A New System; or, an Analysis of Ancient Mythology. Volume II

By Jacob Bryant

OB, OUB, PYTHO,

SIVE DE OPHIOLATRIA.

Παρα παντι των νομιζομενων παρ' ὑμιν Θεων Οφις συμβολον μεγα και μυστηριον αναγραφεται. Justin. Martyr. Apolog. l. 1. p. 60.

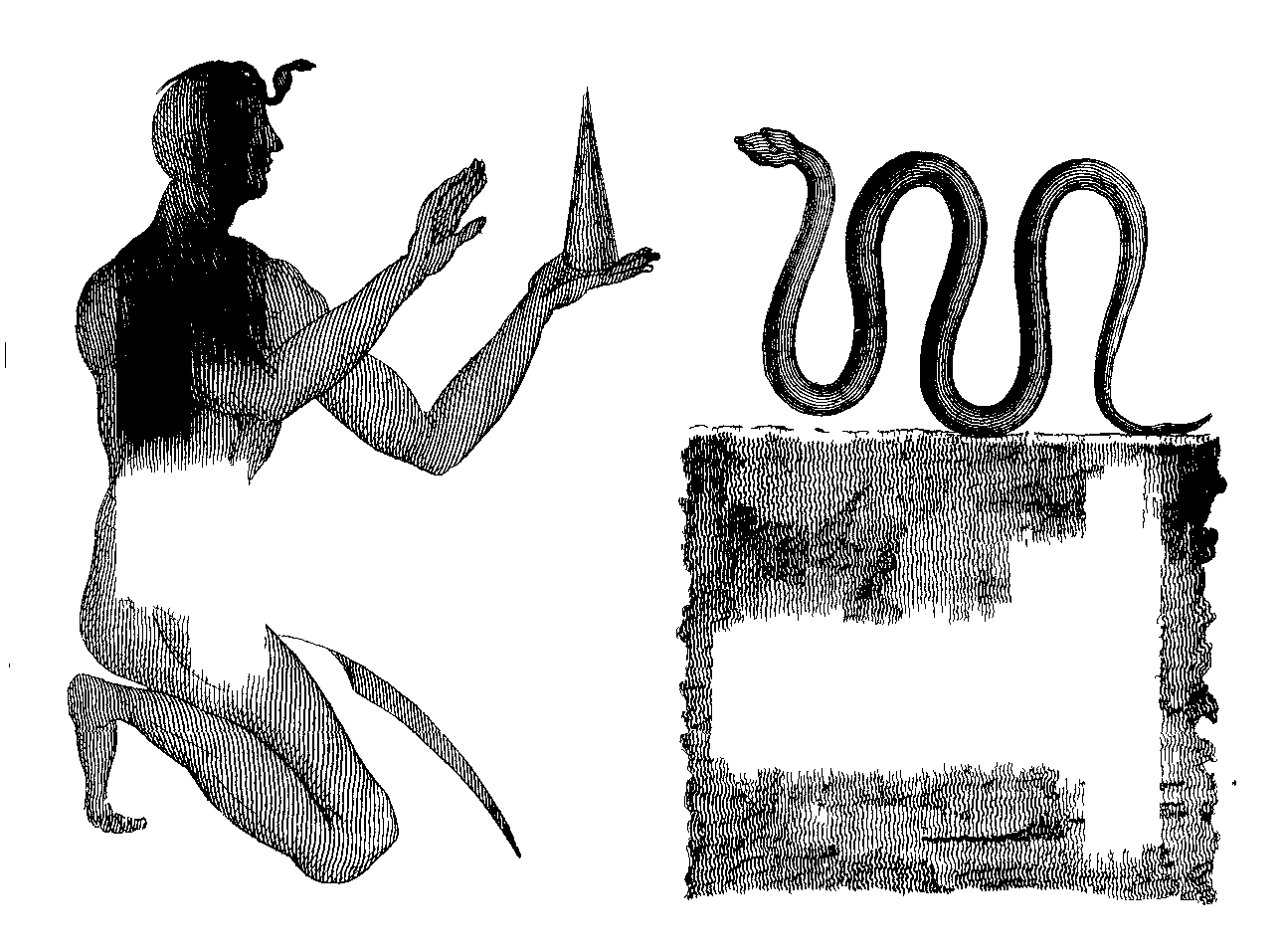

It may seem extraordinary, that the worship of the serpent should have ever been introduced into the world: and it must appear still more remarkable, that it should almost universally have prevailed. As mankind are said to have been ruined through the influence of this being, we could little expect that it would, of all other objects, have been adopted, as the most sacred and salutary symbol; and rendered the chief object of [451]adoration. Yet so we find it to have been. In most of the antient rites there is some allusion to the [452]serpent. I have taken notice, that in the Orgies of Bacchus, the persons who partook of the ceremony used to carry serpents in their hands, and with horrid screams called upon Eva, Eva. They were often crowned with [453]serpents, and still made the same frantic exclamation. One part of the mysterious rites of Jupiter Sabazius was to let a snake slip down the bosom of the person to be initiated, which was taken out below[454]. These ceremonies, and this symbolic worship, began among the Magi, who were the sons of Chus: and by them they were propagated in various parts. Epiphanius thinks, that the invocation, Eva, Eva, related to the great [455]mother of mankind, who was deceived by the serpent: and Clemens of Alexandria is of the same opinion. He supposes, that by this term was meant [456]Ευαν εκεινην, δι' ἡν ἡ πλανη παρηκολουθησε. But I should think, that Eva was the same as Eph, Epha, Opha, which the Greeks rendered Οφις, Ophis, and by it denoted a serpent. Clemens acknowledges, that the term Eva properly aspirated had such a signification. [457]Το ονομα το Ευια δασυνομενον ἑρμηνευεται Οφις. Olympias, the mother of [458]Alexander, was very fond of these Orgies, in which the serpent was introduced. Plutarch mentions, that rites of this sort were practised by the Edonian women near mount Hæmus in Thrace; and carried on to a degree of madness. Olympias copied them closely in all their frantic manœuvres. She used to be followed with many attendants, who had each a thyrsus with [459]serpents twined round it. They had also snakes in their hair, and in the chaplets, which they wore; so that they made a most fearful appearance. Their cries were very shocking: and the whole was attended with a continual repetition of the words, [460]Evoe, Saboe, Hues Attes, Attes Hues, which were titles of the God Dionusus. He was peculiarly named Ὑης; and his priests were the Hyades, and Hyantes. He was likewise styled Evas. [461]Ευας ὁ Διονυσος.

In Egypt was a serpent named Thermuthis, which was looked upon as very sacred; and the natives are said to have made use of it as a royal tiara, with which they ornamented the statues of [462]Isis. We learn from Diodorus Siculus, that the kings of Egypt wore high bonnets, which terminated in a round ball: and the whole was surrounded with figures of [463]asps. The priests likewise upon their bonnets had the representation of serpents. The antients had a notion, that when Saturn devoured his own children, his wife Ops deceived him by substituting a large stone in lieu of one of his sons, which stone was called Abadir. But Ops, and Opis, represented here as a feminine, was the serpent Deity, and Abadir is the same personage under a different denomination. [464]Abadir Deus est; et hoc nomine lapis ille, quem Saturnus dicitur devorâsse pro Jove, quem Græci βαιτυλον vocant.—Abdir quoque et Abadir βαιτυλος. Abadir seems to be a variation of Ob-Adur, and signifies the serpent God Orus. One of these stones, which Saturn was supposed to have swallowed instead of a child, stood, according to [465]Pausanias, at Delphi. It was esteemed very sacred, and used to have libations of wine poured upon it daily; and upon festivals was otherwise honoured. The purport of the above history I imagine to have been this. It was for a long time a custom to offer children at the altar of Saturn: but in process of time they removed it, and in its room erected a στυλος, or stone pillar; before which they made their vows, and offered sacrifices of another nature. This stone, which they thus substituted, was called Ab-Adar, from the Deity represented by it. The term Ab generally signifies a [466]father: but, in this instance, it certainly relates to a serpent, which was indifferently styled Ab, Aub, and [467]Ob. I take Abadon, or, as it is mentioned in the Revelations, Abaddon, to have been the name of the same Ophite God, with whose worship the world had been so long infected. He is termed by the Evangelist [468]Αβαδδων, τον Αγγελον της Αβυσσου, the angel of the bottomless pit; that is, the prince of darkness. In another place he is described as the [469]dragon, that old serpent, which is the devil, and Satan. Hence I think, that the learned Heinsius is very right in the opinion, which he has given upon this passage; when he makes Abaddon the same as the serpent Pytho. Non dubitandum est, quin Pythius Apollo, hoc est spurcus ille spiritus, quem Hebræi Ob, et Abaddon, Hellenistæ ad verbum Απολλυωνα, cæteri Απολλωνα, dixerunt, sub hâc formâ, quâ miseriam humano generi invexit, primo cultus[470].

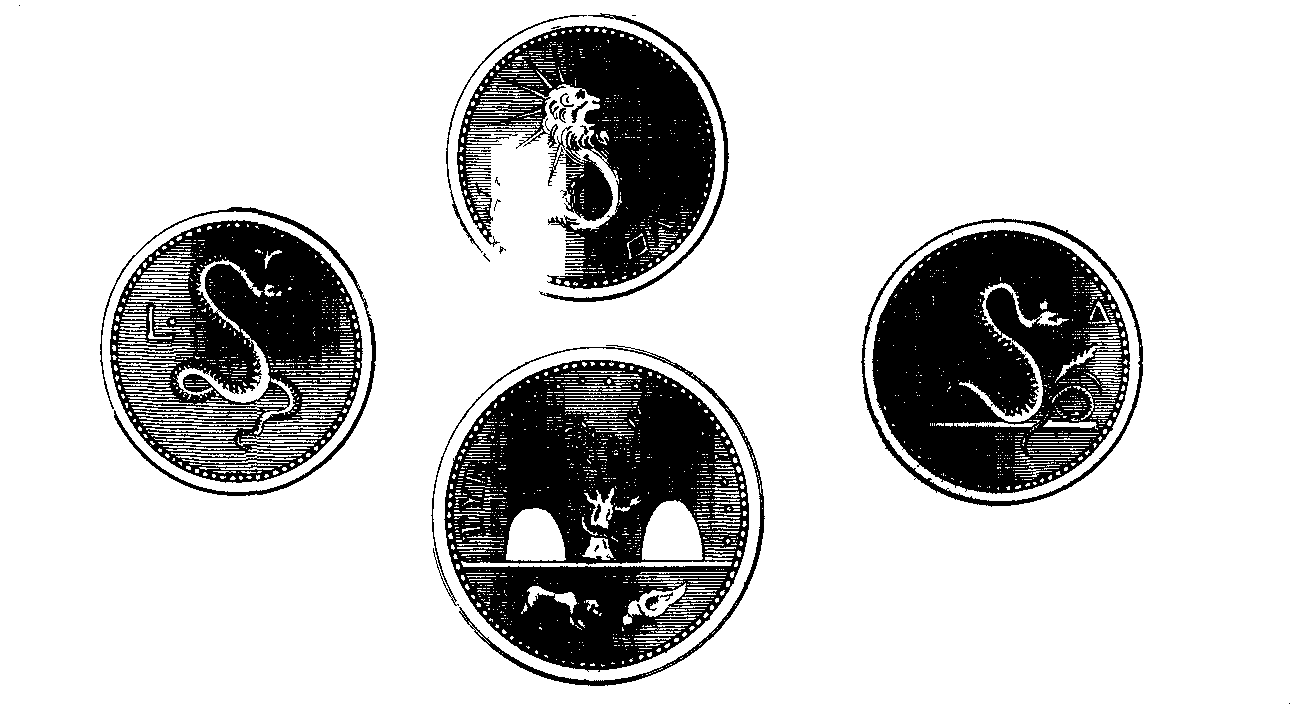

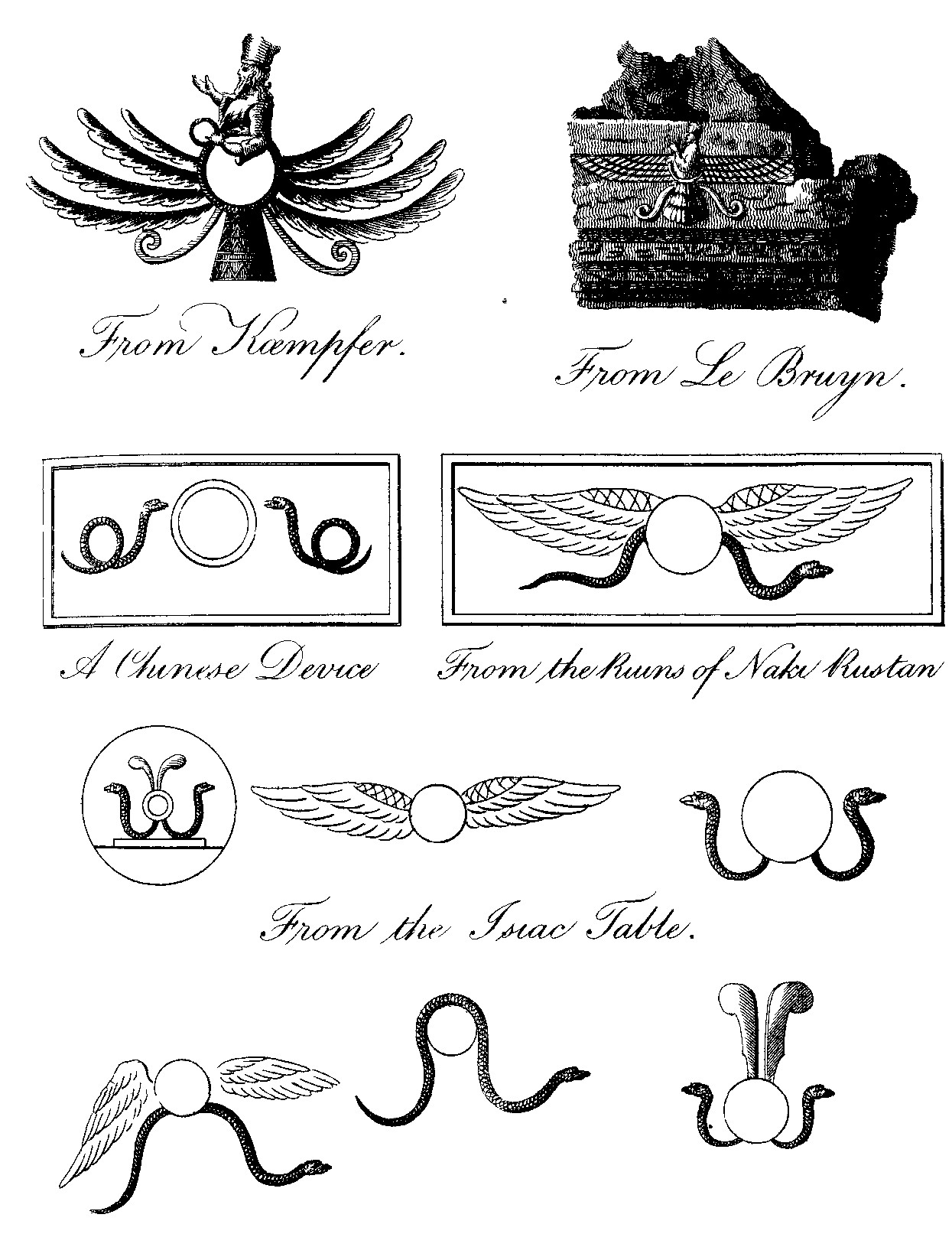

It is said, that, in the ritual of Zoroaster, the great expanse of the heavens, and even nature itself, was described under the symbol of a serpent[471]. The like was mentioned in the Octateuch of Ostanes: and moreover, that in Persis and in other parts of the east they erected temples to the serpent tribe, and held festivals to their honour, esteeming them [472]Θεους τους μεγιστους, και αρχηγους των ὁλων, the supreme of all Gods, and the superintendants of the whole world. The worship began among the people of Chaldea. They built the city Opis upon the [473]Tigris, and were greatly addicted to divination, and to the worship of the serpent[474]. Inventi sunt ex iis (Chaldeis) augures, et magi, divinatores, et sortilegi, et inquirentes Ob, et Ideoni. From Chaldea the worship passed into Egypt, where the serpent Deity was called Can-oph, Can-eph, and C'neph. It had also the name of Ob, or Oub, and was the same as the Basiliscus, or Royal Serpent; the same also as the Thermuthis: and in like manner was made use of by way of ornament to the statues of their [475]Gods. The chief Deity of Egypt is said to have been Vulcan, who was also styled Opas, as we learn from [476]Cicero. He was the same as Osiris, the Sun; and hence was often called Ob-El, sive Pytho Sol: and there were pillars sacred to him with curious hieroglyphical inscriptions, which had the same name. They were very lofty, and narrow in comparison of their length; hence among the Greeks, who copied from the Egyptians, every thing gradually tapering to a point was styled Obelos, and Obeliscus. Ophel (Oph-El) was a name of the same purport: and I have shewn, that many sacred mounds, or Tapha, were thus denominated from the serpent Deity, to whom they were sacred.

Sanchoniathon makes mention of an history, which he once wrote upon the worship of the serpent. The title of this work, according to Eusebius was, [477]Ethothion, or Ethothia. Another treatise upon the same subject was written by Pherecydes Syrus, which was probably a copy of the former; for he is said to have composed it, [478]παρα Φοινικων λαβων τας αφορμας, from some previous accounts of the Phenicians. The title of his book was the Theology of Ophion, styled Ophioneus; and of his worshippers, called Ophionidæ. Thoth, and Athoth, were certainly titles of the Deity in the Gentile world: and the book of Sanchoniathon might very possibly have been from hence named Ethothion, or more truly Athothion. But from the subject, upon which it was written, as well as from the treatise of Pherecydes, I should think, that Athothion, or Ethothion, was a mistake for Ath-ophion, a title which more immediately related to that worship, of which the writer treated. Ath was a sacred title, as I have shewn: and I imagine, that this dissertation did not barely relate to the serpentine Deity; but contained accounts of his votaries, the Ophitæ, the principal of which were the sons of Chus. The worship of the Serpent began among them; and they were from thence denominated Ethopians, and Aithopians, which the Greeks rendered Αιθιοπες. It was a name, which they did not receive from their complexion, as has been commonly surmised; for the branch of Phut, and the Lubim, were probably of a deeper die: but they were so called from Ath-Ope, and Ath-Opis, the God which they worshipped. This may be proved from Pliny. He says that the country Æthiopia (and consequently the people) had the name of Æthiop from a personage who was a Deity—ab [479]Æthiope Vulcani filio. The Æthiopes brought these rites into Greece: and called the island, where they first established them, [480]Ellopia, Solis Serpentis insula. It was the same as Eubœa, a name of the like purport; in which island was a region named Æthiopium. Eubœa is properly Oub-Aia; and signifies the Serpent Island. The same worship prevailed among the Hyperboreans, as we may judge from the names of the sacred women, who used to come annually to Delos. They were priestesses of the Tauric Goddess, and were denominated from her titles.

[481]Ουπις τε, Λοξω τε, και Ευαιων Ἑκαεργη.

Hercules was esteemed the chief God, the same as Chronus; and was said to have produced the Mundane egg. He was represented in the Orphic Theology under the mixed symbol of a [482]lion and serpent: and sometimes of a [483]serpent only. I have before mentioned, that the Cuthites under the title of Heliadæ settled at Rhodes: and, as they were Hivites or Ophites, that the island in consequence of it was of old named Ophiusa. There was likewise a tradition, that it had once swarmed with [484]serpents. The like notion prevailed almost in every place, where they settled. They came under the more general titles of Leleges and Pelasgi: but more particularly of Elopians, Europians, Oropians, Asopians, Inopians, Ophionians, and Æthiopes, as appears from the names, which they bequeathed; and in most places, where they resided, there were handed down traditions, which alluded to their original title of Ophites. In Phrygia, and upon the Hellespont, whither they sent out colonies very early, was a people styled Οφιογενεις, or the serpent-breed; who were said to retain an affinity and correspondence with [485]serpents. And a notion prevailed, that some hero, who had conducted them, was changed from a serpent to a man. In Colchis was a river Ophis; and there was another of the same name in Arcadia. It was so named from a body of people, who settled upon its banks, and were said to have been conducted by a serpent: [486]Τον ἡγεμονα γενεσθαι δρακοντα. These reptiles are seldom found in islands, yet Tenos, one of the Cyclades, was supposed to have once swarmed with them. [487]Εν τῃ Τηνῳ, μιᾳ των Κυκλαδων νησῳ, οφεις και σκορπιοι δεινοι εγινοντο. Thucydides mentions a people of Ætolia called [488]Ophionians: and the temple of Apollo at Patara in Lycia seems to have had its first institution from a priestess of the same [489]name. The island of Cyprus was styled Ophiusa, and Ophiodes, from the serpents, with which it was supposed to have [490]abounded. Of what species they were is no where mentioned; excepting only that about Paphos there was said to have been a [491]kind of serpent with two legs. By this is meant the Ophite race, who came from Egypt, and from Syria, and got footing in this [492]island. They settled also in Crete, where they increased greatly in numbers; so that Minos was said by an unseemly allegory, [493]οφεις ουρησαι, serpentes minxisse. The island Seriphus was one vast rock, by the Romans called [494]saxum seriphium; and made use of as a larger kind of prison for banished persons. It is represented as having once abounded with serpents; and it is styled by Virgil serpentifera, as the passage is happily corrected by Scaliger.

[495]Æginamque simul, serpentiferamque Seriphon.

It had this epithet not on account of any real serpents, but according to the Greeks from [496]Medusa's head, which was brought hither by Perseus. By this is meant the serpent Deity, whose worship was here introduced by people called Peresians. Medusa's head denoted divine wisdom: and the island was sacred to the serpent as is apparent from its name[497]. The Athenians were esteemed Serpentigenæ; and they had a tradition, that the chief guardian of their Acropolis was a [498]serpent. It is reported of the Goddess Ceres, that she placed a dragon for a guardian to her temple at [499]Eleusis; and appointed another to attend upon Erectheus. Ægeus of Athens, according to Androtion, was of the [500]serpent breed: and the first king of the country is said to have been [501]Δρακων, a Dragon. Others make Cecrops the first who reigned. He is said to have been [502]διφυης, of a twofold nature; συμφυες εχων σωμα ανδρος και δρακοντος, being formed with the body of a man blended with that of a serpent. Diodorus says, that this was a circumstance deemed by the Athenians inexplicable: yet he labours to explain it, by representing Cecrops, as half a man, and half a [503]brute; because he had been of two different communities. Eustathius likewise tries to solve it nearly upon the same principles, and with the like success. Some had mentioned of Cecrops, that he underwent a metamorphosis, [504]απο οφεως εις ανθρωπον ελθειν, that he was changed from a serpent to a man. By this was signified according to Eustathius, that Cecrops, by coming into Hellas, divested himself of all the rudeness and barbarity of his [505]country, and became more civilized and humane. This is too high a compliment to be payed to Greece in its infant state, and detracts greatly from the character of the Egyptians. The learned Marsham therefore animadverts with great justice. [506]Est verisimilius ilium ex Ægypto mores magis civiles in Græciam induxisse. It is more probable, that he introduced into Greece, the urbanity of his own country, than that he was beholden to Greece for any thing from thence. In respect to the mixed character of this personage, we may, I think, easily account for it. Cecrops was certainly a title of the Deity, who was worshipped under this [507]emblem. Something of the like nature was mentioned of Triptolemus, and [508]Ericthonius: and the like has been said above of Hercules. The natives of Thebes in Bœotia, like the Athenians above, esteemed themselves of the serpent race. The Lacedæmonians likewise referred themselves to the same original. Their city is said of old to have swarmed with [509]serpents. The same is said of the city Amyclæ in Italy, which was of Spartan original. They came hither in such abundance, that it was abandoned by the [510]inhabitants. Argos was infested in the same manner, till Apis came from Egypt, and settled in that city. He was a prophet, the reputed son of Apollo, and a person of great skill and sagacity. To him they attributed the blessing of having their country freed from this evil.

[511]Απις γαρ ελθων εκ περας Ναυπακτιας,

Ιατρομαντις, παις Απολλωνος, χθονα

Την δ' εκκαθαιρει κνωδαλον βροτοφθορων.

Thus the Argives gave the credit to this imaginary personage of clearing their land of this grievance: but the brood came from the very quarter from whence Apis was supposed to have arrived. They were certainly Hivites from Egypt: and the same story is told of that country. It is represented as having been of old over-run with serpents; and almost depopulated through their numbers. Diodorus Siculus seems to understand this [512]literally: but a region, which was annually overflowed, and that too for so long a season, could not well be liable to such a calamity. They were serpents of another nature, with which it was thus infested: and the history relates to the Cuthites, the original Ophitæ, who for a long time possessed that country. They passed from Egypt to Syria, and to the Euphrates: and mention is made of a particular breed of serpents upon that river, which were harmless to the natives, but fatal to every body else. [513]This, I think, cannot be understood literally. The wisdom of the serpent may be great; but not sufficient to make these distinctions. These serpents were of the same nature as the [514]birds of Diomedes, and the dogs in the temple of Vulcan: and these histories relate to Ophite priests, who used to spare their own people, and sacrifice strangers, a custom which prevailed at one time in most parts of the world. I have mentioned that the Cuthite priests were very learned: and as they were Ophites, whoever had the advantage of their information, was said to have been instructed by serpents. Hence there was a tradition, that Melampus was rendered prophetic from a communication with these [515]animals. Something similar is said of Tiresias.

As the worship of the serpent was of old so prevalent, many places, as well as people from thence, received their names. Those who settled in Campania were called Opici; which some would have changed to Ophici; because they were denominated from serpents. [516]Οι δε (φασιν) ὁτι Οφικοι απο των οφιων. But they are, in reality, both names of the same purport, and denote the origin of the people. We meet with places called Opis, Ophis, Ophitæa, Ophionia, Ophioëssa, Ophiodes, and Ophiusa. This last was an antient name, by which, according to Stephanus, the islands Rhodes, Cythnus, Besbicus, Tenos, and the whole continent of Africa, were distinguished. There were also cities so called. Add to these places denominated Oboth, Obona, and reversed Onoba, from Ob, which was of the same purport. Clemens Alexandrinus says, that the term Eva signified a serpent, if pronounced with a proper [517]aspirate. We find that there were places of this name. There was a city Eva in [518]Arcadia: and another in [519]Macedonia. There was also a mountain Eva, or Evan, taken notice of by [520]Pausanias, between which and Ithome lay the city Messene. He mentions also an Eva in [521]Argolis, and speaks of it as a large town. Another name for a serpent, of which I have as yet taken no notice, was Patan, or Pitan. Many places in different parts were denominated from this term. Among others was a city in [522]Laconia; and another in [523]Mysia, which Stephanus styles a city of Æolia. They were undoubtedly so named from the worship of the serpent, Pitan: and had probably Dracontia, where were figures and devices relative to the religion which prevailed. Ovid mentions the latter city, and has some allusions to its antient history, when he describes Medea as flying through the air from Attica to Colchis.

[524]Æoliam Pitanem lævâ de parte relinquit,

Factaque de saxo longi simulacra Draconis.

The city was situated upon the river Eva or Evan, which the Greeks rendered [525]Evenus. It is remarkable, that the Opici, who are said to have been denominated from serpents, had also the name of Pitanatæ: at least one part of that family were so called. [526]Τινας δε και Πιτανατας λεγεσθαι. Pitanatæ is a term of the same purport as Opici, and relates to the votaries of Pitan, the serpent Deity, which was adored by that people.

Menelaus was of old styled [527]Pitanates, as we learn from Hesychius: and the reason of it may be known from his being a Spartan, by which was intimated one of the serpentigenæ, or Ophites. Hence he was represented with a serpent for a device upon his shield. It is said that a brigade, or portion of infantry, was among some of the Greeks named [528]Pitanates; and the soldiers, in consequence of it, must have been termed Pitanatæ: undoubtedly, because they had the Pitan, or serpent, for their [529]standard. Analogous to this, among other nations, there were soldiers called [530]Draconarii. I believe, that in most countries the military standard was an emblem of the Deity there worshipped.

From what has been said, I hope, that I have thrown some light upon the history of this primitive idolatry: and have moreover shewn, that wherever any of these Ophite colonies settled they left behind from their rites and institutes, as well as from the names, which they bequeathed to places, ample memorials, by which they may be clearly traced out. It may seem strange, that in the first ages there should have been such an universal defection from the truth; and above all things such a propensity to this particular mode of worship, this mysterious attachment to the serpent. What is scarce credible, it obtained among Christians; and one of the most early heresies in the church was of this sort, introduced by a sect, called by [531]Epiphanius Ophitæ, by [532]Clemens of Alexandria Ophiani. They are particularly described by Tertullian, whose account of them is well worth our notice. [533]Accesserunt his Hæretici etiam illi, qui Ophitæ nuncupantur: nam serpentem magnificant in tantum, ut illum etiam ipsi Christo præferant. Ipse enim, inquiunt, scientiæ nobis boni et mali originem dedit. Hujus animadvertens potentiam et majestatem Moyses æreum posuit serpentem: et quicunque in eum aspexerunt, sanitatem consecuti sunt. Ipse, aiunt, præterea in Evangelio imitatur serpentis ipsius sacram potestatem, dicendo, et sicut Moyses exaltavit serpentem in deserto, ita exaltari oportet filium hominis. Ipsum introducunt ad benedicenda Eucharistia sua. In the above we see plainly the perverseness of human wit, which deviates so industriously; and is ever after employed in finding expedients to countenance error, and render apostasy plausible. It would be a noble undertaking, and very edifying in its consequences, if some person of true learning, and a deep insight into antiquity, would go through with the history of the [534]serpent. I have adopted it, as far as it relates to my system, which is, in some degree, illustrated by it.

[385] 2 Kings. c. 23. v. 10. 2 Chron. c. 28. v. 3.

[386] C. 7. v. 31. and c. 19. v. 5. There was a place named Tophel (Toph-El) near Paran upon the Red Sea. Deuteron. c. 1. v. 1.

[387] Zonar. vol. 2. p. 227. Τουφαν καλει ὁ δημωδης και πολυς ανθρωπος.

[388] Bedæ. Hist. Angliæ. l. 2. c. 16.

[389] De legibus specialibus. p. 320.

The Greek term τυφος, fumus, vel fastus, will hardly make sense, as introduced here.

[390] Plutarch. Isis et Osiris. v. 1. p. 359.

[391] Virgil. Æn. l. 2. v. 713.

[392] Την ταφην (Διονυσου) ειναι φασιν εν Δελφοις παρα τον Χρυσουν Απολλωνα. Cyril. cont. Julian. l. 1. p. 11.

[393] Callimach. Hymn. in Jovem. v. 8.

Ὡδε μεγας κειται Ζαν, ὁν Δια κικλησκουσι.

Porphyr. Vita Pythagoræ. p. 20.

[394] Hence Hercules was styled Τριεσπερος. Lycoph. v. 33.

Ζευς τρεις ἑσπερας εις μιαν μεταβαλων συνεκαθευδε τῃ Αλκμηνῃ. Schol. ibid.

[395] Abbe Banier. Mythology of the Antients explained. vol. 4. b. 3. c. 6. p. 77, 78. Translation.

[396] Plaut. Amphitryo. Act. 1. s. 3.

[397] Cicero de Nat. Deor. l. 1. c. 42.

Αλλα και ταφον αυτου (Ζηνος) δεικνυουσι. Lucian. de Sacrificiis. v. 1. p. 355.

[398] Maximus Tyrius. Dissert. 38. p. 85.

[399] Clementis Cohort. p. 40.

[400] Arnobius contra Gentes. l. 4. p. 135. Clem. Alexand. Cohort. p. 24.

[401] Tertullian. Apolog. c. 14.

Πευσομαι δε σου κᾳ 'γω, ω ανθρωπε, ποσοι Ζηνες ἑυρισκονται. Theoph. ad Autolyc. l. 1. p. 344.

[402] Newton's Chronology. p. 151.

[403] Pezron. Antiquities of nations. c. 10, 11, 12.

[404] Virgil. Æn. l. 7. v. 48.

[405] Sir Isaac Newton supposes Jupiter to have lived after the division of the kingdoms in Israel; Pezron makes him antecedent to the birth of Abraham, and even before the Assyrian monarchy.

[406] Arnobius has a very just observation to this purpose. Omnes Dii non sunt: quoniam plures sub eodem nomine, quemadmodum accepimus, esse non possunt, &c. l. 4. p. 136.

[407] Antiquus Auctor Euhemerus, qui fuit ex civitate Messene, res gestas Jovis, et cæterorum, qui Dii putantur, collegit; historiamque contexuit ex titulis, et inscriptionibus sacris, quæ in antiquissimis templis habebantur; maximeque in fano Jovis Triphylii, ubi auream columnam positam esse ab ipso Jove titulus indicabat. In quâ columnâ gesta sua perscripsit, ut monumentum esset posteris rerum suarum. Lactant. de Falsâ Relig. l. 1. c. 11. p. 50.

(Euhemerus), quem noster et interpretatus, et secutus est præter cæteros, Ennius. Cicero de Nat. Deor. l. 1. c. 42.

[408] Lactantius de Falsâ Relig. l. 1. c. 11. p. 52.

[409] Varro apud Solinum. c. 16.

[410] Epiphanius in Ancorato. p. 108.

Cyril. contra Julianum. l. 10. p. 342. See Scholia upon Lycophron. v. 1194.

[411] Callimach. Hymn. in Jovem. v. 6.

[412] Ταφον θεας αξιον. Pausan. l. 2. p. 161.

[413] Diodor. Sicul. l. 1. p. 23. Ταφηναι λεγουσι την Ισιν εν Μεμφει.

Osiris buried at Memphis, and at Nusa. Diodorus above. Also at Byblus in Phenicia.

Εισι δε ενιοι Βυβλιων, ὁι λεγουσι παρα σφισι τεθαφθαι τον Οσιριν τον Αιγυπτιον. Lucian. de Syriâ Deâ. v. 2. p. 879.

Τα μεν ουν περι της ταφης των Θεων τουτων διαφωνειται παρα τοις πλειστοις. Diodor. l. 1. p. 24.

[414] Procopius περι κτισματων. l. 6. c. 1. p. 109.

Αιγυπτιοι τε γαρ Οσιριδος πολλαχου θηκας, ὡσπερ ειρηται, δεικνυουσι. Plutarch. Isis et Osiris. p. 358. He mentions πολλους Οσιριδος ταφους εν Αιγυπτῳ. Ibid. p. 359.

[415] L. 1. p. 79. Περι της Βουσιριδος ξενοκτονιας παρα τοις Ἑλλησιν ενισχυσαι τον μυθον· ου του Βασιλεως ονομαζομενου Βουσιριδος, αλλα του Οσιριδος ταφου ταυτην εχοντος την προσηγοριαν κατα την των εγχωριων διαλεκτον. Strabo likewise says, that there was no such king as Busiris. l. 17. p. 1154.

[416] Bou-Sehor and Uch-Sehor are precisely of the same purport, and signify the great Lord of day.

[417] Pausanias. l. 2. p. 144.

[418] Altis, Baaltis, Orontis, Opheltis, are all places compounded with some title, or titles, of the Deity.

[419] 2 Chron. c. 33. v. 14.

[420] 2 Chron. c. 27. v. 3. On the wall (חומת) of Ophel he built much: or rather on the Comah, or sacred hill of the Sun, called Oph-El, he built much.

[421] Apollon. Rhodii Argonaut. l. 2. v. 709. Apollo is said to have killed Tityus, Βουπαις εων. Apollon. l. 1. v. 760.

[422] Τον δε του Αιπυτου ταφον σπουδῃ μαλιστα εθεασαμην—εστι μεν ουν γης χωμα ου μεγα, λιθου κρηπιδι εν κυκλῳ περιεχομενον. Pausan. l. 8. p. 632.

Αιπυτιον τυμβον, celebrated by Homer. Iliad. β. v. 605.

Αιπυτος, supposed to be the same as Hermes. Ναος Ἑρμου Αιπυτου near Tegea in Arcadia. Pausan. l. 8. p. 696. Part of Arcadia was called Αιπυτις.

[423] Clemens Alexand. Cohort. p. 11. Ανεστεμμενοι τοις οφεσιν επολολυζοντες Ευαν, Ευαν κτλ.

[424] Porphyrii Vita Pythagoræ.

[425] Clement. Alexand. Cohort. p. 29.

[426] The Scholiast upon Pindar seems to attribute the whole to Dionusus, who first gave out oracles at this place, and appointed the seventh day a festival. Εν ᾡ πρωτος Διονυσος εθεμιστευσε, και αποκτεινας τον Οφιν τον Πυθωνα, αγωνιζεται τον Πυθικον αγωνα κατα Ἑβδομην ἡμεραν. Prolegomena in Pind. Pyth. p. 185.

[427] Pausanias. l. 9. p. 749.

[428] Ibid. l. 2. p. 155.

[429] Strabo. l. 9. p. 651.

[430] Ibid.

[431] Pausanias. l. 5. p. 376.

[432] Ibid. l. 10. p. 806.

[433] Ibid. l. 1. p. 87.

[434] At Patræ, μνημα Αιγυπτιου του Βηλου. Pausan. l. 7. p. 578.

[435] Pausanias. l. 2. p. 179.

[436] Herodotus. l. 7. c. 150. and l. 6. c. 54.

Plato in Alcibiad. 1^{mo}. vol. 2. p. 120.

Upon Mount Mænalus was said to have been the tomb of Arcas, who was the father of the Arcadians.

Εστι δε Μαιναλιη δυσχειμερος, ενθα τε κειται

Αρχας, αφ' ὁυ δη παντες επικλησιν καλεονται.

Oraculum apud Pausan. l. 8. p. 616.

But what this supposed tomb really was, may be known from the same author: Το δε χωριον τουτο, ενθα ὁ ταφος εστι του Αρκαδος, καλουσιν Ἡλιου Βωμους. Ibid.

Ταφος, η τυμβος, η σημειον.. Hesych.

[437] Strabo. l. 11. p. 779. Εν δε τῳ πεδιῳ ΠΕΤΡΑΝ ΤΙΝΑ προσχωματι συμπληρωσαντες εις βουνοειδες σχημα κτλ.

[438] Typhon was originally called Γηγενης, and by Hyginus Terræ Filius. Fab. 152. p. 263. Diodorus. l. 1. p. 79. he is styled Γης ὑιος εξαισιος. Antoninus Liberal. c. 25.

[439] Plutarch. Isis et Osiris. p. 380.

[440] Josephus contra Apion. l. 1. p. 460.

[441] Porphyry de Abstinen. l. 2. p. 223.

There was Πετρα Τυφαονια in Caucasus. Etymolog. Magnum. Τιφως· Τυφαονια Πετρα εστιν ὑψηλη εν Καυκασῳ.

Καυκασου εν κνημοισι, Τυφαονιη ὁτι Πετρη. Apollon. l. 2. v. 1214.

[442] Diodorus Sicul. l. 1. p. 79.

[443] Παρηγορουσι θυσιαις και πραϋνουσι (τον Τυφωνα), Plutarch. Isis et Osiris. p. 362.

[444] Diodorus Sicul. l. 5. p. 338.

[445] Plutarch. Isis et Osiris. p. 362. Ισαιακου του Ἡρακλεους ὁ Τυφων.

[446] Ovid. Metamorph. l. 11. v. 762.

[447] Ενιοι δε ὑπο του Τυφωνος, ὑπο δε Ατλαντος Ξεναγορας ειρηκεν. Schol. Apollon. l. 4. v. 264.

[448] Hesiod. Theogon. v. 824.

[449] Ibid. v. 826. Typhis, Typhon, Typhaon, Typhœus, are all of the same purport.

[450] Nonni Dionys. l. 1. p. 24.

[451] Οφεις—τιμᾳσθαι ισχυρως. Philarchus apud Ælian: de Animal. l. 17. c. 5.

[452] See Justin Martyr above.

Σημειον Οργιων Βακχικων Οφις εστι τετελεσμενος. Clemens Alexand. Cohort. p. 11. See Augustinus de Civitate Dei. l. 3. c. 12. and l. 18. c. 15.

[453] Ανεστεμμενοι τοις οφεσιν. Clemens above.

[454] In mysteriis, quibus Sabadiis nomen est, aureus coluber in sinum dimittitur consecratis, et eximitur rursus ab inferioribus partibus. Arnobius. l. 5. p. 171. See also Clemens, Cohort. p. 14. Δρακων διελκομενος του κολπου. κ. λ.

Sebazium colentes Jovem anguem, cum initiantur, per sinum ducunt. Julius Firmicus. p. 23. Σαβαζιος, επωνυμον Διονυσου. Hesych.

[455] Τους Οφεις ανεστεμμενοι, ευαζοντες το Ουα, Ουα, εκεινην την Ευαν ετι, την δια του Οφεως απατηθεισαν, επικαλουμενοι. Epiphanius. tom. 2. l. 3. p. 1092.

[456] Cohortatio. p. 11.

[457] Ibid.

[458] Plutarch. Alexander. p. 665.

[459] Οφεις μεγαλους χειροηθεις εφειλκετο τοις θιασοις (ἡ Ολυμπιας), ὁι πολλακις εκ του κιττου και των μυστικων λικνων παραναδυομενοι, και περιελιττομενοι θυρσοις των γυναικων, και τοις στεφανοις, εξεπληττον τους ανδρας. Plutarch. ibid.

[460] Τους οφεις τους Παρειας θλιβων, και ὑπερ της κεφαλης αιωρων, και βοων, Ευοι, Σαβοι, και επορχουμενος Yης Αττης, Αττης Yης. Demosth. Περι στεφανου. p. 516.

[461] Hesych.

[462] Της Ισιδος αγαλματα ανεδουσι ταυτῃ, ὡς τινι διαδηματι βασιλειῳ. Ælian. Hist. Animal. l. 10. c. 31.

[463] Τους Βασιλεις—χρησθαι πιλοις μακροις επι του περατος ομφαλον εχουσι, και περιεσπειραμενοις οφεσι, ὁυς καλουσιν ασπιδας. l. 3. p. 145.

[464] Priscian. l. 5. and l. 6.

[465] Pausan. l. 10. p. 859.

[466] Bochart supposes this term to signify a father, and the purport of the name to be Pater magnificus. He has afterwards a secondary derivation. Sed fallor, aut Abdir, vel Abadir, cum pro lapide sumitur, corruptum ex Phoenicio Eben-Dir, lapis sphæricus. Geog. Sac. l. 2. c. 2. p. 708.

[467] See Radicals. p. 59. and Deuteronomy. c. 18. v. 11.

[468] Εχουσαι βασιλεα εφ' ἁντων τον Αγγελον της Αβυσσου· ονομα αυτῳ Ἑβραϊστι Αβαδδων, εν δε τη Ἑλληνικῃ ονομα εχει Απολλυων. Revelations. c. 20. v. 11.

[469] Revelations. c. 20. v. 2. Abadon signifies serpens Dominus, vel Serpens Dominus Sol.

[470] Daniel Heinsius. Aristarchus. p. 11.

[471] Euseb. P. E. l. 1. p. 41, 42.

[472] Euseb. ibidem. Ταδε αυτα και Οστανης κτλ.

[473] Herod. l. 2. c. 189. also Ptolemy.

[474] M. Maimonides in more Nevochim. See Selden de Diis Syris. Synt. 1. c. 3. p. 49.

[475] Ουβαιον, ὁ εστιν Ἑλληνιστι Βασιλισκον· ὁνπερ χρυσουν ποιουντες Θεοις περιτιθεασιν. Horapollo. l. 1. p. 2.

Ουβαιον is so corrected for Ουραιον, from MSS. by J. Corn. De Pauw.

[476] Cicero de Nat. Deor. l. 3.

[477] Præp. Evan. l. 1. p. 41.

[478] Euseb. supra.

[479] L. 6. p. 345.

[480] Strabo. l. 10. p. 683. It was supposed to have had its name from Ellops, the Son of Ion, who was the brother of Cothus.

[481] Callimachus. H. in Delon. v. 292. Ευαιων, Eva-On, Serpens Sol.

[482] Athenagoras. Legatio. p. 294. Ηρακλης Χρονος.

[483] Athenag. p. 295. Ἡρακλης Θεος—δρακων ἑλικτος.

[484] It is said to have been named Rhodus from Rhod, a Syriac for a serpent. Bochart. G. S. p. 369.

[485] Ενταυθα μυθυουσι τους Οφιογενεις συγγενειαν τινα εχειν προς τους οφεις. Strabo. l. 13. p. 850. Ophiogenæ in Hellesponto circa Parium. Pliny. l. 7. p. 371.

[486] Pausan. l. 8. p. 614.

[487] Aristoph. Plutus. Schol. v. 718.

[488] L. 3. c. 96. Strabo. l. 10. p. 692.

[489] Steph. Byzant. Παταρα.

[490] Βη δ' επ' εραν Διας φευγων οφιωδεα Κυπρον. Parthenius. See Vossius upon Pomp. Mela. l. 1. c. 6. p. 391.

Ovid Metamorph. l. 10. v. 229. Cypri arva Ophiusia.

[491] They were particularly to be found at Paphos. Apollon. Discolus. Mirabil. c. 39. Οφις ποδας εχων δυο.

[492] Herodotus. l. 7. c. 90. Ὁι δε απο Αιθιοπιης, ὡς αυτοι Κυπριοι λεγουσι.

[493] Ὁ γαρ Μινως οφεις, και σκορπιους, και σκολοπενδρας ουρεσκεν κλ. Antonin. Liberalis. c. 41. p. 202. See notes, p. 276.

[494] Tacitus. Annal. l. 4. c. 21.

[495] In Ceiri.

[496] Strabo. l. 10. p. 746.

[497] What the Greeks rendered Σεριφος was properly Sar-Iph; and Sar-Iphis, the same as Ophis: which signified Petra Serpentis, sive Pythonis.

[498] Herodotus. l. 8. c. 41.

[499] Strabo. l. 9. p. 603.

[500] Lycophron Scholia. v. 496. απο των οδοντων του δρακοντος.

[501] Meursius de reg. Athen. l. 1. c. 6.

[502] Apollodorus. l. 3. p. 191.

[503] Diodorus. l. I. p. 25. Cecrops is not by name mentioned in this passage according to the present copies: yet what is said, certainly relates to him, as appears by the context, and it is so understood by the learned Marsham. See Chron. Canon. p. 108.

[504] Eustat. on Dionys. p. 56. Edit. Steph.

[505] Τον βαρβαρον Αιγυπτιασμον αφεις. κτλ. ibid.

See also Tzetzes upon Lycophron. v. 111.

[506] Chron. Canon, p. 109.

[507] It may not perhaps be easy to decypher the name of Cecrops: but thus much is apparent, that it is compounded of Ops, and Opis, and related to his symbolical character.

[508] Δρακοντας δυο περι τον Ερικθονιον. Antigonus Carystius. c. 12.

[509] Aristot. de Mirabilibus. vol. 2. p. 717.

[510] Pliny. l. 3. p. 153. l. 8. p. 455.

[511] Æschyli Supplices. p. 516.

[512] L. 3. p. 184.

[513] Apollonius Discolus. c. 12. and Aristot. de Mirabilibus, vol. 2. p. 737.

[514] Aves Diomedis—judicant inter suos et advenas, &c. Isidorus Orig. l. 12. c. 7. Pliny. l. 10. c. 44.

[515] Apollodorus. l. 1. p. 37.

[516] Stephanas Byzant. Οπικοι.

[517] The same is said by Epiphanius. Ἑυια τον οφιν παιδες Ἑβραιων ονομαζουσι. Epiphanius advers. Hæres. l. 3. tom. 2. p. 1092.

[518] Steph. Byzant.

[519] Ptolemy. p. 93. Ευια.

[520] Pausanias. l. 4. p. 356.

[521] L. 2. p. 202.

[522] Pausan. l. 3. p. 249.

[523] There was a city of this name in Macedonia, and in Troas. Also a river.

[524] Ovid Metamorph. l. 7. v. 357.

[525] Strabo. l. 13. p. 913. It is compounded of Eva-Ain, the fountain, or river of Eva, the serpent.

[526] Strabo. l. 5. p. 383.

[527] Μενελαον, ὁς ην Πιτανατης. Hesych.

Δρακων επι τῃ ασπιδι (Μενελαου) εστιν ειργασμενος. Pausan. l. 10. p. 863.

[528] Πιτανατης, λοχος. Hesych.

[529] It was the insigne of many countries. Textilis Anguis

Discurrit per utramque aciem. Sidon. Apollinaris. Carm. 5. v. 409.

Stent bellatrices Aquilæ, sævique Dracones.

Claudian de Nuptiis Honor. et Mariæ. v. 193.

Ut primum vestras Aquilas Provincia vidit,

Desiit hostiles confestim horrere Dracones.

Sidon. Apollinaris. Carm. 2. v. 235.

[531] Epiphanius Hæres. 37. p. 267.

[532] Clemens. l. 7. p. 900.

[533] Tertullian de Præscript. Hæret. c. 47. p. 221.

[534] Vossius, Selden, and many learned men have touched upon this subject. There is a treatise of Philip Olearius de Ophiolatriâ. Also Dissertatio Theologico-Historico, &c. &c. de cultu serpentum. Auctore M. Johan. Christian. Kock. Lipsiæ. 1717.

Index | Next: Cuclopes or Cyclopes