|

|

Iranian Mythology by Albert j. Carnoy

AUTHOR'S PREFACE

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER I. WARS OF GODS AND DEMONS

CHAPTER II. MYTHS OF CREATION

CHAPTER III. THE PRIMEVAL HEROES

CHAPTER IV. LEGENDS OF YIMA

CHAPTER V. TRADITIONS OF THE KINGS AND

ZOROASTER

CHAPTER VI. THE LIFE TO COME

CHAPTER VII. CONCLUSION

AUTHOR'S PREFACE

THE purpose of this essay on Iranian mythology is exactly set forth by its title : it is a reasonably complete account of what is mythological in Iranian traditions, but it is nothing more; since it is exclusively concerned with myths, all that is properly religious, historical, or archaeological has intentionally been omitted. This is, indeed, the first attempt of its kind, for although there are several excellent delineations of Iranian customs and of Zoroastrian beliefs, they mention the myths only secondarily and because they have a bearing on those customs and beliefs. The consequent inconveniences for the student of mythology, in the strict sense of the term, are obvious, and his difficulties are increased by the fact that, with few exceptions, these studies are either concerned with the religious history of Iran and for the most part refer solely to the older period, or are devoted to Persian literature and give only brief allusions to Mazdean times.

Though we must congratulate the Warners for their illuminating prefaces to the various chapters of their translation of the Shdhndmah, it is evident that too little has thus far been done to connect the Persian epic with Avestic myths.

None the less, the value and the interest presented by a study of Iranian mythology is of high degree, not merely from a specialist's point of view for knowledge of Persian civilization and mentality, but also for the material which it provides for mythologists in general. Nowhere else can we so clearly follow the myths in their gradual evolution toward legend and traditional history. We may often trace the same stories from the period of living and creative mythology in the Vedas through the Avestic times of crystallized and systematized myths to the theological and mystic accounts of the Pahlavi books, and finally to the epico-historic legends of Firdausi.

There is no doubt that such was the general movement in the development of the historic stories of Iran. Has the evolution sometimes operated in the reverse direction? Dr. L. H. Gray, who knows much about Iranian mythology, seems to think so in connexion with the myth of Yima, for in his article on "Blest, Abode of the (Persian)," in the Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics, ii. 702-04 (Edinburgh, 1909), he presents an interesting hypothesis by which Yima's successive openings of the world to cultivation would appear to allude to Aryan migrations. It has seemed to me that this story has, rather, a mythical character, in conformity with my interpretation of Yima's personality; but in any event a single case would not alter our general conclusions regarding the course of the evolution of mythology in Persia.

Another point of interest presented by Iranian mythology is that it collects and unites into a coherent system legends from two sources which are intimately connected with the two great racial elements of our civilization. The Aryan myths of the Vedas appear in Iran, but are greatly modified by the influence of the neighbouring populations of the valleys of the Tigris and the Euphrates Sumerians, Assyrians, etc.

Occasional comparisons of Persian stories with Vedic myths or Babylonian legends have accordingly been introduced into the account of Iranian mythology to draw the reader's attention to curious coincidences which, in our present state of knowledge, have not yet received any satisfactory explanation.

In a paper read this year before the American Oriental Society I have sought to carry out this method of comparison in more systematic fashion, but studies of such a type find no place in the present treatise, which is strictly documentary and presen tational in character. The use of hypotheses has, therefore, been carefully restricted to what was absolutely required to present a consistent and rational account of the myths and to permit them to be classified according to their probable nature. Due emphasis has also been laid upon the great number of replicas of the same fundamental story. Throughout my work my personal views are naturally implied, but I have sought to avoid bold and hazardous hypotheses.

It has been my endeavour not merely to assemble the myths of Iran into a consistent account, but also to give a readable form to my expose, although I fear that Iranian mythology is often so dry that many a passage will seem rather insipid. If this impression is perhaps relieved in many places, that happy result is largely due to the poetic colouring of Darmesteter's translation of the Avesta and of the Warners version of the Shdhndmah.

The editor of the series has also employed his talent in versifying such of my quotations from the Avesta as are in poetry in the original.

In so doing he has, of course, adhered to the metre in which these portions of the Avesta are written, and which is familiar to English readers as being that of Longfellow's Hiawatha, as it is also that of the Finnish Kalevala. Where prose is mixed with verse in these passages Dr. Gray has reproduced the original commingling. While, however, I am thus indebted to him as well as to Darmesteter, Mills, Bartholomae, West, and the Warners for their meritorious translations, these versions have been compared in all necessary cases with the original texts.

My hearty gratitude is due to Professor A. V. Williams Jackson, who placed the library of the Indo-Iranian Seminar at Columbia University at my disposal and gave me negatives of photographs taken by him in Persia and used in his Persia Past and Present.

It is this hospitality and that of the University of Pennsylvania which have made it possible for me to pursue my researches after the destruction of my library in Louvain. Dr. Charles J. Ogden of New York City also helped me in many ways. For the colour-plates I am indebted to the courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, where the Persian manuscripts of the Shdhndmah were generously placed at my service; and the Open Court Publishing Company of Chicago has permitted the reproduction of four illustrations from their issue of The Mysteries of Mithra.

A. J. CARNOY. UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA, I November, 1916.

INTRODUCTION

TECHNOLOGICALLY the Persians are closely akin to the Aryan races of India, and their religion, which shows many points of contact with that of the Vedic Indians, was dominant in Persia until the Muhammadan conquest of Iran in the seventh century of our era. One of the most exalted and the most inter esting religions of the ancient world, it has been for thirteen hundred years practically an exile from the land of its birth, but it has found a home in India, where it is professed by the relatively small but highly influential community of Parsis, who, as their name ("Persians") implies, are descendants of immigrants from Persia.

The Iranian faith is known to us both from the inscriptions of the Achaemenian kings (558-330 B.C.) and from the Avesta, the latter being an extensive collection of hymns, discourses, precepts for the religious life, and the like, the oldest portions dating back to a very early period, prior to the dominion of the great kings. The other parts are consider ably later and are even held by several scholars to have been written after the beginning of the Christian era. In the period of the Sassanians, who reigned from about 226 to 641 A.D., many translations of the Avesta and commentaries on it were made, the language employed in them being not Avesta (which is closely related to the Vedic Sanskrit tongue of India), but Pahlavi, a more recent dialect of Iranian and the older form of Modern Persian.

A large number of traditions concerning the Iranian gods and heroes have been preserved only in Pahlavi, es pecially in the Bundahish, or "Book of Creation." Moreover the huge epic in Modern Persian, written by the great poet Firdausi, who died about 1025 A.D., and known under the name of Shahndmah, or "Book of the Kings," has likewise rescued a great body of traditions and legends which would otherwise have passed into oblivion; and though in the epic these affect a more historical guise, in reality they are generally nothing but humanized myths.

This is not the place to give an account of the ancient Persian religion, since here we have to deal with mythology only. It will suffice, therefore, to recall that for the great kings as well as for the priests, who were followers of Zoroaster (A vesta Zarathushtra), the great prophet of Iran, no god can be compared with Ahura Mazda, the wise creator of all good beings. Under him are the Amesha Spentas, or "Immortal Holy Ones," and the Yazatas, or "Venerable Ones," who are secondary deities. The Amesha Spentas have two aspects. In the moral sphere they embody the essential attainments of religious life: "Righteousness" (Asha or Arta), "Good Mind" (Vohu Manah), "Desirable Kingdom" (Khshathra Vairya), "Wise Conduct" and "Devotion" (Spenta Armaiti), "Perfect Happiness" (Haurvatat), and "Immortality" (Ameretat).

In their material nature they preside over the whole world as guardians: Asha is the spirit of fire, Vohu Manah is the protector of domestic animals, Khshathra Vairya is the patron of metals, Spenta Armaiti presides over earth, Haurvatat over water, and Ameretat over plants.

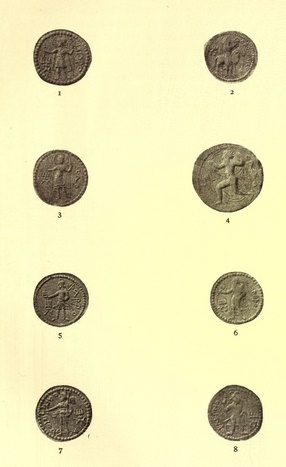

PLATE XXXII: IRANIAN DEITIES ON INDO-SCYTHIAN COINS

i. MITHRA

The Iranian god of light with the solar disk about his head. From

a coin of the Indo-Scythian king Huviska. After Stein,

Zoroastrian Deities on Indo-Scythian Coins, No. I. See pp.

287-88.

2. APAM NAPAT

The "Child of Waters." The deity is represented with a horse,

thus recalling his Avestic epithet, aurvat-aspa ("with swift

steeds"). From a coin of the Indo-Scythian king Kaniska. After

Stein, Zoroastrian Deities on Indo-Scytkian Coins, No. III. See

pp. 267, 340.

3 MAH

The moon-god is represented with the characteristic lunar disk.

From a coin of the Indo-Scythian king Huviska. After Stein,

Zoroastrian Deities on Indo-Scythian Coins, No. IV. See p.

278.

4. VATA OR VAYU

The wind-god is running forward with hair floating and mantle

flying in the breeze. From a coin of the Indo-Scythian king

Kaniska. After Stein, Zoroastrian Deities on Indo-Scythian Coins,

No. V. See pp. 299, 302.

5. KHVARENANH

The Glory, here called by his Persian name, Farro, holds out the

royal symbol. From a coin of the Indo-Scythian king Huviska.

After Stein, Zoroastrian Deities on Indo-Scythian Coins, No. VI.

See pp. 285, 304-05, 311, 324, 332-33, 343.

6. ATAR

The god of fire is here characterized by the flames which rise

from his shoulders. From a coin of the Indo-Scythian king

Kaniska. After Stein, Zoroastrian Deities on Indo-Scythian Coins,

No. VII. See pp. 266-67.

7. VANAINTI (U PAR AT AT)

This goddess, "Conquering Superiority," is modelled on the Greek

Nike ("Victory"), and seems to carry in one hand the sceptre of

royalty, while with the other she proffers the crown worn by the

Iranian kings. From a coin of the Indo-Scythian king Huviska.

After Stein, Zoroastrian Deities on Indo-Scythian Coins, No.

VIII.

8. VERETHRAGHNA

On the helmet of the war-god perches a bird which is doubt less

the Vareghna. The deity appropriately carries spear and sword.

From a coin of the Indo-Scythian king Kaniska. After Stein,

Zoroastrian Deities on Indo-Scythian Coins, No. IX.

The Amesha Spentas constitute Ahura Mazda's court, and it is through them that he governs the world and brings men to sanctity. Below Ahura Mazda and the Amesha Spentas come the Yazatas, who are for the most part ancient Aryan divinities reduced in the Zoroastrian system to the rank of auxiliary angels. Of these we may mention Atar, the personification of that fire which plays so important a part in the Mazdean cult that its members have now become commonly, though quite erroneously, known as "Fire-Worshippers"; and by the side of the genius of fire is found one of water, Anahita.

Mithra is by all odds the most important Yazata. Although pushed by Zoroaster into the background, he always enjoyed a very popular cult among the people in Persia as the god of the plighted word, the protector of justice, and the deity who gives victory in battle against the foes of the Iranians and defends the worshippers of Truth and Righteousness (Asha). His cult spread, as is well known, at a later period into the Roman Empire, and he has as his satellites, to help him in his function of guardian of Law, Rashnu ("Justice") and Sraosha ("Discipline").

Under the gods are the spirits called Fravashis, who originally were the manes of ancestors, but in the Zoroastrian creed are genii, attached as guardians to all beings human and divine.

It is generally known that the typical feature of Mazdeism is dualism, or the doctrine of two creators and two creations. Ahura Mazda (Ormazd), with his host of Amesha Spentas and Yazatas, presides over the good creation and wages an incessant war against his counterpart Angra Mainyu (Ahriman) and the latter's army of noxious spirits.

The Principle of Evil has created darkness, suffering, and sins of all kinds; he is anxious to hurt the creatures of the good creation; he longs to enslave the faithful of Ahura Mazda by bringing them into falsehood or into some impure contact with an evil being; he is often called Druj ("Deception"). Under him are marshalled the daevas ("demons "), from six of whom a group has been formed explicitly antithetic to the Amesha Spentas. Among the demons are Aeshma ("Wrath, Violence"), Aka Manah ("Evil Mind"), Bushyasta ("Sloth"), Apaosha ("Drought"), and Nasu ("Corpse"), who takes hold of corpses and makes them impure, to say nothing of the Yatus ("sorcerers") and the Pairikas (Modern Persian pan, "fairy"), who are spirits of seduction. The struggle between the good and the evil beings, in which man takes part by siding, according to his conduct, with Ahura Mazda or with his foe, is to end with the victory of the former at the great renovation of the world, when a flood of molten metal will, as an ordeal, purify all men and bring about the complete exclusion of evil.

Dualism, having impregnated all Iranian beliefs, profoundly influenced the mythology of Iran as well or, more exactly, it was in their mythology that the people of ancient Persia found the germ that developed into religious dualism.

CHAPTER I. WARS OF GODS AND DEMONS

THE mythology of the Indians and the Iranians has given a wide extension to the conception of a struggle between light and darkness, this being the development of myths dating back to Indo-European times and found among all Indo- European peoples. Besides the cosmogonic stories in which monstrous giants are killed by the gods of sky or storm we have the myths of the storm and of the fire. In the former a heavenly being slays the dragon concealed in the cloud, whose waters now flow over the earth; or the god delivers from a monster the cows of the clouds that are imprisoned in some mountain or cavern, as, for example, in the legends concerning Herakles and Geryoneus or Cacus. 1 In the second class of myths the fire of heaven, produced in the cloud or in an aerial sea, is brought to earth by a bird or by a daring human being like Prometheus.

All these myths tell of a struggle against powers of darkness for light or for blessings under the form of rain. They were eminently susceptible of being systematized in a dualistic form, and the strong tendency toward symbolism, observable both in old Indian (Vedic) and old Iranian conceptions, resulted in the association of moral ideas with the cosmic struggle, thus easily leading to dualism.

The recent discoveries in Boghaz Kyoi and elsewhere in the Near East have shown that the Indo-Iranians were in contact with Assyro-Babylonian culture at an early date, and there are many reasons for believing that their religious ideas were influenced by their neighbours, especially as regards the group of gods known in India as the Adityas, whose function is to be the guardians of the law (Sanskritrta Avesta asha) and of morality.2

Now, Babylonian mythology could only confirm the Indo-Iranians in their conceptions concerning the cosmic battle against maleficent forces or monstrous beings. Thus Assyro-Babylonian legends tell of the fight between Tiamat, a huge monster of forbidding aspect, embodying primeval chaos, and Marduk, a solar deity. As Professor Morris Jastrow suggests, 3 the myth is based upon the annual phenomenon witnessed in Babylonia when the whole valley is flooded, when storms sweep across the plains, and the sun is obscured. A conflict is going on between the waters and storms on the one hand, and the sun on the other; but the latter is finally victorious, for Marduk subdues Tiamat and triumphantly marches across the heavens from one end to the other as general overseer.

In other myths, more specifically those of the storm, the storm is represented by a bull, 4 an idea not far remote from the Indo-Iranian conception which identifies the storm-cloud with a cow or an ox. The storm-god is likewise symbolized under the form of a bird, a figure which we also find in Iranian myths, as when an eagle brings to the earth the fire of heaven, the lightning. Similarly in Babylonian mythology the bird Zu endeavours to capture the tablets of Fate from En-lil, and during the contest which takes place in heaven Zu seizes the tablets, which only Marduk can recover. Like the dragon who has hidden the cows, Zu dwells in an inaccessible recess in the mountains, and Ramman, the storm-god, is invoked to conquer him with his weapon, the thunderbolt. 5

TYPICAL REPRESENTATION OF MITHRA

Mithra is shown sacrificing the bull in the cave. Beneath the bull is the serpent, and the dog springs at the bull's throat, licking the blood which pours from the wound. The raven, the bird sacred to Mithra, is also present. On either side of the god stands a torch-bearer, symbolizing the rising and the setting sun respectively, and above them are the sun and the moon in their chariots. This Borghesi bas-relief in white marble, now in the Louvre, was originally in the Mithraeum of the Capitol at Rome. After Cumont, The Mysteries of Mithra, Fig. 4.

2. SCENES FROM THE LIFE OF MITHRA

This bas-relief, discovered in 1838 at Neuenheim, near Heidelberg, shows in the border, round the central figure of the tauroctonous deity, twelve of the principal events in his life. Among them the clearest are his birth from the rock (top of the border to the left), his capture of the bull, which he carries to the cave (border to the right), and his ascent to Ahura Mazda (top border). The second scene from the top on the border to the left represents Kronos (Zarvan, or "Time") investing Zeus (Ahura Mazda) with the sceptre of the universe. After Cumont, The Mysteries of Mitkra, Fig. 15.

Among the Indo-Iranians, the poetic imagination of the Vedic Indians has given the most complete description of the conflict in the storm-cloud. With his distinctive weapon, the vajra ("thunderbolt"), Indra slays the demon of drought called

Vrtra ("Obstruction") or Ahi ("Serpent"). The fight is terrible, so that heaven and earth tremble with fear. Indra is said to have slain the dragon lying on the mountain and to have released the waters (clouds); and owing to this victory Indra is frequently called Vrtrahan ("Slayer of Vrtra"). The Veda also knows of another storm-contest, very similar to this one and often assigned to Indra, although it properly belongs to Trita, the son of Aptya. This mighty hero is likewise the slayer of a dragon, the three-headed, six-eyed serpent Visvarupa. He released the cows which the monster was hiding in a cavern, and this cave is also a cloud, because in his fight Trita, whose weapon is again the thunderbolt, is said to be rescued by the winds. He lives in a secret abode in the sky and is the fire of heaven blowing from on high on the terres trial fire (agni), causing the flames to rise and sharpening them like a smelter in a furnace. 6 Trita has brought fire from heaven to earth and prepared the intoxicating draught of immortality, the soma that gives strength to Indra. 7

In Iran, Indra is practically excluded from the pantheon, being merely mentioned from time to time as a demon of Angra Mainyu. Trita, on the other hand, is known as a beneficent hero, one of the first priests who prepared haoma (the Indian soma), 8 the plant of life, and as such he is called the first healer, the wise, the strong "who drove back sickness to sickness, death to death." He asked for a source of remedies, and Ahura Mazda brought down the healing plants which by many myriads grew up all around the tree Gaokerena, or White Haoma. 9 Thus, under the name of Thrita (Sanskrit Trita) he is the giver of the beverage made from the juice of the marvellous plant that grows on the summits of mountains, just as Trita is in India10.

Under the appellation of Thraetaona, son of Athwya (Sanskrit Aptya), another preparer of haoma, 11 he smote the dragon Azhi Dahaka, three-jawed and triple-headed, six-eyed, with mighty strength, an imp of the spirit of deceit created by Angra Mainyu to slaughter Iranian settlements and to murder the faithful of Asha ("Justice"), the scene of the struggle being "the four-cornered Varena," a mythical, remote region. Like the storm-gods and the bringers of fire, Thraetaona sometimes reveals himself in the shape of a bird, a vulture, 12 and later we shall see how, under the name of Faridun, he becomes an im portant hero in the Persian epic. His mythical nature appears clearly if one compares the storm-stories in the Veda with those in the Avesta. All essential features are the same on both sides. The myth of a conflict between a god of light or storm and a dragon assumes many shapes in Iran, although in its general outlines it is unchanging. In Thraetaona's struggle the victor was, as we have seen, connected with fire. Now fire itself, under the name of Atar, son of Ahura Mazda, is represented as having been in combat with the dragon Azhi Dahaka:

"Fire, Ahura Mazda's offspring,

Then did hasten, hasten forward,

Thus within himself communing:

Let me seize that Glory unattainable.

But behind him hurtled onward

Azhi, blasphemies outpouring,

Triple-mouthed and evil-creeded:

Back! let this be told thee,

Fire, Ahura Mazda's offspring:

If thou holdest fast that thing unattainable,

Thee will I destroy entirely,

That thou shalt no more be gleaming

On the earth Mazda-created,

For protecting Asha's creatures.

Then Atar drew back his hands,

Anxious, for his life affrighted,

So much Azhi had alarmed him.

Then did hurtle, hurtle forward,

Triple-mouthed and evil-creeded,

Azhi, thus within him thinking:

Let me seize that Glory unattainable.

But behind him hastened onward

Fire, Ahura Mazda's offspring,

Speaking thus with words of meaning:

Hence! let this be told thee,

Azhi, triple-mouthed Dahaka:

If thou holdest fast that thing unattainable,

I shall sparkle up thy buttocks,

I shall gleam upon thy jaw, 13

That thou shalt no more be coming

On the earth Mazda-created,

For destroying Asha's creatures.

Then Azhi drew back his hands,

Anxious, for his life affrighted,

So much Atar had alarmed him.

Forth that Glory went up-swelling

To the ocean Vourukasha.

Straightway then the Child of Waters,

Swift of horses, seized upon him.

This doth the Child of Waters, swift of horses, desire:

Let me seize that Glory unattainable

To the bottom of deep ocean,

In the bottom of profound gulfs. " 14

Although much uncertainty reigns as to the localization of the sea Vourukasha and the nature of the "Son of the Waters" (Apam Napat), the prevalent opinion is that they are respectively the waters on high and the fire above, which is born from the clouds.

The A vesta's most poetical accounts of the contest on high are, however, not the descriptions of battles with Azhi Dahaka, but the vivid pictures of the victory of Tishtrya, the dog-star (Sirius), over Apaosha, the demon of drought. 15 Drought and the heat of summer were the great scourges in Iranian countries, and Sirius, the star of the dog-days, was supposed to bring the beneficent summer showers, whereas Apaosha, the evil demon, was said to have captured the waters, which had to be released by the god of the dog-star. Accordingly we find the faithful singing:

"Tishtrya the star we worship,

Full of brilliancy and glory,

Holding water's seed and mighty,

Tall and strong, afar off seeing,

Tall, in realms supernal working,

For whom yearn flocks and herds and men

When will Tishtrya be rising,

Full of brilliancy and glory?

When, Oh, when, will springs of water

Flow again, more strong than horses? " 16

Tishtrya listens to the prayer of the faithful, and being satis fied with the sacrifice and the libations, he descends to the sea Vourukasha in the shape of a white, beautiful horse, with golden ears and caparisoned in gold. But the demon Apaosha rushes down to meet him in the form of a dark horse, bald with bald ears, bald with a bald back, bald with a bald tail, a frightful horse. They meet together, hoof against hoof; they fight together for three days and nights. Then the demon Apaosha proves stronger than the bright and glorious Tishtrya and over comes him, and he drives him back a full mile from the sea Vourukasha. In deep distress the bright and glorious Tishtrya cries out:

"Woe to me, Ahura Mazda!

Bane for you, ye plants and waters !

Doomed the faith that worships Mazda!

Now men do not worship me with worship that speaks my name.

If men should worship me with worship that speaks my name, . .

.

For myself I'd then be gaining

Strength of horses ten in number,

Strength of camels ten in number,

Strength of oxen ten in number,

Strength of mountains ten in number,

Strength of navigable rivers ten in number." 17

Hearing his lament, the faithful offer a sacrifice to Tishtrya, and the bright and glorious one descends yet again to the sea Vourukasha in the guise of a white, beautiful horse, with golden ears and caparisoned in gold. Once more the demon Apaosha rushes down to meet him in the form of a dark horse, bald with bald ears. They meet together, they fight together at the time of noon. Then Tishtrya proves stronger than Apaosha and overcomes him, driving him far from the sea Vourukasha and shouting aloud-:

"Hail to me, Ahura Mazda!

Hail to you, ye plants and waters!

Hail the faith that worships Mazda!

Hail be unto you, ye countries!

Up now, O ye water-channels,

Go ye forth and stream unhindered

To the corn that hath the great grains,

To the grass that hath the small grains,

To corporeal creation." 18

Then Tishtrya goes to the sea Vourukasha and makes it boil up and down, causing it to stream up and over its shores, so that not only the shores of the sea, but its centre, are boil ing over. After this vapours rise up above Mount Ushindu that stands in the middle of the sea Vourukasha, and they push forward, forming clouds and following the south wind along the ways traversed by Haoma, the bestower of prosperity. Behind him rushes the mighty wind of Mazda, and the rain and the cloud and the hail, down to the villages, down to the fields, down to the seven regions of earth.

Not only does Tishtrya enter the contest as a horse, but he also appears as a bull, a disguise which reminds us of the Semitic myth in which the storm-god Zu fights under the shape of a bull, and which is an allusion to the violence of the storms and to the fertility which water brings to the world.

Finally Tishtrya is changed into a brilliant youth, and that is why he is invoked for wealth of male children. In this avatar he manifests himself

"With the body of a young man,

Fifteen years of age and shining,

Clear of eye, and tall, and sturdy,

Full of strength, and very skilful." 19

This rain-myth was later converted into a cosmic story, and Tishtrya's shower was supposed to have taken place in primeval times before the appearance of man on earth, in order to destroy the evil creatures produced by Angra Mainyu as a counterpart of Mazda's creation. Tishtrya's co-operators were Vohu Manah, the Amesha Spentas, and Haoma, and he produced rain during ten days and ten nights in each one of the three forms which he assumed an allusion to the dog-days that were supposed to be thirty in number. "Every single drop of that rain became as big as a bowl, and the water stood the height of a man over the whole of this earth; and the noxious creatures on the earth being all killed by the rain, went into the holes of the earth." Afterward the wind blew, and the water was all swept away and was brought out to the borders of the earth, and the sea Vourukasha ("Wide-Gulfed") arose from it. "The noxious creatures remained dead within the earth, and their venom and stench were mingled with the earth, and in order to carry that poison away from the earth Tishtar went down into the ocean in the form of a white horse with long hoofs," conquering Apaosha and causing the rivers to flow out. 20

In his function of collector and distributor of waters from the sea Vourukasha, Tishtrya is aided by a strange mythical being, called the three-legged ass. "It stands amid the wide-formed ocean, and its feet are three, eyes six, mouths nine, ears two, and horn one, body white, food spiritual, and it is righteous. And two of its six eyes are in the position of eyes, two on the top of the head, and two in the position of the hump; with the sharpness of those six eyes it overcomes and destroys. Of the nine mouths three are in the head, three in the hump, and three in the inner part of the flanks; and each mouth is about the size of a cottage, and it is itself as large as Mount Alvand [eleven thousand feet above the sea]. . . . When that ass shall hold its neck in the ocean its ears will terrify, and all the water of the wide formed ocean will shake with agitation. . . . When it stales in the ocean all the sea-water will become purified." Otherwise, "all the water in the sea would have perished from the contamination which the poison of the evil spirit has brought into its water." 21 Darmesteter thinks this ass is another incarnation of the storm-cloud, whereas West maintains that it is some foreign god tolerated by the Mazdean priests and fitted into their system. 22

Zoroastrianism, being inclined to abstraction and to personifying abstractions, has created a genius of victory, embodying the conquest of evil creatures and foes of every description which the myths attribute to Thraetaona, Tishtrya, and other heroes. The name of this deity is Verethraghna ("Victory over Adverse Attack"), an expression reminding us of the epithet Vrtrahan ("Slayer of Vrtra") of the mighty Vedic conqueror-god Indra. The vrtra, the "attack," is in the latter case made into the name of the assailing dragon Ahi, the Iranian Azhi.

Verethraghna penetrated into popular worship and even became the great Hercules of the Armenians, who were for centuries under the influence of Iranian culture and who called the hero Vahagn, a corruption of Verethraghna. 23 He was supposed to have been born in the ocean, probably a reminiscence of the sea Vourukasha, and he mastered not only the dragon Azhi, whom we know, but also Vishapa, whose name in the Avesta is an epithet of Azhi, meaning "whose saliva is poisonous," and he fettered them on Mount Damavand. 24 In a hymn of the Avesta 25 the various incarnations of Verethraghna are enumerated. Here he describes himself as "the mightiest in might, the most victorious in victory, the most glorious in glory, the most favouring in favour, the most advantageous in advantage, the most healing in healing." 26 He destroys the malice of all the malicious, of demons as well as of men, of sorcerers and spirits of seduction, and of other evil beings. He comes in the shape of a strong, beautiful wind, bearing the Glory made by Mazda that is both health and strength; 27 and next he conquers in the form of a handsome bull, with yellow ears and golden horns. 28

Thirdly, he is a white, beautiful horse like Tishtrya, and then a burden-bearing camel, sharp-toothed and long-haired. The fifth time he is a wild boar, and next, once more like Tishtrya, he manifests himself in the guise of a handsome youth of fifteen, shining, clear-eyed, and slender-heeled.

The seventh time he appears:

" In the shape of the Vareghna,

Grasping prey with what is lower,

Rending prey with what is upper, 29

Who of bird-kind is the swiftest,

Lightest, too, of them that fare forth.

He alone of all things living

To the arrow's flight attaineth,

Though well shot it speedeth onward.

Forth he flies with ruffling feathers

When the dawn begins to glimmer,

Seeking evening meals at nightfall,

Seeking morning meals at sunrise,

Skimming o er the valleyed ridges,

Skimming o er the lofty hill-tops,

Skimming o er deep vales of rivers,

Skimming o er the forests summits,

Hearing what the birds may utter." 30

Then Verethraghna comes as "a beautiful wild ram, with horns bent round," and again as "a fighting buck with sharp horns." That these are symbols of virility is shown by the next avatar, the tenth, in which he appears

"In a shining hero's body,

Fair of form, Mazda-created,

With a dagger gold-damascened,

Beautified with all adornment.

PLATE XXXIV:

IRANIAN DEITIES ON INDO-SCYTHIAN AND SASSANIAN COINS

I. TlSHTRYA

The god bears bow and arrows, and his representation as female is

probably due to imitation of the Greek Artemis. From a coin of

the Indo-Scythian king Huviska. After Stein, Zoroastrian Deities

on Indo-Scytbian Coins, No. X.

2. KHSHATHRA VAIRYA

The deity Desirable Kingdom," who is also the god of metals, is

appropriately represented in full metal armour. From a coin of

the Indo-Scythian king Huviska. After Stein, Zoroastrian Deities

on Indo-Scythian Coins, No. XI.

3. ARDOKHSHO

This goddess is evidently modelled on the Greek Tyche ("For tune

") and has been held to be the divinity Ashi. The name, as given

on the coin, seems to mean "Augmenting Righteousness," and in

view of the reference to Haurvatat and Ameretat as "the

companions who augment righteousness" (ashaokhshayantao

saredyayao, Tasna, xxxiii. 8-9), the Editor suggests that

Ardokhsho may be one of these Amesha Spentas, probably Ameretat,

the deity of vegetation. From a coin of the Indo-Scythian king

Huviska. After Stein, Zoroastrian Deities on Indo-Scythian Coins,

No. XVI.

4. ASHA VAHISHTA

In every respect except the name this deity is represented

precisely like Mithra. From a coin of the Indo-Scythian king

Huviska. After Stein, Zoroastrian Deities on Indo-Scythian Coins,

No. XVII.

5. AHURA MAZDA

The conventional representation of Ahura Mazda floats above what

appears to be a fire temple, rather than an altar, from which

rise the sacred flames. From a Parthian coin. After Drouin, in

Revue archeologique, 1884, Plate V, No. 2.

6. FIRE ALTAR

The altar here appears in its simplest form. From a Sassanian

coin in the collection of the Editor.

7. FIRE ALTAR

The altar is here much more elaborate in form. From a Sassanian

coin in the collection of the Editor.

8. FRAVASHI

Of interest as showing the appearance of a Fravashi ("Genius") in

the flame, and as representing the king as one of the guardians

of the fire, although strictly only the priests are permitted to

enter Atar's presence. From a Sassanian coin. After Dorn,

Collection de monnaies sassanides de ... 7. de Bartholomaei,

Plate VI, No. i.

Verethraghna gives the sources of manhood, the strength of the arms, the health of the whole body, the sturdiness of the whole body, and the eyesight of the kar-ftsh, which lives beneath the waters and can measure a ripple no thicker than a hair, in the Rangha whose ends lie afar, whose depth is a thousand times the height of a man. . . . He gives the eyesight of the stallion, which in the dark and cloudy night can perceive a horse's hair lying on the ground and knows whether it is from the head or from the tail. . . . He gives the eyesight of the golden-collared vulture, which from as far as the ninth district can perceive a piece of flesh no thicker than the fist, giving just as much light as a shining needle gives, as the point of a needle gives." 31

Yet even this is not all, for we are also told that

"Be they men or be they demons,

Verethraghna, Ahura's creature,

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Breaketh battle-hosts in pieces,

Cutteth battle-hosts asunder,

Presseth battle-hosts full sorely,

Shaketh battle-hosts with terror.

Then, when Verethraghna, Ahura's creature,

Bindeth fast the hands behind them,

Teareth out the eyeballs from them,

Maketh dull the ears with deafness

Of the close battle-hosts of the confederated countries,

Of the men false to Mithra [or, belying their pledges],

They cannot maintain their footing,

They cannot oppose resistance." 32

The poetic inspiration of this hymn has made it interesting to quote it at some length, especially as it shows the concentration in the person of the genius of victory of many features belonging to the old myths of contests on high.

This story was apt to have many replicas. Beyond those mentioned here Persian mythology possessed several more, such as the story of Keresaspa, who smote the horny dragon or the golden-heeled Gandarewa, 33 and whose exploits have been made the subject of an extensive narrative in the Shdhndmah, as will be set forth later on.

Iranian mythology, being essentially dualistic, contains numerous other contests, such as the overpowering of Yima, the king of the golden age, by Azhi Dahaka, the killing of the primeval bull by Mithra, the battle between Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu in the first times of creation, the war waged by Zarathushtra, the prophet, against the tenets of the demons, and the same struggle at the end of the world by the future prophet Saoshyant.

All this will be considered in subsequent chapters, and all this, according to certain mythologists like James Darmesteter, is the perpetual repetition (with some modifications) of the struggle in the storm-cloud between the light and the darkness. That conclusion is obviously exaggerated, although it is very likely, and very natural also, that features borrowed from the famous myth have penetrated into those other battles which are, each of them, incidents of the great dualistic war between the two creations. It is this conflict that we are now going to follow from the time of creation to the renovation of the world at the end of this period of strife.

1. On this cycle of legends see M. Breal, "Hercule et Cacus," in his Melanges de mythologie et de linguistique, Paris, 1877, pp. i- 161, and cf. Mythology of All Races, Boston, 1916, i. 86-87, 33

2. See supra, pp. 23-24.

3. Religion of Babylonia and Assyria, Boston, 1898, pp. 429, 432.

4- ib- P- 537-

5. ib. p. 541.

6. A. A. Macdonell, Vedic Mythology, Strassburg, 1897, p. 67.

7. For all these myths see supra, pp. 33, 35~3 6 87-88, 93, 133.

8. Yasna, ix. 7.

9. Fendiddd, xx. 24.

10. Thrita, whose name means "third," was the third man who prepared the haoma, according to Yasna, ix. 9.

11. Yasna, ix. 7.

12. Yasht, v. 61.

13. This line, frd thzuam zadanha paiti uzukhshdne zafarj paiti uzraocayeni, well illustrates the extent to which much of the Avesta in its present form has suffered interpolation. It is obvious, from the parallelism with Azhi Dahaka's speech, that the line should read simply frd thwdm paiti uzukhshdne ("thee will I besprinkle wholly" [i.e. with fire]). The same thing occurs below in the last line of the translation from Yasht, viii. 24, where the parallelism with dasandm gairindm aojo ("strength of mountains ten in number") shows that the word ndvayanam ("navigable") is interpolated in the line dasandm apdm ndvayanam aojo, which should read dasandm apam aojo ("strength of rivers ten in number").

14. Yasht, xix. 47-51. The "Child of Waters" is mentioned in magic Mandean inscriptions as "Nbat, the great primeval germ which the Life hath sent" (H. Pognon, Inscriptions mandaites des coupes de Khouabir, Paris, 1898, pp. 63, 68; cf. also p. 95).

15. G. Hiising (Die traditionelle Ueberlieferung und das arische System, p. 53) thinks that Apaosha means "Coverer," "Concealer" (from apa + var).

16. Yasht, viii. 4-5.

17. Yasht, viii. 23-24.

18. Yasht, viii. 29.

19. Yasht, viii. 13. Fifteen was the paradisiac age to the Iranian mind.

20. Bundahish, vii. 4-7 (tr. E. W. West, in SEE v. 26-27).

21. Bundahish) xix. i-io.

22. J. Darmesteter, Ormazd et Ahriman, p. 148; E. W. West, in SEE v. 67, note 4.

23. M. Ananikian, "Armenia (Zoroastrianism in)," in Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics, i. 799, Edinburgh, 1908.

24. J. Darmesteter, Zend-Avesta, ii. 559.

25. Yasht, xiv.

26. Cf. the healing functions of Thrita and Thraetaona, supra, p. 265, and infra, p. 318.

27. Cf. the story of Atar, supra, pp. 266-67.

28. Cf. the legend of Tishtrya, supra, p. 269.

29. Namely, seizing its prey with its talons and rending it with its beak. The bird Vareghna is apparently the raven.

30. Yasht, xiv. 19-21. The comparison of the lightning to a bird is of frequent occurrence.

31. Yasht, xiv. 27-33.

32. Yasht, xiv. 62-63.

33. Yasna, ix. II.

CHAPTER II. MYTHS OF CREATION

THE Iranian legend of creation is as follows. 1 Ahura Mazda lives eternally in the region of infinite light, but Angra Mainyu, on the contrary, has his abode in the abyss of endless darkness, between them being empty space, the air. After Ahura Mazda had produced his creatures, which were to remain "three thousand years in a spiritual state, so that they were unthinking and unmoving, with intangible bodies," the Evil Spirit, having arisen from the abyss, came into the light of Ahura Mazda. Because of his malicious nature, he rushed in to destroy it, but seeing the Good Spirit was more powerful than himself, he fled back to the gloomy darkness, where he formed many demons and fiends to help him.

Then Ahura Mazda saw the creatures of the Evil Spirit, terrible, corrupt, and bad as they were, and having the knowledge of what the end of the matter would be, he went to meet Angra Mainyu and proposed peace to him: "Evil spirit! bring assistance unto my creatures, and offer praise! so that, in reward for it, thou and thy creatures may become immortal and undecaying." But Angra Mainyu howled thus: "I will not depart, I will not provide assistance for thy creatures, I will not offer praise among thy creatures, and I am not of the same opinion with thee as to good things. I will destroy thy creatures for ever and everlasting; moreover, I will force all thy creatures into disaffection to thee and affection for myself." Ahura Mazda, however, said to the Evil Spirit, "Appoint a period so that the intermingling of the conflict may be for nine thousand years"; for he knew that by setting that time the Evil Spirit would be undone. The latter, unobservant and ignorant, was content with the agreement, and the nine thousand years were divided so that during three thousand years the will of Mazda was to be done, then for three thousand years there is an intermingling of the wills of Mazda and Angra Mainyu, and in the last third the Evil Spirit will be disabled.

Afterward Ahura Mazda recited the powerful prayer Yathd ahu vairyd 2 and, by so doing, exhibited to the Evil Spirit his own triumph in the end and the impotence of his adversary. Perceiving this, Angra Mainyu became confounded and fell back into the gloomy darkness, where he stayed in confusion for three thousand years. During this period the creatures of Mazda remained unharmed, but existed only in a spiritual or potential state; and not until this triple millennium had come to an end did the actual creation begin.

As the first step in the cosmogonic process Ahura Mazda produced Vohu Manah ("Good Mind"), whereupon Angra Mainyu immediately created Aka Manah ("Evil Mind"); and in like manner when Ahura Mazda formed the other Amesha Spentas, his adversary shaped their counterparts. After all this was completed, the creation of the world took place in due order sky, water, earth, plants, animals, mankind.

In shaping the sky and the heavenly bodies Ahura Mazda produced first the celestial sphere and the constellations, especially the zodiacal signs. The stars are a warlike army des tined for battle against the evil spirits. There are six million four hundred and eighty thousand small stars, and to the many which are unnumbered places are assigned in the four quarters of the sky. Over the stars four leaders preside, Tishtrya (Sirius) being the chieftain of the east, Haptok Ring (Ursa Major) of the north, Sataves of the west, and Vanand of the south. Then he created the moon and afterward the sun.

In the meanwhile, however, the impure female demon Jahi had undertaken to rouse Angra Mainyu from his long sleep

"Rise up, we will cause a conflict in the world," but this did not please him because, through fear of Ahura Mazda, he was not able to lift up his head. Then she shouted again, "Rise up, thou father of us! for I will cause that conflict in the world wherefrom the distress and injury of Auharmazd and the archangels will arise. ... I will make the whole creation of Auharmazd vexed."

When she had shouted thrice, Angra Mainyu was delighted and started up from his confusion, and he kissed Jahi upon the head and howled, "What is thy wish? so that I may give it thee? " And she shouted, "A man is the wish, so give it to me." Now the form of the Evil Spirit was a log like a lizard's body, but he made himself into a young man of fifteen years, 3 and this brought the thought of Jahi unto him.

Then Angra Mainyu with his confederate demons went toward the luminaries that had just been created, and he saw the sky and sprang into it like a snake, 4 so that the heavens were as shattered and frightened by him as a sheep by a wolf. Just like a fly he rushed out upon the whole creation and he made the world as tarnished and black at midday as though it were in dark night. He created the planets in opposition to the chieftains of the constellations, and they dashed against the celestial sphere and threw the constellations into confu sion, 5 and the entire creation was as disfigured as though fire had burned it and smoke had arisen.

For ninety days and nights the Amesha Spentas and Yazatas contended with the confederate demons and hurled them confounded back into the darkness. The rampart of the sky was now built in such a manner that the fiends would no more be able to penetrate into it; and when the Evil Spirit no longer found an entrance, he was compelled to rush back to the nether darkness, beholding the annihilation of the demons and his own impotence.

Then as the second step in the cosmogonic process Ahura Mazda created the waters. 6 These converge into the sea Vourukasha ("Wide-Gulfed"), which occupies one third of this earth in the direction of the southern limit of Mount Alburz and is so wide that it contains the water of a thousand lakes. Every lake is of a particular kind; some are great, and some are small, while others are so vast that a man with a horse could not compass them around in less than forty days.

All waters continually flow from the source Ardvi Sura Anahita ("the Wet, Strong, and Spotless One"). There are a hundred thousand golden channels, and the water, warm and clear, goes through them toward Mount Hugar, the lofty. On the summit of that mountain is Lake Urvis, into which the water flows, and becoming quite purified, returns through a different golden channel. At the height of a thousand men an open golden branch from that affluent is connected with Mount Ausindom and the sea Vourukasha, whence one part flows forth to the ocean for the purification of the sea, while another portion drizzles in moisture upon the whole of this earth. All the creatures of Mazda acquire health from it, and it dispels the dryness of the atmosphere.

There are, moreover, three large salt seas and twenty-three small. Of the three, the Puitika (Persian Gulf) is the greatest, and the control of it is connected with moon and wind; it comes and goes in increase and decrease because of her revolving. From the presence of the moon two winds continually blow; one is called the down-draught, and one the up-draught, and they produce flow and ebb.

The spring Ardvi Sura Anahita, which we have just men tioned, and from which all rivers flow down to the earth, is worshipped as a goddess. She is celebrated in the fifth Yasht of the Avesta as the life-increasing, the herd-increasing, the fold-increasing, who makes prosperity for all countries. She runs powerfully down to the sea Vourukasha, and all its shores are boiling over when she plunges foaming down; she, Ardvi Sura, who has a thousand gulfs and a thousand outlets.

Not only does Anahita bring fertility to the fields by her waters, but she makes the seed of all males pure and sound, purifies the wombs of all females, causes them to bring forth in safety, and puts milk in their breasts. 7 She gave strength to all heroes of primeval times so that they were able to overcome their foes, whether the demons, the serpent Azhi, or the golden-heeled Gandarewa.

She is personified under the appearance of a handsome and stately woman. 8

"Yea in truth her arms are lovely,

White of hue, more strong than horses;

Fair-adorned is she and charming;

With a lovely maiden's body,

Very strong, of goodly figure,

Girded high and standing upright,

Nobly born, of brilliant lineage;

Ankle-high she weareth foot-gear

Golden-latcheted and shining.

She is clad in costly raiment,

Richly pleated and all golden,

For adornment she hath ear-rings

With four corners and all golden.

On her lovely throat a necklace

She doth wear, the maid full noble,

Ardvi Sura Anahita.

Round her waist she draws a girdle

That fair-formed may be her bosom,

That well-pleasing be her bosom.

On her brow a crown she placeth,

Ardvi Sura Anahita,

Eight its parts, its jewels a hundred,

Fair-formed, like a chariot-body,

Golden, ribbon-decked, and lovely,

Swelling forth with curve harmonious.

She is clad in beaver garments,

Ardvi Sura Anahita,

Of the beaver tribe three hundred."

This precise description points to the existence of representations of the goddess, a thing unusual in Persia in ancient times. But Anahita, as Herodotus tells us, was at that period identified with the Semitic Ishtar, a divinity of fertility and fecundity, and a powerful deity invoked in battle and in war, both these functions being attributed to Anahita in the hymn quoted above. Ishtar seems to have absorbed in Babylonia many of the attributes of Ea's consort Nin Ella, the "Great Lady of the Waters," the "Pure Lady" of birth, whose name is the exact equivalent of Ardvi Sura Anahita; and it was Nin Ella, more probably than Ishtar, who was the prototype of the Iranian goddess.

The Evil Spirit, however, also came to the water and sent Apaosha, the demon of drought, to fight against Tishtrya (Sirius), who bestows water upon the earth during the summer; the result of their encounter being the conflict that has been narrated above.

The third of the processes of creation was the shaping of the world. After the rain of Tishtrya had flooded the earth and purified it from the venom of the noxious creatures, and when the waters had retired, the thirty-three kinds of land were formed. These are distributed into seven portions: one is in the middle, and the others are the six regions (keshvars) of the earth.

To counteract the work of Ahura Mazda, Angra Mainyu came and pierced the earth, entering straight into its midmost part; and when the earth shook, the mountains arose. First, Mount Alburz (Hara Berezaiti) was created, and then the other ranges of mountains came into being; "for as Alburz grew forth all the mountains remained in motion, for they have all grown forth from the root of Alburz. At that time they came up from the earth, like a tree which has grown up to the clouds and its root to the bottom." The mountains stand in a row about Alburz, which is the knot of lands and is the highest peak of all, lifting its head even to the sky. On one of its summits, named Taera, the sun, the moon, and the stars rise, and from another of its heights, Hukairya, the water of Ardvi Sura Anahita flows down, while on it the haoma, the plant of life, is set. What plant this haoma was we do not know, but its intoxicating qualities produced an exaltation which naturally caused it to be regarded as divine.

Next came the creation of the vegetable kingdom when Ameretat, the Amesha Spenta who has plants under her guardianship, pounded them small and mixed them with the water which Tishtrya had seized. Then the dog-star made that water rain down over all the earth, on which plants sprang up like hair upon the heads of men. Ten thousand of them grew forth, these being provided in order to keep away the ten thousand diseases which the evil spirit produced for the creatures. From those ten thousand have sprung the hundred thousand species of plants that are now in the world.

From these germs the "Tree of All Seeds" was given out and grew up in the middle of the sea Vourukasha, where it causes every species of plant to increase. Near to that "Tree of All Seeds" the Gaokerena ("Ox-Horn") tree was produced to avert decrepitude. This is necessary to bring about the renovation of the universe and the immortality that will follow; every one who eats it becomes immortal, and it is the chief of plants. 9

The Evil Spirit formed a lizard in the deep water of Vouru kasha that it might injure the Gaokerena; 10 but to keep away that lizard Ahura Mazda created ten kar-fish, which at all times continually circle around the Gaokerena, so that the head of one of them never ceases to be turned toward the lizard. Together with the lizard those fish are spiritually fed, and till the renovation of the universe they will remain in the sea and struggle with one another.

The Gaokerena tree is also called "White Haoma." It is one of the manifestations of the famous haoma-plant, which has been mentioned many times, while its terrestrial form, the yellow haoma, is the plant of the Indo-Iranian sacrifice and the one which gives strength to men and gods. It is with this thought in mind that the sacrificer invokes "Golden Haoma":

"Thee I pray for might and conquest,

Thee for health and thee for healing,

Thee for progress and for increase,

Thee for strength of all my body,

Thee for wisdom all-adorned.

Thee I pray that I may conquer,

Conquer all the haters hatred,

Be they men or be they demons,

Be they sorcerers or witches,

Rulers, bards, or priests of evil,

Treacherous things that walk on two feet,

Heretics that walk on two feet,

Wolves that go about on four feet,

Or invading hordes deceitful

With their fronts spread wide for battle." 11

Above all, however, Haoma is expected to drive death afar, to give long life, 12 and to grant children to women and hus bands to girls.

"Unto women that would bring forth

Haoma giveth brilliant children,

Haoma giveth righteous offspring.

Unto maidens long unwedded

Haoma, quickly as they ask him,

Full of insight, full of wisdom,

Granteth husbands and protectors." 13

The terrestrial haoma is said to grow on the summits of the mountains, especially on Alburz (Hara Berezaiti), to which divine birds brought it down from heaven. It is collected in a box, which is placed in an iron vase, and after the priest has taken five or seven pieces of the plant from the box and washed them in the cup, the stalk of haoma is pounded in a mortar and filtered through the vara, the juice being then mixed with other sacred fluids and ritual prayers being recited.

The Haoma sacrifice is supposed to date back to primeval times, its first priests being Vivanghvant, Athwya, Thrita, and Pourushaspa, the heroes of ancient ages. The offering of it is an Indo-Iranian rite, and the same legends are found in the Veda, where amrta soma ("immortal soma" [= haoma]) has been brought from heaven to a high mountain by an eagle. Swift as thought, the bird flew to the iron castle of the sky and brought the sweet stalks back. 14 It is actually an Indo-European myth closely associated with the fire-myths, for the fire of the sky (the lightning) is said to have been brought to earth either by a bird or by a daring human being (Prometheus), while exactly the same story is told of the earthly fire-drink, the honey-mead, the draught of immortality (apfipoa-ia). Curiously enough, the Babylonian epic also knows of a marvellous plant that grows on the mountains, the plant "of birth" be longing to Shamash, the sun-god. When the wife of the hero Etana is in distress because she is unable to bring into the world a child which she has conceived, Etana prays Shamash to show him the "plant of birth": "O Lord, let thy mouth command, and give me the plant of birth. Reveal to me the plant of birth, bring forth the fruit, grant me offspring "; and an eagle then helps Etana to obtain the plant. 15 The Etana-myth is also related to the story of Rustam's birth, as will be narrated in a subsequent chapter.

When Angra Mainyu, the destroyer, came to the plants, he found them with neither thorn nor bark about them; but he coated them with bark and thorns and mixed their sap with poison, so that when men eat certain plants, they die. 16 There was also a beautiful tree with a single root. Its height was several feet, and it was without branches and without bark, juicy and sweet; but when the Evil Spirit approached it, it became quite withered. 17

In Iranian mythology the creation of fire constitutes, to all intents, a subdivision of the creation of the vegetable world, the close connexion between fire and plants in Indo-Iranian conceptions being due to the fact that it was the custom of those peoples to obtain flame by taking a stick of hard wood, boring it into a plank or board of softer wood (that of a lime-tree, for instance), and turning it round and round till fire was produced by the friction. 18 For this reason the Veda declares that Fire (Agni) is born in wood, is the embryo of plants, and is distributed in plants. But fire has likewise a heavenly origin, for it is the son of the sky-god (Dyaus) and was born in the highest heavens, whence it was brought to earth, as already narrated, though it is also described as having its origin in the aerial waters. Owing to his divine births, Agni in India is often regarded as possessing a triple character and is trisadhastha ("having three stations or dwellings"), his abodes being heaven, earth, and the waters. The fire of the hearth has been held in very great veneration among all Indo-Europeans. It was adored as Hestia in Greece and as Vesta in Rome, while in India the domestic Agni is called Grhapati (" Lord of the House"). It is also the guest (atithi) in human abodes, for it is an immortal who has taken up his home among mortals; it is Vispati ("Lord of the Settlers"), their leader, their protector. It is the friend, the brother, the nearest kinsman of man; 19 it is the great averter of evil beings, just as it keeps off wild ani mals in the forest at night.

The second aspect under which fire is subservient to human ity is the part that it plays as the messenger who brings to the gods the offerings of men. It is the sacrificial fire, and as such it is called Narasamsa ("Praise of Men") in India. 20

PLATE XXXV: ANCIENT FIRE TEMPLE NEAR ISFAHAN

The structure, originally domed, is built of unburnt bricks. Its height is about fourteen feet, and its diameter about fifteen; octagonal in plan, its eight doors face the eight points of the compass; the inner sanctuary is circular. It apparently dates at least from the Sassanian period, and its shape may be compared with what seems to be a fire temple as pictured on Parthian coins (see Plate XXXIV, No. 5). For the history of the shrine, so far as known, see Jackson, Persia Past and Present, pp. 25661. After a photograph by Professor A. V. Williams Jackson.

As is well known, fire enjoys quite a special veneration in Iran, and under its first guise, as a representative of divine essence on earth, it dwells in the home of each of the faithful. Particular reverence is given to the sacred flame which is main tained with wood and perfumes in the so-called fire temples, two kinds of which are distinguished: the great temple for the Bahram fire and the small shrine, or ddardn. The Bahrain fire, whose preparation lasts an entire year, is constituted out of sixteen different kinds of fire and concentrates in itself the essence and the soul of all fires. 21 It is maintained by means of six logs of sandal-wood and is placed in the sacred room, vaulted like a dome, on a vase. Five times a day a mobed, or priest, enters the room. The lower part of his face is covered with a veil (A vesta paitiddna), preventing his breath from polluting the sacred fire, and his hands are gloved. He lays down a log of sandal-wood and recites three times the words dushmata, duzhukhta, duzhvarshta to repel "evil thoughts, evil words, evil deeds."

As in India, so in Iran several kinds of fire are distinguished: Berezisavanh ("Very Useful") is the general name of the Bahrain fire, the sacred one which shoots up before Ahura Mazda and is kept in the fire temples; Vohu Fryana ("Good Friend") is the fire which burns in the bodies of men and animals, keeping them warm; Urvazishta ("Most Delightful") burns in the plants and can produce flames by friction; Vazishta ("Best-Carrying") is the aerial fire, the lightning that purifies the sky and slays the demon Spenjaghrya; Spenishta ("Most Holy") burns in paradise in the presence of Ahura Mazda.

Of these five fires, one drinks and eats, that which is in the bodies of men; one drinks and does not eat, that which is in plants, which live and grow through water; two eat and do not drink, these being the fire which is ordinarily used in the world, and likewise the fire of Bahram (= Berezisavanh); one consumes neither water nor food, and this is the fire Vaishta. 22

This classification enjoyed a very great success among the Talmudists, who took it from the Mazdeans in the second century A.D. 23 Besides these five fires, the Avesta knows of Nairyosangha, who is of royal lineage and whose name reminds us of nardsamsa, the epithet of Agni ("the Fire") in India. Like Narasamsa Agni, Nairyosangha is the messenger between men and gods and he dwells with kings, inasmuch as they are endowed with a divine majesty. The emanation of divine es sence in kings, however, is more often called khvarenanh (Old Persian farnah), which is a glory that attaches itself to monarchs as long as they are worthy representatives of divine power, as will be seen later in the story of Yima.

The fire was all light and brilliancy, but Angra Mainyu came up to it, as to all beings of the good creation, and marred it with darkness and smoke. 23

The fifth creation was the animal realm. Just as there was a tree Gaokerena which had within itself all seeds of plants and trees, so Iranian mythology knows of a primeval ox in which were contained the germs of the animal species and even of a certain number of useful plants.

This ox, the sole-created animate being, was a splendid, strong animal which, though sometimes said to be a female, 25 is usually described as a bull. When the Evil Spirit came to the ox, Ahura Mazda ground up a healing fruit, called bindk, so that the noxious effects of Angra Mainyu might be minimized; but when, despite this, "it became at the same time lean and ill, as its breath went forth and it passed away, the ox also spoke thus: The cattle are to be created, their work, labour, and care are to be appointed. When Geush Urvan ("the Soul of the Ox") came forth from the body, it stood up and cried thus to Ahura Mazda, as loudly as a thousand men when they raise a cry at one time: "With whom is the guardianship of the creatures left by thee, now that ruin has broken into the earth, and vegetation is withered, and water is troubled? Where is the man of whom it was said by thee thus:

I will produce him, so that he may preach carefulness? Ahuja Mazda answered : "You are made ill, O Goshurvan! you have the illness which the evil spirit brought on; if it were proper to produce that man in this earth at this time, the evil spirit would not have been oppressive in it." Geush Urvan was not satisfied, however, but walked to the vault of the stars and cried in the same way, and his voice came to the moon and to the sun till the Fravashi 26 of Zoroaster was exhibited to it, and Ahura Mazda promised to send the prophet who would preach carefulness for the animals, whereupon the soul of the ox was contented and agreed to nourish the creatures and to protect the animal world.

From every limb of the ox fifty-five species of grain and twelve kinds of medicinal plants grew forth, their splendour and strength coming from the seminal energy of the ox. Delivered to the moon, that seed was thoroughly purified by the light of the moon and fully prepared in every way, and then two oxen arose, one male and one female, after which two hundred and eighty-two pairs of every single species of animal appeared upon the earth. The quadrupeds were to live on the earth, the birds had their dwelling in the air, and the fish were in the midst of the water.

Another myth ascribes the killing of the primeval ox to the god Mithra.

The legend concerning the birth and the first exploits of Mithra runs thus. 27 He was born of a rock on the banks of a river under the shade of a sacred fig-tree, coming forth armed with a knife and carrying a torch that had illumined the sombre depths. When he had clothed himself with the leaves of the fig-tree, detaching the fruit and stripping the tree of its leaves by means of his knife, he undertook to subjugate the beings already created in the world. First he measured his strength with the sun, with whom he concluded a treaty of friendship an act quite in agreement with his nature as a god of contracts and since then the two allies have supported each other in every event.

Then he attacked the primeval ox. The redoubtable animal was grazing in a pasture on a mountain, but Mithra boldly seized it by the horns and succeeded in mounting it. The ox, infuriated, broke into a gallop, seeking to free itself from its rider, who relaxed his hold and suffered himself to be dragged along till the animal, exhausted by its efforts, was forced to surrender. The god then dragged it into a cave, but the ox succeeded in escaping and roamed again over the mountain pastures, whereupon the sun sent his messenger, the raven, to help his ally slay the beast. Mithra resumed his pursuit of the ox and succeeded in overtaking it just at the moment when it was seeking refuge in the cavern which it had quitted. He seized it by the nostrils with one hand and with the other he plunged his hunting-knife deep into its flank. Then the prodigy related above took place. From the limbs and the blood of the ox sprang all useful herbs and all species of animals, and "the Soul of the Ox" (Geush Urvan) went to heaven to be the guardian of animals.

The myths relating to the primeval ox contain traces of several older Indo-European myths. First, the conception of the production of various beings out of the body of a prime val gigantic creature is a cosmogonic story, fairly common in the mythology of many nations and reproduced in the Eddie myth of the giant Ymir, who was born from the icy chaos and from whose arm sprang both a man and a woman. He was then slain by Odhin and his companions, and of the flesh of Ymir was formed the earth, of his blood the sea and the waters, of his bones the mountains, of his teeth the rocks and stones, and of his hair all manner of plants. 28

Many features recall to us, on the other hand, the contests on high between a light-god and some monster who detains the rain which is the source of life for terrestrial beings and which is often personified under the shape of a cow. The kine are concealed in caves or on mountains, or the monster is hidden in a mountain cavern and escapes, as is the case with Verethraghna and Azhi in the Armenian myth. In the birth of Mithra traces of solar myths may also be detected. The raven is the messenger of the sun because, like the bird Vareghna,

" Forth he flies with ruffling feathers

When the dawn begins to glimmer." 29

PLATE XXXVI: 1

MlTHRA BORN FROM THE ROCK

The deity, bearing a dagger in one hand and a lighted torch in

the other, rises from the rock. From a bas-relief found in the

Mithraeum which once occupied the site of the church of San

Clemente at Rome. After Cumont, The Mysteries of

Mithra, Fig. 30.

2. MlTHRA BORN FROM THE ROCK

The divinity, lifting a cluster of grapes in his right hand,

emerges from the rock, on which he rests his left hand. On the

rock are sculptured a quiver, arrow, bow, and dagger. On either

side of Mithra stand the two torch-bearers, Caut and Cautopat

(whose names, in the opinion of the Editor, mean "the Burner" and

"He Who Lets His Burned [Torch] Fall"), doubt less symbolizing

the rising and the setting sun, as Mithra is the sun at noonday.

From a white marble formerly in the Villa Giustiniani, Rome, but

now lost. After Cumont, The Mysteries of

Mithra, Fig. 31.

Here, then, we are dealing with a secondary myth.

As regards the various species of animals produced from the ox, the Mazdean books speak first of mythical beings, such as the three-legged ass that has been described above, the lizard created by Angra Mainyu to destroy the tree Gaokerena, and the kar-ftshes that defend it. They know, moreover, of an ox-fish that exists in all seas; when it utters a cry, all fishes become pregnant, and all noxious water creatures cast their young. There is also an ox, called Hadhayosh or Sarsaok in Pahlavi, on whose back men in primeval times passed from region to region across the sea Vourukasha. Many mythical birds are known in the Mazdean mythology. We have already seen the raven as an incarnation of Verethraghna ("Victory") and as a messenger of the sun to Mithra. The most celebrated bird, however, is Saena, the Simurgh of the Persians, whose open wings are like a wide cloud and full of water crowning the mountains. 30 He rests on the tree of the eagle, the Gaokerena, in the midst of the sea Vourukasha, the tree with good remedies, in which are the seeds of all plants. When he rises aloft, so violently is the tree shaken that a thousand twigs shoot forth from it; when he alights, he breaks off a thousand twigs, whose seeds are shed in all directions.

Near this powerful bird sits Camrosh, who would be king of birds, were it not for Saena. His work is to collect the seed which is shed from the tree and to convey it to the place where Tishtrya seizes the water, so that the latter may take the water containing the seed of all kinds and may rain it on the world. 31 When the Turanians invade the Iranian districts for booty and effect devastation, Camrosh, sent by the spirit Bcrejya, flies from the loftiest of the lofty mountains and picks up all the non-Iranians as a bird does corn. 32

The bird Varegan, Varengan, or Vareghna (sometimes translated "raven") is the swiftest of all and is as quick as an arrow. We have already seen 33 that he is one of Verethraghna's incarnations, and under his shape the kingly Glory (Khvarenanh) of Yima left the guilty hero and flew up to heaven. 34 He is essentially a magic bird with mysterious power. Thus Zoroaster is represented as asking Ahura Mazda what would be the remedy "should I be cursed in word or thought." Ahura Mazda an swers: "Thou shouldst take a feather of the wide-feathered bird Varengan, O Spitama Zarathushtra. With that feather thou shouldst stroke thy body, with that feather thou shouldst conjure thy foe. Either the bones of the sturdy bird or the feathers of the sturdy bird carry boons.

Neither can a man of brilliance

Slay or rout him in confusion.

It first doth bring him reverence,

it first doth bring him glory.

Help to him the feather giveth

Of the bird of birds, Varengan." 35

The same thing is recorded of Saena (the Simurgh) in the Shdhndmah. When Zal leaves the nest of the Simurgh, who has brought him up, his foster-father gives him one of his feathers so that he may always remain under the shadow of his power.

"Bear this plume of mine

About with thee and so abide beneath

The shadow of my Grace. Henceforth if men

Shall hurt or, right or wrong, exclaim against thee,

Then burn the feather and behold my might." 36

When the side of Rudabah, Rustam's mother, is opened to allow the child to be brought into the world, Zal heals the wound by rubbing it with a feather of the Simurgh, and when Rustam is wounded to death by Isfandyar, he is cured in the same way. 37

The bird Karshiptar has a more intellectual part to play, for he spread Mazda's religion in the enclosure in which the prime val king Yima had assembled mankind, 38 as will be narrated below. There men recited the Avesta in the language of birds. 39

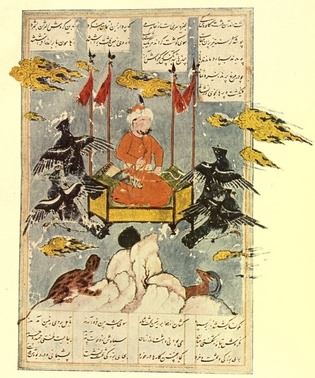

PLATE XXXVII: THE SIMURGH

The Slmurgh, flying from its mountain home, restores the infant

Zal to his father Sam, who had caused the child to be abandoned

because it had been born with white hair. In his hand the prince

carries the ox-headed mace as a symbol of royalty. The painting

shows marked Perso-Mongolian influence. From a Persian manuscript

of the Shahnamah, dated 1587-88 A.D., now in the Metropolitan

Museum of Art, New York.

The bird Asho-zushta also has the Avesta on his tongue, and when he recites the words the demons are frightened. 40 When the nails of a Zoroastrian are cut, the faithful must say: "O Asho-zushta bird! these nails I present to thee and consecrate to thee. May they be for thee so many spears and knives, so many bows and eagle-winged arrows, so many sling-stones against the Mazainyan demons." 41 If one recites this formula, the fiends tremble and do not take up the nails, but if the parings have had no spell uttered over them, the demons and wizards use them as arrows against the bird Asho-zushta and kill him. Therefore, when the nails have had a charm spoken over them, the bird takes them and eats them, that the fiends may do no harm by their means. 42 Asho-zushta is probably the theological name of the owl. 43

The part played by birds as transmitters of revelation leads in later literature to the identification of the Simurgh with Supreme Wisdom. 44 As we have said more than once, the con ception of mythical birds dates back to Indo-Iranian even Indo-European times, and often those birds are incarnations of the thunderbolt, the sun, the fire, the cloud, etc. In the Rgveda the process is seen in operation. The soma is often compared with or called a bird; the fire (agni) is described as a bird or as an eagle in the sky; and the sun is at times a bird, whence it is called garutmant ("winged"). The most promi nent bird in the Veda, however, is the eagle, which carries the soma to Indra and which appears to represent lightning. 45 So in Eddie mythology the god Odhin, transforming himself into an eagle, flies with the mead to the realm of the gods. Besides these mythical birds there are one hundred and ten species of winged kind, such as the eagle, the vulture, the crow, and the crane, to say nothing of the bat, which has milk in its teat and suckles its young, and is created of three races, bird, dog, and musk-rat, for it flies like a bird, has many teeth like a dog, and dwells in holes like a musk-rat.

Other beasts and birds were formed in opposition to noxious creatures: the white falcon kills the serpent with its wings; the magpie destroys the locust; the vulture, dwelling in decay, is created to devour dead matter, as do the crow the most precious of birds and the mountain kite. 46 So it is also with the quadrupeds, for the mountain ox, the mountain goat, the deer, the wild ass, and other beasts devour snakes. Dogs are created in opposition to wolves and to secure the protection of sheep; the fox is the foe of the demon Khava; the ichneumon destroys the venomous snake and other noxious creatures in burrows; and the great musk-animal was formed to counter act ravenous intestinal worms. The hedgehog eats the ant which carries off grain; when the grain-carrying ant travels over the earth, it produces a hollow path; but when the hedgehog passes over it, the track becomes level. The beaver is in opposition to the demon which is in the water.

The cock, in co-operation with the dog, averts demons and wizards at night and helps Sraosha in that task, and the shepherd s dog and the watch-dog of the house are also indispensable creatures and destroyers of fiends. The dog likewise annihilates covetousness and disobedience, and when it barks it destroys pain, while its flesh and fat are remedies for averting decay and anguish from man. Ahura Mazda created nothing useless whatever; all these animals have been formed for the well-being of mankind and in order that the fiends may continually be destroyed. 47

NOTES

1. Adapted from E. W. West's translation of Bundahish, i-iii, and Selections of Zdt-Sparam, i-ii, in SBE v. 1-19, 156-63.