Traditions of Lancashire by John Roby

THE LANCASHIRE WITCHES.

"More swift than lightning can I flye

About this aery welkin soone;

And, in a minute's space, descrye

Each thing that's done below the moone."

—BEN JONSON.

"When I consider whether there are such persons as witches, my mind is divided: I believe, in general, that there is such a thing as witchcraft, but can give no credit to any particular instance of it."—ADDISON.

The term witchcraft, says the historian of Whalley, is now "transferred to a gentler species of fascination, which my fair countrywomen still continue to exert in full force, without any apprehension of the county magistrates, or even of the king in council."

Far different was the application in days of old. The common parish witch is thus described by a contemporary writer, as an old woman "with a wrinkled face, a furred brow, a hairy lip, a gobber tooth, a squint eye, a squeaking voice, or a scolding tongue; having a rugged coat on her back, a skull-cap on her head, a spindle in her hand, and a dog or cat by her side." Such was the witch of real life when this superstition was so prevalent in our own neighbourhood, and even throughout England. From the beginning of the reign of James the First to the concluding part of the reign of James the Second, it may be considered as having attained the zenith of its popularity. "Witchcraft and kingcraft both came in with the Stuarts and went out with them." It was as if his infernal majesty had taken a lesson from his sacred majesty, and issued a book of sports for his loyal subjects. "The Revolution put to rights the faith of the country as well as its constitution." "The laws were more liberally interpreted and rationally administered.

The trade of witch-finding ceased to be reputable or profitable;" and that silly compilation, the "Demonology" of James, which, with the severe laws enacted against witchcraft by Henry the Eighth and Elizabeth, had conjured up more witches and familiars than they could quell, was consigned to the book-worm and the dust. It is said in the Arabian tales, that Solomon sent out of his kingdom all the demons that he could lay his hands on, packed them up in a brazen vessel, and cast them into the sea. But James, "our English Solomon," "imported by his book all that were flying about Europe, to plague the country, which was sufficiently plagued already in such a sovereign." This sapient ruler, who, it is said, "taught divinity like a king, and made laws like a priest," in the first year of his reign made it felony to suckle imps, &c. This statute, which was repealed March 24th, 1736, describes offences declared felonious, thus:—

"One that shall use, practise, or exercise any invocation or conjuration of any evil or wicked spirit, or consult, covenant with, entertain or employ, feed or reward, any evil or wicked spirit, to or for any intent or purpose; or take up any dead man, woman, or child, out of his, her, or their grave, or any other place where the dead body resteth; or the skin, bone, or other part of any dead person, to be employed or used in any manner of witchcraft, sorcery, charm, or enchantment; or shall practise or exercise any witchcraft, &c., whereby any person shall be killed, destroyed, wasted, consumed, pined, or lamed in his or her body, or any part thereof: such offenders, duly and lawfully convicted and attainted, shall suffer death."

As might be expected, witchcraft so increased in consequence of these denunciations, that, "in the course of fifty years following the passing of this act, besides a great number of single indictments and executions, fifteen were brought to trial at Lancaster in 1612, and twelve condemned; in 1622, six were tried at York; 1634, seventeen condemned at Lancaster; 1644, sixteen were executed at Yarmouth; 1645, fifteen condemned at Chelmsford, and hanged; in the same and following year, about forty at Bury in Suffolk; twenty more in the county, and many in Huntingdon; and (according to the estimate of Ady) some thousands were burned in Scotland."

Popular hatred rendered the existence of a reputed witch so miserable, that persons bearing that stigma often courted death in despair, confessing to crimes which they had never committed, for the purpose of ridding themselves of persecution.

"One of the latest convictions was that of Amy Duny and Rose Cullender, before Sir Matthew Hale at Bury, in 1664. They were executed, and died maintaining their innocence." Their execution was a foul blot upon his name, as it is scarcely to be doubted but that they were the victims of imposture. It was clearly ascertained by experiments in the judge's presence, that the children who pretended to be bewitched, when their eyes were covered, played off their fits and contortions at the touch of some other person, mistaking it for that of the accused, yet "he charged the jury without summing up the evidence, dwelling only upon the certainty of the fact that there were witches, for which he appealed to the Scriptures, and, as he said, to 'the wisdom of all nations;' and the jury having convicted, the next morning left them for execution."

But we proceed with a few explanatory notices respecting that portion of the history of this superstition, which will be found interwoven with the traditionary matter in our text.

A number of persons, inhabitants of Pendle Forest, were apprehended in the year 1633, upon the evidence of Edmund Robinson, a boy about eleven years old, who deposed before two of his Majesty's justices at Padiham, that on All-Saints'-day he was getting "bulloes," when he saw two greyhounds—a black one and a brown one—come running over the field towards him. When they came nigh they fawned on him, and he supposed they belonged to some of the neighbours. He expected presently that some one would follow; but seeing no one, he took them by a string which they had tied to their collars, and thought he would hunt with them. Presently a hare sprang up near to him, and he cried "Loo, loo," but the dogs would not run. Whereupon he grew angry, and tied them to a bush for the purpose of chastising them, but instead of the black greyhound he now beheld a woman, the wife of one Dickisson, a neighbour; the other was transformed into a little boy.

At this sight he was much afraid, and would have fled; but the woman stayed him and offered him a piece of silver like a shilling if he would hold his peace. But he refused the bribe; whereupon she pulled out a bridle and threw it over the little boy's head, who was her familiar, and immediately he became a white horse. The witch then took the deponent before her, and away they galloped to a place called Malkin Tower, by the Hoarstones at Pendle. He there beheld many persons appear in like fashion; and a great feast was prepared, which he saw, and was invited to partake, but he refused. Spying an opportunity, he stole away, and ran towards home. But some of the company pursued him until he came to a narrow place called "the Boggard-hole," where he met two horsemen; seeing which, his tormentors left off following him. He further said, that on a certain day he saw a neighbour's wife, of the name of Loynd, sitting upon a cross piece of wood within the chimney of his father's dwelling-house. He called to her, saying, "Come down, thou Loynd wife," and immediately she went up out of sight. Likewise upon the evening of All-Saints before-named, his father sent him to seal up the kine, when, coming through a certain field, he met a boy who began to quarrel with him, and they fought until his face and ears were bloody. Looking down, he saw the boy had cloven feet, and away he ran.

It was now nearly dark; but he descried at a distance a light like a lantern. Thinking this was carried by some of his friends, he made all haste towards it, and saw a woman standing on a bridge, whom he knew to be Loynd's wife; turning from her he again met with the boy, who gave him a heavy blow on the back, after which he escaped. On being asked the names of the women he saw at the feast, he mentioned seventeen persons, all of whom were committed to Lancaster for trial. They were found guilty, and sentenced to be executed. The judge, however, respited them, and reported the case to the king in council.

The celebrated John Webster, author of The Discovery of Pretended Witchcraft, afterwards took this young witch-finder in hand. He says:—

"This said boy was brought into the church at Kildwick (in Craven), a large parish church, where I, being curate there, was preaching in the afternoon, and was set upon a stall to look about him, which moved some little disturbance in the congregation for a while. After prayers, I, inquiring what the matter was, the people told me it was the boy that discovered witches; upon which I went to the house where he was to stay all night, where I found him, and two very unlikely persons that did conduct him, and manage the business.

"I desired to have some discourse with the boy in private; but that they utterly refused. Then, in the presence of a great many people, I took the boy near me, and said, 'Good boy, tell me truly and in earnest, didst thou see and hear such strange things of the meeting of witches as is reported by many that thou didst relate?'—But the two men, not giving the boy leave to answer, did pluck him from me, and said he had been examined by two able justices of the peace, and they did never ask him such a question. To whom I replied, the persons accused had the more wrong. As the laws of England, and the opinions of mankind then stood, a mad dog in the midst of a congregation would not have been more dangerous than this wicked and mischievous boy, who, looking around him, could, according to his own caprice, put any one or more of the people in peril of tortures or of death."

Four of the accused only were sent to London, and examined by the king in person. In the end they were set at liberty, but not from the sagacity of the examiners,—the boy Robinson having confessed that he was suborned to give false evidence against them. One of these poor creatures, strange to say, had confessed the crime with which she was charged. In the Bodl. Lib. Dods. MSS. v.61, p.47, is the confession itself, wherein she gives a circumstantial and minute account of the transactions which took place between her and a familiar whom she calls Mamilian, describing the meetings, feasts, and all the usual routine of witchery and possession.—(See Whitaker's Whalley.)

PART FIRST.

The mill went merrily round, and Giles the miller sang and whistled from morning to noon, and from noon till evening, save when the mulcting-dish was about to be embowelled in the best sack; a business too serious for such levity, requiring careful and deliberate thought.

Goody Dickisson, the miller's wife, was a fat, round, pursy dame, of some forty years' travel through this wilderness of sorrow, and a decent, honest, sober, and well-conditioned housewife she was; cleanly, thrifty, and had an excellent cheesepress, which the whole neighbourhood could testify.

But the days of man's happiness are numbered, and woman's too, as the following narrative will set forth.

The mill had stood, for ages it may be, at the foot of a wild and steep cliff, forming the eastern extremity of the dreary range of Cliviger;[37] an elevated mountainous pass, from whence the waters descend both to the eastern and western seas. Upon those almost inaccessible crags the rock-eagle and falcon built their nests, unscared by the herdsmen, who in vain attempted their destruction. Through this pass, the very gorge of the English Apennines, the Calder,[38] a rapid and narrow torrent, brought an unfailing supply of grist to the ever-going hopper of Giles Dickisson.

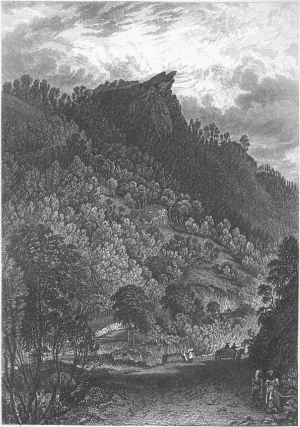

Not far from this happy abode, in the innermost part of the gorge, where the rocks of Lancashire and Yorkshire frown in close but harmless proximity, at an immense height,—the road and this narrow cleft only separating their barriers,—rises a crag of a singular shape, jutting far out from the almost perpendicular strata beneath. Its form is precisely that of a gigantic helmet, hammered out by the fanciful artist into the likeness of an eagle, its wings partly outstretched, and its beak—the point of the crag—overshadowing the grim head of some gaunt warrior. With but little aid from the imagination, the whole features may be discerned; hence it was denominated, "The Eagle Crag." But another appellation, more awful and mysterious, might be attached to it—a reminiscence of those "deeds without a name," which have rendered this district of Lancashire so fearfully notorious—"The witches' horse-block."

The narrow pass we have described opens out into a succession of picturesque valleys, abounding in waterfalls of considerable depth and beauty, and expanding towards the north in tracts of fertile pasture-ground to the base of Pendle, well known as the reputed scene of those mysteries in which "the witches of Pendle" acted so conspicuous a part.

Towards the close of the sixteenth and the beginning of the seventeenth century, the fame, or rather the infamy, of witchcraft, infested this once peaceful and sequestered district. The crag we have just noticed was, no doubt, to the apprehensions of the simple-hearted peasant, oft visited by the unhallowed feet of weirds and witches pluming themselves for flight to the great rendezvous at Malkin Tower, by the side of "the mighty Pendle."

EAGLE CRAG, VALE OF TODMORDEN.

Drawn by G. Pickering. Engraved by Edwd

Finden.

Little did our country deserve, in those days, the name of "Merry England." Plague or the most noisome pestilence would have been a visitation of mercy compared to the miseries caused by so dark a superstition. "Even he who lived remote from the scene of this spiritual warfare, though few such there could be, so rapidly was it transferred from county to county to the remotest districts;—he, in whose vicinity no one was suspected of dealing with the foul fiend, whose children, cattle, or neighbours, showed no symptoms of being marks for those fiery darts which often struck from a distance, yet would he not escape a sort of epidemic gloom, a vague apprehension of the mischief which might be. The atmosphere he breathed would come to him thick with foul fancies; he would ever be hearing or telling some wild and melancholy tale of crime and punishment. His best feelings and enjoyments would be dashed with bitterness, suspicion, and terror, as he reflected that, though uninvaded, yet these were at the mercy of malignant fellow-mortals, leagued with more malignant spirits, the laws and limits of whose operations were wholly undefinable.

"What must have been his feelings on whom the evil eye had glared,—against whom the spell had been pronounced; on whom misfortunes came thick and fast, by flood and field, at home and abroad, in business and in pleasure; whose cattle died, whose crops were blighted, and about whose bed and board, invisible, unwelcome, and mischievous guests held their revels; who saw not in his calamities the results of ignorance and error, to be averted by caution, nor the inflictions of Heaven to be borne with resignation, but was the victim of a compact, in which his disasters were part of the price paid by the powers of darkness for an immortal soul! He who pined in consumption supposed that his own waxen effigy was revolving and melting at the charmed fire; the changes of his sensations told him when wanton cruelty damped the flame, to waste it lingeringly, or roused it in the impatience of revenge: and when came those sharp and shooting pains, the hags were thrusting in their bodkins, and their laugh rang in his ears: they sat upon his breast asleep,—he awoke gasping, and, as he started up, he saw them melting into air. Yet more miserable was the wight whom the fiends were commissioned bodily to possess;—with whose breathing frame an infernal substance was incorporate and almost identified;—whose thoughts were sufferings, and his words involuntary blasphemies. Can we wonder that all this was not borne passively;—that its authors were hunted out, even, if needful, by their own charms;—that suspicion grew into conviction, and conviction demanded vengeance;—that it was deemed a duty to hold them up to public hatred, and drag them to the bar of public justice;—and that their blood was eagerly thirsted after, of which the shedding was often believed not merely a righteous retribution, but the only efficient relief for the sufferers?

"The notion of witchcraft was no innocent and romantic superstition, no scion of an elegant mythology, but was altogether vulgar, repulsive, bloody, and loathsome. It was a foul ulcer on the face of humanity. Other vagaries of the mind have been associated with lofty or with gentle feelings;—they have belonged more to sportiveness than to criminality;—they are the poetry interspersed on the pages of the history of opinions;—they seem to be dreams of sleeping reason, and not the putrescence of its mouldering carcase; but this has no bright side, no redeeming quality whatever."[39]

The human body is not more liable to contagion than is that faculty of the mind which is called imagination. That many of the accused believed in their crime, we have sufficient evidence in their own voluntary confessions, as well as in the traditions handed down to us on this subject. Both knavery and delusion were at work, as the following incidents will abundantly manifest. They have been selected from a wide range of materials on this important topic, as illustrating the varied operations of the same delusion on different orders and grades of mind,—the temptations warily suited to each disposition, all tending to the same crime, and ultimately to the same punishment.

Our lusty miller had no children: it was a secret source of grief and anxiety to his dame, and many an hour of repining and discontent was the consequence. Yet Giles Dickisson's song was none the heavier; and if his wheel went merrily round, his spirits whirled with it, and danced and frolicked in the sunshine of good humour, like the spray and sparkle from his own mill-race. But a change was gathering on his wife's countenance: her grief grew sullen; her aspect stern and forbidding:—some hidden purpose was maturing: she seldom spoke to her husband. When addressed, she seemed to arouse from a sort of stupor, unwillingly forcing a reply. "She is bewitched," thought Giles. He had his suspicions; but he could not confidently point out the source of the mischief.

One evening, as Goody Dickisson was sitting alone, pondering and discontented, there came in one Mal Spencer, a dark and scowling hag, to whom Giles bore no good-will. He had beforetime forbidden his wife to hold any intercourse with this witch-woman, who was an object generally of suspicion and mistrust. If the "evil eye" can be supposed to inhabit a human frame, this old woman had an undisputed claim to its possession. This night, however, old Molly came hobbling in without further ceremony than a "Good e'en, thou Dickisson wife," and took her seat opposite the dame in the miller's own chair. "Aroynt thee, witch," should have been returned to such an ill-omened salute; but the miller's wife was either unwilling or unable to utter this well-known preservative against the malice of the Evil Ones.

The horse-shoe had been taken down from the door, and the blessed herb, moly, was incautiously thrown aside; neither had Goody Dickisson offered up the usual petition that evening, to be defended from the snares of the devil. Her discontent was too great, and she was in a fitter mood for murmuring than prayer.

Leaning her long thin chin upon a little crutch, and throwing her bleared eyes full upon the dame, old Molly abruptly exclaimed, in a voice like the croaking of a raven—

"Thou hast asked for children, but they are denied thee. What said I to thee, Goody Dickisson, in the clough yonder, by the hollow trunk of the oak? Rememberest thou, when thou saidest thou wouldst pawn thy body for the wish of thy soul?"

Dame Dickisson waxed pale, and her knees shook; but the hag went on.

"Worship the master I serve, and thou shalt have thy desire—ay and more!"

"More!—What meanest thou?"

"Come to the feast, as I have bidden thee. If thou likest not the savour of our company, thou shalt depart, and without harm."

"But who shall give me a safe conduct that I come back, and harmless as I went? Once in your possession, methinks"——

"What!" shouted the beldame, with a look of dark and devilish malignity:—"the word of a prince! Shall Goody Dickisson, the miller's wife, hold it in distrust? Go, poor fool, and chew thy bitterness, and bake thy bannocks, and fret thy old husband until thy writhen flesh rot from thy bones, and thou gnawest them for malice and vexation. Is it not glorious to ride on the wind—to mount the stars—to kiss the moon through the dark rolling clouds, when the blast scatters them in its might? To ride unharmed on their huge peaks tipped with thunder? To be for ever young in desire and enjoyment, though old and haggard, and bent double with age and infirmities? To have our wish and our revenge—ay, and the bodies of our enemies wasting before our spells, like wax to the flame? But go, sneak and drivel, and mind thy meal and barley-cakes, and go childless to thy grave."

She rose as if to depart; but Goody Dickisson's evil destiny prevailed, and she promised to attend the feast, with this condition only, that no harm should befall her, nor force nor entreaty should be used to win her consent to join their confederacy. But she returned not from that unhallowed assembly until body and soul were for ever under the dominion of the destroyer.

The mill went merrily on no more, and the miller's song was still. He looked a heavy and a doomed man. Strange suspicions haunted him. His wife's ill-humour he could have borne; but her very laugh now made him tremble: it was as if the functions of mind and body were animated by a being distinct from herself. Her countenance showed not that her thoughts mingled in either mirth or misery, except at times, when terrible convulsions seemed to pass over like the sudden roll of the sea, tossed by some unseen and subterraneous tempest. The neighbours began to shun his dwelling. His presence was the signal for stolen looks and portentous whispers. To church his wife never came; but the bench, her usual sitting-place, was deserted. At the church-doors, after sermon, when the price of grain, the weather, and other marketable commodities were discussed and settled, Giles was evidently an object of avoidance, and left to trudge home alone to his own cheerless and gloomy hearth.

Dick Hargreave's only cow was bewitched. The most effectual and approved method of ascertaining under whose spell she laboured was as follows:—

The next Friday, a pair of breeches was thrown over the cow's horns; she was then driven from the shippen with a stout cudgel. The place to which she directed her flight was carefully watched, for there assuredly must dwell the witch. To the great horror and dismay of Giles Dickisson, the cow came bellowing down the lane, tail up, in great terror—telling, as plain as beast could speak, of her distress, until she came to a full pause, middle deep in his own mill-dam. This was a direct confirmation to his suspicions; but the following was a more undeniable proof, if need were, of his wife's dishonest confederacy with the powers of darkness.

One morning, ere his servant-man Robin had taken the grey mare from the stable, Giles awoke early, and found his wife had not lain by his side. He had beforetime felt half roused in the night from a deep but uneasy slumber; but he was too heavy and bewildered to recollect himself, and sleep again overcame him ere he could satisfy his doubts. He had either dreamt, or fancied he had dreamt, that his wife was, at some seasons, away for a whole night together, and he was rendered insensible by her spells. This morning, however, he awoke before the usual time, probably from some failure in the charm, and he met her as she was ascending the stairs. Something like alarm or confusion was manifest. She had been to look after the cattle, she stammered out, scolding Robin for an idle lout to lie a-bed so long. The stable-door was open. With an aching heart, he went in. The grey mare was in a bath of foam, panting and distressed as though from some recent journey. Whilst pondering on this strange occurrence, Robin came in. His master taxed him with dishonesty. After much ado, he confessed that his mistress had many times of late borrowed the mare for a night, always returning before the good man awoke. Giles was too full of trouble to rate Robin as he deserved, contenting himself with many admonitions and instructions how to act in the next emergency.

Not many nights after, as Robin was late in the stable, his mistress came with the usual request, and her magic bridle in her hand.

"Now, good Robin, the cream is in the bowl, and the beer behind the spigot, and my good man is in bed."

"Whither away, mistress?" said Robin, diligently whisping down and soothing the mare, who trembled from head to foot when she heard her mistress's voice.

"For a journey, Robin. I have business at Colne; but I will not fail to come back again before sunrise."

"Ay, mistress, this is always your tale; but measter catched her in a woundy heat last time, and will not let her go."

"But, Robin, she shall be in the stable and dry two hours before my old churl gets up."

"But measter says she maunna go."

"Thou hast told him, then,—and a murrain light on thee!"

With eyes glistening like witch-fires, did the dame bestow her malison. Robin half-repented his refusal; but he was stubborn, and his courage not easily shaken. Besides, he had bragged at the last Michaelmas feast that he cared not a rush for never a witch in the parish. He had an Agnus Dei in his bosom, and a leaf from the holy herb in his clogs; and what recked he of spells and incantations? Furthermore, he had a waistcoat of proof given to him by his grandmother.[40]

"Since thou hast denied me the mare, I'll take thee in her place."

Robin felt in his bosom for the Agnus Dei cake, but it was gone!—He had thrown of his waistcoat, too, for the work, and his clogs were lying under the rack. Before he could furnish himself with these counter-charms, Goody Dickisson threw the bridle upon him, using these portentous words:—

"Horse, horse, see thou be;

And where I point thee carry me."

Swift as the rush of the wind, Robin felt their power. His nature changed: he grew more agile and capacious; and without further ado, found Goody upon his back, and his own shanks at an ambling gallop on the high-road to Pendle. He panted and grew weary, but she urged him on with an unsparing hand, lashing and spurring with all her might, until at last poor Robin, unused to such expedition, flagged and could scarcely crawl. But needs must when the witches drive. Rest and despite were denied, until, almost dead with toil and terror, he halted in one of the steep gullies of Pendle near to Malkin Tower.

It was an old grey-headed ruin, solitary and uninhabited. The cold October wind whistled through its joints and crannies;—the walls were studded with bright patches of moss and lichen;—darkness and desolation brooded over it, unbroken by aught but the cry of the moor-fowl and the stealthy prowl of the weasel and wild cat.

But this lonesome and time-hallowed ruin was now lit up as for some gay festival; lights were flickering through the crevices, and the coming of the guests, each mounted on her enchanted steed, was accompanied by loud and fiend-like acclamations. Shrieks and howlings were borne from afar upon the blast. Unhallowed words and unutterable curses came on the hollow wind. Forms of indescribable and abominable shape flitted through the troubled elements. Robin, trembling all over with fright and fatigue, was told by his mistress to graze where he could, while she went into the feast:—"Make good use of thy time, for in two hours I shall mount thee back again."

This was poor sustenance for Robin's stomach,—furze and heath were not at all to his mind, and he peeped about for a quiet resting-place. Here he was kicked and bitten by others of the herd; several of them were in the like pitiable condition with himself; but some were really of the brute kind, and these fared the best and were better mannered than most of their human companions. Often did our unfortunate hero wish himself in their place. Having little else to do, he was prompted by curiosity to approach the building, from whence the loud din of mirth and revelry grated harshly on his ears. A long chink disclosed to him some part of the mysteries within. There sat on the floor a great company of witches, feasting and cramming with all their might. An elderly gentleman of a grave and respectable deportment, clad in black doublet and hosen, sat on a stone-heap at the head, from whence he dealt out the delicacies with due care and attention. This was a mortifying sight to a hungry stomach, and Robin's humanity yearned at the display. After the first emotions had a little subsided, he found himself at leisure to examine the faces of the opposite guests, and he recognised several dames of his acquaintance, feasting right merrily at the witches' board. Either his fears and "thick-coming fancies" deceived him, or, as he afterwards declared, he saw nearly the whole of the neighbourhood at the assembly.

Presently it seemed as if the first course were ended, and the floor cleared by invisible hands in a twinkling.

"Now pull," said the grave personage in black.

Many ropes hung from the roof. These the women began to pull furiously, when down came pies, puddings, milk, cream, and rare wines, which they caught in wooden bowls; likewise sweet-meats and all manner of dainties, which made Robin's mouth to water so at the sight that he could bear it no longer. Intending to groan, he involuntarily uttered a loud neigh, which so alarmed the company that the lights were extinguished, and the guests sallied out, each immediately bestriding her steed, and setting forth at full gallop, save Goody Dickisson, who, in attempting to mount Robin, met with a sore mishap. Recollecting the charm which operated upon him, he gave his head a sudden fling: as good luck would have it, the bridle became entangled about her neck. His speech now came again, and he cried out—

"Mare, mare, see thou be;

And where I point thee carry me."

Suddenly she was metamorphosed, and Robin in his turn bestrode the witch. He spared her not, as will readily be imagined, until he had her safe in her own stable before break of day. Leaving her there with the bridle about her neck, he entered the house, hungry and jaded. Soon he heard Giles coming down-stairs in a great hurry—

"How now, sirrah!" cried the incensed miller; "did I not tell thee to forbid thy mistress the mare?"

"Why, master," replied Robin, scratching his head, "and so I have—the beast hasna' been ridden sin' ye backed her on Friday."

"Thou art a lying hound to look me in the face and say so. Thy mistress hath been out again last night upon her old errands—I found it out when I awaked."

"And what's the matter of that?" said Robin, with great alacrity. "Ye may go see, master, an' ye liken—the mare's as dry as our meal-tub, and as brisk as bottled ale."

Giles turned angrily away from him towards the stable, tightening a tough cudgel in his grasp, with which he intended to belabour the unfortunate hind on his return. Nor was he long absent—Robin had scarcely swallowed a mouthful of hot porridge when his master thus accosted him—

"Why, thou hob thrust, no good can come where thy fingers are a-meddling; there is another jade besides mine own tied to the rack, not worth a groat. Dost let thy neighbours lift my oats and provender? Better turn my mill into a spital for horses, and nourish all the worn-out kibboes i' the parish!"

"Nay, measter, the beast is yours; and ye ha' foun' her bed and provender these twenty years."

"I'll cudgel that lying spirit out o' thee," said Giles, wetting his hands for a firm grasp at the stick.

"Hold, master!" said Robin, stepping aside; "she has cost you more currying than all the combs in the stable are worth. Step in and take off the bridle, and then say whose beast she is, and who hath most right to her, you or your neighbours. But mind, when the bridle is off her neck, she slip it not on to yours; for if she do you are a gone man."

Giles stayed not, but ran with great haste into the stable. The tired beast could scarcely stand; but he pulled off the bridle, and—as Robin told the tale—his own spouse immediately stood confessed before him!

Here we pause. In the next part we shall rapidly sketch another of the traditions current on this strange subject. It will but be a brief and shadowy outline: space forbids us to dilate: the whole volume would not contain the stories that tradition attributes to the prevalence of this unnatural and revolting, though, it may be, imaginary crime.

FOOTNOTES:

[37]![]() , or the rocky

district.

, or the rocky

district.

[38] Col-dwr, or narrow water. See Whitaker's etymology of the word (Hist. of Manchester).

[39] See an able article on this subject in the Retrospective Review, vol. v. part i.

[40] "On Christmas daie at night, a threed must be sponne of flax, by a little virgine girl, in the name of the divell; and it must be by her woven, and also wrought with the needle. On the breste or fore part thereof must be made, with needlework, two heads; on the head of the right side must be a hat, and a long beard,—the left head must have on a crown, and it must be so horrible that it maie resemble Belzebub; and on each side of the wastcote must be made a crosse."—Discoverie of Witchcraft, by Reginald Scott, 1584.

PART SECOND.

On the verge of the Castle Clough, a deep and winding dingle, once shaded with venerable oaks, are the small remains of the Castle of Hapton, the seat of its ancient lords, and, till the erection of Hapton Tower, the occasional residence of the De la Leghs and Townleys. Hapton Tower is now destroyed to its foundation. It was a large square building, and about a hundred years ago presented the remains of three cylindrical towers with conical basements. It also appears to have had two principal entrances opposite to each other, with a thorough lobby between, and seems not to have been built in the usual form,—that of a quadrangle. It was erected about the year 1510, and was inhabited until 1667. The family-name of the nobleman—for such he appears to have been—of whom the following story is told, we have no means of ascertaining. That he was an occasional resident or visitor at the Tower is but surmise. During the period of these dark transactions we find that the mansion was inhabited by Jane Assheton, relict of Richard Townley, who died in the year 1637. Whoever he might be, the following horrible event, arising out of this superstition, attaches to his memory. Whether it can be attributed to the operations of a mind just bordering on insanity, and highly wrought upon by existing delusions,—or must be classed amongst the proofs, so abundantly furnished by all believers in the reality of witchcraft and demoniacal possession, our readers must determine as we unfold the tale.

Lord William had seen, and had openly vowed to win, the proud maiden of Bernshaw Tower. He did win her, but he did not woo her. A dark and appalling secret was connected with their union, which we shall briefly develop.

Lady Sibyl, "the proud maiden of Bernshaw," was from her youth the creature of impulse and imagination—a child of nature and romance. She roved unchecked through the green valleys and among the glens and moorlands of her native hills; every nook and streamlet was associated with some hidden thought "too deep for tears," until Nature became her god,—the hills and fastnesses, the trackless wilds and mountains, her companions. With them alone she held communion; and as she watched the soft shadows and the white clouds take their quiet path upon the hills, she beheld in them the symbols of her own ideas,—the images and reflections,—the hidden world within her made visible. She felt no sympathy with the realities—the commonplaces of life; her thoughts were too aspiring for earth, yet found not their resting-place in heaven! It was no grovelling, degrading superstition which actuated her: she sighed for powers above her species,—she aspired to hold intercourse with beings of a superior nature. She would gaze for hours in wild delirium on the blue sky and starry vault, and wish she were freed from the base encumbrances of earth, that she might shine out among those glorious intelligences in regions without a shadow or a cloud. Imagination was her solace and her curse; she flew to it for relief as the drunkard to his cup, sparkling and intoxicating for a while, but its dregs were bitterness and despair. Soon her world of imagination began to quicken; and, as the wind came sighing through her dark ringlets, or rustling over the dry grass and heather bushes at her side, she thought a spirit spoke, or a celestial messenger crossed her path. The unholy rites of the witches were familiar to her ear, but she spurned their vulgar and low ambition; she panted for communion with beings more exalted—demigods and immortals, of whom she had heard as having been translated to those happier skies, forming the glorious constellations she beheld. Sometimes fancies wild and horrible assaulted her; she then shut herself for days in her own chamber, and was heard as though in converse with invisible things. When freed from this hallucination, agony was marked on her brow, and her cheek was more than usually pale and collapsed. She would then wander forth again:—the mountain-breeze reanimated her spirits, and imagination again became pleasant unto her. She heard the wild swans winging their way above her, and she thought of the wild hunters and the spectre-horseman:[41] the short wail of the curlew, the call of the moor-cock and plover, was the voice of her beloved. To her all nature wore a charmed life: earth and sky were but creatures formed for her use, and the ministers of her pleasure.

The Tower of Bernshaw was a small fortified house in the pass over the hills from Burnley to Todmorden. It stood within a short distance from the Eagle Crag; and the Lady Sibyl would often climb to the utmost verge of that overhanging peak, looking from its dizzy height until her soul expanded, and her thoughts took their flight through those dim regions where the eye could not penetrate.

One evening she had lingered longer than usual: she felt unwilling to depart—to meet again the dull and wearisome realities of life—the petty cares that interest and animate mankind. She loathed her own form and her own species:—earth was too narrow for her desire, and she almost longed to burst its barriers. In the deep agony of her spirit she cried aloud—

"Would that my path, like yon clouds, were on the wind, and my dwelling-place in their bosom!"

A soft breeze came suddenly towards her, rustling the dry heath as it swept along. The grass bent beneath its footsteps, and it seemed to die away in articulate murmurs at her feet. Terror crept upon her, her bosom thrilled, and her whole frame was pervaded by some subtle and mysterious influence.

"Who art thou?" she whispered, as though to some invisible agent. She listened, but there was no reply; the same soft wind suddenly arose, and crept to her bosom.

"Who art thou?" she inquired again, but in a louder tone. The breeze again flapped its wings, mantling upwards from where it lay, as if nestled on her breast. It mounted lightly to her cheek, but it felt hot—almost scorching—when the maiden cried out as before. It fluttered on her ear, and she thought there came a whisper—

"I am thy good spirit."

"Oh, tell me," she cried with vehemence: "show me who thou art!"—a mist curled round her, and a lambent flame, like the soft lightning of a summer's night, shot from it. She saw a form, glorious but indistinct, and the flashes grew paler every moment.

"Leave me not," she cried; "I will be thine!"

Then the cloud passed away, and a being stood before her, mightier and more stately than the sons of men. A burning fillet was on his brow, and his eyes glowed with an ever-restless flame.

"Maiden, I come at thy wish. Speak!—what is thy desire."

"Let thought be motion;—let my will only be the boundary of my power," said she, nothing daunted; for her mind had become too familiar with invisible fancies, and her ambition too boundless to feel either awe or alarm. Immediately she felt as though she were sweeping through the trackless air,—she heard the rush of mighty wings cleaving the sky,—she thought the whole world lay at her feet, and the kingdoms of the earth moved on like a mighty pageant. Then did the vision change. Objects began to waver and grow dim, as if passing through a mist; and she found herself again upon that lonely crag, and her conductor at her side. He grasped her hand: she felt his burning touch, and a sudden smart as though she were stung—a drop of blood hung on her finger. He unbound the burning fillet, and she saw as though it were a glimpse of that unquenchable, unconsuming flame that devoured him. He took the blood and wrote upon her brow. The agony was intense, and a faint shriek escaped her. He spoke, but the sound rang in her ears like the knell of hopes for ever departed.

For words of such presumptuous blasphemy, tradition must be voiceless. The demon looked upwards; but, as if blasted by some withering sight, his eyes were suddenly withdrawn.

What homage was exacted, let no one seek to know.

After a pause, the deceiver again addressed her; and his form changed as he spoke.

"One day in the year alone thou shalt be subject to mischance. It is the feast of All-Hallows, when the witches meet to renew their vows. On this night thou must be as they, and must join their company. Still thou mayest hide thyself under any form thou shalt choose; but it shall abide upon thee until midnight. Till then thy spells are powerless. On no other day shall harm befall thee."

The maiden felt her pride dilate:—her weak and common nature she thought was no longer a degradation; she seemed as though she could bound through infinite space. Already was she invested with the attributes of immateriality, when she awoke!—and in her own chamber, whither the servants had conveyed her from the crag an hour before, having found her asleep, or in a swoon, upon the verge of the precipice. She looked at her hand; the sharp wound was there, and she felt her brow tingle as if to remind her of that irrevocable pledge.

Lord William sued in vain to the maid of Bernshaw Tower. She repulsed him with scorn and contumely. He vowed that he would win her, though the powers of darkness withstood the attempt. To accomplish this impious purpose, he sought Mause, the witch's dwelling. It was a dreary hut, built in a rocky cleft, shunned by all as the abode of wicked and malignant spirits, which the dame kept and nursed as familiars, for the fulfilment of her malicious will.

The night was dark and heavy when Lord William tied his steed to a rude gate that guarded the entrance to the witch's den. He raised the latch, but there was no light within.

"Holloa!" cried the courageous intruder; but all was dark and silent as before. Just as he was about to depart he thought he heard a rustling near him, and presently the croaking voice of the hag close at his ear.

"Lord William," said she, "thou art a bold man to come hither after nightfall."

He felt something startled, but he swerved not from his purpose.

"Can'st help me to a bride, Mother Helston?" cried he, in a firm voice; "for I feel mightily constrained to wed!"

"Is the doomed maiden of Bernshaw a bride fit for Lord William's bosom?" said the invisible sorceress.

"Give me some charm to win her consent,—I care not for the rest."

"Charm!" replied the beldame, with a screech that made Lord William start back. "Spells have I none that can bind her. I would she were in my power; but she hath spell for spell. Nought would avail thee, for she is beyond my reach; her power would baffle mine?"

"Is she too tainted with the iniquity that is abroad?"

"I tell thee yea; and my spirit must bow to hers. Wouldst wed her now—fond, feeble-hearted mortal?"

Lord William was silent; but the beautiful form of the maiden seemed to pass before him, and he loved her with such overmastering vehemence that if Satan himself had stood in the gap he would not have shrunk from his purpose.

"Mause Helston," said the lover, "if thou wilt help me at this bout, I will not draw back. I dare wed her though she were twice the thing thou fearest. Tell me how her spell works,—I will countervail it,—- I will break that accursed charm, and she shall be my bride!"

For a while there was no reply; but he heard a muttering as though some consultation were going on.

"Listen, Lord William," she spoke aloud. "Ay, thou wilt listen to thine own jeopardy! Once in the year—'tis on the night of All-Hallows—she may be overcome. But it is a perilous attempt!"

"I care not. Point out the way, and I will ride it rough-shod!"

The beldame arose from her couch, and struck a light. Ere they separated the morning dawned high above the grey hills. Many rites and incantations were performed, of which we forbear the disgusting recital. The instructions he received were never divulged; the secrets of that night were never known; but an altered man was Lord William when he came back to Hapton Tower.

On All-Hallows' day, with a numerous train, he went forth a-hunting. His hounds were the fleetest from Calder to Calder; and his horns the shrillest through the wide forests of Accrington and Rossendale. But on that morning a strange hound joined the pack that outstripped them all.

"Blow," cried Lord William, "till the loud echoes ring, and the fleet hounds o'ertake yon grizzled mongrel."

Both horses and dogs were driven to their utmost speed, but the strange hound still kept ahead. Over moor and fell they still rushed on, the hounds in full cry, though as yet guided only by the scent, the object of their pursuit not being visible. Suddenly a white doe was seen, distant a few yards only, and bounding away from them at full speed. She might have risen out of the ground, so immediate was her appearance. On they went in full view, but the deer was swift, and she seemed to wind and double with great dexterity. Her bearing was evidently towards the steep crags on the east. They passed the Tower of Bernshaw, and were fast approaching the verge of that tremendous precipice, the "Eagle Crag." Horse and rider must inevitably perish if they follow. But Lord William slackened not in the pursuit; and the deer flew straight as an arrow to its mark,—the very point where the crag jutted out over the gulf below. The huntsmen drew back in terror; the dogs were still in chase, though at some distance behind;—Lord William only and the strange hound were close upon her track. Beyond the crag nothing was visible but cloud and sky, showing the fearful height and abruptness of the descent. One moment, and the gulf must be shot:—his brain felt dizzy, but his heart was resolute.

"Mause, my wench," said he, "my neck or thine!—Hie thee; if she's over, we are lost!"

Lord William's steed followed in the hound's footsteps to a hair. The deer was almost within her last spring, when the hound, with a loud yell, doubled her, scarcely a yard's breadth from the long bare neb of that fearful peak, and she turned with inconceivable speed so near the verge that Lord William, in wheeling round, heard a fragment of rock, loosened by the stroke from his horse's hoof, roll down the precipice with a frightful crash. The sudden whirl had nearly brought him to the ground, but he recovered his position with great adroitness. A loud shriek announced the capture. The cruel hound held the deer by the throat, and they were struggling together on the green earth. With threats and curses he lashed away the ferocious beast, who growled fiercely at being driven from her prey. With looks of sullenness and menace, she scampered off, leaving Lord William to secure the victim. He drew a silken noose from his saddle-bow, and threw it over the panting deer, who followed quietly on to his dwelling at Hapton Tower.

At midnight there was heard a wild and unearthly shriek from the high turret, so pitiful and shrill that the inmates awoke in great alarm. The loud roar of the wind came on like a thunder-clap. The tempest flapped its wings, and its giant arms rocked the turret like a cradle. At this hour Lord William, with a wild and haggard eye, left his chamber. The last stroke of the midnight bell trembled on his ear as he entered the western tower. A maiden sat there, a silken noose was about her head, and she sobbed loud and heavily. She wrung her white hands at his approach.

"Thy spells have been o'ermastered. Henceforth I renounce these unholy rites; I would not pass nights of horror and days of dread any longer. Maiden, thou art in my power. Unless thou wilt be mine,—renouncing thine impious vows,—for ever shunning thy detested arts,—breaking that accursed chain the enemy has wound about thee,—I will deliver thee up to thy tormentors, and those that seek thy destruction. This done, and thou art free."

The maiden threw her snake-like glance upon him.

"Alas!" she cried, "I am not free. This magic noose! remove it, and my promise shall be without constraint."

"Nay, thou arch-deceiver,—deceiver of thine own self, and plotter of thine own ruin,—I would save thee from thy doom. Promise, renounce, and for ever forswear thy vows. The priest will absolve thee; it must be done ere I unbind that chain."

"I promise," said the maiden, after a deep and unbroken silence. "I have not been happy since I knew their power. I may yet worship this fair earth and yon boundless sky. This heart would be void without an object and a possession!"

She shed no tear until the holy man, with awful and solemn denunciations, exorcised the unclean spirit to whom she was bound. He admonished her, as a repentant wanderer from the flock, to shun the perils of presumption, reminding her that HE, of whom it is written that He was led up of the Spirit into the wilderness to be tempted of the devil,—HE who won for us the victory in that conflict, taught us in praying to say, "Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil." She was rebaptized as one newly born, and committed again to the keeping of the Holy Church. Shortly afterwards were united at the altar Lord William and Lady Sibyl. He accompanied her to Bernshaw Tower, their future residence,—becoming, in right of his wife, the sole possessor of those domains.

FOOTNOTES:

[41] In Lancashire these noises are called the Gabriel Ratchets, according to Webster, which seem to be the same with the German Rachtvogel or Rachtraven. The word and the superstition are still prevalent. Gabriel Ratchets are supposed to be like the sound of puppies yelping in the air, and to forebode death or misfortune.

PART THIRD.

Twelve months were nigh come and gone, and the feast of All-Hallows was again at hand. Lord William's bride sat in her lonely bower, but her face was pale, and her eyes red with weeping. The tempter had been there; and she had not sought for protection against his snares. That night she was expected to renew her allegiance to the prince of darkness. Those fearful rites must now bind her for ever to his will. Such appeared to be her infatuation that it led her to imagine she was yet his by right of purchase, without being fully conscious of the impiety of that thought. His own power had been promised to her: true, she must die; but might she not, a spirit like himself, rove from world to world without restraint? She thought—so perilously rapid was her relapse and her delusion—that his form had again passed before her, beautiful as before his transgression!—"The Son of the Morning!" arrayed in the majesty which he had before the world was,—ere heaven's Ruler had hurled him from his throne. Her mental vision was perverted. Light and darkness, good and evil, were no longer distinguished. Perhaps it was a dream; but the imagination had becomed diseased, and she distinguished not its inward operations from outward impressions on the sense. Her husband was kind, and loved her with a lover's fondness, but she could not return his affection. He saw her unhappy, and he administered comfort; but the source of her misery was in himself, and she sighed to be free?

"Free!"—she started; the voice was an echo to her thought. It appeared to be in the chamber, but she saw no living form. She had vowed to renounce the devil and all his works in her rebaptism, before she was led to the altar, and how could she face her husband?

"He shall not know of our compact."

These words seemed to be whispered in her ear. She turned aside; but saw nothing save the glow of sunset through the lattice, and a wavering light upon the floor.

"I would spare him this misery," she sighed. "Conceal but the secret from him, and I am again thine!"

Suddenly the well-known form of her familiar was at her side.

The following day was All-Hallows-e'en, and her allegiance must be renewed in the great assembly of his subjects held on that fearful night.

It was in the year 1632, a period well known in history as having led to the apprehension of a considerable number of persons accused of witchcraft. The depositions of these miserable creatures were taken before Richard Shuttleworth and John Starkie, two of his Majesty's justices of the peace, on the 10th of February 1633; and they were committed to Lancaster Castle for trial.

Seventeen of them were found guilty, on evidence suspicious enough under ordinary circumstances, but not at all to be wondered at, if we consider the feeling and excitement then abroad. Some of the deluded victims themselves confessed their crime, giving minute and connected statements of their meetings, and the transactions which then took place. Justices of the peace, judges, and the highest dignitaries of the realm, firmly believed in these reputed sorceries. Even the great Sir Thomas Brown, author of the book intended as an exposure of "Vulgar Errors," gave his testimony to the truth and reality of those diabolical delusions. But we have little need to wonder at the superstition of past ages, when we look at the folly and credulity of our own.

It may, perhaps, be pleasing to learn that the judge who presided at the trial respited the convicts, and reported their case to the king in council. They were next remitted to Chester, where Bishop Bridgeman, certifying his opinion of the matter, four of the accused—Margaret Johnson, Frances Dickisson, Mary Spencer, and the wife of one Hargreaves—were sent to London and examined, first by the king's physicians, and afterwards by Charles I. in person. "A stranger scene can scarcely be perceived," says the historian of Whalley; "and it is not easy to imagine whether the untaught manners, rude dialect, and uncouth appearance of these poor foresters would more astonish the king; or his dignity of person and manners, together with the splendid scene by which they were surrounded, would overwhelm them."

The story made so much noise that plays were written on the subject, and enacted. One of them is entitled, "The late Lancashire Witches, a well-received Comedy, lately acted at the Globe on the Bank-side, by the King's Majesty's Actors. Written by Thomas Haywood and Richard Broom. Aut prodesse solent, aut delectare, 1634."

But our element is tradition, especially as illustrating ancient manners and superstitions; we therefore give the sequel of our tale as tradition hath preserved it.

Giles Dickisson, the merry miller at the Mill Clough, had so taken to heart his wife's dishonesty that, as we have before observed, he grew fretful and morose. His mill he vowed was infested with a whole legion of these "hell-cats," as they were called; for in this shape they presented themselves to the affrighted eyes of the miserable yoke-fellow, as he fancied himself, to a limb of Satan. The yells and screeches he heard o'nights from these witches and warlocks were unbearable; and once or twice, when late at the mill, both he and Robin had received some palpable tokens of their presence. Scratches and bloody marks were plainly visible, and every hour brought with it some new source of annoyance or alarm.

One morning Giles showed himself with a disconsolate face before Lord William at the Tower; he could bear his condition no longer.

"T'other night," said he, "the witches set me astride o' t' riggin' o' my own house.[42] It was a bitter cold time, an' I was nearly perished when I wakened. I am weary of my life, and will flit; for this country, the deil, I do think, holds in his own special keeping!"

Then Robin stept forward, offering to take the mill on his master's quittance. He cared not, he said, for all the witch-women in the parish. He had "fettled" one of them, and, by his Maker's help, he hoped fairly to drive them off the field. The bargain was struck, and Robin that day entered into possession.

By a strange coincidence, this transaction happened on the eve of All-Hallows before mentioned; and Lord William requested that Robin would on that night keep watch. His courage, he said, would help him through; and if he could rid the mill of them, the Baron promised him a year's rent, and a good largess besides. Robin was fain of the offer, and prepared himself for the strife, determined, if possible, to eject these ugly vermin from the premises.

On this same night, soon after sunset, the lady of Bernshaw Tower went forth, leaving her lord in a deep sleep, the effect, as it was supposed, of her own spells. Ere she departed, every symbol or token of grace was laid aside;—her rosary was unbound. She drew a glove from her hand, and in it was the bridle ring, which she threw from her,—when the flame of the lamp suddenly expired. It was in her little toilet-chamber, where she had paused, that she might pursue her meditations undisturbed. Her allegiance must be renewed, and revoked no more; but her pride, that darling sin for which she raised her soul, must first suffer. On that night she must be guided by the same laws, and subjected to the same degrading influence, as her fellow-subjects. At least once a year this condition must be fulfilled:—all rank and distinction being lost, the vassals were alike equal in subordination to their chief. On this night, too, the rights of initiation were usually administered.

The time drew nigh, and the Lady Sibyl, intending to conceal the glove with the sacred symbol, passed her hand on the table where it had lain—but it was gone!

In a vast hollow, nearly surrounded by crags and precipices, bare and inaccessible, the meeting was assembled, and the lady of the Tower was to be restored to their communion. Gliding like a shadow, came in the wife of Lord William,—pale, and her tresses dishevelled, she seemed the victim either of disease or insanity.

Under a tottering and blasted pine sat their chief, in a human form; his stature lofty and commanding, he appeared as a ruler even in this narrow sphere of his dominion. Yet he looked round with a glance of mockery and scorn. He was fallen, and he felt degraded; but his aim was to mar the glorious image of his Maker, and trample it beneath his feet.

A crowd of miserable and deluded beings came at the beck of their chief, each accompanied by her familiar. But the lady of Bernshaw came alone. Her act of renouncement had deprived her of this privilege.

The mandate having been proclaimed, and the preliminary rites to this fearful act of reprobation performed, the assembly waited for the concluding act—the cruel and appalling trial: one touch of his finger was to pass upon her brow,—the impress, the mark of the beast,—the sign that was to snatch her from the reach of mercy! Her spirit shuddered;—nature shrank from the unholy contact. Once more she looked towards that heaven she was about to forfeit,—and for ever!

"For ever!"—the words rang in her ears; their sound was like the knell of her everlasting hope. She started aside, as though she felt a horrid and scorching breath upon her cheek, as though she already felt their unutterable import in the abysses of woe!

Conscience, long slumbering, seemed to awake; she was seized with the anguish of despair! It seemed as though judgment were passed, and she was doomed to wander like some rayless orb in the blackness of darkness for ever. One fearful undefined form of terror was before her; one consciousness of offence ever present; all idea of past and future absorbed in one ever-during NOW, she felt that her misery was too heavy to sustain. A groan escaped her lips, but it was an appeal to that power for deliverance, who is not slow to hear, "nor impotent to save." Suddenly she was roused from some deep and overpowering hallucination; the promises of unlimited gratification to every wish prevailed no more, the tempter's charm was broken. All was changed; the whole scene seemed to vanish; and that form, which once appeared to her like an angel of light, fell prostrate, writhing away in terrific and tortuous folds on the hissing earth. The crowd scattered with a fearful yell;—she heard a rush of wings, and a loud and dissonant scream,—and the "Bride of Bernshaw" fell senseless to the ground.

We leave the conscience-stricken victim whilst we relate the result of Robin's watch-night at the mill.

He lay awake until midnight, but there was no disturbance; nothing was heard but the plash of the mill-stream, and the dripping ooze from the rocks. His old enemies, no doubt, were intimidated, and he was about commencing a snug nap on the idea—when, lo! there came a great rush of wind. He heard it booming on from a vast distance, until it seemed to sweep over the building in one wide resistless torrent that might have levelled the stoutest edifice;—yet was the mill unharmed by the attack. Then came shrieks and yells, mingled with the most horrid imprecations. Swift as thought, there rushed upon him a prodigious company of cats, bats, and all manner of hideous things, that scratched and pinched him, as he afterwards declared, until his flesh verily "reeked" again. Maddened by the torment, he began to lay about him lustily with a long whittle which he carried for domestic purposes. They gave back at so unexpected a reception. Taking courage thereby, Robin followed, and they fled, helter-skelter, like a routed army. Through loop-holes and windows went the obscene crew, with such hideous screeches as startled the whole neighbourhood. He gave one last desperate lunge as a parting remembrance, and felt that his weapon had made a hit. Something fell on the floor, but the light was extinguished in the scuffle, and in vain he attempted to grope out this trophy of his valour.

"I've sliced off a leg or a wing," thought he, "and I may lay hold on it in the morning."

All was now quiet, and Robin, to his great comfort, was left without further molestation.

Morning dawned bright and cheerful on the grey battlements of Bernshaw Tower; the sun came out joyously over the hills; but Lord William walked forth with an anxious and gloomy countenance. His wife had feigned illness, and the old nurse had tended her through the night in a separate chamber. This was the story he had learnt on finding her absent when he awoke. Early presenting himself at the door, he was refused admission. She was ill—very ill. The lady was fallen asleep, and might not be disturbed: such was the answer he received. Rising over the hill, he now saw the gaunt ungainly form of Robin, his new tenant, approaching in great haste with a bundle under his arm.

"What news from the mill, my stout warrior of the north?" said Lord William.

"I think I payed one on 'em, your worship," said Robin, taking the bundle in his hand. "Not a cat said mew when they felt my whittle. Marry, I spoilt their catterwauling: I've cut a rare shive!"

"How didst fare last night with thy wenches?" inquired the other.

"I've mended their manners for a while, I guess. As I peeped about betimes this morning, I found—a paw! If cats are bred with hands and gowden rings on their fingers, they shall e'en ha' sporting-room i' the mill! No bad luck, methinks."

Robin uncovered the prize, and drew out a bleeding hand, mangled at the wrist, and blackened as if by fire; one finger decorated with a ring, which Lord William too plainly recognised. He seized the terrific pledge, and, with a look betokening some deadly purpose, hastened to his wife's chamber. He demanded admittance in too peremptory a tone for denial. His features were still, not a ripple marked the disturbance beneath. He stood with a calm and tranquil brow by her bed-side; but she read a fearful message in his eye.

"Fair lady, how farest thou?—I do fear me thou art ill!"

"She's sick, and in great danger. You may not disturb her, my lord," said the nurse, attempting to prevent his too near approach;—"I pray you depart; your presence afflicts her sorely."

"Ay, and so it does," said Lord William, with a strange and hideous laugh. "I pray thee, lady, let me play the doctor,—hold out thy hand."

The lady was still silent. She turned away her head. His glance was too withering to endure.

"Nay, then, I must constrain thee, dame."

She drew out her hand, which Lord William seized with a violent and convulsive grasp.

"I fear me 'tis a sickness unto death; small hope of amendment here. Give me the other; perchance I may find there more comfort."

"Oh, my husband, I cannot;—I am—I have no strength."

"Why, thou art grown peevish with thy distemper. Since 'tis so, I must e'en force thy stubborn will."

"Alas! I cannot."

"If not thy hand, show me thy wrist!—I have here a match to it, methinks. O earth—earth—hide me in thy womb!—let the darkness blot me out and this blasting testimony for ever!—Accursed hag, what hast thou done?"

He seized her by the hair.

"What hast thou promised the fiend? Tell me,—or"—

"I have, oh, I fear I have,—consented to the compact!"

"How far doth it bind thee?"

"My soul—my better part!"

"Thy better part?—thy worse! A loathsome ulcer, reeking with the stench from the pit! Better have given thy body to the stake, than have let in one unhallowed desire upon thy soul. How far does thy contract reach?"

"All interest I can claim. His part that created it I could not give, not being mine to yield."

"Lost! lost! Thou hast, indeed, sold thyself to perdition! I'll purge this earth of witchery;—I'll make their carcases my weapon's sheath;—hence inglorious scabbard!" He flung away the sheath. Twining her dark hair about his fingers—"Die!—impious, polluted wretch! This blessed earth loathes thee,—the grave's holy sanctuary will cast thee out! Yon glorious sun would smite thee should I refrain!"

He raised his sword—a gleam of triumph seemed to flash from her eye, as though she were eager for the blow; but the descending weapon was stayed, and by no timid hand.

Lord William turned, yet he saw not the cause of its restraint. The lady alone seemed to be aware of some unseen intruder, and her eye darkened with apprehension. Suddenly she sprang from the couch; a shriek from no human agency escaped her, and the spirit seemed to have passed from its abode.

Lord William threw himself on her pale and inanimate form.

"Farewell!" he cried: "I had thought thee honest!—Nay, lost spirit, I must not say farewell!"

He gazed on his once-loved bride with a look of such unutterable tenderness that the heart's deep gush burst from his eyes, and he wept in that almost unendurable anguish. The sight was too harrowing to sustain. He was about to withdraw, when a convulsive tremor passed across her features—a trembling like the undulation of the breeze rippling the smooth bosom of the lake; a sigh seemed to labour heavily from her breast; her eyes opened; but as though yet struggling under the influence of some terrific dream, she cried—

"Oh, save me—save me!" She looked upwards: it was as if the light of heaven had suddenly shone in upon her benighted soul.

"Lost, saidst thou, accursed fiend?—Never until his power shall yield to thine!"

Yet she shuddered, as though the appalling shadow were still upon her spirit.—"Nay, 'twas but a dream."

"Dreams!" cried Lord William, recovering from a look of speechless amazement. "Thy dreams are more akin to truth than ever were thy waking reveries."

"Nay, my Lord, look not so unkindly on me—I will tell thee all. I dreamt that I was possessed, and this body was the dwelling of a demon. It was permitted as a punishment for my transgressions; for I had sought communion with the fiend. I was the companion of witches—foul and abominable shapes;—a beastly crew, with whom I was doomed to associate. Hellish rites and deeds, too horrible to name, were perpetrated. As a witness of my degradation, methought my right hand was withered. I feel it still! Yet—surely 'twas a dream!"

She raised her hand, gazing earnestly on it, which, to Lord William's amazement, appeared whole as before, save a slight mark round the wrist, but the ring was not there.

"What can this betide?" said the trembling sufferer. She looked suspiciously on this apparent confirmation of her guilt, and then upon her husband. "Oh, tell me that I did but dream!"

But Lord William spoke not.

"I know it all now!" she said, with a heavy sob. "My crime is punished; and I loathe my own form, for it is polluted. Yet the whole has passed but as some horrible dream—and I am free! This tabernacle is cleansed; no more shall it be defiled; for to Thee do I render up my trust."

A mild radiance had displaced the wild and unnatural lustre of her eye, as she looked up to the mercy she invoked, and was forgiven.

Her spirit was permitted but a brief sojourn in this region of sorrow. Ere another sun, her head hung lifeless on Lord William's bosom;—he had pressed her to his heart in token of forgiveness; but he held only the cold and clammy shrine—the idol had departed!

According to the popular solution of this fearful mystery, a demon or familiar had reanimated her form while she lay senseless at the sudden and unlooked-for dissolution of the witches' assembly. In this shape the imp had joined the rendezvous at the mill, and fleeing from the effects of Robin's valour, maliciously hoped that Lord William would execute a swift vengeance on his erring bride. But his hand was stayed by another and more merciful power, and the demon was cast out.

The ring and glove were not found. It was said that Mause Helston had taken them as a gage of fealty, and dying about the same period, was denied the rites of Christian burial. Hence may have arisen the belief which tradition has preserved respecting the Lady Sibyl.

Popular superstition still alleges that her grave was dug where the dark "Eagle Crag" shoots out its cold bare peak into the sky. Often, it is said, on the eve of All-Hallows, do the hound and the milk-white doe meet on the crag—a spectre huntsman in full chase. The belated peasant crosses himself at the sound as he remembers the fate of "The Witch of Bernshaw Tower."

FOOTNOTES:

[42] "Riggin'" or ridging. The hills which divide the counties of York and Lancaster are sometimes called "th' riggin'," from their being the highest land between the two seas forming part of what is called the backbone of England. An individual residing at a place named "The Summit," from its situation, was asked where he lived. "I live at th' riggin' o' th' warld, I reckon," says he; "for th' water fro' t' one side o' th' roof fa's to th' east sea, an' t' other to th' west sea."