II

THE MAHABHARATA: KRISHNA THE HERO

The first reference to Krishna occurs in the Chandogya

Upanishad of perhaps the sixth century B.C. Upanishads

were 'forest sittings' or 'sessions with teachers.' Sages and

their disciples discussed the nature of life and strove to

determine the soul's exact relationship to God. The

starting-point was the theory of re-incarnation. Death, it was

believed, did not end the soul. Death was merely a stepping-stone

to another life, the soul moving from existence to existence in

one long effort to escape re-birth. From this cycle, only one

experience could bring release and that was consciousness or

actual knowledge of the supreme Spirit. When that state was

achieved, the soul blended with the Godhead and the cycle ended.

The problem of problems, therefore, was how to attain such

knowledge. The Chandogya Upanishad does not offer any

startling solution to this matter. The teacher who conducts the

session is a certain Ghora of the Angirasa family and it is the

person of his disciple rather than his actual message which

concerns us. The disciple is called Krishna and his mother has

the name Devaki. Devaki is the later Krishna's mother and there

is accordingly every reason to suppose that the two Krishnas are

the same. Nothing, however, is stated of this early Krishna's

career and although parts of the sage's teachings have been

compared to passages in the Gita,[3] Krishna himself

remains a vague and dim name.

For the next few centuries, knowledge of Krishna remains in

this fragmentary state. Nothing further is recorded and not until

the great Indian epic, the Mahabharata, crystallizes out

between the fourth century B.C. and the fourth century A.D. does

a more detailed Krishna make his appearance.[4] By the end of

this period, many vital changes had taken place. The Indian

world-view had become much clearer and it is possible not only to

connect Krishna with a definite character but to see him in clear

relation to cosmic events. The supreme Spirit was now envisaged

as a single all-powerful God, known according to his functions as

Brahma, Vishnu and Siva. As Brahma, he brought into existence

three worlds—heaven, earth and the nether regions—and

also created gods or lesser divinities, earth and nature spirits, demons, ogres and men

themselves. Siva, for his part, was God the final dissolver or

destroyer, the source of reproductive energy and the inspirer of

asceticism. He was thought of in many forms—as a potent

ascetic, a butcher wild for blood, a serene dancer—and in

his character of regenerator was represented by his symbol, the

lingam or phallus. The third aspect, Vishnu, was God in

his character of loving protector and preserver. This great

Trinity was ultimately supreme but under it were a number of

lesser powers. Those that represented the forces of good were

called devas or gods. They were led by their king, Indra,

lord of clouds, and associated with him were gods such as Agni

(fire), Varuna (water), Surya the sun and Kama the god of

passion. These gods lived in Indra's heaven, a region above the

world but lower than Vaikuntha, the heaven of Vishnu.

Dancing-girls and musicians lived with them and the whole heaven

resembled a majestic court on earth. From this heaven the gods

issued from time to time intervening in human affairs. Demons, on

the other hand, were their exact opposites. They represented

powers of evil, were constantly at war with the gods and took

vicious pleasure in vexing or annoying the good. Below gods and

demons were men themselves.

In this three-tiered universe, transmigration of souls was

still the basic fact but methods of obtaining release were now

much clearer. A man was born, died and then was born again. If he

acted well, did his duty and worked ceaselessly for good, he

followed what was known as the path of dharma or

righteousness. This ensured that at each succeeding birth he

would start a stage more favourably off than in his previous

existence till, by sheer goodness of character, he qualified for

admission to Indra's heaven and might even be accounted a god.

The achievement of this status, however, did not complete his

cycle, for the ultimate goal still remained. This was the same as

in earlier centuries—release from living by union with or

absorption into the supreme Spirit; and only when the individual

soul had reached this stage was the cycle of birth and re-birth

completed. The reverse of this process was illustrated by the

fate of demons. If a man lapsed from right living, his second

state was always worse than his first. He might then be born in

humble surroundings or if his crimes were sufficiently great, he

became a demon. As such, his capacity for evil was greatly

increased and his chances of ultimate salvation correspondingly

worsened. Yet even for demons, the ultimate goal was the

same—release from living and blissful identification with

the Supreme.

Dharma alone, however, could not directly achieve this

end. This could be done by the

path of yoga or self-discipline—a path which

involved penances, meditation and asceticism. By ridding his mind

of all desires and attachments, by concentrating on pure

abstractions, the ascetic 'obtained insight which no words could

express. Gradually plumbing the cosmic mystery, his soul entered

realms far beyond the comparatively tawdry heavens where the

great gods dwelt in light and splendour. Going "from darkness to

darkness deeper yet," he solved the mystery beyond all mysteries;

he understood, fully and finally, the nature of the universe and

of himself and he reached a realm of truth and bliss, beyond

birth and death. And with this transcendent knowledge came

another realization—he was completely, utterly, free. He

had found ultimate salvation, the final triumph of the

soul.'[5] Such a complete identification with the

supreme Spirit, however, was not easily come by and often many

existences were required before the yogi could achieve this

sublime end.

There remained a third way—the path of bhakti or

devotion to God. If a man loved God not as an abstract spirit but

as a loving Person, if he loved with intensity and singleness of

heart, adoration itself might obtain for him the same reward as a

succession of good lives. Vishnu as protector might reward love

with love and confer immediately the blessing of salvation.

The result, then, was that three courses were now open to a

man and whether he followed one or other depended on his own

particular cast of mind, the degree of his will-power, the

strength of his passions and finally, his capacity for

renunciation, righteousness and love. On these qualifications the

upshot would largely depend. But they were not the only factors.

Since gods and demons were part of the world, a man could be

aided or frustrated according as gods or demons chose to

intervene. Life could, in fact, be viewed from two angles. On the

one hand it was one long effort to blend with the

Godhead—an effort which only the individual could make. On

the other hand, it was a war between good and evil, gods and

demons; and to such a contest, God as Vishnu could not remain

indifferent. While the forces of evil might properly be allowed

to test or tax the good, they could never be permitted completely

to win the day. When, therefore, evil appeared to be in the

ascendant, Vishnu intervened and corrected the balance. He took

flesh and entering the world, slew demons, heartened the

righteous and from time to time conferred salvation by directly

exempting individuals from further re-births.

It is these beliefs which govern the Mahabharata epic

and provide the clue to

Krishna's role. Its prime subject is a feud between two families,

a feud which racks and finally destroys them. At the same time,

it is very much more. Prior to the events narrated in the text,

Vishnu has already undergone seven incarnations, taking the forms

of a fish, tortoise, boar and man-lion and later those of Vamana

the dwarf, Parasurama ('Rama with the Axe'), and finally, the

princely Rama. In each of these incarnations he has intervened

and, for the time being, rectified the balance. During the period

covered by the epic, he undergoes an eighth incarnation and it is

in connection with this supremely vital intervention that Krishna

appears.

To understand the character which now unfolds, we must briefly

consider the central story of the Mahabharata. This is

narrated in the most baffling and stupendous detail. Cumbrous

names confront us on every side while digressions and sub-plots

add to the general atmosphere of confusion and complexity. It is

idle to hope that this vast panorama can arouse great interest in

the West and even in India it is unlikely that many would now

approach its gigantic recital with premonitions of delight. It is

rather as a necessary background that its main outlines must be

grasped, for without them Krishna's character and career can

hardly be explained.

The epic begins with two rival families each possessed of a

common ancestor, Kuru, but standing in bitter rivalry to each

other. Kuru is succeeded by his second son, Pandu, and later by

Dhritarashtra, his first son but blind. Pandu has five sons, who

are called Pandavas after him, while Dhritarashtra has a hundred

sons called Kauravas after Kuru, their common grandfather. As

children the two families grow up at the same court, but almost

immediately jealousies arise which are to have a deadly outcome.

Hatred begins when in boyish contests the Pandavas outdo the

Kauravas. The latter resent their arrogance and presently their

father, the blind king, is persuaded to approve a plot by which

the five Pandavas will be killed. They are to sleep in a house

which during the night will be burnt down. The plot, however,

miscarries. The house is burnt, but unbeknown to the Kauravas,

the five brothers escape and taking with them their mother,

Kunti, go for safety to the forest. Here they wander for a while

disguised as Brahmans or priests but reach at last the kingdom of

Panchala. The King of Panchala has a daughter, Draupadi, whose

husband is to be chosen by a public archery competition. Arjuna,

one of the five brothers, wins the contest and gains her as

bride. The Pandavas, however, are polyandrous and thus, on being

married to one brother, Draupadi is also married to the other

four. At the wedding the Pandavas disclose their identities. The Kauravas learn that

they are still alive and in due course are reconciled. They

reinstate the Pandavas and give them half the kingdom. Before

Arjuna, however, can profit from the truce, he infringes by

accident his elder brother's privacy by stumbling on him while he

is with their common wife. As a consequence he violates a

standing agreement and has no alternative but to go into exile

for twelve years. Arjuna leaves the court, visits other lands,

acquires a new wife and makes a new alliance. In other respects,

all is well and the two families look forward to many years of

peaceful co-existence.

The fates, however, seem determined on their destruction. The

leader of the Pandavas is their eldest brother, Yudhisthira. He

conquers many other lands and is encouraged to claim the title,

'ruler of the world.' The claim is made at a great sacrifice

accompanied by a feast. The claim incenses the Kauravas and once

again the ancient feud revives. Themselves expert gamblers, they

challenge Yudhisthira to a contest by dice. Yudhisthira stupidly

agrees and wagering first his kingdom, then his brothers and

finally his wife, loses all and goes again into exile. With him

go the other Pandavas, including Arjuna who has since returned.

For twelve years they roam the forests, brooding on their fate

and planning revenge. When their exile ends, they at once declare

war. Both sides seek allies, efforts at peacemaking are foiled

and the two clash on the battle-field of Kurukshetra. For

eighteen days the battle rages till finally the Pandavas are

victorious. Their success, however, is at an appalling cost.

During the contest all five Pandavas lose their sons. The hundred

sons of their rival, the blind king Dhritarashtra, are dead and

with a sense of tragic futility, the epic ends.

It is as an actor in this tangled drama that Krishna appears.

Alongside the Pandavas and the Kauravas in Northern India is a

powerful people, the Yadavas. They live by grazing cattle but

possess towns including a capital, the city of Dwarka in Western

India. At this capital resides their ruler or king and with him

is a powerful prince, Krishna. This Krishna is related to the

rival families, for his father, Vasudeva, is brother of Kunti,

the Pandavas' mother. From the outset, therefore, he is placed in

intimate proximity to the chief protagonists. For the moment,

however, he himself is not involved and it is only after the

Pandavas have gone into exile and reached the kingdom of Panchala

that he makes his entrance. The occasion is the archery contest

for the hand of Draupadi. Krishna is there as an honoured guest

and when Arjuna makes the winning shot, he immediately recognizes

the five Pandavas as his kinsmen although as refugees they are still

disguised as Brahmans. When the assembled princes angrily protest

at Draupadi's union with a Brahman, and seem about to fight,

Krishna intervenes and persuades them to accept the decision.

Later he secretly meets the Pandavas and sends them wedding

presents. Already, therefore, he is fulfilling a significant

role. He is a powerful leader, a relative of the central figures

and if only because the feud is not his own, he is above the

conflict and to some extent capable of influencing its

outcome.

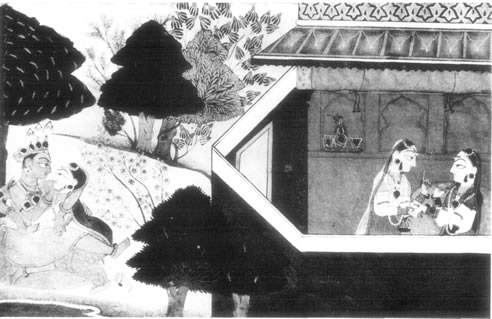

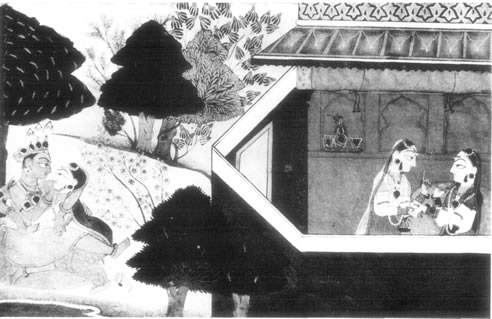

His next appearance brings him closer still to the Pandavas.

When Arjuna is exiled for his breach of marriage etiquette, he

visits Krishna in his city of Dwarka. A great festival is held

and in the course of it Arjuna falls in love with Krishna's

sister, Subhadra. Krishna favours the marriage but advises Arjuna

to marry her by capture. Arjuna does so and by becoming Krishna's

brother-in-law cements still further their relationship.

This friendship has one further consequence, for, after Arjuna

has completed his exile and returned to the Pandava court,

Krishna visits him and the two go into the country for a picnic.

'After a few days, Arjuna said to Krishna, "The summer days have

come. Let us go to the River Jumna, amuse ourselves with some

friends and come back in the evening." Krishna replied, "I would

like that very much. Let us go for a bathe." So Arjuna and

Krishna set out with their friends. Reaching a fine spot fit for

pleasure and overgrown with trees, where several tall houses had

been built, the party went inside. Food and wine, wreaths of

flowers and fragrant perfumes were laid out and at once they

began to frolic at their will. The girls in the party with

delightful rounded haunches, large breasts and handsome eyes

began to flirt as Arjuna and Krishna commanded. Some played about

in the woods, some in the water, some inside the houses. And

Draupadi and Subhadra who were also in the party gave the girls

and women costly dresses and garments. Then some of them began to

dance, some to sing, some laughed and joked, some drank wine. And

the houses and woods, filled with the noise of flutes and drums,

became the very seat of pleasure.'[6]

A little later, Krishna is accorded special status. At the

sacrifice performed by Yudhisthira as 'ruler of the world,' gifts

of honour are distributed. Krishna is among the assembled guests

and is proposed as first recipient. Only one person objects, a

certain king Sisupala, who nurses a standing grievance against

him. A quarrel ensues and during it Krishna kills him. Krishna's

priority is then acclaimed but the incident serves also to

demonstrate his ability as a fighter.

One other aspect of

Krishna's character remains to be noted. Besides being a bold

warrior, he is above all an astute and able ally. During the

Pandavas' final exile in the forest, he urges them to repudiate

their banishment and make war. When the exile is over and war is

near, he acts as peace-maker, urging the Kauravas to make

concessions. When he is foiled by Duryodhana, the blind king's

son, he attempts to have him kidnapped. Finally, once the great

battle is joined, he offers both sides a choice. Each may have

the help either of himself alone or of his immediate kinsmen, the

Vrishnis. The Vrishnis will fight in the battle, while Krishna

himself will merely advise from a distance. The Kauravas choose

the fighters, the Pandavas Krishna. Krishna accordingly aids the

Pandavas with counsel. He accompanies Arjuna as his charioteer

and during the battle is a constant advocate of treachery. As

Kama, a leading Kaurava, fights Arjuna, his chariot gets stuck

and he dismounts to see to it. The rules of war demand that

Arjuna should now break off but Krishna urges him to continue and

Kama is killed unresisting. Similarly when Bhima, one of the five

Pandava brothers, is fighting Duryodhana with his club, Krishna

eggs him on to deal a foul blow. Bhima does so and Duryodhana

dies from a broken thigh. In all these encounters, Krishna shows

himself completely amoral, achieving his ends by the very

audacity of his means.

So far, Krishna's character is merely that of a feudal

magnate, and there is nothing in his views or conduct to suggest

that he is Vishnu or God. Two incidents in the epic, however,

suddenly reveal his true role. The first is when Yudhisthira has

gambled away Draupadi and the Kauravas are intent on her

dishonour. They attempt to make her naked. As one of them tries

to remove her clothes, Draupadi beseeches Krishna as Vishnu to

intervene and save her. Krishna does so and by his help she

remains clothed; however many times her dress is removed. The

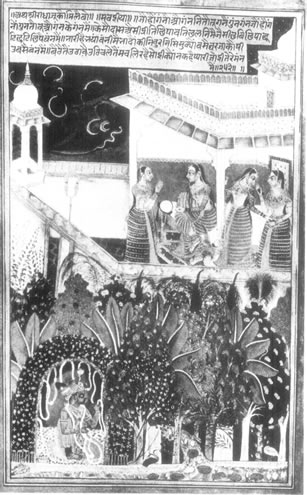

second occasion is on the final battle-field of Kurukshetra.

Arjuna, seeing so many brothers, uncles and cousins ranged on

either side is moved to pity at the senseless nature of the

strife and confides his anguished doubts in Krishna. Krishna

seems, at first, to be only his friend, his brother-in-law and

adviser. He points out that to a warrior nothing is nobler than a

righteous war and declares, 'Do your duty always but without

attachment.' He then advocates the two paths of

yoga(knowledge) and dharma (righteousness). 'Even

if a man falls away from the practice of yoga, he will

still win the heaven of the doers of good deeds and dwell there

many long years. After that, he will be reborn into the home of

pure and prosperous parents. He will then regain that spiritual discernment which he acquired

in his former body; and so he will strive harder than ever for

perfection. Because of his practices in the previous life, he

will be driven on toward union with the Spirit, even in spite of

himself. For the man who has once asked the way to the Spirit

goes farther than any mere fulfiller of the Vedic rituals. By

struggling hard, that yogi will move gradually towards perfection

through many births and reach the highest goal at last[7].

But it is the path of bhakti or devotion to a personal

God which commands Krishna's strongest approval and leads him to

make his startling revelation. 'Have your mind in Me, be devoted

to Me. To Me shall you come. What is true I promise. Dear are you

to Me. They who make Me their supreme object, they to Me are

dear. Though I am the unborn, the changeless Self, I condition my

nature and am born by my power. To save the good and destroy

evildoers, to establish the right, I am born from age to age. He

who knows this when he comes to die is not reborn but comes to

Me.' He speaks, in fact, as Vishnu himself.

This declaration is to prove the vital clue to Krishna's

character. It is to be expanded in later texts and is to account

for the fervour with which he is soon to be adored. For the

present, however, his claim is in the nature of an aside. After

the battle, he resumes his life as a prince and it is more for

his shrewdness as a councillor than his teaching as God that he

is honoured and revered. Yet special majesty surrounds him and

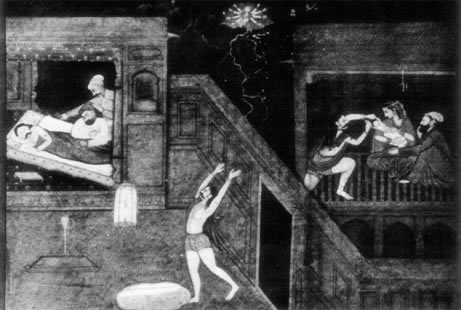

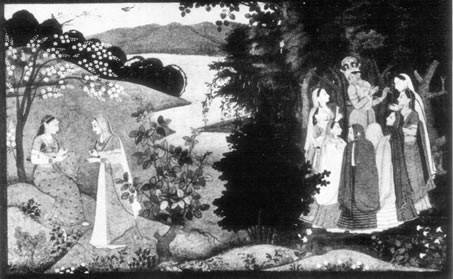

when, thirty-six years after the conflict, a hunter mistakes him

for a deer and kills him by shooting him in the right

foot[8], the Pandavas are inconsolable. They

retreat to the Himalayas, die one by one and are translated to

Indra's heaven[9].

Such an account is obviously a great advance on the

Chandogya Upanishad. Yet, as we ponder its intricate

drama, we are faced with several intractable issues. It is true

that a detailed character has emerged, a figure who is identified

with definite actions and certain clear-cut principles. It is

true also that his character as Vishnu has been asserted. But it

is Krishna the feudal hero who throughout the story takes, by

far, the leading part. Between this hero and Krishna the God,

there is no very clear connection. The circumstances in which

Vishnu has taken form as Krishna are nowhere made plain. Except

on the two occasions mentioned, Krishna is apparently not

recognized as God by others and does not himself claim this

status. Indeed it is virtually only as an afterthought that the

epic is used to transmit his

great sermon, and almost by accident that he becomes the most

significant figure in the story. Even the sermon at first sight

seems at variance with his actions as a councillor—his

repeated recourse to treachery ill consorting with the

paramountcy of duty. In point of fact, such a conflict can be

easily reconciled for if God is supreme, he is above and beyond

morals. He can act in any way he pleases and yet, as God, can

expect and receive the highest reverence. God, in fact, is

superior to ethics. And this viewpoint is, in fact, to prove a

basic assumption in later versions of the story. Here it is

sufficient to note that while the Mahabharata describes

these two contrasting modes of behaviour, no attempt is made to

face the exact issue. Krishna as God has been introduced rather

than explained and we are left with the feeling that much more

than has been recorded remains to be said.

This feeling may well have dogged the writers who put the

Mahabharata into its present shape for, a little later,

possibly during the sixth century A.D., an appendix was added.

This appendix was called the Harivansa or Genealogy of

Krishna[10] and in it were provided all those details

so manifestly wanting in the epic itself. The exact nature of

Krishna is explained—the circumstances of his birth, his

youth and childhood, the whole being welded into a coherent

scheme. In this story Krishna the feudal magnate takes a natural

place but there is no longer any contradiction between his

character as a prince and his character as God. He is, above all,

an incarnation of Vishnu and his immediate purpose is to vanquish

a particular tyrant and hearten the righteous. This viewpoint is

maintained in the Vishnu Purana, another text of about the

sixth century and is developed and illustrated in the tenth and

eleventh books of the Bhagavata Purana. It is this latter

text—a vast compendium of perhaps the ninth or tenth

century—which affords the fullest account in literature of

Krishna's story.

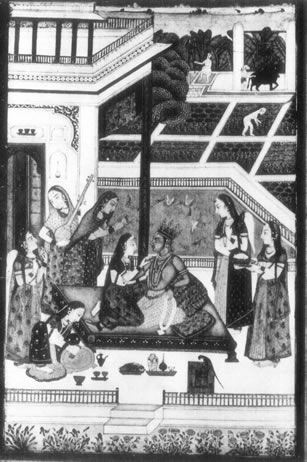

[3] Note 3. [4]

Note 4. [5] A.L. Basham,The

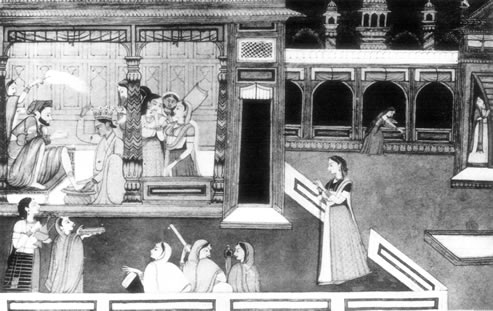

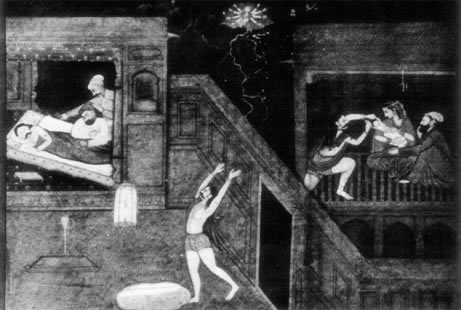

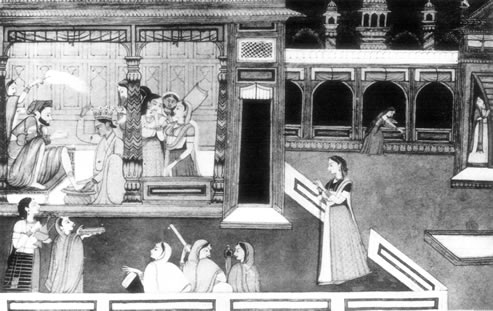

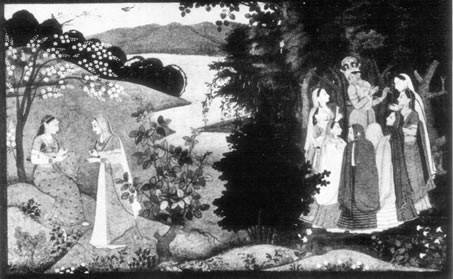

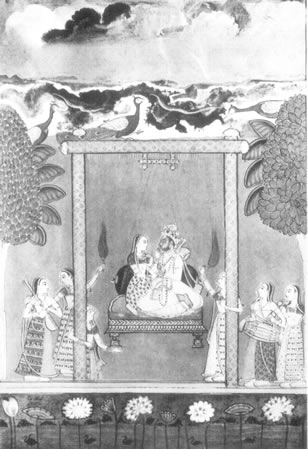

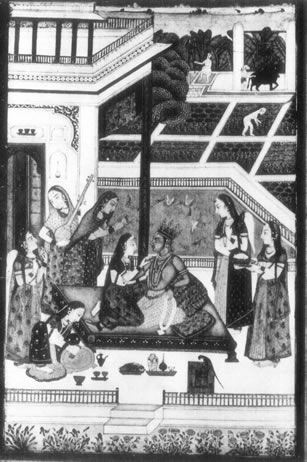

Wonder that was India, 245. [6] Mahabharata,

Adi Parva, Section 224 (Roy, I, 615-16). [7] C. Isherwood

and S. Prabhavananda, The Song of God, Bhagavad-Gita,

86-7. [8] Plate 2. [9]

Note 5. [10] Note 6.

III

THE BHAGAVATA PURANA: THE COWHERD

(i) Birth and Early Adventures

The Bhagavata Purana is couched in the form of a

dialogue between a sage and a king. The king is the successor of

the Pandavas but is doomed to die within a week for having by

accident insulted a holy ascetic. To ensure his salvation, he

spends the week listening to the Bhagavata Purana and

concentrating his mind on Krishna whom he declares to be his

helper.[11]

Book Ten begins by describing the particular situation which

leads to Krishna's birth. The scene is Mathura, a town in

northern India, adjoining the kingdom of the Kauravas. The

surrounding country is known as Braj and its ruling families are

the Yadavas. Just outside Mathura is the district of Gokula which

is inhabited by cowherds. These are on friendly terms with the

Yadavas, but are inferior to them in caste and status. The time

is some fifty years or more before the battle of Kurukshetra and

the ruling king is Ugrasena. Ugrasena's queen is Pavanarekha and

a mishap to her sets in train a series of momentous events.

One day she is taking the air in a park, when she misses her

way and finds herself alone. A demon, Drumalika, is passing and,

entranced by her grace, decides to ravish her. He takes the form

of her husband, Ugrasena, and despite Pavanarekha's protests

proceeds to enjoy her. Afterwards he assumes his true shape.

Pavanarekha is dismayed but the demon tells her that he has given

her a son who will 'vanquish the nine divisions of the earth,

rule supreme and fight Krishna.' Pavanarekha tells her maids that

a monkey has been troubling her. Ten months later a son is born.

He is named Kansa and the court rejoices.

As Kansa grows up he reveals his demon's nature. He ignores

his father's words, murders children and defeats in battle King

Jarasandha of Magadha.[12] The latter

gives him two daughters in marriage. He then deposes his father,

throws him into prison, assumes his powers and bans the worship

of Vishnu. As his crimes increase, he extends his conquests. At last Earth can bear the

burden no longer and appeals to the gods to approach the supreme

Deity, Brahma, to rid her of the load. Brahma as Creator can

hardly do this, but Vishnu as Preserver agrees to intervene and

plans are laid. Among the Yadava nobility are two upright

persons. The first is Devaka, the younger brother of King

Ugrasena and thus an uncle to the tyrant. The second is a certain

Vasudeva. Devaka has six daughters, all of whom he marries to

Vasudeva. The seventh is called Devaki. Vishnu announces that

Devaki will also be married to Vasudeva, and plucking out two of

his hairs—one black and one white—he declares that

these will be the means by which he will ease Earth's burden. The

white hair is part of Sesha, the great serpent, which is itself a

part of Vishnu and this will be impersonated as Devaki's seventh

child. The black hair is Vishnu's own self which will be

impersonated as Devaki's eighth child. The child from the white

hair will be known as Balarama and the child from the black hair

as Krishna. As Krishna, Vishnu will then kill Kansa. Earth is

gratified and retires and the stage is set for Krishna's

coming.

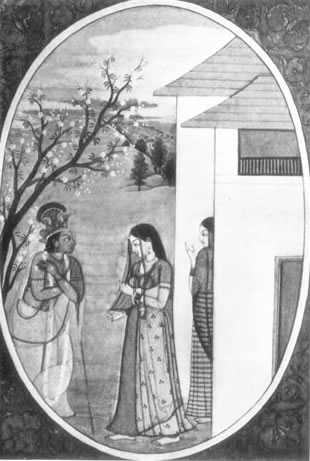

Devaki, with Kansa's approval, is now married to Vasudeva. The

wedding is being celebrated in the grandest manner when a voice

from heaven is heard saying, 'Kansa, the eighth son of her whom

you are now escorting will cause your destruction. You shall die

at his hand.' Kansa is greatly alarmed and is about to slay

Devaki when Vasudeva agrees to yield him all their sons. Kansa

accordingly spares her. Each of Devaki's first six sons, however,

is delivered up at birth and each is slaughtered.

As the time for fulfilling the prophecy approaches, Kansa

grows fearful. He learns that gods and goddesses are being born

as cowherds and cowgirls and, interpreting this as a sign that

Krishna's birth is near, he commands his men to slaughter every

cowherd in the city. A great round-up ensues and many cowherds

are killed. The leading cowherd is a wealthy herdsman named

Nanda, who lives with his wife Yasoda in the country district of

Gokula. Although of lower caste, he is Vasudeva's chief friend

and in view of the imminent dangers confronting his family, it is

to Nanda that Vasudeva now sends one of his other wives, Rohini.

Devaki has meanwhile conceived her seventh son, the white hair of

Vishnu, and soon to be recognized as Krishna's brother. To avoid

his murder by Kansa, Vishnu has the foetus transferred from

Devaki's womb to that of Rohini, and the child, named Balarama,

is born to Rohini, Kansa being informed that Devaki has

miscarried. The eighth pregnancy now occurs. Kansa increases his

precautions. Devaki and Vasudeva are handcuffed and manacled. Guards are

mounted and besides these, elephants, lions and dogs are placed

outside. The unborn child, however, tells them not to fear and

Devaki and Vasudeva compose their minds.

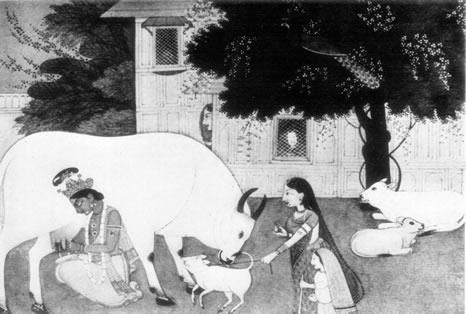

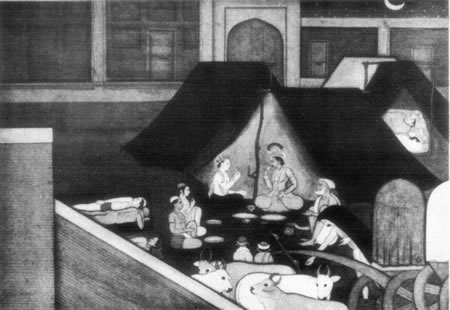

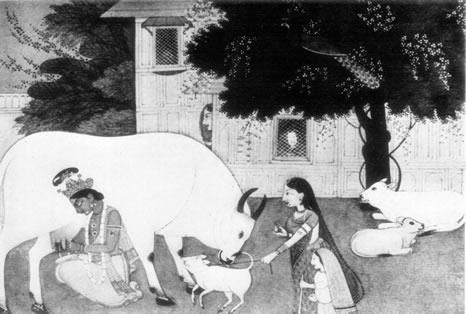

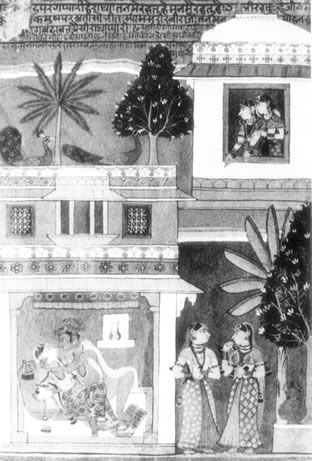

Krishna is now born, dark as a cloud and with eyes like

lotuses. He is clad in a yellow vest and wears a crown. He takes

the form of Vishnu and commands Vasudeva to bear him to Nanda's

house in Gokula and substitute him for the infant daughter who

has just been born to Yasoda, Nanda's wife. Devaki and Vasudeva

worship him. The vision then fades and they discover the new-born

child crying at their side. They debate what to do—Devaki

urging Vasudeva to take the baby to Nanda's house where Rohini,

his other wife, is still living and where Yasoda will receive it.

Vasudeva is wondering how to escape when his handcuffs and chains

fall off, the doors open and the guards are seen to be asleep.

Placing Krishna in a basket, he puts it on his head and sets out

for Gokula. As he goes, lions roar, the rain pours down and the

river Jumna faces him. There is no help but to ford it and

Vasudeva accordingly enters the stream. The water gets higher and

higher until it reaches his nose. When he can go no farther, the

infant Krishna stretches out a foot, calms the river and the

water subsides. Vasudeva now arrives at Nanda's house where he

finds that Yasoda has borne a girl and is in a trance. Vasudeva

puts Krishna beside her, takes up the baby girl, recrosses the

river and joins Devaki in her prison. The doors shut, the

handcuffs and fetters close on them again and as the baby starts

to cry, the guards awake. A sentry then carries Kansa the news.

Kansa hurries to the spot, seizes the child and tries to dash it

on a stone. As he does so the child becomes the goddess Devi and

exclaiming that Kansa's enemy is born elsewhere and nothing can

save him, vanishes into heaven.[13] Kansa is

greatly shaken and orders all male children to be killed,[14] but releases Vasudeva and Devaki.

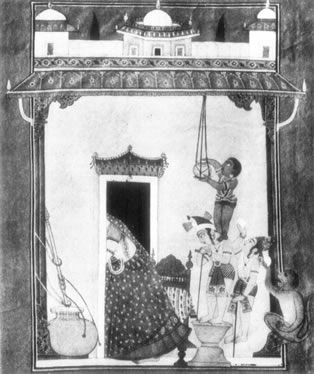

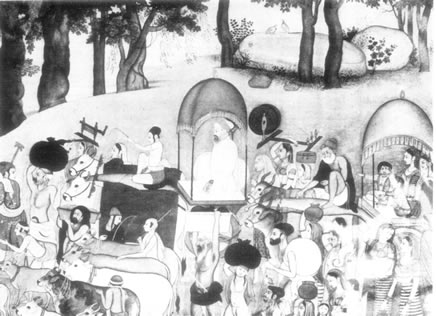

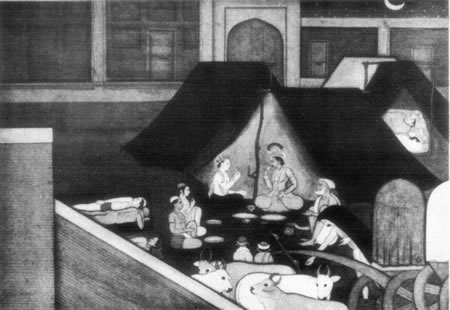

Meanwhile Nanda, the rich herdsman, is celebrating the birth.

Pandits and astrologers are sent for, the child's horoscope is

cast and his destiny foretold. He will be a second deity like

Brahma himself. He will destroy demons, relieve the land of Braj

of all its cares, be called the lord of the cowgirls and be

praised the whole world over. Nanda promises to dedicate cows,

loads the Brahmans with presents, and summons all the musicians

and singers of the city. Singing, dancing and music break forth,

the courtyards throng with people, and the cowherds of Gokula

come in with their wives. On their heads are pitchers full of

curd and as a magical means of ensuring prosperity, they proceed to throw it over the

gathering. Nanda presents them with cloth and betel and they

depart elated at the news.

Some days later Nanda learns of Kansa's order to seize all

male children and, deeming it prudent to offer presents, he

collects the cowherds in a body and goes to Mathura to pay

tribute. Kansa receives him and on his way back Vasudeva meets

him at the river. He dare not disclose his secret that Krishna is

not Nanda's son but his own. At the same time he cannot suppress

his anxiety as a father. He contents himself by telling Nanda

that demons and evil spirits are abroad seeking to destroy young

children and urges him to return to Gokula as quickly as

possible.

The Purana now concentrates on two main themes: on

Krishna's infancy in Gokula, dilating on his baby pranks, his

capacity for mischief, the love he arouses in the hearts of his

foster-mother, Yasoda, and of all the married cowgirls and,

secondly, on his supernatural powers and skill in ridding the

country of troublesome demons. These are at first shown as

hostile to Krishna only, but as the story unfolds, his role

gradually widens and we see him acting as the cowherds' ally,

protecting them from harm, attacking the forces of evil and thus

fulfilling the supreme purpose for which he has been born. From

time to time the cowherds realize that Krishna is Vishnu and

adore him as God. Then amnesia intervenes. They retain no

recollection of the vision and see him simply as a youthful

cowherd, charming in manner, whose skill in slaying demons

arouses their love. In this way Krishna lives among them—in

fact, God, but in the eyes of the people, a young boy.[15]

The first demon to threaten Krishna's life is a huge ogress

named Putana. Her role is that of child-killer—any child

who is suckled in the night by Putana instantly dying. Putana

assumes the form of a sweet and charming girl, dabs her breasts

with poison and while Nanda is still at Mathura, comes gaily to

his house. Entranced by her appearance, Yasoda allows her to hold

the baby Krishna and then to suckle him. Krishna, however, is

impervious to the poison, and fastening his mouth to her breast,

he begins to suck her life out with the milk. Putana, feeling her

life going, rushes wildly from the village, but to no avail.

Krishna continues sucking and the ogress dies. When Yasoda and

Rohini catch up with her, they find her huge carcass lying on the

ground with Krishna still sucking her breast. 'Taking him up

quickly and kissing him, they pressed him to their bosoms and

hurried home.'

Nanda now arrives from

Mathura and congratulates the cowherds on their escape—so

great was Putana's size that her body might have crushed and

overwhelmed the whole colony. He then arranges for her burning

but as her flesh is being consumed, a strange perfume is noticed

for Krishna, when killing her, had granted her salvation.

A second demon now intervenes. It is twenty-seven days since

Krishna's birth. Brahmans and cowherds have been summoned to a

feast, the cowgirls are singing songs and everyone is laughing

and eating. Krishna for the time being is out of their minds,

having been put to sleep beneath a heavy cart loaded with

pitchers. A little later he wakes up, begins to cry for the

breast and finding no one there wriggles about and starts to suck

a toe. At this moment the demon, Saktasura, is flying through the

sky. He notices the child and alights on the cart. His weight

cracks it but before the cart can collapse, Krishna kicks out so

sharply that the demon dies and the cart falls to pieces. Hearing

a great crash, the cowgirls dash to the spot, marvelling that

although the cart is in splinters and all the pots broken,

Krishna has survived.

The third attack occurs when Krishna is five months old.

Yasoda is sitting with him in her lap when she notices that he

has suddenly become very heavy. At the same time, the whirlwind

demon, Trinavarta, raises a great storm. The sky darkens, trees

are uprooted and thatch dislodged. As Yasoda sets Krishna down,

Trinavarta seizes him and whirls him into the air. Yasoda finds

him suddenly gone and calls out, 'Krishna, Krishna.' The cowgirls

and cowherds join her in the search, peering for him in the gusty

gloom of the dark storm. Full of misery, they search the forest

and can find him nowhere. Krishna, riding through the air,

however, can see their distress. He twists Trinavarta round,

forces him down and dashes him to death against a stone. As he

does so, the storm lightens, the wind drops and the cowherds and

cowgirls regain their homes. There they discover a demon lying

dead with Krishna playing on its chest. Filled with relief,

Yasoda picks him up and hugs him to her breast.

Vasudeva now instructs his family priest, Garga the sage, to

go to Gokula, meet Nanda and give Krishna and Balarama proper

names. Rohini, he points out, has had a son, Balarama, and Nanda

has also had a son, Krishna. It is time that each should be

formally named. The sage is delighted to receive the commission

and on arriving is warmly welcomed. He declines, however, to

announce the children's names in public, fearing that his

connection with Vasudeva will cause Raja Kansa to connect Krishna with the eighth

child—his fated enemy. Nanda accordingly takes him inside

his house and there the sage names the two children. Balarama is

given seven names, but Krishna's names, he declares, are

numberless. Since, however, Krishna was once born in Vasudeva's

house, he is called Vasudeva. As to their qualities, the sage

goes on, both are gods. It is impossible to understand their

state, but having killed Kansa, they will remove the burdens of

the world. He then goes silently away. This is the first time

that Nanda and Yasoda are told the true facts of Krishna's birth.

They do not, however, make any comment and for the time being it

is as if they are still quite ignorant of Krishna's destiny. They

continue to treat him as their son and no hint escapes them of

his true identity.

Meanwhile Krishna, along with Rohini's son, Balarama, is

growing up as a baby. He crawls about the courtyard, lisps his

words, plays with toys and pulls the calves' tails, Yasoda and

Rohini all the time showering upon him their doting love. When he

can walk, Krishna starts to go about with other children and

there then ensues a series of naughty pranks. His favourite

pastime is to raid the houses of the cowgirls, pilfer their cream

and curds, steal butter and upset milk pails. When, as sometimes

happens, the butter is hung from the roof, they pile up some of

the household furniture. One of the boys then mounts upon it,

another climbs on his shoulders, and in this way gets the butter

down.[16] As the pilfering increases, the married

cowgirls learn that Krishna is the ringleader and contrive one

day to catch him in the act. 'You little thief,' they say, 'At

last we've caught you. So it's you who took our butter and curds.

You won't escape us now.' And taking him by the hand they march

him to Yasoda. Krishna, however, is not to be outwitted.

Employing his supernatural powers, he substitutes the cowgirls'

own sons for himself and while they go to Yasoda, himself slips

off and joins his playmates in the fields. When the cowgirls

reach Yasoda, they complain of Krishna's thefts and tell her that

at last they have caught him and here he is. Yasoda answers, 'But

this is not Krishna. These are your own sons.' The cowgirls look

at the children, discover the trick, are covered in confusion and

burst out laughing. Yasoda then sends for Krishna and forbids him

to steal from other people's houses. Krishna pretends to be

highly indignant. He calls the cowgirls liars and accuses them of

always making him do their work. If he is not having to hold a

milk pail or a calf, he says, he is doing a household chore or

even keeping watch for them while they neglect their work and gossip. The cowgirls listen in

astonishment and go away.

Another day Krishna is playing in a courtyard and takes it

into his head to eat some dirt. Yasoda is told of it and in a fit

of anger runs towards him with a stick. 'Why are you eating mud?'

she cries. 'What mud?' says Krishna. 'The mud one of your friends

has just told me you have eaten. If you haven't eaten it, open

your mouth.' Krishna opens it and looking inside, Yasoda sees the

three worlds. In a moment of perception, she realizes that

Krishna is God. 'What am I doing in looking upon the Lord of the

three worlds as my son?' she cries. Then the vision fades and she

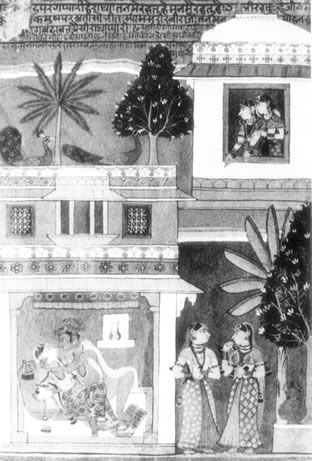

picks up Krishna and kisses him.

Another day, Yasoda asks the married cowgirls to assist her in

churning milk. They clean the house, set up a large vessel,

prepare the churning staff and string, and start to churn.

Krishna is awakened by the noise and finding no one about comes

crying to Yasoda. 'I am hungry, mother,' he says. 'Why have you

not given me anything to eat?' And in a fit of petulance he

starts to throw the butter about and kick over the pitchers.

Yasoda tells him not to be so naughty, sits him on her lap and

gives him some milk. While she is doing this, a cowgirl tells her

that the milk has boiled over and Yasoda jumps up leaving Krishna

alone. While she is away he breaks the pots, scatters the curds,

makes a mess of all the rooms and, taking a pot full of butter,

runs away with it into the fields. There he seats himself on an

upturned mortar, assembles the other boys and vastly pleased with

himself, laughingly shares the butter out. When Yasoda returns

and sees the mess, she seizes a stick and goes to look for

Krishna. She cannot find it in her heart, however, to be angry

for long and when Krishna says, 'Mother, let me go. I did not do

it,' she laughs and throws the stick away. Then pretending to be

still very angry, she takes him home and ties him to a mortar. A

little later a great crash is heard. Two huge trees have fallen

and when the cowherds hurry to the spot, they find that Krishna

has dragged the mortar between the trunks, pulled them down and

is quietly sitting between them.[17] Two

youths—by name Nala and Kuvara—have been imprisoned

in the trees and Krishna's action has released them. When she

sees that Krishna is safe, Yasoda unties him from the mortar and

hugs him to her.

This incident of the trees now forces Nanda to make a

decision. The various happenings have been profoundly unnerving

and he feels that it is no longer safe to stay in Gokula. He

decides therefore to move a

day's march farther on, to cross the river and settle in the

forests of Brindaban. The cowherds accordingly load up their

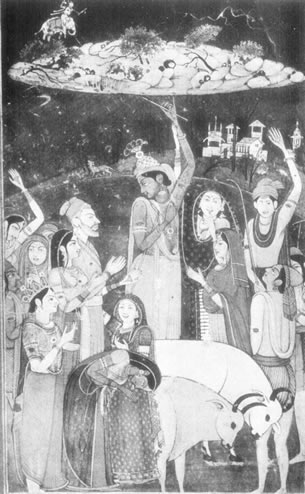

possessions on carts and the move ensues.[18]

The story now enters its second phase. Krishna is no longer a

mischievous baby, indulging in tantrums yet wringing the heart

with his childish antics. He is now five years old and of an age

to make himself useful. He asks to be allowed to graze the

calves. At first Yasoda is unwilling. 'We have got so many

servants,' she says. 'It is their job to take the calves out. Why

go yourself? You are the protection of my eye-lids and dearer to

me than my eyes.' Krishna, however, insists and in the end she

entrusts him and Balarama to the other young cowherds, telling

them on no account to leave them alone in the forest, but to

bring them safely home. Her words are, in fact, only too

necessary, for Kansa, the tyrant king, is still in quest of the

child who is to kill him. His demon minions are still on the

alert, attacking any likely boy, and as Krishna plays with the

cowherds and tends the calves, he suffers a further series of

attacks.

A cow demon, Vatsasura, tries to mingle with the herd. The

calves sense its presence and as it sidles up, Krishna seizes it

by the hind leg, whirls it round his head and dashes it to death.

A crane demon, Bakasura, then approaches. The cowherds recognize

it, but while they are wondering how to escape, the crane opens

its beak and engulfs Krishna. Krishna, however, becomes so hot

that the crane cannot retain him. It lets him go. Krishna then

tears its beak in two, rounds up the calves and taking the

cowherd boys with him, returns home.

Another day Krishna is out in the forest with the cowherds and

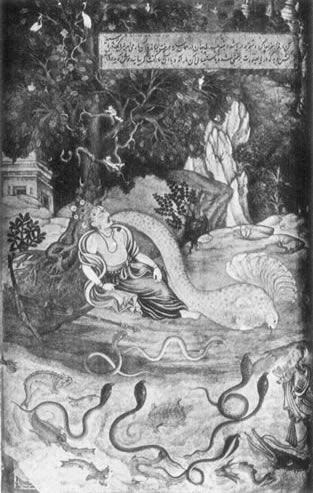

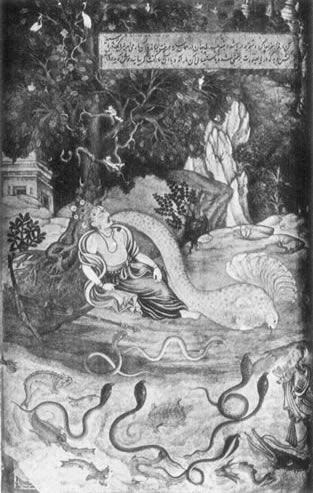

the calves, when a snake demon, Ugrasura, sucks them into its

mouth. Krishna expands his body to such an extent that the snake

bursts. The calves and cowherd children come tumbling out and all

praise Krishna for saving them. On the way back, Krishna suggests

that they should have a picnic and choosing a great kadam

tree, they sweep the place clean, set out their food and proceed

to enjoy it. As they eat, the gods look down, noting how handsome

the young Krishna has grown. Among the gods is Brahma, who

decides to tease Krishna by hiding the calves while the cowherd

children are eating.[19] He takes them

to a cave and when Krishna goes in search of them, hides the

cowherd children as well. Krishna, however, is not to be

deterred. Creating duplicates of every calf and boy he brings

them home. No one detects that anything is wrong and for a year

they live as if nothing has

happened. Brahma has meanwhile sunk himself in meditation, but

suddenly recalls his prank and hurries out to set matters right.

He is astonished to find the original calves and children still

sleeping in the cave, while their counterparts roam the forest.

He humbly worships Krishna, restores the original calves and

children and returns to his abode. When the cowherd children

awake, Krishna shows them the calves. No one realizes what has

happened. The picnic continues and laughing and playing they go

home.

We now enter the third phase of Krishna's childhood. He is

eight years old and is therefore competent to graze not merely

the calves but the cows as well.[20] Nanda

accordingly performs the necessary ritual and Krishna goes with

the cowherds to the forest.

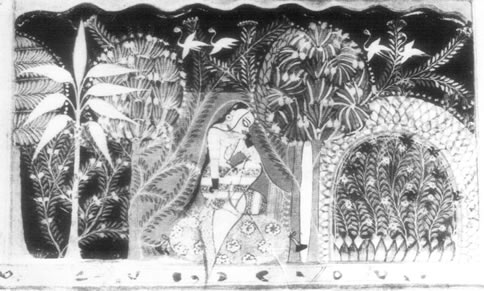

An idyllic phase in Krishna's life now starts. 'At this time

Krishna and Balarama, accompanied by the cow-boys, traversed the

forests, that echoed with the hum of bees and the peacock's cry.

Sometimes they sang in chorus or danced together; sometimes they

sought shelter from the cold beneath the trees; sometimes they

decorated themselves with flowery garlands, sometimes with

peacocks' feathers; sometimes they stained themselves of various

hues with the minerals of the mountain; sometimes weary they

reposed on beds of leaves, and sometimes imitated in mirth the

muttering of the thundercloud; sometimes they excited their

juvenile associates to sing, and sometimes they mimicked the cry

of the peacock with their pipes. In this manner participating in

various feelings and emotions, and affectionately attached to

each other, they wandered, sporting and happy, through the wood.

At eveningtide came Krishna and Balarama, like to cowboys, along

with the cows and the cowherds. At eveningtide the two immortals,

having come to the cow-pens, joined heartily in whatever sports

amused the sons of the herdsmen.'[21]

One day as they are grazing the cows, they play a game.

Krishna divides the cows and cowherds into two sides and

collecting flowers and fruits pretends that they are weapons.

They then stage a mock battle, pelting each other with the

fruits. A little later Balarama takes them to a grove of palm

trees. The ass demon, Dhenuka, guards it. Balarama, however,

seizes it by its hind legs, twists it round and hurls it into a

high tree. From the tree the demon falls down dead. When

Dhenuka's companion asses hasten to the spot, Krishna kills them

also. The cowherds then pick the coconuts to their hearts'

content, fill a quantity of baskets and having grazed the cows,

go strolling home.

The next morning Krishna

rises early, calls the cowherds and takes the cows to the forest.

As they are grazing them by the Jumna, they reach a dangerous

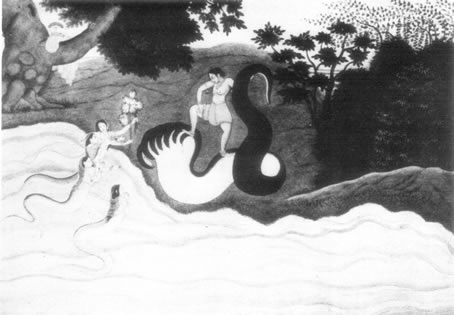

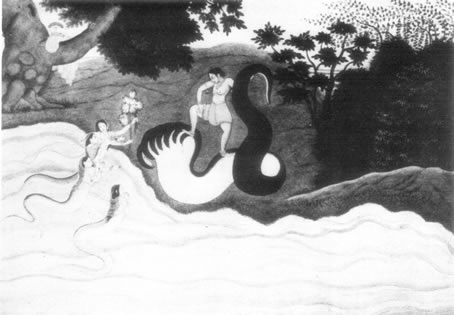

whirlpool. In this whirlpool lives the giant snake, Kaliya, whose

poison has befouled the water, curdling it into a great froth.

The cowherds and the cattle drink some of it, are taken ill, but

revive at Krishna's glance. They then play ball. A solitary

kadam tree is on the bank. Krishna climbs it and a cowherd

throws the ball up to him. The ball goes into the water and

Krishna, thinking this the moment for quelling the great snake,

plunges in after it. Kaliya detects that an intruder has entered

the pool, begins to spout poison and fire and encircles Krishna

in its coils. In their alarm the cowherds send word to Nanda and

along with Yasoda, Rohini and the other cowgirls, he hastens to

the scene. Krishna can no longer be seen and in her agitation

Yasoda is about to throw herself in. Krishna, however, is merely

playing with the snake. In a moment he expands his body, jumps

from the coils and begins to dance on the snake's heads. 'Having

the weight of three worlds,' the Purana says, 'Krishna was

very heavy.' The snake fails to sustain this dancing burden, its

heads droop and blood flows from its tongues. It is about to die

when the snake-queens bow at Krishna's feet and implore his

mercy. Krishna relents, spares the snake's life but banishes it

to a distant island.[22] He then leaves

the river, but the exhaustion of the cowherds and cowgirls is so

great that they decide to stay in the forest for the night and

return to Brindaban next morning. Their trials, however, are far

from over. At midnight there is a heavy storm and a huge

conflagration. Scarlet flames leap up, dense smoke engulfs the

forest and many cattle are burnt alive. Finding themselves in

great danger, Nanda, Yasoda and the cowherds call on Krishna to

save them. Krishna quietly rises up, sucks the fire into his

mouth and ends the blaze.

The hot weather now comes. Trees are heavy with blossom,

peacocks strut in the glades and a general lethargy seizes the

cowherds. One day Krishna and his friends are out with the cattle

when Pralamba, a demon in human form, comes to join them. Krishna

warns Balarama of the demon's presence and tells him to await an

opportunity to kill him. He then divides the cowherds into two

groups and starts them on the game of guessing fruits and

flowers. Krishna's side loses and as a penalty they have to run a

certain distance carrying Balarama's side on their shoulders.

Pralamba carries Balarama. He runs so fast that he quickly

outstrips the others. As he reaches the forest, he changes size,

becoming 'large as a black

hill.' He is about to kill Balarama when Balarama himself rains

blows upon him and kills him instead.[23] While this is

happening, the cows get lost, another forest fire ensues and

Krishna has once again to intervene. He extinguishes the fire,

regains the cattle and escorts the cowherds to their

homes.[24] When the others hear what has happened,

they are filled with wonder 'but obtain no clue to the actions of

Krishna.'

During all this time, Krishna as 'son' of the wealthiest and

most influential cowherd, Nanda, has been readily accepted by the

cowherd children as their natural leader. His lack of fear, his

bravery in coping with demons, his resourcefulness in extricating

the cowherds from awkward situations, his complete

self-confidence and finally his princely bearing have revealed

him as someone altogether above the ordinary. From time to time

he has disclosed his true nature as Vishnu but almost immediately

has exercised his 'illusory' power and prevented the cowherds

from remembering it. He has consequently lived among them as God

but their love and admiration are still for him as a boy. It is

at this point that the Purana now moves to what is perhaps

its most significant phase—a description of Krishna's

effects on the cowgirls.

[11]

[12]

Magadha—a region corresponding to present-day South

Bihar.

[13]

[14]

[15]

[16]

[17]

[18]

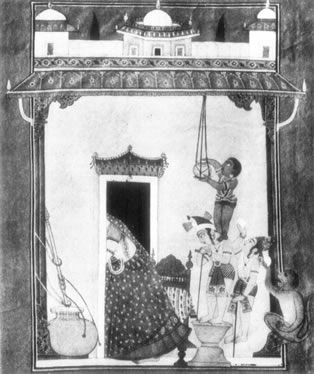

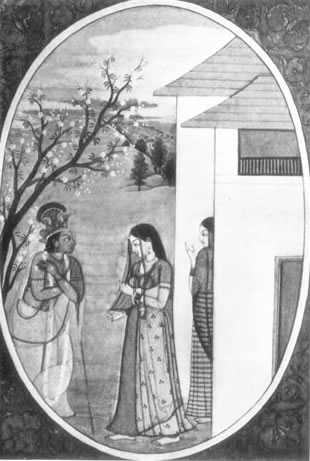

Plate 6. In the Harivansa, the cause

of the migration is given as a dangerous influx of wolves.

[19]

[20]

[21]

[22]

[23]

[24]

(ii) The Loves of the Cowgirls

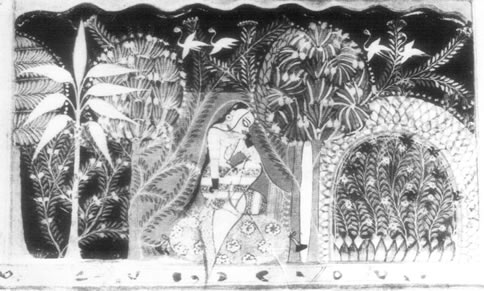

We have seen how during his infancy Krishna's pranks have

already made him the darling of the women. As he grows up, he

acquires a more adult charm. In years he is still a boy but we

are suddenly confronted with what is to prove the very heart of

the story—his romances with the cowgirls. Although all of

them are married, the cowgirls find his presence irresistible and

despite the warnings of morality and the existence of their

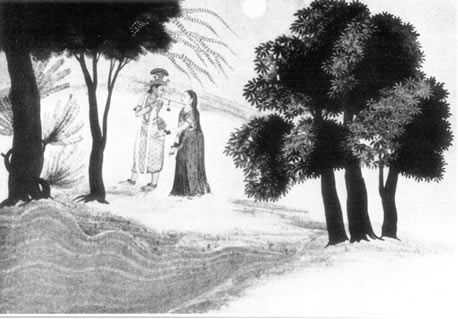

husbands, each falls utterly in love with him. As Krishna wanders

in the forest, the cowgirls can talk of nothing but his charms.

They do their work but their thoughts are on him. They stay at

home but all the time each is filled with desperate longing. One

day Krishna plays on his flute in the forest. Playing the flute

is the cowherds' special art and Krishna has, therefore, learnt

it in his childhood. But, as in everything else, his skill is

quite exceptional and Krishna's playing has thus a beauty all its

own. From where they are working the cowgirls hear it and at once

are plunged in agitation. They gather on the road and say to each

other, 'Krishna is dancing and singing in the forest and will not

be home till evening. Only then shall we see him and be

happy.'

One cowgirl says, 'That

happy flute to be played on by Krishna! Little wonder that having

drunk the nectar of his lips the flute should trill like the

clouds. Alas! Krishna's flute is dearer to him than we are for he

keeps it with him night and day. The flute is our rival. Never is

Krishna parted from it.' A second cowgirl speaks. 'It is because

the flute continually thought of Krishna that it gained this

bliss.' And a third says, 'Oh! why has Krishna not made us into

flutes that we might stay with him day and night?' The situation

in fact has changed overnight for far from merely appealing to

the cowgirls' maternal instincts, Krishna is now the darling

object of their most intense passion.

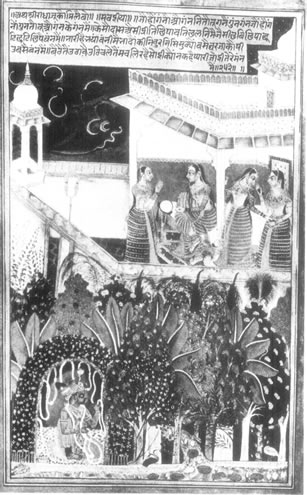

Faced with this situation, the cowgirls discuss how best to

gain Krishna as their lover. They recall that bathing in the

early winter is believed to wipe out sin and fulfil the heart's

desires. They accordingly go to the river Jumna, bathe in its

waters and after making clay images of Parvati, Siva's consort,

pray to her to make Krishna theirs. They go on doing this for

many days.

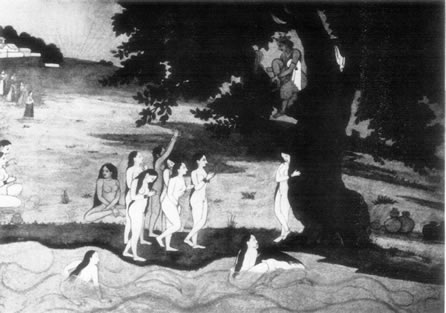

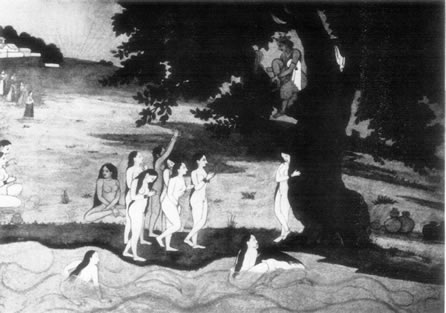

One day they choose a part of the river where there is a steep

bank. Taking off their clothes they leave them on the grass

verge, enter the water and swim around calling out their love for

Krishna. Unknown to them, Krishna is in the vicinity and is

grazing the cows. He steals quietly up, sees them in the river,

makes their clothes into a bundle and then climbs up with it into

a tree. When the cowgirls come out of the water, they cannot find

their clothes until at last one of them spies Krishna sitting in

the tree. The cowgirls hurriedly squat down in the water

entreating Krishna to return their clothes. Krishna, however,

tells them to come up out of the water and ask him one by one.

The cowgirls say, 'But this will make us naked. You are making an

end of our friendship.' Krishna says, 'Then you shall not have

your clothes back.' The cowgirls answer, 'Why do you treat us so?

It is only for you that we have bathed all these days.' Krishna

answers, 'If that is really so, then do not be bashful or deceive

me. Come and take your clothes.' Finding no alternative, the

cowgirls argue amongst themselves that since Krishna already

knows the secrets of their minds and bodies, there is no point in

being ashamed before him, and they come up out of the water

shielding their nakedness with their hands.[25] Krishna

tells them to raise their hands and then he will return their

clothes. The cowgirls do so begging him not to make fun of them

and to give them at least something in return. Krishna now hands

the clothes back giving as excuse for his conduct the following

somewhat specious reason. 'I

was only giving you a lesson,' he says. 'The god Varuna lives in

water, so if anyone goes naked into it he loses his character.

This was a secret, but now you know it.' Then he relents. 'I have

told you this because of your love. Go home now but come back in

the early autumn and we will dance together.' Hearing this the

cowgirls put on their clothes and wild with love return to their

village.

At this point the cowgirls' love for Krishna is clearly

physical. Although precocious in his handling of the situation,

Krishna is still the rich herdsman's handsome son and it is as

this rather than as God that they regard him. Yet the position is

never wholly free from doubt for in loving Krishna as a youth, it

is as if they are from time to time aware of adoring him as God.

No precise identifications are made and yet so strong are their

passions that seemingly only God himself could evoke them. And

although no definite explanation is offered, it is perhaps this

same idea which underlies the following incident.

One day Krishna is in the forest when his cowherd companions

complain of feeling hungry. Krishna observes smoke rising from

the direction of Mathura and infers that the Brahmans are cooking

food preparatory to making sacrifice. He asks the cowherds to

tell them that Krishna is hungry and would like some of this

food. The Brahmans of Mathura angrily spurn the request, saying

'Who but a low cowherd would ask for food in the midst of a

sacrifice?' 'Go and ask their wives,' Krishna says, 'for being

kind and virtuous they will surely give you some.' Krishna's

power with women is then demonstrated once more. His fame as a

stealer of hearts has preceded him and the cowherds have only to

mention his name for the wives of the Brahmans to run to serve

him. They bring out gold dishes, load them with food, brush their

husbands aside and hurry to the forest. One husband stops his

wife, but rather than be left behind the woman leaves her body

and reaches Krishna before the others. When the women arrive they

marvel at Krishna's beauty. 'He is Nanda's son,' they say. 'We

heard his name and everything else was driven from our minds. Let

us gaze on this darling object of our lives. O Krishna, it is due

to you that we have seen you and thus got rid of all our sins.

Those stupid Brahmans, our husbands, mistook you for a mere man.

But you are God. As God they offer to you prayers, penance,

sacrifice and love. How then can they deny you food?' Krishna

replies that they should not worship him for he is only the child

of the cowherd, Nanda. He was hungry and they took pity on him,

and he only regrets that being far from home he cannot return their hospitality. They must

now go home as their presence is needed for the sacrifices and

their husbands must still be waiting. So cool an answer dismays

the women and they say, 'Great king, we loved your lotus-like

face. We came to you despite our families. They tried to stop us

but we ignored them. If they do not take us back, where shall we

go? And one of us, prevented by her husband, gave her life rather

than not see you.' At this Krishna smiles, reveals the woman and

says, 'Whoever loves God never dies. She was here before you.'

Krishna then eats the food and assuring them that their husbands

will say nothing, sends them back to Mathura. When they arrive,

they find the Brahmans chastened and contrite—cursing their

folly in having failed to recognize Krishna as God and envious of

their wives for having seen him and given him food.

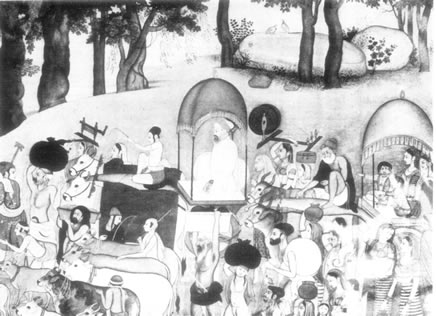

Having humbled the Brahmans, Krishna now turns to the gods,

choosing Indra, their chief, for attack. The moment is his annual

worship when the cowherds offer sweets, rice, saffron, sandal and

incense. Seeing them busy, Krishna asks Nanda what is the point

of all their preparations. What good can Indra really do? he

asks. He is only a god, not God himself. He is often worsted by

demons and abjectly put to flight. In fact he has no power at

all. Men prosper because of their virtues or their fates, not

because of Indra. As cowherds, their business is to carry on

agriculture and trade and to tend cows and Brahmans. Their

earliest books, the Vedas, require them not to abandon their

family customs and Krishna then cites as an ancient practice the

custom of placating the spirits of the forests and hills. This

custom, he says, they have wrongly superseded in favour of Indra

and they must now revive it. Nanda sees the force of Krishna's

remarks and holds a meeting. 'Do not brush aside his words as

those of a mere boy,' he says. 'If we face the facts, we have

really nothing to do with the ruler of the gods. It is on the

forests, rivers and the great hill, Govardhana, that we really

depend.' The cowherds applaud this advice, resolve to abandon the

gods and in their place to worship the mountain, Govardhana. The

worship of the hill is then performed. Krishna advises the

cowherds to shut their eyes and the spirit of the hill will then

show itself. He then assumes the spirit's form himself, telling

Nanda and the cowherds that in response to their worship the

mountain spirit has appeared. The cowherds' eyes are easily

deceived. Beholding, as they think, Govardhana himself, they make

offerings and go rejoicing home.

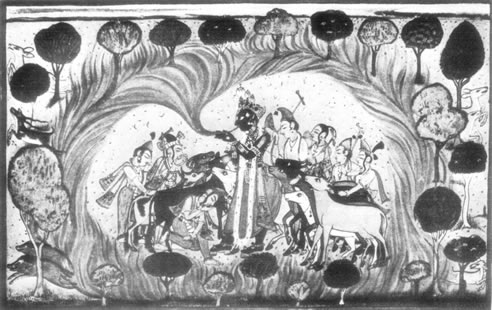

Such an act of defiance greatly enrages Indra and he assembles

all the gods. He forgets that earlier in the story it was the

gods themselves who begged Vishnu to be born on earth and that

many of their number have even

taken birth as cowherds and cowgirls in order to delight in

Krishna as his incarnation. Instead he sees Krishna as 'a great

talker, a silly unintelligent child and very proud.' He scoffs at

the cowherds for regarding Krishna as a god, and in order to

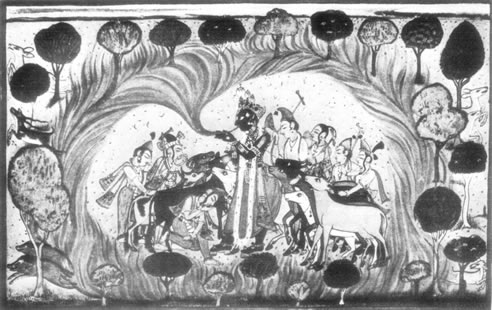

reinstate himself he orders the clouds to rain down torrents. The

cowherds, faced with floods on every side, appeal to Krishna.

Krishna, however, is fully alive to the position. He calms their

fears and raising the hill Govardhana, supports it on his little

finger.[26] The cowherds and cattle take shelter

under it and although Indra himself comes and pours down rain for

seven days, Braj and its inhabitants stay dry. Indra is compelled

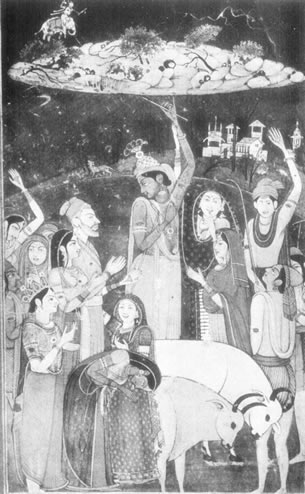

to admit that Vishnu has indeed descended in the form of Krishna

and retires to his abode. Krishna then sets the hill down in its

former place. Following this discomfiture, Indra comes down from

the sky accompanied by his white elephant and by Surabhi, the cow

of plenty. He offers his submission to Krishna, is pardoned and

returns.

All these events bring to a head the problem which has been

exercising the cowherds for long—who and what is Krishna?

Obviously no simple boy could lift the mountain on his finger. He

must clearly be someone much greater and they conclude that

Krishna can only be Vishnu himself. They accordingly beseech him

to show them the paradise of Vishnu. Krishna agrees, creates a

paradise and shows it to them. The cowherds see it and praise his

name. Yet it is part of the story that these flashes of insight

should be evanescent—that having realized one instant that

Krishna is God, the cowherds should regard him the next instant

as one of themselves. Having revealed his true nature, therefore,

Krishna becomes a cowherd once again and is accepted by the

cowherds as being only that.

One further incident must be recorded. In compliance with a

vow, Nanda assembles the cowherds and cowgirls and goes to the

shrine of Devi, the Earth Mother, to celebrate Krishna's twelfth

birthday. There they make lavish offerings of milk, curds and

butter and thank the goddess for protecting Krishna for so long.

Night comes on and they camp near the shrine. As Nanda is

sleeping, a huge python begins to swallow his foot.[27] Nanda calls to Krishna, who hastens to

his rescue. Logs are taken from a fire, but as soon as the snake

is touched by Krishna, a handsome young man emerges and stands

before him with folded hands. He explains that he was once the

celestial dancer, Sudarsana who in excess of pride drove his

chariot backwards and forwards a hundred times over the place

where a holy man was

meditating. As a consequence he was cursed and told to become a

python until Krishna came and released him. To attract Krishna's

attention he has seized the foot of Nanda. Krishna bids him go

and, ascending his chariot, Sudarsana returns to the gods.

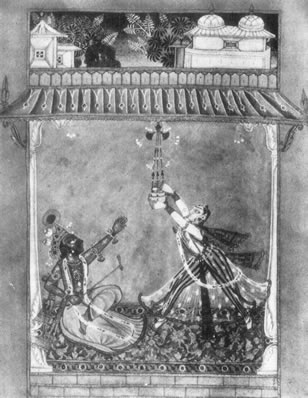

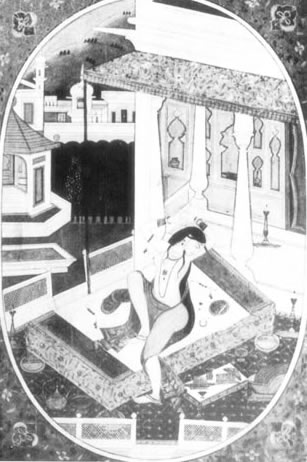

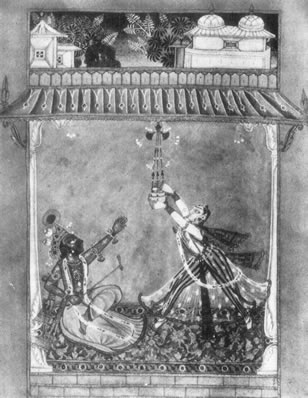

The Purana now returns to Krishna's encounters with the

cowgirls, their passionate longings and ardent desire to have him

as their lover. Since the incident at the river, they have been

waiting for him to keep his promise. Krishna, however, has

appeared blandly indifferent—going to the forest, playing

with the cowherds but coldly ignoring the cowgirls themselves.

When autumn comes, however, the beauty of the nights stirs his

feelings. Belatedly he recalls his promise and decides to fulfil

it. That night his flute sounds in the forest, its notes reaching

the ears of the cowgirls and thrilling them to the core. Like

girls in tribal India today, they know it is a call to love. They

put on new clothes, brush aside their husbands, ignore the other

members of their families and hurry to the forest. As they

arrive, Krishna stands superbly before them. He wears a crown of

peacocks' feathers and a yellow dhoti and his blue-black skin

shines in the moonlight. As the cowgirls throng to see him, he

twits them on their conduct. Are they not frightened at coming

into the dark forest? What are they doing abandoning their

families? Is not such wild behaviour quite unbefitting married

girls? Should not a married girl obey her husband in all things

and never for a moment leave him? Having enjoyed the deep forest

and the moonlight, let them return at once and soothe their

injured spouses. The cowgirls are stunned to hear such words,

hang their heads, sigh and dig their toes into the ground. They

begin to weep and at last turn on Krishna, saying 'Oh! why have

you deceived us so? It was your flute that made us come. We have

left our husbands for you. We live for your love. Where are we to

go?' 'If you really love me,' Krishna answers 'Dance and sing

with me.' His words fill the cowgirls with delight and

surrounding Krishna 'like golden creepers growing on a

dark-coloured hill,' they go with him to the banks of the Jumna.

Here Krishna has conjured up a golden circular terrace ornamented

with pearls and diamonds and cooled by sprouting plantains. The

moon pours down, saturating the forest. The cowgirls' joy

increases. They beautify their bodies and then, wild with love,

join with Krishna in singing and dancing. Modesty deserts them

and they do whatever pleases them, regarding Krishna as their

lover. As the night goes on, Krishna 'appears as beautiful as the

moon amidst the stars.'

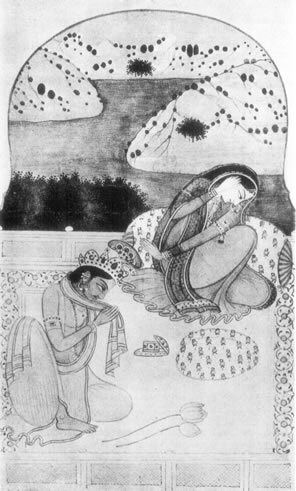

As the cowgirls' ecstasies

proceed, Krishna feels that they are fast exceeding themselves.

They think that he is in their power and are already swelling

with pride. He decides therefore to leave them suddenly, and

taking a single girl with him vanishes from the dance.[28] When they find him gone, the cowgirls are

at a loss to know what to do. 'Only a moment ago,' one of them

says, 'Krishna's arms were about my neck, and now he has gone.'

They begin to comb the forest, anxiously asking the trees, birds

and animals, for news. As they go, they recall Krishna's many

winning ways, his sweetnesses of character, his heart-provoking

charms and begin to mimic his acts—the slaying of Putana,

the quelling of Kaliya, the lifting of the hill Govardhana. One

girl imitates Krishna dancing and another Krishna playing. In all

these ways they strive to evoke his passionately-desired

presence. At length they discover Krishna's footprints and a

little farther on those of a woman beside them. They follow the

trail which leads them to a bed of leaves and on the leaves they

find a looking-glass. 'What was Krishna doing with this?' they

ask. 'He must have taken it with him,' a cowgirl answers, 'so

that while he braided his darling's hair, she could still

perceive his lovely form.' And burning with love, they continue

looking.

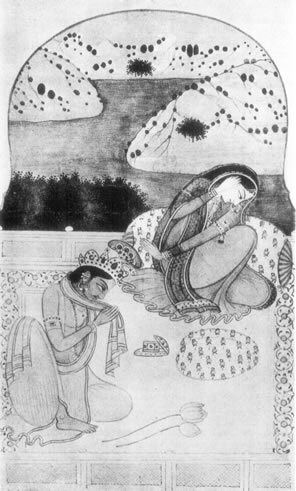

While they are searching, the particular cowgirl who has gone

with Krishna is tempted to take liberties. Thinking Krishna is

her slave, she complains of feeling tired and asks him to carry

her on his shoulders. Krishna smiles, sits down and asks her to

mount. But as she puts out her hands, he vanishes and she remains

standing with hands outstretched.[29] Tears stream

from her eyes. She is filled with bitter grief and cries 'O

Krishna! best of lovers, where have you gone? Take pity.'

As she is bemoaning her fate, her companions arrive.[30] They put their arms around her, comfort

her as best they can, and then, taking her with them, continue

through the moonlight their vain and anguished search. Krishna

still evades them and they return to the terrace where the

night's dancing had begun. There they once again implore Krishna

to have pity, declaring that there is none like him in charm,

that he is endlessly fascinating and that in all of them he has

aroused extremities of passionate love. But the night is empty,

their cries go unanswered, and moaning for the Krishna they

adore, they toss and writhe on the ground.

At last, Krishna relents. He stands among them and seeing him,

their cares vanish 'as creepers revive when sprinkled with the

water of life.' Some of the cowgirls hardly dare to be angry but

others upbraid him for so

brusquely deserting them. To all, Krishna gives the same answer.

He is not to be judged by ordinary standards. He is a constant

fulfiller of desire. It was to test the strength of their love

that he left them in the forest. They have survived this

stringent test and convinced him of their love. The girls are in

no mood to query his explanation and 'uniting with him' they

overwhelm him with frantic caresses.

Krishna now uses his 'delusive power' in order to provide each

girl with a semblance of himself. He asks them to dance and then

projects a whole series of Krishnas. 'The cowgirls in pairs

joined hands and Krishna was in their midst. Each thought he was

at her side and did not recognize him near anyone else. They put

their fingers in his fingers and whirled about with rapturous

delight. Krishna in their midst was like a lovely cloud

surrounded by lightning. Singing, dancing, embracing and loving,

they passed the hours in extremities of bliss. They took off

their clothes, their ornaments and jewels and offered them to

Krishna. The gods in heaven gazed on the scene and all the

goddesses longed to join. The singing mounted in the night air.

The winds were stilled and the streams ceased to flow. The stars

were entranced and the water of life poured down from the great

moon. So the night went on—on and on—and only when

six months were over did the dancers end their joy.'

As, at last, the dance concludes, Krishna takes the cowgirls

to the Jumna, bathes with them in the water, rids himself of

fatigue and then after once again gratifying their passions, bids

them go home. When they reach their houses, no one is aware that

they have not been there all the time.

[25]

[26]

[27]

[28]

[29]

[30]

(iii) The Death of the Tyrant

This scene with its crescendos of excitement, its delight in

physical passion and ecstatic exploration of sexual desire is, in

many ways, the climax of Krishna's pastoral career. It expresses

the devotion felt for him by the cowgirls. It stresses his loving

delight in their company. It suggests the blissful character of

the ultimate union. No further revelation, in fact, is necessary

for this is the crux of Krishna's life. None the less the

ostensible reason for his birth remains—to rid the earth of

the vicious tyrant Kansa—and to this the Purana now

returns.

We have seen how in his anxious quest for the child who is to

kill him, Kansa has dispatched his demon warriors on roving

commissions, authorizing them to attack and kill all likely

children. Many children have

in this way been slaughtered but Kansa is still uncertain whether

his prime purpose has been fulfilled. He has no certain knowledge

that among the dead children is his dreaded enemy. He is still

unaware that Krishna is destined to be his foe and he therefore

continues the hunt, his demon emissaries pouncing like commandos

on youthful stragglers and hounding them to their deaths. Among

such youths Krishna is still an obvious target and although

unaware that this is the true object of their quest, demons

continue to harry him.

One night Krishna and Balarama are in the forest with the

cowgirls when a yaksha demon, Sankhasura, a jewel flashing in his

head, comes among them. He drives the cowgirls off but hearing

their cries, Krishna follows after. Balarama stays with the girls

while Krishna catches and beheads the demon.

On another occasion, Krishna and Balarama are returning at

evening with the cows when a bull demon careers amongst them. He

runs amok scattering the cattle in all directions. Krishna,

however, is not at all daunted and after wrestling with the bull,

catches its horns and breaks its neck.

To such blind attacks there is no immediate end. One day,

however, a sage discloses to Kansa the true identity of his

enemy. He tells him in what manner Balarama and Krishna were

born, how Balarama was transferred from Devaki's womb to that of

Rohini, and how Krishna was transported to Nanda's house in

Gokula. Kansa is now confronted with the ghastly truth—how

Vasudeva's willingness to surrender his first six sons has lulled

his suspicions, how his confidence in Vasudeva has been entirely

misplaced, and how completely he has been deceived. He sends for

Vasudeva and is on the point of killing him when the sage

interposes, advising Kansa to imprison Vasudeva for the present

and meanwhile make an all-out attempt to kill or capture Balarama

and Krishna. Kansa sees the force of his remarks, spares Vasudeva

for the moment, throws him and Devaki into jail and dispatches a

special demon, the horse Kesi, on a murderous errand.

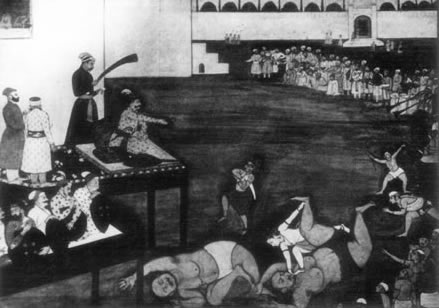

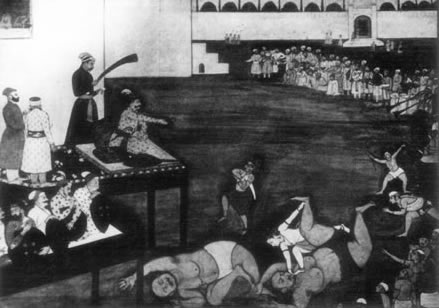

As the horse speeds on its way, Kansa assembles his demon