Asgard and the Gods

The Tales and Traditions of Our Northern Ancestors

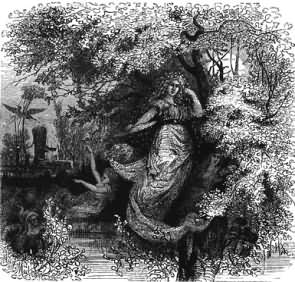

FRIGG AND HER MAIDENS

After the birth of Thor, whose mother was Jörd (the Earth), daughter of the giantess Fiörgyn, Odin left the dark Earth-goddess and married bright Frigg, a younger daughter of Fiörgyn; henceforth she shared his throne Hlidskialf, his divine wisdom and his power, becoming the joy and delight of his heart, and the mother of the Ases.

FRIGG AND HER MAIDENS

She ruled with him over the fate of mortals and granted her votaries good fortune and victory, often bringing about her ends by woman's cunning. Just as in Hellas a feast was held each year in commemoration of the marriage of Zeus and Hera, so did the old Teutons in like manner hold festivity to celebrate the union of Odin and Freya.

Freya's palace was called Fensaler, that is, the hall of the sea. It probably got this name from the dwellers on the coast, who looked upon Frigg as the ruler of the sea and protector of ships. A soothing twilight always reigned, and it was adorned with pearls and gold and silver. And the goddess would bring all lovers, and husbands and wives who had been separated by an early death, to this peaceful palace, where they were reunited for ever. This belief of the old Teutons shows us that they regarded love in its truest and highest aspect, and built their hopes on being reunited after death to the objects of their affections. What we learn from the Latin annals of Armin and Thusnelda, of the high position of women as seers of future events, proves to us that noble women were always treated even by rude, fighting men, with respect and reverence; while the romance of love is clearly shown in the Northern myth of Brynhild, who threw herself upon the burning pyre in order that she might be reunited to her beloved Sigurd.

In her gorgeous palace Frigg sits spinning, on her golden distaff, the silken threads, which she afterwards bestows on the most worthy housewives. The goddess' spinning-wheel was visible to man every night, for it was that shining, starry zone which we in our ignorance now point out as the Belt of Orion, but which to our ancestors was the Heaven-queen's spinning-wheel. The goddess had three friends and attendants always beside her, and with these she used to hold council on human affairs, in the hall of the moon.

Fulla or Volla was the first of Frigg's attendant-goddesses, and chief of the maidens; according to Teutonic belief she was also the sister of the Queen of Heaven. She wore a golden circlet round her head, and beneath it her long hair floated over her shoulders. Her office was to take charge of the Queen's jewels, and to clothe her royal mistress. She listened to the prayers of sorrowful mortals, repeated them to Frigg, and advised her how best to give help.

Hlin, the second of Frigg's maidens, was the protector of all who were in danger and of those who called upon her for help in hour of need.

The messenger of the Queen of Heaven was Gna, who rode, swift as the wind, on a horse with golden trappings, over land and sea, and through the clouds that floated in the air, to bring her mistress news of the fate of mortal men.

Once as Gna was hovering over Hunaland, she saw King Rerir, a descendant of Sigi and of the race of Odin, sitting on the side of a hill. She heard him praying for a child, that his family might not be blotted out of memory; for both he and his wife were advanced in years, and they had got no child to carry on their noble race. She told the goddess of the prayer of the king, who had often presented fine fruit as a sacrifice to the heavenly powers. Frigg smilingly gave her an apple which would ensure the fulfilment of the king's desire. Gna quickly remounted her horse Hoof-flinger, and hastened over land and sea, and over the country of the wise Wanes, who gazed up at the bold rider in astonishment, and asked:

"What flies up there, so quickly driving past?"

Her answer from the clouds, as rushing by:

"I fly not, nor do drive, but hurry fast

Hoof-flinger swift through cloud and mist and sky."

King Rerir was still seated on the hillside under the shade of a fir-tree, when the divine messenger came down to earth at the skirt of the wood close to where he sat. She took the form of a hooded-crow, and flew up into the fir-tree. She heard the prince mourning over the sad fate that had befallen him, that his family would die out with him, and then she let the apple fall into his lap. At first he gazed at the fruit in amazement, but soon he understood the meaning of the divine gift, took it home with him and gave it to his spouse to eat.

Meanwhile Gna guided her noble horse rapidly along the star-lit road to Asgard, and told her mistress joyously of the success of her mission. In due time the Queen of Hunaland had a son, the great Wolsing, from whom the whole family took its name. He was the father of brave Sigmund, the favourite of Odin, and he in his turn of Sigurd, the fame of whose glory was spread over every Northern and Teutonic land.

When the Queen of Heaven heard of the success that had accompanied her divine gift, she herself decided to be the bearer of the news to the assembled gods and heroes, and determined to appear in her most glorious array. Fulla spread out all the Queen's jewels until they shone like stars, yet Frigg was not satisfied. Then Fulla pointed to Odin's statue of pure gold, that stood in the hall of the temple. She thought a worthy ornament might be made for the goddess out of that gold, if the skilful artificers who had made such a marvellous likeness of the Father of the gods could only be won over. The artists were bribed with rich presents and they at last cut away some of the gold from a place that was covered by the folds of the floating mantle, so that the theft could not easily be discovered. They then made the Queen a necklace of incomparable beauty. When Frigg entered the assembly and seated herself on the throne beside Odin, she at once made known to all present how she had saved a noble family from extinction. Every one gazed at her beauty in amazement, and the Father of the gods felt his heart filled anew with love for his queen.

A short time afterwards Odin went to the hall of the temple in which his statue was placed. His penetrating eye at once discovered the theft that no one else had noticed, and his wrath was immediately kindled. He sent for the goldsmiths, and as they confessed nothing, he ordered them to be executed. Then he commanded that the statue should be placed above the high gate of the temple, and prepared magic runes that should give it sense and speech, and thus enable it to accuse the perpetrator of the deed. The Goddess-queen was greatly alarmed at all these preparations. She feared the anger of her lord, and still more the shame of her deed being proclaimed in the presence of the ruling Ases.

Now there happened to be in the Queen's household a serving demon of low rank, but bold and daring, who had already ventured to show his admiration for his mistress. Fulla went to him and assured him that the Queen was touched by his devotion, upon which the demon declared himself willing to run any risks for her sake. He made the temple watchmen fall into a deep sleep, tore down the statue from above the door, and dashed it in pieces, so that it could no longer speak or complain.

Odin saw what he was doing and guessed the reason. He raised Gungnir, the spear of death, ready to fling at all who had been concerned in the evil deed. But his love for Frigg triumphed over all else; he determined on another punishment.

He withdrew from gods and men; he disappeared into distant regions, and with him went every blessing from heaven and earth. A false Odin took his place, who let loose the storms of winter and the Ice-giants over field and meadow. Every green; leaf withered, thick clouds hid the golden sun and the light of the moon and stars; the earth, lakes and rivers were frozen by the raging cold which threatened to destroy all forms of life. Every creature longed for the return of the god of blessing, and at length he came back. Thunder and lightning made known his approach. The usurper fled before the true Odin; and shrubs and herbs of all kinds sprouted anew over the face of the earth, which was now made young again by the warmth of spring.

In the foregoing tale, we have endeavoured as much as possible to make a connected narrative out of the confused, and now and then contradictory, myths regarding Frigg and her handmaids. We will only add that the myth which completes it, dates from a time when the gods had paled in the eyes of the people, and had become less exalted in character than of old. There are many versions of it differing from one another, and it serves here to show the difference between Summer-Odin and Winter-Odin.

OTHER GODDESSES RELATED TO FRIGG

Let us now again turn our attention to the great goddess Frigg, The Northern skalds first raised her to the throne and distinguished her from Freya or Frea, the goddess of the Wanes. She was originally identical with her, as her name and character show. For Frigg comes from frigen, a Low-German word connected with freien in High-German, and meaning to woo, to marry, thus pointing to the character of the goddess. The old Germanic races, therefore, knew Frea alone as Queen of Heaven, and she and her husband Wodan together ruled over the world. The name Frigga or Frick was also used for her, for in Hesse, and especially in Darmstadt, people used to say fifty years ago of any fat old woman : "Sic ist so dick wie die alte Frick." (She is as thick [fat] as Old Frick.) The word frigen is also related to sich freuen (rejoice); thus Frigg was the goddess of joy (Freude). She took the place of the Earth-goddess Nerthus (mistakenly Hertha), who, Tacitus informs us, was worshipped in a sacred grove on an island in the sea. Nerthus was probably the wife of the god of heaven, in whom we recognise Zio or Tyr. He was the hidden god who according to the detailed account of Tacitus, was so reverently worshipped in a sacred grove by the Semnones, the noblest of the Swabian tribes, that the people never set foot on the ground that was consecrated to him without having their hands first bound. The Earth-goddess may also have been the wife and sister of Niörder, and separated from him when he was received amongst the Ases. In this case she belonged to the earlier race of gods, the Wanes, and her husband must have then been called Nerthus, a name afterwards changed into Niörder.

In Mecklenburg the same goddess appears under the name of Mistress Gaude or Gode, which is the feminine form of Wodan or Godan. The country people believed that she brought good luck with her wherever she went.

One story informs us that she once got a carpenter to mend a wheel of her carriage, which had broken when she was on a journey. She gave him all the chips of wood as a reward for his trouble. The man was angry at getting so paltry a remuneration, and only pocketed a few of the chips; but next morning he saw with astonishment that they had turned to pure gold.

According to another tale, Dame Gode was a great huntress, who together with her twenty-four daughters devoted herself to the noble pursuit of the chase day and night, on week-days and on Sundays. She was therefore made to hunt to all eternity, and her pack of hounds consisted of maidens who were turned into dogs by enchantment; she was thus forced to take part in the Wild Hunt.

In France the goddess was called Bensocia (good neighbour, bona socia), and in the Netherlands, Pharaildis, i.e., Frau Hilde or Vrouelden, whence the Milky Way was named Vrouelden-straat.

Hilde (Held, hero) signifies war, and she was a Walkyrie, who with her sisters exercised her office in the midst of the battle. Later poems make her out to be daughter of King Högni, who was carried off, while gathering magic herbs on the seashore, by bold Hedin when he was on a Wiking-raid. Her father pursued the Wiking with his war-ships, and came up with him on an island. In vain Hilde strove to prevent bloodshed. Högni had already drawn his terrible sword, Dainsleif, the wounds made by which never healed. Once more Hedin offered the king expiation and much red gold in atonement for what he had done.

His father-in-law shouted in scorn: "My sword Dainsleif, which was forged by the Dwarfs, never returns to its sheath until it has drunk a share of human blood!"

The battle began and raged all day without being decided one way or the other.

In the evening both parties returned to their ships to strengthen themselves for the combat on the morrow.

But Hilde went to the field of battle, and by means of runes and magic signs awakened all the dead warriors and made whole their broken swords and shields.

As soon as day broke, the fight was renewed, and lasted until the darkness of night obliged the combatants to stop.

HILDE, ONE OF THE WALKYRIES

The dead were stretched out on the battle-field as stiff as figures of stone; but before morning dawned the witch-maiden had awakened them to new battle, and so it went on unceasingly until the gods passed away.

Hilde was also known and worshipped in Germany, as is shown by the legend about the foundation of the town of Hildesheim.

One year, as soon as snow had fallen on the spot dedicated to her, King Ludwig-ordered the cathedral to be built there. The Virgin Mary afterwards took her place, and several churches were built in honour of Maria am Schnee (Marie au neige) both in Germany and in France.

Nehalennia, the protectress of ships and trade, was worshipped by the Keltic and Teutonic races in a sacred grove on the island of Walcheren; she had also altars and holy places dedicated to her at Nivelles. The worship of Isa or Eisen, who was identical with Nehalennia, was even older and more wide-spread throughout Germany. St. Gertrude took her place in Christian times, and her name (Geer, i.e., spear, and Trude, daughter of. Thor) betrays its heathen origin.

HOLDA. OSTARA.

Once upon a time, in a lonely valley of the Tyrol, where snowcapped glaciers ever shone, there lived a cow-herd with his wife and children. He used to drive his small herd of cattle out to graze in the pastures, and now and again would shoot a chamois, for he was a skilled bowman. His cross-bow also served to protect his cattle from the beasts of prey, and the numerous bear-skins and wolf-skins that covered the floor of his cottage bore witness to his success as a hunter.

One day, when he was watching his cattle and goats on a fragrant upland pasture, he suddenly perceived a splendid chamois, whose horns shone like the sun. He immediately seized his bow and crept forward on hands and knees until he was within shot. But the deer sprang from rock to rock higher up the mountain, seeming every now and then to wait for him, as though it mocked his pursuit. He continued the chase eagerly until he reached the glacier which had sunk below the snow-fields.

The chamois now vanished behind some huge boulders, but at the same time he discovered a high arched doorway in the glacier, and in the background beyond he saw a light shining.

He went through the dark entrance boldly, and found himself in a large hall, the walls and ceiling of which were composed of dazzling crystal, ornamented with fiery garnets. He could see flowery meadows and shady groves through the crystal walls; but a tall woman was standing in the centre of the hall, her graceful limbs draped in glancing, silvery garments, caught in at the waist by a golden girdle, and resting on her blond curls was a coronet of carbuncles. The flowers in her hand were blue as the eyes with which she gently regarded the cow-herd. Beautiful maidens, their heads crowned with Alpine roses, surrounded their mistress, and seemed about to begin a dance. But the herdsman had no eye for any except the goddess, and sank humbly on his knees.

Then she said in a voice that went straight to the heart of the hearer:

"Choose what thou thinkest the most costly of all my treasures, silver, gold, or precious stones, or one of my maidens."

"Give me, kind goddess," he answered; "give me only the bunch of flowers in thy hand; I desire no other good thing upon the earth."

She bent her head graciously as she gave him the flowers, and said:

"Thou hast chosen wisely. Take them and live as long as these flowers bloom. And here," pointing to a corn measure, "is seed with which to sow thy land that it may bear thee many blue flowers such as these."

He would have embraced her knees, but a peal of thunder shook the hall and the mountain, and the vision was gone.

When the cow-herd awoke from his vision, he saw nothing but the rocks and the glacier, and the wild torrent that flowed out of it; the entrance to the palace of the goddess had vanished. The nosegay was still in his hand and beside him was the wooden measure full of seed. These tokens convinced him that what had happened was not a mere dream.

He took up his presents and his cross-bow, and descended the mountain thoughtfully to see what had become of his cattle. They were nowhere to be seen, look for them where he might, and when he went home he found nothing but want and misery. Bears and wolves had devoured his herd, and only the swift-footed goats had escaped from the beasts of prey.

A whole year had elapsed since he had left home, and yet he had thought that he had only spent a few hours chamois-hunting in the mountains. When he showed his wife the bunch of flowers, and told her that he intended to sow the seed that had been given him, she scolded him, and mocked him for his folly; but he would not be turned aside from his determination, and bore all his wife's hard words most patiently.

He ploughed up a field and sowed the seed, but there was still a great deal over; he sowed a second and a third field, and yet much seed remained. The little green sprouts soon showed in the fields, grew longer and longer, till at length the blue flowers unfolded themselves in great numbers, and even the cow-herd's wife rejoiced at the sight, so lovely were they to look upon.

The man watched over his crop day and night, and he often saw the goddess of the mountain wandering through his fields in the moonlight with her maidens, blessing them with uplifted hands.

When the flowers were all withered and the seed was ripe, she came again, and showed how the flax was to be prepared, after which she went into the cottage and taught the cow-herd's wife how to spin and weave the flax and bleach the linen, so that it became as white as newly fallen snow.

The cow-herd rapidly grew rich, and became a benefactor to his country, for he introduced the cultivation of flax throughout the land, which gave employment and wages to thousands of country-people. He saw children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren around him, but the bunch of flowers the goddess had given him was still as fresh as ever, even when he was more than a hundred years old and very tired of life.

One morning while he was looking at his beloved flowers, they all bent down their heads, withered and dying. Then he knew that it was time to say farewell to earthly life. Leaning on his staff, he toiled painfully up the mountains. It was already evening when he reached the glacier.

The snow-fields above were shining gloriously as though in honour of the last walk of the good old man. He once more saw the vaulted doorway and the glimmering light beyond. And then he passed with good courage through the dark entrance into the bright morning which greets the weary pilgrim, when, after his earthly journey is over, he reaches Hulda's halls. The door now closed behind him, and he was seen no more on earth.

This and other traditions of the same kind are told in the Tyrol of the old Germanic goddess Hulda or Holda. Her name shows that she was a goddess of grace and mercy, and she must have been worshipped both in Germany and in Sweden, but still no traces are to be found of her at the present day in the Teutoburg Forest, where so many of the places and names point back to the old Germanic religion, nor yet do the Northern skalds give an account of her.

HOLDA, THE KIND PROTECTRESS

However, German fairy legends and tales call to us the great goddess whose character and deeds live on in the memory of the people, and the Northern Huldra, who drew men to her by means of her wondrous song, is exactly identical with her. Her name has been derived from the old Northern Hulda, i.e., Darkness; and it has been thought that she was the impersonation of the dark side of the goddess of Earth and Death; but the derivation which we gave before, from Huld, grace, mercy, seems more suitable.

A Northern fairy-tale makes Hulla or Hulda, queen of the Kobolds. She was a daughter of the queen of the Hulde-men, who killed first her faithless husband and then herself. She enticed wise King Odin by means of a stag, to her mansion, which was hidden in the depths of a wood. She gave him of her best, and then begged him to act as umpire in a legal dispute that had arisen between her and the other Kobolds and Thurses, about the murder of her husband. He consented to do so, and his decision made her queen of all the Kobolds and Thurses in Norseland. This tale is quite modern in its form, but it certainly is based on ancient beliefs.

A poem dating from the middle ages places Holda in the Mountain of Venus, a place that is generally supposed to be the Horselberg in Thuringia. She was then called Mistress Venus, and held a splendid court with her women. Noble knights, amongst whom was Ritter Tannhäuser, were drawn by her into the mountain, where they lived such a gay, merry life of pleasure that they could hardly ever again free themselves from her spell and make their escape, even though thoughts of honour and duty might now and then return to them.

It was finally said of Holda, that those who were crippled in any way were restored to full strength and power by bathing in her Quickborn (fountain of life), and that old men found their vanished youth there once more. This tradition connects her with the Northern Iduna, who had charge of the apple that preserved the immortality and vigour of the Ases. But she also resembled Ostara, who was worshipped by the Saxons, Franks and other tribes.

Ostara, the goddess of Spring, of the resurrection of nature after the long death of winter, was highly honoured by all the old Teutons, nor could Christian zeal prevent her name being immortalised in the word Easter, the period of spring, at which time the Saxons in England worshipped her. The memory of these old times has long since passed away, although the "hare" still lays its "Easter-eggs." The custom is very old of giving each other coloured eggs as a present at the time when day and night became equal in length and when the frozen earth awakens to new life after the cold of winter is gone, for an egg was typical of the beginning of life. Christianity put another meaning on the old custom, by connecting it with the feast of the Resurrection of the Saviour, who, like the hidden life in the egg, slept in the grave for three days before he wakened to new life.

There are no legends about the goddess of spring. One monument alone, and that a newly discovered one, remains of the old worship, the Extern-stones, which are to be found in the Teutoburg Forest at the northern end of the wooded hills. It is stated in the chronicle of a neighbouring village, dating from last century, that the ignorant peasantry were guilty of many misdemeanours there when doing honour to the heathen goddess Ostara. Had the clergyman only told us whether there were processions, dances, feasts, scattering of flowers, or any other kind of sacrifice, a clear light might have been shed over the manner in which the goddess was worshipped. Still, this fact proves that not only the name, but also the worship of Ostara was kept in the memories of the people for hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years, and shows how deeply rooted it was. The rocks may perhaps have been called Eastern or Eostern-stones, and may have been dedicated to Ostara. There, as elsewhere, the priests and priestesses of the goddess probably assembled in heathen times, scattered Mayflowers, lighted bonfires, slaughtered the creatures sacrificed to her, and went in procession on the first night of May, which was dedicated to her. Very much the same as this used to be done at Gambach, in Upper Hesse, where, as late as thirty years ago even, the young people went to the Easter-stones on the top of a hill, every Easter, and danced and held sports. Edicts were published in the eighth century forbidding these practices; but in vain, the people would not give up their old faith and customs. Afterwards the priestesses were declared to be witches, the bonfires, which cast their light to great distances, were said to be of infernal origin, and the festival of May was looked upon as the witches' sabbath. Nevertheless, young men and maidens still continue, near the Meissner-Gebirg in Hesse, to carry bunches of Mayflowers and throw them into one of the caves that are to be found there. For Ostara, who gives new life to nature, is the divine protectress of youth and the giver of married happiness.

BERCHTA OR BERTA

The dusk of evening has fallen over Berlin. A great yet silent crowd is rapidly moving through the chief street towards the royal palace, and every now and then a low whisper is heard, in which can be distinguished the words: "The King is very ill." In the palace itself yet greater silence reigns. The King's guardsmen stand motionless, the servants' steps are inaudible on the carpets of the corridors and the rooms. Now the tower clock strikes midnight; all at once a door opens, and through it glides a ghostly woman, tall of stature, queenly of bearing.

She is dressed in a trailing white garment, a white veil covers her head, below which her long flaxen hair hangs, twisted with strings of pearls; her face is deathly pale as that of a corpse. In her right hand she carries a bunch of keys, in her left a nosegay of Mayflowers. She walks solemnly down the long corridor. The tall guardsmen present arms, pages and lackeys give way before her, the guards who have just relieved their comrades open their ranks; the figure passes through them, and goes through a folding door into the royal ante-room.

"It is the White Lady; the King is about to die," whispers the officer of the watch, brushing a tear from his eye.

"The White Lady has appeared," is whispered through the crowd, and all know what that portends.

At noon the King's death was known to all. "Yes," said Master Schneckenburger, "he has been gathered to his fathers. Mistress Berchta has once more announced what was going to happen, for she can foretell everything, both bad and good. She was seen before the misfortunes of 1806, and again before the battle of Belle-Alliance. She has a key with which to open the door of life and happiness. He to whom she gives a cowslip will succeed in whatever he undertakes."

Schneckenburger was right. It was Bertha, or Berchta, who made known the King's approaching death, but she was also the prophetess of other important events. Berchta (from percht, shining) is almost identical with Holda, except that the latter never appears as the White Lady. Many Germanic tribes worshipped the Earth-goddess under the name of Berchta, and there are numbers of legends about her both in North and South Germany.

One evening in the year was dedicated to her, and was called Perchten-evening (30th December or 6th January), when she was supposed, as a diligent spinner, to oversee the labours of the spinningroom, or, magic staff in hand, to ride at the head of the Raging Host, in the midst of a terrific storm. She generally lived in hollow mountains, where she, as in Thuringia, watched over and tended the "Heimchen," or souls of babes as yet unborn, and of those who died an early death. She busied herself there by ploughing up the ground under the earth, whilst the babes watered the fields. Whenever men, careless of the good she did them, disturbed her in her mountain dwelling, she left the country with her train, and after her departure the fields lost all their former fruitfulness.

Once when Berchta and her babes were passing over a meadow across the middle of which ran a fence that divided it in two, the last little child could not climb over it; its water-jar was too heavy.

A woman, who a short time before had lost her little baby, was close by, and recognised her dead darling, for whom she had wept night and day. She hastened to the child, clasped it in her arms, and would not let it go.

Then the little one said: "How warm and comfortable I feel in my mother's arms; but weep no more for me, mother, my jar is full and is growing too heavy for me. Look, mother, dost thou not see how all thy tears run into it, and how I've spilt some on my little shirt? Mistress Berchta, who loves me and kisses me, has told me that thou shouldst also come to her in time, and then we shall be together again in the beautiful garden under the hill."

Then the mother wept once more a flood of tears, and let the child go.

After that she never shed another tear, but found comfort in the thought that she would one day be with her child again.

Berchta appears in many legends as an enchantress, or as an enchanted maiden, who provided a rich treasure for him who was lucky enough to set her free from the magic spell that bound her. Still more frequently, however, she took up her abode in princely castles as the Ahnfrau," or Ancestress of the family to whom the castle belonged. In these stories the Goddess of Nature is hardly recognisable.

It is told that the widowed Countess Kunigunde of Orlamünd fell in love with Count Albrecht the beautiful, of Hohenzollern. He told her that four eyes stood in the way of a marriage between them, and she, thinking that he referred to her children, had them secretly murdered. But, as the tale informs us, he had meant his parents, who disapproved of the marriage. He felt nothing but abhorrence of the murderess when he found out what she had done, and she, repenting of her sin, made a pilgrimage to Rome, did severe penance, and afterwards founded the nunnery of the Heavenly Crown, where she died an abbess. Her grave, as well as those of her children and of the Burggraf Albrecht, are still shown there. From that time she appeared at the Plassenburg, near Baireuth, as the "Ahnfrau," who made known any evil that was going to happen; later on she went to Berlin with the Count's family, and is still to be seen there as the tale at the beginning of this chapter shows.

Another account makes the apparition out to be the Countess Beatrix of Cleve, who was married to the Swan-Knight so often mentioned among the old heroes of the middle ages. The House of Cleve was nearly related to that of Hohenzollern, and in the mysterious Swan-Knight we recognise the god of Light, who comes out of the darkness of night and returns to it again.

A more simple version refers to a Bohemian Countess, Bertha of Rosenberg. She was unhappily married to Johann of Lichtenberg, after whose death she became the benefactress of her subjects, built the Castle Neuhaus, and never laid aside the white garments of widowhood as long as she lived. In this dress she appeared, and even now appears, to the kindred families of Rosenberg, Neuhaus and Berlin, on which occasion she prophesies either good or evil fortune.

The Germanic races carried the worship of this Earth-goddess with them to Gaul and Italy, in the former of which countries a proverbial expression refers to the underground kingdom of the goddess, by reminding people "du temps que Berthe filait." It was that time of innocence and peace, of which almost every nation has its tradition, for which it longs, and to which it can only return after death.

Historical personages have also been supposed to enact the part formerly given to the Earth-mother.

A tradition of the 12th century informs us that Pepin, father of Charlemagne, wished to marry Bertrada, a Hungarian princess, who was a very good and diligent spinner. His wooing was successful, and the princess and her ladies set out on their journey to Pepin's court. The bride's marvellous beauty was only marred by her having a very large foot.

Now the chief lady-in-waiting was a wicked woman, and jealous of Bertrada; so she gave the princess to some villains she had bribed, in order that she might be murdered in the forest, and then she put her own ugly daughter in her mistress's place. Although Pepin was disgusted with his deformed bride, he was obliged to marry her according to compact; but soon afterwards, on finding out the deception that had been practised upon him, he put her from him.

Late one evening when out hunting, he came to a mill on the river Maine. There he saw a girl spinning busily. He recognised her as the true Bertrada by her large foot, found out how her intended murderers had taken compassion on her, and how she had finally reached the mill. He then discovered his rank to her, and entreated her to fulfil her engagement to him. The fruit of this marriage was Charlemagne.

In this tale we recognise the old myth under a modern form.

We see how Mother Earth, the protectress of souls and ancestress of man, especially of those of royal or heroic race, is thrust aside by the cunning, wintry Berchta, but is joined again by her heavenly husband, and becomes the mother of the god of Spring. Even the large foot reminds us of the goddess, who was originally supposed to show herself in the form of a swan. This is the reason why in French churches there are representations of queens with a swan's or goose's foot (reine pédauque).

Other French stories show Berchta in the form of Holda: how she sheds tears for her lost spouse, so bitter that the very stones are penetrated by them. Both goddesses are identical with the Northern Freya, who wept golden tears for her husband.

There is an old ballad that is still sung in the neighbourhood of Mayence, which tells of the bright, blessed kingdom of the goddess. We can give only the matter of it here, as the verses themselves have not remained in our memory.

A huntsman once stood sadly at the water's edge, and thought on his lost love. He had had a young and lovely wife, who, when he came wearied home from the chase, would welcome him with the warm kiss of love. She bare him a sweet babe, and made him perfectly happy. But ere long both were taken from his side by grim, envious death, and now he was alone. Gladly would he have died with them, but that was not to be. Three months had flown by, but his wife and child were still always in his thoughts.

One night his way led him beside a flowing stream; he stopped still on the bank, gazed long into the water's depths, and asked

"Is the broken heart to be made whole in a watery grave alone?"

Thereupon sweet silvery notes fell upon his ear; and as he glanced upwards, he saw before him a beauteous, queenly woman, sitting opposite him on the other side of the stream; she was spinning golden flax, and singing a wondrous song:

"Youth, enter thou my shining hall,

Where joy and peace e'er rest;

When the weary heart at 'length finds all

Its loved ones, 'gain 'tis blest!

The coward calls my hall the grave,

My kiss he fears 'twere death;

But the leap is boldly made by the brave -

His the gain by the loss of life's breath!

Youth, leave thou, then, the lonesome, des'late shore,

And boldly gain the joy enduring evermore."

The huntsman listens; do the thrilling tones come from the beauteous woman on the opposite bank, or is it from the watery deep that they proceed?

Wildly he leaps into the flood, and a fair, white arm is extended, encircling him and drawing him down beneath the water's surface, away from all earthly cares, away from all earthly distress and pain. And his loved ones greet him, his youthful wife and his babe. "See, father! how green the trees grow here, and how the coloured flowers sparkle with silver! And no one cries here, no one has any troubles! "

This tale is based upon the old heathen belief as to the life in a future state; it shows us that the conviction of our forefathers has always been, that for the virtuous death was merely a transition to a new life, to a life purer, more complete, than that on earth.

THOR, THUNAR (THUNDER)

Arwaker (Early-waker) and Alswider (All-swift), the horses of the sun, were wearily drawing the fiery chariot to its rest. The sea and the ice-clad mountains were glowing in the last rays of the setting sun. The clouds that were rising in the west received them in their lap. Then flashes of lightning darted forth from the clouds, thunder began to roll in the distance, and the waves dashed in wild fury upon the rock-bound coast of the fiord.

"Hang up the snow-shoes, lad, and take off thy fur cap; Ökuthor (Thor of the chariot) is driving over to waken old Mother Jörd. Put the jar of mead on the stone table, wife, that he may find something to drink; and you, you lazy fellows, why are you sitting idly over the fire, instead of rubbing up the ploughshares until they shine again? This is going to be a fruitful year, for Hlorridi (heat-bringer) has come early. Come, Thialf, pull off my fur boots."

Thus spoke the yeoman to whom Balshoff belonged, as he sat on the stone bench by the fire. But then he stopped short, and stared open-mouthed; Thialf let the fur boots fall from his hand; the mistress of the house dropped the jug of mead, and the farm-servants the plough. Wingthor drove over from the west in all his fury; he struck the house with his hammer Miölnir, and the flash broke through the ridge of the roof beside the pillar that supported it, and penetrated a hundred miles below the clay floor. A sulphureous vapour filled the room; but the yeoman, shaking off his stupefaction, rose from his stone bench, and when he saw that no more damage was done, he said:

"Wingthor has been gracious to us, and now he has gone on to fight against the Frost and Mountain Giants. Do ye not hear the blows of his hammer, the howls of the monsters in their caverns, and the crashing of their stone heads as though they were nothing but oatmeal dumplings? But to us he has given rain, which even now is falling heavily, rain that will soon melt away the snow and prepare the soil to receive the seed we shall sow later on. The tiny sprouts will grow rapidly, and grass and herbs and the green leek will reward us for our industry. Preserve the golden ears of corn for us, O Thor, until the harvest time."

In such manner people used, in the olden time, to call on the strong god of thunder, Thunar, - in the North, Thor. He was held in great reverence, and was perhaps even regarded as an equal of the God of Heaven. Traces of this are still recognisable, for wherever he was spoken of in connection with the other gods, he was given the place of honour in the middle. The Saxons had to renounce Wodan, Donar, and Saxnot. In the temple of Upsala, Thor is placed between Odin and Freyer. In "Skirnir's journey," a poem of the Edda, it is said: "Odin is adverse to thee, the Prince of the Ases (Thor) is adverse to thee, Freyer curses thee." He retained this high position in Norway, where he fought against the Frost and Mountain Giants, who sent the destructive east wind over the country. And not less honour was paid him in Saxony and Franconia. The oak was sacred to him, and his festivals were solemnized under the shade of oak trees. When thunder-clouds passed over the earth, Thor was said to be driving his chariot drawn by two fierce male goats, called Tooth-cracker and Tooth-gnasher.

Odin - not he who sat on Hlidskialf overlooking the nine worlds, but the omnipotent God of Heaven - married Jörd, Mother Earth and the offspring of this marriage was strong Thor, who began even in the cradle to show his Ase-like strength by lifting ten loads of bear-skins.

Gentle old Mother Jörd, who was known by several other names in different parts of Germany, could not manage her strong son, so two other beings, Wingnir (the winged), and Hlora (heat) became his foster-parents. These were personifications of the winged lightning. From them were derived the god's names of Wingthor and Hlorridi.

Thor married Sif (kin), for he, the protector of households, was himself obliged to have a well-ordered household. The beautiful goddess had golden hair, probably because of the golden corn of which her husband was guardian, and her son was the swift archer, Uller, who hunted in snow-shoes every winter, and ruled over Asgard and Midgard in the cold season, while the summer Odin was away. By the giantess, Jarnsaxa (Ironstone) Thor had two sons, Magni (Strength) and Modi (Courage), and by his real wife a daughter, Thrud (Strong), the names of whom all remind us of his own characteristics.

Thor was handsome, large and well-proportioned, and strong. A red beard covered the lower part of his face, his hair was long and curly, his clothes were well-fitting and his arms were bare, showing his strongly-developed muscles. In his right hand he carried the crashing-hammer, Miolnir, whose blows caused the destructive lightning flash and the growling thunder.