Mysteries of Creation, the World's Ages, and Soul Wandering

From Indian Myth and Legend by Donald A. Mackenzie 1913

BEFORE the Vedic Age had come to a close an unknown poet, who was one of the world's great thinkers, had risen above the popular materialistic ideas concerning the hammer god and the humanized spirits of Nature, towards the conception of the World Soul and the First Cause--the "Unknown God". He sang of the mysterious beginning of all things:

There was neither existence, nor non-existence,

The kingdom of air, nor the sky beyond.

What was there to contain, to cover in--

Was it but vast, unfathomed depths of water?

There was no death there, nor Immortality.

No sun was there, dividing day from night.

Then was there only THAT, resting within itself.

Apart from it, there was not anything.

At first within the darkness veiled in darkness,

Chaos unknowable, the All lay hid.

Till straightway from the formless void made manifest

By the great power of heat was born that germ.

Rigveda, x, 129 (Griffith's trans.).

The poet goes on to say that wise men had discovered in their hearts that the germ of Being existed in Not Being. But who, he asked, could tell how Being first originated? The gods came later, and are unable to reveal how Creation began. He who guards the Universe knows, or mayhap he does not know.

Other late Rigvedic poets summed up the eternal question regarding the Great Unknown in the interrogative pronoun "What?" (Ka). Men's minds were confronted by an inspiring and insoluble problem. In our own day the Agnostics say, "I do not know"; but this hackneyed phrase does not reflect the spirit of enquiry like the arresting "What?" of the pondering old forest hermits of ancient India.

The priests who systematized religious beliefs and practices in the Brahmanas identified "Ka" with Praja´pati, the Creator, and with Brahma, another name of the Creator.

In the Vedas the word "brahma" signifies "devotion" or "the highest religious knowledge". Later Brahmă (neuter) was applied to the World Soul, the All in All, the primary substance from which all that exists has issued forth, the Eternal Being "of which all are phases"; Brahmă was the Universal Self, the Self in the various Vedic gods, the Self in man, bird, beast, and fish, This Life of Life, the only reality, the unchangeable. This one essence or Self (Atman) permeates the whole Universe. Brahmă is the invisible force in the seed, as he is the "vital spark" in mobile creatures. In the Khandogya Upanishad a young Brahman receives instruction from his father. The sage asks if his pupil has ever endeavoured to find out how he can hear what cannot be heard, how he can see what cannot be seen, and how he can know what cannot be known? He then asks for the fruit of the Nyagrodha tree.

"Here is one, sir."

"Break it."

"It is broken, sir."

"What do you see there?"

"Not anything, sir."

"My son," said the father, "that subtile essence which you do not perceive there, of that very essence this great Nyagrodha tree exists. Believe it, my son. That which is the subtile essence, in it all that exists has itself. It is the True. It is the Self; and thou, my son, art it."

In Katha Upanishad a sage declares:

The whole universe trembles within the life (Brahmă); emanating from it (Brahmă) the universe moves on. It is a great fear, like an uplifted thunderbolt. Those who know it become immortal. . . .

As one is reflected in a looking-glass, so the soul is in the body; as in a dream, so in the world of the forefathers; as in water, so in the world of the Gandharvas; as in a picture and in the sunshine, so in the world of Brahmă. . . .

The soul's being (nature) is not placed in what is visible; none beholds it by the eye. . . . Through thinking it gets manifest Immortal became those who know it. . . .

The soul is not to be gained by word, not by the mind, not by the eye, how could it be perceived by any other than him who declares it exists?

When all the desires cease that are cherished in his heart (intellect) then the mortal becomes immortal.

When all the bonds of the heart are broken in this life, then the mortal becomes immortal. . . .1

The salvation of the soul is secured by union with Brahmă, the supreme and eternal Atman (Self), "the power which receives back to itself again all worlds. . . . The identity of the Brahmă and the Atman, of God and the Soul, is the fundamental thought of the entire doctrine of the Upanishads."2

Various creation myths were framed by teachers to satisfy the desire for knowledge regarding the beginning of things. The divine incarnation of Brahmă is known as Brahma (masculine) Prajapati, and Nãrãyana.

In one account we read: "At first the Universe was not anything. There was neither sky, nor earth, nor air. Being non-existent it resolved, 'Let me be'. It became fervent. From that fervour smoke was produced. It again became fervent. From that fervour fire was produced." Afterwards the fire became "rays" and the rays condensed like a cloud, producing the sea. A magical formula (Dásahotri) was next created. "Prajapati is the Dásahotri."

Eminently Brahmanic in character is the comment inserted here: "That man succeeds who, thus knowing the power of austere abstraction (or fervour), practises it."

When Prajapati arose from the primordial waters he "wept, exclaiming, 'For what purpose have I been born if (I have been born) from this which forms no support? . . .' That (the tears) which fell into the water became the earth. That which he wiped away became the air. That which he wiped away, upwards, became the sky. From the circumstance that he wept (arodít), these two regions have the name of rodasí (worlds) . . ."

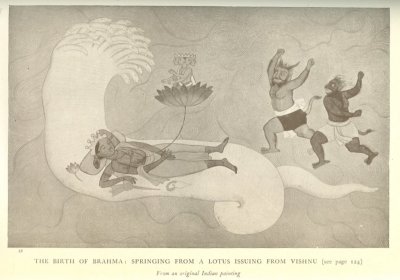

The birth of Brahma: springing from a Lotus issuing from Vishnu.

Prajapati afterwards created Asuras and cast off his body, which became darkness; he created men and cast off his body, which became moonlight; he created seasons and cast off his body, which became twilight; he created gods and cast off his body, which became day. The Asuras received milk in an earthen dish, men in a wooden dish, the seasons in a silver dish, and the gods were given Soma in a golden dish. In the end Prajapati created Death, "a devourer of creatures".

"Mind (or soul, manas) was created from the non-existent'', adds a priestly commentator. "Mind created Prajapati. Prajapati created offspring. All this, whatever exists, rests absolutely on mind."1

In another mythical account of Creation, Prajapati emerges, like the Egyptian Horus, from a lotus bloom floating on the primordial waters.

The most elaborate story of Creation is found in the Laws of Manu, the eponymous ancestor of mankind and the first lawgiver.

It relates that in the beginning the Self-Existent Being desired to create living creatures. He first created the waters, which he called "narah", and then a seed; he flung the seed into the waters, and it became a golden egg which had the splendour of the sun. From the egg came forth Brahma, Father of All. Because Brahma came from the "waters", and they were his first home or path (ayana), he is called Narayana.

The Egyptian sun god Ra similarly rose from the primordial waters as the sun-egg. Ptah came from the egg which, according to one myth, was laid by the chaos goose, and to another issued from the mouth of Khnumu2 This conception may have had origin in the story of the giant of the folk tales who concealed his soul in the egg, in the tree, and in various animal forms. There are references in Indian literature to Brahma's tree, and Brahma is identified with Purusha, who became in turn a cow, a goat, a horse, &c., to produce living creatures.

In Manu's account of Creation we meet for the first time with the Maha-rishis or Deva-rishis, the Celestial priest poets. These are the mind-born sons of Brahma, who came into existence before the gods and the demons. Indeed, they are credited with some acts of creation. The seven or fourteen Manus were also created at the beginning. Originally there was but a single Manu, "the father of men".

The inclusion of the Rishis and the Manus among the deities is a late development of orthodox Brahmanism. They appear to represent the Fathers (Pitris) who were adored by ancestor worshippers. The tribal patriarch Bhrigu, for instance, was a Celestial Rishi.

It must be borne in mind that more than one current of thought was operating during the course of the centuries, and over a wide area, in shaping the complex religion which culminated in modern Hinduism. The history of Hinduism is the history of a continual struggle between the devotees of folk religion and the expounders of the Forest Books produced by the speculative sages who, in their quest for Truth, used primitive myths to illustrate profound doctrinal teachings. By the common people these myths were given literal interpretation. Among the priests there were also "schools of thought". One class of Brahmans, it has been alleged, was concerned chiefly regarding ritual, the mercenary results of their teachings, and the achievement of political power: men of this type appear to have been too ready to effect compromises by making concession to popular opinion.

Just as the Atharva-veda came into existence as a book after the Rigveda had been compiled, so did many traditional beliefs of animistic character receive recognition by Brahmanic "schools" after the period of the early Upanishads. It may be, however, that we should also recognize in these "innovations" the influence of races which imported their own modes of thought, or of Aryan tribes that had been in contact for long periods with other civilizations known and unknown.

In endeavouring to trace the sources of foreign influences, we should not always expect to find clues in the mythologies of great civilizations like Babylonia, Assyria, or Egypt alone. The example of the Hebrews, a people who never invented anything, and yet produced the greatest sacred literature, of the world, is highly suggestive in this connection. It is possible that an intellectual influence was exercised in early times over great conquering races by humble forgotten peoples whose artifacts give no indication of their mental activity.

In Indian Aryan mythology we are suddenly confronted at a comparatively late period, at any rate some time after tribal settlements were effected all over Hindustan from the Bay of Bengal to the Arabian Sea, with fully developed conceptions regarding the World's Ages and Transmigration of Souls, which, it is quite evident, did not originate after the Aryan conquest of Hindustan. Both doctrines can be traced in Greek and Celtic (Irish) mythologies, but they are absent from Teutonic mythology. From what centre and what race they originally emanated we are unable to discover. The problem presented is a familiar one. At the beginnings of all ancient religious systems and great civilizations we catch glimpses of unknown and vanishing peoples who had sowed the seeds for the harvests which their conquerors reaped in season.

The World's Ages are the "Yugas" of Brahmanism. "Of this elaborate system . . . no traces are found in the hymns of the Rigveda. Their authors were, indeed, familiar with the word 'yuga', which frequently occurs in the sense of age, generation, or tribe. . . . The first passage of the Rigveda in which there is any indication of a considerable mundane period being noted is where 'a first' or an earlier age (yuga) of the gods is mentioned when `the existent sprang from the non-existent'. . . . In one verse of the Atharva-veda, however, the word 'yuga' is so employed as to lead to the supposition that a period of very long duration is intended. It is there said: 'We allot to thee a hundred, ten thousand years, two, three, four ages (yugas)'."1

Professor Muir traced references in the Brahmanas to the belief in "Yugas" as "Ages", but showed that these were isolated ideas with which, however, the authors of these books were becoming familiar.

When the system of Yugas was developed by the Indian priestly mathematicians, the result was as follows:--

One year of mortals is equal to one day of the gods. 12,000 divine years are equal to a period of four Yugas, which is thus made up, viz.:

|

Krita Yuga, |

with its mornings and evenings, |

4,800 |

divine years. |

|

Treta Yuga, |

"""" |

3,600 |

" |

|

Dwãpara Yuga, |

"""" |

2,400 |

" |

|

Kali Yuga, |

"""" |

1,200 |

" |

|

Making |

12,000 |

These 12,000 divine years equal 4,320,000 years of mortals, each human year being composed of 360 days. A thousand of these periods of 4,320,000 years equals one day (Kalpa) of Brahma. During "the day of Brahma" fourteen Manus reign: each Manu period is a Manvantara. A year of Brahma is composed of 360 Kalpas, and he endures for 100 of these years. One half of Brahma's existence has now expired.

At the end of each "day" (Kalpa) Brahma sleeps for a night of equal length, and before falling asleep the Universe becomes water as at the beginning. He creates anew when he wakes on the morning of the next Kalpa.1

One of the most interesting accounts of the Yugas is given in the Mahábhárata. It is embedded in a narrative which reflects a phase of the character of that great epic.

Bhima of the Pan´davas, the human son of the wind god Vayu, once went forth to obtain for his beloved queen the flowers of Paradise--those Celestial lotuses of a thousand petals with sun-like splendour and unearthly fragrance, which prolong life and renew beauty: they grow in the demon-guarded woodland lake in the region of Kuvera, god of treasure. Bhima hastened towards the north-east, facing the wind, armed with a golden bow and snake-like arrows; like an angry lion he went, nor ever felt weary. Having climbed a great mountain he entered a forest which is the haunt of demons, and he saw stately and beautiful trees, blossoming creepers, flowers of various hues, and birds with gorgeous plumage. A soft wind blew in his face; it was anointed with the perfume of Celestial lotus; it was as refreshing as the touch of a father's hand. Beautiful was that sacred retreat. The great clouds spread out like wings and the mountain seemed to dance; shining streams adorned it like to a necklace of pearls.

Bhima went speedily through the forest; stags, with grass in their mouths, looked up at him unafraid; invisible Yakshas and Gandharvas watched him as he went on swifter than the wind, and ever wondering how he could obtain the flowers of Paradise without delay. . . .

At length he hastened like to a hurricane, making the earth tremble under his feet, and lions and tigers and elephants and bears arose and took flight from before him. Terrible was then the roaring of Bhima. Birds fluttered terror-stricken and flew away; in confusion arose the geese and the ducks and the herons and the kokilas.1 . . . Bhima tore down branches; he struck trees and overthrew them; he smote and slew elephants and lions and tigers that crossed his path. He blew on his war-shell and the heavens trembled; the forest was stricken with fear. mountain caves echoed the clamour; elephants trumpeted in terror and lions howled dismally.

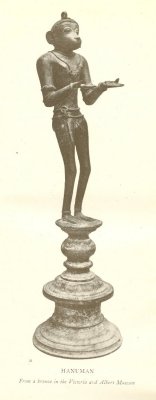

The ape god Hanuman2 was awakened; drowsily he yawned and he lashed his long tail with tempest fury until it stretched forth like a mighty pole and obstructed the path of Bhima. Thus the ape god, who was also a son of Vayu, the wind, made Bhima to pause. Opening his red sleepy eyes, he said: "Sick am I, but I was slumbering sweetly; why hast thou awakened me so rudely? Whither art thou going? Yonder mountains are closed against thee: thou art treading the path of the gods. Therefore pause and repose here: do not hasten to destruction."

Said Bhima: "Who art thou? I am a Kshatriya, the son of Vayu. . . . Arise and let me pass, or else thou wilt perish."

Hanuman said: "I am sickly and cannot move; leap over me."

HANUMAN

From a bronze in the Victoria and Albert Museum

Said Bhima: "I cannot leap over thee. It is forbidden by the Supreme Soul, else would I bound as Hanuman bounded over the ocean, for I am his brother."

Hanuman said: "Then move my tail and go past."

Then Bhima endeavoured to lift the tail of the ape god, but failed, and he said: "Who art thou that hath assumed the form of an ape; art thou a god, or a spirit, or a demon?"

Hanuman said: "I am the son of Vayu, even Hanuman. Thou art my elder brother."

Said Bhima: "I would fain behold the incomparable form thou didst assume to leap over the ocean."

Hanuman said: "At that Age the universe was not as it is now. Thou canst not behold the form I erstwhile had. . . . In Krita Yuga there was one state of things and in the Treta Yuga another; greater change came with Dwãpara Yuga, and in the present Yuga there is lessening, and I am not what I have been. The gods, the saints, and all things that are have changed. I have conformed with the tendency of the present age and the influence of Time."

Said Bhima: "I would fain learn of thee regarding the various Yugas. Speak and tell what thou dost know, O Hanuman."

The ape god then spake and said: "The Krita Yuga (Perfect Age) was so named because there was but one religion, and all men were saintly: therefore they were not required to perform religious ceremonies. Holiness never grew less, and the people did not decrease. There were no gods in the Krita Yuga, and there were no demons or Yakshas, and no Rakshasas or Nagas. Men neither bought nor sold; there were no poor and no rich; there was no need to labour, because all that men required was obtained by the power of will; the chief virtue was the abandonment of all worldly desires. The Krita Yuga was without disease; there was no lessening with the years; there was no hatred, or vanity, or evil thought whatsoever; no sorrow, no fear. All mankind could attain to supreme blessedness. The universal soul was Narayana: he was White; he was the refuge of all and was sought for by all; the identification of self with the universal soul was the whole religion of the Perfect Age.

"In the Treta Yuga sacrifices began, and the World Soul became Red; virtue lessened a quarter. Mankind sought truth and performed religious ceremonies; they obtained what they desired by giving and by doing.

"In the Dwãpara Yuga the aspect of the World Soul was Yellow: religion lessened one-half. The Veda, which was one (the Rigveda) in the Krita Yuga, was divided into four parts, and although some had knowledge of the four Vedas, others knew but three or one. Mind lessened, Truth declined, and there came desire and diseases and calamities; because of these men had to undergo penances. It was a decadent Age by reason of the prevalence of sin.

"In the Kali Yuga1 the World Soul is Black in hue: it is the Iron Age; only one quarter of virtue remaineth. The world is afflicted, men turn to wickedness; disease cometh; all creatures degenerate; contrary effects are obtained by performing holy rites; change passeth over all things, and even those who live through many Yugas must change also."

Having spoken thus, Hanuman bade Bhima to turn back, but Bhima said: "I cannot leave thee until I have gazed upon thy former shape."

Then Hanuman favoured his brother, and assumed his vast body; he grew till he was high as the Vindhya mountain: he was like to a great golden peak with splendour equal to the sun, and he said: "I can assume even greater height and bulk by reason of mine own power."

Having spoken thus, Hanuman permitted Bhima to proceed on his way under the protection of Vayu, god of wind. He went towards the flowery steeps of the sacred mountain, and at length he reached the Celestial lotus lake of Kuvera, which was shaded by trees and surrounded by lilies; the surface of the waters was covered with golden lotuses which had stalks of lapis lazuli. Yakshas, with big eyes, came out against Bhima, but he slew many, and those that remained were put to flight. He drank the waters of the lake, which renewed his strength. Then he gathered the Celestial lotuses for his queen.

In this tale we discover the ancient Indo-European myth regarding the earth's primitive races. The first age is the White Age, the second is the Red Age, the third the Yellow Age, and the fourth, the present Kali Yuga, is the Black or Iron Age.

Hesiod, the Greek poet, in his Works and Days, divided the mythical history of Greece similarly, but the order of the Ages was different; the first was the Golden Age (yellow); the second was the Silver Age (white); the third was the Bronze Age (red); the fourth was the Age of the Heroes; and the fifth was the Age in which Hesiod lived--the Iron (black) Age. The fourth Age is evidently a late interpolation. Authorities consider that the Heroic Age did not belong to the original scheme.

In the Greek Golden Age men lived like the gods under the rule of Kronos; they never suffered the ills of old age, nor lost their strength; they feasted continually, and enjoyed peace and security. The whole world prospered. When this race passed away they became beneficent spirits who watched over mankind and distributed riches.

In the Silver Age mankind were inferior; children were reared up for a century, and died soon afterwards; sacrifice and worship was neglected. In the end Zeus, son of Kronos, destroyed the Silver Race.

In the Bronze Age mankind sprang from the ash. They were endowed with great strength, and worked in bronze and had bronze houses: iron was unknown. But Bronze Age men were takers of life, and at length Black Death removed them all to Hades.

Zeus created the fourth race, which was represented by the semi-divine heroes of a former generation; when they fell in battle on the plain of Troy and elsewhere, Zeus consigned them to the Islands of the Blest, where they were ruled over by Kronos. The fifth Age may originally have been the fourth. As much is suggested by another Hesiodic legend which sets forth that all mankind are descended from two survivors of the Flood at the close of the Bronze Age.

In Le Cycle Mythologique Irlandais et la Mythologie Celtique, the late Professor D’Arbois de Jubainville has shown that these Ages are also a feature of Celtic (Irish) mythology. Their order, however, differs from those in Greek, but it is of special interest to note that they are arranged in exactly the same colour order as those given in the Mahábhárata. The first Celtic Age is that of Partholon, which de Jubainville identified with the Silver Age (white); the second is Nemed's, the Bronze Age (red); the third is the Tuatha de Danann, the Golden Age (yellow); and the fourth is the Age of the dark Milesians, called after their divine ancestor Mile, son of Beli, the god of night and death. The Irish claim descent from the Milesians.

Professor D’Arbois de Jubainville considered that the differences between the Irish and Greek versions of the ancient doctrine were due in part to the developments which Irish legend received after the introduction of Christianity. There are, however, he showed, striking affinities. The Tuatha de Danann, for instance, like the "Golden Race" of the Greeks, became invisible, and shared the dominion of the world with men, "sometimes coming to help them, sometimes disputing with them the pleasures of life".

Like the early Christian annalists of Ireland, the Indian Brahmans appear to have utilized the legends which were afloat among the people. Both in the Greek and Celtic (Irish) myths the people of the Silver Age are distinguished for their folly; in the Indian Silver or White Age the people were so perfect and holy that it was not necessary for them to perform religious ceremonies; they simply uttered the mystic word "Om".1

There are many interesting points of resemblance between certain of the Irish and Indian legends. We are informed, for instance, of the Celtic St. Finnen, who fasted like a Brahman, so to compel a pagan sage, Tuan MacCarell, to reveal the ancient history of Ireland. Tuan had lived all through the various mythical Ages; his father was the brother of Partholon, king of the "Silver Race". At the end of the First Age, Tuan was a "long-haired, grey, naked, and miserable old man". One evening he fell asleep, and when he woke up he rejoiced to find that he had become a young stag. He saw the people of Nemed (the Bronze or Red Race) arriving in Ireland; he saw them passing away. Then he was transformed into a black boar; afterwards he was a vulture, and in the end he became a fish. When he had existed as a fish for twenty years he was caught by a fisherman. The queen had Tuan for herself, and ate his fish form, with the result that she gave birth to the sage as her son.

In similar manner Bata of the Egyptian Anpu-Bata story,1 after existing as a blossom, a bull, and a tree, became the son of his unfaithful wife, who swallowed a chip of wood.

Tuan MacCarell assured St. Finnen, "in the presence of witnesses", as we are naively informed, that he remembered all that happened in Ireland during the period of 1500 years covered by his various incarnations.

Another, and apparently a later version of the legend, credits the Irish sage, the fair Fintan, son of Bochra, with having lived for 5550 years before the Deluge, and 5500 years after it. He fled to Ireland with the followers of Cesara, granddaughter of Noah, to escape the flood. Fintan, however, was the only survivor, and, according to Irish chronology, he did not die until the sixth century of the present era.

One of the long-lived Indian sages was named Markandeya. In the Vana Parva section of the Mahábhárata he visits the exiled Pandava brethren in a forest, and is addressed as "the great Muni, who has seen many thousands of ages passing away. In this world", says the chief exile, "there is no man who hath lived so long as thou hast. . . . Thou didst adore the Supreme Deity when the Universe was dissolved, and the world was without a firmament, and there were no gods and no demons. Thou didst behold the recreation of the four orders of beings when the winds were restored to their places and the waters were consigned to their proper place. . . . Neither death nor old age which causeth the body to decay have any power over thee."

Markandeya, who has full knowledge of the Past, the Present, and the Future, informs the exiles that the Supreme Being is "great, incomprehensible, wonderful, and immaculate, without beginning and without end. . . . He is the Creator of all, but is himself Increate, and is the cause of all power."1

After the Universe is dissolved, all Creation is renewed, and the cycle of the four Ages begins again with Krita Yuga. "A cycle of the Yugas comprises twelve thousand divine years. A full thousand of such cycles constitutes a Day of Brahma." At the end of each Day of Brahma comes "Universal Destruction".

Markandeya goes on to say that the world grows extremely sinful at the close of the last Kali Yuga of the Day of Brahma. Brahmans abstain from prayer and meditation, and Sudras take their place. Kshatriyas and Vaisyas forget the duties of their castes; all men degenerate and beasts of prey increase. The earth is ravaged by fire, cows give little milk, fruit trees no longer blossom, Indra sends no rain; the world of men becomes filled with sin and immorality. . . . Then the earth is swept by fire, and heavy rains fall until the forests and mountains are covered over by the rising flood. All the winds pass away; they are absorbed by the Lotus floating on the breast of the waters, in which the Creator sleeps; the whole Universe is a dark expanse of water.

Although even the gods and demons have been destroyed at the eventide of the last Yuga, Markandeya survives. He wanders over the face of the desolate waters and becomes weary, but is unable to find a resting-place. At length he perceives a banyan tree; on one of its boughs is a Celestial bed, and sitting on the bed is a beautiful boy whose face is as fair as a full-blown lotus, The boy speaks and says; "O Markandeya, I know that thou art weary. . . . Enter my body and secure repose. I am well pleased with thee."

Markandeya enters the boy's mouth and is swallowed. In the stomach of the Divine One the sage beholds the whole earth (that is, India) with its cities and kingdoms, its rivers and forests, and its mountains and plains; he sees also the gods and demons, mankind and the beasts of prey, birds and fishes and insects. . . .

The sage related that he shook with fear when he beheld these wonders, and desired the protection of the Supreme Being, whereat he was ejected from the boy's mouth, and found himself once again on the branch of the banyan tree in the midst of the wide expanse of dark waters.

Markandeya was then informed by the Lord of All regarding the mysteries which he had beheld. The Divine One spoke saying: "I have called the waters 'Nara', and because they were my 'Ayana', or home, I am Narayana, the source of all things, the Eternal, the Unchangeable. I am the Creator of all things, and the Destroyer of all things. . . . I am all the gods. . . . Fire is my mouth, the earth is my feet, and the sun and the moon are my eyes; the Heaven is the crown of my head, and the cardinal points are my ears; the waters are born of my sweat. Space with the cardinal points are my body, and the Air is in my mind."1

The Creator continues, addressing Markandeya: "I am the wind, I am the Sun, I am Fire. The stars are the pores of my skin, the ocean is my robe, my bed and my dwelling-place. . . ." The Divine One is the source of good and evil: "Lust, wrath, joy, fear, and the over-clouding of the intellect, are all different forms of me.

Men wander within my body, their senses are overwhelmed by me. . . . They move not according to their own will, but as they are moved by me."

Markandeya then related that the Divine Being said: "I create myself into new forms. I take my birth in the families of virtuous men. . . . I create gods and men, and Gandharvas and Rakshas and all immobile beings, and then destroy them all myself (when the time cometh). For the preservation of rectitude and morality, I assume a human form; and when the season for action cometh, I again assume forms that are inconceivable. In the Krita Age I become white, in the Treta Age I become yellow, in the Dwãpara I become red, and in the Kali Age I become dark in hue. . . . And when the end cometh, assuming the fierce form of Death, alone I destroy all the three worlds with their mobile and immobile existences. . . . Alone do I set agoing the wheel of Time: I am formless: I am the Destroyer of all creatures: and I am the cause of all efforts of all my creatures."1

Markandeya afterwards witnessed "the varied and wondrous creation starting into life".

The theory of Metempsychosis, or Transmigration of Souls, is generally regarded as being of post-Vedic growth in India as an orthodox doctrine. Still, it remains an open question whether it was not professed from the earliest times by a section of the various peoples who entered the Punjab at different periods and in various stages of culture. We have already seen that the burial customs differed. Some consigned the dead hero to the "House of Clay", invoking the earth to shroud him as a mother who covers her son with her robe, and the belief ultimately prevailed that Yama, the first man, had discovered the path leading to Paradise, which became known as the "Land of the Fathers" (Pitris). The fire worshippers, who identified Agni with the "vital spark", cremated the dead, believing that the soul passed to heaven like the burnt offering, which was the food of the gods. It is apparent, therefore, that in early times sharp differences of opinion existed among the tribes regarding the destiny of the soul. Other unsung beliefs may have obtained ere the Brahmans grew powerful and systematized an orthodox creed. The doctrine of Metempsychosis may have had its ancient adherents, although these were not at first very numerous. In one passage of the Rigveda "the soul is spoken of as departing to the waters or the plants", and it "may", says Professor Macdonell, "contain the germs of the theory" of Transmigration of Souls.1

The doctrine of Metempsychosis was believed in by the Greeks and the Celts. According to Herodotus the former borrowed it from Egypt, and although some have cast doubt on the existence of the theory in Egypt, there are evidences that it obtained there as in early Aryanized India among sections of the people.2 It is possible that the doctrine is traceable to a remote racial influence regarding which no direct evidence survives.

All that we know definitely regarding the definite acceptance of the theory in India is that in Satapatha Brahmana it is pointedly referred to as a necessary element of orthodox religion. The teacher declares that those who perform sacrificial rites are born again and attain to immortality, while those who neglect to sacrifice pass through successive existences until Death ultimately claims them.

According to Upanishadic belief the successive rebirths in the world are forms of punishment for sins committed, or a course of preparation for the highest state of existence.

In the code of Manu it is laid down, for instance, that he who steals gold becomes a rat, he who steals uncooked food a hedgehog, he who steals honey a stinging insect; a murderer may become a tiger, or have to pass through successive states of existence as a camel, a dog, a pig, a goat, &c.; other wrongdoers may have to exist as grass, trees, worms, snails, &c. As soon as a man died, it was believed that he was reborn as a child, or a reptile, as the case might be. Sufferings endured by the living were believed to be retribution for sins committed in a former life.

Another form of this belief had evidently some connection with lunar worship, or, at any rate, with the recognition of the influence exercised by the moon over life in all its phases; it is declared in the Upanishads that "all who leave this world go directly to the moon. By their lives its waxing crescent is increased, and by means of its waning it brings them to a second birth. But the moon is also the gate of the heavenly world, and he who can answer the questions of the moon is allowed to pass beyond it. He who can give no answer is turned to rain by the moon and rained down upon the earth. He is born again here below, as worm or fly, or fish or bird, or lion, or boar or animal with teeth, or tiger, or man, or anything else in one or another place, according to his works and his knowledge."1

Belief in Metempsychosis ultimately prevailed all over India, and it is fully accepted by Hinduism in our own day. Brahmans now teach that the destiny of the soul depends on the mental attitude of the dying person: if >his thoughts are centred on Brahma he enters the state of everlasting bliss, being absorbed in the World Soul; if, however, he should happen to think of a favourite animal or a human friend, the soul will be reborn as a cow, a horse, or a dog, or it may enter the body of a newly-born child and be destined to endure once again the ills that flesh is heir to.

In Egypt, according to Herodotus, the adherents of the Transmigration theory believed that the soul passed through many states of existence, until after a period of about three thousand years it once again reanimated the mummy. The Greeks similarly taught that "the soul continues its journey, alternating between a separate, unrestrained existence and fresh reincarnation, round the wide circle of necessity, as the companion of many bodies of men and animals".1 According to Cæsar, the Gauls professed the doctrine of Metempsychosis quite freely.2

Both in India and in Egypt the ancient doctrine of Metempsychosis was coloured by the theologies of the various cults which had accepted it. It has survived, however, in primitive form in the folk tales. Apparently the early exponents of the doctrine took no account of beginning or end; they simply recognized "the wide circle of necessity" round which the soul wandered, just as the worshippers of primitive nature gods and goddesses recognized the eternity of matter by symbolizing earth, air, and heaven as deities long ere they had conceived of a single act of creation.

Footnotes

100:1 Dr. E. Röer's translation (Calcutta).

100:2 Deussen's Philosophy of the Upanishads, p. 39.

101:1 Muir's Original Sanskrit Texts, vol. i, pp. 29-30.

101:2 See Egyptian Myth and Legend.

104:1 Muir's Original Sanskrit Texts, vol. i, p. 46.

105:1 Abridged from Muir's Original Sanskrit Texts, pp. 43, 44, and Wilson's Manu, p. 50.

106:1 Indian cuckoo.

106:2 In his character as the Typhoon.

108:1 The present Age, according to Hindu belief.

111:1 "Om" originally referred to the three Vedas; afterwards it signified the Trinity.

112:1 See Egyptian Myth and Legend.

113:1 Roy's translation.

114:1 Roy's translation. This conception of the World God resembles the Egyptian Ptah and Ra. See Egyptian Myth and Legend.

115:1 Mahabharata, Vana Parva, section clxxxix, P. C. Roy's translation.

116:1 History of Sanskrit Literature, p. 115.

116:2 See Egyptian Myth and Legend.

117:1 Paul Deussen's translation.

118:1 Psyche, Erwin Rhode.

118:2 De Bello Galileo, vi, xiv, 4.