|

|

Folklore as an Historical Science

By George Laurence Gomme

CHAPTER III

PSYCHOLOGICAL CONDITIONS

Although the great mass of folklore rests upon tradition and tradition alone, an important aid to tradition comes from certain psychological conditions which we must now consider. At an early stage all students of folklore will have discovered that it is not entirely to tradition that folklore is indebted for its material. There are still people capable of thinking, capable of believing, in the primitive way and in the primitive degree. Such people are of course the descendants of long ancestors of such people—people whose minds are not attuned to the civilisation around them; people, perhaps, whose minds have been to an extent stunted and kept back by the civilisation around them. There can be no doubt that civilisation and all it demands of mankind acts as a deterrent upon the minds of some living within the civilisation zone, and belonging apparently to the civilised society. This is the root cause of some of the lunacy and much of the crime which apparently exists as a necessary adjunct of civilisation, and it leads to various forms of thought inconsistent with the knowledge and ideas of the age. When these forms of thought are not concentrated into[Pg181] a new religious sect by the operation of social laws, they become what is sometimes called mere superstition, that kind of superstition which consists of using the same power of logic to a narrow set of facts which primitive man was in the habit of using, and thus repeating in this age the methods of primitive science. We cannot quite understand this in the age of railways and schools and inventions, but it will be understood better if we go back for only a generation or two to those parts of our country which are most remote from civilising influences, and obtain some information as to their condition.

This cannot be better accomplished than by referring to a Scottish author writing, in 1835, of the superstitions then prevailing in Scotland. "Our whole genuine records," says Dalyell,

"teem with the most repulsive pictures of the weakness, bigotry, turbulence, and fierce and treacherous cruelty of the populace. False and corrupt innovations of literature, a compound of facts and fiction, intermingling the old and the new in heterogeneous assemblage, would persuade us to think much more of our forefathers than they thought of themselves. Scotland, until the most modern date, was an utter stranger to civilisation, presenting a sterile country with a famished people, wasted by hordes of mendicants readier to seize than to solicit—void of ingenious arts and useful manufactures, possessed of little skill and learning, plunged in constant war and rapine, full of insubordination, disturbing public rule and private peace. For waving pendants, flowing draperies, brilliant colours, eagles' feathers, herons' plumes, feasts or festivals so splendid in imagination, let naked limbs, scanty, sombre garments to elude discovery by the foe, bits of heath stuck in bonnets if they had them, precarious sustenance, abject humility and all those hardships inseparable[Pg182] from uncultivated tribes and countries be instituted as a juster portrait of earlier generations."[237]

This statement as to Scotland is correctly drawn from social conditions which have now passed away, but which, down to the beginning of last century, belonged to the ordinary life of the people. Thus it is recorded that

"over all the highlands of Scotland, and in this county in common with others, the practice of building what are called head-dykes was of very remote antiquity. The head-dyke was drawn across the head of a farm, when nature had marked the boundary betwixt the green pastures and that portion of hill which was covered totally or partially with heath. Above this fence the young cattle, the horses, the sheep and goats were kept in the summer months. The milch cows were fed below, except during the time the farmer's family removed to the distant grazings called sheilings. Beyond the head-dyke little attention was paid to boundaries. These enclosures exhibit the most evident traces of extreme old age."[238]

In Ireland the same conditions obtained so late as the sixteenth century; the native Irish retained their wandering habits, tilling a piece of fertile land in the spring, then retiring with their herds to the booleys or dairy habitations, generally in the mountain districts in the summer, and moving about where the herbage afforded sustenance to their cattle.[239] An eighteenth-century [Pg183]traveller in Ireland was assured that the quarter called Connaught was "inhabited by a kind of savages," and there is record of the capture of a hairy dwarf near Longford, who appears hardly to belong to civilisation.[240] Similar conditions obtained in the northern counties of England, and in other parts.[241] Special circumstances kept the borderland outside the influences of ordinary civilised thought and control, and these circumstances have been recorded by an eighteenth-century observer, from whom I will quote one or two facts as to the mode of life of these people: "That they might be more invisible during their outrodes and consequently less liable to the effects of their enemies' vigilance, the colour of their cloathes resembled that of the scenes of their employment or of their season of action, that is, of a brown heath and cloudy evening. Thus examples of what might condemn their conduct were never offered to them, and immemorial custom seemed as it were to sanctify their wildness. Every border-man, almost without exception, was brought up in a state which we would call unhappy, and every circumstance of his life tended to confirm his partiality for an uncertain bed and unprovided diet."[242]

The evidence which this acute observer collected led him to conclude that the "almost uniform train of circumstances which affected these countries from their border situation, and the little difference there was between one of the dark ages and another, strongly[Pg184] induce me to believe that the Northern people were little altered in manners from very remote times to those immediately preceding the reign of Queen Elizabeth," and this is confirmed by what we actually find from the report of the Commissioners appointed to settle the peace of the Marches by fixed and established ordinances, who collected "their ordinances from the traditional accounts of ancient usages that had been sanctified as laws by the length of time which they had endured. These laws were different from most others, nay, almost peculiar to the men to whom they belonged."[243]

[Pg185] I need not continue these notes as to the backwardness of portions of the country compared with its general level of culture, because I have dealt with the evidence elsewhere.[244] What I am anxious to point out here is that the faculty of such people as these to think, not in terms of modern science but in terms of their own psychological conditions, must have been pronounced. If they ever put the question to themselves as to the origin of things, they would answer themselves according to the life impressions they were then receiving, and according to the limited range of their actual knowledge. As with the creators of the traditional myths, the scientific inquirers of primitive times, so with these non-advanced people of later times, they would deal with the problems they did not understand in fashions suitable to their own understanding. It has always appeared to me that the impressions of the surrounding life are not sufficiently regarded in their[Pg186] influence upon primitive thought. They press down upon the mind, and enclose it within barriers so that it can only act through these surroundings. Child-life is, in this respect, much the same as the life of primitive man. A child thinks and acts in terms of his nursery, his school, or his playground. Thus a memory of my own is to the point. When quite a child, probably about eight or nine years old, I was entrusted with the changing of a small cheque drawn by my father in a country town where we were staying. I had never seen a cheque before. I remember the ceremony of writing it and the care with which the necessary instructions were given to me, and I remember the amazement with which I received the golden sovereigns. But my mind dwelt upon this strange thing called a cheque, and after a time I deliberately came to the conclusion that my father was allowed to get money for these cheques on condition only that he wrote them without a mistake and without a blot. The conception is absurd until we come to analyse the cause of it. My young life at that time was receiving its greatest impressions, its all-absorbing impressions, from my school exercises in writing. It was a copybook life for the time being, and when I turned to ask my question as to origins, as every human being has asked himself in turn, I could express myself only in copybook terms. It is so with the primitive mind. It can only express itself in the terms of its greatest impressions, and it is in this way that primitive animism, sympathetic magic and other conceptions obtained from the results of anthropological research, are to be found in much the same degree wherever humanity is found[Pg187] in primitive conditions. As Mr. Hickson puts it so well: "Just as the little black baby of the negro, the brown baby of the Malay, the yellow baby of the Chinaman, are in face and form, in gestures and habits, as well as in the first articulate sound they mutter, very much alike, so the mind of man, whether he be Aryan or Malay, Mongolian or Negrito, has, in the course of its evolution, passed through stages which are practically identical. In the intellectual childhood of mankind natural phenomena, or some other causes, of which we are at present ignorant, have induced thoughts, stories, legends, and myths, that in their essentials are identical among all the races of the world with which we are acquainted;"[245] or to take one other example from the experience of travellers, Mr. Mitchell, speaking of the Australians, says: "I found a native still there, and on my advancing towards him with a twig he shook another twig at me, waving it over his head, and at the same time intimating with it that we must go back. He and the boy then threw up dust at us with their toes (cf. 2 Sam. xvi. 13). These various expressions of hostility and defiance were too intelligible to be mistaken. The expressive pantomime of the man showed the identity of the human mind, however distinct the races or different the language."[246]

This identity is shown in many other ways to have been operating, perhaps to be operating still, upon minds not attuned to the civilisation around them. The resistance of agriculturists to change is well[Pg188] known.[247] The crooked ridges of the open-field system were believed to be necessary because they were supposed to deceive the devil,[248] while a superstitious dislike was entertained against winnowing machines, because they were supposed to interfere with the elements.[249] This is nothing but a modern example of sympathetic magic produced by the introduction of the new machine.

I need not go through the researches of the masters of anthropology to explain what the psychological evidence exactly amounts to, and the realms of primitive thought and experience which it connotes.[250] It will, however, be useful for the purpose of our present study, if we can find among the peasantry of our country (perchance from those districts where we have noted conditions under which primitive thought might retain a continuous hold) examples of belief or superstition which belongs rather to psychological than to traditional influences. The interpretation of dreams, the belief in spirit apparitions, the practice of charms, all belong to this branch of our subject, though I shall illustrate the points I wish to bring out by reference to less common departments.

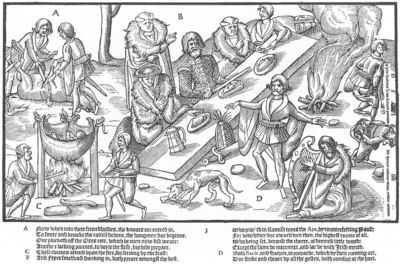

It was only in the seventeenth century that a learned[Pg189] divine of the Church of England was shocked to hear one of his flock repeat the evidence of his pagan beliefs in language which is as explicit as it is amusing; and I shall not be accused of trifling with religious susceptibilities if I quote a passage from a sermon delivered and printed in 1659—a passage which shows not a departure from Christianity either through ignorance or from the result of philosophic study or contemplation, but a sheer non-advance to Christianity, a passage which shows us an English pagan of the seventeenth century.

"Let me tell you a story," says the Reverend Mr. Pemble, "that I have heard from a reverend man out of the pulpit, a place where none should dare to tell a lye, of an old man above sixty, who lived and died in a parish where there had bin preaching almost all his time.... On his deathbed, being questioned by a minister touching his faith and hope in God, you would wonder to hear what answer he made: being demanded what he thought of God, he answers that he was a good old man; and what of Christ, that he was a towardly youth; and of his soule, that it was a great bone in his body; and what should become of his soule after he was dead, that if he had done well he should be put into a pleasant green meadow."[251]

Of the four articles of this singular creed, the first two depict an absence of knowledge about the central features of Christian belief, the latter two denote the existence of knowledge about some belief not known to English scholars of that time. If it had so happened[Pg190] that the Reverend Mr. Pemble had thought fit to tell his audience only of the first two articles of this creed, it would have been difficult to resist the suggestion that they presented us merely with an example of stupid, or, perhaps, impudent, blasphemy caused by the events of the day. But the negative nature of the first two items of the creed is counterbalanced by the positive nature of the second two items; and thus this example shows us the importance of considering evidence as to all phases of non-belief in Christianity.

Passing on to the two items of positive belief, it is to be noted that the soul resident in the body in the shape of a bone is no part of the early European belief, but equates rather with the savage idea which identifies the soul with some material part of the body, such as the eyes, the heart, or the liver; and it is interesting to note in this connection that the backbone is considered by some savage races, e.g., the New Zealanders, as especially sacred because the soul or spiritual essence of man resides in the spinal marrow.[252] And there is a well-known incident in folk-tales which seems to owe its origin to this group of ideas. This is where the hero having been killed, one of his bones tells the secret of his death, and thus acts the part of the soul-ghost.

In the pleasant green fields we trace the old faiths of the agricultural peasantry which, put into the words of Hesiod, tell us that "for them earth yields her[Pg191] increase; for them the oaks hold in their summits acorns, and in their midmost branches bees. The flocks bear for them their fleecy burdens ... they live in unchanged happiness, and need not fly across the sea in impious ships"—faiths which are in striking contrast to the tribal warrior's conception as set forth by the Saxon thane of King Eadwine of Northumbria. "This life," said this poetical thane, "is like the passage of a bird from the darkness without into a lighted hall where you, O King, are seated at supper, while storms, and rain, and snow rage abroad. The sparrow flying in at our door and straightway out at another is, while within, safe from the storm; but soon it vanishes into the darkness whence it came."

Such faiths as these, indeed, show us primitive ideas at their very roots. This seventeenth-century pagan depended upon himself for his faith. He worked out his own ideas as to the origin of soul and heaven and God and Christ. They were terms that had filtered down to him through the hard surroundings of his life, and he set to work to define them in the fashion of the primitive savage. We meet with other examples. Thus among the superstitions of Lancashire is one which tells us of the lingering belief in a long journey after death, when food is necessary to support the soul. A man having died of apoplexy, near Manchester, at a public dinner, one of the company was heard to remark: "Well, poor Joe, God rest his soul! He has at least gone to his long rest wi' a belly full o' good meat, and that's some consolation," and perhaps a still more remarkable instance is that of the woman buried in Cuxton Church, near Rochester, who directed by her[Pg192] will that the coffin was to have a lock and key, the key being placed in her dead hand, so that she might be able to release herself at pleasure.[253]

These people simply did not understand civilised thought or civilised religion. To escape from the pressure of trying to understand they turned to think for themselves, and thinking for themselves merely brought them back to the standpoint of primitive thought. It could hardly be otherwise. The working of the human mind is on the same plane wherever and whenever it operates or has operated. The difference in results arises from the enlarged field of observation. When the Suffolk peasant set to work to account for the existence of stones on his field by asserting that the fields produced the stones, and for the origin of the so-called "pudding-stone" conglomerate, that it was a mother stone and the parent of the pebbles,[254] he was beginning a first treatise on geology; and when the Hampshire peasant attributes the origin of the tutsan berries to having germinated in the blood of slaughtered Danes,[255] other counties following the same thought, I am not at all sure that he is not beginning all over again the primitive conception of the origin of plants.

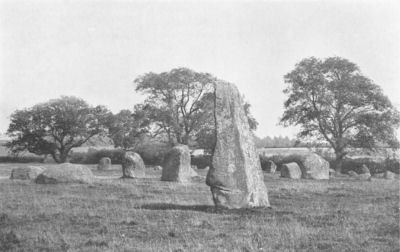

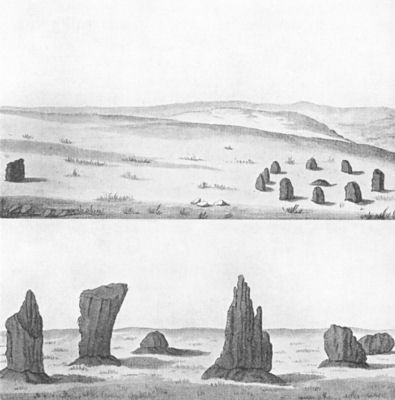

This beginning shows the mark of the primitive mind, and that it was operating in a country dominated by scientific thought is the phenomenon which makes it so important to consider psychological conditions [Pg193]among the problems of folklore. They account for some beliefs which may not contain elements of pure tradition. When the Mishmee Hill people of India affirm of a high white cliff at the foot of one of the hills that approaches the Burhampooter that it is the remains of the "marriage feast of Raja Sisopal with the daughter of the neighbouring king, named Bhismak, but she being stolen away by Krishna before the ceremony was completed, the whole of the viands were left uneaten and have since become consolidated into their present form,"[256] we can understand that the belief is in strict accord with the primitive conditions of thought of the Mishmee people. Can we understand the same conditions of the parallel English belief concerning the stone circle known as "Long Meg and her daughters,"[257] and of that at Stanton Drew;[258] or of the allied beliefs in Scotland that a huge upright stone, Clach Macmeas, in Loth, a parish of Sutherlandshire, was hurled to the bottom of the glen from the top of Ben Uarie by a giant youth when he was only one month old;[259] and in England that "the Hurlers," in Cornwall, were once men engaged in the game of hurling, and were turned into stone for playing on the Lord's Day; that the circle, known as "Nine Maidens," were maidens turned into stone for dancing on the Lord's Day;[260] that the stone circle at Stanton Drew represents serpents converted into stones by Keyna, a holy virgin of the[Pg194] fifth century;[261] and that the so-called snake stones found at Whitby were serpents turned into stones by the prayers of the Abbess Hilda.[262] These are only examples of the kind of beliefs entertained in all parts of the United Kingdom,[263] and they seem based upon psychological, rather than traditional conditions.

The giant and the witch, or wizard, are terms applied to the unknown personal agent. "The two standing stones in the neighbourhood of West Skeld are said to be the metamorphosis of two wizards or giants, who were on their way to plunder and murder the inhabitants of West Skeld; but not having calculated their time with sufficient accuracy, before they could accomplish their purpose, or retrace their steps to their dark abodes, the first rays of the morning sun appeared, and they were immediately transformed, and remain to the present time in the shape of two tall moss-grown stones of ten feet in height."[264] This is paralleled by the Merionethshire example of a large drift of stones about midway up the Moelore in Llan Dwywe, which was believed to be due to a witch who "was carrying her apron full of stones for some purpose to the top of the hill, and the string of the apron broke, and all the stones dropped on the spot, where they still remain under the name of Fedogaid-y-Widdon."[265] Giant and witch in these cases are generic terms by which the popular mind has conveyed a conception of the origin of these strange and remarkable[Pg195] monuments, whether natural or constructed by a long-forgotten people; and we cannot doubt that such beliefs are generated by the peasantry of civilisation from a mental conception not far removed from that of the primitive savage. Neither their religion nor their education was concerned with such things, so the peasants turned to their own realm and created a myth of origins suitable to their limited range of knowledge.

It may perhaps be urged that such beliefs as these are on the borderland of psychological and traditional influences. Witches and giants certainly belong to tradition, but on the other hand they are the common factors of the natural mind which readily attributes personal origins to impersonal objects. I am inclined on the whole to attribute the beliefs attachable to the unexplained boulders or unknown monoliths to the eternal questionings in the minds of the uncultured peasants of uncivilised countries similar to those of the unadvanced savage. That the peasant of civilisation should confine his questionings to the by-products of his surroundings and not to the greater subjects which occupy the minds of savages, is only because the greater subjects have already been answered for him by the Christian Church.[266]

[Pg196] There is a point, however, where psychological and traditional conditions are in natural conjunction, and I will just refer to this. That matters of legal importance should be preserved by the agency of tradition has already been shown to belong to that part of history for which there are no contemporary records, and its importance in this connection has been proved. Equally important from the psychological side is the fact that law is also preserved by tradition where people are unaccustomed to the use of writing, or by reason of their occupation have little use for writing. To illustrate this, I will quote an excellent note preserved by a writer on Cornish superstitions.

"There is an old 'vulgar error'—that no man can swear as a witness in a court of law to any thing he has seen through glass. This is based upon the formerly universal use of blown glass for windows, in which glass the constant recurrence of the greenish, and barely more than semi-transparent bull's eyes, so much distorted the view that it was unsafe for a spectator through glass to pledge his oath to what he saw going on outside. Now, through our present glass, this belief is relegated to the region of forgotten things, but nevertheless it has hold on Westcountry people still. I was, some years since, investigating the case of a derelict ship which had been found off the Scilly Islands, and towed by the pilots into a safe anchorage for the night. Next morning the pilots going out to complete their salvage, saw some men on board the derelict casting off the anchor rope by which they had secured her, but they distinctly declined to swear to the truth of what they had seen, and it turned out that they had seen through glass, by which they meant a telescope. In the same case I found that when these pilots (men intelligent much beyond the average, as all Scillonians are) had, on boarding the derelict (which had, of course,[Pg197] been deserted by her crew), found a living dog, they had deliberately thrown it overboard. They explained this act of cruelty to me by saying that a ship was not derelict if on board of her was found alive 'man, woman, child, dog, or cat.' And it turned out, on after-investigation, that these were the very words used in an obsolete Act of Parliament of one of the early Plantagenet kings, forgotten centuries ago by the English people, but borne in mind as a living fact by the Scillonians."[267]

In some special departments elementary psychological conditions operate in a considerable degree—operate to produce not waifs and strays of primitive thought and belief, but whole classes. Thus in the curious accretion of superstition around the objects connected with church worship, the same agencies are at work. The general characteristic of popular beliefs which originated with, or have grown up around the consecrated objects of the Church, is that such objects are beneficent in their action when employed for any given purpose. Thus, as Henderson says of the North of England, "a belief in the efficacy of the sacred elements in the Eucharist for the cure of bodily disease is widely spread." Silver rings, made from the offertory money, are very generally worn for the cure of epilepsy. Water that had been used in baptism was believed in West Scotland to have virtue to cure many distempers; it was a preventive against witchcraft, and eyes bathed with it would never see a ghost. Dalyell puts the evidence very succinctly. "Everything relative to sanctity was deemed a preservative. Hence the relics of saints, the touch of their clothes, of their tombs, and[Pg198] even portions of structures consecrated to divine offices were a safeguard near the person. A white marble altar in the church of Iona, almost entire towards the close of the seventeenth century, had disappeared late in the eighteenth, from its demolition in fragments to avert shipwreck." And so what has been consecrated, must not be desecrated. In Leicestershire and Northamptonshire there is a superstitious idea that the removal or exhumation of a body after interment bodes death or some terrible calamity to the surviving members of the deceased's family.[268]

In the West of Ireland there were usually found upon the altars of the small missionary churches one or more oval stones, either natural waterwashed pebbles or artificially shaped and very smooth, and these were held in the highest veneration by the peasantry as having belonged to the founders of the churches, and were used for a variety of purposes, as the curing of diseases, taking oaths upon them, etc.[269] Similarly the using of any remains of destroyed churches for profane purposes was believed to bring misfortune,[270] while the land which once belonged to the church of St. Baramedan, in the parish of Kilbarrymeaden, county Waterford, "has long been highly venerated by the common people, who attribute to it many surprising virtues."[271] In 1849 the people of Carrick were in the habit of carrying away[Pg199] from the churchyard portions of the clay of a priest's grave and using it as a cure for several diseases, and they also boiled the clay from the grave of Father O'Connor with milk and drank it.[272] One of the superstitious fancies of the Connemara folk in 1825 was credulity with respect to the gospels, as they are called, which "they wear round their neck as a charm against danger and disease. These are prepared by the priest, and sold by him at the price of two or three tenpennies. It is considered sacrilege in the purchaser to part with them at any time, and it is believed that the charm proves of no efficacy to any but the individual for whose particular benefit the priest has blessed it. The charm is written on a scrap of paper and enclosed in a small cloth bag, marked on one side with the letters I.H.S. On one side of the paper is written the Lord's Prayer, and after it a great number of initial letters."[273]

Such examples could be multiplied indefinitely, but no folklorist has properly classified such beliefs and endeavoured to ascertain their place in the science of folklore.[274] It is clear they have arisen not from tradition, but from a new force acting on minds which were not yet free to receive new influences without going back to old methods of thought.

How completely the sanctity of the church exercises a constant influence upon the minds of men, thus substituting a new form of belief when older forms were[Pg200] thrust on one side by the advance of the new religion, is perhaps best illustrated by a practice in early Christian times for giving sanctity to the oath. Among the Jews the altar in the Temple was resorted to by litigants in order that the oath might be taken in the presence of Yahveh himself, and "so powerful was the impression of this upon the Christian mind, that in the early ages of the Church there was a popular superstition that an oath taken in a Jewish synagogue was more binding and more efficient than anywhere else."[275] In exactly the same way the altar of the Christian Church is used in popular belief after its use in Church ceremonial has been discontinued. Thus, to get in beneath the altar of St. Hilary Church, Anglesey, by means of an open panel and then turn round and come out is to ensure life for the coming year,[276] and the white marble altar in Iona which has been entirely demolished by fragments of it being used to avert shipwreck has already been referred to.[277] These are cases where there has been a throwing back from the new religion to the objects connected with the old religion, and they are paralleled by the practice of Protestants appealing to the Roman Catholic priesthood for protection against witchcraft, and of Nonconformists believing that the clergy of the Episcopal Church possess superior powers over evil spirits.[278]

[Pg201] Psychological evidence is therefore important. One can never be quite sure to what extent civilised man is free from creating fresh myths in place of acquired scientific result, and to what extent this influences the production of primitive beliefs, or allows of the acceptance of traditional belief on new ground. The great mass of traditional belief has come through the ages traditionally, that is, from parent to child, from neighbour to neighbour, from class to class, from locality to locality, generation after generation. Occasionally this main current of the traditional life of a people is swollen by small side streams from fresh psychological sources. Individual examples, such as those I have cited, have perhaps always been present, but their effect must have died away with the passing of those with whom they originated. There are, however, stronger effects than these, coming not from individuals, but from classes. Thus the votaries and enemies of witchcraft produced a more lasting effect. Witchcraft, as Dr. Karl Pearson, I think, conclusively proves, and as I have helped to prove,[279] is founded upon traditional belief and custom, but its remarkable revival in the Middle Ages was in the main a psychological phenomenon. Traditional practices, traditional formulæ, and traditional beliefs are no doubt the elements of witchcraft, but it was not the force of tradition which produced the miserable doings of the Middle Ages and of the seventeenth century against witches. These were due to a psychological force, partly generated by the newly acquired power of the people to read the[Pg202] Bible for themselves, and so to apply the witch stories of the Jews to neighbours of their own who possessed powers or peculiarities which they could not understand, and partly generated by the carrying on of traditional practices by certain families or groups of persons who could only acquire knowledge of such practices by initiation or family teaching. Lawyers, magistrates, judges, nobles, and monarchs are concerned with witchcraft. These are not minds which have been crushed by civilisation, but minds which have misunderstood it or have misused it. It is unnecessary, and it is of course impossible on this occasion to trace out the psychic issues which are contained in the facts of witchcraft, but it may be advisable to illustrate the point by one or two references.

I will note a few modern examples of the belief in witchcraft:—

"In 1879 extraordinary stories were current among the populace of Caergwrle. Mrs. Braithwaite supplied a Mrs. Williams with milk, but afterwards refused to serve her, and the cause was as follows: Mrs. Braithwaite had up to that time been very successful in churning her butter, but about a month ago the butter would not come. She tried every known agency; she washed and dried her bats, but all to no purpose. The milk would not yield an ounce of butter. Under the circumstances she said Mrs. Williams had witched her. The neighbours believed it, and Mrs. Williams was generally called a witch. Hearing these reports, Mrs. Williams went to Mrs. Braithwaite to expostulate with her, when Mrs. Braithwaite said, 'Out, witch! If you don't leave here, I'll shoot you.' Mrs. Williams thereupon applied to the Caergwrle bench of magistrates for a protection order against Mrs. Braithwaite. She assured the Bench she was[Pg203] in danger, as every one believed she was a witch. The Clerk: What do they say is the reason? Applicant: Because she cannot churn the milk. Mr. Kryke: Do they see you riding a broomstick? Applicant (seriously): No, sir. The Bench instructed the police officer to caution Mrs. Braithwaite against repeating the threats."[280]

The next example is from Lancashire:—

"At the East Dereham Petty Sessions, William Bulwer, of Etling Green, was charged with assaulting Christiana Martins, a young girl, who resided near the Etling Green toll-bar. Complainant deposed that she was 18 years of age, and on Wednesday, the 2nd inst., the defendant came to her and abused her. The complainant, who looks scarce more than a child, repeated, despite the efforts of the magistrates' clerk to stop her, and without being in the least abashed, some of the worst language it was possible to conceive—conversation of the most gross description, alleged to have taken place between herself and the defendant. They appeared to have got from words to blows and, while trying to fasten the gate, the defendant hit her across the hand with a stick. She alleged that there was no cause for the abuse and the assault, so far as she knew, and in reply to rigid cross-examination as to the origin of the quarrel, adhered to this statement. Mrs. Susannah Gathercole also corroborated the statement as to the assault, adding that the defendant said the complainant's mother was a witch. Defendant then blazed forth in righteous indignation, and, when the witness said she knew no more about the origin of the quarrel, he said, 'Mrs. Martins is an old witch, gentlemen, that is what she is, and she charmed me, and I got no sleep for her for three nights, and one night at half-past eleven o'clock, I got up because I could not sleep, and went out and found a "walking toad" under a clod that had been dug up with a three-pronged fork. That is why I could not[Pg204] rest; she is a bad old woman; she put this toad under there to charm me, and her daughter is just as bad, gentlemen. She would bewitch any one; she charmed me, and I got no rest day or night for her, till I found this "walking toad" under the turf. She dug a hole and put it there to charm me, gentlemen, that is the truth. I got the toad out and put it in a cloth, and took it upstairs and showed it to my mother, and "throwed" it into the pit in the garden. She went round this here "walking toad" after she had buried it, and I could not rest by day or sleep by night till I found it. The Bench: Do you go to church? Defendant: Sometimes I go to church, and sometimes to chapel, and sometimes I don't go nowhere. Her mother is bad enough to do anything; and to go and put the "walking toad" in the hole like that, for a man which never did nothing to her, she is not fit to live, gentlemen, to go and do such a thing; it is not as if I had done anything to her. She looks at lots of people, and I know she will do some one harm. The Chairman: Do you know this man, Superintendent Symons? Is he sane? Superintendent Symons: Yes, sir; perfectly."[281]

In Somerset belief in witchcraft still lingers in nooks and corners of the west, as appears from a case brought before the magistrates of the Wiveliscombe division.

"Sarah Smith, the wife of a marine store dealer, residing at Golden Hill, was for some time ill and confined to her bed. Finding that the local doctor could not cure her, she sent for a witch doctor of Taunton. He duly arrived by train on St. Thomas's day. Smith inquired his charge, and was informed he usually charged 11s., remarking that unless he took it from the person affected his incantation would be of no avail. Smith then handed it to his wife, who gave it to the witch doctor, and he returned 1s. to her. He then[Pg205] proceeded to foil the witch's power over his patient by tapping her several times on the palm of her hand with his finger, telling her that every tap was a stab on the witch's heart. This was followed by an incantation. He then gave her a parcel of herbs (which evidently consisted of dried bay leaves and peppermint), which she was to steep and drink. She was to send to a blacksmith's shop and get a donkey's shoe made, and nail it on her front door. He then departed."[282]

Such examples as these may be added to from various parts of the country, but they do not compare with the terrible case at Clonmel, in county Tipperary, which occurred in 1895. The evidence showed that the husband, father, and mother of the victim, together with several other persons, were concerned in this matter, and one of the witnesses, Mary Simpson, stated "that on the night of March 14th she saw Cleary forcibly administer herbs to his wife, and when the woman did not answer when called upon in the name of the Trinity to say who she was, she was placed on the fire by Cleary and the others. Mrs. Cleary did not appear to be in her right senses. She was raving."[283] The whole record of the trial is of the most amazing description, pointing back to a system of belief which, if based upon traditional practices, has been fed by entirely modern influences. Such records as these stretch back through the ages, and almost every village, certainly every county in the United Kingdom, has its records of trials for witchcraft, in which clergy and layman, judge, jury, and victim play strange parts,[Pg206] if we consider them as members of a civilised community. Superstition which has been preserved by the folk as sacred to their old faiths, preserved by tradition, has remained the cherished possession, generally in secret, of those who practise it. The belief in witchcraft is a different matter. Though it has traditional rites and practices it has been kept alive by a cruel and crude interpretation of its position among the faiths of the Bible, and it has thus received fresh life.

The miserable records of witchcraft illustrate in a way no other subject can how the human mind, when untouched by the influences of advanced culture, has the tendency to revert to traditional culture, and they demonstrate how strongly embedded in human memory is the great mass of traditional culture. The outside civilisation, religious or scientific, has not penetrated far. Science has only just begun her great work, and religion has been spending most of her efforts in endeavouring to displace a set of beliefs which she calls superstition, by a set of superstitions which she calls revelation. Not only have the older faiths not been eradicated by this, but the older psychological conditions have not been made to disappear. The folklorist has to make note of this obviously significant fact, and must therefore deal with both sides of the question, the traditional and the psychological, and because by far the greater importance belongs to the former it does not do to neglect the importance, though the lesser importance, of the latter.

It assists the student of tradition in many ways. People who will still explain for themselves in primitive fashion phenomena which they do not understand,[Pg207] and who remain content with such primitive explanations instead of relying upon the discoveries of science, are just the people to retain with strong persistence the traditional beliefs and ideas which they obtained from their fathers, and to acquire other traditional beliefs and ideas which they obtain from neighbours. One often wonders at the "amazing toughness" of tradition, and in the psychological conditions which have been indicated will be found one of the necessary explanations.

FOOTNOTES:

[237] Dalyell, Darker Superstitions of Scotland, 197-198.

[238] Robertson, Agriculture of Inverness-shire. For Argyllshire see New Stat. Account of Scotland, vii. 346; Brown, Early Descriptions of Scotland, 12, 49, 99.

[239] Wilde, Catalogue of Museum of Royal Irish Academy, 99; Joyce, Social Hist. of Anc. Ireland, ii. 27.

[240] Tour in Ireland, 1775, p. 144; Gent. Mag., v. 680.

[241] Hutchinson, Hist. of Cumberland, i. 216.

[242] James Clarke, Survey of the Lakes, 1789, p. xiii; Berwickshire Nat. Field Club, ix. 512.

[243] Clarke, Survey of the Lakes, pp. x, xv. Referring to the statutes enacted as a result of the Commissioners' work the facts are as follows: There were certain franchises in North and South Tynedale and Hexhamshire, by virtue of which the King's writ did not run there. [Tynedale, though on the English side of the border, was an ancient franchise of the Kings of Scotland.] In 1293 Edward I. confirmed this grant in favour of John of Balliol (1 Rot. Parl., 114-16), and the inhabitants took advantage of this immunity to make forays and commit outrages in neighbouring counties. In the year 1414, at the Parliament holden at Leicester, "grievous complaints" of these outrages were made "by the Commons of the County of Northumberland." It was accordingly provided (2 Henry V., cap. 5) that process should be taken against such offenders under the common law until they were outlawed; and that then, upon a certificate of outlawry made to lords of franchises in North and South Tynedale and Hexhamshire, the offender's lands and goods should be forfeited. In 1421 the provisions of this statute were extended to like offenders in Rydesdale, where also the King's writ did not run (9 Henry V., cap. 7). Still these excesses continued in Tynedale. By an enactment of Henry VII. (2 Henry VII., cap. 9) this "lordship and bounds" were annexed to the county of Northumberland. "Forasmuch," the preamble sets forth, "as the inhabitants and dwellers within the lordships and bounds of North and South Tyndale, not only in their own persons, but also oftentimes accompanied and confedered with Scottish ancient enemies to this realm, have at many seasons in time past committed and done, and yet daily and nightly commit and do, great and heinous murders, robberies, felonies, depredations, riots and other great trespasses upon the King our Sovereign lord's true and faithful liege people and subjects, inhabiters and dwellers within the shires of Northumberland, Cumberland, and Westmoreland, Exhamshire [sic], the bishopric of Durham and in a part of Yorkshire, in which treasons, murders, robberies, felonies, and other the premises, have not in time past in any manner of form been punished after the order and course of the common law, by reason of such franchise as was used within the same while it was in the possession of any other lord or lords than our Sovereign lord, and thus for lack of punishment of these treasons, murders, robberies and felonies, the King's true and faithful liege people and subjects, inhabiters and dwellers within the shires and places before rehearsed, cannot be in any manner of surety of their bodies or goods, neither yet lie in their own houses, but either to be murdered or taken or carried into Scotland and there ransomed, to their great destruction of body and goods, and utter impoverishing for ever, unless due and hasty remedy be had and found," it is therefore provided that North and South Tynedale shall from thenceforth be gildable, and part of the shire of Northumberland, that no franchise shall stand good there, and the King's writ shall run, and his officers and all their warrants be obeyed there as in every other part of that shire. Further, lessees of lands within the bounds are to enter into recognisances in two sureties to appear and answer all charges.

[244] See my Ethnology in Folklore, cap. vi.

[245] Hickson, North Celebes, 240.

[246] Mitchell's Australian Expeditions, i. 246.

[247] See my Village Community, 18; Stewart's Highlanders of Scotland, i. 147, 228.

[248] Notes and Queries, second series, iv. 487.

[249] Wild, Highlands, Orcadia and Skye, 196.

[250] The psychology of primitive races is now receiving scientific attention, thanks chiefly to Dr. Haddon and the scholars who accompanied him upon his Torres Straits expedition in 1898. The volume of the memoirs of this expedition which relates to psychology has already been published, and students should consult it as an example of scientific method.

[251] One is reminded of the famous Shakespearian emendation whereby Falstaff on his death-bed "babbled o' green fields."

[252] Shortland, New Zealanders, 107. An Algonquin backbone story is quoted by MacCulloch, Childhood of Fiction, 92, and he says, "the spine is held by many people to be the seat of life," 93 and cf. III. Cf. Frazer, Adonis, Attis, and Osiris, 277.

[253] Gent. Mag. Lib., Popular Superstitions, 122.

[254] County Folklore, Suffolk, 2.

[255] Hardwick's Science Gossip, vi. 281; cf. Worsaae, Danes and Norwegians, 25.

[256] Journ. Asiatic Soc., Bengal, xiv. 479.

[257] King, Munimenta Antiqua, i. 195-6; Gent. Mag. Lib., Archæology, i. 319-321; Hutchinson, Hist. Cumberland, i. 226.

[258] Arch. Journ., xv. 204.

[259] Sinclair, Stat. Acct. of Scotland, xv. 191.

[260] Journ. Anthrop. Inst., i. 2; Gent. Mag. Lib., Archæology, i. 21.

[261] Archæologia, xxv. 198.

[262] Gent. Mag., 1751, pp. 110, 182.

[263] Some Irish examples are collected in Folklore Record, v. 169-172.

[264] Sinclair, Stat. Acct. of Scotland, xv. 111.

[265] Trans. Cymmrodorion Soc. (1822), i. 170.

[266] It is not worth while, perhaps, to pursue this part of our subject into further regions. It is to be sought for in innumerable pamphlets, such, for instance, as those relating to the Civil War. Beesley, Hist. of Banbury, 334, mentions one, the title of which I will quote: "A great Wonder in Heaven shewing the late Apparitions and prodigious noyses of War and Battels seen on Edge Hill neere Keinton," and the contents are "Certified under the hands of William Wood Esq and Justice for the Peace in the said Countie, Samuel Marshall, Preacher of God's Word in Keinton, and other Persons of Qualitie." The date is exactly three months after the battle of Edgehill, "London, printed for Thomas Jackson, January 23rd, 1642-3."

[267] West of England Magazine, February, 1888.

[268] Henderson, Folklore of the Northern Counties, 146; Napier, Folklore of West of Scotland, 140; Dalyell, Darker Superstitions of Scotland, 142; Choice Notes (Folklore), 8; Brand, iii. 300; Dyer, English Folklore, 146, 153 (Hereford, Lincoln, and Yorks).

[269] Wilde, Catalogue of Royal Irish Academy, 131.

[270] Folklore Record, iv. 105.

[271] Rev. R.H. Ryland, Hist. of Waterford, 271.

[272] Wilde, Beauties of the Boyne, 45; Croker, Researches in South of Ireland, 170; Revue Celtique, v. 358.

[273] Blake, Letters from the Irish Highlands, 130-131.

[274] Church Folklore, by Rev. J.E. Vaux, is a collection of material, and does not attempt to give any indication of its value.

[275] Lea, Superstition and Force, 28.

[276] Journ. Brit. Arch. Assoc., xxv. 142; Rev. W. Bingley, North Wales, 216-217.

[277] Sacheverell, Voyage to Isle of Man, 132.

[278] Tylor, Primitive Culture, i. 115; Landt, Origin of the Priesthood, 85; Henderson, Folklore of Northern Counties, 32-33; Folklore Record, i. 46.

[279] Pearson's Chances of Death, ii. cap. ix., "Woman as Witch;" Gomme, Ethnology in Folklore, 48-62.

[280] Daily Chronicle, 15th February, 1879.

[281] Leigh Chronicle, 19th April, 1879.

[282] Somerset County Gazette, 22nd January, 1881.

[283] Standard, 3rd April, 1895. The full details are reprinted in Folklore, vi. 373-384.