On the Spanish Main, by John Masefield

CHAPTER XIV

THE BATTLE OF PERICO

Arica—The South Sea cruise

On 23rd April 1680, "that day being dedicated to St George, our Patron of England," the canoas arrived off Panama. "We came," says Ringrose, "before sunrise within view of the city of Panama, which makes a pleasant show to the vessels that are at sea." They were within sight of the old cathedral church, "the beautiful building whereof" made a landmark for them, reminding one of the buccaneers "of St Paul's in London," a church at that time little more than a ruin. The new city was not quite finished, but the walls of it were built, and there were several splendid churches, with scaffolding about them, rising high, here and there, over the roofs of the houses. The townspeople were in a state of panic at the news of the pirates' coming. Many of them had fled into the savannahs; for it chanced that, at that time, many of the troops in garrison, were up the country, at war with a tribe of Indians. The best of the citizens, under Don Jacinto de Baronha, the admiral of those seas, had manned the ships in the bay. Old Don Peralta, who had saved the golden galleon ten years before, had 'listed a number of negroes, and manned one or two barques with them. With the troops still in barracks, and these volunteers and pressed men, they had manned, in all "five great ships, and three pretty big barks." Their force may have numbered 280 men. One account gives the number, definitely, as 228. The buccaneer force[246] has been variously stated, but it appears certain that the canoas, and periaguas, which took part in the fight, contained only sixty-eight of their company. Sharp, as we have seen, had gone with his company to the Pearl Islands. The remaining 117 men were probably becalmed, in their barques and canoas, some miles from the vanguard.

When the buccaneers caught sight of Panama, they were probably between that city and the islands of Perico and Tobagilla. They were in great disorder, and the men were utterly weary with the long night of rowing in the rain, with the wind ahead. They were strung out over several miles of sea, with five light canoas, containing six or seven men apiece, a mile or two in advance. After these came two lumbering periaguas, with sixteen men in each. King Golden Cap was in one of these latter. Dampier and Wafer were probably not engaged in this action. Ringrose was in the vanguard, in a small canoa.

A few minutes after they had sighted the roofs of Panama, they made out the ships at anchor off the Isle of Perico. There were "five great ships and three pretty big barks," manned, as we have said, by soldiers, negroes, and citizens. The men aboard this fleet were in the rigging of their ships, keeping a strict lookout. As they caught sight of the pirates the three barques "instantly weighed anchor," and bore down to engage, under all the sail they could crowd. The great ships had not sufficient men to fight their guns. They remained at anchor; but their crews went aboard the barques, so that the decks of the three men-of-war must have been inconveniently crowded. The Spaniards were dead to windwind of the pirates, so that they merely squared their yards, and ran down the wind "designedly to show their valour." They had intended to run down the canoas, and to sail over them, for their captains had orders to[247] give no quarter to the pirates, but to kill them, every man. "Such bloody commands as these," adds Ringrose piously, "do seldom or never prosper."

It was now a little after sunrise. The wind was light but steady; the sea calm. As the Spaniards drew within range, the pirates rowed up into the wind's eye, and got to windward of them. Their pistols and muskets had not been wetted in the rain, for each buccaneer had provided himself with an oiled cover for his firearms, the mouth of which he stopped with wax whenever it rained. The Spanish ships ran past the three leading canoas, exchanging volleys at long range. They were formed in line of battle ahead, with a ship manned by mulattoes, or "Tawnymores," in the van. This ship ran between the fourth canoa, in which Ringrose was, and the fifth (to leeward of her) commanded by Sawkins. As she ran between the boats she fired two thundering broadsides, one from each battery, which wounded five buccaneers. "But he paid dear for his passage"; because the buccaneers gave her a volley which killed half her sail trimmers, so that she was long in wearing round to repeat her fire. At this moment the two periaguas came into action, and got to windward with the rest of the pirates' fleet.

While Ringrose's company were ramming the bullets down their gun muzzles, the Spanish admiral (in the second ship) engaged, "scarce giving us time to charge." She was a fleet ship, and had a good way on her, and her design was to pass between two canoas, and give to each a roaring hot broadside. As she ran down, so near that the buccaneers could look right into her, one of the pirates fired his musket at her helmsman, and shot him through the heart as he steered. The ship at once "broached-to," and lay with her sails flat aback, stopped dead. The five canoas, and one of the periaguas, got under her stern, and[248] so plied her with shot that her decks were like shambles, running with blood and brains, five minutes after she came to the wind. Meanwhile Richard Sawkins ran his canoa—which was a mere sieve of cedar wood, owing to the broadside—alongside the second periagua, and took her steering oar. He ordered his men to give way heartily, for the third Spanish ship, under old Don Peralta, was now bearing down to relieve the admiral. Before she got near enough to blow the canoas out of water, Captain Sawkins ran her on board, and so swept her decks with shot that she went no farther. But "between him and Captain Sawkins, the dispute, or fight, was very hot, lying board on board together, and both giving and receiving death unto each other as fast as they could charge." Indeed, the fight, at this juncture, was extremely fierce. The two Spanish ships in action were surrounded with smoke and fire, the men "giving and receiving death" most gallantly. The third ship, with her sail trimmers dead, was to leeward, trying to get upon the other tack.

After a time her sailors got her round, and reached to windward, to help the admiral, who was now being sorely battered. Ringrose, and Captain Springer, a famous pirate, "stood off to meet him," in two canoas, as "he made up directly towards the Admiral." Don Jacinto, they noticed, as they shoved off from his flagship, was standing on his quarter-deck, waving "with a handkerchief," to the captain of the Tawnymores' ship. He was signalling him to scatter the canoas astern of the flagship. It was a dangerous moment, and Ringrose plainly saw "how hard it would go with us if we should be beaten from the Admiral's stern." With the two canoas he ran down to engage, pouring in such fearful volleys of bullets that they covered the Spaniard's decks with corpses and dying men. "We killed so many of them, that the vessel had scarce men enough left alive, or unwounded, to carry[249] her off. Had he not given us the helm, and made away from us, we had certainly been on board him." Her decks were littered with corpses, and she was literally running blood. The wind was now blowing fresh, and she contrived to put before it, and so ran out of action, a terrible sight for the Panama women.

Having thus put the Tawnymores out of action, Ringrose and Springer hauled to the wind, and "came about again upon the Admiral, and all together gave a loud halloo." The cheer was answered by Sawkins' men, from the periagua, as they fired into the frigate's ports. Ringrose ran alongside the admiral, and crept "so close" under the vessel's stern, "that we wedged up the rudder." The admiral was shot, and killed, a moment later, as he brought aft a few musketeers to fire out of the stern ports. The ship's pilot, or sailing master, was killed by the same volley. As for the crew, the "stout Biscayners," "they were almost quite disabled and disheartened likewise, seeing what a bloody massacre we had made among them with our shot." Two-thirds of the crew were killed, "and many others wounded." The survivors cried out for quarter, which had been offered to them several times before, "and as stoutly denied until then." Captain Coxon thereupon swarmed up her sides, with a gang of pirates, helping up after him the valorous Peter Harris "who had been shot through both his legs, as he boldly adventured up along the side of the ship." The Biscayners were driven from their guns, disarmed, and thrust down on to the ballast, under a guard. All the wounded pirates were helped up to the deck and made comfortable. Then, in all haste, the unhurt men manned two canoas, and rowed off to help Captain Sawkins, "who now had been three times beaten from on board by Peralta."

A very obstinate and bloody fight had been raging round the third man-of-war. Her sides were splintered[250] with musket-balls. She was oozing blood from her scuppers, yet "the old and stout Spaniard" in command, was cheerily giving shot for shot. "Indeed, to give our enemies their due, no men in the world did ever act more bravely than these Spaniards."

Ringrose's canoa was the first to second Captain Sawkins. She ran close in, "under Peralta's side," and poured in a blasting full volley through her after gun-ports. A scrap of blazing wad fell among the red-clay powder jars in the after magazine. Before she could fire a shot in answer, she blew up abaft. Ringrose from the canoa "saw his men blown up, that were abaft the mast, some of them falling on the deck, and others into the sea." But even this disaster did not daunt old Peralta. Like a gallant sea-captain, he slung a bowline round his waist, and went over the side, burnt as he was, to pick up the men who had been blown overboard. The pirates fired at him in the water, but the bullets missed him. He regained his ship, and the fight went on. While the old man was cheering the wounded to their guns, "another jar of powder took fire forward," blowing the gun's crews which were on the fo'c's'le into the sea. The forward half of the ship caught fire, and poured forth a volume of black smoke, in the midst of which Richard Sawkins boarded, and "took the ship." A few minutes later, Basil Ringrose went on board, to give what aid he could to the hurt. "And indeed," he says, "such a miserable sight I never saw in my life, for not one man there was found, but was either killed, desperately wounded, or horribly burnt with powder, insomuch that their black skins [the ship was manned with negroes] were turned white in several places, the powder having torn it from their flesh and bones." But if Peralta's ship was a charnel-house, the admiral's flagship was a reeking slaughter-pen. Of her eighty-six sailors, sixty-one had been killed. Of the[251] remaining twenty-five, "only eight were able to bear arms, all the rest being desperately wounded, and by their wounds totally disabled to make any resistance, or defend themselves. Their blood ran down the decks in whole streams, and scarce one place in the ship was found that was free from blood." The loss on the Tawnymores' ship was never known, but there had been such "bloody massacre" aboard her, that two other barques, in Panama Roads, had been too scared to join battle, though they had got under sail to engage. According to Ringrose, the pirates lost eighteen men killed, and twenty-two men wounded, several of them severely. Sharp, who was not in the fight, gives the numbers as eleven killed, and thirty-four wounded. The battle began "about half an hour after sunrise." The last of the Spanish fire ceased a little before noon.

Having taken the men-of-war, Captain Sawkins asked his prisoners how many men were aboard the galleons, in the Perico anchorage. Don Peralta, who was on deck, "much burnt in both his hands," and "sadly scalded," at once replied that "in the biggest alone there were three hundred and fifty men," while the others were manned in proportion to their tonnage. But one of his men "who lay a-dying upon the deck, contradicted him as he was speaking, and told Captain Sawkins there was not one man on board any of those ships that were in view." "This relation" was believed, "as proceeding from a dying man," and a few moments later it was proved to be true. The greatest of the galleons, "the Most Blessed Trinity," perhaps the very ship in which Peralta had saved the treasures of the cathedral church, was found to be empty. Her lading of "wine, sugar, and sweetmeats, skins and soap" (or hides and tallow) was still in the hold, but the Spaniards had deserted her, after they had set her on fire, "made a hole in her, and loosened [perhaps cut[252] adrift] her foresail." The pirates quenched the fire, stopped the leak, and placed their wounded men aboard her, "and thus constituted her for the time being our hospital." They lay at anchor, at Perico, for the rest of that day. On the 24th of April they seem to have been joined by a large company of those who had been to leeward at the time of the battle. Reinforced by these, to the strength of nearly 200 men, they weighed their anchors, set two of the prize galleons on fire with their freights of flour and iron, and removed their fleet to the roads of Panama. They anchored near the city, just out of heavy gunshot, in plain view of the citizens. They could see the famous stone walls, which had cost so much gold that the Spanish King, in his palace at Madrid, had asked his minister whether they could be seen from the palace windows. They marked the stately, great churches which were building. They saw the tower of St Anastasius in the distance, white and stately, like a blossom above the greenwood. They may even have seen the terrified people in the streets, following the banners of the church, and the priests in their black robes, to celebrate a solemn Mass and invocation. Very far away, in the green savannahs, they saw the herds of cattle straying between the clumps of trees.

Late that night, long after it was dark, Captain Bartholomew Sharp joined company. He had been to Chepillo to look for them, and had found their fire "not yet out," and a few dead Spaniards, whom the Indians had killed, lying about the embers. He had been much concerned for the safety of the expedition, and was therefore very pleased to find that "through the Divine Assistance" the buccaneers had triumphed. At supper that night he talked with Don Peralta, who told him of some comets, "two strange Comets," which had perplexed the Quito merchants the year before. There was "good[253] Store of Wine" aboard the Trinity galleon, with which all hands "cheered up their Hearts for a While." Then, having set sentinels, they turned in for the night.

The next day they buried Captain Peter Harris, "a brave and stout Soldier, and a valiant Englishman, born in the county of Kent, whose death [from gunshot wounds] we very much lamented." With him they buried another buccaneer who had been hurt in the fight. The other wounded men recovered. They would probably have landed to sack the town on this day, had not a quarrel broken out between some of the company and Captain Coxon. The question had been brought forward, whether the buccaneers should go cruising in the South Sea, in their prizes, or return, overland, to their ships at Golden Island. It was probably suggested, as another alternative, that they should land to sack the town. All the captains with one exception were for staying in the Pacific "to try their Fortunes." Captain Coxon, however, was for returning to Golden Island. He had been dissatisfied ever since the fight at Santa Maria. He had not distinguished himself particularly in the fight off Perico, and no doubt he felt jealous that the honours of that battle should have been won by Sawkins. Sawkins' men taunted him with "backwardness" in that engagement, and "stickled not to defame, or brand him with the note of cowardice." To this he answered that he would be very glad to leave that association, and that he would take one of the prizes, a ship of fifty tons, and a periagua, to carry his men up the Santa Maria River. Those who stayed, he added, might heal his wounded. That night he drew off his company, with several other men, in all about seventy hands. With them he carried "the best of our Doctors and Medicines," and the hearty ill will of the other buccaneers. Old King Golden Cap accompanied these deserters, leaving behind him his son and a nephew, desiring them to be "not less[254] vigorous" than he had been in harrying the Spanish. Just before Coxon set sail, he asked Bartholomew Sharp to accompany him. But that proven soul "could not hear of so dirty and inhuman an Action without detestation." So Coxon sailed without ally, "which will not much redound to his Honour," leaving all his wounded on the deck of the captured galleon. The fleet, it may be added, had by this time returned to the anchorage at Perico.

They lay there ten days in all, "debating what were best to be done." In that time they took a frigate laden with fowls. They took the poultry for their own use, and dismissed some of "the meanest of the prisoners" in the empty ship. They then shifted their anchorage to the island of Taboga, where there were a few houses, which some drunken pirates set on fire. While they lay at this island the merchants of Panama came off to them "and sold us what commodities we needed, buying also of us much of the goods we had taken in their own vessels." The pirates also sold them a number of negroes they had captured, receiving "two hundred pieces of eight for each negro we could spare." "And here we took likewise several barks that were laden with fowls." After Coxon's defection, Richard Sawkins was re-elected admiral, and continued in that command till his death some days later.

Before they left Taboga, Captain Sharp went cruising to an island some miles distant to pick up some straggling drunkards who belonged to his ship. While he lay at anchor, in a dead calm, waiting for a breeze to blow, a great Spanish merchant ship hove in sight, bound from Lima (or Truxillo) to Panama. Sharp ran his canoas alongside, and bade her dowse her colours, at the same time sending a gang of pirates over her rail, to throw the crew under hatches. "He had no Arms to defend himself with, save only Rapiers," so her captain made no battle, but struck incontinently. She proved to be a very splendid[255] prize, for in her hold were nearly 2000 jars of wine and brandy, 100 jars of good vinegar, and a quantity of powder and shot, "which came very luckily." In addition to these goods there were 51,000 pieces of eight, "247 pieces of eight a man," a pile of silver sent to pay the Panama soldiery; and a store of sweetmeats, such as Peru is still famous for. And there were "other Things," says Sharp, "that were very grateful to our dis-satisfied Minds." Some of the wine and brandy were sold to the Panama merchants a few days later, "to the value of three thousand Pieces of Eight." A day or two after this they snapped up two flour ships, from Paita. One of these was a pretty ship of a fine model, of about 100 tons. Sharp fitted her for himself, "for I liked her very well." The other flour ship was taken very gallantly, under a furious gunfire from Panama Castle. The buccaneers rowed in, with the cannon-balls flying over their heads. They got close alongside "under her Guns," and then towed her out of cannon-shot.

They continued several days at Taboga, waiting for a Lima treasure ship, aboard which, the Spaniards told them, were £2500 in silver dollars. While they waited for this ship the Governor at Panama wrote to ask them why they had come into those seas. Captain Sawkins answered that they had come to help King Golden Cap, the King of Darien, the true lord of those lands, and that, since they had come so far, "there was no reason but that they should have some satisfaction." If the Governor would send them 500 pieces of eight for each man, and double that sum for each captain, and, further, undertake "not any farther to annoy the Indians," why, then, the pirates would leave those seas, "and go away peaceably. If the Governor would not agree to these terms, he might look to suffer." A day or two later, Sawkins heard that the Bishop of Panama had been[256] Bishop at Santa Martha (a little city on the Main), some years before, when he (Sawkins) helped to sack the place. He remembered the cleric favourably, and sent him "two loaves of sugar," as a sort of keepsake, or love-offering. "For a retaliation," the Bishop sent him a gold ring; which was very Christian in the Bishop, who must have lost on the exchange. The bearer of the gold ring, brought also an answer from the Governor, who desired to know who had signed the pirates' commissions. To this message Captain Sawkins sent back for answer: "That as yet all his company were not come together, but that when they were come up, we would come and visit him at Panama, and bring our commissions on the muzzles of our guns, at which time he should read them as plain as the flame of gunpowder could make them."

With this thrasonical challenge the pirates set sail for Otoque, another of the islands in the bay; for Taboga, though it was "an exceeding pleasant island," was by this time bare of meat. Before they left the place a Frenchman deserted from them, and gave a detailed account of their plans to the Spanish Governor. It blew very hard while they were at sea, and two barques parted company in the storm. One of them drove away to the eastward, and overtook John Coxon's company. The other was taken by the Spaniards.

About the 20th or 21st of May, after several days of coasting, the ships dropped anchor on the north coast of the island of Quibo. From here some sixty men, under Captain Sawkins, set sail in Edmund Cook's ship, to attack Pueblo Nuevo, the New Town, situated on the banks of a river. At the river's mouth, which was broad, with sandy beaches, they embarked in canoas, and rowed upstream, under the pilotage of a negro, from dark till dawn. The French deserter had told the Spaniards of the intended attack, so that the canoas found great[257] difficulty in getting upstream. Trees had been felled so as to fall across the river, and Indian spies had been placed here and there along the river-bank to warn the townsmen of the approach of the boats. A mile below the town the river had been made impassable, so here the pirates went ashore to wait till daybreak. When it grew light they marched forward, to attack the strong wooden breastworks which the Spaniards had built. Captain Sawkins was in advance, with about a dozen pirates. Captain Sharp followed at a little distance with some thirty more. As soon as Sawkins saw the stockades he fired his gun, and ran forward gallantly, to take the place by storm, in the face of a fierce fire. "Being a man that nothing upon Earth could terrifie" he actually reached the breastwork, and was shot dead there, as he hacked at the pales. Two other pirates were killed at his side, and five of the brave forlorn were badly hurt. "The remainder drew off, still skirmishing," and contrived to reach the canoas "in pretty good order," though they were followed by Spanish sharpshooters for some distance. Sharp took command of the boats and brought them off safely to the river's mouth, where they took a barque full of maize, before they arrived at their ship.

Sawkins was "as valiant and courageous as any could be," "a valiant and generous-spirited man, and beloved above any other we ever had among us, which he well deserved." His death left the company without a captain, and many of the buccaneers, who had truly loved Richard Sawkins, were averse to serving under another commander. They were particularly averse to serving under Sharp, who took the chief command from the moment of Sawkins' death. At Quibo, where they lay at anchor, "their Mutiny" grew very high, nor did they stick at mere mutiny. They clamoured for a tarpaulin muster, or "full Councel," at which the question of "who should be chief"[258] might be put to the vote. At the council, Sharp was elected "by a few hands," but many of the pirates refused to follow him on the cruise. He swore, indeed, that he would take them such a voyage as should bring them £1000 a man; but the oaths of Sharp were not good security, and the mutiny was not abated. Many of the buccaneers would have gone home with Coxon had it not been for Sawkins. These now clamoured to go so vehemently that Sharp was constrained to give them a ship with as much provision "as would serve for treble the number." The mutineers who left on this occasion were in number sixty-three. Twelve Indians, the last who remained among the pirates, went with them, to guide them over the isthmus. 146 men remained with Sharp. It is probable that many of these would have returned at this time, had it not been that "the Rains were now already up, and it would be hard passing so many Gullies, which of necessity would then be full of water." Ringrose, Wafer and Dampier remained among the faithful, but rather on this account, than for any love they bore their leader. The mutineers had hardly set sail, before Captain Cook came "a-Board" Sharp's flagship, finding "himselfe a-grieved." His company had kicked him out of his ship, swearing that they would not sail with such a one, so that he had determined "to rule over such unruly folk no longer." Sharp gave his command to a pirate named Cox, a New Englander, "who forced kindred, as was thought, upon Captain Sharp, out of old acquaintance, in this conjuncture of time, only to advance himself." Cox took with him Don Peralta, the stout old Andalusian, for the pirates were plying the captain "of the Money-Ship we took," to induce him to pilot them to Guayaquil "where we might lay down our Silver, and lade our vessels with Gold." They feared that an honest man, such as Peralta, "would hinder the en[259]deavours" of this Captain Juan, and corrupt his kindly disposition.

With these mutinies, quarrels, intrigues, and cabals did the buccaneers beguile their time. They stayed at Quibo until 6th June, filling their water casks, quarrelling, cutting wood, and eating turtle and red deer. They also ate huge oysters, so large "that we were forced to cut them into four pieces, each quarter being a large mouthful."

On the 6th of June they set sail for the isle of Gorgona, off what is now Columbia, where they careened the Trinity, and took "down our Round House Coach and all the high carved work belonging to the stern of the ship; for when we took her from the Spaniards she was high as any Third Rate Ship in England." While they were at work upon her, Sharp changed his design of going for Guayaquil, as one of their prisoners, an old Moor, "who had long time sailed among the Spaniards," told him that there was gold at Arica, in such plenty that they would get there "£2000 a man." He did not hurry to leave his careenage, though he must have known that each day he stayed there lessened his chance of booty. It was nearly August when he left Gorgona, and "from this Time forward to the 17th of October there was Nothing occurr'd but bare Sailing." Now and then they ran short of water, or of food. One or two of their men died of fever, or of rum, or of sunstroke. Two or three were killed in capturing a small Spanish ship. The only other events recorded, are the falls of rain, the direction of the wind, the sight of "watersnakes of divers colours," and the joyful meeting with Captain Cox, whom they had lost sight of, while close in shore one evening. They called at "Sir Francis Drake's isle" to strike a few tortoises, and to shoot some goats. Captain Sharp we read, here "showed himself very ingenious" in spearing turtle, "he performing it as well as the tortoise strikers themselves."[260]

It was very hot at this little island. Many years before Drake had gone ashore there to make a dividend, and had emptied bowls of gold coins into the hats of his men, after the capture of the Cacafuego. Some of the pirates sounded the little anchorage with a greasy lead, in the hopes of bringing up the golden pieces which Drake had been unable to carry home, and had hove into the sea there. They got no gold, but the sun shone "so hot that it burnt the skin off the necks of our men," as they craned over the rail at their fishery.

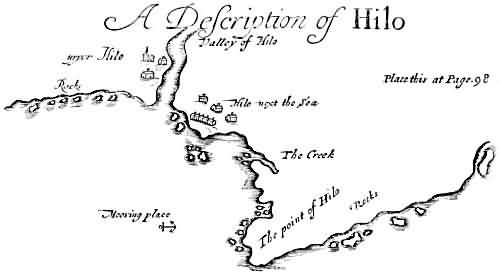

At the end of October they landed at the town of Hilo to fill fresh water. They took the town, and sacked its sugar refineries, which they burnt. They pillaged its pleasant orange groves, and carried away many sacks of limes and green figs "with many other fruits agreeable to the palate." Fruit, sugar, and excellent olive oil were the goods which Hilo yielded. They tried to force the Spaniards to bring them beef, but as the beef did not come, they wrecked the oil and sugar works, and set them blazing, and so marched down to their ships, skirmishing with the Spanish horse as they fell back. Among the spoil was the carcass of a mule (which made "a very good meal"), and a box of chocolate "so that now we had each morning a dish of that pleasant liquor," such as the grand English ladies drank.

The next town attacked was La Serena, a town five miles from the present Coquimbo. They took the town, and found a little silver, but the citizens had had time to hide their gold. The pirates made a great feast of strawberries "as big as walnuts," in the "orchards of fruit" at this place, so that one of their company wrote that "'tis very delightful Living here." They could not get a ransom for the town, so they set it on fire. The Spaniards, in revenge, sent out an Indian, on an inflated horse hide, to the pirates' ship the Trinity. This Indian[261] thrust some oakum and brimstone between the rudder and the sternpost, and "fired it with a match." The sternpost caught fire and sent up a prodigious black smoke, which warned the pirates that their ship was ablaze. They did not discover the trick for a few minutes, but by good fortune they found it out in time to save the vessel. They landed their prisoners shortly after the fire had been quenched "because we feared lest by the example of this stratagem they should plot our destruction in earnest." Old Don Peralta, who had lately been "very frantic," "through too much hardship and melancholy," was there set on shore, after his long captivity. Don Juan, the captain of the "Money-Ship," was landed with him. Perhaps the two fought together, on the point of honour, as soon as they had returned to swords and civilisation.

From Coquimbo the pirates sailed for Juan Fernandez. On the way thither they buried William Cammock, one of their men, who had drunk too hard at La Serena "which produced in him a calenture or malignant fever, and a hiccough." "In the evening when the pale Magellan Clouds were showing we buried him in the sea, according to the usual custom of mariners, giving him three French vollies for his funeral."

On Christmas Day they were beating up to moorings, with boats ahead, sounding out a channel for the ship. They did not neglect to keep the day holy, for "we gave in the morning early three vollies of shot for solemnization of that great festival." At dusk they anchored "in a stately bay that we found there," a bay of intensely blue water, through which the whiskered seals swam. The pirates filled fresh water, and killed a number of goats, with which the island swarmed. They also captured many goats alive, and tethered them about the decks of the Trinity, to the annoyance of all hands, a day or two[262] later, when some flurries of wind drove them to sea, to search out a new anchorage.

Shortly after New Year's Day 1681, "our unhappy Divisions, which had been long on Foot, began now to come to an Head to some Purpose." The men had been working at the caulking of their ship, with design to take her through the Straits of Magellan, and so home to the Indies. Many of the men wished to cruise the South Seas a little longer, while nearly all were averse to plying caulking irons, under a burning sun, for several hours a day. There was also a good deal of bitterness against Captain Sharp, who had made but a poor successor to brave Richard Sawkins. He had brought them none of the gold and silver he had promised them, and few of the men were "satisfied, either with his Courage or Behaviour." On the 6th January a gang of pirates "got privately ashoar together," and held a fo'c's'le council under the greenwood. They "held a Consult," says Sharp, "about turning me presently out, and put another in my Room." John Cox, the "true-hearted dissembling New-England Man," whom Sharp "meerly for old Acquaintance-sake" had promoted to be captain, was "the Main Promoter of their Design." When the consult was over, the pirates came on board, clapped Mr Sharp in irons, put him down on the ballast, and voted an old pirate named John Watling, "a stout seaman," to be captain in his stead. One buccaneer says that "the true occasion of the grudge against Sharp was, that he had got by these adventures almost a thousand pounds, whereas many of our men were not worth a groat," having "lost all their money to their fellow Buccaneers at dice."

Captain Edmund Cook, who had been turned out of his ship by his men, was this day put in irons on the confession of a shameless servant. The curious will find[263] the details of the case on page 121, of the 1684 edition of Ringrose's journal.

John Watling began his captaincy in very godly sort, by ordering his disciples to keep holy the Sabbath day. Sunday, "January the ninth, was the first Sunday that ever we kept by command and common consent, since the loss and death of our valiant Commander Captain Sawkins." Sawkins had been strict in religious matters, and had once thrown the ship's dice overboard "finding them in use on the said day." Since Sawkins' death the company had grown notoriously lax, but it is pleasant to notice how soon they returned to their natural piety, under a godly leader. With Edmund Cook down on the ballast in irons, and William Cook talking of salvation in the galley, and old John Watling expounding the Gospel in the cabin, the galleon, "the Most Holy Trinity" must have seemed a foretaste of the New Jerusalem. The fiddler ceased such "prophane strophes" as "Abel Brown," "The Red-haired Man's Wife," and "Valentinian." He tuned his devout strings to songs of Zion. Nay the very boatswain could not pipe the cutter up but to a phrase of the Psalms.

In this blessed state they washed their clothes in the brooks, hunted goats across the island, and burnt and tallowed their ship the Trinity. But on the 12th of January, one of their boats, which had been along the coast with some hunters, came rowing furiously into the harbour, "firing of Guns." They had espied three Spanish men-of-war some three or four miles to leeward, beating up to the island under a press of sail. The pirates were in great confusion, for most of them were ashore, "washing their clothes," or felling timber. Those on board, hove up one of their anchors, fired guns to call the rest aboard, hoisted their boats in, and slipped their second cable. They then stood to sea, hauling as close to the[264] wind as she would lie. One of the Mosquito Indians, "one William," was left behind on the island, "at this sudden departure," and remained hidden there, living on fish and fruit, for many weary days. He was not the first man to be marooned there; nor was he to be the last.

The three Spanish men-of-war were ships of good size, mounting some thirty guns among them. As the pirate ship beat out of the harbour, sheeting home her topgallant-sails, they "put out their bloody flags," which the pirates imitated, "to shew them that we were not as yet daunted." They kept too close together for the pirates to run them aboard, but towards sunset their flagship had drawn ahead of the squadron. The pirates at once tacked about so as to engage her, intending to sweep her decks with bullets, and carry her by boarding. John Watling was not very willing to come to handystrokes, nor were the Spaniards anxious to give him the opportunity. No guns were fired, for the Spanish admiral wore ship, and so sailed away to the island, when he brought his squadron to anchor. The pirates called a council, and decided to give them the slip, having "outbraved them," and done as much as honour called for. They were not very pleased with John Watling, and many were clamouring for the cruise to end. It was decided that they should not attack the Spanish ships, but go off for the Main, to sack the town of Arica, where there was gold enough, so they had heard, to buy them each "a coach and horses." They therefore hauled to the wind again, and stood to the east, in very angry and mutinous spirit, until the 26th of January.

On that day they landed at Yqueque, a mud-flat, or guano island, off a line of yellow sand-hills. They found a few Indian huts there, with scaffolds for the drying of fish, and many split and rotting mackerel waiting to be carried inland. There was a dirty stone chapel in[265] the place, "stuck full of hides and sealskins." There was a great surf, green and mighty, bursting about the island with a continual roaring. There were pelicans fishing there, and a few Indians curing fish, and an abominable smell, and a boat, with a cask in her bows, which brought fresh water thither from thirty miles to the north. The teeth of the Indians were dyed a bright green by their chewing of the coca leaf, the drug which made their "beast-like" lives endurable. There was a silver mine on the mainland, near this fishing village, but the pirates did not land to plunder it. They merely took a few old Indian men, and some Spaniards, and carried them aboard the Trinity, where the godly John Watling examined them.

The next day the examination continued; and the answers of one of the old men, "a Mestizo Indian," were judged to be false. "Finding him in many lies, as we thought, concerning Arica, our commander ordered him to be shot to death, which was accordingly done." This cold-blooded murder was committed much against the will of Captain Sharp, who "opposed it as much as he could." Indeed, when he found that his protests were useless, he took a basin of water (of which the ship was in sore need) and washed his hands, like a modern Pilate. "Gentlemen," he said, "I am clear of the blood of this old man; and I will warrant you a hot day for this piece of cruelty, whenever we come to fight at Arica." This proved to be "a true and certain prophesy." Sharp was an astrologer, and a believer in portents; but he does not tell us whether he had "erected any Figure," to discover what was to chance in the Arica raid.

Arica, the most northern port in Chile, has still a considerable importance. It is a pleasant town, fairly well watered, and therefore more green and cheerful than[266] the nitrate ports. It is built at the foot of a hill (a famous battlefield) called the Morro. Low, yellow sand-hills ring it in, shutting it from the vast blue crags of the Andes, which rise up, splintered and snowy, to the east. The air there is of an intense clearness, and those who live there can see the Tacna churches, forty miles away. It is no longer the port it was, but it does a fair trade in salt and sulphur, and supplies the nitrate towns with fruit. When the pirates landed there it was a rich and prosperous city. It had a strong fort, mounting twelve brass guns, defended by four companies of troops from Lima. The city had a town guard of 300 soldiers. There was also an arsenal full of firearms for the use of householders in the event of an attack. It was not exactly a walled town, like new Panama, but a light wooden palisade ran round it, while other palisades crossed each street. These defences had been thrown up when news had arrived of the pirates being in those seas. All the "plate, gold and jewels" of the townsfolk had been carefully hidden, and the place was in such a state of military vigilance and readiness that the pirates had no possible chance of taking it, or at least of holding it. When the pirates came upon it there were several ships in the bay, laden with commodities from the south of Chile.

On the 28th of January, John Watling picked 100 men, and put off for the shore in boats and canoas, to attack the town. By the next day they had got close in shore, under the rocks by the San Vitor River's mouth. There they lay concealed till the night. At dawn of the 30th January 1681, "the Martyrdom of our glorious King Charles the First," they were dipping off some rocks four miles to the south of Arica. Here ninety-two of the buccaneers landed, leaving a small boat guard, with strict instructions how to act. They were told that if[267] the main body "made one smoke from the town," as by firing a heap of powder, one canoa was to put in to Arica; but that, if two smokes were fired, all the boats were to put in at once. Basil Ringrose was one of those who landed to take part in the fight. Dampier, it is almost certain, remained on board the Trinity, becalmed some miles from the shore. Wafer was in the canoas, with the boat guard, preparing salves for those wounded in the fight. The day seems to have been hot and sunny—it could scarcely have been otherwise—but those out at sea, on the galleon, could see the streamers of cloud wreathing about the Andes.

At sunrise the buccaneers got ashore, amongst the rocks, and scrambled up a hill which gave them a sight of the city. From the summit they could look right down upon the streets, little more than a mile from them. It was too early for folk to be stirring, and the streets were deserted, save for the yellow pariahs, and one or two carrion birds. It was so still, in that little town, that the pirates thought they would surprise the place, as Drake had surprised Nombre de Dios. But while they were marching downhill, they saw three horsemen watching them from a lookout place, and presently the horsemen galloped off to raise the inhabitants. As they galloped away, John Watling chose out forty of the ninety-two, to attack the fort or castle which defended the city. This band of forty, among whom were Sharp and Ringrose, carried ten hand-grenades, in addition to their pistols and guns. The fort was on a hill above the town, and thither the storming party marched, while Watling's company pressed on into the streets. The action began a few minutes later with the guns of the fort firing on the storming party. Down in the town, almost at the same moment, the musketry opened in a long roaring roll which never slackened. Ringrose's[268] party waited for no further signal, but at once engaged, running in under the guns and hurling their firepots through the embrasures. The grenades were damp, or badly filled, or had been too long charged. They did not burst or burn as they should have done, while the garrison inside the fort kept up so hot a fire, at close range, that nothing could be done there. The storming party fell back, without loss, and rallied for a fresh attack. They noticed then that Watling's men were getting no farther towards the town. They were halted in line, with their knees on the ground, firing on the breastworks, and receiving a terrible fire from the Spaniards. Five of the fifty-two men were down (three of them killed) and the case was growing serious. The storming party left the fort, and doubled downhill into the firing line, where they poured in volley after blasting volley, killing a Spaniard at each shot, making "a very desperate battle" of it, "our rage increasing with our wounds." No troops could stand such file-firing. The battle became "mere bloody massacre," and the Spaniards were beaten from their posts. Volley after volley shook them, for the pirates "filled every street in the city with dead bodies"; and at last ran in upon them, and clubbed them and cut them down, and penned them in as prisoners. But as the Spaniards under arms were at least twenty times as many as the pirates, there was no taking the city from them. They were beaten from post to post fighting like devils, but the pirates no sooner left a post they had taken, "than they came another way, and manned it again, with new forces and fresh men." The streets were heaped with corpses, yet the Spaniards came on, and came on again, till the sand of the roads was like red mud. At last they were fairly beaten from the chief parts of the town, and numbers of them were penned up as prisoners; more, in fact, than the pirates[269] could guard. The battle paused for a while at this stage, and the pirates took advantage of the lull to get their wounded (perhaps a dozen men), into one of the churches to have their wounds dressed. As the doctors of the party began their work, John Watling sent a message to the fort, charging the garrison to surrender. The soldiers returned no answer, but continued to load their guns, being helped by the armed townsfolk, who now flocked to them in scores. The fort was full of musketeers when the pirates made their second attack a little after noon.

At the second attack, John Watling took 100 of his prisoners, placed them in front of his storming party, and forced them forward, as a screen to his men, when he made his charge. The garrison shot down friend and foe indiscriminately, and repulsed the attack, and repulsed a second attack which followed a few minutes later. There was no taking the fort by storm, and the pirates had no great guns with which to batter it. They found, however, that one of the flat-roofed houses in the town, near the fort's outworks, commanded the interior. "We got upon the top of the house," says Ringrose, "and from there fired down into the fort, killing many of their men and wounding them at our ease and pleasure." While they were doing this, a number of the Lima soldiers joined the citizens, and fell, with great fury, upon the prisoners' guards in the town. They easily beat back the few guards, and retook the city. As soon as they had taken the town, they came swarming out to cut off the pirates from their retreat, and to hem them in between the fort and the sea. They were in such numbers that they were able to surround the pirates, who now began to lose men at every volley, and to look about them a little anxiously as they bit their cartridges. From every street in the town came Spanish musketeers at the double, swarm after[270] swarm of them, perhaps a couple of thousand. The pirates left the fort, and turned to the main army, at the same time edging away towards the south, to the hospital, or church, where their wounded men were being dressed. As they moved away from the battlefield, firing as they retreated, old John Watling was shot in the liver with a bullet, and fell dead there, to go buccaneering no more. A moment later "both our quartermasters" fell, with half-a-dozen others, including the boatswain. All this time the cannon of the fort were pounding over them, and the round-shot were striking the ground all about, flinging the sand into their faces. What with the dust and the heat and the trouble of helping the many hurt, their condition was desperate. "So that now the enemy rallying against us, and beating us from place to place, we were in a very distracted condition, and in more likelihood to perish every man than escape the bloodiness of that day. Now we found the words of Captain Sharp to bear a true prophecy, being all very sensible that we had had a day too hot for us, after that cruel heat in killing and murdering in cold blood the old Mestizo Indian whom we had taken prisoner at Yqueque." In fact they were beaten and broken, and the fear of death was on them, and the Spaniards were ringing them round, and the firing was roaring from every point. They were a bloody, dusty, choking gang of desperates, "in great disorder," black with powder, their tongues hanging out with thirst. As they stood grouped together, cursing and firing, some of them asked Captain Sharp to take command, and get them out of that, seeing that Watling was dead, and no one there could give an order. To this request Sharp at last consented, and a retreat was begun, under cover of a fighting rear-guard, "and I hope," says Sharp, "it will not be esteemed a Vanity in me to say, that I was mighty Helpful to facilitate this Retreat."[271] In the midst of a fearful racket of musketry, he fought the pirates through the soldiers to the church where the wounded lay. There was no time, nor was there any conveyance, for the wounded, and they were left lying there, all desperately hurt. The two surgeons could have been saved "but that they had been drinking while we assaulted the fort, and thus would not come with us when they were called." There was no time for a second call, for the Spaniards were closing in on them, and the firing was as fierce as ever. The men were so faint with hunger and thirst, the heat of battle, and the long day's marching, that Sharp feared he would never get them to the boats. A fierce rush of Spaniards beat them away from the hospital, and drove them out of the town "into the Savannas or open fields." The Spaniards gave a cheer and charged in to end the battle, but the pirates were a dogged lot, and not yet at the end of their strength. They got into a clump or cluster, with a few wounded men in the centre, to load the muskets, "resolving to die one by another" rather than to run. They stood firm, cursing and damning the Spaniards, telling them to come on, and calling them a lot of cowards. There were not fifty buccaneers fit to carry a musket, but the forty odd, unhurt men stood steadily, and poured in such withering volleys of shot, with such terrible precision, that the Spanish charge went to pieces. As the charge broke, the pirates plied them again, and made a "bloody massacre" of them, so that they ran to shelter like so many frightened rabbits. The forty-seven had beaten off twenty or thirty times their number, and had won themselves a passage home.

There was no question of trying to retake the town. The men were in such misery that the march back to the boats taxed their strength to the breaking point. They set off over the savannah, in as good order as they could,[272] with a wounded man, or two, in every rank of them. As they set forward, a company of horsemen rode out, and got upon their flanks "and fired at us all the way, though they would not come within reach of our guns; for their own reached farther than ours, and out-shot us more than one third." There was great danger of these horsemen cutting in, and destroying them, on the long open rolls of savannah, so Sharp gave the word, and the force shogged westward to the seashore, along which they trudged to the boats. The beach to the south of Arica runs along the coast, in a narrow strip, under cliffs and rocky ground, for several miles. The sand is strewn with boulders, so that the horsemen, though they followed the pirates, could make no concerted charge upon them. Some of them rode ahead of them and got above them on the cliff tops, from which they rolled down "great stones and whole rocks to destroy us." None of these stones did any harm to the pirates, for the cliffs were so rough and broken that the skipping boulders always flew wide of the mark. But though the pirates "escaped their malice for that time," they were yet to run a terrible danger before getting clear away to sea. The Spaniards had been examining, or torturing, the wounded pirates, and the two drunken surgeons, left behind in the town. "These gave them our signs that we had left to our boats [i.e. revealed the signals by which the boats were to be called] so that they immediately blew up two smokes, which were perceived by the canoas." Had the pirates "not come at the instant" to the seaside, within hail of the boats, they would have been gone. Indeed they were already under sail, and beating slowly up to the northward, in answer to the signal. Thus, by a lucky chance, the whole company escaped destruction. They lost no time in putting from the shore, where they had met with "so very bad Entertainment." They "got on board about ten a Clock[273] at night; having been involved in a continual and bloody fight ... all that day long." Of the ninety-two, who had landed that morning, twenty-eight had been left ashore, either dead, or as prisoners. Of the sixty-four who got to the canoas, eighteen were desperately wounded, and barely able to walk. Most of the others were slightly hurt, while all were too weary to do anything, save sleep or drink. Of the men left behind in the hospital the Spaniards spared the doctors only; "they being able to do them good service in that country." "But as to the wounded men," says Ringrose, "they were all knocked on the head," and so ended their roving, and came to port where drunken doctors could torture them no longer. The Ylo men denied this; and said that the seven pirates who did not die of their wounds were kept as slaves. The Spanish loss is not known, but it was certainly terrible. The Hilo, or Ylo people, some weeks later, said that seventy Spaniards had been killed and about 200 wounded.

All the next day the pirates "plied to and fro in sight of the port," hoping that the Spaniards would man the ships in the bay, and come out to fight. They reinstated Sharp in his command, for they had now "recollected a better Temper," though none of them, it seems, wished for any longer stay in the South Sea. The Arica fight had sickened them of the South Sea, while several of them (including Ringrose) became very ill from the exposure and toil of the battle. They beat to windward, cruising, when they found that the Spaniards would not put to sea to fight them. They met with dirty weather when they had reached the thirtieth parallel, and the foul weather, and their bad fortune made them resolve to leave those seas. At a fo'c's'le council held on the 3rd of March, they determined to put the helm up, and to return to the North Sea. They were short of water and short[274] of food, "having only one cake of bread a day," or perhaps half-a-pound of "doughboy," for their "whack" or allowance. After a few days' running before the wind they came to "the port of Guasco," now Huasco, between Coquimbo and Caldera, a little town of sixty or eighty houses, with copper smeltries, a church, a river, and some sheep-runs. Sixty of the buccaneers went ashore here, that same evening, to get provisions, "and anything else that we could purchase." They passed the night in the church, or "in a churchyard," and in the morning took "120 sheep and fourscore goats," about 200 bushels of corn "ready ground," some fowls, a fat hog, any quantity of fruit, peas, beans, etc., and a small stock of wine. These goods they conveyed aboard as being "fit for our Turn." The inhabitants had removed their gold and silver while the ship came to her anchor, "so that our booty here, besides provisions, was inconsiderable." They found the fat hog "very like our English pork," thereby illustrating the futility of travel; and so sailed away again "to seek greater matters." Before they left, they contrived to fill their water jars in the river, a piece of work which they found troublesome, owing to the height of the banks.

From Huasco, where the famous white raisins grow, they sailed to Ylo, where they heard of their mates at Arica, and secured some wine, figs, sugar, and molasses, and some "fruits just ripe and fit for eating," including "extraordinary good Oranges of the China sort" They then coasted slowly northward, till by Saturday, 16th April, they arrived off the island of Plate. Here their old bickerings broke out again, for many of the pirates were disgusted with Sharp, and eager to go home. Many of the others had recovered their spirits since the affair at Arica, and wished to stay in the South Seas, to cruise a little longer. Those who had fought at Arica would[275] not allow Sharp to be deposed a second time, while those who had been shipkeepers on that occasion, were angry that he should have been re-elected. The two parties refused to be reconciled. They quarrelled angrily whenever they came on deck together, and the party spirit ran so high that the company of shipkeepers, the anti-Sharp faction, "the abler and more experienced men," at last refused to cruise any longer under Sharp's command. The fo'c's'le council decided that a poll should be taken, and "that which party soever, upon polling, should be found to have the majority, should keep the ship." The other party was to take the long boat and the canoas. The division was made, and "Captain Sharp's Party carried it." The night was spent in preparing the long boat and the canoas, and the next morning the boats set sail.