Traditions of Lancashire by John Roby

THE GREY MAN OF THE WOOD;

OR,

THE SECRET MINE.

"Humph. Say, what art thou that talk'st of

kings and queens?

K. Hen. More than I seem, and less than I was born

to;

A man at least, for less I should not be;

And men may talk of kings, and why not I?

Humph. Ay, but thou talk'st as if thou wert a king.

K. Hen, Why, so I am, in mind, and that's enough.

Humph. But if thou be a king, where is thy

crown?"

—King Henry VI.

Waddington Hall, the site of the following legend, says Pennant, "is a stone house, with some small ancient windows, and a narrow winding staircase within, now inhabited by several poor families; yet it formerly gave shelter to a royal guest. The meek usurper, Henry VI., after the battle of Hexham, in 1463, was conveyed into this county, where he was concealed by his vassals for an entire twelvemonth, notwithstanding the most diligent search was made after him. At length he was surprised at dinner at Waddington Hall, and taken near Bungerley Hippingstones in Clitherwood. The account which Leland gives from an ancient chronicle concurs with the tradition of the country, that he was deceived—i.e. betrayed—by Thomas Talbot, son and heir to Sir Edmund Talbot, of Bashal, and John his cousin, of Colebry. The house was beset; but the king found means to get out, ran across the fields below Waddow Hall, and passed the Ribble, on the stepping-stones, into a wood on the Lancashire side, called Christian Pightle, but being closely pursued, was there taken. From hence he was carried to London, in the most piteous manner, on horseback, with his legs tied to the stirrups. Rymer has preserved the grant of a reward for this service, of the estates of Sir Richard Tunstall, a Lancastrian, to Sir James Harrington, by Edward IV., dated from Westminster, July 9th, 1465."

THE GREY MAN OF THE WOOD; OR, THE SECRET MINE.

At that time Waddington belonged to the Tempests, who inherited it by virtue of the marriage of their ancestor, Sir Roger, in the reign of Edward I., with Alice, daughter and heiress of Walter de Waddington. An alliance had just been made between the Tempests and the Talbots. It may be presumed, that in order to save their estates (which they afterward were suffered quietly to possess), they agreed with Sir James to give up the saintly monarch, which was the reason that the latter had the reward for what the grant calls "his great and laborious diligence in taking our great traitor and rebel, Henry, lately called Henry VI."

Far different was the conduct of Sir Ralph Pudsey, of Bolton Hall, where the king was concealed for some months prior to his appearance at Waddington. Quitting Bolton, probably from some apprehension that his retreat was in danger of being discovered, he left behind him the well-known relics which are still shown to the curious. These are a pair of boots, a pair of gloves, and a spoon. The boots are of fine brown Spanish leather, lined with deer-skin, tanned with the fur on; about the ankles is a kind of wadding under the lining, to keep out wet. They have been fastened by buttons from the ankle to the knee; the feet are remarkably small (little more than eight inches long); the toes round, and the soles, where they join to the heel, contracted to less than an inch in diameter.

The gloves are of the same material, and have the same lining; they reach up, like women's gloves, to the elbow; but have been occasionally turned down, with deer-skin outward. The hands are exactly proportioned to the feet, and not larger than those of a middle-sized woman. In an age when the habits of the great, in peace as well as war, required perpetual exertions of bodily strength, this unhappy prince must have been equally contemptible from corporeal and from mental imbecility.[54]

A well adjoining to Bolton Hall still retains his name. He is said to have ordered it to be dug and walled round for a bath; and it is much venerated by the country people to this day, who fancy that many remarkable cures have been wrought there.

It is not generally recorded that the science of alchemy was much encouraged by the royal visionary. Though he had commissioned three adepts to make the precious metals, and had not received any returns, his credulity remained unshaken, and he issued a pompous grant in favour of three other alchemists, who boasted that they could not only transmute metals, but could impart perpetual youth, with unimpaired powers both of mind and body, by means of a specific called the Mother and Queen of Medicines, the Celestial Glory, the Quintessence or Elixir of Life. In favour of these "three lovers of the truth, and haters of deception," as they styled themselves, Henry dispensed with the law passed by his grandfather, Henry IV., against the undue multiplication of gold and silver, and empowered them to transmute the precious metals. This extraordinary commission had the sanction of Parliament; and two out of the three adepts were the heads of Lancashire families—viz., Sir Thomas Ashton of Ashton, and Sir Edmund Trafford of Trafford. These worthy knights obtained a patent for changing metals, 24 Hen. VI. The philosophers, probably imposing upon themselves as well as others, kept the king's expectation wound up to the highest pitch; and in the following year he actually informed his people that the happy hour was approaching when, by means of the stone, he should be able to pay off his debts[55]

With regard to the prophecy or denunciation made by him against the Talbots, recorded in our legend, Dr Whitaker observes,—"Something like these hereditary alternations of sense and folly might have happened, and have given rise to a prophecy fabricated after the event; a real prediction to this effect would have negatived the words of Solomon,—'Yea, I have hated all my labour which I had taken under the sun; because I should leave it unto the man that shall be after me; and who knoweth whether he shall be a wise man or a fool?'

"This, however, is not the only instance in which Henry is reported to have displayed that singular faculty, the Vaticinium Stultorum."[56]

In 798, this place was noted for the defeat of Wada, the Saxon chief, by Aldred, king of Northumberland. He was one of the petty princes who joined the murderers of King Ethelred. After this overthrow he fled to his castle, on a hill near Whitby, and dying, was interred not far from the place. Two great pillars, about twelve feet asunder, mark the spot, and still bear the name of "Wada's Grave."

It was on a bright and glorious summer evening, in the year 1464, while the red glare of sunset was still in the west, and a wide blush of purple passed rapidly over the distant fell and the blue and heath-clad mountain, that a group of labourers were returning from their daily toil through the forest glades that skirt the broad and beautiful Ribble below Waddow. Some of them were of that class called hinds, paying the rents of their little homesteads by stated periods of service allotted to each; in this respect differing but little from the serfs and villains of a more remote era, their toil not a whit less irksome, though their liberty, in name at least, was less under the control and caprice of their lord.

Two of the peasants loitered considerably behind the rest, seemingly engrossed by a conversation too interesting or too important for the ears of their companions. The elder of the speakers was clad in a coarse woollen doublet; a belt of untanned leather girt his form; and on his head was a cap of grey felt, without either rim or band. His gait was heavy and slouching. Strong, tall, and muscular, he stooped considerably; but less through age and infirmity than from the laborious nature of his occupations. His companion, younger and more vivacious, was distinguished by a goodly and well-thriven hump, and by that fulness and projection of the chest which usually characterise this species of deformity. His long arms nearly trailed to the ground as he walked; huge and sprawling, they seemed to have been originally intended as an attachment to a frame of much more gigantic proportions. His face had that peculiar form and expression which always, more or less, accompany this kind of malformation. Wide, large, angular; the chin sharp and projecting, supported on the breast; the whole head scarcely rivalling the shoulders in height and obliquity. His disposition was evidently wayward and irascible, and a keen satirical humour lurked in every line of his pallid visage; generally at war with his species, and ready to act on the defensive; snarling whenever he was approached, and always anticipating gibe and insult from his fellows.

"Weary, weary,—ay, as a tom-fool at a holiday feast," said the hunchback to his companion. "Spade and axe have I lifted these twenty years, and what the better am I o' the labour? A groat's worth of wit is worth a pound o' sweat,' as my dame says. I'll turn pedlar some o' these days, and lie, and cheat, and sell."

"Ay, Gregory," interrupted the other, "thee'd sell thy own paws, if so be they'd fetch a groat i' the market; but then, I warrant, the dame at the hall would lack her henchman at the churn."

"Tut! I care for nought living but my worthless carcase," replied the hunchback, surveying his own person. "Why should I? there's nought living that cares for me. Sure as fate, if a' waur dead beside, we'd ha' curran' baws i' the pot every day. What a murrain is it to this hungry maw whether Ned Talbot, or Joe Tempest, or any other knave o' the pack, tumbles into his berth, or is put to bed wi' the shovel, a day sooner or later. He maun budge some time. Faugh! how I hate your whining—your cat-a-whisker'd faces, purring and mewling, while parson Pudsay says grace over the cold carrion; he cares not if it waur hash'd and stew'd i' purgatory, so that he gets the shrift-money. Out upon't, Ralph, out upon it! this mattock should delve a' the graves i' the parish, if I could get a tester more i' my fist."

"Thou murdering tyke! wouldst dig my grave?"

"Ay," shouted Gregory with a grin, displaying a huge double crescent of white teeth, portals to a gulf, grim, hideous, and insatiable; "ay, for St Peter's penny."

"And leave me to knock at the gate, and never a doit to pay the porter?"

"Thou shouldst cry and howl till doomsday, though my pouch had the keeping of a whole congregation of angels.

"Keep out o' my way, cub—unlicked brute!" cried the infuriate Ralph; "keep back, I say, or I may send thee first on thine errand to St Peter. Take that, knave, and"—

But the malicious hunchback stepped aside, and the blow, aimed with a hearty curse at this provoking lump of deformity, fell with a murderous force upon a writhen stem, which bore witness to the willing disposition with which the stroke was dealt. Gregory was laughing and mocking all the while at the impotent wrath of his companion.

"A groat's worth for a penny, I'm not yet boun' for St Peter's blessing, though, old crump-face!" cried the learing impertinent, one thumb between his teeth, and the little finger thrust out in its most expressive form of derision and contempt.

"Hush—softly, prithee," said the offended party, his anger all at once under the influence of a more powerful feeling. He stood still, in the attitude of listening, earnestly bending forward with great solicitude and attention.

He pointed to some object just visible through the arches of the wood, in the dim twilight.

"There is the grey man o' the mine again, as I live, Gregory; we'd best turn back, for our companions are gone out of hear ing." The terrified rustic was preparing for immediate flight, but Gregory caught him by the belt.

"How now! stand to thy ground, man," said he; "I've had speech at him not long ago. We came upon one another suddenly, to be sure, and I could not well escape, so I stood still. He did the same, shook his pale and saintly face, and, with a wave o' the hand, bade me pass on."

"But look thee," replied the other, "I'm bodily certain he walks without a shadow at his tail. See at that big tree there; why, the boughs bend before he touches 'em, like as they were stricken wi' the wind. I declare if the very trees don't step aside as if they're afraid of him. I'll not tarry here, good man."

Disengaging himself from the other's gripe, Ralph ran through the wood in an opposite direction, and was soon out of sight. A loud shout from Gregory followed him as he fled, which only served to quicken his speed; and the hunchback was left alone. The figure which was the moving cause of this cowardly apprehension almost immediately disappeared behind a projecting crag, at the base of which grew a thick skirting of underwood; but Gregory pursued cautiously in the same direction. He had heard strange stories of demons guarding heaps of treasure; and it was currently reported that in former times a mine had been secretly worked in these parts for fear of discovery; all mines yielding gold and silver, so as to leave a profit from the working, being considered as "mines royal," and regarded as the property of the king.[57] Gregory's prevailing sin was avarice; and oftentimes this vice put on the appearance of courage, by rendering him daring for its gratification, though at heart a coward. He thought that if the treasure were once within his grasp neither man nor demon should regain it.

For a short time past this part of the forest had been commonly reported as the haunt of a spectre, in the likeness of a man clad in grey apparel, who by some was supposed to be an impalpable exhalation from a concealed mine existing in the neighbourhood. It is well known that these places are generally guarded by some covetous demon, who, though unable to apply the treasures to their proper use, yet strives to hinder any one else from gaining possession.

Gregory had once encountered it unexpectedly, face to face, but he did not then follow—surprise and timidity preventing him. He, however, resolved that, should another opportunity occur, he would track the spectre to its haunt, and by that means find out the opening and situation of the mine.

He now crept slowly towards the crag, behind which the figure had retired. Looking cautiously round the point, he again saw the dim spectral form only a few yards distant. Suddenly he heard a low whistle, and the next moment the mysterious figure had disappeared—not a vestige could be traced. He thrust his huge head between the boughs for a more uninterrupted survey, but nothing was seen, save the bare escarpment of the rock, and the low bushes, behind which the phantom had, a moment before, been visible. Though somewhat daunted, he crept closer to the spot, but darkness was fast closing around him, and the search was fruitless.

"Humph!" said the disappointed treasure-hunter audibly; "daylight and a stout pole may probe the mystery to the bottom. I'll mark this spot."

"Mark this spot," said another voice at some distance, repeating his words like an echo. The rock was certainly within "striking distance," and it might have been this accident which lent its aid to the delusion.

Gregory could not withstand so apparently supernatural an occurrence. He took to his heels, driven fairly off the field; nor did he look behind him until safely entrenched before a blazing fire in the kitchen at Waddington Hall.

"Out, ill-favoured hound!" said a serving wench, who was stirring a blubbering mess of porridge for supper. But Gregory was not in the humour to reply: he sat with one long lean hand under his chin, the other hung down listlessly to his heels, which were drawn securely under the stool on which he sat. His thoughts were not on the victuals, though by long use and instinct his eyes were turned in that direction.

"Thee art ever hankering after the brose, thou greedy churl!" continued the wench, wishful to goad him on to some intemperate reply.

But Gregory was still silent. At this unwonted lack of discourse, Janet, who generally contrived to bring his long tongue into exercise, was not a little astonished. It needed no great wit, any time, to set him a-grumbling; for neither kind word nor civil speech had he for kith or kin, for man or maid.

Looking steadfastly towards him, she struck her dark broad fists upon her hips, and, in a loud and contemptuous laugh, abruptly startled the cynic from his studies. He eyed her with a grin of malice and vexation.

"Thou she-ape, I wonder what first ye'arn made for; the plague o' both man and beast,—the worst plague that e'er Pharaoh waur punished wi'. Screech on; I'll ha' my think out, spite o' thy caterwauling."

"Thou art a precious wonder, Master Crab. Squirt thy verjuice, when thou art roasting, some other way. I wonder what man-ape thy mother watch'd i' the breeding. She had been special fond o' children, I bethink me."

"And what knowest thou o' my dame's humours, thou curl-crop vixen?" said Gregory, unwarily drawn forth again from his taciturnity. "How should her inclinations be subject to thy knowledge?"

"She rear'd thee!" was the reply.

Two other hinds belonging to the household, who were watching the issue of the contest, here joined in a loud clamour at the victory; and Gregory, dogged with baiting, became silent, scowling defiance at his foe.

Waddington Hall was at that period a building of great antiquity. Crooks, or great heavy arched timbers, ascending from the ground to the roof, formed the principal framework of the edifice, not unlike the inverted hull of some stately ship. The whole dwelling consisted of a thorough lobby and a hall, with a parlour beyond it, on one side, and the kitchens and offices on the other. The windows were narrow, scarcely more than a few inches wide, and, in all probability, not originally intended to contain glass.

The chimneys and fireplaces were wide and open; the apartments, except the hall, low, narrow, and inconvenient, divided by partitions of oak, clumsy, and ill-carved with many strange and uncouth devices. The hall was, on the right of the entrance, lighted by one long low window; a massy table stood beneath. The fireplace was on the opposite side, occupying nearly the whole breadth of the chamber. A screen of wainscot partitioned off the lobby, carved in panels of grotesque workmanship. Beyond the hall was the parlour, furnished as usual with an oaken bedstead, standing upon a ground-floor paved with stone. In this dormitory, the timbers of which were of gigantic proportions, slept Master Oliver and Mistress Joan Tempest,—the latter not a little given to that species of uxorious domination which most wives, when they apply themselves heartily to its acquisition, rarely fail to usurp.

"Here," says Dr Whitaker (this being the general style of building for centuries, and scarcely, if at all, deviated from),—"here the first offspring of our forefathers saw the light; and here too, without a wish to change their habits, fathers and sons in succession resigned their breath. It is not unusual to see one of these apartments now transformed into a modern drawing-room, where a thoughtful mind can scarcely forbear comparing the past and present,—the spindled frippery of modern furniture, the frail but elegant apparatus of a tea-table, the general decorum, the equal absence of everything to afflict or to transport, with what has been heard, or seen, or felt, within the same walls,—- the logs of oak, the clumsy utensils, and, above all, the tumultuous scenes of joy or sorrow, called forth, perhaps, by the birth of an heir, or the death of an husband, in minds little accustomed to restrain the ebullitions of passion.

"Their system of life was that of domestic economy in perfection. Occupying large portions of his own domains; working his land by oxen; fattening the aged, and rearing a constant supply of young ones; growing his own oats, barley, and sometimes wheat; making his own malt, and furnished often with kilns for the drying of corn at home, the master had pleasing occupation in his farm, and his cottagers regular employment under him. To these operations the high troughs, great garners and chests, yet remaining, bear faithful witness. Within, the mistress, her maid-servants, and daughters, were occupied in spinning flax for the linen of the family, which was woven at home. Cloth, if not always manufactured out of their own wool, was purchased by wholesale, and made up into clothes at home also."[58]

This is a true picture of the simple habits of our ancestors, and will apply, with little variation, to the scene before us.

Here might be seen the carved "armoury,"—the wardrobe, bright, clean, and even magnificent. On the huge rafters hung their usual store of dried hams, beef, mutton, and flitches of bacon. In the store-room, great chests were filled to the brim with oatmeal and flour. All wore the aspect of plenty, and an hospitality that feared neither want nor diminution.

In one corner of the hall at Waddington sat Mistress Joan, her only daughter Elizabeth, and two or three female domestics.

They had been spinning, trolling out the while their country ditties with great pathos and simplicity.

Being nigh supper-time, the group were just loitering in the twilight ere they separated for the meal.

"Come, Elizabeth," said her mother, "lay thy gear aside; the strawberries are in the bowl, and the milk is served. Supper and to bed, and a brisk nap while morning."

The dame who addressed her was a perfect specimen of the good housewife in the fifteenth century. She wore a quilted woollen gown, open before, with pendant sleeves, and a long narrow train; a corset, fitted close to the body, unto which the petticoats were attached, and a boddice laced outside. She wore the horned head-dress so fashionable towards the close of the fourteenth century, and at that time still in use, giving the head and face no slight resemblance to the ace of hearts. An apron was tied on with great care, ornamented with embroidery of the preceding century. Her complexion, was dark but clear, and her eyebrows high and well-arched. Her mouth was drawn in, raised slightly on one side,—a conformation more particularly apparent when engaged in scolding the maids, or in other similar but indispensable occupations.

Her gait was firm, and her person upright. Her age—ungallant historians we must be—was verging closely upon sixty; yet her hair, turned crisp and full behind her head-dress, showed slight symptoms of the chill which hoar and frosty age, sooner or later, never fails to impart.

Elizabeth Tempest was young, but of a staid and temperate aspect, almost approaching to that of melancholic. Her complexion, pale and sallow; her eye full, dark, and commanding, though occasionally more languor was on it than eyes of that colour are wont to express. She wore a long jacket of russet colour, and a crimson boddice. Her hair, turned back from her brow, hung in dark heavy ringlets below the neck, which, though not of alabaster, was exquisitely modelled. In person she was tall and well-shapen, and her whole manner displayed a mind of no ordinary proportions. She was well-skilled in household duties, her mother having an especial desire that her daughter should be as notable and thrifty as herself in domestic arrangements.

"Elizabeth," or "Elspet," as she was indiscriminately called, cared little about her reputation touching these important functions. She could sing most of the wild legendary ballads of the time; her rich full voice had in it a sadness ravishingly tender and expressive, more akin to woe, and the deep untold agony of the spirit, than to lightness and mirth, in which she rarely indulged.

"Give us one of thy ditties ere supper," said the dame, who was just then laying aside her implements in the work-press. "I wonder thy father does not return. The roofs of Bashall ring with louder cheer than our own, I trow. He is playing truant for the nonce, which is dangerous play at best."

"Is he now at our cousin Talbot's?" inquired the maiden, with a look of more than ordinary interest.

"If he be not on the way back again," returned the dame, as though wishful to repress inquiry.

"The woods are not safe so late and alone. Comes he alone, mother?"

"Alone! Ay,—and why spierest thou?" The dame looked wistfully, though but for a moment, on her daughter; then changing her tone, as if to recommend a change of subject, she cried—

"Come, ha' done, Elspet; we will wait no longer than grace be said. Now to thy song."

The maiden began as follows:—

1.

"There sits three ravens on yon tree,

Heigho!

There sits three ravens on yon tree,

As black, as black, as they can be.

Heigho, the derry, derry, down, heigho.

2.

"Says the first raven to the other,

Heigho!

Says the first raven to the other,

'We'll go and eat our feast together.'

Heigho, &c.

3.

"'It's down in yonder grass-grown field,

Heigho!

It's down in yonder grass-grown field,

There lies a dead knight just new killed.'

Heigho, &c.

4.

"There came a lady full of woe,

Heigho!

There came a lady full of woe,

And her hands she wrung, and her tears did flow.

Heigho, &c.

5.

"She saw the red blood from his side,

Heigho!

She saw the red blood from his side,—

'And it was for me my true love died!'

Heigho, &c.

6.

"'Oh, cruel was my brother's sword,

Heigho!

Oh, cruel, cruel, was his sword,

But sharper the edge of one scornful word.'

Heigho, &c.

7.

She laid her on his bosom cold,

Heigho!

She laid her on his bosom cold,

While adown his cheek her tears they rolled.

Heigho, &c.

8.

"No word she spake, but one sob gave she,

Heigho!

No word she spake, but one sob gave she:

Said the ravens, 'Another feast have we,

And long shall thy rest and thy slumbers be.'

Heigho, the derry, derry, down, heigho!"

At the concluding stanza in walked Oliver Tempest, who, as if to avoid notice, sat down, without uttering a word, in a dark corner at the opposite side of the hall. He looked moody, and wishful to be alone. Joan, for a while, forbore to interrupt his reverie, and the females finished their evening repast in silence.

"Is Sir Thomas Talbot yet returned from the Harringtons?" inquired the dame soon after, with an air of assumed carelessness.

"He returned an hour only ere I departed."

Another pause ensued.

"And his son Thomas, comes he back from the Pudsays of Bolton? Does the gentle Florence[59] look on him kindly, or is the wedding yet delayed?"

"I know not," was the brief reply. After a short pause he continued—"The wanderer has left Bolton, I learn, and, 'tis said, he bides at Whalley."

Here he cast a furtive look at the domestics, and then at his wife, as though wishful to ascertain if others had understood this intimation.

"Nay, some do boldly affirm that he has been seen i' these very woods," continued he, lowering his voice to a whisper.

"Which Heaven forefend!" said the wary dame. "I would not that he should draw us down with him to the same gulf wherein his fortune is o'erwhelmed. No luck that woman ever brought him from o'er sea, and now she's gone"—

"They say that she hath escaped to Flanders," said Oliver, hastily interrupting her.

"I wish he had been so fortunate," said the dame; "what says our cousin Talbot?"

"Hush, dame; our plans are not yet ripe. But more of this anon."

Elizabeth listened with more interest than usual. Every word was eagerly devoured, and with the last sentence she could not forbear inquiring—

"And Edmund?—surely Edmund Talbot is not"—

"What?" sternly inquired her father; "what knowest thou of—? Said I aught whereby thou shouldst suspect us?"

"Hush, thou foolish one," said the more cautious dame; "thy thought alone was privy to it, and so no more. There be others listening."

The moonbeams now crept softly into the chambers, whither, too, crept the weary household; the master and his wife remaining for a short time together in the hall, apparently in earnest discussion. But Elizabeth retired not to her couch. She passed softly through the courtyard, looking round as though in search of some individual. This proved to be the hunchback Gregory, whom she found esconced behind a peat-stack in marvellous profundity of thought. With a soft step, and one finger raised to her lips, she gently tapped him upon the shoulder.

Looking round, he saw her gesture and was silent.

"Gregory, art thou honest?" she inquired, in a whisper.

"Why, an' it be, Mistress Elspeth, when it suits with my discretion; that is, if discretion be none the worse for it, eh?"

"Thou art ever so, Gregory; and yet"—

"If ye want honesty, eschew a knave, and catch a fool by the cap. None but fools worry and distemper themselves with this same pale-faced whining jade, that will leave 'em i' the lurch at a pinch, Dame Honesty, forsooth. More wit, more wisdom; and there is a plentiful lack of wit in your honest folk," continued the cynic, as though pursuing a train of thought to its ultimate development.

"Gregory, thou art not the rogue thee seems. I think beneath that rough and captious speech there lurks more honesty than thou art willing to acknowledge. Thou hast been angered with baiting until thou wouldst run at every dog that comes into the paddock, though he fawned on thee, and were never so trusty and well-behaved."

Gregory was silent. He looked upwards to the bright moon and the quenched orbs that lay about her path. Again Elizabeth whispered, first looking cautiously around—

"Wilt do me a service?"

"Ay, for hire," he quickly answered.

"If thine errand is done faithfully, thou mayest get more largess than thou dream'st of."

"Ye want a spoon belike, that ye soil not your delicate fingers?"

"Ay, Gregory, an' thou wilt, we 'll first use thee."

"And then the spoon shall be broken, I trow. Well, if I am a spoon, I'll be a golden one, and I shall be worth something when I'm done with. Understand ye this, fair mistress?"

"Yes, knave; and thou shalt have thy reward."

"What! I shall swing the highest, eh?"

"Peace; I want a messenger. Take this."

"Not treason, I trow," said Gregory, as he eyed the billet with a curious but hesitating glance.

"Go by the nearer path to the wood. Where the road divides to the ford and the farther pastures; take the latter, then turn to the right, where the old fir-tree rises above the rock. Walk carefully through the bushes at the base of the crag. Near unto a sharp angle of the rock thy path will be stayed by a fallen tree. Grasp this with both hands, and whistle thrice. I know thou canst be trusty and discreet. Yet remember thy life is in my power shouldst thou fail." She paused, pointing significantly at the billet. "Now hasten. Bring back, and to me only, what shall be committed to thy care. I will expect thee at my window by midnight."

Now it so happened that this precise spot was identified to Gregory's apprehensions with the very place where his attention had that night been directed by the mysterious disappearance of the grey man of the mine. He would certainly have preferred making his second visit by daylight; but needs must when a woman drives, especially when that woman is a mistress, and gold is the goad. Besides he might perchance get a glimpse of the treasure; and his pockets were wide and his gripe close. Thus stimulated to the adventure, he addressed himself to perform her behest.

The night was singularly clear, and the shadows lay on his path, still and beautifully distinct. As he hastened onwards the wood grew darker and more impervious. Here and there the moonbeams crept fantastically through the boughs, like fairy lamps glimmering on his path. Sometimes, preternaturally bright, the wood seemed lit up as though for some magic festival. He followed the directions he had received, pausing not until he saw the dark fir-tree rearing its broad crest and gigantic arms into the clear and twinkling heaven. It looked like the guardian genius of the place,—a huge monster lifting its terrific head, as though to watch and warn away intruders. Beside this was the rock where his adventure must terminate.

With more of desperation than courage he scrambled through the bushes. Not daring to look behind him—for he felt as though his steps were dogged, an idea for which he could not account—he made his way with difficulty by the crag until he came to a fallen tree that had apparently tumbled from the rock. Laying hold of the trunk he whistled faintly. It was answered; an echo, or something even more indistinct, gave back the sound. His heart misgave him; but he stood committed to the task, and durst not withdraw. Again he whistled, but louder than before, and again it was repeated. With feelings akin to those of the condemned wretch when he drops the fatal handkerchief, he sounded the last note of the signal. His breath was suspended. Suddenly he felt the ground give way beneath his feet, and he was precipitated into a chasm, dark, and by no means soft at the nether extremity.

This was a reception for which he was not prepared. He had sustained a severe shock; but luckily his bones were whole. Recovering from his alarm, he heard a low jabbering noise, and presently a light, which, it seems, had been extinguished by his clumsiness, was again approaching.

The intruder saw, with indescribable horror, a hideous black dwarf bearing a torch. He was dressed in the Eastern fashion. A soiled turban, torn and dilapidated, and a vest of crimson, showed symptoms of former splendour that no art could restore. This mysterious being came near, muttering some uncouth and unintelligible jargon; while the unfortunate captive, caught like a wolf in a trap, looked round in vain for some outlet whereby to escape. The only passage, except the hole through which he had tumbled, was completely filled by the broad, unwieldy lump of deformity that was coming towards him. The latter now surveyed him cautiously, and at a convenient distance, croaking, in a broken and foreign accent—

"What ho! Prisoner, by queen's grace. Better stop when little door shall open. Steps, look thee, for climb; hands and toes; go to."

Gregory now saw that steps, or rather holes, were cut in the sides of the pit wherein he had fallen, or rather been entrapped. These he ought to have used when the trap-door was let down; and he remembered his mistress's caution, to hold fast by the tree. There were, however, no means of escape that way, as the door had closed with his descent.

The ugly thing before him was ten times more misshapen than himself; and at any other time this flattering consideration would have restored him to comparative good-humour.

He was not in the mood now to receive comfort from any source. He felt sore and mightily disquieted. Limping aside, he angrily exclaimed—

"Be'st thou the de'il, or the de'il's footman, sir blackamoor? I'd have thee tell thy master to admit his guests in a more convenient fashion. Hang me, if my bones will not ache for a twelvemonth. My back is almost broke, for certain."

Here the other bellowed out into a loud laugh, pointing to Gregory's back, then surveying himself, and evidently with congratulation at his own more imaginary prepossessing appearance.

"Sir knight," said the black dwarf, "what errand comes to our mighty prince?"

"Tut! if it be his infernal kingship ye mean, I bear not messages to one of his quality."

"Thee brings writing in thy fist. Go to!"

"From a woman, fallen in love wi' thee, belike. Well, quit me o' woman's favours, say I, if this be of 'em."

"Well-a-day, sir page," cried the grinning Ethiop, whose teeth looked like a double row of pearls set in a border of carnelian, "my mistress be a queen: I do rub the dust on thy ugly nose if that red tongue wag more, for make bad speech of her. Go to, clown!"

"Ill betide thee for a blackamoor ape," said Gregory, his courage waxing apace when his fears of the supernatural began to subside; "and wherefore? Look thee, Mahound, though my mistress sent me to such a lady-bird as thou art, Master Oliver shall know on't. Thou hast won her with spells and foul necromancie; but I've commandment from him to catch all that be poaching on his lands. Thou art i' the mine, too, as I do verily guess; therefore I arrest thee i' the king's name, as a lifter of his treasure, and a spoiler of our good venison."

Gregory, being stout-limbed, and of a more than ordinary strength for his size, proceeded forthwith to execute his threat; but the dwarf, with a short shrill scream, gave him a sudden trip, which again laid the officious dispenser of justice prostrate, without either loosing the torch from his hand, or seeming to use more exertion than would have thrown a child.

"Ah, ah, there be quits. Lie still; go to; lick thy paws. Know, dog, I'm body to the queen!"

"Body o' me, I think thee be'st liker fist and crupper. I would I had thee in a cart at holiday-time, and a rope to thy muzzle," said the astonished Gregory. He had dropped his billet in the scuffle, which the dwarf seized, opening it without ceremony.

"A message. Good; stay here, garbage; I be back one, two, t'ree," and away straddled the black monster along the passage. Turning suddenly, before he was aware, into another avenue, leading apparently far into the interior, Gregory was left once more in total darkness. He heard the sound of retreating footsteps, but not a glimmer was visible, and he feared to follow lest he might be entangled in some inextricable labyrinth. He recollected to have heard a vague sort of tradition, that a subterraneous passage once led from the hall to the Ribble bank, whereby the miners had in former days kept their operations secret.

These were the haunts, too, of poachers and deer-stalkers, who made use of such hiding-places to screen their nocturnal depredations. He might be gotten unknowingly into one of their retreats, and he knew the character of such men too well to venture farther into their privy places without leave. But it was strange this ugly and insane thing should be kept here. Its outlandish accent, too, as far as Gregory could distinguish, was still more unaccountable; and that his young mistress should hold any intercourse with such a misshapen mockery of the human form was a mystery only to be resolved by a woman! After all, his first conjecture might be true, and this delicate sprite the ministering demon to some magician who brooded over the treasure.

He grew more timorous in the dark. His own breathing startled him. He revolved a thousand plans of escape; but how was it possible to climb to the pit-mouth without help, and in total darkness? The door, too, would probably defy his attempts to remove it. Suspense was not to be endured. He would have been glad to see the ugly dwarf again, rather than remain in his present evil case.

He now tried to grope out his way, from that sort of undefinable feeling which leads a person to identify change of place with improvement in condition.

Ere he had gone many yards from the spot, however, he saw a light, and presently the flaming torch was visible, with the ugly form he desired.

"Sir messenger, allez. Make scrape and go backward. Bah! What for make lady chuse ugly lout as thee for page?—not know, not inquire. Up, this way; now mind the steps. Bah, not that, fool!"

With some difficulty Gregory was initiated into the mysteries of the ascent. The torch was brandished high above his head, and with fear and trepidation he prepared to obey.

"But, master sooty-paws, my mistress will be a-wanting of some token; some reply. Hast thou no memory of her sweet favours?"

"Begone, slave-dog, begone! Say we be snug as the fox that will keep in the hole when dogs go hunt. We not go up again till lady sends leave. Go to!"

Gregory mounted with great difficulty. When he approached the mouth, looking upward for some mode of exit, he saw the trap-door slowly open, and he leapt forth into the free air; the cool atmosphere and the quiet moonlight again upon his path. He soon cleared the bushes, and once more was on his way to the house. Elizabeth met him at the gate.

"What ho, sirrah!" said she, "hast thou been loitering with my message? I left my chamber to look out for thee. What answer? Quick."

"Why, forsooth, 'tis not easy to say, methinks, for such jabber is hard to interpret. By my lady's leave, I think"—

Here he paused; but Elizabeth was impatient for the expected reply. "Softly, softly, mistress. I but thought your worship were ill bestowed on yonder ugly image."

"Tut, I'm not i' the humour for thine. What message, simpleton?"

"None, good mistress; but that they be snug until further orders."

"'Tis well; to rest; but hark thee, knave, be honest and discreet; thou shall win both gold and great honours thereby."

"What! shall I ha' my share o' the treasure?" inquired Gregory, his eyes glistening in the broad moonlight.

"What treasure, thou greedy gled?"

"Why they say 'tis a mine royal, and"—

"How! knowest thou our secret?"

"Ay, a body may quess. I've not found the road to the silver mine for nought. If I get my grip on't, the king may whistle for his share belike."

"The king! what knowest thou of the king?" said the maiden sharply.

"Eh! lady, I know not on him forsooth. Marry it would be hard to say who that be now-a-days; for the clerk towed me"—

"Peace! whom sawest thou?"

"Why the ugliest brute, saving your presence, lady, that my two een ever lippened on."

"None else?"

"No, no; I warrant ye, the miners wouldna care to let me get a glint o' the gowd. I only had a look at the hobgoblin, who they have set, I guess, to watch the treasure."

"Oh! I see,—ay, truly," said the maiden thoughtfully; "the mine is guarded, therefore be wary, and reveal not the secret, lest he crush thee. Remember," said she at parting, "remember the demon of the cave. One word, and he will grind thy bones to grist."

Gregory did remember the power of this mysterious being, who, he began to fancy, partook more of the supernatural than he had formerly imagined.

Wearied with watching, he slept soundly, but his dreams were of wizards and enchanters; heaps of gold and fairy palaces, wherein he roved through glittering halls of illimitable extent, until morning dissipated the illusion.

Some weeks passed on, during which, at times, Gregory was employed by his mistress, doubtless to propitiate this greedy monster, in conveying food secretly to the mouth of the chasm. He did not usually wait for his appearance, but ran off with all convenient speed when his errand was accomplished. Still his hankering for the treasure seemed to increase with every visit. He oft invented some plan for outwitting the demon, thereby securing to himself the product of the mine. Some of these devices would doubtless have been accomplished had not fear prevented the attempt. He had no wish to encounter again the hostility of that fearful thing in its unhallowed abode.

His mistress, however, would, at some period or another, no doubt, be in possession of all the wealth in the cave, and he should then expect a handsome share. He had heard, in old legends, marvellous accounts of ladies marrying with these accursed dwarfs for gold, and if he waited patiently he might perchance have the best of the spoil.

He brooded on this imagination so long that he became fully convinced of its truth; but still the golden egg was long in hatching.

One night he thought he would watch a while. He had just left a large barley-cake and some cheese, a bowl of furmety, and a dish of fruit.

"This monster," thought he, "devours more victuals than the worth of his ugly carcase."

He hid himself behind a tree, when presently he heard a rustling behind him. Ere he could retreat he was seized with a rude grasp, and the gruff accents of his master were heard angrily exclaiming—

"How now, sir knave?—What mischief art thou plotting this blessed night? Answer me. No equivocation. If thou dost serve me with a lie in thy mouth I'll have thee whipt until thou shall wish the life were out o' thee."

Gregory fell on his knees and swore roundly that he would tell the truth.

"Quick, hound; I have caught thee lurching here at last. I long thought thou hadst some knavery agoing. What meanest thou?"

Gregory pointed towards the provision which was lying hard by.

"Eh, sirrah! what have we hear?" said his master, curiously examining the dainties. "Why, thou cormorant, thou greedy kite, is't not enough to consume victuals and provender under my own roof, but thou must guttle 'em here too? I warrant there be other company to the work, other grinders at the mill. Now, horrible villain, thou dost smell fearfully o' the stocks!"

"O master, forgive me!—It was mistress that sent me with the stuff, as I hope the Virgin and St Gregory may be my intercessors."

"Thy mistress!—and for whom?"

"Why, there's a hole close by, as I've good cause to remember."

"Well, sirrah, and what then?"

"As ugly a devilkin lives there as ever put paw and breech upon hidden treasure. 'Tis the mine, master, that I mean."

"The mine! What knowest thou of the mine?"

"I've been there, and"—

Here he related his former adventure; at the hearing of which Oliver Tempest fell into a marvellous study.

"Hark thee," said he, after a long silence; "I pardon thee on one condition, which is, that thou take another message."

Here the terrified Gregory broke forth into unequivocal exclamations of agony and alarm.

"Peace," said his master, "and listen; thou must carry it as from my daughter. I suspect there's treason lurks i' that hole."

"Ay, doubtless," said Gregory: "for the neibours say 'tis treason to hide a mine royal."

"A mine royal! Ay, knave, I do suspect it to be so. By my troth, I 'll ferret out the foulmarts either by force or guile. And yet force would avail little. If they have the clue we might attempt to follow them in vain through its labyrinths, they would inevitably escape, and I should lose the reward. Hark thee. Stay here and I'll fetch the writing for the message. Stir not for thy life. Shouldst thou betray me I'll have thy crooked bones ground in a mill to thicken pigs' gruel."

Fearful was the dilemma; but Gregory durst not budge.

The night grew dark and stormy, the wind rose, loud gusts shaking down the dying leaves, and howling through the wide extent of the forest. The moan of the river came on like the agony of some tortured spirit. The sound seemed to creep closer to his ear; and Gregory thought some evil thing was haunting him for intruding into these unhallowed mysteries.

He was horribly alarmed at the idea of another visit to the cave, but he durst not disobey. He now heard a rustling in the bushes by the cavern's mouth. He saw, or fancied he saw, something rise therefrom and suddenly disappear. It was the demon, doubtless, retiring with his prey. He scarcely dared to breathe lest the hobgoblin should observe and seize him likewise. But his presence was unnoticed. He, however, thought that the blast grew louder, and a moan more melancholy and appalling arose from the river. Again Oliver Tempest was at his side.

"Take this, and do thy bidding." He thrust the billet into his hand, which the unfortunate recipient might not refuse.

Trembling in every limb, he approached the place of concealment; but he was too wary now to let go his hold of the fallen trunk.

He whistled thrice, and the ground again seemed to give way. A light glared from beneath, and he cautiously descended the pit.

The grim porter was waiting for him below. He fell as though rushing into the very jaws of the monster, who was but whetting his tusks ere he should devour him.

"Here again!" croaked the ugly dwarf; "what brings thy long legs back from Christendom?"

"I know not, master; but if you are i' the humour to read, I've a scrap in my pouch at your high mightiness' service."

Gregory paid more deference to him now than aforetime, having conceived a most profound respect for his attributes, both physical and mental, since his former visit.

"He is himself either some wondrous enchanter," thought he, "or, at any rate, minister or familiar to some mighty wizard, who hath his dwelling-place in this subterraneous abode."

"I have a message here to my lord," said he aloud, handing him the billet at arm's length, with a mighty show of deference and respect. The uncourteous dwarf took the writing, and left Gregory in darkness again to await his return. He shook at every joint, while the minutes seemed an age. Again the light flickered on the damp walls, and the mysterious being approached. He addressed the envoy with his usual grin of contempt.

"Tell the lady, my master be glad. He will leap from his prison by to-morrow, as she say, and appear at dinner."

"The dickons he will," said Gregory, as he clambered up the ascent, not without imminent jeopardy, so anxious was he to escape.

"This is a fearful message to master," thought he, as he leapt out joyfully into the buoyant air: "but at any rate I'll now be quit o' the job." And the messenger gave his report, for Oliver Tempest was impatiently awaiting his return.

"'Tis well," said he; "and now, hark thee, should one syllable of this night's business bubble through thy lips, thou hadst better have stayed in the paws of the hobgoblin. Away!"

Gregory needed no second invitation, but scampered home with great despatch, leaving his master to grope out the way as he thought proper.

There was more bustle and preparation for dinner than usual on the morrow. Oliver Tempest had sent messengers to Bashall and Waddow; but the guests had not made their appearance. About noon the hall-table was furnished with a few whittles and well-scoured trenchers. Bright pewter cups and ale-flagons were set in rows on a side-table, and on the kitchen hearth lay a savoury chine of pork and pease-pudding. In the great boiling pot, hung on a crook over the fire, bubbled a score of hard dumplings, and in the broth reposed a huge piece of beef—these dainties being usually served in the following order—broth, dumpling, beef, according to the old distich—

"No broth, no ba';

No ba', no meat at a'."

Dame Joan of Waddington was the presiding genius of the feast, the conduit-pipe through which flowed the full stream of daily bounty, dispensing every blessing, even the most minute. In that golden age of domestic discipline it was not beneath the dignity of a careful housewife to attend and take the lead in all culinary arrangements.

The master strode to and fro in the hall, and Elizabeth was humming at her wheel. He looked anxious and ill at ease, often casting a furtive glance towards the entrance, and occasionally a side-look at his daughter. She sometimes watched her father's eye, as though she had caught his restless apprehensions, and would have inquired the cause of his uneasiness. Suddenly a loud bay from a favourite hound that was dozing on the hearth announced the approach of a stranger. Oliver advanced with a quick step into the courtyard, and soon re-entered leading in a middle-sized, middle-aged personage, slightly formed, whose pale and saintly features looked haggard and apprehensive, while his eye wavered to and fro, less perhaps with curiosity than suspicion.

He was wrapped in a grey cloak; and a leathern jerkin, barely meeting in front, displayed a considerable breadth of under garment in the space between hose and doublet. These were fastened together with tags or points, superseding the use of wooden skewers, with which latter mode of suspension not a few of our country yeomen were in those days supplied. His legs were protected by boots of fine brown Spanish leather, lined with deer-skin, tanned with the fur on, and buttoned from the ankle to the knee. He had gloves of the same material, reaching to the elbow when drawn up, but now turned down with the fur outwards. The hands and feet were remarkably small, but well shapen. A low grey cap of coarse woollen completed the costume of this singular visitor. There was, at times, in the expression of his eye, an indescribable mixture of imbecility and enthusiasm, as though the spirit of some Eastern fakir had reanimated a living body. A gleam of almost supernatural intelligence was mingled with an expression of fatuity, that in less enlightened ages would have invested him with the dangerous reputation of priest or prophet in the eyes of the multitude.

Oliver Tempest led the way with great care and formality. To a keen-eyed observer, though, his courtesy would have appeared over acted and fulsome; but the object of his assiduities seemed to pay him little attention, further than by a vacant smile that struggled around the corners of his melancholy and placid mouth.

Dame Joan Tempest now came forth, bending thrice in a deep and formal acknowledgment. The stranger stayed her speech with a look of great benignity.

"I know thy words are what our kindness would interpret, and I thank thee. Your hospitality shall not lose its savour in my remembrance, when England hath grown weary of her guilt,—when the cry of the widow and the fatherless shall have prevailed. I am hunted like a partridge on the mountains; but, by the help of my God, I shall yet escape from the noisome pit, and from the snares of the fowler."

Yet the look which accompanied this prediction seemed incredulous of its purport. He heaved a deep sigh, and his eyes were suddenly bent on the ground. Being introduced into the hall, the seat of honour was assigned him at the table.

Elizabeth, when she saw him, uttered an ill-suppressed exclamation of surprise, and her pale countenance grew almost ghastly. Her lips were bloodless, quivering with terror and dismay. Agony was depicted on her brow—that agony which leaves the spirit without support to struggle with unknown, undefined, uncomprehended evil. Not a word escaped her; she hurried out of the hall, as she thought, without observation; but this sudden movement did not escape the eye of her father. Triumph sat on his brow; and his cheek seemed flushed with joy at the result of his stratagem.

The servitors appeared; and the smoking victuals were disposed in their due order. The joints were placed at the upper end of the board, while broth and pottage steamed out their savoury fumes from the lower end of the table. At some distance below the master and his dame sat the male domestics, then the females, who occupied the lower places at the feast, except two, who waited on the rest.

The master blessed the meal, the whole company standing. The broth was served round to the lower forms, and the meat and dainties to the higher; but Elizabeth was still absent.

When she left the hall it was for the purpose of speaking to Gregory, whom she found skulking and peeping about the premises.

"Gregory, why art thou absent from thy nooning?" inquired Elizabeth, with a suspicious and scrutinising glance.

"I'm not o'er careful to bide i' the house just now. Is there aught come that—that"—Here he stammered and looked round, confirming the suspicions of the inquirer.

"Gregory, thou art a traitor; but thou shalt not escape thy reward. I'll have thee hung—ay, villain, beyond the reach of aught but crows and kites."

"Whoy, mistress, I'd leifer be hung nor stifled to death wi' brimstone and bad humours."

"None o' thy quiddities, thou maker of long lies and quick legs. Confess, or I'll"—

"Whoy, look ye, mistress, you've been kind, and pulled me out of many an ugly ditch."

"Why dost thou hesitate, knave? I'm glad thy memory is not so treacherous as thy tongue."

"Nay, mistress, I've no notion to sup brose wi' t' old one: those that dinner wi' him he may happen ask to supper; and he'd need have a long whittle that cuts crumbs wi' the de'il."

"Art thou at thy riddles again? Speak in sober similitudes, if thou canst, sirrah."

"Your father sent me on a message to the little devilkin last night. I was loth enough to the job; but he catched me as I went wi' the victuals."

"A message!—and to what purport?"

"Nay, that I know not. The invitation was conveyed in a scrap of writing, and I'm not gifted in clerkship an' such like matters."

A ray of intelligence now burst upon her. She saw the imminent danger which threatened the fugitive, who had been hitherto concealed principally by her contrivances. Gregory watched the rapid and changing hues alternating on her cheek. She saw the full extent of the emergency; and, though her father was the traitor, she hesitated not in that trying moment.

No time was to be lost, and measures were immediately taken to countervail these designs.

"What answer sent he?" she hastily inquired.

"The de'il's buckie said his master would be at the hall by dinner-time; and I'll not be one o' the guests where old Clootie has the pick o' the table."

"Thou witless runnion, haste, or we are lost! It is the king! I would I had trusted thee before with the secret. Mayhap thy wit would have been without obscuration. Supernatural terrors have taken thy reason prisoner. Haste, nor look behind thee until thou art under the eaves of Bashall. This to my cousin, Edmund Talbot; he is honest, or my wishes themselves are turned traitors," said the maiden wistfully. She scrawled but one line, with which Gregory departed on his errand.

Oliver Tempest grew uneasy at his daughter's absence. He inquired the cause, but all were alike ignorant. The king inquired too, with some surprise; and a messenger was despatched with a close whisper in his ear.

The meal was nigh finished, when all eyes were turned towards the entrance. A little blackamoor page came waddling in. He made no sign nor obeisance, but took his station, without speaking, behind his master's chair.

"Why, how now, my trusty squire?" said the disguised monarch; "thou wast not bidden to this feast."

The dwarf cast a scowling glance at the master of the house, and he replied, while a hideous grin dilated his thick stubborn features—

"This be goodly wassail, methinks. I am weary of lurching and torchlight."

"Tempest," said the king, "I would crave grace for this follower of mine. He is somewhat fearsome and forbidding, but of an unwearied fidelity."

"Troth," said Tempest, still wishful to maintain the king's incognito, "the Turks having now taken Byzantium, the great bulwark of Christendom, I did fear me that the first of the tribe from that great army of locusts had descended upon us."

"Fear not," said the unfortunate monarch, with a smile; "this poor innocent will do no ill. His mistress brought him for me a present from her father's court; and, to say the truth, he has been a great solace in my trouble. He hath not forsaken me when they who fattened on my bounty—who dipped their hands with me in the dish—have been the first to betray me. The knave is shrewd and playful, but of an incredible strength, being, as ye may observe, double-jointed. Madoc, let them behold some token of thy power."

The cunning rogue obeyed in a twinkling. He seized the host's chair with one hand, lifting its occupant without difficulty from the ground. With the other he laid hold on him by the throat, and would certainly have strangled him but for the king.

The assault was so sudden and unexpected that the domestics stood still a moment, as though rendered powerless by surprise.

The next instant they all fled pell-mell out of the hall, every one struggling to be foremost, apprehending that the great personification of all evil was there, bodily, behind them, and in the very act of flying off with their master.

In vain Joan shouted after the cowardly villains; her threats but increased their speed.

"Fly, King Henry," cried the dwarf, in a voice that sounded like the roar of some infuriated beast; "the rascal curs are barking; the stag is in the net. This traitor"—Here he became at a loss for words; but his gesticulations were more vehement. "Fly!" at length he shouted, in a louder voice than before; "I've seen sword and armour glittering in the forest."

But the king was irresolute, as much amazed as any of the rest. He saw the imminent danger of his host, whose face was blackening above the grip of this fierce antagonist, and he cried out—

"Leave go, Madoc; let the curs bark, we fear them not in this good house. Let go, I command thee."

With a look of pity and of scorn the savage loosened his hold, saying—

"Thou be'st not king now; but Henry with the beads and breviary; and here come thy tormentors."

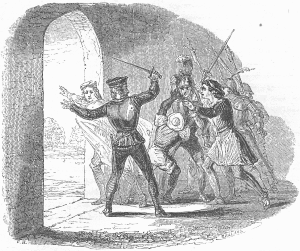

A loud whistle rang through the hall, and in burst a band of armed men, led on by Sir Thomas Talbot of Bashall, and his oldest son of the same name, together with Sir James Harrington.

Tempest, recovered from his gripe, made a furious dart at the king; but ere he had accomplished his purpose, Edmund Talbot rushed between, at the peril of his life, opening a way for the terrified monarch through the band that had nearly surrounded him.

The king fled through the passage made by his deliverer; and the dwarf, keeping his enemies at bay, heroically and effectually covered his retreat.

"Edmund Talbot, art thou traitor to thy kin?" said Sir Thomas, from the crowd. "Let me pass; 'tis thy father commands thee. 'Tis not thy king, he is a coward and a usurper."

"I care not," said the retreating and faithful Edmund. "My arm shall not compass with traitors. Cowards attack unarmed men at their meals."

"Then take thy reward." It was the eldest brother of Edmund who said this, whilst he aimed a terrific blow; but the dwarf caught his arm ere it descended, and a swinging stroke from a missile which he had picked up in the fray would have settled accounts between the heir of Bashall and posterity had he not stepped aside.

This unequal contest, however, could not long continue, though time, the principal object, was gained, and the king was fast hastening again towards the cavern. In the courtyard he met Elizabeth, who implored him to step aside into another place of concealment; but he was too much terrified to comprehend her meaning. Fear seemed to have bewildered him, and the poor persecuted monarch sped on to his own destruction. In the hurry and uncertainty of his flight, he unfortunately took the wrong path, which led by a circuitous route to the ford; and, as he stepped out of the wood, two of his enemies, having broken through the gallant defence of his adherents, had already gained, and were guarding, the stepping-stones over the river, called "Brunckerley Hippens." Terrified, he flew back into the wood, but was immediately followed; and again his evil destiny seemed to prevail. He took another path, which led him back to the ford. Here he crossed, and, whilst leaping with difficulty over the stones, the pursuers came in full view. Having gained the Lancashire side, he fled into the wood, but his enemies were now too close upon him for escape, and the royal captive was taken, bound, and conveyed to Bashall. Many cruel indignities were heaped upon him; and he was conveyed to London in the most piteous plight, on horseback, with his legs tied to the stirrups. Ere he departed, it is said that he delivered a singular prediction—to wit, that nine generations of the Talbot family, in succession, should consist of a wise and a weak man by turns, after which the name should be lost.

FOOTNOTES:

[54] Whitaker's Craven.

[55] Pennant.

[56] Hist. Whalley.

[57] Webster, in his Metallographia, mentions a field called Skilhorn, in the township of Rivington-within-Craven, "belonging to one Mr Pudsay, an ancient esquire, and owner of Bolton Hall, juxta Bolland; who, in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, did get good store of silver-ore, and convert it to his own use, or rather coined it, as many do believe, there being many shillings marked with an escallop, which the people of that country call Pudsay shillings to this day. But whether way soever it was, he procured his pardon for it, and had it, as I am certified from the mouths of those who had seen it." Webster further adds: "While old Basby (a chemist) was with me, I procured some of the ore, which yielded after the rate of twenty-six pounds of silver per ton. Since then, good store of lead has been gotten; but I never could procure any more of the sort formerly gotten; the miners being so cunning, that if they meet with any vein that contains so much ore as will make it a myne royall, they will not discover it."

Dr Whitaker, in his History of Craven, says: "The following papers, lately communicated to me from the evidences of the Pudsays, put the matter out of doubt:—'Case of a myne royall. Although the gold or silver contained in the base metalls of a mine in the land of a subject be of less value than the baser metall, yet if gold and silver doe countervaile the charge of refining, or bee of more value than the baser metall spent in refining itt, this is a myne royall, and as wel the base metall as the gold and silver in it, belongs to the crown.

"'Edw. Herbert, Attorney-General.

Oliver St John, Solicitor-General.

Orl. Bridgman.

Joh. Glanvill.

Jeoffry Palmer.

Tho. Lane.

Jo. Maynard.

Hdw. Hyde.

J. Glynn.

Harbottle Grimstone,' &c.

"So favourable at that time were the opinions of the most constitutional lawyers (for such were the greater part of these illustrious names) to the prerogative. But the law on this head has been very wisely altered by two statutes of William and Mary.—Blackstone, iv. 295.

"The other paper is of later date:—'To the King's most excellent Majestie. The humble petition of Ambrose Pudsay, Esq., sheweth, that your petitioner having suffered much by imprisonment, plunder, &c., for his bounden loyalty, and having many years concealed a myne royall, in Craven, in Yorkshire, prayeth a patent for digging and refining the same.'"

[58] Hist, of Whalley, p. 504.

[59] This lady, whose attractions or good fortune must have been uncommon, says the historian of Craven, was daughter to Henry Pudsay of Bolton. She married, first, Sir Thomas Talbot of Bashall, who died 13 Henry VII.; after which she became the second wife of Henry, Lord Clifford, the shepherd; and, after his decease, by the procurement of Henry VIII., gave her hand to Richard Grey, youngest son of Thomas, Marquis of Dorset.