|

|

By Abbie Farwell Brown

With Illustrations

By E. Boyd Smith

![]()

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

The Riverside Press, Cambridge

1903

Published October, 1903.

There are many books written nowadays which will tell you about birds as folk of the twentieth century see them. They describe carefully the singer's house, his habits, the number of his little wife's eggs, and the color of every tiny feather on her pretty wings. But these books tell you nothing at all about bird-history; about what birds have meant to all the generations of men, women, and children since the world began. You would think, to read the words of the bird-book men, that they were the very first folk to see any bird, and that what they think they have seen is the only matter worth the knowing.

Now the interesting facts about birds we have always with us. We can find them out for ourselves, which is a very pleasant thing to do, or we can take the word of others, of which there is no lack. But it is the quaint fancies about birds which are in danger of being lost. The long-time fancies which the world's children in all lands have been taught are quite as important as the every-day facts. They show what the little feathered brothers have been to the children of men; how we have come to like some and to dislike others as we do; why the poets have called them by certain nicknames which we ought to know; and why a great many strange things are so, in the minds of childlike people.

Facts are not what one looks for in a Curious Book. Yet it may be that some facts have crept in among the ancient fancies of this volume, just as bookworms will crawl into the nicest books; but they do not belong there, and it is for these that the Book apologizes to the children. It has no apology to offer those grown folks who insist that facts, never fancies, are what children need.

| PAGE | |

| The Disobedient Woodpecker | 1 |

| (French) | |

| Mother Magpie's Kindergarten | 6 |

| (Isle of Wight) | |

| The Gorgeous Goldfinch | 14 |

| (Roumanian) | |

| King of the Birds | 18 |

| (Gascon) | |

| Halcyone | 27 |

| (Greek) | |

| The Forgetful Kingfisher | 33 |

| (German) | |

| The Wren who brought Fire | 39 |

| (French) | |

| How the Bluebird crossed | 45 |

| (Samoan) | |

| The Peacock's Cousin | 49 |

| (Arabic, Malay) | |

| The Masquerading Crow | 59 |

| (Russian) | |

| King Solomon and the Birds | 69 |

| (Arabic) | |

| The Pious Robin | 81 |

| (Breton, Basque, Greek) | |

| The Robin who was an Indian | 87 |

| (Ojibway) | |

| The Inquisitive Woman | 94 |

| (Roumanian) | |

| Why the Nightingale wakes | 98 |

| (French) | |

| Mrs. Partridge's Babies | 105 |

| (Greek) | |

| The Early Girl | 109 |

| (Roumanian) | |

| How the Blackbird spoiled his Coat | 114 |

| (French) | |

| The Blackbird and the Fox | 124 |

| (French) | |

| The Dove who spoke Truth | 127 |

| (Welsh) | |

| The Fowls on Pilgrimage | 132 |

| (Greek) | |

| The Ground-Pigeon | 138 |

| (Malay) | |

| Sister Hen and the Crocodile | 145 |

| (Congo Negro) | |

| The Thrush and the Cuckoo | 153 |

| (Roumanian, German) | |

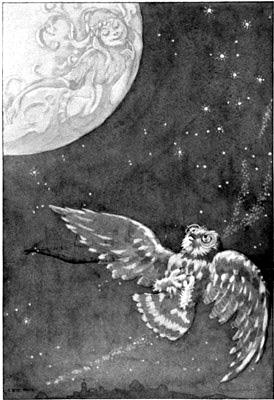

| The Owl and the Moon | 157 |

| (Malay) | |

| The Tufted Cap | 164 |

| (Ainu, Japanese Islands) | |

| The Good Hunter | 168 |

| (Iroquois) | |

| The Courtship of Mr. Stork and Miss Heron | 176 |

| (Russian) | |

| The Phœnix | 184 |

| (Egyptian) |

Seven of these tales appeared originally in The Churchman and two in The Congregationalist. They are reprinted by the courteous permission of the publishers of those magazines.

| "Not you alone, proud truths of the world, Not you alone, ye facts of modern science, But myths and fables of eld, Asia's, Africa's fables." |

| Whitman. |

ONG, long ago, at the beginning of things, they say

that the Lord made the world smooth and round like an apple.

There were no hills nor mountains: nor were there any hollows or

valleys to hold the seas and rivers, fountains and pools, which

the world of men would need. It must, indeed, have been a stupid

and ugly earth in those days, with no chance for swimming or

sailing, rowing or fishing. But as yet there was no one to think

anything about it, no one who would long to swim, sail, row, and

fish. For this was long before men were created.

ONG, long ago, at the beginning of things, they say

that the Lord made the world smooth and round like an apple.

There were no hills nor mountains: nor were there any hollows or

valleys to hold the seas and rivers, fountains and pools, which

the world of men would need. It must, indeed, have been a stupid

and ugly earth in those days, with no chance for swimming or

sailing, rowing or fishing. But as yet there was no one to think

anything about it, no one who would long to swim, sail, row, and

fish. For this was long before men were created.

The Lord looked about Him at the flocks of newly made birds, who were preening their wings and wondering at their own bright feathers, and said to Himself,—

"I will make these pretty creatures useful, from the very beginning, so that in after time men shall love them dearly. Come, my birds," He cried, "come hither to me, and with the beaks which I have given you hollow me out here, and here, and here, basins for the lakes and pools which I intend to fill with water for men and for you, their friends. Come, little brothers, busy yourselves as you would wish to be happy hereafter."

Then there was a twittering and fluttering as the good birds set to work with a will, singing happily over the work which their dear Lord had given them to do. They pecked and they pecked with their sharp little bills; they scratched and they scratched with their sharp little claws, till in the proper places they had hollowed out great basins and valleys and long river beds, and little holes in the ground.

Then the Lord sent great rains upon the earth until the hollows which the birds had made were filled with water, and so became rivers and lakes, little brooks and fountains, just as we see them to-day. Now it was a beautiful, beautiful world, and the good birds sang happily and rejoiced in the work which they had helped, and in the sparkling water which was sweet to their taste.

All were happy except one. The Woodpecker had taken no part with the other busy birds. She was a lazy, disobedient creature, and when she heard the Lord's commands she had only said, "Tut tut!" and sat still on the branch where she had perched, preening her pretty feathers and admiring her silver stockings. "You can toil if you want to," she said to the other birds who wondered at her, "but I shall do no such dirty work. My clothes are too fine."

Now when the world was quite finished and the beautiful water sparkled and glinted here and there, cool and refreshing, the Lord called the birds to Him and thanked them for their help, praising them for their industry and zeal. But to the Woodpecker He said,—

"As for you, O Woodpecker, I observe that your feathers are unruffled by work and that there is no spot of soil upon your beak and claws. How did you manage to keep so neat?"

The Woodpecker looked sulky and stood upon one leg.

"It is a good thing to be neat," said the Lord, "but not if it comes from shirking a duty. It is good to be dainty, but not from laziness. Have you not worked with your brothers as I commanded you?"

"It was such very dirty work," piped the Woodpecker crossly; "I was afraid of spoiling my pretty bright coat and my silver shining hose."

"Oh, vain and lazy bird!" said the Lord sadly. "Have you nothing to do but show off your fine clothes and give yourself airs? You are no more beautiful than many of your brothers, yet they all obeyed me willingly. Look at the snow-white Dove, and the gorgeous Bird of Paradise, and the pretty Grosbeak. They have worked nobly, yet their plumage is not injured. I fear that you must be punished for your disobedience, little Woodpecker. Henceforth you shall wear stockings of sooty black instead of the shining silver ones of which you are so proud. You who were too fine to dig in the earth shall ever be pecking at dusty wood. And as you declined to help in building the water-basins of the world, so you shall never sip from them when you are thirsty. Never shall you thrust beak into lake or river, little rippling brook or cool, sweet fountain. Raindrops falling scantily from the leaves shall be your drink, and your voice shall be heard only when other creatures are hiding themselves from the approaching storm."

It was a sad punishment for the Woodpecker, but she certainly deserved it. Ever since that time, whenever we hear a little tap-tapping in the tree city, we know that it is the poor Woodpecker digging at the dusty wood, as the Lord said she should do. And when we spy her, a dusty little body with black stockings, clinging upright to the tree trunk, we see that she is creeping, climbing, looking up eagerly toward the sky, longing for the rain to fall into her thirsty beak. She is always hoping for the storm to come, and plaintively pipes, "Plui-plui! Rain, O Rain!" until the drops begin to patter on the leaves.

ID you ever notice how different are the nests which the

birds build in springtime, in tree or bush or sandy bank or

hidden in the grass? Some are wonderfully wrought, pretty little

homes for birdikins. But others are clumsy, and carelessly

fastened to the bough, most unsafe cradles for the feathered baby

on the treetop. Sometimes after a heavy wind you find on the

ground under the nest poor little broken eggs which rolled out

and lost their chance of turning into birds with safe, safe wings

of their own. Now such sad things as this happen because in their

youth the lazy father and mother birds did not learn their lesson

when Mother Magpie had her class in nest-making. The clumsiest

nest of all is that which the Wood-Pigeon tries to build. Indeed,

it is not a nest at all, only the beginning of one. And there is

an old story about this, which I shall tell you.

ID you ever notice how different are the nests which the

birds build in springtime, in tree or bush or sandy bank or

hidden in the grass? Some are wonderfully wrought, pretty little

homes for birdikins. But others are clumsy, and carelessly

fastened to the bough, most unsafe cradles for the feathered baby

on the treetop. Sometimes after a heavy wind you find on the

ground under the nest poor little broken eggs which rolled out

and lost their chance of turning into birds with safe, safe wings

of their own. Now such sad things as this happen because in their

youth the lazy father and mother birds did not learn their lesson

when Mother Magpie had her class in nest-making. The clumsiest

nest of all is that which the Wood-Pigeon tries to build. Indeed,

it is not a nest at all, only the beginning of one. And there is

an old story about this, which I shall tell you.

In the early springtime of the world, when birds were first made, none of them—except Mother Magpie—knew how to build a nest. In that lovely garden where they lived the birds went fluttering about trying their new wings, so interested in this wonderful game of flying that they forgot all about preparing a home for the baby birds who were to come. When the time came to lay their eggs the parents knew not what to do. There was no place safe from the four-legged creatures who cannot fly, and they began to twitter helplessly: "Oh, how I wish I had a nice warm nest for my eggs!" "Oh, what shall we do for a home?" "Dear me! I don't know anything about housekeeping." And the poor silly things ruffled up their feathers and looked miserable as only a little bird can look when it is unhappy.

All except Mother Magpie! She was not the best—oh, no!—but she was the cleverest and wisest of all the birds; it seemed as if she knew everything that a bird could know. Already she had found out a way, and was busily building a famous nest for herself. She was indeed a clever bird! She gathered turf and sticks, and with clay bound them firmly together in a stout elm tree. About her house she built a fence of thorns to keep away the burglar birds who had already begun mischief among their peaceful neighbors. Thus she had a snug and cosy dwelling finished before the others even suspected what she was doing. She popped into her new house and sat there comfortably, peering out through the window-slits with her sharp little eyes. And she saw the other birds hopping about and twittering helplessly.

"What silly birds they are!" she croaked. "Ha, ha! What would they not give for a nest like mine!"

But presently a sharp-eyed Sparrow spied Mother Magpie sitting in her nest.

"Oho! Look there!" he cried. "Mother Magpie has found a way. Let us ask her to teach us."

Then all the other birds chirped eagerly, "Yes, yes! Let us ask her to teach us!"

So, in a great company, they came fluttering, hopping, twittering up to the elm tree where Mother Magpie nestled comfortably in her new house.

"O wise Mother Magpie, dear Mother Magpie," they cried, "teach us how to build our nests like yours, for it is growing night, and we are tired and sleepy."

The Magpie said she would teach them if they would be a patient, diligent, obedient class of little birds. And they all promised that they would.

She made them perch about her in a great circle, some on the lower branches of the trees, some on the bushes, and some on the ground among the grass and flowers. And where each bird perched, there it was to build its nest. Then Mother Magpie found clay and bits of twigs and moss and grass—everything a bird could need to build a nest; and there is scarcely anything you can think of which some bird would not find very useful. When these things were all piled up before her she told every bird to do just as she did. It was like a great big kindergarten of birds playing at a new building game, with Mother Magpie for the teacher.

She began to show them how to weave the bits of things together into nests, as they should be made. And some of the birds, who were attentive and careful, soon saw how it was done, and started nice homes for themselves. You have seen what wonderful swinging baskets the Oriole makes for his baby-cradle? Well, it was the Magpie who taught him how, and he was the prize pupil, to be sure. But some of the birds were not like him, nor like the patient little Wren. Some of them were lazy and stupid and envious of Mother Magpie's cosy nest, which was already finished, while theirs was yet to do.

As Mother Magpie worked, showing them how, it seemed so very simple that they were ashamed not to have discovered it for themselves. So, as she went on bit by bit, the silly things pretended that they had known all about it from the first—which was very unpleasant for their teacher.

Mother Magpie took two sticks in her beak and began like this: "First of all, my friends, you must lay two sticks crosswise for a foundation, thus," and she placed them carefully on the branch before her.

"Oh yes, oh yes!" croaked old Daddy Crow, interrupting her rudely. "I thought that was the way to begin."

Mother Magpie snapped her eyes at him and went on, "Next you must lay a feather on a bit of moss, to start the walls."

"Certainly, of course," screamed the Jackdaw. "I knew that came next. That is what I told the Parrot but a moment since."

Mother Magpie looked at him impatiently, but she did not say anything. "Then, my friends, you must place on your foundation moss, hair, feathers, sticks, and grass—whatever you choose for your house. You must place them like this."

"Yes, yes," cried the Starling, "sticks and grass, every one knows how to do that! Of course, of course! Tell us something new."

"Next you must lay a feather"

Now Mother Magpie was very angry, but she kept on with her lesson in spite of these rude and silly interruptions. She turned toward the Wood-Pigeon, who was a rattle-pated young thing, and who was not having any success with the sticks which she was trying to place.

"Here, Wood-Pigeon," said Mother Magpie, "you must place those sticks through and across, criss-cross, criss-cross, so."

"Criss-cross, criss-cross, so," interrupted the Wood-Pigeon. "I know. That will do-o-o, that will do-o-o!"

Mother Magpie hopped up and down on one leg, so angry she could hardly croak.

"You silly Pigeon," she sputtered, "not so. You are spoiling your nest. Place the sticks so!"

"I know, I know! That will do-o-o, that will do-o-o!" cooed the Wood-Pigeon obstinately in her soft, foolish little voice, without paying the least attention to Mother Magpie's directions.

"We all know that—anything more?" chirped the chorus of birds, trying to conceal how anxious they were to know what came next, for the nests were only half finished.

But Mother Magpie was thoroughly disgusted, and refused to go on with the lesson which had been so rudely interrupted by her pupils.

"You are all so wise, friends," she said, "that surely you do not need any help from me. You say you know all about it,—then go on and finish your nests by yourselves. Much luck may you have!" And away she flew to her own cosy nest in the elm tree, where she was soon fast asleep, forgetting all about the matter.

But oh! What a pickle the other birds were in! The lesson was but half finished, and most of them had not the slightest idea what to do next. That is why to this day many of the birds have never learned to build a perfect nest. Some do better than others, but none build like Mother Magpie.

But the Wood-Pigeon was in the worst case of them all. For she had only the foundation laid criss-cross as the Magpie had shown her. And so, if you find in the woods the most shiftless, silly kind of nest that you can imagine—just a platform of sticks laid flat across a branch, with no railing to keep the eggs from rolling out, no roof to keep the rain from soaking in—when you see that foolishness, you will know that it is the nest of little Mistress Wood-Pigeon, who was too stupid to learn the lesson which Mother Magpie was ready to teach.

And the queerest part of all is that the birds blamed the Magpie for the whole matter, and have never liked her since. But, as you may have found out for yourselves, that is often the fate of wise folk who make discoveries or who do things better than others.

HE Goldfinch who lives in Europe is one of the gaudiest of

the little feathered brothers. He is a very Joseph of birds in

his coat of many colors, and folk often wonder how he came to

have feathers so much more gorgeous than his kindred. But after

you have read this tale you will wonder no longer.

HE Goldfinch who lives in Europe is one of the gaudiest of

the little feathered brothers. He is a very Joseph of birds in

his coat of many colors, and folk often wonder how he came to

have feathers so much more gorgeous than his kindred. But after

you have read this tale you will wonder no longer.

You must know that when the Father first made all the birds they were dressed alike in plumage of sober gray. But this dull uniform pleased Him no more than it did the birds themselves, who begged that they might wear each the particular style which was most becoming, and by which they could be recognized afar.

So the Father called the birds to Him, one by one, as they stood in line, and dipping His brush in the rainbow color-box painted each appropriately in the colors which it wears to-day. (Except, indeed, that some had later adventures which altered their original hues, as you shall hear in due season.)

But the Goldfinch did not come with the other birds. That tardy little fellow was busy elsewhere on his own affairs and heeded not the Father's command to fall in line and wait his turn for being made beautiful.

So it happened that not until the painting was finished and all the birds had flown away to admire themselves in the water-mirrors of the earth, did the Goldfinch present himself at the Father's feet out of breath.

"O Father!" he panted, "I am late. But I was so busy! Pray forgive me and permit me to have a pretty coat like the others."

"You are late indeed," said the Father reproachfully, "and all the coloring has been done. You should have come when I bade you. Do you not know that it is the prompt bird who fares best? My rainbow color-box has been generously used, and I have but little of each tint left. Yet I will paint you with the colors that I have, and if the result be ill you have only yourself to blame."

The Father smiled gently as He took up the brush which He had laid down, and dipped it in the first color which came to hand. This He used until there was no more, when He began with another shade, and so continued until the Goldfinch was completely colored from head to foot. Such a gorgeous coat! His forehead and throat were of the most brilliant crimson. His cap and sailor collar were black. His back was brown and yellow, his breast white, his wings golden set off with velvet black, and his tail was black with white-tipped feathers. Certainly there was no danger of his being mistaken for any other bird.

When the Goldfinch looked down into a pool and saw the reflection of his gorgeous coat, he burst out into a song of joy. "I like it, oh, I like it!" he warbled, and his song was very sweet. "Oh, I am glad that I was late, indeed I am, dear Father!"

But the kind Father sighed and shook His head as He put away the brush, exclaiming, "Poor little Goldfinch! You are indeed a beautiful bird. But I fear that the gorgeous coat which you wear, and which is the best that I could give you, because you came so late, will cause you more sorrow than joy. Because of it you will be chased and captured and kept in captivity; and your life will be spent in mourning for the days when you were a plain gray bird."

And so it happened. For to this day the Goldfinch is persecuted by human folk who admire his wonderful plumage and his beautiful song. He is kept captive in a cage, while his less gorgeous brothers fly freely in the beautiful world out of doors.

Such a gorgeous coat!

NCE upon a time, when the world was very new and when the

birds had just learned from Mother Magpie how to build their

nests, some one said, "We ought to have a king. Oh, we need a

king of the birds very much!"

NCE upon a time, when the world was very new and when the

birds had just learned from Mother Magpie how to build their

nests, some one said, "We ought to have a king. Oh, we need a

king of the birds very much!"

For you see, already in the Garden of Birds trouble had begun. There were disputes every morning as to which was the earliest bird who was entitled to the worm. There were quarrels over the best places for nest-building and over the fattest bug or beetle; and there was no one to settle these difficulties. Moreover, the robber birds were growing too bold, and there was no one to rule and punish them. There was no doubt about it; the birds needed a king to keep them in order and peace.

So the whisper went about, "We must have a king. Whom shall we choose for our king?"

They decided to hold a great meeting for the election. And because the especial talent of a bird is for flying, they agreed that the bird who could fly highest up into the blue sky, straight toward the sun, should be their king, king of all the feathered tribes of the air.

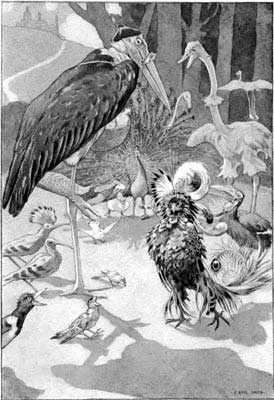

Therefore, after breakfast one beautiful morning, the birds met in the garden to choose their king. All the birds were there, from the largest to the smallest, chirping, twittering, singing on every bush and tree and bit of dry grass, till the noise was almost as great as nowadays at an election of two-legged folk without feathers. They swooped down in great clouds, till the sky was black with them, and they were dotted on the grass like punctuation marks on a green page. There were so many that not even wise Mother Magpie or old Master Owl could count them, and they all talked at the same time, like ladies at an afternoon tea, which was very confusing.

Little Robin Redbreast was there, hopping about and saying pleasant things to every one, for he was a great favorite. Gorgeous Goldfinch was there, in fine feather; and little Blackbird, who was then as white as snow. There were the proud Peacock and the silly Ostrich, the awkward Penguin and the Dodo, whom no man living has ever seen. Likewise there were the Jubjub Bird and the Dinky Bird, and many other curious varieties that one never finds described in the wise Bird Books,—which is very strange, and sad, too, I think. Yes, all the birds were there for the choosing of their king, both the birds who could fly, and those who could not. (But for what were they given wings, if not to fly? How silly an Ostrich must feel!)

Now the Eagle expected to be king. He felt sure that he could fly higher than any one else. He sat apart on a tall pine tree, looking very dignified and noble, as a future king should look. And the birds glanced at one another, nodded their heads, and whispered, "He is sure to be elected king. He can fly straight up toward the sun without winking, and his great wings are so strong, so strong! He never grows tired. He is sure to be king."

Thus they whispered among themselves, and the Eagle heard them, and was pleased. But the little brown Wren heard also, and he was not pleased. The absurd little bird! He wanted to be king himself, although he was one of the tiniest birds there, who could never be a protector to the others, nor stop trouble when it began. No, indeed! Fancy him stepping as a peacemaker between a robber Hawk and a bloody Falcon. It was they who would make pieces of him. But he was a conceited little creature, and saw no reason why he should not make a noble sovereign.

"I am cleverer than the Eagle," he said to himself, "though he is so much bigger. I will be king in spite of him. Ha-ha! We shall see what we shall see!" For the Wren had a great idea in his wee little head—an idea bigger than the head itself, if you can explain how that could be. He ruffled up his feathers to make himself as huge as possible, and hopped over to the branch where the Eagle was sitting.

"Well, Eagle," said the Wren pompously, "I suppose you expect to be king, eh?"

The Eagle stared hard at him with his great bright eyes. "Well, if I do, what of that?" he said. "Who will dispute me?"

"I shall," said the Wren, bobbing his little brown head and wriggling his tail saucily.

"You!" said the Eagle. "Do you expect to fly higher than I?"

"Yes," chirped the Wren, "I do. Yes, I do, do, do!"

"Ho!" said the Eagle scornfully. "I am big and strong and brave. I can fly higher than the clouds. You, poor little thing, are no bigger than a bean. You will be out of breath before we have gone twice this tree's height."

"Little as I am, I can mount higher than you," said the Wren.

"What will you wager, Wren?" asked the Eagle. "What will you give me if I win?"

"If you win you will be king," said the Wren. "But beside that, if you win I will give you my fat little body to eat for your breakfast. But if I win, Sir, I shall be king, and you must promise never, never, never, to hurt me or any of my people."

"Very well. I promise," said the Eagle haughtily. "Come now, it is time for the trial, you poor little foolish creature."

The birds were flapping their wings and singing eagerly, "Let us begin—begin. We want to see who is to be king. Come, birds, to the trial. Who can fly the highest? Come!"

Then the Eagle spread his great wings and mounted leisurely into the air, straight toward the noonday sun. And after him rose a number of other birds who wanted to be king,—the wicked Hawk, the bold Albatross, and the Skylark singing his wonderful song. The long-legged Stork started also, but that was only for a joke. "Fancy me for a king!" he cried, and he laughed so that he had to come down again in a minute. But the Wren was nowhere to be seen. The truth was, he had hopped ever so lightly upon the Eagle's head, where he sat like a tiny crest. But the Eagle did not know he was there.

Soon the Hawk and the Albatross and even the brave little Skylark fell behind, and the Eagle began to chuckle to himself at his easy victory. "Where are you, poor little Wren?" he cried very loudly, for he fancied that the tiny bird must be left far, far below.

"Here I am, here I am, away up above you, Master Eagle!" piped the Wren in a weak little voice. And the Eagle fancied the Wren was so far up in the air that even his sharp eyes could not spy the tiny creature. "Dear me!" said he to himself. "How extraordinary that he has passed me." So he redoubled his speed and flew on, higher, higher.

Presently he called out again in a tremendous voice, "Well, where are you now? Where are you now, poor little Wren?"

Once more he heard the tiny shrill voice from somewhere above piping, "Here I am, here I am, nearer the sun than you, Master Eagle. Will you give up now?"

Of course the Eagle would not give up yet. He flew on, higher and higher, till the garden and its flock of patient birds waiting for their king grew dim and blurry below. And at last even the mighty wings of the Eagle were weary, for he was far above the clouds. "Surely," he thought, "now the Wren is left miles behind." He gave a scream of triumph and cried, "Where are you now, poor little Wren? Can you hear me at all, down below there?"

But what was his amazement to hear the same little voice above his head shrilling, "Here I am, here I am, Sir Eagle. Look up and see me, look!" And there, sure enough, he was fluttering above the Eagle's head. "And now, since I have mounted so much higher than you, will you agree that I have won?"

"Yes, you have won, little Wren. Let us descend together, for I am weary enough," cried the Eagle, much mortified; and down he swooped, on heavy, discouraged wings.

"Yes, let us descend together," murmured the Wren, once more perching comfortably on the Eagle's head. And so down he rode on this convenient elevator, which was the first one invented in this world.

When the Eagle nearly reached the ground, the other birds set up a cry of greeting.

"Hail, King Eagle!" they sang. "How high you flew! How near the sun! Did he not scorch your Majesty's feathers? Hail, mighty king!" and they made a deafening chorus. But the Eagle stopped them.

"The Wren is your king, not I," he said. "He mounted higher than I did."

"The Wren? Ha-ha! The Wren! We can't believe that The Wren flew higher than you? No, no!" they all shouted. But just then the Eagle lighted on a tree, and from the top of his head hopped the little Wren, cocking his head and ruffling himself proudly.

"Yes, I mounted higher than he," he cried, "for I was perched on his head all the while, ha-ha! And now, therefore, I am king, small though I be."

Now the Eagle was very angry when he saw the trick that had been played upon him, and he swooped upon the sly Wren to punish him. But the Wren screamed, "Remember, remember your promise never to injure me or mine!" Then the Eagle stopped, for he was a noble bird and never forgot a promise. He folded his wings and turned away in disgust.

"Be king, then, O cheat and trickster!" he said.

"Cheat and trickster!" echoed the other birds. "We will have no such fellow for our king. Cheat and trickster he is, and he shall be punished. You shall be king, brave Eagle, for without your strength he could never have flown so high. It is you whom we want for our protector and lawmaker, not this sly fellow no bigger than a bean."

So the Eagle became their king, after all; and a noble bird he is, as you must understand, or he would never have been chosen to guard our nation's coat of arms. And besides this you may see his picture on many a banner and crest and coin of gold or silver, so famous has he become.

But the Wren was to be punished. And while the birds were trying to decide what should be done with him, they put him in prison in a mouse-hole and set Master Owl to guard the door. Now while the judges were putting their heads together the lazy Owl fell fast asleep, and out of prison stole the little Wren and was far away before any one could catch him. So he was never punished after all, as he richly deserved to be.

The birds were so angry with old Master Owl for his carelessness that he has never since dared to show his face abroad in daytime, but hides away in his hollow tree. And only at night he wanders alone in the woods, sorry and ashamed.

HE story of the first Kingfisher is a sad one, and you need

not read it unless for a very little while you wish to feel

sorry.

HE story of the first Kingfisher is a sad one, and you need

not read it unless for a very little while you wish to feel

sorry.

Long, long ago when the world was new, there lived a beautiful princess named Halcyone. She was the daughter of old Æolus, King of the Winds, and lived with him on his happy island, where it was his chief business to keep in order the four boisterous brothers, Boreas, the North Wind, Zephyrus, the West Wind, Auster, the South Wind, and Eurus, the East Wind. Sometimes, indeed, Æolus had a hard time of it; for the Winds would escape from his control and rush out upon the sea for their terrible games, which were sure to bring death and destruction to the sailors and their ships. Knowing them so well, for she had grown up with these rough playmates, Halcyone came to dread more than anything else the cruelties which they practiced at every opportunity.

One day the Prince Ceyx came to the island of King Æolus. He was the son of Hesperus, the Evening Star, and he was the king of the great land of Thessaly. Ceyx and Halcyone grew to love each other dearly, and at last with the consent of good King Æolus, but to the wrath of the four Winds, the beautiful princess went away to be the wife of Ceyx and Queen of Thessaly.

For a long time they lived happily in their peaceful kingdom, but finally came a day when Ceyx must take a long voyage on the sea, to visit a temple in a far country. Halcyone could not bear to have him go, for she feared the dangers of the great deep, knowing well the cruelty of the Winds, whom King Æolus had such difficulty in keeping within bounds. She knew how the mischievous brothers loved to rush down upon venturesome sailors and blow them into danger, and she knew that they especially hated her husband because he had carried her away from the island where she had watched the Winds at their terrible play. She begged Ceyx not to go, but he said that it was necessary. Then she prayed that if he must go he would take her with him, for she could not bear to remain behind dreading what might happen.

But Ceyx was resolved that Halcyone should not go. The good king longed to take her with him; no more than she could he smile at the thought of separation. But he also feared the sea, not on his own account, but for his dear wife. In spite of her entreaties he remained firm. If all went well he promised to return in two months' time. But Halcyone knew that she should never see him again as now he spoke.

The day of separation came. Standing heart-broken upon the shore, Halcyone watched the vessel sail away into the East, until as a little speck it dropped below the horizon; then sobbing bitterly she returned to the palace.

Now the king and his men had completed but half their journey when a terrible storm arose. The wicked Winds had escaped from the control of good old Æolus and were rushing down upon the ocean to punish Ceyx for carrying away the beautiful Halcyone. Fiercely they blew, the lightning flashed, and the sea ran high; and in the midst of the horrible tumult the good ship went to the bottom with all on board. Thus the fears of Halcyone were proved true, and far from his dear wife poor Ceyx perished in the cruel waves.

That very night when the shipwreck occurred, the sad and fearful Halcyone, sleeping lonely at home, knew in a dream the very calamity which had happened. She seemed to see the storm and the shipwreck, and the form of Ceyx appeared, saying a sad farewell to her. As soon as it was light she rose and hastened to the seashore, trembling with a horrible dread. Standing on the very spot whence she had last seen the fated ship, she looked wistfully over the waste of stormy waters. At last she spied a dark something tossing on the waves. The object floated nearer and nearer, until a huge breaker cast before her on the sand the body of her drowned husband.

"O dearest Ceyx!" she cried. "Is it thus that you return to me?" Stretching out her arms toward him, she leaped upon the sea wall as if she would throw herself into the ocean, which advanced and retreated, seething around his body. But a different fate was to be hers. As she leaped forward two strong wings sprouted from her shoulders, and before she knew it she found herself skimming lightly as a bird over the water. From her throat came sounds of sobbing, which changed as she flew into the shrill piping of a bird. Soft feathers now covered her body, and a crest rose above the forehead which had once been so fair. Halcyone was become a Kingfisher, the first Kingfisher who ever flew lamenting above the waters of the world.

The sad bird fluttered through the spray straight to the body that was tossed upon the surf. As her wings touched the wet shoulders, and as her horny beak sought the dumb lips in an attempt to kiss what was once so dear, the body of Ceyx began to receive new life. The limbs stirred, a faint color returned to the cheeks. At the same moment a change like that which had transformed Halcyone began to pass over her husband. He too was becoming a Kingfisher. He too felt the thrill of wings upon his shoulders, wings which were to bear him up and away out of the sea which had been his death. He too was clad in soft plumage with a kingly crest upon his kingly head. With a faint cry, half of sorrow for what had happened, half of joy for the future in which these two loving ones were at least to be together, Ceyx rose from the surf-swept sand where his lifeless limbs had lain and went skimming over the waves beside Halcyone his wife.

So those unhappy mortals became the first kingfishers, happy at last in being reunited. So we see them still, flying up and down over the waters of the world, royal forms with royal crests upon their heads.

They built their nest of the bones of fish, a stout and well-joined basket which floated on the waves as safely as any little boat. And while their children, the baby Halcyons, lay in this rocking cradle, for seven days in the heart of winter, no storms ever troubled the ocean and mariners could set out upon their voyages without fear.

For while his little grandchildren rocked in their basket, the good King Æolus, pitying the sorrows of his daughter Halcyone, was always especially careful to chain up in prison those wicked brothers the Winds, so that they could do no mischief of any kind.

And that is why a halcyon time has come to mean a season of peace and safety.

N these days the Kingfisher is a sad and solitary bird,

caring not to venture far from the water where she finds her

food. Up and down the river banks she goes, uttering a peculiar

plaintive cry. What is she saying, and why is she so restless?

The American Kingfisher is gray, but her cousin of Europe is a

bird of brilliant azure with a breast of rusty red. Therefore it

must have been the foreign Kingfisher who was forgetful, as you

shall hear.

N these days the Kingfisher is a sad and solitary bird,

caring not to venture far from the water where she finds her

food. Up and down the river banks she goes, uttering a peculiar

plaintive cry. What is she saying, and why is she so restless?

The American Kingfisher is gray, but her cousin of Europe is a

bird of brilliant azure with a breast of rusty red. Therefore it

must have been the foreign Kingfisher who was forgetful, as you

shall hear.

Long, long after the sorrows of Halcyone, the first Kingfisher, were ended, came the great storm which lasted forty days and forty nights, causing the worst flood which the world has ever known. That was a terrible time. When Father Noah hastened to build his ark, inviting the animals and birds to take refuge with him, the Kingfisher herself was glad to go aboard. For even she, protected by Æolus from the fury of winds and waters, was not safe while there was no place in all the world for her to rest foot and weary wing. So the Kingfisher fluttered in with the other birds and animals, a strange company! And there they lived all together, Noah and his arkful of pets, for many weary days, while the waters raged and the winds howled outside, and all the earth was covered fathoms deep out of sight below the waves.

But after long weeks the storm ceased, and Father Noah opened the little window in the ark and sent forth the Dove to see whether or not there was land visible on which the ark might find rest. Now after he had sent out the Dove, Noah looked about him at the other birds and animals which crowded around him eagerly, for they were growing very restless from their long confinement, and he said, "Which of you is bravest, and will dare follow our friend the Dove out into the watery world? Ah, here is the Kingfisher. Little mother, you at least, reared among the winds and waters, will not be afraid. Take wing, O Kingfisher, and see if the earth be visible. Then return quickly and bring me faithful word of what you find out yonder."

Day was just beginning to dawn when the Kingfisher, who was then as gray as gray, flew out from the little window of the ark whence the Dove had preceded her. But hardly had she left the safe shelter of Father Noah's floating home, when there came a tremendous whirlwind which blew her about and buffeted her until she was almost beaten into the waves, which rolled endlessly over the face of the whole earth, covering the high hills and the very mountains. The Kingfisher was greatly frightened. She could not go back into the ark, for the little window was closed, and there was no land anywhere on which she could take refuge. Just think for a moment what a dreadful situation it was! There was nothing for her to do but to fly up, straight up, out of reach from the tossing waves and dashing spray.

The Kingfisher was fresh and vigorous, and her wings were strong and powerful, for she had been resting long days in the quiet ark, eating the provisions which Father Noah had thoughtfully prepared for his many guests. So up, up she soared, above the very clouds, on into the blue ether which lies beyond. And lo! as she did so, her sober gray dress became a brilliant blue, the color caught from the azure of those clear heights. Higher and higher she flew, feeling so free and happy after her long captivity, that she quite forgot Father Noah and the errand upon which she had been sent. Up and up she went, higher than the sun, until at last she saw him rising far beneath her, a beautiful ball of fire, more dazzling, more wonderful than she had ever guessed.

"Hola!" she cried, beside herself with joy at the sight. "There is the dear sun, whom I have not seen for many days. And how near, how beautiful he is! I will fly closer still, now that I have come so near. I will observe him in all his splendor, as no other bird, not even the high-flying, sharp-eyed Eagle, has ever seen him."

And with that the foolish Kingfisher turned her course downward, with such mad, headlong speed that she had scarcely time to feel what terrible, increasing heat shot from the sun's rays, until she was so close upon him that it was too late to escape. Oh, but that was a dreadful moment! The feathers on her poor little breast were scorched and set afire, and she seemed in danger not only of spoiling her beautiful new blue dress but of being burned into a wretched little cinder. Horribly frightened at her danger, the Kingfisher turned once more, but this time toward the rolling waters which covered the earth. Down, down she swooped, until with the hiss of burning feathers she splashed into the cold wetness, putting out the fire which threatened to consume her. Once, twice, thrice, she dipped into the grateful coolness, flirting the drops from her blue plumage, now alas! sadly scorched.

When the pain of her burns was somewhat relieved she had time to think what next she should do. She longed for rest, for refuge, for Father Noah's gentle, caressing hand to which she had grown accustomed during those stormy weeks of companionship in the ark. But where was Father Noah? Where was the ark? On all the rolling sea of water there was no movement of life, no sign of any human presence. Then the Kingfisher remembered her errand, and how carelessly she had performed it. She had been bidden to return quickly; but she had wasted many hours—she could not tell how many—in her forgetful flight. And now she was to be punished indeed, if she could not find her master and the ark of refuge.

The poor Kingfisher looked wildly about. She fluttered here and there, backward and forward, over the weary stretch of waves, crying piteously for her master. He did not answer; there was no ark to be found. The sun set and the night came on, but still she sought eagerly from east to west, from north to south, always in vain. She could never find what she had so carelessly lost.

The truth is that during her absence the Dove, who had done her errand faithfully, returned at last with the olive leaf which told of one spot upon the earth's surface at last uncovered by the waves. Then the ark, blown hither and thither by the same storm which had driven the Kingfisher to fly upward into the ether-blue, had drifted far and far to Mount Ararat, where it ran aground. And Father Noah, disembarking with his family and all the assembled animals, had broken up the ark, intending there to build him a house out of the materials from which it was made. But this was many, many leagues from the place where the poor Kingfisher, lonely and frightened, hovered about, crying piteously for her master.

And even when the waters dried away, uncovering the earth in many places, so that the Kingfisher could alight and build herself a nest, she was never happy nor content, but to this day flies up and down the water-ways of the world piping sadly, looking eagerly for her dear master and for some traces of the ark which sheltered her. And the reflection which she makes in the water below shows an azure-blue body, like a reflection of the sky above, with some of the breast-feathers scorched to a rusty red. And now you know how it all came about.

ENTURIES and centuries ago, when men were first made, there

was no such thing as fire known in all the world. Folk had no

fire with which to cook their food, and so they were obliged to

eat it raw; which was very unpleasant, as you may imagine! There

were no cheery fireplaces about which to sit and tell stories, or

make candy or pop corn. There was no light in the darkness at

night except the sun and moon and stars. There were not even

candles in those days, to say nothing of gas lamps or electric

lights. It is strange to think of such a world where even the

grown folks, like the children and the birds, had to go to bed at

dusk, because there was nothing else to do.

ENTURIES and centuries ago, when men were first made, there

was no such thing as fire known in all the world. Folk had no

fire with which to cook their food, and so they were obliged to

eat it raw; which was very unpleasant, as you may imagine! There

were no cheery fireplaces about which to sit and tell stories, or

make candy or pop corn. There was no light in the darkness at

night except the sun and moon and stars. There were not even

candles in those days, to say nothing of gas lamps or electric

lights. It is strange to think of such a world where even the

grown folks, like the children and the birds, had to go to bed at

dusk, because there was nothing else to do.

But the little birds, who lived nearer heaven than men, knew of the fire in the sun, and knew also what a fine thing it would be for the tribes without feathers if they could have some of the magic element.

One day the birds held a solemn meeting, when it was decided that men must have fire. Then some one must fly up to the sun and bring a firebrand thence. Who would undertake this dangerous errand? Already by sad experience the Kingfisher had felt the force of the sun's heat, while the Eagle and the Wren, in the famous flight which they had taken together, had learned the same thing. The assembly of birds looked at one another, and there was a silence.

"I dare not go," said the Kingfisher, trembling at the idea; "I have been up there once, and the warning I received was enough to last me for some time."

"I cannot go," said the Peacock, "for my plumage is too precious to risk."

"I ought not to go," said the Lark, "for the heat might injure my pretty voice."

"I must not go," said the Stork, "for I have promised to bring a baby to the King's palace this evening."

"I cannot go," said the Dove, "for I have a nestful of little ones who depend upon me for food."

"Nor I," said the Sparrow, "for I am afraid." "Nor I!" "Nor I!" "Nor I!" echoed the other birds.

"I will not go," croaked the Owl, "for I simply do not wish to."

Then up spoke the little Wren, who had been keeping in the background of late, because he was despised for his attempt to deceive the birds into electing him their king.

"I will go," said the Wren. "I will go and bring fire to men. I am of little use here. No one loves me. Every one despises me because of the trick which I played the Eagle, our King. No one will care if I am injured in the attempt. I will go and try."

"Bravely spoken, little friend," said the Eagle kindly. "I myself would go but that I am the King, and kings must not risk the lives upon which hangs the welfare of their people. Go you, little Wren, and if you are successful you will win back the respect of your brothers which you have forfeited."

The brave little bird set out upon his errand without further words. And weak and delicate though he was, he flew and he flew up and up so sturdily that at last he reached the sun, whence he plucked a firebrand and bore it swiftly in his beak back toward the earth. Like a falling star the bright speck flashed through the air, drawing ever nearer and nearer to the cool waters of Birdland and the safety which awaited him there. The other birds gathered in a flock about their king and anxiously watched the Wren's approach.

Suddenly the Robin cried out, "Alas! He burns! He has caught fire!" And off darted the faithful little friend to help the Wren. Sure enough, a spark from the blazing brand had fallen upon the plumage of the Wren, and his poor little wings were burning as he fluttered piteously down, still holding the fire in his beak.

The Robin flew up to him and said, "Well done, brother! You have succeeded. Now give me the fire and I will relieve you while you drop into the lake below us to quench the flame which threatens your life."

So the Robin in his turn seized the firebrand in his beak and started down with it. But, like the Wren, he too was soon fluttering in the blaze of his own burning plumage, a little living firework, falling toward the earth.

Then up came the Lark, who had been watching the two unselfish birds. "Give me the brand, brother Robin," she cried, "for your pretty feathers are all ablaze and your life is in danger."

So it was the Lark who finally brought the fire safely to the earth and gave it to mankind. But the Robin and the Wren, when they had put out the flame which burned their feathers, appeared in the assembly of the birds, and were greeted with great applause as the heroes of the day. The Robin's breast was scorched a brilliant red, but the poor, brave little Wren was wholly bare of plumage. All his pretty feathers had been burned away, and he stood before them shivering and piteous.

"Bravo! little Wren," cried King Eagle. "A noble deed you have done this day, and nobly have you won back the respect of your brother birds and earned the everlasting gratitude of men. Now what shall we do to help you in your sorry plight?" After a moment's thought he turned to the other birds and said, "Who will give a feather to help patch a covering for our brave friend?"

"I!" and "I!" and "I!" and "I!" chorused the generous birds. And in turn each came forward with a plume or a bit of down from his breast. The Robin first, who had shared his peril, brought a feather sadly scorched, but precious; the Lark next, who had helped in the time of need. The Eagle bestowed a kingly feather, the Thrush, the Nightingale,—every bird contributed except the Owl.

But the selfish Owl said, "I see no reason why I should give a feather. Hoot! No! The Wren brought me into trouble once, and I will not help him now. Let him go bare, for all my aid."

"Shame! Shame!" cried the birds indignantly. "Old Master Owl, you ought to be ashamed. But if you are so selfish we will not have you in our society. Go back to your hollow tree!"

"Yes, go back to your hollow tree," cried the Eagle sternly; "and when winter comes may you shiver with cold as you would have left the brave little Wren to shiver this day. You shall ruffle your feathers as much as you like, but you will always feel cold at heart, because your heart is selfish."

And indeed, since that day for all his feathers the Owl has never been able to keep warm enough in his lonely hollow tree.

But the Wren became one of the happiest of all the birds, and a favorite both with his feathered brothers and with men, because of his brave deed, and because of the great fire-gift which he had brought from the sun.

F course every one knows that the Bluebird was made from a

piece of the azure sky itself. One has only to match his

wonderful color against the April heaven to be sure of that.

Therefore the little Bluebird was especially dear to the Spirit

of the sky, the Father in Heaven.

F course every one knows that the Bluebird was made from a

piece of the azure sky itself. One has only to match his

wonderful color against the April heaven to be sure of that.

Therefore the little Bluebird was especially dear to the Spirit

of the sky, the Father in Heaven.

One day this venturesome little bird started out upon a long journey across the wide Pacific Ocean toward this New World which neither Columbus nor any other man had yet discovered. Under him tossed the wide, wide sea, rolling for miles in every direction, with no land visible anywhere on which a little bird might rest his foot. For this was also before there were any islands in all that stretch of waters. Soon the poor little Bluebird became very weary and wished he had not ventured upon so long a flight. His wings began to droop and he sank lower and lower toward the sea which seemed eager to overwhelm his blueness with its own. He had come so far over the salty wastes that he was very thirsty; but with water, water everywhere there was not a drop to drink. The poor little bird glanced despairingly up toward the blue sky from which he had been made and cried,—

"O Spirit of the blue sky, O my Father in Heaven, help your child the Bluebird! Give me, I pray you, a place to rest and refreshment for my thirsty throat, or I perish in the cruel blue waters!"

At these sorrowful words the kind Father took pity upon his little Bluebird. And what do you think? He made a baby earthquake which heaved a rocky point of land up through the waves, just big enough for a little bird's perch. It was a tiny reef, and a crack in the rock held but a few drops of the rain which began to fall; but it meant at least a moment's safety and draught of life for the weary bird, and glad enough he was to reach it.

He had not been there long, however, when a big wave almost washed him away. He was not yet safe. Still he lacked the rest and refreshment which he so sorely needed. For the raindrops were soon turned brackish by the waves which dashed upon the reef from all sides, and the Bluebird had to keep hopping up and down to avoid being drowned in the tossing spray. He was more tired than ever, and this continuous exercise made him even more thirsty. Once more he prayed to the Father for help. And once more the kind Spirit of the Sky heard him from the blueness.

This time there was a terrible earthquake, until the sea boiled and rolled into huge waves as if churned by a mighty churn at the very bottom of things, and with a terrified scream the Bluebird flew high into the air.

But when the noise and the rumbling died away and once more the sea lay calm and still, what do you think the Bluebird saw? The great ocean which had once stretched an unbroken sheet of blue as far as the eye could see was now dotted here and there by islands, big islands and little islands, groups and archipelagoes of them, just as on the map one sees them to-day peppering the Pacific Ocean. Samoa came up, and Tonga, and Tulima, and many others with names quite as bad, if not worse. From one island to another the Bluebird flew, finding rest and refreshment on each, until he reached the mainland in safety. And there the islands remain to this day for other travelers to visit, breaking their journey from west to east or from east to west. There are forests and cascades, springs of fresh and pleasant water, delicious fruits, wonderful birds and animals, and finally a race of strange, dark men. (But they came long, long after.)

So the Bluebird crossed the Pacific, folk tell. Was it not wonderful how the kind Father came to scatter those many islands in the Pacific Ocean,—stepping-stones for a tiny little Bluebird so that he need not wet his feet in crossing that wide salty river?

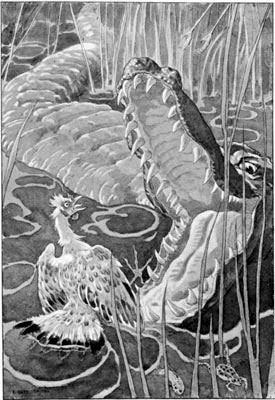

ONG, long ago in the days of wise King Solomon, the Crow

and the Pheasant were the best of friends, and were always seen

going about together, wing in wing. Now the Pheasant was the

Peacock's own cousin,—a great honor, many thought, for the

Peacock was the most gorgeous of all the birds. But it was not

altogether pleasant for the Pheasant, because at that time he

wore such plain and shabby old garments that his proud relative

was ashamed of him, and did not like to be reminded that they

were of the same family. When the Peacock went strutting about

with his wonderful tail spread fan-wise, and with his vain little

eyes peering to see who might be admiring his beauty, the

Peacock's cousin and his friend the Crow, who was then a plain

white bird, would slink aside and hide behind a tree,

whence they would peep enviously until the Peacock had passed by.

Then the Peacock's cousin would say,—

ONG, long ago in the days of wise King Solomon, the Crow

and the Pheasant were the best of friends, and were always seen

going about together, wing in wing. Now the Pheasant was the

Peacock's own cousin,—a great honor, many thought, for the

Peacock was the most gorgeous of all the birds. But it was not

altogether pleasant for the Pheasant, because at that time he

wore such plain and shabby old garments that his proud relative

was ashamed of him, and did not like to be reminded that they

were of the same family. When the Peacock went strutting about

with his wonderful tail spread fan-wise, and with his vain little

eyes peering to see who might be admiring his beauty, the

Peacock's cousin and his friend the Crow, who was then a plain

white bird, would slink aside and hide behind a tree,

whence they would peep enviously until the Peacock had passed by.

Then the Peacock's cousin would say,—

"Oh, how beautiful, how grand, how noble he is! How came such a lordly bird to have for a cousin so homely a creature as I?"

But the Crow would answer, trying to comfort his friend, "Yes, he is gorgeous. But listen, what a harsh and disagreeable voice he has! And see how vain he is. I would not be so vain had I so scandalous a tale in my family history."

Then the Crow told the Peacock's cousin how his proud relative came to have so unmusical a voice.

When Adam and Eve were living peacefully in their fair garden, while Satan was still seeking in vain a way to enter there, the Peacock was the most beautiful of all the companions who surrounded the happy pair. His plumage shone like pearl and emerald, and his voice was so melodious that he was selected to sing the Lord's praises every day in the streets of heaven. But he was then, as now, very, very vain; and Satan, prowling about outside the wall of Paradise, saw this.

"Aha!" he said to himself, "here is the vainest creature in all the world. He is the one I must flatter in order to win entrance to the garden, where I am to work my mischief. Let me approach the Peacock."

Satan stole softly to the gate and in a wheedling voice called to the Peacock,—

"O most wonderful and beautiful bird! Are you one of the birds of Paradise?"

"Yes, I am one of the dwellers in the happy garden," answered the Peacock, strutting. "But who are you who slink about so secretly, as if afraid of some one?"

"I am one of the cherubim who are appointed to sing the Lord's praises," answered the wicked Satan. "I have stopped for a moment to visit the Paradise which He has prepared for the blest, and I find as my first glimpse of its glories you, O most lovely bird! Will you conceal me under your rainbow wings and bring me within the walls?"

"I dare not," answered the Peacock. "The Lord allows none to enter here. He will be angry and will punish me."

"O charming bird!" went on Satan with his smooth tongue, "take me with you, and I will teach you three mysterious words which shall preserve you forever from sickness, age, and death."

At this promise the Peacock was greatly tempted and began to hesitate in his refusals. And at last he said,—

"I dare not myself let you in, O stranger, but if you keep your promise I will send the Serpent, who is wiser than I and who may more easily find some way to let you enter unobserved."

So it was through the Peacock that Satan met the vile Serpent, whose shape he assumed in order to enter the garden and tempt Eve with the apple. And for the Peacock's share in the doings of that dreadful day the Lord took away his beautiful voice and sent him forth from the pleasant garden to chatter harshly in this workaday world, where his gorgeousness and his vanity are but a reminder to men of the shame which he brought upon their ancestors.

"And therefore," said the Crow, concluding his gossip, "therefore, dear Pheasant, I see no reason why we should envy your cousin. We are very plain citizens of Birdland, but we are at least respectable. I like you much better, having nothing to make you vain, nothing of which to be ashamed."

So the Crow spoke, in the wisdom which he had learned from Solomon. But the Peacock's cousin refused to be comforted. The shabbiness of his coat preyed upon his mind, and he fancied that the other birds jeered at him because in such old clothes he dared to be the Peacock's cousin. It seemed to him that every day the Peacock himself grew more haughty and more patronizing.

One day the Crow and the Peacock's cousin were sauntering through the Malay woods when they met the Peacock face to face. The Crow looked defiant and stood jauntily; but the Pheasant tried to shrink out of sight. The Peacock, however, had spied his poor relative, and was filled with cousinly resentment at his appearance.

He stopped short. He stood upon one leg. He puffed and ruffled himself, spreading out his thousand-eyed tail so that its colors flashed wonderfully in the sunshine. He frilled his neck feathers and snapped his mean little eyes maliciously; then turning his back on the shabby couple said, as he stepped airily away,—

"Ah, I have dropped some of my old feathers back there a little way. You can have them if you like, Pheasant. They will freshen you up a bit; you really are looking shockingly seedy. But for mercy's sake don't wear them in my presence! I can't bear to see any one parading in my cast-off elegance." Then the Peacock minced away.

The Peacock's cousin stamped on the ground and flapped his wings with rage. If he had been a girl he would have burst into tears. "I cannot stand this," he cried. "To be treated as if I were a beggar! To be given old clothes to wear! Crow, Crow, if you were any kind of friend you would help me. But you stand staring there and see me insulted, without turning a feather! What is the use of all your wisdom that you learned from King Solomon if you cannot help a friend in need? I tell you, I must have some better garments, or I shall die of mortification."

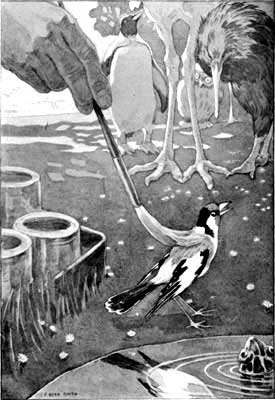

"Don't be excited," said the Crow soothingly. "I have been thinking the matter over, and I believe I can do something. Listen. Yesterday I found brushes and a box of colors in a room of the King's palace. They belonged to the Court Painter. Now they belong to me, for I have hidden them away in a hollow tree where no one else can find them. I thought they might be useful, and I think so still."

"Well, well! What do you propose to do with paints and brushes?" cried the Peacock's cousin impatiently.

"I propose to paint you, to varnish you, to gild you," patiently answered the Crow.

"Oh, you dear Crow!" exclaimed the other, clapping his wings. "You will make me brilliant and beautiful! You will make me worthy of the Peacock, will you not? How clever of you to think of such a thing!"

"Yes," replied the Crow; "I watched the Court Painter at work in the garden one day, and I know how it is done. I will make you as gorgeous as you wish. But you must return the compliment. If you are to be an ornament of fashion, so must I be; for are we not inseparable cronies? And when you become beautiful it would not do for you to be seen with such a dowdy as I am."

"You dear creature!" said the Peacock's cousin affectionately; "of course we will share alike. I will paint you as soon as I see how you succeed with me. Ah, I know your skill in everything. You will be a fine artist, my friend! But come, let us get to work at once."

So the flattered Crow led him to the hollow tree where he had concealed the brushes and the gilding and the India ink, and all the gorgeous changeable tints which an Eastern artist uses in his paintings. "Here we are," said the Crow. "Now let us see what we shall see, when Master Crow turns painter."

The Crow set to work with a will, splashing on the colors generously, gold and green and bronze iridescence. He had the Peacock in mind, and though he did not exactly copy the plumage of that wonderful bird, he managed to suggest the cousinship of the Pheasant in the golden eyes of his long and beautiful tail. When he had finished, the Crow was delighted with his work.

"Ah!" he cried. "Now bend over this fountain, my dear friend, and observe yourself. I think you do credit to my skill as an artist, eh?"

The Peacock's cousin hurried down to the water-pool, all in a flutter of excitement. And when he saw his image he cried, "How beautiful, how truly beautiful, I am! Why, I am quite as handsome as Peacock himself. Surely, now he need not be ashamed to call me cousin. I shall move in the most fashionable circles. Heavens! Look at my lovely tail! Look at my burnished feathers! I must go immediately and show my new dress to Cousin Peacock. I should not be surprised if he became jealous of my gorgeousness." And off he started as fast as he could go.

"Hold on!" cried the Crow. "Don't run away so quickly. You have forgotten something. Don't you remember that you promised to paint me beautiful like yourself?"

"Oh, bother!" answered the ungrateful friend, tossing his head. "I have no time now for such business. I must hasten to my cousin, for this is a matter of family pride. Run along like a good creature; and by the way, you may as well gather the feathers which Peacock mentioned. I am sure they will make you look quite respectable. Besides, I will give you some of mine when I have worn them a little. Ta-ta!" And he stepped airily away.

But the Crow strode after him, shaking his wings and crying, "Come back, come back and perform your part of the bargain, you selfish, ungrateful creature!" And he caught the Pheasant by one of his long tail-feathers.

"Let go my train, impertinent wretch!" shrieked the Peacock's cousin, turning upon him fiercely. "I tell you I have no time to spend in such nonsense. I must be presenting myself in high society."

"Villain!" croaked the Crow, and he rushed forward fiercely, intending to tear out the beautiful feathers which he had painted for his ungrateful friend. Thereupon the Pheasant exclaimed,—

"You want to be painted, do you? Well, take that!" and, seizing the bottle of India ink which was in the Eastern artist's paint-box, he hurled it at the poor Crow, deluging with blackness his spotless feathers. Then laughing harshly, away he flew to his cousin the Peacock, who received him with proud affection, because they were now really birds of a feather. For the Peacock's cousin was become one of the most beautiful birds in the world.

But the poor Crow was now a sombre, black bird, wearing the seedy-looking, inky coat which we know so well to-day. His heart was broken by his friend's faithlessness, and he became a sour cynic who can see no good in anything. He flies about crying "Caw! Caw!" in the most disagreeable, sarcastic tone, as if sneering at the mean action of that Malay bird, which he can never forget.

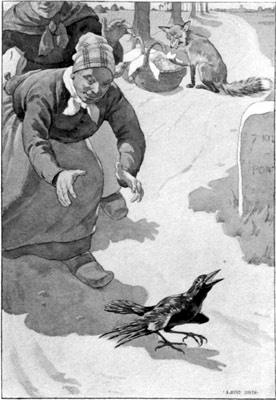

HE Crow became very sour and disagreeable after his friend

the Peacock's cousin deserted him for more gorgeous company.

Though he pretended not to care because the Pheasant was now a

proud, beautifully-coated dandy, while he was the shabbiest of

all the birds in his coat of rusty black, yet in truth he did

care very much. He could not forget how the Peacock's cousin had

dyed him this sombre hue, after promising to paint him bright and

wonderful, like himself. He could not help thinking how fine he

would have looked in similar plumage of a rainbow tint, or how

becoming a long swallow-tail would be to his style of beauty. He

wished that there was a tailor in Birdland to whom he could go

for a new suit of clothes. But alas! There seemed no way but for

him to remain ugly old Crow to the end of the chapter.

HE Crow became very sour and disagreeable after his friend

the Peacock's cousin deserted him for more gorgeous company.

Though he pretended not to care because the Pheasant was now a

proud, beautifully-coated dandy, while he was the shabbiest of

all the birds in his coat of rusty black, yet in truth he did

care very much. He could not forget how the Peacock's cousin had

dyed him this sombre hue, after promising to paint him bright and

wonderful, like himself. He could not help thinking how fine he

would have looked in similar plumage of a rainbow tint, or how

becoming a long swallow-tail would be to his style of beauty. He

wished that there was a tailor in Birdland to whom he could go

for a new suit of clothes. But alas! There seemed no way but for

him to remain ugly old Crow to the end of the chapter.

The Crow went moping about most unhappily while this was preying on his mind, until he really became somewhat crazy upon the subject. The only thing about which he could think was clothes—clothes—clothes; and that is indeed a foolish matter to absorb one's mind. One word of the Peacock's cousin remained in his memory and refused to be forgotten. He had advised the Crow to gather up the feathers which had fallen from the Peacock's plumage and to make himself fine with them. First the Crow remembered these words sadly, because they showed the unkind heart of his old friend. Next he remembered them with scorn, because they showed vanity. Then he remembered them with interest because they gave him an idea. And that idea gradually grew bigger and bigger until it became a plan.

The plan came to him completely one day while he was sitting moodily on a tree watching the Peacock and his cousin sweeping proudly over the velvet lawn of the King's garden. For nowadays the Pheasant moved in the most courtly circles, as he had promised himself. As they passed under the Crow two beautiful feathers fell behind them and lay on the grass shining in the sunlight with a hundred colors.

"Once more the cast-off plumage of the Peacock family is left for me!" croaked the Crow to himself. "Am I only to be made beautiful by borrowing from others? Perhaps I might collect feathers enough from all the birds to conceal my inky coat. Aha! I have it." And this was the plan of the Crow. He would steal from every dweller in Birdland a feather, and see whether he could not make himself more beautiful than the Peacock's cousin himself.

Now the Crow was a skilful thief. He could steal the silver off the King's table from under the steward's very nose. He could steal a maid's thimble from her finger as she nodded sleepily over her work. He could steal the pen from behind a scribe's ear, as he paused to scratch his head and think over the spelling of a word. So the Crow felt sure that he could steal their feathers from the birds without any trouble.

When the Peacock and his cousin had passed by, the Crow swooped down and carried off the two feathers which were to begin his collection. He hid them in his treasure-house in the hollow tree, and started out for more.

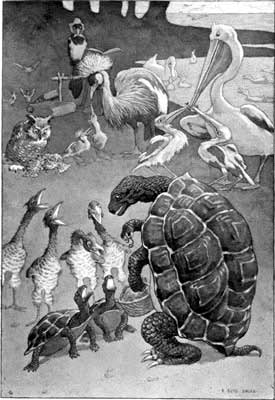

It was great fun for the Crow, and he almost forgot to be miserable. He followed old lady Ostrich about for some time before he dared tweak a handful of feathers from her tail. But finally he succeeded; and though she squawked horribly and turned, quick as a flash, she was not quick enough to catch the nimble thief, who was already hidden under a bush. In the same way he secured some lovely plumes from the Bird of Paradise, the Parrot, and the Cock. He robbed the Redbreast of his ruddy vest, the Hoopoe of his crown, and he secured a swallow-tail which he had long coveted. He took some rosy-redness from the Flamingo, the gilding of the Goldfinch, the gray down of an Eider-Duck. He burgled the Bluebird and the Redbird and the Yellowbird; and not one single feathered creature escaped his clever beak. At last his hole in the tree was brimming with feathers of every color, length, and degree of softness, a gorgeous feather-bed on which it would dazzle one to sleep.

Then the Crow set to work to make himself a coat of many colors, like Joseph's. He was a very clever bird, and a wondrous coat it turned out to be. It had no particular cut nor style; it was not like the coat which any bird had ever before worn. The feathers were placed in any fashion that happened to please his original fancy. Some pointed up and some down; some were straight and some were curled; some drooped about his feet and others curved gracefully over his head; some trailed far behind. He was completely covered from top to toe, so that not one blot of his own inky feathers showed through the gorgeousness. A red vest he wore, and a swallow-tail, of course, and there was a crown of feathers on his head. Never was there seen a more extraordinary bird nor one more gaudy. Perhaps he was not in the best of taste, but at least he was striking.

When all was finished the Crow went and looked at himself in the fountain mirror; and he was much pleased.

"Well now!" he cried. "How am I for a bird? I believe no one will know me, and that is just as well; for now I am so fine that I shall myself refuse to know any one. Ho! This ought to give some ideas to that conceited Peacock family! I am a self-made man. I am an artist who knows how to adapt his materials. I am a genius. King Solomon himself will wonder at my glory. And as for the Eagle, King of the Birds, he will grow pale with envy. King of the Birds, indeed! It is now I who should rightfully be King. No other ever wore clothes so fine as mine. By right of them I ought to be King of the Birds. I will be King of the Birds!"

You see the poor old Crow was quite crazy with his one idea.

Forth he stalked into Birdland to show his gorgeous plumage and to get himself elected King of the Birds. The first persons he met were the Peacock and his cousin,—he who was once the Crow's best friend. The Crow ruffled himself his prettiest when he saw them coming.

"Good gracious! Who is that extraordinary fowl?" drawled the Peacock. "He must be some great noble from a far country."

"How beautiful!" murmured his silly cousin. "How odd! How fascinating! How distinguished! I wish the Crow had painted me like that!" The Crow heard these words and swelled with pride, casting a scornful glance at his old friend as he swept by.

Next he met a little Sparrow who was picking bugs from the grass. "Out of my way, Birdling!" cried the Crow haughtily. "I am the King."

"The King!" gasped the Sparrow, nearly choking over a fat bug, he was so surprised. "I did not know that the King wore such a robe. How gorgeous—but how queer!"

Next the Crow met Mr. Stork, standing gravely on one leg and thinking of the little baby which he was going to bring that night to the cottage by the lake. The Stork looked up in surprise as the wonderful stranger approached.

"Bless me!" he exclaimed, "whom have we here? I thought I knew all Birdland, but I never before saw such a freak as this!"

"Bless me!" he exclaimed, "whom have we here?"

"I am the King. I am to be the new King," announced the Crow. "Is there any bird more gorgeous than I?"

"Truly, I hope not," said the Stork gravely. "Yet the Woodcock is a very foolish bird. One never knows what he will do next. If he should try to be fashionable"—