Traditions of Lancashire by John Roby

THE SEER.

"Petruchio. Pray, have you not a

daughter

Call'd Katharina, fair and virtuous?

Baptista. I have a daughter, sir, call'd

Katharina,"

Taming of the Shrew, Act II. Scene I.

"What sudden chance is this, quoth he,

That I to love must subject be,

Which never thereto would agree,

But still did it defie?"

King Cophetua and the Beggar-maid.

"Yet she was coy, and would not believe

That he did love her so;

No, nor at any time would she

Any countenance to him show."

The Bailiff's Daughter of Islington.

The wonderful exploits of Edward Kelly, one of which is recorded in the following narrative, would, if collected, fill a volume of no ordinary dimensions. He was for a considerable time the companion and associate of John Dee, by courtesy called Doctor, from his great acquirements, performing for him the office of seer, a faculty not possessed by Dee, who was in consequence obliged to have recourse to Kelly for the revelations he has published respecting the world of spirits. These curious transactions may be found in Casaubon's work, entitled "A true and faithful Relation of what passed for many Years between Dr John Dee and some Spirits,"—opening out another dark page in the history of imposture and credulity. Dee says that he was brought into unison with Kelly by the mediation of the angel Uriel. Afterwards he found himself deceived by him in his opinion that these spirits, which ministered unto him, were messengers of the Deity.

They had several quarrels before-time; but when he found Kelly degenerating into the worst species of the magic art for purposes of avarice and fraud, he broke off all connection with him, and would never afterwards be seen in his company. Kelly, being discountenanced by the Doctor, betook himself to the meanest practices of magic, in all which money and the works of the devil appear to have been his chief aim. Many wicked and abominable transactions are recorded of him. Wever, in his "Funereal Monuments," records that Kelly, in company with one Paul Waring, who acted with him in all his conjurations, went to the churchyard of Walton-le-Dale, near Preston, where they had information of a person being interred who was supposed to have hidden a considerable sum of money, and to have died without disclosing where it was deposited. They entered the churchyard exactly at midnight, and having had the grave pointed out in the preceding day, they opened it and the coffin, exorcising the spirit of the deceased until it again animated the body, which rose out of the grave and stood upright before them. It not only satisfied their wicked desires, it is said, but delivered several strange predictions concerning persons in the neighbourhood, which were literally and exactly fulfilled.

In "Lilly's Memoirs" we have the following account of him:—

"Kelly outwent the Doctor—viz., about the elixir and philosopher's stone, which neither he nor his master attained by their own labour and industry. It was in this manner Kelly obtained it, as I had it related from an ancient minister, who new the certainty thereof from an old English merchant resident in Germany, at what time both Kelly and Dee were there.

"Dee and Kelly being on the confines of the emperor's dominions, in a city where resided many English merchants, with whom they had much familiarity, there happened an old friar to come to Dr Dee's lodging, knocking at the door. Dee peeped down the stairs:—'Kelly,' says he, 'tell the old man I am not at home.' Kelly did so. The friar said, 'I will take another time to wait on him.' Some few days after, he came again. Dee ordered Kelly, if it were the same person, to deny him again. He did so; at which the friar was very angry. 'Tell thy master I came to speak with him and to do him good, because he is a great scholar and famous;—but now tell him, he put forth a book, and dedicated it to the emperor. It is called 'Monas Hieroglyphicas.' He understands it not. I wrote it myself. I came to instruct him therein, and in some other more profound things. Do thou, Kelly, come along with me; I will make thee more famous than thy master Dee. Kelly was very apprehensive of what the friar delivered, and thereupon suddenly retired from Dee, and wholly applied unto the friar, and of him either had the elixir ready made, or the perfect method of its preparation and making. The poor friar lived a very short time after; whether he died a natural death, or was otherwise poisoned or made away by Kelly, the merchant who related this did not certainly know."

Kelly was born at Worcester, and had been an apothecary. He had a sister who lived there for some time after his death, and who used to exhibit some gold made by her brother's projection. "It was vulgarly reported that he had a compact with the devil, which he outlived, and was seized at midnight by infernal spirits, who carried him off in sight of his family, at the instant he was meditating a mischievous design against the minister of the parish, with whom he was greatly at enmity."

It would have been easy to select a more historical statement of facts respecting Kelly; but the following tale, the events of one day only, will, we hope, be more interesting to the generality of readers. It exhibits a curious display of the intrigues and devices by which these impostors acquired an almost unlimited power over the minds of their fellow-men. Human credulity once within their grasp, they could wield this tremendous engine at their will, directing it either to good or bad intents, but more often to purposes of fraud and self-aggrandisement.

In the ancient and well-thriven town of Manchester formerly dwelt a merchant of good repute, Cornelius Ethelstoun by name. Plain dealing and an honest countenance withal, had won for him a character of no ordinary renown. His friezes were the handsomest; his stuffs and camlets were not to be sampled in the market, or even throughout the world; insomuch that the courtly dames of Venice, and the cumbrous vrows of Amsterdam and the Hague, might be seen flaunting in goodly attire gathered from the store-houses of Master Cornelius.

His coffers glittered with broad ducats, and his cabinets with the rarest productions of the East. His warehouses were crammed, even to satiety, and his trestles groaned under heaps of rich velvets, costly brocades, and other profitable returns to his foreign adventures. But, alas!—and whose heart holdeth not communion with that word!—Cornelius was unhappy. He had one daughter, whom "he loved passing well;" yet, as common report did acknowledge, the veriest shrew that ever went unbridled. In vain did his riches and his revenues increase; in vain was plenty poured into his lap, and all that wealth could compass accumulate in lavish profusion. Of what avail was this outward and goodly show against the cruel and wayward temper of his daughter?

Kate—by this name we would distinguish her, as veritable historians are silent on her sponsorial appellation—Kate was unhappily fair and well-favoured. Her hair was dark as the raven-plume; but her skin, white as the purest statuary marble, grew fairer beneath the black and glossy wreaths twining gracefully about her neck. Her cheek was bright as the first blush of the morning, and ever and anon, as a deeper hue was thrown upon its rich but softened radiance, she looked like a vision from Mahomet's paradise—a being nurtured by a warmer sky and fiercer suns than our cold climate can sustain. She had lovers, but all approach was denied, and, one by one, they stood afar off and gazed. Her pretty mouth, lovely even in the proudest glance of petulance and scorn, was so oftentimes moulded into the same aspect that it grew puckered and contemptuous, rendering her disposition but too manifest; and yet—wouldest thou believe it, gentle reader?—she was in love!

Now it so fell out that on the very morning from which we date this first passage of our history, Cornelius awoke earlier than he was wont. His brow wore an aspect of more than ordinary care. It was but too evident that his pillow had been disturbed. Thoughts of more than usual perplexity had deprived him of his usual measure of repose. His very beard looked abrupt and agitated; his dress bore marks of indifference and haste. A slight, but tremulous movement of the head, in general but barely visible, was now advanced into a decided shake. With a step somewhat nimbler than aforetime, he made, as custom had long rendered habitual, his first visit to the counting-house.

The unwearied and indefatigable Timothy Dodge sat there, with the same crooked spectacles, and, as it might seem, mending the same pen which the same knife had nibbed for at least half-a-century. The tripod on which rested this grey Sidrophel of accompts looked of the like hard and impenetrable material, as though it were grown into his similitude, forming but a lower adjunct to his person. It was evident they had not parted company for the last twenty years. Nature had formed him awry. A boss or hump, of considerable elevation, extended like a huge promontory on one shoulder; from the other depended an arm longer by some inches than its fellow. As it described a greater arc its activity was proportionate. His grey and restless eyes followed the merchant's track with unwearied fidelity; yet was he a man full sparing of words—the ever ready "Anon, master," being the chief burden of his replications. It was like the troll of an old ballad—a sort of inveterate drawl tripping unwittingly from the tongue.

The sun was just peeping through the long dim casement as Cornelius stepped over the threshold of his sanctuary. In it lay hidden the mysteries of many a goodly tome, more precious in his eyes than the rarest and richest that Dee's library could boast. No mean value, inasmuch as this celebrated scholar and mathematician, who was lately appointed warden of the college, had the most costly store of book-furniture that individual ever possessed.

"Good morrow, Dodge."

The pen was twice nibbed ere the usual rejoinder.

"Are the camlets arrived from the country?" inquired the merchant.

"Anon, master—this forenoon may be."

"Is the accompt against Anthony Hardcastle discharged?"

"No," ejaculated the grim fixture.

"And where is the piece of Genoa velvet Dame Margery looked out yesterday for her mistress's wedding-suit? I do bethink me it is a good ell too long at the measure."

"Six ells, three nails, and an odd inch, besides the broad thumbs," replied Timothy.

"Right:—she reckoned on a good snip for waste; but let no more be sent than the embroiderer calls for."

"Not a thread," grunted Dodge.

A pause ensued. Some question was evidently hesitating on the merchant's tongue. Twice did his lips move, but the word fell unuttered. The affair was, however, finally disposed of as follows:—

"Hast heard of aught, Timothy, touching the private matter that I unfolded yesterday?" Cornelius put on as careless an aspect as the disquietude of his brow could needs carry, but the inquiry was evidently one of no ordinary interest. He twisted the points of his doublet, tied and untied the silk cords from his ruff, waiting Dodge's answer in a posture not much belying the anxiety he wished to conceal.

"Why, master, an' it were of woman's humours, the old seer himself could not unriddle their pranks."

Cornelius sighed, making the following hasty reply:—

"Thinkest thou this same seer could not give me a lift from out my trouble?"

"This same seer, I wot," replied Dodge, "is sore perplexed: some evil and mischievous aspect doth afflict the horoscope of the nation—Mars being conjunct with Venus and the Dragon's tail. Now, look to it, master, it is no light matter that will move him; but almost or ere I showed him the first glimpse of the business he waxed furious, and said that he cared not if all the unwed hussies in Christendom were hung up in a row, like rats on a string."

"It is Kate's birthday," answered the merchant, "to-night being the feast of St Bartlemy; but, as thou knowest well, the astrologer that cast her figure gave no hope of her amendment should this day pass and never a husband. Who would yoke with a colt untamed? O Timothy! it were well nigh to make an old man weep. I am a withered trunk. Better had I been childless than have this proud wench to trouble mine house."

The old man here wept, and it was a grievous thing to see his wrinkled cheeks become, as it were, but the sluices and channels of his tears. Timothy, too, was something moved from his common posture; and once he endeavoured to turn, as though he would hide his face from his master's trouble.

He sought to speak, but an evil and husky sort of humour settled in his throat, and he waited silently the subsiding of the sorrow he could not quell.

Cornelius raised his head: a sudden thought seemed to animate him. A ray had penetrated the gloomy envelope of his mind; and he peered through the casement intently eyeing the cool atmosphere.

"I'll visit the cunning man myself, Timothy. If he hear me not, then can I but return, weeping as I went." And with this speech he hastily departed.

Now on this, the morrow of St Bartlemy, it so happened that Kate also arose before the usual hour, and in a mood even more than ordinarily strange and untoward. Her maiden was like to find it a task of no slight enterprise, the attempt to adorn Kate's pretty person. Not a garment would fit. She threw the whole furniture of her clothes-press on a heap, and stamped on them for very rage. She looked hideous in her brown Venice waistcoat; frightful in her orange tiffany farthingale;— absolutely unbearable in her black velvet hood, wire ruff, and taffety gown. So that in the end she was nigh going to bed again in the sulks, had not a jacket of crimson satin, with slashed bodice, embroidered in gold twist, taken her fancy. Her little steel mirror, not always the object of such complacency, did for once reflect a beam of good humour, which so bewitched Kate that for the next five minutes she found herself settling into the best possible temper in the world.

"Give me my kerchief, lace scarf, and green silk hood, and my petticoat with the border newly purfled. Hark! 'Tis the bell for prayers. Be quick with my pantofles:—not those, wench—the yellow silk with silver spangles. Now my rings and crystal bracelets. I would not miss early matins to-day for the best jewel on an alderman's thumb."

"Anon, lady," replied her waiting-woman, with a sort of pert affectation of meekness. But what should cause Kate to be so wonderfully attentive to her devotions was a matter on which Janet could have no suspicions, or at least would not dare to show them if she had.

Kate, being now attired, tripped forth, accompanied by her maid. As she passed the half-closed door of the counting-house, Timothy, with one of his most leaden looks, full of unmeaning, stood edgeways in the opening, his lower side in advance, with the long arm ready for action.

"Fair mistress, Master Kelly would fain have a token to-day. He hath sent you a rare device!"

"And what the better shall I be of his mummeries?" hastily replied the lady. Timothy drew from his large leathern purse a curiously-twisted ribband.

"He twined this knot for your comfort. Throw it over your left shoulder, and it shall write the first letter of your gallant's name. A cypher of rare workmanship."

Kate, apparently in anger, snatched the magic ribband, and, peradventure it might be from none other design than to rid herself of the mystical love-knot, but she tossed it from her with an air of great contumely, when, by some disagreeable and untoward accident, it chanced to fly over the self-same shoulder to which Timothy had referred. He made no reply, but followed the token with his little grey eyes, apparently without any sort of aim or concernment. Kate's eyes followed too; but verily it were a marvellous thing to behold how the ribband shaped itself as it fell, and yet to see how she stamped and stormed. Quick as the burst of her proud temper she kicked aside the bauble, but not until the curl of the letter had been sufficiently manifest. Timothy drew back into his den, leaving the fair maid to the indulgence of her humours. But in the end Kate's wrath was not over-difficult to assuage. With an air somewhat dubious and disturbed she hastily thrust the token behind her stomacher and departed.

The merchant's house being nigh unto the market cross, Kate's prettily-spangled feet were soon safely conducted over the low stepping-stones placed at convenient distances for the transit of foot-passengers through the unpaved streets. Near a sort of style, guarding the entrance to the churchyard, rose an immense pile of buildings, cumbrous and uncouth. These were built something in the fashion of an inverted pyramid; to wit, the smaller area occupying the basement, and the larger spreading out into the topmost story. As she turned the corner of this vast hive of habitation—for many families were located therein—a gay cavalier, sumptuously attired, swept round at the same moment. Man and maid stood still for one instant. With unpropitious courtesy, an unlucky gust turned aside Kate's veil of real Flanders point; and the two innocents, like silly sheep, were staring into each other's eyes without either apology or rebuke. It did seem as though Kate were not without knowledge of the courtly beau: a rich and glowing vermilion came across her neck and face, like the gorgeous blush of evening upon the cold bosom of a snow-cloud. But the youth eyed her with a cool and deliberate glance, stepping aside carelessly as he passed by. She seemed to writhe with some concealed anguish; yet her lip curled proudly, and her bosom heaved, as though striving to throw off, with one last and desperate struggle, the oppression that she endured. In this disturbed and unquiet frame did Kate pass on to her orisons.

It may be needful to pause for a brief space in our narrative, whilst we give some account of this goodly spark who had so unexpectedly, as it might seem, unfitted the lady for the due exercise of her morning devotions.

His dress was elegant and becoming, and of the most costly materials. His hat was high and tapering, encircled by a rich band of gold and rare stones. It was further ornamented by a black feather, drooping gently towards the left shoulder. The brim was rather narrow; but then a profusion of curls fell from beneath, partly hiding his lace collar of beautiful workmanship and of the newest device. His beard was small and pointed; and his whiskers displayed that graceful wave peculiar to the high-bred gallants of the age. His neck was long, and the elegant disposal of his head would have turned giddy the heads of half the dames in the Queen's court. He wore a crimson cloak, richly embroidered: this was lined throughout with blue silk, and thrown negligently on one side. His doublet was grey, with slit sleeves; the arm parts, towards the shoulder, wide and slashed;—but who shall convey an adequate idea of the brilliant green breeches, tied far below the knee with yellow ribbands, red cloth hose, and great shoe-roses? For ourselves we own our incompetence, and proceed, glancing next at his goodly person. In size he was not tall nor unwieldy, but of a reasonable stature, such as denotes health, activity, and a frame capable of great endurance. He stepped proudly along, his very gait indicating superiority.

The town gallants looked on his person with envy, and on his light rapier with mistrust. In sooth, he was a proper man for stealing a lady's heart, either in hall or bower. Many had been his victims;—many were then in the last extremities of love. But of him it was currently spoken that he had never yet been subjected to its influence.

There be divers modes of falling into love. Some slip in through means of themselves; to wit, from sheer vanity, being never so well pleased as when they are the objects of admiration. Some from sheer contradiction, and from the well-known tendency of extremes to meet. Some, for very idlesse; and some for very love. But in none of these modes had the boy Cupid made arrow-holes through the heart of our illustrious hero; for, as we before intimated, no yielding place did seem visible, as the common discourse testified. How far this report was true the sequel of our history will set forth.

Now, this gay gallant being the wonder and admiration of the whole place, many were the unthrifty hours spent in such profitless discourse by the wives and daughters of the townsfolk, to the great discomfort and discredit of their liege lords. He was at present abiding in the college, where John Dee had apartments distinct from the warden's house, along with his former coadjutor and seer, Edward Kelly. Since the last quar rel between these two confederates, they had long been estranged; but Kelly had recently come for a season to visit his old master: when the Doctor returned from Trebona, in Bohemia, whence he had been invited back to his own country by Queen Elizabeth, he having received great honours and emoluments from foreign princes. This youth, being son to the governor of the castle at Trebona, was about to travel for his improvement and understanding in foreign manners. At the suit of his parents, Dee undertook the charge of his education and safe return. Since then young Rodolf had generally resided under Dr Dee's roof, and accompanied him on his accession to the wardenship. His accent was decidedly foreign, though he had resided some years in Britain, but not sufficiently so for Mancestrian ears to distinguish it from a sort of lisping euphuism then fashionable at court and amongst the higher ranks of society. An appearance of mystery was connected with his person. His birthplace and condition were not generally divulged, and though of an open and gallant bearing, yet on this head he was not very communicative. Mystery begets wonder and excitement—a sort of interest usually attached to subjects not easily understood. When it emanates from an object capable of enthralling the affections, this feeling soon kindles admiration, and admiration ripens into love. No wonder, then, if all tender and compassionate dames were ready to open upon him their dread artillery of sighs and glances, and the more especially as it soon began to be manifest that success was nigh hopeless. The heart entrenched, the wearer was impenetrable.

Kate's oddly-assorted brain had not failed to run a-rambling at times after the gallant stranger. He had heard much of her beauty, and likewise of her uncertain humours. Each fancied the opposite party impregnable; and this alone, if none other motive had arisen, formed a sufficiently strong temptation to begin the attack. Kate was particularly punctual at church, and once or twice he caught an equivocating glance towards the warden's seat, and he really did at times fancy he should like to play at "taming the shrew." Kate was sure the stranger slighted her. He treated her, and her only, with an air of neglect she could not altogether account for, and she was in month's mind to make the young cavalier crouch at her feet. How this was to be contrived could only be guessed at by a woman, and we will not let the reader into all the secrets of Kate's sanctuary. Suffice it to say, that in so harmlessly attempting to beguile her prey into the snare, the lady fell over head and ears into it herself. In a word Kate was in love! And this was the more grievous, inasmuch as her lofty bearing hitherto would not allow her to whisper the matter even to her own bosom; and the pent-up and smothering flame was making sad havoc with poor Kate's repose.

She had ofttimes suspected the state of her heart; but instead of sighing, pining, and twanging her guitar to love-sick ditties, she would fly into so violent a rage at her own folly that nothing might quell the disturbance until fairly worn out by its own vehemency. No one suspected the truth—yes, one forsooth—gentle reader, canst thou guess? It was no less a personage than our one-shouldered friend Timothy Dodge! How the cunning rogue had contrived to get at the secret is more than we dare tell. Sure enough he had it; and as certain too that another should be privy to the fact—to wit, Edward Kelly the seer. Dodge was a fitting tool for this intriguer, and well able to help him out at a pinch.

Affairs were in this position when our story commenced. Rodolf had formidable auxiliaries at hand, had he been disposed to make the attack; but his stay was now short—Kate was petulant and perverse—the siege might be tedious. Just on the verge of relinquishing he met Kate, as we have before seen, going to church. He caught her for the once completely off her guard, and the rich blush that ensued set a crowd of odd fancies jingling through his brain. It was just as the old chimes were ringing their doleful chant from the steeple, but these hindered not a whit the other changes that were set agoing. Not aware of the alteration in his course, he was much amazed when he found himself striding somewhat irreverently down the great aisle of the church, towards the choir, from whence the low chanting of the psalms announced that service was already begun.

It was the opening of a bright autumnal day. The softened lights streamed playfully athwart the grim and shadowy masses that lay on the chequered pavement, like the smiles of infancy sporting on the dark bosom of the tomb. The screen formed a rich foreground, in half-shadow, before the east window. The first beam of the morning, clothed in tenfold brightness, burst through the variegated tracery. Prophets, saints, and martyrs shone there, gloriously portrayed in heaven's own light.

Rodolf approached the small door leading into the choir, when his vacant eye almost unconsciously alighted on a female form kneeling just within the recess.

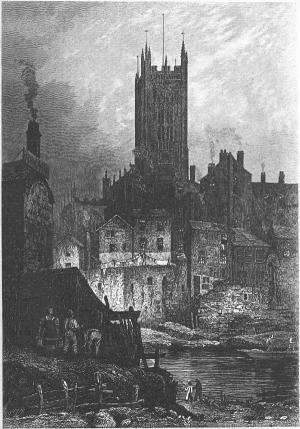

COLLEGIATE CHURCH, MANCHESTER.

Drawn by G. Pickering. Engraved by Edward Finden.

A ray, from her patron saint belike, darting through the eastern oriel, came full upon her dark and glowing eye. She turned towards the stranger, but in a moment her head was bent as lowly as before, and the ray had lost its power. Rodolf suddenly retreated. Passing through a side door, he left the church, directing his steps towards the low and dark corridors of the college. Near the entrance to his chamber, on a narrow bench, sate a well-caparisoned page tuning his lute. His attire was costly, and his raiment all redolent with the most fragrant perfume. This youth, when very young, was sent over as the companion, or rather at that time as the playmate of his master. He was now dignified with the honourable title of page, and his affection for Rodolf was unbounded.

"Boy," said the cavalier, something moodily, "come into the chamber. Stay—fetch me a sack-posset, prythee. I am oppressed, and weary with my morning's ramble."

Now the boy did marvel much at his master's sudden return, but more especially at the great fatigue consequent on that short interval;—knowing, too, that a particularly copious and substantial breakfast had anticipated his departure.

"And yet, Altdorff, I am not in a mood for much drink. Give us a touch of those chords. I feel sad at times, and vapourish."

They entered into a well-furnished apartment. The ceiling was composed of cross-beams curiously wrought. On one of these was represented a grim head in the act of devouring a child—which tradition affirmed was the great giant Tarquin at his morning's repast. The room was fitted up with cumbrous elegance. A few pieces of faded tapestry covered one side of the apartment. In a recess stood a tester bed, ornamented with black velvet, together with curtains of black stuff and a figured coverlet. A wainscot cupboard displayed its curiously-carved doors, near to which hung two pictures, or tables as they were called, representing the fair Lucretia and Mary Magdalen. A backgammon-board lay on the window-seat; three shining tall-backed, oaken chairs, with a table of the same well-wrought material, and irons beautifully embossed, and a striped Turkey rug, formed a sumptuous catalogue, when we consider the manner of furnishing that generally prevailed in those days.

The page sat on a corner seat beneath the window. He struck a few wild chords.

"Not that—not that, good Altdorff. It bids one linger too much of home-longings."

Here the boy's eyes glistened, and a tremulous motion of the lip showed how his heart bounded at the word.

"Prythee, give us the song thou wast conning yesterday."

The page began with a low prelude, but was again interrupted.

"Nay, 'tis not thus. Give me that wild love-ditty thou knowest so well. I did use to bid thee be silent when thou wouldest have worried mine ears with it. But in sooth the morning looks so languishing and tender that it constrains the bosom, I verily think, to its own softness."

The page seemed to throw his whole soul into the wild melody which followed this request. We give it, with a few verbal alterations, as follows:—

SONG.

1.

Fair star, that beamest

In my ladye's bower,

Pale ray, that streamest

In her lonely tower;

Bright cloud, when like the eye of Heaven

Floating in depths of azure light,

Let me but on her beauty gaze

Like ye unchidden. Day and night

I'd watch, till no intruding rays

Should bless my sight.

2.

Fond breeze, that rovest

Where my ladye strays,

Odours thou lovest

Wafting to her praise;

Lone brook, that with soft music bubblest,

Chaining her soul to harmony;

Let me but round her presence steal

Like ye unseen, a breath I'd be,

Content none other joy to feel

Than circling thee!

"In good sooth, thou canst govern the cadence well. Thou hast more skill of love than thine age befits. But, mayhap, 'tis thy vocation, boy. Hast thou had visitors betimes this morning!"

"None, good master, but Kelly."

"What of him?"

"Some business that waited your return. I thought you had knowledge of the matter."

"Are there any clients astir so early at his chamber, thinkest thou?"

"None, save the rich merchant that dwells hard by, Cornelius Ethelstoun."

"Cornelius!" repeated the cavalier, in a disturbed and inquiring tone—"hath he departed?"

"Nay, I heard not his footsteps since I watched the old man tapping warily at the prophet's door."

Rodolf hastily replaced his hat, and his short and impatient rap was heard at the seer's chamber.

It occupied the north-eastern angle of the building, in the gloomiest part of the house; overlooking, on one side, a small courtyard, barricadoed by walls and battlements of stout masonry, along which were ridges of long rank grass waving in all the pride of uncropped luxuriance. Another window overlooked the dark-flowing Irk, lazily rolling beneath the perpendicular rock on which the college was built—the very site of the once formidable station of Mancunium, the heart and centre of the Roman power in that vast district.

No answer being rendered to this hasty summons, Rodolf raised the latch, but marvelled not a little when he beheld the room apparently deserted. Voices were, however, heard in the inner apartment. Ere he could well draw back the door slowly opened, nor could he avoid hearing the following termination to some weighty conference.

"An hundred broad pieces—good! Ere night, thou sayest?"

"Ere the curfew," replied Cornelius.

"Look thee—'tis but a slender space for mine art to work, and"—The seer, as he uttered this with great solemnity, entered the antechamber. The gallant stood there, just meditating a retreat. A flush of anger and confusion passed for a moment over Kelly's visage. Quickly recovering his self-possession, with a severe aspect, he stood before the intruder.

"Art come to listen or to watch?" abruptly interrogated the seer. "Both be rare accomplishments truly for a youth of thy breeding."

"Nay, good Master Kelly; I came but at thy bidding, and mine ears are not the heavier or the wiser for what they have heard, I trow."

"I thought thee safe at morning prayers."

"Nay," replied Rodolf. "There be too many bright eyes and blushing cheeks for the seasoning of a man's devotions."

"Cornelius, thou mayest retire. What mine art can compass shall not be lacking at thy need."

The merchant, with a profound obeisance, withdrew. The seer adjusted his beard, carefully brushed the down from his velvet cap, and sate for a while as if abstracted from all outward intercourse. His keen quick eye became fixed, its lustre imperceptibly waning. A cloud seemed to pass gradually over his sharp features, until their expression was absorbed, giving place to a look of mere lifeless inanity. A spectator might have fancied himself gazing at a sage of some remote era, conjured up from his dark resting-place. The wand of death seemed to have withered his shrunk visage for ages under the dim shadow of the grave.

Rodolf, aware that he was not to be interrupted when the gift was upon him, waited patiently the result of the seer's revelations. A considerable time had elapsed when the cloud began to roll away. His features gradually reassumed the attributes of life, as each separately felt the returning animation. His eyes rested full on the cavalier.

"I have had a vision, Rodolf."

"To me is it not spoken?" inquired he.

"Yea, to thee!" The seer said this in a tone so hollow and energetic, and with a look of such thrilling awe, that even Rodolf shuddered. He seemed to feel his glance.

"Listen. The spirit warned me thus:—

"'The stranger that hither comes o'er the broad

sea

Shall wed on the night of St Bartlemy.'"

"Nay, Master Kelly, thine art faileth this once, forsooth. To-night is the saint's vigil, yet lurk I not in the beam of a woman's favour; and ere another year I may be cured of the simples at my father's dwelling in the old castle."

"The vision hath spoken, and it setteth not forth idle tales. Come to me anon, I will anoint and prepare my beryl and my divining mirror. Thou shall thyself behold some of the mysteries touching which I have warned thee beforetime. About noon return to my chamber."

Rodolf withdrew into his own apartment. His countenance looked anxious and disturbed. He sat down, but his restless ness seemed to increase. His posture was not the most easy and graceful that might be desired, nor calculated to set off his personal advantages, though now become the more needful, if, as the seer predicted, he should wive ere night—albeit his bride were yet unsought—nor wooed, nor won! Nothing could be more destructive to that easy self-satisfaction, that seductive and insinuating carriage, so essential to the fine gentleman of every age. There was a sort of angular irregularity in his movements, neither pleasant nor becoming; and his agitation so far overcame his better breeding that he really did cram his beard between at least three of his fingers. His rapier had, moreover, poked its way through his cloak, and the bright shoe-roses were nigh ruined, from the sudden crossings and disarrangements they had undergone. A considerable time had now elapsed; in the meanwhile his impatience had risen to an alarming height, insomuch that we would not have answered for the safety of his red cloth hose and silken doublet, had not noon been happily announced.

Raising the latch of the seer's chamber with considerable eagerness, he found the room completely dark. An unseen hand led him to a seat. Soon he heard a low murmuring chant, as though from voices at a remote distance. By degrees the words grew more articulate, shaping themselves into the same quaint distich that Kelly had repeated,—

"The stranger that hither comes o'er the broad

sea

Shall wed on the night of St Bartlemy."

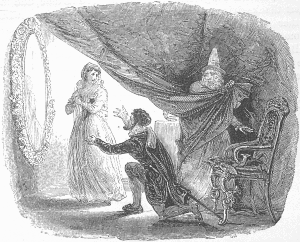

This was answered in a voice of considerable pathos; a burst of soft music filling up the interval. Gradually the eye began to feel sensible of the presence of surrounding objects, though in the ordinary way nothing could be distinguished; a faculty peculiarly sensitive with the loss of sight, and not quite dormant in the general mass of mankind. A faint gleam was soon perceptible, like the first blush of morning, apparently on the opposite side of the chamber. Becoming brighter, flashes of a dim, rainbow-coloured light crept slowly by, like the aurora sweeping over an illuminated cloud. Suddenly he saw, or his eyes deceived him, a female form shaping itself from these chaotic elements. But it was observed only during the short intervals when the beams seemed to kindle with unusual brightness. Every flash, however, rendered the appearance more distinct. Dazzled and bewildered, the heated senses were become the victims of their own credulity, the mind receiving back its own reactions. Taking its impression probably from the occurrences of the morning, the eye rapidly moulded the figure into the likeness of Kate. Her eyes were turned upon him, beaming with that soft and melting expression he had so recently beheld. It was but momentary, or he could have persuaded himself that she looked on him with an air the most tender and compassionate. Never did fancy portray her in a form so lovely. Deep and indelible was the impression; and though it might be

"The imagination

Become impregnate with her own desire,"

yet she had performed her office well. Not all the realities, all the blandishments that woman ever displayed, even the most resistless, could have wrought half so dexterously or gained such swift access to the heart. The vision faded, and a momentary darkness ensued. Suddenly a blaze of light irradiated the apartment. Rodolf beheld, for one short glimpse, a Gothic hall. Kate was there, and a lover kneeling at her feet. Madness seized him, agonising and intense. In vain he sought the features of his tormentor; the vision had departed, and with it his repose.

A new and overwhelming emotion had overpowered him. It arose with the speed and impetuosity of a whirlwind. All just and sober anticipations, reflections, possibilities, and a thousand calm resolves, were swept as bubbles before the full burst of the torrent.

His first impulse was to seek his mistress. But—she had another lover! The bare possibility of this event came o'er his bosom like the icy chill of the grave. He shuddered as it passed; but the pang was too keen to return with the same intensity.

Soon a low murmur, like the distant sough of the wind, gradually approached. A faint light flashed through the chamber. He saw his own wild woods and the distant castle. It was just visible, dimly outlined on the horizon, as he had last beheld it in the cold grey beam that accompanied his departure. It arose tranquilly on his spirit. The voice of other years visited his soul. His eyes filled—he could have wept in the very overflowing of his delight. He dashed his hand across his forehead; but the pageant had disappeared.

Daylight once more shone into the apartment; but nothing was discerned, save a dark curtain concealing one extremity of the room, and the seer sitting at his elbow.

"Boy, what sawest thou?" said Kelly, not raising his head as he spoke, but intently poring over a grim volume of cabalistic symbols.

"In troth, I am hard put to it, Master Kelly. The maid I have just seen is accounted the veriest shrew in the parish, and one whom no man may approach with a safe warranty. I am like to lose all hope of wiving, if this be the maiden I am to woo. And yet"—The form of the comely suitor he had seen kneeling at her feet just then flashed on his mind, yet cared he not to show the seer how much the phantom had disturbed him.

"Idle tales?" said Kelly. "I wot not but half the gay gallants in the town would give the best jewel in their caps to have one sweet look, one pretty smile from her cruel mouth. 'Tis but the report of those whom she hath slighted with loathing and contempt, that hath raised this apprehension in her disfavour. The churls know not what is hidden beneath this outward habit of her perverse nature, and she careth not to discover. Should some youth of noble bearing and condition but woo her as she deserves, thou shouldest see her tamed, ay, and loving too, as the very idol of her worship, or I would forfeit my best gift."

"But she hath a lover!" said Rodolf, gravely.

"Peradventure she hath, but not of her own choosing, or mine art fails me. Look, this figure is the horoscope of her birth. Thou hast some knowledge of the celestial sciences. The directions are so close worked that should this night pass and Kate go unwed—indicated by Venus coming to a trine of the sun on the cusp of the seventh house, she will refuse all her suitors, and her whole patrimony pass into the hands of a stranger; but"—he raised his voice with a solemn and emphatic enunciation—"to-night! look to it! If not thine she may be another's."

The listener's brain seemed on a whirl; thought hurrying on thought, until the mind lost all power of discrimination. The succession of images was too rapid. All individuality was gone. He felt as though not one idea was left out of the busy crowd on which to rest his own identity. He seemed a mere passive existence, unable either to execute the functions of thought or volition.

"Go, for a brief space. Thou mayest return at sunset. Yet"—the seer fixed a penetrating glance on the youth as he retired—"go not nigh the merchant's dwelling, unless thou wouldest mar thy fortune. To-night—remember!"

In the dim solitude of his chamber Rodolf sought in vain to allay the feverish excitement he had endured. He seemed left to the sport and caprice of a power he could not control. The coursers of the imagination grew wilder with restraint: he recklessly flung the reins upon their neck; but this did not tire their impetuosity. His brain glowed like a furnace; he seemed hastening fast on to the verge of either folly or madness. He threw himself on the couch, when the voice of Altdorff came like a winged harmony upon his spirit. The page was seated in the narrow cloisters,—the lute, his untiring companion, enticing a few chords from his touch, playful and gentle as the feelings that awaked them; some old and quaint chant, scarce worth the telling, but cherished in the heart's inmost shrine, from the hallowed nature of its associations. A deep slumber crept heavily on the cavalier, but the merchant's daughter still haunted him: sometimes snatched away from his embrace just as a rosy smile was kindling on her lips; at others, she met him with frowns and menace, but ere he could speak to her she had disappeared. Then was he tottering on the battlements of some old turret, when a storm arose, the maiden crept to his side, but in an instant, with a hideous crash, she was borne away by the rude grasp of the tempest. He awoke, with a mortifying discovery that the crash had been of a somewhat less equivocal nature. A cabinet of costly workmanship lay overturned at his feet, and a rich vase, breathing odours, strewed the floor in a thousand fragments.

The noise brought up several of the college servitors; to rid himself from the annoyance he ascended the roof, then protected by low battlements, and leaded, so that a person might walk round the building and pursue his meditations without interruption.

On this day, teeming with events, Dr Dee had been too closely engaged in parish duties to give heed to these love fancies, and even had he been ever so free to exercise his judgment in the matter, it is more than likely Rodolf would not have opened to him the proceedings then afoot. He well knew that the Doctor yet bore no good-will to Kelly, and might possibly thwart his designs, to the undoing of any good purposed by the strange transactions that had already occurred; he resolved, therefore, to let this day pass, ere he opened his lips on the subject. But how to while away the hours until evening was a most embarrassing problem. Sleep he had tried, but he found no wish to repeat the experiment; reading was just then foreign to his humour; mathematics must, that day, go unstudied. After beating time to at least a dozen strange metres, he hit upon the happy contrivance of writing a love-song, as a kind of expedient to restore the equilibrium. He was rather unskilled at the work; but the pen becomes eloquent when the soul moves it. We will, however, leave him at this thrifty employment, having no design, gentle reader, to make the occasion as wearisome to thee as to himself. Having the power to annihilate both time and space, let us watch the round sun, as he threw his last look, that evening, on the scene of this marvellous history. The old walls of the college, and the church tower, were invested with a gorgeous apparel of light, as though illumined for some gay festival, some season of rejoicing, when gladness shines out visibly in the shape of bonfires and torches. But few moments elapsed, ere the love-sick youth was again admitted into the dark interior of the seer's dwelling.

A voice whispered in his ear—

"Not a word, hardly a breath, as thou wouldest thrive in thy pursuit. There be spirits abroad, not of earth, nor air. Be silent and discreet."

A ray suddenly darted across the room. Again the voice was at his ear:—

"Hold thine eye to the crevice when the light enters, and mark well what thou beholdest."

Again he saw his mistress, apparently in a vaulted chamber, lighted by a single lamp: she sat as if anxious and disturbed, her cheek pale and flushed by turns, whilst her eye wandered hurriedly around the room. Some one approached; it was the seer. Rodolf heard him speak.

"Maiden, hast thou a lover?"

The sound seemed scarcely akin to that of human speech. It rose heavily and deep, as from the charnel-house, as if the grim and cold jaws of the grave could utter a voice,—the dreary echoes of the tomb! The seer's lips were motionless, whilst he thus continued in the same sepulchral tone.

"I know thou hast. 'Tis here thy love would tend." He drew a richly-set miniature from his bosom. It was mounted in so peculiar a fashion that Rodolf started back with the first emotion of surprise. The miniature was his own; a gem newly from the artist, and which he had left, as he thought, in safe custody a short time ago. The voice again whispered in his ear, "Beware."

He subdued the expression of wonder just rising on his lip, watching the issue with increased interest.

Kate covered her face. She had just glanced at the picture, and her proud bosom heaved almost to bursting.

"Look, disdainful woman! and though thy bosom be formed for love, yet wouldest thou spurn it from thee. I know thou lovest him. Nay, chide not; thy brow cannot blast me with its thunders. Go to. I could, by mine art, so humble thee, set thy love so exquisitely on its desire, that thou shouldest lay thy proud womanhood aside—sue and crouch, even if 'twere for blows, like a tame spaniel! I have thee in my power, and were not the natural bent of thy dispositions kind and noblehearted, yet sore beset, and, as it were, overwhelmed by thy curst humours, I had now cast my spells about thee—ay, stricken thee to the dust! Shake off these bonds that enthral thy better spirit, and let not that beautiful fabric play the hypocrite any longer. Why should so fair a temple be the dwelling of a demon?"

A deep sob here told that kindlier feelings were at work; that nature was beginning to assert her prerogative, and that the common sympathies, the tender attributes, of woman were not extinguished.

The struggle was short, but severe. With difficulty she repressed the outburst of her grief as she spoke.

"A woman still! 'Tis the garb nature put on. I have wrapped a sterner garment about me." A long and bitter sob here betrayed the violent warfare within. It was but for a moment. Affecting contempt for her own weakness, she exclaimed—

"Throw it off? Expose me defenceless to his proud contumely? Even now the cold glance of indifference hath pierced it through!"

Here she arose proudly.

"And what thinkest thou, if I were to stand unarmed, uncovered, before his unfeeling gaze?"

"He loves thee," hastily rejoined the seer.

"Me!—as soon that bauble learn to love as"——

"Say but one word, and I will bow him at thy feet."

"'Tis well thou mockest me thus. To worm out my secret, perchance.—For this didst thou crave my presence? Let me be gone!"

"Thou shalt say 'Yes,' Kate, ere thou depart!"

The curtain which divided the apartment suddenly flew aside. The astonished lover beheld his mistress:—not the unreal phantom he had imagined, but a being substantial in quality, and of a nature like his own, though gentler than his fondest anticipations.

The seer departed: but in the end the lovers were not displeased at being betrayed into a mutual expression of their regard.

The operation of the heavenly influences was, in these days, a doctrine that obtained almost universal credit; and it would have been looked upon as a daring piece of presumption to baffle the prophetic signification of the stars.

On that same night, being the eve of St Bartholomew, they were married:—thus adding one more to the numerous instances on record, where a belief in the prediction has been the means of its accomplishment.

The remainder of Kate's history, and how she crossed the sea, accompanied by her husband, into the wilds of Bohemia, living there for a space; and how she afterwards returned into her own land, will be set forth at some more fitting opportunity.

Index | Next: The Earl Of Tyrone