|

|

The Mythology Of Peru

By Lewis Spence

Adapted from Chapter 7, The Myths Of Mexico and Peru

Peruvian Creation Stories | Sun-Worship In Peru | Inca Occupation

of Titicaca

Human Sacrifice in Peru | A

Myth of Manco Ccapac Inca | The Llama's

Warning

The Religion of Ancient Peru

THE religion of the ancient Peruvians had obviously developed in a much shorter time than that of the Mexicans. The more ancient character inherent in it was displayed in the presence of deities many of which were little better than mere totems, and although a definite monotheism or worship of one god appears to have been reached, it was not by the efforts of the priestly caste that this was achieved, but rather by the will of the Inca Pachacutic, who seems to have been a monarch gifted with rare insight and ability a man much after the type of the Mexican Nezahualcoyotl.

In Inca times the religion of the people was solely directed by the state, and regulated in such a manner that independent theological thought was permitted no outlet. But it must not be inferred from this that no change had ever come over the spirit of Peruvian religion. As a matter of fact sweeping changes had been effected, but these had been solely the work of the Inca race, the leaders of which had amalgamated the various faiths of the peoples whom they had conquered into one official belief.

Totemism

Garcilasso el Inca de la Vega, an early Spanish writer on matters Peruvian, states that tradition ran that in ante-Inca times every district, family, and village possessed its own god, each different from the others. These gods were usually such objects as trees, mountains, flowers, herbs, caves, large stones, pieces of jasper, and animals. The jaguar, puma, and bear were worshipped for their strength and fierceness, the monkey and fox for their cunning, the condor for its size and because several tribes believed themselves to be descended from it. The screech-owl was worshipped for its beauty, and the common owl for its power of seeing in the dark. Serpents, particularly the larger and more dangerous varieties, were especially regarded with reverence.

Although Payne classes all these gods together as totems, it is plain that those of the first class the flowers, herbs, caves, and pieces of jasper are merely fetishes. A fetish is an object in which the savage believes to be resident a spirit which, by its magic, will assist him in his undertakings. A totem is an object or an animal, usually the latter, with which the people of a tribe believe themselves to be connected by ties of blood and from which they are descended. It later becomes the type or symbol of the tribe.

Paccariscas

Lakes, springs, rocks, mountains, precipices, and caves were all regarded by the various Peruvian tribes as paccariscas places whence their ancestors had originally issued to the upper world. The paccarisca was usually saluted with the cry,

"Thou art my birth-place, thou art my life-spring. Guard me from evil, O Paccarisca!"

In the holy spot a spirit was supposed to dwell which served the tribe as a kind of oracle. Naturally the paccarisca was looked upon with extreme reverence. It became, indeed, a sort of life-centre for the tribe, from which they were very unwilling to be separated.

Worship of Stones

The worship of stones appears to have been almost as universal in ancient Peru as it was in ancient Palestine. Man in his primitive state believes stones to be the framework of the earth, its bony structure. He considers himself to have emerged from some cave in fact, from the entrails of the earth. Nearly all American creation-myths regard man as thus emanating from the bowels of the great terrestrial mother. Rocks which were thus chosen as paccariscas are found, among many other places, at Calfca, in the valley of the Yucay, and at Titicaca there is a great mass of red sandstone on the top of a high ridge with almost inaccessible slopes and dark, gloomy recesses where the sun was thought to have hidden himself at the time of the great deluge which covered all the earth. The rock of Titicaca was, in fact, the great paccarisca of the sun itself.

We are thus not surprised to find that many standing stones were worshipped in Peru in aboriginal times. Thus Arriaga states that rocks of great size which bore some resemblance to the human figure were imagined to have been at one time gigantic men or spirits who, because they disobeyed the creative power, were turned into stone. According to another account they were said to have suffered this punishment for refusing to listen to the words of Thonapa, the son of the creator, who, like Quetzalcoatl or Manco Ccapac, had taken upon himself the guise of a wandering Indian, so that he might have an opportunity of bringing the arts of civilisation to the aborigines. At Tiahuanaco a certain group of stones was said to represent all that remained of the villagers of that place, who, instead of paying fitting attention to the wise counsel which Thonapa the Civiliser bestowed upon them, continued to dance and drink in scorn of the teachings he had brought to them.

Again, some stones were said to have become men, as in the old Greek creation-legend of Deucalion and Pyrrha. In the legend of Ccapac Inca Pachacutic, when Cuzco was attacked in force by the Chancas an Indian erected stones to which he attached shields and weapons so that they should appear to represent so many warriors in hiding. Pachacutic, in great need of assistance, cried to them with such vehemence to come to his help that they became men, and rendered him splendid service.

Huacas

Whatever was sacred, of sacred origin, or of the nature of a relic the Peruvians designated a huaca, from the root huacan, to howl, native worship invariably taking the form of a kind of howl, or weird, dirge-like wailing. All objects of reverence were known as huacas, although those of a higher class were also alluded to as viracoehas. The Peruvians had, naturally, many forms of huaca, the most popular of which were those of the fetish class which could be carried about by the individual. These were usually stones or pebbles, many of which were carved and painted, and some made to represent human beings. The llama and the ear of maize were perhaps the most usual forms of these sacred objects. Some of them had an agricultural significance. In order that irrigation might proceed favourably a huaca was placed at intervals in proximity to the accquiaS) or irrigation canals, which was supposed to prevent them leaking or otherwise failing to supply a sufficiency of moisture to the parched maize-fields. Huacas of this sort were known as ccompas, and were regarded as deities of great importance, as the food-supply of the community was thought to be wholly dependent upon their assistance. Other huacas of a similar kind were called chichics and huancas^ and these presided over the fortunes of the maize, and ensured that a sufficient supply of rain should be forthcoming. Great numbers of these agricultural fetishes were destroyed by the zealous commissary Hernandez de Avendafio.

The Mamas

Spirits which were supposed to be instrumental in forcing the growth of the maize or other plants were the mamas. We find a similar conception among many Brazilian tribes to-day, so that the idea appears to have been a widely accepted one in South American countries. The Peruvians called such agencies "mothers," adding to the generic name that of the plant or herb with which they were specially associated. Thus acsttmama was the potato-mother, quinuamama the quinua-mother, saramama the maize-mother, and cocamama the mother of the coca-shrub. Of these the saramama was naturally the most important, governing as it did the principal source of the food-supply of the community. Sometimes an image of the saramama was carved in stone, in the shape of an ear of maize. The saramama was also worshipped in the form of a doll, or huantaysara, made out of stalks of maize, renewed at each harvest, much as the idols of the great corn-mother of Mexico were manufactured at each harvest-season. After having. been made, the image was watched over for three nights, and then sacrifice was done to it. The priest or medicine-man of the tribe would then inquire of it whether or not it was capable of existing until that time in the next year. If its spirit replied in the affirmative it was permitted to remain where it was until the following harvest. If not it was removed, burnt, and another figure took its place, to which similar questions were put.

The Huamantantac

Connected with agriculture in some degree was the Huamantantac (He who causes the Cormorants to gather themselves together). This was the agency responsible for the gathering of sea-birds, resulting in the deposits of guano to be found along the Peruvian coast which are so valuable in the cultivation of the maize-plant. He was regarded as a most beneficent spirit, and was sacrificed to with exceeding fervour.

Huaris

The huaris or "great ones," were the ancestors of the aristocrats of a tribe, and were regarded as specially favourable toward agricultural effort, possibly because the land had at one time belonged to them personally. They were sometimes alluded to as the "gods of strength," and were sacrificed to by libations of chicha. Ancestors in general were deeply revered, and had an agricultural significance, in that considerable tracts, of land were tilled in order that they might be supplied with suitable food and drink offerings. As the number of ancestors increased more and more land was brought into cultivation, and the hapless people had their toil added to immeasurably by these constant demands upon them.

Huillcas

The huillcas were huacas which partook of the nature of oracles. Many of these were serpents, trees, and rivers, the noises made by which appeared to the primitive Peruvians as, indeed, they do to primitive folk all over the world to be of the quality of articulate speech. Both the Huillcamayu and the Apurimac rivers at Cuzco were huillca oracles of this kind, as their names, " Huillca-river " and "Great Speaker," denote. These oracles often set the mandate of the Inca himself at defiance, occasionally supporting popular opinion against his policy.

The Oracles of the Andes

The Peruvian Indians of the Andes range within recent generations continued to adhere to the superstitions they had inherited from their fathers. A rare and interesting account of these says that they " admit an evil being, the inhabitant of the centre of the earth, whom they consider as the author of their misfortunes, and at the mention of whose name they tremble. The most shrewd among them take advantage of this belief to obtain respect, and represent themselves as his delegates. Under the denomination of mohanes, or agoreros, they are consulted even on the most trivial occasions. They preside over the intrigues of love, the health of the community, and the taking of the field. Whatever repeatedly occurs to defeat their prognostics, falls on themselves ; and they are wont to pay for their deceptions very dearly. They chew a species of vegetable called piripiri, and throw it into the air, accompanying this act by certain recitals and incantations, to injure some, to benefit others, to procure rain and the inundation of the rivers, or, on the other hand, to occasion settled weather, and a plentiful store of agricultural productions. Any such result, having been casually verified on a single occasion, suffices to confirm the Indians in their faith, although they may have been cheated a thousand times. Fully persuaded that they cannot resist the influence of the piripiri, as soon as they know that they have been solicited in love by its means, they fix their eyes on the impassioned object, and discover a thousand amiable traits, either real or fanciful, which indifference had before concealed from their view. But the principal power, efficacy, and it may be said misfortune of the mohanes consist in the cure of the sick. Every malady is ascribed to their enchantments, and means are instantly taken to ascertain by whom the mischief may have been wrought. For this purpose, the nearest relative takes a quantity of the juice of floripondium, and suddenly falls intoxicated by the violence of the plant. He is placed in a fit posture to prevent suffocation, and on his coming to himself, at the end of three days, the mohane who has the greatest resemblance to the sorcerer he saw in his visions is to undertake the cure, or if, in the interim, the sick man has perished, it is customary to subject him to the same fate. When not any sorcerer occurs in the visions, the first mohane they encounter has the misfortune to represent his image." [Skinner, State of Peru, p. 275.]

Lake Worship in Peru

At Lake Titicaca the Peruvians believed the inhabitants of the earth, animals as well as men, to have been fashioned by the creator, and the district was thus sacrosanct in their eyes. The people of the Collao called it Mamacota (Mother-water), because it furnished them with supplies of food. Two great idols were connected with this worship. One called Copacahuana was made of a bluish-green stone shaped like a fish with a human head, and was placed in a commanding position on the shores of the lake. On the arrival of the Spaniards so deeply rooted was the worship of this goddess that they could only suppress it by raising an image of the Virgin in place of the idol. The Christian emblem remains to this day. Mamacota was venerated as the giver of fish, with which the lake abounded. The other image, Copacati (Serpent-stone), represented the element of water as embodied in the lake itself in the form of an image wreathed in serpents, which in America are nearly always symbolical of water.

The Lost Island

A strange legend is recounted of this lake-goddess. She was chiefly worshipped as the giver of rain, but Huaina Ccapac, who had modern ideas and journeyed through the country casting down huacas had determined to raise on an island of Lake Titicaca a temple to Yatiri (The Ruler), the Aymara name of the god Pachacamac in his form of Pachayachachic. He commenced by raising the new shrine on the island of Titicaca itself. But the deity when called upon refused to vouchsafe any reply to his worshippers or priests. Huaina then commanded that the shrine should be transferred to the island of Apinguela. But the same thing happened there. He then inaugurated a temple on the island of Paapiti, and lavished upon it many sacrifices of llamas, children, and precious metals. But the offended tutelary goddess of the lake, irritated beyond endurance by this invasion of her ancient domain, lashed the watery waste into such a frenzy of storm that the island and the shrine which covered it disappeared beneath the waves and were never thereafter beheld by mortal eye.

The Thunder-God of Peru

The rain-and-thunder god of Peru was worshipped in various parts of the country under various names. Among the Collao he was known as Con, and in that part of the Inca dominions now known as Bolivia he was called Churoquella. Near the cordilleras of the coast he was probably known as Pariacaca, who expelled the huaca of the district by dreadful tempests, hurling rain and hail at him for three days and nights in such quantities as to form the great lake of Pariacaca. Burnt llamas were offered to him. But the Incas, discontented with this local worship, which by no means suited their system of central government, determined to create one thunder-deity to whom all the tribes in the empire must bow as the only god of his class. We are not aware what his name was, but we know from mythological evidence that he was a mixture of all the other gods of thunder in the Peruvian Empire, first because he invariably occupied the third place in the triad of greater deities, the creator, sun, and thunder, all of whom were more or less amalgamations of provincial and metropolitan gods, and secondly because a great image of him was erected in the Coricancha at Cuzco, in which he was represented in human form, wearing a headdress which concealed his face, symbolic of the clouds, which ever veil the thunder-god's head. He had a special temple of his own, moreover, and was assigned a share in the sacred lands by the Inca Pachacutic. He was accompanied by a figure of his sister, who carried jars of water. An unknown Quichuan poet composed on the myth the following graceful little poem, which was translated by the late Daniel Garrison Brinton, an enthusiastic Americanist and professor of American archaeology in the University of Pennsylvania

Bounteous Princess,

Lo, thy brother

Breaks thy vessel

Now in fragments.

From the blow come

Thunder, lightning,

Strokes of lightning;

And thou, Princess,

Tak'it the water,

With it rainest,

And the hail or

Snow dispenses!,

Viracocha,

World-constructor .

It will be observed that the translator here employs the name Viracocha as if it were that of the deity. But it was merely a general expression in use for a more than usually sacred being. Brinton, commenting upon the legend, says:

"In this pretty waif that has floated down to us from the wreck of a literature now for ever lost there is more than one point to attract the notice of the antiquary. He may find in it a hint to decipher those names of divinities so common in Peruvian legends, Contici and Illatici. Both mean 'the Thunder Vase,' and both doubtless refer to the conception here displayed of the phenomena of the thunderstorm."

Alluding to Peruvian thunder-myth elsewhere, he says in an illuminating passage : "Throughout the realms of the Incas the Peruvians venerated as maker of all things and ruler of the firmament the god Ataguju. The legend was that from him proceeded the first mortals, the man Guamansuri, who descended to the earth and there wedded the sister of certain Guachimines, rayless ones or Darklings, who then possessed it. They destroyed him, but their sister gave birth to twin sons, Apocatequil and Piguerao. The former was the more powerful. By touching the corpse of his mother he brought her to life, he drove off and slew the Guachimines, and, directed by Ataguju, released the race of Indians from the soil by turning it up with a spade of gold. For this reason they adored him as their maker. He it was, they thought, who produced the thunder and the lightning by hurling stones with his sling. And the thunderbolts that fall, said they, are his children. Few villages were willing to be without one or more of these. They were in appearance small, round stones, but had the admirable properties of securing fertility to the fields, protecting from lightning, and, by a transition easy to understand, were also adored as gods of fire as well material as of the passions, and were capable of kindling the dangerous flames of desire in the most frigid bosoms. Therefore they were in great esteem as love-charms. Apocatequil's statue was erected on the mountains, with that of his mother on one haryi and his brother on the other. f He was Prince of Evil, and the most respected god of the Peruvians. From Quito to Cuzco not an Indian but would give all he possessed to conciliate him. Five priests, two stewards, and a crowd of slaves served his image. And his chief temple was surrounded by a very considerable village, whose inhabitants had no other occupation but to wait on him.' ' In memory of these brothers twins in Peru were always deemed sacred to the lightning.

There is an instance on record of how the huillca could refuse on occasion to recognise even royalty itself. Manco, the Inca who had been given the kingly power by Pizarro, offered a sacrifice to one of these oracular shrines. The oracle refused to recognise him, through the medium of its guardian priest, stating that Manco was not the rightful Inca. Manco therefore caused the oracle, which was in the shape of a rock, to be thrown down, whereupon its guardian spirit emerged in the form of a parrot and flew away. It is probable that the bird thus liberated had been taught by the priests to answer to the questions of those who came to consult the shrine. But we learn that on Manco commanding that the parrot should be pursued it sought another rock, which opened to receive it, and the spirit of the huilka was transferred to this new abode.

PERUVIAN CREATION-STORIES

The Great God Pachacamac

Later Peruvian mythology recognised only three gods of the first rank, the earth, the thunder, and the creative agency. Pachacamac, the great spirit of earth, derived his name from a word pacha, which may be best translated as "things." In its sense of visible things it is equivalent to " world," applied to things which happen in succession it denotes "time," and to things connected with persons "property," especially clothes. The world of visible things is thus Mamapacha (Earth-Mother), under which name the ancient Peruvians worshipped the earth. Pachacamac, on the other hand, is not the earth itself, the soil, but the spirit which animates all things that emerge therefrom. From him proceed the spirits of the plants and animals which come from the earth. Pachamama is the mother-spirit of the mountains, rocks, and plains, Pachacamac the father-spirit of the grain-bearing plants, animals, birds, and man. In some localities Pachacamac and Pachamama were worshipped as divine mates. Possibly this practice was universal in early times, gradually lapsing into desuetude in later days. Pachamama was in another phase intended to denote the land immediately contiguous to a settlement, on which the inhabitants depended for their food-supply.

It is easy to see how such a conception as Pachacamac, the spirit of animated nature, would become one with the idea of a universal or even a partial creator.

That there was a pre-existing conception of a creative agency can be proved from the existence of the Peruvian name Conticsi-viracocha (He who gives Origin, or Beginning). This conception and that of Pachacamac must at some comparatively early period have clashed, and been amalgamated probably with ease when it was seen how nearly akin were the two ideas. Indeed, Pachacamac was alternatively known as Pacharurac, the "maker" of all things sure proof of his amalgamation with the conception of the creative agency. As such he had his symbol in the great Coricancha at Cuzco, an oval plate of gold, suspended between those of the sun and the moon, and placed vertically, it may be hazarded with some probability, to represent in symbol that universal matrix from which emanated all things. Elsewhere in Cuzco the creator was represented by a stone statue in human form.

Pachayachachic

In later Inca days this idea of a creator assumed that of a direct ruler of the universe, known as Pachayachachic. This change was probably due to the influence of the Inca Pachacutic, who is known to have made several other doctrinal innovations in Peruvian theology. He commanded a great new temple to the creator-god to be built at the north angle of the city of Cuzco, in which he placed a statue of pure gold, of the size of a boy of ten years of age. The small size was to facilitate its removal, as Peruvian worship was nearly always carried out in the open air. In form it represented a man with his right arm elevated, the hand partially closed and the forefinger and thumb raised, as if in the act of uttering the creative word. To this god large possessions and revenues were assigned, for previously service rendered to him had been voluntary only.

Ideas of Creation

It is from aboriginal sources as preserved by the first Spanish colonists that we glean our knowledge of what the Incas believed the creative process to consist. By means of his word (nisca) the creator, a spirit, powerful and opulent, made all things. We are provided with the formulae of his very words by the Peruvian prayers still extant: "Let earth and heaven be," "Let a man be ; let a woman be," "Let there be day," "Let there be night," "Let the light shine." The sun is here regarded as the creative agency, and the ruling caste as the objects of a special act of creation.

Pacari Tampu

Pacari Tampu (House of the Dawn) was the place of origin, according to the later Inca theology, of four brothers and sisters who initiated the four Peruvian systems of worship. The eldest climbed a neighbouring mountain, and cast stones to the four points of the compass, thus indicating that he claimed all the land within sight. But his youngest brother succeeded in enticing him into a cave, which he sealed up with a great stone, thus imprisoning him for ever. He next persuaded his second brother to ascend a lofty mountain, from which he cast him, changing him into a stone in his descent. On beholding the fate of his brethren the third member of the quartette fled. It is obvious that we have here a legend concocted by the later Inca priesthood to account for the evolution of Peruvian religion in its different stages. The first brother would appear to represent the oldest religion in Peru, that of the paccariscas, the second that of a fetishistic stoneworship, the third perhaps that of Viracocha, and the last sun-worship pure and simple. There was, however, an "official" legend, which stated that the sun had three sons, Viracocha, Pachacamac, and Manco Ccapac. To the last the dominion of mankind was given, whilst the others were concerned with the workings of the universe. This politic arrangement placed all the power, temporal and spiritual, in the hands of the reputed descendants of Manco Ccapac the Incas.

Worship of the Sea

The ancient Peruvians worshipped the sea as well as the earth, the folk inland regarding it as a menacing deity, whilst the people of the coast reverenced it as a god of benevolence, calling it Mama-cocha, or Mother-sea, as it yielded them subsistence in the form of fish, on which they chiefly lived. They worshipped the whale, fairly common on that coast, because of its enormous size, and various districts regarded with adoration the species of fish most abundant there. This worship can have partaken in no sense of the nature of totemism, as the system forbade that the totem animal should be eaten. It was imagined that the prototype of each variety of fish dwelt in the upper world, just as many tribes of North American Indians believe that the eponymous ancestors of certain animals dwell at the four points of the compass or in the sky above them. This great fish-god engendered the others of his species, and sent them into the waters of the deep that they might exist there until taken for the use of man. Birds, too, had their eponymous counterparts among the stars, as had animals. Indeed, among many of the South American races, ancient and modern, the constellations were called after certain beasts and birds.

SUN-WORSHIP IN PERU

Viracocha

The Aymara-Quichua race worshipped Viracocha as a great culture hero. They did not offer him sacrifices or tribute, as they thought that he, being creator and possessor of all things, needed nothing from men, so they only gave him worship. After him they idolised the sun. They believed, indeed, that Viracocha had made both sun and moon, after emerging from Lake Titicaca, and that then he made the earth and peopled it. On his travels westward from the lake he was sometimes assailed by men, but he revenged himself by sending terrible storms upon them and destroying their property, so they humbled themselves and acknowledged him as their lord. He forgave them and taught them everything, obtaining from them the name of Pachayachachic. In the end he disappeared in the western ocean. He either created or there were born with him four beings who, according to mythical beliefs, civilised Peru. To them he assigned the four quarters of the earth, and they are thus known as the four winds, north, south, east, and west. One legend avers they came from the cave Pacari, the Lodging of the Dawn.

The name " Inca " means "People of the Sun," which luminary the Incas regarded as their creator. But they did not worship him totemically that is, they did not claim him as a progenitor, although they regarded him as possessing the attributes of a man. And here we may observe a difference between Mexican and Peruvian sun-worship. For whereas the Nahua primarily regarded the orb as the abode of the Man of the Sun, who came to earth in the shape of Quetzalcoatl, the Peruvians looked upon the sun itself as the deity. The Inca race did not identify their ancestors as children of the sun until a comparatively late date. Sun-worship was introduced by the Inca Pachacutic, who averred that the sun appeared to him in a dream and addressed him as his child. Until that time the worship of the sun had always been strictly subordinated to that of the creator, and the deity appeared only as second in the trinity of creator, sun, and thunder. But permanent provision was made for sacrifices to the sun before the other deities were so recognised, and as the conquests of the Incas grew wider and that provision extended to the new territories they came to be known as "the Lands of the Sun," the natives observing the dedication of a part of the country to the luminary, and concluding therefrom that it applied to the whole. The material reality of the sun would enormously assist his cult among a people who were too barbarous to appreciate an unseen god, and this colonial conception reacting upon the mother-land would undoubtedly inspire the military class with a resolve to strengthen a worship so popular in the conquered provinces, and of which they were in great measure the protagonists and missionaries.

The Sun's Possessions

In every Peruvian village the sun had considerable possessions. His estates resembled those of a territorial chieftain, and consisted of a dwelling-house, a chacra, or portion of land, flocks of llamas and pacos, and a number of women dedicated to his service. The cultivation of the soil within the solar enclosure devolved upon the inhabitants of the neighbouring village, the produce of their toil being stored in the inti-huasi, or sun's house. The Women of the Sun prepared the daily food and drink of the luminary, which consisted of maize and chicha. They also spun wool and wove it into fine stuff, which was burned in order that it might ascend to the celestial regions, where the deity could make use of it. Each village reserved a portion of its solar produce for the great festival at Cuzco, and it was carried thither on the backs of llamas which were destined for sacrifice.

Inca Occupation of Titicaca

The Rock of Titicaca, the renowned place of the sun's origin, naturally became an important centre of his worship. The date at which the worship of the sun originated at this famous rock is extremely remote, but we may safely assume that it was long before the conquest of the Collao by the Apu-Ccapac-Inca Pachacutic, and that reverence for the luminary as a war-god by the Colla chiefs was noticed by Tupac, who in suppressing the revolt concluded that the local observance at the rock had some relationship to the disturbance. It is, however, certain that Tupac proceeded after the reconquest to establish at this natural centre of sun-worship solar rites on a new basis, with the evident intention of securing on behalf of the Incas of Cuzco such exclusive benefit as might accrue from the complete possession of the sun's paccarisca. According to a native account, a venerable colla (or hermit), consecrated to the service of the sun, had proceeded on foot from Titicaca to Cuzco for the purpose of commending this ancient seat of sun-worship to the notice of Tupac. The consequence was that Apu-Ccapac-Inca, after visiting the island and inquiring into the ancient local customs, re-established them in a more regular form. His accounts can hardly be accepted in face of the facts which have been gathered. Rather did it naturally follow that Titicaca became subservient to Tupac after the revolt of the Collao had been quelled. Henceforth the worship of the sun at the place of his origin was entrusted to Incas resident in the place, and was celebrated with Inca rites. The island was converted into a solar estate and the aboriginal inhabitants removed. The land was cultivated and the slopes of the hills levelled, maize was sown and the soil consecrated, the grain being regarded as the gift of the sun. This work produced considerable change in the island. Where once was waste and idleness there was now fertility and industry. The harvests were skilfully apportioned, so much being reserved for sacrificial purposes, the remainder being sent to Cuzco, partly to be sown in the chacras, or estates of the sun, throughout Peru, partly to be preserved in the granary of the Inca and the huacas as a symbol that there would be abundant crops in the future and that the grain already stored would be preserved. A building of the Women of the Sun was erected about a mile from the rock, so that the produce might be available for sacrifices. For their maintenance, tribute of potatoes, ocas, and quinua was levied upon the inhabitants of the villages on the shores of the lake, and of maize upon the people of the neighbouring valleys.

Pilgrimages to Titicaca

Titicaca at the time of the conquest was probably more frequented than Pachacamac itself. These two places were held to be the cardinal shrines of the two great huacas, the creator and the sun respectively. A special reason for pilgrimage to Titicaca was to sacrifice to the sun, as the source of physical energy and the giver of long life ; and he was especially worshipped by the aged, who believed he had preserved their lives.

Then followed the migration of pilgrims to Titicaca, for whose shelter houses were built at Capacahuana, and large stores of maize were provided for their use. The ceremonial connected with the sacred rites of the rock was rigorously observed. The pilgrim ere embarking on the raft which conveyed him to the island must first confess his sins to a huillac (a speaker to an object of worship) ; then further confessions were required at each of the three sculptured doors which had successively to be passed before reaching the sacred rock. The first door (Puma-puncu) was surmounted by the figure of a puma; the others (Quenti-puncu and Pillco-puncu) were ornamented with feathers of the different species of birds commonly sacrificed to the sun. Having passed the last portal, the traveller beheld at a distance of two hundred paces the sacred rock itself, the summit glittering with gold-leaf. He was permitted to proceed no further, for only the officials were allowed entry into it. The pilgrim on departing received a few grains of the sacred maize grown on the island. These he kept with care and placed with his own store, believing they would preserve his stock, The confidence the Indian placed in the virtue of the Titicaca maize may be judged from the prevalent belief that the possessor of a single grain would not suffer from starvation during the whole of his life.

Sacrifices to the New Sun

The Intip-Raymi, or Great Festival of the Sun, was celebrated by the Incas at Cuzco at the winter solstice. In connection with it the Tarpuntaita-cuma, or sacrificing Incas, were charged with a remarkable duty, the worshippers journeying eastward to meet one of these functionaries on his way. On the principal hill-tops between Cuzco and Huillcanuta, on the road to the rock of Titicaca, burnt offerings of llamas, coca, and maize were made at the feast to greet the arrival of the young sun from his ancient birthplace. Molina has enumerated more than twenty of these places or sacrifice. The striking picture of the celebration of the solar sacrifice on these bleak mountains in the depth of the Peruvian winter has, it seems, no parallel in the religious rites of the ancient Americans. Quitting their thatched houses at early dawn, the worshippers left the valley below, carrying the sacrificial knife and brazier, and conducting the white llama, heavily laden with fuel, maize, and coca leaves, wrapped in fine cloth, to the spot where the sacrifice was to be made. When sunrise appeared the pile was lighted. The victim was slain and thrown upon it. The scene then presented, a striking contrast to the bleak surrounding wilderness. As the flames grew in strength and the smoke rose higher and thicker the clear atmosphere was gradually illuminated from the east. When the sun advanced above the horizon the sacrifice was at its height. But for the crackling of the flames and the murmur of a babbling stream on its way down the hill to join the river below, the silence had hitherto been unbroken. As the sun rose the Incas marched slowly round the burning mass, plucking the wool from the scorched carcase, and chanting monotonously :

"O Creator, Sun and Thunder, be for ever young! Multiply the people; let them ever be in peace!"

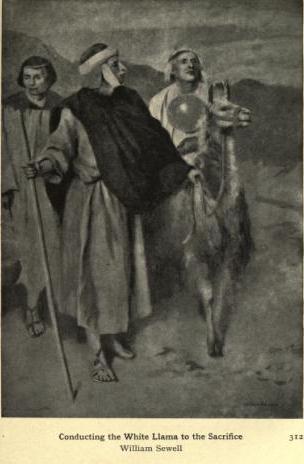

The Citoc Raymi

Conducting the White Llama to the Sacrifice

The most picturesque if not the most important solar festival was that of the Citoc Raymi (Gradually Increasing Sun), held in June, when nine days were given up to the ceremonial. A rigorous fast was observed for three days previous to the event, during which no fire must be kindled. On the fourth day the Inca, accompanied by the people en masse, proceeded to the great square of Cuzco to hail the rising sun, which they awaited in silence. On its appearance they greeted it with a joyous tumult, and, joining in procession, marched to the Golden Temple of the Sun, where llamas were sacrificed, and a new fire was kindled by means of an arched mirror, followed by sacrificial offerings of grain, flowers, animals, and aromatic gums. This festival may be taken as typical of all the seasonal celebrations. The Inca calendar was purely agricultural in its basis, and marked in its great festivals the renewal or abandonment of the labours of the field. Its astronomical observations were not more advanced than those of the calendars of many American races otherwise inferior in civilisation.

Human Sacrifice in Peru

Writers ignorant of their subject have often dwelt upon the absence of human sacrifice in ancient Peru, and have not hesitated to draw comparisons between Mexico and the empire of the Incas in this respect, usually not complimentary to the former. Such statements are contradicted by the clearest evidence. Human sacrifice was certainly not nearly so prevalent in Peru, but that it was regular and by no means rare is well authenticated. Female victims to the sun were taken from the great class of Acllacuna (Selected Ones), a general tribute of female children regularly levied throughout the Inca Empire. Beautiful girls were taken from their parents at the age of eight by the Inca officials, and were handed over to certain female trainers called mamacuna (mothers). These matrons systematically trained their prottgdes in housewifery and ritual. Residences or convents called aclla-huasi (houses of the Selected) were provided for them in the principal cities.

Methods of Medicine-Men

A quaint account of the methods of the medicine-men of the Indians of the Peruvian Andes probably illustrates the manner in which the superstitions of a barbarian people evolve into a more stately ritual.

"It cannot be denied," it states, " that the mohanes [priests] have, by practice and tradition, acquired a knowledge of many plants and poisons, with which they effect surprising cures on the one hand, and do much mischief on the other, but the mania of ascribing the whole to a preternatural virtue occasions them to blend with their practice a thousand charms and superstitions. The most customary method of cure is to place two hammocks close to each other, either in the dwelling, or in the open air : in one of them the patient lies extended, and in the other the mohane, or agorero. The latter, in contact with the sick man, begins by rocking himself, and then proceeds, by a strain in falsetto, to call on the birds, quadrupeds, and fishes to give health to the patient. From time to time he rises on his seat, and makes a thousand extravagant gestures over the sick man, to whom he applies his powders and herbs, or sucks the wounded or diseased parts. If the malady augments, the agorero, having been joined by many of the people, chants a short hymn, addressed to the soul of the patient, with this burden: 'Thou must not go, thou must not go.' In repeating this he is joined by the people, until at length a terrible clamour is raised, and augmented in proportion as the sick man becomes still fainter and fainter, to the end that it may reach his ears. When all the charms are unavailing, and death approaches, the mohane leaps from his hammock, and betakes himself to flight, amid the multitude of sticks, stones, and clods of earth which are showered on him. Successively all those who belong to the nation assemble, and, dividing themselves into bands, each of them (if he who is in his last agonies is a warrior) approaches him, saying:

Whither goest thou? Why dost thou leave us?

With whom shall we proceed to the aucas [the enemies]?'

They then relate to him the heroical deeds he has performed, the number of those he has slain, and the pleasures he leaves behind him. This is practised in different tones: while some raise the voice, it is lowered by others ; and the poor sick man is obliged to support these importunities without a murmur, until the first symptoms of approaching dissolution manifest themselves. Then it is that he is surrounded by a multitude of females, some of whom forcibly close the mouth and eyes, others envelop him in the hammock, oppressing him with the whole of their weight, and causing him to expire before his time, and others, lastly, run to extinguish the candle, and dissipate the smoke, that the soul, not being able to perceive the hole through which it may escape, may remain entangled in the structure of the roof. That this may be speedily effected, and to prevent its return to the interior of the dwelling, they surround the entrances with filth, by the stench of which it may be expelled.

Death by Suffocation

" As soon as the dying man is suffocated by the closing of the mouth, nostrils, etc., and wrapt up in the covering of his bed, the most circumspect Indian, whether male or female, takes him in the arms in the best manner possible, and gives a gentle shriek, which echoes to the bitter lamentations of the immediate relatives, and to the cries of a thousand old women collected for the occasion. As long as this dismal howl subsists, the latter are subjected to a constant fatigue, raising the palm of the hand to wipe away the tears, and lowering it to dry it on the ground. The result of this alternate action is, that a circle of earth, which gives them a most hideous appearance, is collected about the eyelids and brows, and they do not wash themselves until the mourning is over. These first clamours conclude by several good pots of masato, to assuage the thirst of sorrow, and the company next proceed to make a great clatter among the utensils of the deceased: some break the kettles, and others the earthen pots, while others, again, burn the apparel, to the end that his memory may be the sooner forgotten. If the defunct has been a cacique, or powerful warrior, his exequies are performed after the manner of the Romans : they last for many days, all the people weeping in concert for a considerable space of time, at daybreak, at noon, in the evening, and at midmght. When the appointed hour arrives, the mournful music begins in front of the house of the wife and relatives, the heroical deeds of the deceased being chanted to the sound of instruments. All the inhabitants of the vicinity unite in chorus from within their houses, some chirping like birds, others howling like tigers, and the greater part of them chattering like monkeys, or croaking like frogs. They constantly leave off by having recourse to the masato, and by the destruction of whatever the deceased may have left behind him, the burning of his dwelling being that which concludes the ceremonies. Among some of the Indians, the nearest relatives cut off their hair as a token of their grief, agreeably to the practice of the Moabites, and other nations. . . .

The Obsequies of a Chief

"On the day of decease, they put the body, with its insignia, into a large earthen vessel, or painted jar, which they bury in one of the angles of the quarter, laying over it a covering of potter's clay, and throwing in earth until the grave is on a level with the surface of the ground. When the obsequies are over, they forbear to pay a visit to it, and lose every recollection of the name of the warrior. The Roamaynas disenterre their dead, as soon as they think that the fleshy parts have been consumed, and having washed the bones form the skeleton, which they place in a coffin of potter's clay, adorned with various symbols of death, like the hieroglyphics on the wrappers of the Egyptian mummies. In this state the skeleton is carried home, to the end that the survivors may bear the deceased in respectful memory, and not in imitation of those extraordinary voluptuaries of antiquity, who introduced into their most splendid festivals a spectacle of this nature, which, by reminding them of their dissolution, might stimulate them to taste, before it should overtake them, all the impure pleasures the human passions could afford them. A space of time of about a year being elapsed, the bones are once more inhumed, and the individual to whom they belonged forgotten for ever."

Peru is not so rich in myths as Mexico, but the following legends well illustrate the mythological ideas of the Inca race:

The Inca Yupanqui before he succeeded to the sovereignty is said to have gone to visit his father, Viracocha Inca. On his way he arrived at a fountain called Susur-pugaio. There he saw a piece of crystal fall into the fountain, and in this crystal he saw the figure of an Indian, with three bright rays as of the sun coming from the back of his head. He wore a hauM, or royal fringe, across the forehead like the Inca. Serpents wound round his arms and over his shoulders. He had ear-pieces in his ears like the Incas, and was also dressed like them. There was the head of a lion between his legs, and another lion was about his shoulders. Inca Yupanqui took fright at this strange figure, and was running away when a voice called to him by name telling him not to be afraid, because it was his father, the sun, whom he beheld, and that he would conquer many nations, but he must remember his father in his sacrifices and raise revenues for him, and pay him great reverence. Then the figure vanished, but the crystal remained, and the Inca afterwards saw all he wished in it. When he became king he had a statue of the sun made, resembling the figure as closely as possible, and ordered all the tribes he had conquered to build splendid temples and worship the new deity instead of the creator.

The Bird Bride

" The birdlike beings were in reality women"

William Sewell

The Canaris Indians arc named from the province of Canaribamba, in Quito, and they have several myths regarding their origin. One recounts that at the deluge two brothers fled to a very high mountain called Huacaquan, and as the waters rose the hill ascended simultaneously, so that they escaped drowning. When the flood was over they had to find food in the valleys, and they built a tiny house and lived on herbs and roots. They were surprised one day when they went home to find food already prepared for them and chicha to drink. This continued for ten days. Then the elder brother decided to hide himself and discover who brought the food. Very soon two birds, one Aqua, the other Torito (otherwise quacamayo birds), appeared dressed as Canaris, and wearing their hair fastened in the same way. The larger bird removed the Hicella^ or mantle the Indians wear, and the man saw that they had beautiful faces and discovered that the bird-like beings were in reality women. When he came out the bird-women were very angry and flew away. When the younger brother came home and found no food he was annoyed, and determined to hide until the bird-women returned. After ten days the quacamayos appeared again on their old mission, and while they were busy the watcher contrived to close the door, and so prevented the younger bird from escaping. She lived with the brothers for a long time, and became the mother of six sons and daughters, from whom all the Canaris proceed. Hence the tribe look upon the quacamayo birds with reverence, and use their feathers at their festivals.

Thonapa

Some myths tell of a divine personage called Thonapa, who appears to have been a hero-god or civilising agent like Quetzalcoatl. He seems to have devoted his life to preaching to the people in the various villages, beginning in the provinces of Colla-suya. When he came to Yamquisupa he was treated so badly that he would not remain there. He slept in the open air, clad only in a long shirt and a mantle, and carried a book. He cursed the village. It was soon immersed in water, and is now a lake. There was an idol in the form of a woman to which the people offered sacrifice at the top of a high hill, Cachapucara. This idol Thonapa detested, so he burnt it, and also destroyed the hill. On another occasion Thonapa cursed a large assembly of people who were holding a great banquet to celebrate a wedding, because they refused to listen to his preaching. They were all changed into stones, which are visible to this day. Wandering through Peru, Thonapa came to the mountain of Caravaya, and after raising a very large cross he put it on his shoulders and took it to the hill Carapucu, where he preached so fervently that he shed tears. A chiefs daughter got some of the water on her head, and the Indians, imagining that he was washing his head (a ritual offence), took him prisoner near the Lake of Carapucu. Very early the next morning a beautiful youth appeared to Thonapa, and told him not to fear, for he was sent from the divine guardian who watched over him. He released Thonapa, who escaped, though he was well guarded. He went down into the lake, his mantle keeping him above the water as a boat would have done. After Thonapa had escaped from the* barbarians he remained on the rock of Titicaca, afterwards going to the town of Tiya-manacu, where again he cursed the people and turned them into stones. They were too bent upon amusement to listen to his preaching. He then followed the river Chacamarca till it reached the sea, and, like Quetzalcoatl, disappeared. This is good evidence that he was a solar deity, or "man of the sun," who, his civilising labours completed, betook himself to the house of his father.

A Myth of Manco Ccapac Inca

A beautiful youth appeared to Thonapa"

William Sewell

When Manco Ccapac Inca was born a staff which had been given to his father turned into gold. He had seven brothers and sisters, and at his father's death he assembled all his people in order to see how much he could venture in making fresh conquests. He and his brothers supplied themselves with rich clothing, new arms, and the golden staff called tapac-yauri (royal sceptre). He had also two cups of gold from which Thonapa had drunk, called tapacusi. They proceeded to the highest point in the country, a mountain where the sun rose, and Manco Ccapac saw several rainbows, which he interpreted as a sign of good fortune, Delighted with the favouring symbols, he sang the song of Chamayhuarisca (The Song of Joy). Manco Ccapac wondered why a brother who had accompanied him did not return, and sent one of his sisters in search of him, but she also did not come back, so he went himself, and found both nearly dead beside a huaca. They said they could not move, as the huaca y a stone, retarded them. In a great rage Manco struck this stone with his tapac-yauri. It spoke, and said that had it not been for his wonderful golden staff he would have had no power over it. It added that his brother and sister had sinned, and therefore must remain with it (the huaca} in the lower regions, but that Manco was to be "greatly honoured." The sad fate of his brother and sister troubled Manco exceedingly, but on going back to the place where he first saw the rainbows he got comfort from them and strength to bear his grief.

Coniraya Viracocha

Coniraya Viracocha was a tricky nature spirit who declared he was the creator, but who frequently appeared attired as a poor ragged Indian. He was an adept at deceiving people. A beautiful woman, Cavillaca, who was greatly admired, was one day weaving a mantle at the foot of a lucma tree. Coniraya, changing himself into a beautiful bird, climbed the tree, took some of his generative seed, made it into a ripe tucma, and dropped it near the beautiful virgin, who saw and ate the fruit. Some time afterwards a son was born to Cavillaca. When the child was older she wished that the huacas and gods should meet and declare who was the father of the boy. All dressed as finely as possible, hoping to be chosen as her husband. Coniraya was there, dressed like a beggar, and Cavillaca never even looked at him. The maiden addressed the assembly, but as no one immediately answered her speech she let the child go, saying he would be sure to crawl to his father. The infant went straight up to Coniraya, sitting in his rags, and laughed up to him. Cavillaca, extremely angry at the idea of being associated with such a poor, dirty creature, fled to the sea-shore. Coniraya then put on magnificent attire and followed her to show her how handsome he was, but still thinking of him in his ragged condition she would not look back. She went into the sea at Pachacamac and was changed into a rock.

" He sang the song of Chamayhuarisca

William Sewell

Coniraya, still following her, met a condor, and asked if it had seen a woman. On the condor replying that it had seen her quite near, Coniraya blessed it, and said whoever killed it would be killed himself. He then met a fox, who said he would never meet Cavillaca, so Coniraya told him he would always retain his disagreeable odour, and on account of it he would never be able to go abroad except at night, and that he would be hated by every one. Next came a lion, who told Coniraya he was very near Cavillaca, so the lover said he should have the power of punishing wrongdoers, and that whoever killed him would wear the skin without cutting of the head, and by preserving the teeth and eyes would make him appear still alive; his skin would be worn at festivals, and thus he would be honoured after death. Then another fox who gave bad news was cursed, and a falcon who said Cavillaca was near was told he would be highly esteemed, and that whoever killed him would also wear his skin at festivals. The parrots, giving bad news, were to cry so loud that they would be heard far away, and their cries would betray them to enemies. Thus Coniraya blessed the animals which gave him news he liked, and cursed those which gave the opposite. When at last he came to the sea he found Cavillaca and the child turned into stone, and there he encountered two beautiful young daughters of Pachacamac, who guarded a great serpent. He made love to the elder sister, but the younger one flew away in the form of a wild pigeon. At that time there were no fishes in the sea, but a certain goddess had reared a few in a small pond, and Coniraya emptied these into the ocean and thus peopled it. The angry deity tried to outwit Coniraya and kill him, but he was too wise and escaped. He returned to Huarochiri, and played tricks as before on the villagers.

Coniraya slightly approximates to the Jurupari of the Uapes Indians of Brazil, especially as regards his impish qualities.

The Llama's Warning

An old Peruvian myth relates how the world was nearly left without an inhabitant. A man took his llama to a fine place for feeding, but the beast moaned and would not eat, and on its master questioning it, it said there was little wonder it was sad, because in five days the sea would rise and engulf the earth. The man, alarmed, asked if there was no way of escape, and the llama advised him to go to the top of a high mountain, Villa-coto, taking food for five days. Where they reached the summit of the hill all kinds of birds and animals were already there. When the sea rose the water came so near that it washed the tail of a fox, and that is why foxes' tails are black! After five days the water fell, leaving only this one man alive, and from him the Peruvians believed the present human race to be descended.

The Myth of Huathiacuri

After the deluge the Indians chose the bravest and richest man as leader. This period they called Purunpacha (the time without a king). On a high mountain-top appeared five large eggs, from one of which Paricaca, father of Huathiacuri, later emerged. Huathiacuri, who was so poor that he had not means to cook his food properly, learned much wisdom from his father, and the following story shows how this assisted him. A certain man had built a most curious house, the roof being made of yellow and red birds' feathers. He was very rich, possessing many llamas, and was greatly esteemed on account of his wealth. So proud did he become that he aspired to be the creator himself; but when he became very ill and could not cure himself his divinity seemed doubtful.

"The younger one flew away"

William Sewell

Just at this time Huathiacuri was travelling about, and one day he saw two foxes meet and listened to their conversation. From this he heard about the rich man and learned the cause of his illness, and forthwith he determined to go on to find him. On arriving at the curious house he met a lovely young girl, one of the rich man's daughters. She told him about her father's illness, and Huathiacuri, charmed with her, said he would cure her father if she would only give him her love. He looked so ragged and dirty that she refused, but she took him to her father and informed him that Huathiacuri said he could cure him. Her father consented to give him an opportunity to do so. Huathiacuri began his cure by telling the sick man that his wife had been unfaithful, and that there were two serpents hovering above his house to devour it, and a toad with two heads under his grinding-stone. His wife at first indignantly denied the accusation, but on Huathiacuri reminding her of some details, and the serpents and toad being discovered, she confessed her guilt. The reptiles were killed, the man recovered, and the daughter was married to Huathiacuri.

Huathiacuri's poverty and raggedness displeased the girl's brother-in-law, who suggested to the bridegroom a contest in dancing and drinking. Huathiacuri went to seek his father's advice, and the old man told him to accept the challenge and return to him. Paricaca then sent him to a mountain, where he was changed into a dead llama. Next morning a fox and its vixen carrying a jar of chicha came, the fox having a flute of many pipes. When they saw the dead llama they laid down their things and went toward it to have a feast, but Huathiacuri then resumed his human form and gave a loud cry that frightened away the foxes, whereupon he took possession of the jar and flute. By the aid of these, which were magically endowed, he beat his brother-in-law in dancing and drinking.

Then the brother-in-law proposed a contest to prove who was the handsomer when dressed in festal attire. By the aid of Paricaca Huathiacuri found a red lion-skin, which gave him the appearance of having a rainbow round his head, and he again won.

The next trial was to see who could build a house the quickest and best. The brother-in-law got all his men to help, and had his house nearly finished before the other had his foundation laid. But here again Paricaca's wisdom proved of service, for Huathiacuri got animals and birds of all kinds to help him during the night, and by morning the building was finished except the roof. His brother-in-law got many llamas to come with straw for his roof, but Huathiacuri ordered an animal to stand where its loud screams frightened the llamas away, and the straw was lost. Once more Huathiacuri won the day. At last Paricaca advised Huathiacuri to end this conflict, and he asked his brother-in-law to see who could dance best in a blue shirt with white cotton round the loins. The rich man as usual appeared first, but when Huathiacuri came in he made a very loud noise and frightened him, and he began to run away. As he ran Huathiacuri turned him into a deer. His wife, who had followed him, was turned into a stone, with her head on the ground and her feet in the air, because she had given her husband such bad advice.

The four remaining eggs on the mountain-top then opened, and four falcons issued, which turned inta four great warriors. These warriors performed many miracles, one of which consisted in raising a storm which swept away the rich Indian's house in a flood to the sea.

Paricaca

Having assisted in the performance of several miracles, Paricaca set out determined to do great deeds. He went to find Caruyuchu Huayallo, to whom children were sacrificed. He came one day to a village where a festival was being celebrated, and as he was in very poor clothes no one took any notice of him or offered him anything, till a young girl, taking pity on him, brought him chicha to drink. In gratitude Paricaca told her to seek a place of safety for herself, as the village would be destroyed after five days, but she was to tell no one of this. Annoyed at the inhospitality of the people, Paricaca then went to a hill-top and sent down a fearful storm and flood, and the whole village was destroyed. Then he came to another village, now San Lorenzo.

" His wife at first indignantly denied the accusation

William Sewell

He saw a very beautiful girl, Choque Suso, crying bitterly. Asking her why she wept, she said the maize crop was dying for want of water. Paricaca at once fell in love with this girl, and after first damming up the little water there was, and thus leaving none for the crop, he told her he would give her plenty of water if she would only return his love. She said he must get water not only for her own crop but for all the other farms before she could consent. He noticed a small rill, from which, by opening a dam, he thought he might get a sufficient supply of water for the farms. He then got the assistance of the birds in the hills, and animals such as snakes, lizards, and so on, in removing any obstacles in the way, and they widened the channel so that the water irrigated all the land. The fox with his usual cunning managed to obtain the post of engineer, and carried the canal to near the site of the church of San Lorenzo. Paricaca, having accomplished what he had promised, begged Choque Suso to keep her word, which she willingly did, but she proposed living at the summit of some rocks called Yanacaca. There the lovers stayed very happily, at the head of the channel called Cocochallo, the making of which had united them ; and as Choque Suso wished to remain there always, Paricaca eventually turned her into a stone.

In all likelihood this myth was intended to account for the invention of irrigation among the early Peruvians, and from being a local legend probably spread over the length and breadth of the country.

Conclusion

The advance in civilisation attained by the peoples of America must be regarded as among the most striking phenomena in the history of mankind, especially if it be viewed as an example of what can be achieved by isolated races occupying a peculiar environment. It cannot be too strongly emphasised that the cultures and mythologies of old Mexico and Peru were evolved without foreign assistance or intervention, that, in fact, they were distinctively and solely the fruit of American aboriginal thought evolved upon American soil. An absorbing chapter in the story of human advancement is provided by these peoples, whose architecture, arts, graphic and plastic, laws and religions prove them to have been the equals of most of the Asiatic nations of antiquity, and the superiors of the primitive races of Europe, who entered into the heritage of civilisation through the gateway of the East. The aborigines of ancient America had evolved for themselves a system of writing which at the period of their discovery was approaching the alphabetic type, a mathematical system unique and by no means despicable, and an architectural science in some respects superior to any of which the Old World could boast. Their legal codes were reasonable and founded upon justice ; and if their religions were tainted with cruelty, it was a cruelty which they regarded as inevitable, and as the doom placed upon them by sanguinary and insatiable deities and not by any human agency.

"He saw a very beautiful girl crying bitterly"

William Sewell

In comparing the myths of the American races with the deathless stories of Olympus or the scarcely less classic tales of India, frequent resemblances and analogies cannot fail to present themselves, and these are of value as illustrating the circumstance that in every quarter of the globe the mind of man has shaped for itself a system of faith based upon similar principles. But in the perusal of the myths and beliefs of Mexico and Peru we are also struck with the strangeness and remoteness alike of their subject-matter and the type of thought which they present. The result of centuries of isolation is evident in a profound contrast of "atmosphere." It seems almost as if we stood for a space upon the dim shores of another planet, spectators of the doings of a race of whose modes of thought and feeling we were entirely ignorant.

For generations these stories have been hidden, along with the memory of the gods and folk of whom they tell, beneath a thick dust of neglect, displaced here and there only by the efforts of antiquarians working singly and unaided. Nowadays many well-equipped students are striving to add to our knowledge of the civilisations of Mexico and Peru. To the mythical stories of these peoples, alas! we cannot add. The greater part of them perished in the flames of the Spanish autos-de-fL But for those which have survived we must be grateful, as affording so many casements through which we may catch the glitter and gleam of civilisations more remote and bizarre than those of the Orient, shapes dim yet gigantic, misty yet many-coloured, the ghosts of peoples and beliefs not the least splendid and solemn in the roll of dead nations and vanished faiths.