On the Spanish Main, by John Masefield

CHAPTER XVI

SHIPS AND RIGS

Galleys—Dromonds—Galliasses—Pinnaces—Pavesses—Top-arming—Banners—Boats

Until the reign of Henry VIII. the shipping of these islands was of two kinds. There were longships, propelled, for the most part, by oars, and used generally as warships; and there were roundships, or dromonds, propelled by sails, and used as a rule for the carriage of freight. The dromond, in war-time, was sometimes converted into a warship, by the addition of fighting-castles fore and aft. The longship, in peace time, was no doubt used as a trader, as far as her shallow draught, and small beam, allowed.

The longship, or galley, being, essentially, an oar vessel, had to fulfil certain simple conditions. She had to be light, or men might not row her. She had to be long, or she might not carry enough oarsmen to propel her with sufficient swiftness. Her lightness, and lack of draught, made it impossible for her to carry much provision; while the number of her oars made it necessary for her to carry a large crew of rowers, in addition to her soldiers and sail trimmers. It was therefore impossible for such a ship to keep the seas for any length of time, even had their build fitted them for the buffetings of the stormy home waters. For short cruises, coast work, rapid forays, and "shock tactics," she was admirable; but she could not stray far from a friendly port, nor put out in foul weather. The roundship, dromond, or cargo boat, was often little[292] more than two beams long, and therefore far too slow to compete with ships of the galley type. She could stand heavy weather better than the galley, and she needed fewer hands, and could carry more provisions, but she was almost useless as a ship of war.

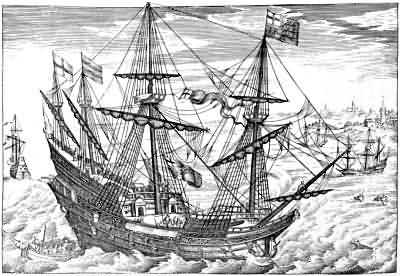

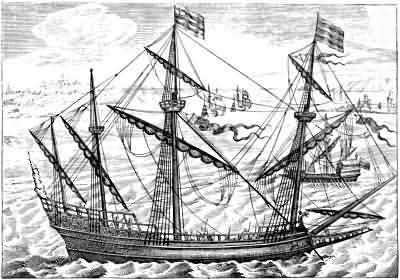

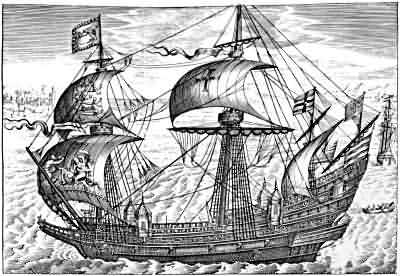

In the reign of Henry VIII. the shipwrights of this country began to build ships which combined something of the strength, and capacity of the dromond, with the length and fineness of the galley. The ships they evolved were mainly dependent upon their sails, but they carried a bank of oars on each side, for use in light weather. The galley, or longship, had carried guns on a platform at the bows, pointing forward. But these new vessels carried guns in broadside, in addition to the bow-chasers. These broadside guns were at first mounted en barbette, pointing over the bulwarks. Early in the sixteenth century the port-hole, with a hinged lid, was invented, and the guns were then pointed through the ship's sides. As these ships carried more guns than the galleys, they were built more strongly, lest the shock of the explosions should shake them to pieces. They were strong enough to keep the seas in bad weather, yet they had enough of the galley build to enable them to sail fast when the oars were laid inboard. It is thought that they could have made as much as four or five knots an hour. These ships were known as galliasses,[18] and galleons, according to the proportions between their lengths and beams. The galleons were shorter in proportion to their breadth than the galliasses.[19] There was another kind of vessel, the pinnace, which had an even greater proportionate length than the galliasse. Of the three kinds, the galleon, being the shortest in proportion to her breadth, was the least fitted for oar propulsion.

[293] During the reign of Elizabeth, the galleon, or great ship, and the galliasse, or cruiser, grew to gradual perfection, in the hands of our great sailors. If we look upon the galleon or great ship as the prototype of the ship of the line, and on the galliasse as the prototype of the frigate, and on the pinnace as the prototype of the sloop, or corvette, we shall not be far wrong. They were, of course, in many ways inferior to the ships which fought in the great French wars, two centuries later, but their general appearance was similar. The rig was different, but not markedly so, while the hulls of the ships presented many points of general likeness. The Elizabethan ships were, however, very much smaller than most of the rated ships in use in the eighteenth century.

The galleon, or great ship, at the end of the sixteenth century, was sometimes of as much as 900 tons. She was generally low in the waist, with a high square forecastle forward, a high quarter-deck, raised above the waist, just abaft the main-mast, and a poop above the quarter-deck, sloping upward to the taffrail. These high outerworks were shut off from the open waist (the space between the main-mast and the forecastle) by wooden bulkheads, which were pierced for small, quick-firing guns. Below the upper, or spar deck, she had a gun-deck, if not more than one, with guns on each side, and right aft. The galliasse was sometimes flush-decked, without poop and forecastle, and sometimes built with both, but she was never so "high charged" as the galleon. The pinnace was as the galliasse, though smaller.

The galleon's waist was often without bulwarks, so that when she went into action it became necessary to give her sail trimmers, and spar-deck fighting men, some protection from the enemy's shot.[20] Sometimes this was done by the[294] hauling up of waist-trees, or spars of rough untrimmed timber, to form a sort of wooden wall. Sometimes they rigged what was called a top-arming, or top armour, a strip of cloth like the "war girdle" of the Norse longships, across the unprotected space. This top-arming was of canvas some two bolts deep (3 feet 6 inches), gaily painted in designs of red, yellow, green, and white. It gave no protection against shot, but it prevented the enemy's gunners from taking aim at the deck, or from playing upon the hatchways with their murderers and pateraroes. It also kept out boarders, and was a fairly good shield to catch the arrows and crossbow bolts shot from the enemy's tops. Sometimes the top-arming was of scantling, or thin plank, in which case it was called a pavesse. Pavesses were very beautifully painted with armorial bearings, arranged in shields, a sort of reminiscence of the old Norse custom of hanging the ship's sides with shields. Another way was to mask the open space with a ranged hemp cable, which could be cleared away after the fight.

The ships were rigged much as they were rigged two centuries later. The chief differences were in the rigging of the bowsprit and of the two after masts. Forward the ships had bowsprits, on which each set a spritsail, from a spritsail yard. The foremast was stepped well forward, almost over the spring of the cutwater. Generally, but not always, it was made of a single tree (pine or fir). If it was what was known as "a made mast," it was built up of two, or three, or four, different trees, judiciously sawn, well seasoned, and then hooped together. Masts were pole-masts until early in the reign of Elizabeth, when a fixed topmast was added. By Drake's time they had learned that a movable topmast was more useful, and less dangerous for ships sailing in these waters. The caps and tops were made of elm wood. The sails on the foremast were foresail and foretop-sail, the latter much the smaller[295] and less important of the two. They were set on wooden yards, the foreyard and foretopsail-yard, both of which could be sent on deck in foul weather. The main-mast was stepped a little abaft the beam, and carried three sails, the main-sail, the main topsail, and a third, the main topgallant-sail. This third sail did not set from a yard until many years after its introduction. It began life like a modern "moon-raker," a triangular piece of canvas, setting from the truck, or summit of the topmast, to the yardarm of the main topsail-yard. Up above it, on a bending light pole, fluttered the great colours, a George's cross of scarlet on a ground of white. Abaft the main-mast were the mizzen, carrying one sail, on a lateen yard, one arm of which nearly touched the deck; and the bonaventure mizzen (which we now call the jigger) rigged in exactly the same way. Right aft, was a banner pole for the display of colours. These masts were stepped, stayed, and supported almost exactly as masts are rigged to-day, though where we use iron, and wire, they used wood and hemp. The shrouds of the fore and main masts led outboard, to "chains" or strong platforms projecting from the ship's sides. These "chains" were clamped to the ship's sides with rigid links of iron. The shrouds of the after masts were generally set up within the bulwarks. On each mast, just above the lower yard, yet below the masthead, was a fighting-top built of elm wood and gilded over. It was a little platform, resting on battens, and in ancient times it was circular, with a diameter of perhaps six or seven feet. It had a parapet round it, inclining outboard, perhaps four feet in height. It was entered by a lubber's hole in the flooring, through which the shrouds passed. In each top was an arm chest containing Spanish darts, crossbows, longbows, arrows, bolts, and perhaps granadoes. When the ship went into battle a few picked marksmen were stationed in the tops with orders to[296] search the enemy's decks with their missiles, particularly the afterparts, where the helmsman stood. In later days the tops were armed with light guns, of the sorts known as slings and fowlers; but top-fighting with firearms was dangerous, as the gunners carried lighted matches, and there was always a risk of sparks, from the match, or from the wads, setting fire to the sails. The running rigging was arranged much as running rigging is arranged to-day, though its quality, in those times, was probably worse than nowadays. The rope appears to have been very fickle stuff which carried away under slight provocation. The blocks were bad, for the sheaves were made of some comparatively soft wood, which swelled, when wet, and jammed. Lignum vitæ was not used for block-sheaves until after the Dutch War in Cromwell's time. Iron blocks were in use in the time of Henry VIII. but only as fair-leads for chain topsail sheets, and as snatches for the boarding of the "takkes." The shrouds and stays, were of hawser stuff, extremely thick nine-stranded hemp; and all those parts exposed to chafing (as from a sail, or a rope) were either served, or neatly covered up with matting. The matting was made by the sailors, of rope, or white line, plaited curiously. When in its place it was neatly painted, or tarred, much as one may see it in Norwegian ships at the present day. The yardarms, and possibly the chains, were at one time fitted with heavy steel sickles, projecting outboard, which were kept sharp, so that, when running alongside an enemy, they might cut her rigging to pieces. These sickles were known as sheer-hooks. They were probably of little use, for they became obsolete before the end of the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

Most of the sails used in these old ships were woven in Portsmouth on hand-looms. The canvas was probably of good quality, as good perhaps as the modern stout No. 1, for hand-woven stuff is always tighter, tougher,[297] better put together, than that woven by the big steam-loom. It was at one time the custom to decorate the sail, with a design of coloured cloth, cut out, as one cuts out a paper pattern, and stitched upon its face with sail twine. In the royal ships this design was of lions rampant, cut out of scarlet say. The custom of carrying such coloured canvas appears to have died out by the end of the sixteenth century. Perhaps flag signalling had come into vogue making it necessary to abandon anything that might tend to confuse the colours. About the same time we abandoned the custom of making our ships gay with little flags, of red and white linen, in guidons like those on a trooper's lance. All through the Tudor reigns our ships carried them, but for some reason the practice was allowed to die out. A last relic of it still flutters on blue water in the little ribbons of the wind-vane, on the weather side the poop, aboard sailing ships.

The great ship carried three boats, which were stowed on chocks in the waist, just forward of the main-mast, one inside the other when not in use. The boats were, the long boat, a large, roomy boat with a movable mast; the cock, cog or cok boat, sometimes called the galley-watt; and the whale, or jolly boat, a sort of small balenger, with an iron-plated bow, which rowed fourteen oars. It was the custom to tow one or more of these boats astern, when at sea, except in foul weather, much as one may see a brig, or a topsail schooner, to-day, with a dinghy dragging astern. The boat's coxswain stayed in her as she towed, making her clean, fending her off, and looking out for any unfortunate who chanced to fall overboard.

Authorities.—W. Charnock: "History of Marine Architecture." Julian Corbett: "Drake and the Tudor Navy." A. Jal: "Archeologie Navale"; "Glossaire Nautique." Sir W. Monson: "Naval Tracts." Sir H. Nicholas: "History of the Royal Navy." M. Oppenheim: "History of the Administration of the Royal Navy"; "Naval Inventories of the Reign of Henry VII."

[18] See Charnock's "Marine Architecture."

[19] See Corbett's "Drake and the Tudor Navy."

[20] See Sir W. Monson, "Naval Tracts," and Sir R. Hawkins, "Observations," etc.