[Transcriber's Note: Some of the plates are

displayed out of sequence to correspond with references to them

in the text.]

THOUGHT-FORMS

As knowledge increases, the attitude of science towards the

things of the invisible world is undergoing considerable

modification. Its attention is no longer directed solely to the

earth with all its variety of objects, or to the physical worlds

around it; but it finds itself compelled to glance further

afield, and to construct hypotheses as to the nature of the

matter and force which lie in the regions beyond the ken of its

instruments. Ether is now comfortably settled in the scientific

kingdom, becoming almost more than a hypothesis. Mesmerism, under

its new name of hypnotism, is no longer an outcast. Reichenbach's

experiments are still looked at askance, but are not wholly

condemned. Röntgen's rays have rearranged some of the older

ideas of matter, while radium has revolutionised them, and is

leading science beyond the borderland of ether into the astral

world. The boundaries between animate and inanimate matter are

broken down. Magnets are found to be possessed of almost uncanny

powers, transferring certain forms of disease in a way not yet

satisfactorily explained. Telepathy, clairvoyance, movement

without contact, though not yet admitted to the scientific table,

are approaching the Cinderella-stage. The fact is that science

has pressed its researches so far, has used such rare ingenuity

in its questionings of nature, has shown such tireless patience

in its investigations, that it is receiving the reward of those

who seek, and forces and beings of the next higher plane of

nature are beginning to show themselves on the outer edge of the

physical field. "Nature makes no leaps," and as the physicist

nears the confines of his kingdom he finds himself bewildered by

touches and gleams from another realm which interpenetrates his

own. He finds himself compelled to speculate on invisible

presences, if only to find a rational explanation for undoubted

physical phenomena, and insensibly he slips over the boundary,

and is, although he does not yet realise it, contacting the

astral plane.

One of the most interesting of the highroads from the physical

to the astral is that of the study of thought. The Western

scientist, commencing in the anatomy and physiology of the brain,

endeavours to make these the basis for "a sound psychology." He

passes then into the region of dreams, illusions, hallucinations;

and as soon as he endeavours to elaborate an experimental science

which shall classify and arrange these, he inevitably plunges

into the astral plane. Dr Baraduc of Paris has nearly crossed the

barrier, and is well on the way towards photographing

astro-mental images, to obtaining pictures of what from the

materialistic standpoint would be the results of vibrations in

the grey matter of the brain.

It has long been known to those who have given attention to

the question that impressions were produced by the reflection of

the ultra-violet rays from objects not visible by the rays of the

ordinary spectrum. Clairvoyants were occasionally justified by

the appearance on sensitive photographic plates of figures seen

and described by them as present with the sitter, though

invisible to physical sight. It is not possible for an unbiassed

judgment to reject in toto the evidence of such

occurrences proffered by men of integrity on the strength of

their own experiments, oftentimes repeated. And now we have

investigators who turn their attention to the obtaining of images

of subtle forms, inventing methods specially designed with the

view of reproducing them. Among these, Dr Baraduc seems to have

been the most successful, and he has published a volume dealing

with his investigations and containing reproductions of the

photographs he has obtained. Dr Baraduc states that he is

investigating the subtle forces by which the soul—defined

as the intelligence working between the body and the

spirit—expresses itself, by seeking to record its movements

by means of a needle, its "luminous" but invisible vibrations by

impressions on sensitive plates. He shuts out by non-conductors

electricity and heat. We can pass over his experiments in

Biometry (measurement of life by movements), and glance at those

in Iconography—the impressions of invisible waves, regarded

by him as of the nature of light, in which the soul draws its own

image. A number of these photographs represent etheric and

magnetic results of physical phenomena, and these again we may

pass over as not bearing on our special subject, interesting as

they are in themselves. Dr Baraduc obtained various impressions

by strongly thinking of an object, the effect produced by the

thought-form appearing on a sensitive plate; thus he tried to

project a portrait of a lady (then dead) whom he had known, and

produced an impression due to his thought of a drawing he had

made of her on her deathbed. He quite rightly says that the

creation of an object is the passing out of an image from the

mind and its subsequent materialisation, and he seeks the

chemical effect caused on silver salts by this thought-created

picture. One striking illustration is that of a force raying

outwards, the projection of an earnest prayer. Another prayer is

seen producing forms like the fronds of a fern, another like rain

pouring upwards, if the phrase may be permitted. A rippled oblong

mass is projected by three persons thinking of their unity in

affection. A young boy sorrowing over and caressing a dead bird

is surrounded by a flood of curved interwoven threads of

emotional disturbance. A strong vortex is formed by a feeling of

deep sadness. Looking at this most interesting and suggestive

series, it is clear that in these pictures that which is obtained

is not the thought-image, but the effect caused in etheric matter

by its vibrations, and it is necessary to clairvoyantly see the

thought in order to understand the results produced. In fact, the

illustrations are instructive for what they do not show directly,

as well as for the images that appear.

It may be useful to put before students, a little more plainly

than has hitherto been done, some of the facts in nature which

will render more intelligible the results at which Dr Baraduc is

arriving. Necessarily imperfect these must be, a physical

photographic camera and sensitive plates not being ideal

instruments for astral research; but, as will be seen from the

above, they are most interesting and valuable as forming a link

between clairvoyant and physical scientific investigations.

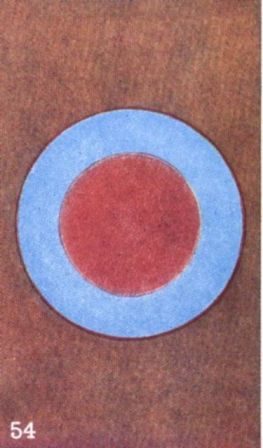

At the present time observers outside the Theosophical Society

are concerning themselves with the fact that emotional changes

show their nature by changes of colour in the cloud-like ovoid,

or aura, that encompasses all living beings. Articles on the

subject are appearing in papers unconnected with the Theosophical

Society, and a medical specialist[1] has collected a large number of cases in which

the colour of the aura of persons of various types and

temperaments is recorded by him. His results resemble closely

those arrived at by clairvoyant theosophists and others, and the

general unanimity on the subject is sufficient to establish the

fact, if the evidence be judged by the usual canons applied to

human testimony.

The book Man Visible and Invisible dealt with the

general subject of the aura. The present little volume, written

by the author of Man Visible and Invisible, and a

theosophical colleague, is intended to carry the subject further;

and it is believed that this study is useful, as impressing

vividly on the mind of the student the power and living nature of

thought and desire, and the influence exerted by them on all whom

they reach.

THE DIFFICULTY OF

REPRESENTATION

We have often heard it said that thoughts are things, and

there are many among us who are persuaded of the truth of this

statement. Yet very few of us have any clear idea as to what kind

of thing a thought is, and the object of this little book is to

help us to conceive this.

There are some serious difficulties in our way, for our

conception of space is limited to three dimensions, and when we

attempt to make a drawing we practically limit ourselves to two.

In reality the presentation even of ordinary three-dimensional

objects is seriously defective, for scarcely a line or angle in

our drawing is accurately shown. If a road crosses the picture,

the part in the foreground must be represented as enormously

wider than that in the background, although in reality the width

is unchanged. If a house is to be drawn, the right angles at its

corners must be shown as acute or obtuse as the case may be, but

hardly ever as they actually are. In fact, we draw everything not

as it is but as it appears, and the effort of the artist is by a

skilful arrangement of lines upon a flat surface to convey to the

eye an impression which shall recall that made by a

three-dimensional object.

It is possible to do this only because similar objects are

already familiar to those who look at the picture and accept the

suggestion which it conveys. A person who had never seen a tree

could form but little idea of one from even the most skilful

painting. If to this difficulty we add the other and far more

serious one of a limitation of consciousness, and suppose

ourselves to be showing the picture to a being who knew only two

dimensions, we see how utterly impossible it would be to convey

to him any adequate impression of such a landscape as we see.

Precisely this difficulty in its most aggravated form stands in

our way, when we try to make a drawing of even a very simple

thought-form. The vast majority of those who look at the picture

are absolutely limited to the consciousness of three dimensions,

and furthermore, have not the slightest conception of that inner

world to which thought-forms belong, with all its splendid light

and colour. All that we can do at the best is to represent a

section of the thought-form; and those whose faculties enable

them to see the original cannot but be disappointed with any

reproduction of it. Still, those who are at present unable to see

anything will gain at least a partial comprehension, and however

inadequate it may be it is at least better than nothing.

All students know that what is called the aura of man is the

outer part of the cloud-like substance of his higher bodies,

interpenetrating each other, and extending beyond the confines of

his physical body, the smallest of all. They know also that two

of these bodies, the mental and desire bodies, are those chiefly

concerned with the appearance of what are called thought-forms.

But in order that the matter may be made clear for all, and not

only for students already acquainted with theosophical teachings,

a recapitulation of the main facts will not be out of place.

Man, the Thinker, is clothed in a body composed of innumerable

combinations of the subtle matter of the mental plane, this body

being more or less refined in its constituents and organised more

or less fully for its functions, according to the stage of

intellectual development at which the man himself has arrived.

The mental body is an object of great beauty, the delicacy and

rapid motion of its particles giving it an aspect of living

iridescent light, and this beauty becomes an extraordinarily

radiant and entrancing loveliness as the intellect becomes more

highly evolved and is employed chiefly on pure and sublime

topics. Every thought gives rise to a set of correlated

vibrations in the matter of this body, accompanied with a

marvellous play of colour, like that in the spray of a waterfall

as the sunlight strikes it, raised to the nth degree of

colour and vivid delicacy. The body under this impulse throws off

a vibrating portion of itself, shaped by the nature of the

vibrations—as figures are made by sand on a disk vibrating

to a musical note—and this gathers from the surrounding

atmosphere matter like itself in fineness from the elemental

essence of the mental world. We have then a thought-form pure and

simple, and it is a living entity of intense activity animated by

the one idea that generated it. If made of the finer kinds of

matter, it will be of great power and energy, and may be used as

a most potent agent when directed by a strong and steady will.

Into the details of such use we will enter later.

When the man's energy flows outwards towards external objects

of desire, or is occupied in passional and emotional activities,

this energy works in a less subtle order of matter than the

mental, in that of the astral world. What is called his

desire-body is composed of this matter, and it forms the most

prominent part of the aura in the undeveloped man. Where the man

is of a gross type, the desire-body is of the denser matter of

the astral plane, and is dull in hue, browns and dirty greens and

reds playing a great part in it. Through this will flash various

characteristic colours, as his passions are excited. A man of a

higher type has his desire-body composed of the finer qualities

of astral matter, with the colours, rippling over and flashing

through it, fine and clear in hue. While less delicate and less

radiant than the mental body, it forms a beautiful object, and as

selfishness is eliminated all the duller and heavier shades

disappear.

This desire (or astral) body gives rise to a second class of

entities, similar in their general constitution to the

thought-forms already described, but limited to the astral plane,

and generated by the mind under the dominion of the animal

nature.

These are caused by the activity of the lower mind, throwing

itself out through the astral body—the activity of

Kâma-Manas in theosophical terminology, or the mind

dominated by desire. Vibrations in the body of desire, or astral

body, are in this case set up, and under these this body throws

off a vibrating portion of itself, shaped, as in the previous

case, by the nature of the vibrations, and this attracts to

itself some of the appropriate elemental essence of the astral

world. Such a thought-form has for its body this elemental

essence, and for its animating soul the desire or passion which

threw it forth; according to the amount of mental energy combined

with this desire or passion will be the force of the

thought-form. These, like those belonging to the mental plane,

are called artificial elementals, and they are by far the most

common, as few thoughts of ordinary men and women are untinged

with desire, passion, or emotion.

THE TWO EFFECTS OF THOUGHT

Each definite thought produces a double effect—a

radiating vibration and a floating form. The thought itself

appears first to clairvoyant sight as a vibration in the mental

body, and this may be either simple or complex. If the thought

itself is absolutely simple, there is only the one rate of

vibration, and only one type of mental matter will be strongly

affected. The mental body is composed of matter of several

degrees of density, which we commonly arrange in classes

according to the sub-planes. Of each of these we have many

sub-divisions, and if we typify these by drawing horizontal lines

to indicate the different degrees of density, there is another

arrangement which we might symbolise by drawing perpendicular

lines at right angles to the others, to denote types which differ

in quality as well as in density. There are thus many varieties

of this mental matter, and it is found that each one of these has

its own especial and appropriate rate of vibration, to which it

seems most accustomed, so that it very readily responds to it,

and tends to return to it as soon as possible when it has been

forced away from it by some strong rush of thought or feeling.

When a sudden wave of some emotion sweeps over a man, for

example, his astral body is thrown into violent agitation, and

its original colours are or the time almost obscured by the flush

of carmine, of blue, or of scarlet which corresponds with the

rate of vibration of that particular emotion. This change is only

temporary; it passes off in a few seconds, and the astral body

rapidly resumes its usual condition. Yet every such rush of

feeling produces a permanent effect: it always adds a little of

its hue to the normal colouring of the astral body, so that every

time that the man yields himself to a certain emotion it becomes

easier for him to yield himself to it again, because his astral

body is getting into the habit of vibrating at that especial

rate.

The majority of human thoughts, however, are by no means

simple. Absolutely pure affection of course exists; but we very

often find it tinged with pride or with selfishness, with

jealousy or with animal passion. This means that at least two

separate vibrations appear both in the mental and astral

bodies—frequently more than two. The radiating vibration,

therefore, will be a complex one, and the resultant thought-form

will show several colours instead of only one.

HOW THE VIBRATION ACTS

These radiating vibrations, like all others in nature, become

less powerful in proportion to the distance from their source,

though it is probable that the variation is in proportion to the

cube of the distance instead of to the square, because of the

additional dimension involved. Again, like all other vibrations,

these tend to reproduce themselves whenever opportunity is

offered to them; and so whenever they strike upon another mental

body they tend to provoke in it their own rate of motion. That

is—from the point of view of the man whose mental body is

touched by these waves—they tend to produce in his mind

thoughts of the same type as that which had previously arisen in

the mind of the thinker who sent forth the waves. The distance to

which such thought-waves penetrate, and the force and persistency

with which they impinge upon the mental bodies of others, depend

upon the strength and clearness of the original thought. In this

way the thinker is in the same position as the speaker. The voice

of the latter sets in motion waves of sound in the air which

radiate from him in all directions, and convey his message to all

those who are within hearing, and the distance to which his voice

can penetrate depends upon its power and upon the clearness of

his enunciation. In just the same way the forceful thought will

carry very much further than the weak and undecided thought; but

clearness and definiteness are of even greater importance than

strength. Again, just as the speaker's voice may fall upon

heedless ears where men are already engaged in business or in

pleasure, so may a mighty wave of thought sweep past without

affecting the mind of the man, if he be already deeply engrossed

in some other line of thought.

It should be understood that this radiating vibration conveys

the character of the thought, but not its subject. If a Hindu

sits rapt in devotion to Kṛiṣhṇa, the waves of

feeling which pour forth from him stimulate devotional feeling in

all those who come under their influence, though in the case of

the Muhammadan that devotion is to Allah, while for the

Zoroastrian it is to Ahuramazda, or for the Christian to Jesus. A

man thinking keenly upon some high subject pours out from himself

vibrations which tend to stir up thought at a similar level in

others, but they in no way suggest to those others the special

subject of his thought. They naturally act with special vigour

upon those minds already habituated to vibrations of similar

character; yet they have some effect on every mental body upon

which they impinge, so that their tendency is to awaken the power

of higher thought in those to whom it has not yet become a

custom. It is thus evident that every man who thinks along high

lines is doing missionary work, even though he may be entirely

unconscious of it.

THE FORM AND ITS EFFECT

Let us turn now to the second effect of thought, the creation

of a definite form. All students of the occult are acquainted

with the idea of the elemental essence, that strange

half-intelligent life which surrounds us in all directions,

vivifying the matter of the mental and astral planes. This matter

thus animated responds very readily to the influence of human

thought, and every impulse sent out, either from the mental body

or from the astral body of man, immediately clothes itself in a

temporary vehicle of this vitalised matter. Such a thought or

impulse becomes for the time a kind of living creature, the

thought-force being the soul, and the vivified matter the body.

Instead of using the somewhat clumsy paraphrase, "astral or

mental matter ensouled by the monadic essence at the stage of one

of the elemental kingdoms," theosophical writers often, for

brevity's sake, call this quickened matter simply elemental

essence; and sometimes they speak of the thought-form as "an

elemental." There may be infinite variety in the colour and shape

of such elementals or thought-forms, for each thought draws round

it the matter which is appropriate for its expression, and sets

that matter into vibration in harmony with its own; so that the

character of the thought decides its colour, and the study of its

variations and combinations is an exceedingly interesting

one.

This thought-form may not inaptly be compared to a Leyden jar,

the coating of living essence being symbolised by the jar, and

the thought energy by the charge of electricity. If the man's

thought or feeling is directly connected with someone else, the

resultant thought-form moves towards that person and discharges

itself upon his astral and mental bodies. If the man's thought is

about himself, or is based upon a personal feeling, as the vast

majority of thoughts are, it hovers round its creator and is

always ready to react upon him whenever he is for a moment in a

passive condition. For example, a man who yields himself to

thoughts of impurity may forget all about them while he is

engaged in the daily routine of his business, even though the

resultant forms are hanging round him in a heavy cloud, because

his attention is otherwise directed and his astral body is

therefore not impressible by any other rate of vibration than its

own. When, however, the marked vibration slackens and the man

rests after his labours and leaves his mind blank as regards

definite thought, he is very likely to feel the vibration of

impurity stealing insidiously upon him. If the consciousness of

the man be to any extent awakened, he may perceive this and cry

out that he is being tempted by the devil; yet the truth is that

the temptation is from without only in appearance, since it is

nothing but the natural reaction upon him of his own

thought-forms. Each man travels through space enclosed within a

cage of his own building, surrounded by a mass of the forms

created by his habitual thoughts. Through this medium he looks

out upon the world, and naturally he sees everything tinged with

its predominant colours, and all rates of vibration which reach

him from without are more or less modified by its rate. Thus

until the man learns complete control of thought and feeling, he

sees nothing as it really is, since all his observations must be

made through this medium, which distorts and colours everything

like badly-made glass.

If the thought-form be neither definitely personal nor

specially aimed at someone else, it simply floats detached in the

atmosphere, all the time radiating vibrations similar to those

originally sent forth by its creator. If it does not come into

contact with any other mental body, this radiation gradually

exhausts its store of energy, and in that case the form falls to

pieces; but if it succeeds in awakening sympathetic vibration in

any mental body near at hand, an attraction is set up, and the

thought-form is usually absorbed by that mental body. Thus we see

that the influence of the thought-form is by no means so

far-reaching as that of the original vibration; but in so far as

it acts, it acts with much greater precision. What it produces in

the mind-body which it influences is not merely a thought of an

order similar to that which gave it birth; it is actually the

same thought. The radiation may affect thousands and stir up in

them thoughts on the same level as the original, and yet it may

happen that no one of them will be identical with that original;

the thought-form can affect only very few, but in those few cases

it will reproduce exactly the initiatory idea.

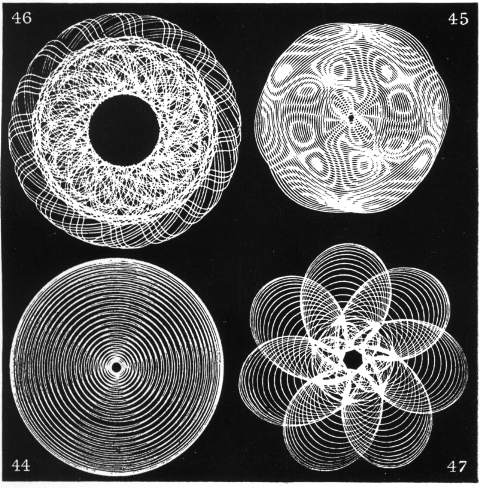

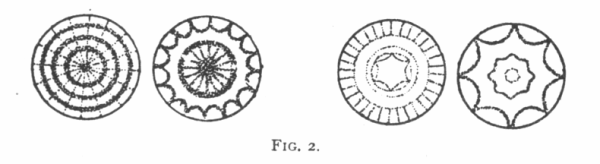

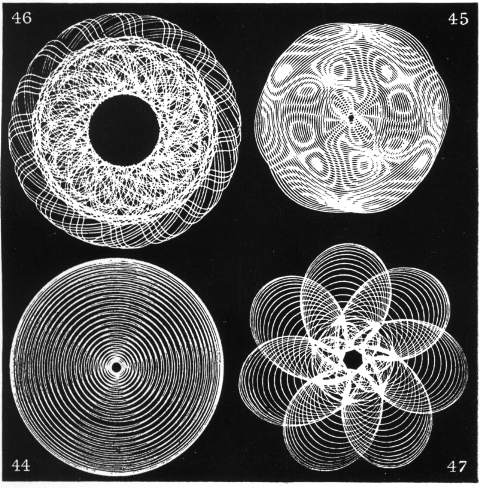

The fact of the creation by vibrations of a distinct form,

geometrical or other, is already familiar to every student of

acoustics, and "Chladni's" figures are continually reproduced in

every physical laboratory.

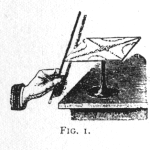

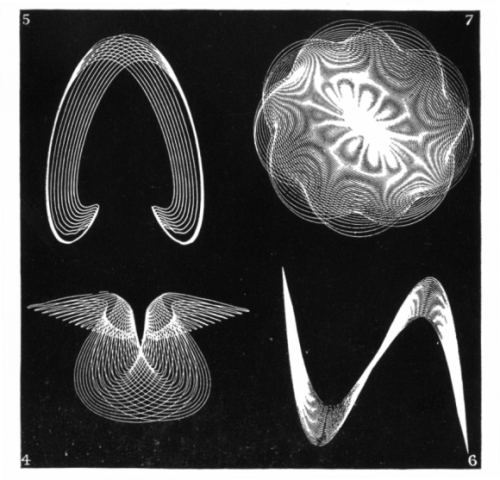

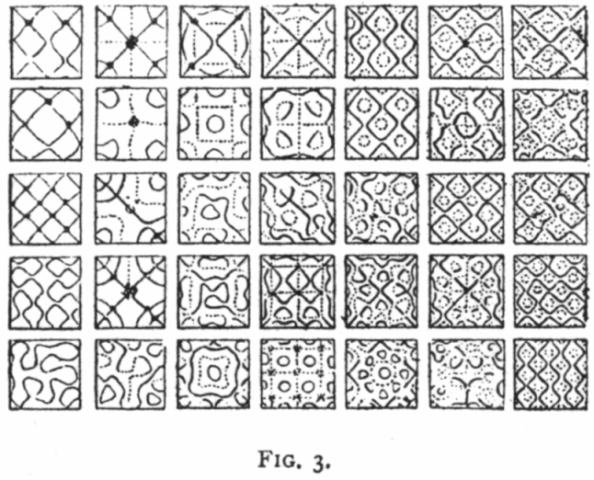

FIG. 1. CHLADNI'S SOUND PLATE

FIG. 1. CHLADNI'S SOUND PLATE

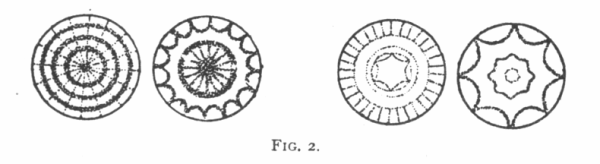

FIG. 2. FORMS PRODUCED IN

SOUND

FIG. 2. FORMS PRODUCED IN

SOUND

For the lay reader the following brief description may be

useful. A Chladni's sound plate (fig. 1) is made of brass or

plate-glass. Grains of fine sand or spores are scattered over the

surface, and the edge of the plate is bowed. The sand is thrown

up into the air by the vibration of the plate, and re-falling on

the plate is arranged in regular lines (fig. 2). By touching the

edge of the plate at different points when it is bowed, different

notes, and hence varying forms, are obtained (fig. 3). If the

figures here given are compared with those obtained from the

human voice, many likenesses will be observed. For these latter,

the 'voice-forms' so admirably studied and pictured by Mrs Watts

Hughes,[1] bearing witness to the

same fact, should be consulted, and her work on the subject

should be in the hands of every student. But few perhaps have

realised that the shapes pictured are due to the interplay of the

vibrations that create them, and that a machine exists by means

of which two or more simultaneous motions can be imparted to a

pendulum, and that by attaching a fine drawing-pen to a lever

connected with the pendulum its action may be exactly traced.

Substitute for the swing of the pendulum the vibrations set up in

the mental or astral body, and we have clearly before us the

modus operandi of the building of forms by

vibrations.[2]

FIG. 3. FORMS PRODUCED IN

SOUND

FIG. 3. FORMS PRODUCED IN

SOUND

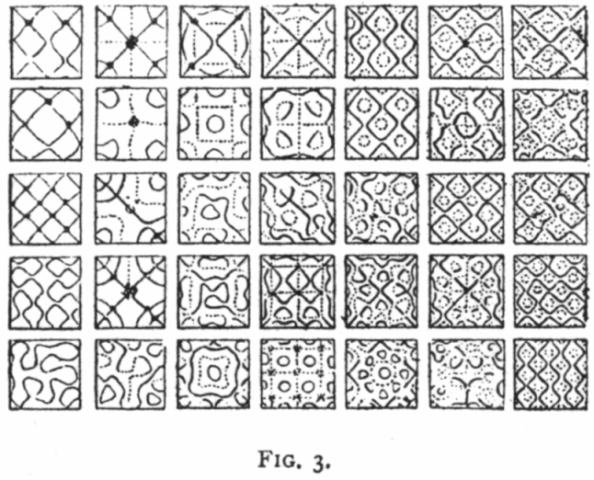

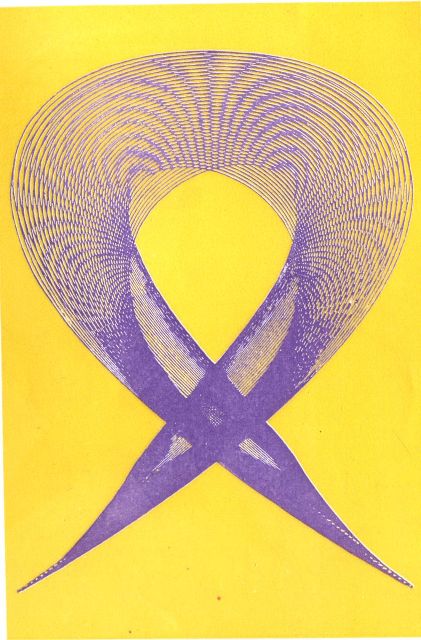

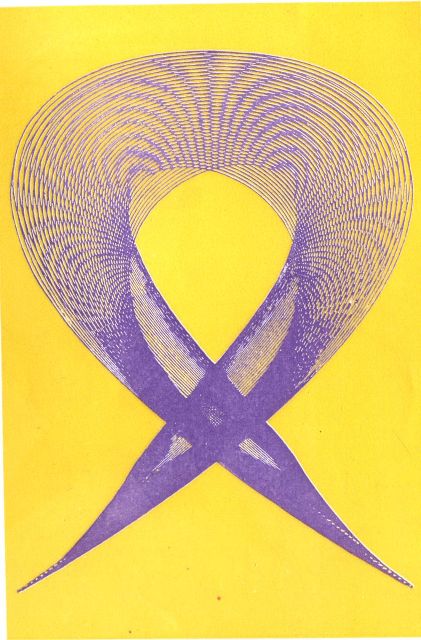

The following description is taken from a most interesting

essay entitled Vibration Figures, by F. Bligh Bond,

F.R.I.B.A., who has drawn a number of remarkable figures by the

use of pendulums. The pendulum is suspended on knife edges of

hardened steel, and is free to swing only at right angles to the

knife-edge suspension. Four such pendulums may be coupled in

pairs, swinging at right angles to each other, by threads

connecting the shafts of each pair of pendulums with the ends of

a light but rigid lath, from the centre of which run other

threads; these threads carry the united movements of each pair of

pendulums to a light square of wood, suspended by a spring, and

bearing a pen. The pen is thus controlled by the combined

movement of the four pendulums, and this movement is registered

on a drawing board by the pen. There is no limit, theoretically,

to the number of pendulums that can be combined in this manner.

The movements are rectilinear, but two rectilinear vibrations of

equal amplitude acting at right angles to each other generate a

circle if they alternate precisely, an ellipse if the

alternations are less regular or the amplitudes unequal. A cyclic

vibration may also be obtained from a pendulum free to swing in a

rotary path. In these ways a most wonderful series of drawings

have been obtained, and the similarity of these to some of the

thought-forms is remarkable; they suffice to demonstrate how

readily vibrations may be transformed into figures. Thus compare

fig. 4 with fig. 12, the mother's prayer; or fig. 5 with fig. 10;

or fig. 6 with fig. 25, the serpent-like darting forms. Fig. 7 is

added as an illustration of the complexity attainable. It seems

to us a most marvellous thing that some of the drawings, made

apparently at random by the use of this machine, should exactly

correspond to higher types of thought-forms created in

meditation. We are sure that a wealth of significance lies behind

this fact, though it will need much further investigation before

we can say certainly all that it means. But it must surely imply

this much—that, if two forces on the physical plane bearing

a certain ratio one to the other can draw a form which exactly

corresponds to that produced on the mental plane by a complex

thought, we may infer that that thought sets in motion on its own

plane two forces which are in the same ratio one to the other.

What these forces are and how they work remains to be seen; but

if we are ever able to solve this problem, it is likely that it

will open to us a new and exceedingly valuable field of

knowledge.

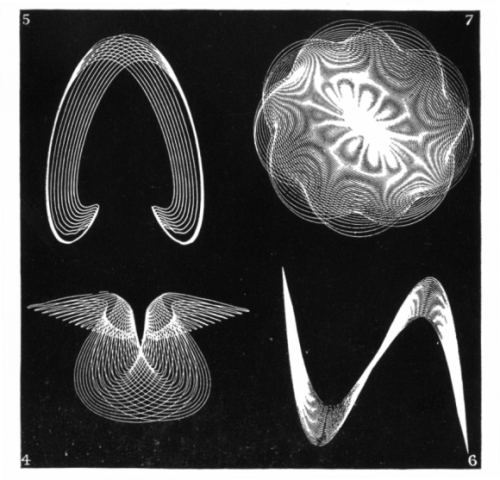

FIGS. 4-7. FORMS PRODUCED BY

PENDULUMS

FIGS. 4-7. FORMS PRODUCED BY

PENDULUMS

General Principles.

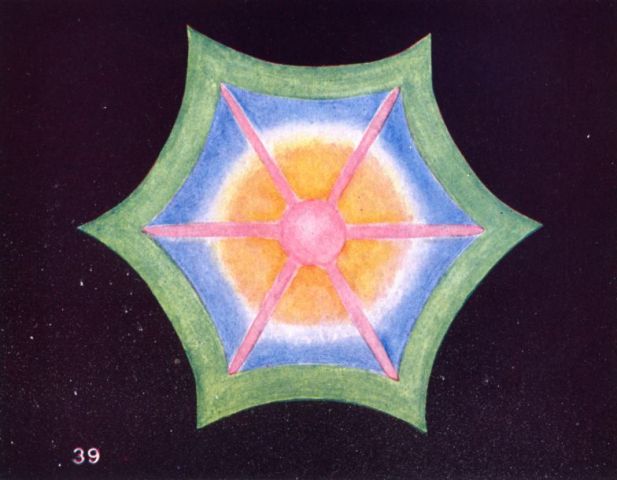

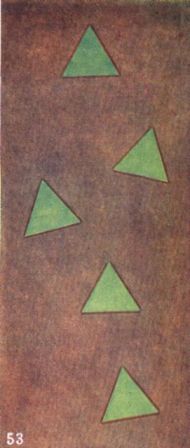

Three general principles underlie the production of all

thought-forms:—

- Quality of thought determines colour.

- Nature of thought determines form.

- Definiteness of thought determines clearness of outline.

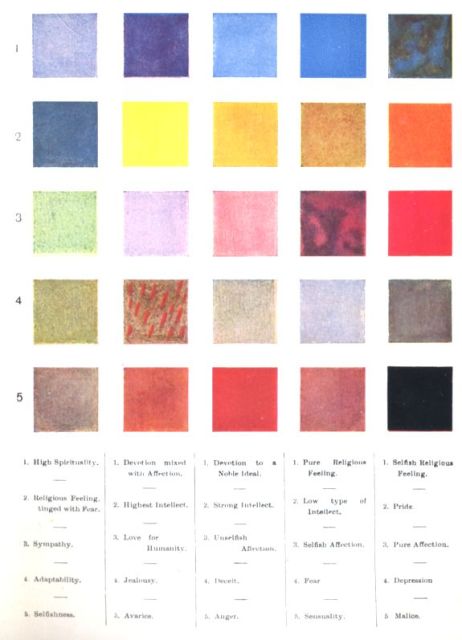

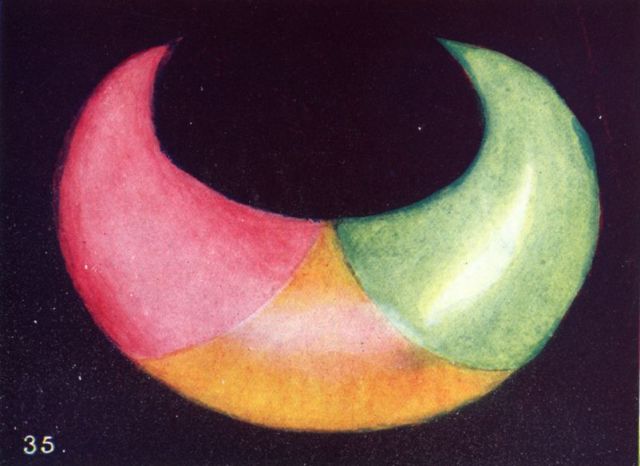

THE MEANING OF THE COLOURS

The table of colours given in the frontispiece has already

been thoroughly described in the book Man Visible and

Invisible, and the meaning to be attached to them is just the

same in the thought-form as in the body out of which it is

evolved. For the sake of those who have not at hand the full

description given in the book just mentioned, it will be well to

state that black means hatred and malice. Red, of all shades from

lurid brick-red to brilliant scarlet, indicates anger; brutal

anger will show as flashes of lurid red from dark brown clouds,

while the anger of "noble indignation" is a vivid scarlet, by no

means unbeautiful, though it gives an unpleasant thrill; a

particularly dark and unpleasant red, almost exactly the colour

called dragon's blood, shows animal passion and sensual desire of

various kinds. Clear brown (almost burnt sienna) shows avarice;

hard dull brown-grey is a sign of selfishness—a colour

which is indeed painfully common; deep heavy grey signifies

depression, while a livid pale grey is associated with fear;

grey-green is a signal of deceit, while brownish-green (usually

flecked with points and flashes of scarlet) betokens jealousy.

Green seems always to denote adaptability; in the lowest case,

when mingled with selfishness, this adaptability becomes deceit;

at a later stage, when the colour becomes purer, it means rather

the wish to be all things to all men, even though it may be

chiefly for the sake of becoming popular and bearing a good

reputation with them; in its still higher, more delicate and more

luminous aspect, it shows the divine power of sympathy. Affection

expresses itself in all shades of crimson and rose; a full clear

carmine means a strong healthy affection of normal type; if

stained heavily with brown-grey, a selfish and grasping feeling

is indicated, while pure pale rose marks that absolutely

unselfish love which is possible only to high natures; it passes

from the dull crimson of animal love to the most exquisite shades

of delicate rose, like the early flushes of the dawning, as the

love becomes purified from all selfish elements, and flows out in

wider and wider circles of generous impersonal tenderness and

compassion to all who are in need. With a touch of the blue of

devotion in it, this may express a strong realisation of the

universal brotherhood of humanity. Deep orange imports pride or

ambition, and the various shades of yellow denote intellect or

intellectual gratification, dull yellow ochre implying the

direction of such faculty to selfish purposes, while clear

gamboge shows a distinctly higher type, and pale luminous

primrose yellow is a sign of the highest and most unselfish use

of intellectual power, the pure reason directed to spiritual

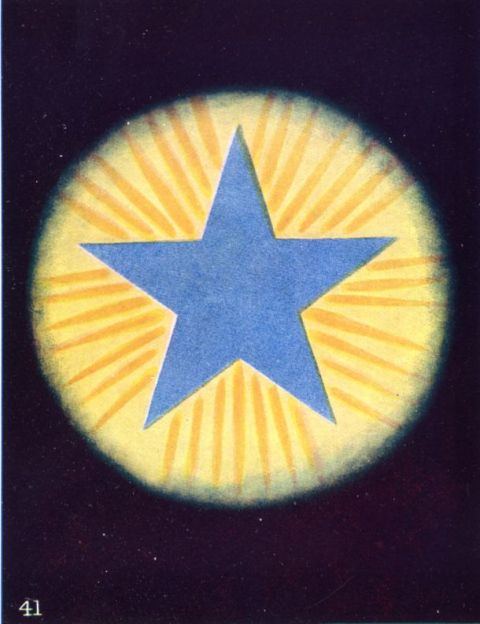

ends. The different shades of blue all indicate religious

feeling, and range through all hues from the dark brown-blue of

selfish devotion, or the pallid grey-blue of fetish-worship

tinged with fear, up to the rich deep clear colour of heartfelt

adoration, and the beautiful pale azure of that highest form

which implies self-renunciation and union with the divine; the

devotional thought of an unselfish heart is very lovely in

colour, like the deep blue of a summer sky. Through such clouds

of blue will often shine out golden stars of great brilliancy,

darting upwards like a shower of sparks. A mixture of affection

and devotion is manifested by a tint of violet, and the more

delicate shades of this invariably show the capacity of absorbing

and responding to a high and beautiful ideal. The brilliancy and

the depth of the colours are usually a measure of the strength

and the activity of the feeling.

Another consideration which must not be forgotten is the type

of matter in which these forms are generated. If a thought be

purely intellectual and impersonal—for example, if the

thinker is attempting to solve a problem in algebra or

geometry—the thought-form and the wave of vibration will be

confined entirely to the mental plane. If, however, the thought

be of a spiritual nature, if it be tinged with love and

aspiration or deep unselfish feeling, it will rise upwards from

the mental plane and will borrow much of the splendour and glory

of the buddhic level. In such a case its influence is exceedingly

powerful, and every such thought is a mighty force for good which

cannot but produce a decided effect upon all mental bodies within

reach, if they contain any quality at all capable of

response.

If, on the other hand, the thought has in it something of self

or of personal desire, at once its vibration turns downwards, and

it draws round itself a body of astral matter in addition to its

clothing of mental matter. Such a thought-form is capable of

acting upon the astral bodies of other men as well as their

minds, so that it can not only raise thought within them, but can

also stir up their feelings.

THREE CLASSES OF

THOUGHT-FORMS

From the point of view of the forms which they produce we may

group thought into three classes:—

1. That which takes the image of the thinker. When a man

thinks of himself as in some distant place, or wishes earnestly

to be in that place, he makes a thought-form in his own image

which appears there. Such a form has not infrequently been seen

by others, and has sometimes been taken for the astral body or

apparition of the man himself. In such a case, either the seer

must have enough of clairvoyance for the time to be able to

observe that astral shape, or the thought-form must have

sufficient strength to materialise itself—that is, to draw

round itself temporarily a certain amount of physical matter. The

thought which generates such a form as this must necessarily be a

strong one, and it therefore employs a larger proportion of the

matter of the mental body, so that though the form is small and

compressed when it leaves the thinker, it draws round it a

considerable amount of astral matter, and usually expands to

life-size before it appears at its destination.

2. That which takes the image of some material object. When a

man thinks of his friend he forms within his mental body a minute

image of that friend, which often passes outward and usually

floats suspended in the air before him. In the same way if he

thinks of a room, a house, a landscape, tiny images of these

things are formed within the mental body and afterwards

externalised. This is equally true when he is exercising his

imagination; the painter who forms a conception of his future

picture builds it up out of the matter of his mental body, and

then projects it into space in front of him, keeps it before his

mind's eye, and copies it. The novelist in the same way builds

images of his character in mental matter, and by the exercise of

his will moves these puppets from one position or grouping to

another, so that the plot of his story is literally acted out

before him. With our curiously inverted conceptions of reality it

is hard for us to understand that these mental images actually

exist, and are so entirely objective that they may readily be

seen by the clairvoyant, and can even be rearranged by some one

other than their creator. Some novelists have been dimly aware of

such a process, and have testified that their characters when

once created developed a will of their own, and insisted on

carrying the plot of the story along lines quite different from

those originally intended by the author. This has actually

happened, sometimes because the thought-forms were ensouled by

playful nature-spirits, or more often because some 'dead'

novelist, watching on the astral plane the development of the

plan of his fellow-author, thought that he could improve upon it,

and chose this method of putting forward his suggestions.

3. That which takes a form entirely its own, expressing its

inherent qualities in the matter which it draws round it. Only

thought-forms of this third class can usefully be illustrated,

for to represent those of the first or second class would be

merely to draw portraits or landscapes. In those types we have

the plastic mental or astral matter moulded in imitation of forms

belonging to the physical plane; in this third group we have a

glimpse of the forms natural to the astral or mental planes. Yet

this very fact, which makes them so interesting, places an

insuperable barrier in the way of their accurate

reproduction.

Thought-forms of this third class almost invariably manifest

themselves upon the astral plane, as the vast majority of them

are expressions of feeling as well as of thought. Those of which

we here give specimens are almost wholly of that class, except

that we take a few examples of the beautiful thought-forms

created in definite meditation by those who, through long

practice, have learnt how to think.

Thought-forms directed towards individuals produce definitely

marked effects, these effects being either partially reproduced

in the aura of the recipient and so increasing the total result,

or repelled from it. A thought of love and of desire to protect,

directed strongly towards some beloved object, creates a form

which goes to the person thought of, and remains in his aura as a

shielding and protecting agent; it will seek all opportunities to

serve, and all opportunities to defend, not by a conscious and

deliberate action, but by a blind following out of the impulse

impressed upon it, and it will strengthen friendly forces that

impinge on the aura and weaken unfriendly ones. Thus may we

create and maintain veritable guardian angels round those we

love, and many a mother's prayer for a distant child thus circles

round him, though she knows not the method by which her "prayer

is answered."

In cases in which good or evil thoughts are projected at

individuals, those thoughts, if they are to directly fulfil their

mission, must find, in the aura of the object to whom they are

sent, materials capable of responding sympathetically to their

vibrations. Any combination of matter can only vibrate within

certain definite limits, and if the thought-form be outside all

the limits within which the aura is capable of vibrating, it

cannot affect that aura at all. It consequently rebounds from it,

and that with a force proportionate to the energy with which it

impinged upon it. This is why it is said that a pure heart and

mind are the best protectors against any inimical assaults, for

such a pure heart and mind will construct an astral and a mental

body of fine and subtle materials, and these bodies cannot

respond to vibrations that demand coarse and dense matter. If an

evil thought, projected with malefic intent, strikes such a body,

it can only rebound from it, and it is flung back with all its

own energy; it then flies backward along the magnetic line of

least resistance, that which it has just traversed, and strikes

its projector; he, having matter in his astral and mental bodies

similar to that of the thought-form he generated, is thrown into

respondent vibrations, and suffers the destructive effects he had

intended to cause to another. Thus "curses [and blessings] come

home to roost." From this arise also the very serious effects of

hating or suspecting a good and highly-advanced man; the

thought-forms sent against him cannot injure him, and they

rebound against their projectors, shattering them mentally,

morally, or physically. Several such instances are well known to

members of the Theosophical Society, having come under their

direct observation. So long as any of the coarser kinds of matter

connected with evil and selfish thoughts remain in a person's

body, he is open to attack from those who wish him evil, but when

he has perfectly eliminated these by self-purification his haters

cannot injure him, and he goes on calmly and peacefully amid all

the darts of their malice. But it is bad for those who shoot out

such darts.

Another point that should be mentioned before passing to the

consideration of our illustrations is that every one of the

thought-forms here given is drawn from life. They are not

imaginary forms, prepared as some dreamer thinks that they ought

to appear; they are representations of forms actually observed as

thrown off by ordinary men and women, and either reproduced with

all possible care and fidelity by those who have seen them, or

with the help of artists to whom the seers have described

them.

For convenience of comparison thought-forms of a similar kind

are grouped together.

ILLUSTRATIVE THOUGHT-FORMS

AFFECTION

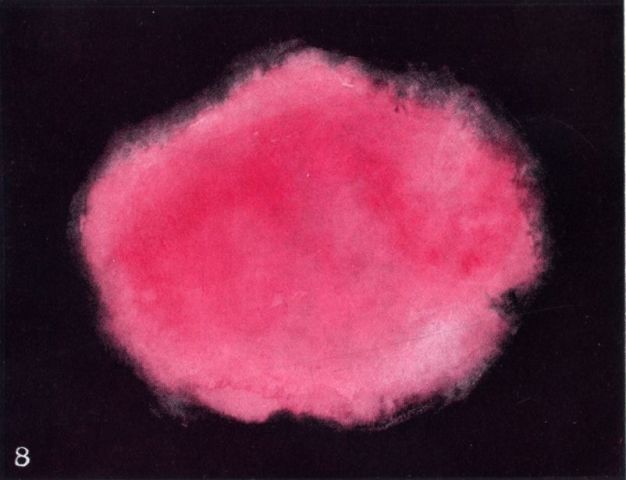

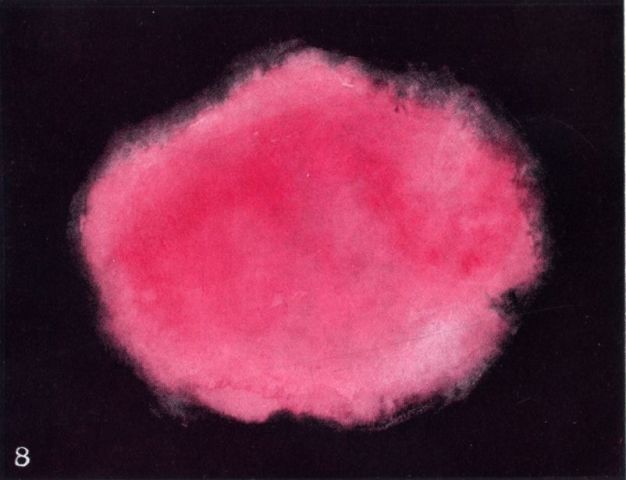

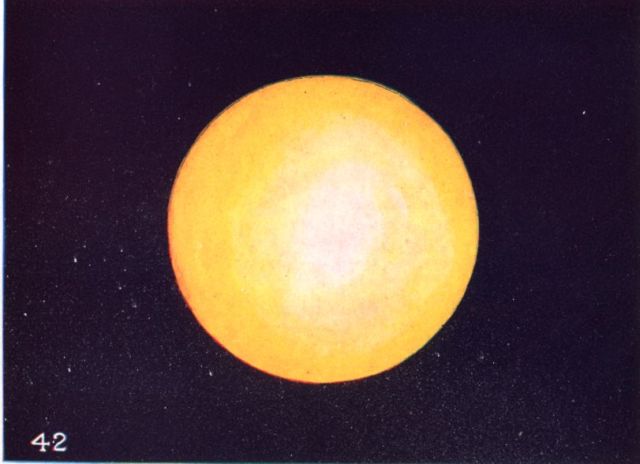

Vague Pure Affection.—Fig. 8 is a revolving cloud

of pure affection, and except for its vagueness it represents a

very good feeling. The person from whom it emanates is happy and

at peace with the world, thinking dreamily of some friend whose

very presence is a pleasure. There is nothing keen or strong

about the feeling, yet it is one of gentle well-being, and of an

unselfish delight in the proximity of those who are beloved. The

feeling which gives birth to such a cloud is pure of its kind,

but there is in it no force capable of producing definite

results. An appearance by no means unlike this frequently

surrounds a gently purring cat, and radiates slowly outward from

the animal in a series of gradually enlarging concentric shells

of rosy cloud, fading into invisibility at a distance of a few

feet from their drowsily contented creator.

FIG. 8. VAGUE PURE AFFECTION

FIG. 8. VAGUE PURE AFFECTION

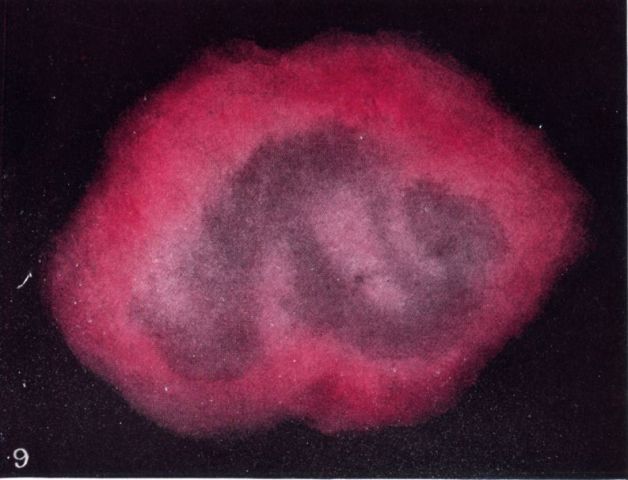

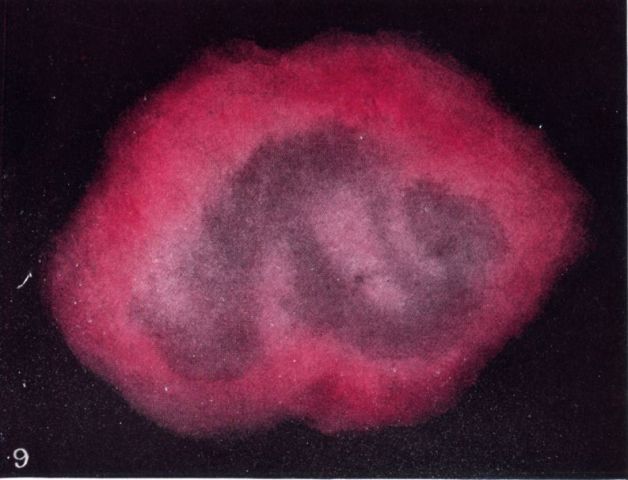

Vague Selfish Affection.—Fig. 9 shows us also a

cloud of affection, but this time it is deeply tinged with a far

less desirable feeling. The dull hard brown-grey of selfishness

shows itself very decidedly among the carmine of love, and thus

we see that the affection which is indicated is closely connected

with satisfaction at favours already received, and with a lively

anticipation of others to come in the near future. Indefinite as

was the feeling which produced the cloud in Fig. 8, it was at

least free from this taint of selfishness, and it therefore

showed a certain nobility of nature in its author. Fig. 9

represents what takes the place of that condition of mind at a

lower level of evolution. It would scarcely be possible that

these two clouds should emanate from the same person in the same

incarnation. Yet there is good in the man who generates this

second cloud, though as yet it is but partially evolved. A vast

amount of the average affection of the world is of this type, and

it is only by slow degrees that it develops towards the other and

higher manifestation.

FIG. 9. VAGUE SELFISH

AFFECTION

FIG. 9. VAGUE SELFISH

AFFECTION

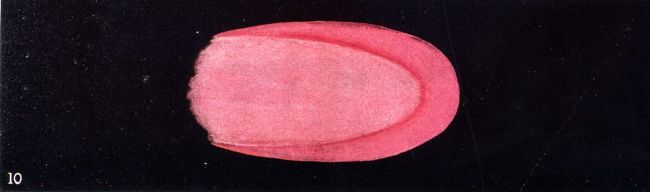

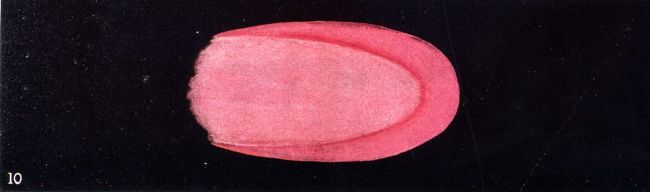

Definite Affection.—Even the first glance at Fig.

10 shows us that here we have to deal with something of an

entirely different nature—something effective and capable,

something that will achieve a result. The colour is fully equal

to that of Fig. 8 in clearness and depth and transparency, but

what was there a mere sentiment is in this case translated into

emphatic intention coupled with unhesitating action. Those who

have seen the book Man Visible and Invisible will

recollect that in Plate XI. of that volume is depicted the effect

of a sudden rush of pure unselfish affection as it showed itself

in the astral body of a mother, as she caught up her little child

and covered it with kisses. Various changes resulted from that

sudden outburst of emotion; one of them was the formation within

the astral body of large crimson coils or vortices lined with

living light. Each of these is a thought-form of intense

affection generated as we have described, and almost

instantaneously ejected towards the object of the feeling. Fig.

10 depicts just such a thought-form after it has left the astral

body of its author, and is on its way towards its goal. It will

be observed that the almost circular form has changed into one

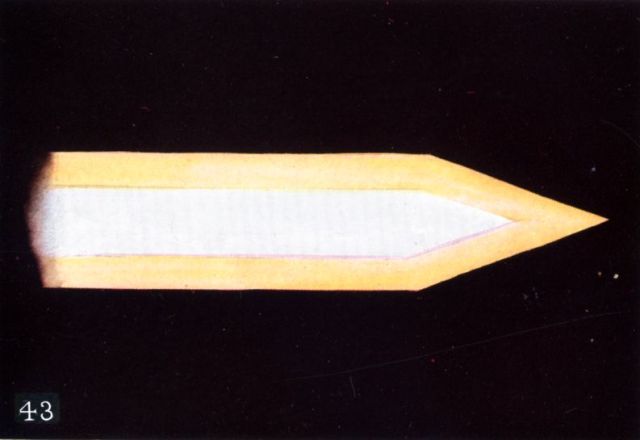

somewhat resembling a projectile or the head of a comet; and it

will be easily understood that this alteration is caused by its

rapid forward motion. The clearness of the colour assures us of

the purity of the emotion which gave birth to this thought-form,

while the precision of its outline is unmistakable evidence of

power and of vigorous purpose. The soul that gave birth to a

thought-form such as this must already be one of a certain amount

of development.

FIG. 10. DEFINITE AFFECTION

FIG. 10. DEFINITE AFFECTION

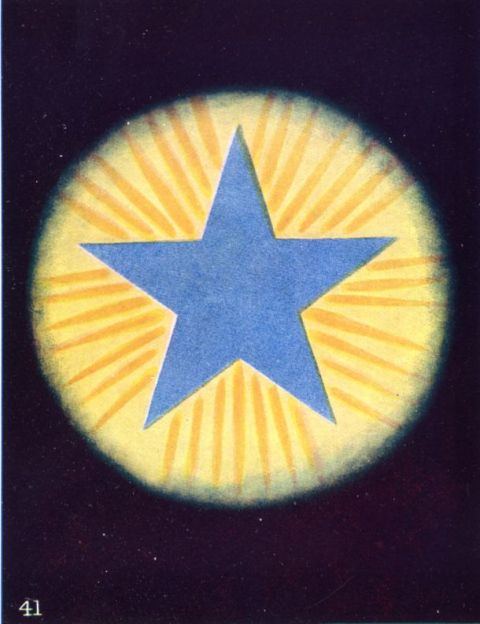

Radiating Affection.—Fig. 11 gives us our first

example of a thought-form intentionally generated, since its

author is making the effort to pour himself forth in love to all

beings. It must be remembered that all these forms are in

constant motion. This one, for example, is steadily widening out,

though there seems to be an exhaustless fountain welling up

through the centre from a dimension which we cannot represent. A

sentiment such as this is so wide in its application, that it is

very difficult for any one not thoroughly trained to keep it

clear and precise. The thought-form here shown is, therefore, a

very creditable one, for it will be noted that all the numerous

rays of the star are commendably free from vagueness.

FIG. 11. RADIATING AFFECTION

FIG. 11. RADIATING AFFECTION

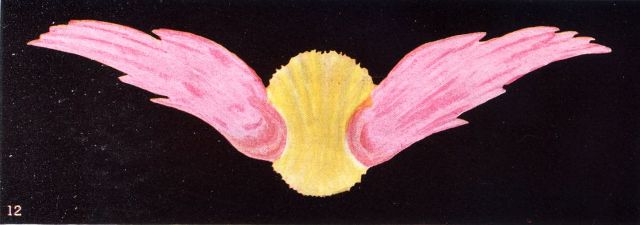

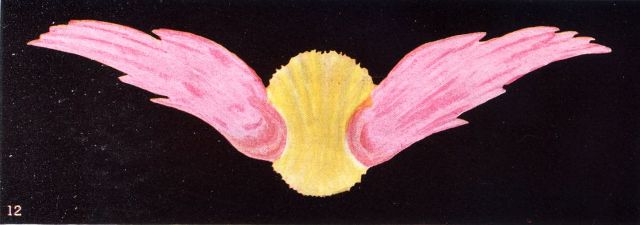

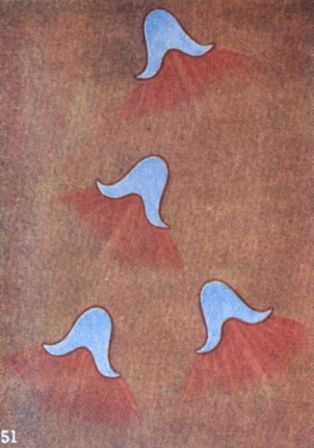

Peace and Protection.—Few thought-forms are more

beautiful and expressive than this which we see in Fig. 12. This

is a thought of love and peace, protection and benediction, sent

forth by one who has the power and has earned the right to bless.

It is not at all probable that in the mind of its creator there

existed any thought of its beautiful wing-like shape, though it

is possible that some unconscious reflection of far-away lessons

of childhood about guardian angels who always hovered over their

charges may have had its influence in determining this. However

that may be, the earnest wish undoubtedly clothed itself in this

graceful and expressive outline, while the affection that

prompted it gave to it its lovely rose-colour, and the intellect

which guided it shone forth like sunlight as its heart and

central support. Thus in sober truth we may make veritable

guardian angels to hover over and protect those whom we love, and

many an unselfish earnest wish for good produces such a form as

this, though all unknown to its creator.

FIG. 12. PEACE AND PROTECTION

FIG. 12. PEACE AND PROTECTION

Grasping Animal Affection.—Fig. 13 gives us an

instance of grasping animal affection—if indeed such a

feeling as this be deemed worthy of the august name of affection

at all. Several colours bear their share in the production of its

dull unpleasing hue, tinged as it is with the lurid gleam of

sensuality, as well as deadened with the heavy tint indicative of

selfishness. Especially characteristic is its form, for those

curving hooks are never seen except when there exists a strong

craving for personal possession. It is regrettably evident that

the fabricator of this thought-form had no conception of the

self-sacrificing love which pours itself out in joyous service,

never once thinking of result or return; his thought has been,

not "How much can I give?" but "How much can I gain?" and so it

has expressed itself in these re-entering curves. It has not even

ventured to throw itself boldly outward, as do other thoughts,

but projects half-heartedly from the astral body, which must be

supposed to be on the left of the picture. A sad travesty of the

divine quality love; yet even this is a stage in evolution, and

distinctly an improvement upon earlier stages, as will presently

be seen.

FIG. 13. GRASPING ANIMAL

AFFECTION

FIG. 13. GRASPING ANIMAL

AFFECTION

DEVOTION

Vague Religious Feeling.—Fig. 14 shows us another

shapeless rolling cloud, but this time it is blue instead of

crimson. It betokens that vaguely pleasurable religious

feeling—a sensation of devoutness rather than of

devotion—which is so common among those in whom piety is

more developed than intellect. In many a church one may see a

great cloud of deep dull blue floating over the heads of the

congregation—indefinite in outline, because of the

indistinct nature of the thoughts and feelings which cause it;

flecked too often with brown and grey, because ignorant devotion

absorbs with deplorable facility the dismal tincture of

selfishness or fear; but none the less adumbrating a mighty

potentiality of the future, manifesting to our eyes the first

faint flutter of one at least of the twin wings of devotion and

wisdom, by the use of which the soul flies upward to God from

whom it came.

FIG. 14. VAGUE RELIGIOUS

FEELING

FIG. 14. VAGUE RELIGIOUS

FEELING

Strange is it to note under what varied circumstances this

vague blue cloud may be seen; and oftentimes its absence speaks

more loudly than its presence. For in many a fashionable place of

worship we seek it in vain, and find instead of it a vast

conglomeration of thought-forms of that second type which take

the shape of material objects. Instead of tokens of devotion, we

see floating above the "worshippers" the astral images of hats

and bonnets, of jewellery and gorgeous dresses, of horses and of

carriages, of whisky-bottles and of Sunday dinners, and sometimes

of whole rows of intricate calculations, showing that men and

women alike have had during their supposed hours of prayer and

praise no thoughts but of business or of pleasure, of the desires

or the anxieties of the lower form of mundane existence.

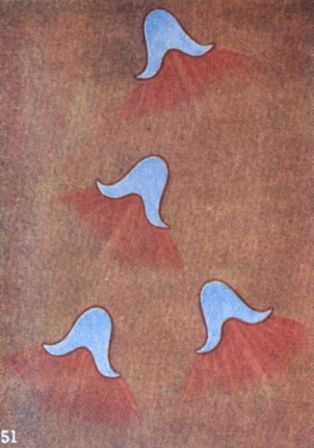

Yet sometimes in a humbler fane, in a church belonging to the

unfashionable Catholic or Ritualist, or even in a lowly

meeting-house where there is but little of learning or of

culture, one may watch the deep blue clouds rolling ceaselessly

eastward towards the altar, or upwards, testifying at least to

the earnestness and the reverence of those who give them birth.

Rarely—very rarely—among the clouds of blue will

flash like a lance cast by the hand of a giant such a

thought-form as is shown in Fig. 15; or such a flower of

self-renunciation as we see in Fig. 16 may float before our

ravished eyes; but in most cases we must seek elsewhere for these

signs of a higher development.

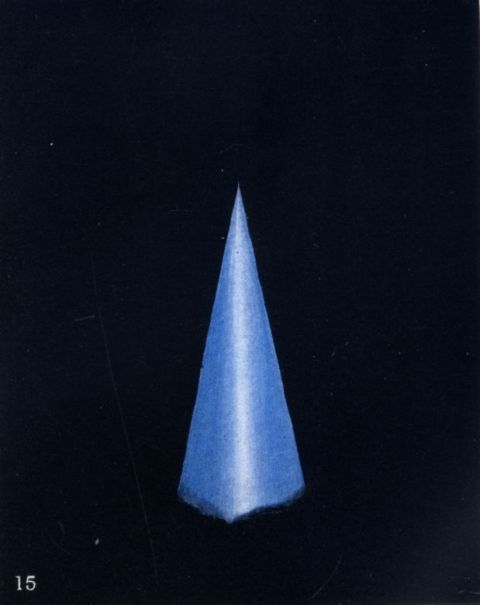

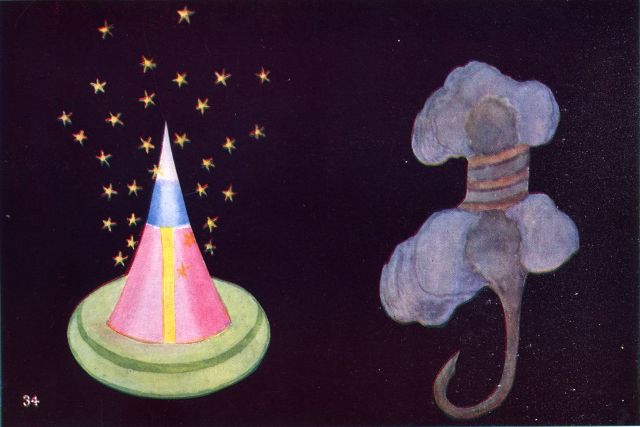

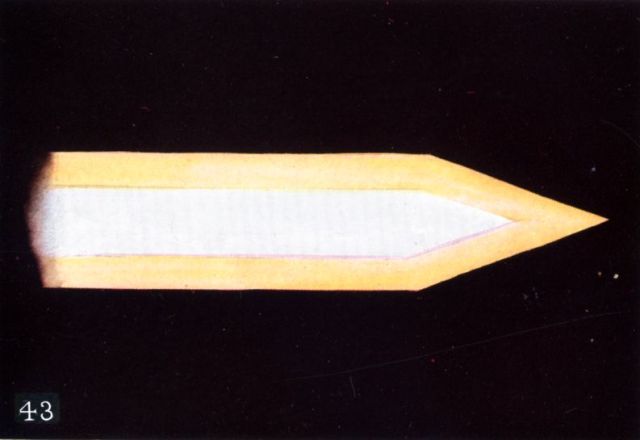

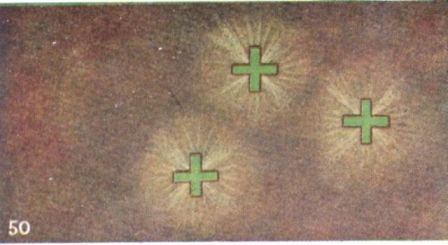

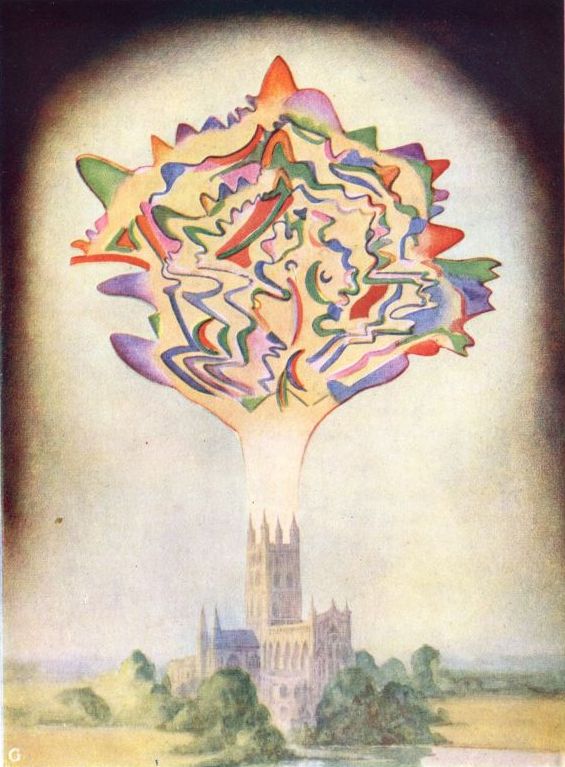

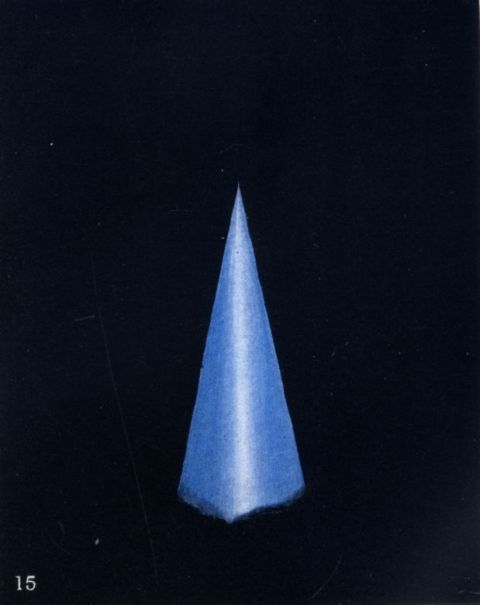

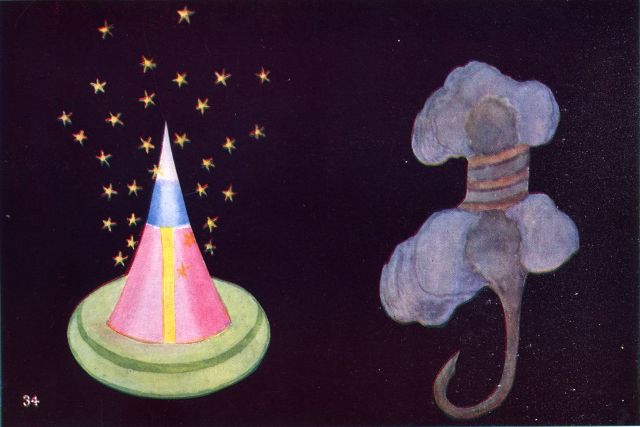

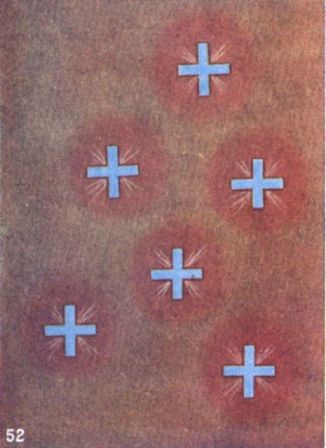

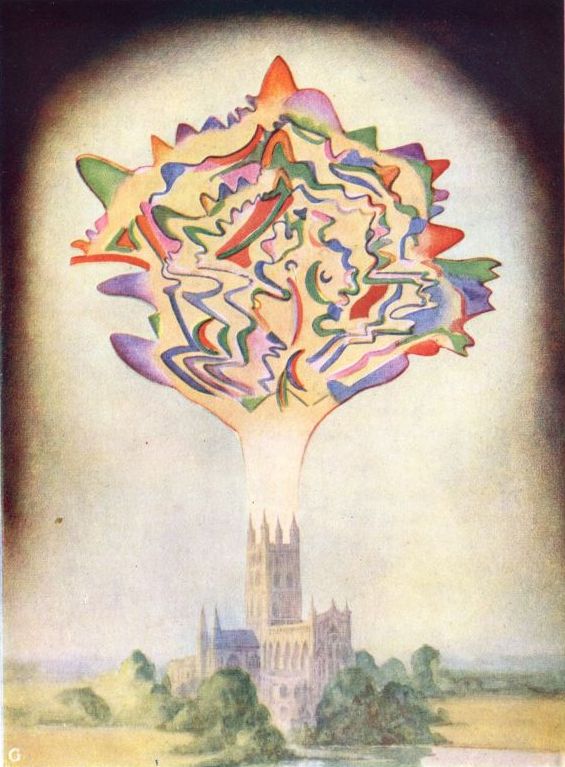

Upward Rush of Devotion.—The form in Fig. 15

bears much the same relation to that of Fig. 14 as did the

clearly outlined projectile of Fig. 10 to the indeterminate cloud

of Fig. 8. We could hardly have a more marked contrast than that

between the inchoate flaccidity of the nebulosity in Fig. 14 and

the virile vigour of the splendid spire of highly developed

devotion which leaps into being before us in Fig. 15. This is no

uncertain half-formed sentiment; it is the outrush into

manifestation of a grand emotion rooted deep in the knowledge of

fact. The man who feels such devotion as this is one who knows in

whom he has believed; the man who makes such a thought-form as

this is one who has taught himself how to think. The

determination of the upward rush points to courage as well as

conviction, while the sharpness of its outline shows the clarity

of its creator's conception, and the peerless purity of its

colour bears witness to his utter unselfishness.

FIG. 15. UPWARD RUSH OF

DEVOTION

FIG. 15. UPWARD RUSH OF

DEVOTION

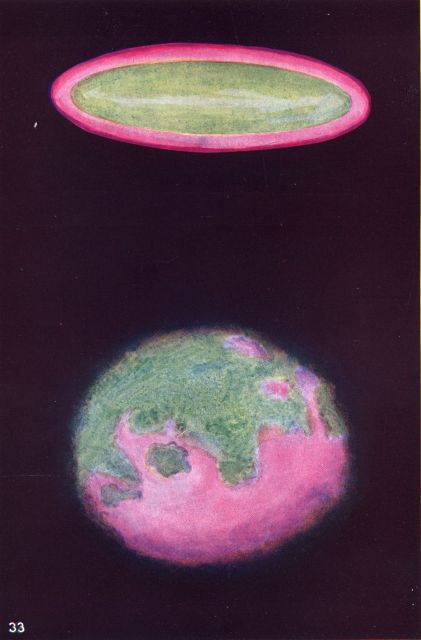

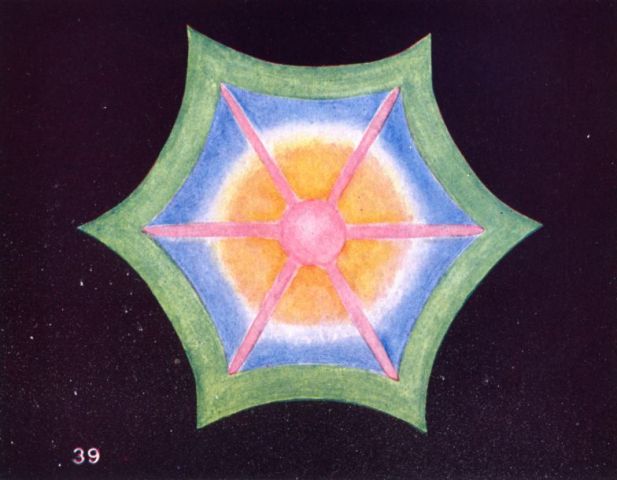

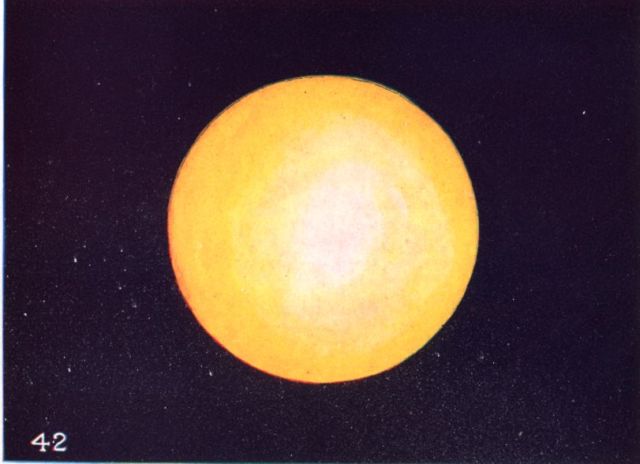

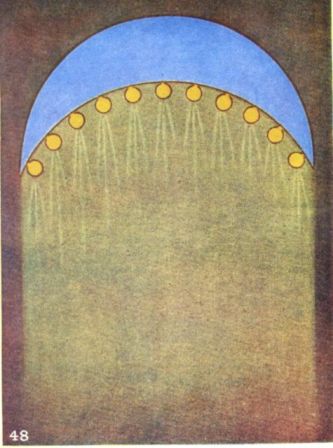

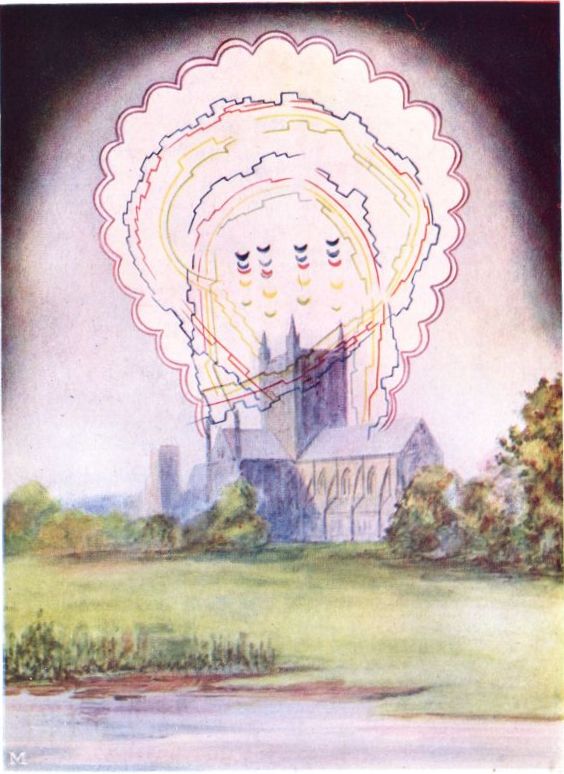

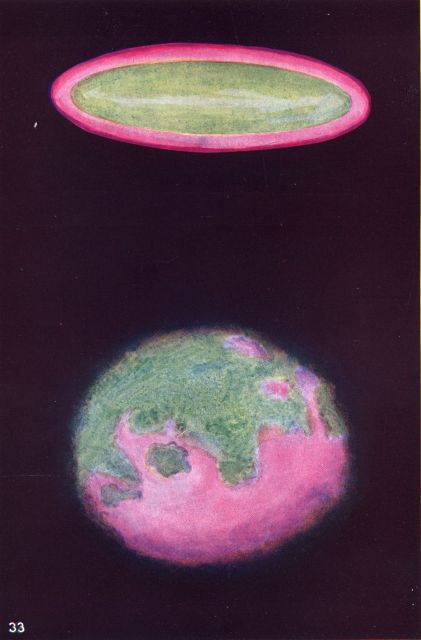

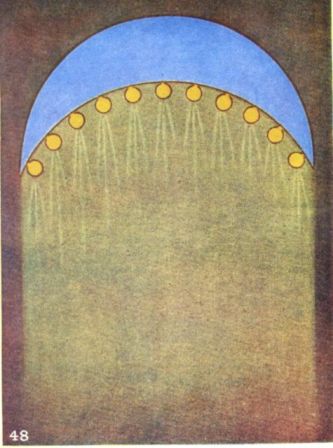

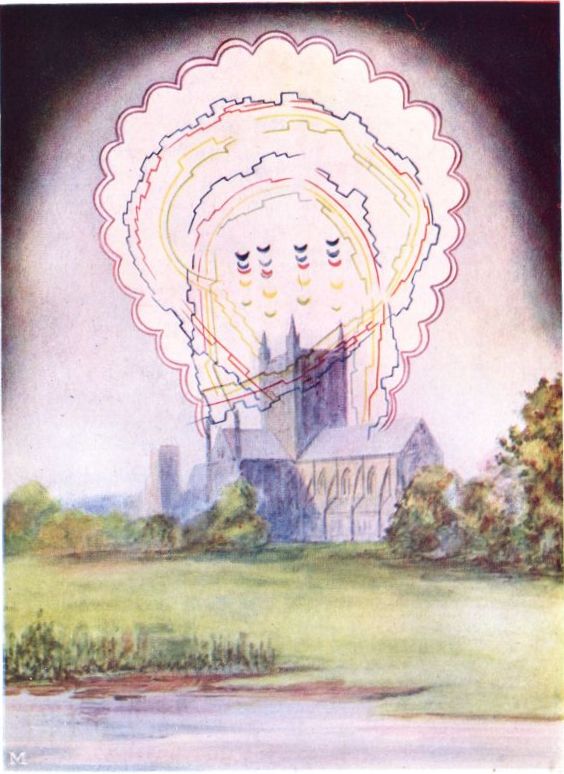

The Response to Devotion.—In Fig. 17 we see the

result of his thought—the response of the Logos to the appeal made to Him, the truth which

underlies the highest and best part of the persistent belief in

an answer to prayer. It needs a few words of explanation. On

every plane of His solar system our Logos pours forth His light, His power, His life,

and naturally it is on the higher planes that this outpouring of

divine strength can be given most fully. The descent from each

plane to that next below it means an almost paralysing

limitation—a limitation entirely incomprehensible except to

those who have experienced the higher possibilities of human

consciousness. Thus the divine life flows forth with incomparably

greater fulness on the mental plane than on the astral; and yet

even its glory at the mental level is ineffably transcended by

that of the buddhic plane. Normally each of these mighty waves of

influence spreads about its appropriate plane—horizontally,

as it were—but it does not pass into the obscuration of a

plane lower than that for which it was originally intended.

FIG. 17. RESPONSE TO DEVOTION

FIG. 17. RESPONSE TO DEVOTION

Yet there are conditions under which the grace and strength

peculiar to a higher plane may in a measure be brought down to a

lower one, and may spread abroad there with wonderful effect.

This seems to be possible only when a special channel is for the

moment opened; and that work must be done from below and by the

effort of man. It has before been explained that whenever a man's

thought or feeling is selfish, the energy which it produces moves

in a close curve, and thus inevitably returns and expends itself

upon its own level; but when the thought or feeling is absolutely

unselfish, its energy rushes forth in an open curve, and thus

does not return in the ordinary sense, but pierces through

into the plane above, because only in that higher condition, with

its additional dimension, can it find room for its expansion. But

in thus breaking through, such a thought or feeling holds open a

door (to speak symbolically) of dimension equivalent to its own

diameter, and thus furnishes the requisite channel through which

the divine force appropriate to the higher plane can pour itself

into the lower with marvellous results, not only for the thinker

but for others. An attempt is made in Fig. 17 to symbolise this,

and to indicate the great truth that an infinite flood of the

higher type of force is always ready and waiting to pour through

when the channel is offered, just as the water in a cistern may

be said to be waiting to pour through the first pipe that may be

opened.

The result of the descent of divine life is a very great

strengthening and uplifting of the maker of the channel, and the

spreading all about him of a most powerful and beneficent

influence. This effect has often been called an answer to prayer,

and has been attributed by the ignorant to what they call a

"special interposition of Providence," instead of to the unerring

action of the great and immutable divine law.

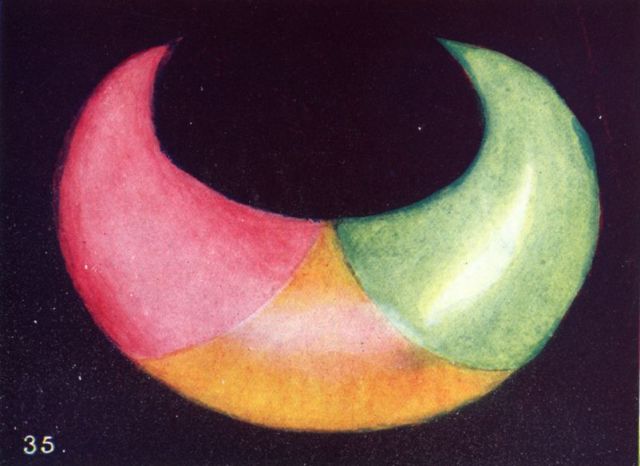

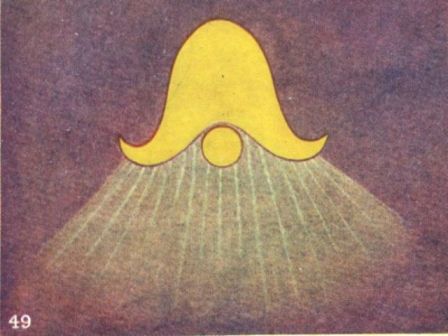

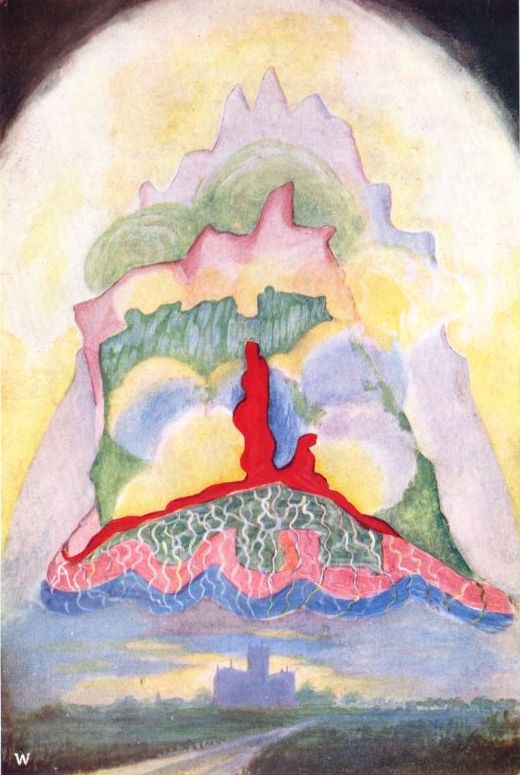

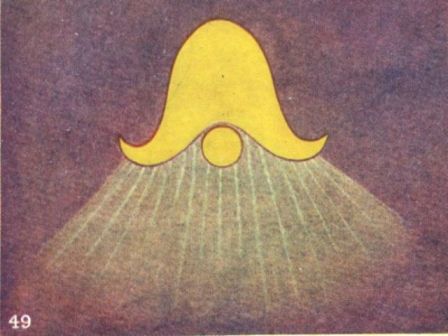

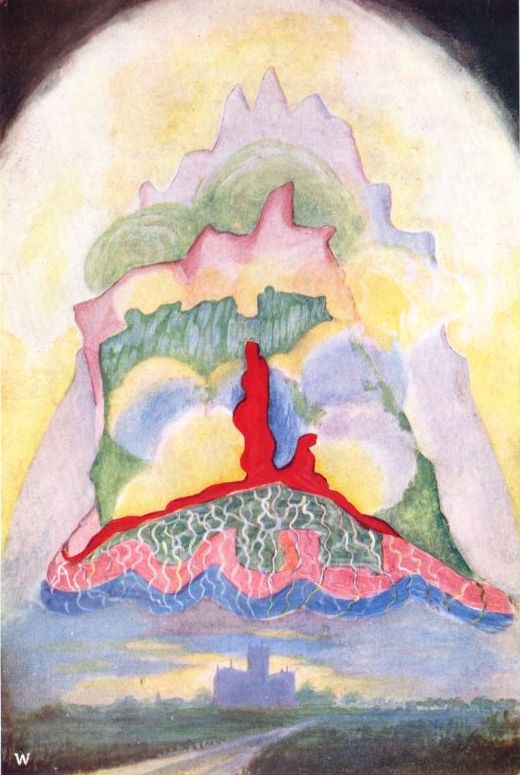

Self-Renunciation.—Fig. 16 gives us yet another

form of devotion, producing an exquisitely beautiful form of a

type quite new to us—a type in which one might at first

sight suppose that various graceful shapes belonging to animate

nature were being imitated. Fig. 16, for example, is somewhat

suggestive of a partially opened flower-bud, while other forms

are found to bear a certain resemblance to shells or leaves or

tree-shapes. Manifestly, however, these are not and cannot be

copies of vegetable or animal forms, and it seems probable that

the explanation of the similarity lies very much deeper than

that. An analogous and even more significant fact is that some

very complex thought-forms can be exactly imitated by the action

of certain mechanical forces, as has been said above. While with

our present knowledge it would be unwise to attempt a solution of

the very fascinating problem presented by these remarkable

resemblances, it seems likely that we are obtaining a glimpse

across the threshold of a very mighty mystery, for if by certain

thoughts we produce a form which has been duplicated by the

processes of nature, we have at least a presumption that these

forces of nature work along lines somewhat similar to the action

of those thoughts. Since the universe is itself a mighty

thought-form called into existence by the Logos, it may well be that tiny parts of it are

also the thought-forms of minor entities engaged in the same

work; and thus perhaps we may approach a comprehension of what is

meant by the three hundred and thirty million Devas of the

Hindus.

FIG. 16. SELF-RENUNCIATION

FIG. 16. SELF-RENUNCIATION

This form is of the loveliest pale azure, with a glory of

white light shining through it—something indeed to tax the

skill even of the indefatigable artist who worked so hard to get

them as nearly right as possible. It is what a Catholic would

call a definite "act of devotion"—better still, an act of

utter selflessness, of self-surrender and renunciation.

INTELLECT

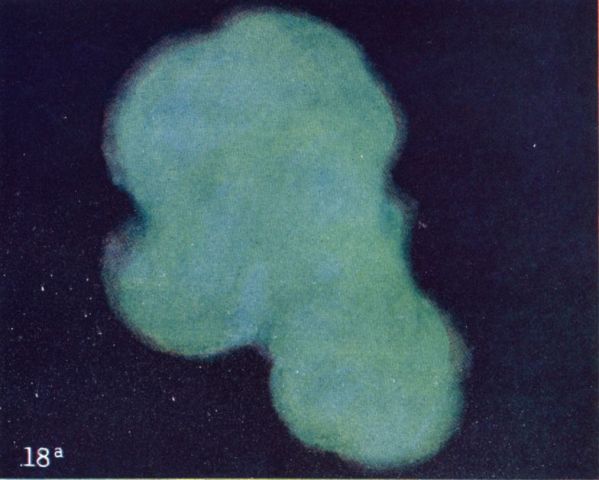

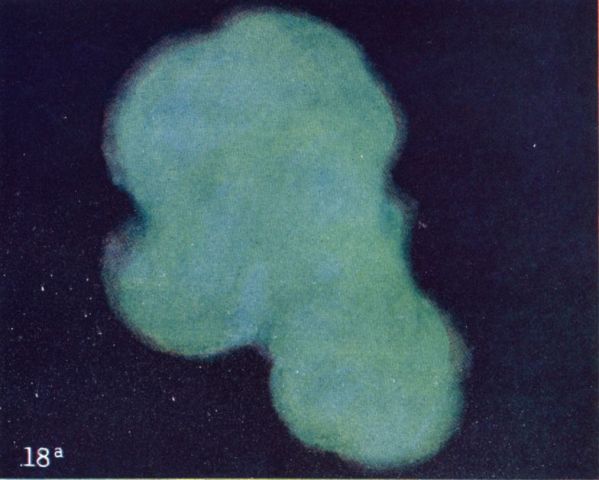

Vague Intellectual Pleasure.—Fig. 18 represents a

vague cloud of the same order as those shown in Figs. 8 and 14,

but in this case the colour is yellow instead of crimson or blue.

Yellow in any of man's vehicles always indicates intellectual

capacity, but its shades vary very much, and it may be

complicated by the admixture of other hues. Generally speaking,

it has a deeper and duller tint if the intellect is directed

chiefly into lower channels, more especially if the objects are

selfish. In the astral or mental body of the average man of

business it would show itself as yellow ochre, while pure

intellect devoted to the study of philosophy or mathematics

appears frequently to be golden, and this rises gradually to a

beautiful clear and luminous lemon or primrose yellow when a

powerful intellect is being employed absolutely unselfishly for

the benefit of humanity. Most yellow thought-forms are clearly

outlined, and a vague cloud of this colour is comparatively rare.

It indicates intellectual pleasure—appreciation of the

result of ingenuity, or the delight felt in clever workmanship.

Such pleasure as the ordinary man derives from the contemplation

of a picture usually depends chiefly upon the emotions of

admiration, affection, or pity which it arouses within him, or

sometimes, if it pourtrays a scene with which he is familiar, its

charm consists in its power to awaken the memory of past joys. An

artist, however, may derive from a picture a pleasure of an

entirely different character, based upon his recognition of the

excellence of the work, and of the ingenuity which has been

exercised in producing certain results. Such pure intellectual

gratification shows itself in a yellow cloud; and the same effect

may be produced by delight in musical ingenuity, or the

subtleties of argument. A cloud of this nature betokens the

entire absence of any personal emotion, for if that were present

it would inevitably tinge the yellow with its own appropriate

colour.

FIG. 18. VAGUE INTELLECTUAL

PLEASURE

FIG. 18. VAGUE INTELLECTUAL

PLEASURE

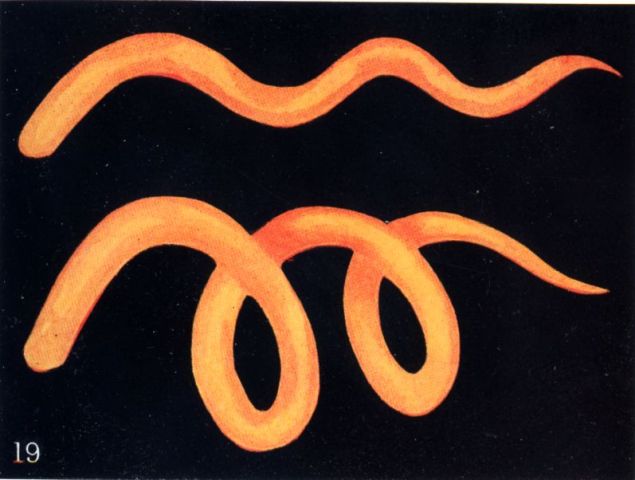

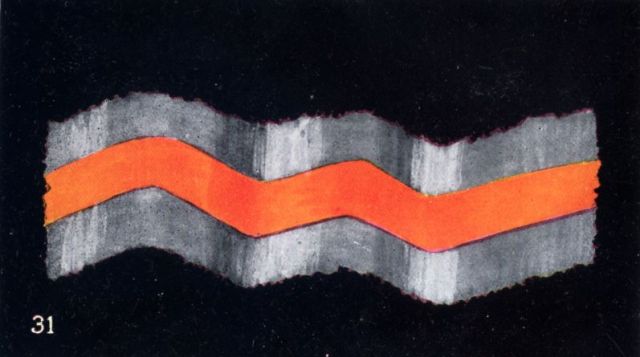

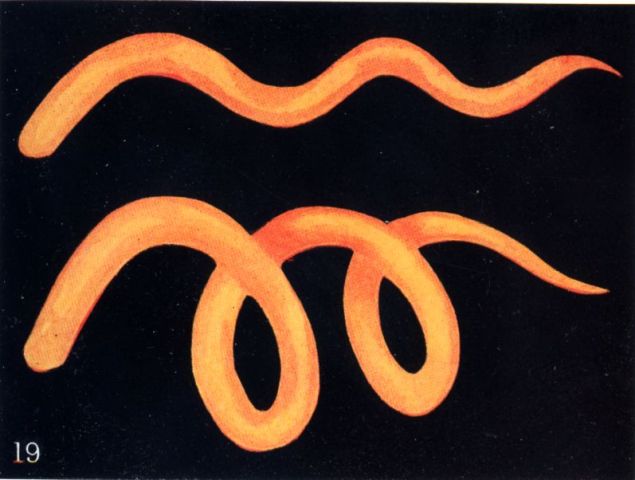

The Intention to Know.—Fig. 19 is of interest as

showing us something of the growth of a thought-form. The earlier

stage, which is indicated by the upper form, is not uncommon, and

indicates the determination to solve some problem—the

intention to know and to understand. Sometimes a theosophical

lecturer sees many of these yellow serpentine forms projecting

towards him from his audience, and welcomes them as a token that

his hearers are following his arguments intelligently, and have

an earnest desire to understand and to know more. A form of this

kind frequently accompanies a question, and if, as is sometimes

unfortunately the case, the question is put less with the genuine

desire for knowledge than for the purpose of exhibiting the

acumen of the questioner, the form is strongly tinged with the

deep orange that indicates conceit. It was at a theosophical

meeting that this special shape was encountered, and it

accompanied a question which showed considerable thought and

penetration. The answer at first given was not thoroughly

satisfactory to the inquirer, who seems to have received the

impression that his problem was being evaded by the lecturer. His

resolution to obtain a full and thorough answer to his inquiry

became more determined than ever, and his thought-form deepened

in colour and changed into the second of the two shapes,

resembling a cork-screw even more closely than before. Forms

similar to these are constantly created by ordinary idle and

frivolous curiosity, but as there is no intellect involved in

that case the colour is no longer yellow, but usually closely

resembles that of decaying meat, somewhat like that shown in Fig.

29 as expressing a drunken man's craving for alcohol.

FIG. 19. THE INTENTION TO KNOW

FIG. 19. THE INTENTION TO KNOW

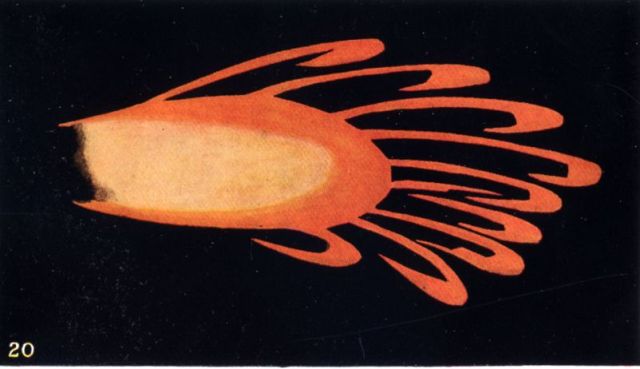

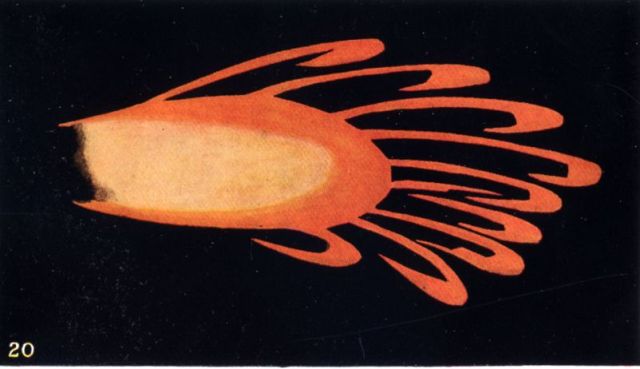

High

Ambition.—Fig. 20 gives us another manifestation of

desire—the ambition for place or power. The ambitious

quality is shown by the rich deep orange colour, and the desire

by the hooked extensions which precede the form as it moves. The

thought is a good and pure one of its kind, for if there were

anything base or selfish in the desire it would inevitably show

itself in the darkening of the clear orange hue by dull reds,

browns, or greys. If this man coveted place or power, it was not

for his own sake, but from the conviction that he could do the

work well and truly, and to the advantage of his fellow-men.

FIG. 20. HIGH AMBITION

FIG. 20. HIGH AMBITION

Selfish Ambition.—Ambition of a lower type is

represented in Fig. 21. Not only have we here a large stain of

the dull brown-grey of selfishness, but there is also a

considerable difference in the form, though it appears to possess

equal definiteness of outline. Fig. 20 is rising steadily onward

towards a definite object, for it will be observed that the

central part of it is as definitely a projectile as Fig. 10. Fig.

21, on the other hand, is a floating form, and is strongly

indicative of general acquisitiveness—the ambition to grasp

for the self everything that is within sight.

FIG. 21. SELFISH AMBITION

FIG. 21. SELFISH AMBITION

ANGER

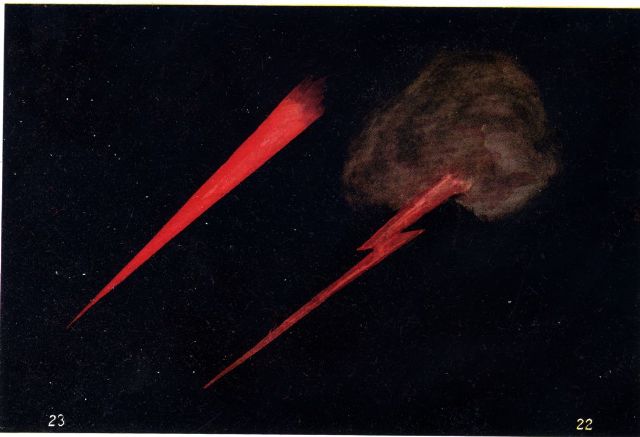

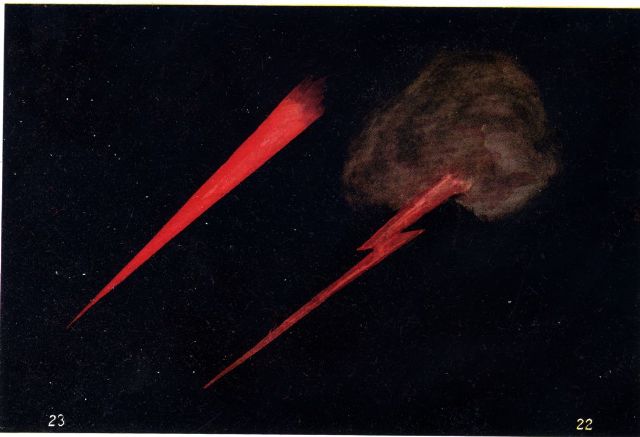

Murderous Rage and Sustained Anger.—In Figs. 22

and 23 we have two terrible examples of the awful effect of

anger. The lurid flash from dark clouds (Fig. 22) was taken from

the aura of a rough and partially intoxicated man in the East End

of London, as he struck down a woman; the flash darted out at her

the moment before he raised his hand to strike, and caused a

shuddering feeling of horror, as though it might slay. The

keen-pointed stiletto-like dart (Fig. 23) was a thought of steady

anger, intense and desiring vengeance, of the quality of murder,

sustained through years, and directed against a person who had

inflicted a deep injury on the one who sent it forth; had the

latter been possessed of a strong and trained will, such a

thought-form would slay, and the one nourishing it is running a

very serious danger of becoming a murderer in act as well as in

thought in a future incarnation. It will be noted that both of

them take the flash-like form, though the upper is irregular in

its shape, while the lower represents a steadiness of intention

which is far more dangerous. The basis of utter selfishness out

of which the upper one springs is very characteristic and

instructive. The difference in colour between the two is also

worthy of note. In the upper one the dirty brown of selfishness

is so strongly evident that it stains even the outrush of anger;

while in the second case, though no doubt selfishness was at the

root of that also, the original thought has been forgotten in the

sustained and concentrated wrath. One who studies Plate XIII. in

Man Visible and Invisible will be able to image to himself

the condition of the astral body from which these forms are

protruding; and surely the mere sight of these pictures, even

without examination, should prove a powerful object-lesson in the

evil of yielding to the passion of anger.

FIG. 23. SUSTAINED ANGER FIG. 22. MURDEROUS

RAGE

FIG. 23. SUSTAINED ANGER FIG. 22. MURDEROUS

RAGE

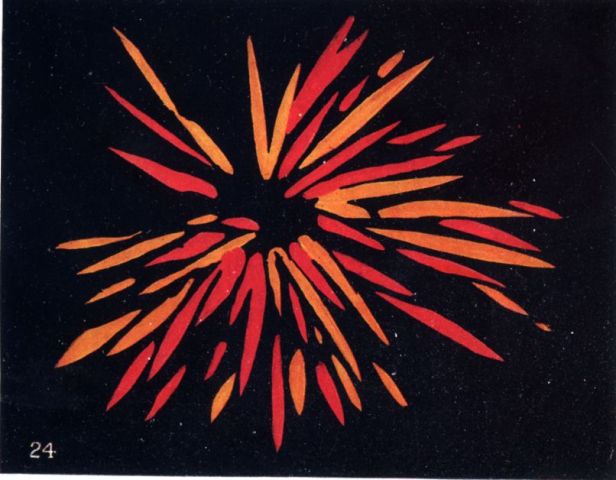

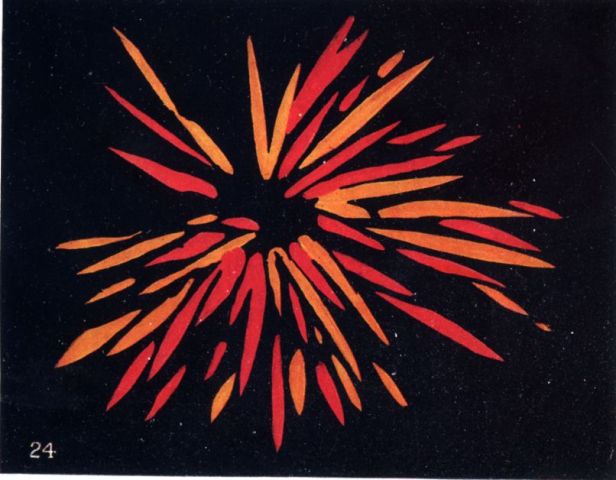

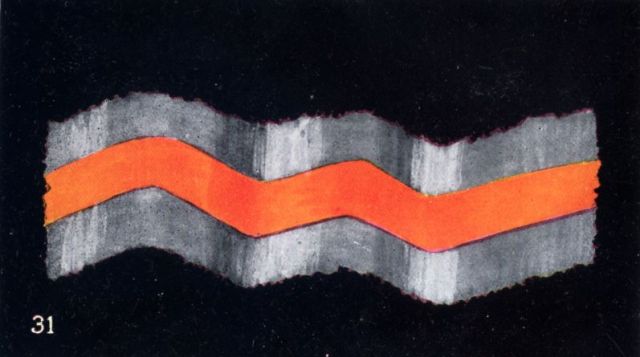

Explosive Anger.—In Fig. 24 we see an exhibition

of anger of a totally different character. Here is no sustained

hatred, but simply a vigorous explosion of irritation. It is at

once evident that while the creators of the forms shown in Figs.

22 and 23 were each directing their ire against an individual,

the person who is responsible for the explosion in Fig. 24 is for

the moment at war with the whole world round him. It may well

express the sentiment of some choleric old gentleman, who feels

himself insulted or impertinently treated, for the dash of orange

intermingled with the scarlet implies that his pride has been

seriously hurt. It is instructive to compare the radiations of

this plate with those of Fig. 11. Here we see indicated a

veritable explosion, instantaneous in its passing and irregular

in its effects; and the vacant centre shows us that the feeling

that caused it is already a thing of the past, and that no

further force is being generated. In Fig. 11, on the other hand,

the centre is the strongest part of the thought-form, showing

that this is not the result of a momentary flash of feeling, but

that there is a steady continuous upwelling of the energy, while

the rays show by their quality and length and the evenness of

their distribution the steadily sustained effort which produces

them.

FIG. 24. EXPLOSIVE ANGER

FIG. 24. EXPLOSIVE ANGER

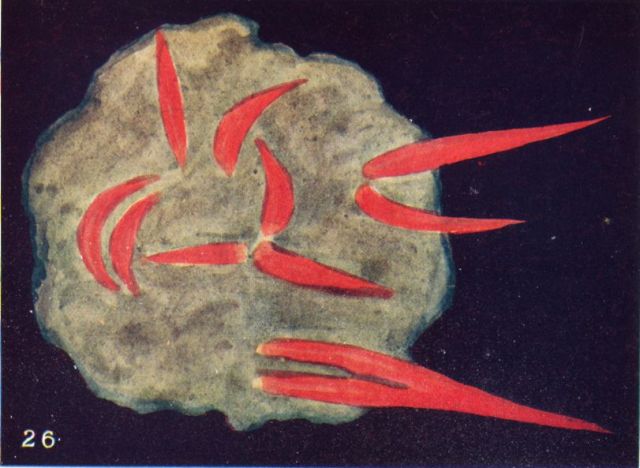

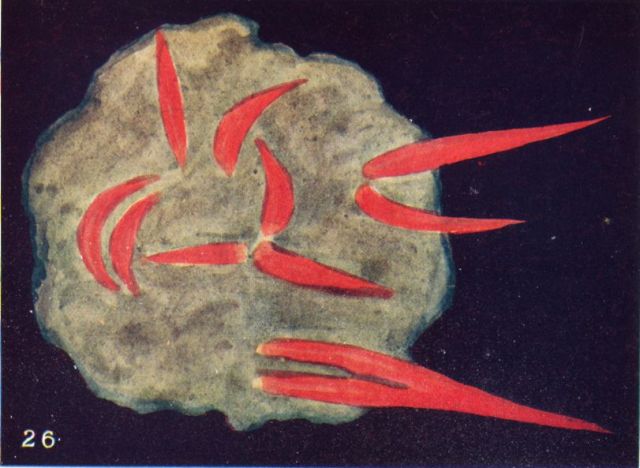

Watchful and Angry Jealousy.—In Fig. 25 we see an

interesting though unpleasant thought-form. Its peculiar

brownish-green colour at once indicates to the practised

clairvoyant that it is an expression of jealousy, and its curious

shape shows the eagerness with which the man is watching its

object. The remarkable resemblance to the snake with raised head

aptly symbolises the extraordinarily fatuous attitude of the

jealous person, keenly alert to discover signs of that which he

least of all wishes to see. The moment that he does see it, or

imagines that he sees it, the form will change into the far

commoner one shown in Fig. 26, where the jealousy is already

mingled with anger. It may be noted that here the jealousy is

merely a vague cloud, though interspersed with very definite

flashes of anger ready to strike at those by whom it fancies

itself to be injured; whereas in Fig. 25, where there is no anger

as yet, the jealousy itself has a perfectly definite and very

expressive outline.

FIG. 25. WATCHFUL JEALOUSY

FIG. 25. WATCHFUL JEALOUSY

FIG. 26. ANGRY JEALOUSY

FIG. 26. ANGRY JEALOUSY

SYMPATHY

Vague Sympathy.—In Fig. 18A we have another of

the vague clouds, but this time its green colour shows us that it

is a manifestation of the feeling of sympathy. We may infer from

the indistinct character of its outline that it is not a definite

and active sympathy, such as would instantly translate itself

from thought into deed; it marks rather such a general feeling of

commiseration as might come over a man who read an account of a

sad accident, or stood at the door of a hospital ward looking in

upon the patients.

FIG. 18A. VAGUE SYMPATHY

FIG. 18A. VAGUE SYMPATHY

FEAR

Sudden Fright.—One of the most pitiful objects in

nature is a man or an animal in a condition of abject fear; and

an examination of Plate XIV. in Man Visible and Invisible

shows that under such circumstances the astral body presents no

better appearance than the physical. When a man's astral body is

thus in a state of frenzied palpitation, its natural tendency is

to throw off amorphous explosive fragments, like masses of rock

hurled out in blasting, as will be seen in Fig. 30; but when a

person is not terrified but seriously startled, an effect such as

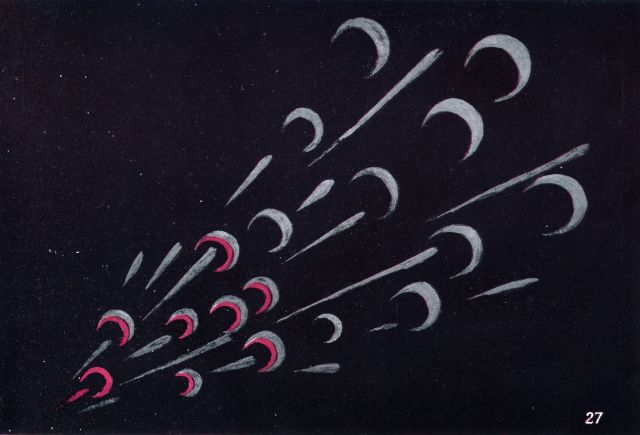

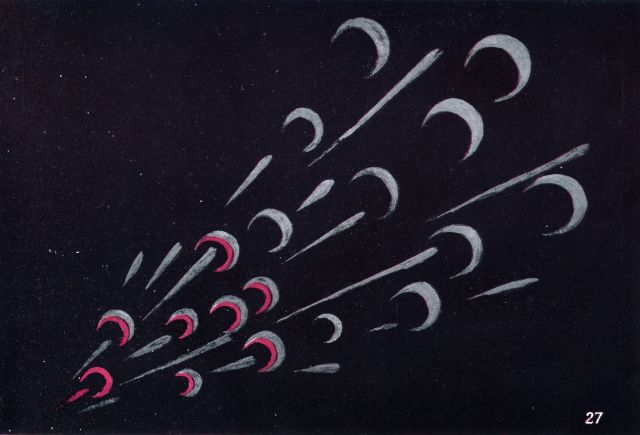

that shown in Fig. 27 is often produced. In one of the

photographs taken by Dr Baraduc of Paris, it was noticed that an

eruption of broken circles resulted from sudden annoyance, and

this outrush of crescent-shaped forms seems to be of somewhat the

same nature, though in this case there are the accompanying lines

of matter which even increase the explosive appearance. It is

noteworthy that all the crescents to the right hand, which must

obviously have been those expelled earliest, show nothing but the

livid grey of fear; but a moment later the man is already

partially recovering from the shock, and beginning to feel angry

that he allowed himself to be startled. This is shown by the fact

that the later crescents are lined with scarlet, evidencing the

mingling of anger and fear, while the last crescent is pure

scarlet, telling us that even already the fright is entirely

overcome, and only the annoyance remains.

FIG. 27. SUDDEN FRIGHT

FIG. 27. SUDDEN FRIGHT

GREED

Selfish Greed.—Fig. 28 gives us an example of

selfish greed—a far lower type than Fig. 21. It will be

noted that here there is nothing even so lofty as ambition, and

it is also evident from the tinge of muddy green that the person

from whom this unpleasant thought is projecting is quite ready to

employ deceit in order to obtain her desire. While the ambition

of Fig. 21 was general in its nature, the craving expressed in

Fig. 28 is for a particular object towards which it is reaching

out; for it will be understood that this thought-form, like that

in Fig. 13, remains attached to the astral body, which must be

supposed to be on the left of the picture. Claw-like forms of

this nature are very frequently to be seen converging upon a

woman who wears a new dress or bonnet, or some specially

attractive article of jewellery. The thought-form may vary in

colour according to the precise amount of envy or jealousy which

is mingled with the lust for possession, but an approximation to

the shape indicated in our illustration will be found in all

cases. Not infrequently people gathered in front of a shop-window

may be seen thus protruding astral cravings through the

glass.

FIG. 28. SELFISH GREED

FIG. 28. SELFISH GREED

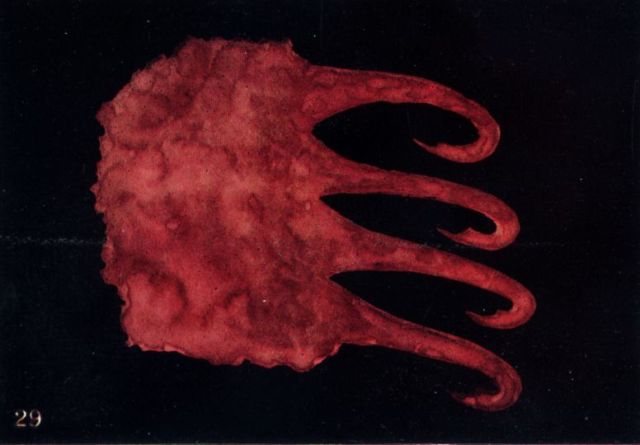

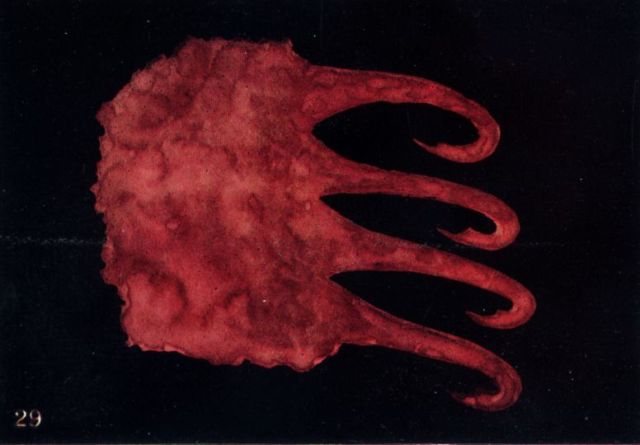

Greed for Drink.—In Fig. 29 we have another

variant of the same passion, perhaps at an even more degraded and

animal level. This specimen was taken from the astral body of a

man just as he entered at the door of a drinking-shop; the

expectation of and the keen desire for the liquor which he was

about to absorb showed itself in the projection in front of him

of this very unpleasant appearance. Once more the hooked

protrusions show the craving, while the colour and the coarse

mottled texture show the low and sensual nature of the appetite.

Sexual desires frequently show themselves in an exactly similar

manner. Men who give birth to forms such as this are as yet but

little removed from the animal; as they rise in the scale of

evolution the place of this form will gradually be taken by

something resembling that shown in Fig. 13, and very slowly, as

development advances, that in turn will pass through the stages

indicated in Figs. 9 and 8, until at last all selfishness is cast

out, and the desire to have has been transmuted into the desire

to give, and we arrive at the splendid results shown in Figs. 11

and 10.

FIG. 29. GREED FOR DRINK

FIG. 29. GREED FOR DRINK

VARIOUS

EMOTIONS

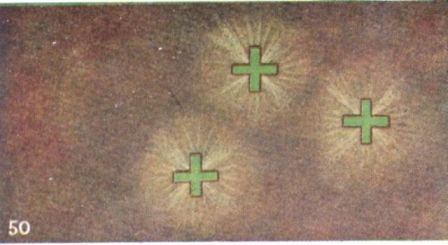

At a Shipwreck.—Very serious is the panic which

has occasioned the very interesting group of thought-forms which

are depicted in Fig. 30. They were seen simultaneously, arranged

exactly as represented, though in the midst of indescribable

confusion, so their relative positions have been retained, though

in explaining them it will be convenient to take them in reverse

order. They were called forth by a terrible accident, and they

are instructive as showing how differently people are affected by

sudden and serious danger. One form shows nothing but an eruption

of the livid grey of fear, rising out of a basis of utter

selfishness: and unfortunately there were many such as this. The

shattered appearance of the thought-form shows the violence and

completeness of the explosion, which in turn indicates that the

whole soul of that person was possessed with blind, frantic

terror, and that the overpowering sense of personal danger

excluded for the time every higher feeling.

FIG. 30. AT A SHIPWRECK

FIG. 30. AT A SHIPWRECK

The second form represents at least an attempt at

self-control, and shows the attitude adopted by a person having a