The Lusiad

From National Epics By Kate Milner Rabb

Presented by Authrama Public Domain Books

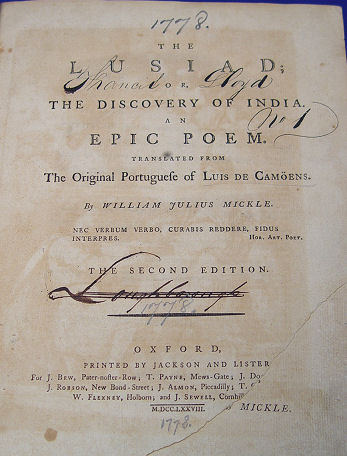

The Lusiad, Or, the Discovery of India. an Epic Poem, Translated From the Original Portuguese of Luis De Camoens by Mickle, William Julius. Printed by Jackson and Lister.

“The discovery of Mozambique, of Melinda, and of Calcutta has been sung by Camoens, whose poem has something of the charm of the Odyssey and of the magnificence of the Aeneid.”

Montesquieu.

The Portuguese epic, the Lusiad, so-called from Lusitania, the Latin name for Portugal, was written by Luis de Camoens.

He was born in Lisbon in 1524, lost his father by shipwreck in infancy, and was educated by his mother at the University of Coimbra. On leaving the university he appeared at court, where his graces of person and mind soon rendered him a favorite. Here a love affair with the Donna Catarina de Atayde, whom the king also loved, caused his banishment to Santarem. At this place he began the Lusiad, and continued it on the expedition against the Moors in Africa sent out by John III., an expedition on which he displayed much valor and lost an eye. He was recalled to court, but jealousies soon drove him thence to India, whither he sailed in 1553, exclaiming, “Ungrateful country, thou shall not possess my bones.” In India his bravery and accomplishments won him friends, but his imprudences soon caused his exile to China, where he accumulated a small fortune and finished his poem. Happier circumstances permitted him to return to Goa; but on the way the ship laden with his fortune sank, and he escaped, saving only his poem. After sixteen years of misfortune abroad, Camoens returned to Lisbon in 1569. The pestilence that was then raging delayed the publication of the Lusiad until 1572. The poem received little attention; a small pension was bestowed on the poet, but was soon withdrawn, and the unfortunate Camoens was left to die in an almshouse. On his death-bed he deplored the impending fate of his country, which he alone could see. “I have loved my country. I have returned not only to die on her bosom, but to die with her.”

The Lusiad tells the story of the voyage of Vasco da Gama. The sailors of Prince Henry of Portugal, commander of the Portuguese forces in Africa, had passed Cape Nam and discovered the Cape of Storms, which the prince renamed the Cape of Good Hope. His successor Emmanuel, determined to carry out the work of his predecessor by sending out da Gama to undertake the discovery of the southern passage to India. The Portuguese were generally hostile to the undertaking, but da Gama, his brother, and his friend Coello gathered a company, part of which consisted of malefactors whose sentence of death was reversed on condition that they undertake the voyage, and reached India.

The Lusiad is divided into ten cantos, containing one thousand one hundred and two stanzas. Its metre is the heroic iambic, in rhymed octave stanzas.

The Lusiad is marred by its mythological allusions in imitation of Homer and Virgil, but these are forgotten when the poet sings in impassioned strains of his country’s past glory.

The Lusiad is simple in style; its subject is prosaic; it is a constant wonder that out of such unpromising materials Camoens could construct a poem of such interest. He could not have done so had he not been so great a poet, so impassioned a patriot.

Camoens was in one sense of the word a practical man, like Ariosto; he had governed a province, and governed it successfully. But he had also taken up arms for his country, and after suffering all the slights that could be put upon him by an ungrateful and forgetful monarch, still loved his native land, loved it the more, perhaps, that he had suffered for it and was by it neglected. He foresaw, also, as did no one else, the future ruin of his country, and loved it the more intensely, as a parent lavishes the fondest, most despairing affection on a child he knows doomed to early death.

The Lusiad is sometimes called the epic of commerce; it could be called far more appropriately the epic of patriotism.

When Jupiter, looking down from Olympus, saw the Lusitanian fleet sailing over the heretofore untravelled seas, he called the gods together, and reviewing the past glory of the Portuguese, their victories over the Castilians, their stand against the Romans, under their shepherd-hero Viriatus, and their conquest of Africa, he foretold their future glories and their discovery and conquest of India.

Bacchus, who had long since made conquests in India, fearful lest his ancient honors should be forgotten, bitterly opposed the scheme of the Portuguese; Venus, however, was favorable to them, and Mars interceded, counselling Jove not to heed Bacchus, but to permit the Lusitanians to reach India’s shore in safety.

When the council of the gods was dismissed, Mercury was sent to guide the Armada, which made its first landing at Mozambique. Canoes with curious palm-leaf sails, laden with dark-skinned natives, swarmed round the ships and were hailed with joy by Gama and his men, who invited them on board. A feast was spread for them, and to them Gama declared his intention of seeking India. Among them was a Moor who had at first thought the Portuguese Moors, on account of their dark skins. Feigning cordiality while plotting their ruin, he offered them a pilot to Quiloa, where, he assured them, they would find a Christian colony. He and his friends also laid a plot to place some soldiers in ambush to attack Gama’s men when they landed next day to get water; in this way many would be destroyed, and certain death awaited the survivors at Quiloa, whither the promised pilot would conduct them. But the Moors had not counted on the strength of the Portuguese. Gama’s vengeance was swift and certain. The thunder of his guns terrified the Moors, and the regent implored his pardon, and with make-believe tears insisted on his receiving at his hands the promised pilot.

Many questions were asked by Gama concerning the spicy shores of India, of the African coasts, and of the island to the north. “Quiloa, that," replied the Moor, “where from ancient times, the natives have worshipped the blood-stained image of the Christ.” He knew how the Moorish inhabitants hated the Christians, and was secretly delighted when Gama directed him to steer thither.

A storm swept the fleet past Quiloa, but the pilot, still determined on revenge, pointed out the island town of Mombaça, as a stronghold of the Christians, and steering the fleet thither, anchored just outside the bar. Bacchus, now intent on the destruction of the Lusitanians, assumed the character of a priest to deceive the heralds sent ashore by Gama, who assured their commander that they saw a Christian priest performing divine rites at an altar above which fluttered the banner of the Holy Ghost. In a few moments the Christian fleet would have been at the mercy of the Moors, but Cytherea, beholding from above the peril of her favorites, hastily descended, gathered together her nymphs, and formed an obstruction, past which the vessels strove in vain to pass. As Gama, standing high on the poop, saw the huge rock in the channel, he cried out, and the Moorish pilots, thinking their treason discovered, leaped into the waves.

Warned in a dream by Mercury that the Moors were preparing to cut his cables, De Gama roused his fleet and set sail for Melinda, whose monarch, Mercury had told him, was both powerful and good.

The fleet, decorated with purple streamers and gold and scarlet tapestry in honor of Ascension Day sailed with drums beating and trumpets sounding, into the harbor of Melinda, where they were welcomed by the kind and truthful people. The fame of the Lusitanians had reached Melinda, and the monarch gladly welcomed them to his land. His herald entreated them to remain with him, and brought them sheep, fowls, and the fruits of the earth, welcome gifts to the mariners. Gama had vowed not to leave the ship until he could step on Indian ground, so the next day the king and the commander, clad in their most splendid vestments, met in barges, and the monarch of Melinda asked Gama to tell him of the Lusian race, its origin and climate, and of all his adventures up to the time of his arrival at Melinda.

“O king,” said Gama, “between the zones of endless winter and eternal summer lies beautiful Europe, surrounded by the sea. To the north are the bold Swede, the Prussian, and the Dane; on her south-eastern line dwelt the Grecian heroes, world-renowned, and farther south are the ruins of proud Rome. Among the beauteous landscapes of Italy lies proud Venice, queen of the sea, and north of her tower the lofty Alps. The olive groves and vineyards of fair Gallia next greet the eye, and then the valorous fields of Spain, Aragon, Granada, and–the pride of Spain–Castile. On the west, a crown to it, lies Lusitania, on whom last smiles the setting sun,–against whose shores roll the waves of the western sea.

“Noble are the heroes of my country. They were the first to rise against the Moors and expel them from the kingdom. The forces of Rome were routed by our shepherd-hero, Viriatus. After his death our country languished until Alonzo of Spain arose, whose renown spread far and wide because of his battles against the Moors.

“Alonzo rewarded generously the heroes who fought under him, and to Prince Henry of Hungaria he gave the fields through which the Tagus flows and the hand of his daughter. To them was born a son, Alfonso, the founder of the Lusian throne. After the death of his father Henry, Alfonso’s mother became regent, and ere long wedded her minister Perez and plotted to deprive her young son of his inheritance. The eighteen year old son arose, won the nobility to his side, and defeated his guilty mother and her husband in the battle of Guimaraens. Forgetful of the reverence due to parents, he cruelly imprisoned his mother, whose father, the king of Spain, indignant at such treatment of his daughter, now marched against the young prince and defeated him. As he lay in prison, his faithful guardian Egas knelt before the king, and vowed that his master, if released, would pay homage to him. Well he knew that his master would never bow his proud head to pay homage to Castile. So when the day arrived, Egas, and all his family, clad in gowns of white like sentenced felons, with unshod feet, and with the halter around their necks, sought Castile. ’O king, take us as a sacrifice for my perjured honor. Turn in friendship to the prince thy grandson, and wreak thy vengeance on us alone.’

“Fortunately Alonzo was noble enough to release the self-sacrificing Egas, and to forgive his grandson.

“The young Alfonso, pardoned by his grandfather, proceeded to Ourique, whither marched five Moorish kings. Over his head appeared the sacred cross; but he prayed heaven to show it to his army instead, that they might be inspired with the hope of victory. Filled with joy at the token, the Portuguese defeated the Moors, and on the bloody battle-field Alfonso was proclaimed King of Portugal, and from that day placed on his hitherto unadorned buckler five azure shields, arranged as a cross. He continued the wars with the Moors until, wounded and taken prisoner at Badajoz, he resigned the throne to his son, Don Sancho, who in turn won many victories. Alfonso II., Sancho II., Alfonso III., and Alfonso the Brave succeeded him. At the court of the latter was a beautiful maiden, Inez de Castro, whom Alfonso’s son Don Pedro had married secretly. The courtiers, fearful lest Pedro should show favor to the Castilians because Inez was the daughter of a Castilian, told the king of his son’s amour. In the absence of Pedro, Inez was led before the king, bringing with her her children, to help her to plead for mercy. But the king was merciless, his counsellors, brutal, and at his signal they stabbed her. Pedro never recovered from the shock given him by the fate of his beautiful wife, and after his succession to the throne, as a partial atonement for her suffering, he had her body taken from the grave and crowned Queen of Portugal.

“The weak Fernando, who took his wife Eleanora from her lawful husband, succeeded Pedro, and their daughter Beatrice not being recognized by the Portuguese, at his death Don John, a natural brother, came to the throne. In the mean time a Spanish prince had married Beatrice and invaded Portugal, claiming it as his right. The Portuguese were divided until Nuño Alvarez Pereyra came forward. ’Has one weak reign so corrupted you?’ he cried. ’Have you so soon forgotten our brave sires? Fernando was weak, but John, our godlike king, is strong. Come, follow him! Or, if you stay, I myself will go alone; never will I yield to a vassal’s yoke; my native land shall remain unconquered, and my monarch’s foes, Castilian or Portuguese, shall heap the plain!’

“Inspired by Nuño’s eloquence the Lusians took the field and defeated the Spanish in the battle of Aljubarota. Still dissatisfied, Nuño pressed into Spain and dictated the terms of peace at Seville. Having established himself upon the throne of Portugal, John carried the war into Africa, which wars were continued after his death by his son Edward. While laying siege to Tangier, Edward and his brother Fernando were taken prisoners, and were allowed to return home only on promise to surrender Ceuta. Don Fernando remained as the hostage they demanded. The Portuguese would not agree to surrender Ceuta, and Don Fernando was forced to languish in captivity, since the Moors would accept no other ransom. He was a patriotic prince than whom were none greater in the annals of Lusitania.

“Alfonso V., victorious over the Moors, dreamed of conquering Castile, but was defeated, and on his death was succeeded by John II., who designed to gain immortal fame in a way tried by no other king. His sailors sought a path to India, but ’though enriched with knowledge’ they perished at the mouth of the Indus. To his successor, Emmanuel, in a dream appeared the rivers Ganges and Indus, hoary fathers, rustic in aspect, yet with a majestic grace of bearing, their long, uncombed beards dripping with water, their heads wreathed with strange flowers, and proclaimed to him that their countries were ordained by fate to yield to him; that the fight would be great, and the fields would stream with blood, but that at last their shoulders would bend beneath the yoke. Overjoyed at this dream, Emmanuel proclaimed it to his people. I, O king, felt my bosom burn, for long had I aspired to this work. Me the king singled out, to me the dread toil he gave of seeking unknown seas. Such zeal felt I and my youths as inspired the Mynian youths when they ventured into unknown seas in the Argo, in search of the golden fleece.

“On the shore was reared a sacred fane, and there at the holy shrine my comrades and I knelt and joined in the solemn rites. Prostrate we lay before the shrine until morning dawned; then, accompanied by the ’woful, weeping, melancholy throng’ that came pressing from the gates of the city, we sought our ships.

“Then began the tears to flow; then the shrieks of mothers, sisters, and wives rent the air, and as we waved farewell an ancient man cried out to us on the thirst for honor and for fame that led us to undertake such a voyage.

“Soon our native mountains mingled with the skies, and the last dim speck of land having faded, we set our eyes to scan the waste of sea before us. From Madeira’s fair groves we passed barren Masilia, the Cape of Green, the Happy Isles, Jago, Jalofo, and vast Mandinga, the hated shore of the Gorgades, the jutting cape called by us the Cape of Palms, and southward sailed through the wild waves until the stars changed and we saw Callisto’s star no longer, but fixed our eyes on another pole star that rises nightly over the waves. The shining cross we beheld each night in the heavens was to us a good omen.

“While thus struggling through the untried waves, and battling with the tempests, now viewing with terror the waterspouts, and the frightful lightnings, now comforted by the sight of mysterious fire upon our masts, we came in sight of land, and gave to the trembling negro who came to us some brass and bells. Five days after this event, as we sailed through the unknown seas, a sudden darkness o’erspread the sky, unlighted by moon or star. Questioning what this portent might mean, I saw a mighty phantom rise through the air. His aspect was sullen, his cheeks were pale, his withered hair stood erect, his yellow teeth gnashed; his whole aspect spoke of revenge and horror.

“’Bold are you,’ cried he, ’to venture hither, but you shall suffer for it. The next proud fleet that comes this way shall perish on my coast, and he who first beheld me shall float on the tide a corpse. Often, O Lusus, shall your children mourn because of me!’ ’Who art thou?’ I cried. ’The Spirit of the Cape,’ he replied, ’oft called the Cape of Tempests.’”

The king of Melinda interrupted Gama. He had often heard traditions among his people of the Spirit of the Cape. He was one of the race of Titans who loved Thetis, and was punished by Jove by being transformed into this promontory.

Gama continued: “Again we set forth, and stopped at a pleasant coast to clean our barks of the shell-fish. At this place we left behind many victims of the scurvy in their lonely graves. Of the treason we met with at Mozambique and the miracle that saved us at Quiloa and Mombas, you know already, as well as of your own bounty.”

Charmed with the recital of Gama, the King of Melinda had forgotten how the hours passed away. After the story was told the company whiled away the hours with dance, song, the chase, and the banquet, until Gama declared that he must go on to India, and was furnished with a pilot by the friendly king.

Bacchus, enraged at seeing the voyage so nearly completed, descended to the palace of Neptune, with crystal towers, lofty turrets, roofs of gold, and beautiful pillars inwrought with pearls. The sculptured walls were adorned with old Chaos’s troubled face, the four fair elements, and many scenes in the history of the earth. Roused by Bacchus, the gods of the sea consented to let loose the winds and the waves against the Portuguese.

During the night, the Lusians spent the time in relating stories of their country. As they talked, the storm came upon them, and the vessels rose upon the giant waves, so that the sailors saw the bottom of the sea swept almost bare by the violence of the storm. But the watchful Venus perceived the peril of her Lusians, and calling her nymphs together, beguiled the storm gods until the storm ceased. While the sailors congratulated themselves on the returning calm, the cry of “Land!” was heard, and the pilot announced to Gama that Calicut was near.

Hail to the Lusian heroes who have won such honors, who have forced their way through untravelled seas to the shores of India! Other nations of Europe have wasted their time in a vain search for luxury and fame instead of reclaiming to the faith its enemies! Italy, how fallen, how lost art thou! and England and Gaul, miscalled “most Christian!” While ye have slept, the Lusians, though their realms are small, have crushed the Moslems and made their name resound throughout Africa, even to the shores of Asia.

At dawn Gama sent a herald to the monarch; in the mean time, a friendly Moor, Monçaide, boarded the vessel, delighted to hear his own tongue once more. Born at Tangiers, he considered himself a neighbor of the Lusians; well he knew their valorous deeds, and although a Moor, he now allied himself to them as a friend. He described India to the eager Gama: its religions, its idolaters, the Mohammedans, the Buddhists, the Brahmins. At Calicut, queen of India, lived the Zamorin, lord of India, to whom all subject kings paid their tribute.

His arrival having been announced, Gama, adorned in his most splendid garments, and accompanied by his train, also in bright array, entered the gilded barges and rowed to the shore, where stood the Catual, the Zamorin’s minister. Monçaide acted as an interpreter. The company passed through a temple on their way to the palace, in which the Christians were horrified at the graven images there worshipped. On the palace walls were the most splendid pictures, relating the history of India. One wall, however, bore no sculptures; the Brahmins had foretold that a foreign foe would at some time conquer India, and that space was reserved for scenes from those wars.

Into the splendid hall adorned with tapestries of cloth of gold and carpets of velvet, Gama passed, and stood before the couch on which sat the mighty monarch. The room blazed with gems and gold; the monarch’s mantle was of cloth of gold, and his turban shone with gems. His manner was majestic and dignified; he received Gama in silence, only nodding to him to tell his story.

Gama proclaimed that he came in friendship from a valorous nation that wished to unite its shores with his by commerce. The monarch responded that he and his council would weigh the proposal, and in the mean time Gama should remain and feast with them.

The next day the Indians visited the fleet, and after the banquet Gama displayed to his guests a series of banners on which were told the history of Portugal and her heroes. First came Lusus, the friend of Bacchus, the hero-shepherd Viriatus, the first Alonzo, the self-sacrificing Egas, the valiant Fuaz, every hero who had strengthened Lusitania and driven out her foes, down to the gallant Pedro and the glorious Henry.

Awed and wondering at the deeds of the mighty heroes, the Indians returned home. In the night Bacchus appeared to the king, warning him against the Lusians and urging him to destroy them while in his power. The Moors bought the Catual with their gold. They also told the king that they would leave his city as soon as he allied himself with the odious strangers. When Gama was next summoned before the king he was received with a frown.

“You are a pirate! Your first words were lies. Confess it; then you may stay with me and be my captain.”

“I know the Moors,” replied Gama. “I know their lies that have poisoned your ears. Am I mad that I should voluntarily leave my pleasant home and dare the terrors of an unknown sea? Ah, monarch, you know not the Lusian race! Bold, dauntless, the king commands, and we obey. Past the dread Cape of Storms have I ventured, bearing no gift save friendly peace, and that noblest gift of all, the friendship of my king. I have spoken the truth. Truth is everlasting!”

A day passed and still Gama was detained by the power of the Catual, who ordered him to call his fleets ashore if his voyage was really one of friendship.

“Never!” exclaimed Gama. “My fleet is free, though I am chained, and they shall carry to Lisbon the news of my discovery.”

As he spoke, at a sign from the Catual, hostile ships were seen surrounding the Lusian vessels. “Not one shall tell on Lisbon’s shores your fate.”

Gama smiled scornfully, as the fleet swept on towards his vessels. Loud sounded the drums, shrill the trumpets. The next moment sudden lightning flashed from Gama’s ships and the skies echoed with the thunder of the guns.

No word fell from Gama’s lips as, the battle over, they saw the sea covered with the torn hulks and floating masts; but the populace raged around the palace gates, demanding justice to the strangers.

The troubled king sought to make peace with Gama.

“My orders have been given. To-day, when the sun reaches its meridian, India shall bleed and Calicut shall fall. The time is almost here. I make no terms. You have deceived me once.”

The Moors fell fainting on the floor; the monarch trembled. “What can save us?” he cried.

“Convey me and my train to the fleet. Command at once; it is even now noon.”

Once more safe within his ship, with him the faithful Monçaide, who had kept him informed of the treason of the Moors, his ships laden with cinnamon, cloves, pepper, and gems, proofs of his visit, Gama, rejoicing, set sail for home.

Venus saw the fleet setting out, and planned a resting-place for the weary sailors, a floating isle with golden sands, bowers of laurel and myrtle, beautiful flowers and luscious fruits. Here the sea nymphs gathered, Thetis, the most beautiful, being reserved for Gama, and here days were spent in joyance.

At the banquet the nymphs sang the future glories of the Lusians, and taking Gama by the hand, led him and his men to a mountain height, whence they could look upon a wondrous globe, the universe. The crystal spheres whirled swiftly, making sweet music, and as they listened to this, they saw the sun go by, the stars, Apollo, the Queen of Love, Diana, and the "yellow earth, the centre of the whole.” Asia and Africa were unrolled to their sight, and the future of India, conquered by the Lusians, Cochin China, China, Japan, Sumatra,–all these countries given to the world by their voyage around the terrible cape.

“Spread thy sails!” cried the nymphs; “the time has come to go!”

The ships departed on their homeward way, and the heroes were received with the wildest welcome by the dwellers on Tago’s bosom.

Selections From the Lusiad

INEZ DE CASTRO.

During the reign of Alfonso the Brave, his son Don Pedro secretly wedded a beautiful maiden of the court, Inez de Castro. The courtiers, jealous because Inez was a Castilian, betrayed Pedro’s secret to the king, who, in the absence of his son, had Inez brought before him and slain by hired ruffians.

While glory, thus, Alonzo’s name adorn’d, To Lisbon’s shores the happy chief return’d, In glorious peace and well-deserv’d repose, His course of fame, and honor’d age to close. When now, O king, a damsel’s fate severe, A fate which ever claims the woful tear, Disgraced his honors–On the nymph’s ’lorn head Relentless rage its bitterest rancor shed: Yet, such the zeal her princely lover bore, Her breathless corse the crown of Lisbon wore. ’Twas thou, O Love, whose dreaded shafts control The hind’s rude heart, and tear the hero’s soul; Thou, ruthless power, with bloodshed never cloy’d, ’Twas thou thy lovely votary destroy’d. Thy thirst still burning for a deeper woe, In vain to thee the tears of beauty flow; The breast that feels thy purest flames divine, With spouting gore must bathe thy cruel shrine. Such thy dire triumphs!–Thou, O nymph, the while, Prophetic of the god’s unpitying guile, In tender scenes by love-sick fancy wrought, By fear oft shifted, as by fancy brought, In sweet Mondego’s ever-verdant bowers, Languish’d away the slow and lonely hours: While now, as terror wak’d thy boding fears, The conscious stream receiv’d thy pearly tears; And now, as hope reviv’d the brighter flame, Each echo sigh’d thy princely lover’s name. Nor less could absence from thy prince remove The dear remembrance of his distant love: Thy looks, thy smiles, before him ever glow, And o’er his melting heart endearing flow: By night his slumbers bring thee to his arms, By day his thoughts still wander o’er thy charms: By night, by day, each thought thy loves employ, Each thought the memory, or the hope, of joy. Though fairest princely dames invok’d his love, No princely dame his constant faith could move: For thee, alone, his constant passion burn’d, For thee the proffer’d royal maids he scorn’d. Ah, hope of bliss too high–the princely dames Refus’d, dread rage the father’s breast inflames; He, with an old man’s wintry eye, surveys The youth’s fond love, and coldly with it weighs The people’s murmurs of his son’s delay To bless the nation with his nuptial day. (Alas, the nuptial day was past unknown, Which, but when crown’d, the prince could dare to own.) And, with the fair one’s blood, the vengeful sire Resolves to quench his Pedro’s faithful fire. Oh, thou dread sword, oft stain’d with heroes’ gore, Thou awful terror of the prostrate Moor, What rage could aim thee at a female breast, Unarm’d, by softness and by love possess’d!

Dragg’d from her bower, by murd’rous ruffian hands, Before the frowning king fair Inez stands; Her tears of artless innocence, her air So mild, so lovely, and her face so fair, Mov’d the stern monarch; when, with eager zeal, Her fierce destroyers urg’d the public weal; Dread rage again the tyrant’s soul possess’d, And his dark brow his cruel thoughts confess’d; O’er her fair face a sudden paleness spread, Her throbbing heart with gen’rous anguish bled, Anguish to view her lover’s hopeless woes,

And all the mother in her bosom rose. Her beauteous eyes, in trembling tear-drops drown’d, To heaven she lifted (for her hands were bound); Then, on her infants turn’d the piteous glance, The look of bleeding woe; the babes advance, Smiling in innocence of infant age, Unaw’d, unconscious of their grandsire’s rage; To whom, as bursting sorrow gave the flow, The native heart-sprung eloquence of woe, The lovely captive thus:–"O monarch, hear, If e’er to thee the name of man was dear, If prowling tigers, or the wolf’s wild brood (Inspired by nature with the lust of blood), Have yet been mov’d the weeping babe to spare, Nor left, but tended with a nurse’s care, As Rome’s great founders to the world were given; Shall thou, who wear’st the sacred stamp of Heaven The human form divine, shalt thou deny That aid, that pity, which e’en beasts supply! Oh, that thy heart were, as thy looks declare, Of human mould, superfluous were my prayer; Thou couldst not, then, a helpless damsel slay, Whose sole offence in fond affection lay, In faith to him who first his love confess’d, Who first to love allur’d her virgin breast. In these my babes shalt thou thine image see, And, still tremendous, hurl thy rage on me? Me, for their sakes, if yet thou wilt not spare, Oh, let these infants prove thy pious care! Yet, Pity’s lenient current ever flows From that brave breast where genuine valor glows; That thou art brave, let vanquish’d Afric tell, Then let thy pity o’er my anguish swell; Ah, let my woes, unconscious of a crime, Procure mine exile to some barb’rous clime: Give me to wander o’er the burning plains Of Libya’s deserts, or the wild domains Of Scythia’s snow-clad rocks, and frozen shore; There let me, hopeless of return, deplore: Where ghastly horror fills the dreary vale, Where shrieks and howlings die on every gale, The lion’s roaring, and the tiger’s yell, There with my infant race, consigned to dwell, There let me try that piety to find, In vain by me implor’d from human kind: There, in some dreary cavern’s rocky womb, Amid the horrors of sepulchral gloom, For him whose love I mourn, my love shall glow, The sigh shall murmur, and the tear shall flow: All my fond wish, and all my hope, to rear These infant pledges of a love so dear, Amidst my griefs a soothing glad employ, Amidst my fears a woful, hopeless joy.”

In tears she utter’d–as the frozen snow Touch’d by the spring’s mild ray, begins to flow, So just began to melt his stubborn soul, As mild-ray’d Pity o’er the tyrant stole; But destiny forbade: with eager zeal (Again pretended for the public weal), Her fierce accusers urg’d her speedy doom; Again, dark rage diffus’d its horrid gloom O’er stern Alonzo’s brow: swift at the sign, Their swords, unsheath’d, around her brandish’d shine. O foul disgrace, of knighthood lasting stain, By men of arms a helpless lady slain!

Thus Pyrrhus, burning with unmanly ire, Fulfilled the mandate of his furious sire; Disdainful of the frantic matron’s prayer, On fair Polyxena, her last fond care, He rush’d, his blade yet warm with Priam’s gore, And dash’d the daughter on the sacred floor; While mildly she her raving mother eyed, Resigned her bosom to the sword, and died. Thus Inez, while her eyes to heaven appeal, Resigns her bosom to the murd’ring steel: That snowy neck, whose matchless form sustain’d The loveliest face, where all the graces reign’d, Whose charms so long the gallant prince enflam’d, That her pale corse was Lisbon’s queen proclaim’d, That snowy neck was stain’d with spouting gore, Another sword her lovely bosom tore. The flowers that glisten’d with her tears bedew’d, Now shrunk and languished with her blood embru’d. As when a rose ere-while of bloom so gay, Thrown from the careless virgin’s breast away, Lies faded on the plain, the living red, The snowy white, and all its fragrance fled; So from her cheeks the roses died away, And pale in death the beauteous Inez lay: With dreadful smiles, and crimson’d with her blood, Round the wan victim the stern murd’rers stood, Unmindful of the sure, though future hour, Sacred to vengeance and her lover’s power.

O Sun, couldst thou so foul a crime behold,

Nor veil thine head in darkness, as of old

A sudden night unwonted horror cast

O’er that dire banquet, where the sire’s repast

The son’s torn limbs supplied!–Yet you, ye vales!

Ye distant forests, and ye flow’ry dales!

When pale and sinking to the dreadful fall,

You heard her quiv’ring lips on Pedro call;

Your faithful echoes caught the parting sound,

And Pedro! Pedro! mournful, sigh’d around.

Nor less the wood-nymphs of Mondego’s groves

Bewail’d the memory of her hapless loves:

Her griefs they wept, and, to a plaintive rill

Transform’d their tears, which weeps and murmurs still.

To give immortal pity to her woe

They taught the riv’let through her bowers to flow,

And still, through violet-beds, the fountain pours

Its plaintive wailing, and is named Amours.

Nor long her blood for vengeance cried in vain:

Her gallant lord begins his awful reign,

In vain her murderers for refuge fly,

Spain’s wildest hills no place of rest supply.

The injur’d lover’s and the monarch’s ire,

And stern-brow’d Justice in their doom conspire:

In hissing flames they die, and yield their souls in fire.

Mickle’s Translation, Canto III.

THE SPIRIT OF THE CAPE.

Vasco de Gama relates the incidents of his voyage from Portugal to the King of Melinda. The southern cross had appeared in the heavens and the fleet was approaching the southern point of Africa. While at anchor in a bay the Portuguese aroused the hostility of the savages, and hastily set sail.

“Now, prosp’rous gales the bending canvas swell’d; From these rude shores our fearless course we held: Beneath the glist’ning wave the god of day Had now five times withdrawn the parting ray, When o’er the prow a sudden darkness spread, And, slowly floating o’er the mast’s tall head A black cloud hover’d: nor appear’d from far The moon’s pale glimpse, nor faintly twinkling star; So deep a gloom the low’ring vapor cast, Transfix’d with awe the bravest stood aghast. Meanwhile, a hollow bursting roar resounds, As when hoarse surges lash their rocky mounds; Nor had the black’ning wave nor frowning heav’n The wonted signs of gath’ring tempest giv’n. Amazed we stood. ’O thou, our fortune’s guide, Avert this omen, mighty God!’ I cried; ’Or, through forbidden climes adventurous stray’d, Have we the secrets of the deep survey’d, Which these wide solitudes of seas and sky Were doom’d to hide from man’s unhallow’d eye? Whate’er this prodigy, it threatens more Than midnight tempests, and the mingled roar, When sea and sky combine to rock the marble shore.’

“I spoke, when rising through the darken’d air, Appall’d, we saw a hideous phantom glare; High and enormous o’er the flood he tower’d, And ’thwart our way with sullen aspect lower’d: An earthy paleness o’er his cheeks was spread, Erect uprose his hairs of wither’d red; Writhing to speak, his sable lips disclose, Sharp and disjoin’d, his gnashing teeth’s blue rows; His haggard beard flow’d quiv’ring on the wind, Revenge and horror in his mien combin’d; His clouded front, by with’ring lightnings scar’d, The inward anguish of his soul declar’d. His red eyes, glowing from their dusky caves, Shot livid fires: far echoing o’er the waves His voice resounded, as the cavern’d shore With hollow groan repeats the tempest’s roar. Cold gliding horrors thrill’d each hero’s breast, Our bristling hair and tott’ring knees confess’d Wild dread, the while with visage ghastly wan, His black lips trembling, thus the fiend began:–

“’O you, the boldest of the nations, fir’d By daring pride, by lust of fame inspir’d, Who, scornful of the bow’rs of sweet repose, Through these my waves advance your fearless prows, Regardless of the length’ning wat’ry way, And all the storms that own my sov’reign sway, Who, mid surrounding rocks and shelves explore Where never hero brav’d my rage before; Ye sons of Lusus, who with eyes profane Have view’d the secrets of my awful reign, Have passed the bounds which jealous Nature drew To veil her secret shrine from mortal view; Hear from my lips what direful woes attend, And, bursting soon, shall o’er your race descend.

“’With every bounding keel that dares my rage, Eternal war my rocks and storms shall wage, The next proud fleet that through my drear domain, With daring search shall hoist the streaming vane, That gallant navy, by my whirlwinds toss’d, And raging seas, shall perish on my coast: Then he, who first my secret reign descried, A naked corpse, wide floating o’er the tide, Shall drive–Unless my heart’s full raptures fail, O Lusus! oft shall thou thy children wail; Each year thy shipwreck’d sons thou shalt deplore, Each year thy sheeted masts shall strew my shore.

“’With trophies plum’d behold a hero come, Ye dreary wilds, prepare his yawning tomb. Though smiling fortune bless’d his youthful morn, Though glory’s rays his laurell’d brows adorn, Full oft though he beheld with sparkling eye The Turkish moons in wild confusion fly, While he, proud victor, thunder’d in the rear, All, all his mighty fame shall vanish here. Quiloa’s sons, and thine, Mombaz, shall see Their conqueror bend his laurell’d head to me; While, proudly mingling with the tempest’s sound, Their shouts of joy from every cliff rebound.

“’The howling blast, ye slumb’ring storms prepare, A youthful lover and his beauteous fair Triumphant sail from India’s ravag’d land; His evil angel leads him to my strand. Through the torn hulk the dashing waves shall roar, The shatter’d wrecks shall blacken all my shore. Themselves escaped, despoil’d by savage hands, Shall, naked, wander o’er the burning sands, Spar’d by the waves far deeper woes to bear, Woes, e’en by me, acknowledg’d with a tear. Their infant race, the promis’d heirs of joy, Shall now, no more, a hundred hands employ; By cruel want, beneath the parents’ eye, In these wide wastes their infant race shall die; Through dreary wilds, where never pilgrim trod Where caverns yawn, and rocky fragments nod, The hapless lover and his bride shall stray, By night unshelter’d, and forlorn by day. In vain the lover o’er the trackless plain Shall dart his eyes, and cheer his spouse in vain. Her tender limbs, and breast of mountain snow, Where, ne’er before, intruding blast might blow, Parch’d by the sun, and shrivell’d by the cold Of dewy night, shall he, fond man, behold. Thus, wand’ring wide, a thousand ills o’er past, In fond embraces they shall sink at last; While pitying tears their dying eyes o’erflow, And the last sigh shall wail each other’s woe.

“’Some few, the sad companions of their fate, Shall yet survive, protected by my hate, On Tagus’ banks the dismal tale to tell, How, blasted by my frown, your heroes fell.’

“He paus’d, in act still further to disclose A long, a dreary prophecy of woes: When springing onward, loud my voice resounds, And midst his rage the threat’ning shade confounds.

“’What art thou, horrid form that rid’st the air? By Heaven’s eternal light, stern fiend, declare.’ His lips he writhes, his eyes far round he throws, And, from his breast, deep hollow groans arose, Sternly askance he stood: with wounded pride And anguish torn, ’In me, behold,’ he cried, While dark-red sparkles from his eyeballs roll’d, ’In me the Spirit of the Cape behold, That rock, by you the Cape of Tempests nam’d, By Neptune’s rage, in horrid earthquakes fram’d, When Jove’s red bolts o’er Titan’s offspring flam’d. With wide-stretch’d piles I guard the pathless strand, And Afric’s southern mound, unmov’d, I stand: Nor Roman prow, nor daring Tyrian oar Ere dash’d the white wave foaming to my shore; Nor Greece nor Carthage ever spread the sail On these my seas, to catch the trading gale. You, you alone have dar’d to plough my main, And with the human voice disturb my lonesome reign.”

“He spoke, and deep a lengthen’d sigh he drew, A doleful sound, and vanish’d from the view: The frighten’d billows gave a rolling swell, And, distant far, prolong’d the dismal yell, Faint and more faint the howling echoes die, And the black cloud dispersing, leaves the sky. High to the angel-host, whose guardian care Had ever round us watch’d, my hands I rear, And Heaven’s dread King implore: ’As o’er our head The fiend dissolv’d, an empty shadow fled; So may his curses, by the winds of heav’n, Far o’er the deep, their idle sport, be driv’n!’”

With sacred horror thrill’d, Melinda’s lord Held up the eager hand, and caught the word. “Oh, wondrous faith of ancient days,” he cries, “Concealed in mystic lore and dark disguise! Taught by their sires, our hoary fathers tell, On these rude shores a giant spectre fell, What time from heaven the rebel band were thrown: And oft the wand’ring swain has heard his moan. While o’er the wave the clouded moon appears To hide her weeping face, his voice he rears O’er the wild storm. Deep in the days of yore, A holy pilgrim trod the nightly shore; Stern groans he heard; by ghostly spells controll’d, His fate, mysterious, thus the spectre told:

“’By forceful Titan’s warm embrace compress’d, The rock-ribb’d mother, Earth, his love confess’d: The hundred-handed giant at a birth, And me, she bore, nor slept my hopes on earth; My heart avow’d my sire’s ethereal flame; Great Adamastor, then, my dreaded name. In my bold brother’s glorious toils engaged, Tremendous war against the gods I waged: Yet, not to reach the throne of heaven I try, With mountain pil’d on mountain to the sky; To me the conquest of the seas befell, In his green realm the second Jove to quell. Nor did ambition all my passions hold, ’Twas love that prompted an attempt so bold. Ah me, one summer in the cool of day, I saw the Nereids on the sandy bay, With lovely Thetis from the wave advance In mirthful frolic, and the naked dance. In all her charms reveal’d the goddess trod, With fiercest fires my struggling bosom glow’d; Yet, yet I feel them burning in my heart, And hopeless, languish with the raging smart. For her, each goddess of the heavens I scorn’d, For her alone my fervent ardor burn’d. In vain I woo’d her to the lover’s bed, From my grim form, with horror, mute she fled. Madd’ning with love, by force I ween to gain The silver goddess of the blue domain; To the hoar mother of the Nereid band I tell my purpose, and her aid command: By fear impell’d, old Doris tried to move, And win the spouse of Peleus to my love. The silver goddess with a smile replies, ’What nymph can yield her charms a giant’s prize! Yet, from the horrors of a war to save, And guard in peace our empire of the wave, Whate’er with honor he may hope to gain, That, let him hope his wish shall soon attain.’ The promis’d grace infus’d a bolder fire, And shook my mighty limbs with fierce desire. But ah, what error spreads its dreadful night, What phantoms hover o’er the lover’s sight!

“The war resign’d, my steps by Doris led, While gentle eve her shadowy mantle spread, Before my steps the snowy Thetis shone In all her charms, all naked, and alone. Swift as the wind with open arms I sprung, And, round her waist with joy delirious clung: In all the transports of the warm embrace, A hundred kisses on her angel face, On all its various charms my rage bestows, And, on her cheek, my cheek enraptur’d glows. When oh, what anguish while my shame I tell! What fix’d despair, what rage my bosom swell! Here was no goddess, here no heavenly charms, A rugged mountain fill’d my eager arms, Whose rocky top, o’erhung with matted brier, Received the kisses of my am’rous fire. Wak’d from my dream, cold horror freez’d my blood; Fix’d as a rock, before the rock I stood; ’O fairest goddess of the ocean train, Behold the triumph of thy proud disdain; Yet why,’ I cried, ’with all I wish’d decoy, And, when exulting in the dream of joy, A horrid mountain to mine arms convey?’ Madd’ning I spoke, and furious sprung away. Far to the south I sought the world unknown, Where I, unheard, unscorn’d, might wail alone, My foul dishonor, and my tears to hide, And shun the triumph of the goddess’ pride. My brothers, now, by Jove’s red arm o’erthrown, Beneath huge mountains pil’d on mountains groan; And I, who taught each echo to deplore, And tell my sorrows to the desert shore, I felt the hand of Jove my crimes pursue, My stiff’ning flesh to earthy ridges grew, And my huge bones, no more by marrow warm’d, To horrid piles, and ribs of rock transform’d, Yon dark-brow’d cape of monstrous size became, Where, round me still, in triumph o’er my shame, The silv’ry Thetis bids her surges roar, And waft my groans along the dreary shore.’”

Mickle’s Translation, Canto V .

Return To Chapter 3