Traditions of Lancashire by John Roby

THE BAR-GAIST.

"From hag-bred Merlin's time have I

Thus nightly revelled to and fro;

And for my pranks men call me by

The name of Robin Goodfellow.

Fiends, ghosts, and sprites,

Who haunt the nightes,

The hags and goblins do me know;

And beldames old

My feates have told—

So vale, vale; ho, ho, ho!"

—BEN JONSON.

"In the northern parts of England," says Brand, speaking of

the popular superstitions, "ghost is pronounced gheist and

guest. Hence barguest or bargheist. Many

streets are haunted by a guest, who assumes many strange

appearances, as a mastiff dog, &c. It is a corruption of the

Anglo-Saxon ![]() , spiritus, anima."

, spiritus, anima."

Drake, in his Eboracum, says (p. 7, Appendix), "I have

been so frightened with stories of the barguest when I was a

child, that I cannot help throwing away an etymology upon it. I

suppose it comes from A.S. ![]() , a town, and

, a town, and ![]() , a ghost, and so signifies a

town sprite. N.B.

, a ghost, and so signifies a

town sprite. N.B. ![]() is in the Belgic and Teutonic softened into gheist

and geyst."

is in the Belgic and Teutonic softened into gheist

and geyst."

The boggart or bar-gaist of the following story resembles the German kobold, the Danish nis, and the Scotch brownie; but, above all, the Spanish duende, which signifies a spirit or sprite, supposed by the vulgar to haunt houses and highways, causing therein much terror and confusion. "DUENDE. Espiritu que el vulgo cree que infesta las casas y travesea, causando en ellas ruidos y estruendos"—LEMURES, LARVÆ. "To appear like a duende," "to move like a duende" are modes of speaking by which it is meant that persons appear in places where they are least expected. "To have a duende" signifies that a person's imagination is disturbed.

The following curious Spanish "Moral," the MS. of which has been kindly lent to the author by Mr Crofton Croker may not be deemed uninteresting as an illustration of the subject. We have accompanied each stanza with a parallel translation of our own.

DUENDE ENEMIGO DEL JUEGO.

DUENDE AN ENEMY TO GAMING.

Cuento Morál.

A Moral Tale.

Un Duende, grave Señor,

Que estudió la astrologia,

Se propuso la mania,

De ser rico jugador.

A grave and learned Senior, who

Practised astrology,

Bethought him by his lucky stars

He passing rich would be.

Todos los siete planetas,

Formaban su gran consejo;

Y antes de llegar á viejo,

Ya no tenia calzetas.

The planets seven his council made,

He hugged the glozing cheat;

But ere the pedant's legs were old,

No stockings held his feet!

Aburrido y sin dinero,

Mui tarde se arrepintid,

Y en un desban se metid

A llorar su error primero.

Enraged and disappointed, he

Waxed sour and melancholy,

And to a vintner's garret trudged,

There to bewail his folly.

Por su gran sabiduría,

En duende se corivirtió,

Y la guerra declaró,

Al arte de fullería.

"I'll have revenge," he cried, then wrought

So wondrous cunningly,

That in a trice transformed he was,

A brisk Duende he.

La vecíndad asombrada,

De sus fuertes alaridos,

Corriendo despavoridos,

Abandon an la Posada.

This pedant, now a "Boggart" made,

No soul could rest in quiet;

Nor rogue nor bully was his match

For kicking up a riot.

Dueño absolute ya el duende,

De la espantosa mansion,

Se aunientó la confusion,

Y el temor entre la gente.

At last none dared that garret drear,

His dwelling, to come nigh;

Sole master of his attic, he

Reigned peremptorily.

Pero siendo tan demente

El hombre que es codicioso,

No faltó quien jactancioso,

Despreciase al señor duende.

Not so the sharpers, who this house

Had made their special haunt:

"Señor Duende!—Humph!"—cried they

"May suck eggs with his aunt!"

Unos cuantos jugadores,

Que llaman de profesion,

Eligieron la mansion

Para exercer sus primores.

They and their worthy company,

Of the black-limbed profession,

Here cheated in a lawful way,

By that best right—possession!

Mui luego la compañia,

Numerosa vino á ser,

Y el que Ilegaba á perder,

Contra al duende maldecía.

The crowd increased. Some luckless wight

His winnings at an end, he

Swore by his trumps, 'twas owing to

That rascally Duende!

La confusa gritería,

Pronto al duende incomodó,

Y al complot se apareció

Que ápenas, cuarta tenía.

This roused him from his garret, where

He heard the daily squabble;

And lo, in human form, he stands

Before the shirtless rabble!

En voz, como chirimía,

Dijoles cortés y atento

Que habitaba el aposento

Donde su amo existia.

He squeaked, "Your servant, gentlemen;

I would not thus intrude,

'Pon honour, but your conduct is

So very-very rude.

Que en alta camara fiero,

Todo señor, reclamaba

El orden, y lo aperaba,

Aunque ageno de en fullero.

"My master,—he who sits up-stairs

I mean,—no jesting, gents,—

Expects that you'll be quiet, else

He'll scold at all events."

No fue poca la sorpresa,

Del mensage y la vision;

Y aun con todo, un temerón,

Quiso de ella hacer presa.

The gamblers stared, some tumbled down,

Some gaped, some told their prayers

But one, more daring, swore, i'fack,

He'd kick the brute down-stairs!

Mas el caso se fustró,

Sin saber como ni cuando,

Pues por el ayre volando

Nuestro duende se fugó.

But ere he felt th' uplifted foot

He 'scaped,—how none could tell;

But, sooth it was, this messenger

No bodily harm befell!

El suceso maldecían

Los unos por el temor,

Y gritaban con furor

Los que el dinero perdían.

The rogues, who saw him disappear,

Waxed paler than before:

Some said an Ave; some for fear,

And some for folly, swore.

Vuelve por segunda vez,

El mensajero, crecido

Media vara, y atrevido,

Les dice, menos cortés.

When suddenly amidst them all,

Again the demon stands;

A full half-yard in stature grown!

Their business he demands.

Que su amo, era absoluto,

De aquella encantada casa,

Y su paciencia era escasa,

Con todo fullero astuto.

"I tell ye, villains, gamblers, thieves!

His patience is but small,

With such as you,—so master says,

Who master will you all!

Que les mandaba salir

De aquel lugar, con presteza,

Pues de no, su gentileza,

Los haría consumir.

"Out of the house, ye rabble rout!

Out of the house! I say,

Or otherwise his honour will

Consume you utterly!"

Del duendecito quisieron

Apoderarse valientes,

Mas se les fué entre los dientes,

Y sin la presa se vieron.

Thought one, "I'll seize this varlet vile,"

And speedily arose;

He caught him in his clutch—the sprite

Vanished and tweaked his nose!

Ya el temor empezó á obrar

Y entraron las reflexiones,

Apoyando con varones,

Que era Duende, á no dudar.

"San Jerome, save us, we are loo'd

If this should be the sprite;

The big Duende, best we bid

His boggartship good night."

Como siempre al jugador,

Lo sostiene la esperanza,

Fundàron la confianza,

En que un Duende es vividor.

But hope, the gambler's enemy,

Beguiled them to their ruin;

"These ugly sprites, they say, are rich,

Yet yield nought without wooing.

Que su ciencia atrae dinero,

Y medios paro adquirirlo,

Y era cuerdo el admitirlo,

Dandole el lugar primero.

"His skill may help us to repair

Our cloaks, and eke our breeches;

Best speak him fair. We'll worship Nick

If he but grant us riches!"

Mas el duende que escuchaba

La trama de los fulleros,

Quiso en tales caballeros,

Vengàr, lo que suspiraba.

The sly Duende, like a mouse,

Hearkening behind the wall,

Did now resolve he quickly would

The greedy rogues bemaul

En efecto, agigantado,

Con negro manto talár,

Cornamenta singular,

Ufías largas y barbado.

A mighty giant, lo he comes.

Wrapped in a cloak of sable;

With horns, hoofs, nails, and beard yclad,

He jumped upon the table!

Un garrote enarbolado

Y brotando espuma y fuego,

Les dijo: Yo devo al juego

Mi desgracia y este estado.

A cudgel of some seven years' growth

He brandished. Fire and smoke

Shot from his lips, while thus he spake;—

"I'll gripe you gambling folk.

Los fulleros me han quitado

Con mi dinero, la vida,

Y pues que sois homicida

De todo hombre inocente!

"To gaming my disgrace I owe,

With money went my wife;

'Tis such as you the murderers be,—

This night shall end your life!

No quede vicho viviente,

En toda culta nacion,

Que ejérza la profesion

De fullero y vagamundo.

"In every nation, called refined,

Or gamblers or their wives,

Or wealthy wight shall ne'er be found,

Who shakes the bones and thrives."

Y dando un grito profundo,

Su garrote descargando,

A todos fué despachando,

Sin dejar uno en el mundo.

With that a loud and horrid yell

He gave. And cudgel flew

Broadside amongst them; when, like vermin, he

Dispatched the hungry crew!

No extinguió, sin duda, el Duende,

Toda la mala semilla,

Pues hay muchos, como el Duende,

Sin camisa, y sin capilla.

But woe is me, they were not all destroyed.

For many still, by these cursed arts decoyed,

Shoeless and shirtless, miserable sinners,

Are seen, snuffing, with empty wind, their dinners!

In the Dunske Folkesagen appear one or two circumstances relative to the freaks of a nis, the goblin of the Danish popular creed, similar to the pranks detailed in our Lancashire legend. Fancy, however sportive and playful with materials already in her possession, is of a much less creative character than is generally supposed, even by those most susceptible to her influence. It is surprising how few are the original conceptions that have sprung from the human mind. Popular superstitions—the great mass of them spread over an immense variety of surface, climate, manners, and opinions—might be supposed to exhibit a corresponding difference in originality and invention. But here we find the same paucity of incidents, varying only in character with the climate which gave them birth; the leading features being evidently common to each. The Scandinavian and the Hindoo, the European and the Asiatic, construct their legends on the same basis; the same stories, and even the same train of events, proving their common origin.

Mr Crofton Croker, a name familiar to all lovers of legendary lore, has kindly communicated the following tale. In substituting this, in place of what the author might have written on the subject, he feels convinced that his readers will not feel displeased at the change, and assures them it is with real gratification that he presents them with an article from the pen of the writer of The Fairy Legends.

Not far from the little-snug smoky village of Blakeley, or Blackley, there lies one of the most romantic of dells, rejoicing in a state of singular seclusion, and in the oddest of Lancashire names, to wit, the "Boggart-hole." Rich in every requisite for picturesque beauty and poetical association, it is impossible for me (who am neither a painter nor a poet) to describe this dell as it should be described; and I will therefore only beg of thee, gentle reader, who peradventure mayst not have lingered in this classical neighbourhood, to fancy a deep, deep dell, its steep sides fringed down with hazel and beech, and fern and thick undergrowth, and clothed at the bottom with the richest and greenest sward in the world. You descend, clinging to the trees, and scrambling as best you may,—and now you stand on haunted ground! Tread softly, for this is the Boggart's clough; and see in yonder dark corner, and beneath the projecting mossy stone, where that dusky sullen cave yawns before us, like a bit of Salvator's best, there lurks the strange elf, the sly and mischievous Boggart. Bounce! I see him coming; oh no, it was only a hare bounding from her form; there it goes—there!

I will tell you of some of the pranks of this very Boggart, and how he teased and tormented a good farmer's family in a house hard by, and I assure you it was a very worthy old lady who told me the story. But first, suppose we leave the Boggart's demesne, and pay a visit to the theatre of his strange doings.

You see that old farm house about two fields distant, shaded by the sycamore-tree: that was the spot which the Boggart or Bar-gaist selected for his freaks; there he held his revels, perplexing honest George Cheetham—for that was the farmer's name—scaring his maids, worrying his men, and frightening the poor children out of their seven senses, so that at last not even a mouse durst show himself indoors at the farm, as he valued his whiskers, five minutes after the clock had struck twelve.

It had long been remarked that whenever a merry tale was told on a winter's evening a small shrill voice was heard above all the rest, like a baby's penny trumpet, joining in with the laughter.

"Weel laughed, Boggart, thou'rt a fine little tyke, I'se warrant, if one could but just catch glent on thee," said Robert, the youngest of the farmer's sons, early one evening, a little before Christmas, for familiarity had made them somewhat bold with their invisible guest. Now, though more pleasant stories were told on that night beside the hearth than had been told there for the three preceding months, though the fire flickered brightly, though all the faces around it were full of mirth and happiness, and though everything, it might seem, was there which could make even a Boggart enjoy himself, yet the small shrill laugh was heard no more that night after little Bob's remark.

Robert, who was a short stout fellow for his age, slept in the same bed with his elder brother John, who was reckoned an uncommonly fine and tall lad for his years. No sooner had they got fairly to sleep than they were roused by the small shrill voice in their room shouting out, "Little tyke, indeed! little tyke thysel'. Ho, ho, ho! I'll have my laugh now—Ho, ho, ho!"

The room was completely dark, and all in and about the house was so still that the sound scared them fearfully. The concluding screech made the place echo again;—but this strange laughter was not necessary to prevent little Robert from further sleep, as he found himself one moment seized by the feet and pulled to the bottom of the bed, and the next moment dragged up again on his pillow. This was no sooner done, than by the same invisible power he was pulled down again, and then his head would be dragged back, and placed as high as his brother's.

"Short and long won't match,—short and long won't match,—ho, ho, ho!" shouted the well-known voice of the Boggart, between each adjustment of little Robert with his tall brother, and thus were they both wearied for more than a hundred times; yet so great was their terror, that neither Robert nor his brother—"Long John," as he ever afterwards was called—dared to stir one inch; and you may well suppose how delighted they both were when the first grey light of the morning appeared.

"We'st now ha' some rest, happen," said John, turning on his side in the expectation of a good nap, and covering himself up with the bed-clothes, which the pulling of Robert so often backwards and forwards had tumbled about sadly.

"Rest!" said the same voice that had plagued them through the night, "rest!—what is rest? Boggart knows no rest."

"Plague tak' thee for a Boggart!" said the farmer next morning, on hearing the strange story from his children: "Plague tak' thee! can thee not let the poor things be quiet? But I'll be up with thee, my gentleman: so tak' th' chamber an' be hang'd to thee, if thou wilt. Jack and little Robert shall sleep o'er the cart-house, and Boggart may rest or wriggle as he likes when he is by himsel'."

The move was accordingly made, and the bed of the brothers transferred to their new sleeping-room over the cart-house, where they remained for some time undisturbed; but his Boggartship having now fairly become the possessor of a room at the farm, it would appear, considered himself in the light of a privileged inmate, and not, as hitherto, an occasional visitor, who merely joined in the general expression of merriment. Familiarity, they say, breeds contempt; and now the children's bread and butter would be snatched away, or their porringers of bread and milk-would be dashed to the ground by an unseen hand; or if the younger ones were left alone but for a few minutes, they were sure to be found screaming with terror on the return of their nurse. Sometimes, however, he would behave himself kindly. The cream was then churned, and the pans and kettles scoured without hands. There was one circumstance which was remarkable;—the stairs ascended from the kitchen, a partition of boards covered the ends of the steps, and formed a closet beneath the staircase. From one of the boards of this partition a large round knot was accidentally displaced; and one day the youngest of the children, while playing with the shoe-horn, stuck it into this knot-hole. Whether or not the aperture had been formed by the Boggart as a peep-hole to watch the motions of the family, I cannot pretend to say. Some thought it was, for it was called the Boggart's peep-hole; but others said that they had remembered it long before the shrill laugh of the Boggart was heard in the house. However this may have been, it is certain that the horn was ejected with surprising precision at the head of whoever put it there; and either in mirth or in anger the horn was darted forth with great velocity, and struck the poor child over the ear.

There are few matters upon which parents feel more acutely than that of the maltreatment of their offspring; but time, that great soother of all things, at length familiarised this dangerous occurrence to every one at the farm, and that which at the first was regarded with the utmost terror, became a kind of amusement with the more thoughtless and daring of the family. Often was the horn slipped slyly into the hole, and in return it never failed to be flung at the head of some one, but most commonly at the person who placed it there. They were used to call this pastime, in the provincial dialect, "laking wi' t' Boggart;" that is, playing with the Boggart. An old tailor, whom I but faintly remember, used to say that the horn was often "pitched" at his head, and at the head of his apprentice, whilst seated here on the kitchen table, when they went their rounds to work, as is customary with country tailors. At length the goblin, not contented with flinging the horn, returned to his night persecutions. Heavy steps, as of a person in wooden clogs, were at first heard clattering down-stairs in the dead hour of darkness; then the pewter and earthern dishes appeared to be dashed on the kitchen-floor; though in the morning all remained uninjured on their respective shelves. The children generally were marked out as objects of dislike by their unearthly tormentor. The curtains of their beds would be violently pulled to and fro,—then a heavy weight, as of a human being, would press them nearly to suffocation, from which it was impossible to escape. The night, instead of being the time for repose, was disturbed with screams and dreadful noises, and thus was the whole house alarmed night after night. Things could not long continue in this fashion; the farmer and his good dame resolved to leave a place where they could no longer expect rest or comfort: and George Cheetham was actually following with his wife and family the last load of furniture, when they were met by a neighbouring farmer, named John Marshall.

"Well, Georgey, and soa you're leaving th' owd house at last?" said Marshall.

"Heigh, Johnny, ma lad, I'm in a manner forced to 't, thou sees," replied the other; "for that wearyfu' Boggart torments us soa, we can neither rest neet nor day for't. It seems loike to have a malice again't young ans,—an' it ommost kills my poor dame here at thoughts on't, and soa thou sees we're forc'd to flitt like."

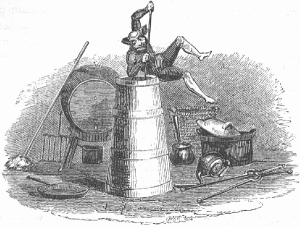

He had got thus far in his complaint, when, behold, a shrill voice from a deep upright churn, the topmost utensil on the cart, called out—"Ay, ay, neighbour, we're flitting, you see."

"'Od rot thee!" exclaimed George: "if I'd known thou'd been flitting too I wadn't ha' stirred a peg. Nay, nay,—it's to no use, Mally," he continued, turning to his wife, "we may as weel turn back again to th' owd house as be tormented in another not so convenient."

They did return; but the Boggart, having from the occurrence ascertained the insecurity of his tenure, became less outrageous, and was never more guilty of disturbing, in any extraordinary degree, the quiet of the family.

Index | Next: The Haunted Manor-House