|

|

Atlantis

The Book Of Angels

By D. Bridgman-Metchim

LIBER II

LIBER I | LIBER III

I. PREPARATIONS

II. THE SHADE OF HUITZA

III. THE RISING SUN

IV. THE CAMP OF TOLTIAH

V. THE TACOATLANTA

VI. THE FIRST STEP OF FAME

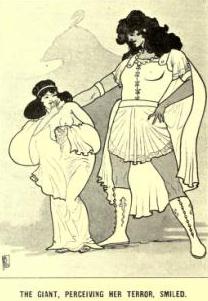

VII. HUITZA AND TERROR

VIII. A VISION OF WARNING

IX. THE MARCH OF TOLTIAH

X. THE NIGHT OF SPIRITS

XI. THE HOUSE DIVIDED

XII. THE WOOING OF ZUL

XIII. THE HILL OF THE TALCOATLA

XIV. THE SHAME OF THE STRONG

XV. THE JUBILEE OF ZUL

XVI. "O TERQUE QUATERQUE BEATI--! "

XVII. THE INFERNAL COUNCIL

XVIII. THE VISION OF THE EARTH

XIX. THE HEART OF THE WORLD

XX. THE THRONE OF ATLANTIS

XXI. THE DEAFNESS OF THE NATION

XXII. SUSI

And God looked upon the earth, and, behold, it was

corrupt;

for all flesh had corrupted his way upon the earth. Genesis VI

12

CHAPTER I. PREPARATIONS.

OE, Earth, for all thy rebellion

and foolishness, for the trouble of to-day to ensure a result

that recoils on thy head in ruins or eludes thy grasp! Builder of

towers, where are all thy mighty works now, and who knows thy

sons' names? Men of unsurpassed greatness were they, of godlike

presence and terrible power, but they are gone and none know of

them or of manner of their passing. Only God lives on forever as

at the beginning, perfect and deathless Life and Love, awful in

unswerving evolution, passing onward through the centuries and

long ages, sublime, remorseless.

OE, Earth, for all thy rebellion

and foolishness, for the trouble of to-day to ensure a result

that recoils on thy head in ruins or eludes thy grasp! Builder of

towers, where are all thy mighty works now, and who knows thy

sons' names? Men of unsurpassed greatness were they, of godlike

presence and terrible power, but they are gone and none know of

them or of manner of their passing. Only God lives on forever as

at the beginning, perfect and deathless Life and Love, awful in

unswerving evolution, passing onward through the centuries and

long ages, sublime, remorseless.

Thee would I contemplate in wondering awe, almighty and mysterious, and feel with thrilling terror thy presence in all atoms, of brightest deeps of immense space or darkest centres of Worlds; feel thy vast Life in the subtle air and flame and the core of adamantine rocks Thine eve watches from leaf and stone and star, Thy voice speaks in all sounds, and I fallen, fallen I tremble for ever in Thy constant and unavoidable presence.

Thee would I contemplate when soft night throws her gemmy veil high over the Earth, and hear in the cool depths, unhindered by details, the music of Thy Life that never sleeps, and weep with wondering anguish that Earth can attract a soul by one bewildering atom.

WEEP WITH WONDERING ANGUISH THAT EARTH CAN ATTRACT A SOUL BY ONE BEWILDERING ATOM.

Yet is sorrow and remorse unceasing, and for ever and ever might we fitly bewail our sins; but thereby we should not profit others, for each soul stands alone in its blindness and will not see. And my Love, for whom I gave up all, could not perceive until the Earth had passed and left the spirit free; and I know not if my state would have been different if she had. O Azta!

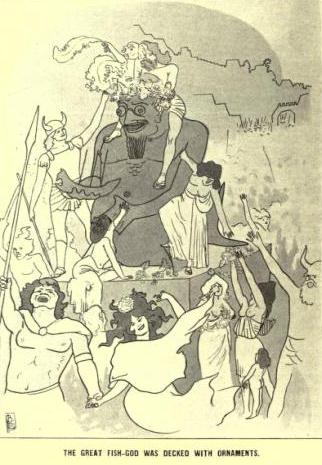

There were long seasons that passed, and many who prepared themselves in them for calculated results; for after one great blow had been struck there would not be left to the vanquished aught but surrender. And thus they of Zul, and especially many princes who wished to supplant Shar-Jatal, yet being fearful of one another, spent many months in great works of war, manufacturing engines to batter in walls, and a great number of kites wherewith to carry up injurious things to drop over the enemy. Enormous quantities of all manner of arms were made, of swords, spears, bows and arrows, bucklers and helmets. And as particularly Talascan was wished to be seized, the warships Tacoatlanta, Mexteo and others were looked to, and more built; for the city was most pregnable from the river front on the Hilen river, and was a most strong centre for warlike operations. The idols were greatly propitiated to grant success, the fish-god by the waterway, which held in its hands the model of the Tacoatlanta, being much entreated of all seamen. Acoa advised long and careful preparations, and greatly hindered many things by omens and feigned messages from the gods; also causing an irksome taxation to be put on the people, so that, in spite of the need, Shar-Jatal became unpopular.

Now Noah had fled with his family afar from Tek-Ra to the mountains beyond Talascan, and hid himself so that none ever chanced on him; to where also I conveyed Azta. And there was with them Nahuasco with his guards and the child Toltiah, which one rapidly increased in stature and beauty and loved the practice of arms, being held in some awe by reasons of his strange monstrosity and the swiftness of his growth, having a voice that was of a mighty volume yet as musical as a woman's, and combining also a giant's strength and rudeness of arrogance with a feminine grace and persuasiveness that caused him to be beloved and feared after an unearthly fashion. To the woman Susi, who was as a mother to him, he bore a great regard, and Azta loved the fair woman for her kindness to him, and wept over the boy and ever gazed rapturously upon him. Which thing was a great sorrow to me, for he was wondrous like to Huitza; yet to my Love I did not show the sorrow in my heart. But oft I looked upon the fair Susi, and envied her lord the possession of such an onel Why was not my Love as this? And yet I too clearly perceived that it was not through her that I suffered, but through my own headstrong wantonness.

To Talascan occasionally went messengers from Noah, to strengthen the report that Huitza should return, and to perceive how the feelings of the people ran. And there was much information known respecting the great preparations of Zul for the subjugation of the land, so that all feared exceedingly; nevertheless the cities had agreed to fight for freedom and to aid one another, and the smallet cities and villages had been deserted, their inhabitants aiding to swell the fighting strength of the larger ones. Yet what would have come had there been separate governments granted to them then I know not, save much dissension, and Zul would have ever boasted herself ruler of all, and become paramount by sin and by all the great ones flocking thither.

Now concerning Talascan, the city lay on the farther bank of the Hilen river from Zul, and behind rose the peaks of a great volcanic range of mountains, trending to the west, then south-west and south. Their lower hills at intervals lay on the river banks, enclosing level tracts of land covered with mighty trees, the territories of Atala and Axatlan.

Through a natural valley in the highlands of Astra, whose northern boundary was thus terminated by it, the Hilen flowed into the sea with a swift current, a great span in width at its mouth, between two tall cliffs called the Gates of Talascan, and inland its tributaries watered a great tract of country. Axatlan lay farther to the west than Atala, and held the burning mountain that so affrighted the people, where the great serpent Nake was believed to keep watch over mines of gems and quarries of red stone which were of the Lord Nezca.

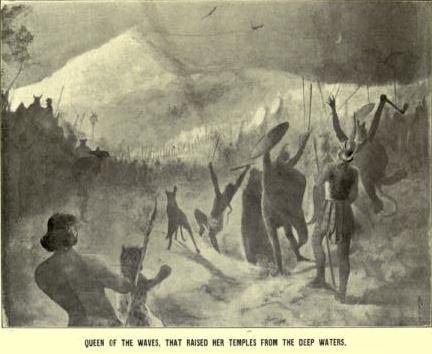

WHERE THE GREAT SERPENT KEPT WATCH OVER MINES OF GEMS.

Mr. A. W. Buckland in his "Anthropological Studies" gives most curious and interesting information concerning serpents and their worship.

There must, as in other curious things, be something to give rise to the legends concerning the mystic creature, when we notice the strange persistency with which he and the gods, of whom he is the emblem, are associated with agriculture, wealth, power, honor, gold and gems; and as Mr. Buckland says, the deeper we delve into this mysterious past, the more numerous and important do these serpent legends become, bringing to our view whole tribes who were supposed to be half serpents kings and heroes of semi-serpentine descent, and gods either serpentine in form, or bearing the serpent as a sacred symbol; and it is a strange fact that all these gods and men thus singularly connected with the serpent have always some inexplicable relation to precious stones, the precious metals, the dawn of science and of agriculture.

But this state of serpent-religion would appear to have developed later, among mythic histories of the Deluge and the legendary demi-gods, and a point might well be argued as to the connection of serpent with seraph.

Under the shadows of the mountains, surrounded by forests, streams and meadows and with the great river surrounding it on three sides, Talascan was a beautiful and healthy city, raising its walls and towers and columns from a sea of verdure.

Chanoc was the Governor of Atala, who also loved Huitza greatly and believed that he would appear as the rumours said. For the prince had gone to Talascan secretly and declared that he would free them from the bondage of Rhadaman when that he had captured Zul for himself. He commanded them to spread no rumour of his presence there and to disclaim all knowledge of it; and many of their warriors went with his legions. He also promised to give the Talascans freedom on condition that they would ahvays help him if required; for he perceived the natural strength of the place and how it could be stoutly defended, having, as it were, the river for a wall; the which could only be forded by an army many miles up above the city, being too mountainous below for such. The Talascans, who were hardy and brave, would aid him greatly; and thus, exacting solemn oath from Chanoc and the great chiefs of the city that they would ever be faithful to him, he had gone forth; and the next news they heard of him, which thing many also perceived with their own eyes, was that he had returned to Zul and had slain the Lord Rhadaman in single combat.

The people were in high spirits, but the following news of Huitza's death damped them. But Chanoc was ambitious and stirred up the people to resistance, sending a secret invitation for all who had loved the prince and wished for freedom to come to them.

Still they feared the wrath of Tekthah, yet were they not also a great community? There were many mighty men there, for Rhadaman, after the dreadful raid spoken of by Noah to avenge resistance to his tax-collectors, had made great concessions to induce many to go there. For from Atala came the beautiful scented woods, colouring woods and earths, great quantities of gold and very handsome women, and much fish from the river. Yet many feared another raid, remembering the day when the legions of Rhadaman made a furious onslaught; when the huge bulk of the Tacoatlanta, crashing through their little fleets up to the landing-stage, disgorged its freight of fierce warriors, and their streets ran red with blood. That day the war-ship lay in a red harbour, and only night put a stop to the fratricidal carnage.

Then came a rumour that Huitza would return again in the flesh, and after, that Tekthah was dead and Shar-Jatal reigned in Zul. So that every one was glad, by reason of the usurper's, popularity. Yet messengers arrived from the great High Priest Acoa, commanding them to resist such an accession, saying that Shar-Jatal was accursed of Zul in that he had murdered the Tzan, and exhorting all to unite against him and wait for Huitza to appear. Whereupon was much bewilderment, and the messengers remained, as also did others; and then arrived the news that Izta had been created Lord of Atala. Now Izta's reputation was an evil one, and, Tekthah dead, (whom all feared yet reverenced,) it was determined that the greater cities should remain free, offering to shelter and protect the inhabitants of the smaller ones.

How greatly was I bewildered with it all! For Nezca sent by stealth to Axatlan, bidding his people defend the river and he would make to them great concessions, and Azco stirred up the new Tzan's own land of Trocoatla to resistance. All the country rose in wrath against the Representative, who was as one of themselves and had dared to do this thing, yet feared the reports of the preparations being made against them.

All was forgotten save war, and evil enjoyment while yet there was time for such; but long times passed and nothing happened, only went on manufactures of weapons and of all sorts of arms, and all manner of foul preparations were placed in bowls on the walls to hurl upon the besiegers when they came. Some cities surrounded themselves with moats filled with water, one beyond another, others with barricades of combustibles that could be fired by flaming arrows from the walls, while nomad tribes were loaded with gifts to harry the enemy when he appeared and give timely warning of such appearance.

Chanoc barricaded the river front and constructed in the Hilen below the city a vast boom to prevent the warships coming up, and the rows of idols on the walls were entreated to prevent mishap, for all cities had these hideous creations along the fortifications.

All these things I saw, and wondered which should conquer in the end; and in these years Azta's love for Toltiah grew and increased with his growth, and I knew that it was spoken that he should be Lord of Atlantis. Me she suffered as much as I would, yet I knew in her heart she loved me not, and ofttimes I wished that I had never seen her; while her nature, exasperated by conditions that caused me to despair in silence, grew violent and outrageous. But her beauty chained me with the chains of Hell and I could not depart from her now; knowing that I never should had she loved me, and only would do so because her heart was turned from me. I had sinned deeply and could but wait events; which indeed were interesting while they lasted, for none know all the Future save God alone.

And Toltiah grew more fond than was seemly of strong drink and was also enamoured of the smoking-herb. By reason of my virtue he had great knowledge of hidden things, pondering deeply over all the instruction of Noah. And many things such as should not be known he imagined, and was much exercised in his mind concerning them; searching into such that concerned life and death, yet not with reverence, but with curiosity. He grew tall and strong and greatly excelled in the use of arms, being instructed by Nahuasco therein; while the sons of Noah taught him many things in hunting and arts, so that he became greatly accomplished, and far more than they, becoming also taller than Ham, which was the tallest of them, at the appointed time that was spoken.

CHAPTER II. THE SHADE OF HUITZA.

YET being much smaller, Talascan was built after the fashion of Zul: and the great ports, shut above the moat, bid defiance to any attack from land, but the river front was open. The architecture, though not equalling the massiveness or grandeur of the capital, was nevertheless sufficiently remarkable. There was a vast temple to the Lord of Light and many others also; the Governor's palace where also the Lord of the Territory resided whenever he visited it; the Market-place by the river, surrounded by bazaars and having a collection of deistic symbols and representations; and innumerable houses built of lava stone.

Down by the waterway lay a fleet of boats and rafts, numerous others being tied to the banks or lying on them. Single tree-trunks, hollowed by fire, formed the greater part of them, but there were many rush-framed and skin-covered boats and rafts floated by whole skins of animals inflated. There were no large vessels there, and the only one they had ever seen of large size was the Tacoatlanta, which at times came up the river through the Gates of Talascan with a great wash of water around her, either to call there or go beyond, and occasionally smaller war-vessels from Zul would come up. These were such as were designed to sail round the encircling moat, and were shallow boats.

The population reminded the visitor of Zul during the period of the annual tournaments, for here there were always many hunters, miners, fishers and collectors of gums and feathers; and, although every man was a warrior and liable to be called upon to attack or resist an enemy, there was nevertheless a troop clothed and armed uniformly and kept in idleness for any emergency.

Here, also, in addition to the vices of a barbarous civilization, was exhibited the natural life of the country before cities were built, the life of the single-handed warrior and hunter searching for his daily bread with no farther care or ambition; yet who had also fallen into idolatry and worshipped whatsoever his fancy gave him.

As at Zul, there was kept, in the temple of the Sun, Tekthah's standard and symbol, a four-armed cross; and all over the city, on pedestals, in temples or niches, wriggled in wooden or stone semblance the worshipped offspring of degraded ideas: there a bird-headed Thoth stood, and there foul Lamia writhed their serpent-coils. Dagons and Bellerophons, Centaurs, antlered men and winged monsters and the hermaphrodite gods of Atlantis were represented under various names; but by far the greater number were the most grossly prostituted representations of female forms, the producers and nurses of life. Before them burned sweetly-scented natural woods in earthern braziers, and strong animal odours were offered to their gross nostrils. The human mind went out of its way to exaggerate and degrade, and crazed priests, mad with excesses, fanned the popular enthusiasm and preached the righteousness of it all.

The nobles followed the lead of Zul, and I saw how terrible a thing is a bad example set in high places. For ambition Tekthah had poured violence and excitement into the people's hearts, and now he had himself fallen beneath the whirlwind. It seemed that nought could check the chaos of sin, and no terror of nature turned the nation's heart to God; for when to the west the thin vapour that ever wreathed the head of Axatlan lifted at times to the rush of a column of fire that burst forth with a roar and outpourings of rivers of gold, the people would but offer up more victims and drench their idols with wine, imploring them to hear and save them.

Large of limb and but half-civilized were most of the Talascans, cursing the Lord Rhadaman and crying to the Sun to burn him; yet they went not elsewhere, because if the master were not Rhadaman it was Izta or some other; and also the human breast was strongly inclined not to leave the place of its birth, thereby preventing some places becoming overpopulous and others empty. And this, notwithstanding that they might be desert, or subject to earthquakes, or greatly overrun by noxious beasts or insects.

The Talascans, as all of Atala, I have said, were hardy mountaineers. Great hunters were they, armed with axes and spears of flint and bone and metal, with which they killed the large bears that lived in the caves. In their forests were the elk and the mammoth, and others huge of bulk and terrific in appearance and power, rending the trees and devouring the crops of wheat and maize; and there were great saurians in the rivers, whose teeth were used for spearheads, while a very large species of land-crab at times invaded them and covered the earth with its multitudes. Eagles harried their flocks, and serpents of vast length terrified them; a certain fowl, with a body as great as an ox and formidable mandibles, furnished dangerous sport for the hunters, but was excellent to the taste as meat; and the fierce aurochs ran in dark herds on the borders of Axatlan and to the south, many lives being lost in the pursuit of such. There were lynxes and panthers that carried off the domestic fowls, and also vexatious wild cats and dogs and smaller vermin.

Before such a statement as this we can but bow the head in silence. Neither the oldest histories nor palaeontological researches have discovered so great a bird, although there were of old larger animal forms than now. The Dodo, which, classified among the pigeons, was a giant of its species; the gigantic ostrich-like Dinornis of New Zealand the Pelagornis, a winged monster of the albatross tribe; the Moa, the Gastornis Parisiensis whose remains have been recently found in the Eocene conglomerates of Meudan all these as birds far surpass any we can muster now, but would not furnish a parallel to the bird of Atlantis, although they might prove the descending scale of size.

Yet the land was rich, and the people always had enough wherewith to pay the taxes; while by their prowess commanding respect they were always well cared for and favourably noticed at the Capital when they went up to trade or attend the Circus festivals.

Out beyond the river-mouth and Astra lay the great pearl-oyster beds, whose white gems were so much in request among the belles and fair women of Zul, commanding great prices wherever exhibited and being a valuable revenue to the land. And this was a great covetousness to Chanoc, for if the country were swept by fire and sword the new Tzan could not destroy the pearl-fisheries, which could be a revenue to them against the rest of the land.

Great meetings were called for discussion of defence against the threatened invasion. Often messengers arrived from Acoa, declaring that the gods would aid Huitza, who might shortly be expected; and at length came one who asserted that he had seen the prince himself. This one was sent by Noah, for the time appointed had arrived that Toltiah, being now grown, should appear.

And in this manner the youth came to Talascan: Noah and his family, with Azta and Nahuasco and the guards, arrived before the walls and were admitted, causing no small comment, for all knew Azta and many recognised the Tzantan Nahuasco and most of the family of the aforetime governor of Tek-Ra. The patriarch declared] that, Huitza dead, he had been drawn into the wilderness to seek him, and would now reveal the reappearing leader to the land. Crowds gathered around the group, and my Love, with her wonderful presence and surrounded by the glamour of a myriad tales and romances, real and imaginary, greatly aided the enthusiasm attendant. Noah vowed that he would next day produce Huitza in the flesh before all, sent to them by the Lord Jehovah to avenge his forgotten and insulted name, being also Father of Zul before whom other gods were preferred. He reminded them that Huitza was greatly beloved of Zul, and at his words Azta's eyes flashed so that my soul fainted with sorrow. Running messengers were despatched to every city and all the tribes to tell them, Huitza comes, rejuvenated, pregnant with victory, to bring freedom to the land and avenge the nation on the tyrants that ground it down.

Thus he would come, and in this favoured city would he appear, preferring it before any of Tek-Ra, and would make it a mighty name in Atlantis.

The populace was in a state of wild enthusiasm; Chanoc gave a palace for Azta and Noah and their people to dwell in, and that night the city flared with bonfires. Everyone was drunk with wine, and the large square of the Market-place was full of revellers in a state bordering on insanity. They shouted and shrieked, pouring wasteful libations over the bestial images until they shimmered under the lurid glow of the fires, with their trickling, odorous streams. Skin-clad hunters shook their spears in the air, leaping like madmen with formidable cries, some imitating the roaring of lions or the trumpet-call of the deer; and women with dishevelled hair and bared bosoms ran shrieking among them, their eyes flashing in the lights as they rolled them with wanton glances. The banging of drums and shrieks of whistles added greatly to the din, but the chiefs and nobles discussed the advent of the great Huitza and wondered what should come of it.

Myself, I dared not interfere. These mortals knew the temper and inclinations of one another better than I, and surely one born as Toltiah should be able to cope with matters of Earth.

Thus the next day Noah came down to the Market-place attended by Chanoc and his guards, with Nahuasco's troop, his servants and his family, among whom was Azta. Mounted upon a block, the patriarch stood elevated above the thousands who came running from all around, leaving the walls and barricades at the call of the Governor's trumpets, waiting to hear what he might say to them and forgetting his corrective reputation in the knowledge that he was the trusted vizier of their great chieftain.

Among the crowds mingled warriors of the city guards, their bright helmets flashing above the more sombre headdresses, and shadowed by the beautiful plumes of the ostrich, which were eagerly obtained, or that of the wild swan. None in all the land wore the plumage of the peacock, fearing it with a great superstition, and holding it as the emblem of the setting sun, of which they supposed its spread tail to be a symbol.

Azta, in a slung carriage, commanded nearly as much enthusiasm as the expectation of Huitza, for there were weird legends muchly connecting the twain, and all believed her to be potential in the matter. Tall Shem stood impassive and watchful, Ham and Japheth leaned on their spears, the former rolling his eyes with vast amusement over the crowd of whom he stood one of the tallest. The women and children, among whom stood the fair Susi, were timid and fearful of the multitudes, yet confident in their leader and their God. Only I had no place there, and should scarce indeed have been there at all.

Beyond the rustling of the crowd and the occasional clang of armour there was no sound. Noah began to speak, rousing the people's anger against the usurper, Shar-Jatal, and all the evil lords of Zul. But as yet he would not denounce the evil doings of the land, preferring to wait until the monster of Sin with bruised head should lay at his mercy; in which hope all my soul was also, and I greatly dwelt on its fulfilment.

Now Toltiah lay in the midst of his people, hidden and as yet unsuspected; but after a prayer of exhortation from Noah this one stepped forth and mounted on to the block which the patriarch surrendered in his favour.

The crowd perceived a godlike beardless youth of vast stature and splendid presence, with the ruddy hair and commanding eye of the great Chief. There, younger, taller and still more majestic, he stood, a very miracle before their astonished eyes, a dreadful beauty enstamped upon his features that were like unto a very beautiful woman's. A golden plate covered his chest, broad as an archangel's, and upon his head he placed now the winged helmet.

The silence was broken up, and the air was rent by a vast roar, deafening and prolonged. Four tall warriors, mounting him on their shields, raised him high above the heads of the people, shout on shout rolling to the sky, and Azta's child, in the character of Azta's Love, seemed exalted to the altitude of a god.

Those nearest to him noted that his eyes were yellow and of great penetration, and his hair as dark molten gold. Never had such perfection of form been seen before, such splendid limbs and carriage, and I felt a great pride in my own sad heart as I looked on him and wondered how so strange a being would act. With enthusiastic shouts the people raised their swords and spears, and the crowd swayed under a veil of tossing yellow mantles. Young girls and children were lifted towards him, and in the delirium of their joy even the abominable idols were pulled down and abased before him, all manners of excesses being committed in the frenzy.

And this was also my child, this strange, beautiful being 1 What power lay within the grasp of this splendid Amazon-like man! For one moment, as I thought of Zul and the land of a thpusand cities, I felt a great joy at the thought that it would be his own and he would wield the sceptre of Atlantis from that great red palace, and influence the peoples for good and for Jehovah. And then, perchance, might I claim my Love for mine own and purge my folly in righteousness.

Yet I liked not the look upon Toltiah's countenance, which was one of great arrogance, bespeaking an Earthly spirit. He kissed his thumbs towards the shouting people, seeking the warriors particularly with his eyes and casting a long stare upon Susi, who had refused his secret advances. On Azta, his mother, he smiled triumphantly, and with still more triumph she returned his glance. I perceived the great emotions with which she gazed upon him the love of a mother and, O God! of a lover! the confidence of nigh satisfied ambition that filled her eyes with tears of joy as she watched and heard the roars of enthusiasm that hailed the youth's appearance. His foster-brothers were loudest in their demonstrations, waving spears and shields high with exultant glee, and all were happy save myself. For in that long, deep breath of freedom and the lustful stare around I saw written, as with a flaming finger upon the clouds, my completed doom; and gazing with a horror of longing passion upon Azta, saw that her whole absorbed attention rested upon that shield-borne Majesty that should drag Earth to its doom the consummation of her foolishness and mine.

Mine! I could have melted with agony; and then my attention was fixed again. Suddenly shouts of a different import spread rapidly through the crowd. Above the river barricades appeared three moving poles, the foremost topped with the Cross of Atlantis, and no explanation was needed to tell the crowd what they signified.

Agape and silent they stood for an instant, the moving poles coming up rapidly amid a crashing, creaking and splashing medly of sounds from the flotilla of shipping, and instantly an iron grappler flew to the top of the barricades and held there.

There were many, among whom was Toltiah, who knew not what was portending, but a great shout of dismay enlightened most of them:

"The Tacoatlanta!"

CHAPTER III. THE RISING SUN.

HIGH above the cries of the people rang the voice of Chanoc, claiming attention and distilling confidence. The women ran to hide themselves in the houses, terrified and shrieking, while Nahuasco and the city legionaries ran to repel what might threaten.

There was no time to be lost. Messengers were despatched to the garrisons round the walls to bid them be ready to resist any attack by land, while bands of warriors sped to aid them, and spies were sent to the highest roofs to give warnings and issue directions.

With the guards, towering above all, ran Toltiah, with sword and buckler, eager for the fray and recollecting now all that he had heard of the war-ship and her manner of attack. But most were sorely puzzled as to how the vessel had passed the boom and why no warning of her approach had heen sounded. The city was in an uproar, drums heating and whistles shrieking above the long-drawn war-whoops.

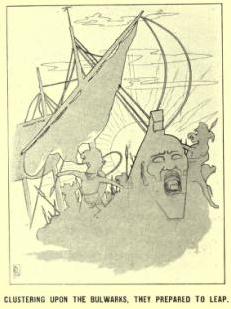

Azta bade her bearers remain where they stood, her heart too full for expression with unknown fears, as, astonished to find the massive barricades opposed to them, the men on the Tacoatlanta nevertheless ran her close up to the landing, with a proud and ferocious confidence in the irresistibility of their wild onrush and the moral. effect of their unshaken valour upon those before them. Clustering upon the bulwarks, they prepared to leap upon the defences when the great vessel could be hauled near enough by the ropes attached to the grapplers, aided by the slaves at the oars.

The defenders were scarce in time

to repel them as in scores they crowned the barricades. Toltiah

waved his mighty blade in flashing circles and smote at the

foremost, shouting " Huitza and Zul!" The warriors took up the

cry; as the sound of a storm it spread from mouth to mouth, and

the Imperial troops perceiving the ruddy mane of the leader and

his resemblance to the dead chief, remembered the prophecy,

wavered in dismayed confusion, and were hurled backwards, many

falling into the water and drowning in their harness.

The defenders were scarce in time

to repel them as in scores they crowned the barricades. Toltiah

waved his mighty blade in flashing circles and smote at the

foremost, shouting " Huitza and Zul!" The warriors took up the

cry; as the sound of a storm it spread from mouth to mouth, and

the Imperial troops perceiving the ruddy mane of the leader and

his resemblance to the dead chief, remembered the prophecy,

wavered in dismayed confusion, and were hurled backwards, many

falling into the water and drowning in their harness.

It was a victory, for the cry spread through the attacking forces, and some of the grapplers were hauled back to them as the warriors hesitated. The heads of the Talascans were raised above the barricade with triumphant shouts, and the archers on the warship let their weapons fall as Ham and Nahuasco raised Toltiah on their shields in full view of all.

But now shouts arose from the roofs and a distant uproar told of war along the land battlements. Leaving his victorious comrades, Toltiah sped thither, accompanied by Shem and Nahuasco, which one would not leave him. The streets were empty, for all were round the walls, but as Toltiah sped Azta cried out to him victoriously, watching the splendid being eagerly until he was gone.

By the walls men fought hand to hand with the glittering warriors of the Imperial Guards, who had landed from the warship to the number of five hundred and were furiously assailing them. Now, above the clangour of armour and the clash of swords, the shouts, shrieks and groans of the combatants and the cries of the captains, rang out a formidable war-cry: "Huitza! Huitza and Zull"

The Talascans with shouts of victory rushed forward, driving the foe from the breaches. Men slipped in blood, and spears were buried in human flesh: limbs dropped, shorn clean off by the heavy swords, and the godlike form of Toltiah, pressing through the swaying crowds, forced its way to the front.

There he fought, the tall wings gleaming above the press, the ruddy hair that there had been no time to wrap round the head flying in yellow masses; the returned Chief, the Prince on whom the hopes of Atlantis were centreed.

The unconquered warriors of Zul stared in wild dismay and hesitated. The Tzantan Nezca cried out that they surrendered to Huitza, while the erstwhile foemen shouted his name exultingly, raising spear and sword in salute.

Flushed with his first success, the youth could afford to be gracious, neither had long wars steeled his heart. Stepping forward, he took Nezca's hand and placed it on his heart, himself performing the same action on the other's person, looking with great regard on the chief, for he was a very goodly man. "We are brothers," he said, and all the warriors shouted with joy, climbing the walls and kneeling in obeisance to the prince.

But I caused a voice to speak to Toltiah; " Go, seize the warship, for there are others that come;" and speeding swiftly to the barricades by the river, he cried, " Seize the Tacoatlanta! "

He was too late. With a confusion of cries, with trailing rigging and mingled oars the great warship was drifting sideways down the centre of the stream; and as the victors crowded down to take her with the little boats that were left unharmed, the painted sail on the fore-mast was raised, the huge steering oars were brought into play and, the other two sails being set to the wind, the monster moved rapidly away, while the pursuers hastened back on perceiving an armada approaching. For, clearing the wreck of the enormous boom, three more warships, towing rafts full of men, were approaching, but stopped on perceiving the flight of the Tacoatlanta and the crowding foemen.

The victors were disappointed in this failure to take the warship. Messengers were instantly despatched to warn the Axatlans who held the fords, eight leagues above the city; for beyond that to the West the mighty stream flowed through defiles and deserts, prohibiting the passages of troops and stores, and even far-wandering hunters knew of no other place for such purpose within any practical distance.

Yet the warships could float over the fords, and therein lay much danger; and a great council was held.

From Nezca was learned that yet another army, under the Tzantan Izta, was on the march against them, with great stores and many engines of war and a multitude of warriors. This army had laid waste the land as it marched, sacking towns and villages and pitilessly murdering all the inhabitants, and going afar from its course to destroy the cities of Tek-Ra and all the territory of Huitza. Upon Chuza was made a night attack, and ere the morning sun had risen the houses and streets ran red with the blood of midnight revellers surprised at their debaucheries and slain, only such escaping as managed to climb up into the great pallo, whose reduction would take more time than was agreeable to accomplish, it being amply stocked with food; for it was used to a great extent as a granary, and there was a well of water within. But the town was left in ruins and the walls razed to the ground A messenger brought back the news to Zul, and, the army on its march for Talascaa, four warships had started under the governance of Budil, a son of Shar-Jatal; and it was hoped that, Talascan crushed, the land would be at the Usurper's mercy.

Then arose the daring ambition of Toltiah, who declared that he would do no less than march upon Zul! This boldness pleased the chiefs, and that night was the youth proclaimed publicly Tzan of Atlantis, king of the Earth, and presented amid impressive ceremonies with the National Standard, taken from its temple for the purpose of being used as the battle-standard until peace should come again.

Crowds assisted, and the city was jubilant. The new Huitza appeared more than victorious, a promise of unlimited joy and freedom! He refused to have an Imperial helmet made, declaring that he would wear Tekthah's and none other.

Azta was triumphant, with an immense pride in her heart, being considered the next most important person to Toltiah. Also she was treated by him (who also stood somewhat in awe of her, being indeed a stranger) and the rest of the populace as Empress, occupying the half of a double throne with him in the palace of Chanoc. Her presence, rendered more majestic and imposing by her sublime pride, impressed all very greatly, and her mystic eyes touched their superstitions deeply. She was supposed, nay, reputed, to be of celestial mould and power, and to her was ascribed the reappearance of Huitza, while her furious impatience of delayed respect made her feared by all.

Mere repute was turned into certainty by her coldness and continence, which commanded respect while inflaming desires, and with the wish of possessing her the thoughts of all who deemed themselves of sufficiently high degree dwelt with a daring joy on possibilities; in the which I perceived much future trouble, yet none could ever encounter the glance of those yellow eyes without feeling a sensation of chill and fear.

Toltiah would fain have rested a while to form a court and establish a household. Arrogant with victory and believing himself to be, as the people declared, a god, he wished to enjoy those growing passions that possibilities bred and nurtured; but the savage impatience of Azta and the exhortations of the governor and the Tzantans advised him to be energetic until the Throne of Atlantis was actually beneath his feet.

Yet now fresh preparations must be made, for they were not ready as regards the offensive, being but as yet desirous of protecting themselves from the power of Zul. To every city was sent the news that Huitza had returned, and it flew abroad on the swift wings of rumour, strengthening the weak and rejoicing the strong; and warriors began to gather across the river by the fords, and journey to Talascan. But the warships and armaments in the river were a vast menace, and perchance had Toltiah more experience he would not have thought of aught yet but protection. But all believed in him, and while residing with his chiefs in the palace he formed a camp also without the walls, bidding all the cities of the province mass their warriors around Talascan; and his genius rising with his power, he showed them how to make a fortress of the city and directed how to form another boom across the river.

Preparations for an immense armament commenced, and the peoples of the city and the tribes without were formed into various legions. Runners were sent to bring in the wandering tribes and even to treat with the western savages and some of the weird peoples who lived in the mountains and deserts of Axatlan. Noah preached a holy war, greatly enthusing all by his frenzy and his zeal, and Azta's gracious words to the Tzantans rendered them eager to commence already a rush on the capital, regardless of the warships and the approaching army of Izta. Yet Nahuasco, and Noah, and such as had followed Tekthah in the old wars, advised caution concerning such a move; for here they would face men of their own race behind impregnable walls, which would have to be surrounded by an encircling trench that would forbid any desperate sallies and bring a long starvation. Nor would this dire famine cause themselves less suffering, seeing how great an army was being raised, which could scarce be fed upon one spot.

But Toltiah would brook no caution; weapons of war were manufactured in great quantities, and because of the clouds of slingers that hung on the flanks of the warships and rafts these had to keep far down the river and on the other side, waiting for Izta to arrive. Bows and arrows were made as fast as eager workers could turn them out; and now Japheth remembered the great engine constructed by his sons outside Chuza, the catapult, heaving a vast bolt upon the enemy. Therefore he set to work to construct one; gangs of men worked at the engine, exulting in all they learned of its possibilities, and the city rejoiced greatly because of the powerful men who had arrived to aid.

The first catapult was set to command the river below the city, in which direction lay the armada, and afterwards more were constructed, and the new legions trained in archery, for all knew the use of spear, sword and sling.

CHAPTER IV. THE CAMP OF TOLTIAH.

EACH day brought reinforcements from all parts by tribes and thousands, encamping under the orders of their own Patriarchs, but all owning the supreme authority of Toltiah.

From the plains came the wild herdsmen of Assa, Het, Emok, and Alorus, powerful chiefs with many followers, the tribes of the Owl standard, and all the spearmen of Enoch; the tribes of the Vulture, the Unicorn, and the Crow.

From the raided province of Tek-Ra came fugitives: from Chuza, Bab-Ista, Bab-An and other cities; from Sular, Karbandu v Azod, Bitaranu, Surapa, Sham; and other great chiefs of the plains with their 'stout followers and countless herds of sheep, goats, and oxen.

And I saw where the young chief Lotis, of Katalaria in Trocoatla, gathered his tall borderers in battle array, his mother being that Yeteve, sister of Azco the governor, who had great distinctions given to her for compliance to the wishes of Shar-Jatal in past days. And notwithstanding that she was a hard woman, she loved her son with a mighty love and was in great distress that he should so depart from her, entreating the gods concerning it upon her knees with floods of tears. Fain would she ever keep her boy by her side, gazing upon him with all the best love of a mother. But San, his beloved, although sorrowing equally with her, would prefer that her lord should go where glory might be reaped. She vowed that she would not survive him, yet loved not to keep her warrior back in shameful security; and although in his absence she wept with the sad mother, in his presence she was brave and exalted, speaking of nought but of glory to be reaped.

And here were two loves, and of the two which was the better?

And in the issue Lotis went forth with all the many thousands that ran to join Toltiah.

How great an enthusiasm was there! The hope of sacking Zul aroused their savage hopes to a terrific pitch, and the name of Huitza was a power, in itself, promising a future beyond all dreams of spoliation and rapine. The total effect of the crowds was as of that great congregation which gathered round the capital at the time of the Circus games; for, stretching in a dense selvedge around the walls of Talascan, some encamped under tents of skin or cloth, others dug holes in the earth, with screens, stretched on poles, surrounding them; while hunters, accustomed to all the hardships of their existence, lay on the ground, encamped round fires. Some of these last, clothed in the whole skins of animals, presented an extraordinary appearance, many wearing over their matted hair, which was usually gathered at the back into a plaited thong, the heads of. wolves, bears, aurochs, and stags with the spreading antlers. Some wore horse skins from which the long, thick tails swung, and one or two carried the horn and cranium of the dreaded unicorn.

The name Unicorn, as its etymology denotes, is given to any animal with one horn, but generally, I believe, refers to the single-horned rhinoceros. In this case it as probably indicates the antelope mentioned in chapter IX.

But among these semi-savages were races who cultivated the arts of cities, and tribes whose wealth permitted the purchase of elaborate war-harness; and among such the plumes of the eagle and ostrich towered above metal helmets, adding to the splendid stature of the wearers clad in gleaming vantbraces and cothurns, cuirass and backplate, their arms of metal and obsidian looking formidable among the clumsy stone axes and mighty tusk-studded clubs of their humbler comrades.

The southern warriors brought with them beautiful women, who fastened lantern-beetles among their ebon tresses, where the lights glowed until the creatures died; and these women were the occasion of many broils and quarrels because of their beauty and wantonness, dallying with any who would.

It was a gay scene of warlike splendour in that great city and the country surrounding the walls. Mingled with rough aprons of hides there were mantles of leopard-skins and the beautiful furs of the beaver, bear, lynx, lion and rabbit; there were breastplates of rough silver from Trocoatla, the whole shells of large turtles bartered from the Astran fishermen, and tortoises from the forests of Axatlan; cuirasses of stout leather, covered with the formidable shield and attached horns of a species of wild ox, or with the spiked scales of the Hilen saurians.

Over far-spreading shoulders hung huge, massy bucklers, leather-covered and studded with metal bosses, some being entirely of metal and very glittering, yet showing dents and hollows received by weapons of war. Some of the Tzantans wore mantles of feather-work, and among the birds that thus gave their coloured beauties for a warrior's ornamentation were conspicuous the white swan, the scarlet flamingo, various macaws and the gem-like humming-bird. The skin-clad hunters gazed with envy on these gorgeous trappings, yet their own sterner robes of lion-skin cost more than feather mantles in manly prowess. There were other garments, of woven cotton and silk,, dyed in various colours, and bartered for eagerly in Zul at the Circus periods; but most of the military cloaks were entirely scarlet, being plain but of striking effect among the other ornaments and trapping.

Abandoned women thronged to the camp, idols were set up to be worshipped and propitiated, and some of the nomad tribes who owned no god at all, were initiated into this or that belief. Those from the southern plains were awe-struck by the mountains, and worshipped the hill Axatlan, visible on the very far horizon; and there were those who had never seen a city and were terrified by the walls and the mighty uncouth colossi that supported the buildings.

Some tribes of savages came in, but these were panicky and fearful of their white companions, and were especially awed by the great city. There were many thousands in the great, roaring camp, more and more arriving as the rumour of the gathering and its object spread, and still the army of Izta came not, and still the armada in the river waited. There were some terrible peoples from the western wildernesses, some huge, some small, all deformed and monstrous, who hung on the outskirts of the vast gathering, feeding on earth-roots and the offal of the camp; and from the north came a great number of Amazons, whose advent seemed likely to cause a strife in the camp, as their reputation, exaggerated and half-mythical, aroused the keenest interest among the licentious crowds, a There were many dangerous episodes and not a little bloodshed before this extraordinary and warlike race was understood to be capable of defending its creed, and some of the best warriors of Toltiah had to own to the strength and courage of these tall, ferocious women, and their skill in the use of weapons. Lithe and agile as panthers, with rounded but sturdy limbs, and thick hair tied in knots under their helmets of animals' craniums, they wore their skin garments girded up under a belt, while their small breasts did not prevent the most perfect use of their arms in wielding spear or axe, most of them wearing over them a tough ceinture of hide fastened round the shoulders. Leathern cothurns covered their legs, and sandals protected their feet; their shields were oblong, made of wolf-skins, with the tails flapping from them, and the heads fastened to the centre. They gazed with great curiosity upon the women of the cities, sneering at their use of powder to decorate their faces, and staring amazed at their jewelled teeth and elaborate head-dresses, and their inhaling of smoke through pipes.

Azta was greatly interested in these warrior-women, whose Queen was a majestic figure, taller than herself; and between the two sprang up a firm friendship. To the Amazon the splendid symmetry and mystic beauty of the Tizin was a wonder and a delight, while no less was the latter's admiration compelled by the high bearing and the bold, free carriage of this woman who dared to compete with men in war. This was the life that won her admiration, and now she wished that, Tizin of Atlantis, she could be surrounded by such guards, their Chieftainess. Vet she could but own herself scarce fitted for the stern hardships of actual warfare as she surveyed the large, strong limbs and hard features of the Amazons and compared them with her own softly-rounded beauties.

In most ancient histories we hear of Amazons, and these women warriors have been usually regarded as mythical, although they were apparently quite equal to the men among the Sarmatians, the Sauromatiz of Herodotus. This race occupied the steppes between the Don and the Caspian, and the women rode, hunted and fought in battle like the men. Indeed on one occasion we learn that Amage, the wife of the dissolute King, accompanied by 120 chosen horsemen, delivered Chersonesus in Taurus from the neighbouring Scythian King, whom she slew with all his followers and gave the kingdom to his son. The Sarmatians appear to be superior to the Scythians, but by speaking a nearly identical language would probably be an allied race.

Thousands of the new arrivals were drafted into the various legions, everything displaying on the part of Toltiah a genius that might well have befitted the prince he was supposed to be, and Chanoc, Nahuasco and experienced leaders were content to approve and aid in everything he did, pleased in his daring scheme and the vast preparations made for carrying it out. Far and wide thousands more supplied the army with food, and great drafts of men were sent to the fords. The mechanical genius of the camp was exercised to discover engines for siege, to be constructed when near the threatened city, for human limbs, though of formidable strength, were powerless against turrets of rock and stone, and those tall warriors whose godlike fronts were so terrible in their iron-muscled power would face men of like mould, Tekthah's veterans and the haughty lords of Zul. The prowess of Shar-Jatal appalled none, but there were men there like Iztli, the dread conqueror of the territory of Trocoatla; the mysterious and mighty Toloc; the gray-haired Colosse and the giant Amal with the seven toes on each foot, who had marched with the Tzan from the North. The witch Pocatepa would raise the legions of the dead against them that black-eyed sorceress with the aquiline nose and voluptuous lips and perchance even Acoa would fight against his Sun-favoured children, Azta and Huitza, and cause a terrible night to overspread them.

In spite of all the great preparations, a certain idleness was already beginning to work mischief, and the chiefs advised a speedy start before the masses should become demoralized or lose their warlike ardour. Each night was a roaring saturnalia, bonfire-lighted; and although reinforcements came in daily, there were also vast desertions. Riots occurred and much wantonness was committed through suppressed energy, yet the leaders could scarce deem such rabble as was most of that vast array prepared sufficiently to conquer Atlantis. All were inexperienced in the storming of walls, and the chiefs feared terrible reverses.

The thousands were ordered to make spear-heads, hatchets and arrow-heads of bone and flint, while legions were raised and practised in warlike manoeuvres. It was at length decided to leave the rabble behind, for the greater part, while the trained legions, with some thousands of hunters and some of the more superior tribes, should cross the river, and, surrounding and crushing the army of Izta, strike terror on the armada and treat for its surrender.

To that end a great concourse of archers, crossing by the fords to the opposite side of the river, so galled the ships (who thus were enduring a storm of missiles from both banks without being able to obtain immunity by the too-near centre of the stream), that they moved away round a bend, sea-ward; and this prevention being gone, a great boom was constructed across the river, made of trees fastened together with hide ropes, below the city, so that the warships might not interfere-with the passage of the troops. This work kept crowds employed with great efforts for some days, and the legionaries played games of chance, exhibited their terrific muscular powers or philandered with the women; hunted, fished in the river and quarrelled. Not a day passed without some rupture, the outcome of idleness; not a night without some wild scene of debauchery. The savages, made to work like slaves on the boom, and losing many lives, deserted by the hundreds. Large rafts were constructed for transporting the troops, who were filled with a vast enthusiasm and were confident of victory, causing a danger by their very confidence. Their leaders were not so ready to leave the city in the face of the armada that ever menaced, for their only trust was in Nezca's guards, the Talascan legions, the Amazons and a few warlike tribes. The rest would only bear the brunt of the carnage and serve as a hindrance to the enemy by disjointed and persistent attacks.

But it was the only thing to be done. The army could not be left longer idle, nor might it be allowed to lose confidence by hesitation. The next day the transportation would commence, >and at the evening camp the warriors reclined around flaring fires, with mirth and wildest enthusiasm. It was a strangely grotesque crowd, encamped over miles of land on plains and among forests. The moon shone bright from a cloudless sky, lighting the great white city and almost hiding the red vapour that rose from Axatlan. The structure of the lower catapult stood black and grim against the sky, completed and formidable, only waiting to be brought into use when its range should be ascertained, for it was not desirable to display its deficiencies by wanton aim: from the city-wall to where the opposite bank showed darkly, floated the tide-swept boom, like the backbone of some mighty cetacean.

Suddenly exclamations arose and the wanton shrieks of women. Far off, but distinctly visible, a great dark shadow swept round the bend of the river with a foamy wave of water around it, from which it rose square and threatening. It came up rapidly, keeping in the middle of the stream, and when the spectators imagined it about to approach the boom at speed it reduced its proportions, and with a great back-churning of waters stood revealed a long, low shape with three bare poles rising from it; and again arose the dismayed cry of "the Tacoatlanta!" as, slightly heaving on the waters, the warship lay as though contemplating the opposing obstacle with its great human-like head.

Then slowly she moved back again and vanished. The moon set and darkness lay on the waters. Men watched all night, and some believed they heard strange sounds from the river, but a kite sent up with a flaming torch attached revealed nothing, and none dared venture on the boom of a night for fear of the great reptiles and the river-demons.

But next morning the huge boat lay opposite the city, and the boom swung down stream by its opposite ends, severed in the middle.

CHAPTER V. THE TACOATLANTA.

WITH shouts of rage, men clustered along the water's edge, and in anticipation of an attack the garrisons went to their several posts; although the Amazons, required to keep the walls while the men took the field, haughtily refused to obey, and held themselves in readiness for an attack.

The slingers, archers and spearmen were in their respective camps, ready for the passage. The hunters and savages, scattered along the banks in a long, dense array, were ordered to be on the alert to oppose any attempt at landing. Some thousands of these untrained but formidable men were in the walls, and harassed the enemy by slinging stones and offal within his bulwarks. Another boom was prepared and made ready to swing across the current, twisted hawsers securing it to the bank; while to the chiefs, Shem propounded a scheme, to cover such enterprise, of floating down some of the vast trunks, with their forests of branches intact, on to the warship, following up the confusion by an attack with boats and rafts.

The foemen hurled abuse the one at the other, roaring fearful threats and vowing horrible tortures to the vanquished; and suddenly a cry spread among the warriors on the banks as the three other vessels were perceived to be approaching, towing rafts full of men. The Mexteo led, her two large sails bellying to the fresh breeze, her many oars sending her along apace, with a swirl of foam around her and astern.

A shout of welcome went up from the Tacoatlanta, a howl of rage from the Talascans. The warships and rafts came on up to the larger vessel, dropping grapplers and swinging to the current by the twisted skin hawsers. On and around them flew a hail of missiles, so that all lay under their shields; while the army of Toltiah, besieged by these comparatively few men, roared and shouted with rage, sending in hot haste to the Axatlans to prepare for an attack by the armada, while large rocks were brought and piled up secretly for the catapults. But few had any knowledge of the use and power of this direful weapon, and had those on the armada known its range they would scarce have dared to venture so closely; yet, untried, it was decided not to use them yet and fruitlessly, preferring to make an attempt to capture one or more of the warships.

Presently the Mexteo and her two smaller consorts shifted their moorings, and, hoisting their sails and aided by their oars, went up the river with the towed rafts. All looked propitious for swinging the boom (which would be received by those archers who were upon the other bank), and for a night-attack on the Tacoatlanta, which lay opposite the waterway; and while great trees were hauled to the water's edge for launching down on her, the warriors who were to attempt the capture were selected.

Akin would lead them, an old, tried chieftain, and used to. the handling of boats, and to him was given full powers as to the conduct of the affair. The warriors were to embark after dark, to wear no armour, so that if thrown into the water they could save themselves by swimming, and were to attack simultaneously at all points.

Word was passed from chief to chief, from the Tzantans of the armies to the tribal Patriarchs, Polemarchs, Centurions and Captains, to hold their men in readiness to cross at any moment; the time probably being when the Tacoatlanta, enmeshed with the trees and violently assailed, would be so engaged that the new boom could be drifted across the river, men being posted to swing it by the hawsers, and others to run swiftly across the moving mass, leap to the shore and secure it with the aid of those others.

All eagerly waited for the night, yet fearing it, because of the demons of the waters and the reptiles that lay beneath them. The gods were propitiated in trust that they might aid the attack, much sacrifices being offered to them; and in the temple of the Moon Azta prayed, invoking all the spirits of night to aid, and such as flew in winged shape.

Thus all were enthusiastic when night came, and with her clouds hid all light. Hundreds of tall dark figures crowded rafts and boats, keeping carefully out of the reach of such slight glow as reached them from the near temple of the Sun, yet which spread not far, being suffered to burn low.

Whispering crowds thronged round the attackers as in darkness they pushed off silently and disappeared like shadows on the bosom of the water, with keen eyes striving to pierce the night to where, from higher up, the floating trees bore down on the vessel, secured to one another in order to be the more formidable. Enormous bats wheeled and squeaked over the stream, and bright insects flew like moving torches of fire, terrifying the watchers. The tension was very great, the legions waiting anxiously the signal of the formation of the boom to prepare for crossing; and sudden and shrill, splitting the silence with a thrilling yell, came a long, tremulous whoop, rising to a shriek.

Shout upon shout answered and drums were beaten for encouragement. From the river came crashes and thuds and the sounds of war. Sparks flew from crossing swords, and it appeared that the warship was not unprepared, for amid the distant storm of sounds rose the heavy splash of oars in regular fall, audible above crashes, shouts and shrieks. Yells came from furious throats, yet to the anxious, thrilling watchers the uproar seemed to be moving farther off.

Yet now how greatly rose thy daring genius, Toltiah! For, revolving in his mind the great benefit of destroying the army of Izta and seizing his stores and engines, he perceived a chance of passage. The Tacoatlanta was drifting down the current, possibly disabled, and messengers, despatched by the prince, flew from post to post and to the engineers of the causeway who waited to let the restrained mass swing across the stream.

Slowly the huge boom, released now from its restraining moorings, felt the current. Levers pushed forth the long trunks of trees, and the swift stream swung it in its joined masses across to the far bank. Already nimble hunters, reckless with haste and excitement and mindful of future reward, had run to the opposite end, and many more, wielding levers, secured more firmly the several portions; and while returning from the attack on the war-ship, on battered rafts or swimming like fishes, dripping warriors with streaming wounds climbed from the river, reporting a futile attempt at capture and the escape of the Tacoatlanta, the mighty boom was signalled secure, and over it began the passage of the army of Toltiah.

Through the barricades they poured, vanishing into the gloom; first Nezca with the guards, then the Amazons, and then hundreds of long-haired, skin-clad hunters. Many, overcome with excitement, and valiant by reason of much company, plunged into the river, and soon the churning water was alive with heads. With spear and sword strapped to their backs they swam with long powerful strokes, and hundreds of the savage tribesmen, from far up the banks, emulating them, plunged in and braved the waves.

The breast of the leader was full of hope and joy. In imagination he saw the defeat of Izta and rejoiced in the welcome necessaries captured; he saw the surrender of Budil and the armada and then the triumphant march to the Throng of Atlantis. Then a glowing light sprang up from down the river as a war-kite sailed slowly up, carrying a blazing torch, and by its light showed an appalling spectacle. The Tacoatlanta was returning! The noise made by the passing army had reached the ears of her crew, Shar-Jatal's myrmidons and formidable opponents, and with eager oars and filled sails she was coming up with rapidity.

The passage of the army stopped, the nearest to either shore going onward or hastily returning; while another light leaped from the bows of the warship as a bonfire was ignited on a protruding platform.

A murmur rose like the sound of a storm, and Toltiah and all the chiefs beat their breasts with clenched fists, and growled in their throats. The archers were ordered to send their shafts into the galley while men flew in eager haste to the large catapult, crying to the gods to be propitious, regulating the range and directing their aim. A rock was placed on the beam, the levers tightening the cords at the opposite end until they sang. The huge missile, released, flew forth, hurled with gigantic power by the beam, and falling into the current astern and beyond the warship, raised a watery column that gleamed golden in the blaze of the bonfire.

But straight at the boom, fretted with moving forms, the great hulk rushed, and struck. For an instant she stopped dead, her foremast falling with a crash, the bonfire flying in lines of light far in advance. A terrible shock convulsed her and the boom, and by the faint light of the far-soaring kite the watchers could see the causeway was cleared of men as it slowly swayed forward, and then, rushing with the stream, parted with a great rending, and drifted downwards, divided, the Tacoatlanta slowly forging ahead. With gathered speed she went onwards again, and dark forms in commotion were seen on her bulwarks busy among the floating heads, stabbing at them with oars, smashing them with clubs, splitting them with swords and spears and axes tied to poles

Howls of rage rose from both shores at witnessing this daring deed. The Amazons yelled their long, clear war-whoop, and a formidable sound of beaten bucklers arose as the warriors smote them with rage. The leaders held a consultation, fearful of the approach of the army of Izta that would destroy the army on the farther bank. It was decided to move in force to the fords, where, wading to their armpits, they might have a chance of boarding and capturing the vessels there, the archers killing the rowers and slaughtering the crew by pouring their shafts through the port-holes.

All lay on their arms till dawn, when, with the first light, the divided arrays poured flights of missiles on the Tacoatlanta as she lay between them, preventing attempts to repair the damage of the fallen mast and compelling all to lay beneath their shields. Azta, lying in an open palanquin, watched the dark vessel and cursed her by all the gods of Zul and the demons of darkness. The catapults were prepared for use, not being understood by the enemy, who had not fathomed the meaning of that watery column that rose so near them in the night-attack, and such even as perceived it judging it to be a Spirit risen from the wave. Now three of them raised their dark beams from the walls, one below and one above the city, and the large one that had fired the bolt in the night, the course of which was influenced by other wedges of rock placed beneath.

To an extent the presence of the army on the farther shore was comforting, for the ships could not land men to revictual the larders, and soon all believed the provisions failing would cause a retreat if all else failed, for the fish had two much food to eat to venture on a hook, the bodies of many warriors feasting them to the full. The march to the fords was prepared for, where it was hoped to find that the enemy had attempted to land, and consequently, wearied with fighting and perchance in disorder, would fall an easy prey.

Camped around fires, the warriors were breaking fast, when a shout apprised all that something claimed attention. The Mexteo was coming down the river.

Azta perceived her approach first, and her quick mind revolved a scheme. She rose up in her palanquin, raising her voice in command to the hastening warriors, her proud head raised high and her eyes flaming with enthusiasm. "To the catapults!" she cried; and standing to her full majestic height at the added height of the shoulders of tall negroes, waved her arm with a sweep from horizon to horizon, crying that the whole world lay before Huitza and all who followed him.

Shouts answered her, the warriors declaring her to be a goddess, while the artillerists manned the engines, and trumpets and drums sounded all over the city. The missiles were fitted, and as the galley arrived opposite the machine above the city, a huge bolt flew through the air and plunged into the waves under her beam, sending a mound of water over her and the oars into inextricable confusion.

A roar of triumph rose from Talascan and the thousands beyond the walls who witnessed this. The boat, under confused orders, slowly drifted into the very range, and the artillerists, shrieking with eagerness and sweating at their work, fitted another missile. The army on the farther shore raised howls of gleeful jubilation, and the crew of the Tacoatlanta ventured from under their shields to watch what might happen.

With a twang and a whiz the rock sped. The breathless thousands watched it as it flew, presenting all sorts of shapes in its gyrating path. It fell with a crashing thud on the bulwarks, and a shriek of terror, drowned in another prolonged burst of exultation, rose as, amid splinters and blood, the water swirled into the breach. The warship lurched horribly, but the shouts of triumph drowned the shrieks of despair of her heavily-harnessed crew, which, falling down the inclining deck, fearfully increased the list that the flooding waves gave the vessel. With a lurch forward and a heavy roll she turned over, the eddies swirling around her; and only her sails on the water, like two great domes with the air they enclosed, kept her from completely turning over.

The Tacoatlanta with grapplers down watched the dire sight. Tentativeness changed into the wildest dismay on beholding the unfortunate Mexteo wallow and overturn. But for Budil and other leaders the crew would have surrendered at once, fearful of such fate; but these, with threats and blows, forced them to hoist the sails, while, abandoning the grapplers, the oars beat the water.

Within range of the catapult below the city a vast missile flew forth, striking the mainsail and tearing in from the mast, which snapped at the foundations and fell, drenching all with bounding waves, heaving the vessel greatly on the swelling wash and mingling the oars in confusion.

Cries of terror arose, drowned by irrepressible shouts of enthusiasm from the army. Some of the galley-slaves, mad with terror, leaped overboard and dived deeply so that they drowned; upon the catapult a man mounted, waving a cloak and gesticulating towards the artillerists, who wound down the great beam preparatory for another shot. All down the barricades clustered thousands of warriors, and now they began to stream through on to the waterway. On the pedestal of the colossus Mele, a water-god supporting one end of the architrave shadowing the steps of the river gate, stood Toltiah; on the top step was Azta, standing as a goddess in her palanquin, jubilant with triumph, who had travelled along the battlements in glorious victory.

Ignorant of the powers of the dire engine, the enemy believed it to be able to follow them up and sink the ship, and terribly alarmed by the startling warning they had received, hauled down the remaining sail; while a cloak was waved in answer to the one on shore, as the great warship sullenly rowed up to the waterway to surrender.

CHAPTER VI. THE FIRST STEP OF FAME.

ENTHUSIASTIC crowds watched the galley, as, towing the hamper of two masts she came up and struck. There was no need for grapplers: hundreds of hands clutched and held her, warriors swarmed over the bulwarks, and but for the authority of the chiefs she would have been sunk by sheer weight of numbers.

The crew landed, among them being a few of the notables of Zul, come on what they had deemed a pleasurable trip. Not a few were wounded by the fury of the night-surprise and the ceaseless missiles of the army; most of these were secretly murdered and with those who were already dead thrown overboard; while the warriors, enraged by the mischief wrought, hanged the Captain Budil from his own masthead. The body, barbarously profaned in the market-place, had the head struck off, the which was sent by a tall hunter to be cast into Zul in token of what would befall when Toltiah were master. A score of the Mexteo's crew, clinging to their wreck, were killed with sling-shots and arrows; while, under pretence of enrolment with the conquering legions, all the crew of the Tacoatlanta, together with those notables, were overcome by violence and murdered in a place beyond the walls.

And now all was bustle again and a rush of preparation for the interrupted passage of the army to be continued before the other war-ships might appear. All thoughts of gratitude to the gods were forgotten. Boats carried ropes across the river from bank to bank, and the wrecks of the two booms were by them hauled together and secured. Nezca's spies, looking in far-reaching circles for Izta, gave yet no sign of his approach; and now, crowding the boom and on rafts and boats, and thousands swimming, the army crossed; and the menace of the approaching one, albeit disciplined and terrible, lost its sting. The ill-fated Mexteo, smashed and waterlogged, was drawn up to the waterway and secured, to be raised again as soon as preparations were ready; while a catapult was fitted on the Tacoatlanta and her masts replaced, the body of Budil being suspended by the heels from the foremast. Her management was left to the Talascans, who were used to the sea and river, and Akin commanded them.

The boom was crowded with arrogant conquerors, and in the sunny streets of Talascan women and children swarmed again, the fear of violence removed. They laughed and chatted and gazed with awe on the tall catapults, revering them as gods. To the populace the name of Huitza was a power in itself, for besides being that of a popular hero, it was, with Tekthah and Rhadaman, one of the three that reminded the people of the old days and the glory of the land. Shar-Jatal was hated as a brother who had objectionably seized a sire's power, and Izta, his right hand, was hated likewise for his upstart insolence and tyrannies; while Japheth was lauded with mighty enthusiasm, being called saviour of Talascan and Wielder of the bolts of the gods.

But on Azta and Toltiah the regards of the people were poured with a frenzied enthusiasm, and images were made of them and sold to be worshipped. And now with levers and inflated skins, (the people hauling on ropes,) the Mexteo was turned on her proper side, and, the water being bailed out, floated in ordinary fashion upon the water, the breach being repaired by skilled men and everything set in order. There were many bodies of drowned warriors within her, but these were flung with scant ceremony to the waves, while jubilant Talascans ran freely from bank to bank over the causeway. On this a catapult was constructed to hurl a volley of missiles, but at the first trial the levers broke and hurried violent death to many, nor was it until much time had passed that confidence in it was restored.

In the darkness of the night one of the two warships by the fords came down the river to see if aught had occurred, and dimly perceiving the Tacoatlanta, rowed up to her. Whose crew, also understanding what the crew of the galley took to be the case, permitted the approach, and grappling her, made an easy capture; and thus Toltiah possessed three of the four vessels of the armada, and the people rejoiced greatly.

With the dawn of the next day the three warships sailed up the river, the great Tacoatlanta displaying at her fore the ill-fated Budil, dead; and at noon perceived where the rafts lay, and the other galley. The landing at the fords had been barricaded with pointed stakes and piles of wood, which in places showed where the devices of the enemy had fired it. These, believing the approaching ships to be full of their friends, shouted to them, and the crews replied; the while surrounding the galley, which was named the Tzan, the one captured being named Tizin. The vessel, being thus hemmed in, would have surrendered, but the savage attackers would take no tameness like this, and pouring over the sides, killed every man on board. Yet they too suffered in a great measure, for the Tzan's crew fought furiously as long as there was a man left.

The Axatlans and all those which were sent down to aid them were greatly enthusiastic seeing how things ran, and began to pour missiles upon the crowded rafts, of which there were three. These, with hot haste, began to make for the farther bank, but the crew of the Tacoatlanta, perceiving this, prepared to fall upon them, fitting also a missile on the catapult. This plunged between two of them, causing a great wash of water and much consternation; but they redoubled their efforts to escape as the huge galley bore down on them.

She struck the first with a devastating crash, again sending the foremast, with its horrid burden, overboard, with much havock to the bulwarks; but cutting this adrift, continued on, and by the crew going astern, in order to raise the long bows, the second raft was completely submerged beneath the mighty bulk of the vessel.