THE AMBITIOUS FOX AND THE UNAPPROACHABLE GRAPES

A farmer built around his crop

A wall, and crowned his labors

By placing glass upon the top

To lacerate his neighbors,

Provided they at any time

Should feel disposed the wall to climb.

He also drove some iron pegs

Securely in the coping,

To tear the bare, defenceless legs

Of brats who, upward groping,

Might steal, despite the risk of fall,

The grapes that grew upon the wall.

One day a fox, on thieving bent,

A crafty and an old one,

Most shrewdly tracked the pungent scent

That eloquently told one

That grapes were ripe and grapes were good

And likewise in the neighborhood.

He threw some stones of divers shapes

The luscious fruit to jar off:

It made him ill to see the grapes

So near and yet so far off.

His throws were strong, his aim was fine,

But "Never touched me!" said the vine.

The farmer shouted, "Drat the boys!"

And, mounting on a ladder,

He sought the cause of all the noise;

No farmer could be madder,

Which was not hard to understand

Because the glass had cut his hand.

His passion he could not restrain,

But shouted out, "You're thievish!"

The fox replied, with fine disdain,

"Come, country, don't be peevish."

(Now "country" is an epithet

One can't forgive, nor yet forget.)

The farmer rudely answered back

With compliments unvarnished,

And downward hurled the bric-à-brac

With which the wall was garnished,

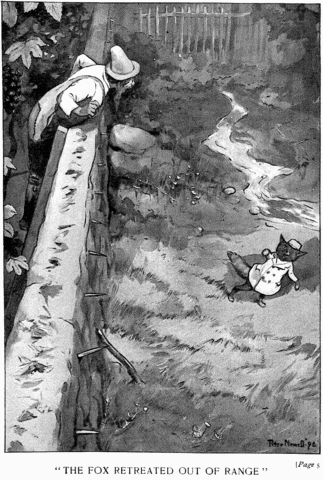

In view of which demeanor strange,

The fox retreated out of range.

"I will not try the grapes to-day,"

He said. "My appetite is

Fastidious, and, anyway,

I fear appendicitis."

(The fox was one of the élite

Who call it site instead

of seet.)

The moral is that if your host

Throws glass around his entry

You know it isn't done by most

Who claim to be the gentry,

While if he hits you in the head

You may be sure he's underbred.

THE PERSEVERING TORTOISE AND THE PRETENTIOUS HARE

Once a turtle, finding plenty

In seclusion to bewitch,

Lived a dolce far

niente

Kind of life within a ditch;

Rivers had no charm for him,

As he told his wife and daughter,

"Though my friends are in the swim,

Mud is thicker far than water."

One fine day, as was his habit,

He was dozing in the sun,

When a young and flippant rabbit

Happened by the ditch to run:

"Come and race me," he exclaimed,

"Fat inhabitant of puddles.

Sluggard! You should be ashamed.

Such a life the brain befuddles."

This, of course, was banter merely,

But it stirred the torpid blood

Of the turtle, and severely

Forth he issued from the mud.

"Done!" he cried. The race began,

But the hare resumed his banter,

Seeing how his rival ran

In a most unlovely canter.

Shouting, "Terrapin, you're bested!

You'd be wiser, dear old chap,

If you sat you down and rested

When you reach the second lap."

Quoth the turtle, "I refuse.

As for you, with all your talking,

Sit on any lap you choose.

I shall simply go on

walking."

Now this sporting proposition

Was, upon its face, absurd;

Yet the hare, with expedition,

Took the tortoise at his word,

Ran until the final lap,

Then, supposing he'd outclassed him,

Laid him down and took a nap

And the patient turtle passed him!

Plodding on, he shortly made the

Line that marked the victor's goal;

Paused, and found he'd won, and laid the

Flattering unction to his soul.

Then in fashion grandiose,

Like an after-dinner speaker,

Touched his flipper to his nose,

And remarked, "Ahem! Eureka!"

And THE MORAL (lest you miss one)

Is: There's often time to spare,

And that races are (like this one)

Won not always by a hair.

THE PATRICIAN PEACOCKS AND THE OVERWEENING JAY

Once a flock of stately peacocks

Promenaded on a green,

There were twenty-two or three cocks,

Each as proud as seventeen,

And a glance, however hasty,

Showed their plumage to be tasty;

Wheresoever one was placed, he

Was a credit to the scene.

Now their owner had a daughter

Who, when people came to call,

Used to say, "You'd reelly oughter

See them peacocks on the mall."

Now this wasn't to her credit,

And her callers came to dread it,

For the way the lady said it

Wasn'trecherché

at all.

But a jay that overheard it

From his perch upon a fir

Didn't take in how absurd it

Was to every one but her;

When they answered, "You don't tell us!"

And to see the birds seemed zealous

He became extremely jealous,

Wishing, too, to make a stir.

As the peacocks fed together

He would join them at their lunch,

Culling here and there a feather

Till he'd gathered quite a bunch;

Then this bird, of ways perfidious,

Stuck them on him most fastidious

Till he looked uncommon hideous,

Like a Judy or a Punch.

But the peacocks, when they saw him,

One and all began to haul,

And to harry and to claw him

Till the creature couldn't crawl;

While their owner's vulgar daughter,

When her startled callers sought her,

And to see the struggle brought her,

Only said, "They're on the maul."

It was really quite revolting

When the tumult died away,

One would think he had been moulting

So dishevelled was the jay;

He was more than merely slighted,

He was more than disunited,

He'd been simply dynamited

In the fervor of the fray.

And THE MORAL of the verses

Is: That short men can't be tall.

Nothing sillier or worse is

Than a jay upon a mall.

And the jay opiniative

Who, because he's imitative,

Thinks he's highly decorative

Is the biggest jay of all.

THE ARROGANT FROG AND THE SUPERIOR BULL

Once, on a time and in a place

Conducive to malaria,

There lived a member of the race

Of Rana Temporaria;

Or, more concisely still, a frog

Inhabited a certain bog.

A bull of Brobdingnagian size,

Too proud for condescension,

One morning chanced to cast his eyes

Upon the frog I mention;

And, being to the manner born,

Surveyed him with a lofty scorn.

Perceiving this, the bactrian's frame

With anger was inflated,

Till, growing larger, he became

Egregiously elated;

For inspiration's sudden spell

Had pointed out a way to swell.

"Ha! ha!" he proudly cried, "a fig

For this, your mammoth torso!

Just watch me while I grow as big

As you--or even more so!"

To which magniloquential gush

His bullship simply answered "Tush!"

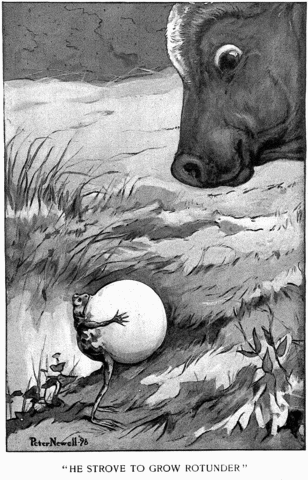

Alas! the frog's success was slight,

Which really was a wonder,

In view of how with main and might

He strove to grow rotunder!

And, standing patiently the while,

The bull displayed a quiet smile.

But ah, the frog tried once too oft

And, doing so, he busted;

Whereat the bull discreetly coughed

And moved away, disgusted,

As well he might, considering

The wretched taste that marked the thing.

THE MORAL: Everybody knows

How ill a wind it is that blows.

THE DOMINEERING EAGLE AND THE INVENTIVE BRATLING

O'er a small suburban borough

Once an eagle used to fly,

Making observations thorough

From his station in the sky,

And presenting the appearance

Of an animated V,

Like the gulls that lend coherence

Unto paintings of the sea.

Looking downward at a church in

This attractive little shire,

He beheld a smallish urchin

Shooting arrows at the spire;

In a spirit of derision,

"Look alive!" the eagle said;

And, with infinite precision,

Dropped a feather on his head.

Then the boy, annoyed distinctly

By the freedom of the bird,

Voiced his anger quite succinctly

In a single scathing word;

And he sat him on a barrow,

And he fashioned of this same

Eagle's feather such an arrow

As was worthy of the name.

Then he tried his bow, and, stringing

It with caution and with care,

Sent that arrow singing, winging

Towards the eagle in the air.

Straight it went, without an error,

And the target, bathed in blood,

Lurched, and lunged, and fell to terra Firma,

landing with a thud.

"Bird of freedom," quoth the urchin,

With an unrelenting frown,

"You shall decorate a perch in

The menagerie in town;

But of feathers quite a cluster

I shall first remove for Ma:

Thanks to you, she'll have a duster

For her precious objets

d'art."

And THE MORAL is that pride is

The precursor of a fall.

Those beneath you to deride is

Not expedient at all.

Howsoever meek and humble

Your inferiors may be,

They perchance may make you tumble,

So respect them. Q. E. D.

THE ICONOCLASTIC RUSTIC AND THE APROPOS ACORN

Reposing 'neath some spreading trees,

A populistic bumpkin

Amused himself by offering these

Reflections on a pumpkin:

"I would not, if the choice were mine,

Grow things like that upon a vine,

For how imposing it would be

If pumpkins grew upon a tree."

Like other populists, you'll note,

Of views enthusiastic,

He'd learned by heart, and said by rote

A creed iconoclastic;

And in his dim, uncertain sight

Whatever wasn't must be right,

From which it follows he had strong

Convictions that what was, was wrong.

As thus he sat beneath an oak

An acorn fell abruptly

And smote his nose: whereat he spoke

Of acorns most corruptly.

"Great Scott!" he cried. "The Dickens!" too,

And other authors whom he knew,

And having duly mentioned those,

He expeditiously arose.

Then, though with pain he nearly swooned,

He bathed his organ nasal

With arnica, and soothed the wound

With extract of witch hazel;

And surely we may well excuse

The victim if he changed his views:

"If pumpkins fell from trees like that,"

He murmured, "Where would I be at?"

Of course it's wholly clear to you

That when these words he uttered

He proved conclusively he knew

Which side his bread was buttered;

And, if this point you have not missed,

You'll learn to love this populist,

The only one of all his kind

With sense enough to change his mind.

THE MORAL: In the early spring

A pumpkin-tree would be a thing

Most gratifying to us all,

But how about the early fall?

THE UNUSUAL GOOSE AND THE IMBECILIC WOODCUTTER

A woodcutter bought him a gander,

Or at least that was what he supposed,

As a matter of fact, 'twas a slander

As a later occurrence disclosed;

For they locked the bird up in the garret

To fatten, the while it grew old,

And it laid there a twenty-two carat

Fine egg of the purest of gold!

There was much unaffected rejoicing

In the home of the woodcutter then,

And his wife, her exuberance voicing,

Proclaimed him most lucky of men.

"'Tis an omen of fortune, this gold egg,"

She said, "and of practical use,

For this fowl doesn't lay any old egg,

She's a highly superior goose."

Twas this creature's habitual custom,

This laying of superfine eggs,

And they made it their practice to dust 'em

And pack them by dozens in kegs:

But the woodcutter's mind being vapid

And his foolishness more than profuse,

In order to get them more rapid

He slaughtered the innocent goose.

He made her a gruel of acid

Which she very obligingly ate,

And at once with a touchingly placid

Demeanor succumbed to her fate.

With affection that passed the platonic

They buried her under the moss,

And her epitaph wasn't ironic

In stating, "We mourn for our loss."

And THE MORAL: It isn't much use,

As the woodcutter found to be true,

To lay for an innocent goose

Just because she is laying for you.

THE RUDE RAT AND THE UNOSTENTATIOUS OYSTER

Upon the shore, a mile or more

From traffic and confusion,

An oyster dwelt, because he felt

A longing for seclusion;

Said he: "I love the stillness of

This spot. It's like a cloister."

(These words I quote because, you note,

They rhyme so well with oyster.)

A prying rat, believing that

She needed change of diet,

In search of such disturbed this much-

To-be-desired quiet.

To say the least, this tactless beast

Was apt to rudely roister:

She tapped his shell, and called him--well,

A name that hurt the oyster.

"I see," she cried, "you're open wide,

And, searching for a reason,

September's here, and so it's clear

That oysters are in season."

She smiled a smile that showed this style

Of badinage rejoiced her,

Advanced a pace with easy grace,

And sniffed the silent oyster.

The latter's pride was sorely tried,

He thought of what he could say,

Reflected what the common lot

Of vulgar molluscs would

say;

Then caught his breath, grew pale as death,

And, as his brow turned moister,

Began to close, and nipped her nose!

Superb, dramatic oyster!

We note with joy that oi polloi,

Whom maidens bite the thumb at,

Are apt to try some weak reply

To things they should be dumb at.

THE MORAL, then, for crafty men

Is: When a maid has voiced her

Contemptuous heart, don't think you're smart,

But shut up--like the oyster.

THE URBAN RAT AND THE SUBURBAN RAT

A metropolitan rat invited

His country cousin in town to dine:

The country cousin replied, "Delighted."

And signed himself, "Sincerely thine."

The town rat treated the country cousin

To half a dozen

Kinds of wine.

He served him terrapin, kidneys devilled,

And roasted partridge, and candied fruit;

In Little Neck Clams at first they revelled,

And then in Pommery, sec

and brut;

The country cousin exclaimed: "Such feeding

Proclaims your breeding

Beyond dispute!"

But just as, another bottle broaching,

They came to chicken en

casserole

A ravenous cat was heard approaching,

And, passing his guest a finger-bowl,

The town rat murmured, "The feast is ended."

And then descended

The nearest hole.

His cousin followed him, helter-skelter,

And, pausing beneath the pantry floor,

He glanced around at their dusty shelter

And muttered, "This is a beastly bore.

My place as an epicure resigning,

I'll try this dining

In town no more.

"You must dine some night at my rustic cottage;

I'll warn you now that it's simple fare:

A radish or two, a bowl of pottage,

And the wine that's known as ordinaire,

But for holes I haven't to make a bee-line,

No prowling feline

Molests me there.

"You smile at the lot of a mere commuter,

You think that my life is hard, mayhap,

But I'm sure than you I am far acuter:

I ain't afraid of no cat nor trap."

The city rat could but meekly stammer,

"Don't use such grammar,

My worthy chap."

He dined next night with his poor relation,

And caught dyspepsia, and lost his train,

He waited an hour in the lonely station,

And said some things that were quite profane.

"I'll never," he cried, in tones complaining,

"Try entertaining

That rat again."

It's easy to make a memorandum

About THE MORAL these verses teach:

De gustibus non est

dispuiandum;

The meaning of which Etruscan speech

Is wheresoever you're hunger quelling

Pray keep your dwelling

In easy reach.

THE IMPECUNIOUS CRICKET AND THE FRUGAL ANT

There was an ant, a spinster ant,

Whose virtues were so many

That she became intolerant

Of those who hadn't any:

She had a small and frugal mind

And lived a life ascetic,

Nor was her temperament the kind

That's known as sympathetic.

I skip details. Suffice to say

That, knocking at her wicket,

There chanced to come one autumn day

A common garden cricket

So ragged, poor, and needy that,

Without elucidation,

One saw the symptoms of a bat

Of several months' duration.

He paused beside her door-step, and,

With one pathetic gesture,

He called attention with his hand

To both his shoes and vesture.

"I joined," said he, "an opera troupe.

They suddenly disbanded,

And left me on the hostel stoop,

Lugubriously stranded.

"I therefore lay aside my pride

And frankly ask for clothing."

"Begone!" the frugal ant replied.

"I look on you with loathing.

Your muddy shoes have spoiled the lawn,

Your hands have soiled the fence, too.

If you need money, go and pawn

Your watch--if you have sense to."

THE MORAL is: Albeit lots

Of people follow Dr. Watts,

The sluggard, when his means are scant,

Should seek an uncle, not an ant!

THE PAMPERED LAPDOG AND THE MISGUIDED ASS

A woolly little terrier pup

Gave vent to yelps distressing,

Whereat his mistress took him up

And soothed him with caressing,

And yet he was not in the least

What one would call a handsome beast.

He might have been a Javanese,

He might have been a Jap dog,

And also neither one of these,

But just a common lapdog,

The kind that people send, you know,

Done up in cotton, to the Show.

At all events, whate'er his race,

The pretty girl who owned him

Caressed his unattractive face

And petted and cologned him,

While, watching her with mournful eye,

A patient ass stood silent by.

"If thus," he mused, "the feminine

And fascinating gender

Is led to love, I, too, can win

Her protestations tender."

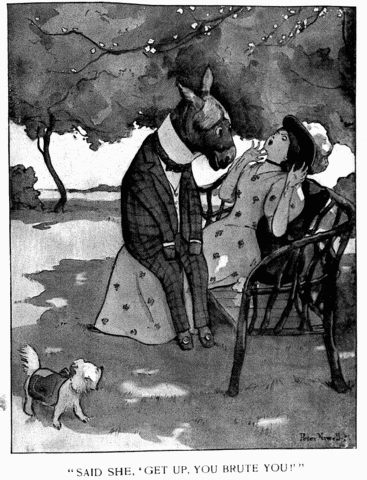

And then the poor, misguided chap

Sat down upon the lady's lap.

Then, as her head with terror swam,

"This method seems to suit you,"

Observed the ass, "so here I am."

Said she, "Get up, you brute you!"

And promptly screamed aloud for aid:

No ass was ever more dismayed.

They took the ass into the yard

And there, with whip and truncheon,

They beat him, and they beat him hard,

From breakfast-time till luncheon.

He only gave a tearful gulp,

Though almost pounded to a pulp.

THE MORAL is (or seems, at least,

To be): In etiquette you

Will find that while enough's a feast

A surplus will upset you.

Toujours, toujours la

politesse, if

The quantity be not excessive.

THE VAINGLORIOUS OAK AND THE MODEST BULRUSH

A bulrush stood on a river's rim,

And an oak that grew near by

Looked down with cold hauteur on him,

And addressed him this way: "Hi!"

The rush was a proud patrician, and

He retorted, "Don't you know,

What the veriest boor should understand,

That 'Hi' is low?"

This cutting rebuke the oak ignored.

He returned, "My slender friend,

I will frankly state that I'm somewhat bored

With the way you bow and bend."

"But you quite forget," the rush replied,

"It's an art these bows to do,

An art I wouldn't attempt if I'd

Such boughs as you."

"Of course," said the oak, "in my sapling days

My habit it was to bow,

But the wildest storm that the winds could raise

Would never disturb me now.

I challenge the breeze to make me bend,

And the blast to make me sway."

The shrewd little bulrush answered, "Friend,

Don't get so gay."

And the words had barely left his mouth

When he saw the oak turn pale,

For, racing along south-east-by-south,

Came ripping a raging gale.

And the rush bent low as the storm went past,

But stiffly stood the oak,

Though not for long, for he found the blast

No idle joke.

* * * * * * * *

Imagine the lightning's gleaming bars,

Imagine the thunder's roar,

For that is exactly what eight stars

Are set in a row here for!

The oak lay prone when the storm was done,

While the rush, still quite erect,

Remarked aside, "What under the sun

Could one expect?"

And THE MORAL, I'd have you understand,

Would have made La Fontaine blush,

For it's this: Some storms come early, and

Avoid the rush!

THE INHUMAN WOLF AND THE LAMB SANS GENE

A gaunt and relentless wolf, possessed

Of a quite insatiable thirst,

Once paused at a stream to drink and rest,

And found that, bound on a similar quest,

A lamb had arrived there first.

The lamb was a lamb of a garrulous mind

And frivolity most extreme:

In the fashion common to all his kind,

He cantered in front and galloped behind.

And troubled the limpid stream.

"My friend," said the wolf, with a winsome air,

"Your capers I can't admire."

"Go to!" quoth the lamb. (Though he said not where,

He showed what he meant by his brazen stare

And the way that he gambolled higher.)

"My capers," he cried, "are the kind that are

Invariably served with lamb.

Remember, this is a public bar,

And I'll do as I please. If your drink I mar,

I don't give a tinker's ----."

He paused and glanced at the rivulet,

And that pause than speech was worse,

For his roving eye a saw-mill met,

And, near it, the word which should be set

At the end of the previous verse.

Said the wolf: "You are tough and may bring remorse,

But of such is the world well rid.

I've swallowed your capers, I've swallowed your sauce,

And it's plain to be seen that my only course

Is swallowing you." He did.

THE MORAL: The wisest lambs they are

Who, when they're assailed by thirst,

Keep well away from a public bar;

For of all black sheep, or near, or far,

The public bar-lamb's worst!

THE SYCOPHANTIC FOX AND THE GULLIBLE RAVEN

A raven sat upon a tree,

And not a word he spoke, for

His beak contained a piece of Brie,

Or, maybe, it was Roquefort:

We'll make it any kind you please--

At all events, it was a cheese.

Beneath the tree's umbrageous limb

A hungry fox sat smiling;

He saw the raven watching him,

And spoke in words beguiling.

"J'admire," said he,

"ton beau plumage."

(The which was simply persiflage.)

Two things there are, no doubt you know,

To which a fox is used:

A rooster that is bound to crow,

A crow that's bound to roost,

And whichsoever he espies

He tells the most unblushing lies.

"Sweet fowl," he said, "I understand

You're more than merely natty,

I hear you sing to beat the band

And Adelina Patti.

Pray render with your liquid tongue

A bit from 'Gotterdammerung.'"

This subtle speech was aimed to please

The crow, and it succeeded:

He thought no bird in all the trees

Could sing as well as he did.

In flattery completely doused,

He gave the "Jewel Song" from "Faust."

But gravitation's law, of course,

As Isaac Newton showed it,

Exerted on the cheese its force,

And elsewhere soon bestowed it.

In fact, there is no need to tell

What happened when to earth it fell.

I blush to add that when the bird

Took in the situation

He said one brief, emphatic word,

Unfit for publication.

The fox was greatly startled, but

He only sighed and answered "Tut."

THE MORAL is: A fox is bound

To be a shameless sinner.

And also: When the cheese comes round

You know it's after dinner.

But (what is only known to few)

The fox is after dinner, too.

THE MICROSCOPIC TROUT AND THE MACHIAVELIAN FISHERMAN

A fisher was casting his flies in a brook,

According to laws of such sciences,

With a patented reel and a patented hook

And a number of other appliances;

And the thirty-fifth cast, which he vowed was the last

(It was figured as close as a decimal),

Brought suddenly out of the water a trout

Of measurements infinitesimal.

This fish had a way that would win him a place

In the best and most polished society,

And he looked at the fisherman full in the face

With a visible air of anxiety:

He murmered "Alas!" from his place in the grass,

And then, when he'd twisted and wriggled, he

Remarked in a pet that his heart was upset

And digestion all higgledy-piggledy.

"I request," he observed, "to be instantly flung

Once again in the pool I've been living in."

The fisherman said, "You will tire out your tongue.

Do you see any signs of my giving in?

Put you back in the pool? Why, you fatuous fool,

I have eaten much smaller and thinner fish.

You're not salmon or sole, but I think, on the whole,

You're a fairly respectable dinner-fish."

The fisherman's cook tried her hand on the trout

And with various herbs she embellished him;

He was lovely to see, and there isn't a doubt

That the fisherman's family relished him,

And, to prove that they did, both his wife and his kid

Devoured the trout with much eagerness,

Avowing no dish could compare with that fish,

Notwithstanding his singular meagreness.

And THE MORAL, you'll find, is although it is kind

To grant favors that people are wishing for,

Still a dinner you'll lack if you chance to throw back

In the pool little trout that you're fishing for;

If their pleading you spurn you will certainly learn

That herbs will deliciously vary 'em:

It is needless to state that a trout on a plate

Beats several in the aquarium.

THE CONFIDING PEASANT AND THE MALADROIT BEAR

A bear of manners pleasant,

And all the love she had to spare

She lavished on the peasant:

She proved her deep affection plainly

(The method was a bit ungainly).

The peasant had to dig and delve,

And, as his class are apt to,

When all the whistles blew at twelve

He ate his lunch, and napped, too,

The bear a careful outlook keeping

The while her master lay a-sleeping.

As thus the peasant slept one day,

The weather being torrid,

A gnat beheld him where he lay

And lit upon his forehead,

And thence, like all such winged creatures,

Proceeded over all his features.

The watchful bear, perceiving that

The gnat lit on her master,

Resolved to light upon the gnat

And plunge him in disaster;

She saw no sense in being lenient

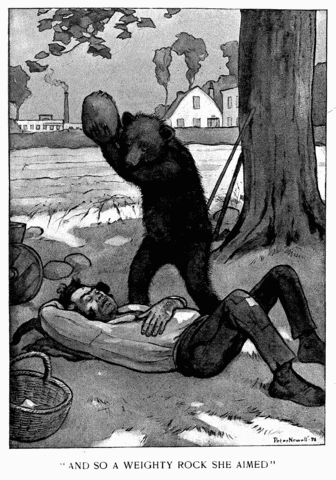

When stones lay round her, most convenient.

And so a weighty rock she aimed

With much enthusiasm:

"Oh, lor'!" the startled gnat exclaimed,

And promptly had a spasm:

A natural proceeding this was,

Considering how close the miss was.

Now by his dumb companion's pluck,

Which caused the gnat to squall so,

The sleeping man was greatly struck

(And by the bowlder, also).

In fact, his friends who idolized him

Remarked they hardly recognized him.

Of course the bear was greatly grieved,

But, being just a dumb thing,

She only thought: "I was deceived,

But still, I did hit something!"

Which showed this masculine achievement

Had somewhat soothed her deep bereavement.

THE MORAL: If you prize your bones

Beware of females throwing stones.

THE PRECIPITATE COCK AND THE UNAPPRECIATED PEARL

A rooster once pursued a worm

That lingered not to brave him,

To see his wretched victim squirm

A pleasant thrill it gave him;

He summoned all his kith and kin,

They hastened up by legions,

With quaint, expressive gurgles in

Their oesophageal regions.

Just then a kind of glimmering

Attracting his attention,

The worm became too small a thing

For more than passing mention:

The throng of hungry hens and rude

He skilfully evaded.

Said he, "I' faith, if this be food,

I saw the prize ere they did."

It was a large and costly pearl,

Belonging in a necklace,

And dropped by some neglectful girl:

Some people are so reckless!

The cock assumed an air forlorn,

And cried, "It's really cruel.

I thought it was a grain of corn:

It's nothing but a jewel."

He turned again to where his clan

In one astounding tangle

With eager haste together ran

To slay the helpless angle,

And sighed, "He was of massive size.

I should have used discretion.

Too late! Around the toothsome prize

A bargain-sale's in session."

The worm's remarks upon his plight

Have never been recorded,

But any one may know how slight

Diversion it afforded;

For worms and human beings are

Unanimous that, when pecked,

To be the prey of men they far

Prefer to being hen-pecked.

THE MORAL: When your dinner comes

Don't leave it for your neighbors,

Because you hear the sound of drums

And see the gleam of sabres;

Or, like the cock, you'll find too late

That ornaments external

Do not for certain indicate

A bona fide kernel.

THE ABBREVIATED FOX AND HIS SCEPTICAL COMRADES

A certain fox had a Grecian nose

And a beautiful tail. His friends

Were wont to say in a jesting way

A divinity shaped his ends.

The fact is sad, but his foxship had

A fault we should all eschew:

He was so deceived that he quite believed

What he heard from friends was true.

One day he found in a sheltered spot

A trap with stalwart springs

That was cunningly planned to supply the demand

For some of those tippet things.

The fox drew nigh, and resolved to try

The way that the trap was set:

(When the trap was through with this interview

There was one less tippet to get!)

The fox returned to his doting friends

And said, with an awkward smile,

"My tail I know was comme il

faut,

And served me well for a while."

When his comrades laughed at his shortage aft

He added, with scornful bow,

"Pray check your mirth, for I hear from Worth

They're wearing them shorter now."

But one of his friends, a bookish chap,

Replied, with a thoughtful frown,

"You know to-day the publishers say

That the short tale won't go down;

And, upon my soul, I think on the whole,

That the publishers' words are true.

I should hate, good sir, to part my fur

In the middle, as done by you."

And another added these truthful words

In the midst of the eager hush,

"We can part our hair 'most anywhere

So long as we keep the brush."

THE MORAL is this: It is never amiss

To treasure the things you've penned:

Preserve your tales, for, when all else fails,

They'll be useful things--in the end.

THE HOSPITABLE CALEDONIAN AND THE THANKLESS VIPER

A Caledonian piper

Who was walking on the wold

Nearly stepped upon a viper

Rendered torpid by the cold;

By the sight of her admonished,

He forbore to plant his boot,

But he showed he was astonished

By the way he muttered "Hoot!"

Now this simple-minded piper

Such a kindly nature had

That he lifted up the viper

And bestowed her in his plaid.

"Though the Scot is stern, at least he

No unhappy creature spurns,

'Sleekit, cowrin, tim'rous beastie,'"

Quoth the piper (quoting Burns).

This was unaffected kindness,

But there was, to state the fact,

Just a slight soupçon of blindness

In his charitable act.

If you'd watched the piper, shortly

You'd have seen him leap aloft,

As this snake, of ways uncourtly,

Bit him suddenly and oft.

There was really no excuse for

This, the viper's cruel work,

And the piper found a use for

Words he'd never learned at kirk;

But the biting was so thorough

That although the doctors tried,

Not the best in Edinburgh

Could assist him, and he died.

And THE MORAL is: The piper

Of the matter made a botch;

One can hardly blame the viper

If she took a nip of Scotch,

For she only did what he did,

And his nippie wasn't

small,

Otherwise, you see, he needed

Not have seen the snake at all.

THE IMPETUOUS BREEZE AND THE DIPLOMATIC SUN

A Boston man an ulster had,

An ulster with a cape that fluttered:

It smacked his face, and made him mad,

And polyglot remarks he uttered:

"I bought it at a bargain," said he,

"I'm tired of the thing already."

The wind that chanced to blow that day

Was easterly, and rather strong, too:

It loved to see the galling way

That clothes vex those whom they belong to:

"Now watch me," cried this spell of weather,

"I'll rid him of it altogether."

It whirled the man across the street,

It banged him up against a railing,

It twined the ulster round his feet,

But all of this was unavailing:

For not without resource it found him:

He drew the ulster closer round him.

"My word!" the man was heard to say,

"Although I like not such abuse, it's

Not strange the wind is strong to-day,

It always is in Massachusetts.

Such weather threatens much the health of

Inhabitants this Commonwealth of."

The sun, emerging from a rift

Between the clouds, observed the victim,

And how the wind beset and biffed,

Belabored, buffeted, and kicked him.

Said he, "This wind is doubtless new here:

'Tis quite the freshest ever blew here."

And then he put forth all his strength,

His warmth with might and main exerted,

Till upward in its tube at length

The mercury most nimbly spurted.

Phenomenal the curious sight was,

So swift the rise in Fahrenheit was.

The man supposed himself at first

The prey of some new mode of smelting:

His pulses were about to burst,

His every limb seemed slowly melting,

And, as the heat began to numb him,

He cast the ulster wildly from him.

"Impulsive breeze, the use of force,"

Observed the sun, "a foolish act is,

Perceiving which, you see, of course.

How highly efficacious tact is."

The wondering wind replied, "Good gracious!

You're right about the efficacious."

THE MORAL deals, as morals do,

With tact, and all its virtues boasted,

But still I can't forget, can you,

That wretched man, first chilled, then roasted?

Bronchitis seized him shortly after,

And that's no cause for vulgar laughter.

THE END

End of Project Gutenberg's Fables for the Frivolous, by Guy Whitmore Carryl