was at rest. He acknowledged that the little dog had been the means of saving her life.

In consequence of this, all the bushes which had any where grown under the walls were cut down; and the people of the castle became more than ever watchful. At length the Countess was much relieved by hearing that the Baron la Zouch was absent from the country, and had taken with him all his men, except a few that he left to guard his own castle which was far distant from hers. She now thought herself safe for a time; and as she had been very much confined within her own walls, she began to wish for fresh air. A ride in the forest was proposed. After consulting with the priest and the captain of the guard, they gave it as their opinion that the safest way would be for the Countess and one of her daughters to dress themselves very plainly, like their waiting damsels; and so to go out together without any attendance, as if they were merely two of the household going on their own affairs to the neighbouring market; whereas did so great a lady go forth with her accustomed state it might attract notice, and some new plan be devised for her injury.

According to this advice, the Countess and Katherine, each mounted on a pretty and swift pacing pony, wrapped around her a plain grey cloak with a hood, and having as plain a foot cloth, set out for an airing. They soon reached the forest. When the Countess came to the spot at the entrance of the wood, where so many years before she met Randolph with his basket of live children, she told Katherine that was the place where herself and her sisters had been saved from a cruel fate. The young lady shed tears at the affecting narrative, and after pausing a few moments to express her sense of thankfulness, and her determination to serve her benefactress at the risk of life itself, they continued for some time their ride under the boughs of the trees. Now and then a deer bounded across their path, in his way to join the herd to which he belonged, or to go down to the river's side and slake his thirst from the stream that ran as clear as a mirror, reflecting in its dark surface the woods and the sky, so that it looked almost like a Pixy world seen beneath the waters. The birds were singing merrily, and hopping about the grass, or flying from bough to bough, as joyous as birds could be.

At length, on advancing more towards the depths of the forest, Katherine, who had very quick eyes and observed every thing, suddenly drew up her pony by the side of the Countess, and said to her in a hurried manner, "Dear lady, what shall we do? It is neither safe to continue on this road, nor to turn back, for I have looked well about me before I would speak to you, because I would speak with certainty. Steel caps and shining armour and arms glanced every now and then through the boughs of the trees as we passed, to the right of us. And from something that I see glittering at this moment yonder, under the trees in the direction we are going, I am certain there are men concealed in that quarter also. What shall we do?"

"I know not," said the Countess, giving herself up for lost, "I know not; we shall surely be taken or killed by some of the followers of that wicked Baron is. Zouch. Where can we turn for safety?"

Katherine looked for a few minutes greatly distressed; but all at once, as if a sudden thought struck her, she stopped; her countenance brightened up; and still holding the rein in her left hand, she passed the other under her cloak, and exclaiming, "I remember now, we are safe," immediately drew forth the little ivory hand that had been presented to her by the Princess Pickett. With perfect calmness she held it up, and shewed it to the Countess.

Instantly on doing so, the fore-finger of the delicately carved little hand moved, and pointed to an obscure path (scarcely, visible to a casual observer) that led under some large overhanging oaks, to an unfrequented part of the forest. The Countess, who at once saw and understood the sign, bowed her head in token of assent to it; and turning her pony in the direction to which the hand pointed, the creature set off with a speed that was astonishing; and yet so easy was the motion, that the Countess seemed to ride on the winds rather than on the earth. Katherine followed in like manner. So little known was this path, that the ladies who had ridden in that forest for many years had never before seen it.

They came at length to a very pretty spot; and there the ponies stopped of their own accord. The woods still continued thick above their heads with crossing boughs; some broken rocks lay immediately before them, over which dashed with a pleasing sound a cool and sparkling fall of water, not lofty but very beautiful. A small hermitage stood near the rocks, low-built, of wood, and covered with a thatch composed of green boughs. On a moss-grown stone, near the entrance, sat an aged man in a grey gown. His beard hung down upon his breast; his years, his dress; his beard altogether looked venerable. Yet on a near approach, there was something in his countenance which seemed to speak a man whose character had not always been that of an humble and meek recluse. There were strong lines about the brows, which were naturally knit, and presented no very pleasing expression; whilst the mouth retained the traces of passions once strong, and even now not wholly subdued. Still he was old, and the Countess felt, as all good people do, the highest respect for age; and as the hermit rose to receive her and help her off the pony she begged his blessing.

The Countess told him her story frankly, not fearing to trust so holy a man with the knowledge of the truth. He heard her with attention, invited both the ladies into his cell, and offered them his brown loaf and a cup of water from the spring, such being all the refreshment he had to lay before them. He then counselled them how to proceed; advised to wait in his cell till such time as the moon should be risen, when he would conduct them back to the castle by a path through the wood, known to so few that he considered there could be no danger in following it. As soon as they reached the outskirts, he would go forward and give notice to the castle of the approach of its lady; and a guard of, her own people might then come forth and

conduct her in safety through the more known and frequented part of the way. The Countess would have instantly consented, but Katherine gave her a look, which she at once understood. The young lady then, without saying a word to the hermit, consulted again the ivory hand, and, finding it pointed to where he proposed to go, she felt satisfied. All was soon arranged; and it was agreed to adopt the plan without fear, as soon as the moon should be risen. It succeeded as well as it could be wished; and so the Countess was saved that night from danger.

But it soon appeared that the malice of her cruel enemy was not less than his covetousness; and that he was determined never to let the poor lady rest till he had gained possession of her castle. His leaving the neighbourhood was only a pretence, to put her off her guard; and it succeeded but too well. Her cousin, Sir William Courtenay, a very brave knight, who had helped to defend her most valiantly during the siege, in consequence of believing that La Zouch was now far off, had retired, with his followers, to a castle of his own near Tregony, in Cornwall.

No sooner was this known, than the Baron La Zouch, with three times as many men as he before brought against it, marched suddenly upon Tiverton, surprised the guard of the outer works, and, before the draw-bridge could be raised, he and his soldiers passed over; and though the men-at-arms did their best to defend the castle, after a very short contest, it was compelled to yield, and the Countess and her seven fair daughters, and all who were in it, were completely at his mercy.

Immediately on becoming master of the place, the Baron busied himself with securing his prize; and that night was content to set men to watch; so that neither the Countess, nor any one of the seven, could go forth from their chamber. He sent a message, that he would see her some time on the following day.

To describe the state of her distress would be impossible. She wrung her hands, she tore her hair, she paced her apartment in a state almost bordering on distraction, to find herself, and all she most loved on earth, prisoners to so cruel a foe, She turned to the weeping sisters, not so much to ask their advice, as to express the dreadful fears she entertained on their account, lest, in his fury, the Baron should put them to death, as he was said to be very malignant and revengeful.

As the Countess thus poured out her griefs to them, she said, "I care not for myself, I could bear my fate with patience. But when I think of you, my children, for such you are to me, I wish the most impossible things on your account, so that I could but see you safe. I wish that you had wings, like the birds in the air, to fly away from these towers, and seek shelter afar off in some place of security."

"Wings, to fly like the birds!" exclaimed Mabel. "O dearest madam, there is one bird in my keeping, whose wings may serve us so well as to do all you wish, The bird, the bird in the golden-wired cage! Who among us has forgotten the words of that grand lady, the Princess Picket?--

'This bird, I give, will bear a letter

Wherever bid--can bird do better?'

Dear madam, let me venture to be counsellor on this occasion--it is one of great danger, and we must do our best to combat it. Do you instantly write a letter to your gallant cousin, Sir William Courtenay. Tell him all that has happened, and how you are situated; and beg him to lose no time in coming himself, with his brave men-at-arms, to your relief. I will venture to say, that he will soon drive this usurping tyrant out of your castle."

The Countess of Devon thought the advice of Mabel so good that she lost not a moment in acting upon it. She wrote the letter: the pretty bird was taken from its cage; and with a silken string, she tied the paper round its glossy neck. The window was then opened; and the Countess and all her fair train of daughters, crowded around it to see the feathered messenger set off on his errand. Mabel pronounced these words, as she let fly her little favorite:--

"Fly, pretty bird, and through the air

To Courtenay swift my letter bear."

The bird with a cheerful note, as if in assent to her desire, outstretched its wings, and in another instant commenced his flight towards the county of Cornwall. But though he was gone, the anxiety of the Countess had not flown away with him. She remembered however swiftly the bird might fly, it was far to Tregony, and that Sir William Courtenay and his men could not come so fast to her relief, as the letter could speed to him to ask it; and what might happen in the interval, she feared even to think upon.

Greatly were those fears increased, when on the next evening, the Baron La Zouch entered her chamber, where she was sitting surrounded by her seven fair daughters now in tears and drooping like the lilies when the drops of dew are on their heads. The Baron appeared calm and stately, which rather surprised his prisoners. He shewed some courtesy in his manner towards the Countess, and begged her to favour him by hearing patiently what he had to say. He then drew from under his cloak a piece of written parchment. The Countess, who wished not to irritate a man in whose power she was so completely placed, suppressed her emotions, and as patiently as she could prepared to listen to him. He thus proceeded:--

"You must be aware, Countess of Devon, that you and these fair gentlewomen, and all in this castle, are so entirely in my power, that, with a word, I could consign both you and them to the lowest dungeon, or, even worse, to instant death."

"I need not to be reminded," replied the Countess with dignity, "that I am the conquered, and you the conqueror. But it more becomes you as a man, as a knight, as a gentleman, to shew mercy to me and mine, than it becomes me to ask it."

"True, haughty lady," he said, "but mercy is usually asked before it is granted. However, that you may see my disposition towards you is generous, I, who could enforce obedience, come to propose terms; and though only such as are just to myself, yet are they full of mercy to you and yours.

The Countess cheered up a little at hearing this. With what feelings then of indignation did she listen to what followed! To terms the most hard and unjust, and (no longer treated with courtesy) to which she was rather commanded than solicited to accede, in these words, "Sign this," as the Baron La Zouch spread the written parchment before her on the table, placed the ink-horn by its side. seized with his rough and gauntleted hand her slender fingers, and put into them a pen, and with his rude grasp endeavoured to make her write her name. But she stoutly resisted, saying, "What is it you would have me sign?"

"The resignation of this castle and its dependencies to me, the rightful owner; a resignation for ever; am I not flow its master?"

"I will never sign it," said the Countess. "I will never do my son, now absent, so great a wrong, though by his own generous act, he has made the castle mine. He gave it, and to him, as its rightful lord, shall it return at my death. I will not sign the paper."

"You refuse to do so then?" said the Baron.

"I do and firmly," replied the Countess.

"Your fate then is sealed," exclaimed La Zouch. "You have deep dungeons in this castle, Madam, they will tell no tales, let what will be acted in them. Many a death-groan have they heard, but may be not the last. Obdurate woman, I will myself see you safely lodged, where your body, like your pride, may find itself brought low before the morning.

With the utmost fury he sprang upon the Countess, as a wild animal springs upon its helpless prey. With his iron grasp he held both her wrists in his hands, and commenced dragging her across the room towards the door, as the sisters vainly endeavoured by their prayers and tears to intercede for their benefactress.

At that moment sounds of the sweetest music came from a remote part of the large chamber, with such a gush of sweetness, that the Baron stopped, and seemed as if suddenly fixed like a statue to the spot where he stood. He still held the Countess by her hands; she was on her knees before him; his body was bent in the act of drawing her along the floor after him. So he remained, but there was no more violence. Gradually, as sound succeeded sound, as note after note dropped on his ear, now high and piercing, but still sweet, like those of the lark as she ascends in the morning air above the clouds, or as a volume of harmony rolled through the apartment, he relaxed his hold. Though the Countess was free from his grasp, his hands continued in a position as if he still held her. Now was he red; now pale. Then would he tremble as if every nerve vibrated to the "concord of sweet sounds." Scarcely did he draw his breath, for fear of breaking the spell by which his soul was so entranced. At length his head drooped; a faintness seemed to overpower him, he staggered and fell upon a couch that stood near.

On seeing this, Mabel approached and whispered in the ear of her sister--"Drink, drink, give him drink; and with it give the sleeping potion. He will then slumber for one whole hour. Lose no time; for, O sister, sister, I hear the approach of horsemen. Look out! See who comes."

"I see them! I see them!" exclaimed Margaret, as she rushed to the window. "A noble troop of horsemen; their banner is that of Courtenay. See how he leads them on! But O they are but a small band; they can never gain this castle by force of arms, and we are lost!"

"Not so," said Mabel softly. "See, he is still under the spell of Ursula's lute. She still touches its chords, and he is a very child. Give him the drink, and all is safe."

Without the loss of another moment, Margaret who had the potion given her by the Princess Pickett, flew to a beaufet that was in the room, poured out a cup of wine, and mingled with it the sleeping potion. The Baron, faint from the power of the music, which had so completely overwhelmed his soul, took the cup from her hand, and at once drank off the contents. In a few minutes the force of the drug became evident; he was fast locked in the arms of sleep.

"This will last but one hour," said the Countess." What must now be done? All the doors are locked upon us; we are still but as caged birds."

"But here is that which shall give us liberty," said sister Alice. "The key! the key!

"Through every door this little key

Will give escape or entrance free.

"But we must wait till the watch is withdrawn from near the postern gate, for that is the only way we may escape unobserved."

"You are right," said the Countess. "And the subterraneous passage, which runs under the moat, is wholly unknown to the Baron or his men. That passage is entered by a secret door, which covers the steps by which you descend to it, near the postern. I know well the way and the secret. My son taught it to me when he made me mistress of this castle. I know all, and I will be your guide. We must take a lamp with us, for no light can enter that subterranean vault. See how the moon rises over the hills, and tips with her silver beams the tops of the forest trees. in half an hour all the castle will be still, and then for our escape."

Nothing impeded it. The key which the Princess Pickett had given to the sister, with the power to open all locks, gave the Countess and her seven adopted children a free access to every gallery and winding stair to the walls of the postern, without let or danger. And in like manner they entered and passed the subterranean passage without risk. But as they issued from it on the opposite side of the moat, the watch stationed on the battlements of the castle saw figures, which he could not very well distinguish; he knew not if they were men or women, for a cloud at the instant passed over the moon and rendered every object dark or obscure; so, being as reckless as the Baron, his master, and not heeding who might be struck, he let fly an arrow at the persons he observed in the distance.

The shaft, though aimed at random, struck the Countess in the bosom; she gave a piercing shriek, and fell. The sisters flew to her aid. Isabel had not forgotten the virtue of what seemed, at the time it was presented, a poor and mean gift--the dried, and apparently withered, herbs. She immediately took the little parcel from under her cloak, where she had purposely secured it on the previous night, ran and moistened a sprig in the waters of a spring that was near the spot, and, in another minute, applied it to the wound of the Countess, which she bound up with her scarf. That noble-minded lady no longer felt pain or weakness of any kind; and, accompanied by her seven fair daughters, hastened to join Sir William Courtenay and his band. She at once put him in possession of the secret respecting the subterranean entrance into the castle, gave him the key that opened all locks, bade him despatch, and lose not a moment in securing the means thus to surprise the castle, whilst the guilty Baron and his men were at rest. For herself, she intimated her intention to take shelter in a convent close at hand on the borders of the forest, the abbess of which was her particular friend, and she had been a benefactress to her and to the nuns. All succeeded to her wish. She and the young ladies were soon housed for the night in safety, whilst Sir William Courtenay gathered around him his brave men-at-arms, and, in less than an hour, surprised the castle, and made prisoners of the bold Baron, and all his followers and wicked friends.

The next day Sir. William went to the convent, to bring back the Countess and her adopted children once more in peace to her own home. Whilst on their road, near the outskirts of the forest, they saw a goodly company approaching to meet them. First appeared a car, drawn by four milk-white horses, and well attended by ladies, knights, esquires, and pages; but all of very small stature, except one individual, an elderly female, of the usual height of ordinary mortals; and an elderly man, still taller, walked by her side.

The Countess soon perceived that the bright and jewelled lady, seated in the car, was no other than her old acquaintance, the Princess Pickett. She and all her train stopped at the very spot where, so many years before, the seven children had been found in the basket by the Countess of Devon, and saved by her, with the assistance of her bloodhound, from a watery grave; the noble animal, though grown very old, now again sprang to her side; for he never forsook his mistress.

The car stopped. The Princess, sparkling and glittering with splendour, rose from her seat, and thus addressed the seven sisters, who came forward to give her a thankful greeting for the precious gifts she had bestowed on them at their last meeting:--

"Ye Seven, who thus have done your duty,

Ye shall have wisdom, wealth, and beauty.

And, to increase your joy the more,

I your own mother here restore;

And, in this aged hermit, find

Your Father, penitent and kind."

So saying, the Pixy Princess, with great delight, led forward, in the one hand, Bridget, and, in the other, Randolph Rowle, who was no other than the aged hermit the Countess had seen in the forest on a former occasion, when he had served her so well. That Randolph, once so wicked, but now so penitent, had, for many years past, been the sorrowing recluse of those woods, where he had sought to hide his guilt and his shame from all the world.

The seven daughters now gathered round their long lost mother, kissed and embraced her in the fondest manner; and falling on their knees before their father, begged his blessing with some tremour of the nerves. The Pixy then remounted her car, waved her hand in token of farewell, and, followed by her train, in a moment disappeared. She seemed to be enveloped in a mist that suddenly surrounded the spot where she bade the last adieu.

The father of the seven children withdrew again to his hermitage, there to end his days. The Countess of Devon, much affected by their re-union with their mother, rejoiced to think that she had been the means of preserving their lives so many years before.

In memory, therefore, of that event she gave a large yearly donation to the poor; and with true thankfulness caused Seven Crosses to be erected on the spot, where the seven babes had been saved from a cruel death. About a hundred years ago, they were still to be seen to the admiration of all travellers, as they listened to this wonderful tale. But I know not if now there could be found even one remaining of the

SEVEN CROSSES OF TIVERTON.

NOTES TO "THE SEVEN CROSSES OF TIVERTON; OR, THE STORY OF PIXY PICKETT."

The quaint old author, Westcote, above mentioned, gives the following account of the Seven Crosses of Tiverton. He begins by stating, that a poor labouring man of that town had, by his wife, seven sons at a birth, "which being so secretly kept, as but known to himself and his wife; he, despairing of Divine Providence (which never deceiveth them that depend thereon, but giveth meat to every mouth, and filleth with his blessing every living thing), resolveth to let them swim in our river, and to that purpose puts them all into a large basket, and takes his way towards the river. The Countess (of Devon) having been somewhere abroad to take the air, or doing rather some pious work, meets him with his basket, and by some, no doubt Divine, inspiration, demands what he carried in his basket. The silly man, stricken dead well near with that question, answers, they were whelps. 'Let me see them,' quoth the lady. 'They are puppies,' replied he again, 'not worth the rearing.' 'I will see,' quoth the good Countess; and the loather he was to show them, the more earnest was she to see them: which he perceiving, fell on his knees and discovered his purpose, with all former circumstances; which understood, she hasteth home with them, provides nurses and all things else necessary. They all live, are bred in learning, and, being come to man's estate, gives each a prebend in this parish. which I think are vanished not to he seen, but the Seven Crosses near Tiverton, set up by this occasion, keeps it yet in memory."