Adapted from the Project Gutenberg EBook of Legends of the Middle Ages, by H.A. Guerber

One of the favorite heroes of early mediaeval literature is Charlemagne, whose name is connected with countless romantic legends of more or less antique origin. The son of Pepin and Bertha the "large footed," this monarch took up his abode near the Rhine to repress the invasions of the northern barbarians, awe them into submission, and gradually induce them to accept the teachings of the missionaries he sent to convert them.

[Sidenote: The champion of Christianity.] As Charlemagne destroyed the Irminsul, razed heathen temples and groves, abolished the Odinic and Druidic forms of worship, conquered the Lombards at the request of the Pope, and defeated the Saracens in Spain, he naturally became the champion of Christianity in the chronicles of his day. All the heroic actions of his predecessors (such as Charles Martel) were soon attributed to him, and when these legends were turned into popular epics, in the tenth and eleventh centuries, he became the principal hero of France. The great deeds of his paladins, Roland, Oliver, Ogier the Dane, Renaud de Montauban, and others, also became the favorite theme of the poets, and were soon translated into every European tongue.

The Latin chronicle, falsely attributed to Bishop Turpin, Charlemagne's prime minister, but dating from 1095, is one of the oldest versions of Charlemagne's fabulous adventures now extant. It contains the mythical account of the battle of Roncesvalles (Vale of Thorns), told with infinite repetition and detail so as to give it an appearance of reality.

[Sidenote: Chanson de Roland.] Einhard, the son-in-law and historian of Charlemagne, records a partial defeat in the Pyrenees in 777-778, and adds that Hroudlandus was slain. From this bald statement arose the mediaeval "Chanson de Roland," which was still sung at the battle of Hastings. The probable author of the French metrical version is Turoldus; but the poem, numbering originally four thousand lines, has gradually been lengthened, until now it includes more than forty thousand. There are early French, Latin, German, Italian, English, and Icelandic versions of the adventures of Roland, which in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were turned into prose, and formed the basis of the "Romans de Chevalerie," which were popular for so many years. Numerous variations can, of course, be noted in these tales, which have been worked over again by the Italian poets Ariosto and Boiardo, and even treated by Buchanan in our day.

It would be impossible to give in this work a complete synopsis of all the chansons de gestes referring to Charlemagne and his paladins, so we will content ourselves with giving an abstract of the most noted ones and telling the legends which are found in them, which have gradually been woven around those famous names and connected with certain localities.

[Sidenote: Charlemagne and the heavenly message.] We are told that Charlemagne, having built a beautiful new palace for his use, overlooking the Rhine, was roused from his sleep during the first night he spent there by the touch of an angelic hand, and, to his utter surprise, thrice heard the heavenly messenger bid him go forth and steal. Not daring to disobey, Charlemagne stole unnoticed out of the palace, saddled his steed, and, armed cap-a-pie, started out to fulfill the angelic command.

He had not gone far when he met an unknown knight, evidently bound on the same errand. To challenge, lay his lance in rest, charge, and unhorse his opponent, was an easy matter for Charlemagne. When he learned that he had disarmed Elbegast (Alberich), the notorious highwayman, he promised to let him go free if he would only help him steal something that night.

Guided by Elbegast, Charlemagne, still incognito, went to the castle of one of his ministers, and, thanks to Elbegast's cunning, penetrated unseen into his bedroom. There, crouching in the dark, Charlemagne overheard him confide to his wife a plot to murder the emperor on the morrow. Patiently biding his time until they were sound asleep, Charlemagne picked up a worthless trifle, and noiselessly made his way out, returning home unseen. On the morrow, profiting by the knowledge thus obtained, he cleverly outwitted the conspirators, whom he restored to favor only after they had solemnly sworn future loyalty. As for Elbegast, he so admired the only man who had ever succeeded in conquering him that he renounced his dishonest profession to enter the emperor's service.

In gratitude for the heavenly vision vouchsafed him, the emperor named his new palace Ingelheim (Home of the Angel), a name which the place has borne ever since. This thieving episode is often alluded to in the later romances of chivalry, where knights, called upon to justify their unlawful appropriation of another's goods, disrespectfully remind the emperor that he too once went about as a thief.

[Sidenote: Frastrada's magic ring.] When Charlemagne's third wife died, he married a beautiful Eastern princess by the name of Frastrada, who, aided by a magic ring, soon won his most devoted affection. The new queen, however, did not long enjoy her power, for a dangerous illness overtook her. When at the point of death, fearful lest her ring should be worn by another while she was buried and forgotten, Frastrada slipped the magic circlet into her mouth just before she breathed her last.

Solemn preparations were made to bury her in the cathedral of Mayence (where a stone bearing her name could still be seen a few years ago), but the emperor refused to part with the beloved body. Neglectful of all matters of state, he remained in the mortuary chamber day after day. His trusty adviser, Turpin, suspecting the presence of some mysterious talisman, slipped into the room while the emperor, exhausted with fasting and weeping, was wrapped in sleep. After carefully searching for the magic jewel, Turpin discovered it, at last, in the dead queen's mouth.

"He searches with care, though with tremulous haste,

For the spell that bewitches the king;

And under her tongue, for security placed,

Its margin with mystical characters traced,

At length he discovers a ring."

SOUTHEY, King Charlemain.

[Sidenote: Turpin and the magic ring.] To secure this ring and slip it on his finger was but the affair of a moment; but just as Turpin was about to leave the room the emperor awoke. With a shuddering glance at the dead queen, Charlemagne flung himself passionately upon the neck of his prime minister, declaring that he would never be quite inconsolable as long as he was near.

Taking advantage of the power thus secured by the possession of the magic ring, Turpin led Charlemagne away, forced him to eat and drink, and after the funeral induced him to resume the reins of the government. But he soon wearied of his master's constant protestations of undying affection, and ardently longed to get rid of the ring, which, however, he dared neither to hide nor to give away, for fear it should fall into unscrupulous hands.

Although advanced in years, Turpin was now forced to accompany Charlemagne everywhere, even on his hunting expeditions, and to share his tent. One moonlight night the unhappy minister stole noiselessly out of the imperial tent, and wandered alone in the woods, cogitating how to dispose of the unlucky ring. As he walked thus he came to a glade in the forest, and saw a deep pool, on whose mirrorlike surface the moonbeams softly played. Suddenly the thought struck him that the waters would soon close over and conceal the magic ring forever in their depths; and, drawing it from his finger, he threw it into the pond. Turpin then retraced his steps, and soon fell asleep. On the morrow he was delighted to perceive that the spell was broken, and that Charlemagne had returned to the old undemonstrative friendship which had bound them for many a year.

"Overjoy'd, the good prelate remember'd the spell,

And far in the lake flung the ring;

The waters closed round it; and, wondrous to tell,

Released from the cursed enchantment of hell,

His reason return'd to the king."

SOUTHEY, King Charlemain.

Charlemagne, however, seemed unusually restless, and soon went out to hunt. In the course of the day, having lost sight of his suite in the pursuit of game, he came to the little glade, where, dismounting, he threw himself on the grass beside the pool, declaring that he would fain linger there forever. The spot was so charming that he even gave orders, ere he left it that night, that a palace should be erected there for his use; and this building was the nucleus of his favorite capital, Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen).

"But he built him a palace there close by the bay,

And there did he love to remain;

And the traveler who will, may behold at this day

A monument still in the ruins at Aix

Of the spell that possess'd Charlemain."

SOUTHEY, King Charlemain.

According to tradition, Charlemagne had a sister by the name of Bertha, who, against his will, married the brave young knight Milon. Rejected by the emperor, and therefore scorned by all, the young couple lived in obscurity and poverty. They were very happy, however, for they loved each other dearly, and rejoiced in the beauty of their infant son Roland, who even in babyhood showed signs of uncommon courage and vigor.

[Sidenote: Charlemagne and the boy Roland.] One version of the story relates, however, that Milon perished in a flood, and that Bertha was almost dying of hunger while her brother, a short distance away, was entertaining all his courtiers at his board. Little Roland, touched by his mother's condition, walked fearlessly into the banquet hall, boldly advanced to the table, and carried away a dishful of meat. As the emperor seemed amused at the little lad's fearlessness, the servants did not dare to interfere, and Roland bore off the dish in triumph.

A few minutes later he reentered the hall, and with equal coolness laid hands upon the emperor's cup, full of rich wine. Challenged by Charlemagne, the child then boldly declared that he wanted the meat and wine for his mother, a lady of high degree. In answer to the emperor's bantering questions, he declared that he was his mother's cupbearer, her page, and her gallant knight, which answers so amused Charlemagne that he sent for her. He then remorsefully recognized her, treated her with kindness as long as she lived, and took her son into his own service.

Another legend relates that Charlemagne, hearing that the robber knight of the Ardennes had a priceless jewel set in his shield, called all his bravest noblemen together, and bade them sally forth separately, with only a page as escort, in quest of the knight. Once found, they were to challenge him in true knightly fashion, and at the point of the lance win the jewel he wore. A day was appointed when, successful or not, the courtiers were to return, and, beginning with the lowest in rank, were to give a truthful account of their adventures while on the quest.

All the knights departed and scoured the forest of the Ardennes, each hoping to meet the robber knight and win the jewel. Among them was Milon, accompanied by his son Roland, a lad of fifteen, whom he had taken as page and armor-bearer. Milon had spent many days in vain search for the knight, when, exhausted by his long ride, he dismounted, removed his heavy armor, and lay down under a tree to sleep, bidding Roland keep close watch during his slumbers.

[Sidenote: Roland and the jewel.] Roland watched faithfully for a while; then, fired by a desire to distinguish himself, he donned his father's armor, sprang on his steed, and rode into the forest in search of adventures. He had not gone very far when he saw a gigantic horseman coming to meet him, and, by the dazzling glitter of a large stone set in his shield, he recognized in him the invincible knight of the Ardennes. Afraid of nothing, however, the lad laid his lance in rest when challenged to fight, and charged so bravely that he unhorsed the knight. A fearful battle on foot ensued, where many gallant blows were given and received; yet the victory finally remained with Roland. He slew his adversary, and wrenching the jewel from his shield, hid it in his breast. Then, riding rapidly back to his sleeping father, Roland laid aside the armor, and removed all traces of a bloody encounter. When Milon awoke he resumed the quest, and soon came upon the body of the dead knight. When he saw that another had won the jewel, he was disappointed indeed, and sadly rode back to court, to be present on the appointed day.

Charlemagne, seated on his throne, bade the knights appear before him, and relate their adventures. One after another strode up the hall, followed by an armor-bearer holding his shield, and all told of finding the knight slain and the jewel gone, and produced head, hands, feet, or some part of his armor, in token of the truth of their story. Last of all came Milon, with lowering brows, although Roland walked close behind him, proudly holding his shield, in the center of which the jewel shone radiant. Milon related his search, and reported that he too had found the giant knight slain and the jewel gone. A shout of incredulity made him turn his head. But when he saw the jewel blazing on his shield he appeared so amazed that Charlemagne questioned Roland, and soon learned how it had been obtained. In reward for his bravery in this encounter, Roland was knighted and allowed to take his place among his uncle's paladins, of which he soon became the most renowned.

Charlemagne, according to the old chanson de geste entitled "Ogier le Danois," made war against the King of Denmark, defeated him, and received his son Ogier (Olger or Holger Danske) as hostage. The young Danish prince was favored by the fairies from the time of his birth, six of them having appeared to bring him gifts while he was in his cradle. The first five promised him every earthly bliss; while the sixth, Morgana, foretold that he would never die, but would dwell with her in Avalon.

[Sidenote: Ogier king of Denmark.] Ogier the Dane, owing to a violation of the treaty on his father's part, was soon confined in the prison of St. Omer. There he beguiled the weariness of captivity by falling in love with, and secretly marrying, the governor's daughter Bellissande. Charlemagne, being about to depart for war, and wishing for the hero's help, released him from captivity; and when Ogier returned again to France he heard that Bellissande had borne him a son, and that, his father having died, he was now the lawful king of Denmark.

Ogier the Dane then obtained permission to return to his native land, where he spent several years, reigning so wisely that he was adored by all his subjects. Such is the admiration of the Danes for this hero that the common people still declare that he is either in Avalon, or sleeping in the vaults of Elsinore, and that he will awaken, like Frederick Barbarossa, to save his country in the time of its direst need.

"'Thou know'st it, peasant! I am not dead;

I come back to thee in my glory.

I am thy faithful helper in need,

As in Denmark's ancient story.'"

INGEMANN, Holder Danske.

After some years spent in Denmark, Ogier returned to France, where his son, now grown up, had a dispute with Prince Chariot [Ogier and Charlemagne.] over a game of chess. The dispute became so bitter that the prince used the chessboard as weapon, and killed his antagonist with it. Ogier, indignant at the murder, and unable to find redress at the hands of Charlemagne, insulted him grossly, and fled to Didier (Desiderius), King of Lombardy, with whom the Franks were then at feud.

Several ancient poems represent Didier on his tower, anxiously watching the approach of the enemy, and questioning his guest as to the personal appearance of Charlemagne. These poems have been imitated by Longfellow in one of his "Tales of a Wayside Inn."

"Olger the Dane, and Desiderio,

King of the Lombards, on a lofty tower

Stood gazing northward o'er the rolling plains,

League after league of harvests, to the foot

Of the snow-crested Alps, and saw approach

A mighty army, thronging all the roads

That led into the city. And the King

Said unto Olger, who had passed his youth

As hostage at the court of France, and knew

The Emperor's form and face, 'Is Charlemagne

Among that host?' And Olger answered, 'No.'"

LONGFELLOW, Tales of a Wayside Inn.

This poet, who has made this part of the legend familiar to all English readers, then describes the vanguard of the army, the paladins, the clergy, all in full panoply, and the gradually increasing terror of the Lombard king, who, long before the emperor's approach, would fain have hidden himself underground. Finally Charlemagne appears in iron mail, brandishing aloft his invincible sword "Joyeuse," and escorted by the main body of his army, grim fighting men, at the mere sight of whom even Ogier the Dane is struck with fear.

"This at a single glance Olger the Dane

Saw from the tower; and, turning to the King,

Exclaimed in haste: 'Behold! this is the man

You looked for with such eagerness!' and then

Fell as one dead at Desiderio's feet."

LONGFELLOW, Tales of a Wayside Inn.

Charlemagne soon overpowered the Lombard king, and assumed the iron crown, while Ogier escaped from the castle in which he was besieged. Shortly after, however, when asleep near a fountain, the Danish hero was surprised by Turpin. When led before Charlemagne, he obstinately refused all proffers of reconciliation, and insisted upon Charlot's death, until an angel from heaven forbade his asking the life of Charlemagne's son. Then, foregoing his revenge and fully reinstated in the royal good graces, Ogier, according to a thirteenth-century epic by Adenet, successfully encountered a Saracenic giant, and in reward for his services received the hand of Clarice, Princess of England, and became king of that realm.

[Sidenote: Ogier in the East.] Weary of a peaceful existence, Ogier finally left England, and journeyed to the East, where he successfully besieged Acre, Babylon and Jerusalem. On his way back to France, the ship was attracted by the famous lodestone rock which appears in many mediaeval romances, and, all his companions having perished, Ogier wandered alone ashore. There he came to an adamantine castle, invisible by day, but radiant at night, where he was received by the famous horse Papillon, and sumptuously entertained. On the morrow, while wandering across a flowery meadow, Ogier encountered Morgana the fay, who gave him a magic ring. Although Ogier was then a hundred years old, he no sooner put it on than he became young once more. Then, having donned the golden crown of oblivion, he forgot his home, and joined Arthur, Oberon, Tristan, and Lancelot, with whom he spent two hundred years in unchanged youth, enjoying constant jousting and fighting.

At the end of that time, his crown having accidentally dropped off, Ogier remembered the past, and returned to France, riding on Papillon. He reached the court during the reign of one of the Capetian kings. He was, of course, greatly amazed at the changes which had taken place, but bravely helped to defend Paris against an invasion from the Normans.

[Sidenote: Ogier carried to Avalon.] Shortly after this, his magic ring was playfully drawn from his finger and put upon her own by the Countess of Senlis, who, seeing that it restored her vanished youth, would fain have kept it always. She therefore sent thirty champions to wrest it from Ogier, who, however, defeated them all, and triumphantly retained his ring. The king having died, Ogier next married the widowed queen, and would thus have become King of France had not Morgana the fay, jealous of his affections, spirited him away in the midst of the marriage ceremony and borne him off to the Isle of Avalon, whence he, like Arthur, will return only when his country needs him.

[Sidenote: Roland and Oliver.] Another chanson de geste, a sort of continuation of "Ogier le Danois," is called "Meurvin," and purports to give a faithful account of the adventures of a son of Ogier and Morgana, an ancestor of Godfrey of Bouillon, King of Jerusalem. In "Guerin de Montglave," we find that Charlemagne, having quarreled with the Duke of Genoa, proposed that each should send a champion to fight in his name. Charlemagne selected Roland, while the Duke of Genoa chose Oliver as his defender. The battle, if we are to believe some versions of the legend, took place on an island in the Rhone, and Durandana, Roland's sword, struck many a spark from Altecler (Hautecler), the blade of Oliver. The two champions were so well matched, and the blows were dealt with such equal strength and courage, that "giving a Roland for an Oliver" has become a proverbial expression.

After fighting all day, with intermissions to interchange boasts and taunts, and to indulge in sundry discussions, neither had gained any advantage. They would probably have continued the struggle indefinitely, however, had not an angel of the Lord interfered, and bidden them embrace and become fast friends. It was on this occasion, we are told, that Charlemagne, fearing for Roland when he saw the strength of Oliver, vowed a pilgrimage to Jerusalem should his nephew escape alive.

[Sidenote: Charlemagne's pilgrimage to Jerusalem.] The fulfillment of this vow is described in "Galyen Rhetoré." Charlemagne and his peers reached Jerusalem safely in disguise, but their anxiety to secure relics soon betrayed their identity. The King of Jerusalem, Hugues, entertained them sumptuously, and, hoping to hear many praises of his hospitality, concealed himself in their apartment at night. The eavesdropper, however, only heard the vain talk of Charlemagne's peers, who, unable to sleep, beguiled the hours in making extraordinary boasts. Roland declared that he could blow his horn Olivant loud enough to bring down the palace; Ogier, that he could crumble the principal pillar to dust in his grasp; and Oliver, that he could marry the princess in spite of her father.

The king, angry at hearing no praises of his wealth and hospitality, insisted upon his guests fulfilling their boasts on the morrow, under penalty of death. He was satisfied, however, by the success of Oliver's undertaking, and the peers returned to France. Galyen, Oliver's son by Hugues's daughter, followed them thither when he reached manhood, and joined his father in the valley of Roncesvalles, just in time to receive his blessing ere he died. Then, having helped Charlemagne to avenge his peers, Galyen returned to Jerusalem, where he found his grandfather dead and his mother a captive. His first act was, of course, to free his mother, after which he became king of Jerusalem, and his adventures came to an end.

The "Chronicle" of Turpin, whence the materials for many of the poems about Roland were taken, declares that Charlemagne, having conquered nearly the whole of Europe, retired to his palace to seek repose. But one evening, while gazing at the stars, he saw a bright cluster move from the "Friesian sea, by way of Germany and France, into Galicia." This prodigy, twice repeated, greatly excited Charlemagne's wonder, and was explained to him by St. James in a vision. The latter declared that the progress of the stars was emblematic of the advance of the Christian army towards Spain, and twice bade the emperor deliver his land from the hands of the Saracens.

[Sidenote: Charlemagne in Spain.] Thus admonished, Charlemagne set out for Spain with a large army, and invested the city of Pamplona, which showed no signs of surrender at the end of a two months' siege. Recourse to prayer on the Christians' part, however, produced a great miracle, for the walls tottered and fell like those of Jericho. All the Saracens who embraced Christianity were spared, but the remainder were slain before the emperor journeyed to the shrine of St. James at Santiago de Compostela to pay his devotions.

A triumphant march through the country then ensued, and Charlemagne returned to France, thinking the Saracens subdued. He had scarcely crossed the border, however, when Aigolandus, one of the pagan monarchs, revolted, and soon recovered nearly all the territory his people had lost. When Charlemagne heard these tidings, he sent back an army, commanded by Milon, Roland's father, who perished gloriously in this campaign. The emperor speedily followed his brother-in-law with great forces, and again besieged Aigolandus in Pamplona. During the course of the siege the two rulers had an interview, which is described at length, and indulged in sundry religious discussions, which, however, culminated in a resumption of hostilities. Several combats now took place, in which the various heroes greatly distinguished themselves, the preference being generally given to Roland, who, if we are to believe the Italian poet, was as terrible in battle as he was gentle in time of peace.

"On stubborn foes he vengeance wreak'd,

And laid about him like a Tartar;

But if for mercy once they squeak'd,

He was the first to grant them quarter.

The battle won, of Roland's soul

Each milder virtue took possession;

To vanquished foes he o'er a bowl

His heart surrender'd at discretion."

ARIOSTO, Orlando Furioso (Dr. Burney's tr.).

Aigolandus being slain, and the feud against him thus successfully ended, Charlemagne carried the war into Navarre, where he was challenged by the giant Ferracute (Ferragus) to meet him in single combat. Although the metrical "Romances" describe Charlemagne as twenty feet in height, and declare that he slept in a hall, his bed surrounded by one hundred lighted tapers and one hundred knights with drawn swords, the emperor felt himself no match for the giant, whose personal appearance was as follows:--

"So hard he was to-fond [proved],

That no dint of brond

No grieved him, I plight.

He had twenty men's strength;

And forty feet of length

Thilke [each] paynim had;

And four feet in the face

Y-meten [measured] on the place;

And fifteen in brede [breadth].

His nose was a foot and more;

His brow as bristles wore;

(He that saw it said)

He looked lothliche [loathly],

And was swart [black] as pitch;

Of him men might adrede!"

Roland and Ferragus.

[Sidenote: Roland and Ferracute.] After convincing himself of the danger of meeting this adversary, Charlemagne sent Ogier the Dane to fight him, and with dismay saw his champion not only unhorsed, but borne away like a parcel under the giant's arm, fuming and kicking with impotent rage. Renaud de Montauban met Ferracute on the next day, with the same fate, as did several other champions. Finally Roland took the field, and although the giant pulled him down from his horse, he continued the battle all day. Seeing that his sword Durandana had no effect upon Ferracute, Roland armed himself with a club on the morrow.

In the pauses of the battle the combatants talked together, and Ferracute, relying upon his adversary's keen sense of honor, even laid his head upon Roland's knee during their noonday rest. While resting thus, he revealed that he was vulnerable in only one point of his body. When called upon by Roland to believe in Christianity, he declared that the doctrine of the Trinity was more than he could accept. Roland, in answer, demonstrated that an almond is but one fruit, although composed of rind, shell, and kernel; that a harp is but one instrument, although it consists of wood, strings, and harmony. He also urged the threefold nature of the sun,--i.e., heat, light, and splendor; and these arguments having satisfied Ferracute concerning the Trinity, he removed his doubts concerning the incarnation by equally forcible reasoning. The giant, however, utterly refused to believe in the resurrection, although Roland, in support of his creed, quoted the mediaeval belief that a lion's cubs are born into the world dead, but come to life on the third day at the sound of their father's roar, or under the warm breath of their mother. As Ferracute would not accept this doctrine, but sprang to his feet proposing a continuation of the fight, the struggle was renewed.

"Quath Ferragus: 'Now ich wot

Your Christian law every grot;

Now we will fight;

Whether law better be,

Soon we shall y-see,

Long ere it be night.'"

Roland and Ferragus.

Roland, weary with his previous efforts, almost succumbed beneath the giant's blows, and in his distress had recourse to prayer. He was immediately strengthened and comforted by an angelic vision and a promise of victory. Thus encouraged, he dealt Ferracute a deadly blow in the vulnerable spot. The giant fell, calling upon Mohammed, while Roland laughed and the Christians triumphed.

The poem of Sir Otuel, in the Auchinleck manuscript, describes how Otuel, a nephew of Ferracute, his equal in size and strength, came to avenge his death, and, after a long battle with Roland, yielded to his theological arguments, and was converted at the sight of a snowy dove alighting on Charlemagne's helmet in answer to prayer. He then became a devoted adherent of Charlemagne, and served him much in war.

Charlemagne, having won Navarre, carried the war to the south of Spain, where the Saracens frightened the horses of his host by beating drums and waving banners. Having suffered a partial defeat on account of this device, Charlemagne had the horses' ears stopped with wax, and their eyes blindfolded, before he resumed the battle. Thanks to this precaution, he succeeded in conquering the Saracen army. The whole country had now been again subdued, and Charlemagne was preparing to return to France, when he remembered that Marsiglio (Marsilius), a Saracen king, was still intrenched at Saragossa.

"Carle, our most noble Emperor and King,

Hath tarried now full seven years in Spain,

Conqu'ring the highland regions to the sea;

No fortress stands before him unsubdued,

Nor wall, nor city left, to be destroyed,

Save Sarraguce, high on a mountain set.

There rules the King Marsile, who loves not God,

Apollo worships, and Mohammed serves;

Nor can he from his evil doom escape."

Chanson de Roland (Rabillon's tr.).

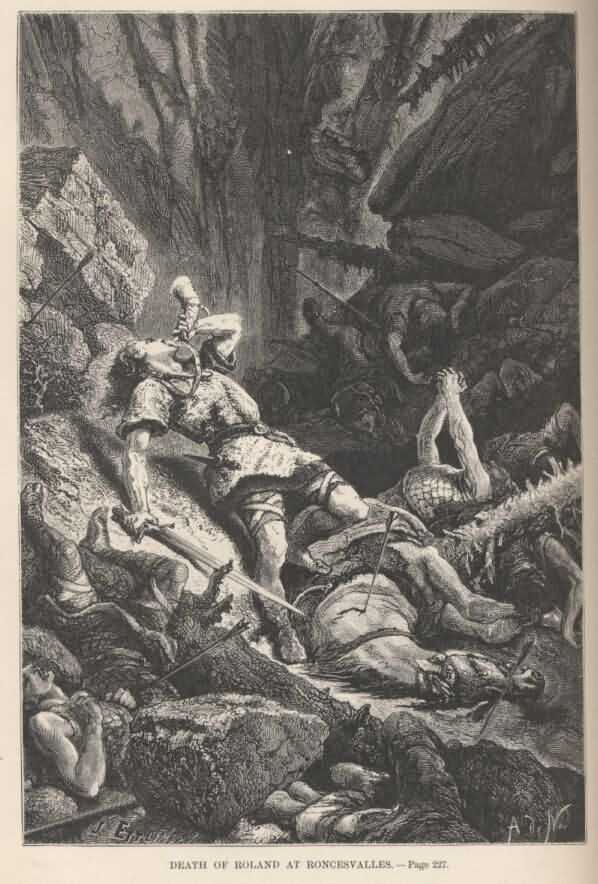

[Sidenote: Battle of Roncesvalles.] The emperor wished to send an embassy to him to arrange the terms of peace, but discarded Roland's offer of service because of his impetuosity. Then, following the advice of Naismes de Bavière, "the Nestor of the Carolingian legends," he selected Ganelon, Roland's stepfather, as ambassador. This man was a traitor, and accepted a bribe from the Saracen king to betray Roland and the rear guard of the French army into his power. Advised by Ganelon, Charlemagne departed from Spain at the head of his army, leaving Roland to bring up the rear. The main part of the army passed through the Pyrenees unmolested, but the rear guard of twenty thousand men, under Roland, was attacked by a superior force of Saracens in ambush, as it was passing through the denies of Roncesvalles. A terrible encounter took place here.

"The Count Rollànd rides through the battlefield

And makes, with Durendal's keen blade in hand,

A mighty carnage of the Saracens.

Ah! had you then beheld the valiant Knight

Heap corse on corse; blood drenching all the ground;

His own arms, hauberk, all besmeared with gore,

And his good steed from neck to shoulder bleed!"

Chanson de Roland (Rabillon's tr.).

THE DEATH OF ROLAND.--Keller.

All the Christians were slain except Roland and a few knights, who succeeded in repulsing the first onslaught of the painims. Roland then bound a Saracen captive to a tree, wrung from him a confession of the dastardly plot, and, discovering where Marsiglio was to be found, rushed into the very midst of the Saracen army and slew him. The Saracens, terrified at the apparition of the hero, beat a hasty retreat, little suspecting that their foe had received a mortal wound, and would shortly breathe his last.

During the first part of the battle, Roland, yielding to Oliver's entreaty, sounded a blast on his horn Olivant, which came even to Charlemagne's ear. Fearing lest his nephew was calling for aid, Charlemagne would fain have gone back had he not been deterred by Ganelon, who assured him that Roland was merely pursuing a stag.

"Rolland raised to his lips the olifant,

Drew a deep breath, and blew with all his force.

High are the mountains, and from peak to peak

The sound reëchoes; thirty leagues away

'Twas heard by Carle and all his brave compeers.

Cried the king: 'Our men make battle!' Ganelon

Retorts in haste: 'If thus another dared

To speak, we should denounce it as a lie.'

Aoi"

Chanson de Roland (Rabillon's tr.).

[Sidenote: Steed Veillantif slain.] Wounded and faint, Roland now slowly dragged himself to the entrance of the pass of Cisaire,--where the Basque peasants aver they have often seen his ghost, and heard the sound of his horn,--and took leave of his faithful steed Veillantif, which he slew with his own hand, to prevent its falling into the hands of the enemy.

"'Ah, nevermore, and nevermore, shall we to battle ride!

Ah, nevermore, and nevermore, shall we sweet comrades be!

And Veillintif, had I the heart to die forgetting thee?

To leave thy mighty heart to break, in slavery to the foe?

I had not rested in the grave, if it had ended so.

Ah, never shall we conquering ride, with banners bright

unfurl'd,

A shining light 'mong lesser lights, a wonder to the

world.'"

BUCHANAN, Death of Roland.

[Sidenote: Sword Durandana destroyed.] Then the hero gazed upon his sword Durandana, which had served him faithfully for so many years, and to prevent its falling into the hands of the pagans, he tried to dispose of it also. According to varying accounts, he either sank it deep into a poisoned stream, where it is still supposed to lie, or, striking it against the mighty rocks, cleft them in two, without even dinting its bright blade.

"And Roland thought: 'I surely die; but, ere I end,

Let me be sure that thou art ended too, my friend!

For should a heathen hand grasp thee when I am clay,

My ghost would grieve full sore until the judgment day!'

Then to the marble steps, under the tall, bare trees,

Trailing the mighty sword, he crawl'd on hands and knees,

And on the slimy stone he struck the blade with might--

The bright hilt, sounding, shook, the blade flash'd sparks of

light;

Wildly again he struck, and his sick head went round,

Again there sparkled fire, again rang hollow sound;

Ten times he struck, and threw strange echoes down the

glade,

Yet still unbroken, sparkling fire, glitter'd the peerless

blade."

BUCHANAN, Death of Roland.

Finally, despairing of disposing of it in any other way, the hero, strong in death, broke Durandana in his powerful hands and threw the shards away.

Horse and sword were now disposed of, and the dying hero, summoning his last strength, again put his marvelous horn Olivant to his lips, and blew such a resounding blast that the sound was heard far and near. The effort, however, was such that his temples burst, as he again sank fainting to the ground.

One version of the story (Turpin's) relates that the blast brought, not Charlemagne, but the sole surviving knight, Theodoricus, who, as Roland had been shriven before the battle, merely heard his last prayer and reverently closed his eyes. Then Turpin, while celebrating mass before Charlemagne, was suddenly favored by a vision, in which he beheld a shrieking crew of demons bearing Marsiglio's soul to hell, while an angelic host conveyed Roland's to heaven.

Turpin immediately imparted these revelations to Charlemagne, who, knowing now that his fears were not without foundation, hastened back to Roncesvalles. Here the scriptural miracle was repeated, for the sun stayed its course until the emperor had routed the Saracens and found the body of his nephew. He pronounced a learned funeral discourse or lament over the hero's remains, which were then embalmed and conveyed to Blaive for interment.

Another version relates that Bishop Turpin himself remained with Roland in the rear, and, after hearing a general confession and granting full absolution to all the heroes, fought beside them to the end. It was he who heard the last blast of Roland's horn instead of Theodoricus, and came to close his eyes before he too expired.

The most celebrated of all the poems, however, the French epic "Chanson de Roland," gives a different version and relates that, in stumbling over the battlefield, Roland came across the body of his friend Oliver, over which he uttered a touching lament.

"'Alas for all thy valor, comrade dear!

Year after year, day after day, a life

Of love we led; ne'er didst thou wrong to me,

Nor I to thee. If death takes thee away,

My life is but a pain.'"

Chanson de Roland (Rabillon's tr.).

[Sidenote: Death of Roland.] Slowly and painfully now--for his death was near--Roland climbed up a slope, laid himself down under a pine tree, and placed his sword and horn beneath him. Then, when he had breathed a last prayer, to commit his soul to God, he held up his glove in token of his surrender.

"His right hand glove he offered up to God;

Saint Gabriel took the glove.--With head reclined

Upon his arm, with hands devoutly joined,

He breathed his last. God sent his Cherubim,

Saint Raphael, Saint Michiel del Peril.

The soul of Count Rolland to Paradise.

Aoi."

Chanson de Roland (Rabillon's tr.).

It was here, under the pine, that Charlemagne found his nephew ere he started out to punish the Saracens, as already related. Not far off lay the bodies of Ogier, Oliver, and Renaud, who, according to this version, were all among the slain.

"Here endeth Otuel, Roland, and Olyvere,

And of the twelve dussypere,

That dieden in the batayle of Runcyvale:

Jesu lord, heaven king,

To his bliss hem and us both bring,

To liven withouten bale!"

Sir Otuel.

On his return to France Charlemagne suspected Ganelon of treachery, and had him tried by twelve peers, who, unable to decide the question, bade him prove his innocence in single combat with Roland's squire, Thiedric. Ganelon, taking advantage of the usual privilege to have his cause defended by a champion, selected Pinabel, the most famous swordsman of the time. In spite of all his valor, however, this champion was defeated, and the "judgment of God"--the term generally applied to those judicial combats--was in favor of Thiedric. Ganelon, thus convicted of treason, was sentenced to be drawn and quartered, and was executed at Aix-la-Chapelle, in punishment for his sins.

"Ere long for this he lost

Both limb and life, judged and condemned at Aix,

There to be hanged with thirty of his race

Who were not spared the punishment of death.

Aoi."

Chanson de Roland (Rabillon's tr.).

[Sidenote: Roland and Aude.] Roland, having seen Aude, Oliver's sister, at the siege of Viane, where she even fought against him, if the old epics are to be believed, had been so smitten with her charms that he declared that he would marry none but her. When the siege was over, and lifelong friendship had been sworn between Roland and Oliver after their memorable duel on an island in the Rhone, Roland was publicly betrothed to the charming Aude. Before their nuptials could take place, however, he was forced to leave for Spain, where, as we have seen, he died an heroic death. The sad news of his demise was brought to Paris, where the Lady Aude was awaiting him. When she heard that he would never return, she died of grief, and was buried at his side in the chapel of Blaive.

"In Paris Lady Alda sits, Sir Roland's destined bride.

With her three hundred maidens, to tend her, at her side;

Alike their robes and sandals all, and the braid that binds their

hair,

And alike the meal, in their Lady's hall, the whole three hundred

share.

Around her, in her chair of state, they all their places

hold;

A hundred weave the web of silk, and a hundred spin the

gold,

And a hundred touch their gentle lutes to sooth that Lady's

pain,

As she thinks on him that's far away with the host of

Charlemagne.

Lulled by the sound, she sleeps, but soon she wakens with a

scream;

And, as her maidens gather round, she thus recounts her

dream:

'I sat upon a desert shore, and from the mountain nigh,

Right toward me, I seemed to see a gentle falcon fly;

But close behind an eagle swooped, and struck that falcon

down,

And with talons and beak he rent the bird, as he cowered beneath

my gown.'

The chief of her maidens smiled, and said; 'To me it doth not

seem

That the Lady Alda reads aright the boding of her dream.

Thou art the falcon, and thy knight is the eagle in his

pride,

As he comes in triumph from the war, and pounces on his

bride.'

The maiden laughed, but Alda sighed, and gravely shook her

head.

'Full rich,' quoth she, 'shall thy guerdon be, if thou the truth

hast said.'

'Tis morn; her letters, stained with blood, the truth too plainly

tell,

How, in the chase of Ronceval, Sir Roland fought and fell."

Lady Alda's Dreams (Sir Edmund Head's tr.).

[Sidenote: Legend of Roland and Hildegarde.] A later legend, which has given rise to sundry poems, connects the name of Roland with one of the most beautiful places on the Rhine. Popular tradition avers that he sought shelter one evening in the castle of Drachenfels, where he fell in love with Hildegarde, the beautiful daughter of the Lord of Drachenfels. The sudden outbreak of the war in Spain forced him to bid farewell to his betrothed, but he promised to return as soon as possible to celebrate their wedding. During the campaign, many stories of his courage came to Hildegarde's ears, and finally, after a long silence, she heard that Roland had perished at Roncesvalles.

Broken-hearted, the fair young mourner spent her days in tears, and at last prevailed upon her father to allow her to enter the convent on the island of Nonnenworth, in the middle of the river, and within view of the gigantic crag where the castle ruins can still be seen.

"The castled crag of Drachenfels

Frowns o'er the wide and winding Rhine,

Whose breast of water broadly swells

Between the banks which bear the vine,

And hills all rich with blossomed trees,

And fields which promise corn and wine,

And scattered cities crowning these,

Whose fair white walls along them shine."

BYRON, Childe Harold.

With pallid cheeks and tear-dimmed eyes, Hildegarde now spent her life either in her tiny cell or in the convent chapel, praying for the soul of her beloved, and longing that death might soon come to set her free to join him. The legend relates, however, that Roland was not dead, as she supposed, but had merely been sorely wounded at Roncesvalles.

When sufficiently recovered to travel, Roland painfully made his way back to Drachenfels, where he presented himself late one evening, eagerly calling for Hildegarde. A few moments later the joyful light left his eyes forever, for he learned that his beloved had taken irrevocable vows, and was now the bride of Heaven.

That selfsame day Roland left the castle of Drachenfels, and riding to an eminence overlooking the island of Nonnenwörth, he gazed long and tearfully at a little light twinkling in one of the convent windows. As he could not but suppose that it illumined Hildegarde's cell and lonely vigils, he watched it all night, and when morning came he recognized his beloved's form in the long procession of nuns on their way to the chapel.

[Sidenote: Rolandseck.] This view of the lady he loved seemed a slight consolation to the hero, who built a retreat on this rock, which is known as Rolandseck. Here he spent his days in penance and prayer, gazing constantly at the island at his feet, and the swift stream which parted him from Hildegarde.

One wintry day, many years after he had taken up his abode on the rocky height, Roland missed the graceful form he loved, and heard, instead of the usual psalm, a dirge for the dead. Then he noticed that six of the nuns were carrying a coffin, which they lowered into an open tomb.

Roland's nameless fears were confirmed in the evening, when the convent priest visited him, and gently announced that Hildegarde was at rest. Calmly Roland listened to these tidings, begged the priest to hear his confession as usual, and, when he had received absolution, expressed a desire to be buried with his face turned toward the convent where Hildegarde had lived and died.

The priest readily promised to observe this request, and departed. When he came on the morrow, he found Roland dead. They buried him reverently on the very spot which bears his name, with his face turned toward Nonnenwörth, where Hildegarde lay at rest.