|

|

It is still claimed by many that the Arctic Ocean is a frozen body of water. Although it always contains large bodies of drift-ice and icebergs, it is not frozen over. The student of Arctic travels will invariably find that explorers were turned back by open water, and many instances are cited where they came near being carried out to sea and lost. Had they continued going out to sea,--not knowing that the earth was hollow,--they might have been lost but still live. One can easily imagine how those that tried to reach the pole by balloon might get lost and never find their way out, not knowing that the earth was hollow. What I wish to present to the reader, however, is the proof that the Arctic Ocean is an open body of water, abounding with game of all kinds, and the farther one advances the warmer it will be found. It is never free from cumulus and dark clouds,--coming up from the interior of the earth,--and from fogs, vapors, and other evidences of change. At certain seasons, when the atmosphere of the earth at the poles and the atmosphere of the interior of the earth were of the same temperature, no clouds would appear unless caused by an eruption of some kind, which, in many cases, might be clouds of dust or smoke.

The following extract will afford sufficient proof that my contention on this subject is correct. On page 265, Captain C. F. Hall says: "On this day (Dec. 26th) Captain Budington speaks in his journal respecting the position of the vessel as follows:

"'On ascending the Providence Iceberg and taking a look around, we see at first the open water at a distance of from three to four miles, extending the whole length of the strait from north to south. Our vessel lies on the edge of the land-floe, protected from seaward by the iceberg.'"

Here he finds open water to the north, extending the whole length of the straits from north to south.

Hall further writes, on page 284: "From the top of Providence Berg a dark fog was seen to the north, indicating water. At 10 a. m. three of the men,--Kruger, Nindemann and Hobby,--went to Cape Lupton to ascertain, if possible, the extent of the open water. On their return they reported several open spaces and much young ice--not more than a day old--so thin that it was easily broken by throwing pieces of ice upon it."

Note that he speaks of the dark fog in the north, indicating water, also that they found young ice not more than a day old.

Then, on page 288: "On the 23d of January the two Esquimaux, accompanied by two of the seamen, went to Cape Lupton. They reported a sea of open water extending as far as the eye could reach."

This also was in January: "a sea of open water as far as the eye could reach."

"On the 24th, Dr. Bessels, with two of the seamen, started at 11 a. m., with a dog team, to go north and examine the water reported by the seamen. They reached the third cape without difficulty. Leaving their sled, they arrived at the open water about 2 p. m. They reported a current there running to the north at a rate variously estimated from four miles to a half a mile per hour; at the same hour at the vessel the tide was falling."

Here again on the 24th open water was found, and a current running to the north at a rate variously estimated at from four miles to a half mile per hour; at the same time the tide was falling at the vessel, whereas, according to all established rules, the current should have been going the other way.

Page 289--Hall's diary--has more upon the subject: "On the 28th, Mr. Chester and a small party with dogs and sled, went to inspect the open water which now prevented their rounding the third cape. Mr. Chester observed a current of one mile an hour toward the north. The existence of this open water was regarded as favor-able to boat journeys in the spring. A large sled was ordered, upon which one of the boats could be transported to the open water, the extent of which it was proposed to ascertain as soon as possible. Toward evening the sky cleared, and the western coast could be distinctly seen."

Again we have evidence of open water, with the current going north.

Reference to the fog, so frequently referred to by the explorers, is made by Hall, on page 301: "I had for a short time a very extensive view over the straits, where the open water appeared as a dark, black spot on a white field. My joy and pleasure did not, however, last long, as fifteen minutes only sufficed to cover all by a most impenetrable fog, a phenomenon which I never observed before in winter. I was hardly able to see twenty paces to the west and northwest, though toward the south it remained free for a considerable time. There, above the new ice of the bay, a most beautiful fog-stratum, intensely white, was hanging, and continually changing its height."

Being in winter, he calls it a phenomenon. Anything that could cause that fog must be out of the ordinary, and must be accounted for in some other way. If the earth were solid, and the ocean extended to the pole, or connected with land surrounding the pole, there would be nothing to produce that fog. It was caused by the warm air coming from the interior of the earth.

On page 236 Kane says: "Indeed, some circumstances which he (McGary) reports seem to point to the existence of a north water all the year round; and the frequent water-skies, fogs, etc., that we have seen to the S. W. during the winter go to confirm the fact."

He tells us more on the subject (page 299): "Morton's journal, on Monday, the 26th, says: 'As far as I could see the open passages were fifteen miles or more wide, with sometimes mashed ice separating them. But it is all small ice, and I think it either drives out to the open space to the north, or rots and sinks, as I could see none ahead to the north.'

"The coast after passing the cape, he thought, must trend to the eastward, as he could at no time when below it see any land beyond. But the west coast still opened to the north.

"His highest station of outlook at the point where his progress was arrested he supposed to be about three hundred feet above the sea. From this point, some six degrees to the west of north, he remarked in the farthest distance a peak truncated at its top like the cliffs of Magdalena Bay. It was bare at its summit. This peak, the most remote northern land known upon our globe, takes its name from the great pioneer of Arctic travel, Sir Edward Parry. * * * The summits were generally rounded, resembling, to use his own expression, a succession of sugar-loaves and stacked cannon-balls declining slowly in the perspective. Mr. Morton saw no ice."

Greely says, on page 150, in reference to this open-water question: "The cliffs on the north side of Wrangel Bay were still washed by the open sea, showing that the storms of the previous month had broken up the sea-floe in many places."

Again, on page 254: "This melting of the snow, as well as the limiting clause of Dr. Pavy's orders, prevented him from attempting to proceed northward over the disintegrated pack. He consequently decided to return at once to Cape Joseph Henry. Taking only indispensable effects, and sufficient provisions to feed the party for a few days, they started in haste for the Cape, but on arriving opposite it found open water of three-quarters of a mile in extent between them and the land. On returning to their old camp for some further stores, the water-space toward Cape Hecla was found to have increased in width to about three miles, while the water-clouds to the north and northeast had increased in amount and distinctness."

He does not speak of the increase in amount and distinctness of the water-clouds as one of the signs indicating water in the north, but of an established fact--that the water-cloud (or cloud where the water is reflected in the skies) is no longer a question, but a certainty. It may strike the reader as strange that reference is made so often to water, ice, and land being reflected in the sky. This illustrates that if the sky correctly reflects at all times the condition of the water, the ice, and the land, it will reflect a fire with as much accuracy as it reflects water.

Dr. Pavy (Greely, page 255) concluded it unwise to return for some of the abandoned articles, as the pack was liable to move northward again, since in the offing it was drifting south. He immediately started southward, impressed with the idea "that Robeson Channel was open, and that great haste was necessary, fearing that the ice toward Cape Sheridan would also break up, and seriously delay their progress homeward."

The ice leading back to their camp was in better condition than farther north, and from there they traveled clear back to Lincoln Bay.

"At noon, April 24, the party camped at View Point, where a record was left in the old English cairn, and in the evening of the following day they reached Harley Spit. At 7 a. m. of the 26th the party was again in the snow-house at Black Cape. From Cape Sheridan, south of the palæocrystic pack, the ice was broken, in motion, and in many places separated by large lanes of water." The next morning the wind blew from the south, and caused an opening to the north of Black Cape, "between the solid ice of Robeson Channel and the loose floes above--a space of about a mile wide, and of which the transversal end disappeared two or three miles from the coast." The party, however, traveled southward over solid ice to Lincoln Bay.

Despite steady and unremitting labor, and the possession of health and strength, this attempt to travel over the frozen sea failed through natural causes. But, as Dr. Pavy says, it "determined the important fact that last fall open water could have been found as far as Cape Sheridan, and from Conical Hill perhaps to Cape Columbia; and proved, by our experience, that even in such high latitudes the pack may be in motion at an early period of the year; perhaps at any time. I am firmly convinced that but for our misfortune in finding open water, we could, without greatly distancing Commander Markham, have reached perhaps the latitude of 84 deg. N."

Greely writes, on page 275: "We traveled alongside the open river, keeping to the bordering ice-walls, which decreased in thickness and eventually disappeared entirely at a point where the stream doubt-less remains open the entire year. Here we were driven to the hillside, where the deep snow and sharp projecting rocks made travel slow, and rendered the task of keeping the sledge upright a severe one. A couple of hundred yards farther and a sharp turn brought in sight a scene which we shall all remember to our dying day. Before us was an immense icebound lake. Its snowy covering reflected 'diamond dust,' from the midnight sun, and at our feet was a broad pool of open, blue water which fed the river. To the northward some eight or ten miles--its base at the northern edge of the lake (Hazen)--a partly snow-clad range of high hills (Gar-field Range) appeared, behind and above which the hog-back, snow-clad summits of the United States Mountains rose with their stern, unchanging splendor. To the right and left on the southern shore low, rounded hills, bare, as a role, of snow, extended far to east and west, until in reality or perspective they joined the curving mountains to the north. The scene was one of great beauty and impressiveness.

"The excitement and enthusiasm which our new discoveries had engendered, here culminated, for our vantage ground was such that all seemed revealed, and no point hidden. Connell, who had continually lamented the frozen foot which turned him back from the trip to North Greenland, declared enthusiastically that he would not have missed the scene and discoveries for all the Polar Sea."

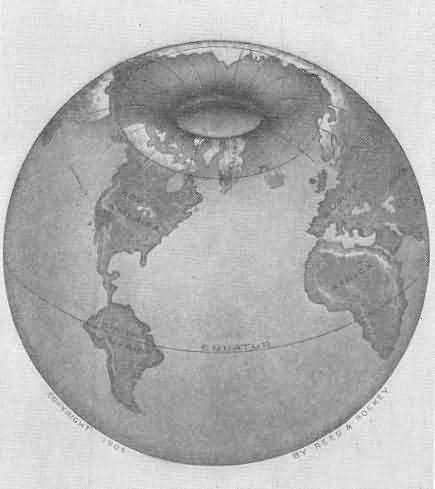

Greely speaks of open water the year round. If there be open water the year round at the farthest point north, can any good reason be assigned why all have failed to reach the pole? The men that have spent their time, comfort, and, in several cases, lives, were all men more than anxious to succeed, yet, strange to say, all failed. Was this because the weather got warmer, and they found game more plentiful? No, it was because there was not such a place.

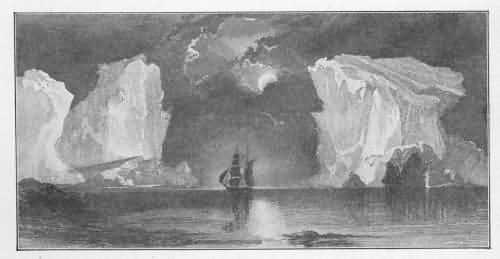

The following are extracts from Dr. Kane's work, pages 378 and 379: "As far as I could discern, the sea was open, a swell coming in from the northward and running crosswise, as if with a small eastern set. The wind was due N.--enough of it to mike whitecaps--and the surf broke in on rocks below in regular breakers. The sky to the N. W. was of dark rain-cloud, the first that I had seen since the brig was frozen up. Ivory-gulls were nesting in the rocks above me, and out to sea were molle-mock and silver-backed gulls. The ducks had not been seen N. of the first island of the channel, but petrel and gulls hung about the waves near the coast.

"June 26--Before starting, I took a meridian-altitude of the sun (this being the highest northern point I obtained except one, as during the last two days the weather had been cloudy, with a gale blowing from the north), and then set off at 4 p. m. on our return down the channel to the south.

"I cannot imagine what becomes of the ice. A strong current sets in almost constantly to the south; but, from altitudes of more than five hundred feet, I saw only narrow strips of ice, with great spaces of open water, from ten to fifteen miles in breadth, between them. It must, therefore, either go to an open space in the north, or dissolve. The tides in-shore seemed to make both north and south; but the tide from northward ran seven hours, and there was no slack water. The wind blew heavily down the channel from the open water, and had been freshening since yesterday nearly to a gale; but it brought no ice with it."

Dr. Kane says that he cannot imagine what becomes of the ice, and that it apparently goes to an open space in the north or dissolves. Again we read that for seven hours the tide was from north, there being no slack water, thus showing that it did not come from the pole. If the tide carne from the pole, they should have had low tide at the expiration of six hours. The tide and wind bringing no ice during all that time, shows plainly enough there was none to bring.

In the second volume of Nansen's work (page 505) more information bears on this point: "I find in my journal for that day: Are continually discovering new islands of lands to the south. There is one great land of snow beyond us in the west, and it seems to extend southward a long way. This snow land seemed to us extremely mysterious; we had not yet discovered a single dark patch on it, only snow and ice everywhere. We had no clear idea of its extent, as we had only caught glimpses of it now and then, when the mist lifted a little. It seemed to be quite low, but we thought it must be of a wider extent than any of the lands we had hitherto traveled along. To the east we found island upon island, and sounds and fiords the whole way along. We mapped it all as well as we could, but this did not help us to find out where we were; they seemed to be only a crowd of small islands, and every now and then a view of what we took to be the ocean to the east opened up between them."

Those islands--passed during the long drift and travel for over a year--were undoubtedly islands that had never been seen before. It is more than likely that Nansen and his crew were farther into the interior than anyone had previously been. If they for one moment could have understood that the earth was hollow, conditions that seemed unexplainable and unaccountable would have been perfectly clear; but as they never dreamed of that, it is not strange that they were constantly mixed, and that currents and winds were always going and coming contrary to customs and theories.

The mist that Nansen speaks of is one strong proof that the earth is hollow and warmer in winter than the exterior.

Changes that are nearly always going on--caused by the wind blowing in or out--must bring about just such effects, as the atmosphere cannot be the same, and is either dryer or more moist, hotter or colder. In either case it would be manifested in some kind of a change--cloud, fog, snow or rain.

In Vol. I, page 195, Nansen writes of a fellow-explorer: "In his account of his voyage, Nordenskiold writes as follows of the condition of this channel: 'We were met by only small quantities of that sort of ice which has a layer of fresh-water ice on the top of the salt, and we noticed that it was all melting fiord or river ice. I hardly think that we came all day on a single piece of ice big enough to have cut up a seal upon.'"

On page 196 of the same volume, occurs: "We could hardly get on at all for the dead water, and we swept the whole sea along with us. It is a peculiar phenomenon,--this dead water. We had at present a better opportunity of studying it than we desired. It occurs where a surface-layer of fresh water rests upon the salt water of the sea, and this fresh water is carried along with the ship, gliding on the heavier sea beneath as if on a fixed foundation. The difference between the two strata was in this case so great that while we had drinking-water on the surface, the water we got from the bottom cock of the engine room was far too salt to be used for the boiler. Dead water manifests itself in the form of larger or smaller ripples or waves stretching across the wake, the one behind the other, arising sometimes as far forward as almost amidships. We made loops in our course, turned sometimes right around, tried all sorts of antics to get clear of it, but to very little purpose. The moment the engine stopped it seemed as if the ship were sucked back. In spite of the Fram's weight and the momentum she usually has, we could in the present instance go at full speed till within a fathom or two of the edge of the ice, and hardly feel a shock when she touched."

I wish to call special attention to Nansen's information about dead water. What is dead water? Does he mean water that has no current? It seems to be one of those phenomena for which they could not account. The only theory that I can present is: the dead water was at a point where the centre of gravity was extremely strong; the salt water, being heavier than the fresh, was drawn to the earth with such force that the fresh water could not penetrate it, and laid as separate and distinct upon it as cream upon a pan of milk. In the absence of any further proof or evidence, this dead water must have been about half-way round the curve, entering the interior of the earth, and, if so, was in perfect accordance with the laws of the universe--that the centre of gravity is strongest at this point.

According to Nansen, the ship could make no headway, and they turned in different directions, and the difference between the strata of salt and fresh water in this case was so great that while they had drinking water on the surface, the water obtained from the bottom cock of the engine room was far too salty to be used for the boiler. Is there any difference between water found in the Arctic Ocean and that found in any other ocean? If there be a difference, what causes it? In New York harbor we have fresh water and salt water, but when they meet, they mix. The water that comes down the Hudson River is fresh water, and the water that meets it coming in from the ocean is salt; but there is no line where one may be called fresh, and the other salt. Why should there be a difference, then, in the Arctic Ocean? No other explanation than what I have just stated can be given--that the centre of gravity is so strong near the poles that the heavier body is drawn solidly toward the earth, and the lighter one cannot penetrate it.

Nansen speaks, on page 209, of a different kind of water--a clayey water--where there is no commingling. "To the north of the point ahead of us I saw open water; there was some ice between us and it, but the Fram forced her way through. When we got out, right off the point, I was surprised to notice the sea suddenly covered with brown, clayey water. It could not be a deep layer, for the track we left behind us was quite clear. The clayey water seemed to be skimmed to either side by the passage of the ship. I ordered soundings to be taken, and found, as I expected, shallow water--first, eight fathoms, then six and one-half, then five and one-half. I stopped now, and backed. Things looked very suspicious, and round us ice-floes lay stranded. There was also a very strong current running northeast. Constantly sounding, we again went slowly forward. Fortunately the lead went on showing five fathoms. Presently we got into deeper water--six fathoms, then six and one-half, and now we went on at full speed again. We were soon out into the clear, blue water on the other side. There was quite a sharp boundary line between the brown surface and the clear blue. The muddy water evidently came from some river a little farther south."

Many claim that the Arctic Ocean is a frozen body of water; and for that reason considerable space is devoted to the question of open water in the Arctic regions. I contend that the Arctic Ocean is never frozen over, although it appears so at different points where large fields of ice have drifted up from the interior of the earth, and lodged at certain places. Nansen spent two years drifting in the Arctic Ocean, which is proof positive that during that time it was not closed by ice. The icebergs that come up from the interior and fill the Arctic Ocean and connecting straits and sounds clear into the Atlantic, cause portions of the Arctic to be filled with ice almost constantly. If it be true that the centre of attraction is strongest at the turning point, large fields of ice would naturally be held in that position, until very strong currents, heavy winds, or large floes coming up from the interior, would shove the ice past that point.

On page 212 of his work Nansen speaks of making such splendid time--eight knots by the log. "Sverdrup thought it would be safer to stay where we were; but it would be too annoying to miss this splendid opportunity; and the sunshine was so beautiful, and the sky so smiling and reassuring! I gave orders to set sail, and soon we were pushing through the ice, under steam, and with every stitch of canvas that we could crowd on. Cape Chelyuskin must be vanquished! Never had the Fram gone so fast; she made more than eight knots by the log; it seemed as though she knew how much depended on her getting on. Soon we were through the ice, and had open water along the land as far as eye could reach. We passed point after point, discovering new fiords and islands on the way, and soon I thought that I caught a glimpse through a large telescope of some mountains far away north; they must be in the neighborhood of Cape Chelyuskin itself."

This was on one of the fifteen days in succession when Nansen supposed he was sailing directly north. If he was not sailing north, or nearly so, where was he sailing? He ought to have covered a long distance, as he speaks of making nine knots an hour. Had he only made five knots, the distance would have been nearly 2,000 miles, yet when he took his reckoning he found himself in latitude 79 degs. If he had been going straight north, as he supposed he was, his sailing would have taken him over 1,200 miles past the pole. Allowing for loss of speed, owing to the strength of currents, and dodging bergs and floes, he would still have been beyond the pole.

This is the strongest proof possible that the earth is hollow, and that there is no way of reaching the spot where the North Pole is supposed to be.

On page 217 Nansen writes of one star--the only one to be seen. "It stood straight above Cape Chelyuskin, shining clearly and sadly in the pale sky. As we sailed on and got the cape more to the east of us, the star went with it: it was always there, straight above. I could not help sitting watching it. It seemed to have some charm for me, and to bring such peace. Was it my star? Was it the spirit of home following and smiling to me now? Many a thought it brought to me as the Fram toiled on through the melancholy night, past the northernmost point of the old world."

From this, it appears as if he had gone a considerable distance into the interior of the earth--a fact that had something to do, perhaps, with his seeing only one star. I hardly think that he was far enough in to shut out from view all other stars, but his position would certainly shut out a great many.

On page 218 he mentions sailing southward to avoid some ice-floes, and making at the time nine knots an hour. "So that we were now off King Oscar's Bay; but I looked in vain through the telescope for Nordenskiold's cairn. I had the greatest inclination to land, but did not think that we could spare the time. The bay, which was clear of ice at the time of Vegs's visit, was now closed-in with thick winter ice, frozen fast to the land. We had an open channel before us; but we could see the edge of the drift-ice out at sea. A little farther west we passed a couple of small islands, lying a short way from the coast. We had to stop before noon at the north-western corner of Chelyuskin, on account of the drift-ice, which seemed to reach right into the land before us. To judge by the dark air, there was open water again on the other side of an island which lay ahead. We landed, and made sure that some straits or fiords on the inside of this island, to the south, were quite closed with firm ice; and in the evening the Fram forced her way through the drift-ice on the outside of it. We steamed and sailed southward along the coast all night, making splendid way; when the wind was blowing stiffest, we went at the rate of nine knots. We came upon ice every now and then, but got through it easily."

It is apparent that he went a long way into the interior of the earth.

On page 220 he tells of losing sight of land entirely. "In the course of the day we quite lost sight of land, and, strangely enough, did not see it again; nor did we see the islands of St. Peter and St. Paul, though, according to the maps, our course lay past them."

This statement shows that the explorer and his men knew nothing about where they were. If the charts showed that the islands mentioned above were on the ship's course, then they were wrong, or Nansen did not know where he was.

"The channel was still free from ice," writes Hansen, on page 225. "We now continued on our course, against a strong current, southward along the coast, past the mouth of the Chatanga. This eastern part of the Taimur Peninsula is a comparatively high, mountainous region, but with a lower level stretch between the mountains and the sea, apparently the same kind of low land we had seen along the coast almost the whole way. As the sea seemed to be tolerably open and free from ice, we made several attempts to shorten our course by leaving the coast and striking across for the mouth of the Olenek; but every time thick ice drove us back to our channel by the land."

On page 226, Nansen says: "The following day we got into good, open water, but shallow--never more than six to seven fathoms. We heard the roaring waves to the east, so there must certainly be open water in that direction, which indeed we had expected. It was plain that the Lena, with its masses of warm water, was beginning to assert its influence. The sea here was browner, and showed signs of some mixture of muddy river water. It was also much less salt."

He found the change so marked that he thought the warm water came from the Lena. Now, the Lena is a river in Siberia, and its waters are no warmer than those of any other river in that country. In certain seasons of the year it discharges a great deal of water, which is not warm enough, however, to have any effect on the Arctic Ocean. Again: the Lena is right on the opposite side of the pole from where Nansen was, and the distance between the two points is considerable.

More concerning this connection is given on page 227. "Saturday, September 16th--We are keeping a northwesterly course (by compass) through open water, and have got pretty well north, but see no ice, and the air is dark to the northward. Mild weather, and water comparatively warm, as high as 35 deg. Fahr. We have a current against us, and are always considerably west of our reckoning. Several flocks of eider-ducks were seen in the course of the day. We ought to have land to the north of us; can it be that which is keeping back the ice?"

The reader will note what he says in regard to their location: "and are always considerably west of our reckoning." So far as knowing their exact position, they were, in fact, lost. If reckoning was taken on the basis that the compass was pointing in a certain direction, when, as a matter of fact, it was pointing in the opposite direction to what they supposed, their reckoning was all wrong. Nansen himself says that they were keeping, by compass, a north-westerly course. Is it not fair to infer that the influence that controlled the compass when Nansen was steering by it, was the same as had controlled it all the time, and that the mixing-up, or confusion, was with the individual, and not the compass?

On page 227 Nansen recounts that they met ice, and supposed, at first, that it would be the end of their journey. How-ever, it was only small drift-ice; and he states, further, that he had "good sailing and made good progress.

"Next day we met ice, and had to hold a little to the south to keep clear of it; and I began to fear that we should not be able to get as far as I hoped. But in my notes for the following day (Monday, September 18th) I read: A splendid day. Shaped our course northward, to the west of Bielkoff Island. Open sea; good wind from the west; good progress. Weather clear, and we had a little sunshine in the after-noon. Now the decisive moment approaches. At 12.15 shaped our course north to east (by compass). Now it is to be proved if my theory, on which the whole expedition is based, is correct,--if we are to find a little north from here a north-flowing current. So far everything is better than I had expected. We are in latitude 75½ deg. N., and have still open water and dark sky to the north and west. In the evening there was ice-light ahead and on the starboard bow. About seven I thought that I could see ice, which, however, rose so regularly that it more resembled land, but it was too dark to see distinctly. It seemed as if it might be Bielkoff Island, and a big light spot farther to the east might even be the reflection from the snow-covered Kotelnoi."

For the previous thirteen days he had found no interruption to speak of, but had continued, as he supposed, steadily north. However, when he took his reckoning he found that he was in latitude 75½ deg. north, and open water still ahead.

On page 228 he remarks that it was a strange feeling to be sailing away north in the dark night to unknown lands, over an open, rolling sea, where no ship or boat had been before. "We might have been hundreds of miles away in more southerly waters, the air was so mild for September in this latitude."

They were surely in the interior of the earth at that point, several miles past the turning point.

Under Tuesday, September 19th (the following day) (page 228), he writes: "I have never had such a splendid sail. On to the north, steadily north, with a good wind, as fast as steam and sail can take us, and open sea mile after mile, watch after watch, through these unknown regions, always clearer and clearer of ice, one might almost say: 'How long will this last?' The eye always turns to the northward as one paces the bridge. It is gazing into the future. But there is always the same dark sky ahead, which means open sea."

The reader will here notice that the appearance of the sky shows the condition of the surface of the earth. This is mentioned to show that when an aurora or a burning fire is reflected in the sky, it should be called a fire, instead of something produced by electricity.

In regard to their good fortune in finding clear sailing direct, as they supposed, toward the pole, Nansen remarks: "Henriksen answered from the crow's-nest when I called up to him. 'They little think at home in Norway just now that we are sailing straight for the pole in clear water.' No, they don't believe we have got so far. And I shouldn't have believed it myself if anyone had prophesied it to me a fortnight ago; but true it is. All my reflections and inferences on the subject had led me to expect open water for a good way farther north; but it is seldom that one's inspirations turn out to be so correct. No ice-lights in any direction, not even now in the evening. We saw no land the whole day; but we had fog and thick weather all morning and forenoon, so that we were still going at half-speed, as we were afraid of coming suddenly on something."

After discussing their good fortune, they again referred to the sky. No ice-lights were in any direction, not even in the evening; but they had thick weather all morning and afternoon, and, as a consequence, were running at half-speed.

"I have almost to ask myself if this is not a dream," writes he on page 230. "One must have gone against the stream to know what it means to go with the stream. As it was on the Greenland expedition, so it is here."

He regards it as such good fortune that he asks himself, "Is it not a dream?" Yet they were no nearer the pole than they were two weeks before.

On the same page he refers to the water: "Hardly any life visible here. Saw an auk or black guillemot to-day, and later a sea-gull in the distance. When I was hauling up a bucket of water in the evening to wash the deck I noticed that it was sparkling with phosphorescence. One could almost have imagined one's self to be in the south."

This is the second time that he notes the phosphorescent water and the fish they caught in that part of the world. In another instance, he stated that, when emptying a net of fish, they looked like glowing embers. This condition of things will he found in many cases, perhaps, in the interior of the earth. Nature provides for every emergency, and it would not be surprising to find phosphorescent effects throughout the interior for the purpose of relieving the darkness. This proved to be nearly Nansen's journey's end; for, on the 21st he met an ice-floe coming up from the interior of the earth, and supposed it to he solid ice in the north. He says (page 233):

"So in the meantime we made fast to a great ice-block, and prepared to clean the boiler and shift coals. We are lying in open water, with only a few large floes here and there; but I have a presentiment that this is our winter harbor."

There is no reason why their progress should have stopped at that point. Anyone on his way to the interior of the earth would not think of such a thing, yet one trying to get to the North Pole might well conclude that that was the commencement of the stopping-place. From this time on to October 12th, nothing of special note occurred.

Three weeks later, he mentions that the water was still open (page 273): "Thursday, October 12th.--In the morning we and our floe were drifting on blue water in the middle of a large, open lane, which stretched far to the north, and in the north the atmosphere at the horizon was dark and blue. As far as we could see from the crow's-nest with the small field-glass, there was no end to the open water, with only single pieces of ice sticking up in it here and there. These are extraordinary changes."

He again speaks of "this same dark atmosphere in the north," on page 278, and "that it indicates open water. To-day again, this stretched far away towards the northern horizon, where the same dark atmosphere indicated some extent of open water."

On page 282 he speaks of open water to the north, also the ice-pressure: "Saturday, October 14.--To-day we have got on the rudder; the engine is pretty well in order, and we are clear to start north when the ice opens to-morrow morning. It is still slackening and packing quite regularly twice a day, so that we can calculate on it beforehand. To-day we had the same open channel to the north, and beyond it open sea as far as our view extended. What can this mean? This evening the pressure has been pretty violent. The floes were packed up against the Fram on the port side, and were once or twice on the point of toppling over the rail. The ice, however, broke below; they tumbled back again, and had to go under us, after all."

On page 291 he is puzzled to know why everything is the reverse of what he had figured it should be. "I had a sounding taken; it showed over seventy-three fathoms (one hundred and thirty-five metres), so we are in deeper water again. The sounding-line indicated that we are drifting southwest. I do not understand this steady drift southward. There has not been much wind either lately; there is certainly a little from the north to-day, but not strong. What can be the reason of it? With all my information, all my reasoning, all my putting of two and two together, I cannot account for any south-going current here--there ought to be a north-going one. If the current runs south here, how is that great, open sea we steamed north across to be explained? and the bay we ended in farthest north? These could only be produced by the north-going current which I presupposed. The only thing which puts me out a bit is that west-going current which we had against us during our whole voyage along the Siberian coast."

What puzzled him was the fact that after he had sailed for fifteen successive days, from September 6 to September 21, with hardly any interruption--what little there was arose mainly from fog--there was so much southerly current and no ice. That would lead to the impression there was no ice to the north, or it would have drifted with the south-going current, and closed the vast body of open water he had sailed through. It is evident the ice in the Arctic is confined to the floes that come from the interior of the earth. Another evidence that he had advanced far into the interior of the earth, is the quantity of fresh water he met.

Had he known that the earth was hollow, and that they were not sailing north, as he supposed, the answers to these queries would have been clear to him, or the problem have admitted of a different basis of reasoning. He was also going out of salt water; as he says, "the water is not nearly so salt."

On page 338 he is at loss to know why he should find such deep water. "Thursday, December 21.--It is extraordinary, after all, how the time passes. Here we are at the shortest day, though we have no day. But now we are moving on to light, and summer again. We tried to sound to-day; had out twenty-one hundred metres (over eleven hundred. fathoms) of line without reaching the bottom. We have no more lines; what is to be done? Who could have guessed that we should find such deep water?"

In rounding the curve of the interior of the earth, as I have said before, it is as likely to be water as land, and is held in position by gravity. I suppose there is, in many cases, practically no bottom, the water being miles and miles deep.

On page 399, under date of Wednesday, February 21st, Nansen says: "The south wind continues. Took up the bag-nets to-day which were put out the day before yesterday. In the upper one, which hung near the surface, there was chiefly amphipoda; in Murray's net, which hung at about fifty fathoms' depth, there was a variety of small crustacea and other small animals shining with such a strong phosphorescence that the contents of the net looked like glowing embers as I emptied them out in the cook's galley by lamplight. To my astonishment the net-line pointed northwest, though from the wind there ought to be a good northerly drift. To clear this matter up I let the net down in the afternoon, and as soon as it got a little way under the ice the line pointed northwest again, and continued to do so the whole afternoon. How is this phenomenon to be explained? Can we, after all, be in a current moving northwest?"

Again he is at sea, being unable to account for the current, which is entirely contrary to what he figured.

On page 309 Kane gives some interesting information on this, subject: "This precipitous headland, the farthest point attained by the party, was named Cape Independence. It is in latitude 81 deg. 22 min. N. and longitude 65 deg. 35 min. W. It was only touched by William Morton, who left his dogs and made his way to it along the coast. From it the western coast was seen stretching far towards the north, with an iceless horizon, and a heavy swell rolling in with whitecaps. At a height of about five hundred feet above the sea this great expanse still presented all the appearance of an open and iceless sea. In claiming for it this character I have reference only to the facts actually observed, without seeking confirmation or support from any deduction or theory. Among such facts are the following:

"1. It was approached by a channel entirely free from ice, having a length of fifty-two and a mean width of thirty-six geographical miles.

"2. The coast-ice along the water-line of this channel had been completely destroyed by thaw and water action, while an unbroken belt of solid ice, one hundred and twenty-two miles in diameter, extended to the south.

"3. A gale from the northeast, of fifty-four hours' duration, brought a heavy sea from that quarter, without disclosing any drift or other ice.

"4. Dark nimbus clouds and water-sky invested the northeastern horizon.

"5. Crowds of migratory birds were observed thronging its waters."

Nansen, in Vol. II, pages 534 and 535, says: "We now found that in March he must have been at no great distance south of our winter hut, but had to turn there, as he was stopped by open water--the same open water of which we had seen the dark atmosphere all the winter."

Herein he refers to Jackson, who found him after his long trip on the ice with Johansen. After leaving the Fram, this open water that kept them apart was seen by Nansen in the skies all winter, whenever the atmosphere was favorable.

Now, what are the conditions obtaining in the Antarctic region? Louis Bernacchi, who spent nearly two years in the extreme southern portion, tells us:

"At Cape Adare huge bergs were often observed during perfectly calm weather, traveling at about four knots per hour toward the northwest." (Page 39.)

"In this open sea is where they meet so many icebergs."

"An open sea, comparatively free from ice, is met with in the Antarctic regions."

He declares an open sea can be found. If so, why do they not reach the pole? He tells us that they passed the magnetic pole. They did; and had they kept on, instead of turning back for fear of being lost at sea, they would have made a great discovery.

But I am in favor of entering the interior of the earth from the north, on account of the apparently high winds in the Antarctic. I also am of the opinion that Mount Erebus--from which Bernacchi saw smoke coming--is in the interior of the earth, or part of the way in.

After the foregoing evidence, is it possible that anyone can believe that the respective oceans are frozen bodies of water? If they do not believe that these oceans are frozen, why do the explorers fail to reach the poles--if there be such places?