|

|

Myths & Legends of China By E.T.C. Werner

H.B.M. Consul Foochow (Retired) Barrister-at-law Middle

Temple Late Member of The Chinese Government Historiographical

Bureau Peking Author of “Descriptive Sociology:

Chinese” “China of the Chinese” Etc.

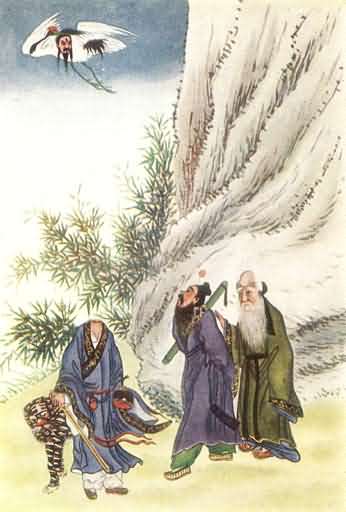

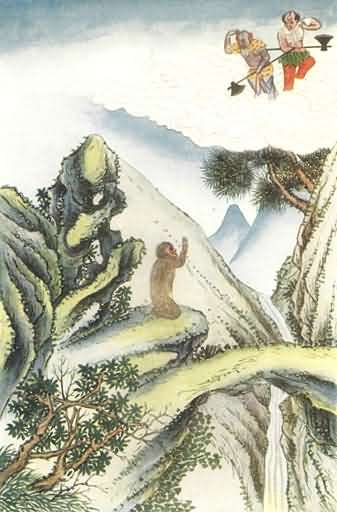

With Thirty-two Illustrations In Colours By Chinese Artists

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Myths and Legends of China, by E. T. C. Werner

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Jeroen Hellingman and the PG Online Distributed Proofreading Team.In Memoriam

Gladys Nina Chalmers Werner

Preface

The chief literary sources of Chinese myths are the Li tai shên hsien t’ung chien, in thirty-two volumes, the Shên hsien lieh chuan, in eight volumes, the Fêng shên yen i, in eight volumes, and the Sou shên chi, in ten volumes. In writing the following pages I have translated or paraphrased largely from these works. I have also consulted and at times quoted from the excellent volumes on Chinese Superstitions by Père Henri Doré, comprised in the valuable series Variétés Sinologiques, published by the Catholic Mission Press at Shanghai. The native works contained in the Ssŭ K’u Ch’üan Shu, one of the few public libraries in Peking, have proved useful for purposes of reference. My heartiest thanks are due to my good friend Mr Mu Hsüeh-hsün, a scholar of wide learning and generous disposition, for having kindly allowed me to use his very large and useful library of Chinese books. The late Dr G.E. Morrison also, until he sold it to a Japanese baron, was good enough to let me consult his extensive collection of foreign works relating to China whenever I wished, but owing to the fact that so very little work has been done in Chinese mythology by Western writers I found it better in dealing with this subject to go direct to the original Chinese texts. I am indebted to Professor H.A. Giles, and to his publishers, Messrs Kelly and Walsh, Shanghai, for permission to reprint from Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio the fox legends given in Chapter XV.

This is, so far as I know, the only monograph on Chinese mythology in any non-Chinese language. Nor do the native works include any scientific analysis or philosophical treatment of their myths. 8

My aim, after summarizing the sociology of the Chinese as a prerequisite to the understanding of their ideas and sentiments, and dealing as fully as possible, consistently with limitations of space (limitations which have necessitated the presentation of a very large and intricate topic in a highly compressed form), with the philosophy of the subject, has been to set forth in English dress those myths which may be regarded as the accredited representatives of Chinese mythology—those which live in the minds of the people and are referred to most frequently in their literature, not those which are merely diverting without being typical or instructive—in short, a true, not a distorted image.

Edward Theodore Chalmers Werner

Contents

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | The Sociology of the Chinese | 13 |

| II. | On Chinese Mythology | 60 |

| III. | Cosmogony—P’an Ku and the Creation Myth | 76 |

| IV. | The Gods of China | 93 |

| V. | Myths of the Stars | 176 |

| VI. | Myths of Thunder, Lightning, Wind, and Rain | 198 |

| VII. | Myths of the Waters | 208 |

| VIII. | Myths of Fire | 236 |

| IX. | Myths of Epidemics, Medicine, Exorcism, Etc. | 240 |

| X. | The Goddess of Mercy | 251 |

| XI. | The Eight Immortals | 288 |

| XII. | The Guardian of the Gate of Heaven | 305 |

| XIII. | A Battle of the Gods | 320 |

| XIV. | How the Monkey Became a God | 325 |

| XV. | Fox Legends | 370 |

| XVI. | Miscellaneous Legends | 386 |

| Glossary and Index | 425 |

Illustrations

Mais cet Orient, cette Asie, quelles en sont, enfin, les frontières réelles?... Ces frontières sont d’une netteté qui ne permet aucune erreur. L’Asie est là où cesse la vulgarité, où naît la dignité, et où commence l’élégance intellectuelle. Et l’Orient est là où sont les sources débordantes de poésie.

Mardrus,

La Reine de Saba

Chapter I

The Sociology of the Chinese

Racial Origin

In spite of much research and conjecture, the origin of the Chinese people remains undetermined. We do not know who they were nor whence they came. Such evidence as there is points to their immigration from elsewhere; the Chinese themselves have a tradition of a Western origin. The first picture we have of their actual history shows us, not a people behaving as if long settled in a land which was their home and that of their forefathers, but an alien race fighting with wild beasts, clearing dense forests, and driving back the aboriginal inhabitants.

Setting aside several theories (including the one that the Chinese are autochthonous and their civilization indigenous) now regarded by the best authorities as untenable, the researches of sinologists seem to indicate an origin (1) in early Akkadia; or (2) in Khotan, the Tarim valley (generally what is now known as Eastern Turkestan), or the K’un-lun Mountains (concerning which more presently). The second hypothesis may relate only to a sojourn of longer or shorter duration on the way from Akkadia to the ultimate settlement in China, especially since the Khotan civilization has been shown to have been imported from the Punjab in the third century B.C. The fact that serious mistakes have been made regarding the identifications of early Chinese rulers with Babylonian kings, and of the Chinese po-hsing (Cantonese bak-sing) ‘people’ with the Bak Sing or Bak tribes, does not exclude the possibility of an Akkadian origin. But in either case the immigration into China was probably 14gradual, and may have taken the route from Western or Central Asia direct to the banks of the Yellow River, or may possibly have followed that to the south-east through Burma and then to the north-east through what is now China—the settlement of the latter country having thus spread from south-west to north-east, or in a north-easterly direction along the Yangtzŭ River, and so north, instead of, as is generally supposed, from north to south.

Southern Origin Improbable

But this latter route would present many difficulties; it would seem to have been put forward merely as ancillary to the theory that the Chinese originated in the Indo-Chinese peninsula. This theory is based upon the assumptions that the ancient Chinese ideograms include representations of tropical animals and plants; that the oldest and purest forms of the language are found in the south; and that the Chinese and the Indo-Chinese groups of languages are both tonal. But all of these facts or alleged facts are as easily or better accounted for by the supposition that the Chinese arrived from the north or north-west in successive waves of migration, the later arrivals pushing the earlier farther and farther toward the south, so that the oldest and purest forms of Chinese would be found just where they are, the tonal languages of the Indo-Chinese peninsula being in that case regarded as the languages of the vanguard of the migration. Also, the ideograms referred to represent animals and plants of the temperate zone rather than of the tropics, but even if it could be shown, which it cannot, that these animals and plants now belong exclusively to the tropics, that would be no proof of the tropical origin of the Chinese, for in the earliest times the climate of North China was 15much milder than it is now, and animals such as tigers and elephants existed in the dense jungles which are later found only in more southern latitudes.

Expansion of Races from North to South

The theory of a southern origin (to which a further serious objection will be stated presently) implies a gradual infiltration of Chinese immigrants through South or Mid-China (as above indicated) toward the north, but there is little doubt that the movement of the races has been from north to south and not vice versa. In what are now the provinces of Western Kansu and Ssŭch’uan there lived a people related to the Chinese (as proved by the study of Indo-Chinese comparative philology) who moved into the present territory of Tibet and are known as Tibetans; in what is now the province of Yünnan were the Shan or Ai-lao (modern Laos), who, forced by Mongol invasions, emigrated to the peninsula in the south and became the Siamese; and in Indo-China, not related to the Chinese, were the Annamese, Khmer, Mon, Khasi, Colarains (whose remnants are dispersed over the hill tracts of Central India), and other tribes, extending in prehistoric times into Southern China, but subsequently driven back by the expansion of the Chinese in that direction.

Arrival of the Chinese in China

Taking into consideration all the existing evidence, the objections to all other theories of the origin of the Chinese seem to be greater than any yet raised to the theory that immigrants from the Tarim valley or beyond (i.e. from Elam or Akkadia, either direct or via Eastern Turkestan) struck the banks of the Yellow River in their eastward journey and followed its course until they 16reached the localities where we first find them settled, namely, in the region covered by parts of the three modern provinces of Shansi, Shensi, and Honan where their frontiers join. They were then (about 2500 or 3000 B.C.) in a relatively advanced state of civilization. The country east and south of this district was inhabited by aboriginal tribes, with whom the Chinese fought, as they did with the wild animals and the dense vegetation, but with whom they also commingled and intermarried, and among whom they planted colonies as centres from which to spread their civilization.

The K’un-lun Mountains

With reference to the K’un-lun Mountains, designated in Chinese mythology as the abode of the gods—the ancestors of the Chinese race—it should be noted that these are identified not with the range dividing Tibet from Chinese Turkestan, but with the Hindu Kush. That brings us somewhat nearer to Babylon, and the apparent convergence of the two theories, the Central Asian and the Western Asian, would seem to point to a possible solution of the problem. Nü Kua, one of the alleged creators of human beings, and Nü and Kua, the first two human beings (according to a variation of the legend), are placed in the K’un-lun Mountains. That looks hopeful. Unfortunately, the K’un-lun legend is proved to be of Taoist origin. K’un-lun is the central mountain of the world, and 3000 miles in height. There is the fountain of immortality, and thence flow the four great rivers of the world. In other words, it is the Sumêru of Hindu mythology transplanted into Chinese legend, and for our present purpose without historical value. 17

It would take up too much space to go into details of this interesting problem of the origin of the Chinese and their civilization, the cultural connexions or similarities of China and Western Asia in pre-Babylonian times, the origin of the two distinct culture-areas so marked throughout the greater part of Chinese history, etc., and it will be sufficient for our present purpose to state the conclusion to which the evidence points.

Provisional Conclusion

Pending the discovery of decisive evidence, the following provisional conclusion has much to recommend it—namely, that the ancestors of the Chinese people came from the west, from Akkadia or Elam, or from Khotan, or (more probably) from Akkadia or Elam via Khotan, as one nomad or pastoral tribe or group of nomad or pastoral tribes, or as successive waves of immigrants, reached what is now China Proper at its north-west corner, settled round the elbow of the Yellow River, spread north-eastward, eastward, and southward, conquering, absorbing, or pushing before them the aborigines into what is now South and South-west China. These aboriginal races, who represent a wave or waves of neolithic immigrants from Western Asia earlier than the relatively high-headed immigrants into North China (who arrived about the twenty-fifth or twenty-fourth century B.C.), and who have left so deep an impress on the Japanese, mixed and intermarried with the Chinese in the south, eventually producing the pronounced differences, in physical, mental, and emotional traits, in sentiments, ideas, languages, processes, and products, from the Northern Chinese which are so conspicuous at the present day. 18

Inorganic Environment

At the beginning of their known history the country occupied by the Chinese was the comparatively small region above mentioned. It was then a tract of an irregular oblong shape, lying between latitude 34° and 40° N. and longitude 107° and 114° E. This territory round the elbow of the Yellow River had an area of about 50,000 square miles, and was gradually extended to the sea-coast on the north-east as far as longitude 119°, when its area was about doubled. It had a population of perhaps a million, increasing with the expansion to two millions. This may be called infant China. Its period (the Feudal Period) was in the two thousand years between the twenty-fourth and third centuries B.C. During the first centuries of the Monarchical Period, which lasted from 221 B.C. to A.D. 1912, it had expanded to the south to such an extent that it included all of the Eighteen Provinces constituting what is known as China Proper of modern times, with the exception of a portion of the west of Kansu and the greater portions of Ssŭch’uan and Yünnan. At the time of the Manchu conquest at the beginning of the seventeenth century A.D. it embraced all the territory lying between latitude 18° and 40° N. and longitude 98° and 122° E. (the Eighteen Provinces or China Proper), with the addition of the vast outlying territories of Manchuria, Mongolia, Ili, Koko-nor, Tibet, and Corea, with suzerainty over Burma and Annam—an area of more than 5,000,000 square miles, including the 2,000,000 square miles covered by the Eighteen Provinces. Generally, this territory is mountainous in the west, sloping gradually down toward the sea on the east. It contains three chief ranges of mountains and large alluvial plains in the north, east, and south. Three great 19and about thirty large rivers intersect the country, their numerous tributaries reaching every part of it.

As regards geological features, the great alluvial plains rest upon granite, new red sandstone, or limestone. In the north is found the peculiar loess formation, having its origin probably in the accumulated dust of ages blown from the Mongolian plateau. The passage from north to south is generally from the older to the newer rocks; from east to west a similar series is found, with some volcanic features in the west and south. Coal and iron are the chief minerals, gold, silver, copper, lead, tin, jade, etc., being also mined.

The climate of this vast area is not uniform. In the north the winter is long and rigorous, the summer hot and dry, with a short rainy season in July and August; in the south the summer is long, hot, and moist, the winter short. The mean temperature is 50.3° F. and 70° F. in the north and south respectively. Generally, the thermometer is low for the latitude, though perhaps it is more correct to say that the Gulf Stream raises the temperature of the west coast of Europe above the average. The mean rainfall in the north is 16, in the south 70 inches, with variations in other parts. Typhoons blow in the south between July and October.

Organic Environment

The vegetal productions are abundant and most varied. The rice-zone (significant in relation to the cultural distinctions above noted) embraces the southern half of the country. Tea, first cultivated for its infusion in A.D. 350, is grown in the southern and central provinces between the twenty-third and thirty-fifth degrees of latitude, though it is also found as far north as Shantung, the chief ‘tea Page 20district,’ however, being the large area south of the Yangtzŭ River, east of the Tungting Lake and great Siang River, and north of the Kuangtung Province. The other chief vegetal products are wheat, barley, maize, millet, the bean, yam, sweet and common potato, tomato, eggplant, ginseng, cabbage, bamboo, indigo, pepper, tobacco, camphor, tallow, ground-nut, poppy, water-melon, sugar, cotton, hemp, and silk. Among the fruits grown are the date, mulberry, orange, lemon, pumelo, persimmon, lichi, pomegranate, pineapple, fig, coconut, mango, and banana, besides the usual kinds common in Western countries.

The wild animals include the tiger, panther, leopard, bear, sable, otter, monkey, wolf, fox, twenty-seven or more species of ruminants, and numerous species of rodents. The rhinoceros, elephant, and tapir still exist in Yünnan. The domestic animals include the camel and the water-buffalo. There are about 700 species of birds, and innumerable species of fishes and insects.

Sociological Environment

On their arrival in what is now known as China the Chinese, as already noted, fought with the aboriginal tribes. The latter were exterminated, absorbed, or driven south with the spread of Chinese rule. The Chinese “picked out the eyes of the land,” and consequently the non-Chinese tribes now live in the unhealthy forests or marshes of the south, or in mountain regions difficult of access, some even in trees (a voluntary, not compulsory promotion), though several, such as the Dog Jung in Fukien, retain settlements like islands among the ruling race.

In the third century B.C. began the hostile relations of 21the Chinese with the northern nomads, which continued throughout the greater part of their history. During the first six centuries A.D. there was intercourse with Rome, Parthia, Turkey, Mesopotamia, Ceylon, India, and Indo-China, and in the seventh century with the Arabs. Europe was brought within the sociological environment by Christian travellers. From the tenth to the thirteenth century the north was occupied by Kitans and Nüchêns, and the whole Empire was under Mongol sway for eighty-eight years in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Relations of a commercial and religious nature were held with neighbours during the following four hundred years. Regular diplomatic intercourse with Western nations was established as a result of a series of wars in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Until recently the nation held aloof from alliances and was generally averse to foreign intercourse. From 1537 onward, as a sequel of war or treaty, concessions, settlements, etc., were obtained by foreign Powers. China has now lost some of her border countries and large adjacent islands, the military and commercial pressure of Western nations and Japan having taken the place of the military pressure of the Tartars already referred to. The great problem for her, an agricultural nation, is how to find means and the military spirit to maintain her integrity, the further violation of which could not but be regarded by the student of sociological history as a great tragedy and a world-wide calamity.

Physical, Emotional, and Intellectual Characters

The physical characters of the Chinese are too well known to need detailed recital. The original immigrants into North China all belonged to blond races, but the 22modern Chinese have little left of the immigrant stock. The oblique, almond-shaped eyes, with black iris and the orbits far apart, have a vertical fold of skin over the inner canthus, concealing a part of the iris, a peculiarity distinguishing the eastern races of Asia from all other families of man. The stature and weight of brain are generally below the average. The hair is black, coarse, and cylindrical; the beard scanty or absent. The colour of the skin is darker in the south than in the north.

Emotionally the Chinese are sober, industrious, of remarkable endurance, grateful, courteous, and ceremonious, with a high sense of mercantile honour, but timorous, cruel, unsympathetic, mendacious, and libidinous.

Intellectually they were until recently, and to a large extent still are, non-progressive, in bondage to uniformity and mechanism in culture, imitative, unimaginative, torpid, indirect, suspicious, and superstitious.

The character is being modified by intercourse with other peoples of the earth and by the strong force of physical, intellectual, and moral education.

Marriage in Early Times

Certain parts of the marriage ceremonial of China as now existing indicate that the original form of marriage was by capture—of which, indeed, there is evidence in the classical Book of Odes. But a regular form of marriage (in reality a contract of sale) is shown to have existed in the earliest historical times. The form was not monogamous, though it seems soon to have assumed that of a qualified monogamy consisting of one wife and one or more concubines, the number of the latter being as a rule limited only by the means of the husband. The higher the rank the larger was the number of concubines 23and handmaids in addition to the wife proper, the palaces of the kings and princes containing several hundreds of them. This form it has retained to the present day, though associations now exist for the abolition of concubinage. In early times, as well as throughout the whole of Chinese history, concubinage was in fact universal, and there is some evidence also of polyandry (which, however, cannot have prevailed to any great extent). The age for marriage was twenty for the man and fifteen for the girl, celibacy after thirty and twenty respectively being officially discouraged. In the province of Shantung it was usual for the wives to be older than their husbands. The parents’ consent to the betrothal was sought through the intervention of a matchmaker, the proposal originating with the parents, and the wishes of the future bride and bridegroom not being taken into consideration. The conclusion of the marriage was the progress of the bride from the house of her parents to that of the bridegroom, where after various ceremonies she and he worshipped his ancestors together, the worship amounting to little more than an announcement of the union to the ancestral spirits. After a short sojourn with her husband the bride revisited her parents, and the marriage was not considered as finally consummated until after this visit had taken place.

The status of women was low, and the power of the husband great—so great that he could kill his wife with impunity. Divorce was common, and all in favour of the husband, who, while he could not be divorced by her, could put his wife away for disobedience or even for loquaciousness. A widower remarried immediately, but refusal to remarry by a widow was esteemed an act of chastity. She often mutilated herself or even committed 24suicide to prevent remarriage, and was posthumously honoured for doing so. Being her husband’s as much in the Otherworld as in this, remarriage would partake of the character of unchastity and insubordination; the argument, of course, not applying to the case of the husband, who by remarriage simply adds another member to his clan without infringing on anyone’s rights.

Marriage in Monarchical and Republican Periods

The marital system of the early classical times, of which the above were the essentials, changed but little during the long period of monarchical rule lasting from 221 B.C. to A.D. 1912. The principal object, as before, was to secure an heir to sacrifice to the spirits of deceased progenitors. Marriage was not compulsory, but old bachelors and old maids were very scarce. The concubines were subject to the wife, who was considered to be the mother of their children as well as her own. Her status, however, was not greatly superior. Implicit obedience was exacted from her. She could not possess property, but could not be hired out for prostitution. The latter vice was common, in spite of the early age at which marriage took place and in spite of the system of concubinage—which is after all but a legalized transfer of prostitutional cohabitation to the domestic circle.

Since the establishment of the Republic in 1912 the ‘landslide’ in the direction of Western progress has had its effect also on the domestic institutions. But while the essentials of the marriage contract remain practically the same as before, the most conspicuous changes have been in the accompanying ceremonial—now sometimes quite foreign, but in a very large, perhaps the greatest, number of cases that odious thing, half foreign, half 25Chinese; as, for instance, when the procession, otherwise native, includes foreign glass-panelled carriages, or the bridegroom wears a ‘bowler’ or top-hat with his Chinese dress—and in the greater freedom allowed to women, who are seen out of doors much more than formerly, sit at table with their husbands, attend public functions and dinners, dress largely in foreign fashion, and play tennis and other games, instead of being prisoners of the ‘inner apartment’ and household drudges little better than slaves.

One unexpected result of this increased freedom is certainly remarkable, and is one not likely to have been predicted by the most far-sighted sociologist. Many of the ‘progressive’ Chinese, now that it is the fashion for Chinese wives to be seen in public with their husbands, finding the uneducated, gauche, small-footed household drudge unable to compete with the smarter foreign-educated wives of their neighbours, have actually repudiated them and taken unto themselves spouses whom they can exhibit in public without ‘loss of face’! It is, however, only fair to add that the total number of these cases, though by no means inconsiderable, appears to be proportionately small.

Parents and Children

As was the power of the husband over the wife, so was that of the father over his children. Infanticide (due chiefly to poverty, and varying with it) was frequent, especially in the case of female children, who were but slightly esteemed; the practice prevailing extensively in three or four provinces, less extensively in others, and being practically absent in a large number. Beyond the fact that some penalties were enacted against it by the Emperor Ch’ien Lung (A.D. 1736–96), and that by statute 26it was a capital offence to murder children in order to use parts of their bodies for medicine, it was not legally prohibited. When the abuse became too scandalous in any district proclamations condemning it would be issued by the local officials. A man might, by purchase and contract, adopt a person as son, daughter, or grandchild, such person acquiring thereby all the rights of a son or daughter. Descent, both of real and personal property, was to all the sons of wives and concubines as joint heirs, irrespective of seniority. Bastards received half shares. Estates were not divisible by the children during the lifetime of their parents or grandparents.

The head of the family being but the life-renter of the family property, bound by fixed rules, wills were superfluous, and were used only where the customary respect for the parents gave them a voice in arranging the details of the succession. For this purpose verbal or written instructions were commonly given.

In the absence of the father, the male relatives of the same surname assumed the guardianship of the young. The guardian exercised full authority and enjoyed the surplus revenues of his ward’s estate, but might not alienate the property.

There are many instances in Chinese history of extreme devotion of children to parents taking the form of self-wounding and even of suicide in the hope of curing parents’ illnesses or saving their lives.

Political History

The country inhabited by the Chinese on their arrival from the West was, as we saw, the district where the modern provinces of Shansi, Shensi, and Honan join. This they extended in an easterly direction to the shores 27of the Gulf of Chihli—a stretch of territory about 600 miles long by 300 broad. The population, as already stated, was between one and two millions. During the first two thousand years of their known history the boundaries of this region were not greatly enlarged, but beyond the more or less undefined borderland to the south were chou or colonies, nuclei of Chinese population, which continually increased in size through conquest of the neighbouring territory. In 221 B.C. all the feudal states into which this territory had been parcelled out, and which fought with one another, were subjugated and absorbed by the state of Ch’in, which in that year instituted the monarchical form of government—the form which obtained in China for the next twenty-one centuries.

Though the origin of the name ‘China’ has not yet been finally decided, the best authorities regard it as derived from the name of this feudal state of Ch’in.

Under this short-lived dynasty of Ch’in and the famous Han dynasty (221 B.C. to A.D. 221) which followed it, the Empire expanded until it embraced almost all the territory now known as China Proper (the Eighteen Provinces of Manchu times). To these were added in order between 194 B.C. and A.D. 1414: Corea, Sinkiang (the New Territory or Eastern Turkestan), Manchuria, Formosa, Tibet, and Mongolia—Formosa and Corea being annexed by Japan in 1895 and 1910 respectively. Numerous other extra-China countries and islands, acquired and lost during the long course of Chinese history (at one time, from 73 to 48 B.C., “all Asia from Japan to the Caspian Sea was tributary to the Middle Kingdom,” i.e. China), it is not necessary to mention here. During the Southern Sung dynasty (1127–1280) the Tartars owned the northern half of China, as far Page 28down as the Yangtzŭ River, and in the Yüan dynasty (1280–1368) they conquered the whole country. During the period 1644–1912 it was in the possession of the Manchus. At present the five chief component peoples of China are represented in the striped national flag (from the top downward) by red (Manchus), yellow (Chinese), blue (Mongolians), white (Mohammedans), and black (Tibetans). This flag was adopted on the establishment of the Republic in 1912, and supplanted the triangular Dragon flag previously in use. By this time the population—which had varied considerably at different periods owing to war, famine, and pestilence—had increased to about 400,000,000.

General Government

The general division of the nation was into the King and the People, The former was regarded as appointed by the will of Heaven and as the parent of the latter. Besides being king, he was also law-giver, commander-in-chief of the armies, high priest, and master of ceremonies. The people were divided into four classes: (1) Shih, Officers (later Scholars), consisting of Ch’ên, Officials (a few of whom were ennobled), and Shên Shih, Gentry; (2) Nung, Agriculturists; (3) Kung, Artisans; and (4) Shang, Merchants.

For administrative purposes there were at the seat of central government (which, first at P’ing-yang—in modern Shansi—was moved eleven times during the Feudal Period, and was finally at Yin) ministers, or ministers and a hierarchy of officials, the country being divided into provinces, varying in number from nine in the earliest times to thirty-six under the First Emperor, 221 B.C., and finally twenty-two at the present day. At first these 29provinces contained states, which were models of the central state, the ruler’s ‘Middle Kingdom.’ The provincial administration was in the hands of twelve Pastors or Lord-Lieutenants. They were the chiefs of all the nobles in a province. Civil and military offices were not differentiated. The feudal lords or princes of states often resided at the king’s court, officers of that court being also sent forth as princes of states. The king was the source of legislation and administered justice. The princes in their several states had the power of rewards and punishments. Revenue was derived from a tithe on the land, from the income of artisans, merchants, fishermen, foresters, and from the tribute brought by savage tribes.

The general structure and principles of this system of administration remained the same, with few variations, down to the end of the Monarchical Period in 1912. At the end of that period we find the emperor still considered as of divine descent, still the head of the civil, legislative, military, ecclesiastical, and ceremonial administration, with the nation still divided into the same four classes. The chief ministries at the capital, Peking, could in most cases trace their descent from their prototypes of feudal times, and the principal provincial administrative officials—the Governor-General or Viceroy, governor, provincial treasurer, judge, etc.—had similarly a pedigree running back to offices then existing—a continuous duration of adherence to type which is probably unique.

Appointment to office was at first by selection, followed by an examination to test proficiency; later was introduced the system of public competitive literary examinations for office, fully organized in the seventeenth century, and abolished in 1903, when official positions were thrown open to the graduates of colleges established on a modern basis. Page 30

In 1912, on the overthrow of the Manchu monarchy, China became a republic, with an elected President, and a Parliament consisting of a Senate and House of Representatives. The various government departments were reorganized on Western lines, and a large number of new offices instituted. Up to the present year the Law of the Constitution, owing to political dissension between the North and the South, has not been put into force.

Laws

Chinese law, like primitive law generally, was not instituted in order to ensure justice between man and man; its object was to enforce subordination of the ruled to the ruler. The laws were punitive and vindictive rather than reformatory or remedial, criminal rather than civil. Punishments were cruel: branding, cutting off the nose, the legs at the knees, castration, and death, the latter not necessarily, or indeed ordinarily, for taking life. They included in some cases punishment of the family, the clan, and the neighbours of the offender. The lex talionis was in full force.

Nevertheless, in spite of the harsh nature of the punishments, possibly adapted, more or less, to a harsh state of society, though the “proper end of punishments”—to “make an end of punishing”—was missed, the Chinese evolved a series of excellent legal codes. This series began with the revision of King Mu’s Punishments in 950 B.C., the first regular code being issued in 650 B.C., and ended with the well-known Ta Ch’ing lü li (Laws and Statutes of the Great Ch’ing Dynasty), issued in A.D. 1647. Of these codes the great exemplar was the Law Classic drawn up by Li K’uei (Li K’uei fa ching), a statesman in the service of the first ruler of the Wei 31State, in the fourth century B.C. The Ta Ch’ing lü li has been highly praised by competent judges. Originally it sanctioned only two kinds of punishment, death and flogging, but others were in use, and the barbarous ling ch’ih, ‘lingering death’ or ‘slicing to pieces,’ invented about A.D. 1000 and abolished in 1905, was inflicted for high treason, parricide, on women who killed their husbands, and murderers of three persons of one family. In fact, until some first-hand knowledge of Western systems and procedure was obtained, the vindictive as opposed to the reformatory idea of punishments continued to obtain in China down to quite recent years, and has not yet entirely disappeared. Though the crueller forms of punishment had been legally abolished, they continued to be used in many parts. Having been joint judge at Chinese trials at which, in spite of my protests, prisoners were hung up by their thumbs and made to kneel on chains in order to extort confession (without which no accused person could be punished), I can testify that the true meaning of the “proper end of punishments” had no more entered into the Chinese mind at the close of the monarchical régime than it had 4000 years before.

As a result of the reform movement into which China was forced as an alternative to foreign domination toward the end of the Manchu Period, but chiefly owing to the bait held out by Western Powers, that extraterritoriality would be abolished when China had reformed her judicial system, a new Provisional Criminal Code was published. It substituted death by hanging or strangulation for decapitation, and imprisonment for various lengths of time for bambooing. It was adopted in large measure by the Republican régime, and is the chief legal Page 32instrument in use at the present time. But close examination reveals the fact that it is almost an exact copy of the Japanese penal code, which in turn was modelled upon that of Germany. It is, in fact, a Western code imitated, and as it stands is quite out of harmony with present conditions in China. It will have to be modified and recast to be a suitable, just, and practicable national legal instrument for the Chinese people. Moreover, it is frequently overridden in a high-handed manner by the police, who often keep a person acquitted by the Courts of Justice in custody until they have ‘squeezed’ him of all they can hope to get out of him. And it is noteworthy that, though provision was made in the Draft Code for trial by jury, this provision never went into effect; and the slavish imitation of alien methods is shown by the curiously inconsistent reason given—that “the fact that jury trials have been abolished in Japan is indicative of the inadvisability of transplanting this Western institution into China!”

Local Government

The central administration being a far-flung network of officialdom, there was hardly any room for local government apart from it. We find it only in the village elder and those associated with him, who took up what government was necessary where the jurisdiction of the unit of the central administration—the district magistracy—ceased, or at least did not concern itself in meddling much.

Military System

The peace-loving agricultural settlers in early China had at first no army. When occasion arose, all the Page 33farmers exchanged their ploughshares for swords and bows and arrows, and went forth to fight. In the intervals between the harvests, when the fields were clear, they held manoeuvres and practised the arts of warfare. The king, who had his Six Armies, under the Six High Nobles, forming the royal military force, led the troops in person, accompanied by the spirit-tablets of his ancestors and of the gods of the land and grain. Chariots, drawn by four horses and containing soldiers armed with spears and javelins and archers, were much in use. A thousand chariots was the regular force. Warriors wore buskins on their legs, and were sometimes gagged in order to prevent the alarm being given to the enemy. In action the chariots occupied the centre, the bowmen the left, the spearmen the right flank. Elephants were sometimes used in attack. Spy-kites, signal-flags, hook-ladders, horns, cymbals, drums, and beacon-fires were in use. The ears of the vanquished were taken to the king, quarter being rarely if ever given.

After the establishment of absolute monarchical government standing armies became the rule. Military science was taught, and soldiers sometimes trained for seven years. Chariots with upper storeys or spy-towers were used for fighting in narrow defiles, and hollow squares were formed of mixed chariots, infantry, and dragoons. The weakness of disunion of forces was well understood. In the sixth century A.D. the massed troops numbered about a million and a quarter. In A.D. 627 there was an efficient standing army of 900,000 men, the term of service being from the ages of twenty to sixty. During the Mongol dynasty (1280–1368) there was a navy of 5000 ships manned by 70,000 trained fighters. The Mongols completely revolutionized tactics and improved 34on all the military knowledge of the time. In 1614 the Manchu ‘Eight Banners,’ composed of Manchus, Mongolians, and Chinese, were instituted. The provincial forces, designated the Army of the Green Standard, were divided into land forces and marine forces, superseded on active service by ‘braves’ (yung), or irregulars, enlisted and discharged according to circumstances. After the war with Japan in 1894 reforms were seriously undertaken, with the result that the army has now been modernized in dress, weapons, tactics, etc., and is by no means a negligible quantity in the world’s fighting forces. A modern navy is also being acquired by building and purchase. For many centuries the soldier, being, like the priest, unproductive, was regarded with disdain, and now that his indispensableness for defensive purposes is recognized he has to fight not only any actual enemy who may attack him, but those far subtler forces from over the sea which seem likely to obtain supremacy in his military councils, if not actual control of his whole military system. It is, in my view, the duty of Western nations to take steps before it is too late to avert this great disaster.

Ecclesiastical Institutions

The dancing and chanting exorcists called wu were the first Chinese priests, with temples containing gods worshipped and sacrificed to, but there was no special sacerdotal class. Worship of Heaven could only be performed by the king or emperor. Ecclesiastical and political functions were not completely separated. The king was pontifex maximus, the nobles, statesmen, and civil and military officers acted as priests, the ranks being similar to those of the political hierarchy. Worship took place in the ‘Hall of Light,’ which was also a palace and 35audience and council chamber. Sacrifices were offered to Heaven, the hills and rivers, ancestors, and all the spirits. Dancing held a conspicuous place in worship. Idols are spoken of in the earliest times.

Of course, each religion, as it formed itself out of the original ancestor-worship, had its own sacred places, functionaries, observances, ceremonial. Thus, at the State worship of Heaven, Nature, etc., there were the ‘Great,’ ‘Medium,’ and ‘Inferior’ sacrifices, consisting of animals, silk, grain, jade, etc. Panegyrics were sung, and robes of appropriate colour worn. In spring, summer, autumn, and winter there were the seasonal sacrifices at the appropriate altars. Taoism and Buddhism had their temples, monasteries, priests, sacrifices, and ritual; and there were village and wayside temples and shrines to ancestors, the gods of thunder, rain, wind, grain, agriculture, and many others. Now encouraged, now tolerated, now persecuted, the ecclesiastical personnel and structure of Taoism and Buddhism survived into modern times, when we find complete schemes of ecclesiastical gradations of rank and authority grafted upon these two priestly hierarchies, and their temples, priests, etc., fulfilling generally, with worship of ancestors, State or official (Confucianism) and private or unofficial, and the observance of various annual festivals, such as ‘All Souls’ Day’ for wandering and hungry ghosts, the spiritual needs of the people as the ‘Three Religions’ (San Chiao). The emperor, as high priest, took the responsibility for calamities, etc., making confession to Heaven and praying that as a punishment the evil be diverted from the people to his own person. Statesmen, nobles, and officials discharged, as already noted, priestly functions in connexion with the State religion in addition to their ordinary Page 36duties. As a rule, priests proper, frowned upon as non-producers, were recruited from the lower classes, were celibate, unintellectual, idle, and immoral. There was nothing, even in the elaborate ceremonies on special occasions in the Buddhist temples, which could be likened to what is known as ‘public worship’ and ‘common prayer’ in the West. Worship had for its sole object either the attainment of some good or the prevention of some evil.

Generally this represents the state of things under the Republican régime; the chief differences being greater neglect of ecclesiastical matters and the conversion of a large number of temples into schools.

Professional Institutions

We read of physicians, blind musicians, poets, teachers, prayer-makers, architects, scribes, painters, diviners, ceremonialists, orators, and others during the Feudal Period, These professions were of ecclesiastical origin, not yet completely differentiated from the ‘Church,’ and both in earlier and later times not always or often differentiated from each other. Thus the historiographers combined the duties of statesmen, scholars, authors, and generals. The professions of authors and teachers, musicians and poets, were united in one person. And so it continued to the present day. Priests discharge medical functions, poets still sing their verses. But experienced medical specialists, though few, are to be found, as well as women doctors; there are veterinary surgeons, musicians (chiefly belonging to the poorest classes and often blind), actors, teachers, attorneys, diviners, artists, letter-writers, and many others, men of letters being perhaps the most prominent and most esteemed. 37

Accessory Institutions

A system of schools, academies, colleges, and universities obtained in villages, districts, departments, and principalities. The instruction was divided into ‘Primary Learning’ and ‘Great Learning.’ There were special schools of dancing and music. Libraries and almshouses for old men are mentioned. Associations of scholars for literary purposes seem to have been numerous.

Whatever form and direction education might have taken, it became stereotyped at an early age by the road to office being made to lead through a knowledge of the classical writings of the ancient sages. It became not only ‘the thing’ to be well versed in the sayings of Confucius, Mencius; etc., and to be able to compose good essays on them containing not a single wrongly written character, but useless for aspirants to office—who constituted practically the whole of the literary class—to acquire any other knowledge. So obsessed was the national mind by this literary mania that even infants’ spines were made to bend so as to produce when adult the ‘scholarly stoop.’ And from the fact that besides the scholar class the rest of the community consisted of agriculturists, artisans, and merchants, whose knowledge was that of their fathers and grandfathers, inculcated in the sons and grandsons as it had been in them, showing them how to carry on in the same groove the calling to which Fate had assigned them, a departure from which would have been considered ‘unfilial’—unless, of course (as it very rarely did), it went the length of attaining through study of the classics a place in the official class, and thus shedding eternal lustre on the family—it will readily be seen that there was nothing to cause education to be concerned with any but one or two of the subjects 38which are included by Western peoples under that designation. It became at an early age, and remained for many centuries, a rote-learning of the elementary text-books, followed by a similar acquisition by heart of the texts of the works of Confucius and other classical writers. And so it remained until the abolition, in 1905, of the old competitive examination system, and the substitution of all that is included in the term ‘modern education’ at schools, colleges, and universities all over the country, in which there is rapidly growing up a force that is regenerating the Chinese people, and will make itself felt throughout the whole world.

It is this keen and shrewd appreciation of the learned, and this lust for knowledge, which, barring the tragedy of foreign domination, will make China, in the truest and best sense of the word, a great nation, where, as in the United States of America, the rigid class status and undervaluation, if not disdaining, of knowledge which are proving so disastrous in England and other European countries will be avoided, and the aristocracy of learning established in its place.

Besides educational institutions, we find institutions for poor relief, hospitals, foundling hospitals, orphan asylums, banking, insurance, and loan associations, travellers’ clubs, mercantile corporations, anti-opium societies, co-operative burial societies, as well as many others, some imitated from Western models.

Bodily Mutilations

Compared with the practices found to exist among most primitive races, the mutilations the Chinese were in the habit of inflicting were but few. They flattened the skulls of their babies by means of stones, so as to 39cause them to taper at the top, and we have already seen what they did to their spines; also the mutilations in warfare, and the punishments inflicted both within and without the law; and how filial children and loyal wives mutilated themselves for the sake of their parents and to prevent remarriage. Eunuchs, of course, existed in great numbers. People bit, cut, or marked their arms to pledge oaths. But the practices which are more peculiarly associated with the Chinese are the compressing of women’s feet and the wearing of the queue, misnamed ‘pigtail.’ The former is known to have been in force about A.D. 934, though it may have been introduced as early as 583. It did not, however, become firmly established for more than a century. This ‘extremely painful mutilation,’ begun in infancy, illustrates the tyranny of fashion, for it is supposed to have arisen in the imitation by the women generally of the small feet of an imperial concubine admired by one of the emperors from ten to fifteen centuries ago (the books differ as to his identity). The second was a badge of servitude inflicted by the Manchus on the Chinese when they conquered China at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Discountenanced by governmental edicts, both of these practices are now tending toward extinction, though, of course, compressed feet and ‘pigtails’ are still to be seen in every town and village. Legally, the queue was abolished when the Chinese rid themselves of the Manchu yoke in 1912.

Funeral Rites

Not understanding the real nature of death, the Chinese believed it was merely a state of suspended animation, in which the soul had failed to return to the body, though Page 40it might yet do so, even after long intervals. Consequently they delayed burial, and fed the corpse, and went on to the house-tops and called aloud to the spirit to return. When at length they were convinced that the absent spirit could not be induced to re-enter the body, they placed the latter in a coffin and buried it—providing it, however, with all that it had found necessary in this life (food, clothing, wives, servants, etc.), which it would require also in the next (in their view rather a continuation of the present existence than the beginning of another)—and, having inducted or persuaded the spirit to enter the ‘soul-tablet’ which accompanied the funeral procession (which took place the moment the tablet was ‘dotted,’ i.e. when the character wang, ‘prince,’ was changed into chu, ‘lord’), carried it back home again, set it up in a shrine in the main hall, and fell down and worshipped it. Thus was the spirit propitiated, and as long as occasional offerings were not overlooked the power for evil possessed by it would not be exerted against the surviving inmates of the house, whom it had so thoughtlessly deserted.

The latter mourned by screaming, wailing, stamping their feet, and beating their breasts, renouncing (in the earliest times) even their clothes, dwelling, and belongings to the dead, removing to mourning-sheds of clay, fasting, or eating only rice gruel, sleeping on straw with a clod for a pillow, and speaking only on subjects of death and burial. Office and public duties were resigned, and marriage, music, and separation from the clan prohibited.

During the lapse of the long ages of monarchical rule funeral rites became more elaborate and magnificent, but, though less rigid and ceremonious since the institution of Page 41the Republic, they have retained their essential character down to the present day.

Funeral ceremonial was more exacting than that connected with most other observances, including those of marriage. Invitations or notifications were sent to friends, and after receipt of these fu, on the various days appointed therein, the guest was obliged to send presents, such as money, paper horses, slaves, etc., and go and join in the lamentations of the hired mourners and attend at the prayers recited by the priests. Funeral etiquette could not be pu’d, i.e. made good, if overlooked or neglected at the right time, as it could in the case of the marriage ceremonial.

Instead of symmetrical public graveyards, as in the West, the Chinese cemeteries belong to the family or clan of the deceased, and are generally beautiful and peaceful places planted with trees and surrounded by artistic walls enclosing the grave-mounds and monumental tablets. The cemeteries themselves are the metonyms of the villages, and the graves of the houses. In the north especially the grave is very often surmounted by a huge marble tortoise bearing the inscribed tablet, or what we call the gravestone, on its back. The tombs of the last two lines of emperors, the Ming and the Manchu, are magnificent structures, spread over enormous areas, and always artistically situated on hillsides facing natural or artificial lakes or seas. Contrary to the practice in Egypt, with the two exceptions above mentioned the conquering dynasties have always destroyed the tombs of their predecessors. But for this savage vandalism, China would probably possess the most magnificent assembly of imperial tombs in the world’s records. 42

Laws of Intercourse

Throughout the whole course of their existence as a social aggregate the Chinese have pushed ceremonial observances to an extreme limit. “Ceremonies,” says the Li chi, the great classic of ceremonial usages, “are the greatest of all things by which men live.” Ranks were distinguished by different headdresses, garments, badges, weapons, writing-tablets, number of attendants, carriages, horses, height of walls, etc. Daily as well as official life was regulated by minute observances. There were written codes embracing almost every attitude and act of inferiors toward superiors, of superiors toward inferiors, and of equals toward equals. Visits, forms of address, and giving of presents had each their set of formulae, known and observed by every one as strictly and regularly as each child in China learned by heart and repeated aloud the three-word sentences of the elementary Trimetrical Classic. But while the school text-book was extremely simple, ceremonial observances were extremely elaborate. A Chinese was in this respect as much a slave to the living as in his funeral rites he was a slave to the dead. Only now, in the rush of ‘modern progress,’ is the doffing of the hat taking the place of the ‘kowtow’ (k’o-t’ou).

It is in this matter of ceremonial observances that the East and the West have misunderstood each other perhaps more than in all others. Where rules of etiquette are not only different, but are diametrically opposed, there is every opportunity for misunderstanding, if not estrangement. The points at issue in such questions as ‘kowtowing’ to the emperor and the worshipping of ancestors are generally known, but the Westerner, as a rule, is ignorant of the fact that if he wishes to conform 43to Chinese etiquette when in China (instead of to those Western customs which are in many cases unfortunately taking their place) he should not, for instance, take off his hat when entering a house or a temple, should not shake hands with his host, nor, if he wishes to express approval, should he clap his hands. Clapping of hands in China (i.e. non-Europeanized China) is used to drive away the sha ch’i, or deathly influence of evil spirits, and to clap the hands at the close of the remarks of a Chinese host (as I have seen prominent, well-meaning, but ill-guided men of the West do) is equivalent to disapproval, if not insult. Had our diplomatists been sociologists instead of only commercial agents, more than one war might have been avoided.

Habits and Customs

At intervals during the year the Chinese make holiday. Their public festivals begin with the celebration of the advent of the new year. They let off innumerable firecrackers, and make much merriment in their homes, drinking and feasting, and visiting their friends for several days. Accounts are squared, houses cleaned, fresh paper ‘door-gods’ pasted on the front doors, strips of red paper with characters implying happiness, wealth, good fortune, longevity, etc., stuck on the doorposts or the lintel, tables, etc., covered with red cloth, and flowers and decorations displayed everywhere. Business is suspended, and the merriment, dressing in new clothes, feasting, visiting, offerings to gods and ancestors, and idling continue pretty consistently during the first half of the first moon, the vacation ending with the Feast of Lanterns, which occupies the last three days. It originated in the Han dynasty 2000 years ago. Innumerable 44lanterns of all sizes, shapes, colours (except wholly white, or rather undyed material, the colour of mourning), and designs are lit in front of public and private buildings, but the use of these was an addition about 800 years later, i.e. about 1200 years ago. Paper dragons, hundreds of yards long, are moved along the streets at a slow pace, supported on the heads of men whose legs only are visible, giving the impression of huge serpents winding through the thoroughfares.

Of the other chief festivals, about eight in number (not counting the festivals of the four seasons with their equinoxes and solstices), four are specially concerned with the propitiation of the spirits—namely, the Earlier Spirit Festival (fifteenth day of second moon), the Festival of the Tombs (about the third day of the third moon), when graves are put in order and special offerings made to the dead, the Middle Spirit Festival (fifteenth day of seventh moon), and the Later Spirit Festival (fifteenth day of tenth moon). The Dragon-boat Festival (fifth day of fifth moon) is said to have originated as a commemoration of the death of the poet Ch’ü Yüan, who drowned himself in disgust at the official intrigue and corruption of which he was the victim, but the object is the procuring of sufficient rain to ensure a good harvest. It is celebrated by racing with long narrow boats shaped to represent dragons and propelled by scores of rowers, pasting of charms on the doors of dwellings, and eating a special kind of rice-cake, with a liquor as a beverage.

The Spirit That Clears the Way

The fifteenth day of the eighth moon is the Mid-autumn Festival, known by foreigners as All Souls’ Day. On this occasion the women worship the moon, offering cakes, fruit, etc. The gates of Purgatory are opened, and the Page 45hungry ghosts troop forth to enjoy themselves for a month on the good things provided for them by the pious. The ninth day of the ninth moon is the Chung Yang Festival, when every one who possibly can ascends to a high place—a hill or temple-tower. This inaugurates the kite-flying season, and is supposed to promote longevity. During that season, which lasts several months, the Chinese people the sky with dragons, centipedes, frogs, butterflies, and hundreds of other cleverly devised creatures, which, by means of simple mechanisms worked by the wind, roll their eyes, make appropriate sounds, and move their paws, wings, tails, etc., in a most realistic manner. The festival originated in a warning received by a scholar named Huan Ching from his master Fei Ch’ang-fang, a native of Ju-nan in Honan, who lived during the Han dynasty, that a terrible calamity was about to happen, and enjoining him to escape with his family to a high place. On his return he found all his domestic animals dead, and was told that they had died instead of himself and his relatives. On New Year’s Eve (Tuan Nien or Chu Hsi) the Kitchen-god ascends to Heaven to make his annual report, the wise feasting him with honey and other sticky food before his departure, so that his lips may be sealed and he be unable to ‘let on’ too much to the powers that be in the regions above!

Sports and Games

The first sports of the Chinese were festival gatherings for purposes of archery, to which succeeded exercises partaking of a military character. Hunting was a favourite amusement. They played games of calculation, chess (or the ‘game of war’), shuttlecock with the feet, pitch-pot (throwing arrows from a distance into a narrow-necked Page 46jar), and ‘horn-goring’ (fighting on the shoulders of others with horned masks on their heads). Stilts, football, dice-throwing, boat-racing, dog-racing, cock-fighting, kite-flying, as well as singing and dancing marionettes, afforded recreation and amusement.

Many of these games became obsolete in course of time, and new ones were invented. At the end of the Monarchical Period, during the Manchu dynasty, we find those most in use to be foot-shuttlecock, lifting of beams headed with heavy stones—dumb-bells four feet long and weighing thirty or forty pounds—kite-flying, quail-fighting, cricket-fighting, sending birds after seeds thrown into the air, sauntering through fields, playing chess or ‘morra,’ or gambling with cards, dice, or over the cricket- and quail-fights or seed-catching birds. There were numerous and varied children’s games tending to develop strength, skill, quickness of action, parental instinct, accuracy, and sagacity. Theatricals were performed by strolling troupes on stages erected opposite temples, though permanent theatres also existed, female parts until recently being taken by male actors. Peep-shows, conjurers, ventriloquists, acrobats, fortune-tellers, and story-tellers kept crowds amused or interested. Generally, ‘young China’ of the present day, identified with the party of progress, seems to have adopted most of the outdoor but very few of the indoor games of Western nations.

Domestic Life

In domestic or private life, observances at birth, betrothal, and marriage were elaborate, and retained superstitious elements. Early rising was general. Shaving of the head and beard, as well as cleaning of the ears and massage, was done by barbers. There were public baths 47in all cities and towns. Shops were closed at nightfall, and, the streets being until recent times ill-lit or unlit, passengers or their attendants carried lanterns. Most houses, except the poorest, had private watchmen. Generally two meals a day were taken. Dinners to friends were served at inns or restaurants, accompanied or followed by musical or theatrical performances. The place of honour is stated in Western books on China to be on the left, but the fact is that the place of honour is the one which shows the utmost solicitude for the safety of the guest. It is therefore not necessarily one fixed place, but would usually be the one facing the door, so that the guest might be in a position to see an enemy enter, and take measures accordingly.

Lap-dogs and cage-birds were kept as pets; ‘wonks,’ the huang kou, or ‘yellow dog,’ were guards of houses and street scavengers. Aquaria with goldfish were often to be seen in the houses of the upper and middle classes, the gardens and courtyards of which usually contained rockeries and artistic shrubs and flowers.

Whiskers were never worn, and moustaches and beards only after forty, before which age the hair grew, if at all, very scantily. Full, thick beards, as in the West, were practically never seen, even on the aged. Snuff-bottles, tobacco-pipes, and fans were carried by both sexes. Nails were worn long by members of the literary and leisured classes. Non-Manchu women and girls had cramped feet, and both Manchu and Chinese women used cosmetics freely.

Industrial Institutions

While the men attended to farm-work, women took care of the mulberry-orchards and silkworms, and did 48spinning, weaving, and embroidery. This, the primitive division of labour, held throughout, though added to on both sides, so that eventually the men did most of the agriculture, arts, production, distribution, fighting, etc., and the women, besides the duties above named and some field-labour, mended old clothes, drilled and sharpened needles, pasted tin-foil, made shoes, and gathered and sorted the leaves of the tea-plant. In course of time trades became highly specialized—their number being legion—and localized, bankers, for instance, congregating in Shansi, carpenters in Chi Chou, and porcelain-manufacturers in Jao Chou, in Kiangsi.

As to land, it became at an early age the property of the sovereign, who farmed it out to his relatives or favourites. It was arranged on the ching, or ‘well’ system—eight private squares round a ninth public square cultivated by the eight farmer families in common for the benefit of the State. From the beginning to the end of the Monarchical Period tenure continued to be of the Crown, land being unallodial, and mostly held in clans or families, and not entailed, the conditions of tenure being payment of an annual tax, a fee for alienation, and money compensation for personal services to the Government, generally incorporated into the direct tax as scutage. Slavery, unknown in the earliest times, existed as a recognized institution during the whole of the Monarchical Period.

Production was chiefly confined to human and animal labour, machinery being only now in use on a large scale. Internal distribution was carried on from numerous centres and at fairs, shops, markets, etc. With few exceptions, the great trade-routes by land and sea have remained the same during the last two thousand years. 49Foreign trade was with Western Asia, Greece, Rome, Carthage, Arabia, etc., and from the seventeenth century A.D. more generally with European countries. The usual primitive means of conveyance, such as human beings, animals, carts, boats, etc., were partly displaced by steam-vessels from 1861 onward.

Exchange was effected by barter, cowries of different values being the prototype of coins, which were cast in greater or less quantity under each reign. But until within recent years there was only one coin, the copper cash, in use, bullion and paper notes being the other media of exchange. Silver Mexican dollars and subsidiary coins came into use with the advent of foreign commerce. Weights and measures (which generally decreased from north to south), officially arranged partly on the decimal system, were discarded by the people in ordinary commercial transactions for the more convenient duodecimal subdivision.

Arts

Hunting, fishing, cooking, weaving, dyeing, carpentry, metallurgy, glass-, brick-, and paper-making, printing, and book-binding were in a more or less primitive stage, the mechanical arts showing much servile imitation and simplicity in design; but pottery, carving, and lacquer-work were in an exceptionally high state of development, the articles produced being surpassed in quality and beauty by no others in the world.

Agriculture and Rearing of Livestock

From the earliest times the greater portion of the available land was under cultivation. Except when the country has been devastated by war, the Chinese have devoted 50close attention to the cultivation of the soil continuously for forty centuries. Even the hills are terraced for extra growing-room. But poverty and governmental inaction caused much to lie idle. There were two annual crops in the north, and five in two years in the south. Perhaps two-thirds of the population cultivated the soil. The methods, however, remained primitive; but the great fertility of the soil and the great industry of the farmer, with generous but careful use of fertilizers, enabled the vast territory to support an enormous population. Rice, wheat, barley, buckwheat, maize, kaoliang, several millets, and oats were the chief grains cultivated. Beans, peas, oil-bearing seeds (sesame, rape, etc.), fibre-plants (hemp, ramie, jute, cotton, etc.), starch-roots (taros, yams, sweet potatoes, etc.), tobacco, indigo, tea, sugar, fruits, were among the more important crops produced. Fruit-growing, however, lacked scientific method. The rotation of crops was not a usual practice, but grafting, pruning, dwarfing, enlarging, selecting, and varying species were well understood. Vegetable-culture had reached a high state of perfection, the smallest patches of land being made to bring forth abundantly. This is the more creditable inasmuch as most small farmers could not afford to purchase expensive foreign machinery, which, in many cases, would be too large or complicated for their purposes.

The principal animals, birds, etc., reared were the pig, ass, horse, mule, cow, sheep, goat, buffalo, yak, fowl, duck, goose, pigeon, silkworm, and bee.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce, the successor to the Board of Agriculture, Manufactures, and Commerce, instituted during recent years, is now adapting Western methods to the cultivation of the fertile soil of 51China, and even greater results than in the past may be expected in the future.

Sentiments and Moral Ideas

The Chinese have always shown a keen delight in the beautiful—in flowers, music, poetry, literature, embroidery, paintings, porcelain. They cultivated ornamental plants, almost every house, as we saw, having its garden, large or small, and tables were often decorated with flowers in vases or ornamental wire baskets or fruits or sweetmeats. Confucius made music an instrument of government. Paper bearing the written character was so respected that it might not be thrown on the ground or trodden on. Delight was always shown in beautiful scenery or tales of the marvellous. Commanding or agreeable situations were chosen for temples. But until within the last few years streets and houses were generally unclean, and decency in public frequently absent.

Morality was favoured by public opinion, but in spite of early marriages and concubinage there was much laxity. Cruelty both to human beings and animals has always been a marked trait in the Chinese character. Savagery in warfare, cannibalism, luxury, drunkenness, and corruption prevailed in the earliest times. The attitude toward women was despotic. But moral principles pervaded the classical writings, and formed the basis of law. In spite of these, the inferior sentiment of revenge was, as we have seen, approved and preached as a sacred duty. As a result of the universal yin-yang dualistic doctrines, immorality was leniently regarded. In modern times, at least, mercantile honour was high, “a merchant’s word is as good as his bond” being truer in China than in many Page 52other countries. Intemperance was rare. Opium-smoking was much indulged in until the use of the drug was forcibly suppressed (1906–16). Even now much is smuggled into the country, or its growth overlooked by bribed officials. Clan quarrels and fights were common, vendettas sometimes continuing for generations. Suicide under depressing circumstances was approved and honoured; it was frequently resorted to under the sting of great injustice. There was a deep reverence for parents and superiors. Disregard of the truth, when useful, was universal, and unattended by a sense of shame, even on detection. Thieving was common. The illegal exactions of rulers were burdensome. In times of prosperity pride and satisfaction in material matters was not concealed, and was often short-sighted. Politeness was practically universal, though said to be often superficial; but gratitude was a marked characteristic, and was heartfelt. Mutual conjugal affection was strong. The love of gambling was universal.

But little has occurred in recent years to modify the above characters. Nevertheless the inferior traits are certainly being changed by education and by the formation of societies whose members bind themselves against immorality, concubinage, gambling, drinking, smoking, etc.

Religious Ideas

Chinese religion is inherently an attitude toward the spirits or gods with the object of obtaining a benefit or averting a calamity. We shall deal with it more fully in another chapter. Suffice it to say here that it originated in ancestor-worship, and that the greater part of it remains ancestor-worship to the present day. The State religion, which was Confucianism, was ancestor-worship. Taoism, Page 53originally a philosophy, became a worship of spirits—of the souls of dead men supposed to have taken up their abode in animals, reptiles, insects, trees, stones, etc.—borrowed the cloak of religion from Buddhism, which eventually outshone it, and degenerated into a system of exorcism and magic. Buddhism, a religion originating in India, in which Buddha, once a man, is worshipped, in which no beings are known with greater power than can be attained to by man, and according to which at death the soul migrates into anything from a deified human being to an elephant, a bird, a plant, a wall, a broom, or any piece of inorganic matter, was imported ready made into China and took the side of popular superstition and Taoism against the orthodox belief, finding that its power lay in the influence on the popular mind of its doctrine respecting a future state, in contrast to the indifference of Confucianism. Its pleading for compassion and preservation of life met a crying need, and but for it the state of things in this respect would be worse than it is.

Religion, apart from ancestor-worship, does not enter largely into Chinese life. There is none of the real ‘love of God’ found, for example, in the fervent as distinguished from the conventional Christian. And as ancestor-worship gradually loses its hold and dies out agnosticism will take its place.

Superstitions

An almost infinite variety of superstitious practices, due to the belief in the good or evil influences of departed spirits, exists in all parts of China. Days are lucky or unlucky. Eclipses are due to a dragon trying to eat the sun or the moon. The rainbow is supposed to be the result of a meeting between the impure vapours of the 54sun and the earth. Amulets are worn, and charms hung up, sprigs of artemisia or of peach-blossom are placed near beds and over lintels respectively, children and adults are ‘locked to life’ by means of locks on chains or cords worn round the neck, old brass mirrors are supposed to cure insanity, figures of gourds, tigers’ claws, or the unicorn are worn to ensure good fortune or ward off sickness, fire, etc., spells of many kinds, composed mostly of the written characters for happiness and longevity, are worn, or written on paper, cloth, leaves, etc., and burned, the ashes being made into a decoction and drunk by the young or sick.

Divination by means of the divining stalks (the divining plant, milfoil or yarrow) and the tortoiseshell has been carried on from time immemorial, but was not originally practised with the object of ascertaining future events, but in order to decide doubts, much as lots are drawn or a coin tossed in the West. Fêng-shui, “the art of adapting the residence of the living and the dead so as to co-operate and harmonize with the local currents of the cosmic breath” (the yin and the yang: see Chapter III), a doctrine which had its root in ancestor-worship, has exercised an enormous influence on Chinese thought and life from the earliest times, and especially from those of Chu Hsi and other philosophers of the Sung dynasty.

Knowledge

Having noted that Chinese education was mainly literary, and why it was so, it is easy to see that there would be little or no demand for the kind of knowledge classified in the West under the head of science. In so far as any demand existed, it did so, at any rate at first, only because it subserved vital needs. Thus, astronomy, 55or more properly astrology, was studied in order that the calendar might be regulated, and so the routine of agriculture correctly followed, for on that depended the people’s daily rice, or rather, in the beginning, the various fruits and kinds of flesh which constituted their means of sustentation before their now universal food was known. In philosophy they have had two periods of great activity, the first beginning with Lao Tzŭ and Confucius in the sixth century B.C. and ending with the Burning of the Books by the First Emperor, Shih Huang Ti, in 213 B.C.; the second beginning with Chou Tzŭ (A.D. 1017–73) and ending with Chu Hsi (1130–1200). The department of philosophy in the imperial library contained in 190 B.C. 2705 volumes by 137 authors. There can be no doubt that this zeal for the orthodox learning, combined with the literary test for office, was the reason why scientific knowledge was prevented from developing; so much so, that after four thousand or more years of national life we find, during the Manchu Period, which ended the monarchical régime, few of the educated class, giants though they were in knowledge of all departments of their literature and history (the continuity of their traditions laid down in their twenty-four Dynastic Annals has been described as one of the great wonders of the world), with even the elementary scientific learning of a schoolboy in the West. ‘Crude,’ ‘primitive,’ ‘mediocre,’ ‘vague,’ ‘inaccurate,’ ‘want of analysis and generalization,’ are terms we find applied to their knowledge of such leading sciences as geography, mathematics, chemistry, botany, and geology. Their medicine was much hampered by superstition, and perhaps more so by such beliefs as that the seat of the intellect is in the stomach, that thoughts proceed from the heart, that the pit of the stomach is the seat of Page 56the breath, that the soul resides in the liver, etc.—the result partly of the idea that dissection of the body would maim it permanently during its existence in the Otherworld. What progress was made was due to European instruction; and this again is the causa causans of the great wave of progress in scientific and philosophical knowledge which is rolling over the whole country and will have marked effects on the history of the world during the coming century.

Language