A New System; or, an Analysis of Ancient Mythology. Volume II

By Jacob Bryant

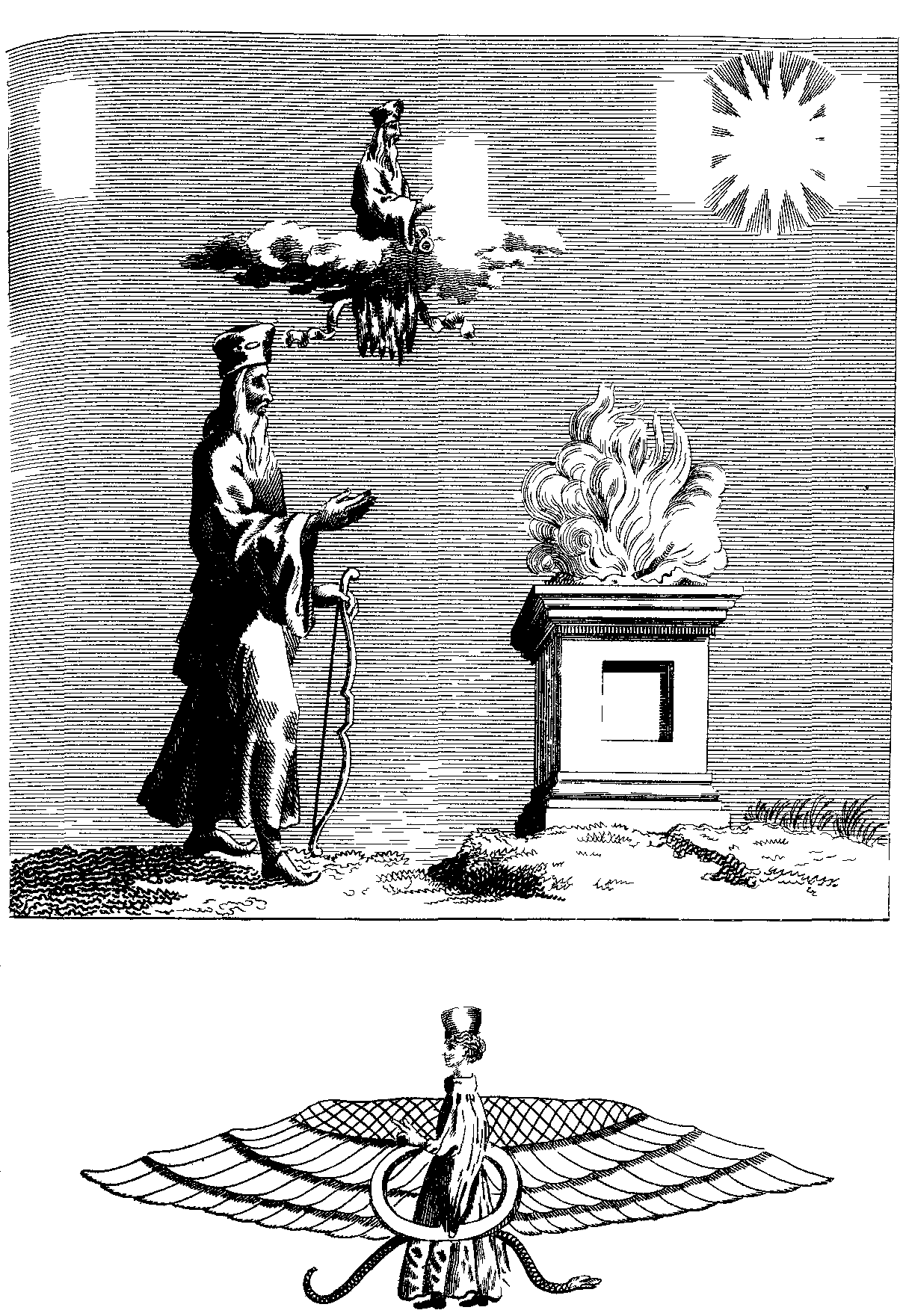

ZOROASTER.

The celebrated Zoroaster seems to have been a personage as much mistaken, as any, who have preceded. The antients, who treated of him, have described him in the same foreign light, as they have represented Perseus, Dionusus, and Osiris. They have formed a character, which by length of time has been separated, and estranged, from the person, to whom it originally belonged. And as among the antients, there was not a proper uniformity observed in the appropriation of terms, we shall find more persons than one spoken of under the character of Zoroaster: though there was one principal, to whom it more truly related. It will be found, that not only the person originally recorded, and reverenced; but others, by whom the rites were instituted and propagated, and by whom they were in aftertimes renewed, have been mentioned under this title: Priests being often denominated from the Deity, whom they served.

Of men, styled Zoroaster, the first was a deified personage, reverenced by some of his posterity, whose worship was styled Magia, and the professors of it Magi. His history is therefore to be looked for among the accounts transmitted by the antient Babylonians, and Chaldeans. They were the first people styled Magi; and the institutors of those rites, which related to Zoroaster. From them this worship was imparted to the Persians, who likewise had their Magi. And when the Babylonians sunk into a more complicated idolatry, the Persians, who succeeded to the sovereignty of Asia, renewed under their Princes, and particularly under Darius, the son of Hystaspes, these rites, which had been, in a great degree, effaced, and forgotten. That king was devoted to the religion styled Magia[936]; and looked upon it as one of his most honourable titles, to be called a professor of those doctrines. The Persians were originally named Peresians, from the Deity Perez, or Parez the Sun; whom they also worshipped under the title of [937]Zor-Aster. They were at different æras greatly distressed and persecuted, especially upon the death of their last king Yesdegerd. Upon this account they retired into Gedrosia and India; where people of the same family had for ages resided. They carried with them some shattered memorials of their religion in writing, from whence the Sadder, Shaster, Vedam, and Zandavasta were compiled. These memorials seem to have been taken from antient symbols ill understood; and all that remains of them consists of extravagant allegories and fables, of which but little now can be decyphered. Upon these traditions the religion of the Brahmins and Persees is founded.

The person who is supposed to have first formed a code of institutes for this people, is said to have been one of the Magi, named Zerdusht. I mention this, because Hyde, and other learned men, have imagined this Zerdusht to have been the antient Zoroaster. They have gone so far as to suppose the two names to have been the [938]same; between which I can scarce descry any resemblance. There seem to have been many persons styled Zoroaster: so that if the name had casually retained any affinity, or if it had been literally the same, yet it would not follow, that this Persic and Indian Theologist was the person of whom antiquity speaks so loudly. We read of persons of this name in different parts of the world, who were all of them Magi, or Priests, and denominated from the rites of Zoroaster, which they followed. Suidas mentions a Zoroaster, whom he styles an Assyrian; and another whom he calls Περσο-Μηδης, Perso-Medes: and describes them both as great in science. There was a Zoroaster Proconnesius, in the time of Xerxes, spoken of by [939]Pliny. Arnobius mentions Zoroastres Bactrianus: and Zoroastres Zostriani nepos [940]Armenius. Clemens Alexandrinus takes notice of Zoroaster [941]Medus, who is probably the same as the Perso-Medes of Suidas. Zoroastres Armenius is likewise mentioned by him, but is styled the son of [942]Armenius, and a Pamphylian. It is said of him that he had a renewal of life: and that during the term that he was in a state of death, he learned many things of the Gods. This was a piece of mythology, which I imagine did not relate to the Pamphylian Magus, but to the head of all the Magi, who was reverenced and worshipped by them. There was another styled a Persian, whom Pythagoras is said to have [943]visited. Justin takes notice of the Bactrian [944]Zoroaster, whom he places in the time of Ninus. He is also mentioned by [945]Cephalion, who speaks of his birth, and the birth of Semiramis (γενεσιν Σεμιραμεως και Ζωροαστρου Μαγου) as of the same date. The natives of India have a notion of a Zoroaster, who was of Chinese original, as we are informed by [946]Hyde. This learned man supposes all these personages, the Mede, the Medo-Persic, the Proconnesian, the Bactrian, the Pamphylian, &c. to have been one and the same. This is very wonderful; as they are by their history apparently different. He moreover adds, that however people may differ about the origin of this person, yet all are unanimous about the time when he [947]lived. To see that these could not all be the same person, we need only to cast our eye back upon the evidence which has been collected above: and it will be equally certain, that they could not be all of the same æra. There are many specified in history; but we may perceive, that there was one person more antient and celebrated than the rest; whose history has been confounded with that of others who came after him. This is a circumstance which has been observed by [948]many: but this ingenious writer unfortunately opposes all who have written upon the subject, however determinately they may have expressed themselves. [949]At quicquid dixerint, ille (Zoroaster) fuit tantum unus, isque tempore Darii Hystaspis: nec ejus nomine plures unquam extitere. It is to be observed, that the person, whom he styles Zoroaster, was one Zerdusht. He lived, it seems, in the reign of Darius, the father of Xerxes; which was about the time of the battle of Marathon: consequently not a century before the birth of Eudoxus, Xenophon, and Plato. We have therefore no authority to suppose [950]this Zerdusht to have been the famous Zoroaster. He was apparently the renewer of the Sabian rites: and we may be assured, that he could not be the person so celebrated by the antients, who was referred to the first ages. Hyde asserts, that all writers agree about the time, when Zoroaster made his appearance: and he places him, as we have seen above, in the reign of Darius. But Xanthus Lydius made him above [951]six hundred years prior. And [952]Suidas from some anonymous author places him five hundred years before the war of Troy. Hermodorus Platonicus went much farther, and made him five thousand years before that [953]æra. Hermippus, who professedly wrote of his doctrines, supposed him to have been of the same [954]antiquity. Plutarch also [955]concurs, and allows him five thousand years before that war. Eudoxus, who was a consummate philosopher, and a great traveller, supposed him to have flourished six thousand years before the death of [956]Plato. Moses [957]Chorenensis, and [958]Cephalion, make him only contemporary with Ninus, and Semiramis: but even this removes him very far from the reign of Darius. Pliny goes beyond them all; and places him many thousand years before Moses. [959]Est et alia Magices factio, a Mose, et Jamne, et Lotapea Judæis pendens: sed multis millibus annorum post Zoroastrem. The numbers in all these authors, are extravagant: but so much we may learn from them, that they relate to a person of the highest antiquity. And the purport of the original writers, from whence the Grecians borrowed their evidence, was undoubtedly to shew, that the person spoken of lived at the extent of time; at the commencement of all historical data. No fact, no memorial upon record, is placed so high as they have carried this personage. Had Zoroaster been no earlier than Darius, Eudoxus would never have advanced him to this degree of antiquity. This writer was at the same distance from Darius, as Plato, of whom he speaks: and it is not to be believed, that he could be so ignorant, as not to distinguish between a century, and six thousand years. Agathias indeed mentions, that some of the Persians had a notion, that he flourished in the time of one Hystaspes; but he confesses, that who the Hystaspes was, and at what time he lived, was [960]uncertain. Aristotle wrote not long after Eudoxus, when the history of the Persians was more known to the Grecians, and he allots the same number of years between Zoroaster and Plato, as had been [961]before given. These accounts are for the most part carried too far; but at the same time, they fully ascertain the high antiquity of this person, whose æra is in question. It is plain that these writers in general extend the time of his life to the æra of the world, according to their estimation; and make it prior to Inachus, and Phoroneus, and Ægialeus of Sicyon.

Huetius takes notice of the various accounts in respect to his country. [962]Zoroastrem nunc Persam, nunc Medum ponit Clemens Alexandrinus; Persomedum Suidas; plerique Bactrianuni; alii Æthiopem, quos inter ait Arnobius ex Æthiopiâ interiore per igneam Zonam venisse Zoroastrem. In short, they have supposed a Zoroaster, wherever there was a Zoroastrian: that is, wherever the religion of the Magi was adopted, or revived. Many were called after him: but who among men was the Prototype can only be found out by diligently collating the histories, which have been transmitted. I mention among men; for the title originally belonged to the Sun; but was metaphorically bestowed upon sacred and enlightened personages. Some have thought that the person alluded to was Ham. He has by others been taken for Chus, also for Mizraim, and [963]Nimrod: and by Huetius for Moses. It may be worth while to consider the primitive character, as given by different writers. He was esteemed the first observer of the heavens; and it is said that the antient Babylonians received their knowledge in Astronomy from him: which was afterwards revived under Ostanes; and from them it was derived to the [964]Egyptians, and to the Greeks. Zoroaster was looked upon as the head of all those, who are supposed to have followed his [965]institutes: consequently he must have been prior to the Magi, and Magia, the priests, and worship, which were derived from him. Of what antiquity they were, may be learned from Aristotle. [966]Αριστοτελης δ' εν πρωτῳ περι φιλοσοφιας (τους Μαγους) και πρεσβυτερους ειναι των Αιγυπτιων. The Magi, according to Aristotle, were prior even to the Egyptians: and with the antiquity of the Egyptians, we are well acquainted. Plato styles him the son of [967]Oromazes, who was the chief Deity of the Persians: and it is said of him, that he laughed upon the day on which he was [968]born. By this I imagine, that something fortunate was supposed to be portended: some indication, that the child would prove a blessing to the world. In his childhood he is said to have been under the care of [969]Azonaces: which I should imagine was a name of the chief Deity Oromazes, his reputed father. He was in process of time greatly enriched with knowledge, and became in high repute for his [970]piety, and justice. He first sacrificed to the Gods, and taught men to do the [971]same. He likewise instructed them in science, for which he was greatly [972]famed: and was the first who gave them laws. The Babylonians seem to have referred to him every thing, which by the Egyptians was attributed to Thoth and Hermes. He had the title of [973]Zarades, which signifies the Lord of light, and is equivalent to Orus, Oromanes, and Osiris, It was sometimes expressed [974]Zar-Atis, and supposed to belong to a feminine Deity of the Persians. Moses Chorenensis styles him [975]Zarovanus, and speaks of him as the father of the Gods. Plutarch would insinuate, that he was author of the doctrine, embraced afterwards by the Manicheans, concerning two prevailing principles, the one good, and the other evil[976]: the former of these was named Oromazes, the latter Areimanius. But these notions were of late [977]date, in comparison of the antiquity which is attributed to [978]Zoroaster. If we might credit what was delivered in the writings transmitted under his name, which were probably composed by some of the later Magi, they would afford us a much higher notion of his doctrines. Or if the account given by Ostanes were genuine, it would prove, that there had been a true notion of the Deity transmitted from [979]Zoroaster, and kept up by the Magi, when the rest of the gentile world was in darkness. But this was by no means true. It is said of Zoroaster, that he had a renewal of [980]life: for I apply to the original person of the name, what was attributed to the Magus of Pamphylia: and it is related of him, that while he was in the intermediate state of death, he was instructed by the [981]Gods. Some speak of his retiring to a mountain of Armenia, where he had an intercourse with the [982]Deity: and when the mountain burned with fire, he was preserved unhurt. The place to which he retired, according to the Persic writers, was in the region called [983]Adarbain; where in aftertimes was the greatest Puratheion in Asia. This region was in Armenia: and some make him to have been born in the same country, upon one of the Gordiæan [984]mountains. Here it was, that he first instituted sacrifices, and gave laws to his followers; which laws are supposed to be contained in the sacred book named Zandavasta. To him has been attributed the invention of Magic; which notion has arisen from a misapplication of terms. The Magi Were priests, and they called religion in general Magia. They, and their rites, grew into disrepute; in consequence of which they were by the Greeks called απατεωνες, φαρμακευται: jugglers, and conjurers. But the Persians of old esteemed them very highly. [985]Μαγον, τον θεοσεβη, και θεολογον, και ἱερεα, ὁι Περσαι ὁυτως λεγουσιν. By a Magus, the Persians understand a sacred person, a professor of theology, and a Priest. Παρα Περσαις [986]Μαγοι ὁι φιλοσοφοι, και θεοφιλοι. Among the Persians, the Magi are persons addicted to philosophy, and to the worship of the Deity. [987]Dion. Chrysostom, and Porphyry speak to the same purpose. By Zoroaster being the author of Magia, is meant, that he was the first promoter of religious rites, and the instructor of men in their duty to God. The war of Ninus with Zoroaster of Bactria relates probably to some hostilities carried on between the Ninevites of Assyria, and the Bactrians, who had embraced the Zoroastrian rites. Their priest, or prince, for they were of old the same, was named [988]Oxuartes; but from his office had the title of Zoroaster; which was properly the name of the Sun, whom he adored. This religion began in Chaldea; and it is expressly said of this Bactrian king, that he borrowed the knowledge of it from that country, and added to it largely. [989]Cujus scientiæ sæculis priscis multa ex Chaldæorum arcanis Bactrianus addidit Zoroastres. When the Persians gained the empire in Asia, they renewed these rites, and doctrines. [990]Multa deinde (addidit) Hystaspes Rex prudentissimus, Darii pater. These rites were idolatrous; yet not so totally depraved, and gross, as those of other nations. They were introduced by Chus; at least by the Cuthites: one branch of whom were the Peresians, or Persians. The Cuthites of Chaldea were the original Magi, and they gave to Chus the title of Zoroaster Magus, as being the first of the order. Hence the account given by Gregorius Turonensis is in a great degree true. [991]Primogeniti Cham filii Noë fuit Chus. Hic ad Persas transiit, quem Persæ vocitavere Zoroastrem. Chus, we find, was called by this title; and from him the religion styled Magia passed to the Persians. But titles, as I have shewn, were not always determinately appropriated: nor was Chus the original person, who was called Zoroaster. There was another beyond him, who was the first deified mortal, and the prototype in this worship. To whom I allude, may, I think, be known from the history given above. It will not fail of being rendered very clear in the course of my procedure.

The purport of the term Zoroaster is said, by [992]the author of the Recognitions, and by others, to be the living star: and they speak of it as if it were of Grecian etymology, and from the words ζωον and αστηρ. It is certainly compounded of Aster, which, among many nations, signified a star. But, in respect to the former term, as the object of the Persic and Chaldaic worship was the Sun, and most of their titles were derived from thence; we may be pretty certain, that by Zoro-Aster was meant Sol Asterius. Zor, Sor, Sur, Sehor, among the Amonians, always related to the Sun. Eusebius says, that Osiris was esteemed the same as Dionusus, and the Sun: and that he was called [993]Surius. The region of Syria was hence denominated Συρια; and is at this day called Souria, from Sur, and Sehor, the Sun. The Dea Syria at Hierapolis was properly Dea Solaris. In consequence of the Sun's being called Sor, and Sur, we find that his temple is often mentioned under the name of [994]Beth-Sur, and [995]Beth-Sura, which Josephus renders [996]Βηθ-Σουρ. It was also called Beth-Sor, and Beth-Soron, as we learn from [997]Eusebius, and [998]Jerome. That Suria was not merely a provincial title is plain, from the Suria Dea being worshipped at Erix in [999]Sicily; and from an inscription to her at [1000]Rome. She was worshipped under the same title in Britain, as we may infer from an Inscription at Sir Robert Cotton's, of Connington, in Cambridgeshire.

[1001]DEÆ

SURIÆ

SUB CALPURNIO

LEG. AUG. &c.

Syria is called Sour, and Souristan, at this day.

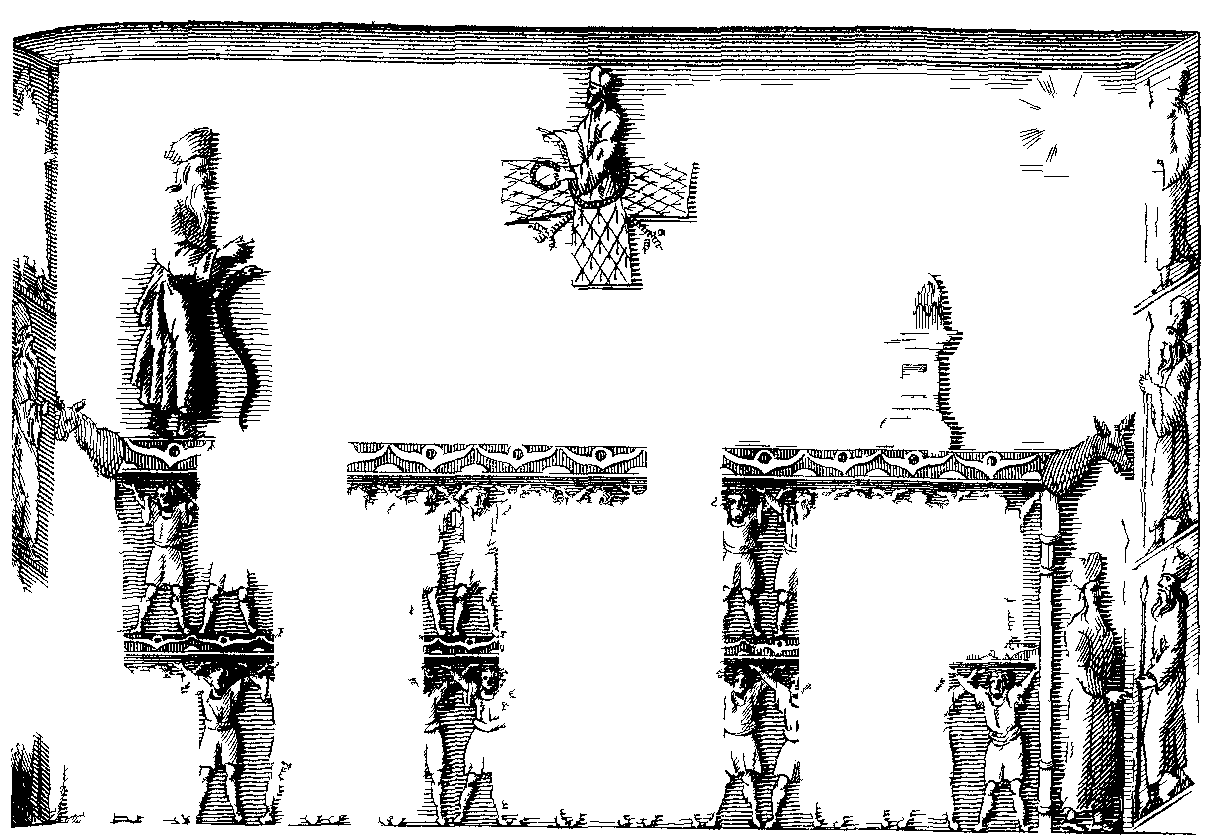

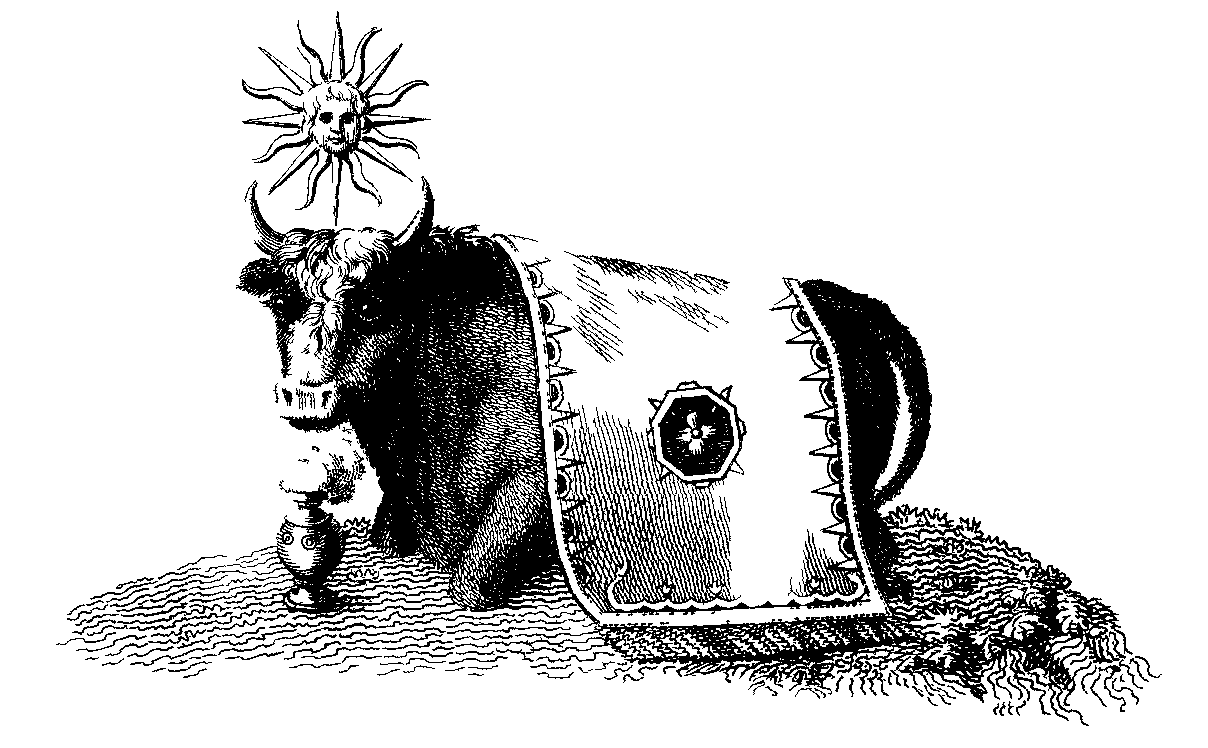

The Grecians therefore were wrong in their etymology; and we may trace the origin of their mistake, when they supposed the meaning of Zoroaster to have been vivens astrum. I have mentioned, that both Zon and [1002]Zoan signified the Sun: and the term Zor had the same meaning. In consequence of this, when the Grecians were told that Zor-Aster was the same as Zoan-Aster, they, by an uniform mode of mistake, expressed the latter ζωον; and interpreted Zoroaster αστερα ζωον. But Zoan signified the Sun. The city Zoan in Egypt was Heliopolis; and the land of Zoan the Heliopolitan nome. Both Zoan-Aster, and Zor-Aster, signified Sol Asterius. The God Menes was worshipped under the symbol of a bull; and oftentimes under the symbol of a bull and a man. Hence we read of Meno-Taur, and of Taur-Men, in Crete, Sicily, and other places. The same person was also styled simply [1003]Taurus, from the emblem under which he was represented. This Taurus was also called Aster, and Asterius, as we learn from [1004]Lycophron, and his Scholiast. Ὁ Αστηριος ὁυτος εστιν ὁ και Μινοταυρος. By Asterius is signified the same person as the Minotaur. This Taur-Aster is exactly analogous to [1005]Zor-Aster above. It was the same emblem as the Mneuis, or sacred bull of Egypt; which was described with a star between his horns. Upon some of the [1006]entablatures at Naki Rustan, supposed to have been the antient Persepolis, we find the Sun to be described under the appearance of a bright [1007]star: and nothing can better explain the history there represented, than the account given of Zoroaster. He was the reputed son of Oromazes, the chief Deity; and his principal instructor was Azonaces, the same person under a different title. He is spoken of as one greatly beloved by heaven: and it is mentioned of him, that he longed very much to see the Deity, which at his importunity was granted to him. This interview, however, was not effected by his own corporeal eyes, but by the mediation of an [1008]angel. Through this medium the vision was performed: and he obtained a view of the Deity surrounded with light. The angel, through whose intervention this favour was imparted, seems to have been one of those styled Zoni, and [1009]Azoni. All the vestments of the priests, and those in which they used to apparel their Deities, had sacred names, taken from terms in their worship. Such were Camise, Candys, Camia, Cidaris, Mitra, Zona, and the like. The last was a sacred fillet, or girdle, which they esteemed an emblem of the orbit described by Zon, the Sun. They either represented their Gods as girded round with a serpent, which was an emblem of the same meaning; or else with this bandage, denominated [1010]Zona. They seem to have been secondary Deities, who were called Zoni and [1011]Azoni. The term signifies Heliadæ: and they were looked upon as æthereal essences, a kind of emanation from the Sun. They were exhibited under different representations; and oftentimes like Cneph of Egypt. The fillet, with which the Azoni were girded, is described as of a fiery nature: and they were supposed to have been wafted through the air. Arnobius speaks of it in this light. [1012]Age, nunc, veniat, quæso, per igneam zonam Magus ab interiore orbe Zoroastres. I imagine, that by Azonaces, Αζωνακης, beforementioned, the reputed teacher of Zoroaster, was meant the chief Deity, the same as Oromanes, and Oromasdes. He seems to have been the supreme of those æthereal spirits described above; and to have been named Azon-Nakis, which signifies the great Lord, [1013]Azon. Naki, Nakis, Nachis, Nachus, Negus, all in different parts of the world betoken a king. The temple at Istachar, near which these representations were found, is at this day called the palace of Naki Rustan, whoever that personage may have been.

Zor-Aster, sive Taurus Solaris Ægyptiacus

[936] He ordered it to be inscribed upon his tomb, ὁτι και Μαγικων γενοιτο διδασκαλος. Porph. de Abstin. l. 4. p. 399.

[937] By Zoroaster was denoted both the Deity, and also his priest. It was a name conferred upon many personages.

[938] Zerdûsht, seu, ut semel cum vocali damna scriptum vidi, Zordush't, idem est, qui Græcis sonat Ζωροαστρης. Hyde Relig. Vet. Persar. c. 24. p. 312.

[939] L. 30. c. 1. p. 523.

[940] Arnobius. l. 1. p. 31.

[941] Clemens. l. 1. p. 399.

[942] Ibid. l. 5. p. 711. Ταδε συνεγραφεν Ζοροαστρης ὁ Αρμενιου το γενος Παμφυλος. κλ. Εν αδῃ γενομενος εδαην παρα Θεων.

[943] Clemens. l. 1. p. 357. Apuleius Florid. c. 15. p. 795, mentions a Zoroaster after the reign of Cambyses.

[944] Justin. l. 1. c. 1.

[945] Syncellus. p. 167.

[946] P. 315. It is also taken notice of by Huetius. Sinam recentiores Persæ apud Indos degentes faciunt (Zoroastrem). D.E. Prop. 4. p. 89.

[947] Sed haud mirum est, si Europæi hoc modo dissentiant de homine peregrino, cum illius populares orientales etiam de ejus prosapiâ dubitent. At de ejus tempore concordant omnes, unum tantum constituentes Zoroastrem, eumque in eodem seculo ponentes. p. 315.

[948] Plures autem fuere Zoroastres ut satis constat. Gronovius in Marcellinum. l. 23. p. 288. Arnobius and Clemens mention more than one. Stanley reckons up six. See Chaldaic Philosophy.

[949] P. 312.

[950] Zoroaster may have been called Zerdusht, and Zertoost: but he was not Zerdusht the son of Gustasp, who is supposed to have lived during the Persian Monarchy. Said Ebn. Batrick styles him Zorodasht, but places him in the time of Nahor, the father of Terah, before the days of Abraham. vol. 1. p. 63.

[951] Diogenes Laert. Proœm. p. 3.

[952] Προ των Τρωικων ετεσι φ' Ζωροαστρης.

[953] Laertius Proœm. p. 3.

[954] Pliny. l. 30. c. 1.

[955] Ζωροαστρις ὁ Μαγος, ὁν πεντακισχιλιοις ετεσιν των Τρωικων γεγονεναι πρεσβυτερον ἱστορουσιν. Isis et Osir. p. 369.

[956] Zoroastrem hunc sex millibus annorum ante Platonis mortem. Pliny. l. 30. c. 1.

[957] P. 16. and p. 47.

[958] Euseb. Chron. p. 32. Syncellus. p. 167.

[959] Pliny. l. 30. c. 1. p. 524.

[960] Ουκ ειναι μαθειν ποτερον Δαρειου πατηρ, ειτε και αλλος κ λ. He owns, that he could not find out, when Zoroaster lived. Ὁπηνικα μεν (ὁ Ζωροαστρης) ηχμασε την αρχην, και τους νομους εθετο, ουκ ενεστι σαφως διαγνωναι. l. 2. p. 62.

[961] Pliny. l. 30. c. 1.

[962] Huetii Demons. Evan. Prop. 4. p. 88. 89.

[963] See Huetius ibid.

[964] Αστρονομιαν πρωτοι Βαβυλωνιοι εφευρον δια Ζωροαστρου, μεθ' ὁν Οστανης·—αφ' ὡν Αιγυπτιοι και Ἑλληνες εδεξαντο. Anon. apud Suidam. Αστρον.

[965] Primus dicitur magicas artes invenisse. Justin. l. 1. c. 1.

[966] Diog. Laertius Proœm. p. 6.

[967] Την Μαγειαν την Ζωροαστρου του Ωρομαζου. Plato in Alcibiade l. 1. p. 122.

Agathias calls him the son of Oromasdes. l. 2. p. 62.

[968] Pliny. l. 7. c. 16. Risit eodem, quo natus est, die. See Lord's account of the modern Persees in India. c. 3. It is by them said, that he laughed as soon as he came into the world.

[969] Hermippus apud Plinium. l. 30. c. 1.

[970] Dio. Chrysostom. Oratio Borysthenica. 38. Fol. 448. Euseb. Præp. l. 1. p. 42. See also Agathias just mentioned.

[971] Θυειν ευκταια και χαριστηρια. Plutarch Is. et Osir. p. 369.

[972] Primus dicitur artes magicas invenisse, et mundi principia, siderumque motus diligentissime spectâsse. Justin. l. 1. c. 1.

[973] Ζαραδης· διττη γαρ επ' αυτῳ επωνυμια. Agath. l. 2. p. 62.

[974] Ζαρητις, Αρτεμις, Περσαι. Hesych.

Zar-Ades signifies the Lord of light: Zar-Atis and Atish, the Lord of fire.

[975] L. 1. c. 5. p. 16. Of the title Zar-Ovanus, I shall treat hereafter.

[976] Plutarch. Is. et Osiris. p. 369.

[977] See Agathias. l. 2. p. 62.

[978] Plutarch says, that Zoroaster lived five thousand years before the Trojan war. Plutarch above.

[979] Ὁυτος (ὁ Θεος) εστιν ὁ πρωτος, αφθαρτος, αϊδιος, αγεννητος, αμερης, ανομοιοτατος, ἡνιοχος παντος καλου, αδωροδοκητος, αγαθων αγαθωτατος, φρονιμων φρονιμωτατος. Εστι δε και πατηρ ευνομιας, και δικαιοσυνης, αυτοδιδακτος, φυσικος, και τελειος, και σοφος, και ἱερου φυσικου μονος ἑυρετης. Euseb. P. E. l. 1. p. 42.

[980] Clemens. l. 5. p. 711.

[981] Εν ᾁδη γενομενος εδαην παρα Θεων. Ibid.

[982] Dion. Chrysostom. Oratio Borysthenica. p. 448.

[983] Hyde. p. 312.

[984] Abulfeda. vol. 3. p. 58. See Hyde. p. 312.

[985] Hesych. Μαγον.

[986] Suidas. Μαγοι.

[987] Oratio Borysthen. p. 449.

Μαγοι, ὁι περι το θειον σοφοι. Porph. de Abst. l. 4. p. 398.

Apuleius styles Magia—Diis immortalibus acceptam, colendi eos ac venerandi pergnaram, piam scilicet et diviniscientem, jam inde a Zoroastre Oromazi, nobili Cælitum antistite. Apol. 1. p. 447. so it should be read. See Apuleii Florida. c. 15. p. 793. l. 3.

Τους δε Μαγους περι τε θεραπειας θεων διατριβειν κλ. Cleitarchus apud Laertium. Proœm. p. 5.

[988] Diodorus Sic. l. 2. p. 94.

[989] Marcellinus. l. 23. p. 288.

[990] Ibidem. It should be Regis prudentissimi; for Hystaspes was no king.

[991] Rerum Franc. l. 1. He adds, Ab hoc etiam ignem adorare consueti, ipsum divinitus igne consumptum, ut Deum colunt.

[992] Αστρον ζωον. Clemens Recognit. l. 4. c. 28. p. 546. Greg. Turonensis supra. Some have interpreted the name αστροθυτης.

[993] Προσαγορευουσι και Συριον. Pr. Evan. l. 1. p. 27. Some would change it to Σειριον: but they are both of the same purport; and indeed the same term differently expressed. Persæ Συρη Deum vocant. Lilius Gyrald. Synt. 1. p. 5.

[994] Joshua. c. 15. v. 58.

[995] 1 Maccab. c. 4. v. 61. called Beth-Zur. 2 Chron. c. 11. v. 7. There was an antient city Sour, in Syria, near Sidon. Judith. c. 2. v. 28. it retains its name at this day.

[996] Βηθσουρ. Antiq. l. 8. c. 10.

The Sun was termed Sehor, by the sons of Ham, rendered Sour, Surius, Σειριος by other nations.

Σειριος, ὁ Ἡλιος. Hesych. Σειριος ονομα αστερος, η ὁ Ἡλιος. Phavorinus.

[997] Βεδσουρ—εστι νυν κωμη Βεθσορων. In Onomastico.

[998] Bethsur est hodie Bethsoron. In locis Hebræis.

[999] Lilius Gyraldus Syntag. 13. p. 402.

[1000] Jovi. O. M. et Deæ Suriæ: Gruter. p. 5. n. 1.

D. M. SYRIÆ sacrum. Patinus. p. 183.

[1001] Apud Brigantas in Northumbriâ. Camden's Britannia. p. 1071.

[1002] See Radicals. p. 42. of Zon.

[1003] Chron. Paschale. p. 43. Servius upon Virg. Æneid. l. 6. v. 14.

[1004] Lycophron. v. 1301.

[1005] Zor and Taur, among the Amonians, had sometimes the same meaning.

[1006] See the engraving of the Mneuis, called by Herodotus the bull of Mycerinus. Herod. l. 2. c. 130. Editio Wesseling. et Gronov.

[1007] See the Plates annexed, which are copied from Kæmpfer's Amœnitates Exoticæ. p. 312. Le Bruyn. Plate 158. Hyde. Relig. Vet. Pers. Tab. 6. See also plate 2. and plate 4. 5. vol. 1. of this work. They were all originally taken from the noble ruins at Istachar, and Naki Rustan in Persia.

[1008] Huetii Prop. 4. p. 92.

Lord, in his account of the Persees, says, that Zertoost (so he expresses the name) was conveyed by an Angel, and saw the Deity in a vision, who appeared like a bright light, or flame. Account of the Persees. c. 3.

[1009] See Stanley's Chaldaic Philos. p. 7. and p. 11. They were by Damascius styled Ζωνοι and Αζωνοι: both terms of the same purport, though distinguished by persons who did not know their purport.

[1010] See Plates annexed.

[1011] Martianus Capella. l. 1. c. 17. Ex cunctis igitur Cœli regionibus advocatis Diis, cæteri, quos Azonos vocant, ipso commonente Cyllenio, convocantur. Psellus styles them Αζωνοι, and Ζωναιοι. See Scholia upon the Chaldaic Oracles.

[1012] Arnobius. l. 1. p. 31.

[1013] The Sun was styled both Zon, and Azon; Zan and Azan: so Dercetis was called Atargatis: Neith of Egypt, Aneith. The same was to be observed in places. Zelis was called Azilis: Saba, Azaba: Stura, Astura: Puglia, Apuglia: Busus, Ebusus: Damasec, Adamasec. Azon was therefore the same as Zon; and Azon Nakis may be interpreted Sol Rex, vel Dominus.