Chapter XXXV: Origins Of Mythology - Statues of Gods and Goddesses - Poets of Mythology

ORIGIN OF MYTHOLOGY.

HAVING reached the close of our series of stories of Pagan mythology, an inquiry suggests itself.

“Whence came these stories? Have they a foundation in truth, or are they simply dreams of the imagination?”

Philosophers have suggested various theories of the subject;

1. The Scriptural theory; according to which all mythological legends are derived from the narratives of Scriptures, though the real facts have been disguised and altered. Thus Deucalion is only another name for Noah, Hercules for Samson, Arion for Jonah, etc. Sir Walter Raleigh, in his “History of the World,” says, “Jubal, Tubal, and Tubal–Cain were Mercury, Vulcan, and Apollo, inventors of Pasturage, Smithing, and Music.

The Dragon which kept the golden apples was the serpent that beguiled Eve. Nimrod’s tower was the attempt of the Giants against Heaven.”

There are doubtless many curious coincidences like these, but the theory cannot without extravagance be pushed so far as to account for any great proportion of the stories.

2. The Historical theory; according to which all the persons mentioned in mythology were once real human beings, and the legends and fabulous traditions relating to them are merely the additions and embellishments of later times.

Thus the story of AEolus, the king and god of the winds, is supposed to have risen from the fact that AEolus was the ruler of some islands in the Tyrrhenian Sea, where be reigned as a just and pious king, and taught the natives the use of sails for or ships, and how to tell from the signs of the atmosphere the changes of the weather and the winds.

Cadmus, who, the legend says, sowed the earth with dragon’s teeth, from which sprang a crop of armed men, was in fact an emigrant from Phoenicia, and brought with him into Greece the knowledge of the letters of the alphabet, which be taught to the natives. From these rudiments of learning sprung civilization, which the poets have always been prone to describe as a deterioration of man’s first estate, the Golden Age of innocence and simplicity.

3. The Allegorical theory supposes that all the myths of the ancients were allegorical and symbolical, and contained some moral, religious, or philosophical truth or historical fact, under the form of an allegory, but came in process of time to be understood literally.

Thus Saturn, who devours his own children, is the same power whom the Greeks called Cronos (Time), which may truly be said to destroy whatever it has brought into existence. The story of Io is interpreted in a similar manner. Io is the moon, and Argus the starry sky, which, as it were, keeps sleepless watch over her. The fabulous wanderings of lo represent the continual revolutions of the moon, which also suggested to Milton the same idea.

“To behold the wandering moon

Riding near her highest noon,

Like one that had been led astray

In the heaven’s wide, pathless way.”

Il Penseroso.

4. The Physical theory; according to which the elements of air, fire, and water were originally the objects of religious adoration, and the principal deities were personifications of the powers of nature. The transition was easy from a personification of the elements to the notion of supernatural beings presiding over and governing the different objects of nature.

The Greeks, whose imagination was lively, peopled all nature with invisible beings, and supposed that every object, from the sun and sea to the smallest fountain and rivulet, was under the care of some particular divinity. Wordsworth, in his “Excursion,” has beautifully developed this view of Grecian mythology:

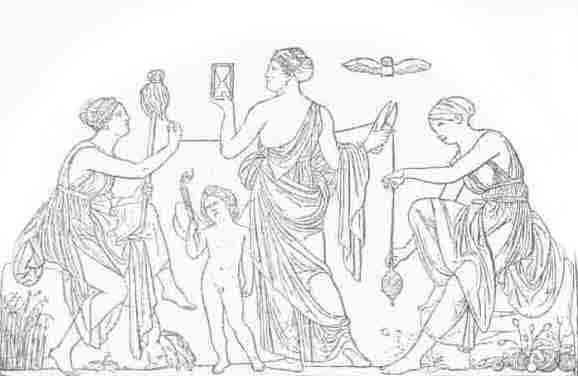

Pluto and Proserpine. p. 65 1908 Edition

“In that fair clime the lonely herdsman, stretched

On the soft grass through half a summer’s day,

With music lulled his indolent repose;

And, in some fit of weariness, if he,

When his own breath was silent, chanced to hear

A distant strain far sweeter than the sounds

Which his poor skill could make, his fancy fetched

Even from the blazing chariot of the Sun

A beardless youth who touched a golden lute,

And filled the illumined groves with ravishment.

The mighty hunter, lifting up his eyes

Toward the crescent Moon, with grateful heart

Called on the lovely Wanderer who bestowed

That timely light to share his joyous sport;

And hence a beaming goddess with her nymphs

Across the lawn and through the darksome grove

(Not unaccompanied with tuneful notes

By echo multiplied from rock or cave)

Swept in the storm of chase, as moon and stars

Glance rapidly along the clouded heaven

When winds are blowing strong. The Traveller slaked

His thirst from rill or gushing fount, and thanked

The Naiad. Sunbeams upon distant hills

Gliding apace with shadows in their train,

Might, with small help from fancy, be transformed

Into fleet Oreads sporting visibly.

The Zephyrs, fanning, as they passed, their wings,

Lacked not for love fair objects whom they wooed

With gentle whisper. Withered boughs grotesque,

Stripped of their leaves and twigs by hoary age,

From depth of shaggy covert peeping forth

In the low vale, or on steep mountain side;

And sometimes intermixed with stirring horns

Of the live deer, or goat’s depending beard;

These were the lurking Satyrs, a wild brood

Of gamesome deities; or Pan himself,

That simple shepherd’s awe-inspiring god.”

All the theories which have been mentioned are true to a certain extent. It would therefore be more correct to say that the mythology of a nation has sprung from all these sources combined than from any one in particular. We may add also that there are many myths which have arisen from the desire of man to account for those natural phenomena which he cannot understand; and not a few have had their rise from a similar desire of giving a reason for the names of places and persons.

STATUES OF THE GODS.

To adequately represent to the eye the ideas intended to be conveyed to the mind under the several names of deities was a task which called into exercise the highest powers of genius and art. Of to many attempts four have been most celebrated the first two known to us only by the descriptions of the ancients, the others still extant and the acknowledged masterpieces of the sculptor’s art.

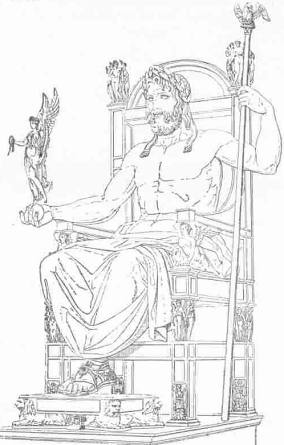

THE OLYMPIAN JUPITER.

The statue of the Olympian Jupiter by Phidias was considered the highest achievement of this department of Grecian art. It was of colossal dimensions, and was what the ancients called “chryselephantine”; that is, composed of ivory and gold; the parts representing flesh being of ivory laid on a core of wood or stone, while the drapery and other ornaments were of gold. The height of the figure was forty feet, on a pedestal twelve feet high. The god was represented seated on his throne. His brows were crowned with a wreath of olive, and he held in his right hand a sceptre, and in his left a statue of Victory. The throne was of cedar, adorned with gold and precious stones.

The idea which the artist essayed to embody was that of the supreme deity of the Hellenic (Grecian) nation, enthroned as a conqueror, in perfect majesty and repose, and ruling with a nod the subject world. Phidias avowed that he took his idea from the representation which Homer gives in the first book of the “Iliad,” in the passage thus translated by Pope:

Olympian Jupiter. p. 327 1908 Edition

“He spoke and awful bends his sable brows,

Shakes his ambrosial curls and gives the nod,

The stamp of fate and sanction of the god.

High heaven with reverence the dread signal took,

And all Olympus to the centre shook.” [36]

[36] Cowper’s version is less elegant, but truer to the original:

“He ceased, and under his dark brows the nod

Vouchsafed of confirmation. All around

The sovereign’s everlasting head his curls

Ambrosial shook, and the huge mountain reeled.”

It may interest our readers to see how this passage appears in another famous version, that which was issued under the name of Tickell, contemporaneously with Pope’s, and which, being by many attributed to Addison, led to the quarrel which ensued between Addison and Pope:

“This said, his kingly brow the sire inclined;

The large black curls fell awful from behind,

Thick shadowing the stern forehead of the god;

Olympus trembled at the almighty nod.”

THE MINERVA OF THE PARTHENON.

This was also the work of Phidias. It stood in the Parthenon, or temple of Minerva at Athens. The goddess was represented standing. In one hand she held a spear, in the other a statue of Victory. Her helmet, highly decorated, was surmounted by a Sphinx. The statue was forty feet in height, and, like the Jupiter, composed of ivory and gold. The eyes were of marble, and probably painted to represent the iris and pupil. The Parthenon, in which this statue stood, was also constructed under the direction and superintendence of Phidias. Its exterior was enriched with sculptures, many of them from the hand of Phidias. The Elgin marbles, now in the British Museum, are a part of them.

Both the Jupiter and Minerva of Phidias are lost, but there is good ground to believe that we have, in several extant statues and busts, the artist’s conceptions of the countenances of both. They are characterized by grave and dignified beauty, and freedom from any transient expression, which in the language of art is called repose.

THE VENUS DE’ MEDICI.

The Venus of the Medici is so called from its having been in the possession of the princes of that name in Rome when it first attracted attention, about two hundred years ago. An inscription on the base records it to be the work of Cleomenes, an Athenian sculptor of 200 B.C., but the authenticity of the inscription is doubtful. There is a story that the artist was employed by public authority to make a statue exhibiting the perfection of female beauty, and to aid him in his task the most perfect forms the city could supply were furnished him for models. It is this which Thomson alludes to in his “Summer”:

“So stands the statue that enchants the world;

So bending tries to veil the matchless boast,

The mingled beauties of exulting Greece.”

Byron also alludes to this statue. Speaking of the Florence Museum, he says:

“There, too, the goddess loves in stone, and fills

The air around with beauty;” etc.

And in the next stanza, “Blood, pulse, and breast confirm the Dardan shepherd’s prize.”

See this last allusion explained in Chapter XXVII.

THE APOLLO BELVEDERE.

The most highly esteemed of all the remains of ancient sculpture is the statue of Apollo, called the Belvedere, from the name of the apartment of the Pope’s palace at Rome in which it was placed.

The artist is unknown. It is supposed to be a work of Roman art, of about the first century of our era. It is a standing figure, in marble, more than seven feet high, naked except for the cloak which is fastened around the neck and hangs over the extended left arm.

It is supposed to represent the god in the moment when he has shot the arrow to destroy the monster Python. (See Chapter III) The victorious divinity is in the act of stepping forward.

The left arm, which seems to have held the bow, is outstretched, and the head is turned in the same direction. In attitude and proportion the graceful majesty of the figure is unsurpassed. The effect is completed by the countenance, where on the perfection of youthful godlike beauty there dwells the consciousness of triumphant power.

THE DIANA A LA BICHE.

The Diana of the Hind, in the palace of the Louvre, may be considered the counterpart to the Apollo Belvedere. The attitude much resembles that of the Apollo, the sizes correspond and also the style of execution. It is a work of the highest order, though by no means equal to the Apollo.

The attitude is that of hurried and eager motion, the face that of a huntress in the excitement of the chase. The left hand is extended over the forehead of the Hind, which runs by her side, the right arm reaches backward over the shoulder to draw an arrow from the quiver.

THE POETS OF MYTHOLOGY.

Homer, from whose poems of the “Iliad” and “Odyssey” we have taken the chief part of our chapters of the Trojan war and the return of the Grecians, is almost as mythical a personage as the heroes he celebrates. The traditionary story is that he was a wandering minstrel, blind and old, who travelled from place to place singing his lays to the music of his harp, in the courts of princes or the cottages of peasants, and dependent upon the voluntary offerings of his hearers for support. Byron calls him “The blind old man of Scio’s rocky isle,” and a well–known epigram, alluding to the uncertainty of the fact of his birthplace, says:

“Seven wealthy towns contend for Homer dead,

Through which the living Homer begged his bread.”

These seven were Smyrna, Scio, Rhodes, Colophon, Salamis, Argos, and Athens.

Modern scholars have doubted whether the Homeric poems are the work of any single mind. This arises from the difficulty of believing that poems of such length could have been committed to writing at so early an age as that usually assigned to these, an age earlier than the date of any remaining inscriptions or coins, and when no materials capable of containing such long productions were yet introduced into use. On the other hand it is asked how poems of such length could have been handed down from age to age by means of the memory alone. This is answered by the statement that there was a professional body of men, called Rhapsodists, who recited the poems of others, and whose business it was to commit to memory and rehearse for pay the national and patriotic legends.

The prevailing opinion of the learned, at this time, seems to be that the framework and much of the structure of the poems belongs to Homer, but that there are numerous interpolations and additions by other hands.

The date assigned to Homer, on the authority of Herodotus, is 850 B.C.

VIRGIL.

Virgil, called also by his surname, Maro, from whose poem of the “AEneid” we have taken the story of AEneas, was one of the great poets who made the reign of the Roman emperor Augustus so celebrated, under the name of the Augustan age. Virgil was born in Mantua in the year 70 B.C. His great poem is ranked next to those of Homer, in the highest class of poetical composition, the Epic.

Virgil is far inferior to Homer in originality and invention, but superior to him in correctness and elegance. To critics of English lineage Milton alone of modern poets seems worthy to be classed with these illustrious ancients. His poem of “Paradise Lost,” from which we have borrowed so many illustrations, is in many respects equal, in some superior, to either of the great works of antiquity. The following epigram of Dryden characterizes the three poets with as much truth as it is usual to find in such pointed criticism.

“ON MILTON.

“Three poets in three different ages born,

Greece, Italy, and England did adorn.

The first in loftiness of soul surpassed,

The next in majesty, in both the last.

The force of nature could no further go;

To make a third she joined the other two.”

From Cowper’s “Table Talk”:

“Ages elapsed ere Homer’s lamp appeared,

And ages ere the Mantuan swan was heard.

To carry nature lengths unknown before,

To give a Milton birth, asked ages more.

Thus genius rose and set at ordered times,

And shot a dayspring into distant climes,

Ennobling every region that he chose;

He sunk in Greece, in Italy he rose,

And, tedious years of Gothic darkness past,

Emerged all splendour in our isle at last.

Thus lovely Halcyons dive into the main,

Then show far off their shining plumes again.”

OVID.

OVID, often alluded to in poetry by his other name of Naso, was born in the year 43 B.C. He was educated for public life and held some offices of considerable dignity, but poetry was his delight, and he early resolved to devote himself to it.

He accordingly sought the society of the contemporary poets, and was acquainted with Horace and saw Virgil, though the latter died when Ovid was yet too young and undistinguished to have formed his acquaintance. Ovid spent an easy life at Rome in the enjoyment of a competent income. He was intimate with the family of Augustus, the emperor, and it is supposed that some serious offence given to some member of that family was the cause of an event which reversed the poet’s happy circumstances and clouded all the latter portion of his life.

At the age of fifty he was banished from Rome, and ordered to betake himself to Tomi, on the borders of the Black Sea. Here, among the barbarous people and in a severe climate, the poet, who had been accustomed to all the pleasures of a luxurious capital and the society of his most distinguished contemporaries, spent the last ten years of his life, worn out with grief and anxiety. His only consolation in exile was to address his wife and absent friends, and his letters were all poetical. Though these poems (the “Tristia” and “Letters from Pontus”) have no other topic than the poet’s sorrow’s, his exquisite taste and fruitful invention have redeemed them from the charge of being tedious, and they are read with pleasure and even with sympathy.

The two great works of Ovid are his “Metamorphoses” and his “Fasti.” They are both mythological poems, and from the former we have taken most of our stories of Grecian and Roman mythology. A late writer thus characterizes these poems:

“The rich mythology of Greece furnished Ovid, as it may still furnish the poet, the painter, and the sculptor, with materials for his art. With exquisite taste, simplicity, and pathos he has narrated the fabulous traditions of early ages, and given to them that appearance of reality which only a master–hand could impart. His pictures of nature are striking and true; he selects with care that which is appropriate; he rejects the superfluous; and when he has completed his work, it is neither defective nor redundant. The ‘Metamorphoses’ are read with pleasure by youth, and are re–read in more advanced age with still greater delight. The poet ventured to predict that his poem would survive him, and be read wherever the Roman name was known.”

[*]See: Ovid's Creation of the World [*]

The prediction above alluded to is contained in the closing lines of the “Metamorphoses,” of which we give a literal translation below:

“And now I close my work, which not the ire

Of Jove, nor tooth of time, nor sword, nor fire

Shall bring to nought. Come when it will that day

Which o’er the body, not the mind, has sway,

And snatch the remnant of my life away,

My better part above the stars shall soar,

And my renown endure for evermore.

Where’er the Roman arms and arts shall spread,

There by the people shall my book be read;

And, if aught true in poet’s visions be,

My name and fame have immortality.”

?