Produced by Ben Courtney, Sandy Brown, and the Distributed Proofreaders team

THE DANCEHistoric Illustrations

|

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER

I CHAPTER

II CHAPTER

III CHAPTER

IV CHAPTER

V CHAPTER

VI |

This sketch of the iconography of the dance does not pretend to be a history of the subject, except in the most elementary way. It may be taken as a summary of the history of posture; a complete dance cannot be easily rendered in illustration.

The text is of the most elementary description; to go into the subject thoroughly would involve years and volumes. The descriptions of the various historic dances or music are enormous subjects; two authors alone have given 800 dances in four volumes.[1]

It would have been interesting if some idea of the orchesography of the Egyptians and Greeks could have been given; this art of describing dances much in the manner that music is written is lost, and the attempts to revive it have been ineffective. The increasing speed of the action since the days of Lulli would now render it almost impossible.

It is hoped that this work may be of some use as illustrating the costume, position and accessories of the dance in various periods to those producing entertainments.

To the reader desirous of thoroughly studying the subject a bibliography is given at the end.

Footnote 1: Thompson's complete collection of 200 country dances performed at Court, Bath, Tunbridge, and all public assemblies, with proper figures and directions to each set for the violin, German flute, and hautboy, 8s. 6d. Printed for Charles and Samuel Thompson, St. Paul's Churchyard, London, where may be had the yearly dances and minuets. Four volumes, each 200 dances. 1770-1773.

Historic Illustrations of Dancing.

|

|

Fig. 1: Dancing to the clapping of bands.

Egyptian, from the tomb of Ur-ari-en-Ptah, 6th Dynasty, about

3300 B.C. (British Museum.)

|

In this work it is not necessary to worry the reader with speculations as to the origin of dancing. There are other authorities easily accessible who have written upon this theme.

Dancing is probably one of the oldest arts. As soon as man was man he without doubt began to gesticulate with face, body, and limbs. How long it took to develop bodily gesticulation into an art no one can guess—perhaps a millennium.

In writing of dancing, one will therefore include those gesticulations or movements of the body suggesting an idea, whether it be the slow movement of marching, or the rapid gallop, even some of the movements that we commonly call acrobatic. It is not intended here to include the more sensual movements of the East and the debased antique.

Generally the antique dances were connected with a religious ritual conceived to be acceptable to the Gods. This connection between dancing and religious rites was common up to the 16th century. It still continues in some countries.

In some of the earliest designs which have come down to us the dancers moved, as stars, hand in hand round an altar, or person, representing the sun; either in a slow or stately method, or with rapid trained gestures, according to the ritual performed.

Dancing, music and poetry were inseparable. Dancing is the poetry of motion, and its connection with music, as the poetry of sound, occurs at all times. In our own day musical themes are marked by forms originally dance times, as waltz time, gavotte time, minuet time, etc.

|

|

Fig. 2: Greek figures in a solemn dance.

From a vase at Berlin.

|

Amongst the earliest representations that are comprehensible, we have certain Egyptian paintings, and some of these exhibit postures that evidently had even then a settled meaning, and were a phrase in the sentences of the art. Not only were they settled at such an early period (B.C. 3000, fig. 1) but they appear to have been accepted and handed down to succeeding generations (fig. 2), and what is remarkable in some countries, even to our own times. The accompanying illustrations from Egypt and Greece exhibit what was evidently a traditional attitude. The hand-in-hand dance is another of these.

The earliest accompaniments to dancing appear to have been the clapping of hands, the pipes,[1] the guitar, the tambourine, the castanets, the cymbals, the tambour, and sometimes in the street, the drum.

The following account of Egyptian dancing is from Sir Gardiner Wilkinson's "Ancient Egypt"[2]:—

|

|

Fig. 3: The hieroglyphics describe the

dance.

|

"The dance consisted mostly of a succession of figures, in which the performers endeavoured to exhibit a great variety of gesture. Men and women danced at the same time, or in separate parties, but the latter were generally preferred for their superior grace and elegance. Some danced to slow airs, adapted to the style of their movement; the attitudes they assumed frequently partook of a grace not unworthy of the Greeks; and some credit is due to the skill of the artist who represented the subject, which excites additional interest from its being in one of the oldest tombs of Thebes (B.C. 1450, Amenophis II.). Others preferred a lively step, regulated by an appropriate tune; and men sometimes danced with great spirit, bounding from the ground, more in the manner of Europeans than of Eastern people. On these occasions the music was not always composed of many instruments, and here we find only the cylindrical maces and a woman snapping her fingers in the time, in lieu of cymbals or castanets.

"Graceful attitudes and gesticulations were the general style of their dance, but, as in all other countries, the taste of the performance varied according to the rank of the person by whom they were employed, or their own skill, and the dance at the house of a priest differed from that among the uncouth peasantry, etc.

"It was not customary for the upper orders of Egyptians to indulge in this amusement, either in public or private assemblies, and none appear to have practised it but the lower ranks of society, and those who gained their livelihood by attending festive meetings.

"Fearing lest it should corrupt the manners of a people naturally lively and fond of gaiety, and deeming it neither a necessary part of education nor becoming a person of sober habits, the Egyptians forbade those of the higher classes to learn it as an amusement.

"Many of these postures resembled those of the modern ballet, and the pirouette delighted an Egyptian party 3,500 years ago.

|

|

Fig. 4: Egyptian hieroglyphic for

"dance."

|

"The dresses of the females were light and of the finest texture, a loose flowing robe reaching to the ankles, sometimes with a girdle.

"In later times, it appears more transparent and folded in narrow pleats.[3] Some danced in pairs, holding each other's hand; others went through a succession of steps alone, both men and women; sometimes a man performed a solo to the sound of music or the clapping of hands.

"A favourite figure dance was universally adopted throughout the country, in which two partners, who were usually men, advanced toward each other, or stood face to face upon one leg, and having performed a series of movements, retired again in opposite directions, continuing to hold by one hand and concluding by turning each other round (see fig. 3). That the attitude was very common is proved by its having been adopted by the hieroglyphic (fig. 4) as the mode of describing 'dance.'"

Many of the positions of the dance illustrated in Gardner Wilkinson are used at the present day.

The ASSYRIANS probably danced as much as the other nations, but amongst the many monuments that have been discovered there is little dancing shown, and they were evidently more proud of their campaigns and their hunting than of their dancing. A stern and strong people, although they undoubtedly had this amusement, we know little about it. Of the Phoenicians, their neighbours, we have some illustrations of their dance, which was apparently of a serious nature, judging by the examples which we possess, such as that (fig. 5) from Cyprus representing three figures in hooded cowls dancing around a piper. It is a dance around a centre, as is also (fig. 6) that from Idalium in Cyprus. The latter is engraved around a bronze bowl and is evidently a planet and sun dance before a goddess, in a temple; the sun being the central object around which they dance, accompanied by the double pipes, the harp, and tabour. The Egyptian origin of the devotion is apparent in the details, especially in the lotus-smelling goddess (marked A on fig. 6) who holds the flower in the manner shown in an Egyptian painting in the British Museum (fig. 7).

|

|

Fig. 6: Phoenician patera, from Idalium,

showing a religious ritual dance before a goddess in a temple

round a sun emblem.

|

From the Phoenicians we have illustrated examples, but no record, whereas from their neighbours the Hebrews we have ample records in the Scriptures, but no illustrations. It is, however, most probable that the dance with them had the traditional character of the nations around them or who had held them captive, and the Philistine dance (fig. 6) may have been of the same kind as that around the golden calf (Apis) of the desert (Exodus xxxii. v. 19).

When they passed the Red Sea, Miriam and the maidens danced in chorus with singing and the beating of the timbrel (tambour). (Exodus xv. v. 1.)

|

|

Fig. 7: Female figure smelling a lotus. From

a painting in the British Museum.

|

King David not only danced before the ark (2 Samuel vi. v. 16), but mentions dancing in the 149th and 150th Psalm. Certain historians also tell us that they had dancing in their ritual of the seasons. Their dancing seems to have been associated with joy, as we read of "a time to mourn and a time to dance"; we find (Eccles. iii. v. 4) they had also the pipes: "We have piped to you and you have not danced" (Matthew xi. v. 17). These dances were evidently executed by the peoples themselves, and not by public performers.

Footnote 1: Egyptian music appears to have been of a complicated character and the double pipe or flutes were probably reeded, as with our clarionet. The left pipe had few stops and served as a sort of hautboy; the right had many stops and was higher. The single pipe, (a) "The recorder" in the British Museum, is a treble of 10-1/2 in. and is pentaphonic, like the Scotch scale; the tenor (b) is 8-3/4 in. long and its present pitch—

Footnote 2: Vol. i., p. 503-8.

Footnote 3: There is a picture of an Egyptian gauffering machine in Wilkinson, vol. i., p. 185.

|

|

Fig. 9: Dancing Bacchante. From a vase in

the British Museum.

|

|

|

Fig. 10: Greek terra cotta dancing girl,

about 350 B.C. (British Museum.)

|

With the Greeks, dancing certainly was primarily part of a religious rite; with music it formed the lyric art. The term, however, with them included all those actions of the body and limbs, and all expressions and actions of the features and head which suggest ideas; marching, acrobatic performances, and mimetic action all came into the term.

According to the historians, the Greeks attributed dancing to their deities: Homer makes Apollo orchestes, or the dancer; and amongst the early dances is that in his honour called the Hyporchema. Their dances may be divided into sections somewhat thus: (1) those of a religious species, (2) those of a gymnastic nature, (3) those of a mimetic character, (4) those of the theatre, such as the chorus, (5) those partly social, partly religious dances, such as the hymeneal, and (6) chamber dances.

Grown up men and women did not dance together, but the youth of both sexes joined in the Hormŏs or chain dance and the Gěrănŏs, or crane (see fig. 11).

According to some authorities, one of the most primitive of the first class, attributed to Phrygian origin, was the Aloenes, danced to the Phrygian flute by the priests of Cybele in honour of her daughter Ceres. The dances ultimately celebrated in her cult were numerous: such as the Anthema, the Bookolos, the Epicredros, and many others, some rustic for labourers, others of shepherds, etc. Every locality seems to have had a dance of its own. Dances in honour of Venus were common, she was the patroness of proper and decent dancing; on the contrary, those in honour of Dionysius or Bacchus degenerated into revelry and obscenity. The Epilenios danced when the grapes were pressed, and imitated the gathering and pressing. The Anteisterios danced when the wine was vatted (figs. 8, 9, 10), and the Bahilicos, danced to the sistrus, cymbals, and tambour, often degenerated into orgies.

The Gěrănŏs, originally from Delos, is said to have been originated by Theseus in memory of his escape from the labyrinth of Crete (fig. 12). It was a hand-in-hand dance alternately of males and females. The dance was led by the representative of Theseus playing the lyre.

|

|

Fig. 13: A military dance, supposed to be

the Corybantum. From a Greek bas-relief in the Vatican

Museum.

|

Of the second class, the gymnastic, the most important were military dances, the invention of which was attributed to Minerva; of these the Corybantum was the most remarkable. It was of Phrygian origin and of a mixed religious, military, and mimetic character; the performers were armed, and bounded about, springing and clashing their arms and shields to imitate the Corybantes endeavouring to stifle the cries of the infant Zeus, in Crete. The Pyrrhic (fig. 13), a war dance of Doric origin, was a rapid dance to the double flute, and made to resemble an action in battle; the Hoplites of Homer is thought to have been of this kind. The Dorians were very partial to this dance and considered their success in battle due to the celerity and training of the dance. In subsequent periods it was imitated by female dancers and as a pas seul. It was also performed in the Panathenaea by Ephebi at the expense of the Choragus, but this was probably only a mimetic performance and not warlike.

|

|

Fig. 14: Greek dancer with castanets.

(British Museum.) See also Castanet dance by Myron, fig.

63a.

|

|

|

Fig. 15: Cymbals (about 4 in.) and double

flute. (British Museum.)

|

There were many other heroic military dances in honour of Hercules, Theseus, etc.

The chorus, composed of singers and dancers, formed part of the drama, which included the recitation of some poetic composition, and included gesticulative and mimetic action as well as dancing and singing. The Dorians were especially fond of this; their poetry was generally choral, and the Doric forms were preserved by the Athenians in the choral compositions of their drama.

The tragic dance, Emmelia, was solemn; whilst that in comedy, Cordax, was frivolous, and the siccinis, or dance of Satyrs, was often obscene. They danced to the music of the pipes, the tambour, the harp, castanets, cymbals, etc. (figs. 14, 15, 16).

In the rites of Dionysius the chorus was fifty and the cithara was used instead of the flute. From the time of Sophocles it was fifteen, and always had a professed trainer. The choric question is, however, a subject in itself, and cannot be fairly dealt with here.

|

|

The social dances, and those in honour of the seasons, fire and water, were numerous and generally local; whilst the chamber dances, professional dancing, the throwing of the Kotabos, and such-like, must be left to the reader's further study of the authors mentioned in the bibliography at the end of the work.

It may astonish the reader to know that the funambulist or rope-dancer was very expert with the Greeks, as also was the acrobat between knives and swords. Animals were also taught to dance on ropes, even elephants.

The important religious and other dances were not generally composed of professionals. The greatest men were not above showing their sentiments by dancing. Sophocles danced after Salamis, and Epaminondas was an expert dancer. There were dancers of all grades, from the distinguished to the moderate. Distinguished persons even married into excellent positions, if they did not already occupy them by birth. Philip of Macedon married Larissa, a dancer, and the dancer Aristodemus was ambassador to his Court. These dancers must not be confounded with those hired to dance at feasts, etc. (figs. 9, 14 and 18).

|

|

Fig. 19: Etruscan bronze dancer with eyes of

diamonds, found at Verona. Now in the British Museum.

|

One of the most important nations of antiquity was the Etruscan, inhabiting, according to some authorities, a dominion from Lombardy to the Alps, and from the Mediterranean to the Adriatic.

Etruria gave a dynasty to Rome in Servius Tullius, who originally was Masterna, an Etruscan.

|

|

Fig. 20: Etruscan dancer. From a painting in

the Grotta dei Vasi dipinti—Corneto.

|

It is, however, with the dancing that we are dealing. There is little doubt that they were dancers in every sense; there are many ancient sepulchres in Etruria, with dancing painted on their walls. Other description than that of the pictures we do not possess, for as yet the language is a dead letter. There is no doubt, as Gerhardt [1] suggests, that they considered dancing as one of the emblems of joy in a future state, and that the dead were received with dancing and music in their new home. They danced to the music of the pipes, the lyre, the castanets of wood, steel, or brass, as is shown in the illustrations taken from the monuments.

|

|

Fig. 21: Etruscan dancing and performances.

From paintings in the Grotta della Scimia Corneto, about 500

B.C.

|

That the Phoenicians and Greeks had at certain times immense influence on the Etruscans is evident from their relics which we possess (fig. 20).

A characteristic illustration of the dancer is from a painting in the tomb of the Vasi dipinti, Corneto, which, according to Mr. Dennis, [2] belongs to the archaic period, and is perhaps as early as 600 B.C. It exhibits a stronger Greek influence than some of the paintings. Fig. 21, showing a military dance to pipes, with other sports, comes from the Grotta della Scimia, also at Corneto; these show a more purely Etruscan character.

|

|

Fig. 22: Etruscan Dancing. From the Grotta

del Triclinio.—Corneto.

|

The pretty dancing scene from the Grotta del Triclinio at Corneto is taken from a full-sized copy in the British Museum, and is of the greatest interest. It is considered to be of the Greco-Etruscan period, and later than the previous examples (fig. 22).

There is a peculiarity in the attitude of the hands, and of the fingers being kept flat and close together; it is not a little curious that the modern Japanese dance, as exhibited by Mme. Sadi Yacca, has this peculiarity, whether the result of ancient tradition or of modern revival, the writer cannot say.

Almost as interesting as the Etruscan are the illustrations of dancing found in the painted tombs of the Campagna and Southern Italy, once part of "Magna Grecia"; the figure of a funeral dance, with the double pipe accompaniments, from a painted tomb near Albanella (fig. 23) may be as late as 300 B.C., and those in figs. 24, 25 from a tomb near Capua are probably of about the same period. These Samnite dances appear essentially different from the Etruscan; although both Greek and Etruscan influence are very evident, they are more solemn and stately. This may, however, arise from a different national custom.

That the Etruscan, Sabellian, Oscan, Samnite, and other national dances of the country had some influence on the art in Rome is highly probable, but the paucity of early Roman examples renders the evidence difficult.

Rome as a conquering imperial power represented nearly the whole world of its day, and its dances accordingly were most numerous. Amongst the illustrations already given we have many that were preserved in Rome. In the beginning of its existence as a power only religious dances were practised, and many of these were of Etruscan origin, such as the Lupercalia, the Ambarvalia, &c. In the former the dancers were demi-nude, and probably originally shepherds; the latter was a serious dancing procession through fields and villages.

|

|

Fig. 24: Funeral dance. From Capua.

|

A great dance of a severe kind was executed by the Salii, priests of Mars, an ecclesiastical corporation of twelve chosen patricians. In their procession and dance, on March 1, and succeeding days, carrying the Ancilia, they sang songs and hymns, and afterwards retired to a great banquet in the Temple of Mars. That the practice was originally Etruscan may be gathered from the circumstance that on a gem showing the armed priests carrying the shields there are Etruscan letters. There were also an order of female Salii. Another military dance was the Saltatio bellicrepa, said to have been instituted by Romulus in commemoration of the Rape of the Sabines.

|

|

Fig. 25: Funeral dance from the same

tomb.

|

The Pyrrhic dance (fig. 13) was also introduced into Rome by Julius Caesar, and was danced by the children of the leading men of Asia and Bithynia.

As, however, the State increased in power by conquest, it absorbed with other countries other habits, and the art degenerated often, like that of Greece and Etruria, into a vehicle for orgies, when they brought to Rome with their Asiatic captives even more licentious practices and dances.

As Rome, which never rose to the intellectual and imaginative state of Greece in her best period, represented wealth, commerce, and conquest, in a greater degree, so were her arts, and with these the lyric. In her best state her nobles danced, Appius Claudius excelled, and Sallust tells us that Sempronia "psaltere saltare elegantius"; so that in those days ladies played and danced, but no Roman citizen danced except in the religious dances. They carried mimetic dances to a very perfect character in the time of Augustus under the term of Musica muta. After the second Punic war, as Greek habits made their way into Italy, it became a fashion for the young to learn to dance. The education in dancing and gesture were important in the actor, as masks prevented any display of feature. The position of the actor was never recognized professionally, and was considered infamia. But the change came, which caused Cicero to say "no one danced when sober." Eventually the performers of lower class occupied the dancing platform, and Herculaneum and Pompeii have shown us the results.

In the theatre the method of the Roman chorus differed from that of the Greeks. In the latter the orchestra or place for the dancing and chorus was about 12 ft. below the stage, with steps to ascend when these were required; in the former the chorus was not used in comedy, and having no orchestra was in tragedies placed upon the stage. The getting together of the chorus was a public service, or liturgia, and in the early days of Grecian prosperity was provided by the choregus.

|

|

Fig. 27: Bacchante. From a fresco, Pompeii,

1st century B.C.

|

Tiberius by a decree abolished the Saturnalia, and exiled the dancing teachers, but the many acts of the Senate to secure a better standard were useless against the foreign inhabitants of the Empire accustomed to sensuality and licence.

Perhaps the encouragement of the more brutal combats of the Coliseum did something to suppress the more delicate arts, but historians have told us, and it is common knowledge, what became of the great Empire, and the lyric with other arts were destroyed by licentious preferences.

|

|

Fig. 28: Dancer. From a fresco in the Baths

of Constantine, 4th century A.D.

|

The last illustration from the Baths of Constantine brought us into the Christian era, although that example was not of Christian sentiment or art. It is possible that the dance of Salome with its diabolical reward may have prejudiced the Apostolic era, for we find no example of dancing, as exhibiting joy, in Christian Art of that period. The dance before Herod is historical proof that the higher classes of Hebrews danced for amusement.

As soon, however, as Christianity became enthroned, and a settled society, we read of religious dances as exhibiting joy, even in the churches. Tertullian tells us that they danced to the singing of hymns and canticles. These dances were solemn and graceful to the old tones; and continued, notwithstanding many prohibitions such as those of Pope Zacharias (a Syrian) in A.D. 744. The dancing at Easter in the Cathedral at Paris was prohibited by Archbishop Odo in the 12th century, but notwithstanding the antagonism of the Fathers, the dances were only partially suppressed.

They were common on religious festivals in Spain and Portugal up to the seventeenth century and in some localities continue even to our own time. When S. Charles Borromeo was canonized in 1610, the Portuguese, who had him as patron, made a procession of four chariots of dancers; one to Renown, another to the City of Milan, one to represent Portugal and a fourth to represent the Church. In Seville at certain periods, and in the Balearic Isles, they still dance in religious ceremonies.

We know that religious dancing has continually been performed as an accessory to prayer, and is still so used by the Mahommedans, the American Indians and the Bedos of India, who dance into an ecstasy.

|

|

Fig. 29: Gleemen's dance, 9th century. From

Cleopatra, Cotton MS. C. viii., British Museum.

|

It is probable that this sort of mania marked the dancing in Europe which was suppressed by Pope and Bishop. This choreomania marked a Flemish sect in 1374 who danced in honour of St. John, and it was so furious that the disease called St. Vitus' dance takes its name from this performance.

Christmas carols were originally choric. The performers danced and sang in a circle.

The illustration (fig. 43) of a dance of angels and religious shows us that Fra Angelico thought the practice joyful; this dance is almost a counterpart of that amongst the Greeks (fig. 11). The other dance, by Sandro Botticelli (fig. 44), is taken from his celebrated "Nativity" in the National Gallery. Although we have records of performances in churches, no illustrations of an early date have come to the knowledge of the writer.

|

|

Fig. 30: Dancing to horn and pipe. From an

Anglo-Saxon MS.

|

That the original inhabitants of Britain danced—that the Picts, Danes, Saxons and Romans danced may be taken for granted, but there seems little doubt that our earliest illustrations of dancing were of the Roman tradition. We find the attitude, the instruments and the clapping of hands, all of the same undoubted classic character. Tacitus informs us that the Teutonic youths danced, with swords and spears, and Olaus Magnus that the Goths, &c., had military dances: still the military dances in English MSS. (figs. 31, 32) seem more like those of a Pyrrhic character, which Julius Caesar, the conqueror of England, introduced into Rome. The illustration (fig. 29) of what is probably a Saxon gleemen's dance shows us the kind of amusement they afforded and how they followed classic usages.

The gleemen were reciters, singers and dancers; and the lower orders were tumblers, sleight-of-hand men and general entertainers. What may have been the origin of our hornpipe is illustrated in fig. 30, where the figures dance to the sound of the horn in much the same attitudes as in the modern hornpipe, with a curious resemblance to the position in some Muscovite dances.

|

|

Fig. 32: Sword dance to bagpipes, 14th

century. From 2 B vii., Royal MS., British Museum.

|

The Norman minstrel, successor of the gleeman, used the double-pipe, the harp, the viol, trumpets, the horn and a small flat drum, and it is not unlikely that from Sicily and their South Italian possessions the Normans introduced classic ideas.

Piers the Plowman used words of Norman extraction for them, as he speaks of their "Saylen and Sauté."

The minstrel and harpist does not appear to have danced very much, but to have left this to the joculator, and dancing and tumbling and even acrobatic women and dancers appear to have become common before the time of Chaucer's "Tomblesteres."

|

|

Fig. 33: Herodias tumbling. From a MS. end

of 13th century (Addl. 18,719, f. 253b), British Museum.

|

That this tumbling and dancing was common in the thirteenth century is shown by the illustration from the sculpture at Rouen Cathedral (fig. 34), the illustrations from a MS. in the British Museum (fig. 33) of Herodias tumbling and of a design in glass in Lincoln, and other instances at Ely; Idsworth Church, Hants; Poncé, France, and elsewhere. It is suggested that the camp followers of the Crusaders brought back certain dances and amongst these some of an acrobatic nature, and many that were reprehensible, which brought down the anger of the Clergy.

|

|

Fig. 34: A tumbler, as caryatid. Rouen

Cathedral, 13th century.

|

In the fourteenth century, from a celebrated MS. (2 B. vii.) in the British Museum and other cognate sources we get a fair insight of the amusement afforded by these dancers and joculators. In the illustration (fig. 35) we get A and C tumblers, male and female; D, a woman and bear dance; and E, a dance of fools to the organ and bagpipe. It will be observed that they have bells on their caps, and it must have required much skill and practice to sound their various toned bells to the music as they danced. This dance of fools may have suggested or became eventually merged into the "Morris Dance" (fig. 50) of which some account with other illustrations of "Comic Dances" will be given hereafter. The man dancing and playing the pipes with a woman on his shoulder (fig. 36), the stilt dancer with a curious instrument (C), and the woman jumping through a hoop, give us other illustrations of fourteenth century amusements.

|

|

Fig. 37: Italian dance. From an engraving,

end of 15th century, attributed to Baccio Baldini.

|

|

|

Fig. 38: Italian dancing, the end of the

15th century.

|

Concerning the dance as a means of social intercourse, it does not appear to have been formulated as an accomplishment until late in the thirteenth century, and at a later date was cultivated as a means of teaching what we call deportment, until it became almost a necessity with the classes, as is shown by the literature of that period. The various social dances, such as the Volte, the Jig and the Galliard, although in early periods, not so numerous, required a certain training and agility. These, however, soon became complicated with many social and local variations, the characteristics of which are a study in themselves. The dances (figs. 37 and 38) in a field of sports, from an Italian engraving of the fifteenth century, show us nothing new; indeed, with different costumes it is very like what we have from Egypt (fig. 3), only a different phase of the action, and the attitude of this old dance is repeated even to our own time.

|

|

In the Chamber dance by Martin Zasinger (fig. 39), of the fifteenth century, no figures are in action, but we see an arrangement of the guests and musicians, from which it is evident that the Chamber dance as a social function had progressed and that the "Bal paré," etc., was here in embryo.

The flute and viol are evidently opening the function and the trumpets and other portions of the orchestra on the other side waiting to come in.

The stately out-door function, in a pleasure garden, from the "Roman de la Rose" (fig. 40) illustrates but one portion of the feature of a dance, another of which is described in Chaucer's translation:

"They threw y fere

Ther mouthes so that through their play

It seemed as they kyste alway."

Fancy dress and comic dances have handed down the same characteristics almost to our own time. The Wildeman costume dance (fig. 41) is interesting in many respects, it not only shows us the dance, but the costume and general method of the Chamber.

The fifteenth century comic dancers in a fête champétre (fig. 42) and those of the seventeenth century by Callot (fig. 52) are good examples of this entertainment—in the background of the latter a minuet seems to be in progress. The Morris dance (fig. 50) shows us the development that had taken place since the fourteenth century.

|

|

||||

|

|

Allusion has already been made to the beautiful paintings of Botticelli and Fra Angelico, which tell us of Italian choral dances of their period; these do not belong to social functions, but are certainly illustrative of the custom of their day. Albert Dürer (figs. 45, 46) has given us illustrations of the field dances of his period, but both these dances and those drawn by Sebald Beham (fig. 47) are coarse, and contrast unfavourably with the Italian, although the action is vigorous and robust.

The military dance of Dames and Knights of Armour, by Hans Burgkmair, on the other hand, appears stately and dignified (fig. 48). This may illustrate the difference between chamber and garden or field dancing.At the end of the sixteenth century we get a work on dancing which shows us completely its position as a social art in that day. It is the "Orchésographie" of Thoinot Arbeau (Jean Tabouret, Canon of Langres, in 1588), from which comes the illustration of the "Galliarde" (fig. 49) and to which I would refer the reader for all the information he desires concerning this period. In this work much stress is laid on the value of learning to dance from many points of view—development of strength, manner, habits and courtesy, etc. Alas! we know now that all these external habits can be acquired and leave the "natural man" beneath.

Desirable, therefore, as good manners and such like are, they do not fulfil all the requirements that the worthy Canon wished to be involved by them.[1]

We have have seen from the fourteenth century (figs. 35 C, 36 A, 46) how common the bagpipe was in out-of-door dances; in the illustrations from Dürer (fig. 46) and in fig. 53 from Holtzer it has developed, and has two accessory pipes, besides that played by the mouth, and the player is accompanied by a sort of clarionet. This also appears to be the only accompaniment of the Trio (fig. 58).

|

|

In the sixteenth century certain Spanish dances were introduced into France, such as la Pavane, which was accompanied by hautboys and sackbuts.

|

|

||||

|

|

There were, however, various other dances of a number too considerable to describe here, also introduced. The dance of the eighteenth century from Derby ware (fig. 59) seems to be but a continuation in action of those of the sixteenth century, as out-of-door performances.

|

|

Fig. 56: Caricature of a dancing master.

Hogarth.

|

We have now arrived at the modern style of ball, so beloved by many of the French Monarchs. Henry IV. and Napoleon were fond of giving these in grand style, and in some sort of grand style they persist even as a great social function to our own time. The Court balls of Louis XIII. and XIV. at Versailles were really gorgeous ballets, and their grandeur was astonishing; this custom was continued under the succeeding monarchs. An illustration of one in the eighteenth century by August de l'Aubin (fig. 54) sufficiently shows their character. There is nothing new in the postures illustrated, which may have originated thousands of years ago. As illustrating the popular ball of the period, the design by Hogarth (fig. 55) is an excellent contrast. The contredanse represented was originally the old country dance exported to France and returned with certain arrangements added. This is a topic we need not pursue farther, as almost every reader knows what social dancing now is.

|

|

||||

|

|

Footnote 1: The advice which he gives is valuable from its bearing on the customs of the 16th century. It even has great historical value, indicating the influence dancing has had on good manners. That the history of dancing is the history of manners may be too much insisted upon. For these reasons we insert these little known passages. The first has reference to the right way of proceeding at a ball.

"Having entered the place where the company is gathered for the dance, choose a good young lady (honneste damoiselle) and raising your hat or bonnet with your right hand you will conduct her to the ball with your left. She, wise and well trained, will tender her left and rise to follow you. Then in the sight of all you conduct her to the end of the room, and you will request the players of instruments to strike up a 'basse danse'; because otherwise through inadvertance they might strike up some other kind of dance. And when they commence to play you must commence to dance. And be careful, that they understand, in your asking for a 'basse danse,' you desire a regular and usual one. Nevertheless, if the air of one song on which* the 'basse danse' is formed pleases you more than another you can give the beginning of the strain to them."

"Capriol:—If the lady refuses, I shall feel very ashamed.

"Arbeau:—A well-trained lady never refuses him who so honours her as to lead her to the dance.

"Capriol:—I think so too, but in the meantime the shame of the refusal remains with me.

"Arbeau:—If you feel sure of another lady's graciousness, take her and leave aside this graceless one, asking her to excuse you for having been importunate; nevertheless, there are those who would not bear it so patiently. But it is better to speak thus than with bitterness, because in so doing you acquire a reputation for being gentle and humane, and to her will fall the character of a 'glorieuse' unworthy of the attention paid her."

"When the instrument player has ceased" continues our good Canon "make a deep bow by way of taking leave of the young lady and conduct her gently to the place whence you took her, whilst thanking her for the honour she has done you." Another extract is not wanting in flavour: "Hold the head and body straight, have a countenance of assurance, spit and cough little, and if necessity compels you, turn your face the other side and use a beautiful white handkerchief. Talk graciously, in gentle and honest speech, neither letting your hands hang as if dead or too full of gesticulation. Be dressed cleanly and neatly 'avec la chausse bien tirée et Pescarpin propre.'

"And bear in mind these particulars."

Although the theatrical ballet dance is comparatively modern, the elements of its formation are of the greatest antiquity; the chorus of dancers and the performances of the men in the Egyptian chapters represent without much doubt public dancing performances. We get singing, dancing, mimicry and pantomime in the early stages of Greek art, and the development of the dance rhythm in music is equally ancient.

The Alexandrine Pantomime, introduced into Rome about 30 B.C. by Bathillus and Pylades, appears to have been an entertainment approaching the ballet.

In the middle ages there were the mysteries and "masks"; the latter were frequent in England, and are introduced by Shakespere in "Henry VIII."

In Italy there appears to have been a kind of ballet in the 14th century, and from Italy, under the influence of Catharine de' Medici, came the ballet. Balthasar di Beaujoyeulx produced the first recorded ballet in France, in the Italian style, in 1582. This was, however, essentially a Court ballet.

The theatre ballet apparently arose out of these Court ballets. Henry III. and Henry IV., the latter especially, were very fond of these entertainments, and many Italians were brought to France to assist in them. Pompeo Diabono, a Savoyard, was brought to Paris in 1554 to regulate the Court ballets. At a later date came Rinuccini, the poet, a Florentine, as was probably Caccini, the musician. They had composed and produced the little operetta of "Daphne," which had been performed in Florence in 1597. Under these last-mentioned masters the ballet in France took somewhat of its present form. This passion for Court ballets continued under Louis XIII. and Louis XIV.

Louis XIII. as a youth danced in one of the ballets at St. Germain, it is said at the desire of Richelieu, who was an expert in spectacle. It appears that he was encouraged in these amusements to remedy fits of melancholy.

Louis XIV., at seven, danced in a masquerade, and afterwards not only danced in the ballet of "Cassandra," in 1651, but did all he could to raise the condition of the dance and encourage dancing and music. His influence, combined with that of Cardinal Richelieu, raised the ballet from gross and trivial styles to a dignity worthy of music, poetry and dancing. His uncle, Gaston of Orleans, still patronized the grosser style, but it became eclipsed by the better. Lulli composed music to the words of Molière and other celebrities; amongst notable works then produced was the "Andromeda" of Corneille, a tragedy, with hymns and dances, executed in 1650, at the Petit Bourbon.

The foundation of the theatrical ballet was, however, at the instigation of Mazarin, to prevent a lowering of tone in the establishment of the Académie de Danse under thirteen Academicians in 1661. This appears to have been merged into the Académie Royale de Musique et de Danse in 1669, which provided a proper training for débutants, under MM. Perrin and Cambert, whilst Beauchamp, the master of the Court ballets, had charge of the dancing. The first opera-ballet, the "Pomona" of Perrin and Cambert, was produced in 1671. To this succeeded many works of Lulli, to whom is attributed the increased speed in dance music and dancing, that of the Court ballets having been slow and stately.

The great production of the period appears to have been the "Triumph of Love" in 1681, with twenty scenes and seven hundred performers; amongst these were many of the nobility, and some excellent ballerine, such as Pesaut, Carré, Leclerc, and Lafontaine.

A detailed history of the ballet is, however, impossible here, and we must proceed to touch only on salient points. It passed from the Court to the theatre about 1680 and had two characteristics, one with feminine dancers, the other without.

It is not a little curious that wearing the mask, a revival of the antique, was practised in some of these ballets. The history of the opera-ballet of those days gives to us many celebrated names of musicians, such as Destouches, who gave new "verve" to ballet music, and Rameau. Jean Georges Noverre abolished the singing and established the five-act ballet on its own footing in 1776. In this it appears he had partly the advice of Garrick, whom he met in London. The names of the celebrated dancers are numerous, such as Pécourt, Blaudy (who taught Mlle. Camargo), Laval, Vestris, Germain, Prevost, Lafontaine, and Camargo (fig. 61), of the 18th century; Taglioni, Grisi, Duvernay, Cerito, Ellsler, etc., of the 19th century, to those of our own day. A fair notice of all of these would be a work in itself.

|

|

|

The introduction of the ballet into England was as late as 1734, when the French dancers, Mlle. Sallé, the rival of Mlle. Camargo, and Mlle. de Subligny made a great success at Covent Garden in "Ariadne and Galatea," and Mlle. Salle danced in her own choregraphic invention of "Pygmalion," since which time it has been popular in England, when those of the first class can be obtained. There are, however, some interesting and romantic circumstances connected with the ballet in London in the last century, which it will not be out of place to record here. Amongst the dancers of the last century of considerable celebrity were two already mentioned, Mlles. Duvernay (fig. 62) and Taglioni (fig. 64), whose names are recorded in the classic verse of "Ingoldsby."

|

|

Taglioni has not yet arrived in her stead."

Mlle. Duvernay was a Parisian, and commenced her study under Barrez, but subsequently was under Vestris and Taglioni, the father of the celebrity mentioned in the verse.

Duran hangs over the mantelpiece of the refectory of the presbytery.

Having made a great Parisian reputation, she came to London in 1833, and from that date until 1837 held the town, when she married Mr. Stephens Lyne Stephens, M.P., a gentleman of considerable wealth, but was left a childless widow in 1861, and retired to her estate at Lyneford Hall, Norfolk, living in retirement and spending her time in good works. She is said to have spent £100,000 in charities and churches, and that at Cambridge, dedicated to the English martyrs, was founded, completed, and endowed by her. She led a blameless and worthy life, and died in 1894. Her portrait by Mlle. Taglioni (fig. 64), her co-celebrity, married Count Gilbert de Voisins, a French nobleman, in 1847, and with her marriage came an ample fortune; unfortunately the bulk of this fortune was lost in the Franco-German war. With the courage of her character the Countess returned to London and gave lessons in dancing, etc., in which she was sufficiently successful to obtain a fair living. She died in 1884 at 80 years of age. Of the other celebrities of the period—Carlotta Grisi, Ferraris (fig. 65), and Fanny Ellsler (fig. 63)—some illustrations are given; besides these were Fanny Cerito, Lucile Grahn, a Dane, and some others of lesser notoriety performing in London at this great period of the ballet.

|

|

|

The recent encouragement of the classic ballet has introduced us to some exquisite dancers: amongst these are Mlle. Adeline Genée (fig. 66) and Mlle. Anna Pavlova (fig. 67); the latter, with M. Mordkin and a corps of splendid dancers, are from Russia, from whence also comes the important troupe now at the Alhambra with Mlle. Geltzer and other excellent dancers. The celebrated company at Covent Garden, and Lydia Kyasht at the Empire, are also Russian. It is not surprising that we get excellent dancing from Russia; the school The recent encouragement of the classic ballet has introduced us to some exquisite dancers: amongst these are Mlle. Adeline Genée (fig. 66) and Mlle. Anna Pavlova (fig. 67); the latter, with M. Mordkin and a corps of splendid dancers, are from Russia, from whence also comes the important troupe now at the Alhambra with Mlle. Geltzer and other excellent dancers. The celebrated company at Covent Garden, and Lydia Kyasht at the Empire, are also Russian. It is not surprising that we get excellent dancing from Russia; the school formed by Peter the Great about 1698 has been under State patronage ever since.

Notices of all the important dancers from Italy, Spain, Paris, or elsewhere, performing in England in recent years, would occupy considerable space, and the reader can easily obtain information concerning them elsewhere.

That the technique and speed of the classic dance has considerably increased is historically certain, and we must hope that this speed will not sacrifice graceful movement. Moreover, technique alone will not make the complete fine-artist: some invention is involved. Unfortunately, some modern attempts at invention seem crude and sensational, whilst lacking the exquisite technique desirable in all exhibitions of finished art.

Before concluding it is almost imperative to say something about the naked foot dancers, followers of Isidora Duncan. Some critics and a certain public have welcomed them; but is it not "sham antique"? It does not remind one of the really classic. Moreover, the naked foot should be of antique beauty, which in most of these cases it is not. Advertisements tell us that these dance are interpretations of classic music—Chopin, Weber, Brahms, etc.; they are not really interpretations, but distractions! We can hardly imagine that these composers intended their work for actual dancing. One can listen and be entranced; one sees the dancer's "interpretations" or "translations" and the music is degraded to a series of sham classic postures.

The idea that running about the stage in diaphanous costumes, with conventional mimicry and arm action, is classic or beautiful is a mistake; the term aesthetic may cover, but not redeem it. There is not even the art of the ordinary ballet-dancer discernible in these proceedings.

On another plane are such as the ballets in "Don Giovanni" and "Faust." Mozart and Gounod wrote these with a full knowledge of the method of interpretation and the persons who had been trained for that purpose—the performers fit the music and it fits them. This opera-ballet is also more in accordance with tradition before the time of Noverre.

Neither do the "popular" and curious exhibitions of Loie Fuller strike one as having a classic character, or future, of any consideration, pretty as they may be.

The operetta or musical comedy has given us some excellent art, especially at the end of the 19th century, when Sylvia Gray, Kate Vaughan, Letty Lind, Topsy Sinden, and others of like métier gave us skirt and drapery dancing.

This introduces us to the question of costume. That commonly used by the prima ballerina is certainly not graceful; it was apparently introduced about 1830, presumably to show the action and finished method of the lower extremities. If Fanny Ellsler and Duvernay could excel without this ugly contrivance, why is it necessary for others?

At the same time it is better than indifferent imitations of the Greek, or a return to the debased characteristics of Pompeiian art, in which the effect of the classic and fine character of the material are rendered in a sort of transparent muslin.

With these notices the author's object in this sketch is completed. Of the bal-masqué garden dances, public balls and such-like, he has no intention to treat; they are not classic dancing nor "art," with the exception perhaps of the Scottish reels. Nor is he interested in the dancing of savage tribes, nor in that of the East, although some few illustrations are given to illustrate traditions: for example, the use of the pipe and tabor in Patagonia, the dancer from Japan, winged, like that in the "Roman de la Rose" (fig. 40), and the religious dance of Tibet, showing the survival of the religious dance in some countries. In Mrs. Groves' book on dancing there is an excellent chapter on the Ritual dance as now practised, to which the reader can refer.

. "Lettres et Entretiens sur la Danse." Paris, 1825.

. "La Danse grecque antique." 1896.

. "Des Ballets anciens et modernes." 1682.

. "Histoire générale de la Danse sacrée et profane." 1723.

. "La Danse ancienne et moderne." 1754.

. "Lettres sur les Ballets." 1760.

. "La Danse de Lettres, &c." 1807.

. Dict. Hist, du Théâtre. 1885.

. "De la Saltation théâtrale." 1789.

. Gent. Septentr., Hy., Book III., Chap. VII. See Bourne's "Vulgar Antiqs.," p. 175.

. "Orchésographie." 1643.

. "Sports and Pastimes." London, 1801.

. Collection of 800 Dances. 4 vols. 1770-1773.

. "Dancing Master." 2nd ed. 1652.

. "Ancient Egyptians." 3 vols. London.

. "Etruria." 2 vols. London.

. "Dictionnaire de la Danse." 1802.

. "Traité de la Danse." Milan, 1830.

. "Code of Terpsichore." London, 1823.

. "La Danse à travers les Ages."

. "Histoire de la Danse à travers les Ages."

. "Notice sur les Danses du xvi. siècle."

. "Hebraie Pisauriensis, de practica seu arte trepudis, &c." 1463. MS. Bib. Nation.

. "Pisauriensis," ditto. MS. Bib. Nation. 1463.

. "Il Ballarino." 1581.

. "Nuovo Invenzioni di Balli." 1604.

. "Les Danses autrefois." 1887.

. "Dictionnaire de la Danse." Paris, 1895.

. "Le Maître à danser."

. "Principes de Chorégraphie." Paris, 1765.

. "Nouveau Guide de la Danse." 1888.

. "Guide complet de la Danse." 1858.

. "Discuzzioni sulla dansa pantomima." 1760.

. "De l'etat actuel de la danse." Lisbon, 1856.

. Traité de la danse, 1890.

. Nouveau Guide, 1888.

. "History of Dancing." London, 1890.

. "Nash Balet" (our Ballet). 1899. A History of the Russian Ballet, in Russian.

Fig. 1: Dancing to the clapping of bands. Egyptian, from the tomb of Ur-ari-en-Ptah, 6th Dynasty, about 3300 B.C. (British Museum.)

Fig. 2: Greek Figures in a solemn dance. From a vase at Berlin.

Fig. 3: The hieroglyphics describe the dance.

Fig. 4: Egyptian hieroglyphic for "dance."

Fig. 5: Cyprian limestone group of Phoenician dancers, about 6½ in. high. There is a somewhat similar group, also from Cyprus, in the British Museum. The dress, a hooded cowl, appears to be of great antiquity.

Fig. 6: Phoenician patera, from Idalium, showing a religious ritual dance before a goddess in a temple round a sun emblem.

Fig. 7: Female Figure smelling a lotus. From a painting in the British Museum.

Fig. 8: Dance of Bacchantes, painted by the ceramic painter, Hieron. (British Museum.)

Fig. 9: Dancing Bacchante. From a vase in the British Museum.

Fig. 10: Greek terra cotta dancing girl, about 350 B.C. (British Museum.)

Fig. 11: The Gěrănŏs from a vase in the Museo Borbonico, Naples.

Fig. 12: Panathenaeac dance, about the 4th century B.C.

Fig. 13: A military dance, supposed to be the Corybantum. From a Greek bas-relief in the Vatican Museum.

Fig. 14: Greek dancer with castanets. (British Museum.) See also Castanet dance by Myron, Fig. 63a.

Fig. 15: Cymbals (about 4 in.) and double flute. (British Museum.)

Fig. 16: Greek dancers. From a vase in the Hamilton Collection.

Fig. 17: Bacchanalian dancer. Vase from Nocera, Museum, Naples.

Fig. 18: Greek dancers and tumblers.

Fig. 19: Etruscan bronze dancer with eyes of diamonds, found at Verona. Now in the British Museum.

Fig. 20: Etruscan dancer. From a painting in the Grotta dei Vasi dipinti—Corneto.

Fig. 21: Etruscan dancing and performances. From paintings in the Grotta della Scimia Corneto, about 500 B.C.

Fig. 22: Etruscan Dancing. From the Grotta del Triclinio.—Corneto.

Fig. 23: Funeral dance in the obsequies of a female. From a painted tomb near Albanella.

Fig. 24: Funeral dance. From Capua.

Fig. 25: Funeral dance from the same tomb.

Fig. 26: Bacchante leading the Dionysian bull to the altar. Bas-relief in the Vatican.

Fig. 27: Bacchante. From a fresco, Pompeii, 1st century B.C.

Fig. 28: Dancer. From a fresco in the Baths of Constantine, 4th century A.D.

Fig. 29: Gleemen's dance, 9th century. From Cleopatra, Cotton MS. C. viii., British Museum.

Fig. 30: Dancing to horn and pipe. From an Anglo-Saxon MS.

Fig. 31: Anglo-Saxon sword dance. From the MS. Cleopatra, C. viii., British Museum.

Fig. 32: Sword dance to bagpipes, 14th century. From 2 B vii., Royal MS., British Museum.

Fig. 33: Herodias tumbling. From a MS. end of 13th century (Addl. 18,719, f. 253b), British Museum.

Fig. 34: A tumbler, as caryatid. Rouen Cathedral, 13th century.

Fig. 35: 14th century dancers. A and C are tumblers; B, tumbling and balancing to the tambour; D, a woman dancing around a whipped bear; E, jesters dancing.

Fig. 36: A, man dancing and playing pipes, carrying a woman; B, jumping through a hoop; C, a stilt dance. 14th century.

Fig. 37: Italian dance. From an engraving, end of 15th century, attributed to Baccio Baldini.

Fig. 38: Italian dancing, the end of the 15th century.

Fig. 39: Chamber dance, 15th century. From a drawing by Martin Zasinger.

Fig. 40: Dancing in a "pleasure garden," end of the 15th century. French, from the "Roman de la Rose," in the British Museum.

Fig. 41: Fancy dress dance of Wildemen of the 15th century. From MS. 4379 Harl, British Museum.

Fig. 42: Comic dance to pipe and tabor, end of 15th century. From pen drawing in the Mediaeval House Book in the Castle of Wolfegg, by the Master of the Amsterdam Cabinet.

Fig. 43: A dance of Angels and Saints.

Fig. 44: Dancing angels. From a 'Nativity' by Sandro Botticelli, circa 1500 A.D.

Fig. 45: Albert Dürer, 1514 A.D.

Fig. 46: Albert Dürer.

Fig. 47: Scenes from dances. German, dated 1546, by Hans Sebald Beham.

Fig. 48: A torchlight military dance of the early 16th century. From a picture by Hans Burgkmair.

Fig. 49: La Galliarde. From the "Orchésographie" of Thoinot Arbeau (Jean Tabourot), Langres, 1588.

Fig. 50: Morris dancers. From a window that was in the possession of George Tollett, Esq., Birtley, Staffordshire, 16th century.

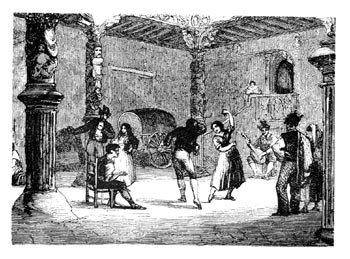

Fig. 51: Court dance. From a drawing by Callot, 1635 A.D.

Fig. 52: Comic dancers. By Callot, from the act entitled "Balli di Sfessama," 1609 A.D.

Fig. 53: Country dance. From a drawing by John Evangelist Holtzer, 17th century.

Fig. 54: A ball-room dance, Le Bal Paré, of the 18th century. From August de l'Aubin.

Fig. 55: A dance in the 18th century. From a painting by Hogarth.

Fig. 56: Caricature of a dancing master. Hogarth.

Fig. 57: Spring dancing away from winter. From a drawing by Watteau.

Fig. 58: The Misses Gunning dancing. End of the 18th century, from a print by Bunbury, engraved by Bartolozzi.

Fig. 59: Dancing. Close of the 18th century. From Derby ware.

Fig. 60: Spanish dance in the Hall of Saragoza, 19th century.

Fig. 61: Mlle. de Camargo. After a painting by Lancret, about 1740 A.D.

Fig. 62: Pauline Duvernay at Covent Garden, 1833-1838.

Fig. 63: Mlle. Fanny Ellsler. From a lithograph by A. Lacaucbie.

Fig. 63a: Dancing satyr playing castanets, by Myron, in the Vatican Museum. The action is entirely suggestive of that of Fanny Ellsler, and might be evidence of the antiquity of the Spanish tradition.

Fig. 64: Mlle. Taglioni. From a lithograph of the period.

Fig. 65: Pas de Trois by Mlles. Ferraris, Taglioni, and Carlotta Grisi.

Fig. 66: Mlle. Adeline Genée, 1906. Photo, Ellis and Walery.

Fig. 67: Mlle. Anna Pavlova, 1910. From a photo by Foulsham and Banfield.

Fig. 68: Mlle. Sophie Fédorova.

Fig. 69: Japanese Court Dance.

Fig. 70: Indian dancing-girl.

Fig. 71: Patagonian dancers to fife and tabor.

Fig. 72: Tibetan religious dancing procession, 1908 a.d.

End of Project Gutenberg's The Dance (by An Antiquary), by Anonymous